Volume 41 Number 1

Management of nonhealable and maintenance wounds: A systematic integrative review and referral pathway

Geertien C. Boersema, Hiske Smart, Maria G. C. Giaquinto-Cilliers, Magda Mulder, Gregory R. Weir, Febe A. Bruwer, Patricia J. Idensohn, Johanna E. Sander, Anita Stavast, Mariette Swart, Susan Thiart and Zhavandre Van der Merwe

Keywords diabetic foot ulcer, pressure injury, pressure ulcer, venous leg ulcer, atypical wound, interprofessional team, maintenance wound, nonhealable wound, referral

For referencing Boersema GC et al. Management of nonhealable and maintenance wounds: A systematic integrative review and referral pathway. WCET® Journal 2021;41(1):21-32

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.1.21-32

Abstract

Objective This systematic integrative review aims to identify, appraise, analyze, and synthesize evidence regarding nonhealable and maintenance wound management to guide clinical practice. An interprofessional referral pathway for wound management is proposed.

Data sources An electronic search of Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Academic Search Ultimate, Africa-Wide Information, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature database with Full Text, Health Source: Consumer Edition, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, and MEDLINE was conducted for publications from 2011 to 2019. Search terms included (nonhealable/nonhealing, chronic, stalled, recurring, delayed healing, hard-to-heal) and wound types most associated with nonhealable or maintenance wounds. Published studies were hand searched by the authors.

Study selection Studies were appraised using two quality appraisal tools. Thirteen reviews, six best-practice guidelines, three consensus studies, and six original nonexperimental studies were selected.

Data extraction Data were extracted using a coding framework including treatment of underlying causes, patient-centered concerns, local wound care, alternative outcomes, health dialogue needs, challenges within resource restricted contexts, and prevention.

Data synthesis Data were clustered by five wound types and local wound bed factors; further, commonalities were identified and reported as themes and subthemes.

Conclusions Strong evidence on the clinical management of nonhealable wounds is limited. Few studies describe outcomes specific to maintenance care. Patient-centered care, timely intervention by skilled healthcare providers, and involvement of the interprofessional team emerged as the central themes of effective management of maintenance and nonhealable wounds.

General purpose

To synthesise the evidence regarding nonhealable and maintenance wound management and propose an interprofessional referral pathway for wound management.

Target audience

This continuing education activity is intended for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses with an interest in skin and wound care.

Learning objectives/outcomes

After participating in this continuing professional development activity, the participant will apply knowledge gained to:

- Identify the ideas from the authors’ systematic review that could prove useful in understanding nonhealable and maintenance wound management.

- Select evidence-based management strategies for nonhealable and maintenance wound management.

Introduction

Acute wounds follow an organised wound healing sequence and often heal between 3 and 4 weeks. When a wound is still present 4 weeks after wounding, it is defined as a chronic wound1. Many research studies have been conducted on chronic wound management to address the rising demand for effective and affordable care. The healing trajectory of chronic wounds is expected to take 12 weeks2,3. This period may be prolonged if the wound presents with an altered molecular environment, chronic inflammation or fibrosis,4 or uncorrected preexisting systemic factors1.

Patients who present with a wound not responding to conventional treatment are the topic of many best-practice guidelines using the umbrella terms “nonhealing” or “hard-to-heal5,6.” Advanced modalities such as negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT), ultrasound, laser, platelet-enriched plasma, hyperbaric oxygen (HBO), use of dermal substitutes, and reconstructive surgery are frequently advised as adjunctive intervention. Although appropriate to some wounds, there is a subgroup of patients for whom alternative approaches or endpoints are needed because advanced modalities either failed or are not feasible. This typically is the case when the patient presents with preexisting underlying systemic disease that cannot be controlled, is in need of additional physiologic support (eg, supplementary oxygen, renal dialysis), has difficulty performing activities of daily living without help, experiences financial and/or social difficulties, or lives in a resource-restricted environment without access to advanced care.

The wound bed preparation (WBP) paradigm2,7 guides wound care practitioners to determine wound healing potential as a vital first step of wound assessment. By accounting for both underlying causes and patient-centered concerns, providers can plan for realistic outcomes. The paradigm includes “problem wound” scenarios. Wounds with underlying cause(s) that cannot be corrected are categorised as nonhealable wounds (often attributable to critical ischemia, malignancy, or an untreatable underlying systemic condition)2,7.Wounds with correctable underlying cause(s) in the context of health system challenges (ie, lack of resources, skills, or expertise) or nonoptimal patient factors (ie, smoking, obesity, resistance to change) are categorised as maintenance wounds2,7.

Evidence-based guidance on nonhealable or maintenance wounds is needed. This systematic integrative review aims to identify, appraise, analyse, and synthesise evidence regarding nonhealable and maintenance wound management to guide clinical practice.

Methods

This study was granted ethical exemption (nr. 2019_19.8-5.3) by the University of South Africa Department of Health Studies Research Ethics Committee (no. REC-012714-039) because it did not involve human participants. The research question was: What is known from scientific literature regarding the management of nonhealable and maintenance wounds?

Data Sources

A subject information specialist and two authors of the study conducted a comprehensive literature search using the electronic databases Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Academic Search Ultimate, Africa-Wide Information, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature with Full Text, Health Source: Consumer Edition, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, and MEDLINE. Studies from January 2011 (when the WBP classification of healable, nonhealable, and maintenance wounds2 was established) to September 2019 (the month the search was conducted) were included. The search was not restricted by language or study methodology. Key words included (guideline* or framework* or consensus* or “care pathway*” or paradigm*), (manag* or maint* or treat*), (wound* or ulcer* or injur*) in relation to (nonheal* or chronic or stalled or recur* or “delay* healing” or “hard to heal” or “lower leg*” or “diabetic foot” or pressure or fungating). In addition to the database search, published studies were hand searched by the authors.

Study Selection

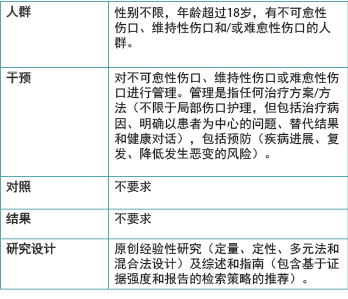

Duplicates were removed using the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Reviewer software (v 4.0; EPPI-Centre, London, England). Titles were screened by one author, followed by independent screening of abstracts by two authors according to selection criteria (Table 1). In addition, a hard-to-heal category was created to facilitate the sorting of studies on stalled nonhealing chronic wounds for wounds that failed to heal but were not yet defined as either a maintenance or nonhealable wound1,4. Two authors independently examined the full-text publications for relevance to the study question and consulted with a third author if they could not reach a consensus.

Publications not meeting the selection criteria (Table 1) were excluded. Investigators also excluded editorials, discussions, corporate education papers, expert opinions not validated by a Delphi process, case studies, case series, and retrospective study designs because of methodology concerns. Non-English articles were excluded if not followed by English translation.

Table 1. Selection criteria

Quality Appraisal

Two-author appraisals were done independently for each study using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses8 and the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (v 1.49)for best-practice guidelines, consensus documents, and original studies. A user manual guided the correct use of each quality appraisal tool. The minimum threshold for inclusion for each tool was set at 60% average. A third author was involved if the two scores differed by more than 20%, and the two highest scores were used.

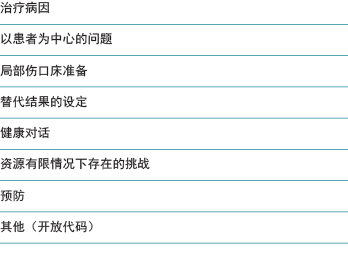

Data Extraction

The final set of included articles was distributed among groups of two or three authors responsible for a wound type and independently co-coding study data. Coding framework topics (Table 2) were collaboratively developed by the research team from the work of authors in the field of study2,7,10-15. Deductive coding focused on extracting relevant content from the results, discussion, and/or conclusion sections of each included article.

Table 2. Coding framework topics

Data Synthesis

Coded sections were clustered into a table to provide a comprehensive overview of evidence by topic and wound type. The teams met in November 2019 to provide a summary of the main findings for each wound type to the whole group. A second analysis was conducted by the three senior authors to identify and describe commonalities (themes) by comparing the extracted information.

Results

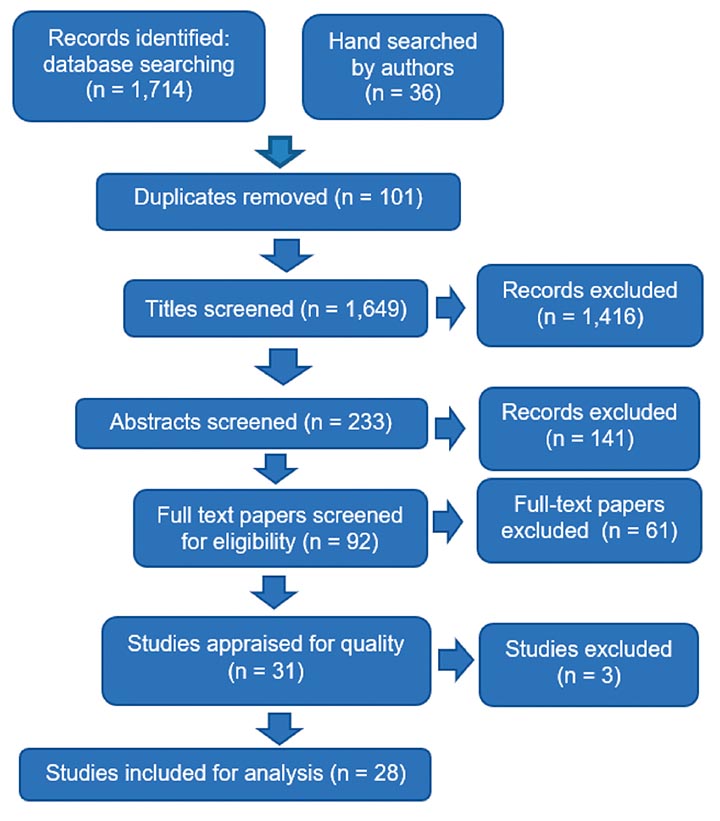

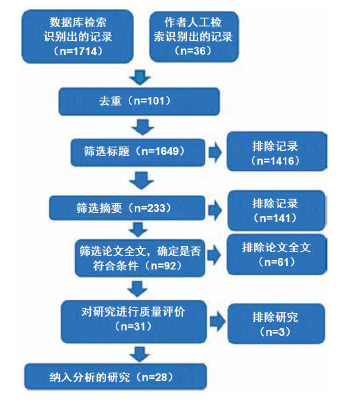

The literature search yielded 1,714 records, and the hand search, 36 records. There were 233 relevant titles, with 92 abstracts relevant to the research question. After examining the full-text articles, 61 were excluded. In the remaining 31 studies, three scored less than 60% on the quality appraisal tools. The quality appraisal scores and the strengths and weaknesses of each included study (n = 28) are summarised in Supplemental Table 1 (click here); the flow of the selection process is depicted in Figure 116.

Figure 1. Study selection

Researchers analysed 13 reviews, 6 best-practice guidelines,

3 consensus studies (based on Delphi techniques), and 6 original studies (1 multimethod and 5 nonexperimental, descriptive, and/or correlational quantitative designs). No randomised controlled trials were identified. The characteristics of the included studies are outlined in Supplemental Tables 2 (click here), 3 (click here), and 4 (click here).

Data Synthesis and Theme Identification

This section reports a summary of the extracted data from the included studies for five wound types: malignant fungating wounds (MFWs), lower leg ulcers (LLUs), diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), pressure injuries (PIs), and atypical wounds. Three articles focused on local wound bed interventions and are summarised separately.

Malignant Fungating Wounds. Two studies on MFWs were included and addressed the effect of topical agents and dressings on quality of life (QoL) for people with MFWs17 and resilience when living with a wound18.

