Volume 24 Number 1

The challenges of managing patients with pyoderma gangrenosum: three case reports

Donna Evealyne Angel and Johanna Lee van Rooyen

Keywords Pyoderma gangrenosum; ulcers; venous disease.

Abstract

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), although first described nearly 100 years ago, remains challenging for clinicians. The aetiology of PG remains a mystery. There are no specific guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PG. Other ulcerating wounds can mimic PG, leading to misdiagnosis, which can have detrimental effects for the patient. The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of the challenges faced by the clinician in diagnosing and managing patients with PG. Three case studies demonstrate the complexity of diagnosing and treating patients with PG.

Overview

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is an atypical neutrophilic dermatosis that appears as an inflammatory and ulcerative condition of the skin1. First described by Brocq in 1916, as phagedenisme geometrique, a rare neutrophilic dermatosis2. Brunstig, Goeckerman and O’Leary in 1930 named it pyoderma gangrenosum. This was based on a series of five case reports of patients with ulceration of the skin3. Initially they believed that the condition was related to streptococcal infection, leading to cutaneous gangrene. Four of the patients had chronic ulcerative colitis, hence the initial association with inflammatory bowel disease. Brunstig et al. describe the ulcers as enlarging, painful, necrotic with bluish edges and circumferential erythema. Contrary to its name, it is neither infectious or a gangrenous disorder. Although first described almost 100 years ago, the aetiology remains a mystery4.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology data for the condition is based predominantly on case reports, case series and cohort studies, mostly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease2,5-10. A rare condition, the incidence is estimated at three to 10 cases per million per year2,4. Based on a large population-based cohort study the incidence in the UK is estimated at six per million per year8. PG generally affects people between the ages of 20 and 50 years4; it has also been reported in approximately 4% of children1,2,11-13. Data regarding gender is contradictory. According to some there is a higher incidence in females2,4,8,9,14, although others have reported no gender preference2,5.

Pathogenesis

PG is classified as a neutrophilic dermatoses, with neutrophil predominant infiltrates of the skin, without evidence of primary vasculitis15. The physiological process that leads to PG remains ambiguous. Early hypotheses included occult bacterial infection, circulating antibodies, or the Shwartzman reaction (an immune response to bacterial endotoxins leading to tissue necrosis). However, there is a lack of evidence to support these theories1. Current postulations regarding the pathogenesis of PG include neutrophil dysfunction, genetic factors and dysregulation of the innate immune system.

In pathology specimens there is the presence of neutrophilic infiltrates; this combined with the clinical response to anti-neutrophil agents, such as colchicine and dapsone, which disrupts chemotaxis and phagocytosis, suggests that neutrophilic dysfunction plays a role in the pathophysiology of PG16,17. One study suggests that there are abnormalities in neutrophil trafficking and signalling, related to intracellular metabolic oscillations in patients with PG18.

Genetic features that have been reported include familial cases of PG and also PG related to pyogenic sterile arthritis syndrome (PAPA) and acne19-24. There is also a growing body of evidence to suggest that dysregulation of the innate immune system is associated with PG25,26. This builds on the evidence of neutrophil dysfunction.

Clinical Presentation

The lesions commonly occur on the lower legs, classically the pre-tibial region, but can occur on any anatomical location including: trunk, head, neck, breasts, upper limbs, genitalia, mucous membranes and peristomal distribution1,2,27-29. Lesions have been reported to occur concurrently on different anatomical locations2. Characteristically, the lesions begin as a small nodule or sterile pustule30 which enlarge into well-demarcated ulcers, which can extend to the fascia with violaceous margins (red-blue) undermined border, surrounding erythema and induration. Typically the lesions have necrosis at the base, friable granulation tissue with a purulent or haemoserous exudate2. The ulcers are often described as “necrolytic”, a process whereby as the tissue is destroyed, the liquefactive necrosis reveals a red-blue undermined wound edge30. Invariably the lesions are extremely painful. Atrophic cribriform pigmented scarring can occur as the lesions heal, particularly with delayed diagnosis and treatment2,4. PG has also been described in association with pathergy, a process that occurs as a result of trauma. This has been reported in wounds ranging from minor trauma to surgical incision sites10,31. In surgical wounds, PG has been erroneously diagnosed as infection leading to wound debridement, which has triggered pathergy, resulting in aggravation of the disease and on occasion leading to amputation32,33. In a retrospective review of 103 patients, pathergy was documented in 31% of patients14.

Clinical Variants

According to Powell et al. there are four clinical subtypes: ulcerative or ‘classic’; bullous (atypical); pustular; and vegetative, all sharing similar characteristics6. Peristomal PG, genital PG, extracutaneous PG and infantile PG have also been described in the literature1,2,4.

