Volume 40 Number 1

Application of a convex appliance to restore peristomal skin integrity: a case study

Fengzhi Yan and Mengxiao Jiang

Keywords ileostomy, faecal dermatitis, convex appliance

For referencing Yan F and Jiang M. Application of a convex appliance to restore peristomal skin integrity: a case study. WCET® Journal 2020;40(1):10-17

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.1.10-17

Abstract

This case study describes the nursing management of one case of irritant contact dermatitis from faecal fluid around the peristomal skin of a patient with an ileostomy who presented to the outpatient department 1 month postoperatively. This postoperative complication occurred as a result of the stoma being located within wrinkles in the abdomen, causing the appliance to leak and skin ulceration to develop, which prevented firm adherence of the appliance base plate to the peristomal skin. Furthermore, the patient was very anxious as a result of these complications. In this patient’s case, the initial goals were to assess and address the peristomal skin complications, provide an appliance with convexity that could be fixed with a belt to stabilise the appliance as early as possible, and finally commence strengthening psychological counselling and dietary guidance for the patient and her family. These nursing interventions were found to reduce the incidence of faecal dermatitis complications around the stoma, improve the patient’s quality of life and thus worth applying.

Introduction

The ileum stoma is a small intestine stoma and sometimes it is an indispensable surgical procedure for certain colorectal diseases such as rectal cancer and other conditions such as inflammatory bowel diseases, diverticular disease, radiation enteritis, abdominal trauma and intestinal obstruction1–3. The ileum stoma or ileostomy is generally located in the lower right quadrant or side of the abdomen.

Peristomal skin complications occur frequently following ostomy surgery with prevalence reportedly ranging from 10–70%4,5. Postoperatively within the first year of ostomy surgery the incidence of all forms of peristomal skin damage reportedly range from 15–43%6,7. It is suggested peristomal skin conditions account for over 40% of visits to enterostomal therapy nurses (ET nurses). Faecal dermatitis is one of the more common early complications after ileostomy surgery, with one study of 220 new ostomy patients identifying a rate of 69%8.

Definition, cause and management strategy of faecal dermatitis

Faecal dermatitis is caused by the frequent contact of faecal fluid containing digestive enzymes eroding the skin around the stoma9. Latterly the term peristomal moisture-associated dermatitis (MASD) has also been defined as inflammation and denudation of skin adjacent to a stoma associated with exposure to effluent, such as urine or stool10,11. Initially contact irritant dermatitis may present as reddened skin which, with continued contact with effluent, may blister or become denuded. The pattern of skin loss reflects the areas where leakage of faecal material has occurred12,13.

Faecal material contains proteolytic and lipolytic enzymes postulated to damage both protein and lipid-based elements of the skin’s epithelial (and moisture) barrier. Effluent from an ileostomy is typically more liquid in nature than effluent from a colostomy and contains abundant digestive enzymes. The consistency of faecal discharge from an ileostomy depends on the location of the stoma within the ileum. The ileostomy output may be fluid or viscous (mushy) in consistency. Faecal discharge that is more liquid occurs when the stoma is located closer to the stomach and therefore contains more digestive enzymes.

Tissue that is constantly damaged in the healing process by friction, shear and corrosive substances results in mucosal damage, inflammatory changes, tissue cell proliferation and the development of granulomas. Ostomy mucosa granulomas are raised benign lesions that usually occur where the mucous membrane is joined to the skin or occurs on the stoma mucosa itself. One or more granulomas may grow around the edge of the stoma. Ostomy mucosal granulomas not only cause pain and itching, they are very fragile and prone to bleeding which affects adhesion of the ostomy bag, and which may cause leakage and lead to dermatitis around the stoma.

Further, the often-unbearable pain from faecal dermatitis and continued leakage of the ostomy bag significantly affects the patient’s quality of life and early rehabilitation which can have serious long-term physiological and psychological effects on the patient14.

Convexity in stoma care

In a cross-sectional descriptive quantitative survey in the United States of wound, ostomy and continence nurses, 281 respondents ranked the management of complications of stoma and surrounding skin. Among the management strategies for peristomal irritant contact dermatitis, which was defined as, “Damage resulting from skin exposure to faecal or urinary drainage or chemical preparations”15, the use of convex appliances, pastes, barrier rings, powders and belts were described. The importance of determining the aetiology of contact dermatitis was also discussed.

Current evidence-based practice endorsed by international experts advocates the application of convexity via convex appliances and accessories in the management of certain peristomal complications. They recommend filling in the depressions made by abdominal contours, skin folds and wrinkles with convex appliances or seals which facilitates protrudence of stomas and flattening out of abdominal folds or skin creases, thereby improving adherence of the appliance and lessening of leakages16,17.

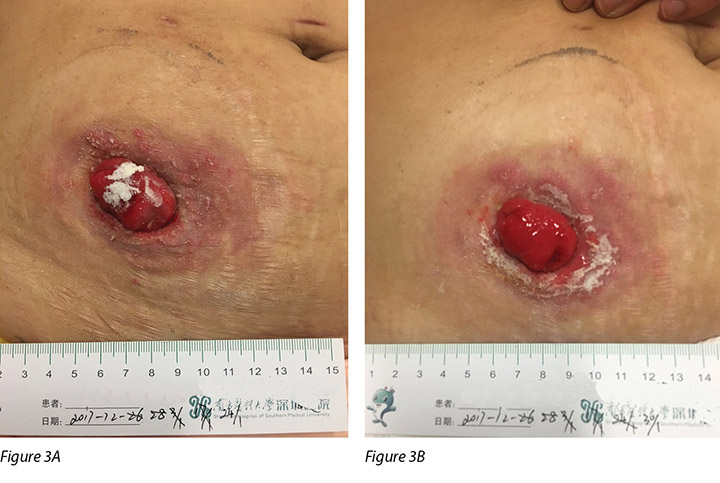

The Ostomy Skin Tool (OST) assists ET nurses to be able to objectively quantify peristomal skin damage in terms of discolouration (D), erosion (E) and tissue (T) and to relate these changes to other health professionals to ensure consistency of understanding and management of peristomal skin damage Each parameter of DET is scored for the size of the area affected (between 0 and 3) and the severity of skin damage (between 0 and 2), with each of three categories potentially reaching a score between 0 and 5. The overall score range is between 0 and 15, where 0 represents normal skin and 15 signifies the highest amalgamation of severity and extent18.

A numerical rating scale (NRS) represents the pain degree, with 11 numbers from 0 to 10; 0 means no pain and 10 means the most pain. Subjects were marked with one of the numbers according to their personal experience of pain19.

This article describes the clinical care provided in one case of faecal peristomal skin dermatitis and discusses the rationale for the application of convexity technology in minimising the adverse effect of skin wrinkles near the stoma.

