Volume 41 Number 3

A litmus test for innovation: a real-world evaluation of a pH-buffering ostomy barrier

Scarlett Summa, George Skountrianos, Jimena V Goldstine, Louise Hannan and David Fischer

Keywords peristomal skin complications, acid mantle, pH-buffering, peristomal skin pain, ostomy barrier

For referencing Summa S et al. A litmus test for innovation: a real-world evaluation of a pH-buffering ostomy barrier. WCET® Journal 2021;41(3):14-21

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.14-21

Submitted 30 March 2021

Accepted Accepted 11 June 2021

Abstract

Background Preserving the skin’s acid mantle can help reduce the formation of peristomal skin complications (PSCs). Ostomy products should strive to address this ongoing challenge.

Objective We assessed clinical outcomes and ostomy supply use associated with the use of a barrier designed with pH-buffering technology.

Methods This real-world observational user evaluation recruited 440 clinicians from 11 countries to complete an evaluation for 975 ostomates before and after use of a pH-buffering barrier. Evaluations included a validated discolouration, erosion and tissue overgrowth (DET) peristomal skin assessment tool, a peristomal skin pain scale, and scales for satisfaction and likelihood of recommending the product. Ostomy resource utilisation was also recorded.

Results Mean (SD) DET (n=797) and peristomal skin pain scores (n=392) decreased significantly by 1.9 (3.0, p<0.001) and 1.8 (2.6, p<0.001) points, respectively, after using the pH-buffering barrier. The proportion of patients not requiring ostomy accessories increased by 40.2%; half of patients (n=52) on topical peristomal skin medications reduced their usage. Wear times increased for 38.0% of patients (n=900). Most respondents were satisfied or highly satisfied with the barrier (88.2%, n=952) and likely or highly likely to recommend it (86.4%, n=960).

Conclusions Peristomal skin health and pain levels significantly improved, barrier wear time increased, and topical peristomal skin medication and accessory use decreased after utilising the pH-buffering barrier. These findings on healthcare resource utilisation suggest the pH-buffering barrier provides benefits beyond addressing the clinical burden of an ostomy.

Introduction

Maintaining skin health and avoiding skin complications remain challenges for individuals living with an abdominal stoma1,2. Healthy skin has an acidic stratum corneum; this acid mantle is essential to sustain natural microflora and to reduce the risk of bacterial and yeast infections3. Intrinsic factors, such as age, genetic predisposition, sebum and skin moisture, and external factors, such as skin irritants and dressings, affect the pH level of the acid mantle4. Another variable affecting the acid mantle is stomal leakage, a common concern among ostomates and wound, ostomy and continence (WOC) nurses5–7. If not contained appropriately, enzymes found in stoma effluent can seep onto the skin to create an alkaline environment, disrupt the acid mantle, and increase the risk of peristomal skin complications (PSCs)8–10. For example, urease from urine increases skin pH levels and can lead to incontinence-associated dermatitis8, and seepage of faecal enzymes with enhanced activity at the alkaline pH level is associated with skin irritation9.

Other origins of PSCs include skin stripping from repeated barrier changes and irritation from applications and dressings1,11. Irritant contact dermatitis, a common PSC in ostomates, can develop from leakage or adhesive-related damage1. Mechanical damage from repeated dressing application and removal can also contribute to medical adhesive-related skin injuries11.

Recently reported PSC incidence following an ostomy continues to be as high as 73%12–14. In addition, individuals with a stoma have reported pain, discomfort, decreased self-confidence, and a negative change in body image15. These factors can weigh greatly on a patient’s social functioning, wellbeing, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)15,16.

In addition to the humanistic and clinical burdens that PSCs pose, the economic burden cannot be ignored. Higher readmission rates have been associated with patients with PSCs than patients without PSCs, leading to higher healthcare costs2. Treating PSCs also requires specialised care and additional healthcare resources such as topical medicines17,18.

Investment in ostomy barrier innovation, supported by robust evidence, is therefore necessary for clinicians to make informed decisions regarding their patients’ ostomy care to maximise patient HRQoL through better clinical and economic outcomes. While there have been improvements in ostomy barriers to better fit the individual’s needs, PSC rates continue to be very high. An ideal barrier would reduce PSCs, simplify stoma management, and provide an economic benefit by maintaining peristomal skin health and reducing the need for accessories and medication. This user evaluation analysed patients’ peristomal skin health and healthcare resource utilisation before and after using a pH-buffering barrier. To the authors’ knowledge, this pH-buffering barrier is the only barrier available on the market that has sustained pH-buffering capacity to preserve the peristomal skin’s acid mantle. Various survey measures were utilised to determine the outcomes of using the pH-buffering barrier, including the effect on peristomal skin health, patient wellbeing, and clinician satisfaction levels.

Methods

In this multinational, real-world, observational user evaluation, written feedback was gathered from clinician experiences of prescribing the pH-buffering barrier to individuals with a stoma. Between March 2018 and February 2020, responses were collected from 440 clinicians, representing 975 patients, using a paper-based two-part evaluation form. The clinicians were from hospitals and clinical centres based in 11 countries in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. The evaluation forms were translated into each local language.

Patients were selected for inclusion based on the clinician’s professional recommendation and on the patient’s willingness to try the product. No incentives were provided for participating clinicians or patients. Clinicians were encouraged to complete part 1 (pre-evaluation) of the questionnaire for each patient before and part 2 (post-evaluation) after incorporating the pH-buffering barrier into the patient’s ostomy care plan. After collection, responses were translated into English upon digitisation ex post facto.

The evaluation distribution, response collection and data analyses were not subjected to ethics review by an independent review board. Release forms were used to acquire clinician and patient permission to publish, reproduce and distribute any data or findings related to the evaluation. To ensure patient privacy, no identifying information (e.g., patient name, hospital identification number) or images were collected. Clinician and patient participation was entirely voluntary, and the patient could have discontinued the evaluation at any time without penalty.

