Volume 41 Number 2

Practice Implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020

Laurent O. Chabal, Jennifer L. Prentice and Elizabeth A. Ayello

Keywords ostomy, education, stoma, culture, guideline, International Ostomy Guideline, IOG, ostomy care, peristomal skin complication, religion, stoma site, teaching

For referencing Chabal LO et al. Practice Implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020. WCET® Journal 2021;41(2):10-21

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.2.10-21

Abstract

The second edition of the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline (IOG) was launched in December 2020 as an update to the original guideline published in 2014. The purpose of this article is to introduce the 15 recommendations covering four key arenas (education, holistic aspects, and pre- and postoperative care) and summarise key concepts for clinicians to customise for translation into their practice. The article also includes information about the impact of the novel coronavirus 2019 on ostomy care.

Acknowledgments

The WCET® would like to thank all of the peer reviewers and organizations that provided comments and contributions to the International Ostomy Guideline 2020. Although the WCET® gratefully acknowledges the educational grant received from Hollister to support the IOG 2020 development, the guideline is the sole independent work of the WCET® and was not influenced in any way by the company who provided the unrestricted educational grant.

The authors, faculty, staff, and planners, including spouses/partners (if any), in any position to control the content of this CME/NCPD activity have disclosed that they have no financial relationships with, or financial interests in, any commercial companies relevant to this educational activity.

To earn CME credit, you must read the CME article and complete the quiz online, answering at least 7 of the 10 questions correctly. This continuing educational activity will expire for physicians on May 31, 2023, and for nurses June 3, 2023. All tests are now online only; take the test at http://cme.lww.com for physicians and www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC for nurses. Complete NCPD/CME information is on the last page of this article.

© Advances in Skin & Wound Care and the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists.

Introduction

Guidelines are living, dynamic documents that need review and updating, typically every 5 years to keep up with new evidence. Therefore, in December 2020, the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® (WCET®) published the second edition of its International Ostomy Guideline (IOG).1 The IOG 2020 builds on the initial IOG guideline published in 2014.2 Hundreds of references provided the basis for the literature search of articles published from May 2013 to December 2019. The guideline uses several internationally recognised terms to indicate providers who have specialised knowledge in ostomy care, including ET/stoma/ostomy nurses and clinicians.1 However, for the purposes of this article, the authors will use “ostomy clinicians” and “person with an ostomy” to be consistent.

Guideline development

A detailed description of the IOG 2020 guideline methodology can be found elsewhere.1 Briefly, the process included a search of the literature published in English from May 2013 to December 2019 by the authors of this article, who comprise the Guideline Development Panel. More than 340 articles were reviewed. For each article identified, a member of the panel would write a summary, and all three would then confirm or revise the ranking of the article evidence. The evidence was categorised and defined and compiled into a table that is included in the guideline and can be accessed on the WCET® website. The strength of recommendations were rated using an alphabetical system (A+, A, A−, etc). Feedback was sought from the global ostomy community, and 146 individuals and 45 organizations were invited to comment on the findings. Of these, 104 individuals and 22 organizations returned comments, which were used to finalise the guideline.

Guideline overview

Because the WCET® is an international association with members in more than 65 countries, there is a strong emphasis on diversity of culture, religion, and resource levels so that the IOG 2020 can be applied in both resource-abundant and resource-challenged countries. The forward was written by Dr Larry Purnell, author of the Purnell Model for Cultural Competence (unconsciously incompetent, consciously incompetent, consciously competent, unconsciously competent).3-5 As with the 2014 guideline, the WCET® members and International Delegates were invited to submit culture reports from their country, and 22 were received and incorporated into the guideline development.

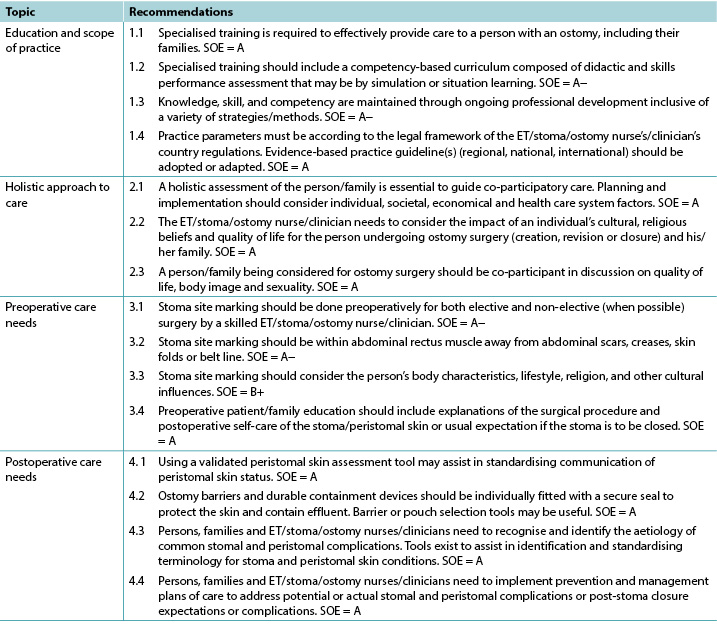

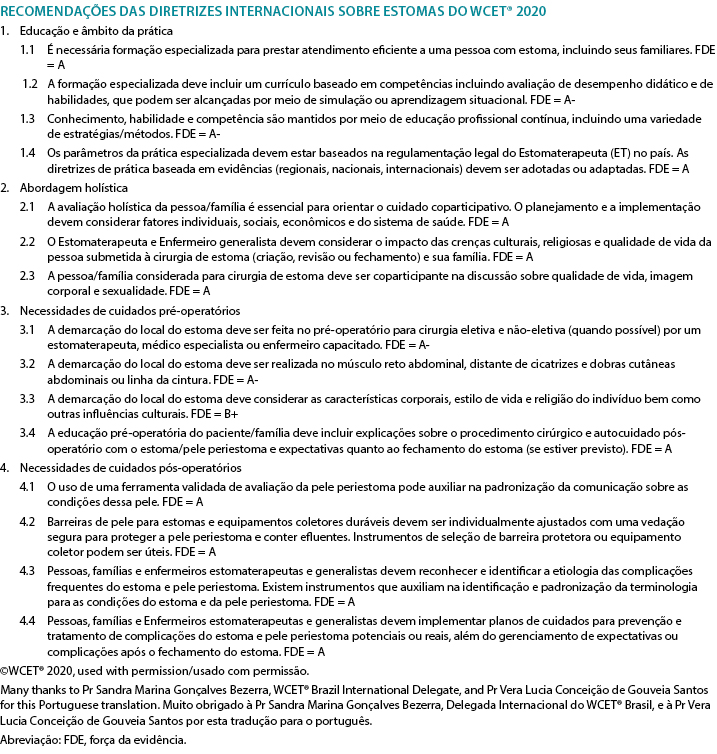

Because the IOG 2020 is intended to serve as a guide for clinicians in delivering care for persons with an ostomy, new to this edition is a section on guideline implementation. Also new is a recommendation for nursing education. A glossary of terms and helpful educational resources are also included in the various appendices. The 15 IOG 2020 recommendations are listed in Table 1. The recommendations have been translated into Chinese (Supplemental Table 1), French (Supplemental Table 2), Portuguese (Supplemental Table 3), and Spanish (Supplemental Table 4) and are also available on the WCET® website (www.wcetn.org).