Ulcerative: Most common variant. Starts as a tender papule or vesicle that rapidly ulcerates, has a purulent base, with undermined, inflamed, violaceous borders. Painful lesions associated with systemic disease, requiring immunosuppressive treatment6,29.

Bullous: Less common variant, associated in patients with haematological malignancy, an indicator of a poor prognosis. It is characterised by painful bullae, usually located on the upper limbs and face. The bullae may spread and progress to superficial lesions and ulcers. Systemic immunosuppression is required2,4,6.

Pustular: This variant of PG is most often associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and may occur during exacerbations of bowel inflammation. Small painful pustules, with surrounding erythema, that usually improve with the treatment of IBD4,6.

Vegetative: Also known as superficial granulomatous pyoderma, the least painful and aggressive of all the variants of PG. It is a superficial nodule, plague or ulcer that progresses slowly without undermined edges or a purulent wound bed. Responds well to less aggressive forms of treatment4,6.

Peristomal: Development of lesions in the peristomal area following formation of an ileostomy or colostomy in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. Possibly as a result of pathergy from the surgical procedure, leakage of faeces on to the skin, or irritation from adhesive stomal appliances2,4,28,34.

Genital: Lesions occurring on the vulva, penis or scrotum. Behçet’s disease should be excluded4.

Extracutaneous: Rare form of PG, sterile neutrophilic infiltrates occurring in sites such as the lungs, spleen, central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, intestine, liver, cornea, heart, and lymph nodes4.

Associated disorders (Table 129)

It has been estimated that approximately 40–50% cases of PG are associated with a systemic disease and the remainder are idiopathic2,4. PG is the most common skin disorder associated in patients with IBD (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) and has been reported in approximately 2–12% of patients with IBD35. Other common disorders include arthritis9, haematological malignancy14, PAPA syndrome2, hidradenitis suppurativa, and HIV1.

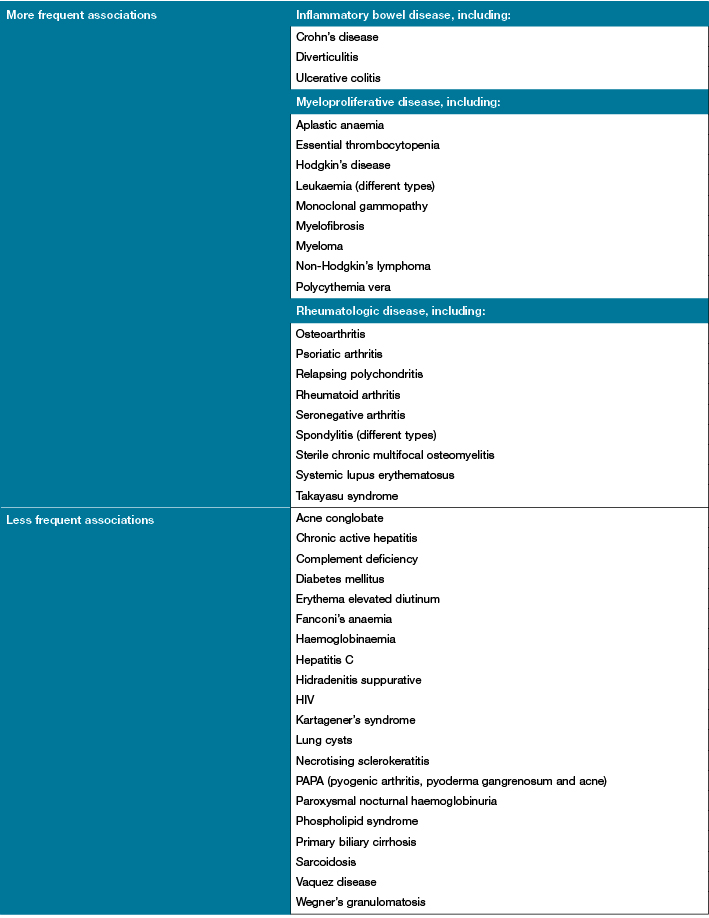

Table 1: Diseases associated with pyoderma gangrenosum29

Wollina U. Clinical management of pyoderma gangrenosum. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002;3(3):149–58.

Diagnosis

Histopathology and laboratory findings in PG are non-specific; therefore, the diagnosis is based on clinical history, physical examination and confirmed through a process of elimination. There should be a high index of suspicion in patients with non-healing ulcers, especially in the presence of systemic diseases2. The clinician must, however, err on the side of caution as many of the associated diseases may not be overtly obvious4. There are several differential diagnoses, and ulcerative cutaneous lesions that mimic PG (Table 21) including: malignancy, infectious disease, antiphospholipid antibody-associated occlusive disease, vasculitis, and drug reactions2,4.

