Volume 39 Number 2

Avoidance of lower limb amputation from a diabetic foot ulcer: The importance of multidisciplinary practice and patient collaboration

Margaret Mungai and Emmy Sirmah

Keywords Diabetes, diabetic foot ulcer, debridement, nursing interventions, patient education, multidisciplinary collaboration

For referencing Mungai M and Sirmah E. Avoidance of lower limb amputation from a diabetic foot ulcer: The importance of multidisciplinary practice and patient collaboration. WCET® Journal 2019; 39(2):19–27

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.2.19-27

Abstract

This article explores wound care nursing interventions and inter-professional collaboration for a patient referred with a stage 3 diabetic foot ulcer (DFU). To the patient’s distress, he had been informed that he may require an amputation due to the severity of his DFUs. On initial presentation, the patient was symptomatic for peripheral neuropathy, infection and hyperglycaemia. The left lower limb was oedematous and there was a DFU at the metatarso-phalangeal joint of the big toe on his left foot secondary to haemorrhagic callus. Progressive healing of the DFU was realised over time by repetitive debridement; incision and drainage of the DFUs; antibiotic therapy; appropriate footwear; dietary instructions; control of the blood sugar levels (BSLs); and patient and family education.

Wound care nursing interventions were applied in conjunction with medical management of the DFUs. The DFUs were managed using a locally made, two-part zinc oxide gauze dressing known as the Unna boot. A family member was instructed how to continue applying the dressings at home in between clinic visits. Complete wound healing was eventually achieved within four months, thus avoiding the need for amputation.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) will be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030 as predicted by the World Health Organization1. About 80% of deaths due to DM occur in low- to medium-income countries2,3.

Foot ulceration is the main complication affecting lower limb extremities in patients with DM, the management of which is costly. The global prevalence of risk of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) in patients with DM is 40–70%4. The prevalence of DM in Kenya ranges between 2.2%5 and 2.4%6.

The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) defines a DFU as an, “Infection, ulceration or destruction of tissues of the foot associated with neuropathy and/or peripheral artery disease in the lower extremity of a person with [a history of] diabetes mellitus”7. Within a cohort of 1788 patients with DM at Kenyatta National Hospital, the prevalence of DFUs was 4.6% (n=84)8.

DFU development is associated with multiple risk factors, which can be grouped into systemic factors and local factors. The primary systemic factors are diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) and peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Other systemic factors include: peripheral vascular disease, chronic renal disease, male gender, abnormal glycated haemoglobin level (HbA1c), more than 10 years' duration with DM, advancing age, a high BMI, obesity and retinopathy. Local factors include foot deformity, high plantar pressures and haemorrhagic callus formation, infection, shear, pressure and stress on the lower extremities due to poorly fitting footwear, other external trauma; and, suboptimal self-care habits8-11.

The majority of DFUs develop from minor trauma in the presence of sensory neuropathy or loss of protective sensation, which is associated with poor blood supply due to micro-vascular disease from DM12. Foot infection in patients with DM is common, with more than 50% of patients with DFUs having an infected ulcer13. These infections can range from simple infections, cellulitis and abscess formation to more severe infections such as pyomyositis, osteomyelitis and gangrene14,15.

In addition to the classic signs of infection (heat, pain, redness, swelling) DFUs exhibit signs of inflammation or purulence. Other signs of infection in DFUs are malodour, high temperature within 4 cm of the ulcer margin, non-purulent or purulent secretions, friable or discoloured granulation tissue, undermining of wound edges, continuous wound breakdown, and evidence of poor wound healing10,16-18. Patients with DFUs are at increased risk of infection if they have experienced one or more of the following: a traumatic wound, an ulcer for more than 30 days, a history of walking barefoot, a wound that probes to bone, previous lower extremity amputation and loss of protective sensation16.

The Wagner Diabetic Foot Ulcer Classification System is commonly used to classify DFUs by grading ulcer depth and presence of infection from 0 to 5. DFUs that have abscesses, joint sepsis or osteomyelitis are usually deep ulcers that are grade 3 within the Wagner Diabetic Foot Ulcer Classification System16,19.

The current approach in the management of patients with DM focuses heavily on the prevention of DFU formation and/or recurrence3 and lower extremity amputations (LEAs). Preventive multidisciplinary care in DFU aimed at conservative treatment is less costly compared to amputation costs incurred by patients and health services20. In addition, health care providers should aim to improve the health-related quality of life of patients with DFUs, which is low in this patient cohort21.

Case Study

Patient overview and presenting complaint

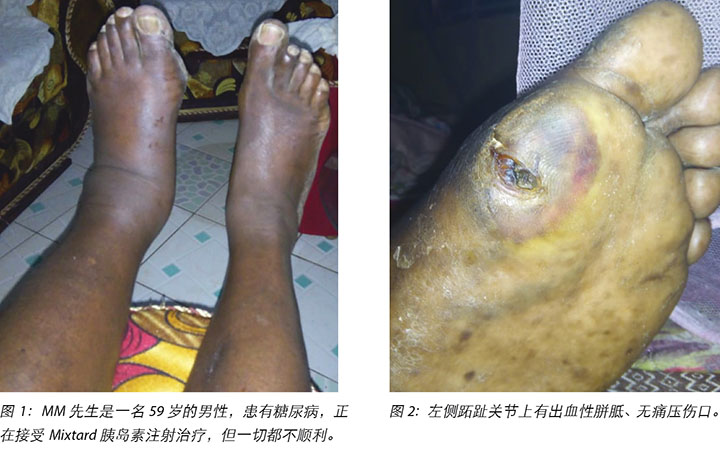

Mr MM, a 59-year-old male, was referred from the company clinic to our hospital with uncontrolled DM, gradual loss of vision and a haemorrhagic callus on his left big toe.

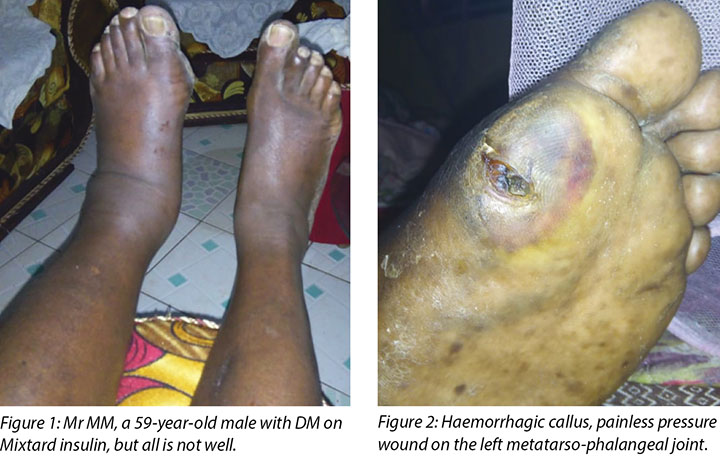

On presentation at the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital DM clinic, Mr MM’s left leg was oedematous (Figure 1) and the haemorrhagic callus (Figure 2) at the metatarso-phalangeal joint of the big toe was clearly evident. His medical history indicated he had had DM since 1996, developed hypertension in 2000 and was treated for cellulitis in his right big toe in August 2017 that healed well. His medications included Mixtard insulin 20 international units in the morning and 10 international units in the evening. Mr MM had been unable to control his blood sugar levels (BSLs) and his fasting blood sugar now ranged between 20 and 22 mmol.

Mr MM had not noticed anything untoward with his foot or toe until the area became very painful and he asked his son to check his feet. He thought the problem was due to poorly fitting shoes, which he had used for some time. He reported no history of trauma; however, he had little sensation in the foot area. He had little appetite and had lost weight from 150 kg to 140 kg. His eyesight had deteriorated to the extent that he could no longer read the daily newspaper.

