Volume 39 Number 1

The correlation between stigma and adjustment in patients with a permanent colostomy in the Midlands of China

Fang-fang Xu, Wei-hua Yu, Mei Yu, Sheng-qin Wang and Gui-hua Zhou

Keywords Colostomy, stigma, ostomy adjustment.

For referencing Xu F et al. The correlation between stigma and adjustment in patients with a permanent colostomy in the Midlands of China. WCET® Journal 2019; 39(1):33-39

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.1.33-39

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the correlation between stigma and ostomy adjustment in patients with a permanent colostomy.

Methods: A total of 118 patients (male 81/female 37 with an average age 57.4±15.0) from six grade 3 hospitals of the Midlands of China with a permanent colostomy were recruited. Participants responded to a questionnaire to obtain sociodemographic data, Social Impact Scale (SIS) scores to ascertain stigma level and Ostomy Adjustment Inventory (OAI-20) scores to identify the level of psychosocial adjustment.

Results: The patients’ average SIS score was (60.7±10.4). The QAI-20 total score was (41.3±10.8). The SIS total score and SIS subscores were negatively related to the total score and subscore of QAI-20 (r=-0.222~-0.537, all P<0.01). Multiple regression analysis revealed the level of self-stoma care performed, the degree of communication with medical staff, financial insecurity and social rejection when added into the regression equation had a significant negative impact on OAI-20.

Conclusion: In comparison to the average SIS score, the SIS score in this study sample is higher than midpoint, indicating stigma is closely related to ostomy adjustment. It is suggested that health professionals need to pay more attention to patients’ expressed feelings of stigma to improve their ability to adjust to living with a colostomy.

Introduction

Colostomy refers to the formation of a stoma within the large bowel whereby a piece of the colon (the stoma) is diverted through an artificial opening in the abdominal wall in order to bypass a damaged part of the colon. Colostomies are commonly formed to treat disorders of the digestive system such as colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and diverticulitis or to bypass a damaged part of the colon as the result of trauma.

Colorectal cancer is the leading reason for colostomy formation. The 2014 WHO World Cancer report shows that of all cancer cases in the past five years, colorectal cancer accounted for 10.9%, second only to breast cancer (19.2%) and thirdly prostate cancer (12.1%)1. The incidence of colorectal cancer ranked fifth in all cancers in China2 and ranked fourth in the urban population in China3.

Colostomy patients lose control of their bowel movements as the method of defecation has been changed. Further, they need to wear a colostomy bag to collect excreta and, as a result, are always worried that the colostomy bag will leak, giving off an unpleasant smell and sound. The presence of a colostomy can adversely affect patients’ daily life, sexual life and lifestyle in general as their body shape and function has changed 4-5. Some patients see their colostomy as a taboo subject and are afraid of being discovered and having to reveal they have a stoma. Patients are often too frightened or embarrassed to talk about their colostomy in public. They feel stigmatised due to the presence of their colostomy6.

Stigma is defined as a mark of perceived or actual disgrace or a feeling of being discredited that sets a person aside from others. It represents people who may be seen as unpopular due to a shortcoming or handicap. Stigma was introduced into the field of psychology by Goffman in 19637. The stigma associated with a disease refers to patients’ experience of a kind of inner shame arising from the illness. It is a feeling of being tagged or discriminated against and demeaned. It refers to alienation and avoidance by the individual by not being understood and accepted8-9. Goffman believes changes in the body, defects or deformities as well as having significant disease are characteristics of patients that make them more susceptible to feeling stigmatised. Many scholars have studied a variety of diseases that have an associated stigma, including mental illness, AIDS, cancer, incontinence, colon cancer and obesity8,10-12. MacDonald and Anderson in the United Kingdom surveyed 420 patients with rectal cancer, 256 of whom had a colostomy. Half the patients with a colostomy felt stigmatised, especially younger patients13. Smith studied 195 patients with a colostomy and found a negative correlation between the patient’s disgust at having a stoma and how they adjusted to having a colostomy and life satisfaction in general14. Danielsen et al. in Denmark found a small cohort of 15 patients with colostomies had difficulty in disclosing they had a colostomy because this may impugn their reputation. As a result, they tried to limit the variety of daily outings, imposing self-isolation6.

Disease-related stigma has become a strong predictor of disease adaptation and quality of life; however, in China research about stigma is focussed mainly on mental illness. There is almost no research on the stigma of patients with a colostomy.

Social adjustment refers to the individual’s ability to adjust to or change the environment, in which case the individual’s physical and mental state should be at an optimal state. Social adjustment is a proactive, dynamic self-adjustment process that is systemic in nature as it includes physiological, psychological, sociocultural elements and environmental aspects14. Colostomy patients face a variety of adaptation issues, including physiological, psychological and sociocultural aspects.

The level and characteristics of stigma associated with colostomy patients, as well as whether the patients’ own feelings of stigmatisation and adaptation through social adjustment can influence each other, is worth exploring. Research on stigmatisation (perceived or actual) in relation to ostomies and people with colostomies, in particular, is currently lacking in China. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the level of stigma and social adjustment in colostomy patients and to analyse the relationship between stigma and adaptation, and to provide an objective basis for clinical nursing interventions.

Methods

Participants

Patients from the stoma therapy unit of six grade 3 hospitals in the Midlands of China from December 2016 to June 2017 were enrolled into this study by convenience sampling.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were included if they:

1. were at least 18 years old;

2. had a permanent colostomy;

3. were in a rehabilitation period, having had a colostomy for one or more months;

4. were able to provide informed consent to participate in this research;

5. were able to read and understand Chinese.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with a cognitive disorder, metastatic cancer and other life-threatening serious diseases were excluded.