Adderley and Holt17 did not find evidence on the effect of dressings on QoL. Weak evidence suggests the use of 6% miltefosine topical solution or foam dressings with silver on superficial wounds could delay disease progression and reduce malodour17. Evidence supporting the use of honey-coated dressings is not sufficient17.

Ousey and Edwards18 identified pain and fatigue as barriers to maintaining health-related QoL (HRQoL). Practitioners must acknowledge the emotional needs of patients with MFWs who may experience destructive feelings and feelings of avoidance. Loss of bodily function control also impedes the ability to cope with the disease18. Persons living with an MFW want to be informed about physical limitations and psychological consequences (such as sudden hemorrhage), and they appreciate advice on wound management18.

Lower Leg Ulcers. Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) account for up to 80% of all LLUs19, which accounts for the eight articles included on VLUs: two reviews20,21 and one consensus study22 on compression therapy, one review3 and one guideline on the holistic management of VLUs19, one quantitative survey on VLU management24, and one cohort study on sustained behavior change following a client education program25, and one review on cost-effectiveness26. The ninth article, a review by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), provided evidence on arterial ulcers and mixed etiology ulcers, reporting the lack of current consensus on optimal wound management for mixed arterial-venous ulcers27. All nine studies used the terms nonhealing chronic wounds or wounds with extended time to healing (>12 weeks).

A consensus-based algorithm recommends that ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI) should be used for its high specificity in detecting peripheral arterial disease (PAD) as an underlying cause in LLUs22 and that significant PAD requires immediate referral to a vascular surgeon19,21,27. However, a survey among nurses identified a significant knowledge-translation gap regarding ABPIs24.

All the evidence supports compression therapy as key to VLU management19-23,27. However, guidelines advise against compression therapy in the presence of significant PAD or pulmonary edema, but do recommend immediate referral to a vascular assessment service19,21,27. The included studies support modified compression carefully monitored by a well-trained clinician for mild PAD (ABPI 0.5-0.8) and standard compression therapy in the absence of PAD19-22.

The included guideline argues that chronic, hard-to-heal VLUs can be transformed into acute wounds by means of debridement once PAD is excluded, malignancy ruled out, and other inflammatory comorbidities accounted for19. All studies supported the WBP paradigm for maintenance wounds7,22,23. When LLUs are not healing as expected, providers should reassess the patient at least every 12 weeks for other potential causes and repeat the ABPI measurement20,22. Further, NPWT is not indicated for healable VLUs over topical modalities; it is effective for securing a skin graft in hard-to-heal wounds, but not as a modality on its own23. There is substantial evidence on the efficacy of electrical stimulation as an adjunctive modality in VLU to achieve healing progress23.

Venous leg ulcers significantly impact social and physical functioning; pain is particularly prominent in the ulcerative phase or with secondary infection19. Only one of the included studies recommends dressings for local pain relief, but concludes that compression therapy remains the key to pain control19.

Effective VLU management requires sustained behavior change19,22,25. Patient education should include leg health, emphasis on regular activity, the role of pharmaceuticals, the importance of compression, optimal positioning of legs during rest, promotion of a healthy diet and adequate hydration, and skin care. Nonadherence to modifying lifestyle factors may lead to extended healing times or nonhealing22,25. Positive behavior change was achieved via e-learning in a prospective single sample cohort study25. Recurrence of VLU is common, and strong evidence supports use of stockings as primary prevention to improve the aching and itching associated with venous insufficiency22.

Carter26 reviewed the cost-effectiveness of new or evidence-based intervention systems versus routine care to guide decision-making. One study in this review (an unblinded randomised controlled trial of moderate evidence strength) concluded that four-layer compression bandages resulted in faster healing versus the control group (standard care) with consequent financial cost savings. However, they also reported compression bandage application skill to be a key factor in achieving positive VLU outcomes26. Another key message from this review was that a multidisciplinary team managing VLUs achieved faster healing by 36.5 days in the intervention group with consequent financial cost savings.

Diabetic Foot Ulcers. These ulcers are classified as hard-to-heal wounds; expected healing trajectories are often missed because of patient factors or healthcare resource limitations28. One systematic review discussing NPWT for DFUs,29 one original study30, and four guidelines31-34 were included in this portion of the review. The guidelines and original study addressed holistic management of DFUs with one discussing HBO33.

Two guidelines recommended that PAD should be assessed to establish healability because DFUs can become nonhealable wounds with inadequate perfusion, rendering those patients unsuitable candidates for revascularisation31,32. Such nonhealable wounds might result in amputation because of increased infection risk30.

Glycemic control of and nutrition support for diabetes to enhance wound healing are supported by strong levels of evidence.31 When addressing the cause of DFUs, plantar pressure redistribution (offloading) is the key to success32. The guidelines further recommended that DFUs should be debrided to reduce biologic load and risk of infection when adequate blood supply is present31,32. In hard-to-heal wounds with inadequate perfusion, debridement should be conservative31. Infection should be treated systemically, especially with a positive probe-to-bone test. When surgery is not an option, systemic antibiotic treatment should be prolonged (6 to 8 weeks)31. There is insufficient evidence for topical antibiotics in these wounds, and their use is associated with increased local and systemic microbial resistance31. Dressing choice should take into consideration the condition of the wound and surrounding skin32.

One guideline suggests strong evidence for HBO as adjunctive therapy for the treatment of Wagner stage 3 DFUs33. Further, a review by the CADTH concluded that DFUs treated with NPWT showed significantly reduced ulcer areas, healing time, and the need for secondary/major amputation when compared with DFUs not treated with NPWT29. These modalities may be indicated in hard-to-heal DFUs but are not recommended for maintenance of nonhealable wounds.

The general review from Ousey and Edwards18 also included three quantitative studies that reported on the psychological effects of living with a DFU. They found a lower HRQoL with a decline in physical and social functioning among a group of 35 patients living with a DFU compared with a group of 15 persons with diabetes without a wound. Further, depression was related to development of the first DFU among a group of 333 participants and was a persistent risk factor for mortality and presented a 33% increased risk of amputations18.

Clinicians attending to patients with DFUs must have the necessary skills and equipment to accurately and holistically assess and treat them31. All of the guidelines included in this study strongly recommend an interprofessional approach to treating DFUs because of their complex nature31-34. These teams should address factors such as patient-centered concerns, access to care, financial limitations, and foot and self-care31,32.

Pressure Injuries. Four studies were included in this portion of the review: one cross-sectional observational design,35 two reviews36,37, and one guideline38. Gelis et al37 stressed that PIs are “not a chronic disease but rather a complication in cases of immobility,” suggesting that PI evolution and prognosis correlate with the contexts in which such injuries and wounds occur; that is, PIs may evolve as maintenance or nonhealing wounds according to the underlying pathology. Guihan and Bombardier35 concluded that the complex underlying comorbidities among persons with slow healing and stage 3 and 4 PIs require an interprofessional approach. Early and aggressive management of acute and chronic PIs may prevent or change the development cycle of hard-to-heal or maintenance wounds over time35.

Fujiwara et al38 included studies focusing on diagnosis and treatment of stage 1-4 PIs. They support pressure and shear forces as underlying causes and strongly recommend pressure relief with position changes every 2 hours and the use of appropriate pressure-relieving mattresses (based on strong evidence). Pain control is an important aspect of patient-centered concerns to improve the HRQoL of patients with PIs. Some evidence in the review suggests pressure-relieving mattresses and specific wound dressings (eg, soft silicone, alginate, and hydrogels). Evidence for the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and/or psychotropic drugs exists, but is weak.38 Their recommendation to debride devitalised tissue was for healable wounds where the cause could be corrected. For hard-to-heal, maintenance, or nonhealable PIs, no recommendation on debridement could be drawn from the evidence. Surgery may remain as an option once the underlying cause can be corrected and the condition of the patient improved.

In the presence of deep infection, a systemic antibiotic is suggested using a positive bacterial culture from the wound bed to guide treatment38. In addition, signs of persistent inflammation in the periwound area, pyrexia, an increased white blood cell count, or worsening of the inflammatory reaction should be addressed38. A comprehensive assessment of the patient, the wound bed, and periwound area should be conducted to diagnose wound infection. The CADTH did not find evidence to support specific wound dressings and stated: “one dressing will be as good as the other36.”

Gelis et al37 reviewed evidence on patients with chronic neurologic impairment at risk of PI and suggested continuing therapeutic education for older adults, persons with spinal cord injuries, and others at risk37. They also recommend several pedagogic models for use based on the learning style of the specific patient and involving the circle of care in prevention. Providers should support patient self-management of multiple chronic conditions, because several comorbidities often occur simultaneously in persons with slow-healing PIs35.

Atypical Wounds. Four articles were included in this part of the review. These referred to Buruli ulcer, hidradenitis suppurativa, epidermolysis bullosa, and vasculitis- and autoimmune-associated wounds. These wounds present with unusual signs and symptoms and/or locations and do not heal within 4 to 12 weeks, and often the underlying conditions are difficult to manage in clinical practice.

In a Ghanaian Buruli ulcer prospective observational study, the authors found that earlier wound closure (less than 12 weeks) was more likely in primary healthcare settings compared with secondary settings despite a lack of resources, staff incompetency, and high patient loads39. This was attributed to earlier presentation, smaller wounds, better nutrition status, better patient adherence to treatment, and intact social support. Wound closure failure occurred in primary healthcare in the presence of underlying complications, such as osteomyelitis, squamous cell carcinoma, chronic lymphedema, and infection. In the secondary healthcare setting, nutrition deficiency, venous and arterial insufficiency, lymphedema, and malignant deterioration were associated with impaired wound healing. This was mostly attributable to poor hygiene and deficient skills and resources leading to recurrent wound infection. Failure to heal became predictable between weeks 2 and 4.

Alavi et al40 explored hidradenitis suppurativa patient-centered concerns related to sexuality. This observational two-legged cross-sectional study found both men and women with HS experience negative impacts on their QoL. Men experienced sexual performance issues and women experienced sexual distress because of the location of these painful exuding lesions.

The epidermolysis bullosa study reports an expert consensus of recommendations for practice41. The main recommendations included active interventions to control persistent inflammation leading to malignancy; an interprofessional team approach to assessment, identification, and management of underlying factors; delicate management of blisters; optimisation of nutrition status with attention to albumin and hemoglobin levels; use of healing trajectory indicators to predict healing potential; and the importance of a skin edge biopsy in recalcitrant wounds to rule out squamous cell carcinoma.

Shanmugam et al42 review the evaluation and management of hard-to-heal wounds associated with vasculitis and autoimmune etiologies. Wounds not responding to local care and appropriate vascular intervention may have an underlying vasculitis or autoimmune disorder present. An interprofessional team can facilitate the required underlying systemic disease investigation. Skin graft failure should prompt high provider suspicion of vasculitis; an edge biopsy may be helpful to confirm diagnosis42.

Local Wound Bed Factors. Three articles addressed local wound bed issues prevalent in problem wounds regardless of type and addressed malodour, the nonhealing spiral, and maggot debridement therapy (MDT).

Akhmetova et al43 aimed to summarise studies focusing on odour control in chronic wound management. Five control measures with substantial evidence were identified. Metronidazole gel was most extensively studied; five studies reported it reduced odour, exudate, and pain. Topical silver (and silver sulfadiazine use) was included because it is not deemed an antibiotic but rather an antimicrobial agent. Four studies supported its use because of its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effect on the wound bed. Charcoal is known to absorb gases, bacteria, and liquids; one study supported its use. Medical-grade honey for odour control was mentioned in three studies, and research on topical cadexomer iodine use in VLUs reported odour reduction as a secondary outcome43.