Case Study

Patient overview

A female patient, 42 years old, underwent elective radical resection of her colon because of rectal cancer and an ileostomy was performed on 30 November 2017. Her stoma was not sited preoperatively. After the operation, postoperative education on the management of her stoma and wound was provided. While the patient had the right to independently choose her ostomy appliance, the ostomy product was selected by the hospital ostomy assistant. A two-piece flat base plate was chosen and the patient was scheduled to receive targeted chemotherapy, starting about 3 months later. Targeted therapy drugs are theoretically precision-guided drugs that deliver precise strikes on tumour cells with little damage to normal cells cured.

Assessment of the patient, stoma and peristomal skin

On the first visit to the Outpatient Clinic on 26 December, 1 month post-surgery, the patient was wearing a two-piece ostomy product with a flat base plate. The patient reported severe leakages had been occurring. On assessment, the reason for the leakages around the stoma became apparent.

The ileostomy stoma was located within a large abdominal crease. The stoma protruded just 0.6cm above the level of the peristomal skin. The main problem was the wrinkles on the abdomen, which had loosened the adhesion of the base plate, thus leading to the appliance leaking. The peristomal skin was severely ulcerated on both lateral sides of the stoma with evidence of hyper-granulation. Multiple bleeding points (>50% of the area) were evident around the stoma (see Figure 1A). The patient complained of a burning pain within the peristomal skin. Green coloured thin faeces exuded from the stoma and lay on the peristomal skin. Assessment of skin integrity using the OST was 10 and her digital pain score was 8 points (see Tables 1 & 2). The patient’s abdomen was soft on palpation.

Figure 1A

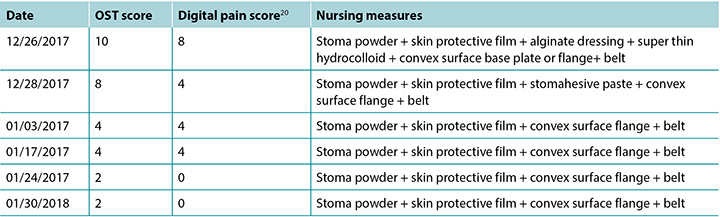

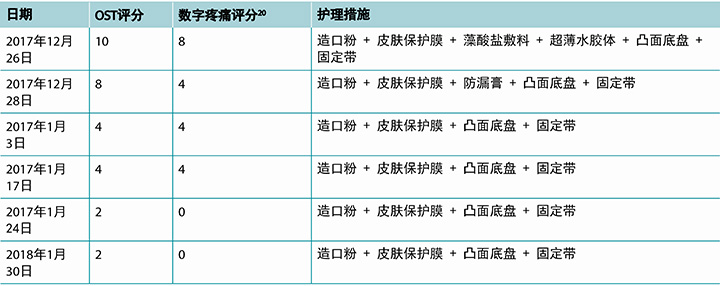

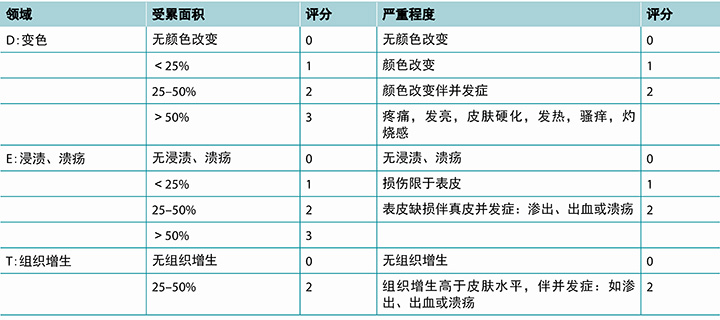

Table 1. The OST score and nursing measures

Table 2. OST DET score

The patient was very anxious, agitated at times and in pain particularly around the stoma. The faecal leakage was causing malodour. She was lethargic and lacked appetite and complained of weight loss of 6kg. Her body mass index (BMI) was 27.4. Her haemoglobin was low and she had pallid eyelids.

As the patient was wearing a flat base on discharge from hospital, the same ostomy appliance was replaced after cleaning the stoma and skin with normal saline, the application of stomahesive powder, skin sealant, stomahesive paste and a belt (see Figure 1B). Unfortunately, approximately 3 hours after the patient returned home the appliance leaked (see Figures 1C & 1D). The patient was requested to change the appliance and use the alternative convex base plate she had been supplied with during the outpatient visit.

Figure 1B

Interventions and stoma management plans

Stoma care and nursing procedures

According to the assessments undertaken, the main nursing problems that existed were: peri-ostomy complications, faecal dermatitis, pain and anxiety. The goals of care identified were to:

- Prevent leakage around the stoma by using suitable stoma care products.

- Promote skin healing around the stoma and reduce hypergranulation (hyperplasia) by using appropriate skin care and dressing products.

- Reduce the patient’s peristomal skin pain.

- Alleviate the patient’s level of anxiety.

- Prevent the development of clinical malnutrition.

- Reduce the ileostomy output to normal levels and consistency.

Dressing regimen and stoma appliance selection

The peristomal skin was ulcerated because of erosion of the skin by watery faeces with a high enzyme content. In order to prevent potential secondary infection, control bleeding and promote epithelial tissue growth, the following skin care and dressing regimen were implemented:

- The stoma and peristomal skin were thoroughly flushed with normal saline.

- Saline soaked gauze was used to repeatedly but gently wipe away residual loose necrotic tissue and residual faecal material.

- The area was dried with sterile gauze. Any bleeding points were lightly compressed with a saline swab, taking care not to damage the normal tissue of the stoma and peristomal skin while achieving haemostasis.

- Stoma powder was sprinkled on the skin around the stoma. Excess powder was removed after 5–10 minutes.

- The peristomal skin was then sprayed (sheet coating) with skin protection film. About 10 minutes later a bright film on the skin is formed.

- The above steps using Stomahesive powder were repeated 3 to 5 times.

- Where the skin was eroded the ulcerated areas were covered with an alginate dressing and ultra-thin hydrocolloid.

- Stomahesive paste was placed around the stoma before applying the convex base plate and belt to prevent leakage.

