Volume 39 Number 3

Healthcare professionals and interactions with the medical devices industry

Paris Purnell

Keywords compliance, medical devices, nursing profession, ostomy, ethics, industry, healthcare professionals

For referencing Purnell P. Healthcare professionals and interactions with the medical devices industry. WCET® Journal 2019; 39(3):32-36

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.3.32-36

Abstract

Compliance laws for healthcare professional practices are evolving continuously. It can therefore remain difficult to remain abreast of all laws that apply across all countries. This paper serves as guidance for best practice for healthcare professionals (HCPs) working alongside the medical devices industry.

Introduction

Engaging with product manufacturers and suppliers from within the medical devices industry should, at its best, be a symbiotic relationship where both the healthcare professional (HCP) and the industry representative – henceforth referred to as Industry – derive mutual, yet appropriate, benefits. This relationship should be driven by the ultimate objective of improving patient outcomes. However, this affiliation can be challenging when ensuring objectivity and compliance for both Industry and the HCP. For example, recent global changes of compliance laws designed to govern these affiliations can make it difficult to ensure all parties remain compliant. However, the overall trend is toward transparency by Industry on any such interactions, and these same considerations are increasingly becoming the focus of employers of HCPs as well as the HCP professional bodies.

This paper focuses on global and local laws, codes and market trends in compliance to better inform and protect the HCP. By being more aware of the compliance requirements and legal ramifications when interacting with Industry, the HCP will be in a better position to navigate complex interactions that may place them at risk.

What is Compliance?

Compliance involves a broad series of interactions with HCPs and includes activities such as the promotion of advancements in medical technologies, enhancements in the safe and effective use of medical technologies, research and education activities, and fostering of charitable donations and giving1. For the purposes of this paper, ‘compliance’ is used to describe the ethical code where the first duty of the HCP is to act in the best interests of the patient by working through beneficial relationships with industry in a transparent and ethical manner. Additionally, while the descriptor for a HCP covers most multidisciplinary healthcare workers, this paper refers specifically to the nursing HCPs prescribing medical devices for patients such as ostomy, wound care and continence as this is the audience for this journal. Lastly, medical devices are often highly dependent upon ‘hands on’ HCP interaction from beginning to end, unlike drugs and biologics which act on the human body by pharmacological, immunological or metabolic means2. This often requires Industry to provide HCPs with appropriate instruction, education and training.

As described, compliance laws regarding the interactions of HCPs with Industry are continuously changing. Compounding this challenge, are the variances in the compliance laws by country and sometimes even within that country’s boundaries. Ensuring the HCP is cognisant of the potential pitfalls that may not be apparent when contracting with a manufacturer for either a service or another activity – such as sponsorship – are important considerations. Given the changing face of compliance globally – particularly around some commercial activities that might be considered legal (for now) but not necessarily ethical – it is a timely and worthy discussion to guide the HCP in protecting themselves against potential risk.

International and local Compliance Bodies / Local Trade Associations

There are several international compliance bodies (Figure 1) exerting influences on local Industry and HCP interactions. The larger bodies include AdvaMed (mainly influencing US, Chinese and Latin America activities and companies), MedTech Europe (formerly ‘EucoMed’, covering Europe), APACMed (covering Asia Pacific), and MecoMed (covering the Middle East).

Most countries also have compliance bodies locally which, in turn, often ascribe to at least one of these larger governance bodies. These larger bodies generally set the core principles and ethics that local bodies would engage with as members of the parent body. There are far too many local bodies from a global perspective to create an exhaustive list in this paper. However, from a nursing perspective, there are various registration boards for registered nurses/midwives that operate within each country. These boards each have their own code of ethics and professional standards that influence local practices. For example, Australian nurses ascribe to Australian registration boards such as the Australian Health Practitioners Regulatory Authority and Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA)3, the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN)4 and, of course, the WCET5.

Medical devices are also regulated by local governmental agencies which in turn have their own codes. As one example, the Medical Technology Association of Australia (MTAA) is the governing body regarding compliance for the medical devices industry that includes ostomy products in Australia which has strict codes of conduct and laws regarding interactions between HCPs and Industry. According to the MTAA website6:

In all dealings with Healthcare Professionals, a Company must undertake ethical business practices and socially responsible Industry conduct and must not use any inappropriate inducement or offer any personal benefit or advantage in order to Promote or encourage the use of its products.

This basic definition is a concise summary of what Industry should be following in terms of ethical practices in working with any HCP. One key takeaway message from this simple narrative is the term ‘inducement’. Products must be prescribed on clinical application and suitability. Product usage should not be based upon a ‘quid pro quo’ basis where the HCP and the company are deriving either singular or mutual benefits. This is commonly referred to as ‘corruption’.