Schultz et al44 published a guideline for the identification and treatment of chronic nonhealing wounds. “Nonhealing” is not defined in the article in terms of a time frame or underlying cause, but in general as chronic wounds not healing in a timely fashion despite optimal intervention. A key recommendation is the initial use of aggressive debridement in combination with topical antiseptics and systemic antibiotics followed by a step-down approach until healing44. A consensus statement indicates that this recommendation is relevant for aggressive management of wounds that might have some potential for healing44. Further research is required to evaluate the effectiveness, validity, reliability, and reproducibility of the algorithms available to diagnose and treat biofilm. Further exploration into different wound types will be necessary to provide a clear guide on definite signs and symptoms associated with biofilm in the wound bed; for example, ischemic ulcers may not manifest the same signs and symptoms of biofilm because of the lack of blood flow44.

Sherman45 provided a summary of MDT and recommendations on when to initiate it as modality. The author concluded that MDT has three broad actions: debridement, disinfection, and tissue growth stimulation, although the focus was on debridement. The chemical debridement occurs via alimentary secretions and excretions containing digestive enzymes, inhibiting microbial growth and biofilm formation. Further, this action induces maturation of monocytes and neutrophils from proinflammatory cells into their angiogenic phenotype, which could lift the wound out of the inflammatory phase45. Therefore, MDT is of value as an adjunctive modality in addressing local wound bed factors in hard-to-heal wounds to counteract stalled wound growth, but it is contraindicated in dry wounds because maggots need moisture to survive.

Discussion

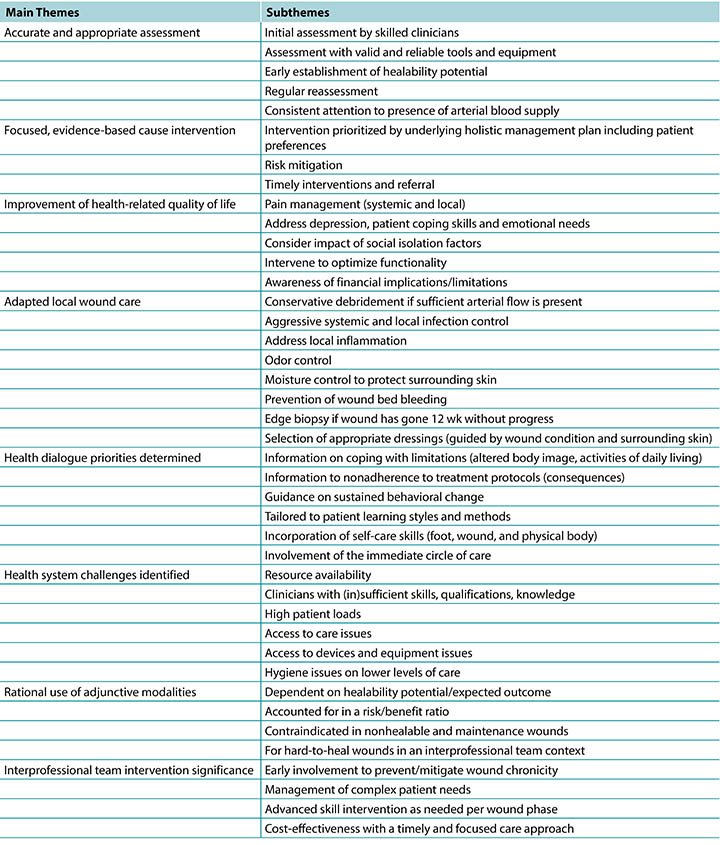

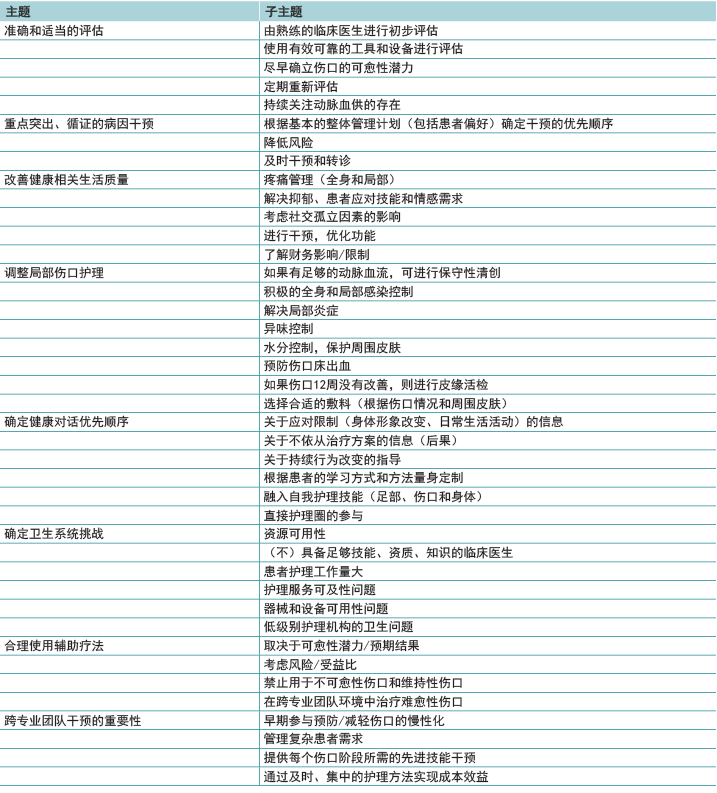

Despite the proposed definition/classification of wounds into healable, maintenance, and nonhealable by Sibbald et al2, very few authors used those terms in publications, a concern also voiced by Olsson et al46. Common terms were “chronic,” “nonhealing,” “slow healing,” or “atypical,” all with limited reference to wound duration, healing time, or alternative outcomes. This led to authors’ extraction of available data elements into an additional “hard-to-heal” category, allowing for inclusion where healing time or the influence of underlying causes was not described. However, despite the lack of clear definitions, this study identified similarities in management across the different hard-to-heal wound types, and these commonalities encompass the following themes (Table 3).

Table 3. Main themes and subthemes identified

Accurate and Appropriate Assessment. Early identification of underlying conditions and skillful attention to existing patient and system factors are essential to promote healing at an optimal rate (decreasing 30% in size within 4 weeks)10. Providers must determine healability (within the first 12 weeks) and use valid assessment tools. A systematic and comprehensive approach to history taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigations to reach a clear diagnosis improves outcomes39. Lack of adequate blood supply remains a major underlying cause present in most nonhealing or maintenance wounds and should be assessed regularly19,21,24,27. Depression is strongly associated with the onset of DFUs, and if left untreated, increases subsequent amputation and mortality risk18. Providers should actively screen and prioritise intervention and appropriate treatment for depression in patients with long-duration wounds18.

Focused, Evidence-Based Cause Intervention. Adequate cause identification and initiating corrective interventions to mitigate underlying causes early in the wound healing sequence could prevent wound conversion. The substantial list of direct deficits that add to local wound deterioration and chronicity includes osteomyelitis, squamous cell carcinoma, chronic lymphedema, and wound infection39, and these conditions require intervention or aggressive control to recreate and establish wound bed progression or stability. A hard-to-heal, stalled, or atypical wound should prompt an edge biopsy including the reticular dermis and subcutaneous tissue to assess pathology41. Providers should strive for early classification of nonhealable wounds when underlying causes cannot be effectively treated or are deemed uncorrectable47, with an accompanying shift in focus toward palliation and HRQoL.

Improve HRQoL. Chronic wounds lead to personal, financial, social, psychosocial, and sexual adaptations beyond simply coping with the effects of the wound. Critically, depression is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes18. The benefits of consistent attention to pain management are a key finding in most of the evidence reviewed18, and multiple pain types may require polypharmacy interventions. It is vital to recognise and manage patient-centered concerns with a focus on improving HRQoL by maintaining activities of daily living and addressing ambulation48, self-reliance18, knowledge translation, and self-esteem17,18. Patient-centered concerns should be prioritised as highly as underlying causes because the impact of wound healing on HRQoL may be hidden or dormant, which in turn negatively impacts healing.

Adapted Local Wound Care. Appropriate interventions regarding tissue, infection and inflammation, moisture, and edge management remain a cornerstone of local wound care. Different debridement approaches may range from careful and conservative removal of devitalised tissue31,32, puncturing blisters and not deroofing41, to surgical debridement to remove biofilm or advance edges39,44. These authors recommend careful conservative debridement, which should be performed only by skilled practitioners if adequate arterial blood supply is present to support the wound bed and surrounding tissue.

Aggressive infection control should include actions to treat and prevent recurring superficial and deep wound infection44,45,48, including assessment of the patient’s vital and metabolic status, wound bed, and periwound area. The topical application of any antibiotic preparation such as ointments or creams (eg, gentamicin, fusidic acid, mupirocin) is not recommended by the International Wound Infection Institute because of global concern about antibiotic resistance and the subsequent systemic resistance49. Addressing malodour with appropriate dressings is recommended43 and may be included after a risk analysis on the additional moisture added to a wound bed. Providers and patients should keep nonhealing and maintenance wound beds as dry as possible23 to preserve tissue22; to protect the edges against trauma41, bacterial invasion44, and moisture-related skin breakdown18,26; and prevent further tissue loss or wound expansion. These results provided clear guidance on the edge effect; wound area reductions less than 20% to 40% in 2 to 4 weeks could be a reliable predictor of nonhealing39. That is, providers should not wait 12 weeks without wound edge progress to intervene.

Health Dialogue Priorities. Patients need to understand their situation fully and be guided to self-reliance18. Education should accommodate different learning styles with attention to modifiable risk factors (smoking, poor glycemic control, and resistance to lower limb compression). Health dialogue is strongly associated with financial cost savings26. eLearning platforms (mobile phone, social media) are powerful patient education tools and facilitate health dialogue that incorporates the patient’s care circle in a culturally and patient-appropriate manner. Online learning strategies that include pressure redistribution, nutrition supplementation, skincare, and incontinence care could effectively incorporate the family into the care circle with cost containment as an additional outcome26. The value of targeted patient learning may be further enhanced via the financial benefits of DFU prevention26.

Health System Challenges. This review identified sets of professional skills, or the lack thereof, which impact wound-related outcomes and healing times. These include assessment (ABPI in LLUs22,DFU grading33) and correct clinical management (application of compression bandages20-22, initial foot pressure redistribution32). Lack of provider expertise is an often-overlooked iatrogenic factor in hard-to-heal or stalled wounds24 that leads to loss of valuable time, additional wound complications, and late referral to an interprofessional team for advanced intervention. Recognizing limitations is vital in early referral to a skilled practitioner/interprofessional team.

However, in resource-restricted or rural settings, interprofessional teams may not be feasible, emphasizing the importance of wound care knowledge for all providers. In fact, limited resources leading to delayed healing is a factor often overlooked in the literature. The review by Carter26 supports the cost-effectiveness of guideline-driven versus standard care for chronic wounds. Early identification of maintenance wounds may prevent the prolonged use of resources despite the lack of progress22,26, which could in turn positively impact treatment-associated costs for both the patient and healthcare system.

In the future, the prevention of skin breakdown regardless of wound etiology may be the highest priority of any healthcare professional because of the direct cost saving associated with skin-protective strategies7,22,26. This is evident in PI and DFU prevention, where early intervention and prevention are frequently measured by key performance indicators (incidence and prevalence data50)to save skin from repetitive breakdown and prevent amputations51.

Rational Use of Adjunctive Modalities. In the hands of the interprofessional team, last-resort adjunctive wound therapies (NPWT, HBO, flap/graft surgery, electrostimulation, MDT)23,27,33,45 have the best potential to promote healing when patient issues, wound history, and resource limitations are accounted for in hard-to-heal wounds. However, most advanced modalities are not a viable adjunctive option for maintenance and nonhealable wounds with dry23 or bleeding wound beds18 and may not represent the most optimal use of resources22,26.