Observing the stoma, replacing the appliance and wound dressings

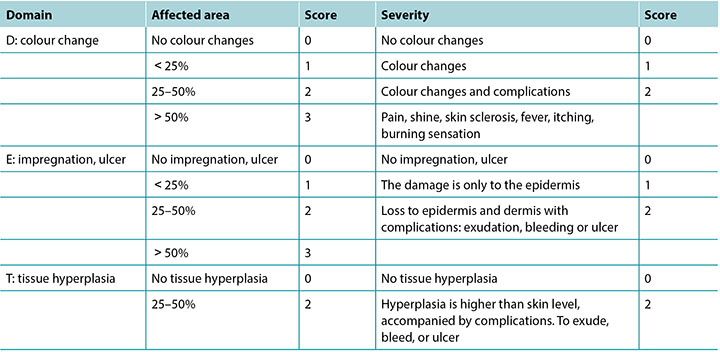

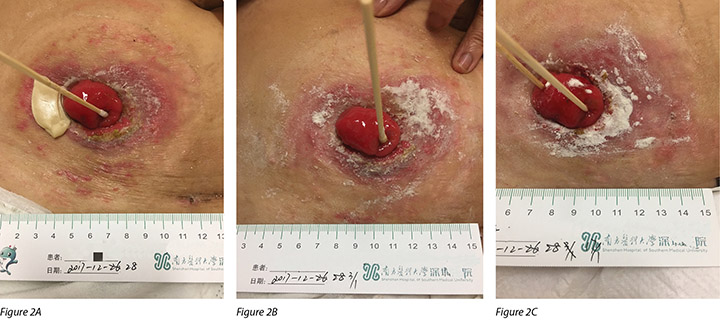

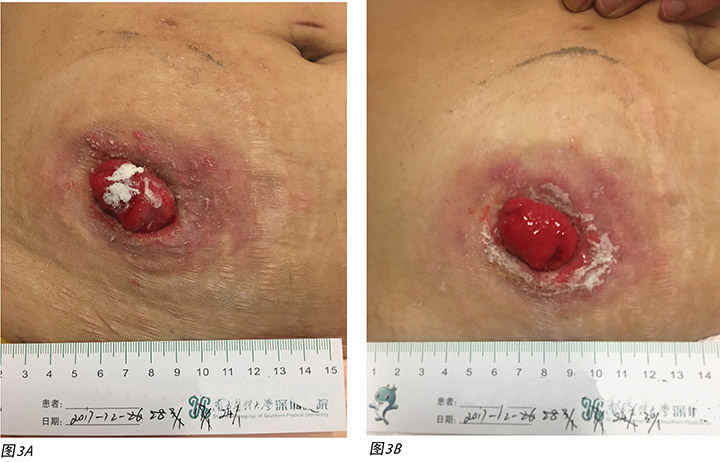

The patient’s ileostomy output was so watery that the patient was advised to rest in bed. To prevent any strain on the appliance while lying in bed and to prevent leakage, the patient was instructed that the opening of the ostomy bag should be toward the right side of the body and the faeces in the ostomy bag should be emptied regularly. The patient was also requested to daily observe the colour of the stoma and look for any bleeding and leakage around the stoma and replace the dressing and ostomy bag should there be any leakage. Generally, the appliance and dressings were replaced second daily, with the dressing component adjusted according to the depth and area of clinical dermatitis. The peristomal skin condition began to improve with the level of skin ulceration reducing to <10% and the pain score reducing to 4 (see Figures 2A, 2B & 2C). Over a month later, the faecal dermatitis had nearly resolved; there were no bleeding points and the peristomal skin was almost healed. The OST score was 2 and the digital pain score was 0 as there was no residual burning pain (see Figures 3A and 3B).

Supplementary ET nursing measures

Self-esteem and self participation in ostomy care

The existence of a stoma alters a patient’s original physical function, appearance and self-image, which may lead to a decrease in the patient’s self-esteem21. Self-esteem is an important evaluation index of an individual’s quality of life and mental health. Therefore, ET nurses must implement or facilitate collaborative, complementary nursing or medical measures that improve the quality of nursing and medical care provided. Pain relief was used according to the pain score to reduce pain and reduce the associated negative emotional effects of pain and improve care satisfaction.

Through explaining, demonstrating and encouraging the patient and her family to participate in self-management of the stoma we aimed to guide the patient to master the skills required to replace the ostomy appliance. Further, we sought to teach the patient to assess the stoma and peristomal skin in order to be able manage any peristomal skin complications and prevent further leakages. These measures would have the desired effect of alleviating any negative emotions regarding the stoma, build self-confidence and self-esteem, ensure ongoing healing of the peristomal skin, and prevent further instances of the development of faecal dermatitis.

Some general instructions on how to care for the stoma included advising the patient and her family to replace the ostomy bag when the patient had an empty stomach which would reduce the potential for the stoma to work when changing the pouch. The stoma and peristomal skin were to be cleaned with cold boiled water and a pH neutral soap. The correct methods for using ostomy skin care powder, anti-leakage cream, and Karaya transparent paste to improve ostomy appliance adhesion techniques were demonstrated to the patient and family. The patient was shown how to affix a convex base plate and pouch by tearing off the backing paper, sticking, pressing and smoothing the base plate the from bottom to upper edge of the base plate and from the inside to outside. Also, to ensure that the rim of the ostomy bag is firmly attached to the base plate, the bottom of the pouch was clipped shut and the belt correctly applied to ensure it was not too tight to cause any skin damage.

Durability and wear time of the ostomy appliance were also discussed. The patient was advised not to wear the appliance for longer than 1 week. Examination of the base plate for durability was reviewed. If any whitish part of the base plate was less than 1cm from the edge of the base plate, indicating softening of the base plate, or if there was any leakage, the base plate should be replaced immediately. The ostomy appliance was to be emptied when it was one third to one half full. The ostomy bag was to be rinsed, ensuring that the water did not wash over the bottom plate.

Strengthening inter-professional healthcare communication to improve patient outcomes

It is important for the ET nurse to communicate effectively with other members of the health professional team who may interact with the patient with a stoma to improve patient outcomes.

As the patient had undergone two major surgical procedures within 4 months and seven cycles of chemotherapy, the usual processes of digestion and absorption of nutrients after ileostomy surgery were severely affected. This, coupled with the patient’s low nutritional intake of protein, the lack of vitamins and trace elements, led to the patient being malnourished, which detrimentally affected the healing process.

Communication between the ET nurse and doctors occurred regarding the patient’s ileostomy complications of liquid ileostomy discharge and leaking ostomy appliance leading to faecal dermatitis and corroded peristomal skin. Ostomy and skin care regimens were discussed to prevent leakages and promote skin healing. As the chemotherapy the patient was receiving was thought to be affecting the ileostomy discharge, the patient’s chemotherapy treatment was suspended.

Through the nutrition department, the patient was instructed to increase the number of daily meals and the amount of food eaten each day. The patient was encouraged to: eat more protein-rich foods; eat less easily digestible foods such as mushrooms, corn, leek and other similar vegetables or high fibre foods; chew the food thoroughly to improve digestion and absorption; and to increase their daily intake of fluids to 2000–2500mls including water, juice and soup to improve the patient’s nutritional status. These measures were aimed at improving the patient’s nutritional status to provide the necessary conditions for tissue repair and healing of the skin around the stoma.

