Volume 39 Number 4

Patient-centred health educational intervention to empower preventative diabetic foot self-care

Meryl Makiling and Hiske Smart

Keywords Diabetes, Foot care education, prevention, toenail cutting

For referencing Makiling M & Smart H. Patient-centred health educational intervention to empower preventative diabetic foot self-care. WCET® Journal 2019;39(4):32-40

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.4.32-40

Abstract

Introduction Diabetes is a disease in which the body’s ability to produce or respond to the hormone insulin is impaired, resulting in abnormal metabolism of carbohydrates and elevated levels of glucose in the body. Due to these factors, diabetes can cause several complications that include heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, eye complications, kidney disease, skin complications, vascular disease, nerve damage and foot problems.

Aim The primary objective of the project was to educate patients who had been diagnosed with diabetes or were being followed up for diabetes management by other departments with regard to their own responsibility in maintaining preventative foot self-care. Educating patients with diabetes to take an active part in their own self-care is the cornerstone of establishing effective diabetes self-management. Diabetes education allows patients to explore effective interventions into living their life with diabetes and incorporate the necessary changes to improve their lifestyle.

Method Ten patients completed a validated educational foot care knowledge assessment pre-test to determine their existing knowledge about their own foot care after a thorough foot assessment. Preventative diabetic foot self-care education was conducted through a lecture, visual aids and a return demonstration. Patients were then subjected to a post-test questionnaire with the same content as the aforementioned pre-test to determine their uptake of the educational content.

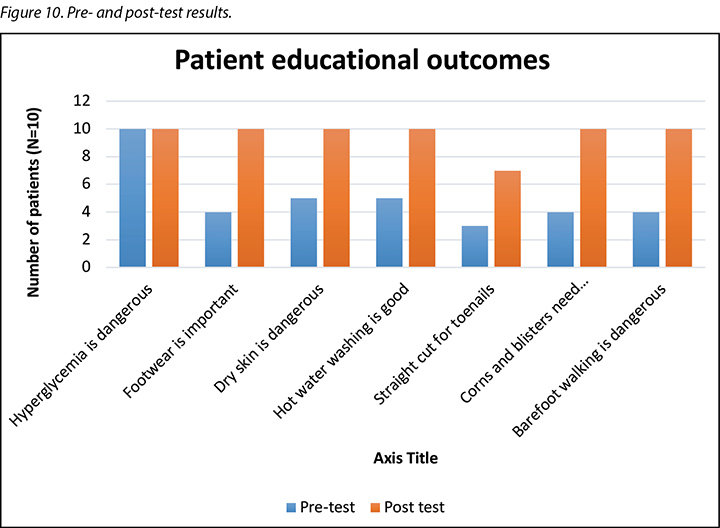

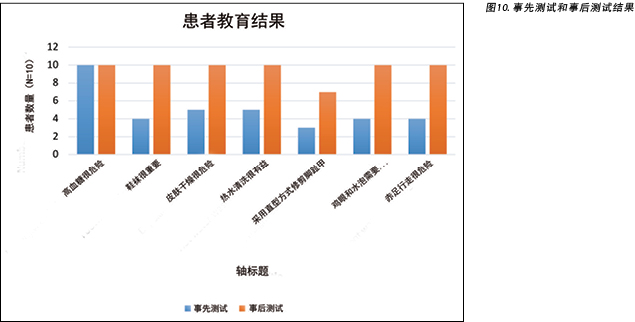

Results Correct cutting of toenails was the most identified educational need. It was a limitation in the pre-test (30%) and it remained the lowest scoring item on the post-test (70%). Walking barefoot was thought not to be dangerous by 60% of participants pre-test but, with remedial education, all participants identified this as a dangerous activity post-test. The importance of having corns and calluses looked after by a health professional rather than self-care was also understood to be of high importance.

Conclusion Effective communication with patients by healthcare providers who can mould educational content to the identified patient needs by teaching much needed skills is a key driver in rendering safe, quality-related healthcare educational interventions.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is one of the most prevalent major chronic disease burdens currently in the world, with a prevalence that has risen from 4.7% in 1980 to 8.5% in 20141, and which currently touches 422 million patients worldwide. It is expected to be the seventh most common cause of death in the world by 2030, primarily due to its rapid rise in middle- and low-income countries2. Diabetes has also been a leading cause of severe morbidities and disabilities1,2.

Diabetes is a disease in which the body has completely or partially lost its ability to produce or respond to the hormone insulin, resulting in abnormal metabolism of carbohydrates and elevated levels of glucose in the body. Due to these metabolic changes, diabetes is associated with several complications2 such as heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, eye complications, kidney disease, skin complications, vascular disease, nerve damage and foot problems. Foot problems can range from mild to major damage to the foot structure and are associated with a pathology pathway that can include damage to the vascular blood supply, soft tissues and resultant infection, all of which are magnified further by pressure and loss of protective sensation known as peripheral neuropathy3.

People affected with these foot pathologies have a higher risk of developing a diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) and associated infection; this then carries the risk for a lower limb amputation2,3. While some patients suffer from severe pain and discomfort in their feet – stinging, stabbing shooting, burning – others remain asymptomatic. However, having an insensate foot is the leading cause to unidentified complications of the foot in the early stages3. The incidence of non-traumatic lower extremity amputation is at least 15 times greater in those with diabetes than non-diabetes4, followed by a high incidence of death within 5 years thereafter5. In a 6-year follow-up study in Saudi Arabia, it was found that those persons with a DFU were more prone to be deceased within the study period than those followed up without a DFU present5. In the UAE there are more than 1 million people living with diabetes, ranking 15th worldwide for age-adjusted comparative prevalence6.

Educational interventions for persons with diabetes is therefore internationally accepted as a cornerstone of diabetes management and patient empowerment7. It creates the needed awareness to enable patients to take control of their own disease and make correct lifestyle decisions in order to control their disease process and resultant outcomes. Diabetes education allows patients to identify their own specific educational needs in order to create needs-based learning, a valuable adult learning concept that fosters increased adherence to living a normal life with a disease in accordance with best practice8. It also empowers them to make the necessary changes to improve their lifestyle and prevent complications. The best time for this kind of intervention is early in the disease process after being diagnosed with diabetes mellitus8,9.

In particular, patient education about basic foot care is important to reduce lower extremity complications5,6. Nurses working in vascular and podiatry clinics encounter patients with differing degrees of diabetic foot complications. Patients who attend these clinics may have been suffering with diabetes for years. The most common finding in our clinic is that patients are not educated nor empowered with the self-assessment methods to control their own disease and prevent complications in the early period just after initial diabetes diagnosis.