Survey procedure

The investigators in this study were enterostomal therapists and provincial enterostomal specialist nurses in each hospital. The authors trained the investigators how to conduct the survey. This included explaining in detail to the investigators how to convey the purpose of the survey, the methods of measurement and the details of the questionnaires used in the survey to potential study participants. Investigators followed uniform survey protocols when conducting the study. This included adopting a unified instructional language, timely feedback in response to participants’ questions, and processes for entering and validating data to ensure the accuracy of the data. Participants’ responses to the questionnaires issued were anonymous.

Measurement

Survey questionnaire

The survey questionnaire was developed by the authors. The questionnaire was comprised of 12 questions that included: age; gender; educational background; income level; house location; living state; average monthly income; length of time since surgery; types of medical payment; monthly cost of ostomy supplies; who performed the stoma care; stomal/peristomal complications; and, communication with medical staff.

Social impact scale (SIS)

The SIS is widely used in cancer and other chronic diseases to measure the associated level of stigma. The authors and investigators used the SIS to measure the level of stigma in patients with colostomies in this study. The SIS was compiled by Fife and Wright in 2000 and was translated into Chinese by Pan et al. in 200715. It consists of 24 items with four dimensions which are: social rejection; financial insecurity; internalised shame; and, social isolation. Each item scores from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate a higher level of stigma. Guan Xiao Meng et al., who used the SIS in previous studies, obtained a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.88316. The authors obtained Pan’s consent to use the Chinese version of the SIS tool before the study commenced. The Cronbach’s α coefficient set for this study was 0.915.

The Ostomy Adjustment Inventory (OAI-20)

The OAI-20 was developed by Simmons17 et al. to assess psychological adjustment in patients with a stoma. The original scale comprised 23 items and four subfactors. Each item scored from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated better social adjustment. It was translated into a Chinese version by Gao Wen Jun et al. in 2011 to 20 items and three subfactors18. The Cronbach α coefficient in this study was 0.886.

Data analysis

Epidata 3.1 (Epidata Association Freeware) was used for data entry (QES file), developing archiving protocols (REC files) and for data verification/recovery (CHK files). IBM (2011) SPSS20.0 was used for statistical data analysis.

General information was described by simple frequencies and percentages. The SIS score and OAI-20 score were described by mean, averages and standard deviations. Comparisons between groups were tested by T-test or One-Way ANOVA analysis. Correlation between the SIS and OAI-20 scores was tested by Pearson correlation analysis.

Multiple regression analysis was used to explore the related factors affecting ostomy adjustment. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Subject demographic characteristics and stoma-related information

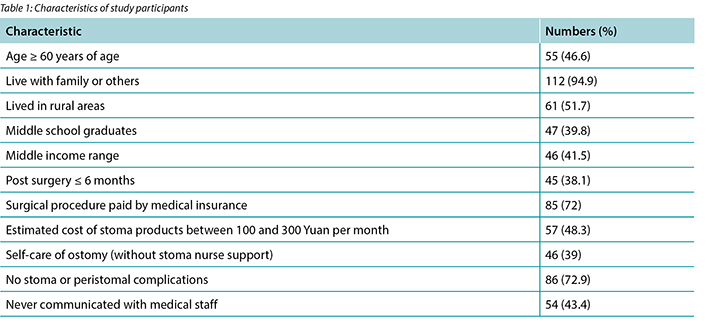

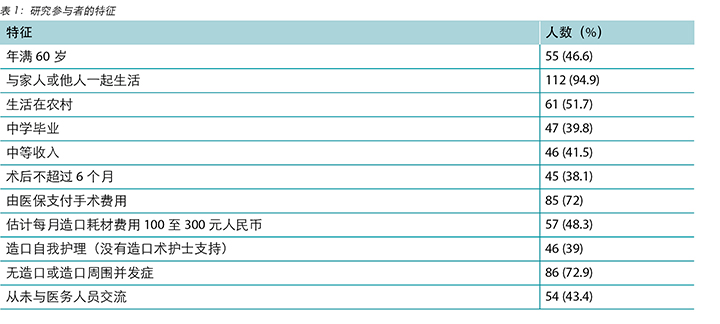

A total of 118 patients were enrolled in the study. The mean age of participants was57.4±15.0 years. Eighty-one [68.6%] males agreed to participate the study. Additional characteristics of the study participants are identified in Table 1.