Table 1 WCET® International OStomy Guideline 2020 Recommendations

©WCET® 2020, used with permission.

Abbreviations: ET, enterostomal therapy; SOE, strength of evidence.

Education

The evidence supports four IOG 2020 recommendations about education (Table 1). A person who has surgery resulting in the creation of an ostomy needs knowledge regarding their type of stoma, care strategies such as ostomy pouches, and the impact the ostomy will have on their lifestyle.6 Accordingly, the needs of these patients go beyond what may be taught in initial nursing education programs. Zimnicki and Pieper7 surveyed nursing students and found that just under half (47.8%) did not have experience in caring for a patient with an ostomy. For those who did, they felt most confident in pouch emptying.7 Findings by Cross and colleagues8 also support that staff nurses without specialised ostomy education felt more confident in emptying the ostomy pouch as opposed to other ostomy care skills. Duruk and Uçar9 in Turkey and Li and colleagues10 in China also reveal that staff nurses lack adequate knowledge about the care of patients with ostomies. Better ostomy care outcomes have been reported when patients are cared for by nurses who have had specialised ostomy education. This includes research in Spain by Coca and colleagues,11 Japan by Chikubu and Oike,12 and the UK by Jones.13

For over 40 years, the WCET® has promoted the importance of specialised ostomy education for nurses to better meet the needs of patients and their families.6 Other societies such as the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society in the US; Nurses Specialised in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada; and the Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK have also advocated for specialised nursing education. The suggested modifications include competence-based curricula and checklists of skills and professional performance necessary for the specialised nurse to provide appropriate care to patients with an ostomy and their families.14-17 Evidence-based practice requires that healthcare professionals keep abreast of new techniques, skills, and knowledge; lifelong learning is necessary.

Holistic aspects of care: culture and religion

The literature supports three highly ranked recommendations related to holistic care within the IOG 2020 (Table 1) and confirms the necessity of taking them into account when caring for individuals with an ostomy.

Ostomies can impact individuals in different domains such as day-to-day life, overall quality of life, social relationships, work, intimacy, and self-esteem. A holistic approach to care aims to acknowledge and address the patient’s need at a physiological, psychological, sociological, spiritual, and cultural level,18 especially when the patient’s situation is complex.19 Therefore, implementing a holistic approach to practice is crucial to address all of the potential issues.20

Many tools exist to assess patients’ quality of life, self-care adjustment, social adaptation, and/or psychological status.21,22 They provide important information to nurses in their clinical decisions making, although as always clinical judgment remains relevant. Because holistic care is multidimensional, using various methods will allow an integrative and global approach to caring for patients with ostomies.

The World Health Organization’s definition of health23 is still relevant today. An individual’s origins, beliefs, religion, culture, gender, and age will influence his/her interpretation of illness and diseases.24-26 For healthcare professionals, the need to understand these influences and their real impacts on the patient, family, and/or caregiver(s) is essential because it will provide key information to co-construct ostomy care.

Dr Larry Purnell’s Model for Cultural Competence3,4 can be readily applied to ostomy care.5 It can help nurses to deliver culturally competent care to patients with an ostomy. Integrating effective cultural competence will improve relationships among patients, families, and healthcare professionals,27 especially if patients and/or families are finding it difficult to cope.28

Specialised and nonspecialised nurses have a key role in patient, family, and caregiver education.29 They will, step by step, help support the development of specific skills and implementation of personalised adaptive strategies. Nurses’ advice and support can decrease ostomy-related complications,13,30,31 and listening to and addressing patient emotions will improve individuals’ self-care.32

Taking into account the International Charter of Ostomate Rights33 during provision of ostomy care will increase patients’ quality of life, because it supports patient empowerment and reinforces the partnerships among patients, families, caregivers, and healthcare professionals.

Section 6 of the IOG 2020 provides an international perspective on ostomy care. With contributions from 22 countries, this version is more inclusive than the previous one.2 It is the authors’ hope that it will help ostomy clinicians around the world when taking care of patients from another culture, background, or belief system and therefore give them better skills to address each individual’s needs.

Preoperative Care And Stoma Site Marking

As seen in Table 1, there are four recommendations that address preoperative care and stoma site marking. The literature emphasises preoperative education for patients who are about to undergo ostomy surgery, which includes preoperative site marking. Fewer complications are seen in persons who have their stoma sites marked before surgery.34,35

Because specialised nurses may not be available 24/7, patients who undergo unplanned/emergency surgery may not benefit from preoperative education and stoma site marking. Accordingly, the literature supports the training of physicians and nonspecialty nurses to do stoma site marking.34-37 Zimnicki36 completed a quality improvement project to train nonspecialised nurses in stoma site marking. This project significantly increased the number of patients who had preoperative stoma site marking and education.36

Stoma site marking is an important art and skill that is beyond the scope of this article to describe in detail. Major principles include observation of the patient’s abdomen while standing, sitting, bending over, and lying down (Figure 1).37-41 There are at least two techniques for identifying the ideal abdominal location.42-52 Those interested might consult the references42-60 as well as the WCET® webinar or pocket guide on stoma site marking (www.wcetn.org).52

Assess the abdomen in multiple positions when doing stoma siting

Figure 1 positions for stoma site marking ©2021 Ayello, used with permission.

Postoperative Care

The IOG 2020 lists four recommendations for postoperative care to assist ostomy clinicians to detect, prevent, or manage and thereby minimise the effect of any peristomal complications (Table 1).

Successful postoperative recovery following ostomy surgery is dependent on multiple factors from the perspective of both the ostomy clinician and person with an ostomy. All members of the care team, including the patient, must have a heightened awareness of preventive or remedial strategies for common problems that may occur with the formation of a new stoma, refashioning of an existing stoma, or stoma closure. The ability to recognise and effectively manage potential or actual postoperative ostomy and peristomal skin complications (PSCs) has inherent short- and long-term ramifications for the health, well-being, and independence of the persons with an ostomy61-63 and for health resource management.64-66

Postoperative ostomy complications may manifest as early or late presentations. Early complications such as mucocutaneous separation, retraction, stomal necrosis, parastomal abscess, or dermatitis may occur within 30 days of surgery. Later complications include parastomal hernias (PHs) and stomal prolapse, retraction, or stenosis.63,67,68

However, the most common postoperative complications are PSCs.69 Frequently cited causes of PSCs are leakage,70,71 no preoperative stoma siting,35 poor surgical construction techniques,72 ill-fitting appliances, and long wear time of appliances.71,73

Common PSCs include acute and chronic irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis, the former arising from prolonged contact with feces or urine on the skin eventually causing erosion (Figure 2). Assessment of the abdomen, stoma, stoma appliance, and accessories in use as well as the patient’s ability to care for the stoma and correctly reapply his/her appliance is essential to determine the cause of leaks. Skin care, depending on the severity of irritation or denudation, may involve the use protective pectin-based powders or pastes, skin sealants (acrylate copolymer or cyanoacrylates wipes or sprays), and protective skin barriers. Adjustments to the type of appliance used and wear time may also be required ameliorate acute and prevent chronic irritant contact dermatitis.61,70,74