In addition, management of a DFU is expensive and, if compounded with wound infection or amputation, the cost escalates accordingly5,6. The duration of time to treat and save as much of a foot as possible once a DFU develops is lengthy and requires a multidisciplinary team approach to facilitate rehabilitation processes. However, if the development of DFUs, surgical intervention and amputation can be prevented with appropriate educational interventions, cost savings can be accomplished7, as well as improved quality of life outcomes. These interventions require a health professional with sufficient knowledge on diabetes management and prevention of complications with the ability to convey the most essential content in small bite-sized pieces in a short period of time. The education provided also requires regular follow-up with health professionals for monitoring uptake of lifestyle modifications and ongoing re-assessment to determine whether more education is required. Targeting patients at increased risk for developing a DFU is therefore believed to constitute a cost-effective strategy to control progression to end-stage foot complication and mechanical destruction8.

It can therefore be argued that the greatest weapon in the fight against diabetes mellitus complications is knowledge. Information can help people assess their risk of diabetes, motivate them to seek proper treatment and care earlier, and inspire them to take charge of their disease for their lifetime7,8. The preferred mode of teaching in this clinic setting due to the adult learning component need, as identified by the patients themselves10, is that of lectures accompanied by clinical demonstration. This method also accommodates the language barrier between care providers and patients in an appropriate manner11. Information given to patients shows them how to conduct their own foot inspection and apply treatment if needed, and this can be tested back simultaneously. This ensures that, once a patient is at home and in self-care, they are empowered with sufficient knowledge and skills to undertake any required foot care assessment interventions themselves.

Study Objective

The primary objective of the project was to educate patients who had been diagnosed with diabetes – or who are being followed up by another department such as internal medicine and endocrinology – with regard to the patient’s own responsibility in maintaining preventative foot self-care.

This was completed through evaluating any gaps in patients’ knowledge. Evaluation is a process that critically examines a program. It involves collecting and analysing information about a program’s activities, characteristics and outcomes that allows informed decisions to be made about a program in order to improve its effectiveness and/or to inform programming decisions8,9.

Methods

Patient recruitment and study inclusion criteria

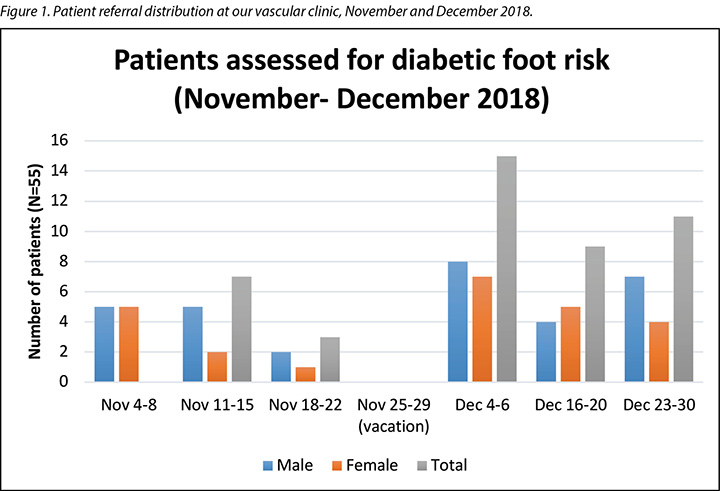

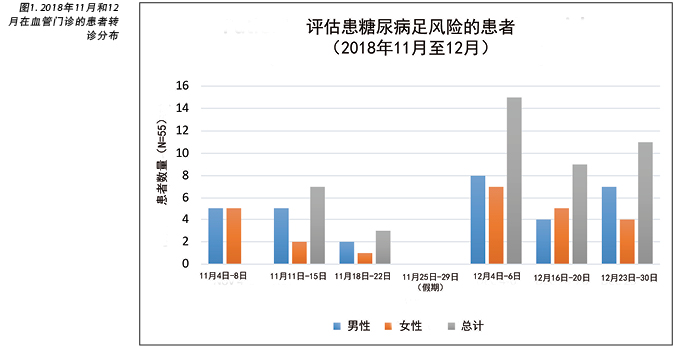

On average there are 20 new patients referred to our podiatry clinic for diabetic foot screening every month. Most of these patients already have foot-related symptoms such as numbness, tightness, burning and a tingling sensation which are signs of neuropathy. Most patients present with callus over bony prominences, corns and a dry plantar area indicative of the presence of peripheral neuropathy (see Figure 1).

The decision was made to recruit, include and group teach the first 10 patients in the clinic who met the following inclusion criteria:

- Be diagnosed with diabetes and be formally referred to the podiatry clinic for diabetes foot screening.

- Have the ability to speak and understand English as the materials were in English.

- Agree to be part of a confidential pre- and post-test educational foot care knowledge assessment.

- Be adults able to provide consent to participate.