Social impact and ostomy adjustment findings

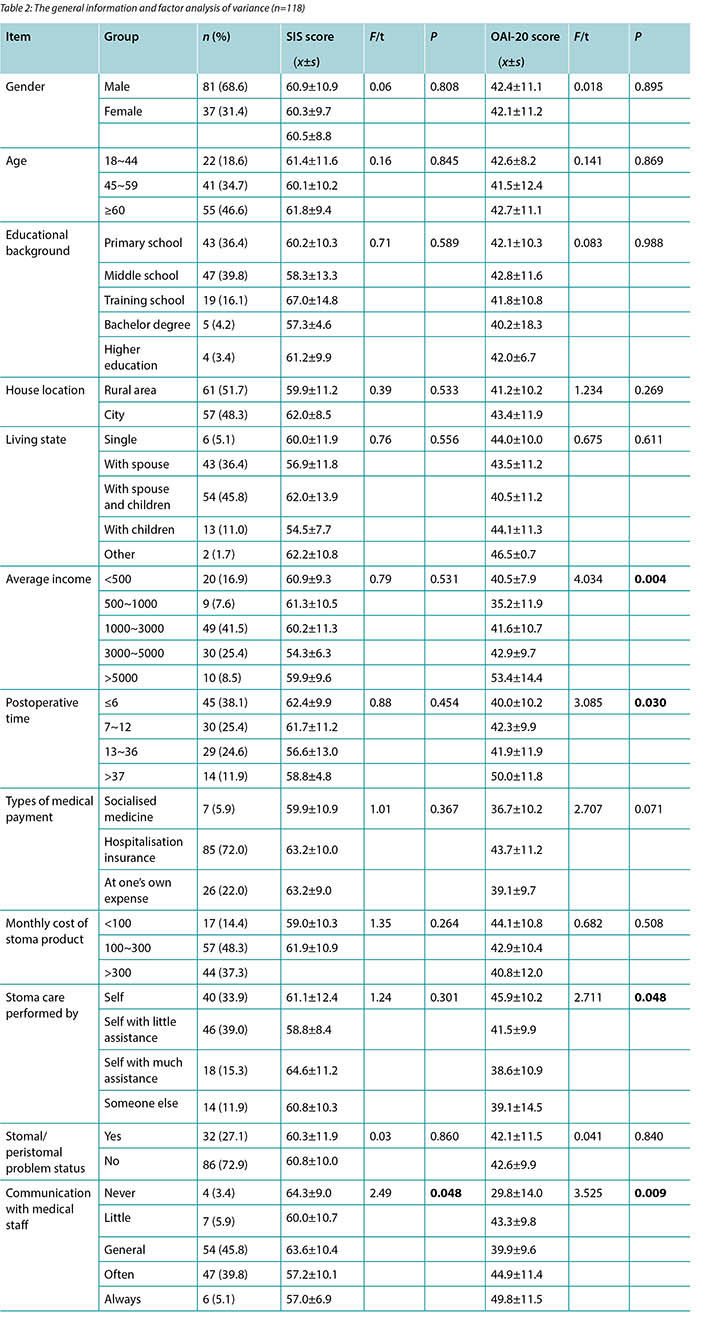

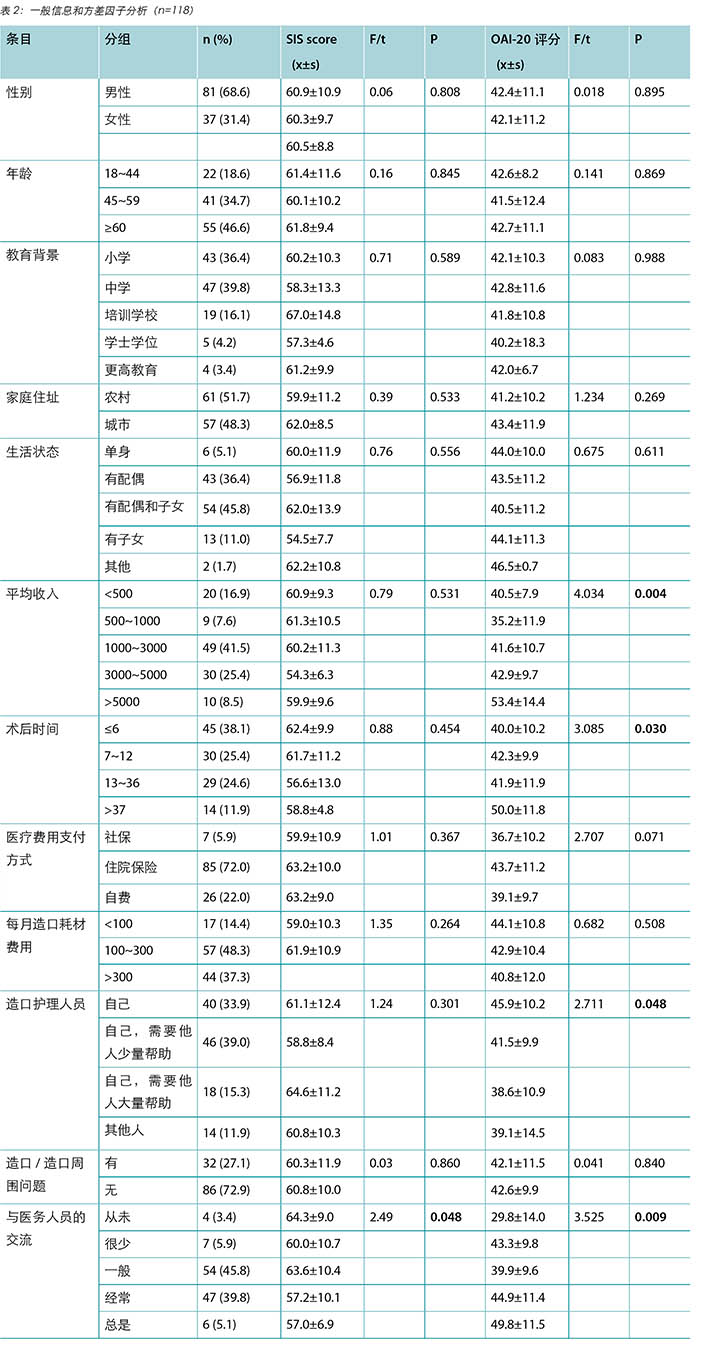

The average SIS scores were 60.7±10.4. The scoring rate was 63.2%. The social rejection, financial insecurity, internalised shame and the social isolation dimension scores were 21.8±4.3 (60.6%), 8.0±1.9, (66.7%), 12.7±2.5 (63.5%) and 18.2±3.6 (65%), respectively with response rates shown in brackets. Univariate analysis showed a significant difference with the SIS scores in the group regarding the different level of communication with medical staff; those who never communicated with the medical staff scored higher than other patients (Table 2).

