Volume 25 Number 3

Lessons learnt following my volunteer work in low-resource communities

Jan Rice

Keywords education, Infection, structure, table of antiseptics

Abstract

Wound management principles are applicable to the management of wounds in any setting. The question is, what is achievable? I have encountered wound complexities never seen back in my normal working environment. Working with Interplast Australasia, I visited the Solomon Islands twice-yearly for eight years (between 2009 and 2016) with the aim of improving wound care within the surgical unit. Formal classroom presentations and one-on-one training was conducted in the surgical unit. I did my last tour in April 2016 as my goals had been achieved: cleanliness of the unit improved; staff had a more structured approach to performing dressing procedures and were able to implement the newly developed solutions guide effectively and there were improved healing outcomes for their patients. Modern dressings at this time have little benefit in a resource-poor setting and the solutions guide was something that is sustainable now and into the future.

Background relevance

In considering resource-poor communities, it is relevant to review some data to put things into perspective. According to a people-powered organisation, “nearly half of the world’s population — more than 3 billion people — live on less than $2.50 a day. More than 1.3 billion live in extreme poverty — less than $1.25 a day. One billion children worldwide are living in poverty. According to UNICEF, 22,000 children die each day due to poverty”. www.dosomething.org

In looking at data from the World Bank, it is possible to begin to feel that some progress is being made; however, whilst the poverty rates have declined in all regions, the progress has been uneven:

• The reduction in extreme poverty between 2012 and 2013 was mainly driven by East Asia and Pacific (71 million fewer poor) — notably China and Indonesia — and South Asia (37 million fewer poor) — notably India.

• Half of the extreme poor live in Sub-Saharan Africa. The number of poor in the region fell only by 4 million, with 389 million people living on less than US$1.90 a day in 2013, more than all the other regions combined.

• A vast majority of the global poor live in rural areas and are poorly educated, mostly employed in the agricultural sector, and over half are under 18 years of age.

The work to end extreme poverty is far from over, and a number of challenges remain. It is becoming even more difficult to reach those remaining in extreme poverty, who often live in fragile contexts and remote areas. Access to good schools, health care, electricity, safe water and other critical services remains elusive for many people, often determined by socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity, and geography. “Moreover, for those who have been able to move out of poverty, progress is often temporary: economic shocks, food insecurity and climate change threaten to rob them of their hard-won gains and force them back into poverty”. www.worldbank.org

There are many regions which need help to raise their basic standard of living and improve the health conditions of their people. I have been a volunteer with Interplast Australia & New Zealand Pty Ltd since 1994 and have worked in Fiji, Samoa, Cook Islands, Indonesia, Bande Aceh, Solomon Islands, Bangladesh and Papua New Guinea. My role on these trips is as a nurse educator. The primary goal is to educate the nurses and other health professionals working in the surgical units in ways to care for the post-operative plastic surgical patients when our surgical teams are working in the hospital. The secondary goal is to transfer knowledge on wound care and the management of all surgical patients in order to achieve better surgical outcomes.

First piece of advice

One of the first considerations in volunteer work is “what aid agency to register with?” My suggestion is to select a well-established agency. These agencies will generally provide you with clear guidelines on your role and the activities you may be required to participate in, your emergency contact details and what to do if your safety is at risk.

Second piece of advice

It is very natural to leave Australia with grand ideas of how you will provide assistance. The reality is that all preconceived ideas are lost once you have done your own reconnaissance of the facility and spoken with staff about their concerns and how they would really like you to help. Usually on the first day, a full tour of the facility is conducted and engagement with senior staff to determine their needs and expectations.

It is common for resource poor communities to have many non-government organisations (NGOs) visiting and offering aid. This can be problematic as staff within the facilities get very tired of ‘being told’ how they should tackle their problems by teams that ‘drop in and then drop out’ of their country. It is important to realise that little steps lead to results — slowly, slowly — identify the major area to tackle and then a subset of steps needed to achieve the major effect — perhaps five years on.

Wound care in resource-poor communities

The usual day working on the ward would involve no dressings, no dressing trays or instruments, and only normal saline or povidone-iodine as cleansing solutions. Very occasionally there is excitement when a box of donated modern dressings is found; however, this can also be problematic if there are no clear instructions on how and when these modern dressings are to be used; staff not familiar with the products tend to leave them in the box and eventually they are well past their expiry date and not able to be used.

The wound types I have worked on include: skin graft recipient and donor sites, flap repairs, burns, septic diabetic foot wounds and severe trauma wounds, burns, and cleft lip and palate repairs. Being located in tropical regions, infection is the most common issue faced. Surgeons decide and prescribe the wound management plan and in general every wound is dressed with normal saline 3–4 times per day and extra gauze and bandages when available.