Interprofessional Team Approach Significance. The most important finding (present in the majority of the included studies) was that an early interprofessional approach can facilitate correct interventions and wound management

options19,21,26,27,31,32,35,41,42. This timely and accurate intervention may prevent downward spirals into chronicity.18,31-33,35,41,42 Assessment, diagnosis, and appropriate interventions for slow healing or stalled wounds often require advanced wound care skills19-22,27 more readily available in an interprofessional team. Evidence supports this intervention as cost-effective compared with standard routine care over prolonged periods of time26.

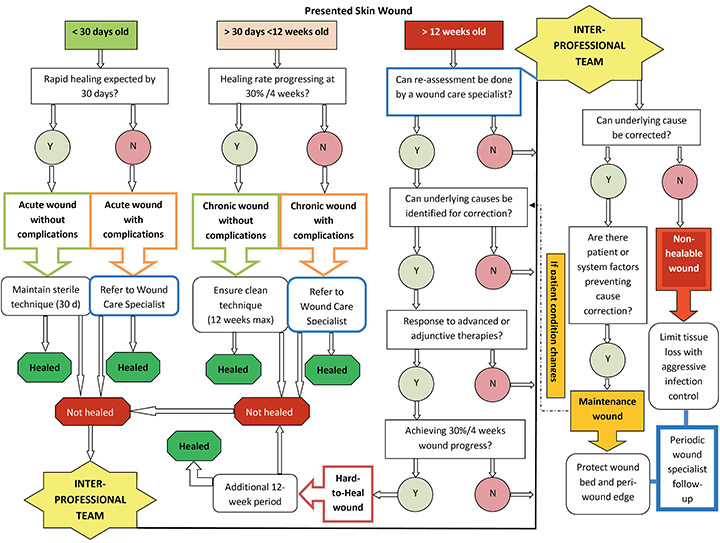

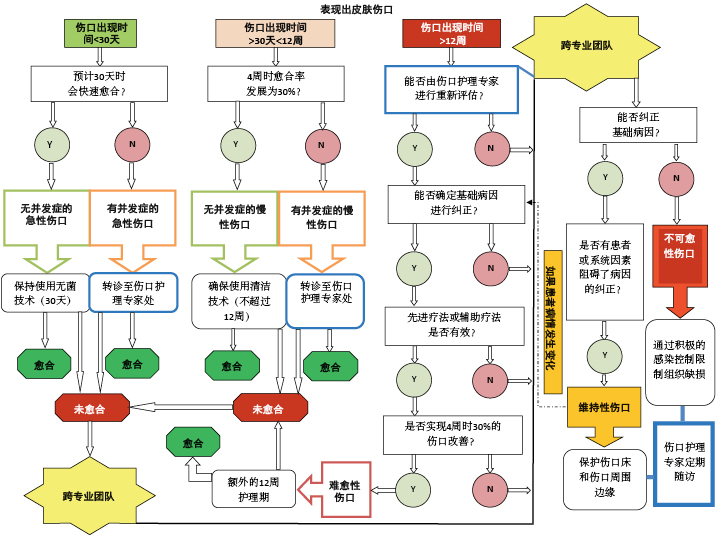

Despite this strong recommendation, the interprofessional team is often a last resort and utilised too late to break the cycle of slow healing and chronicity. Patients are vital members of the interprofessional team because they dictate the potential of the team to achieve set outcomes, especially if faced with prolonged healing22. However, clinicians may still struggle to determine when it is appropriate to consult with an interprofessional team. For this reason, the authors developed an interprofessional referral pathway using time- and wound-related markers that may indicate the appropriate time to involve the interprofessional team (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Interprofessional team referral pathway for patients with wounds

The clinician should enter the pathway according to the relevant “time since wounding” in the top horizontal line. Once that box is identified, the decision-making process follows a vertical line downward to an outcome and time frame for that outcome to be achieved. Note that the interprofessional team takes responsibility for diagnosis of maintenance and nonhealable wounds to ensure that no wound lands or remains in those categories unnecessarily.

Definitions: Wound care specialist: a healthcare professional (doctor/nurse/allied health) with additional training and specialization in wound care, part of a functioning interprofessional team. Sterile technique: prevention of bacterial contamination and infection spread by adherence to strict sterile procedural protocol when performing wound-related procedures. Sterile-to-sterile rules apply. Clean technique: also known as nonsterile technique: involves hand washing, a clean environment with a clean field set, clean gloves, and sterile instruments aiming to prevent direct contamination of supplies or material. Acute and chronic wound risk factors: impaired vascular supply, underlying systemic disease, trauma, immune compromise, extensive tissue loss, exposed bone or tendon, patient adherence to treatment issues, patient in need of additional intervention(s), lack of appropriate resources/skills. Advanced/adjunctive therapies: maggot debridement, negative pressure, and hyperbaric oxygen therapies; electrostimulation; ultrasound; laser; platelet-enriched plasma; surgical closure; interventional radiology, etc. Healed outcome—acute wound healed within 30 days; chronic wound healed within 12 weeks (followed 30%/4 weeks’ edge advancement); allowance for additional 12-week period(s) for hard-to-heal wounds as determined by the interprofessional team.

Note: Nonhealable wound could also be a first entry point without any flow through the rest of the pathway, with confirmation from the interprofessional team.

Interprofessional Referral Pathway

In doing this review, the research team realised that hard-to-heal wounds follow a typical sequence of events attributable to provider, patient, payer, policy, or persistent uncorrected underlying factors52,53 rather than being a wound type per se. Essentially, hard-to-heal wounds have specific needs and are an additional category in the process of determining healability:

- healable: where healing occurs predictably according to expected time frames;

- hard-to-heal: where slow, stalled, or nonhealing wounds are in need of additional assessment or care modalities;

- maintenance: where health dialogue for lifestyle modification becomes more important than achieving a wound healing outcome;

- nonhealable: where aggressive attention to local infection prevention and preservation against further tissue loss is needed and no wound healing outcome can be achieved.

It became clear from compiling data elements into themes that prompt identification of wound healing failure is a priority. The complex factors affecting wound healing should be routinely reassessed, and providers should maintain a flexible perspective on the healing trajectory. In current literature, the exact expected time to healing (ie, a defined cutoff point when wounds are classified as maintenance wounds) remains elusive. With this in mind, the research team proposes a referral pathway with specific time frames to help health professionals in decision-making (Figure 2). Timely referral could lead to optimal intervention in the vital early period of wounding and promote available adjunctive interventions when positive outcomes can still be attained.

The pathway proposes that hard-to-heal wounds be granted another 12 weeks of optimal wound care to achieve healing (30% decrease rate within 4 weeks). If the wound does not progress despite advanced team intervention, it can then be classified as a maintenance wound (where patient or system issues prevent cause correction)2. Reassessment and management by wound care specialists fully trained to apply current best evidence and well-positioned on an interprofessional wound care team are critical. The proposed additional 12 weeks of aggressive interprofessional management should be further explored and tested in future research. These studies could consider interventions with or without advanced wound care modalities because such modalities may not be available in resource-restricted contexts.

Limitations

This review was limited to studies from 2011 to 2019 and only considered evidence prior to 2011 if it was included in the selected studies. Guidelines not identified through the search could be of value if the guidelines clearly and transparently report the identification and appraisal of the evidence. Further, key words for specific atypical wounds were not included in the search. This was done to extract studies focused on maintenance and nonhealable wound interventions as well as to limit the yield. However, studies on atypical wounds were hand searched by the research team but had small sample sizes and paucity of evidence.

This study did not include case studies or case series, but the investigators acknowledge that multiple case studies could be the highest level of evidence available in challenging cases or environments. A future review of existing case studies/case series could prove of value to identify current practicalities when dealing with this subgroup of wounds. Studies on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of local wound bed innovations in resource-restricted contexts would be a valuable contribution and more so if conducted in real-life clinical settings and in collaboration with academics and practitioners.

Conclusions

Active patient involvement in the care process is critical to manage a maintenance or nonhealable wound and achieve acceptable outcomes. Once a nonhealable, maintenance, or hard-to-heal wound is identified, not only should a full reassessment be made by a skilled team of healthcare professionals, but focused clinical interventions such as an edge biopsy or advanced vascular assessment should confirm the wound classification and guide patient and provider decision-making.

Evidence on the exact clinical management of maintenance and nonhealable wounds is insufficient to guide practice. The most common findings were the need for early diagnosis and prompt treatment within the first 12 weeks, comprehensive identification of underlying factors delaying healing, and early involvement of the interprofessional team. An interprofessional referral pathway was developed to incorporate an additional 12-week intervention period in hard-to-heal or late-referral wounds.

If wound assessment reveals a maintenance or nonhealable wound, it is important to realise that this diagnosis will impact the patient on physical, personal, interpersonal, social, and financial levels. The main priority should be to preserve patient integrity in these arenas with a focused patient-centered intervention. Long-term pain management should be prioritised. Further, patient preparation with focused health dialogue is vital to identify and facilitate life adaptations needed and cope with this diagnosis. The incorporation of newly learned or adapted skills into the patient’s own activities of daily living will positively impact QoL. Patients with maintenance, nonhealing, and hard-to-heal wounds should take responsibility for their own self-care where possible and for as long as possible.

Practice pearls

- A wound that does not heal at a rate of 30% per week should be reassessed by an interprofessional team sooner rather than later; do not wait 12 weeks before referral.

- Hard-to-heal wounds, or those that stall over time, may benefit from an interprofessional team’s intervention that may include reassessment and a change of treatment strategy to address the underlying cause of the wound.

- Once diagnosed with a maintenance wound, patients need to be empowered with sufficient knowledge and social/family support to maintain activities of daily living and self-care as long as possible.

- The holistic management of both maintenance and nonhealable wounds involves shifting focus away from achieving wound outcomes and toward addressing patient-centered concerns such as pain management and odour control.

- The clinical focus for nonhealable wounds should include aggressive topical infection control to achieve tissue stability, preservation of existing stable dry tissue, and prevention of wound edge expansion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brinsley Davids, Liezl Naude, Michelle Second, Valana Skinner, and Liz Morris, who participated in the initial phase of the study; Dr Alwiena Blignaut from North West University for her guidance with the methodology and critical review of this article; Dr Annatjie Van der Wath for providing training on principles of qualitative analysis; and Dr Nick Kairinos for critical review of this article. The Wound Healing Association of Southern Africa sponsored the subscription fee for the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Reviewer software. No other project funding was received. The author, faculty, staff, and planners, including spouses/partners (if any), in any position to control the content of this CME/CNE activity have disclosed that they have no financial relationships with, or financial interests in, any commercial companies relevant to this educational activity.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.ASWCjournal.com).