Clinicians measured peristomal skin damage using the validated DET scale (Ostomy Skin Tool) evaluating discolouration, erosion and tissue overgrowth19. The combined DET score ranges from 0 for normal intact peristomal skin to 15 for severely damaged peristomal skin. Peristomal skin pain was rated on a numerical rating scale (NRS-11) of 0 (“no pain”) to 10 (“worst pain imaginable”)20.

To estimate ostomy pouch utilisation, pre-evaluation and post-evaluation wear times were converted to daily pouch utilisation. Daily usage was calculated by dividing one pH-buffering barrier by the number of days that the pouch was worn (e.g., wear time of 2 days denoted use of half a barrier per day). Patients who changed their pouches more than once daily were assumed to use two pouches per day. Patients who changed their pouches every 7 days or longer were assumed to have a wear time of 10 days (i.e., use of 1/10 of a barrier per day). As a final step for ease of interpretation, daily usage was converted to monthly usage (assuming 30 days per month).

Analysis of forms for the 975 patients was performed with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA). Statistics were calculated based on the total non-missing response count. Statistical tests were performed when the sample size was at least 30 patients.

Results

Patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics

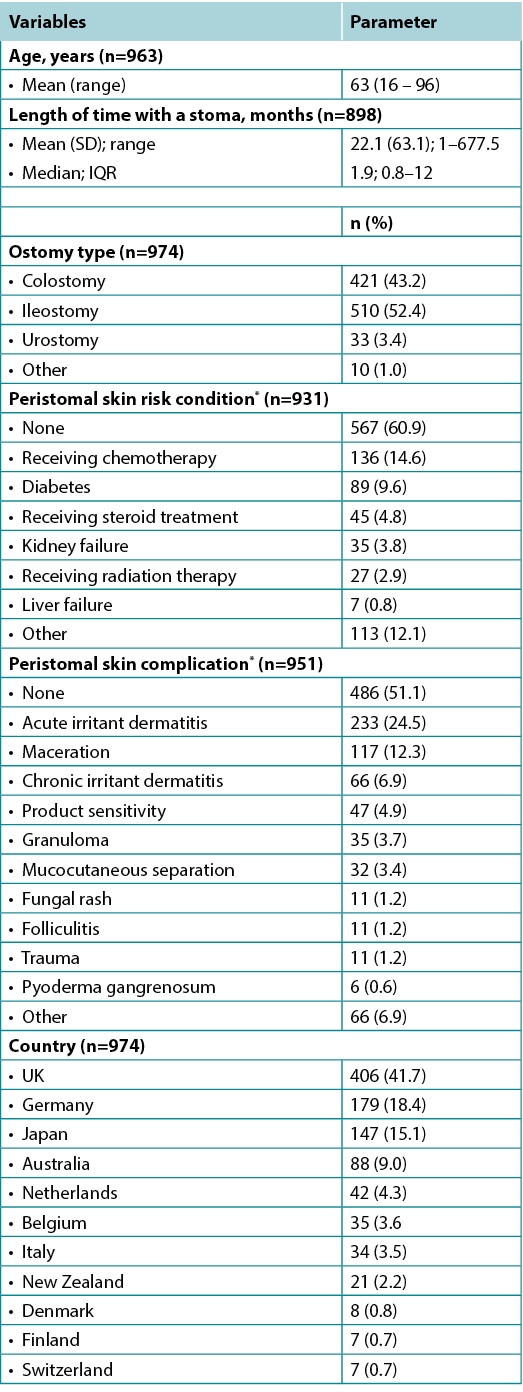

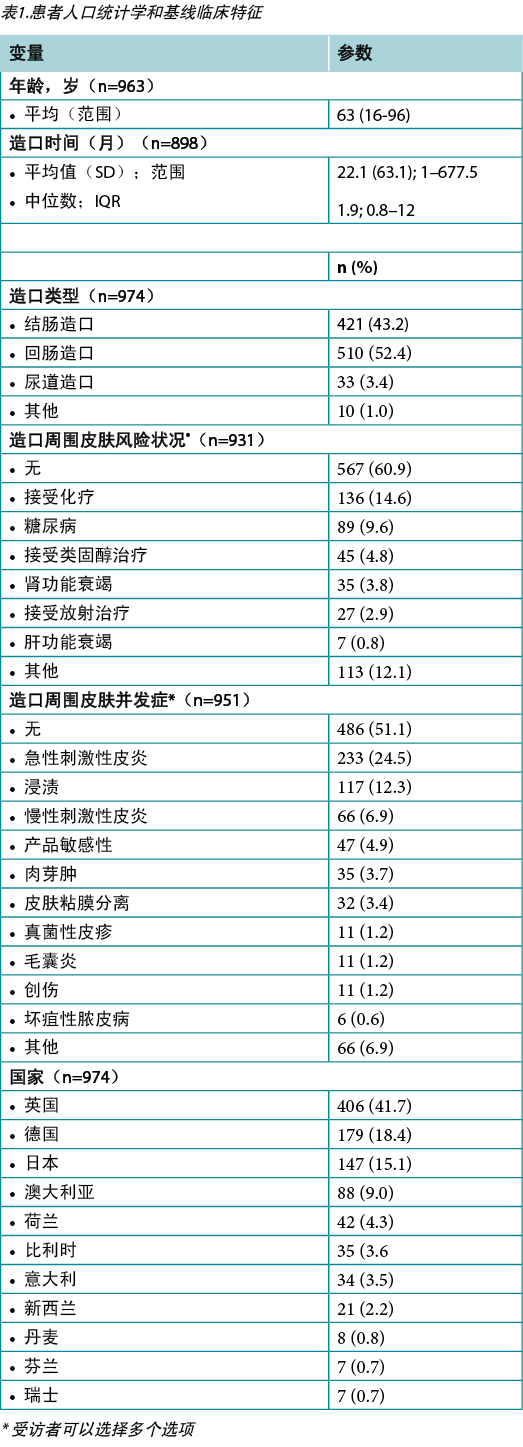

The mean patient age was 63 years (range 16–96 years, n=963). When responses were broken down by country, most (n=406) were received from the United Kingdom. The mean time between completing the pre-evaluations and post-evaluations was 18 days (range 1–354 days). Half of all evaluations were completed within 12 days, and 90% were completed within 42 days. At baseline, 231 (23.7%) of 973 patients were already using the pH-buffering barrier.