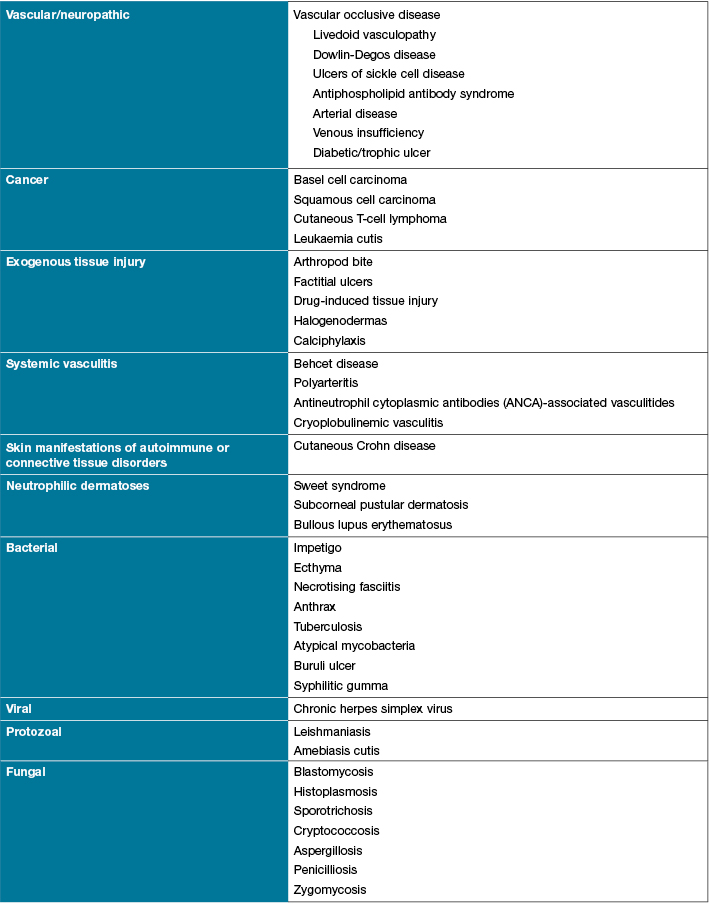

Table 2: Differential diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum1

Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2012;13(3):191–211.

Laboratory investigations are not diagnostic for PG; patients often have neutrophil leukocytosis30,36. The inflammatory process is reflected with elevated erythrocyte, C-reactive protein, and protein electrophoresis29. It is important to target laboratory investigations for associated diseases, such as IBD or arthritis, and to exclude other ulcerating conditions; for example, other autoimmune connective tissue diseases, or anticardiolipin syndrome29,30. Tissue biopsy for histopathology should be performed to exclude other conditions such as malignancy or vasculitis. A biopsy can also be performed for microbiology, culture and sensitivity (MC&S), particularly looking for atypical mycobacteria, fungi and parasites. Although performing a tissue biopsy can cause pathergy, the procedure should be performed, as this will assist in ruling out other aetiologies1,2,4.

The important factor to take into consideration is that PG mimics many other conditions, leading to misdiagnosis1,30,37. Delay in treatment can lead to extensive tissue loss, undue pain for the patient and potentially inappropriate therapies2. Early referral to a physician or dermatologist is recommended if PG is suspected30. Su et al. proposed a diagnostic criterion for classic ulcerative PG, to consider the essential features for diagnosing PG. Both of the major criteria must be met and two from the minor criteria30.

Major criteria

1. Rapid progression of a painful, necrolytic cutaneous ulcer with an irregular, violaceous, and undermined border

2. Other causes of cutaneous ulceration have been excluded

Minor criteria

1. History suggestive of pathergy or clinical finding of cribriform scarring

2. Systemic diseases associated with PG

3. Histopathologic findings (sterile neutrophilia, +/– mixed inflammation, +/– lymphocytic vasculitis)

4. Treatment response (rapid response to systemic steroid treatment)

Treatment

There is a paucity of guidelines for the treatment of PG. This is due to a lack of clinical controlled trials. The disease process in poorly understood and treatment is based predominately on clinical experience4. Approach to treatment should be multidisciplinary, including dermatology, rheumatology, wound care specialists, pain specialists and pathologists36. Treatment aim is to reduce the inflammation, minimise pain, promote wound healing, and control underlying disorders1,2,4. If the patient has any underlying systemic disease, control of this often results in the control of skin lesions2. As there are numerous approaches to treatment a comprehensive review is outside the scope of this article. The authors have provided a summary of treatment options. Response to treatment is considered one of the minor diagnostic criteria, as suggested by Su et al.