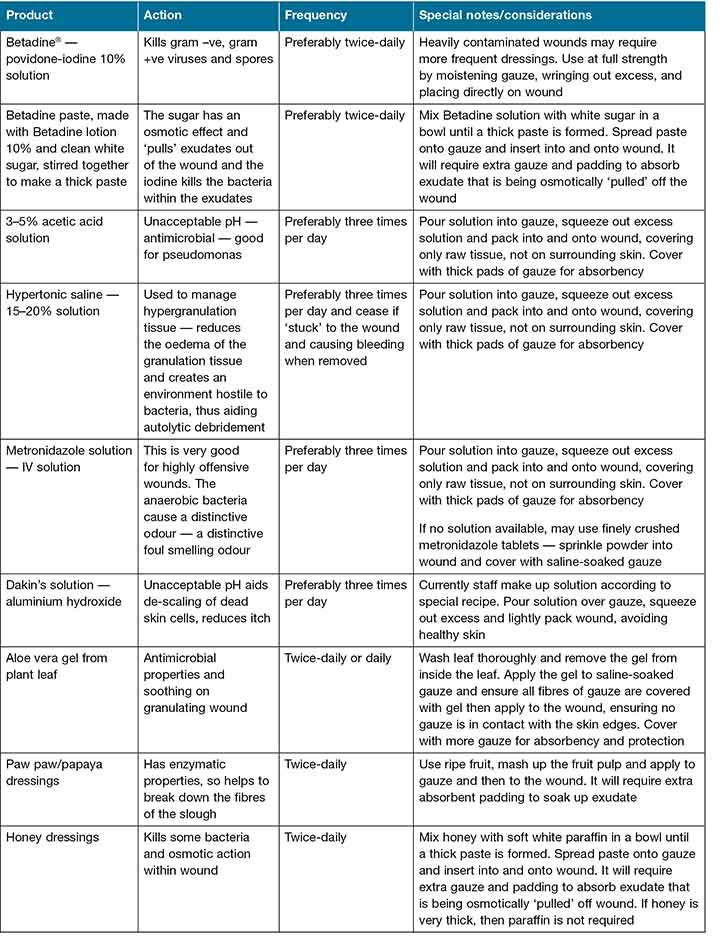

No matter what country I was working in, when the dressings were taken down I was confronted with the same infected, slimy wound base and in many circumstances loss of skin graft. After some time and many presentations to senior medical staff within the hospitals I put forward a plan of treatment offering dressing solution alternatives. This information has been shared across the region and surgeons are reporting better quality granulation tissue and less infection, with somewhat improved healing rates (Table 1).

Table 1: Suggested solutions antiseptic agents for wound care in resource-poor communities

The following photos are of a man admitted with an abscess which nurses had been instructed to dress three times a day with normal saline. Our program taught them to initiate further discussion with surgeons and their concerns that saline was doing nothing. Following surgery to further expose the necrotic cavity, povidone-iodine solution gauze packing was commenced. The wound visibly improved each day and staff were pleased to see the fruits of their labour result in faster healing of the area. Due to my short stay I have no follow-up images, but was informed the patient healed well and within a much shorter time frame than patients previously treated with normal saline dressing 3–4 times per day.

1. Abscess on first day of sighting

2. Abscess being drained manually

3. Abscess following twice-daily Betadine-soaked gauze dressings and prior to further surgery

4. After laying open the abscess

5. Covered with gauze and cotton wool dressing made by nursing staff

The dressing is not everything

It is well documented that dressings are a small part of wound healing and it may come as a shock to know that many people within these regions are both micro and macro nutrient malnourished. Fish and all the wonderful fruits grown in the region are sold to first world countries and the locals eat rice and packet noodles. Malnutrition leads to infection and further delay of healing. The result of chronic infection and failure to heal is extended length of stay in hospital. It is not unusual for a person with diabetes and a serious foot wound to spend 6–12 months in hospital and generally only a carbohydrate diet is provided by the hospital. Family and relatives are meant to supplement the diet with what protein they can afford and fruit.

To help reduce hospital length of stay, I proposed to the National Pharmacy Services Division and Ministry of Health of the region that patients with serious wounds commence oral nutritional supplements, as these are readily available through aid programs and World Health Organization minimum medicines inventory for developing countries.

Organisational structure

Sadly, in many of the countries where I have worked, the nursing staff in senior positions have only achieved their senior ranking due to length of service, not knowledge. Guiding these senior staff on ward routines and how to manage the workload with limited resources and provide mentorship and guidance to their staff has been a challenge.

Over the years I have learnt that it is best to work on the wards in the morning and conduct formal teaching in the afternoon, as the bulk of the work takes place in the morning and staff numbers drop dramatically in the afternoon. Basic nursing care is taught — keeping the approach simple but structured. Organisational structure and general hospital hygiene are always tackled. Absenteeism and lateness for duty are problems yet to be resolved. Many staff struggle to get from their remote villages to the hospital using unreliable public transport and when weather impacts on road safety the problems are exacerbated.

Donated goods

As many of the countries I have worked in do not and may never have what we call modern dressing products, sending these to our regional areas as donations is complicated. Unless the packages contain easy-to-use instructions with consideration of humidity and wound types they will remain in their packaging until a volunteer arrives to provide more guidance on their usage. Personally I have always felt it is better we teach these communities how to use what they have access to and what they can sustain, rather than to dangle carrots with what is commonly used in more progressive countries. The solutions guide has been adopted in the Solomon Islands with reported improvement in patient healing outcomes.

Programs of education

There will always be a need to share our knowledge with those less fortunate. I would encourage anyone who has a desire to help our neighbours in resource-poor communities to consider developing training programs around the following topics, as I see this need growing with every volunteer trip I do. The programs would include:

- Basic principles of wound care

- Empowerment and liaising with doctors

- Understanding diabetes and the care of feet and lower limbs

- Breast self-examination

“We must plant the seed, go back and water it and eventually it grows”.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no disclosure of conflict of interest.

Photography

Patients consented to have images published for continuing education of health professionals.

Author(s)

Jan Rice

Director, WoundCareServices Pty Ltd

Email Woundconsultant8@gmail.com