Health education

The advice provided by the nutrition department regarding dietary requirements was reinforced with the patient to ensure the patient achieved and maintained a stable weight. If the patient’s stoma discharge became thin and watery and adherence of the ostomy appliance became impaired, the patient was advised to seek medical advice for prescription of oral medication that would inhibit peristalsis to make the faecal discharge more paste-like to reduce leakage.

Evaluation of the supplementary nursing measures

After two episodes of faecal dermatitis around the stoma, the extent of skin damage, amount of bleeding, volume of wound exudate, pain and OST scores were significantly reduced as a result of the supplementary nursing measures introduced coupled with changes to skin care and the ostomy appliance as outlined above.

On 18 April 2018, the peristomal skin dermatitis was successfully healed (see Figures 3A and 3B). The patient was in stable mood, and she continued to receive supportive ET nursing visits for a further six times. The case shows that ET nurses can effectively intervene in the treatment of complications around the ostomy.

Discussion

Postoperatively, management of a stoma can be challenging. In this case study, after assessing the patient’s stoma and peristomal skin, the conclusion drawn was that the patient had faecal dermatitis secondary to prolonged contact of ileostomy faecal fluid with the skin. There are numerous reasons why this may occur. The main causes of faecal dermatitis around the stoma are manifested in three aspects: the stoma site is not suitable (usually as no pre-operative stoma siting was undertaken); the ostomy appliance is not suitable (it is incorrectly sized or worn improperly); and the stoma is poorly constructed (flattened or retracted). Other reasons for poor ostomy pouch adhesion, subsequent leakage and impaired skin integrity from exposure to faecal fluid are abdominal distension, poor muscle tone, obesity or a BMI greater than 25 or undulating abdominal contours from subcutaneous fat, recurrent disease and inappropriate skin care22.

The OST score of 10 points was arrived at because of the improperly sited position of the stoma; the stoma was positioned in a large skin fold of the abdominal wall. The abdominal wall was not flat after applying the non-convex base plate when the patient was either seated, standing or moving. The base plate frequently leaked, causing skin erosion from faecal fluid, and the patient’s physical and mental state was affected, creating obstacles to self-care. The lack of prompt attention in managing the leakage of faecal fluid by using an ostomy appliance with a convex base plate resulted in serious stoma dermatitis.

Stoma siting can be performed by an ET nurse or an experienced trained nurse alone or in conjunction with surgical opinion. The guiding principles of stoma siting are that: the patient can clearly see the stoma site in different postures (semi-recumbent position, sitting position and standing positions); the skin around the stoma is flat and healthy (no depressions, scars, wrinkles, belt lines and away from bony prominences); and, the stoma is sited within the rectus abdominis muscle. Optimal placement of the stoma should prevent postoperative complications and should not affect the daily life of patients.

However, postoperatively, the condition of the inner abdominal wall and skin of the abdomen around the stoma will change due to various reasons such as further surgical procedures, healing processes, age, weight loss or recurrent disease23. Therefore, ET nurses need to regularly assess patients’ abdomens and choose stoma supplies that better fit the patients’ abdomen and stoma24.

When assessing the contours of the abdominal wall and skin around the stoma, the degree of softness or stiffness of the abdominal wall should be observed. A soft abdominal wall may not be able to support the stoma well because of its insufficient muscle strength. In situations such as this, the stoma would therefore benefit from being supported with a harder convex base plate25.

Ostomy products with convexity are frequently cited as ideal products to manage flat, retracted or sideways slanting stomas and to compensate for irregular peristomal planes such as creases or folds. Convexity was defined26 as “A curvature on the skin side of the barrier or accessory”. Convexity assists with product adhesion to the peristomal skin, facilitating longer wear time of ostomy appliances. There are various characteristics associated with convex appliances and accessories that indicate their profile in terms of depth (shallow, medium and deep), softness and hardness27.

The general consensus of opinion regarding the use of convexity is that convexity is beneficial to prevent leakage where there are abdominal or stomal deformities. There is some debate and concern, however, over the use of convexity immediately after surgery due to the potential for mucocutaneous separation. The use of soft convexity postoperatively from an outpatient perspective is acknowledged as a reasonable strategy that significantly reduces appliance leakage, prolongs appliance wear time, and reduces faecal dermatitis, thereby improving patient satisfaction and quality of life28. One study showed that, for ileostomy patients, the early postoperative use of convexity reduce postoperative complications by 85% when compared to the use of an appliance without convexity.

In this case, and to aid the management of peristomal skin complications, a convex base plate was used to support the abdominal wall and flatten skin folds. Other measures that were effectively used in conjunction with convexity to prevent further leakages, aid skin healing and extend the wear time of the base plate were a stoma skin-protecting powder, a skin protective film, stoma paste and a hydrocolloid dressing.

Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, pectin or Karaya are the main components of stoma skin care powders that are used to manage excoriated weeping skin around stomas. They form a moist thin film on the surface of the damaged skin by absorbing wound exudate to form a crust to which the base plate can stick firmly29,30. Skin protectant sealants can be used to apply a thin film over the stoma powders to provide a dry surface to aid adherence of skin barriers. The main components of the skin protective sealant are vinyl acetate copolymers, propanediol and ethanol. Stoma pastes may also be Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, pectin or Karaya based. Pastes are easy to form protective layers around the stoma to keep the skin around the stoma smooth and flat and provide a further barrier to faecal material eroding the skin and appliance.

Hydrocolloid dressings are widely used to create a moist wound healing environment. Properties of hydrocolloids include regulation of the oxygen tension at the wound surface, promotion of angiogenesis and formation of capillaries, autolytic debridement of necrotic tissue and fibrin, and stimulation of the release of various growth factors, all of which play a very important role in the healing process. In addition, they can maintain the temperature of wound surface, absorb moisture, avoid mechanical injury of new granulation tissue, and protect nerve endings to reduce wound pain. Thin versions of hydrocolloids are flexible and conformable to tissue planes, have good adhesion, are easy to apply, are waterproof, are comfortable for patients, and can be used to prevent peristomal skin stripping in conjunction with an ostomy appliance. Light colour changes in the hydrocolloid indicate when the dressing should be replaced.

The use of a two-piece ostomy appliance with convexity in the transparent base plate plus adjunct stoma powders, stoma pastes, hydrocolloid dressings and a belt to firmly anchor the appliance made a substantial difference to the wear time of the appliance and skin healing process. Overall, this management strategy alleviated the patient’s anxiety and improved her sense of well-being.