Wound care

At each presentation the lesions should have a comprehensive assessment of the wound bed and the wound border, paying attention in particular to the type of tissue at the wound bed, amount and type of exudate, evidence of violaceous wound margins and the level of pain the patient is experiencing. The wound(s) should be measured, including length, width, depth, and, if possible, clinical photography of the wound as this allows for accurate ongoing wound assessment38. The TIME principle should be used as a guide for selecting the appropriate wound dressing39,40. Dressing selection will depend on the wound assessment; however, the dressing should be non-adherent to the wound bed and removed easily to minimise pain and trauma. Dressings that adhere to the wound bed may increase pain on removal and trigger pathergy1. Although PG is not infectious, having an open wound may increase the risk of infection; therefore, the wound and peri-wound must be monitored for clinical signs of infection such as: erythema, warmth, increased pain, increased exudate, lymphangitis and malodour1. In the presence of infection appropriate treatment should be commenced, including antibiotics and topical antimicrobial dressings40.

Topical agents

For small lesions, such as superficial pustules or shallow ulcers, treatment can include local application of high-potency corticosteroid lotion, ointment, cream or intralesional injections1,21,29,38. Topical agents can also be used in conjunction with systemic therapy for patients with severe PG38. Topical corticosteroids are more effective in patients with peristomal PG. Local injections of triamcinolone are preferred for non-peristomal PG29. Tacrolimus (FK-506), cyclosporine solution and intralesional injection of cyclosporine have also been used on PG lesions1,29,38. However, there is the need for larger clinical studies to prove their efficacy in the management of PG38. These must be applied with caution due to the risk of systemic absorption38. Other topical agents described in the literature include: topical application of 5-Aminosalicyclic acid1, recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)41. There are also reports of the application of nicotine transdermal delivery on the ulcers and use of nicotine gum42,43.

Systemic treatment

Systemic therapy is required in patients with all but superficial lesions2. Topical agents also do not address systemic disease and as the disease progresses a combination of topical and systemic agents may be required (Table 34). Systemic treatments have many side effects and can dampen the patients’ immune response, leaving them more susceptible to infections. Systemic high-dose corticosteroids, such as prednisolone, are often used initially with a rapid response; however, there are well-documented adverse effects with long-term use1,38. Another first-line treatment is cyclosporine; however, side-effects include renal toxicity, myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity and increased risk of infection1,38. Patients with underlying IBD have gone into remission with the use of cyclosporine44. Other modes of immunosuppression include mycophenolate, mofetil, methotrexate and azathioprine. These agents are considered more effective as adjunct therapy1. Immune modulators such as thalidomide are an emergent treatment option. These suppress neutrophil chemotaxis and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)2. Thalidomide and methotrexate are considered more effective as adjunctive therapy38. In patients with less severe forms of PG sulphur drugs are considered a second choice. Dapsone alone or in combination with corticosteroids is a common treatment. Neutrophil function and the production of reactive oxygen species is inhibited with dapsone29. Patients must have normal levels of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenese for this line of therapy29,38. Other immune modulation agents include infliximab and interferon-α1,2,4,36.

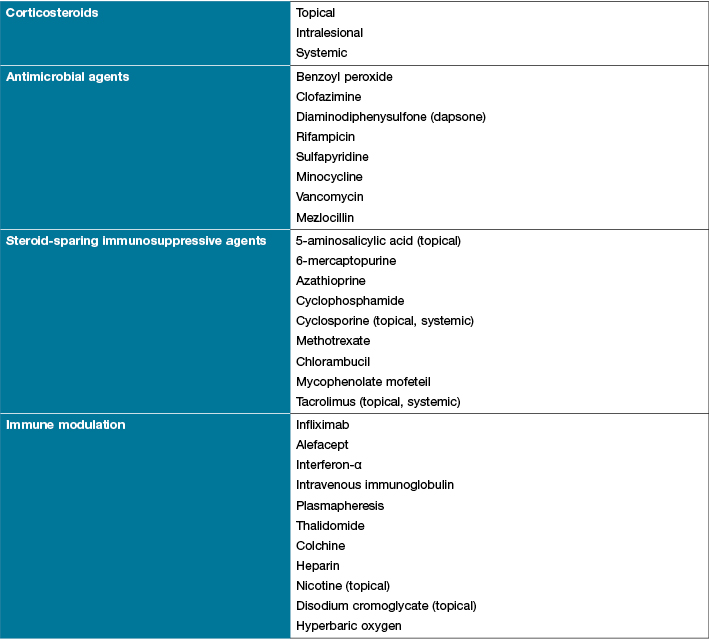

Table 3: Topical and systemic treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum4

Rucco E, Sangiuliano AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Dermatol Venerol 2009;23(9):1008–17.

