Volume 40 Number 4

Skin care for the protection and treatment of incontinence associated dermatitis (IAD) to minimise susceptibility for pressure injury (PI) development

Hiske Smart and R Gary Sibbald

Keywords pressure injuries, incontinence associated dermatitis, IAD, IAD skin protection

For referencing Smart H & Sibbald RG. Skin care for the protection and treatment of incontinence associated dermatitis (IAD) to minimise susceptibility for pressure injury (PI) development. WCET® Journal 2020;40(4):40-44

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.4.40-44

Abstract

This manuscript summarises the important clinical concept of having a skin care protocol to protect and treat skin against incontinence associated dermatitis (IAD) to prevent and minimise the association IAD has on the subsequent development of pressure injuries (PI).

Skin protection for all skin tones is imperative to protect skin against exaggerated late presentations of IAD.

Introduction

Preserving the barrier function of the skin is an important clinical practice role that is often found in the nursing practice domain. Incontinence associated dermatitis (IAD) frequently includes severe discomfort to patients and tends to develop quickly in white skinned individuals and later, but in exaggerated form, in persons with darker tones of skin; this is due to the first clinical visual cues being obscured and not identified. Using evidence from the literature with clinical examples, the authors will highlight zinc oxide paste as a care option in the clinical setting due to ease of availability and relative low cost.

Incontinence Associated Dermatitis (IAD)

IAD is one of the four aetiologies included in the moisture associated dermatitis (MASD) category. IAD has been defined in the literature as a “form of irritant contact dermatitis that develops from chronic exposure to urine or liquid stool”1–3. The aetiology is believed to be from prolonged exposure of skin to urine or liquid stool (often in combination), with a resulting change of the normal acid pH of the skin into an alkaline pH level.1–6 Once the ‘acid mantle’ of the skin is compromised, the skin can undergo an inflammatory response (erythema) to the moisture from urine and/or faeces and the skin barrier may become compromised1–6.

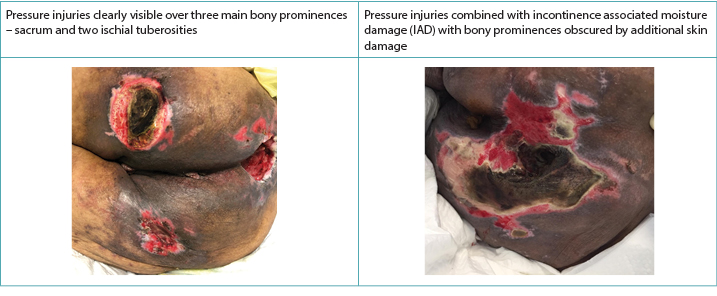

Red skin (erythema) looks different depending on the natural pigmentation of the skin5. In brown or black skin, the erythema may not appear red but can have a darker tone to the surrounding skin and create diagnostic difficulty in examining the skin (Figure 1). Skin damage prevention is always better than treatment, but early skin damage is often harder to detect in darker skin tones5, leading to late initiation of interventions.

Figure 1. Clinical presentation of erythema and IAD co-existing with PI as seen in darker skin tones (Table and photos © Smart & Sibbald)

Pressure Injuries (PI) and IAD in combination

The literature supports an association between IAD and pressure injury (PI) formation, although the aetiology differs between the two7–11. Lachenbruch et al.8 analysed 176,689 patients and found that 92,889 persons with incontinence had a 16.3% incidence of PIs as opposed to continent persons (n=83,800) with an incidence of 4.1%. IAD was associated with a higher incidence of PIs than predicted by the Braden Risk Scale Score alone. Gray and Giuliano9 evaluated 5,342 patients, of whom 2,492 (46.6%) were incontinent of urine. They concluded that 21.3% of IAD may be associated with secondary yeast infection, immobility and an increased incidence of sacral PIs9.

