Volume 27 Number 4

Patient perspectives: explaining low rates of compliance to compression therapy

Francisca Chitambira

Keywords compliance, venous leg ulcers, Chronic Venous Insufficiency, compression therapy, compression bandaging /stockings

For referencing Chitambira F. Patient perspectives: explaining low rates of compliance to compression therapy. Wound Practice and Research 2019; 27(4):168-174.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.27.4.168-174

Abstract

Background Although varied interventions are used to prevent venous leg ulcers (VLUs), compression therapy remains the gold standard for VLU prevention and treatment1–3. However, non-compliance remains an issue. What is it then that makes it difficult for patients to comply? Subsequently, this review paper aims to explain the reasons and contributing factors that attribute to patients’ non-compliance to compression therapy with a view of finding strategies that can increase adherence.

Method A literature search was undertaken using the terms ‘compression therapy’, ‘compliance’ and ‘venous leg ulcers’. Articles that reported reasons for non-compliance or adherence to compression therapy were included. Seventeen articles met the inclusion criteria. The reasons for non-compliance were tabulated and subjected to thematic analysis.

Results Five determinant themes regarding patients’ reasons for non-compliance with compression therapy emerged – pain and discomfort, psychosocial issues, knowledge deficit, physical limitations, and financial issues.

Discussion Compliance with compression is the key to achieving wound healing in patients with VLUs but compliance rate remains low. Consequently, effort needs to be made by healthcare professionals (HCPs) to improve compliance and therapeutic relationships through holistic patient assessment that addresses their experiences and values their individualism, health beliefs, lifestyle and social networks4,5. Further studies to identify intervention strategies that can increase their compliance are required.

What is known on this topic?

- Evidence-based guidelines for the prevention and management of VLUs recommend compression therapy as the gold standard treatment strategy for VLUs.

- Uptake and compliance with compression therapy promotes VLU healing and can prevent recurrence when compared to no compression.

- Many patients cannot tolerate or comply to compression therapy.

What this paper adds

- Being non-judgemental and supportive allows HCPs to monitor patients’ beliefs and health behaviours about compression therapy, and this also assists them in planning individualised intervention strategies that can increase compliance rates.

Introduction

Compression therapy is the cornerstone of management for patients with chronic venous insufficiency1–7. Likewise, evidence-based treatment from HCPs also recommends it as the gold standard treatment for venous ulceration, and clinical trials have proved it to be effective in healing VLUs and preventing their recurrence1,6,8–11. Venous leg ulcers significantly impact patients’ socioeconomic status, reducing their quality of life and productive work time4,5. Furthermore, Balcombe et al.5 believe that, in Western countries, its care accounts for 2% of the healthcare budget. Notably, a Cochrane review confirmed that ongoing compression therapy post-healing reduces recurrence at 3 years compared to no compression8.

However, despite the clear benefits of compression therapy in VLU management, poor compliance affects this outcome and, according to Armstrong and Meyr6, approximately 60–70% of patients are non-compliant, especially with paste compression bandages. Consequently, recurrence often occurs, with estimates as high as 70%, thereby causing frustration to patients and HCPs and negatively affecting therapeutic relationships8.

As pointed out by Bainbridge7, the terms compliance, adherence and concordance are mainly used in the literature to describe the extent to which patients’ behaviour matches the agreed recommendations from the HCP. However, whilst the term compliance has been traditionally used, lately it has been viewed negatively as it gives the impression that patients should be yielding or submitting to recommendations from the prescriber. Instead, adherence is considered to capture the concept that the patient is agreeing to a plan, rather than having one imposed; concordance refers to patient satisfaction and the establishment of cooperative therapeutic relationships with HCPs7,12. All of these require participation from both the patient and the HCPs to determine the course of the agreed behaviour that the patient can follow. As such, these terms will be used in this paper interchangeably.

The aim of this paper is to review available data on the reasons for patients’ low rate of compliance to compression therapy, subject results to analysis, and then discuss the contributing factors with a view of reversing this trend.