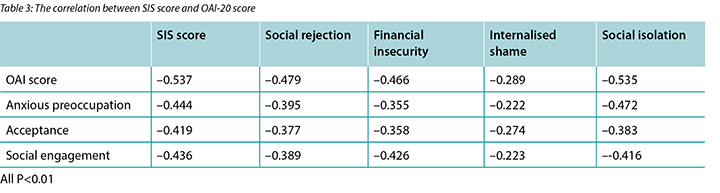

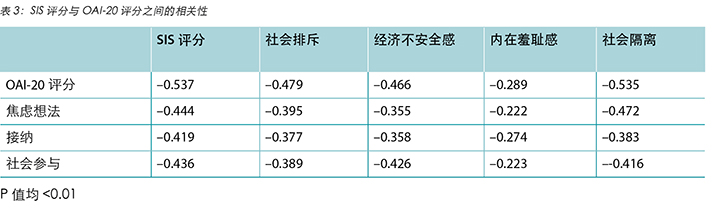

The average OAI-20 scores were 41.3±10.8. The five lowest-scoring OAI-20 items identified by respondents are that because of my stoma I: limit my range of activities; am always conscious that my stoma may leak, smell, or be noisy; am always anxious about my stoma; feel that I will always be a patient; and, feel I am no longer in control of my life. Univariate analysis showed a significant difference with the OAI-20 scores in the group in relation to differences in average income, differing lengths of time post-surgery and differing levels of self-care. The SIS total score and subscores and OAI-20 total score and the subscores were negatively correlated (r=-0.222~-0.537, all P<0.01) (Table 3).

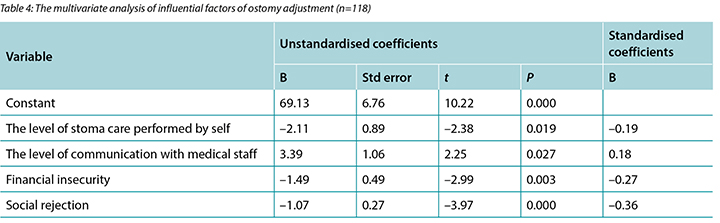

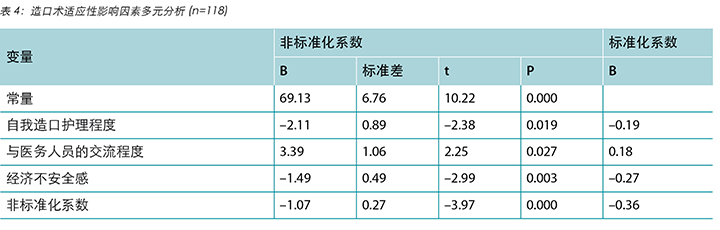

Multi-factor analysis shows that the level of stoma care performed by self, the degree of communication with medical staff, financial insecurity, and social rejection are risk factors of ostomy adjustment (Table 4).

Discussion

The level and characteristics of stigma in patients with permanent colostomy.

The scoring rate of SIS score and subdimension score were higher than 50% in this study, which is similar to the findings of Wu Yan19. They surveyed 230 patients with a permanent colostomy; the average SIS scores were 56.07±12.57, the scoring rate of SIS score was 58.42%, the scoring rate of subdimension was higher than 50%. The highest score found in this study was the financial insecurity dimension, perhaps because men accounted for 65.3% of respondents, middle-aged respondents accounted for 58.4% of study participants. Males bear most of the responsibility for family income in China. The middle-aged population is the highest aged bracket in the working population in China. Study participants felt their family roles were being challenged and jobs were affected because of the stoma. As most stoma products are not included in insurance coverage in most parts of China, most colostomy patients felt some additional economic pressure. The second highest score was the social isolation dimension, which refers to loneliness, the feeling of being isolated from healthy people, being of unequal status in relationships and social interaction, which is similar to the findings of Danielsen6. Patients also described that as their body shape changed due to the colostomy, they had lost control of their bowel excretion and therefore they felt differently to other healthy people. Under the cultural atmosphere of China advocating collectivist values, people pay attention to an individual or a group’s recognition of its social status and reputation. People with a stoma are eager to obtain social recognition20, and are focussed on doing everything possible to “save face”. Colostomy patients fear “losing face” and, therefore, feeling inferior21. This study showed that patients who communicated less frequently with medical staff scored lower than other patients. Those patients who communicated frequently with medical staff are better able to master the physical care of their stoma, keep abreast of the latest information on ostomy care and are better able to cope with various psychosocial situations.

The level of psychosocial adjustment and its correlated factors in patients with permanent colostomy

Social adjustment refers to the ability to adjust to the environment with the purpose of maintaining the best physical and mental state15. It is an active and dynamic self-adjustment process. It is also a systemic reaction, including physical, social, cultural and technical factors. Based on the score on the OAI, patients in this sample were at the medium level of adjustment, which is similar to the findings of Hu Ailing22 and Xu Qin23. In this study, the main social adjustment problems of patients with a colostomy were social activity restrictions, anxiety, pessimism, loss of self-control, and fear of leakage of the colostomy bag. The study showed that the degree of stoma self-care is an important factor in the adjustment processes, which is consistent with many studies. Patients are transferred from the hospital to the community 5–7 days after surgery. The management of the stoma and replacement of colostomy bag are activities of daily living patients will have to do for the rest of their lives. Self-care is the foundation for patients to return to society. However, the current self-care status of patients with a colostomy is not optimal. In this study, only 30.7% of patients were fully self-caring in the management of their colostomy. At present, intervention studies have been carried out in China to improve the self-care level of patients with a colostomy through such methods as telephone interventions and the peer patient program24.