To earn CME credit, you must read the CME article and complete the quiz online, answering at least 7 of the 10 questions correctly. This continuing educational activity will expire for physicians on December 31, 2022, and for nurses March 4, 2022. All tests are now online only; take the test at http://cme.lww.com for physicians and www.nursingcenter.com for nurses. Complete CE/CME information is on the last page of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口的管理:系统性综合综述和转诊路径

Geertien C. Boersema, Hiske Smart, Maria G. C. Giaquinto-Cilliers, Magda Mulder, Gregory R. Weir, Febe A. Bruwer, Patricia J. Idensohn, Johanna E. Sander, Anita Stavast, Mariette Swart, Susan Thiart and Zhavandre Van der Merwe

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.1.21-32

摘要

目的 本系统性综合综述旨在识别、评价、分析和整合有关不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口管理的证据,从而指导临床实践。本文提出了伤口管理的跨专业转诊路径。

数据来源 对斯高帕斯数据库(Scopus)、汤森路透科学网(Web of Science)、PubMed、综合学科参考文献大全-旗舰版(Academic Search Ultimate)、非洲研究索摘数据库(Africa-Wide Information)、护理与联合卫生文献累积索引全文数据库(Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature database with Full Text)、健康资源-消费者版、健康资源-护理/学术版和MEDLINE数据库进行电子检索,检索了2011年至2019年发表的出版物。检索词包括(nonhealable/nonhealing、chronic、stalled、recurring、delayed healing、hard-to-heal)与和不可愈性或维持性伤口最相关的伤口类型。作者还对已发表的研究进行了人工检索。

研究选择 使用两种质量评价工具对研究进行了评价。选择了十三篇综述、六篇最佳实践指南、三篇共识研究和六篇原创非实验性研究。

数据提取 使用编码框架提取数据,包括基础病因的治疗、以患者为中心的问题、局部伤口护理、替代结果、健康对话需求、资源有限情况下存在的挑战和预防。

数据整合 按五种伤口类型和局部伤口床因素对数据进行聚类;此外,还确定了共同之处,并以主题和子主题的形式进行了报告。

结论 关于不可愈性伤口临床管理的有力证据有限。很少有研究描述专门针对维持性伤口护理的结果。以患者为中心的护理、技能娴熟医护人员的及时干预以及跨专业团队的参与是有效管理维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口的核心主题。

总体目的

本文旨在整合有关不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口管理的证据,并提出伤口管理的跨专业转诊路径。

目标受众

本次持续教育活动的预期对象是对皮肤和伤口护理感兴趣的医生、医生助理、执业护士和护士。

学习目标/结果

在参加本次持续专业发展活动后,参与者将运用所学知识:

1. 从作者的系统性综述中发现对了解不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口管理有用的观点。

2. 选择针对不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口管理的循证管理策略。

引言

急性伤口会遵循系统的伤口愈合顺序,通常在3至4周内愈合。如果伤口在受伤4周后仍存在,则属于慢性伤口1。为满足对有效且价格亲民的护理日益增长的需求,许多作者已进行了慢性伤口管理研究。慢性伤口的愈合轨迹预计需要12周2,3。如果伤口出现分子环境改变、慢性炎症或纤维化表现,4或未纠正之前预先存在的全身因素,该愈合期还可能会延长1。

存在常规治疗无效伤口的患者是许多最佳实践指南的主题,这些指南使用涵盖性术语“不愈性”或“难愈性”5,6。经常建议的辅助干预措施包括负压伤口治疗(NPWT)、超声、激光、富血小板血浆、高压氧疗法(HBO)、使用真皮替代物和重建手术等先进疗法。尽管这些疗法适用于某些伤口,但仍存在因为先进疗法失败或不可行而需要替代方法或终点的患者亚组。这种情况通常出现在患者预先存在无法控制的全身性基础疾病、需要额外的生理支持(例如,补充氧气、肾透析)、在没有帮助的情况下难以进行日常生活活动、经历经济和/或社会困难,或生活在资源有限的环境中而无法获得先进护理之时。

伤口床准备(WBP)范例2,7指导伤口护理执业医护人员确定伤口愈合的潜力,以此作为伤口评估的重要第一步。通过考虑基础病因和以患者为中心的问题,医护人员可以为现实结果做出计划。该范例包括“问题伤口”场景。基础病因无法纠正的伤口归类为不可愈性伤口(通常归因于严重缺血、恶性肿瘤或不可治疗的全身性基础疾病)2,7。在存在卫生系统挑战(即缺乏资源、技能或专业知识)或不理想的患者因素(即,吸烟、肥胖、抗拒改变)的情况下,基础病因可纠正的伤口归类为维持性伤口2,7。

需要制定针对不可愈性伤口或维持性伤口的循证指导。本系统性综合综述旨在识别、评价、分析和整合有关不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口管理的证据,从而指导临床实践。

方法

由于本研究不涉及人类受试者,因此获得了南非大学健康研究部研究伦理委员会(编号:REC-012714-039)的伦理豁免(编号:2019_19.8-5.3)。研究问题是:关于不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口的管理,从科学文献中了解到了什么?

数据来源

本研究的一位学科信息专家和两位作者使用斯高帕斯数据库、汤森路透科学网、PubMed、综合学科参考文献大全-旗舰版、非洲研究索摘数据库、护理与联合卫生文献累积索引全文数据库、健康资源-消费者版、健康资源-护理/学术版以及MEDLINE等电子数据库进行了全面的文献检索。纳入了2011年1月(确立可愈性、不可愈性和维持性伤口2的WBP分类的时间)至2019年9月(进行检索的月份)期间发表的研究。检索不受语言或研究方法的限制。关键词包括(guideline* or framework* or consensus* or “care pathway*” or paradigm*)、(manag* or maint* or treat*)、(wound* or ulcer* or injur*),涉及(nonheal* or chronic or stalled or recur* or “delay* healing” or “hard to heal” or “lower leg*” or “diabetic foot” or pressure or fungating)。除数据库检索外,作者还对已发表的研究进行了人工检索。

研究选择

使用Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Reviewer软件(v 4.0;EPPI-Centre,英国伦敦)进行去重。一位作者筛选了标题,随后两位作者根据选择标准(表1)对摘要进行独立筛选。此外,还创建了一个难愈性伤口类别,以便对有关慢性停滞不愈性伤口的研究进行分类,这些伤口未能愈合,但尚未被定义为维持性伤口或不可愈性伤口1,4。两位作者独立检查了出版物全文,确定与研究问题的相关性,如果不能达成共识,则咨询第三位作者。

排除了不符合选择标准(表1)的出版物。由于方法学方面的考虑,研究者还排除了编者按、讨论、企业教育论文、未经德尔菲法验证的专家意见、病例研究、病例系列和回顾性研究设计。排除了未随附英文翻译的非英文文章。

表1.选择标准

质量评价

对于最佳实践指南、共识文件和原创研究,两位作者使用乔安娜•布里格斯研究所系统性综述和研究整合关键评价清单8和Crowe关键评价工具

(v 1.49)对每项研究进行独立评价。用户手册指导每种质量评价工具的正确使用。设定的每种工具的最低纳入阈值为平均60%。如果两个分数相差超过20%,则第三位作者参与评价,并采用最高的两个分数。

数据提取

最终的纳入文章数据集在由两位或三位作者组成的各个小组中进行分配,每个小组负责一种伤口类型并独立共同编码研究数据。编码框架主题(表2)是由研究团队根据研究领域内作者们的研究成果2,7,10-15合作制定而成。演绎式编码注重从每篇纳入文章的结果、讨论和/或结论部分提取相关内容。

表2.编码框架主题

数据整合

将各个已编码部分聚合到一个表格中,以便按主题和伤口类型提供证据的全面概览。各团队于2019年11月召开会议,向整个团队提供每种伤口类型的主要结果摘要。三位资深作者进行了第二次分析,通过比较提取的信息来确定和描述共同之处(主题)。

结果

文献检索得到1714条记录,人工检索得到36条记录。共有233个相关标题,其中92篇摘要与研究问题相关。检查全文后,排除了61篇文章。在剩下的31篇研究中,有三篇通过质量评价工具获得的分数低于60%。研究选择过程的流程如图1所示16。

图1.研究选择

研究人员分析了13篇综述、6篇最佳实践指南、3篇共识研究(基于德尔菲法)和6篇原创研究(1篇多元法研究和5篇非实验性、描述性和/或相关性量性研究设计)。未发现随机对照试验。

数据整合和主题确定

本部分报告了从五种伤口类型的纳入研究中提取的数据摘要,这些伤口类型包括:恶性蕈状伤口(MFW)、下肢溃疡(LLU)、糖尿病足溃疡(DFU)、压力性损伤(PI)和非典型伤口。有三篇文章关注局部伤口床干预,单独进行了总结。

恶性蕈状伤口。纳入了两篇关于MFW的研究,这些研究探讨了外用药物和敷料对MFW患者生活质量(QoL)的影响17,以及患者在伤口持续存在情况下生活的韧性18。

Adderley和Holt17没有发现敷料对QoL产生影响的证据。薄弱证据表明,在浅表伤口上使用6%米替福新外用溶液或含银泡沫敷料可以延缓疾病进展,并减少恶臭17。支持使用蜂蜜涂层敷料的证据尚不充足17。

Ousey和Edwards18发现,疼痛和疲劳是维持健康相关QoL(HRQoL)的障碍。执业医护人员必须认识到MFW患者的情感需求,这些患者可能会出现消极情绪和回避情绪。身体功能控制的丧失也妨碍了应对疾病的能力18。MFW患者希望了解生理上的限制和心理上的后果(如突发出血)并获得关于伤口管理的建议18。

下肢溃疡。下肢静脉性溃疡(VLU)占所有LLU19的高达80%,因此关于VLU的纳入文章多达八篇,包括:关于加压疗法的两篇综述20,21和一篇共识研究22、关于VLU整体管理的一篇综述3和一篇指

南19、关于VLU管理的一篇定量调查24、关于客户教育项目后持续行为改变的一篇队列研究25,以及关于成本效益的一篇综述26。第九篇文章是加拿大药物和卫生技术局(CADTH)的综述,提供了动脉性溃疡和混合病因溃疡的证据,报告称目前缺乏有关动静脉混合性溃疡最佳伤口管理的共识27。所有九篇研究均使用了慢性不愈性伤口或愈合时间延长的伤口(>12周)这一术语。

基于共识的算法推荐使用踝肱压力指数(ABPI),利用其高特异性特点来检测外周动脉疾病(PAD)作为LLU22基础病因的情况,如果存在严重PAD,需要将患者立即转诊到血管外科医生处进行治疗19,21,27。然而,一项对护士的调查发现了一个关于ABPI的明显知识转化差距24。

所有的证据均支持加压疗法是VLU管理的关键19-23,27。但指南建议在出现严重PAD或肺水肿时不要进行加压治疗,而是推荐立即转诊至血管评估服务处19,21,27。纳入的研究支持由训练有素的临床医生仔细监测轻度PAD(ABPI 0.5-0.8)症状的改良加压疗法,以及在没有PAD的情况下进行标准加压治

疗19-22。

纳入的指南认为,一旦排除了PAD和恶性肿瘤,其他炎症合并症也有因可循,即可通过清创将慢性难愈性VLU转化为急性伤口19。所有的研究均支持针对维护性伤口的WBP范例7,22,23。当LLU愈合未达预期时,医护人员应至少每12周重新评估患者的其他潜在病因,并重复测量ABPI20,22。此外,对于可愈性VLU,NPWT并不优先于外用疗法而适用;它对于将皮肤移植物固定在难愈性伤口上是有效的,但它本身并不是一种治疗方法23。有实质性证据证明了在VLU中使用电刺激作为一种辅助疗法来实现愈合过程的有效性23。

下肢静脉性溃疡会显著影响社会功能和生理功能;疼痛在溃疡期或存在继发感染时尤为突出19。纳入的研究中只有一篇文章推荐使用敷料缓解局部疼痛,但结论是加压疗法仍然是控制疼痛的关键19。

有效的VLU管理需要持续的行为改变19,22,25。患者教育应包括下肢健康、强调定期活动、药物的作用、加压治疗的重要性、休息时下肢的最佳位置、提倡健康饮食和保证充足的水分,以及皮肤护理。不依从改变生活方式的各个因素可能导致愈合时间延长或者不愈合22,25。在一项前瞻性单样本队列研究中,通过电子学习实现了积极的行为改变25。VLU复发也十分常见,有力的证据支持使用长袜作为初级预防,以改善与静脉功能不全相关的疼痛和搔痒22。

Carter26综述了新的干预系统或循证干预系统相对于常规护理的成本效益,从而指导决策。该综述中的一项研究(一项中等证据强度的未设盲随机对照试验)得出结论,与对照组(标准护理)相比,使用四层加压绷带的患者愈合更快,从而节省了经济成本。然而,这项研究也报告称加压绷带使用技能是实现正面的VLU结果的一个关键因素26。该综述提供的另一个关键信息是,管理VLU的多学科团队在干预组中实现了减少36.5天的更快愈合,从而节省了经济成本。

