Volume 26 Number 2

Evidence summary: Moisture associated skin damage: classification and assessment

Emily Haesler

Keywords Moisture associated skin damage, incontinence associated dermatitis, peristomal dermatitis, periwound dermatitis, intertrigo, assessment

Question

What is the best available evidence on strategies to assess moisture associated skin damage?

Summary

Moisture associated skin damage (MASD) is caused by exposure of the skin to moisture, especially when in conjunction with damage to the skin from shear, friction or chemical sources (Level 5 evidence). Moisture associated skin damage should be categorised according to the location and severity of skin damage. Assessment should consider the visual appearance of the skin and characteristics of the individual that could be contributing to skin damage (Level 5 evidence). Assessment tools for MASD that have had psychometric properties evaluated (e.g. Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis Intervention Tool [IADIT] and The IAD Skin Condition Assessment Tool) report good interrater reliability (Level 3e evidence).

Best practice recommendations

When assessing skin damage, evaluate the location, skin appearance and characteristics of the individual to determine an underlying cause. (Grade B recommendation)

Consider using a formal tool to assess moisture associated skin damage. (Grade B recommendation)

Background

Moisture associated skin damage is an overarching term that describes damage to the skin as a result of exposure to moisture. The moisture causing skin damage can arise from different sources, including (but not limited to):1-3

• urinary incontinence

• faecal incontinence

• wound exudate

• perspiration

• stomal effluent

• saliva or mucous

Skin that is exposed to moisture becomes soft, wrinkled and inflamed, increasing the risk of erosion and a break to the skin. Damage occurs in the presence of friction and/or shear and/or chemical forces.1, 4, 5 The precise mechanism by which moisture damages the skin is not fully understood,6 but is thought to occur due to physical changes in the stratus corneum (horny layer)7, 8 as the corneocytes absorb excess fluid and become over-hydrated.4 The inflammatory response to moisture exposure increases transepidermal water loss, decreasing the skin’s moisture barrier effect and increasing skin pH.5, 6

Once the skin becomes inflamed, the disruption to natural skin barrier defences, often together with potential breaks to the skin barrier caused by mechanical forces (e.g. shear or friction) or chemical sources (e.g. alkaline pH of moisture source), increases the risk of skin infection.1, 4, 5

Clinical bottom line

Aetiology and classification of MASD

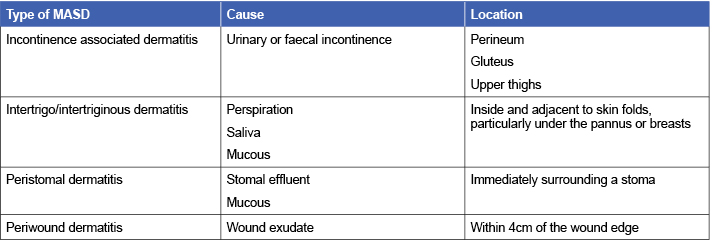

Moisture associated skin damage is categorised according to the anatomical location and type of moisture associated with skin damage. Expert consensus1, 9 and single expert opinion3,7,8 describe four types of MASD: periwound dermatitis, peristomal dermatitis, intertrigo/intertriginous dermatitis and incontinence associated dermatitis (Level 5 evidence).

Expert consensus1 and single expert opinion3, 6, 7 outline the classification of MASD according to location and primary cause, as summarised in Table 1 (Level 5 evidence).

Table 1: Factors related to the individual to consider in assessment of MASD1, 3, 6, 7

Identifying MASD: Assessing the individual

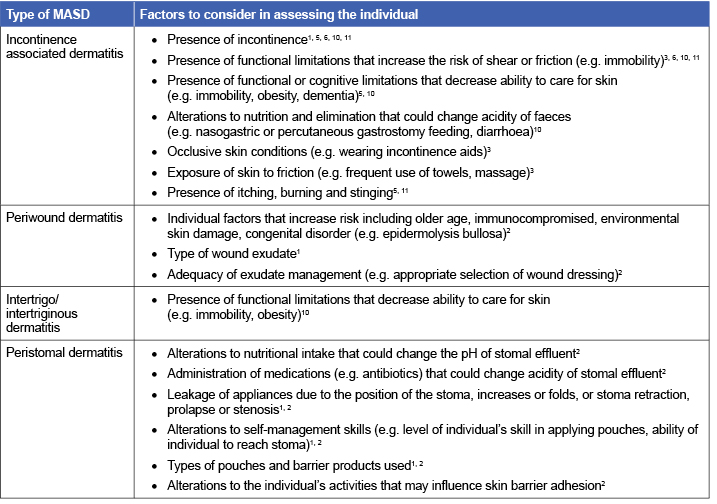

Expert consensus1, 2, 10, 11 and single expert opinion3, 5 detail components to include in a focused assessment of the individual for MASD, as summarised in Table 2 (Level 5 evidence).