On his initial visit to the wound care clinic, he was brought in a wheelchair and looked depressed. He stated that if he had to have an amputation, he would not be able to use crutches due to his poor eyesight and heavier body weight.

Interventions and wound management plan

Foot assessment

On palpation, both dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were absent on the left leg, but were well palpable on the right leg.

His ABI was at 0.92 with an ankle systolic pressure of 168 mmHg and an arm systolic pressure of 154 mmHg. Self-foot care assessment indicated that Mr MM required assistance due to body weakness, poor vision and not reaching his feet. Health information on the effects of DM on the foot among other body parts was provided to the son and brother-in-law, who accompanied him including inspection under light for any abnormality/deformities.

Loss of sensations was detected by touching his foot at different parts with his eyes closed because neither the Semmes Weinstein monofilaments nor the Doppler machine are available at the wound care clinic. Mr MM's capillary refilling time on his toes was 4–5 seconds; however, there was no associated sensation experienced by Mr MM when this assessment was undertaken.

Wound debridement

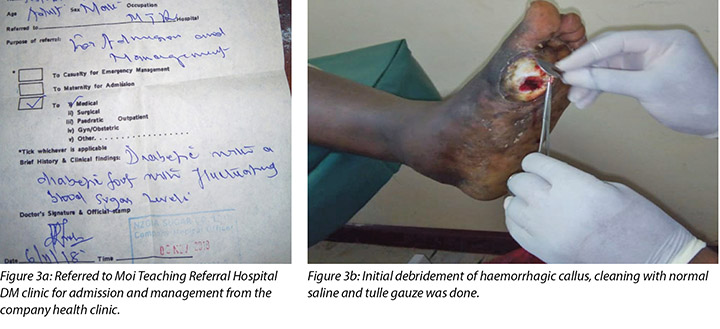

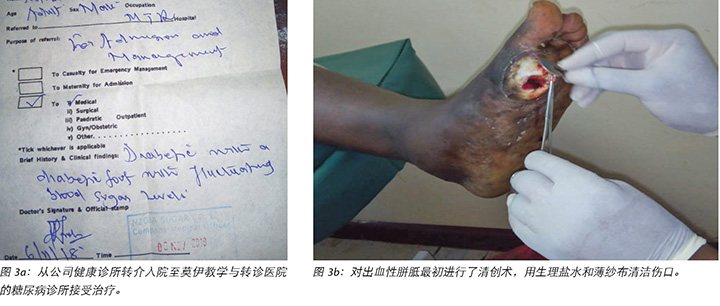

During Mr MM’s initial visit to the DM clinic the callus beneath his left metatarso-phalangeal joint of the big toe was debrided. Following this initial debridement of the callus the wound was classified as a stage 2 DFU using the Wagner Diabetic Foot Ulcer Grade Classification System (Figure 3).

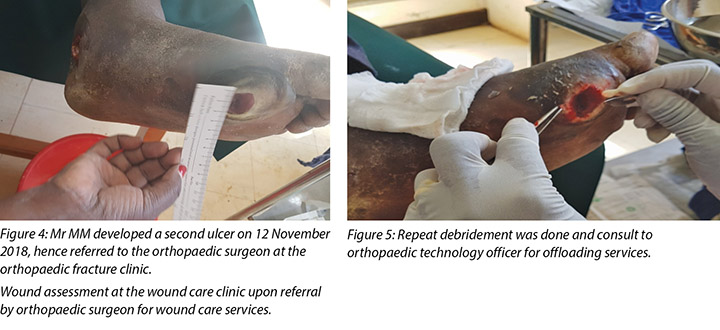

At the first visit in the wound care clinic on 12 November 2018, wound assessment, cleaning with warm water, repeat debridement and application of the locally produced two-part zinc oxide Unna boot was done (Figures 4, 5 and 6) and Mr MM was advised to come back in two days' time.

Mr MM's foot was noted to be very warm with localised swelling and pitting oedema on the second visit on 14 November 2018 (Figure 7) when Mr MM was due for the second application of the Unna boot, which we had scheduled on alternate days after the first application. The clinical diagnosis of pyomyositis was arrived at based on the signs and symptoms present in the foot, which were the presence of an abscess and localised oedema. The affected foot felt hot on palpation, with a body temperature of 37.8°C by use of the clinic infrared thermometer. Mr MM could slightly move all toes of the left foot including a small range of dorsiflexion and plantar flexion upon instructions.

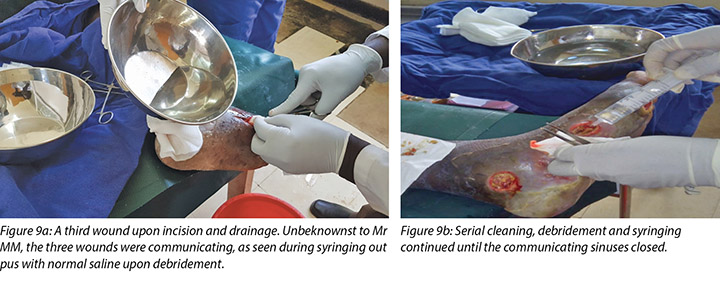

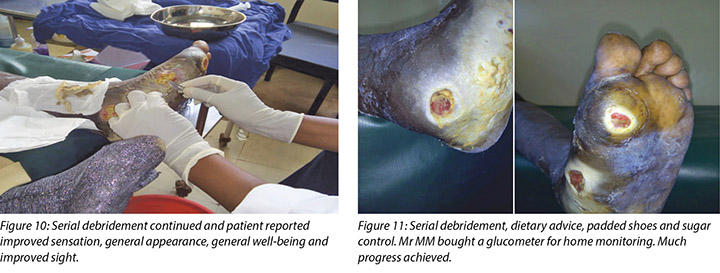

Local incision and drainage of the pyomyositis as well as sharp debridement of necrotic tissue and residual periwound callus was undertaken within the clinic. Antibiotic therapy was commenced with a course of Clindamycin to combat the infection associated with the pyomyositis. This was given at 1 gram orally every 8 hours for 7 days. Unfortunately, a pus swab for culture and sensitivity to identify the specific causative agent was unable to be obtained at the time (Figures 8 –11). Mr MM's DFU was now re-classified to stage 3 on the Wagner Diabetic Foot Ulcer Classification, having developed into a deep ulcer with abscess formation.

Mr MM noticed the first wound, which was painless with haemorrhagic callus (Figure 2), on 5 November 2018; hence he visited the company health facility on 6 November 2018. He was advised to come to our hospital for further management, but only arrived at the DM clinic on 10 November 2018. Debridement of the haemorrhagic callus and grading of the first wound was done (Figure 3a and b).