Stomal characteristics collected at baseline are described in Table 1. A total of 95% of patients underwent either a colostomy or ileostomy (n=974). The mean length of time with a stoma (n=898) was 22.1 months, with a median of 1.9 months. Three-quarters of respondents were living with their stoma for less than 12 months. Fewer than half of the pooled population indicated a comorbidity or a PSC. More than half, or 567 (60.9%) of 931 patients, had no comorbidities that would put their peristomal skin at risk, and 486 (51.1%) of 951 patients reported no PSCs at baseline. For those who reported a PSC at baseline, the most common was acute irritant dermatitis (24.5%, n=233) followed by maceration (12.3%, n=117) and chronic irritant dermatitis (6.9%, n=66).

Table 1. Patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics

* Respondents were allowed to select more than one option

DET and peristomal skin pain score results

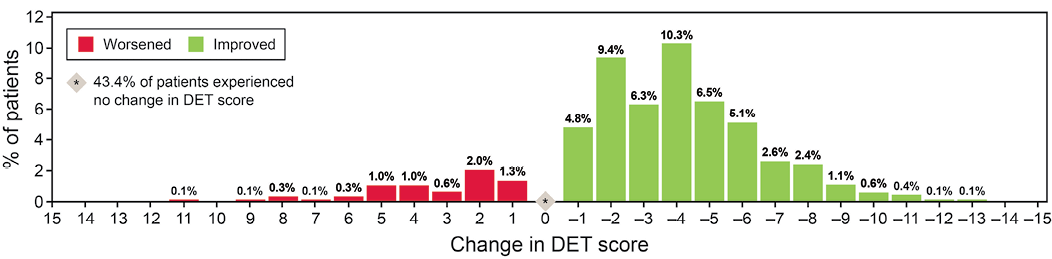

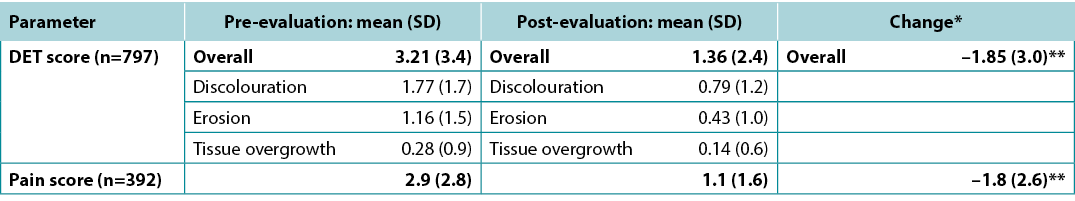

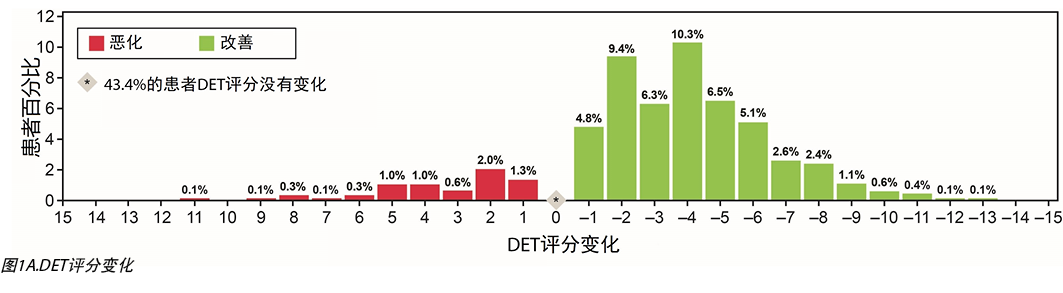

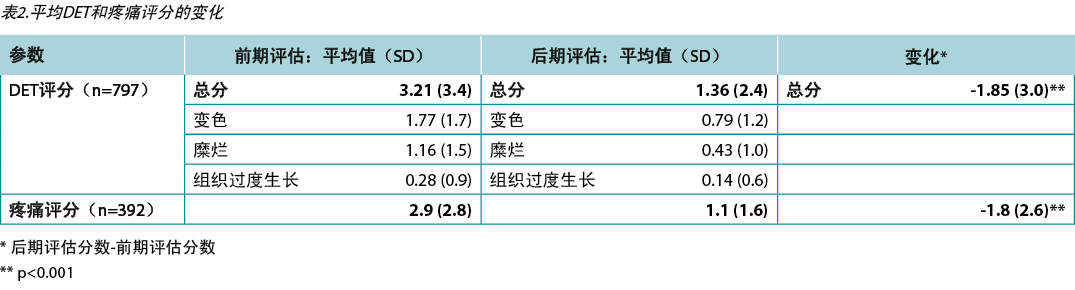

A total of 797 patients met inclusion criteria and had valid data for DET scores. Skin improvement, as indicated by a decrease in DET scores, showed a significant improvement after using the pH-buffering barrier (Figure 1A). The mean pre-evaluation DET score (SD) was 3.21 (3.39) points, and the mean post-evaluation DET score (SD) was 1.36 (2.40) points. For the entire user evaluation population, the mean change in DET (SD) was significant, dropping by 1.85 (3.01) points (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Figure 1A. Change in DET score

Table 2. Change in mean DET and pain scores

* Post-evaluation score – pre-evaluation score

** p<0.001

The mean DET score for patients who had been using the barrier prior to commencing the evaluation decreased from 0.79 to 0.52 points; this change was not statistically significant. In contrast, patients who were introduced to the barrier at pre-evaluation had an average reduction in DET score of 2.35 points (from 3.98 to 1.63, p<0.001).