In addition to providing essential stomal therapy nursing services for patients, ET nurses also provide cultural, psychological, educational and rehabilitative services to patients and their families to meet their health needs. ET nurses collaborate with other health professionals and use the latest relevant professional knowledge to provide evidence-based ET practices. Using these care strategies, ET nurses can assist patients with stomas to actively face underlying disease processes, cooperate with prescribed treatment, and actively participate in rehabilitative processes in order to be able to resume a normal life as soon as possible31.

There is an ongoing need to identify, recognise and strengthen the professional value of ET nurses and the role they play in assisting people requiring ostomy surgery in China. It is an urgent problem to be resolved within human resources management in all hospitals providing ostomy surgery. Wang Xi and others believe that therapists play an important role in clinical work32.

Summary

This case study has described the challenges faced in managing a severe case of peristomal irritant contact dermatitis or MASD. The key point of the ET nursing intervention and stoma care was to actively treat the denuded skin and wounds around the stoma using a convex base plate and stoma accessories such as stoma powder, skin sealants, stoma paste, thin hydrocolloid dressing and a belt to aid adhesion of the appliance to prevent leakage of the appliance. In the presence of irritant contact dermatitis or MASD, these types of measures should be introduced as early as possible once the cause of the leakage is determined. This reduces patient discomfort, improves the patient’s quality of life, and improves wound healing outcomes.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

凸面造口装置在恢复造口周围皮肤完整性中的应用:一项病例研究

Fengzhi Yan and Mengxiao Jiang

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.1.10-17

摘要

本病例研究描述了对1例术后1个月到门诊部就诊的回肠造口术患者造口周围皮肤排泄液造成的刺激性接触性皮炎的护理管理。该术后并发症的发生原因是造口位于腹部皱褶内,引起造口装置渗漏和皮肤溃疡形成,进而妨碍造口装置底盘在造口周围皮肤上的牢固粘附。另外,患者因该并发症非常焦虑。在本患者病例中,初步目标是评估和解决造口周围皮肤并发症,提供能够采用固定带尽早固定造口装置的凸面造口装置,并最终着手加强对患者及其家属的心理辅导和饮食指导。结果发现,上述护理干预可降低造口周围粪水性皮炎并发症的发生率,改善患者生活质量,值得应用。

引言

回肠造口是一种小肠造口,某些情况下是特定结直肠疾病(如直肠癌)和其他病情(如炎性肠病、憩室病、放射性肠炎、腹部外伤、肠梗阻等)必不可少的手术操作1–3。回肠造口通常位于腹部右下区或右下侧。

造口术后频发造口周围皮肤并发症,报告的患病率为10–70% 4,5。造口术后一年内,报告的各类造口周围皮肤损伤的发生率为15–43%6,7。据称,造口周围皮肤病占肠造口治疗护士(ET护士)就诊率的40%以上。粪水性皮炎是其中一种最常见的回肠造口术后早期并发症,一项对220例新造口患者的研究发现,粪水性皮炎发生率高达69% 8。

粪水性皮炎的定义、病因和管理策略

粪水性皮炎是频繁接触含消化酶的排泄液,腐蚀造口周围皮肤而引起的9。近来,造口周围潮湿相关性皮炎(MASD)一词也定义为与接触排出物(如尿液或粪便)相关的造口周围皮肤炎症或剥脱10,11。刺激性接触性皮炎的初始表现可能为皮肤红肿,如果持续接触排出物,则可能起疱或剥脱。皮肤缺损模式反映了发生排泄物渗漏的区域12,13。

排泄物含蛋白水解酶和脂肪分解酶,可损伤皮肤上皮(和水分)屏障中的蛋白和脂质成分。回肠造口排出物通常比结肠造口排出物更偏向液体,并且富含消化酶。回肠造口排泄物的黏稠度取决于回肠内的造口部位。在粘稠度上,回肠造口的输出物可能是液体或黏稠物(糊状)。造口部位更靠近胃部则排泄物多为液体,因此消化酶含量也更高。

组织在愈合过程中不断受到摩擦力、剪切力和腐蚀性物质的损害,造成粘膜损伤,炎性改变,组织细胞增殖,并形成肉芽肿。造口粘膜肉芽肿是常见于粘膜皮肤结合处或造口粘膜本身的凸起良性病变。造口边缘周围可能出现一个或多个肉芽肿。造口粘膜肉芽肿不仅造成疼痛搔痒,而且非常脆弱,容易出血,影响造口袋的粘附,从而造成渗漏,引起造口周围皮炎。

另外,粪水性皮炎通常疼痛难忍,加上造口袋的持续渗漏会极大影响患者生活质量和早期康复,从而可能给患者带来严重的长期生理和心理影响14。

造口护理中凸面的应用

美国的一项伤口、造口和失禁护理护士横断面描述性定量调查中,281名受访者对造口和周围皮肤并发症管理进行了排名。在造口周围刺激性接触性皮炎(定义为“皮肤接触粪便、尿液排泄物或化学制剂而产生的损伤”15)的管理策略中,描述了凸面造口装置、防漏膏、防漏环、造口粉和固定带的使用。还讨论了确定接触性皮炎病因的重要性。

目前国际专家支持的循证护理实践提倡采用通过凸面造口装置和附件实现的凸面来管理特定的造口周围并发症。他们建议用凸面造口装置或保护剂填充腹部轮廓和皮肤皱褶形成的凹陷,以便使造口突出,使腹部皱褶或皮肤皱纹平整,从而增强造口装置的粘附,减少渗漏16,17。

造口皮肤工具(OST)可帮助ET护士从变色(D)、糜烂(E)和组织(T)等方面客观量化造口周围皮肤损伤,并将这些改变叙述给其他专业医护人员,以确保对造口周围皮肤损伤的理解和管理的一致性。每项DET参数按皮肤损伤受累的面积大小(0-3分)和严重程度(0-2分)进行评分,因此每一项的分值为0-5分。总体分值范围为0-15分,0代表正常皮肤,15代表严重程度和范围的最大组合18。

还采用0-10这11个数字组成的数值评分量表(NRS)评价疼痛程度;0代表无痛,10分代表最痛。根据受试者个人疼痛体验为其标记其中一个数值19。

本文描述了为1例造口周围皮肤粪水性皮炎提供的临床护理情况,并讨论了使用凸面技术来最大程度减小造口附近皮肤褶皱的不良影响的原理。

病例研究

患者概述

女性患者1例,42岁,因直肠癌行择期根治术,并于2017年11月30日行回肠造口术。该患者的造口部位并不是术前决定的。术后对该患者提供造口和伤口管理指导。虽然该患者有权独立选择造口装置,但实际由医院造口助手帮她选择了造口产品。选择了两件式平面底盘,患者计划于3个月后开始接受靶向化疗。靶向化疗药物理论上是精准导向药物,对肿瘤细胞进行精准打击,而对治愈的正常细胞损伤极小。