Pre/post-test knowledge assessments

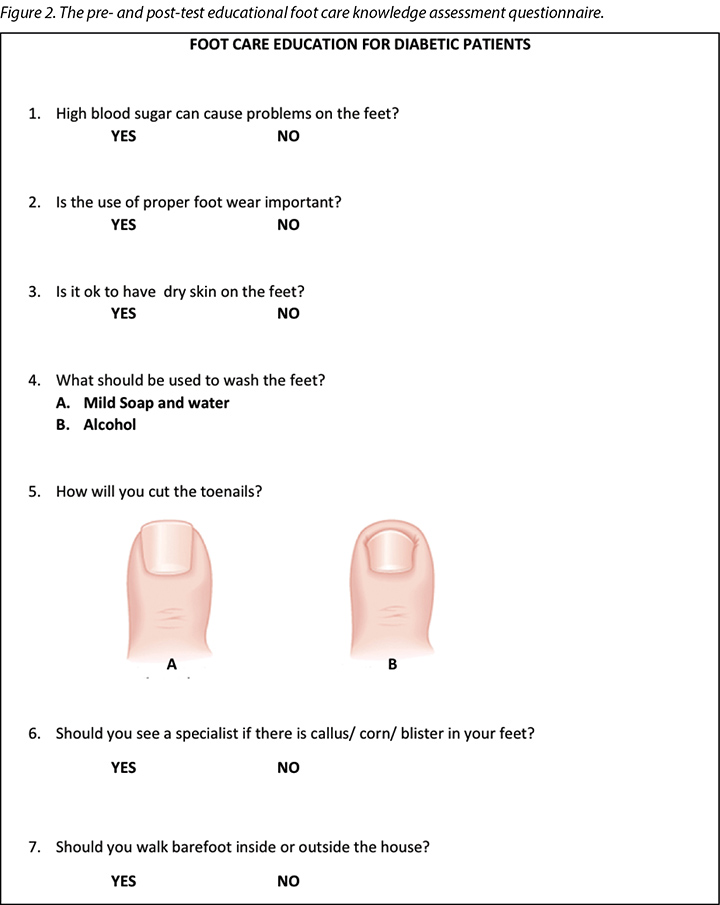

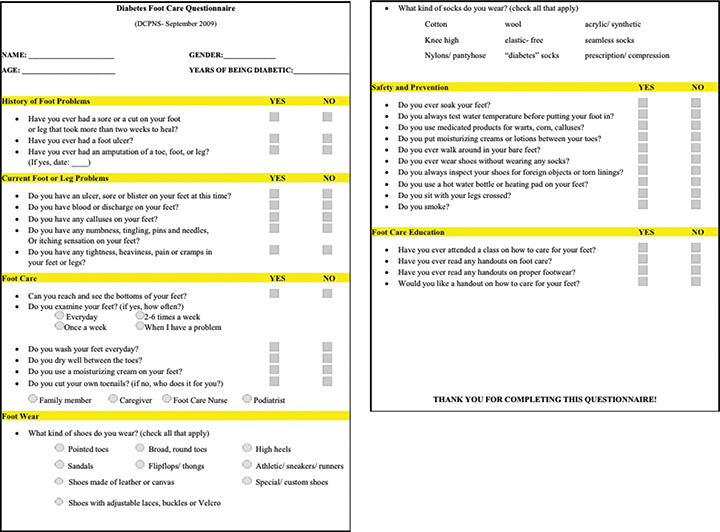

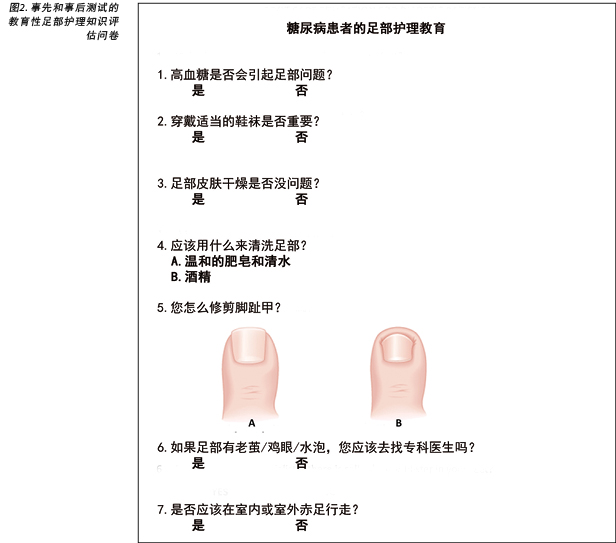

Assessment material used were based on the Diabetes Foot Care Questionnaire (Figure 2) and the Diabetic Foot Risk Assessment (Figure 3) from the Diabetes Care Program of Nova Scotia (DCPNS) 20098. The teaching plan and content were patterned on what the clinicians were normally teaching the patients when visiting the podiatry and vascular clinic.

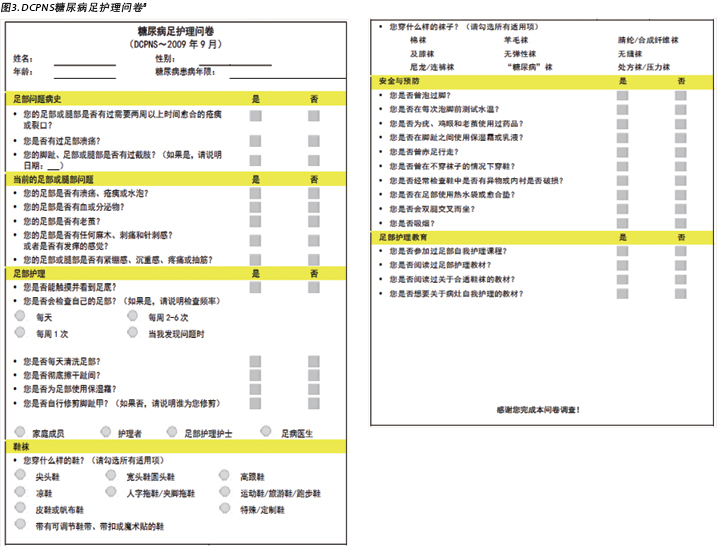

Figure 3. The DCPNS Diabetic Foot Care Questionnaire8.

Initially, nurses completed routine clinic assessments, including vital signs and history taking as well as a foot examination. Patients were then assessed with their knowledge regarding foot care by asking them to answer the DCPNS Diabetes Foot Care Questionnaire8 and to complete the pre-test educational foot care knowledge assessment (Figure 2).