Figure 2 irritant dermatitis ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

Allergic contact dermatitis results from an adverse reaction to substances within products applied to the skin during cleansing or skin protection used prior to appliance application or removal or that are part of the appliance itself.74,75 Compromised skin usually reflects the shape of the appliance if it is the allergen or the area where secondary skin care products have been used. Affected skin may have the appearance of a rash; be reddened, blistered, itchy, or painful; or exude hemoserous fluid (Figure 3). Patch testing small areas of skin well away from compromised skin and the stoma may be required to identify specific causative agents and/or assess the suitability of other skin barrier products used to gain a secure seal around the stoma.70,75

Figure 3 allergic contact dermatitis ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

Parastomal hernias are a latent complication that also contributes to PSCs. Causes include surgical technique, the size and type of stoma, abdominal girth, and age and medical conditions such as prior hernias and diverticulitis fluid. Education of surgeons and prophylactic insertion of polypropylene mesh during surgery as well as postoperative patient education may decrease PH incidence (Figure 4).68,76,77 Further, providers must assess and measure the patient’s abdomen at the level of the stoma to choose the most appropriate support garment required to manage the degree of PH protrusion, prevent further exacerbation, and allow the stoma to continue to function normally.78 The ostomy appliance/pouch in use will also need to be frequently reassessed to address any changes in the size of the stoma.

Figure 4 parastomal hernia ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

The IOG 2020 cites numerous tools that ostomy clinicians can use to effectively identify and classify PSCs79,80,81 and select appropriate skin barriers and appliances to manage PSCs.62,82

Finally, of increasing importance to improve the postoperative quality of life of individuals with an ostomy, reduce ostomy complications and associated readmissions, and enhance interprofessional practice are the use of early or enhanced recovery programs after surgery,83,84 ongoing education and discharge monitoring programs,68,85 and telehealth modalities for counseling and remote consultation.86,87

Guideline implementation

For clinical guidelines to result in positive outcomes for the intended patient populations, the proposed recommendations need to be adopted into daily practice. Multiple strategies are required to facilitate adoption,88,89 and guidelines should be reviewed and adapted for specific clinical contexts.90 Prior thought, therefore, is required regarding how guidelines will be disseminated and implemented. Potential barriers to guideline implementation may include a lack of resources, competing health agendas, or a perceived lack of interest in ostomy care as a medical/nursing subspecialty with no “champion” to advocate for and facilitate implementation. Last, guidelines may be seen as too prescriptive. The section on guideline implementation within the IOG 2020 provides advice, and readers are directed to the full guideline for more information.

Impact of Covid-19 on ostomy care

The review of the evidence for the IOG 2020 preceded the advent the novel coronavirus 2019. During the pandemic, there have been anecdotal reports of ostomy clinicians being reassigned to care for other patients. The extent and impact of this have yet to be researched. In the meantime, virtual visits may provide a safe alternative to in-person care for patients and providers.91 A study by White and colleagues92 reported on the feasibility of virtual visits for persons with new ostomies; 90% of patients felt that these visits were helpful in managing their ostomy.92 However, another study found that only 32% of the respondents knew that telehealth was an option.93 Further, 71% “did not think [their issue] was serious enough to seek assistance from a healthcare professional,”93 although 57% reported some peristomal skin occurrence during the pandemic.93 In descending order, the types of skin issues reported were redness or rash (79%), itching (38%), open skin (21%), bleeding (19%), and other concerns (7%).93

Conclusions

The IOG 2020 aims to provide clinicians with an evidence framework upon which to base their practice. The 15 IOG 2020 recommendations are applicable in countries where resources are abundant (nurses and healthcare professionals trained in ostomy care with manufactured appliances/pouches), as well as in countries with limited resources (nonspecialised nurses, healthcare professionals, and laypersons who create ostomy equipment from available local resources to contain the ostomy effluent). Specialised knowledge is needed to assist persons with an ostomy in learning how to apply, empty, and change their appliance/pouch, but living with an ostomy is more than that. All aspects of the patient need to be considered.

Holistic patient care should be individualised and address diet, activities of daily living, sexual life, prayer, work, medications, body image, and other patient-centered concerns. Preoperative stoma siting has been linked to better postoperative outcomes. Early identification and intervention for PSCs requires adequate teaching, as well as awareness of when to seek professional help. Nurses who have specialised knowledge in ostomy care can improve quality of life for persons with an ostomy, including those who experience PSCs.95 It is the authors’ hope that the IOG 2020 will enhance care outcomes and rehabilitation for this population.

Practice pearls

- Patients who are cared for by healthcare professionals with specialised ostomy knowledge experience better care outcomes.

- There are clinical tools to assist with peristomal skin assessment and appliance requirements.

- Pre- and postoperative patient and family education needs to be holistic and individualised.

- Patients who undergo presurgical stoma siting experience fewer complications.

- The most common PSC is leakage leading to irritant dermatitis.

- Telehealth and remote consultation might be advantageous in providing adjunct guidance to people with ostomies.

Implicações práticas da WCET® Guia Internacional para a Ostomia 2020

Laurent O. Chabal, Jennifer L. Prentice and Elizabeth A. Ayello

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.2.10-21

Resumo

A segunda edição da WCET® Guia Internacional para a Ostomia (IOG) foi lançada em dezembro de 2020 como uma atualização da diretriz original publicada em 2014. O objetivo deste artigo é o de introduzir as 15 recomendações que cobrem quatro áreas chave (educação, aspetos holísticos e cuidados pré e pós-operatórios) e resumir conceitos chave para os clínicos personalizarem a sua aplicação nas suas práticas. O artigo também inclui informação sobre o impacto do novo coronavírus 2019 nos cuidados de ostomia.

Agradecimentos

A WCET® gostaria de agradecer a todos os revisores e organizações que forneceram comentários e contribuições para a Guia Internacional para a Ostomia 2020. Embora a WCET® reconheça agradecidamente a bolsa educativa recebida da Hollister para apoiar o desenvolvimento do IOG 2020, a diretriz é o único trabalho independente da WCET® e este não foi influenciado de forma alguma pela empresa que concedeu a bolsa educativa ilimitada.

Os autores, faculdade, equipa e planificadores, incluindo cônjuges/parceiros (se existirem), em qualquer posição de controle do conteúdo desta atividade CME/NCPD, declararam que não têm relações nem interesses financeiros em nenhuma empresa comercial relacionada com esta atividade educativa.

Para ganhar créditos CME, deve ler o artigo CME e completar o questionário online, respondendo corretamente a pelo menos 7 das 10 questões. Esta atividade educacional contínua expirará para médicos a 31 de maio de 2023 e para enfermeiros a 3 de junho de 2023. Todos os testes estão agora unicamente online; faça o teste em http://cme.lww.com para médicos e em www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC para enfermeiros. A informação completa sobre NCPD/CME encontra-se na última página deste artigo.

© Avanços em Cuidados de Pele e de Feridas e o Conselho Mundial de Terapeutas Enterostomais.