Surgical intervention

Surgery is not generally recommended due to the risk of pathergy1,45; as a result the ulcers could potentially worsen following surgery1. However, there are a few reports in the literature of success following surgical intervention. There is one report of success with a free flap to cover a large lesion46, and the use of split-skin grafts and keratinocyte autografts47. Split-skin grafting has also been shown to reduce the patients’ pain45. There is also a case report of debridement, vacuum-assisted closure (VAC®) and hyperbaric oxygen therapy to promote wound healing48. According to Teagle and Hargest2, hyperbaric oxygen therapy can be helpful, even in recalcitrant cases. In general, surgery should be based on individual assessment of the patient and their wounds, weighing up the risk of pathergy.

Pain management

Pain associated with PG can be distressing for the patient. Patients report the pain as “stabbing” in nature. There are reports of severe pain leading to amputation of the affected limb38 The source of pain associated with PG is multifactorial and is attributed to the inflammatory process in the dermis and subsequent ulceration38. Pain levels should be monitored and as the ulcer improves pain levels should decrease. Although dressing changes are fundamental they may also be a source of pain; this must be considered when selecting a dressing and during dressing changes. Pain relief may be required and administered before dressing changes and during the procedure. Due to the chronicity of the wounds, narcotics should be avoided or limited to breakthrough pain38. A multidisciplinary approach may be required for pain management1

Case one

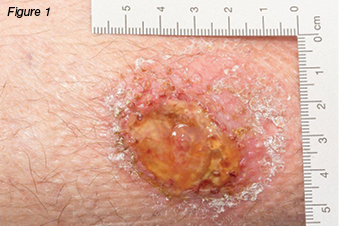

A 37-year-old female was referred to the wound clinic with a non-healing leg ulcer to the anterior aspect of her right lower leg, which was sustained four months earlier after knocking it on a wooden crate at work. Regular wound management was being performed by community nurses with a variety of dressings. On examination, the wound was 2.2 cm x 1.7 cm, had a sloughy base, and was extremely painful (Figures 1 and 2). Her only medical history was a right recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and a pulmonary embolus. A previous venous duplex scan revealed non-occlusive thrombus throughout much of the deep venous system of her right leg. Her only medication usage was warfarin. Ankle brachial indices were on the right: 0.9: left: 0.97. In view of her history of previous DVTs, a repeat venous duplex scan was ordered which revealed deep and superficial incompetence. Bacterial culture grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus sensitive to ciprofloxacin. Based on the venous duplex scan and patient’s history, the wound was diagnosed as a venous leg ulcer and was initially treated with an appropriate primary dressing and compression bandaging 30–40 mmHg. Despite this, the wound increased in size, developed a violaceous margin, and became extremely painful (Figure 3). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, where a tissue biopsy was performed. This demonstrated non-specific ulceration; cultures for atypical mycobacteria and fungus were negative. Based on the clinical picture the patient was diagnosed with PG and commenced on a reducing dose of prednisolone starting at 50 mg per day along with a course of ciprofloxacin. Investigations were performed to rule out associated underlying medical conditions, such as IBD, autoimmune and haematological disease, all of which were negative. It was therefore deemed that the PG developed as a result of pathergy as a result of trauma rather than an associated medical condition. As the wound continued to display no signs of response to treatment a referral was made to the infectious diseases team who have requested another tissue biopsy to retest for atypical mycobacterial infection. The dermatology team were managing the patient at the time this paper was prepared.

Case two

A 79-year-old gentleman presented with a two-month history of non-healing leg ulcers bilaterally. His past medical history included chronic venous insufficiency, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and left total hip replacement. Initially the wounds measured 4 cm x 1 cm on the right lateral lower leg, and 2 cm x 2 cm, on the left medial lower leg. There was evidence of haemosiderin staining, pedal pulses were palpable, and the ulcers were painless. Originally the wounds were managed with local wound care and compression bandaging. However, over time, they gradually increased in size, and became infected and painful. The patient was admitted to hospital for intravenous antibiotics. During this admission the patient had a venous duplex scan, which demonstrated deep venous incompetence of the left leg, lesser saphenous vein, and incompetence of the saphenopopliteal junctions. He had varicose veins in the left calf draining into the lesser saphenous vein. The right lower leg demonstrated a competent deep system; varicose veins were identified draining into both greater and lesser saphenous veins with incompetent valves. Venous ablation was performed on the left short saphenous vein, and stenting of the left common iliac and left external iliac veins. The patient was discharged home and monitored as an outpatient with the support of community nurses for wound care. The wounds continued to deteriorate and the patient was admitted three months later with cellulitis. During this admission the patient underwent diagnostic angiogram and tibial peroneal trunk angioplasty and stent. Over time the ulcers continued to worsen (Figure 4). The patient was admitted for surgical debridement of his wounds. However, on the same day the dermatologists were consulted to review the patient. They diagnosed PG, and advised against any form of debridement due to the risk of pathergy. The patient was commenced on prednisolone 40 mg daily, methotrexate 30 mg weekly, and an increase in analgesic agents. The wounds were cleansed with Prontosan® solution and dressed with PolyMem® silver. The wounds responded well to wound care and systemic corticosteroids (Figure 5).