患者、造口和造口周围皮肤评估

术后1个月,即12月26日在门诊部进行首次访视时,患者佩戴包含平面底盘的两件式造口产品。患者报告称一直在发生严重渗漏。评估时,造口周围发生渗漏的原因显而易见。

回肠造口位于较大的腹部皱褶内。造口仅比造口周围皮肤的高度突出0.6 cm。主要问题是腹部上的皱褶,这造成底盘粘附松动,从而引起造口装置渗漏。造口左右双侧周围皮肤严重溃疡,有肉芽组织过度形成迹象。造口周围明显可见多个出血点(超过区域的50%)(见图1A)。患者主诉造口周围皮肤灼痛。造口渗出微弱的绿色排泄液,并沉积到造口周围皮肤。使用OST评估的皮肤完整性得分为10,数字疼痛评分为8分(见表1和2)。患者腹部触诊柔软。

图1A

表1. OST评分和护理措施

表2. OST DET评分

患者非常焦虑,经常躁动不安,造口周围尤其疼痛。排泄液渗漏造成恶臭。患者嗜睡,食欲不振,主诉体重下降6 kg。体重指数(BMI)为27.4。血红蛋白水平偏低,眼睑苍白。

由于患者出院时佩戴平面底盘,使用生理盐水清洗造口及皮肤,并使用造口护肤粉、皮肤保护剂、防漏膏和固定带后更换相同的造口装置(见图1B)。但是,患者返家后约3小时发生了造口装置渗漏(见图1C和1D)。因此要求患者更换造口装置,改用门诊访视期间向她提供的凸面底盘替代产品。

图1B

干预和造口管理方案

造口护理和护理程序

根据所进行的评估,主要存在以下护理问题:造口周围并发症、粪水性皮炎、疼痛和焦虑。确定的护理目标如下:

- 采用适当的造口护理产品防止造口周围渗漏。

- 采用适当的皮肤护理和敷料产品,促进造口周围皮肤愈合,减少肉芽组织过度形成(增生)。

- 减轻患者造口周围皮肤疼痛。

- 缓解患者焦虑。

- 防止出现临床营养不良。

- 将回肠造口输出减少至正常水平和黏稠度。

敷料方案和造口装置的选择

富含消化酶的水性排泄物造成造口周围皮肤糜烂,形成溃疡。为了防止潜在的继发性感染以及控制出血和促进上皮组织生长,采取以下皮肤护理和敷料方案:

- 用生理盐水彻底冲洗造口和造口周围皮肤。

- 用浸泡于生理盐水中的纱布反复、轻柔擦洗残留的松散坏死组织和残留排泄物。

- 用无菌纱布擦干该区域。用生理盐水药签轻轻按压出血点,注意止血时不要损伤造口及造口周围皮肤的正常组织。

- 在造口周围皮肤洒上造口粉。5–10分钟后去除多余造口粉。

- 然后在造口周围皮肤上喷洒皮肤保护膜(覆盖薄膜片)。约10分钟后皮肤上形成一层光亮的膜。

- 使用造口护肤粉重复以上步骤3到5次。

- 用藻酸盐敷料和超薄水胶体覆盖糜烂和溃疡的皮肤区域。

- 在装上凸面底盘和固定带之前,先在造口周围涂上防漏膏后,以防止渗漏。

观察造口,更换造口装置和伤口敷料

患者的回肠造口输出中水分含量非常高,因此建议患者卧床休息。为防止卧床时对造口装置施加任何压力以及为了防止渗漏,指导患者造口袋的开口应朝向身体右侧,并应定期清空造口袋中的排泄物。还要求患者每天观察造口颜色,观察造口周围是否存在出血和渗漏,如有任何渗漏,则更换敷料和造口袋。造口装置和敷料一般应每天更换2次,并根据临床皮炎的深度和面积调整敷料成分。造口周围皮肤情况开始好转,皮肤溃疡面积减少到<10%,疼痛评分减少到4分(见图2A、2B和2C)。一个多月后,粪水性皮炎几乎完全治愈;无出血点,造口周围皮肤基本愈合。OST评分为2分,数字疼痛评分为0分,因为没有残留灼痛感(见图3A和3B)。

补充ET护理措施

造口护理中的自尊心和自我参与

造口的存在改变了患者的原始身体机能、外表和自我形象,可能导致患者自尊心下降21。自尊心是个体生活质量和心理健康的重要评价指标。因此,ET护士必须实施或促进协作、补充性护理和医疗措施,以提高所提供的医疗护理质量。根据疼痛评分采用止痛措施来缓解疼痛并减少疼痛相关的负面情绪影响,提高护理满意度。

通过解释和演示,鼓励患者及其家属参与造口的自我管理。我们的目的是引导患者掌握更换造口装置的必要技能。另外,我们力求指导患者评估造口和造口周围皮肤,以便能够管理造口周围皮肤并发症,防止进一步渗漏。上述措施有望缓解造口引起的负面情绪,建立自信和自尊,确保造口周围皮肤持续愈合,防止再次发生粪水性皮炎。

关于如何护理造口的一些一般说明包括:建议患者及其家属在患者空腹时更换造口袋,以减少更换造口袋时造口排泄的可能性。使用凉开水和中性肥皂清洗造口和造口周围皮肤。向患者及其家属演示了使用造口护肤粉、防漏膏、Karaya透明膏来加强造口装置粘附的相关技术的正确操作方法。向患者展示了如何固定凸面底盘和造口袋:撕开衬纸后,从底盘下缘到上缘,从内到外,将底盘粘贴、按压、抚平。此外,为了确保造口袋的连接环牢固固定在底盘上,夹闭造口袋的底部,并正确系好固定带,确保不要太紧,以免皮肤损伤。

还讨论了造口装置的耐用性和佩戴时间。建议患者造口装置的佩戴时间不要超过1周。检查底盘的耐用性。如果底盘发白的部分离底盘边缘不足1 cm,说明底盘变软,或出现渗漏,应立即更换底盘。造口装置填充量达到三分之一到一半时,即清空造口装置。冲洗造口袋时确保水不会冲过底盘。

加强专业医护人员间的沟通,改善患者结局

为了改善患者结局,ET护士与专业医护团队中其他可能与造口患者互动的成员进行有效沟通是非常重要的。

由于患者在4个月内接受了2次大型外科手术而且接受了7个周期的化疗,严重影响了回肠造口术后的正常消化和营养物吸收过程。再加上患者蛋白质营养摄取不足,缺乏维生素和微量元素,导致患者营养不良,妨碍愈合过程。

ET护士和医生就患者回肠造口术并发症,即回肠造口液体排泄及造口装置渗漏导致的造口周围皮肤粪水性皮炎和糜烂进行了沟通。讨论了防止渗漏和促进皮肤愈合的造口与皮肤护理方案。由于认为患者正在接受的化疗会影响回肠造口排泄,所以暂停化疗。