As such, while local laws and customs often come into play, an important consideration when the HCP wishes to engage with Industry is to err on the side of caution and follow the rules of the compliance body which are the most stringent. As an example, while some manufacturers in the EU may not necessarily fully ascribe to these bodies, from 2020 MedTech Europe has determined that ALL local trade associations must abide by stricter MedTech Guidelines7. These enforceable ethical standards will be placed on Industry to come into line with all other already compliant manufacturers and service providers.

Corruption and Sponsorship

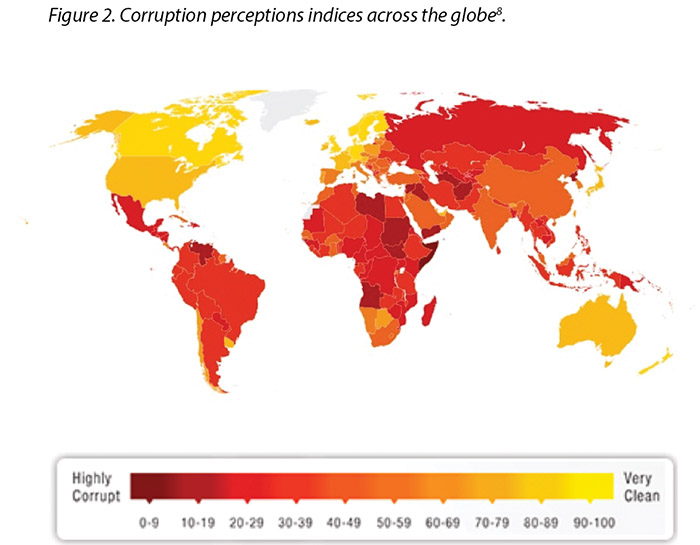

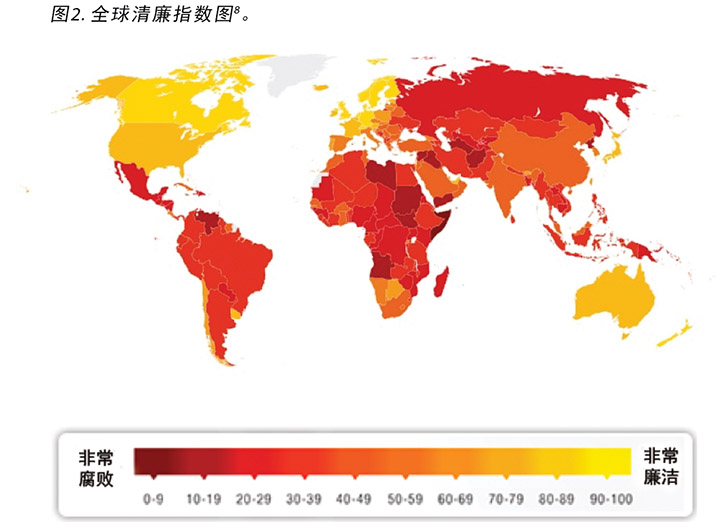

However, laws are constantly changing regarding corruption and sponsorship. Transparency International has developed and mapped the perception of corruption indices across the globe concerning all industries and governments, with darker colours illustrating the perception of higher levels of corruption8; the more yellow (lighter colour), the perception is cleaner and freer from corruption (Figure 2). Yet, while it is good to obtain such a standard, there is an inference that additional scrutiny is required to maintain these standards. This means more oversight into interactions will be assessed. Unfortunately, in recent years, the majority of countries are making little or no progress in ending corruption, while further analysis shows journalists and activists in corrupt countries risk their lives each day in an effort to speak out8.

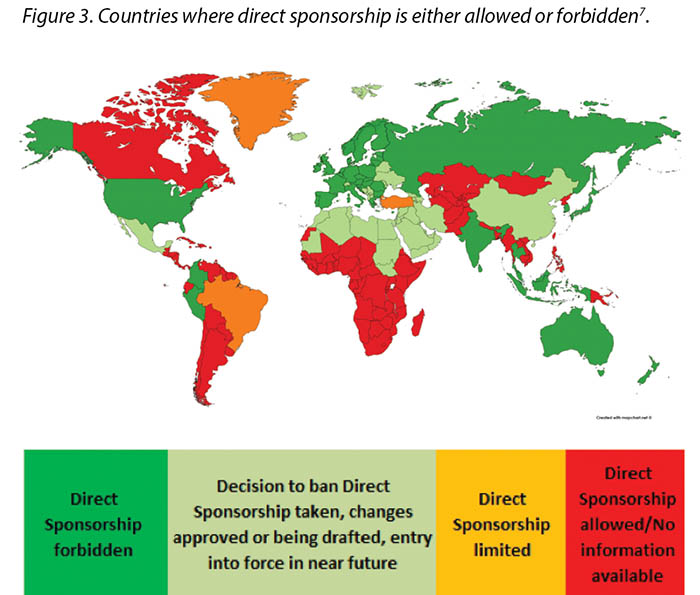

Previously, direct sponsorship usually involved the selection of the HCP by the Industry and direct payment by Industry to the HCP, their institution, or a third-party vendor for the HCP’s travel, lodging, meals, other transportation expenses, conference registration fees or other costs associated with a third-party educational conferences such as those hosted by the European Council of Enterostomal Therapy (ECET), the Society of Urologic Nurses and Associates (SUNA), the Symposium on Advanced Wound Care (SAWC), WOCN or WCET conferences2. This is being, or has already been, phased out in many countries; MedTech Europe illustrates where direct sponsorship is forbidden7 (Figure 3).