This study shows that patients who are always communicating with medical professionals have higher OAI scores than other patients; this is similar to the results of Wang Miao25. The study pointed out that the health control of patients with colostomies tends to rely on health authorities and this is consistent with many related studies. It is believed that the guidance of professionals such as enterostomal therapists can improve the level of adjustment of patients with colostomies26,27. Those who are unable to communicate with health professionals are more likely to suffer from or exhibit symptoms of anxiety and depression. Therefore, enterostomal therapists should provide their hospital or outpatient contact details before the patient is discharged.

This study shows that patients’ SIS total score and subscores are negatively related to OAI-20 (–0.222~-0.537) scores. The higher the patient’s level of stigma, the lower the level of ostomy adjustment, which is similar to the finding of Dylan8, who found a significant negative correlation between the stigma, adjustment and life satisfaction. In addition, this study shows that social isolation and economic insecurity have a negative predictive effect on ostomy adjustment. The sense of social isolation makes patients think they are isolated from healthy people and that they live in an unequal state in interpersonal relationships. They are also very sensitive and minimise social activities. Patients with poor economic conditions are under more pressure as well as trying to contend with their underlying diseases and a colostomy.

Conclusion

The normal defecation method of a patient who has a colostomy is interrupted as faeces are excreted through the stoma into a colostomy bag. Sometimes there is an associated noise and unpleasant smell. Leakage of the colostomy bag may occur for numerous reasons. As human excreta can trigger adverse reactions in people in general, colostomy patients may experience or at least imagine other people’s adverse reactions. Any reaction indicative of disgust may contribute to the development of feelings of stigma. The main social adjustments to overcome were social activity restrictions, anxiety, pessimism, loss of self-control, and fear of the colostomy bag leaking. The underlying disease and resulting stoma exacerbated economic pressures on some patients.

During hospitalisation it is suggested that medical staff should teach patients the skills of ostomy care and psychological adjustment methods, as well as providing written instructions for colostomy patients. At the same time, health professionals should foster continuity of care of discharged patients through improved liaison and handover to community home nurses. By hosting fraternities and lectures regularly it is hoped that more regions in China will be able to incorporate ostomy products into medical insurance schemes as soon as possible, thereby reducing the economic pressure on ostomy patients. Overall, as much support and assistance should be given to colostomy patients to help them readjust to living with a colostomy.

As the sample size of this study was small, it is recommended that a larger, multi-regional survey and interventional study on preventing feelings of stigma in colostomy patients is conducted.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared by the authors.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

华中地区患者接受永久性结肠造口术后病耻感与适应性之间的关系

Fang-fang Xu, Wei-hua Yu, Mei Yu, Sheng-qin Wang and Gui-hua Zhou

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.1.33-39

摘要

目的:研究永久性结肠造口术后患者的病耻感与适应性之间关系。

方法:本研究共招募了118名接受永久性结肠造口术的患者(男性81例,女性37例,平均年龄57.4±15.0岁),分别来自华中地区六所三甲医院。参与者完成了一项调查问卷以获得社会人口统计学数据、社会影响量表(SIS)评分以确定病耻感水平和造口术适应性量表(OAI-20)评分以确定心理适应性水平。

结果:患者的平均SIS评分为60.7±10.4。QAI-20 总评分为 41.3±10.8。SIS总评分和 SIS单项评分与QAI-20 总评分和单项评分呈负相关(r=-0.222~-0.537,P值均<0.01)。多元回归分析显示,将造口自我护理水平、与医务人员的交流程度、经济上的不安全感和社会排斥添加至回归方程中时,对OAI-20有显著负性影响。

结论:研究样本的SIS评分高于平均SIS评分的中点,表示病耻感与造口术适应性之间密切相关。有人建议,专业医务人员需要更多地关注患者所表现出的病耻感,以便提高患者适应结肠造口术后的生活的能力。

前言

结肠造口术是指在大肠上造口,通过腹壁上的一个人工开口引出一段大肠,以便绕过受损的大肠部分。结肠造口术通常用于治疗消化系统疾病,如结直肠癌、炎症性肠病和憩室炎,或者因为创伤而需要绕过一段受损的结肠。

结直肠癌是进行结肠造口术的主要原因。2014 年WHO世界癌症报告显示,在过去的五年里,结直肠癌在所有癌症中占10.9%,仅次于第二位的乳腺癌(19.2%)和第三位的前列腺癌(12.1%)1。结直肠癌的发病率在中国的所有癌症中占第五位2,在中国城市人口所患癌症中占第四位3。

结肠造口术后,因为排便方式发生改变,患者会无法控制排便。另外,他们需要佩戴一个结肠造口袋,以便收集排泄物,因此会时刻担心结肠造口袋泄漏,带来不悦的气味和声响。结肠造口的存在会对患者的日常生活、性生活和总体生活方式造成不利影响,因为他们的体形和身体功能已发生改变4-5。某些患者将他们的结肠造口术视为禁忌话题,并且害怕被人发现以及不得不暴露他们身上有造口。患者通常会过于害怕或羞于公开谈论他们接受的结肠造口术。他们会因为结肠造口的存在而产生病耻感6。