糖尿病足溃疡。这类溃疡被归类为难愈性伤口;通常会由于患者因素或医疗资源有限,错过预期的愈合轨迹28。综述的本部分包括一篇讨论NPWT治疗DFU的系统性综述29、一篇原创研究30,以及四篇指南31-34。指南和原创研究均探讨了DFU的整体管理,其中一篇文章讨论了HBO33。

有两篇指南推荐对PAD进行评估,以确定伤口可愈性,因为DFU可能因灌注不足而成为不可愈性伤口,从而使得这些患者不适合进行血运重建31,32。由于感染风险增加,此类不可愈性伤口可能会导致截肢30。

有力的证据水平支持对糖尿病进行血糖控制和营养支持,以促进伤口愈合。31 处理DFU的病因时,足底压力重新分配(减轻压力)是成功的关键32。指南进一步推荐,当血液供应充足时,应对DFU进行清创,以降低生物负载和感染风险31,32。对于灌注不足的难愈性伤口,应进行保守性清创31。应对感染进行系统性治疗,尤其是探骨试验呈阳性时。当不能选择手术时,应延长全身抗生素治疗(6~8周)31。支持在这类伤口中使用外用抗生素的证据尚不充足,其使用会造成局部和全身微生物耐药性增加31。敷料的选择应考虑到伤口和周围皮肤的状况32。

一篇指南提出了HBO作为Wagner 3级DFU治疗辅助疗法的有力证据33。此外,由CADTH进行的一项综述得出结论,与未接受NPWT治疗的DFU相比,接受NPWT治疗的DFU显示溃疡面积、愈合时间和二期截肢/大截肢的需求量显著减少29。这些疗法可能适用于难愈性DFU,但不推荐用于不可愈性伤口的维持。

Ousey和Edwards18的综述还包括三篇量性研究,报告了DFU患者在生活中的心理影响。他们发现,与15例无伤口的糖尿病患者组相比,35例DFU患者组在生活中的HRQoL较低,生理功能和社会功能下降。此外,在包含333例受试者的研究组中,抑郁症与首次患上DFU相关,且是死亡的一个持续存在的风险因素,并且截肢风险增加了33% 18。

护理DFU患者的临床医生必须具备必要的技能和设备,以准确、全面地评估和治疗这类患者31。由于DFU的复杂性,本研究中纳入的所有指南均强烈推荐采用跨专业的方法来治疗DFU31-34。这些团队应解决以患者为中心的问题、护理服务可及性、经济限制以及足部和自我护理等因素31,32。

压力性损伤。综述的本部分包括四篇研究:一篇横断面观察性设计研究35、两篇综述36,37和一篇指

南38。Gelis等人37强调,PI“不是一种慢性疾病,而是在卧床不动情况下产生的一种并发症”,这表明PI的发展和预后与此类损伤和伤口发生的背景相关;即,根据基础病理,PI可能会发展为维持性或不愈性伤口。Guihan和Bombardier35得出结论,需要采取跨专业方法治疗愈合缓慢及3期和4期PI患者的复杂基础合并症。急性和慢性PI的早期积极管理可能会预防或改变随着时间的推移发展为难愈性伤口或维持性伤口的周期35。

Fujiwara等人38纳入了关注1期-4期PI诊断和治疗的研究。他们支持压力和剪切力是基础病因,并强烈推荐每2小时变换体位进行压力释放,以及使用适当的泄压床垫(基于有力的证据)。为了改善PI患者的HRQoL,疼痛控制是以患者为中心的问题的一个重要方面。综述中的一些证据提到了泄压床垫和特定伤口敷料(例如,软聚硅酮、藻酸盐和水凝

胶)。有关使用非甾体抗炎药和/或精神药物的证据确实存在,但尚不充足。38他们推荐的对失活组织进行清创的做法适用于病因可纠正的可愈性伤口。对于难愈性、维持性或不可愈性PI,不能从证据中得出有关清创的推荐。一旦基础病因能够得到纠正,患者的病情得到改善,手术仍可作为一种治疗方案。

在存在深部感染的情况下,建议使用全身抗生素,利用伤口床的阳性细菌培养物来指导治疗38。此外,应对伤口周围区域持续炎症、发热、白细胞计数升高或炎症反应恶化等症状进行处理38。应对患者、伤口床和伤口周围区域进行全面评估,以诊断伤口感染情况。CADTH未发现支持特定伤口敷料的证据,并指出:“敷料之间的效果一样好”36。

Gelis等人37综述了关于存在PI风险的慢性神经损伤患者的证据,并建议对较年长成人、脊髓损伤患者和其他存在风险的人群进行持续治疗教育37。他们还根据特定患者的学习方式推荐了几种教学模式,并让护理圈参与预防。医护人员应支持患者自我管理多种慢性病症,因为愈合缓慢的PI患者通常会同时发生多种合并症35。

非典型伤口。综述的本部分纳入四篇文章。这些文章提到了布鲁里溃疡、化脓性汗腺炎、大疱性表皮松解症、血管炎相关伤口和自身免疫性疾病相关伤口。这些伤口出现不寻常的体征和症状和/或部位,并且在4至12周内未愈合,而且基础疾病在临床实践中往往难以管理。

在加纳的一项布鲁里溃疡前瞻性观察性研究中,作者发现,尽管资源缺乏、医护人员能力不足和患者护理工作量大,但与二级医疗环境相比,初级医疗环境更有可能实现更早的伤口闭合(不到12周)39。这是因为伤口出现的时间较早,伤口较小,营养状况较好,患者对治疗的依从性较好,社会支持完整。在存在骨髓炎、鳞状细胞癌、慢性淋巴水肿和感染等基础并发症的情况下,初级医疗环境中发生了伤口无法闭合的情况。在二级医疗环境中,营养缺乏、静脉和动脉功能不全、淋巴水肿和恶性恶化与伤口愈合受损有关。这主要是由于卫生状况较差、技能和资源不足导致伤口感染复发。在第2周至第4周时,可以预测到伤口无法愈合。

Alavi等人40研究了以化脓性汗腺炎(HS)患者为中心的与性行为有关的问题。这项双组观察性横断面研究发现,HS男性患者和女性患者均经历了对其QoL的负面影响。由于这些疼痛性渗液病变的位置,男性出现性表现的问题,女性出现性生活困扰。

大疱性表皮松解症研究报告了有关推荐实践的专家共识41。主要推荐包括:积极干预以控制导致恶变的持续炎症;采用跨专业团队方法评估、确定和管理基础因素;专门对水疱进行管理;注意白蛋白和血红蛋白水平,优化营养状况;使用愈合轨迹指标预测愈合潜力;在顽固性伤口中进行皮缘活检,排除鳞状细胞癌非常重要。

Shanmugam等人42综述了血管炎和自身免疫性病因相关难愈性伤口的评价和管理。局部护理和适当的血管干预无效的伤口可能存在基础血管炎或自身免疫性疾病。跨专业团队可促进所需的全身基础疾病调查。皮肤移植失败应向医护人员提示很可能疑似血管炎;皮缘活检可能有助于确诊42。

局部伤口床因素。三篇文章探讨了各种类型的问题伤口中普遍存在的局部伤口床问题,并讨论了恶臭、不愈性螺旋式恶化和蛆虫清创治疗(MDT)。

Akhmetova等人43旨在总结慢性伤口管理中异味控制的相关研究。确定了五种具有实质性证据的控制措施。有关甲硝唑凝胶的研究最为广泛;五项研究报告称其减少了异味、渗出液和疼痛。外用银

(和磺胺嘧啶银)包括在内,因为它不是抗生素,而是抗菌剂。四项研究支持其使用,因为其对伤口床具有抗菌和抗炎作用。众所周知,木炭可以吸收气体、细菌和液体;一项研究支持其使用。在三项研究中提到了医用级蜂蜜用于异味控制,关于在VLU中外用卡地姆碘的研究将异味减少作为次要结果报

告43。

Schultz等人44发表了一份针对确定和治疗慢性不愈性伤口的指南。在该文中,没有根据时间框架或基础病因对“不愈性”进行定义,而是将它总体定义为尽管进行了最佳干预,仍未及时愈合的慢性伤口。一个关键的推荐是首先使用积极的清创术联合外用抗菌剂和全身抗生素,然后采取用量逐步减少的方法,直到伤口愈合44。一项共识陈述表明,该推荐对可能具有一定愈合潜力的伤口的积极管理相

关44。需要进一步的研究来评价可用于诊断和治疗生物膜的算法的有效性、效度、可靠性和再现性。有必要对不同的伤口类型进行进一步的探索,以便对与伤口床生物膜相关的明确体征和症状提供明确的指导;例如,缺血性溃疡可能不会表现出与由于血流不足而出现的生物膜相同的体征和症状44。

Sherman45对MDT进行了总结,并就何时开始MDT治疗提出了推荐。作者的结论是,MDT有三大作用:清创、杀菌和刺激组织生长,不过重点是清创。化学清创通过含有消化酶的消化道分泌物和排泄液进行,可抑制微生物生长和生物膜形成。此外,这种作用诱导单核细胞和中性粒细胞成熟,从促炎性细胞成为其血管生成表型,这可以使伤口避免经历发炎期45。因此,MDT作为一种辅助疗法,在治疗难愈性伤口中的局部伤口床因素,进而消解伤口生长停滞方面具有价值,但其在干燥伤口中禁止使用,因为蛆虫需要水分才能存活。

讨论

尽管Sibbald等人2提出了可愈性伤口、维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口相关的定义/分类,但很少有作者在发表文章时使用这些术语,Olsson等人46也表达了这个问题。常见的用词是“慢性”、“不愈性”、

“愈合缓慢”或“非典型”,所有这些用词都很少提及伤口持续时间、愈合时间或替代结果。这使得本文作者将可用的数据元素提取到一个额外的“难愈性伤口”类别中,以便在文章未描述愈合时间或基础病因影响的情况下将其纳入。然而,尽管缺乏明确的定义,本研究发现了不同的难愈性伤口类型在管理上的相似之处,这些共同之处包括以下主题

(表3)。

表3.确定的主题和子主题

准确和适当的评估。尽早确定基础疾病并熟练关注现有的患者和系统因素对于促进最佳速度的愈合至关重要(在4周内伤口大小减少30%)10。医护人员必须确定伤口可愈性(在前12周内),并使用有效的评估工具。采取系统而全面的方法进行病史采集、体检和实验室检查,进而获得明确的诊断,可改善患者结果39。血供不足仍然是大多数不愈性伤口或维持性伤口中存在的主要基础病因,应进行定期评估19,21,24,27。抑郁与DFU的发作具有非常强的关联性,如果不加以治疗,会增加随后的截肢和死亡风险18。医护人员应积极筛查并优先考虑对存在长期伤口的患者的抑郁进行干预和适当治疗18。

重点突出、循证的病因干预。充分确定病因并在伤口愈合过程的早期采取纠正性干预来缓解基础病因可以防止伤口转化。增加局部伤口恶化和慢性化的直接缺陷众多,这个清单包括骨髓炎、鳞状细胞癌、慢性淋巴水肿和伤口感染39,这些病症需要干预或积极控制,以便重建和建立伤口床的改善或稳定性。难愈性伤口、愈合停滞伤口或非典型伤口应进行皮缘活检(包括网状真皮和皮下组织),以评估病理41。当基础病因无法有效治疗或认为不可纠正时47,医护人员应努力对不可愈性伤口进行早期分类,同时将重点转向姑息治疗和HRQoL。

改善HRQoL。慢性伤口会导致个人、财务、社会、心理和性生活方面的适应问题,而不仅仅是应对伤口的影响。至关重要的是,抑郁与糖尿病患者的发病率和死亡率增加有关18。在综述的大多数证据中发现的一个关键结果是持续注意疼痛管理的受益18,多种疼痛类型均可能需要多重用药干预。认识和管理以患者为中心的问题至关重要,重点是通过维持日常生活活动和解决步行48、自力更生18、知识转化和自尊问题17,18来改善HRQoL。以患者为中心的问题应与基础病因置于同样地位进行优先考虑,因为伤口愈合对HRQoL的影响可能是隐蔽性的或潜伏的,这反过来又会对愈合产生负面影响。