Additionally, the concept of direct sponsorship can mean arrangements where Industry selects or influences the selection of a specific HCP through their institution or professional body, or was provided with advance knowledge of the identity of a specific HCP who might benefit directly from Industry funding2. This practice is an ‘indirect’ method of achieving the same objective of direct sponsorship whereby deliberate sponsorship of a specific HCP still occurs. As such, this is also not permissible. As a consequence, the funding must be indirect via an educational grant. MedTech Europe creates another level by enforcing some transparency requirements for all educational grants provided by the industry to healthcare organizations. Access to the transparency report is available on: https://www.ethicalmedtech.eu/transparent-medtech/

General Rules of Engagement for the HCP with Industry

There are several topics for discussion around some rules of engagement for the HCP with Industry, including entertainment, hospitality, event venues and location, travel, contracting, remuneration / compensation, transparency, gifts and samples. Each of the following discussions regarding these outline global compliance standards.

Entertainment

It is prohibited for Industry to organise Industry events – including social, sporting and/or leisure activity or other forms of entertainment – that has no value in terms of education, for example, providing a famous singer at an event, taking nurses to a spa treatment day as an example of managing patients’ skin issues, creating fun artworks/animals using specific medical devices that have no relation to intended use etc. It is also forbidden for Industry to support such entertainment when part of a third-party event, for example live music, sport event, dancing contest. However, there is some tolerance in a third-party event when such entertainment is outside of the scientific / educational programme, is paid for by the HCP, does not dominate / interfere with the educational programme, and is not the main attraction.

Hospitality

Hospitality in this sense relates to meals and/or accommodation. Accommodation should be subordinate in time, with no extensions of stay unless paid for by the HCP. It should only be for the time of the event/meeting that is necessary. Some of these rules are often determined by type of meeting being arranged, for example if the meeting is classified as ‘active’ or ‘passive’. Active events are where the HCP is expected to actively participate and contribute in the meeting, for example a Clinical Advisory Board or Consensus Panel. In these types of events, the HCP is in essence ‘working’ and it is expected that costs incurred for attending the meeting would be reimbursed by Industry. In contrast, passive events are where Industry is presenting to the audience with no reciprocal interaction being required by the HCP. Regarding product promotional events that are organised by Industry – even if they are educational, for example the launch of a new product – no transportation nor hotel fees should be supported. The HCP is expected to cover these costs themselves as this is considered a passive event. However, modest meals at a passive educational event are permitted.

Generally, the meals and accommodation should focus to the purpose of the event and should be seemed as reasonable, for example such as what the HCP would expect to pay by themselves. Recommendations around these values have been determined by trade associations on local laws, and these have been set up in most countries in the world. Maximum amounts for lunches and dinners have been outlined for every country – the rule to apply is generally that of the law governing the hospitality of the country where the HCP is licensed to practise.

Event venues and locations

Industry should respect the following criteria when selecting a venue for an event.

- Perceived image – how it could be seen by the public.

- Centrality – whether it is centrally located for the participants.

- Ease of access – whether it has easy transportation, is close to airport/venue. A recognised scientific or business centre is preferred.

- Time of year – ideally this should not be associated to a tourist season.

- Adapted to the purpose of the meeting – are the rooms appropriate for their intended use.

An event location where the meeting purpose appears secondary to the location is seen as an inducement for the HCP to attend based on the location and not the content or objective of the meeting. As such, event locations should not be lavish such as five-star, golf facilities, spa retreats etc. If the HCP notices the event venue seems inappropriate (for example an amusement park or a retreat), the HCP should reconsider the event.

Travel

When Industry is arranging travel, it must be directly linked to the meeting length and cannot be extended for the purpose of sightseeing / family visits etc. Industry cannot cover a period of stay beyond the official duration of the event.

Travel is linked only to the purpose of the meeting and, like hospitality, should be modest and reasonable – no business / first class air tickets. Related travel expenses for active meetings such as parking, train fares etc. are reimbursable but should be agreed upon prior to the expense.

Contracting

Industry may engage HCPs as consultants and advisors to provide bona fide consulting and other services, including research studies, participation on ostomy/wound advisory boards, presentations at Industry educational events, and new product development. In selecting the HCP, there should be appropriate criteria that includes:

- Legitimate interest – Industry should not contract with a HCP ‘just in case’ or if there is a lack of in-house competencies.