Intervention: foot care education

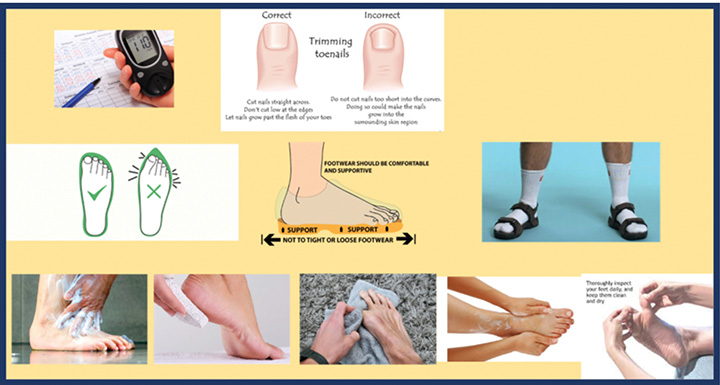

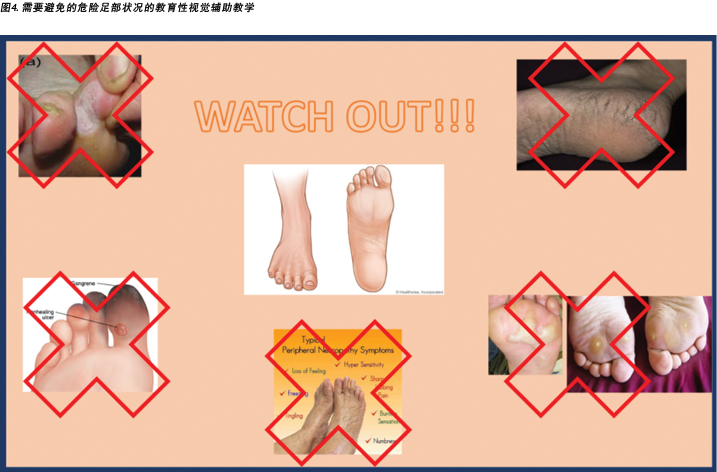

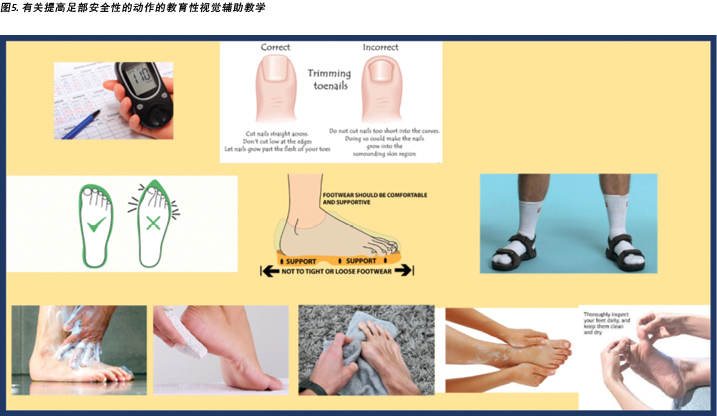

Foot care education was given through short lectures, discussions and visuals aids (some examples are shown in Figures 4 & 5). Educational content was associated with the activities of daily living of the patient to make it more doable and realistic. Patients’ and family members’ questions were then answered and, to measure the uptake of taught knowledge, patients then completed the post-test educational foot care knowledge assessment which had the same content as the pre-test (Figure 2). The entire education process took about 10–15 minutes. All assessments were manually recorded in the patients’ notes folders.

Figure 4. Educational teaching visual aid on risky foot conditions that need to be avoided.

Figure 5. Educational teaching visual aid on actions that add to foot safety.

Results

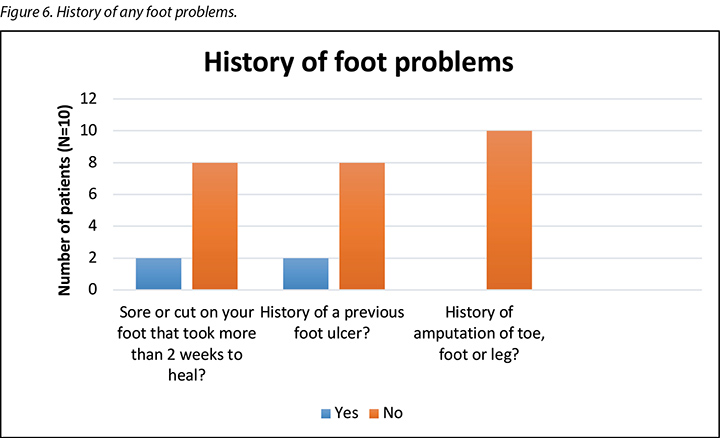

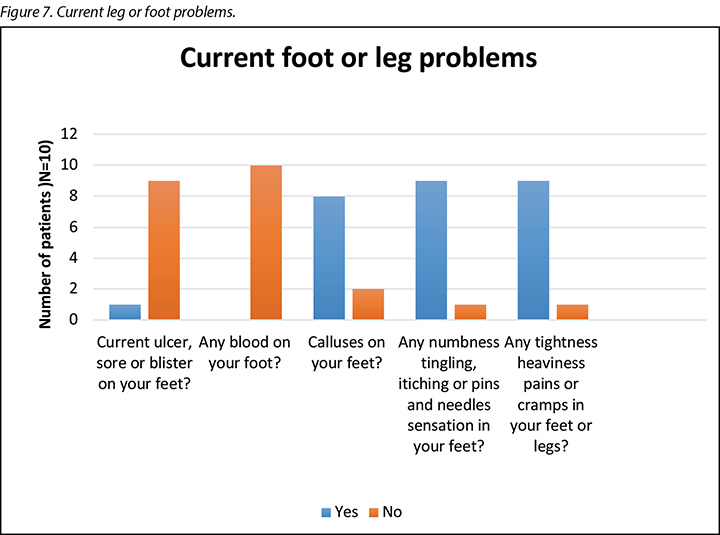

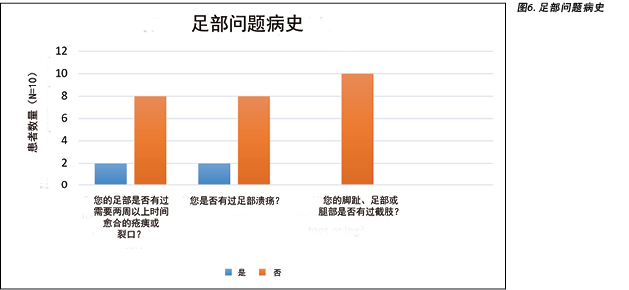

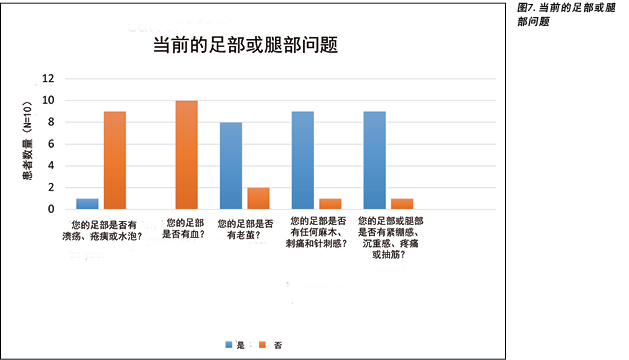

Based on the selection criteria described above, 10 patients were selected to be assessed and educated in this group learning session. Of these patients, six were male and four were female. Age range was from 40–70 years old. The foot examination revealed one patient with an existing DFU, two who had previous ulcers on their legs that took more than 2 weeks to heal, and one person with a previous DFU that had healed (Figure 6). The majority of the patients showed signs of neuropathy – numbness, tightness, burning and a tingling sensation – and dry plantar areas (90%). Callus over bony prominences and corns were present in 80% of the patients examined (Figure 7).