Case three

A 30-year-old gentleman was referred to the wound clinic for management of a venous leg ulcer. He had a past medical history of ulcerative colitis (currently in remission) and GORD, reoccurring ulcers to the right lower leg for three to four years, and he had recently undergone venous ablation. On examination, there was evidence of a healed ulcer over the anterior aspect of the right lower leg, haemosiderin staining (Figure 6), and an ulcer over the medial aspect of the same leg, small satellite ulcers, and there was also evidence of atrophic cribriform scarring proximal to this lesion (Figure 7). The patient was a fly-in, fly-out worker, five weeks on and five weeks off; therefore, it was difficult to have consistency with wound care. Initially the patient was managed with a silicone foam dressing and compression hosiery 30–40 mmHg, with the patient attending to his own wound care. At his next review the wounds had increased in size, demonstrated violaceous margins and were extremely painful (Figure 8.) An urgent referral was made to see a dermatologist. Biopsy was performed, which demonstrated ulceration associated with inflammation and vascular proliferation with associated small vessel neutrophilic vasculitis and small vessel micro-thrombi. Despite this, based on the clinical appearance of the wounds and the patient’s history of ulcerative colitis, a diagnosis of PG was made and he was commenced on prednisolone 50 mg daily. Over the coming month the wounds did not respond to the immunosuppression agent and the pain increased. A trial of prednisolone 1 mg crushed and applied topically to the wounds was initiated. However, the wounds increased significantly in size (Figure 9). The patient was then commenced on cyclosporine 200 mg and prednisolone 75 mg daily. During this period of time the patient had several admissions for wound infection and pain control. As there was very little response from the immunosuppressive agents, the patient was commenced on weekly infusions of Infliximab; an MRI was also performed to exclude osteomyelitis. There was gradual improvement in the wounds (Figure 10). As would be expected, pain has been an issue; this was managed in collaboration with the acute pain service, at our facility. Unfortunately, during the course of the treatment the patient lost his job.

Discussion

These three case studies illustrate the complexity of diagnosing PG. Two of the cases responded poorly to treatment. This is consistent with the literature where, despite appropriate therapy for PG, there can be a failure for the wounds to progress27. Underlying conditions should be treated; however, PG can also occur when the underlying condition is in remission27, as was the situation with case three. The second case did have underlying RA; however, he responded well to systemic treatment for PG.

When treating patients with suspected PG, one must always be open to the possibility of misdiagnosis. Indeed, many other ulcerating wounds can mimic PG30,37. Weenig et al. reported that out of 157 patients being treated for PG, 10% (n=15) were found not to have PG37. The consequences of misdiagnosis can be disastrous; particularly taking into account that the immunosuppressive agents used to treat PG may be contraindicated in other conditions37. Systemic immunosuppression can also make the patient vulnerable to infection, as was the case with patient three who had several admissions to hospital with wound infection. In a study conducted by Weenig et al., they identified six broad disease categories that can mimic PG: vascular occlusive or venous disease; vasculitis; malignancy; exogenous tissue injury; infection; and other inflammatory disorders37. All three of the patients had underlying venous disease and were managed according to best practice49, with appropriate wound care, compression bandaging or compression hosiery and, where clinically indicated, surgical intervention. Treating the ulcer as venous in origin possibly delayed the diagnosis of PG.

The accurate diagnosis of PG is challenging. The proposed diagnostic criteria by Su et al. aids the clinician with the diagnosis of PG30; this should not be used in isolation but as a guide. Independently, Von den Driesch had previously developed a diagnostic criteria for PG50. The criteria are virtually the same as the one developed by Su et al. von den Driesch studied 44 patients with PG, where each patient was diagnosed using a standardised diagnostic criteria. There was long-term follow-up in 42 of the patients in the study cohort. Adopting a diagnostic criterion into clinical practice could potentially reduce the number of cases misdiagnosed with PG.