Introdução

As diretrizes são documentos vivos, dinâmicos que precisam de ser revistos e atualizados, normalmente de 5 em 5 anos, para se manterem a par de novas evidências. Por conseguinte, em dezembro de 2020, o Conselho Mundial de Terapeutas Enterostomais® (WCET®) publicou a segunda edição da sua Guia Internacional para a Ostomia (IOG).1 A IOG 2020 baseia-se na diretriz inicial da IOG publicada em 2014.2 Centenas de referências forneceram a base para a pesquisa bibliográfica de artigos publicados desde Maio de 2013 até Dezembro de 2019. A diretriz utiliza vários termos reconhecidos internacionalmente para indicar os prestadores que possuem conhecimentos especializados em cuidados de ostomia, incluindo enfermeiros e clínicos de ET/estoma/ostomia.1 Contudo, para efeitos deste artigo, os autores utilizarão "clínicos de ostomia" e "pessoa com uma ostomia" para serem consistentes.

Desenvolvimento das Diretrizes

Uma descrição detalhada da metodologia da diretriz IOG 2020 pode ser encontrada em outro local.1 Resumidamente, o processo incluiu uma pesquisa da literatura publicada em Inglês de Maio de 2013 a Dezembro de 2019 efetuada pelos autores deste artigo, os quais constituem o Painel de Desenvolvimento das Diretrizes. Foram revistos mais de 340 artigos. Para cada artigo identificado, um membro do painel tinha de escrever um resumo e todos os três confirmariam ou reveriam a classificação das provas do artigo. As provas foram categorizadas, definidas e compiladas num quadro que está incluída na diretriz e que pode ser consultada no sítio web da WCET®. A força das recomendações foi avaliada utilizando um sistema alfabético (A+, A, A-, etc.). Foi solicitado o feedback da comunidade global de ostomia, tendo 146 indivíduos e 45 organizações sido convidados a comentar as conclusões. Destes, 104 indivíduos e 22 organizações enviaram comentários, os quais foram utilizados para finalizar a diretriz.

Resumo das Diretrizes

Porque a WCET® é uma associação internacional com membros em mais de 65 países, existe uma forte ênfase na diversidade da cultura, religião e nível de recursos, de modo a que o IOG 2020 possa ser aplicado tanto em países com abundância de recursos, como em países com escassez de recursos. O avanço foi escrito pelo Dr Larry Purnell, autor do Modelo Purnell para a Competência Cultural (inconscientemente incompetente, conscientemente incompetente, conscientemente competente, inconscientemente competente).3-5 De igual forma como na diretriz de 2014, os membros da WCET® e os Delegados Internacionais foram convidados a apresentar relatórios culturais do seu país, tendo 22 sido recebidos e incorporados no desenvolvimento da diretriz.

Uma vez que o IOG 2020 se destina a servir de guia para os clínicos na prestação de cuidados a pessoas com ostomia, nesta edição é novidade a secção sobre a implementação de linhas de orientação. Também é nova uma recomendação para a educação em enfermagem. Um glossário de termos e de recursos educativos úteis está também incluído nos vários apêndices. As 15 recomendações do IOG 2020 estão descritas no Quadro 1. As recomendações foram traduzidas para Chinês (Quadro Suplementar 1), Francês (Quadro Suplementar 2), Português (Quadro Suplementar 3), Espanhol (Quadro Suplementar 4) e estão também disponíveis no website da WCET® (www.wcetn.org).

Educação

As provas apoiam quatro recomendações do IOG 2020 sobre educação (Quadro 1). Uma pessoa que tenha uma cirurgia que resulte na criação de uma ostomia necessita de conhecimentos sobre o seu tipo de estoma, estratégias de cuidados tais como bolsas de ostomia, assim como saber qual o impacto que a ostomia terá no seu estilo de vida.6 Consequentemente, as necessidades destes pacientes vão para além do que pode ser ensinado nos programas de educação inicial de enfermagem. Zimnicki e Pieper7 efetuaram uma pesquisa em estudantes de enfermagem e identificaram que pouco menos de metade (47,8%) não tinha experiência em cuidar de um paciente com uma ostomia. Para aqueles que o fizeram, sentiam-se mais confiantes no esvaziamento da bolsa.7 Evidências detetadas por Cross e colegas8 também apoiam que os enfermeiros sem formação especializada em ostomia se sentiram mais confiantes em esvaziar a bolsa de ostomia do que em relação a outras competências de cuidados de ostomia. Duruk e Uçar9 na Turquia e Li e colegas10 na China também revelam que as equipas de enfermeiros carecem de conhecimentos adequados sobre o tratamento de pacientes com ostomias. Foram relatados melhores resultados nos cuidados de ostomia quando os pacientes são tratados por enfermeiros que tiveram formação especializada em ostomia. Isto inclui pesquisas realizadas em Espanha por Coca e colegas,11 no Japão por Chikubu e Oike,12 e no Reino Unido por Jones.13

Durante mais de 40 anos, a WCET® tem promovido a importância da educação especializada em ostomia para os enfermeiros, a fim de melhor satisfazer as necessidades dos pacientes e das suas famílias.6 Outras sociedades como a Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society nos EUA; Enfermeiros Especializados em Feridas, Ostomia e Continência Canadá; e a Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK têm também defendido a educação especializada em enfermagem. As modificações sugeridas incluem currículos baseados em competências e listas de verificação de capacidades e de desempenho profissional necessários para que o enfermeiro especializado preste os cuidados adequados aos pacientes com uma ostomia e às suas famílias.14-17 A prática baseada em evidências exige que os profissionais de saúde se mantenham a par das novas técnicas, competências e conhecimentos; é necessária a aprendizagem ao longo da vida.

Aspectos Holísticos Dos Cuidados: Cultura E Religião

A literatura suporta três recomendações de classificação muito elevada relacionadas com cuidados holísticos dentro do IOG 2020 (Quadro 1) e confirma a necessidade de as ter em conta ao cuidar de indivíduos com uma ostomia.

As ostomias podem ter impacto nos indivíduos em diferentes domínios, tais como a vida quotidiana, qualidade de vida global, relações sociais, trabalho, intimidade e autoestima. Uma abordagem holística dos cuidados visa reconhecer e identificar as necessidades do paciente a nível fisiológico, psicológico, sociológico, espiritual e cultural,18 especialmente quando a situação do paciente é complexa.19 Por conseguinte, a implementação de uma aproximação holística da prática é crucial para abordar todas as questões potenciais.20

Existem muitos instrumentos para avaliar a qualidade de vida dos pacientes, tais como o ajustamento dos cuidados pessoais, a adaptação social e/ou o estado psicológico.21,22 Fornecem informação importante aos enfermeiros na sua tomada de decisões clínicas, embora, como sempre, o juízo clínico continue a ser relevante. Uma vez que o cuidado holístico é multidimensional, a utilização de vários métodos permitirá uma abordagem integradora e global no cuidado de pacientes com ostomias.

A definição de saúde efetuada pela Organização Mundial de Saúde23 é ainda hoje relevante. As origens, crenças, religião, cultura, sexo e idade de um indivíduo influenciarão a sua interpretação da doença e das enfermidades.24-26 Para os profissionais de saúde, a necessidade de compreender estas influências e os seus impactos reais no paciente, família, e/ou prestador(es) de cuidados é essencial porque fornecerá informação chave para co-construir os cuidados de ostomia.