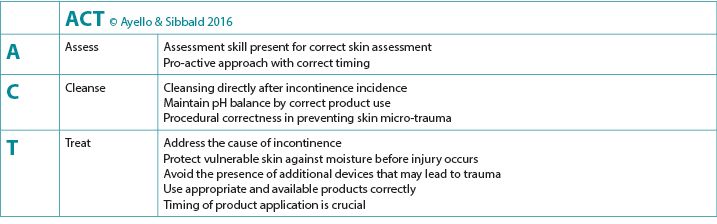

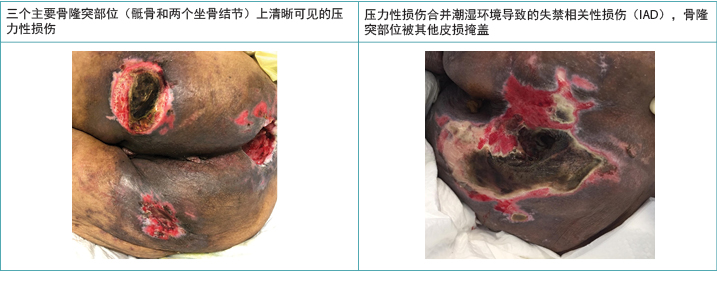

Clinically, PIs present themselves over distinct bony prominences with distinct borders10. IAD, on the other hand, has a more diffuse appearance that may be present in the perineal area and spread out over the buttock area, causing a distinct dermatitis on the skin in prolonged contact with the incontinence content2,3,5,10. When they co-exist, the IAD diffuse pattern remains in exaggerated form8,9 (Figure 2). McNichol and colleagues4 summarised the literature on the importance of treating IAD aggressively in an attempt to decrease the subsequent development of PIs.

Figure 2. PIs alone and when co-existing with IAD in darker skinned persons (Table and photos © Smart & Sibbald)

Further support to this IAD/PI association is documented in the most recent European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance Pressure Injury Guideline10. Three guideline elements are crucial to practice with regards to IAD and PI co-existence. The one relates to the loss of the inert protective ability of the skin with the statement: “Moisture associated skin damage may compromise the epidermis barrier function and hence predispose tissue to pressure injury”10(p.21). The other relates to the ability of skin to tolerate additional forces if compromised by surface moisture: “Skin surface moisture combined with pressure and/or shear can increase the incidence of pressure injuries”10(p.86).

Yet another statement, that may sound contradictory in nature, also advises against ultra-dry dehydrated or flaky skin as a risk factor for skin breakdown when in contact with incontinence content:

Although research directly linking skin moisturizing to reduction in pressure injury incidence is lacking, one epidemiological study in hospitalized individuals with limited mobility (n=286) noted that dry skin was a significant and independent risk factor for pressure injuries in a multi-variate analysis 21 (Level 3 prognostic). Regular application of a moisturizer in a skin hygiene regimen is suggested for promoting skin hydration and preventing other adverse skin conditions, including dry skin and skin tears10(p.86).

Barrier Function and skin protective intervention strategies

The key is to keep skin well moisturised as that maintains the moisture protective gradient of skin4,8,12,13. In white skinned individuals this moisture unit protective gradient is three times lower than in darker skinned persons (2:6 ratio)12. This explains the risk of dry skin as a factor in moisture damage from stool enzymes and urine urea that occurs in white skinned persons far quicker than in persons with darker skin tones. The quality of the stratum corneum is also important as it is on its thinnest on the two opposite ends of the age continuum (babies13 and the frail aged14). Early intervention to treat the cause of the incontinence needs to be achieved in conjunction with a skin care protocol to protect, maintain and restore the skin’s barrier4–8,11.