Treatment of PG remains challenging to the clinician. Treatment is typically based on the individual requirements of the patient, underlying medical conditions, the presence of diseases associated with PG, and the extent of the ulceration2. The main goal of therapy is to reduce inflammation, control pain and promote healing1. Recommended first-line treatment is appropriate wound care, with topical and/or systemic corticosteroids1,2. In the three cases, patient two responded well to a combination of prednisolone, methotrexate, and simple wound care. However, the other two cases proved to be challenging.

Conclusion

Despite first being described almost a century ago, the diagnosis and management for patients with PG remains complex. Although three cases were presented, each of them proved challenging in diagnosis and treatment. Indeed, at the time of writing this paper two of the patients were still proving to be difficult to manage. Endless pain affects patients’ quality of life. Unfortunately one of the patients lost his job due to repeated hospital admissions, which put strain on his marriage and his ability to pay his mortgage.

Misdiagnosis of PG can have devastating consequences, using the diagnostic criteria proposed by Su et al. should aid the clinician with diagnosis of PG. As there is a lack of specific guidelines for the treatment of PG, we recommend referral to a dermatologist or physician. A multidisciplinary approach is essential in managing this complex condition.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have a conflict of interest to declare.

Author(s)

Donna Evealyne Angel*

RN, NP, BN, MSc, PGDip(Clin Spec), Royal Perth Hospital

Royal Perth Hospital

Wellington Street, GPO Box XX2213

Perth, WA 6847, Australia

Tel: (08) 9224 2244

Email: donna.angel@health.wa.gov.au

Johanna Lee van Rooyen

RN, BN, PGDip(Clin Nur)

* Corresponding author

References

- Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2012;13(3):191–211.

- Teagle A, Hargest R. Management of pyoderma gangrenosum. J R Soc Med 2014;107(6):228–36.

- Brusting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol 1930;22:655–80.

- Rucco E, Sangiuliano AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Dermatol Venerol 2009;23(9):1008–17.

- Powell FC, Su WPD, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum and sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol 1984;120(7):959–60.

- Powell FC, Su WPD, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: classification and management J AM Acad Dermatol 1996;3(3):395–409.

- Farhi DC, Cosnes J, Zizi N, Chosidow O, Seksik P, Beaugerie L et al. Significance of erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study of 2, 402 patients. Medicine 2008;87(5):281–93.

- Langan SM, Groves WR, Card TR, Guillford MC. Incidence, mortality, and disease associations of pyoderma gangrenosum in the United Kingdom: a retrospective cohort study. J Invest Dermatol 2012;132:2166–70.

- Bennett ML, Jackson JM, Jorizzo JL, Fleischer ABJ, White WL, Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum a comparison of typical and atypical forms with an emphasis on time to remission. Case review of 86 patients from 2 institutions. Medicine 2000;79(1):37–46.

- Powell FC, Schroeter AL, Su WPD, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. Q J Med 1985;55:173–6.

- Allen CP, Hull J, Wilkinson N, Burge SM. Pediatric pyoderma gangrenosum with spleenic and pulmonary involvement. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;20(4):497–9.

- Ramesh MB, Shetty SS, Kamath GH. Pyoderma gangrenosum in childhood. Int J Dermatol 2004;43(3):205–7.

- Torrelo A, Colmenero I, Serrano C, Vilanova A, Naranjo R, Zambrano A. Pyoderma gangrenosum in infants. Pediatr Dermatol 2006;23(4):338–41.

- Binus AM, Qureshi AA, Winterfield LS. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a retrospective review of patient characteristics comorbidities and therapy in 103 patients. Br Assoc Dermatol 2011;165(6):1244–50.

- Lear J, Atherton M, Byrne G. Neutrophilic dermatoses: Pyoderma gangrenosum and sweet’s syndrome. Postgrad Med J 1997(73):65–.

- Parren L, Ruud G, Nellen R, van Marion A, Henquet C, Frank J et al. Penile pyoderma gangrenosum: successful treatment with colchicine. Int J Dermatol 2008;47(suppl. 1):7–9.

- Brown R, Lay L, Graham D. Bilateral pyoderma gangrenosum of the hand: treatment with dapsone. J Hand Surg [Br] 1993;Feb(18):115–8.

- Adachi Y, Kindzelskii A, Cookingham G, Moore E, Todd R, Petty H. Aberrant neutrophil trafficking and metabolic oscillations in severe pyoderma gangrenosum. J of Investig Dermatol 1998;111(2):259–68.

- Alberts J, Sams H, Miller J, King LJ. Familial ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 2 kindred. Cutis 2002;69(6):427–30.

- Khandpur S, Mehta S, Reddy B. Pyoderma gangrenosum in two siblings: a familial predisposition. Pediatr Dermatol 2001;(18):4.