O Modelo de Competência Cultural do Dr. Larry Purnell3,4 pode ser prontamente aplicado aos cuidados de ostomia.5 Pode ajudar os enfermeiros a prestar cuidados culturalmente competentes aos pacientes com ostomia. A integração de competências culturais eficazes melhorará as relações entre pacientes, famílias e profissionais de saúde,27 especialmente se os doentes e/ou famílias tiverem dificuldades em lidar com a situação.28

Os enfermeiros especializados e não especializados têm um papel fundamental na educação do paciente, da família e dos prestadores de cuidados.29 Ajudarão, passo a passo, no apoio ao desenvolvimento de competências específicas e na implementação de estratégias adaptativas personalizadas. Os conselhos e o apoio dos enfermeiros podem diminuir as complicações relacionadas com a ostomia,13,30,31 e ouvir e atender as emoções dos pacientes melhorará o autocuidado dos indivíduos.32

Ter em conta a Carta Internacional dos Direitos do Ostomizado33 durante a prestação de cuidados de ostomia irá aumentar a qualidade de vida dos pacientes, porque apoia o empoderamento dos mesmos e reforça as parcerias entre pacientes, famílias, prestadores de cuidados e profissionais de saúde.

A secção 6 do IOG 2020 fornece uma perspetiva internacional sobre os cuidados em ostomia. Com contribuições provenientes de 22 países, esta versão é mais inclusiva do que a anterior.2 É a esperança dos autores de que ajudará os clínicos de ostomia em todo o mundo quando cuidarem de pacientes de outra cultura, origem ou sistema de crenças e, por conseguinte, dar-lhes-á melhores competências para responderem às necessidades de cada indivíduo.

Cuidados Pré-Operatórios e Marcação da Localização do Estoma

Como se vê no Quadro 1, há quatro recomendações que abordam os cuidados pré-operatórios e a marcação da localização do estoma. A literatura enfatiza a educação pré-operatória dos pacientes que estão prestes a ser submetidos a uma cirurgia de ostomia, o qual inclui a marcação do local pré-operatório. Menos complicações são observadas em pessoas que têm os seus locais de estoma marcados antes da cirurgia.34,35

Uma vez que os enfermeiros especializados podem não estar disponíveis 24 horas/dia e 7 días/semana, os pacientes que se submetem a uma cirurgia não planeada/de emergência podem não beneficiar da educação pré-operatória e da marcação da localização do estoma. Consequentemente, a literatura apoia a formação de médicos e enfermeiros não especializados na realização da marcação da localização do estoma.34-37 Zimnicki36 completaram um projeto de melhoria de qualidade para formar enfermeiros não especializados na marcação da localização do estoma. Este projeto aumentou significativamente o número de pacientes que tiveram marcação da localização do estoma e educação pré-operatória.36

A marcação da localização do estoma é uma arte e uma habilidade importante e a sua descrição em pormenor está para além do âmbito deste artigo. Os princípios fundamentais incluem a observação do abdómen do paciente em pé, sentado, curvado e deitado (Figura 1).37-41 Existem pelo menos duas técnicas para identificar a localização ideal abdominal.42-52 Os interessados podem consultar as referências42-60, bem como o webinar ou a guia de bolso do WCET® para a marcação da localização do estoma (www.wcetn.org).52

Figura 1 posições para marcação da localização do estoma ©2021 Ayello, utilizado com autorização.

Cuidados Pós-Operatórios

O IOG 2020 enumera quatro recomendações de cuidados pós-operatórios para auxiliar os clínicos de ostomia a detetar, prevenir ou gerir, de modo a minimizar o efeito de quaisquer complicações peristomais (Quadro 1).

Quadro 1 Recomendações da WCET® Guia Internacional para a Ostomia 2020

O sucesso da recuperação pós-operatória após uma cirurgia de ostomia depende de múltiplos fatores, tanto da perspetiva do clínico de ostomia como da pessoa com uma ostomia. Todos os membros da equipa de cuidados, incluindo o paciente, devem ter uma maior consciência das estratégias preventivas ou corretivas de problemas comuns que podem ocorrer com a formação de um novo estoma, a remodelação de um estoma existente ou o encerramento de um estoma. A capacidade de reconhecer e gerir eficazmente a ostomia pós-operatória potencial ou real e as complicações cutâneas peristómicas (PSCs) tem ramificações inerentes a curto e longo prazo para a saúde, bem-estar e independência das pessoas com uma ostomia61-63 e para a gestão de recursos de saúde.64-66

As complicações da ostomia pós-operatória podem manifestar-se de uma forma precoce ou tardia. Complicações precoces tais como separação mucocutânea, retração, necrose estomacal, abcesso parastomal ou dermatite podem ocorrer no prazo de 30 dias após a cirurgia. As complicações posteriores incluem hérnias parastomais (PHs) e prolapso estomacal, retração ou estenose.63,67,68

No entanto, as complicações pós-operatórias mais comuns são os PSCs.69 As causas frequentemente citadas de PSCs são fugas,70,71 ausência de localização do estoma pré-operatória,35 técnicas de construção cirúrgica deficientes,72 aparelhos mal-adaptados e longo tempo de utilização dos aparelhos.71,73

As PSCs mais comuns incluem dermatite de contacto irritante aguda e crónica e dermatite de contacto alérgica, a primeira resultante de contacto prolongado com fezes ou urina na pele, eventualmente causando erosão (Figura 2). A avaliação do abdómen, estoma, aparelho de estoma e acessórios em utilização, assim como a capacidade do paciente em cuidar do estoma e reaplicar corretamente o seu aparelho é essencial para determinar a causa de fugas. Os cuidados com a pele, dependendo da gravidade da irritação ou erosão, podem envolver a utilização de pós ou pastas protetoras à base de pectina, vedantes cutâneos (copolímeros acrilatos ou cianoacrilatos, toalhetes ou sprays) e barreiras cutâneas protetoras. Podem também ser necessários ajustes ao tipo de aparelho utilizado e ao tempo da sua utilização para melhorar situações agudas e prevenir dermatites crónicas de contacto irritantes.61,70,74

Figura 2 dermatite irritante ©2021 Chabal, utilizado com autorização.

A dermatite de contacto alérgica resulta de uma reação adversa a substâncias contidas em produtos aplicados na pele durante a limpeza ou proteção da pele, utilizados antes da aplicação ou remoção do aparelho ou que fazem parte do próprio aparelho.74,75 A pele comprometida reflete geralmente a forma do aparelho se a origem for o alergénio ou a área onde foram utilizados produtos secundários para o cuidado da pele. A pele afetada pode ter o especto de uma erupção cutânea; ser avermelhada, com bolhas, originar comichão, ou ser dolorosa; ou exsudar fluido hemosseroso (Figura 3). Pode ser necessário testar pequenas áreas de pele bastante afastadas da pele comprometida e do estoma para que seja possível identificar agentes causadores específicos e/ou avaliar a adequação de outros produtos de barreira cutânea utilizados para obter um selo seguro em torno do estoma.70,75

Figura 3 dermatite de contacto alérgica ©2021 Chabal, utilizado com autorização.