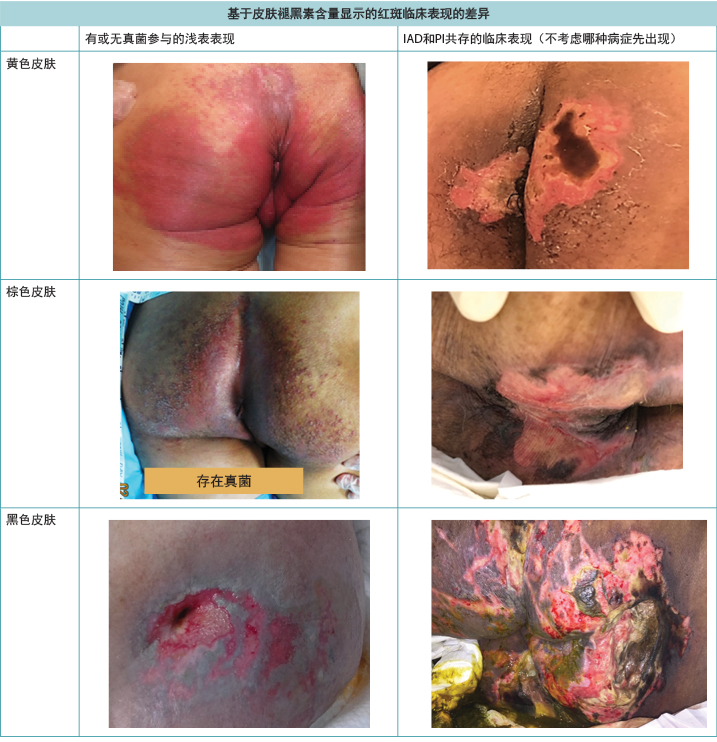

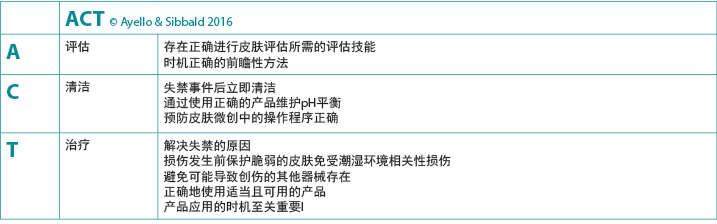

In clinical practice, raising awareness of staff nurses and non-healthcare professionals and including the person’s family involved in their care about the use of appropriate skin cleansing products is vital. Educational enablers are easy ways to summarise key points and provide caregiver learnings about essential components regarding care. One such educational enabler for IAD skin care is the use of the ACT mnemonic to guide the clinician into a comprehensive skin care approach4 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Clinical enabler to guide skin care in the presence of IAD

Skin care options

Skin cleansing after episodes of incontinence has evidence at B2 level as an effective intervention to remove residual surface debris from stool or urine on skin10. Neutral soaps or superfatted products15 are better options than ordinary soaps that are too alkaline (pH 9–10). This pH extreme either disrupts the skin’s acid mantle or damages structural proteins present in skin. Proper rinsing and gently patting the skin dry add additional value to skin protection as it prevents vigorous rubbing or massaging that may lead to micro-damage of the skin and substructures10,11.

Use of skin barriers

The natural moisturising factor of skin is achieved by in-built humectants to keep the skin surface moisture content at 10% for intact skin14. Products that do not alter the pH (as bacteria thrive in an alkaline environment10) and provide a barrier from incontinence are preferable and imperative to achieve better skin restoration outcomes4–8,16,17. Moisturisers frequently used in skin protection protocols could be either in a humectant or an emollient form. Humectants are available in many forms that may contain liquid-forming acrylates, ceramides, urea, lactic acid or glycerin, with the purpose to bind water to the skin surface16,17. It may cause local stinging and burning when water is drawn from the deeper layers. If applied after washing or bathing while the skin is still damp (within 2–3 minutes), this is prevented16. Emollients, on the other hand, can be applied at any time; they prevent insensible losses of moisture from the skin surface18. Since skin damaged from IAD can be painful, products that do not sting or burn on application may be better to address patient-centred concerns of pain management.

Zinc oxide as an example of an emollient in IAD preventative care

Zinc oxide is an enhanced barrier that prevents bacteria, contact irritants (e.g. stool, urine) and allergens from penetrating the skin. In zinc oxide ointment preparations, zinc oxide is combined with petrolatum as it creates a ‘stiff’ barrier, providing additional skin adherence and protection. It is less likely to soften or migrate from the skin into any co-existing deeper wound in that same area than with the petrolatum base alone18.

The 2016 Cochrane review on the prevention and treatment of IAD in adults17 cited several trials on zinc ointment that prevented or successfully treated IAD. The zinc oxide ointments do not always need to be removed if the surface is clean, but can be left to fill in the spaces. By using a clean tongue depressor to spread the zinc oxide preparation evenly, it helps to minimise the frictional resistance on the skin often encountered in application. It is well known that the topical application of zinc on skin adds to enhancement of the local defence systems in skin against superficial infection, while increasing epithelium migration to quickly cover any small lesion in the area18. Since the German dermatologist Unna created the zinc oxide paste bandage for venous ulcers in 1895, sufficient evidence has existed on its effect on aiding skin healing, with no currently documented adverse systemic effects encountered16. Although further robust studies are needed, zinc paste preparations are known to be effective skin protectants17 and are safe enough for use on babies13.