另外,由营养科指导患者增加每日进餐次数和饮食量。鼓励患者:多吃富含蛋白质的食物;少吃易消化的食物,如蘑菇、玉米、韭菜及其他类似蔬菜或高纤维食物;完全嚼碎食物以促进消化吸收;每日液体摄入量增加到2000–2500 ml,包括水、果汁和汤,以改善患者营养状态。以上措施旨在改善患者营养状态,提供造口周围组织修复和皮肤愈合的必要条件。

健康教育

向患者强调营养科提供的关于饮食要求的建议,确保患者达到并维持稳定体重。如果患者的造口排泄稀薄且水分含量高,妨碍造口装置的粘附,则建议患者及时就医,开处抑制肠蠕动的口服药物,促使形成糊状排泄物,以减少渗漏。

补充护理措施评价

在造口周围发生2次粪水性皮炎后,由于实施了补充护理措施并如上所述改变了皮肤护理和更换了造口装置,皮肤损伤的范围、出血量、伤口渗出量、疼痛和OST评分均显著降低。

2018年4月18日,造口周围皮肤皮炎成功治愈(见图3A和3B)。患者情绪稳定,并在后续6次继续接受支持性ET护理访视。该病例表明,ET护士可有效干预造口周围并发症的治疗。

讨论

造口术后,造口的管理可能非常有挑战性。本病例研究中,评估患者造口及造口周围皮肤后,结论是患者患有皮肤长期接触回肠造口排泄液而继发的粪水性皮炎。可能的发病原因有多个。造口周围粪水性皮炎的主要病因表现为三个方面:造口部位不当(通常是因为未在术前选择造口部位);造口装置不当(尺寸不合适或佩戴方式不当);造口结构不良(扁平或收缩)。导致造口袋粘附不良,随后发生渗漏并因皮肤接触排泄液而损害皮肤完整性的其他原因还有腹胀、肌肉松弛、肥胖或BMI大于25、或皮下脂肪造成腹部轮廓起伏、复发性疾病和皮肤护理不当22。

由于造口部位位置不当,OST评分为10分;造口位于腹壁的较大皮肤皱褶内。安放非凸面底盘后,患者无论是坐位、站立位或移动,腹壁均不平坦。底盘经常渗漏,排泄液导致皮肤腐烂,患者的生理和心理状态受到影响,妨碍自我护理。采用凸面底盘造口装置时未及时注意排泄液渗漏的管理,造成严重的造口皮炎。

造口部位的选择可由ET护士或有经验且受过培训的护士单独进行,或结合外科意见。选择造口部位的指导原则为:患者可以在不同体位下(半卧位、坐位和站立位)清楚看到造口部位;造口周围皮肤平坦健康(无凹陷、疤痕、褶皱、腰线,并远离骨性隆起位置);而且,造口应位于腹直肌内。理想的造口位置应当可防止术后并发症,且不应影响患者日常生活。

但是,由于进一步接受外科手术、愈合过程、年龄、体重减轻、复发性疾病等多种原因,在术后,腹部内壁和造口周围的腹部皮肤状况会发生变化23。因此,ET护士需要定期评估患者腹部,选择最适合患者腹部和造口的造口用品24。

评估腹壁轮廓和造口周围皮肤时,应观察腹壁柔软度或僵硬度。柔软的腹壁肌肉强度不足,可能无法稳定支撑造口。在这类情况下,硬度更大的凸面底盘将更好地支撑造口25。

凸面造口产品频频被称为管理扁平、收缩或侧倾造口的理想产品,能够弥补造口周围平面的不规则(如皱褶)。凸面定义为26“底盘或附件的皮肤侧的曲面”。凸面有助于产品粘附在造口周围皮肤上,帮助延长造口装置的佩戴时间。凸面造口装置和附件有各种特征,表明其在深度(表浅、中等、深度)、柔软度与硬度方面的概况27。

关于使用凸面的一般意见共识是,凸面有助于防止腹部或造口畸形区域的渗漏。但是,对于术后立即使用凸面装置存在某些争议和疑虑,因为其可能引起粘膜与皮肤分离。从门诊的角度考虑,术后使用柔软凸面装置是一种合理的策略,可显著减少造口装置渗漏,延长造口装置佩戴时间,减少粪水性皮炎,从而提高患者满意度和生活质量28。一项研究显示,对于回肠造口患者,相比使用非凸面装置,术后早期使用凸面装置可将术后并发症减少85%。

本病例中,为帮助管理造口周围皮肤并发症,采用凸面底盘来支撑腹壁和抚平皮肤皱襞。同时,还联合采用其他有效措施,如造口护肤粉、皮肤保护膜、造口膏和水胶体敷料,防止进一步渗漏,促进皮肤愈合,延长底盘佩戴时间。

造口护肤粉的主要成分是羧甲基纤维素钠、果胶或刺梧桐胶,用来管理造口周围皮肤的表皮脱落和渗液。其可吸收伤口渗出液形成痂样结构,在受损皮肤表面形成薄层吸湿膜,供底盘牢固附着29,30。还可使用皮肤保护防漏剂,在造口粉上形成薄膜,提供干燥表面,帮助底盘粘附。皮肤保护防漏剂的主要成分是醋酸乙烯酯共聚物、丙二醇和乙醇。造口膏的主要成分也可能是羧甲基纤维素钠、果胶或刺梧桐胶。造口膏容易在造口周围形成保护层,保持造口周围皮肤平滑,进一步形成防止排泄物腐蚀皮肤和造口装置的屏障。

水胶体敷料广泛用于创造湿润的伤口愈合环境。水胶体的特性包含调节伤口表面的氧张力,促进血管新生和毛细血管形成,自溶清理坏死组织和纤维蛋白,刺激各种生长因子的释放,这些都在愈合过程中发挥非常重要的作用。另外,其还能够维持伤口表面温度,吸收水分,避免新生肉芽组织的机械损伤,保护神经末梢以缓解伤口疼痛。薄型水胶体非常柔软,能贴合组织面,粘附性强,易于敷贴,防水,患者舒适度高,可用于防止造口周围皮肤随造口装置剥脱。水胶体颜色变浅说明需要更换敷料。

使用两件式透明凸面底盘造口装置,再辅以造口粉、造口膏、水胶体敷料和固定带牢固固定造口装置,可大幅延长造口装置佩戴时间,加快皮肤愈合过程。总之,该管理策略缓解了患者的焦虑,提高了患者的幸福感。