As hérnias parastomais são uma complicação latente que também contribui para as PSCs. As causas incluem a técnica cirúrgica, o tamanho e o tipo de estoma, a circunferência abdominal, a idade e as condições médicas, tais como hérnias anteriores e a existência de fluido de diverticulite. A educação dos cirurgiões e a inserção profilática de uma malha de polipropileno durante a cirurgia, bem como a educação dos pacientes no pós-operatório, podem diminuir a incidência de PH (Figura 4).68,76,77 Além disso, os prestadores devem avaliar e medir o abdómen do paciente ao nível do estoma para escolher a peça de vestuário de apoio mais apropriada necessária para gerir o grau de protrusão de PH, evitar exacerbações adicionais e permitir que o estoma continue a funcionar normalmente.78 O aparelho/bolsa de ostomia em uso terá também de ser frequentemente reavaliado para se resolverem quaisquer alterações no tamanho do estoma.

Figura 4 hérnia parastomal ©2021 Chabal, utilizada com autorização.

O IOG 2020 cita numerosas ferramentas que os clínicos de ostomia podem utilizar para identificar e classificar eficazmente os PSCs 79,80,81 e selecionar barreiras cutâneas e aparelhos apropriados para gerir os PSCs.62,82

Por fim, de importância crescente para melhorar a qualidade de vida pós-operatória de indivíduos com ostomia, reduzir as complicações da ostomia e readmissões associadas e melhorar a prática interprofissional, está a utilização de programas de recuperação precoce ou melhorados após a cirurgia,83,84 programas de educação contínua e programas de monitorização de altas,68,85 e modalidades de tele-saúde para aconselhamento e consulta à distância.86,87

Implementação das Diretrizes de Orientação

Para que as diretrizes clínicas resultem em resultados positivos para as populações de pacientes identificadas, as recomendações propostas têm de ser adotadas na prática diária. São necessárias estratégias múltiplas para facilitar a adoção,88,89 e as diretrizes devem ser revistas e adaptadas a contextos clínicos específicos.90 É, portanto, necessária uma reflexão prévia sobre a forma como as diretrizes serão divulgadas e implementadas. As potenciais barreiras à implementação de diretrizes podem incluir a falta de recursos, objetivos de saúde distintos, ou uma perceção de falta de interesse nos cuidados de ostomia como uma subespecialidade médica/de enfermagem sem um "campeão" para defender e facilitar a sua implementação. Por último, as diretrizes podem ser entendidas como demasiado prescritivas. A secção sobre a implementação de diretrizes no âmbito do IOG 2020 fornece conselhos e os leitores são encaminhados para a diretriz completa para mais informações.

Impacto da Covid-19 nos Cuidados de Ostomia

A revisão das provas para o IOG 2020 antecedeu o advento do novo coronavírus de 2019. Durante a pandemia, houve relatos anedóticos de clínicos de ostomia a serem realocados para cuidar de outros pacientes. A extensão e o impacto destas práticas ainda têm de ser investigadas. Entretanto, as consultas virtuais podem constituir uma alternativa segura aos cuidados presenciais para pacientes e prestadores de cuidados.91 Um estudo de White e colegas92 relatou a viabilidade das consultas virtuais para pessoas com novas ostomias; 90% dos pacientes sentiram que estas consultas eram úteis na gestão da sua ostomia.92 No entanto, outro estudo concluiu que apenas 32% dos inquiridos sabiam que a tele-saúde era uma opção.93 Além disso, 71% "não acharam [a sua questão] suficientemente importante para procurar assistência de um profissional de saúde"93, embora 57% tenham relatado alguma ocorrência de pele peristomal durante a pandemia.93 Por ordem decrescente, os tipos de problemas de pele comunicados foram vermelhidão ou erupção cutânea (79%), prurido (38%), pele aberta (21%), hemorragia (19%) e outras preocupações (7%).93

Conclusões

O IOG 2020 visa fornecer aos clínicos um quadro de evidências sobre o qual basear a sua prática. As 15 recomendações do IOG 2020 são aplicáveis em países onde os recursos são abundantes (enfermeiros e profissionais de saúde formados em cuidados de ostomia utilizando aparelhos/bolsas fabricados), bem como em países com recursos limitados (enfermeiros não especializados, profissionais de saúde e leigos que criam equipamento de ostomia a partir de recursos locais disponíveis para conter o efluente da ostomia). São necessários conhecimentos especializados para ajudar as pessoas com uma ostomia a aprender como aplicar, esvaziar e mudar o seu aparelho/bolsa, mas viver com uma ostomia é muito mais do que isso. Todos os aspetos do paciente precisam de ser considerados.

Os cuidados holísticos do paciente devem ser individualizados e abordar a alimentação, atividades da vida diária, vida sexual, oração, trabalho, medicamentos, imagem corporal e outras preocupações centradas no paciente. A localização do estoma pré-operatório tem estado ligada a melhores resultados pós-operatórios. A identificação precoce e a intervenção nos PSCs requer um ensino adequado, bem como o conhecimento de quando procurar ajuda profissional. Os enfermeiros que possuem conhecimentos especializados em cuidados de ostomia podem melhorar a qualidade de vida de pessoas com uma ostomia, incluindo as que experimentam PSCs.95 É a esperança dos autores que o IOG 2020 melhore os resultados dos cuidados e a reabilitação desta população.

Lições Práticas

- Os pacientes que são tratados por profissionais de saúde com conhecimentos especializados em ostomia experimentam melhores resultados em termos de cuidados de saúde.

- Existem ferramentas clínicas para auxiliar na avaliação peristomal da pele e dos requisitos dos aparelhos.

- A educação pré e pós-operatória do paciente e da família precisa de ser holística e individualizada.

- Os pacientes que se submetem à localização do estoma pré-cirúrgico experimentam menos complicações.

- O PSC mais comum é a fuga que conduz ao surgimento de dermatite irritante.

- A tele-saúde e a consulta remota podem ser vantajosas para fornecer orientação complementar às pessoas com ostomias.

Author(s)

Laurent O. Chabal*

BSc (CBP), RN, OncPall (Cert), Dip (WH), ET, EAWT

Specialised Stoma Nurse, Ensemble Hospitalier de la Côte—Morges’ Hospital; Lecturer, Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Western Switzerland; and President Elect, WCET® 2020-2022

Jennifer L. Prentice

PhD, RN, STN, FAWMA

WCET® Journal Editor; Nurse Specialist Wound Skin Ostomy Service Hall & Prior Health and Aged Care Group, Perth, Western Australia

Elizabeth A. Ayello

PhD, MS, BSN, ETN, RN, CWON, MAPCWA, FAAN

Co-Editor in Chief, Advances in Skin and Wound Care;

President, Ayello, Harris & Associates, Copake, New York;

WCET® President, 2018-2022; WCET® Executive Journal Editor Emerita, Perth, Western Australia; and Faculty Emerita, Excelsior College School of Nursing, Albany, New York

* Corresponding author

References

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® International Ostomy Guideline. Chabal LO, Prentice JL, Ayello EA, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET®; 2020.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® International Ostomy Guideline. Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Stelton S, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET®; 2014.