病耻感是指一种感知到或实际存在的羞耻感或者一种丢脸的、使人远离他人的感觉。它代表了由于缺陷或残障而不受人欢迎的人。Goffman于1963年在心理学领域引入病耻感一词7。与疾病有关的病耻感是指患者由于患有疾病而自内心产生的一种羞耻感觉。这是一种被人贴标签、歧视和贬低的感觉。它指的是个体由于无法被人理解和接受而实施的疏离和回避8,9。Goffman认为,如果患者有身体改变、缺陷或畸形以及患严重疾病等特征,则更容易产生病耻感。许多学者已研究了与病耻感有关的各种疾病,其中包括精神疾病、艾滋病、癌症、失禁、结肠癌和肥胖8,10-12。英国的MacDonald和Anderson调查了420位直肠癌患者,其中256位接受过结肠造口术。在接受过结肠造口术的患者中,一半患者有病耻感,尤其是年轻患者13。Smith研究了195位接受过结肠造口术的患者,发现对造口的厌恶与如何适应拥有结肠造口术和总体生活满意度呈负相关14。丹麦的Danielsen等人发现,15位接受过结肠造口术的患者难以向人披露他们接受过结肠造口术,因为这可能会影响他们的声誉。因此,他们试图减少日常外出活动,使自己与世隔绝6。

与疾病有关的病耻感成为预测疾病适应性和生活质量的一个有力指标,但是,在中国,病耻感的研究主要侧重于精神疾病。关于结肠造口术后的病耻感研究几乎没有。

社交适应性是指个体适应或改变环境的能力,以便使其身体和精神状态保持最佳状态。社交适应性是一种积极主动的动态自我适应过程,具有系统性,包括生理学、心理学、社会文化因素和环境方面14。接受结肠造口术后的患者会面临各种适应性问题,包括生理、心理和社会文化方面。

与结肠造口术患者有关的病耻感水平和特征,以及患者自身的病耻感和通过社会调节的适应是否会相互影响,都是值得深入探讨的问题。中国目前缺乏关于造口术的病耻感(感知到的或实际的)的研究,尤其是关于结肠造口术后的患者。因此,本研究旨在调查结肠造口术后患者中的病耻感水平和社会适应性,分析病耻感和适应性之间的关系,为临床护理干预提供客观依据。

方法

参与者

参与者为2016年12月至2017年6月期间来自华中地区六所三甲医院造口治疗科的患者,通过便利采样方式参加此项研究。

纳入和排除标准

纳入研究的患者必须满足以下标准:

- 年满18岁;

- 接受过结肠造口术;

- 结肠造口术后一个月或以上,处于康复期;

- 可以提供参加此项研究的知情同意书;

- 可以阅读和理解中文。

排除标准

排除存在认知障碍、转移性肿瘤和其他危及生命的严重疾病的患者。

调查程序

在本研究中,研究人员为各自医院的造口治疗师和省级造口治疗专业护士。作者就如何开展调查培训了研究人员。培训包括向研究人员详细解释如何向潜在的研究参与者传达调查的目的、调查所使用的测量的方法以及问卷的详情。开展研究时,研究人员遵循统一的调查方案。其中包括采用统一的指导说明、及时回复参与者的提问、和数据输入和验证流程,以确保数据准确。参与者以匿名方式回答问卷中的问题。

测量

调查问卷

调查问卷由作者编制。问卷由12个问题组成,包括年龄、性别、教育背景、收入水平、家庭住址、生活状态、平均月收入、术后时间、医疗支付方式、造口术耗材每月费用、由谁实施造口护理、造口/造口周围并发症、和与医务人员的交流。

社会影响量表(SIS)

SIS被广泛用于癌症和其他慢性疾病,以便测量相关的病耻感水平。在本研究中,作者和研究人员使用SIS测量患者在结肠造口术后的病耻感水平。SIS由Fife和Wright于2000年编制,2007年被Pan等人翻译成中文15。该量表包括24个条目,4个维度:社会排斥、经济不安全感、内在羞耻感、社会隔离。每个条目采用 1(非常不同意)至 4(非常同意)评分。评分越高表明病耻感水平越高。Guan Xiao Meng等人在既往研究中采用SIS获得的Cronbach α系数为0.88316。在开展研究之前,对于使用中文版SIS工具,作者获得了Pan的同意。本研究的Cronbach α系数为0.915。

造口术适应性量表(OAI-20)

OAI-20由Simmons 等人17开发,用于评估造口术后患者的心理适应性。最初量表包括23个条目和四个子因素。每个条目采用 1(非常不同意)至 4(非常同意)评分。评分越高表明社会适应性越好。该量表由Gao Wen Jun等人于2011年翻译成中文,包括20个条目和三个子因素18本研究的Cronbach α系数为0.886。

数据分析

采用Epidata 3.1 (Epidata Association Freeware) 实施数据输入(QES文件),开发归档协议(REC文件)和数据验证/恢复(CHK文件)。采用IBM (2011) SPSS20.0 进行统计数据分析。

一般信息按简单频率和百分比描述。SIS评分和OAI-20评分按中位值、平均数和标准差描述。组间比较采用T检验或单向ANOVA分析检验。SIS评分和OAI-20评分之间的相关性采用Pearson相关分析检验。