Literature search / methodology

A systematic literature search was performed covering the period from January 2009 to May 2019 using the CINAHL Complete (via EBSCO host), EMBASE, EMCARE, MEDLINE and PubMed via Ovid SP, the Cochrane Library and UpToDate databases using the search terms and Boolean operators venous leg ulcers AND compression AND compliance. The initial search identified 13 articles of high relevance. Only peer-viewed articles in English were included. The search was widened using the truncation terms ‘attitude*’ or perspectiv* or view* or complian*’ and 64 articles were returned. Same limiters were applied, duplicates removed, and a further 25 articles were identified.

The reference list of the identified 38 articles was then hand searched for papers of importance and to identify key researchers in the field, and a further six articles were retrieved. The full texts of these 44 articles were screened, and 27 articles excluded as they did not discuss reasons for patients’ non-compliance with compression therapy. Finally, a total of 17 articles were included in the literature review.

Results

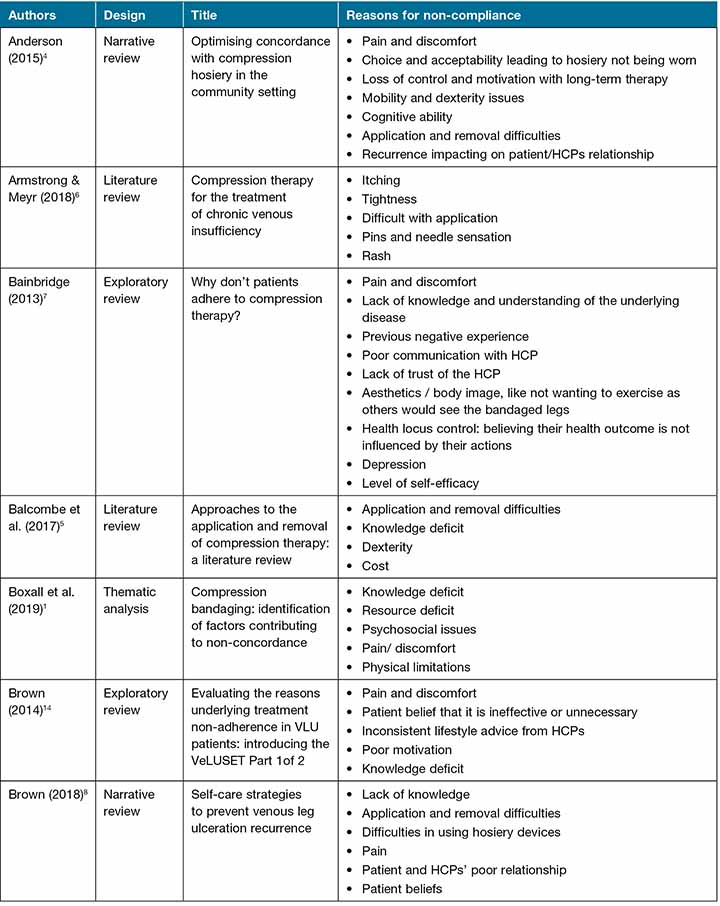

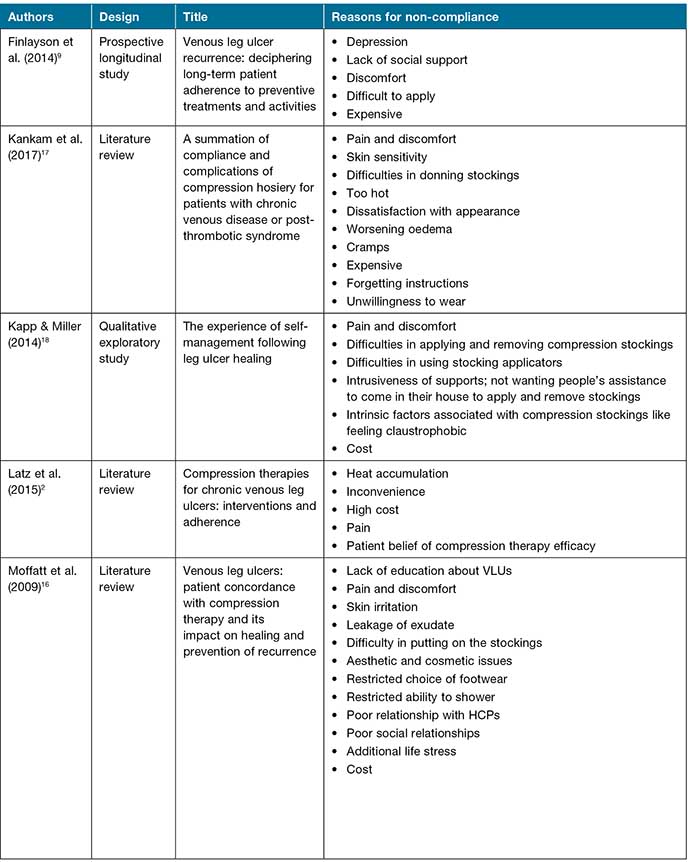

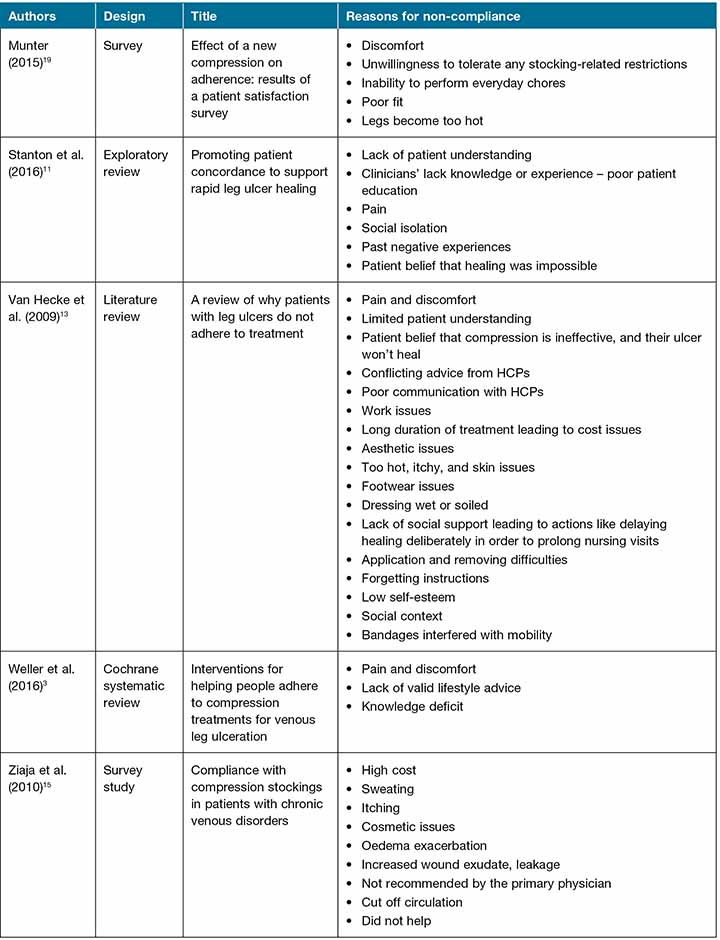