From a practice perspective, on skin without erythema or in the presence of mild redness, a zinc oxide barrier can be applied with ease using a gloved hand or tongue depressor. If there are erosions (loss of surface epidermis with an epidermal base as opposed to a dermal or deeper base) or satellite papules or pustules indicating candidiasis, a topical antifungal agent would then be required as a first layer. The antifungal agent can be applied first to the skin as a treatment and then the protective layer of zinc oxide is added as the second layer. This often poses as a practice challenge, as application in the presence of moisture is difficult. By layering the zinc ointment on a carrier medium (either on plain gauze or on impregnated gauze if available) and then applying this carrier as a last layer upside down on the area, this challenge can be averted. If the zinc oxide wears off between episodes of incontinence, a repeat layer can be applied once or twice a day. With consistent episodes of incontinence, skin cleansing, gentle pat drying and barrier ointment application should be repeated every time as soon as the incontinence occurs10,11.

Conclusion

Healthy skin requires it to be intact and have a stratum corneum moisture content of 10%. Incontinence of stool and urine can compromise this barrier in both white and darker skinned persons while adding to susceptibility of IAD and PI development. Skin protection for all skin tones is imperative to protect darker skin against exaggerated late presentations of IAD. Zinc oxide ointment provides an evidence-based ideal skin barrier that is readily available even in the most resource restricted environments. Proper application and use thereof has sufficient evidence10 to incorporate this in skin protective strategies to prevent and treat this common skin problem, especially in the young and aging populations with incontinence issues.

Conflict of Interest

Both authors have received an educational grant from Calmoseptine to teach the WoundPedia course in Manila, Philippines.

用于防治失禁相关性皮炎(IAD)的皮肤护理可最大限度降低发生压力性损伤(PI)的易感性

Hiske Smart and R Gary Sibbald

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.4.40-44

摘要

本文稿总结了一个重要的临床概念,即制定皮肤护理方案来保护和治疗皮肤,使皮肤免于发生失禁相关性皮炎(IAD),进而防止和最大限度减少IAD与后续发生压力性损伤(PI)的关联。

必须对所有肤色进行皮肤保护,以保护皮肤免于出现IAD的增强型迟发表现。

引言

保护皮肤的屏障功能是护理工作领域中经常遇到的一个重要的临床实践作用。失禁相关性皮炎(IAD)通常涉及给患者造成严重不适,并且往往在皮肤白皙的个体中会迅速发展,在肤色较深的人群中会更迟发展,但表现形式增强;这是由于最初的临床视觉线索被掩盖,未能识别。本文作者将使用文献和临床示例的证据,强调将氧化锌糊剂作为临床环境中的一种护理方案,因为其容易获得且成本相对较低。

失禁相关性皮炎(IAD)

IAD是潮湿环境相关性皮炎(MASD)分类中包括的四种病因之一。在文献中将IAD定义为“由于长期暴露于尿液或液状粪便所发生的一种形式的刺激性接触性皮炎”1-3。研究认为病因是皮肤长期暴露于尿液或液状粪便(通常是二者兼有),导致皮肤的正常酸性pH值变为碱性pH值水平。1-6 一旦皮肤的“酸性保护膜”受损,皮肤会对尿液和/或粪便中的水分产生炎症反应(红斑),皮肤屏障可能受损1-6。

根据皮肤的天然色素沉着,红色皮肤(红斑)的外观会有所不同5。在棕色或黑色皮肤中,红斑可能不会表现为红色,而是有可能此处肤色会比周围的皮肤深,因此在检查皮肤时导致诊断困难(图1)。皮损预防始终优于治疗,但是在深色皮肤中,早期皮损通常更难检测到5,从而导致干预的启动较晚。

图1.深色皮肤中观察到的红斑及IAD与PI共存的临床表现(表格和照片 © Smart & Sibbald)