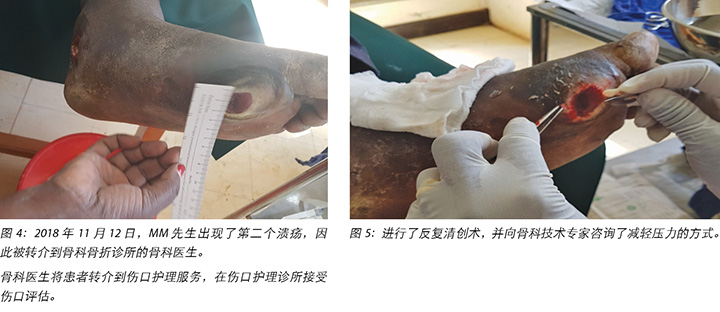

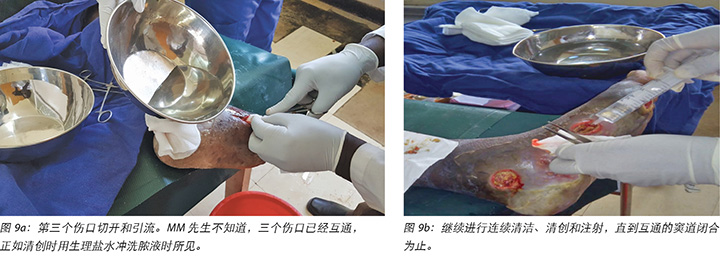

The second wound was noted on 12 November 2018 when he went for review at the DM clinic as advised and this was when he was referred to the orthopaedic surgeon at the orthopaedic clinic for further evaluation. It was at this point the orthopaedic surgeon after his review advised the patient to come to our wound care clinic for wound care services.

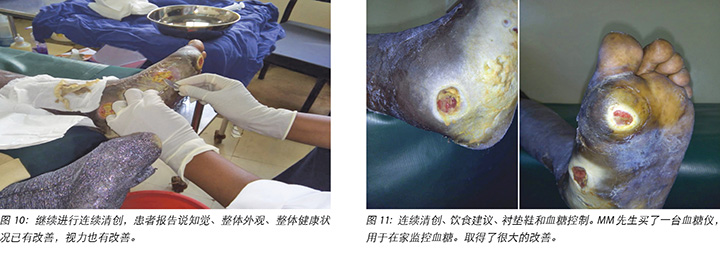

The third wound developed on 14 November 2018 upon incision and drainage of the pus due to pyomyocitis, which was noted on examination of the wound before cleaning (Figures 7 and 8). The three wounds were noted to be communicating when syringing out pus was being carried out upon debridement (Figure 9).

Wound management

At the DM clinic, the wound had initially been cleaned with normal saline, debrided using a surgical blade and artery forceps and dressed with SufraTulle and gauze dressing.

At the wound care clinic, wound cleaning was done with warm tap water, serial sharp debridement using a surgical blade and artery/dissecting forceps was done under no anaesthesia/analgesics as Mr MM was not feeling pain at all and the application of a locally produced two-part zinc oxide dressing was also done.

As Mr MM had a degree of left lower limb oedema (Figure 1) that indicated circulatory stasis this necessitated the use of slight compression during the initial period of Unna boot dressing application. Compression was eventually stopped with consequent dressing once all oedema subsided.

At each subsequent dressing change the wound was debrided as required and application of a locally manufactured zinc oxide dressing (Unna boot) done. The first Unna boot was applied on 12 November 2018 after repeat debridement (Figures 5 and 6). The second dressing change with the Unna boot was carried out on 14 November 2018 after incision and drainage. The third Unna boot dressing change was on 16 November 2018 and thereafter continued every Monday and Friday as an outpatient for a period of two months. The frequency of debridement with debridement was adjusted to every Monday and for the whole of the third month as we taught the son how to undertake the dressing changes at home. He would thereafter change the dressing on a Monday then come to the clinic fortnightly for us to assess the patient and the wound as well as evaluate his dressing change skills. This regime was continued with the locally produced zinc oxide dressing — Unna boot — as the primary dressing at the clinic and at home until complete healing of the three wounds was achieved on 17 March 2019 after a period of four months.

Multidisciplinary approach

The management of Mr MM's DFUs was complex, requiring a multidisciplinary team approach to guide his care.

Orthopaedic surgeon

Mr MM's first visit and debridement of haemorrhagic callus was on 10 November 2018. The second ulcer developed or was noted on 12 November 2018 when Mr MM came to the DM clinic for the second time after which he was referred to the orthopaedic surgeon. The orthopaedic surgeon evaluated the foot pulses at the dorsalis pedis, posterior/anterior tibial and ordered foot x-rays. Upon reviewing the x-rays report, he referred the patient for wound care services since there was no bone involvement.

Pyomyositis was later diagnosed on 14 November 2018 which led to the development of the third wound upon incision and drainage by the registered clinical officer orthopaedics (Figures 8 & 9a). It was not possible to involve the orthopaedic surgeon at the time, but the clinical officer also specialised in orthopaedics and worked closely with the orthopaedic surgeon completed the incision and drainage as well as prescribing the oral Clindamycin 1 g eight hourly for 7 days.

Orthopaedic technologist: foot and pressure offloading

A key intervention in the management of Mr MM's DFUs was offloading of pressure on his affected foot. He was reviewed by an orthopaedic technologist and was advised about the benefits of offloading as well as changes required to his shoes. In accordance with the advice form the orthopaedic technologist, his shoes were changed to open padded shoes rather than enclosed shoes.

Dietitian

A dietitian, diabetes educator and nursing staff provided advice on dietary requirements, control of BSLs and general health education inclusive of daily foot examination and care to both Mr MM and the relatives.

Psychosocial support

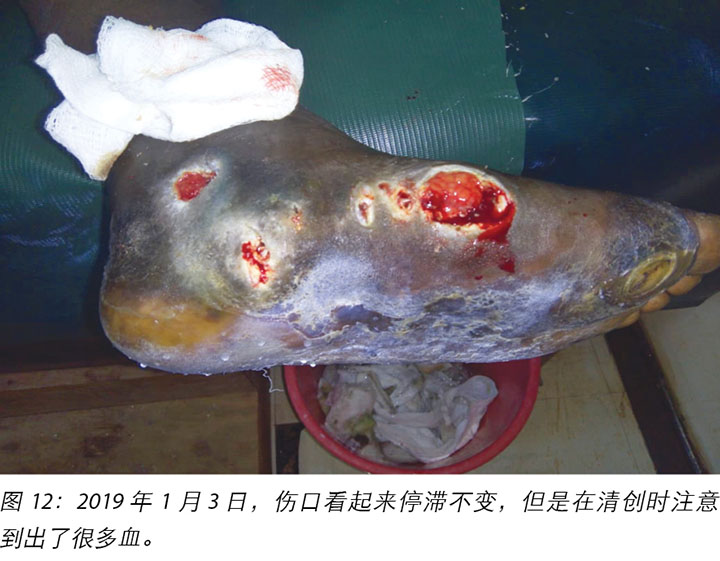

At times, the DFUs showed signs of stagnation in wound healing where there were no changes to the status of the wound (Figure 12). In these instances, counselling and psychological support was offered to Mr MM that this often occurred with wounds of this nature. He was encouraged to continue with all aspects of his treatment regimes.

Discharge planning, community care and long-term follow-up

A family therapy session was undertaken with Mr MM, Mr MM’s wife and son on home-based wound care, dietary regime, foot examination and BSL monitoring. The importance of Mr MM actively participating in his self-care where possible was stressed to avoid deterioration and/or recurrence of his DFUs and improve his overall well-being.

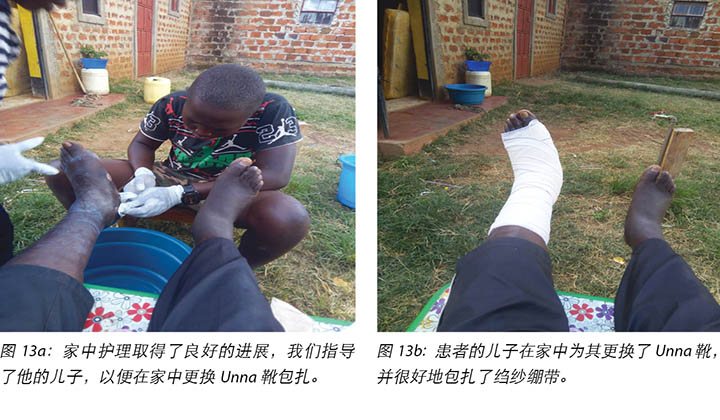

Mr MM's wife and son were taught how to examine the wound, check for pre-ulcerative signs on the foot and apply the Unna boot wound dressing (Figure 13a and 13b). Education was also provided on how to recognise ill-fitting or inadequate footwear, given that the wearing of adequate footwear is a key factor in preventing DFU recurrence.