- Appropriate qualifications – the HCP should be technically and scientifically qualified, with the right competencies to achieve the assignment. Industry should collect a CV for documentation and to justify any compensation.

- No financial gain – selection should be detached from sales to avoid any influence.

Contracts with the HCP shall not be contingent in any way on the prospective consultant’s past, present or potential future purchase, lease, recommendation, prescription, use, supply or procurement of the contractor’s products or services. In other words, there is no ‘quid pro quo’ expectation from Industry that the HCP will use/prescribe their products.

Contracts must involve appropriate documentation to justify the compensation – if any – paid to the HCP. MedTech Europe and AdvaMed have specific requirements for written agreements with the HCP1,7. The contracts also protect Industry by ensuring confidentiality on projects is maintained for new products or strategies so they are not shared with competition. Industry also maintains rights to use the material / research / studies developed by the HCP during the assignment. Lastly, contracts must provide transparency. They ensure information of, and to, the HCP’s employer on the existence of the contract, state exactly what the assignment is, and how much compensation (if any) is paid to the HCP.

Remuneration / compensation

When compensating the HCP for their services, reasonable and fair market value (FMV) compensation should be aligned with the market value for that HCP and the type of service. Guidance on FMV should be sought with compliance officers or the local HCP’s Association, for example the NMBA. In addition, documentation of the type and the length of service with associated remuneration is to be captured and signed off by both Industry and the HCP prior to the event occurring.

Transparency

Before engaging with Industry, as a best practice it is strongly suggested that the HPC should gain approval / notification of the HCP’s employer. While not always mandatory, this transparency covers both parties if there arises any questions regarding conflicts of interest. The employer of the HCP should receive full disclosure of the purpose and scope of consultancy agreement. Additionally, all Industry contracts should contain a clause on the obligation of the HCP to notify the existence of the agreement to their hierarchy. It is prudent to check local requirements.

Gifts

In principle, it is prohibited by Industry to provide gifts to the HCP. Local customs may need examining to determine if this is still permissible. For example, in Japan and Thailand there is frequently an expectation of gifts of thanks. These should not be excessive in nature and should not create any expectations of quid pro quo. Local customs and laws may come into play; however, it is recommended to check with a compliance officer prior to engaging in any gifting activities if there is any ambiguity. In some countries, it is now no longer permissible to give birthday or bereavement cards or flowers, and local laws should be evaluated prior to exploring the potential for providing such gifts.

Industry may provide inexpensive educational items and/or gifts in exceptional circumstances, in accordance with local laws, regulations and industry and professional codes of conduct of the country where the HCP is licensed. Excluded ‘educational’ items are DVD players for playing educational movies, or cameras for wound care as these can be used for other purposes. Acceptable educational gifts can be purely educational (medical) book vouchers, registration to third-party events or educational courses, although these are paid to the third-party only – no cash should be paid direct to any HCP. Again, full transparency is required and documentation should be provided to cover both parties.

Samples

Industry may provide products as samples at no charge in order to enable the HCP to evaluate and/or familiarise themselves with the safe, effective and appropriate use and functionality of the product. This will allow HCPs to determine whether, or when, to use, order, purchase, prescribe or recommend the product and/or service in the future. Provision of samples must not improperly reward, induce and/or encourage HCPs to purchase, lease, recommend, prescribe, use, supply nor procure their products or services.

Any offer and/or supply of samples shall always be done in full compliance with applicable national laws, regulations and industry and professional codes of conduct.

Recent US and European laws, as well as MedTech guidelines in the EU7, require the maintenance of appropriate records in relation to the provision of samples to HCPs, for example recording proof of delivery of samples. These are now to be clearly recorded in the books on a no-charge basis, and this and other conditions applicable for the supply of such samples must be clearly disclosed – in writing and at the time of supply – to HCPs.

The concern is the over-supply of samples (dumping) that may be perceived as an inducement to use the certain products. Samples, as described, should be modest. Anecdotally, for the ostomy Industry, there appears to be an oversupply (stocking) of products at many institutions instead of these institutions purchasing. This practice is possibly in need of further scrutiny.

Red Flags – Warnings

The HCP should become familiar before considering interactions with Industry across multiple issues. There are certain common ‘red flags’ that should create alerts in the mind of the HCP that include situations where there is:

- Wording or phrasing with ‘win’, ‘gift’, or ‘prize’.

- No professional educational relationship associated with the benefit.

- Entertainment.

- A submission for ‘competitions’ judged only by Industry manufacturers (no third-party).

- A value which is high in comparison with the effort required.

- Anything which seems ‘too good to be true’.

- Excessive sampling (dumping) of products.

General Rules of Thumb for Protecting the HCP

- Obtain the full rules of engagement from the device manufacturer.

- Review it with your existing employer’s audit committee /managers.

- Check with your professional body, both local and national.