采用多元回归分析探讨影响造口术适应性的相关因素。P<0.05 表示有统计学显著性。

结果

参与者人口统计学特征和造口相关信息

本研究共入组118位患者。参与者的平均年龄为57.4±15.0岁。81(68.6%)位男性同意参加研究。研究参与者的其他特征见表1。

社会影响和造口术适应性调查结果

平均SIS评分为60.7±10.4。评分率为63.2%。社会排斥、经济不安全感、内在羞耻感、社会隔离维度的评分分别为21.8±4.3 (60.6%)、8.0±1.9 (66.7%)、12.7±2.5 (63.5%) 和18.2±3.6 (65%),括号内为回答率。单因素分析显示,与医务人员交流的程度不同,该组的SIS评分有显著差异。从未与医务人员交流的患者评分高于其他患者(表2)。

平均OAI-20评分为41.3±10.8。参与者回答的五个评分最低的OAI-20条目包括,因为我有造口:我会减少我的活动范围;时刻意识到自己的造口可能会泄漏、有异味或有响声;因造口而时刻焦虑;感觉我永远会是个患者;感觉我不再能够掌控自己的生活。单因素分析显示,在平均收入差异、不同的术后时间和不同的自我护理水平方面,OAI-20评分有显著差异。SIS 总评分和子分数和OAI-20总评分和子分数均负相关(r=-0.222~ -0.537,P值均<0.01)(表3)。

多因素分析显示,自我护理造口程度、与医务人员交流的程度、经济不安全感和社会排斥是造口术适应的风险因素(表4)。

讨论

永久性结肠造口术后患者的病耻感水平和特征

在本研究中,SIS量表和子维度的评分率高于50%,与Wu Yan的结果相似19。Wu Yan等人调查了230位接受永久性结肠造口术的患者,平均SIS评分为56.07±12.57, SIS量表的评分率为58.42%,子维度的评分率高于50%。在本研究中,经济不安全感维度的评分最高,可能是因为调查回答者中男性占65.3%,中年人占参与者的58.4%。在中国,男性对家庭收入承担大部分责任。中年人口在中国劳动人口中所占比例最高。研究参与者认为,因为造口术,他们的家庭角色受到挑战,工作受到影响。因为在中国的大部分地区,大多数造口耗材未包括在医保范围内,大多数结肠造口术患者感觉到某些额外的经济压力。第二高评分是社会隔离维度,该维度是指孤独、与健康人群隔离的感觉、在人际关系和社会交往中受到不平等对待,与Danielsen等人的发现类似6。患者还描述说,由于结肠造口术,他们的体型发生改变,无法控制排便,因此感觉与其他健康人不同。在注重集体价值的中国文化氛围下,人们在意个人或集体对其社会地位和声誉的认同。接受造口术的患者急切渴望获得社会认可20,并专注于尽一切努力“保全面子”。接受结肠造口术的患者怕“丢脸”,因此感到自卑21。本研究显示,与其他患者相比,不经常与医务人员交流的患者的评分较低。那些经常与医务人员交流的患者能够更好地掌握造口护理,及时获得关于造口护理的最新信息,能够更好地应对各种心理社会情境。

接受永久性结肠造口术的患者的社会心理适应性及其相关因素

社会适应性是指适应环境以便保持最佳身体和精神状态的能力15。这是一个主动和动态的自我适应过程。这也是一个系统性反应,包括身体、社交、文化和技术因素。基于OAI评分,该样本中患者的适应性处于中等水平,与Hu Ailing22 和 Xu Qin23的发现相似。在本研究中,接受结肠造口术后患者的主要社会适应性问题是社会活动限制、焦虑、悲观、失去自我控制和害怕结肠造口袋泄漏。本研究显示,自我护理造口的程度是适应过程中的一个重要因素,这与多项研究一致。患者在术后5至7天从医院转至社区。造口管理和更换造口袋是患者在余生中必须要做的日常活动。自我护理是患者重返社会的基础。但是,目前,患者在结肠造口术后的自我护理状态并不理想。在本研究中,只有30.7%的患者可以在结肠造口术后完全自我护理。目前,已在中国开展干预性研究,通过各种方法(如电话干预和同病患者计划)提高患者在结肠造口术后的自我护理24。

本研究显示,始终与医务人员交流的患者的OAI评分比其他患者高,这与Wang Miao25的结果相似。根据本研究,结肠造口术后患者的健康控制倾向于依赖卫生当局,这与许多相关研究一致。据信,医务人员(如造口治疗师)的指导可以提高患者在结肠造口术后的适应水平26,27。那些无法与医务人员交流的患者更容易患上或表现出焦虑和抑郁症状。因此,在患者出院之前,造口治疗师应该为患者提供他们的医院或门诊联系方式。

本研究显示,患者的SIS总评分和子评分与OAI-20 (–0.222 至 -0.537)呈负相关。患者的病耻感越高,造口术适应水平越低,这与Dylan的发现一致8。Dylan发现,病耻感与适应水平和生活满足感呈显著负相关。此外,本研究表明,社会隔离和经济不安全感对造口术适应水平具有负面预测作用。患者会因为社会隔离感认为他们与健康人群隔离,在人际关系中处于不平等的状态。他们还会非常敏感,最大限度地减少社交活动。经济条件不好的患者在应对他们的基础疾病和结肠造口术时会有更大压力。

结论

接受结肠造口术后,患者的正常排便方式被中断,因为粪便从造口排入结肠造口袋中。有时会产生声响和异味。结肠造口袋会因多种原因泄漏。因为人类排泄物一般会在人群引发产生令人厌恶的印象,结肠造口术后患者可能会遇到或至少想象到他人对其厌恶的印象。任何表示厌恶的反应都可能会促进患者产生病耻感。要克服的主要社会适应性问题是社交活动限制、焦虑、悲观、失去自我控制和害怕结肠造口袋泄漏。对于某些患者来说,基础疾病和由此带来的造口加重了他们的经济压力。