压力性损伤(PI)合并IAD

文献支持IAD与压力性损伤(PI)形成之间的关联,不过两者的病因不同7-11。Lachenbruch等人8分析了176,689例患者,发现92,889例失禁患者的PI发病率为16.3%,而非失禁人群(n=83,800)的PI发病率为4.1%。IAD与PI发病率高于仅通过Braden风险量表评分预测的结果有关。Gray和Giuliano9评价了5,342例患者,其中2,492(46.6%)例为尿失禁。他们得出结论,21.3%的IAD可能与继发性酵母菌感染、不活动和骶骨PI发病率增加有关9。

临床上,PI会表现在具有明显边界的明显骨隆突部位10。而IAD外观更加弥漫,可能出现在会阴区,并扩散到臀部区域,在长期接触失禁内容物的皮肤上引起明显的皮炎2,3,5,10。当PI和IAD共存时,IAD弥漫模式仍然为增强型8,9(图2)。 McNichol及其同事4总结了有关积极治疗IAD,以尝试减少随后发生PI的重要性相关的文献。

图2.深肤色人群中仅PI及PI与IAD共存时的临床表现(表格和照片 © Smart & Sibbald)

在最近的欧洲压疮咨询委员会、美国压力性损伤咨询委员会和泛太平洋地区压力性损伤联盟压力性损伤指南10中也记录了支持IAD/PI关联的进一步证据。关于IAD和PI共存的情况,三个指南要素对于实践至关重要。其中一个与皮肤惰性保护能力的丧失有关,陈述如下:“潮湿环境相关性皮损可能会损害表皮屏障功能,从而使组织容易发生压力性损伤”10(p.21)。另一个与在皮肤受到表面湿润环境损害的情况下,皮肤耐受额外力的能力有关:“皮肤表面潮湿环境联合压力和/或剪切力可能增加压力性损伤的发病率”10(p.86)。

但是另一项听起来可能觉得矛盾的陈述建议,在接触失禁内容物时,避免皮肤过于干燥、脱水或干裂,这些均是皮肤损伤的风险因素:

尽管还没有研究直接建立皮肤保湿与压力性损伤发病率降低之间的关联,但一项针对活动受限住院患者的流行病学研究(n=286)指出,在一项多变量分析21中,皮肤干燥是压力性损伤的一个重要的独立风险因素(预后3级)。建议在皮肤卫生方案中包含定期涂抹润肤霜,以促进皮肤水合,防止其他不良皮肤状况,包括皮肤干燥和皮肤撕

裂10(p.86)。

屏障功能和皮肤保护性干预策略

关键是要保持皮肤滋润,因为这样可以维持皮肤的保护性水分梯度4,8,12,13。在皮肤白皙的个体中,此单位保护性水分梯度是深肤色个体的三分之一(2:6)12。因此皮肤干燥是粪便所含酶和尿液尿素造成潮湿环境相关性损伤的一个风险因素,其中该损伤在皮肤白皙的人身上发生的速度要比深肤色的人快得多。角质层的质量也很重要,因为在年龄层的两个相对端,角质层最薄(幼儿13和老年人14)。治疗失禁原因的早期干预需要结合用于保护、维持和修复皮肤屏障的皮肤护理方案来实现4-8,11。

在临床实践中,至关重要的一点是,提高科室护士和非专业医护人员以及涉及患者护理的患者家属对使用适当的皮肤清洁产品的意识。教育使能器是总结关键点和向护理者提供护理基本要素相关知识的简单方法。IAD皮肤护理的教育使能器之一是使用ACT记忆符来指导临床医生实施全面的皮肤护理方法4(图3)。

图3.指导在存在IAD的情况下进行皮肤护理的临床使能器

皮肤护理方案

失禁事件后进行皮肤清洁的证据强度分级为B2,这是一种有效的干预措施,可以清除皮肤上粪便或尿液中残留的表面碎屑10。中性肥皂或富脂产品15是比碱性过强的普通肥皂

(pH 9-10)更好的选择。这种极端的pH值会破坏皮肤的酸性保护膜或损伤皮肤中存在的结构蛋白。正确冲洗并轻轻拍打使皮肤干燥,可带来保护皮肤的额外价值,因为这样可以防止可能导致皮肤和皮下结构微损伤的大力摩擦或按摩10,11。