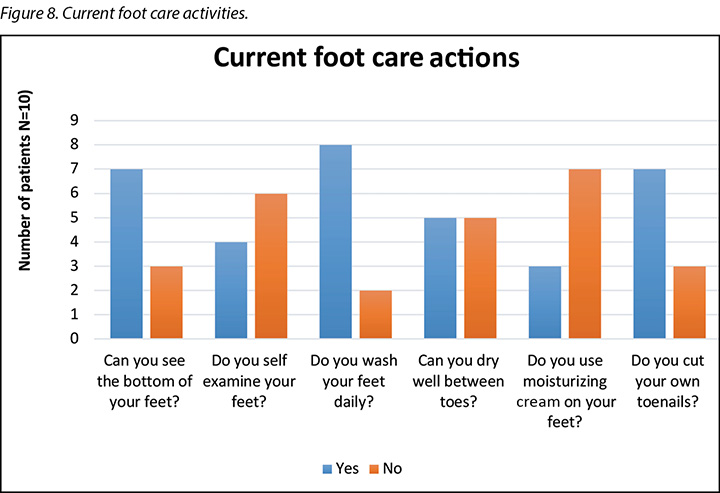

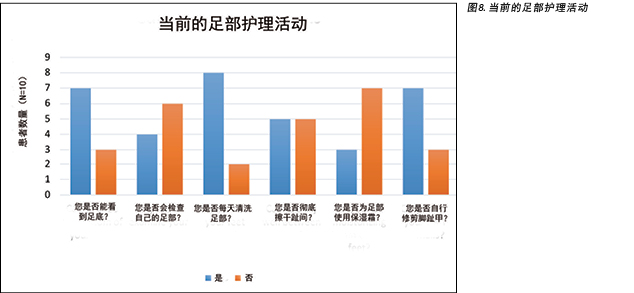

With regard to patients’ current foot care activities, their current self-management of foot care seemed to be inadequate, with 30% of participants unable to see the sole of their foot (Figure 8). Furthermore, 20% admitted they did not wash their feet every day and 50% complained that it was difficult to clean between their toes and make sure the skin was dry after washing their feet. The use of moisturiser during foot care was not popular, with 70% of participants identifying they did not routinely moisturise their feet. In addition, despite 30% of participants stating they could not see the bottom of their own feet, 70% of patients cut their own toenails.

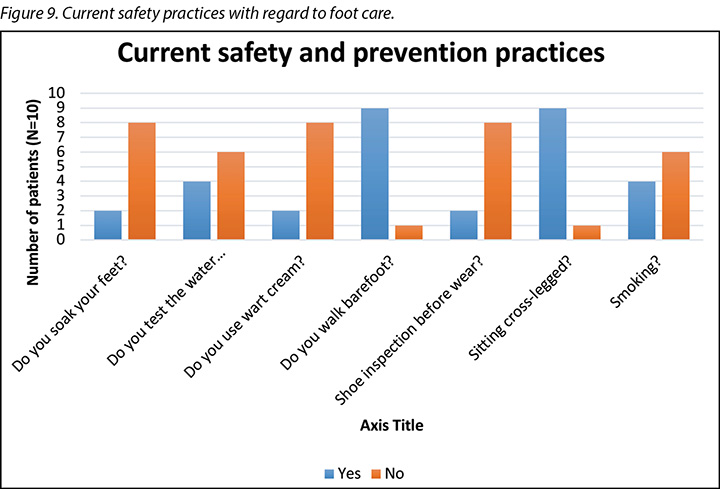

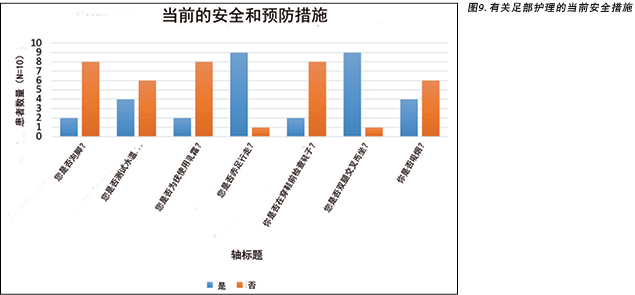

With regard to patients’ current safety practices with regard to foot care, the practice of wearing open-toed and open-heeled sandals or shoes was prevalent in 60% of patients. Within this patient sample, 90% (n=9) admitted to walking barefoot more often than wearing a shoe when inside the house as well as sitting cross legged on the floor on pillows (Figure 10).

When comparing the differences in the results between the pre- and post-tests, a number of issues were noted (Figure 10). Correct cutting of toenails was identified as a knowledge deficit in the pre-test (30%), and it remained the lowest scoring item post-test as only 70% of participants agreed they would use a straight cut when cutting their toenails. In the pre-test, 90% of participants indicated they went barefoot and only 40% indicated they understood that walking barefoot was dangerous. However, post-test, all participants indicated they understood walking barefoot to be dangerous.

None of the patients had had any prior foot education before the study commenced and only one participant had searched the internet to find a bit of information on his own with regard to foot care and foot wear. After taking the pre-test, it was revealed that most of the patients were in need of specific education and skills related to their own foot care.

Discussion

Diabetes is one of the rapidly rising causes of mortality worldwide. It has a greater incidence of non-traumatic lower extremity amputation than any other chronic disease in the world. Due to this, patients with diabetes need to be educated on how to properly take care of their feet. By providing group-based educational intervention sessions, the needs of many patients can be directly identified and addressed7,8.

During the education session, visuals (Figures 4 & 5) were provided to each patient and their family to assist them to understand the messages provided in the lectures and discussions. This assisted to alleviate any language barriers that potentially existed between the patient and the educator as patients could adapt translation of concepts not fully understood initially to the visual descriptors and clinical demonstrations provided11. Time was taken to answer all participants’ questions during group discussions so all could learn through the questions asked, responses and experiences of other patients in similar situations. Family members, if present, were also involved in the teaching sessions, although they did not take the pre- and post-test in order to help in reinforcing the retention of taught information for the patients.

The most important finding of this study relates to toenail cutting. Despite the fact that patients verbalised their difficulty in being able to see their own plantar aspect of the foot, they still cut their own toenails. It was a limitation in the pre-test (30%), and it remained the lowest scoring item post-test (70%) (Figure 10). With the majority of participants having peripheral neuropathy, the cutting of toenails without sufficient vision, on a foot that has loss of protective sensation, increases the risk for a traumatic injury with far reaching consequences3,4,5.

Toenails should preferably be cut after a bath or shower when nails are soft and clean, otherwise this can lead to infection and foot ulceration if they are not trimmed in a straight line when clean. Diabetics in particular should avoid cutting into the corners of toenails to avoid the development of ingrown toenails which can lead to infection and foot ulceration12. By implementing the elements identified in the DESMOND study7,8 – namely by initiating early teaching interventions that are fully adopted by patients with the needed lifestyle adaptations – this risk factor should be mitigated effectively. Furthermore, toenail clipping should be taught as a skill to both patients and their immediate caregiver/family circle as this skill is generally poorly executed yet it creates a huge risk burden towards lower limb loss.