Mr MM purchased a glucometer for home monitoring of his fasting BSLs, which had stabilised at 6–8 mmol/L.

Discussion

Most patients with DM will suffer from a DFU at one time during their lifetime22. DFUs are a cause of high morbidity and mortality that also incur substantial financial costs23.

Diabetic neuropathy causes defects in pain sensation from the loss of sensory perception in the foot; hence the lack of early care-seeking behaviour by patients with diabetic neuropathy. Insensate feet are susceptible to increased shear and pressure on the plantar surfaces or soles of the foot and consequently increased injury24. Motor neuropathy causes wasting of intrinsic foot muscles while autonomic neuropathy affects sweating with dryness and scaling of the feet. These phenomena lead to ulcer development, foot deformity and defects in joint mobility.

The management of patients with DFUs is, unfortunately, often implemented by health care providers whose existing knowledge and insight into causative factors, diagnosis and management of DFUs is suboptimal. Even in developed countries, diabetes specialists refer patients to community nursing services where the nurses lack the requisite knowledge and clinical competency to manage such wounds proficiently25.As a multifaceted problem, evidence-based protocols, strengthening of multidisciplinary team functioning and specific health care facility clinical regimens achieve better outcomes. Nurse-based foot care programs have been found to be effective in the prevention of DFUs26.

Nurses are responsible for the management of DFUs referred for wound care services at the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Kenya. The hospital management has enabled one orthopaedic surgeon, two nurses, one registered clinical officer, one physiotherapist and one occupational therapist to undertake the IIWCC wound care course at Stellenbosch University RSA from 2010 to date.

Diabetes Kenya, formerly called Kenya Diabetes Association, works closely with the International Diabetes Federation to enable training of multidisciplinary diabetes educators in our hospital who are currently six in number (three nurses, one registered clinical officer and two physicians). These teams (wound/diabetes) organise in-house training for other staff in the hospital as well as attending national conferences and seminars when possible to enhance their knowledge and practice geared towards developing an enthusiastic wound community of practice at the hospital.

Mr MM was referred from a company clinic more than 100 kilometres away due to lack of health care providers who felt comfortable in managing his DFU.

The management of DFUs is often complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach to achieve optimal patient outcomes. The multidisciplinary team can: reduce the incidence of DFU complications and associated severity of those complications; reduce amputations; improve a patient’s quality of life; and, increase their life expectancy22. In this case, the collective clinical input from the orthopaedic surgeon, the orthopaedic technologist, dietitian, counsellor and nursing staff in conjunction with Mr MM’s family were able to salvage Mr MM’s foot, facilitate wound healing and avoid amputation of part or all of his foot. Key interventions in the management of Mr MM’s wounds were wound debridement, local wound care, pressure offloading and stabilisation of Mr MM’s BSLs, patient education and psychosocial support.

Wound debridement of devitalised, unhealthy tissue to expose healthy, bleeding tissue allows for greater visualisation of the extent of the ulcer and the presence of indwelling abscesses or sinuses27,28. Further, it decreases the risk of spreading infection, and reduces periwound pressure from the presence of callus, all of which enhance normal wound contraction and healing29.In patients with DFUs, it is estimated that 20% of those with moderate to severe infections require an amputation at some level30,31. Conservative sharp wound debridement was, therefore, undertaken at every dressing change.

The wound care regimen consisted of cleaning with warm tap water, sharp debridement by surgical blade and artery/dissecting forceps, syringing with normal saline using a 20 cc syringe and application of the primary zinc oxide dressing with a 6-inch crêpe bandage for the outer dressing.

The frequency of the serial debridement and dressing change was initially on alternate days for the first week due to the infection, followed by every Monday and Friday (twice a week) and thereafter every Monday (once a week) but the son would do it at home for one week then come to the clinic fortnightly during the fourth month of wound care.

The application of a locally manufactured zinc oxide dressing (Unna boot) alongside key basic wound care principles was used for a period of four months to facilitate wound healing. Zinc oxide within the dressing is thought to decrease inflammation, protect the surrounding skin, enhance re-epithelisation and reduce oedema. The Unna boot zinc oxide bandage dries to form a warm, snug boot around the lower limb that supports venous return by providing high pressure with muscular contraction when the patient walks but little pressure on resting, which aids healing of the ulcer.

While patients are accepting of this dressing it is imperative staff are trained in the correct foot and wound assessment and application of this dressing to avoid constriction of the limb and arterial occlusion in the presence of neuropathy32-34. It was important to assess the vascular flow along the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries29 before applying any compression to a lower limb. Mr MM reported he felt more secure and confident with his left leg upon application of the Unna boot.

Ideally, management of DFUs requires the person to be non-weight bearing on the affected area to enhance healing. There are a variety of strategies to off-load the pressure from DFUs, including off-the-shelf orthotic footwear, customised footwear including insoles, contact casting and external padding that can be moulded to suit the contours of the foot. The type of offloading used depends on patient and environmental factors, access to and cost of orthotic footwear35,36. Taking these factors into consideration and to facilitate off-loading of Mr MM’s DFU, the orthopaedic technologist advised the use of open, padded shoes. The orthopaedic technologist did not place any additional padding on Mr MM's foot, but recommended larger padded, open shoes to alleviate pressure on the wounds. He advised that the shoes Mr MM was wearing were tight with non-padded straps and buckles that led to the development of the second wound.

DFUs seriously affect health-related quality of life due to reduced accomplishment of physical activities of daily living that affects psychological and social well-being. This can lead to social isolation in general, tension that adversely affects family relationships, financial hardship from loss of productivity or job loss and emotional stress and depression within the person with the DFU37. These factors, however, are influenced by an individual patient’s clinical characteristics, including social demographic and environmental factors38.

Self-care is a primary factor in attaining optimal health and management of DM. This can be effectively achieved by the use of nursing theories and models such as Orem’s Self-care Model38. Borji et al. state that, “Self-care is considered as an important and valuable principle because it emphasizes the active role of people in their own healthcare, not the passive. Further, … Self-care behaviour is affected by the total skills and knowledge that a person (or relatives) has and uses for his practical efforts”, to alter those factors that affect a person’s health and well-being39.

Consequently, nurses play a key role in patient and family education by assisting patients and their families to understand the underlying causes of DM and DFUs. This knowledge allows patients and their families to play an active role in problem solving and decision making with respect to their clinical and psychosocial care40,41.

Educating Mr MM and his family about his diet and the importance of diet and exercise in assisting to stabilise his DM and BSLs was one example of self-care where Mr MM was able to be an active participant in his care.

Nursing staff also provided clinical education to Mr MM’s wife and son on how to manage Mr MM’s wounds and foot care at home. This included the application of the Unna boot dressing (Figures 13a and 13b) at home.

As there is a high possibility of developing a new ulcer after successful treatment of a DFU on the same site or on a different site of the same limb or the contra-lateral limb42, following up Mr MM as an outpatient has been maintained to ensure his DFU does not re-occur, which is very important.