Table 2: Factors related to the individual to consider in assessment of MASD

Identifying MASD: Assessing the skin

Synthesised expert opinion,11 expert consensus1, 3, 10 and single expert opinion3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 13 suggest that inspecting the skin is the only way to identify MASD. Visual characteristics of MASD include: (Level 5 evidence)

- Superficial inflammation of the skin1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 11

- Superficial erosion/denudation may be present1, 3, 14

- Peristomal or periwound ulceration commonly present due to uncontrolled leakage14

- Erythema, lesions may appear bright or dark red1,3,5,6,8,11

- Shiny appearance of the skin3

- Lesions occur over anatomical sites with no bony prominence1

- Lesions have diffuse and irregular margins1, 3, 5, 11

- Signs of accompanying infection may be present1

- Blisters may be presents3, 5, 6, 8, 11, 13

- Perilesional regions macerated with a white-yellow colour may be present1

- Lesions may appear as intermingled red-pink and white-yellow colouring with scaling1, 3

- Hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation are visible on darkly pigmented skin (e.g. may have purple tone)3,5,10,11

- Either no exudate or clear, serous exudate (“weeping”)5,6,11

- Necrosis will not be present5, 11

Identifying MASD: Assessment tools

Few valid and reliable tools are available for assessing MASD.

Expert reports10, 11, 15 identify three tools (first published pre-2007) that have not been formally validated. The Perineal Assessment Tool, Peri-rectal Skin Assessment Tool (PSAT) and the Perineal Dermatitis Grading Scale all focus on assessment of IAD. The tools include evaluations of skin appearance (level of erythema/colour, extent of skin erosion/integrity), types of irritants (e.g. urine, liquid stool, solid stool), level of exposure and pain experience10, 11 (Level 5 evidence).

A diagnostic study16 reported a tool to evaluate severity of IAD, The IAD Skin Condition Assessment Tool. The tool includes evaluations of the presentation of the skin (level of erythema, rash and skin breakdown) at 13 different anatomical locations. The tool was used by 347 wound ostomy and continence nurses to evaluate IAD in four photo-based case studies. Criterion validity and interrater reliability were reported to be high16 (Level 3e evidence).

Psychometric properties of the Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis Intervention Tool (IADIT) are also reported. The tool is used to classify IAD and the risk of the patient by presenting images with descriptors of various severities of IAD.15, 17 In a validation17 of the German version of the tool (IADIT-D) conducted in nursing home residents, high interrater reliability is reported (k=0.57 to 1.00 across three domains and k=0.69 for total tool)17 (Level 3e evidence).

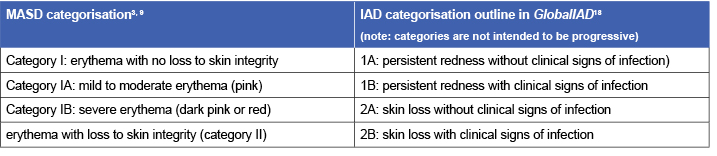

Classifying MASD

The literature search identified expert consensus9, 18 and single expert opinion3 sources that proposed systems to categorise MASD and IAD (see Table 3) (Level 5b evidence).

Table 3: Systems to categorise MASD and IAD

Table 4: Differentiation of IAD from pressure injuries3, 12

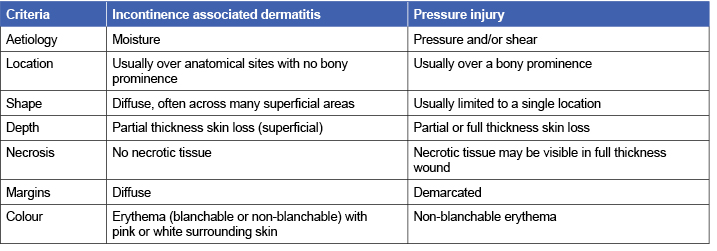

Differentiating MASD from other skin conditions

Differentiation of MASD from other skin condition is important. Evidence on this topic generally focuses on differentiating IAD from pressure injuries. Expert opinion3, 12 suggests that the criteria outlined in Table 3 are important in differentiating IAD from pressure injuries (Level 5 evidence).