In addition, patients in West Asian and Arabic regions have lifestyle habits that may add to their risk for developing a DFU later in the diabetes disease process. This includes the use of open-toed and open-heeled slip-on type of footwear that is very traditional in the region. Furthermore, the traditional practice in these regions is to be barefoot inside the house and to leave the shoes at the front door. The current study group were observed demonstrating some of these practices by simply wearing this type of footwear when they attended the clinic.

Walking barefoot was of initial concern in the pre-test result as 90% indicated they went barefoot (Figure 10). This concern was alleviated somewhat by participants stating in the pre-test they understood walking barefoot to be dangerous. This view was confirmed in the post-test when all participants identified they understood walking barefoot to be dangerous. However, in practice, walking barefoot in houses is a habit that would be very hard to address as it is family mandated. Sufficient time during education sessions to address this issue of wearing footwear in the house is therefore vital for situations where bony prominences or foot deformities are problematic as those will be the areas subjected to skin breakdown if not off-loaded sufficiently with an off-the-shelf or custom-made offloading device or inner sole that has to be positioned within shoe. This issue was easily corrected with the educational intervention, as was the importance of having corns and calluses looked after by a professional person rather than to try and do self-care (Figure 10).

In summary, patients may be reluctant at first to accept this kind of information but, with proper explanation and better understanding, self-assessment and foot care skills can be taught. Effective communication with patients and healthcare providers is a key process in safe and quality healthcare11. This is applicable specifically in the West Asian region where most of the healthcare workers are expatriates whereas patients are first language Arabic speakers with limited proficiency in English. As such, group teaching and a demonstration style of intervention followed by patient feedback demonstrations has proven itself effective to overcome many of these challenges and to establish trust despite major language differences.

Overall, post-test scores revealed participants had a better understanding of the importance of preventative foot assessments and skin care and had increased their ability to conduct their own foot self-care or in conjunction with a family member or carer. Sufficient retention of the knowledge content was achieved for all patients who participated in this study.

Conclusion

Involving patients in their own plan of care is an integral part of disease awareness and prevention of complications. Most of the patients in this study were not implementing the principles and practices of basic foot care (Figures 4 & 5) into their daily care routine; this was most likely due to being unaware of the gravity of complications that follows over the longer term.

Cultural practices play a vital role and will remain a challenge to address in the Western Asian/Arabic cultural environment. Lack of knowledge on the other hand, can be addressed within a patient-centred approach based on their own identified needs. Despite all the challenges, patient-centred health education remains the responsibility of healthcare providers within a proactive patient care approach. This can be accomplished by using every patient visit as an opportunity to provide specific educational interventions in order to ensure mastery of all skills related to foot self-care, most importantly toenail clipping, skin care, and the wearing of approved footwear to prevent DFUs.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

采取以患者为中心的健康教育干预措施,实现糖尿病足的预防性自我护理

Meryl Makiling and Hiske Smart

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.4.32-40

摘要

前言 糖尿病是一种疾病,可使人体产生或响应胰岛素的能力受损,导致碳水化合物的新陈代谢异常和体内葡萄糖水平升高。由于上述因素,糖尿病会引起多种并发症,包括心脏病、中风、高血压、眼部并发症、肾病、皮肤并发症、血管疾病、神经损伤和足部问题。

目的 本项目的主要目的是对已确诊糖尿病或正在其他科室接受糖尿病管理随访的患者进行有关预防性足部自我护理的责任教育。教育糖尿病患者积极参与自我护理是建立有效的糖尿病自我管理的基石。糖尿病教育使患者能够在生活中探索有效的干预措施,并纳入必要的改变以改善其生活方式。

方法 10例患者完成了经验证的教育性足部护理知识评估,作为事先测试,以在彻底的足部评估后确定其有关自身足部护理的现有知识。通过讲座、视觉辅助工具和亲身示范进行了预防性糖尿病足自我护理教育。然后通过问卷调查对患者进行事后测试,其内容与上述事先测试相同,以确定他们对教育内容的接受程度。

结果 正确修剪脚趾甲是最明确的教育需求。在事先测试中,患者对其了解有限(30%),并且在事后测试中也是评分最低的项目(70%)。在事先测试中,60%的参与者认为赤足走路并不危险,但通过补习教育,所有参与者都在事后测试中将其视为危险活动。此外,患者意识到由专业医护人员而不是自我护理鸡眼和老茧的重要性。

结论 医疗护理提供者通过教授急需技能来使教育内容符合已确定的患者需求,并且与患者进行有效沟通,这是提供安全、高质量医疗护理教育干预措施的主要动力。

前言

2型糖尿病是目前世界上最流行的主要慢性疾病负担之一,其患病率已从1980年的4.7%上升到2014年的8.5%1,目前全球已有4.22亿患者。预计截至2030年,它将成为世界上第七大常见死亡原因,主要原因是其发病率在中等收入和低收入国家中迅速增长2。糖尿病也一直是导致严重病症和残疾的主要原因1,2。

糖尿病是一种疾病,可使人体产生或响应胰岛素的能力完全或部分受损,导致碳水化合物的新陈代谢异常和体内葡萄糖水平升高。由于上述代谢变化,糖尿病会引起多种并发症2,包括心脏病、中风、高血压、眼部并发症、肾病、皮肤并发症、血管疾病、神经损伤和足部问题。足部问题的范围从轻微到严重足部结构损伤不等,并且与病理路径有关,其中包括对血管供血和软组织的损害,以及由此引起的感染,所有上述问题都会因压力和保护性感觉丧失(称为周围神经病)进一步放大3。

对于受此类足部病变影响的人,其罹患糖尿病足溃疡(DFU)和相关感染的风险更高; 从而产生下肢截肢的风险2,3。尽管有些患者会经历足部剧烈疼痛和不适(刺痛感、针刺感、灼烧感),但其他患者可能无症状。然而,足部无感觉是在早期阶段导致足部不明并发症的主要原因3。糖尿病患者的非创伤性下肢截肢率至少比非糖尿病患者高15倍4,其5年内死亡率较高5。一项在沙特阿拉伯进行的6年随访研究中,发现DFU患者比非DFU随访者更容易在研究期内死亡5。在阿联酋,有超过100万人患有糖尿病,按年龄调整后的相对患病率在全球排名第15位6。

因此,国际上已将糖尿病患者的教育干预措施视为糖尿病管理和患者赋权的基础7。它创造了必要的意识,使患者能够控制自己的疾病并做出正确的生活方式决定,从而控制他们的疾病进程和结果。糖尿病教育使患者能够确定自己的特殊教育需求,以创建基于需求的学习,这是一种有价值的成人学习概念,可根据最佳实践促进患者对正常生活的依从性8。它还使患者能够进行必要的改变,以改善自己的生活方式并防止并发症。此类干预的最佳时间是在确诊糖尿病之后的早期疾病进程8,9。