Variants of diabetic foot complications are more prevalent now. This is due to the increased global incidence of DM as well as the longer life expectancy realised with better management. This requires a paradigm shift for DM care providers to focus on current and emerging trends for prevention, diagnosis and management of DFUs among other diabetic foot complications27. There is the need, therefore, to direct DM education and management of diabetic wounds towards health professionals as much as the patients because health care providers and health professionals can contribute to development as well as deterioration of DFUs43. The increase in DM and DFUs globally requires the attention of all health care professionals and, in particular, the adoption of effective multidisciplinary team approach to diagnosis and management, inclusive of nursing and patient participation44.

Conclusion

The incidence of DM and DFUs is escalating around the world. Not all health care providers and health professionals are sufficiently educated to assess and manage DFUs. The referral of patients with DFUs to health care facilities with expertise in the assessment and management of DFUs is critical to successful patient and health provider outcomes.

Referral of Mr MM to our hospital, where a multidisciplinary approach to the management of his DFU was adopted, facilitated wound healing, limb salvage and prevention of an unnecessary amputation of his lower left leg, which undoubtedly improved his overall quality of life.

Nurses with expertise in wound management applied self-care theory to educate Mr MM and his family regarding his DM, BSL control and monitoring, care of his wounds and care of his feet within the clinic and community settings.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr Aileen Chang of the University of California and a visiting lecturer at Moi University/Ampath Eldoret, for her guidance in writing this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

避免由糖尿病足溃疡引起下肢截肢:多学科实践和患者合作的重要性

Margaret Mungai and Emmy Sirmah

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.2.19-27

摘要

本文针对一名转介的3期糖尿病足溃疡(DFU)患者,探讨伤口护理干预措施和专业间的合作。对患者来说痛苦的是,由于他的DFU的严重程度,他被告知可能需要截肢。初诊发现,患者呈现周围神经病变、感染和高血糖症状。左下肢水肿,左脚大脚趾的跖趾关节出现DFU,继发于出血性胼胝。通过反复清创、DFU切开和引流、抗生素治疗、穿着合适的鞋子、改善饮食、控制血糖水平(BSL),以及对患者和其家属进行教育指导后,DFU随时间的推移逐步愈合。

治疗采用伤口护理干预措施与DFU医疗管理相结合。使用当地生产的两部分氧化锌纱布包扎(称为Unna靴)方法治疗DFU。指导一名家庭成员在不前往诊所就诊的期间继续在家中包扎敷料。伤口最终在四个月内完全愈合,从而避免了截肢。

前言

世界卫生组织预测,到2030年,糖尿病(DM)将成为第七大死亡原因1。在糖尿病导致的死亡中,约80%发生在低收入和中等收入国家2,3。

足部溃疡是影响糖尿病患者下肢末端的主要并发症,治疗费用昂贵。在全球范围内,糖尿病患者的糖尿病足溃疡(DFU)患病率为40-70%4。在肯尼亚,糖尿病的患病率在2.2%5和2.4%6之间。

根据国际糖尿病足工作组(IWGDF)的定义,DFU是一种“糖尿病[病史]患者的下肢末端出现的与神经病变和/或外周动脉疾病相关的足部组织感染、溃疡或破坏”7。在肯雅塔国家医院的1788例糖尿病患者中,DFU的患病率为4.6%(n = 84)8。

DFU的发生与多种风险因素有关,可分为全身因素和局部因素。主要的全身因素是糖尿病周围神经病变(DPN)和外周动脉疾病(PAD)。其他全身因素包括外周血管疾病、慢性肾病、男性、糖化血红蛋白水平异常(HbA1c),糖尿病病程超过10年、老龄、BMI(体重指数)高、肥胖和视网膜病变。局部因素包括足部畸形、足底压力大、出血性胼胝形成、感染、由于鞋子不合脚而对下肢肢端造成的剪切力、压力和应力、其他外伤;以及自我照顾习惯欠佳8-11。

大多数DFU是在存在感觉神经病变或丧失保护性感觉的情况下从轻微创伤发展而来的,这与糖尿病引起的微血管疾病所致的血液供应不足有关12。糖尿病患者的足部感染很常见,超过50%的DFU患者存在一个感染溃疡13。这些感染的范围从单纯感染、蜂窝织炎和脓肿形成,到更严重的感染,如化脓性肌炎、骨髓炎和坏疽14,15。

除了典型的感染迹象(发热、疼痛、发红、肿胀),DFU还表现出炎症或化脓迹象。DFU的其他感染迹象有恶臭、溃疡边缘4厘米内温度升高、非脓性或脓性分泌物、易碎性肉芽组织或肉芽组织变色、伤口边缘潜行、连续伤口破裂和伤口愈合不良的迹象10,16-18。如果DFU患者有以下一种或多种情况,则感染的风险增加:创伤性伤口、溃疡超过30天、赤脚行走史、伤口深至骨质、曾下肢截肢和丧失保护感16。

通常使用Wagner糖尿病足溃疡分级系统,按照溃疡深度和感染的存在从0到5对DFU进行分级。如果DFU有脓肿、关节败血症或骨髓炎,通常在Wagner糖尿病足溃疡分级系统中分为3级深部溃疡16,19。

目前的糖尿病治疗管理方法主要集中在预防DFU形成和/或复发3以及预防下肢截肢(LEA)。与截肢对患者和医疗机构所产生的费用相比,针对保守治疗DFU的预防性多学科护理成本更低20。此外,医疗机构应致力于改善DFU患者与健康相关的生活质量,因为该患者群体的生活质量较低21。

病例研究

患者概况与主诉

MM先生,是一名59岁男性,,从公司诊所转诊到我院,患有未能控制的糖尿病,逐渐丧失视力,左脚大脚趾出现出血性胼胝。

在转介至莫伊教学与转诊医院糖尿病诊所时,MM先生的左腿有水肿(图1),且大脚趾跖趾关节处的出血性胼胝(图2)清楚可见。他的病史表明,他自1996年患糖尿病,2000年患上高血压,2017年8月因右大脚趾蜂窝织炎接受治疗后痊愈。所用药物包括早上20个国际单位和晚上10个国际单位的Mixtard胰岛素。MM先生的血糖水平(BSL)一度无法控制,空腹血糖现在介于20到22 mmol之间。

MM先生先前没有注意到足部或脚趾上有任何不适,直到脚变得非常疼痛时才请他的儿子检查他的脚。他曾认为这个问题是他在一段时间内穿的鞋不合脚所致。他报告没有外伤史;然而,足部区域几乎没有感觉。他食欲较差,体重从150公斤减轻到了140公斤。他的视力恶化,已经无法阅读每日报纸。

到伤口护理诊所初诊时,他坐在轮椅上被带进来,而且看起来很沮丧。他说,因为他的视力不佳而且体重较重,如果他必须截肢,他将无法使用拐杖。

干预和伤口管理计划

足部评估

在触诊时发现,左腿足背动脉和胫后动脉没有脉搏,但是右腿脉搏良好。

他的ABI为0.92,踝关节收缩压为168 mmHg,手臂收缩压为154 mmHg。自我足部护理评估表明,MM先生需要帮助,因为他身体虚弱、视力不佳并且接触不到他的足部。我院向他的儿子和姐夫提供了糖尿病对其他身体部位的影响的相关健康信息。他的儿子和姐夫陪同他参加了检查,包括在灯光下检查是否有任何异常/畸形。

由于伤口护理诊所没有塞姆斯·韦恩斯坦单丝检测(Semmes Weinstein monofilaments)工具和多普勒机器,因此在他闭上眼睛的情况下,通过触摸他足部的不同部位检测到他已丧失感觉。MM先生脚趾上的毛细血管充盈时间为4-5秒;然而,在进行这项评估时,MM先生没有相关的感觉。