- Purnell L. Transcultural health care: a culturally competent approach. Philadelphia: F A Davis Co; 2013.

- Purnell L. Guide to culturally competent health care. Philadelphia: F A Davis Co; 2014.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model applied to ostomy and wound care. WCET J 2014;34(3):11-8.

- Gill-Thompson SJ. Forward to second edition. In: Erwin-Toth P, Krasner DL, eds. Enterostomal Therapy Nursing. Growth & Evolution of a Nursing Specialty Worldwide. A Festschrift for Norma N. Gill-Thompson ET. 2nd ed. Perth, Western Australia: Cambridge Publishing; 2020;10-1.

- Zimnicki K, Pieper B. Assessment of prelicensure undergraduate baccalaureate nursing students: ostomy knowledge, skill experiences, and confidence in care. Ostomy Wound Manage 2018;64(8):35-42.

- Cross HH, Roe CA, Wang D. Staff nurse confidence in their skills and knowledge and barriers to caring for patients with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(6):560-5.

- Duruk N, Uçar H. Staff nurses’ knowledge and perceived responsibilities for delivering care to patients with intestinal ostomies. A cross-sectional study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(6):618-22.

- Li, Deng B, Xu L, Song X, Li X. Practice and training needs of staff nurses caring for patients with intestinal ostomies in primary and secondary hospital in China. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(5):408-12.

- Coca C, Fernández de Larrinoa I, Serrano R, García-Llana H. The impact of specialty practice nursing care on health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):257-63.

- Chikubu M, Oike M. Wound, ostomy and continence nurses competency model: a qualitative study in Japan. J Nurs Healthc 2017;2(1):1-7.

- Jones S. Value of the Nurse Led Stoma Care Clinic. Cwm Taf Health Board, NHS Wales. 2015. www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/research-and-innovation/innovation-in-nursing/~/-/media/b6cd4703028a40809fa99e5a80b2fba6.ashx. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. ETNEP/REP Recognition Process Guideline. 2017. https://wocet.memberclicks.net/assets/Education/ETNEP-REP/ETNEP%20REP%20Guidelines%20Dec%202017.pdf. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. WCET Checklist for Stoma REP Content. 2020. www.wcetn.org/assets/Education/wcet-rep%20stoma%20care%20checklist-feb%2008.pdf. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN Society clinical guideline: management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy-an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(1):50-8.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Task Force. Wound, ostomy, and continence nursing: scope and standards of WOC practice, 2nd edition: an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(4):369-87.

- Wallace S. The Importance of holistic assessment—a nursing student perspective. Nuritinga 2013;12:24-30.

- Perez C. The importance of a holistic approach to stoma care: a case review. WCET J 2019;39(1):23-32.

- The importance of holistic nursing care: how to completely care for your patients. Practical Nursing. October 2020. www.practicalnursing.org/importance-holistic-nursing-care-how-completely-care-patients. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Knowles SR, Tribbick D, Connell WR, Castle D, Salzberg M, Kamm MA. Exploration of health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in individuals with fecal ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):69-73.

- Vural F, Harputlu D, Karayurt O, et al. The impact of an ostomy on the sexual lives of persons with stomas—a phenomenological study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):381–4.

- World Health Organization. What is the WHO definition of health? www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, et al. Gender differences in sleep disruption and fatigue on quality of life among persons with ostomies. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(4):335-43.

- World Health Organization. Gender, equity and human rights. 2020. www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/indigenous-peoples/en. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Forest-Lalande L. Best-practice for stoma care in children and teenagers. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2019;17(S5):S12-3.

- Qader SAA, King ML. Transcultural adaptation of best practice guidelines for ostomy care: pointers and pitfalls. Middle East J Nurs 2015;9(2):3-12.

- Iqbal F, Kujan O, Bowley DM, Keighley MRB, Vaizey CJ. Quality of life after ostomy surgery in Muslim patients—a systematic review of the literature and suggestions for clinical practice. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):385-91.

- Merandy K. Factors related to adaptation to cystectomy with urinary diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(5):499-508.

- de Gouveia Santos VLC, da Silva Augusto F, Gomboski G. Health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies managed in an outpatient care setting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(2):158-64.

- Ercolano E, Grant M, McCorkle R, et al. Applying the chronic care model to support ostomy self-management: implications for oncology nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20(3):269-74.

- Xu FF, Yu Wh, Yu M, Wang SQ, Zhou GH. The correlation between stigma and adjustment in patients with a permanent colostomy in the midlands of China. WCET J 2019;39(1):24-39.

- International Ostomy Association. Charter of Ostomates Rights. www.ostomyinternational.org/about-us/charter.html. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Watson AJM, Nicol L, Donaldson S, Fraser C, Silversides A. Complications of stomas: their aetiology and management. Br J Community Nurs 2013;18(3):111-2, 114, 116.

- Baykara ZG, Demir SG, Ayise Karadag A, et al. A multicenter, retrospective study to evaluate the effect of preoperative stoma site marking on stomal and peristomal complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2014;60(5):16-26.

- Zimnicki KM. Preoperative teaching and stoma marking in an inpatient population: a quality improvement process using a FOCUS-Plan-Do-Check-Act Model. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(2):165-9.

- WOCN Committee Members, ASCRS Committee Members. ASCRS and WOCN joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing fecal ostomy surgery. JWOCN 2007;34(6):627-8.

- Salvadalena G, Hendren S, McKenna L, et al. WOCN Society and ASCRS position statement on preoperative stoma site marking for patients undergoing colostomy or ileostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):249-52.

- Salvadalena G, Hendren S, McKenna L, et al. WOCN Society and AUA position statement on preoperative stoma site marking for patients undergoing urostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):253-6.

- Brooke J, El-GHaname A, Napier K, Sommerey L. Executive summary: Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada (NSWOCC) nursing best practice recommendations. Enterocutaneous fistula and enteroatmospheric fistula. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(4):306-8.

- Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada. Nursing Best Practice Recommendations: Enterocutaneous Fistulas (ECF) and Enteroatmospheric Fistulas (EAF). 2nd ed. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada; 2018.

- Serrano JLC, Manzanares EG, Rodriguez SL, et al. Nursing intervention: stoma marking. WCET J 2016;36(1):17-24.

- Fingren J, Lindholm E, Petersén C, Hallén AM, Carlsson E. A prospective, explorative study to assess adjustment 1 year after ostomy surgery among Swedish patients. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;64(6):12-22.

- Rust J. Complications arising from poor stoma siting. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2011;9(5):17-22.

- Watson JDB, Aden JK, Engel JE, Rasmussen TE, Glasgow SC. Risk factors for colostomy in military colorectal trauma: a review of 867 patients. Surgery 2014;155(6):1052-61.

- Banks N, Razor B. Preoperative stoma site assessment and marking. Am J Nurs 2003;103(3):64A-64C, 64E.

- Kozell, K, Frecea M, Thomas JT. Preoperative ostomy education and stoma site marking. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(3):206-7.

- Readding LA. Stoma siting: what the community nurse needs to know. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(11):502-11.

- Cronin E. Stoma siting: why and how to mark the abdomen in preparation for surgery. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2014;12(3):12-9.