The full texts of the chosen articles were read, and the reasons for patients’ non-compliance as reported in each article were tabulated – this information is provided in Table 1. The reasons for non-compliance are diverse and the list is extensive, with significant overlaps between studies. Based on current evidence, it is impossible to accurately predict or anticipate patient compliance because of the complexity of the issue, therefore researchers7,13 concluded that every patient has the potential for non-compliant behaviour. Only four of the included studies reported the identified reasons for patients’ non-compliance to compression therapy as a primary area of investigation1,7,14,15. The majority of the studies included were reviews, and some of them were more comprehensive because the authors undertook thematic analyses of their literature searches1,3,13,16.

Table 1. Reasons for low rates of non-compliance to compression therapy as reported in the literature.

Table 1 continued. Reasons for low rates of non-compliance to compression therapy as reported in the literature.

Table 1 continued. Reasons for low rates of non-compliance to compression therapy as reported in the literature.

Numerous review articles discussed randomised controlled trial (RCT) results that demonstrated the effectiveness of different compression therapy systems on VLU healing and its long-term benefit as an intervention for preventing recurrence1–3,6,13,15,16. Armstrong and Meyr6 report healing rates of more than 97%, Stanton et al.11 93% at 7 months, and Moffatt et al.16 97% at 40 months as compared to 55% in the control group.