伤口清创术

在MM先生首次来到糖尿病诊所时,对其左脚大脚趾跖趾关节下方的胼胝进行了清创。对胼胝进行初步清创后,根据Wagner糖尿病足溃疡分级系统,将伤口归类为2期DFU(图3)。

2018年11月12日,MM先生首次到伤口护理诊所就诊时,进行了伤口评估,并用温水清洗伤口,对伤口重复清创,并用当地生产的两部分氧化锌Unna靴(图4、图5和图6)包扎伤口,然后建议两天后返回诊所。

MM先生于2018年11月14日第二次来到诊所接受第二次Unna靴包扎时,发现其足部温度升高、有局部肿胀和凹陷性水肿(图7),这是第一次包扎Unna靴后我们安排他隔天前来的会诊。根据足部迹象和症状,即存在脓肿和局部水肿,得出了化脓性肌炎的临床诊断。患病的足部在触诊时感觉较热,使用临床红外线温度计测量的体温为37.8°C。MM先生可以根据指示略微移动左脚的所有脚趾,包括小范围的背屈和跖屈。

在诊所内,对化脓性肌炎进行局部切开和引流,对坏死组织和创周残留胼胝进行外科器械清创。开始抗生素治疗,使用克林霉素一个疗程,以治疗与化脓性肌炎相关的感染。该抗生素每8小时口服1克,持续7天。不幸的是,当时无法获得用于培养和药敏试验的脓拭子,未能识别特定的致病菌(图8至图11)。根据Wagner糖尿病足溃疡分级系统,MM先生的DFU现在被重新归类为3级溃疡,已经发展为有脓肿形成的深部溃疡。

MM先生于2018年11月5日注意到第一个伤口,即无痛性出血性胼胝(图2);因此于2018年11月6日前往公司诊所。公司诊所建议他来我院接受进一步治疗,但于2018年11月10日才到达糖尿病诊所。对出血性胼胝进行了清创术,并对第一个伤口进行评级(图3a和图b)。

2018年11月12日,在按照建议去糖尿病诊所进行复查时,他注意到第二个伤口,这时他被转介到骨科诊所的骨科医生处,以接受进一步评估。此时骨科医生在检查后建议患者到我们的伤口护理诊所接受伤口护理服务。

2018年11月14日,在切开和引流由化脓性肌炎引起的脓液时,出现了第三个伤口,这是在清洁前检查伤口时注意到的(图7和图8)。在清创过程中抽出脓液时,发现三个伤口互通(图9)。

伤口管理

在该糖尿病诊所,最初用生理盐水清洗伤口,使用手术刀和动脉钳清创,并用SufraTulle和纱布敷料包扎伤口。

在伤口护理诊所,使用温热的自来水清洁伤口。由于MM先生完全感觉不到疼痛,在没有麻醉/止痛药的情况下使用手术刀和动脉/解剖钳进行连续外科器械清创,并使用当地生产的两部分氧化锌敷料包扎伤口。

由于MM先生的左下肢有一定程度的水肿(图1),表明血液循环停滞,因此在包扎Unna靴的初始阶段需要轻微加压。在所有水肿都消退后,用敷料后续包扎时不再加压。

随后每次更换敷料时,都根据需要清创伤口,并使用当地生产的氧化锌敷料(Unna靴)包扎伤口。在重复清创后,于2018年11月12日进行了第一次Unna靴包扎(图5和图6)。2018年11月14日,在切开和引流后,用Unna靴进行第二次更换包扎。第三次更换Unna靴是在2018年11月16日,此后,每周一和周五继续来门诊更换Unna靴,共持续两个月。由于我们向他的儿子指导了如何在家中更换敷料,在第三个月将清创的频率调整到了每周一一次。之后,他会在周一更换敷料,然后每两周到诊所接受一次患者和伤口评估,并评估他更换敷料的技巧。随后继续以这种方式护理,使用当地生产的氧化锌敷料(Unna靴)作为诊所和家中的主要包扎方法,直到四个月后的2019年3月17日三个伤口完全愈合为止。

多学科方法

MM先生的DFU管理非常复杂,需要采用多学科团队方式指导他的护理。

骨科医生

MM先生的首次就诊和出血性胼胝清创发生在2018年11月10日。第二个溃疡是在2018年11月12日出现或注意到的,当时MM先生是第二次来到糖尿病诊所,之后他被转介给骨科医生。骨科医生评估了足背动脉和胫后/胫前动脉的脉搏,并要求他拍足部X光片。在检查X光片报告后,由于没有累及骨骼,患者被转介至伤口护理服务。

后来于2018年11月14日确诊了化脓性肌炎,在由注册的临床骨科工作人员进行切开和引流时,发现第三个伤口(图8和图9a)。当时,不可能让骨科医生参与其中,但临床工作人员也专门从事骨科,并且与骨科医生密切合作完成了切口和引流,并开出克林霉素处方,每8小时口服1克,连续服用7天。

骨科技术专家:足部和压力减轻

管理MM先生的DFU时,关键的干预措施是减轻患病足部所承受的压力。他接受了骨科技术专家的检查,并被告知减轻压力的好处以及需要改变鞋子。根据骨科技术专家的建议,改穿带衬垫的敞口鞋,而不是封闭式的鞋。

营养师

营养师、糖尿病教育工作者和护理人员向MM先生和其家属提供了关于饮食要求、控制血糖水平(BSL)的建议,并提供了一般健康指导,包括每日足部检查和护理建议。

社会心理支持

有时,DFU显示出伤口愈合停滞的迹象,此时伤口的状态没有变化(图12)。在这些情况下,向MM先生提供了心理辅导和心理支持,告知他这种情况经常发生在这类性质的伤口上。鼓励他继续接受治疗方案的所有治疗。

出院计划、社区护理和长期随访

与MM先生、其妻子和儿子一起开展了一次家庭治疗会诊,向他们提供了在家中进行伤口护理、饮食管理、足部检查和BSL监测方面的知识。强调了MM先生尽可能积极进行自我护理的重要性,以避免DFU恶化和/或复发,并改善其整体健康。

向MM先生的妻子和儿子指导了如何检查伤口、检查足部溃疡出现前的迹象,以及如何用Unna靴包扎伤口(图13a和图13b)。鉴于穿着合适的鞋子是防止DFU复发的关键因素,还告知他们如何识别鞋子是否不合脚或不合适。

MM先生购买了一台血糖仪,用于在家监测空腹BSL,其稳定在6-8 mmol/L。

讨论

大多数糖尿病患者在其一生中会有一次DFU经历22。DFU不仅发病率和死亡率高,还会带来巨额的医疗开销23。

糖尿病神经病变导致足部知觉丧失引起的痛觉缺陷;因此糖尿病神经病变患者很少会早期寻求护理。足部无知觉时,足底表面或足底更容易受到剪切力和压力的影响,从而增大伤害24。运动神经病变导致内在足部肌肉消耗,而自主神经病变会造成出汗干燥以及足部鳞屑。这些现象导致溃疡出现、足部畸形和关节活动性缺陷。

遗憾的是,DFU管理通常是由医院实施,而他们对DFU的致病因素、诊断和管理的现有知识和洞察力都欠佳。即使在发达国家,糖尿病专家也会将患者转诊到社区护理服务部,那里的护士缺乏必要的知识和临床能力,无法熟练地管理这些伤口25。作为一个多方面的问题,使用循证方式,加强多学科团队合作和特定医疗看护机构的临床方案可以取得更好的结果。研究发现,以护士为主的足部护理计划在预防DFU方面是有效的26。