- Review any available guidelines, both local, national or institutional.

- If in doubt, don’t do anything.

- Consider the ‘optics’ – how might the interaction look if it appeared in the news? Is this clean and free from potential misunderstanding?

Conclusion

There are risks for the HCP when engaging with Industry, and rules and laws are constantly changing. It is difficult to remain ahead and informed of these continuous changes; however, this paper aims to raise awareness of this ever-changing landscape. For the HCP, it is a wise idea to check and follow the rules of engagement, observe the red flags and, if there are any doubts, to err on the side of caution and simply not engage. Ultimately, the goal for each party is to improve patient outcomes and create a prosperous dynamic that is compliant. Interactions between Industry and the HCP are inevitable, but if the relationship is open, honest and transparent, with clear rules of engagement and oversight, these relationships can be extremely fruitful for each party.

Disclaimer

Laws from regulatory bodies are frequently updated. At the time of print, this is a fair assumption of current practices. As always, it remains advisable to seek further guidance from the HCP local regulatory body or employer if there is any doubt before any action/s is taken.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

专业医护人员及其与医疗器械行业的互动往来

Paris Purnell

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.3.32-36

摘要

针对专业医护人员实践的合规性法律在不断发展。因此,始终及时了解各国适用的所有法律非常困难。本文可作为与医疗器械行业打交道的专业医护人员(HCP)的最佳实践指导。

前言

与医疗器械行业内的产品制造商和供应商打交道时,最佳情况是形成一种共生关系,即专业医护人员(HCP)和行业代表(以下简称“行业”)均能获得共同、但正当的利益。促进这种关系的因素应该是改善患者结果这一最终目标。但是,在同时确保行业和HCP的客观性与合规性时,这种友好关系可能会受到挑战。例如,最近在全球范围内,旨在管理这些关系的合规性法律都发生了变化,使得更难确保各方均保持合规。但是,总体朝着行业在各种互动活动中趋向透明化的趋势发展,而且HCP的工作单位及HCP专业机构也越来越关注这些问题。

本文着眼于全球各地有关合规性的法律、规范和市场趋势,以便更加有效地提供资讯并保护HCP。在与行业互动往来时,对合规性要求及其法律后果的更深入了解可使HCP能够更好地处理可能为其带来风险的复杂互动活动。

什么是合规?

合规涉及与HCP的广泛互动活动,包括推动医疗技术的进步、加强医疗技术的安全有效使用、研究与教育活动、促进慈善捐赠和捐助等活动1。本文中,“合规”一词用于描述道德规范,即HCP的首要职责是通过以透明且合乎道德的方式与行业形成互利关系并与之合作,从而实现患者的最大利益。另外,虽然HCP的范畴包括大部分多学科医疗工作者,但本文特指为造口、伤口护理和失禁等患者开具医疗器械处方的护理HCP,因为他们是本杂志的读者群。最后,医疗器械通常从始至终高度依赖“实地操作”的HCP互动,这与通过药理学、免疫学或代谢方式作用于人体的药物和生物制品不同2。这通常要求行业向HCP提供适当的指导、教育和培训。

如前所述,有关HCP与行业之间互动往来的合规性法律在不断发展。更复杂的是,不同国家的合规性法律并不相同,甚至有时候同一国家境内的合规性法律也存在地区差异。与制造商订立服务或其他活动(如赞助)的合约时,确保HCP了解可能不太明显的潜在陷阱非常重要。鉴于全球合规性法律在不断改变,尤其是有关某些(目前)可能视为合法但未必合乎道德的商业活动的合规性法律,现在有必要及时进行讨论,以指导HCP保护自己,避免潜在风险。

国际与地方合规机构/地方行业协会

几个国际合规机构(图1)可对地方行业与HCP之间的互动往来产生影响。大型机构包括先进医疗技术协会(AdvaMed,主要影响美国、中国和拉丁美洲的活动和公司)、欧洲医学技术联盟(MedTech Europe,前称“EucoMed”,涵盖欧洲)、亚太医疗技术协会(APACMed,涵盖亚太地区)和MecoMed(涵盖中东地区)。

大部分国家还设有地方合规机构,它们通常隶属于至少一家上述大型管理机构。这些大型机构通常制定核心原则和伦理标准,地方机构作为母机构的成员参与其中。全球范围内的此类地方机构多如牛毛,本文无法详尽列出。但是从护理的角度来看,目前有不同的注册委员会来管理每个国家境内执业的注册护士/助产士。这些委员会各有自己的道德规范和专业标准,影响着地方实践。例如,澳大利亚的护士隶属于澳大利亚注册委员会,如澳大利亚卫生执业者管理局和澳大利亚护士及助产士委员会(NMBA)3、伤口造口失禁护士协会(WOCN)4,当然还有世界造口治疗师委员会(WCET)5。