Determinant factors contributing to non-compliance

Thematic analysis of the findings in Table 1 was undertaken, and five determinant factors contributing to patients’ non-compliance to compression therapy were identified and discussed. Pain1–4,7,8,11,13,14,16–18 and discomfort1–4,6,7,9,13,15–19 were key factors that emerged, followed by psychosocial issues1–4,7-9,11,13–18, knowledge deficit1,3,7,8,11,13,14,16,17, physical limitations1,4–9,13,16–18, and financial issues1–3,5,9,16,18.

Pain and discomfort

Pain and discomfort have been revealed as patients’ most important symptom and is identified as likely the primary reason why they seek HCP help4,7,13. For example, they expressed itchiness, irritation and sweating as a result of heat and skin problems2,6,13,15–17,19. Consequently, if these are poorly managed patients, they may lose confidence and belief in the HCP which may contribute to non-compliance7,11. For example, one known aspect of compression therapy is that, initially, it can be painful, hence, if this fact is not clearly explained to patients, it may become a reason for them to be non-adherent to or discontinue treatment7.

Past RCTs concluded that compliance is greater with lower degrees of compression, therefore, this may be a logical approach for HCPs to consider8,9,17. Moreover, HCPs can alleviate some of these symptoms by undertaking holistic assessments when selecting compression therapy, ensuring good fit and effective pain management, prescribing an easy application aid, and recommending a comprehensive skin care regime1,5,19. For example, results from an RCT with 47 participants undertaken to address the discomfort of compression stockings concluded that the Jobst Opaque SoftFit compression stockings which contain a silicone yarn at the top band were more comfortable and yield better compliance compared with the traditional stocking that has a slightly higher pressure top band19.

Overall, in order to establish effective therapeutic relationships and trust, HCPs need to listen to the patients’ experiences, assess the causes and impact of pain, and include the multidisciplinary team when managing related complications like chronic back pain4,8. Concurrently, inclusion of this may help in achieving treatment outcomes as well as improving patients’ quality of life and reducing healthcare costs11,19.

Psychosocial issues

Poor relationships with HCPs were frequently reported as one of the main contributing factors to non-concordance to compression therapy1,4,7,8,13,14,16. To strengthen this relationship, there is a need for honest and open discussion about the nature of VLUs, their recurrence, and compliance issues between the HCP and the patient7,14. Likewise, valuing patients’ individuality and social support when prescribing compression therapy is equally important14. Other reasons revealed in this category include patients’ health beliefs like the acceptance of ulcers as part of their life1,2,7,11,13–15, the social impact of treatment, aesthetic and cosmetic issues1,7,13,15–17, mental health issues1,4,7,9,13,18, and lack of motivation and trust with HCPs linked to recurrence issues and long-term therapy1,4,7,13.

Similarly, the health belief model suggests that lack of belief in treatment can diminish patients’ motivation to commit to it and, as cited, patients therefore do not believe in compression therapy efficacy1,2,8,11,13,14. Equally, high recurrence rates contribute to this belief, as well as depression1,7,9 and negative past experience1,4,7,11. Subsequently, patients can perceive this as treatment failure1,2,13–15, and hence this explains the low compliance rates. Social issues such as impact on body image1,7,15-17, inability to wear clothing of choice1,13,16, inability to shower as desired1,16, and restrictions on social activities causing social isolation1,9,11,13,16 were also reported.

Collectively, all of these factors negatively reduce the acceptance level of compression therapy. Bainbridge7 suggests that having a non-judgemental relationship with HCPs is highly regarded with patients and, subsequently, it dispels any trust issues and positively increases concordance to treatment. Likewise, Anderson4 suggests that verbal encouragement, empathy and constructive positive feedback from HCPs and significant others can increase compliance. The key is for HCPs to focus on finding the cause of the non-concordance behaviour rather than assuming that it is a ‘social ulcer’ phenomenon11,13.

Knowledge deficit

Clinical experience has demonstrated that knowledge is power and, when it is lacking, misperception sets in. As such, lack of knowledge and understanding of underlying disease1,3,5,7,8,13,14,16 or rationale behind compression therapy1,16 were reasons cited for non-concordance. Contributing factors included receiving conflicting advice from HCPs1,11,13,14, poor communication with HCPs1,7,11,13,15, and memory issues1,4,13,17. Since patients’ knowledge and understanding of disease and treatment has been proven to influence concordance to treatment interventions, without adequate information they therefore cannot make informed choices7,14. Likewise, Balcombe et al.5 concludes that, when equipped with relevant knowledge, patients can be self-sufficient with compression garments’ application and require less reliance on HCPs and carers. On the other hand, patients rely on the HCPs for information and, if the HCP is inexperienced11 or has poor communication skills7,13, this lack of skill and knowledge consequently increases the non-adherent behaviour.