护士负责管理转诊到肯尼亚莫伊教学与转诊医院伤口护理服务部的DFU病例。自2010年至今,医院管理层已经请一名骨科医生、两名护士、一名注册临床工作人员、一名物理治疗师和一名职业治疗师在南非(RSA)斯泰伦博斯大学参加IIWCC伤口护理课程。

肯尼亚糖尿病(前称肯尼亚糖尿病协会)与国际糖尿病联合会密切合作,为我院的目前共六名多学科糖尿病教育工作者提供培训(三名护士、一名注册临床工作人员和两名医师)。这些团队(伤口/糖尿病)为医院的其他工作人员组织内部培训,并在可能的情况下参加国家会议和研讨会,以增进知识和实践,以便在医院建立一个热情的伤口护理实践社区。

MM先生是从100多公里外的公司诊所转介而来的,转介原因是缺乏能管理其DFU的医疗护理人员。

DFU的管理通常很复杂,需要采用多学科方法实现最佳结果。多学科团队可以降低DFU并发症的发生率和相关并发症的严重程度;减少截肢;提高患者的生活质量;并且,延长患者的预期寿命22。在这种情况下,骨科医生、骨科技术专家、营养师、心理辅导员和护理人员与MM先生家人的集体临床合作能够挽救MM先生的足部,促进伤口愈合并避免部分或全部足部截肢。对于MM先生,伤口管理的关键干预措施包括伤口清创、局部伤口护理、减轻压力、稳定BSL、患者教育和社会心理支持。

对失活、不健康的组织进行伤口清创,以暴露健康的出血组织,这可以更好地观察溃疡的程度和留置的脓肿或窦道27,28。此外,这降低了感染传播的风险,并减轻了源自胼胝的创周压力,所有这些都促进了正常的伤口收缩和愈合29。在DFU患者中,估计有20%的中度至重度感染患者需要某种程度的截肢30,31。因此,在每次更换敷料时进行保守的外科器械伤口清创术。

伤口护理方案包括用温热的自来水清洗伤口,用手术刀和动脉/解剖钳进行外科器械清创,用20cc注射器注射生理盐水,并且主要应用氧化锌敷料进行包扎,并在外层包扎6英寸的绉纱绷带。

由于存在感染,第一周的连续清创和更换敷料频率是隔天一次,然后是每周一和周五各一次(一周两次),此后每周一一次(每周一次),但是在伤口护理的第四个月,患者的儿子会在家中为其更换一次,然后每两周来一次诊所。

在四个月时间内,使用当地生产的氧化锌敷料(Unna靴),并应用重要的基本伤口护理原则以促进伤口愈合。敷料中的氧化锌被认为可以减轻炎症、保护周围皮肤、增强再上皮化并减轻水肿。Unna靴氧化锌绷带干燥在下肢周围形成一个温暖、舒适的靴子,通过患者行走时肌肉收缩提供的高压支持静脉回流,但在患者静息时提供的压力很小,这有助于溃疡的愈合。

虽然患者接受使用这种敷料,但是工作人员必须经过培训,使其能够正确评估足部和伤口,并正确包扎敷料,以避免在神经病变的情况下造成肢体收缩和动脉闭塞32-34。重要的是,在对下肢施加任何压迫之前评估沿足背动脉和胫后动脉29血管的血流。MM先生报告说,在包扎Unna靴之后,他对左腿感觉更加安全和自信了。

在理想情况下,DFU管理要求患者的患病区域没有承重,以促进愈合。有多种策略可以减轻DFU部位的压力,包括现成的矫形鞋、定制的鞋类,包括可以模制以适应足部轮廓的鞋垫、接触石膏和外部衬料。使用的减轻压力方式取决于患者和环境因素、是否能获得矫形鞋以及成本35,36。将这些因素考虑在内,并为MM先生的DFU减轻压力,骨科技术专家建议他改穿用敞口式衬垫鞋。骨科技术专家没有在MM先生的脚上使用任何额外的衬垫,但建议他改穿更大号带衬垫的敞口鞋,以减轻伤口的压力。他建议说,MM先生之前穿的鞋子太紧,带子和扣带不含衬垫,这导致出现了第二个伤口。

由于DFU导致日常生活中身体活动减少,这会影响心理和社会健康,因此严重影响与健康相关的生活质量。这通常可能导致社会孤立,对家庭关系产生不利影响的紧张情绪,无法工作或失业造成的经济困难,以及DFU患者的情绪压力和抑郁症状37。然而,这些因素受个体患者的临床特征所影响,包括社会人口统计学和环境因素38。

自我护理是获得最佳健康状态,并以最佳方式管理糖尿病的首要因素。这一目标可以通过使用护理理论和模式来有效地实现,诸如Orem自理模式等38。Borji等人认为,“自我护理是一种重要而且有价值的做法,因为它凸显了人们对其自身医疗保健扮演一个积极的角色,而不是被动的角色。此外,...自我护理的行为受一个人(或亲属)所拥有并实际付诸努力的全部技能和知识所影响,”从而需要改变那些影响一个人的健康和福祉的因素39。

因此,护士通过帮助患者及其家属了解糖尿病和DFU的根本原因,对患者和家庭的指导发挥着关键的作用。这种知识使患者及其家人能够在他们进行临床和心理社会护理时,在解决问题和决策方面扮演积极的角色40,41。

自我护理的一个例子是指导MM先生和其家人,使他们了解他的饮食以及饮食和运动在帮助稳定糖尿病和BSL的重要性,在这种情况下,MM先生能够积极参与到他的护理之中。

护理人员还向MM先生的妻子和儿子进行了临床指导,帮助他们了解如何在家中管理MM先生的伤口和足部护理。这包括在家中进行Unna靴包扎(图13a和图13b)。

由于成功治疗DFU后,在同一肢体或对侧肢体的同一部位或不同部位出现新溃疡的可能性很高42,因此要求MM先生作为门诊患者随访,以确保DFU不再复发,这一点非常重要。

糖尿病足并发症的变种现在已经更普遍。这是因为全球糖尿病发病率的升高以及更好的管理方式延长了预期寿命。这要求糖尿病护理人员能够进行方案转换,专注于当前在预防、诊断和管理DFU以及其他糖尿病足并发症方面的趋势以及新兴趋势27。因此,有必要向医疗专业人员和患者进行糖尿病教育,并指导糖尿病伤口管理,因为医疗护理人员和医疗专业人员也可能与患者的DFU发生以及DFU恶化有关43。随着全球糖尿病和DFU的增加,需要所有医疗保健专业人员引起关注,特别是采用有效的多学科团队方法进行诊断和管理,包括护理和患者参与44。

结论

糖尿病(DM)和糖尿病足溃疡(DFU)的发病率在全球范围内都在升高。并非所有医疗保健提供机构和健康专业人员都接受过足够的DFU评估和管理教育。将DFU患者转诊至在DFU评估和管理方面拥有专业知识的医疗机构对于患者治愈以及医疗机构取得良好成果至关重要。

将MM先生转介到我院,在医院采用多学科方法管理DFU,促进伤口愈合,保肢并防止左下肢进行不必要的截肢,这无疑提高了他的整体生活质量。

在伤口管理方面拥有专业知识的护士用自我护理理论向MM先生及其家属提供了指导,使他们了解糖尿病的相关知识,以及如何在诊所和社区环境中进行BSL控制和监测、伤口护理以及足部护理。

致谢

我们在此感谢加州大学和莫伊大学/Ampath Eldoret的客座讲师Aileen Chang博士,感谢她对撰写本文献所提供的指导。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Margaret Mungai

MBA-Strategic Mgt, IIWCC,BSC N

Moi Teaching & Referral Hospital

Eldoret, Kenya (East Africa)

Deputy Director Nursing-Clinical Services

Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in Eldoret Kenya

Emmy Sirmah

Wound Care Nurse

Wound Care Services Clinic

Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital Eldoret, Kenya

Correspondence to Margaret Mungai

Email margiemungai@gmail.com/margaretmungai@mtrh.go.ke

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Estimates: Death by cause, Age, Sex and County 2000–2012. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Day 2016: Beat Diabetes.

- Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM & Bus SA. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. New Engl J Med 2017; 376(24):2367–2375. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1615439

- Boulton AJM. The diabetic foot: grand overview, epidemiology and pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2008; 24(Suppl 1):S3–6. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.833.

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn. IDF; 2015.

- Mohamed SF, Mwangi M, Mutua MK et al. Prevalence and factors associated with pre-diabetes and diabetes mellitus in Kenya: results from a national survey. BMC Public Health 2018; 18(Suppl 3):1215. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6053-x

- IWGDF Editorial Board. IWGDF Definitions and Criteria. IWGDF; 2019. Available at: https://iwgdfguidelines.org/definitions-criteria/. Accessed 04/23, 2019.

- Nyamu PN, Otieno CF, Amayo EO & McLigeyo SO. Risk factors and prevalence of diabetic foot ulcers at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J 2003 Jan; 80(1):36–43.

- Waaijman R, de Haart M, Arts ML et al. Risk factors for plantar foot ulcer recurrence in neuropathic diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(6):1697–705. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2470.

- Cutting KE & Harding KG. Criteria for identifying wound infection. J Wound Care 1994; 3(4):198–201.

- Kibachio JM, Omolo J, Muriuki Z et al. Risk factors for diabetic foot ulcers in type 2 diabetes: a case control study, Nyeri, Kenya. African Journal of Diabetes Medicine 2103; 21(1):20–23.

- McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH et al. The independent contributions of diabetic neuropathy and vasculopathy in foot ulceration. How great are the risks? Diabetes Care 1995; 18(2):216–19.

- Prompers L, Hujberts M, Apelqvist J et al. High prevalence of ischaemia, infection and serious comorbidity in patients with diabetic foot disease in Europe. Baseline results from the Eurodiale study Diabetologia 2007; 50(1):18–25.

- Bronze MS & Khardori R. Diabetic Foot Infections. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/237378-overview2019.

- Seah MYY, Anavekar SN, Savige A & Burrell LL. Diabetic pyomyositis: An uncommon cause of a painful leg. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(7):

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(12):132–173.

- Gemechu FW, Seemant FNU & Curley CA. Diabetic foot infections. Am Fam Physician 2013; 88(3):177–184.

- World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS). Florence Congress, Position Document. Advances in wound care: the Triangle of Wound Assessment Wounds International. WUWHS; 2016.

- Varnado M. Lower Extremity Neuropathic Disease. In: Core Curriculum Wound Management. Doughty DB & McNichol LL, eds. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2016.

- Apelqvist JG. Ragnarson–Tennvall G, Lairsson J & Persson U. Diabetic foot ulcers in a multidisciplinary setting. An economic analysis of primary healing and healing with amputation. J Intern Med 1994; 235(5):463–467.

- Khunkaew S, Fernadez R & Sim J. Health-related quality of life among adults living with diabetic foot ulcers: a meta analysis. J Qual Life Res 2019 Jun; 28(6):1413–1427. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-2082-2

- Yazdanpanah L, Nasiri M & Adarvishi S. Literature review on the management of diabetic foot ulcers. World J Diabetes 2015; 15;6(1):37–53.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2016. In: Diabetes Care 2016; 39(Suppl 1).

- Lavery LA, McGuire JB, Baranoski S, Ayello EA & Kravitz SR. Diabetic Foot Ulcers. In: Baranoski S & Ayello EA, eds. Wound Care Essentials Practice Principles, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Schaarup C, Pape-Haugaard L, Jensen MH, Laursen AC, Bermark S & Hejlesen OK. Probing community nurses’ professional basis: a situational case study in diabetic foot ulcer treatment. Br J Comm Nurs 2017; 22(Suppl 3):S46–S52. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.Sup3.S46

- Fujiwara Y, Kishida K, Terao M et al. Beneficial effects of foot care nursing for people with diabetes mellitus; an uncontrolled before and after intervention study. J Adv Nurs 2011; 67(9):1952–1962.

- Uçkay I, Aragón-Sánchez J, Lew D & Lipsky BA. Diabetic foot infections: what have we learned in the last 30 years? Int J Infect Dis 2015; 40:81-91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.09.023.

- Frykberg RG, Armstrong DG, Giurini J et al. Diabetic foot disorders: a clinical practice guideline. American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. J Foot Ankle Surg 2000; 39(Suppl 5):S1–60.

- Kruse I & Edelvan S. Evaluation and treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Clin Diabetes 2006; 24(2):91–93.

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:e132–e173.

- Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Wunderlich RP, Tredwell J & Boulton AJ. Diabetic foot syndrome: evaluating the prevalence and incidence of foot pathology in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites from a diabetes disease management cohort. Diabetes Care 2003; 26:1435–1438.

- Fonder MA, Lazarus GS, Cowan DA et al. Treating the chronic wound: A practical approach to the care of non-healing wounds and wound care dressings. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 58(2):185–206.

- Luz BSR, Araujo SC, Novato Castelli Von Atzingen DA & Rodrigues dos Anjos Mendonça A. Evaluating the effectiveness of the customized Unna boot when treating patients with venous ulcers. An Bras Dermatol 2013; 88(1):41–9.

- Matos de Abreu A & Guitton Renaud Baptista de Oliveira B. A study of the Unna Boot compared with the elastic bandage in venous ulcers: a randomized clinical trial1. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem 2015 July–Aug; 23(4):571–7 DOI: 10.1590/0104-1169.0373.2590

- American Diabetes Association. Microvascular complications and foot care. Sec. 9. In Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2016. Diabetes Care 2016; 39(Suppl 1):S72–S80.

- van Netten J, Lazzarini PA, Armstrong DG et al. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research (2018) 11:2 doi: 10.1186/s13047-017-0244-z

- Goodridge D, Trepman E & Embil JM. Health-related quality of life in Diabetic patients with foot ulcers: Literature review. J Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing 2005; 32(6):368-377.

- Nemora J, Hlinskova E, Farsky I et al. Quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcer in Visegrad countries. J Clin Nurs 2017; 26(9–10):1245–1256.

- Borji M, Otaghi M & Kazembeigi S. The impact of Orem’s Self-care Model on the quality of life in patients with type ii diabetes. Biomedical & Pharmacology Journal 2017; 10(1):213–220.

- Aalaa M, Tabatabaei Malazy O, Sanjari M et al. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2012; 11:24. http://www.jdmdonline.com/content/11/1/24

- Ghafourifard M & Ebrahimi H. The effect of Orem’s self-care model-based Training on self-care agency in Diabetic patients. Scientific Journal of Hamadan Nursing and Midwifery Faculty 2015; 2(1):5–13.

- Orneholm H, Apelqrist J, Larsson J & Eneroth M. Recurrent and other new foot ulcers after healed plantar fore foot diabetic ulcer. Int J Tiss Rep Regen 2017; 25(2):309–315.

- Macfarlane RM & Jeffcoate WJ. Factors contributing to the presentation of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabet Med 2004; 14 (10):867–870.

- Sibbald GR, Ayello EA, Eliot J, Smart H & Stelton S. 2016 Cape Town declarations of action on diabetic foot ulcers and insulin access. WCET Journal 2016; 36(2):30–37.