- al-Rimawi H, Abuekteish F, Daoud A, Oboosi M. Familial pyoderma gangrenosum presenting in infancy. Eur J Pediatr 1996;155(9):759–62.

- Shands JJ, Flowers F, Hill H, Smith J. Pyoderma gangrenosum in a kindred. Precipitation by surgery or mild physical trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;16(5):931–4.

- Wise C, Gillum J, Seidman C, Lindor N, Veile R, Bashiardies S et al. Mutations in CD2BP1 disrupt binding to PTP PEST and are responsible for PAPA syndrome, an autoinflammatory disorder. Hum Mol Genet 2002;11(8):961.

- Farasat S, Aksentijevich I, Toro J. Autoinflammatory diseases: clinical and genetic advances. Arch Dermatol 2008;144(3):392–402.

- Guenova E, Teske A, Fehrenbacher B, Hoeber S, Adamczyk A, Schaller M et al. Interleukin 23 expression in pyoderma gangrenosum and targeted therapy with ustekinumab. Arch Dermatol 2011;147(10):1203.

- Oka M, Berking C, Nesbit M, Satyamoorthy K, Schaider H, Murphy G et al. Interleukin-8 overexpression is present in pyoderma gangrenosum ulcers and leads to ulcer formation in human skin xenografts. Lab Invest 2000;80(4):595–604.

- Margolis D. Management of unusual causes of ulcers of lower extremities. JWOCN 1995;22(2):89–94.

- Wolina U, Haroske G. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Cur Op Rheumat 2011;23(1):50–6.

- Wollina U. Clinical management of pyoderma gangrenosum. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002;3(3):149–58.

- Su WPD, Davies MPD, Weening RH et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol 2004;43(11):790–800.

- Hadi A, Lebwohl M. Clinical features of pyoderma gangrenosum and current diagnostic trends. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64(5):950–4.

- Barr KL, Chatwal HK, Wesson SK, Bhattacharyya I, Vincek V. Pyoderma gangrenosum masquerading as necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Otolaryngol 2009;30(4):273–6.

- Mahajan A, Ajmal N, Barry J, Barnes L, Lawlor D. Could your case of necrotising fascitis be pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Plast Surg 2005;58(3):409–12.

- Hughes A, Jackson J, Callen J. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Med Assoc 2000;284:1546–8.

- Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet 1998;351:581–5.

- Spear M. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an overview. Plast Surg Nurs 2008;28(3):154–7.

- Weenig R, Davis M, Dahl P, Su W. Skin Ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. N Engl J Med 2002;347(18):1412–8.

- Miller J, Yentzer B, Clark A, Joizzo J, Feldman S. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review and update on new therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62(4):646–54.

- Shultz CG, Sibbald G, Falanga V, Ayello EA, Dowsett C, Harding K et al. Wound bed preparation: a systemic approach to wound management. Wound Rep Reg 2003;11(2 Supp):S1–S25.

- Leaper DJ, Schultz G, Carville K, Fletcher J, Swanson T, Drake R. Extending the TIME concept: what have we learned in the past 10 years. Int Wound J 2014;9(Suppl. 2):1–19.

- Groves R, Schmidt-Lucke J. Recombinant human GM-CSF in the treatment of poorly healing wounds. Adv Skin Wound Care 2000;13:107–12.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco V. The benefits of smoking in skin disease. Clin Dermatol 1998;16:641–7.

- Kanekura T, Kanzaki T. Successful treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with nicotine chewing gum. J Dermatol 1995;22:704–5.

- Friedman S, Marion JF, Scherl E, Rubin PH, Present PA. Intravenous cyclosporine in refractory pyoderma gangrenosum complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2001;7(1):1–7.

- Gottrup F, Karlsmark T. Leg ulcers: uncommon presentations. Clin Dermatol 2005;23(6):601–11.

- Classen D, Thomson C. Free flap coverage of pyoderma gangrenosum leg ulcers. J Cutan Med Surg 2002;6(4):327–31.

- Toyozawa S, Yamamoto Y, Nishide T, Kishioka A, Kanazawa N, Matsumoto Y et al. Case report; a case of pyoderma gangrenosum with intractable leg ulcers treated by allogenic cultured dermal substitutes. Dermatol Online J 2008;14(11):17.

- Niezgoda J, Cabigas E, Allen H, Simanonok J, Kindwall E, Krumenauer J. Managing pyoderma gangrenosum: a synergistic approach combining surgical debridement, vacuum assisted closure, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Plast Reconst Surg 2006;117(2):24e–8e.

- Australian Wound Management Association. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the prediction and prevention of pressure ulcers. Perth, Western Australia: Cambridge Publishing; 2001.

- von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol 1997;137(6):1000–5.