医疗器械还受到地方政府机构的监管,这些机构也有自己的规范。例如,澳大利亚医疗技术协会(MTAA)是有关澳大利亚医疗器械行业(包括造口产品)合规性的管理机构,它制定了有关HCP与行业之间互动往来的严格行为准则和法律。根据MTAA网站6:

在与专业医护人员的一切往来互动中,公司必须保证其商业行为合乎道德,行业行为合乎社会责任,不得为了促成和鼓励其产品的使用而采用任何不正当的诱导或提供任何个人利益或好处。

这一基本定义简明扼要地指出了行业与HCP合作时应当遵守的道德行为。这一简单表述中提出了一点重要信息,即“诱导”一词。必须根据临床应用和适当性开处产品。不得根据HCP和公司从中获得单方或共同利益的“交换条件”来选用产品。这种做法通常称之为“腐败”。

因此,如果通常涉及到地方法律和习俗,在HCP希望与行业打交道时,一大重要考虑因素是小心为上,遵守最严格的合规机构规则。例如,虽然并非欧洲的所有制造商都一定完全隶属于这些机构,但是从2020年开始,MedTech Europe决定所有地方行业协会必须遵守更加严格的MedTech指南7。这些可强制执行的道德标准将在行业内实施,以便与所有其他已合规的制造商和服务提供商一致。

腐败和赞助

但是,关于腐败和赞助的法律在不断变化。国际透明组织开发并绘制了有关所有行业和政府的全球清廉指数图,颜色越深说明感知到的腐败水平越高8;颜色越黄(淡),说明越廉洁、腐败越少(图2)。虽然制定此类标准是件益事,但理应还需要其他审查来维护这些标准。这意味着将评估是否需要加强对互动往来的监督。但是近年来,大部分国家在根除腐败上收效甚微,甚至毫无进展,而深入分析表明,腐败国家中的记者和活动家每天冒着生命危险揭发真相8。

过去,直接赞助通常涉及由行业选择HCP并由行业直接向HCP、其所在机构或第三方供应商支付HCP的差旅费、住宿费、餐饮费、其他交通费用、会议报道费或涉及第三方教学会议的其他费用,如欧洲造口治疗委员会(ECET)、泌尿科护士与辅助护士协会(Society of Urologic Nurses and Associates,SUNA)、高级伤口护理研讨会(SWWC)、 WOCN举办的会议或WCET会议2。这个流程在许多国家正在慢慢消失或已经消失;MedTech Europe绘出了禁止直接赞助的国家/地区7(图3)。

另外,直接赞助的概念可能意味着做出一些安排,使得行业可通过其机构或专业机构选择特定HCP或影响对特定HCP的选择,或行业提前获知可能从行业资助中直接获益的特定HCP的身份2。这是一种实现直接赞助的这一相同目标的“间接”方法,借此仍可能发生对特定HCP的蓄意赞助。因此,这也是不允许的。所以,资助必须通过教育补助金间接提供。MedTech Europe对行业向医疗组织提供的所有教育补助金执行一定的透明度要求,从而将监管提高到另一个层次。透明度报告参见:https://www.ethicalmedtech.eu/transparent-medtech/

HCP与行业往来的一般规则

围绕HCP与行业往来的一些规则,有若干话题值得讨论,包括娱乐活动、款待、活动场地和地点、差旅、订约、酬劳/报酬、透明度、礼品和样品等。有关这些话题的以下分项讨论概述了全球合规性标准。

娱乐活动

禁止行业组织毫无教育价值的行业活动(包括社交、运动和/或休闲活动或其他形式的娱乐活动),如邀请著名歌手参与活动、请护士参加水疗日来示范患者皮肤问题的管理、使用与器械预期用途无关的特定医疗器械创作娱乐艺术品/动物等等。还禁止行业支持作为第三方活动组成部分的此类娱乐活动,如现场音乐会、体育赛事、舞蹈比赛等。但是,如果第三方活动中的此类娱乐活动与科学/教育项目无关、由HCP承担费用、不影响/干扰教育项目,也不是主要吸引点,那么可以在一定程度上容忍此类第三方活动。

款待

本文中所指的款待是指餐饮和/或住宿。住宿应限制时间,除非由HCP承担费用,否则不得延长住宿日数。应仅针对必要的活动/会议的时间。其中一些规则通常依安排的会议类型而定,比如会议类别为“主动”还是“被动”。主动活动中,预期HCP将主动参加并在会议上发言,例如临床顾问委员会或共识小组。这类活动中,HCP本质上是在“工作”,出席会议产生的费用预期由行业报销。相反,被动活动指行业向受众做出展示的活动,无需与HCP的双向互动。关于行业组织的产品推广活动,即便是教育性的(如新产品发布会),也不应该提供交通或酒店费用支持。预期由HCP自己负担这些费用,因为该活动视为被动活动。但是,允许在被动教育活动中提供适当的餐饮。