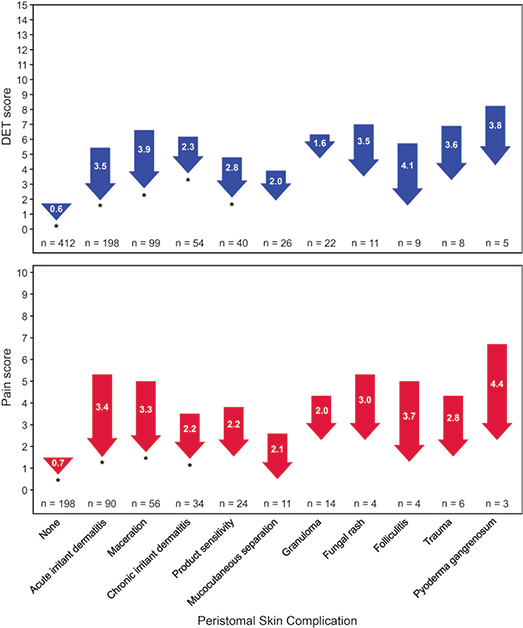

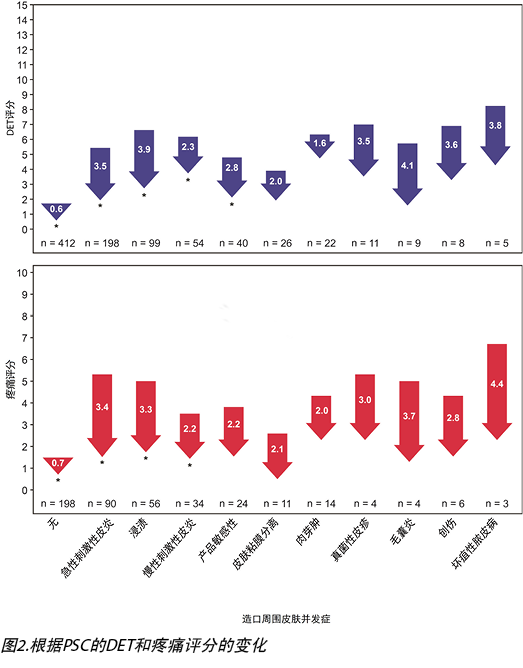

After observing the peristomal skin health of the overall population, we stratified the data by PSC types. Using the 635 PSCs documented from 465 patients, changes in DET scores were subcategorised by skin condition (Figure 2). DET scores decreased across all skin conditions. For those conditions tested for statistical significance (i.e., those with n≥30), the greatest significant decrease in DET scores was observed in the subpopulation with maceration (3.9) followed by acute irritant dermatitis (3.5), product sensitivity (2.8) and chronic irritant dermatitis (2.3), while the smallest decrease (0.6 points) was found in patients without a PSC at baseline (p<0.001).

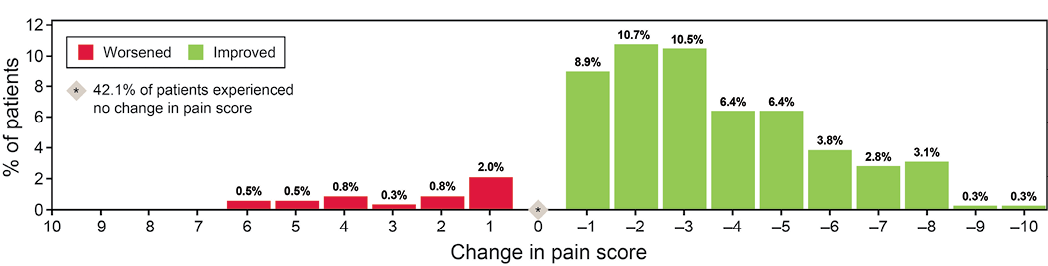

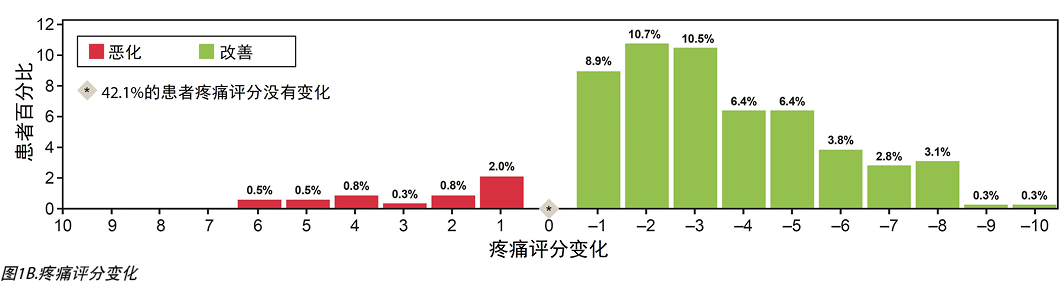

Similar to DET scores, peristomal skin pain scores showed a statistically significant reduction across the sampled cohort. Pain scores decreased for 208 (53.1%) of 392 patients, while 165 noted no change and 19 had increased pain scores (Figure 1B). Across 392 patients reporting scores, mean (SD) pain scores reduced by 1.8 (2.6) points (p<0.001) (Table 2). When stratified by PSC type, peristomal pain scores decreased for all skin conditions (Figure 2). For those conditions tested for statistical significance (n≥30, p<0.001), scores significantly decreased for every category tested – acute irritant dermatitis (3.4), chronic irritant dermatitis (2.2) and maceration (3.3). Furthermore, a statistically significant reduction in pain score was reported for patients who did not have a PSC at baseline (0.7, p<0.001).