皮肤屏障的使用

皮肤通过与生俱来的保湿成分可实现天然保湿因子,以将完整皮肤的皮肤表面含水量维持在10%14。首选不改变pH值(因为细菌在碱性环境中繁殖10)并提供失禁屏障的产品,且该产品必须实现更好的皮肤修复效果4-8,16,17。皮肤保护方案中经常使用的润肤霜可以是保湿剂或润肤剂形式。保湿剂有多种形式,可能含有液体形式的丙烯酸酯、神经酰胺、尿素、乳酸或甘油,目的是将水附着在皮肤表面16,17。当从深层取水时,可能引起局部刺痛和灼烧。如果在淋浴或沐浴后,皮肤仍然湿润(2-3分钟内)时使用,这一点是可以防止的16。而润肤剂可以在任何时候使用;它可以防止皮肤表面的不显性水分流失18。由于因IAD发生损伤的皮肤会疼痛,所以使用不刺痛或灼烧的产品可能会更好地解决以患者为本的疼痛管理问题。

氧化锌作为IAD预防性护理中润肤剂的示例

氧化锌是一种增强的屏障,可以防止细菌、接触刺激物(例如粪便、尿液)和过敏原渗入皮肤。在氧化锌软膏制剂中,氧化锌与凡士林结合,因为凡士林会形成一个“硬”屏障,提供额外的皮肤粘附和保护。与单独使用凡士林基质相比,它不太可能软化皮肤或从皮肤迁移到同一区域内任何共存的更深部伤口中18。

2016年Cochrane关于成人IAD预防和治疗的综述17引用了几项有关锌软膏预防或成功治疗IAD的试验。如果皮肤表面洁净,氧化锌软膏不一定需要去除,可以留下来填充空隙。通过使用洁净的压舌板,均匀地涂布氧化锌制剂,这有助于最大限度减少涂抹中经常遇到的皮肤摩擦阻力。众所周知,在皮肤上局部涂抹锌可以增强皮肤局部防御系统抵抗浅表感染的能力,同时增加上皮细胞的迁移,从而迅速覆盖该区域的任何小病变18。自从1895年德国皮肤科医生Unna制成氧化锌糊剂绷带治疗静脉性溃疡以来,已经有足够的证据证明它有助于皮肤愈合,目前尚未记录遇到了任何全身性不良反应16。尽管需要进一步的可靠研究,但是已知锌糊剂是有效的皮肤保护剂17,并且可足够安全地用于幼儿13。

从实践的角度来看,在没有红斑或存在轻度发红的皮肤上,可以通过戴手套的手或压舌板轻松地涂抹氧化锌屏障。如果存在糜烂(皮肤表面表皮丢失,有表皮基质而非真皮基质或更深层基质)或卫星丘疹或提示念珠菌病的脓疱,则需要先使用局部抗真菌剂作为第一层。可以先将抗真菌剂涂抹在皮肤上作为治疗剂,然后再添加氧化锌保护层作为第二层。这通常是一个实践挑战,因为在有水分的情况下很难涂抹。在载体介质(普通纱布或浸渍纱布[如可用])上涂抹一层锌软膏,然后将这个载体作为最后一层翻面放置在该区域,就可以避免这种挑战。如果氧化锌在两次失禁事件之间逐渐消失,则可以一天再敷一次或两次。在失禁持续发作的情况下,每次出现失禁事件时,应立即重复进行皮肤清洁、轻轻拍打干燥和涂抹屏障软膏10,11。

结论

健康的皮肤需要皮肤完整,角质层含水量为10%。无论是皮肤白皙的人群还是深肤色的人群,大小便失禁都会破坏这一屏障,同时增加发生IAD和PI的易感性。必须对所有肤色的人群进行皮肤保护,以保护深肤色人群免于出现IAD的增强型迟发表现。氧化锌软膏提供了一种循证的理想皮肤屏障,即使在资源最有限的环境中也很容易获得。因此,氧化锌软膏的适当涂抹和使用证据充足10,可将其纳入皮肤保护策略中,以预防和治疗这种常见的皮肤问题,特别是在有失禁问题的年轻和老年人群中。

利益冲突

两位作者都收到了Calmoseptine公司对于在菲律宾马尼拉教授WoundPedia课程的教育资助。

Author(s)