一般来说,餐饮和住宿应着重于实现活动的目的,并应视为是合理的,例如HCP本来预期自付费用的餐饮和住宿。有关这类价值的建议由行业协会根据地方法律确定,世界上的大多数国家已制定了相关建议。已列出每个国家规定的午餐和晚餐的最大金额,适用的规则一般是HCP获取执业许可的国家管理款待的法律规则。

活动场地和地点

行业在选择活动场地时,应遵守以下标准。

- 感知形象——大众如何看待。

- 中心性——是否位于参与者中心。

- 便捷性——是否交通便利,紧邻机场/场地。首选是知名的科学或商务中心。

- 时节——最好不要选择旅游旺季。

- 符合会议目的——房间是否适合预期用途。

如果参会目的次要于会议地点,HCP是因为会议地点而不是会议内容或目标才出席会议,则这种活动地点将视为对HCP的一种“诱导”。因此,活动地点不应太过豪华,如五星级酒店、高尔夫球场、水疗馆等。如果发现活动场地疑似不当(如游乐园或度假村),则HCP应重新考虑是否参与该活动。

差旅

如果由行业安排差旅,则必须与会议时长直接相关,不得以观光/探亲等目的延长差旅时间。行业不得为超出活动官方期限的逗留时间支付费用。

差旅只能与参加会议的目的相关,款待等活动应节制、合理,禁止购买商务舱/头等舱机票。主动会议的相关差旅费用(如停车、火车票等)可以报销,但是在支出前需取得同意。

订约

行业可以聘用HCP作为咨询师和顾问,提供合法的咨询和其他服务,包括调查研究、加入造口/伤口顾问委员会、出席行业教育活动,以及参与新产品开发。选择HCP时,应有适当的标准,包括:

- 合法权益——行业不应为“以防万一”或在内部能力不足的情况下与HCP订约。

- 适当资质——HCP应具备科学和技术资质,以及履行委托任务的适当能力。行业应收集简历,以供记录在案并合理提供任何报酬。

- 无经济收益——选择HCP时应与销售无关,以避免影响。

无论如何,与HCP的合约均不得视该潜在顾问在过去、现在或可能将来对合约商产品或服务的购买、租赁、推荐、开处、使用、供应或采购而定。换句话说,行业不应期望HCP将使用/开处其产品以作为“交换条件”。

合约必须涉及适当的文件记录,以证明支付给HCP的报酬 (如有)的合理性。MedTech Europe和AdvaMed对于与HCP签署的书面协议有特定要求1,7。合约还可以确保维持新产品和新策略的项目保密性,以免泄漏给竞争者,从而保护行业。行业还应维护其对HCP在委托期间开发的材料/进行的调查/研究的使用权。最后,合约必须提供透明度。应确保HCP的工作单位知悉/被告知了合约的存在,明确声明委托的任务,以及支付给HCP的报酬金额(如有)。

酬劳/报酬

为HCP的服务而向其提供报酬时,应以与该HCP和该类服务市场价值相称的合理公允市场价值(FMV)为依据。应向合规官员或地方HCP协会(如NMBA)寻求关于FMV的指导。另外,在活动发生前,行业及HCP都应获得有关服务类型和时长及相关酬劳的文件并进行签署。

透明度

与行业往来前,强烈建议的最佳实践是,HPC获得工作单位的批准/通知。虽然这并非是一贯的强制要求,但如果产生涉及利益冲突的任何问题,双方都在该透明度要求范围内。HCP工作单位应收到有关咨询协议目的和范围的完全披露信息。另外,所有行业合约都应包含一项条款,规定HCP有义务向其领导层告知合约的存在。审慎的做法是检查地方要求。

礼品

原则上,禁止行业向HCP提供礼品。可能需要评估地方习俗后,才能确定是否允许送礼。例如,在日本和泰国,经常期望获得感谢礼。但从性质而言,礼品不应过度,也不应形成任何达成“交换条件”的期望。可能会存在地方习俗和法律问题,但是,如果存在不明确的情况,建议在进行送礼活动前先咨询合规官员。某些国家,现在不再允许送生日贺卡或吊慰鲜花,在摸索是否需提供此类礼品前,应该先对地方法律进行评估。

行业可能会根据HCP发证所在国的地方法律、法规及行业和职业行为守则,在特殊情况下提供价值不高的教育物品和/或礼品。排除在外的“教育”物品包括用于播放教学电影的DVD播放机,或用于伤口护理的摄像机,因为这些物品可用于其他用途。可接受的教育礼品可能是纯粹的教育(医学)书籍代金券、第三方活动或教育课程的登记证,不过仅将相关费用支付给第三方——不应向HCP直接支付任何现金。再次强调,必须完全透明,并提供涵盖双方的文件记录。