Figure 1B. Change in pain score

Figure 2. Change in DET and pain scores according to PSC

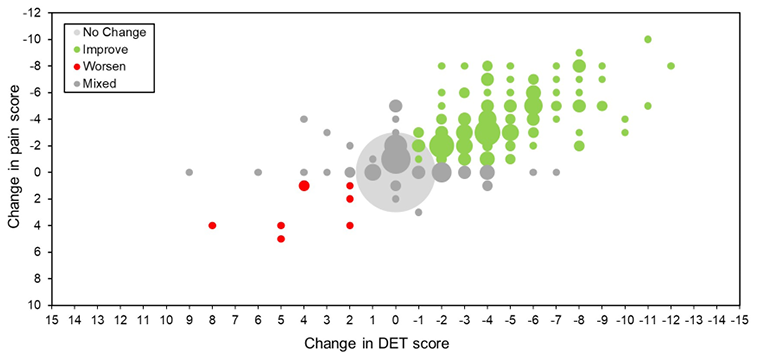

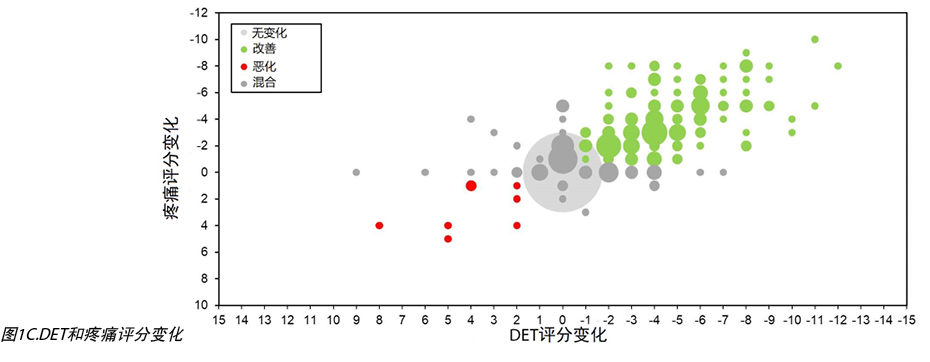

Noting this trend, we found a statistically significant correlation between DET and pain scores both pre-evaluation and post-evaluation. The correlation coefficient (rho) between DET and pain scores was 0.77 (pre-evaluation) and 0.53 (post-evaluation) (p<0.001 for both). A correlation was also observed between the change in DET and pain scores (0.73) (Figure 1C). Taken together, these findings suggest a close alignment of the two aspects regardless of the pH-buffering barrier use. Although these correlations may be intuitive to clinicians, this is the first user evaluation to definitively report this trend.

Figure 1C. Change in DET and pain scores

Healthcare resource utilisation

From our resource utilisation findings, the barrier has the potential to lower ostomy care costs by providing a longer wear time as well as lower associated ostomy accessories and topical peristomal medication use. Wear time was extended for 342 (38.0%) of 900 patients while using the pH-buffering barrier. There was a 55% decrease in the number of patients who changed their pouch more than once per day. Furthermore, there was a 34% increase in the number of patients who achieved wear times of 2 days or longer. These improvements in wear time resulted in fewer pouches per month, from 31.2 (20.0) pouches pre-evaluation to 23.7 (16.3) pouches post-evaluation.

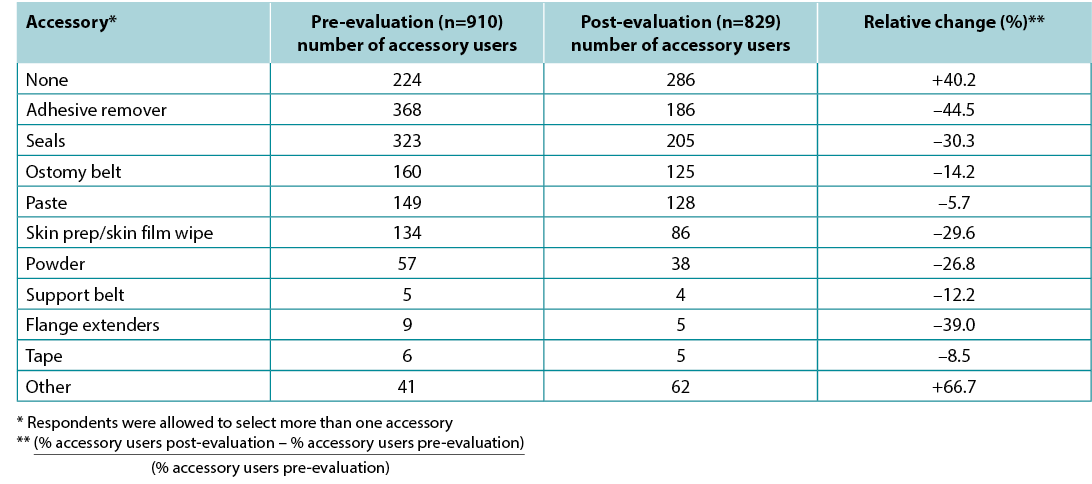

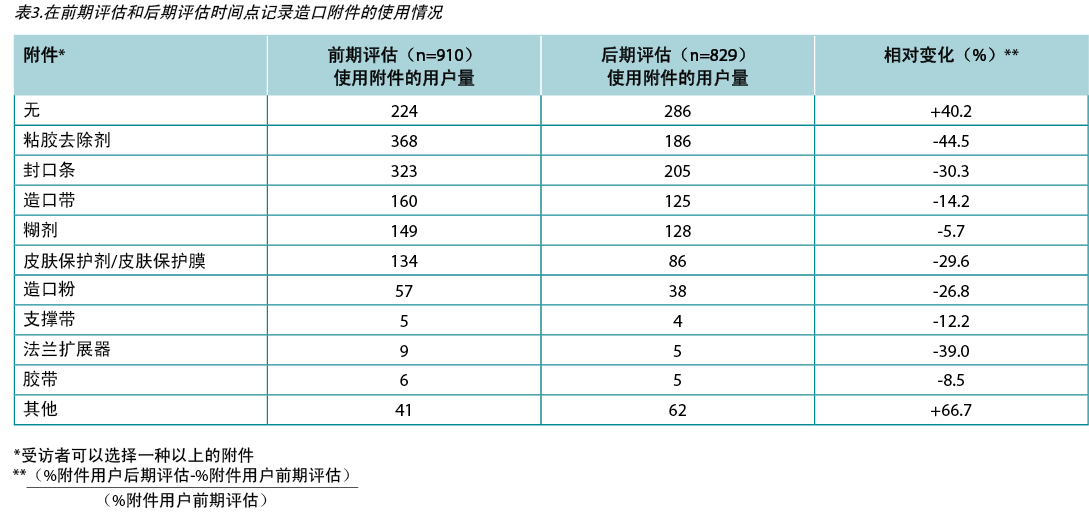

Our evaluation also collected information on the ostomy-related accessories used by each patient. The most common accessory used pre-evaluation was adhesive remover, followed by seals, ostomy belts and paste. Percentages of patient usage of pastes, seals, adhesive remover, skin preps, powder, ostomy belts, support belts, flange extenders and tape all decreased in the post-evaluations (Table 3). The percentage of patients not requiring any accessories increased from 24.6% to 34.5% (p<0.001), a relative change of +40.2%. A total of 52 patients used topical peristomal skin medications during the length of the evaluation; 26 (50%) patients noted a decrease in medication use in the post-evaluation, and seven reported increased use.