Hiske Smart*

RN, MA (Nur), Hons BSocSc (Nur), PGDip (WHTR – UK), IIWCC (Can)

Nurse Manager and Clinical Nurse Specialist – Wound Care and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Unit, King Hamad University Hospital, Kingdom of Bahrain

Secretary General – World Union of Wound Healing Societies

Email hiskesmart@gmail.com

R Gary Sibbald

BScMd, MEd, DSC (Hon), FRCPC (Med)(Derm), FAAD, MAPWCA, JM

Professor of Medicine and Public Health, University of Toronto

Director of International Interprofessional Wound Care Course (IIWCC) & Masters of Science Community Health (Prevention and Wound Care), Dalla Lana School of Public Health

Co-Editor in Chief Advances in Skin & Wound Care

Project Lead ECHO Ontario, Skin & Wound

Investigator, Institute Better Health, Trillium Health Partners

* Corresponding author

References

- Black JM, Gray M, Bliss DZ, et al. MASD part 2: incontinence-associated dermatitis and intertriginous dermatitis: a consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38(4):359–70.

- Gray M, Bliss DZ, Doughty DB, Ermer-Seltun J, Kennedy-Evans KL, Palmer MH. Incontinence associated dermatitis: a consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34(1):45–54.

- Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM, et al. Moisture-associated skin damage: overview and pathophysiology. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38(3):233–41.

- McNichol LL, Ayello EA, Phearman LA, Pezzella PA, Culver EA. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: state of the science and knowledge translation. Adv Skin and Wound Care 2018;31(11):502–513.

- Ayello EA, Sibbald RG, Quiambao PCH, Razor B. Introducing a moisture-associated skin assessment photo guide for brown pigmented skin©. WCET J 2014;34(2):18–25.

- Beeckman D. A decade of research on incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD): evidence, knowledge gaps and next steps. J Tissue Viabil 2017;26:47–56.

- Bateman SD, Roberts S. Moisture lesions and associated pressure ulcers: getting the dressing regimen right. Wounds UK 2013;9(2):97–102.

- Lachenbruch C, Ribbie D, Emmons K, Van Gilder C. Pressure ulcer risk in the incontinent patient: analysis of incontinence and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers from the International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(3):235–41.

- Gray M, Giuliano KK. Incontinence-associated dermatitis, characteristics and relationship to pressure injury: a multisite epidemiologic analysis. JWOCN 2018;45(1):63–67.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guideline. The International Guideline. Emily Haesler (Ed). EPUAP/NPIAP.PPPIA:2019.

- Park KH, Kim KS. Effect of a structured skin care regimen on patients with fecal incontinence: a comparison cohort study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(2):161–167.

- De Farias PT, Azambuja AP, Horimoto AR, et al. A population-based study of the stratum corneum moisture. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2016;9:79–87. doi:10.2147/CCID.S88485

- Shin HT. Diagnosis and management of diaper dermatitis. Pediatr Clin North Am 2014;61(2):367–382.

- Sopher R, Gefen A. Effects of skin wrinkles, age and wetness on mechanical loads in the stratum corneum as related to skin lesions. Med Biol Eng Comput 2011;49(1):97–105.

- Bou J, Segovia G, Verdu S, Nolasco B, Rueda L, Perejamo M. The effectiveness of a hyper oxygenated fatty acid compound in preventing pressure ulcers. J Wound Care 2005;14(3):117–21.

- Schuren J, Becker A, Sibbald RG. A liquid film-forming acrylate for peri-wound protection: a systematic review and meta-analysis (3MTM CavilonTM no-sting barrier film). Int Wound 2005;2:230–238.

- Beeckman D, Van Damme N, Schoonhoven L, Van Lancker A, Kottner J, Beele H, Gray M, Woodward S, Fader M, Van den Bussche K, Van Hecke A, De Meyer D, Verhaeghe S. Interventions for preventing and treating incontinence-associated dermatitis in adults. Cochrane Database System Rev 2016;11. Art. No: CD011627.

- Lansdown AB, Mirastschijski U, Stubbs N, Scanlon E, Agren MS. Zinc in wound healing: theoretical, experimental, and clinical aspects. Wound Repair Regen 2007;15(1):2–16.