样品

行业可免费提供产品样品,以便HCP能评价和/或熟悉产品的安全性、有效性、适当用法和功能。这将便于HCP决定是否在将来或在将来的何时使用、订购、购买、开处或推荐产品和/或服务。样品的提供不得形成不正当的奖励、诱导和/或鼓励,从而促使HCP购买、租赁、推荐、开处、使用、供应或采购产品或服务。

样品的提供/供应应始终完全遵守适用的国家法律、法规、行业和职业行为守则。

最近,美国和欧洲法律及欧盟MedTech指南7均要求对提供给HCP的样品维护适当记录,例如样品交付的记录证明。目前这些样品应以免费形式明确记录在册,此外还必须在供应给HCP时以书面形式向HCP明确披露针对样品供应的该条件及其他适用条件。

问题在于,过量供应样品(倾销)可能被视为对于使用特定产品的诱导手段。样品,如字面意思,应该是少量的。据传闻,在造口行业,许多机构似乎存在产品供应过量(囤积)的问题,而非这些机构购买过量。这一做法可能需要进一步调查。

危险信号——警告

HCP在考虑在多个事项上与行业互动往来时,应熟悉这些事项。某些常见的“危险信号”应该引起HCP的警惕,包括以下情况:

- 存在“获胜”、“礼品”或“奖品”之类的用词或表达。

- 所得利益不涉及专业教育关系。

- 存在娱乐活动。

- 仅由行业制造商(无第三方)评判的“比赛”投稿。

- 价值高于需做出的工作。

- 存在似乎是“天上掉馅饼”的事情。

- 过量供应产品样品(倾销)。

保护HCP的一般经验法则

- 了解与器械制造商往来的全部规则。

- 与现工作单位的审计委员会/管理人员共同审核。

- 与地方和国家级的专业机构核实确认。

- 查阅所有可用的地方、国家或机构指南。

- 如有疑问,不要采取任何行动。

- 考虑“曝光”——如果这种互动往来出现在新闻中,人们会怎么看?这是廉洁且不会造成潜在误解的行为吗?

结论

HCP与行业往来时存在风险,规则和法律也在不断改变。很难及时获知不断发生的这些变化;但是,本文旨在提高相关人员对这种不断变化的环境的意识。对于HCP,明智的做法是确认和遵守往来互动的规则,观察危险信号,如果存在任何疑问,小心为上,不往来即可。各方的最终目标是改善患者结果,在合规的前提下形成繁荣发展的动态环境。行业与HCP之间的互动往来是不可避免的,但如果他们之间的关系是开放、诚信和透明的,并有明确的往来与监督规则,各方都可以从这种关系中获益颇丰。

免责声明

监管机构的法律频繁更新。截至印刷时,这只是对当前规范的合理推测。一如既往,在采取行动前如有任何疑问,建议向HCP的地方监管机构或工作单位寻求进一步指导。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Paris Purnell

Senior Manager, Clinical Education

Hollister Incorporated, Illinois, USA

Email paris.purnell@hollister.com

References

- Advanced Medical Technology Association. AdvaMed code of ethics on interactions with U.S. health care professionals [Internet]. Washington: Advanced Medical Technology Association 2018 [cited 2019 July 1]. Available from: https://www.advamed.org/sites/default/files/resource/advamed_u.s._code_of_ethics_final_-_eff._jan_1_2020.pdf

- Advanced Medical Technology Association. AdvaMed code of ethics on interactions with Chinese health care professionals [Internet]. Washington: Advanced Medical Technology Association 2018 [cited 2019 July 1]. Available from: https://www.advamed.org/sites/default/files/resource/revised_china_code_language_-_english_final.pdf

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. Code of conduct for nurses [Internet]. Melbourne: Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2018 [cited 2019 Sept 4]. Available from: https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Statements/Professional-standards.aspx

- Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. WOCN code of conduct and conflict of interest disclosure statement [Internet]. Mount Laurel, NJ: WOCN 2019 [cited 2019 Sept 4]. Available from: https://app.smartsheet.com/b/form/28f0d3b7212348daac48bb8f35def327

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists. The WCET mission, vision, values statement [Internet]. Washington: WCET 2018 [cited 2019 Sept 4]. Available from: https://www.wcetn.org/mission-values-a-vision

- Medical Technology Association of Australia. Code of practice E10 [Internet]. Sydney: Medical Technology Association of Australia 2018 [cited 2019 July 1]. Available from: https://www.mtaa.org.au/code-of-practice

- MedTech Europe. Code of ethical business practice: open letter to the healthcare community [Internet]. From the Legal and Compliance team of MedTech Europe. MedTech Europe 2017 [cited 2019 July 1]. Available from: http://www.medtechviews.eu/article/code-ethical-business-practice-open-letter-healthcare-community?

- Transparency International. Corruption perceptions index 2017 [Internet]. Berlin: Transparency International 2018 [cited 2019 July 1]. When published, the URL was transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017 but is now (in 2024) https://ca.edubirdie.com/blog/corruption-perceptions-index