Table 3. Ostomy accessory usage recorded at pre-evaluation and post-evaluation time points

Clinician satisfaction and experience with the pH-buffering barrier

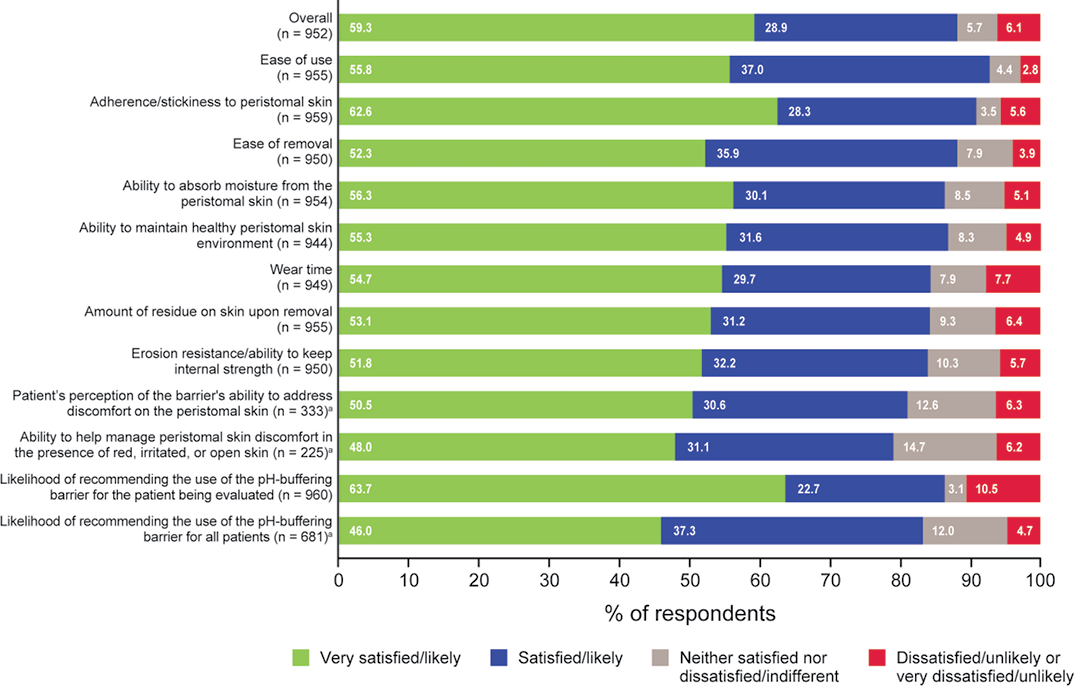

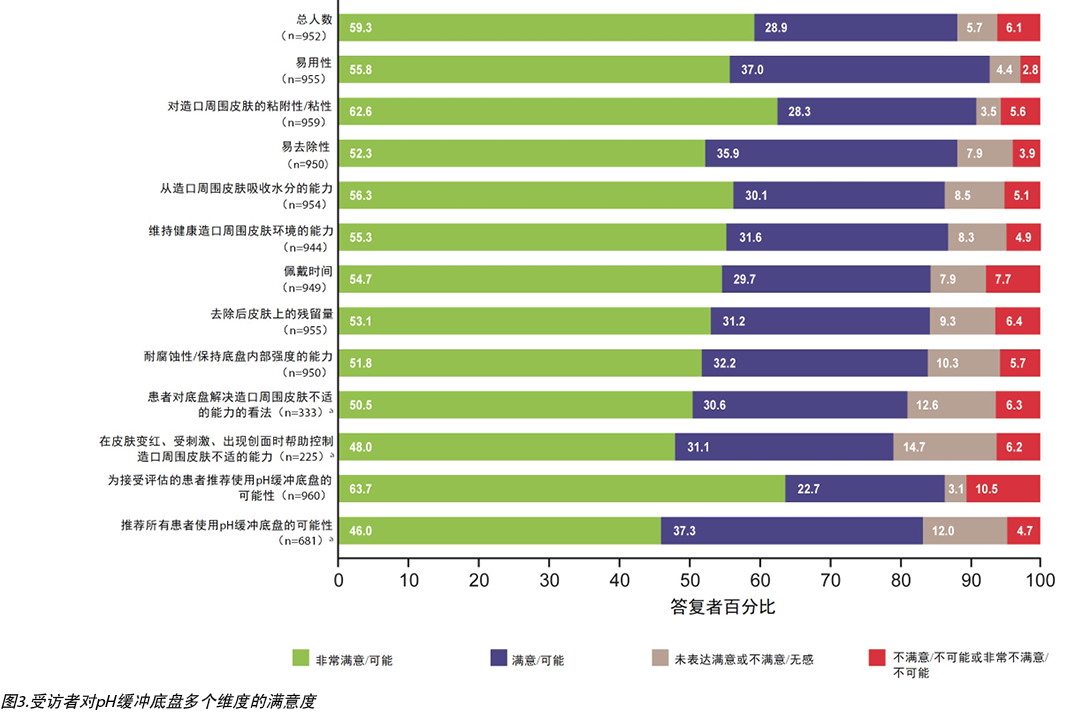

We next sought to record clinicians’ satisfaction with the pH-buffering barrier across several dimensions, with the large majority reporting “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with all attributes examined (Figure 3). The four attributes acknowledged in the pH-buffering barrier’s design – ease of use, adherence to peristomal skin, ease of removal, and the ability to absorb moisture – all received positive satisfaction from at least 86% of clinicians. The resulting high levels of satisfaction suggest that clinicians perceive such barriers and technology to be of high value to their practice and patients.