特别地,有关基础足部护理的患者教育对于减少下肢并发症至关重要5,6。在血管和足病门诊工作的护士会遇到不同程度的糖尿病足并发症患者。前往这些门诊的患者可能已经患糖尿病多年。在我们的门诊中,最常见的情况是,在初次糖尿病诊断后的早期阶段,患者没有接受自我评估方法的教育或授权,因而无法控制自己的疾病或预防并发症。

此外,DFU管理非常昂贵,如果还存在伤口感染或截肢,费用会相应地上升5,6。DFU形成后,治疗并尽可能挽救足部所需的时间很长,并且需要多学科的团队方法来促进康复过程。但是,如果通过适当的教育干预措施可以避免DFU、手术介入和截肢,则可以节省成本7,并改善生活质量结果。

这些干预措施要求专业医护人员充分了解糖尿病的管理和并发症的预防,并能够在短时间内以碎片形式传达最基本的内容。所提供的教育还需要专业医护人员定期随访,以监测患者对生活方式改变的接受程度,并持续进行重新评估以确定是否需要更多的教育。因此,以DFU高风险患者作为目标是一种控制晚期足部并发症进展和机械性破坏的经济、有效策略8。

因此可以说,对抗糖尿病并发症的最强武器是知识。信息可以帮助人们评估其患糖尿病的风险,激发他们及早寻求适当的治疗和护理,并激发他们在一生中对自己的疾病负责7,8。如患者自身所述,由于成人学习的需要,在该门诊环境中的优选教学模式是讲座加临床示范10。这种方法还通过适当的方式解决了护理提供者和患者之间的语言障碍11。提供给患者的信息告知其如何进行自我足部检查,并在需要时进行治疗,并且可以同时进行测试。这样可以确保患者在家中进行自我护理时,可获得足够的知识和技能来进行任何必要的足部护理评估干预措施。

研究目标

本项目的主要目的是对已确诊糖尿病或正在其他科室(例如内科和内分泌科)接受随访的患者进行有关预防性足部自我护理的责任教育。

本项目通过评价患者知识方面的差距完成。评价一个是严格审查程序的过程。它涉及收集和分析有关程序活动、特征和结果的信息,这些信息有助于针对该程序做出明智的决定,以提高其有效性和/或为程序决策提供参考8,9。

方法

患者招募和研究纳入标准

平均每个月有20例新患者转诊到我们的足病门诊接受糖尿病足筛查。这些患者大多数已经具有足部相关症状,例如麻木、紧绷、灼热和刺痛感,这是神经病变的征兆。大多数患者存在骨突出老茧、鸡眼和足底干燥等症状,表明存在周围神经病变(见图1)。

本研究决定在门诊中招募、纳入并分组教导符合以下纳入标准的前10例患者:

• 确诊糖尿病,并正式转诊至足病门诊进行糖尿病足筛查。

• 具备说和理解英语的能力,因为材料是英语版。

• 同意参加机密性事先和事后测试的教育性足部护理知识评估。

• 能够同意参加测试的成年人。

事先/事后测试的知识评估

使用的评估材料基于2009年新斯科舍省糖尿病护理计划(DCPNS)8的糖尿病足护理问卷(图2)和糖尿病足风险评估(图3)。教学计划和内容根据临床医生在患者拜访足病和血管门诊时对其进行的教学而定。

首先,由护士完成常规的临床评估,包括生命体征、病史以及足部检查。然后,要求患者回答DCPNS糖尿病足护理问卷8中的问题,并完成事先测试的教育性足部护理知识评估(图2),从而评估患者的足部护理知识。

干预:足部护理教育

通过简短的讲座、讨论和视觉辅助工具进行了足部护理教育(图4和图5提供了一些示例)。教育内容与患者的日常生活和活动相关联,使其更加切实可行。然后回答患者及其家庭成员的问题。为了衡量对所学知识的吸收程度,患者完成了与事先测试内容相同的事后测试教育性足部护理知识评估 (图2)。整个教育过程大约需要10-15分钟。所有评估均手动记录在患者的便笺文件夹中。

结果

根据上述纳入标准,选择了10例患者参与本组学习课程的评估和教育。在纳入的患者中,6例为男性,4例为女性。年龄范围是40-70岁。足部检查发现1例患者已有DFU,2例患者存在需要两周以上时间愈合的腿部溃疡,1例患者曾有过DFU,但现已愈合(图6)。大多数患者表现出神经病变的迹象(麻木、紧绷、灼热和刺痛感)和足底干燥(90%)。80%的受检患者存在骨突出老茧和鸡眼(图7)。

关于患者目前的足部护理活动,他们目前对足部护理的自我管理似乎不足,并且30%的参与者看不到足底(图8)。此外,20%的人承认自己没有每天清洗足部,50%的人抱怨难以清洁脚趾间,并在清洗足部后难以确保皮肤干燥。保湿霜在足部护理中的使用并不普遍,70%的参与者表示他们没有定期对足部进行保湿。此外,尽管30%的参与者表示自己看不到足底,但仍有70%的患者自行修剪脚趾甲。

关于患者目前在足部护理方面的安全实践,60%的患者普遍穿着露趾和脚跟的凉鞋或鞋子。在该患者样本中,有90%(n=9)的人承认在室内时赤足行走的频率高于穿鞋走动,以及在地板和坐垫上双腿交叉而坐的频率更高(图10)。

在比较事先测试和事后测试结果的差异时,注意到了许多问题(图10)。正确修剪脚趾甲是事先测试中患者所缺乏的知识(30%),并且仍然是事后测试中得分最低的项目,因为只有70%的参与者表示在修剪脚趾甲时将使用直型修剪方式。在事先测试中,90%的参与者表示他们会赤足行走,只有40%的参与者表示他们知道赤足行走很危险。但是,在事后测试中,所有参与者都表示他们知道赤足行走很危险。

在研究开始之前,所有患者均未接受过任何足部教育,只有一例参与者通过互联网搜索了有关足部护理和鞋袜相关的信息。经过事先测试后,发现大多数患者需要与足部自我护理相关的特殊教育和技能。

讨论

糖尿病是导致全世界死亡率快速上升的原因之一。与世界上任何其他慢性疾病相比,其非创伤性下肢截肢的发生率更高。因此,糖尿病患者需要接受如何正确护理足部的教育。通过提供基于小组的教育干预课程,可以直接确定和解决许多患者的需求7,8。