调整局部伤口护理。关于组织、感染和炎症、水分和伤口边缘管理的适当干预仍然是局部伤口护理的基石。不同的清创方法可包括谨慎保守地去除失活组织31,32、刺破水疱而不去顶41,到进行手术清创以去除生物膜或进展边缘39,44。这些作者推荐使用谨慎保守性清创术,只有当有充足的动脉血供来支持伤口床和周围组织时,才应由技能娴熟的执业医护人员进行清创。

积极的感染控制应包括治疗和预防复发性浅表和深部伤口感染的措施44,45,48,包括评估患者的生命和代谢状态、伤口床和伤口周围区域。国际伤口感染研究所不推荐外用任何抗生素制剂,例如软膏或乳膏(如庆大霉素、夫西地酸、莫匹罗星),这是因为全球都担心抗生素耐药性和随之导致的全身耐药性49。推荐使用适当的敷料解决恶臭问题43,并可在对增加伤口床额外湿度进行风险分析后纳入敷料的使用。医护人员和患者应保持不愈性伤口床和维护性伤口床尽可能23干燥,以保护组织22;保护伤口边缘免受创伤41、细菌侵染44和潮湿环境相关性皮肤皲裂18,26;并防止进一步的组织缺损或伤口扩大。这些结果提供了有关边缘效应的明确指导;在2至4周内伤口面积减少小于20%至40%可能是伤口不愈合的可靠预测因素39。也就是说,医护人员不应该在伤口边缘没有改善的情况下等待12周后再进行干预。

健康对话优先事项。患者需要充分了解自己的情况,在引导下自力更生18。患者教育应适应不同的学习方式,关注可改变的风险因素(吸烟、血糖控制不佳、下肢加压阻力)。健康对话与节省经济成本具有非常强的关联性26。电子学习平台(手机、社交媒体)是患者教育的强大工具,有助于以符合患者文化和患者需求的方式,进行融入患者护理圈的健康对话。包括压力重新分配、营养补充、皮肤护理和失禁护理在内的在线学习策略可以有效地将家庭纳入护理圈,并带来控制成本的额外结果26。DFU预防所带来的经济效益可能进一步增加了针对性的患者学习的价值26。

卫生系统挑战。本综述确定了其存在或缺乏会影响伤口相关结果和愈合时间的一系列专业技能。这些包括评估(LLU的ABPI22、DFU分级33)和正确的临床管理(使用加压绷带20-22、初始足部压力重新分

配32)。医护人员专业知识的缺乏是难愈性伤口或愈合停滞伤口中一个经常被忽视的医源性因素,24这会导致浪费宝贵的时间,增加伤口并发症并延迟转诊至跨专业团队进行先进干预的时间。认识到局限性对于尽早转诊到技能娴熟的执业医护人员/跨专业团队处至关重要。

然而,在资源有限的环境或乡村环境中,跨专业团队可能无法配置,这就强调了伤口护理知识对所有医护人员的重要性。事实上,资源有限导致延期愈合是文献中经常忽略的一个因素。Carter26的综述支持对慢性伤口进行指南驱动的护理相对于标准护理的成本效益。尽早确定维持性伤口可以防止在缺乏改善的情况下对资源的长期使用22,26,这反过来可以对患者和医疗系统的治疗相关成本产生积极影响。

在未来,无论伤口病因如何,预防皮肤皲裂都可能是所有专业医护人员的最高优先事项,这是因为皮肤保护策略会带来直接成本节省7,22,26。这一点在PI和DFU的预防中显而易见,其早期干预和预防经常通过关键性能指标(发病率和患病率数据50)来加以衡量,此类措施可避免皮肤反复皲裂并预防截肢51。

合理使用辅助疗法。当难愈性伤口是由患者问题、伤口病史和资源有限导致时,将患者交给跨专业团队能保证作为最终手段的辅助伤口疗法(NPWT、HBO、皮瓣/移植手术、电刺激、MDT)23,27,33,45具有促进愈合的最佳潜力。然而,对于有干燥23或出血伤口床18的维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口,多数先进疗法不是可行的辅助治疗方案,并且可能不代表资源的最佳使用22,26。

跨专业团队方法的重要性。最重要的研究发现(存在于所纳入的大多数研究中)是早期的跨专业方法可以促进使用正确的干预和伤口管理方案19,21,26,27,31,32,35,41,42。这种及时准确的干预可以防止螺旋式下行恶化为慢性化。18,31-33,35,41,42 对于愈合缓慢或停滞的伤口,评估、诊断和适当的干预通常需要先进的伤口护理技能19-22,27,这在跨专业团队中更容易获得。有证据支持这种干预与长期标准常规护理相比具有成本效益26。

尽管受到强烈推荐,但跨专业团队往往是作为最终手段,而且利用得太晚,无法打破愈合缓慢和慢性化的周期。患者是跨专业团队的重要成员,因为患者决定了团队实现设定结果的潜力,尤其是在面临较长愈合期的情况下22。然而,临床医生可能仍难以确定何时适宜咨询跨专业团队。因此,本文作者使用时间和伤口相关的标志物制定了一个跨专业转诊路径,这可指示跨专业团队参与的适当时间(图

2)。

跨专业转诊路径

在进行本综述时,研究团队意识到难愈性伤口遵循可归因于医护人员、患者、支付者、政策或持续未纠正的基础因素52,53等典型事件序列,而不是伤口类型本身。本质上,难愈性伤口有特定的需求,是确定可愈性过程中的一个额外类别:

1. 可愈性:根据预期的时间框架,可预测会发生愈合;

2. 难愈性:愈合缓慢、愈合停滞或不愈性伤口,需要额外的评估或护理方法;

3. 维持性:改变生活方式的健康对话变得比实现伤口愈合结果更为重要;

4. 不可愈性:需要积极关注局部感染的预防和保护,以防止进一步的组织缺损,并且无法实现伤口愈合结果。

从将数据元素编制成主题的过程中可以清楚得知,及时确定伤口无法愈合是一个优先事项。应定期重新评估影响伤口愈合的复杂因素,医护人员应该保持灵活视角看待愈合轨迹。在目前的文献中,精确的预期愈合时间(即将伤口归类为维持性伤口的规定临界点)仍不清楚。考虑到这一点,研究团队提出了一个有具体时间框架的转诊路径,以帮助专业医护人员进行决策(图2)。及时转诊可以在伤口变化的关键早期阶段进行最佳干预,并在仍可获得积极结果时促进可用辅助干预的使用。

图2.针对有伤口患者的跨专业团队转诊路径

临床医生应根据顶部水平线中的相关“伤口出现时间”进入路径。一旦确定了该框,决策过程就沿着一条垂直线向下延伸到一个结果以及实现该结果的时间框架。需要注意的是,跨专业团队负责对维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口进行诊断,以确保没有任何伤口不必要地落在或留在这些类别中。

定义:伤口护理专家:在伤口护理领域接受过额外培训和专业训练的专业医护人员(医生/护士/综合医疗保健人员),是一个有效的跨专业团队的一部分。无菌技术:在进行伤口相关操作时,严格遵守无菌操作方案,防止细菌污染和感染传播。无菌到无菌规则(Sterile-to-sterile rules)适用。洁净技术:又称非无菌技术,包括洗手、有设置为洁净区的洁净环境、洁净手套和无菌器械,以防止直接污染物资或材料。急性和慢性伤口的风险因素:血运受损、全身性基础疾病、创伤、免疫损害、广泛组织缺损、显露的骨骼或肌腱、患者对治疗的依从性问题、患者需要额外干预、缺乏适当的资源/技能。先进/辅助疗法:蛆虫清创、负压和高压氧疗法;电刺激;超声;激光;富血小板血浆;手术闭合;介入放射等。愈合结果 - 急性伤口在30天内愈合;慢性伤口在12周内愈合(在4周时伤口边缘改善为减少30%后);对于难愈性伤口,经跨专业团队确定,允许增加12周的额外护理期。

注:经跨专业团队确认后,不可愈性伤口也可作为上图的第一个入口点,不经其他路径。

该路径建议对难愈性伤口再进行12周的最佳伤口护理,以实现愈合(4周内伤口面积减少率达

30%)。如果伤口在先进团队干预下仍无改善,则可将其归类为维持性伤口(患者或系统问题阻碍了病因的纠正)2。由经过充分培训、能够应用当前最佳证据并在跨专业伤口护理团队中处于良好地位的伤口护理专家进行重新评估和管理至关重要。建议的额外12周的积极跨专业管理应该在未来的研究中进行进一步的探索和测试。这些研究可以考虑采用或不采用先进伤口护理方法的干预措施,因为在资源有限的情况下可能无法获得此类方法。

局限性

本综述仅限于2011年至2019年发表的研究,仅在相关证据包含在所选研究中的情况下,才考虑了2011年之前的证据。如果指南明确清晰地报告了证据的确定和评价,则通过检索未发现的这样的指南可能会具有价值。此外,检索中不包括特定非典型伤口的关键词。这样做是为了提取侧重于维持性和不可愈性伤口干预的研究,同时也是为了限制文献产出量。不过,研究团队对非典型伤口的相关研究进行了人工检索,但样本量较小,证据匮乏。

本研究未纳入病例研究或病例系列,但研究者承认,在具有挑战性的病例或环境中,多个病例研究可能是可用的最高水平证据。未来对现有病例研究/病例系列的综述可能对于确定在处理本研究伤口亚组时的当前实践做法具有价值。在资源有限的情况下,对局部伤口床护理创新的有效性和成本效益进行研究将是一项有价值的贡献,如果是在真实世界中的临床环境中进行研究,并与学术界和执业医护人员合作,则更有价值。

结论

患者积极参与护理过程对于管理维持性伤口或不可愈性伤口并实现可接受的结果至关重要。一旦确定为不可愈性伤口、维持性伤口或难愈性伤口,不仅应由熟练的专业医护人员团队进行全面的重新评估,而且也应通过皮缘活检或先进血管评估等重点临床干预措施确认伤口的分类,并指导患者和医护人员的决策。

关于维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口精确临床管理的证据尚不足以指导实践。最常见的研究结果是需要在第一个12周内尽早诊断和及时治疗,全面确定延迟愈合的基础因素,以及由跨专业团队尽早参与。本研究制定了一种跨专业转诊路径,对难愈性或延迟转诊伤口增加额外的12周干预期。

如果伤口评估显示为维持性伤口或不可愈性伤口,重要的是要认识到这一诊断将在生理、个人、人际、社会和经济层面对患者产生影响。主要的优先事项应该是通过以患者为中心的有针对性的干预来保持患者在这些方面的完整性。应优先考虑长期疼痛管理。此外,通过有重点的健康对话进行患者准备对于确定和促进所需的生活适应以及应对这一诊断至关重要。将新学习或适应的技能融入患者的日常生活活动中将对QoL产生积极影响。存在维持性伤口、不愈性伤口和难愈性伤口的患者应尽可能承担起自我护理的责任,并尽可能长期地坚持自我护理。

要点

• 如果伤口不能以每周30%的速率愈合,则应尽早由跨专业团队进行重新评估;不要等12周后再转诊。

• 难愈性伤口或随着时间的推移而发生愈合停滞的伤口可能会受益于跨专业团队为处理伤口的基础病因而进行的干预(可能包括重新评估和改变治疗策略)。

• 一旦诊断为维持性伤口,患者需要获得足够的知识和社会/家庭支持,以尽可能长期地维持日常生活和自我护理活动。

• 对维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口的整体管理均包括将重点从实现伤口结果转移到解决以患者为中心的问题上,如疼痛管理和异味控制。