Figure 3. Respondents’ satisfaction with the pH-buffering barrier across several dimensions

Satisfaction responses positively correlated with the likelihood of clinicians recommending the pH-buffering barrier (Figure 3). A total of 829 (86%) of 960 clinicians were “very likely” or “likely” to recommend the product as part of the ostomy care plan for the patient being evaluated. When asked the same question for all patients, 567 (83%) of 681 were “very likely” or “likely” to recommend the product. Unsurprisingly, the results from satisfaction responses and the likelihood to recommend the pH-buffering barrier align with positive skin outcomes.

Discussion

The pH-buffering barrier was developed to maintain the skin’s acid mantle under all fluid-exposure conditions. In vitro assessments demonstrated that the pH-buffering barrier remains in the healthy pH range for skin after exposure to alkaline saline, with a pH similar to effluent that may leak under the barrier21. These qualities may be desired by stoma care nurses who wish to provide their patients with the best possible experience from the outset of stomal surgery, when high stomal output and aggressive stools are especially common22. Our findings suggest that skin health improves with use of the pH-buffering barrier, as indicated by the statistically significant decreases in DET and peristomal skin pain scores. Approximately 24% of participants were using the pH-buffering barrier before pre-evaluation. As expected, results indicate no statistically significant changes in DET score prior to and after the evaluation. In contrast, participants who switched to the pH-buffering barrier at pre-evaluation experienced a statistically significant decrease in DET score after using the pH-buffering barrier. These two findings suggest minimal assessment bias, as we would expect that a patient already on the pH-buffering barrier (before pre-evaluation) would not have any substantive changes in DET score.

Previous research has assessed pain as an adverse consequence of living with a stoma23. However, to the authors’ knowledge, the present analysis is the first published evaluation of the association between peristomal skin pain and DET scores. Pain has been a resounding theme reported by clinicians, and the effects on HRQoL can be debilitating. Findings from a study by Kini et al. show that the average patient with chronic pain had a symptom utility score of 0.7724. In other words, patients were willing to trade 23% of their life expectancy to avoid pain. Our findings suggest that barrier use correlates with significantly decreased patient-reported peristomal skin pain. We believe that this is strong evidence for stoma care nurses to consider when identifying patient pain and offering informed solutions. Moreover, we found a positive correlation between change in skin damage (as measured quantitatively via DET scores) and pain, which suggests a relationship not previously explored.

Pouching failure and pain have negative psychological effects on patients. Evidence has shown that HRQoL scores are higher for patients with healthy peristomal skin than for those with irritated peristomal skin16,25. In addition, leakage and a lack of pouch security contribute to patient activity withdrawal and may elicit various social and physical coping mechanisms.26 In our assessment, improvement in DET and peristomal pain scores occurred in all PSC categories, and the changes were statistically significant for acute irritant dermatitis, chronic irritant dermatitis and maceration. These findings suggest that the pH-buffering barrier mitigated the effects of leakage at the barrier to reduce the severity and incidence of PSCs and improve pain scores. Therefore, the pH-buffering barrier has the potential to improve HRQoL via reduction or prevention of PSCs.

With the pH-buffering barrier, patients experienced longer wear time and lower usage of ostomy accessories and topical skin medications. Such favourable outcomes may lead to more simplified ostomy care plans devoid of multiple prescriptions and time-consuming steps. The reduced need for costly ostomy-related resources also suggests potential economic benefits of the pH-buffering barrier. Additional analyses would be required to affirm the translation of our findings into potential cost savings.

In parallel with clinical outcomes, we observed high rates of satisfaction and likelihood of recommendation of the pH-buffering barrier among clinicians, as well as satisfaction with ease of barrier use and removal, adherence to peristomal skin and wear time. Although patient satisfaction was not surveyed, clinician-reported satisfaction was found in the patient’s perception of the ability of the pH-buffering barrier to address discomfort.

Taken together, the evaluations provide real-world evidence of the impact of pH-buffering technology on peristomal skin health outcomes. We employed a within-subject design to minimise selection bias and ensure adequate statistical power to estimate effects of the pH-buffering barrier on outcomes. The evaluation did not dictate any changes to each clinician’s standard of care, thus reflecting real-world practices. In addition, specific survey instruments were used which are validated and reliable assessment tools that permit comparison of results across different studies.

Limitations

Due to the observational nature of this research, only an association (not a causation) can be established from the findings. The time between completing the pre-evaluation and post-evaluation varied from patient to patient, which may have caused bias of an unknown direction in the responses. Regarding DET scores, the sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the amount of elapsed time did not affect the statistical significance in DET score change. For this user evaluation, no formal training on the use of DET or pain scales was provided to participating clinicians; hence, the assessments themselves may vary by clinician experience. It was also necessary to revise the evaluation form to ensure its compliance with European Union General Data Protection Regulation. Overall, three versions were distributed. Therefore, certain survey responses were not available for every patient.

Although we believe that our multinational clinician and patient population is a strength, we did not account for differences in standard of care in each country or typical patient or clinician practice patterns in ostomy care. The overall time an individual was living with their stoma was not factored into data analyses. Moreover, our research was not a comparative evaluation, so we were unable to separate the effect of the pH-buffering barrier from other factors.

Conclusions

Skin barriers should be secure, reliable, financially feasible, and keep peristomal skin healthy. Our assessments, based on information-rich evaluations, demonstrate real-world outcomes of a product addressing a fundamental aspect of maintaining the peristomal skin. This research is aimed to help patients and their healthcare providers make informed decisions in caring for their stoma and peristomal skin. It utilised both clinician- and patient-reported outcomes to generate comprehensive data with feedback on varied survey instruments. With the pH-buffering barrier, patients experienced positive outcomes as evidenced by reduced DET and peristomal pain scores while presenting a potential financial benefit through increased wear time and decreased ostomy accessory and topical peristomal skin medication use.