在结肠造口术患者住院期间,建议医务人员向患者教授造口护理技能和心理适应方法,并提供书面指导。与此同时,医务人员应该通过加强与社区护士之间的联络和移交工作,促进患者出院后护理的连续性。定期举行联谊会和讲座,希望中国更多地区可以尽快将造口术耗材纳入医保计划,从而减轻造口术患者的经济压力。总体而言,应给予结肠造口术患者尽可能多的支持和帮助,以帮助他们重新适应结肠造口术后生活。

由于本研究的样本量较小,建议就防止结肠造口术患者中的病耻感而开展大型、多地区的调查和干预性研究。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Fang-fang Xu

ET nurse, Wound and Stoma Care Department,

The No. 1 People’s Hospital of Hefei City, Anhui Province, China

Wei-hua Yu

The Director of Nursing Department,

The No. 1 People’s Hospital of Hefei City, Anhui Province, China

Mei Yu

The Vice-Director of Nursing Department,

The No. 1 People’s Hospital of Hefei City, Anhui Province, China

Sheng-qin Wang

ET nurse, Wound and Stoma Care Department,

The No. 1 People’s Hospital of Hefei City, Anhui Province, China

Gui-hua Zhou

ET nurse, Wound and Stoma Care Department,

The No. 1 People’s Hospital of Hefei City, Anhui Province, China

Correspondence to: Fang-fang Xu

Email 784597400@qq.com

References

- Bernard WS, Christopher PW, Freddie B et al. World Cancer Report. International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO; 2014.

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11 [EB/OL]. [2014 Dec 21]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr.

- He J & Chen WQ. 2012 China Cancer Register Annual Report [M]. Beijing: Military Medical Science Press, 2012; 10.

- Reese JB, Finan PH, Haythornthwaite JA et al. Gastrointestinal ostomies and sexual outcomes: a comparison of colorectal cancer patients by ostomy status [J]. Support Care Cancer 2014; 22(2):461–8.

- Desnoo L & Faithfull S. A qualitative study of anterior resection syndrome: the experiences of cancer survivors who have undergone resection surgery. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2006; 15(3):244–51.

- Danielsen AK, Soerensen EE, Burcharth K et al. Learning to live with a permanent intestinal ostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013; 40(4):407–412.

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall, 1963.

- Smith DM, Loewenstein G, Rozin P et al. Sensitivity to disgust, stigma and adjustment to life with a colostomy. J Res Pers 2007; 41:787–803.

- Scambler C. Stigma and disease: changing paradigms. Lancet 1988; 352:1054–1055.

- Kira IA, Lewandowski L, Ashby JS et al. The traumatogenic dynamics of internalized stigma of mental illness among Arab American, Muslim, and refugee clients. Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2014; 20(4):250–266.

- Tsai AC, Weiser SD, Steward WT et al. Evidence for the reliability and validity of the internalized AIDS-related stigma scale in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav 2013; 17(1):427–33.

- Cataldo JK, Jahan TM & Pongquan VL. Lung cancer stigma, depression, and quality of life among ever and never smokers. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012; 16(3):264–9.

- MacDonald LD & Anderson HR. Stigma in patients with rectal cancer: a community study. J Epidemiol Community Health 1984; 38:284–290.

- Andrews H & Roy C. The Roy adaptation model the definitive statement. Norwalk: Appleton & Lange, 1991; 22–59.

- Pan AW, Chung LI, Fife BL et al. Evaluation of the psychometrics of the Social Impact Scale: a measure of stigmatization. Int J Rehabil Res 2007; 30(3):235–238.

- Guan XM, Sun T, Yang H et al. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the social impact scale for stigma in patients with incontinence. J Nurs Sci 2011; (07):63–65.

- Simmons KL, Smith JA & Maekawa A. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Ostomy Adjustment Inventory-23. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2009; 36(1):69–76.

- Gao WJ & Yuan CR. The reliability and validity of Chinese version of stoma adaptation scale. Chinese Journal of Nursing 2011; 46(8):811–813.

- Wu Y, Miao ZH & Xu JM. Investigation of stigma status in patients with permanent colostomy. J Nurs Res 2015; 29(2B):170–173.

- Zhou LG. On Social Exclusion. J Society 2004; 27(3):58–60.

- Pan RC. Through the movie “face” to see the difference between Chinese and Western views. J Movie Literature 2012; 19:48–49.

- Hu AL. Adaptation of self-care ability and social support in patients with colostomy. Guangzhou: Sun Yat-sen University, 2008.

- Xu Q, Cheng F, Dai XD et al. Psychological and social adaptation and related factors in patients with permanent colostomy analysis. Chinese Journal of Nursing 2010; 45(10):883–885.

- Cheng F, Xu Q, Dai XD et al. Effects of the implementation of the internal patient plan on the self-efficacy and self-management of patients with permanent colostomy. Chinese Journal of Practical Nursing 2010; 26(1):45–47.

- Wang M, Zhu XL, Wang CY et al. Control source, quality of life, and coping style of patients with rectal cancer and stoma. Chinese Mental Health Journal 2013; 23(10):750–753.

- Haugen V, Bliss DZ & Savik K. Perioperative factors that affect long-term adjustment to an incontinent ostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2006; 33(5):525–535.

- Sinclair L. Young adults with permanent ileostomies: experiences during the first 4 years after surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2009; 36(3):306–316.