One qualitative study to validate the impact of an e-learning package on recurrence prevention with 12 participants aged between 51–90 years concluded that all but one participant continued to wear compression long-term for recurrence prevention18. These findings support the known fact that the provision of evidence-based programs like the Leg Ulcer Prevention Programme (LUPP) promotes life-long healthy behaviour change, especially when introduced early18. Similarly, Bainbridge7 suggests that written instructions with verbal reinforcement are more effective than the former alone. So, to enhance patients’ commitment to care, effective communication methods need to be established so that patients can receive clear, consistent information from motivated, skilled and supportive HCPs who take into consideration their individuality, culture, and cognitive and health literacy7,14,16.

Physical limitations

Inability or difficulties in applying and removing hosiery1,4–6,8,9,13,16–18 and mobility and dexterity issues1,4,5 were the main barriers to compliance cited by patients. Applying a compression garment requires the ability to bend and good dexterity to pull it up. Hence, restrictions as a result of obesity may not be apparent to HCPs and, likewise, patients may not be willing to disclose the real reason why they cannot self-care nor adhere to prescribed treatment4,5. Often, VLU patients have co-morbidities such as osteoarthritis, poor eyesight and chronic back problems that may already be impacting on their abilities to self-care and, as such, the addition of managing compression therapy may be too overwhelming for them to comprehend3,4,7,14.

Ongoing therapeutic relationships with patients will have good treatment outcomes, hence HCPs need to undertake a holistic, individualised approach to care and utilise social support and the multidisciplinary team where possible in managing barriers related to cognitive and dexterity issues1,4,7,15. Moreover, involving patients in decision-making regarding their treatment options and ensuring that they can manage their own therapy as much as possible – taking into consideration the use of different application aids available – has been shown to improve concordance4,5. Likewise, Balcombe et al.5 believe that the use of foot slips and frames eases the application and removal of compression stockings and helps to overcome barriers such as dexterity and inability to reach forward to the feet. To alleviate these limitations, HCPs need to either prescribe compression hosiery and a suitable aid together, or consider other alternative types of compression like altered compression design or adjustable compression wrap in cases where hosiery is unsuitable and, if possible, arrange a trial of available samples of aids beforehand5.

Financial issues

Since VLUs take weeks or months to heal and often recur post-healing, their treatment distresses patients, affects their quality of life, and is costly2,3,17. Other reasons for non-compliance include work issues, the high cost of compression therapy and essential accessories, and the long duration of treatment1,2,5,9,13,15–18. Although evidence suggests that the use of aids eases the application and removal of compression stockings and promotes self-care, cost remains a barrier5,8. Kapp and Miller18 conducted a qualitative research with 12 participants aged between 51–90 years and concluded that, among other cited reasons of non-adherence, cost was the most cited, with participants stating that they could not replace nor afford an extra pair.

Armstrong and Meyr6 report that in the United States the cost of compression hosiery of at least 30–40mmHg is covered by insurance but, unfortunately, in most other countries, the patient, plus or minus the healthcare services, covers the cost. A survey conducted in Poland to evaluate non-compliance with compression stockings revealed that 37.9% of the 16,770 participants discontinued treatment due to economic reasons15. Again, multidisciplinary involvement like social workers may be beneficial to assist patients facing this barrier. Overall, HCPs need to discuss with patients associated cost and long-term benefits when prescribing compression treatments and, if concerns are raised, they need to consider other alternative ways of lessening this barrier like the provision of treatment in clinics rather than in-home.