在教育期间,为每位患者及其家人提供了视觉辅助教育(图4和5),以帮助他们了解讲座和讨论中提供的信息。这有助于减轻患者和教育者之间可能存在的任何语言障碍,因为患者可以通过提供的视觉辅助和临床示范来理解最初未完全理解的概念11。在小组讨论中花时间回答所有参与者的问题,以便所有人都可以从所提出的问题、提供的回答和其他情况相似的患者经验中学习。尽管没有参加事先测试和事后测试,在场的家庭成员也参加了教学课程,以帮助加强患者对教学信息的学习。

本研究最重要的发现与修剪脚趾甲有关。尽管患者口头上表示自己难以看到足底,但他们仍然自行修剪脚趾甲。在事先测试中,患者对其了解有限(30%),并且在事后测试中也是评分最低的项目(70%)(图10)。由于大多数参与者存在周围神经病变,如果在无法看清的情况下修剪保护性感觉丧失足的脚趾甲,则会导致外伤风险增加, 其后果影响深远3,4,5。

最好在洗澡或淋浴后,趁脚趾甲柔软干净的时候进行修剪,否则,如果在清洁时未将它们整齐地修剪为直型,可能会导致感染和足部溃疡。糖尿病患者尤其应避免修剪脚趾甲的边角处,以免趾甲内嵌导致感染和足部溃疡12。通过实施DESMOND研究7,8中确定的要素(即通过采取早期的教学干预措施,并由需要调整生活方式的患者完全采用该干预措施),可有效地减轻该风险因素。此外,应该将脚趾甲修剪作为一种技能,向患者及其直接护理者/家庭圈进行教授,因为这种技能的执行情况通常不佳,但会带来巨大的风险负担,甚至下肢截肢。

此外,西亚和阿拉伯地区的患者的生活习惯可能会增加他们在糖尿病疾病后期发展DFU的风险。这包括穿着该地区的传统露趾和露脚后跟的鞋。此外,该地区的传统是赤足进入屋内,并将鞋子留在前门。对当前的研究组进行观察后发现,有些患者在就诊时正好穿着此类鞋子。

在事先测试的结果中,赤足行走是最初关注的重点,因为90%的人表示自己会赤足行走(图10)。由于参与者在事先测试中表示自己知道赤足走路很危险,因此该问题的关注得到缓解。该观点在事后测试中得到确证,此时所有参与者都认为赤足走路很危险。但是,在实际生活中,在室内赤足行走已经成为习惯,由于家庭的强制要求,因此很难解决。因此,在教育课程中应预留足够的时间来解决在室内穿鞋袜的问题,这对于骨突出或足部畸形的情况至关重要,因为如果患者不穿着带有市售或定制减压装置或内底的鞋,则这些区域可能会出现皮肤皲裂。通过教育干预可以很容易地纠正这个问题,由专业人员来处理鸡眼和老茧而不是尝试自我护理也至关重要(图10)。

总而言之,患者起初可能不愿接受此类信息,但是通过适当的解释和更好的理解,可以向其教授自我评估和足部护理技巧。与患者和医疗护理提供者的有效沟通是提供安全和高质量医疗护理的关键过程11。这特别适用于西亚地区,因为该地区的大多数医护人员都是外籍人士,而患者的母语为阿拉伯语,英语水平有限。因此,经证明,小组教学和示范干预方式以及随后的患者反馈示范可以有效克服许多挑战,并且在存在主要语言差异的情况也可以建立信任。

总体而言,事后测试分数表明,参与者对预防性足部评估和皮肤护理的重要性有了更好的了解,并且增强了自己进行足部自我护理或与家人或护理人员一起进行自我护理的能力。对于所有参加本研究的患者,都充分理解了相关的知识内容。

结论

让患者参与自己的护理计划是疾病意识和预防并发症的重要组成部分。本研究中的大多数患者并未在日常护理中应用基本足部护理的原理和实践(图4和图5);这很可能是由于他们没有意识到长期并发症的严重性。

文化习俗起着至关重要的作用,并将仍然是在西亚/阿拉伯文化环境中的一项挑战。另一方面,可以基于患者自己确定的需求,通过以患者为中心的方法来解决知识的缺乏。尽管存在很多挑战,但医疗护理提供者仍然有责任通过积极主动的患者护理方法,开展以患者为中心的健康教育。这可以通过在每次患者来访时,提供特定教育干预措施的机会来实现,以确保患者掌握与足部自我护理有关的所有技能,尤其是脚趾甲修剪、皮肤护理以及穿着经批准的鞋袜以防止DFU。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Meryl Makiling

RN

Staff Nurse, HVI-Podiatry Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Hiske Smart*

Clinical Nurse Specialist, King Hamad University Hospital, Busaiteen, Kingdom of Bahrain

Email hiskesmart@gmail.com

* Corresponding author

References

- World Health Organization. Diabetes fact sheet [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes.

- Fox CS, Hill Golden S, Anderson C, Bray GA, et al. Update on prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in light of recent evidence: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015;38(9):1777–1803.

- Sibbald RG, Goodman L, Woo KY, Krasner DL, Smart H, Tariq G et al. Special considerations in wound bed preparation: an update. Adv Skin Wound Care 2011;24(6):415–436.

- Narres M, Kvitkina T, Claessen H, Droste S, Schuster B, Morbach S, et al. Incidence of lower extremity amputations in the diabetic compared with the non-diabetic population: a systematic review. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017 Aug;12(8):e0182081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182081.

- Al-Rubeaan K, Almashouq MK, Youssef AM, Al-Qumaidi H, Al Derwish M, Ouizi S, et al. All-cause mortality among diabetic foot patients and related risk factors in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2017;12(11):e0188097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188097

- Jelinek H. Clinical profiles, comorbidities and complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus in patients from United Arab Emirates. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care [Internet]. 2017 Aug;5(1):e000427. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000427.

- Gillett M, Dallosso HM, Dixon S, Brennan A, Carey ME, et al. Delivering the diabetes education and self-management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2010,341:c4093.

- Skinner TC, Carey ME, Cradock S, Dallosso HM, Daly H et al. on behalf of the DESMOND Collaborative. ‘Educator talk’ and patient change: some insights from the DESMOND (Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed) randomized controlled trial. Diabetic Med 2008;25:1117–1120.

- Kalayou KB. Assessment of diabetes knowledge and its associated factors among type 2 diabetic patients in Mekelle and Ayder Referral Hospitals, Ethiopia. J Diabetes Metabol 2014;5(378).

- Steinsbekk A, Rygg LØ, Lisulo M, Rise MB, Fretheim A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:213.

- Khalid A. Culture and language differences as a barrier to provision of quality care by the health workforce in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2015;36(4):425–431.

- The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. IWGDF guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease. IWGDF; 2019