Characteristics of the evidence

This evidence summary is based on a structured database search combining search terms that describe moisture associated skin damage and assessment. Searches were conducted in EMBASE, CINAHL, Medline, the JBI Library and the Cochrane Library. Only citations published from January 2007 to June 2017 in English were considered for inclusion. The evidence in this summary comes from:

- Observational studies with no control group16, 17 (Level 3e evidence)

- Systematic review of expert opinion11 (Level 5a evidence)

- Expert consensus opinion1-3, 6, 9, 10, 18 (Level 5b evidence)

- Expert opinion4, 5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 15 (Level 5c evidence)

Author(s)

Emily Haesler

Wound Healing and Management Node

References

- 1Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM, Bliss DZ, Colwell JC, Goldberg M, Kennedy-Evans KL, Logan S, Ratliff CR. Moisture-associated skin damage: Overview and pathophysiology. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2011. May-June;38(3):233-41. (Level 5 evidence).

- Colwell JC, Ratliff CR, Goldberg M, Baharestani MM, Bliss DZ, Gray M, Kennedy-Evans KL, Logan S, Black JM. MASD Part 3: Peristomal moisture-associated dermatitis and periwound moisture-associated dermatitis: A consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2011;38(5):541-53. (Level 5b evidence).

- Beeckman D. A decade of research on Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis (IAD): Evidence, knowledge gaps and next steps. J Tissue Viability, 2017;26(1):47-56. (Level 5c evidence).

- Collier M, Simon D. Protecting vulnerable skin from moisture-associated skin damage. Br J Nurs, 2016. 10 Nov;25(20 Supplement):S26-32. (Level 5c evidence).

- Zulkowski K. Diagnosing and treating moisture-associated skin damage. Adv Skin Wound Care, 2012. May;25(5):231-6. (Level 5c evidence).

- Langemo D, Hanson D, Hunter S, Thompson P, Oh IE. Incontinence and incontinence-associated dermatitis. Adv Skin Wound Care, 2011. Mar;24(3):126-40. (Level 5c evidence).

- Voegeli D. Moisture-associated skin damage: Aetiology, prevention and treatment. Br J Nurs, 2012;21(9):517-21. (Level 5c evidence).

- Voegeli D. Moisture-associated skin damage: An overview for community nurses. Br J Community Nurs, 2013. January;18(1):6-12. (Level 5c evidence).

- Garcia-Fernandez FP, Soldevilla Agreda JJ, Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL, Verdu-Soriano J, Lopez Casanova P, Rodriguez-Palma M. Classification of dependence-related skin lesions: a new proposal. J Wound Care, 2016;25(1):26, 8-32. (Level 5b evidence).

- Black JM, Gray M, Bliss DZ, Kennedy-Evans KL, Logan S, Baharestani MM, Colwell JC, Goldberg M, Ratliff CR. MASD part 2: Incontinence-associated dermatitis and intertriginous dermatitis: A consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2011;38(4):359-70. (Level 5b evidence).

- Gray M, Beeckman D, Bliss DZ, Fader M, Logan S, Junkin J, Selekof J, Doughty D, Kurz P. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: A comprehensive review and update. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2012;39(1):61-74. (Level 5a evidence).

- Beeckman D, Woodward S, Gray M. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: Step-by-step prevention and treatment. Br J Community Nurs, 2011. August;16(8):382-9. (Level 5c evidence).

- Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. Incontinence in the aged: Contact dermatitis and other cutaneous consequences. Contact Derm, 2007;57(4):211-7. (Level 5c evidence).

- Carville K. Wound Care Manual 7th ed ed. Osborne Park, WA: Silver Chain Foundation; 2017.(Level 5.c evidence).

- Junkin J, Selekof JL. Beyond “diaper rash”: Incontinence-associated dermatitis: does it have you seeing red? Nursing, 2008;38(11 Suppl):56hn1-10. (Level 5c evidence).

- Borchert K, Bliss DZ, Savik K, Radosevich DM. The incontinence-associated dermatitis and its severity instrument: development and validation. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2010;37(5):527-35. (Level 3e evidence).

- Braunschmidt B, Muller G, Jukic-Puntigam M, Steininger A. The inter-rater reliability of the incontinence-associated dermatitis intervention tool-D (IADIT-D) between two independent registered nurses of nursing home residents in long-term care facilities. J Nurs Meas, 2013;21(2):284-95. (Level 3e evidence).

- Beeckman D, Van den Bussche K, Alves P, Beele H, Ciprandi G, Coyer F, de Groot T, De Meyer D, Dunk AM, Fouri A, García-Molina P, Gray M, Iblasi A, Jelnes R, Johansen E, Karadağ A, Leblancq K, Kis Dadara Z, Long MA, Meaume S, Pokorna A, Romanelli M, Ruppert S, Schoonhoven L, Smet S, Smith C, Steininger A, Stockmayr M, Van Damme N, Voegeli D, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S, Woo K, Kottner J. The Ghent Global IAD CategorisationTool (GLOBIAD). Ghent University: Skin Integrity Research Group2017. (5b evidence).