- Chandler P, Carpenter J. Motivational interviewing: examining its role when siting patients for stoma surgery. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2015;13(9):25-30.

- Pengelly S, Reader J, Jones A, Roper K, Douie WJ, Lambert AW. Methods for siting emergency stomas in the absence of a stoma therapist. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014;96:216-8.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. Guide to Stoma Site Marking. Crawshaw A, Ayello EA, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET; 2018.

- Mahjoubi B, Goodarzi K, Mohannad-Sadeghi H. Quality of life in stoma patients: appropriate and inappropriate stoma sites. World J Surg 2009;34:147-52.

- Person B, Ifargan R, Lachter J, Duek SD, Kluger Y, Assalia A. The impact of preoperative stoma site marking on the incidence of complications, quality of life, and patient’s independence. Dis Colon Rect 2012;55(7):783-7.

- American Society of Colorectal Surgeons Committee, Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses Society® Committee. ASCRS and WOCN® joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing fecal ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34(6):627-8.

- AUA and WOCN® Society joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing creation of an incontinent urostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(3):267-8.

- Cronin E. What the patient needs to know before stoma siting: an overview. Br J Nurs 2012;21(22):1304, 1306-8.

- Millan M, Tegido M, Biondo S, Garcia-Granero E. Preoperative stoma siting and education by stomatherapists of colorectal cancer patients: a descriptive study in twelve Spanish colorectal surgical units. Colorectal Dis 2010;12(7 Online):e88-92.

- Batalla MGA. Patient factors, preoperative nursing Interventions, and quality of life of a new Filipino ostomates. WCET J 2016;36(3):30-8.

- Danielsen AK, Burcharth J, Rosenberg J. Patient education has a positive effect in patients with a stoma: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2013;15(6):e276-83.

- Stelton S, Zulkowski K, Ayello EA. Practice implications for peristomal skin assessment and care from the 2014 World Council of Enterostomal Therapists International Ostomy Guideline. Adv Skin Wound Care 2015;28(6):275-84.

- Colwell JC, Bain KA, Hansen AS, Droste W, Vendelbo G, James-Reid S. International consensus results. Development of practice guidelines for assessment of peristomal body and stoma profiles, patient engagement, and patient follow-up. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(6):497-504.

- Maydick-Youngberg D. A descriptive study to explore the effect of peristomal skin complications on quality of life of adults with a permanent ostomy. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(5):10-23.

- Nichols TR, Inglese GW. The burden of peristomal skin complications on an ostomy population as assessed by health utility and their physical component: summary of the SF-36v2®. Value Health 2018;21(1):89-94.

- Neil N, Inglese G, Manson A, Townshend A. A cost-utility model of care for peristomal skin complications. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;34(1):62.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Eaves D, Oster G. Risk and economic burden of peristomal skin complications following ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(2):143-9.

- Koc U, Karaman K, Gomceli I, et al. A retrospective analysis of factors affecting early stoma complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(1):28-32.

- Hendren S, Hammond K, Glasgow SC, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for ostomy surgery. J Dis Colon Rectum 2015;58:375-87.

- Roveron G. An analysis of the condition of the peristomal skin and quality of life in ostomates before and after using ostomy pouches with manuka honey. WCET J 2017;37(4):22-5.

- Stelton S. Stoma and peristomal skin care: a clinical review. Am J Nurs 2019;119(6):38-45.

- Recalla S, English K, Nazarali R, Mayo S, Miller D, Gray M. Ostomy care and management a systematic review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(5):489-500.

- Carlsson E, Fingren J, Hallen A-M, Petersen C, Lindholm E. The prevalence of ostomy-related complications 1 year after ostomy surgery: a prospective, descriptive, clinical study. Ostomy Wound Manage 2016;62(10):34-48.

- Steinhagen E, Colwell J, Cannon LM. Intestinal stomas—postoperative stoma care and peristomal skin complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017;30(3):184-92.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. WCET Ostomy Pocket Guide: Stoma and Peristomal Problem Solving. Ayello EA, Stelton S, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET, 2016.

- Cressey BD, Belum VR, Scheinman P, et al. Stoma care products represent a common and previously underreported source of peristomal contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2017;76(1):27-33.

- Tabar F, Babazadeh S, Fasangari Z, Purnell P. Management of severely damaged peristomal skin due to MARSI. WCET J 2017;37(1):18.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Lamerato L, Oster G. Clinical and economic burden of peristomal skin complications in patients with recent ostomies. J Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(4):350.

- Association Stoma Care Nurses. ASCN Stoma Care National Clinical Guidelines. London, England: ASCN UK; 2016.

- Herlufsen P, Olsen AG, Carlsen B, et al. Study of peristomal skin disorders in patients with permanent stomas. Br J Nurs 2006;15(16):854-62.

- Ay A, Bulut H. Assessing the validity and reliability of the peristomal skin lesion assessment instrument adapted for use in Turkey. Ostomy Wound Manage 2015;61(8):26-34.

- Runkel N, Droste W, Reith B, et al. LSD score. A new classification system for peristomal skin lesions. Chirurg 2016;87:144-50.

- Buckle N. The dilemma of choice: introduction to a stoma assessment tool. GastroIntestinal Nurs 2013;11(4):26-32.

- Miller D, Pearsall E, Johnston D, et al. Executive summary: enhanced recovery after surgery best practice guideline for care of patients with a fecal diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):74-7.

- Hardiman KM, Reames CD, McLeod MC, Regenbogen SE. A patient-autonomy-centered self-care checklist reduces hospital readmissions after ileostomy creation. Surgery 2016;160(5):1302-8.

- Harputlu D, Özsoy SA. A prospective, experimental study to assess the effectiveness of home care nursing on the healing of peristomal skin complications and quality of life. Ostomy Wound Manage 2018;64(10):18-30.

- Iraqi Parchami M, Ahmadi Z. Effect of telephone counseling (telenursing) on the quality of life of patients with colostomy. JCCNC 2016;2(2):123-30.

- Xiaorong H. Mobile internet application to enhance accessibility of enterostomal therapists in China: a platform for home care. WCET J 2016;36(2):35-8.

- Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM. Selecting, presenting, and delivering clinical guidelines: are there any “magic bullets”. Med J Aust 2004;180(6 Suppl):S52-4.

- Rauh S, Arnold D, Braga S, et al. Challenge of implementing clinical practice guidelines. Getting ESMO’s guidelines even closer to the bedside: introducing the ESMO Practising Oncologists’ checklists and knowledge and practice questions. ESMO Open 2018;3:e000385.

- Fletcher J, Kopp P. Relating guidelines and evidence to practice. Prof Nurse 2001;16:1055-9.

- Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa P, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. JAMIA 2020;27(7):1132-5.

- White T, Watts P, Morris M, Moss J. Virtual postoperative visits for new ostomates. CIN 2019;37(2):73-9.

- Spencer K, Haddad S, Malanddrino R. COVID-19: impact on ostomy and continence care. WCET J 2020;40(4):18-22.

- Russell S. Parastomal hernia: improving quality of life, restoring confidence and reducing fear. The importance of the role of the stoma nurse specialist. WCET J 2020;40(4):36-9.