• 不可愈性伤口的临床重点应包括积极的局部感染控制,以实现组织稳定性,保留现有稳定的干燥组织,并防止伤口边缘扩张。

致谢

作者感谢Brinsley Davids、Liezl Naude、Michelle Second、Valana Skinner和Liz Morris,他们参与了研究的初始阶段;感谢来自西北大学的Alwiena Blignaut博士对本文方法和评论性综述的指导;感谢Annatjie Van der Wath博士提供定性分析原则的培训;感谢Nick Kairinos博士对本文的评论意见。南非伤口愈合协会(Wound Healing Association of Southern Africa)赞助了Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Reviewer软件的会员费。未获得其他项目资助。作者、教职员、工作人员和计划人员(包括配偶/伴侣[如有])等有任何立场控制本CME/CNE活动内容的人士均已披露,他们与本教育活动相关的任何商业公司均没有财务关系或财务利益。

本论文提供了补充性数字化内容。直接URL引用见印刷文本,而且在该期刊网站(www.ASWCjournal.com)上本文的HTML和PDF版本中提供。

如果要获得CME学分,您必须阅读CME文章并完成在线测验,并正确回答10个问题中的至少7个问题。这项持续教育活动将于2022年12月31日对医生截止,对护士则于2022年3月4日截止。现在所有的测验均仅能在线完成,医生和护士可分别在http://cme.lww.com和www.nursingcenter.com进行测验。完整的CE/CME信息在本文的最后一页提供。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Geertien C. Boersema

RN, MCur (UP)

Lecturer, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

Hiske Smart*

RN, MA (Nur), PGDipWHTR (UK), IIWCC,

Manager, Wound Care & Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Unit, King Hamad University Hospital, Kingdom of Bahrain

Maria G. C. Giaquinto-Cilliers

MD, IIWCC

Affiliated Lecturer, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa; Head of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery & Burns Unit, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe Hospital, Kimberley, South Africa

Magda Mulder

PhD, RN, IIWCC

Head of School of Nursing, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Gregory R. Weir

MD, M.Med(Chir) (UP), CVS, IIWCC

Specialist Vascular Surgeon, Life Eugene Marais Hospital, Pretoria, South Africa

Febe A. Bruwer

RN, MSocSc(Nur), IIWCC

Clinical Nurse Specialist, Johannesburg, South Africa

Patricia J. Idensohn

MSc (Herts-UK), RN, IIWCC

Clinical Nurse Specialist, Ballito, South Africa; Lecturer, University of Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Johanna E. Sander

RN

Clinical Wound Care Nurse, 2nd Military Hospital, Cape Town,

South Africa

Anita Stavast

MSc (Herts–UK), RN, IIWCC, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Mariette Swart

RN, IIWCC

Clinical Wound Care Nurse, Strand, Cape Town, South Africa

Susan Thiart

RN, IIWCC, Clinical Wound Care Nurse, Pretoria, South Africa

Zhavandre Van der Merwe

RN, IIWCC

Clinical Wound Care Nurse, Pretoria, South Africa

References

- Demidova-Rice TN, Hamblin MR, Herman IM. Acute and impaired wound healing: pathophysiology and current methods for drug delivery, part 1: normal and chronic wounds: biology, causes, and approaches to care. Adv Skin Wound Care 2012;25(7):304‐14.

- Sibbald RG, Goodman L, Woo KY, et.al. Special considerations in wound bed preparation 2011: an update. Adv Skin Wound Care 2011;24:415-37.

- Korting HC, Schöllmann C, White RJ. Management of minor acute cutaneous wounds: importance of wound healing in a moist environment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:130-7.

- Cañedo-Dorantes L, Cañedo-Ayala M. Skin acute wound healing—a comprehensive review. Int J Inflam 2019;2019:3706315.

- European Wound Management Association. Position document: hard-to-heal wounds: a holistic approach. https://ewma.org/fileadmin/user_upload/EWMA.org/Position_documents_2002-2008/EWMA_08_Eng_final.pdf. October 2008. Last accessed October 8, 2020.

- Leaper DJ, Schultz G, Carville K, Fletcher J, Swanson T, Drake R. Extending the TIME concept: what have we learned in the past 10 years? Int Wound J 2014;9(Suppl 2):1-19.

- Sibbald RG, Elliot JA, Ayello EA, Somayaji R. Optimizing the moisture management tightrope with wound bed preparation 2015. Adv Skin Wound Care 2015;28(10):466-76.

- Jordan Z, Lockwood C, Munn Z, Aromataris E. The updated Joanna Briggs Institute Model of Evidence-Based Healthcare. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2019;17(1):58-71.

- Crowe M, Sheppard L, Campbell A. Comparison of the effects of using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool versus informal appraisal in assessing health research: a randomised trial. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2011;9(4):444-9.

- Margolis DJ, Bilker W, Santanna J, Baumgarten M. Venous leg ulcer: incidence and prevalence in the elderly. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46(3):381-6.

- Troxler M, Vowden K, Vowden P. Integrating adjunctive therapy into practice: the importance of recognizing ‘hard-to-heal’ wounds. World Wide Wounds. 2006. www.worldwidewounds.com/2006/december/Troxler/Integrating-Adjunctive-Therapy-Into-Practice.html. Last accessed October 8, 2020.

- Weir RG, Smart H, Van Marle J, Cronje FJ. Arterial disease ulcers, part 1: clinical diagnosis and investigation. Adv Skin Wound Care 2014;27(9):421-8.

- Jensen NK, Pals RAS. A dialogue-based approach to patient education. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2015;19(1):168-70.eS.

- Keliddar I, Mosadeghrad AM, Jafari-Sirizi M. Rationing in health systems: a critical review. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2017;31:47-54.

- Cohen M, Quintner J, Van Rysewyk S. Reconsidering the International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain. Pain Rep 2018;(2):e634.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Adderley UJ, Holt IGS. Topical agents and dressings for fungating wounds (reviews). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;5:1-26.

- Ousey K, Edwards K. Exploring resilience when living with a wounds—an integrative literature review. Healthcare (Basel) 2014;2(3):346-55.

- Neumann M, Cornu-Thénard A, Jünger M, et al. Evidence based (S3) guidelines for diagnostics and treatment of venous leg ulcers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016;30(11):1843-75.

- Weller CD, Team V, Ivory JD, Crawford K, Gethin G. ABPI reporting and compression recommendations in global clinical practice guidelines on venous leg ulcer management: a scoping review. Int Wound J 2019;16(2):406-19.

- Andriessen A, Apelqvist J, Mosti G, Partsch H, Gonska C, Abel M. Compression therapy for venous leg ulcers: risk factors for adverse events and complications, contraindications—a review of present guidelines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31(9):1562-8.

- Ratliff CR, Yates S, McNichol L, Gray M. Compression for primary prevention, treatment, and prevention of recurrence of venous leg ulcers. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):347-64.

- Tang JC, Marston WA, Kirsner RS. Wound Healing Society (WHS) venous ulcer treatment guidelines: what’s new in five years? Wound Repair Regen 2012;20:619-37.

- Weller CD, Evan S. Venous leg ulcer management in general practice: practice nurses and evidence-based guidelines. Aust Fam Physician 2012;(4)5:331-7.

- Miller C, Kapp S, Donohue L. Sustaining behaviour changes following a venous leg ulcer client education program. Healthcare 2014;2:324-37.

- Carter M. Economic evaluations of guideline-based or strategic interventions of the prevention or treatment of chronic wounds. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2014;1(12):373-89.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Optimal Care of Chronic, Nonhealing, Lower Extremity Wounds: A Review of Clinical Evidence and Guidelines. Ottawa, ON, Canada: CADTH; 2013.

- Harding K, Armstrong D, Chadwick P, et al. Position document: local management of diabetic foot ulcers. World Union of Wound Healing Societies. In: Florence Congress, Position Document. 2016:1-28.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Managing Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Guidelines. Ottawa, ON, Canada: CADTH; 2014.

- Taylor SM, Johnson BL, Samies NL, et al. Contemporary management of diabetic neuropathic foot ulceration: a study of 917 consecutively treated limbs. J Am Coll Surg 2011;212(4):532-45.

- Isei T, Abe M, Nakanishi T, et al. The wound/burn guidelines—3: guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment for diabetic ulcer/gangrene. J Dermatol 2016;43(6):591-619.

- Lavery LA, Davis KE, Berriman SJ, et al. WHS guidelines update: diabetic foot ulcer treatment guidelines. Wound Repair Regen 2016; 24:112-26.

- Huang ET, Mansouri J, Murad MH, et al. A clinical practice guideline for the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Undersea Hyperb Med 2015;42(3):205-47.

- Crawford PE, Fields-Varnado M. Guideline for the management of wounds in patients with lower-extremity neuropathic disease. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(1):34-45.

- Guihan M, Bombardier CH. Potentially modifiable risk factors among veterans with spinal cord injury hospitalized for severe pressure ulcers: a descriptive study. J Spinal Cord Med 2012;35(4):240-50.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Dressing Material for the Treatment of Pressure Ulcers Inpatients in Long-term Care Facilities: A Review of the Comparative Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines. Ottawa, ON, Canada: CADTH; 2013.

- Gelis A, Pariel S, Colin D, et al. What is the role of TPE in management of patients at risk or with pressure ulcers? Toward development of French guidelines for clinical practice. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2012;55:517-29.

- Fujiwara H, Isogai Z, Irisawa R, et al. Wound pressure ulcer and burn guidelines—2: guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pressure ulcers, second edition. J Dermatol 2018;1-50.

- Addison NO, Pfau S, Koka E et al. Assessing and managing wounds of Buruli ulcer patients at the primary and secondary health care levels in Ghana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017;11(2):e0005331.

- Alavi A, Farzanfar D, Rogalska T, et al. Quality of life and sexual health in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Womens Dermatol 2018;4:74-9.

- Pope E, Lara-Corrales I, Mellerio J, et al. A consensus approach to wound care in epidermolysis bullosa. Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:904-17.

- Shanmugam VK, Angra D, Rahimi H, McNish S. Vasculitic and autoimmune wounds. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2017;5:280-92.

- Akhmetova A, Saliev T, Allan IU, et al. A comprehensive review of topical odor-controlling treatment options for chronic wounds. J Wound Continence Nurs 2016.46(6):598-609.

- Schultz G, Bjarnsholt T, James GA, et al. Consensus guidelines for the identification and treatment of biofilms in chronic nonhealing wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2017;25:744-57.

- Sherman RA. Mechanisms of maggot-induced wound healing: what do we know and where do we go from here. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2014:1-13.

- Olsson M, Järbrink K, Divakar U, et al. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: a systematic review. Wound Repair Regen 2019;27(1):114-25.

- Woo KY, Sibbald RG. Local wound care for malignant and palliative wounds. Adv Skin Wound Care 2010;23(9):417-28.

- Driver VR, Gould LJ, Dotson P, et al. Evidence supporting wound care endpoints relevant to clinical practice and patients’ lives. Part 2. Literature survey. Wound Repair Regen 2019;27(1):80-9.

- Swanson T, Angel D, Sussman G, et al. Wound infection in Clinical Practice. International Wound Infection Institute (IWII). Wounds International. 2016. www.woundinfection-institute.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/IWII-Wound-infection-in-clinical-practice.pdf. Last accessed October 8, 2020.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. 3rd ed. EPUAP-NPIAP-PPPIA; 2019.

- Lowe J, Sibbald RG, Taha NY, et al. The Guyana diabetes and foot care project: improved diabetic foot evaluation reduces amputation rates by two-thirds in a lower middle-income country. Int J Endocrinol 2015;2015:920124.

- Porter ME. How competitive forces shape strategy. Harvard Bus Rev 1979;57(2):137-45.

- O’Hara NN, Nophale LE, Lyndsay M, et al. Tuberculosis testing for healthcare workers in South Africa: a health service analysis using Porter’s Five Forces Framework. Int J Healthcare Manag 2017;10(1):49-56.