Conclusion

Despite the identified reasons and contributing factors that contribute to patients’ non-compliance or concordance with compression therapy, it still remains the cornerstone of VLU prevention, treatment and recurrence when adhered to1–7. The analysis of the contributing factors established that compliance is a shared responsibility between the patient, HCPs and policymakers. Furthermore, this review has supported the known fact that holistic patient assessment, support and effective communication skills by HCPs forms the basis of therapeutic relationships. Concurrently, maintaining this therapeutic rapport provides a platform for HCPs to identify and understand the key experiences that lead to patients’ non-compliance and helps them implement tailored intervention strategies that can increase their commitment to care. Similarly, an honest collaboration of care – such as making patients aware of potential adverse effects like pain, discomfort and cost issues – is also essential. Therefore, in order to maximise benefits with compression therapy, innovation in treatment methods as well as future studies are needed to identify predictors of non-compliance behaviours and to assess the strategies that can be used to improve patients’ compliance3,17,19.

Conflict of interest

Nil to report.

Funding

The author received no funding for this study.

Author(s)

Francisca Chitambira

RN, MClin Nurs (Comm Hlth Nurs), STN

Northern Sydney Home Nursing Service,

Northern Sydney Local Health District,

St Leonards, NSW

Email fran.7@optusnet.com.au

References

- Boxall S, Carville K, Leslie G, Jansen S. Compression bandaging: identification of factors contributing to non-concordance. Wound Pract & Res 2019;27(1):6–20.

- Latz CA, Brown KR, Bush RL. Compression therapies for chronic venous leg ulcers: interventions and adherence. Chronic Wound Care Res 2015;2:11–21.

- Weller CD, Buchbinder R, Johnston RV. Interventions for helping people adhere to compression treatments for venous leg ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2016(3)(CD008378):1–45.

- Anderson I. Optimising concordance with compression hosiery in the community setting. Br J Community Nurs 2015;20(2):67–8, 70, 2.

- Balcombe L, Miller C, McGuiness W. Approaches to the application and removal of compression therapy: a literature review. Br J Community Nurs 2017;22(10):S6–S14.

- Armstrong DG, Meyr AJ. Compression therapy for the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. In: Mills JL, Eidt JF, editors. Basic principles of wound management. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc; 2019 [cited 2019 May 2]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/basic-principles-of-wound-management?search=basic%20principles&source=search_result&selectedTitle=4~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=4.

- Bainbridge P. Why don’t patients adhere to compression therapy? Br J Community Nurs 2013;Suppl:S35–6, S8–40.

- Brown A. Self-care strategies to prevent venous leg ulceration recurrence. J Practice Nurs 2018;29(4):152–8.

- Finlayson KJ, Edwards HE, Courtney MD. Venous leg ulcer recurrence: deciphering long-term patient adherence to preventive treatments and activities. Wound Pract & Res 2014;22(2):91–7.

- Haesler E, Frescos N, Rayner R. The fundamental goal of wound prevention: recent best evidence. Wound Pract & Res 2018(1):14.

- Stanton J, Hickman A, Rouncivell D, Collins F, Gray D. Promoting patient concordance to support rapid leg ulcer healing. J Community Nurs 2016;30(6):28–35.

- Coghlan N, Copley J, Aplin T, Strong J. Patient experience of wearing compression garments post burn injury: a review of the literature. J Burn Care Res 2017;38(4):260–9.

- Van Hecke A, Grypdonck M, Defloor T. A review of why patients with leg ulcers do not adhere to treatment. J Clin Nurs 2009;18(3):337–49.

- Brown A. Evaluating the reasons underlying treatment nonadherence in VLU patients: introducing the VeLUSET Part 1 of 2. J Wound Care 2014;23(1):37.

- Ziaja D, Kocelak P, Chudek J, Ziaja K. Compliance with compression stockings in patients with chronic venous disorders. Phlebology 2011;26:353–60.

- Moffatt C, Kommala D, Dourdin N, Choe Y. Venous leg ulcers: patient concordance with compression therapy and its impact on healing and prevention of recurrence. Int Wound J 2009;6(5):386–93.

- Kankam HKN, Lim CS, Fiorentino F, Davies AH, Gohel MS. A summation analysis of compliance and complications of compression hosiery for patients with chronic venous disease or post-thrombotic syndrome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2018;55(3):406–16.

- Kapp S, Miller C. The experience of self-management following venous leg ulcer healing. J Clin Nurs 2015;24(9–10):1300–9.

- Munter C. Effect of a new compression garment on adherence: results of a patient satisfaction survey. Br J Nurs 2015;24:S44–S9.