除了为患者提供基础造口治疗护理服务外,ET护士还为患者及其家属提供文化、心理、教育和康复服务,以满足其健康需求。ET护士与其他专业医护人员协作,使用最新的相关专业知识提供循证ET护理实践。通过上述护理策略,ET护士可帮助造口患者主动面对基础疾病过程,使其配合处方治疗,积极参与康复过程,以便能够尽快恢复正常生活31。

因此,我们需要不断发现、认可和加强ET护士的职业价值及其在帮助中国需要造口术的患者中发挥的作用。这是所有提供造口术的医院人力资源管理中迫切需要解决的问题。Wang Xi等人认为治疗师在临床工作中发挥重要的作用32。

总结

本病例研究描述了在管理一例造口周围皮肤刺激性接触性皮炎或MASD重症病例中面对的难题。ET护理干预和造口护理的关键点是采用凸面底盘和造口附件(如造口粉、皮肤保护剂、造口膏、薄层水胶体敷料和帮助固定造口装置的固定带)来防止造口装置渗漏,从而积极治疗造口周围剥脱的皮肤和伤口。发生刺激性接触性皮炎或MASD后,一旦确定渗漏原因,即应尽早采取上述措施。这可以减少患者不适,提高患者生活质量和改善伤口愈合结局。

利益冲突

作者声明无利益冲突。

资助

作者未因本研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Fengzhi Yan*

Shenzhen Hospital of Southern Medical University, 518000, China

Email yfz655034@163.com

Mengxiao Jiang

Tumor Hospital of Zhongshan Medical University, Urology Dept, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center; State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China; Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine, Guangzhou 510060, China

* Corresponding author

References

- ai-Ling H, Chun ZM & Juan LW. Clinical nursing and practice of modern wound and enterostomy. Beijing: China Union Medical University Press, 2010:371-376.

- Shengben Z, Dong TW. Clinical application of enterostomy. J Chinese Gastroenterol 2003;3:146.

- Beitz J. Other conditions that lead to a fecal diversion. In: Carmel JE, Colwell JC, Goldberg MT (Eds). Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Core Curriculum: Ostomy Management. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; pp 65–76.

- Ratliff CR, Scarano KA, Donovan AM, et al. A study of peristomal complications. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2005;32(1):33–37.

- Gray M, Colwell JC, Doughty D, Goldberg Met al. Peristomal moisture-associated skin damage in adults with fecal ostomies: a comprehensive review and consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;00(00):1–11.

- Berndtsson I E, Lindholm E, Oresland T, et al. Health-related quality of life and pouch function in continent ileostomy patients: a 30-year perspective. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47(12):2131–2137.

- Nybaek H, Jemec GBE. Skin problems in stoma patients. J Euro Academy Dermatol & Venereol (JEADV) 2010;24:249–257.

- Meisner S, Lehur P-A, Moran B, Martins L, Jemec GBE. Peristomal skin complications are common, expensive, and difficult to manage: a population based cost modeling study. PLoS ONE 2012;7(5): e37813. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037813

- Woo KY, Sibbald RG, Ayello EA, Coutts PM, et al. Peristomal skin complications and management. Adv Skin Wound Care 2009;22 (11):522–32.

- Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM, et al. Moisture-associated skin damage: overview and pathophysiology. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38(3):233–241.

- Colwell JC, Ratliff CR, Goldberg M, Baharestani MM, et al. MASD Part 3: peristomal moisture-associated dermatitis and periwound moisture-associated dermatitis: a consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38(5):541-553.

- Salvadena G. Peristomal skin conditions. In: Carmel JE, Colwell JC, Goldberg MT (Eds). Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Core Curriculum: Ostomy Management. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer, pp 176–190.

- Stelton S, Zulkowski K, Ayello EA. Practice implications for peristomal skin assessment and care from 2014 World Council of Enterostomal Therapists International Ostomy Guideline. Adv Skin & Wound Care 2015;28(6):275–284.

- Carlsson E, Fingren J, Hallén AM, et al. The prevalence of ostomy-related complications 1 year after ostomy surgery: a prospective, descriptive, clinical study. Ostomy Wound Management 2016;62(10):34–48.

- Beitz JM, Colwell JC. Stomal and peristomal complications prioritizing management approaches in adults. Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(5):445–454.

- Colwell JC, McNichol L, Boarini J. Enterostomal therapy nurses current ostomy care practice related to peristomal skin issues. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(3):257–261.

- Hoeflok J, Salvadalena G, Pridham S, Droste W, et al. Use of convexity in ostomy care results of an international consensus meeting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):55–62.

- Martins L, Ayello EA, Claessens I, et al.The Ostomy Skin Tool: tracking peristomal skin changes. Br J Nurs 2010;19(15):960–964.

- Walker H, Hopkins G, Waller M, et al. Raising the bar: new flexible convex ostomy appliance – a randomised controlled trial. WCET J Supp 2016;36(1):S1–S7.

- Yan Guangbin. Numerical rating scale of NRS pain [J]. Chinese J Joint Surg (electronic edition) 2014;(3):410–410.

- Van Den Bulck R. Peristomal skin disorders: identification of risk factors; retrospective study (pending study). J Wound Technology 2012;18:6–7.

- University of Toronto. Miller D, Fresca M, Johnston D, McKenzie M, et al. Perioperative care of patients with an ostomy: a Clinical Practice Guideline. University of Toronto’s Best Practice in Surgery 2016.

- Rolstad BS, Erwin-Toth PL. Peristomal skin complications: prevention and management. Ostomy/Wound Management 2004;50(9):68–77.

- Guo Rui. Perioperative clinical nursing of ileostomy [a]. Henan Nursing Association. Proceedings of Henan tumor nursing training class in 2013 [C]. Henan Nursing Society; 2013:2

- Colwell J. Selection of a pouching system. In: Carmel JE, Colwell JC, Goldberg MT, (Eds). Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Core Curriculum: Ostomy Management. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2016: pp.120–130.

- Hoeflok J, Kittscha J, Purnell P. Use of convexity in pouching: a comprehensive review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(5):506–512.

- Young MJ. Convexity in the management of problem stomas. Ostomy/Wound Manage 1992;38(4):53–60.

- Perrin A. Convex stoma appliances: an audit of stoma care nurses. Br J Nurs 2016;25(22):S10–S15.

- Lieder J, et al. Are you perplexed? Go to convex! J WOCN 2017;Supp 3s:44:S37–S37.

- Salvadena G. Appendix E: colostomy and ileostomy products and tips. Best Practice for Clinicians. In: Carmel JE, Colwell JC & Goldberg MT (Eds). Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Core Curriculum: Ostomy Management. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2016: pp 241–249.

- Huddleston Cross H. Management of high output stomas. J Wound Technology 2012;18:20–23.

- Ling W, Rui M, Xiaowei Z, et al. Thoughts on the cultivation and use of oral therapists in China. J Nursing Manage 2013;13(11):770–772.