One unique finding we noted was that peristomal skin pain, while often unaccounted for, is a prominent issue for patients with a stoma. Use of the pH-buffering barrier correlated with decreased pain. Furthermore, skin health improved across multiple skin ailments in our user evaluation population. These results may be informative for stoma care nurses treating patients with specific PSCs or seeking to prevent PSCs. Choosing an ostomy barrier addressing skin pH may contribute to skin health and improve patient wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Gary Inglese, RN, MBA, of Hollister Incorporated, Libertyville, IL, for his invaluable input regarding the manuscript. Medical writing services were provided by Sabiha Runa, PhD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Incorporated, Newtown, PA, and funded by Hollister Incorporated, Libertyville, IL.

Declaration of interest

This research was sponsored by Hollister Incorporated, Libertyville, IL, USA. David Fischer, Jimena Goldstine and George Skountrianos are employees of Hollister Incorporated. Louise Hannan was an employee of Dansac A/S, Fredensborg, Denmark at the time of the research. Scarlett Summa receives personal fees and non-financial support from Lectures, Erlangen, Germany and ICEF consulting, Bonn, Germany. Lastly, 44% (81 of 184) of the UK clinicians who participated in this evaluation were employed or sponsored by Dansac A/S; no incentives were provided to any participating clinicians.

创新的试金石:对pH缓冲造口底盘的真实世界评估

Scarlett Summa, George Skountrianos, Jimena V Goldstine, Louise Hannan and David Fischer

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.14-21

摘要

背景 保护皮肤的酸性保护膜有助于减少造口周围皮肤并发症(PSC)的形成。造口产品应努力应对这一持续的挑战。

目的 我们评估了与使用pH缓冲技术设计的底盘相关的临床结果和造口用品使用情况。

方法 这项真实世界观察性用户评估招募了来自11个国家的440名临床医生,以在使用pH缓冲底盘之前和之后完成对975名造口者的评估。评估包括经验证的变色、糜烂和组织过度生长(DET)造口周围皮肤评估工具、造口周围皮肤疼痛量表,以及推荐产品的满意度和可能性量表。同时,记录了造口资源使用率。

结果 使用pH缓冲后,平均(SD)DET(n=797)和口周皮肤疼痛评分(n=392)分别显著降低1.9(3.0,p<0.001)和1.8(2.6,p<0.001)。不需要造口辅助设备的患者比例增加了40.2%;半数(n=52)局部使用造口周围皮肤药物的患者减少了药物使用。38.0%(n=900)的患者底盘使用的时间增加。大多数受访者对该底盘感到满意或非常满意(88.2%,n=952),并且很可能推荐该底盘(86.4%,n=960)。

结论 使用pH缓冲底盘后,造口周围皮肤健康和疼痛水平显著改善,底盘使用时间延长,局部造口周围皮肤用药和辅助使用减少。这些关于医疗资源利用的研究结果表明,pH缓冲底盘好处不仅在于解决造口术的临床负担。

引言

保持皮肤健康和避免皮肤并发症仍然是腹部造口患者面临的挑战1,2。健康的皮肤角质层呈酸性;这种酸性保护膜对于维持天然微生物群落和降低细菌与酵母菌感染风险至关重要3。内在因素,如年龄、遗传倾向性、皮脂和皮肤水分,以及外部因素,如皮肤刺激物和敷料,都会影响酸性保护膜的pH值4。另一个影响酸性保护膜的变量是造口渗漏,这是造口和伤口、造口和失禁(WOC)护士的共同关注点5-7。如果存储不当,造口流出物中的酶会渗入皮肤,形成碱性环境,破坏酸性保护膜,并增加造口周围皮肤并发症(PSC)的风险8-10。例如,尿液中的脲酶会增加皮肤的pH值,并可能导致失禁相关性皮炎8,而在碱性pH值下活性增强的粪便酶的渗出与皮肤刺激有关9。

PSC的其他起源包括重复更换底盘导致的皮肤撕裂以及造口用品和敷料造成的刺激1,11。刺激性接触性皮炎是造口中常见的PSC,可由渗漏或与粘合剂相关的损伤引起1。重复敷贴和移除敷料造成的机械损伤也可能导致与医用粘合剂相关的皮肤损伤11。

最近报告的造口术后PSC发生率仍然高达73%12-14。此外,造口人群报告了疼痛、不适、自信心下降以及身体形象的负面变化15。这些因素会对患者的社会功能、幸福感和健康相关生命质量(HRQoL)15,16产生很大影响。

除了PSC带来的情感和临床负担外,经济负担也不容忽视。相比没有PSC的患者,有PSC的患者的再入院率更高,从而导致更高的医疗保健成本2。治疗PSC还需要专门的护理和额外的医疗资源,例如外用药物17,18。

因此,在强有力的证据支持下,对于临床医生就患者的造口护理做出明智决定来说,投资造口底盘创新十分必要,可以提高临床护理效果,减轻经济负担,最大化患者HRQoL。虽然造口底盘已为更好地满足个人需求而有所改进,但PSC率仍居高不下。理想的底盘将减少PSC,简化造口管理,并通过保持造口周围皮肤健康和减少对附件和药物的需求来减轻经济负担。此用户评估分析了患者在使用pH缓冲底盘前后的造口周围皮肤健康和医疗资源使用情况。据作者所知,这种pH缓冲底盘是市场上唯一具有持续pH缓冲能力的底盘,可以保护造口周围皮肤的酸性保护膜。使用了多种调查措施来确定使用pH缓冲底盘的结果,包括对造口周围皮肤健康和患者健康的影响以及临床医生满意度。

方法

在本次多国、真实世界、观察性的用户评估中,书面反馈是从临床医生为有造口的个体开出pH缓冲底盘处方的经验中收集的。2018年3月至2020年2月期间,使用包含两部分的纸质评估表,从代表975例患者的440例临床医生处收集了答复结果。临床医生来自欧洲和亚太地区11个国家的医院和临床中心。不同语言地区的评估表已翻译为当地语言。

根据临床医生的专业推荐和患者尝试该产品的意愿,选择患者纳入研究。没有为参与的临床医生或患者提供奖励。鼓励临床医生在将pH缓冲底盘纳入患者造口护理计划之前为每位患者完成问卷的第1部分(前期评估),在纳入后完成第2部分(后期评估)。收集答复后,将其经数字化处理后翻译为英文。

评估发布、答复结果收集和数据分析无需经过独立审查委员会的道德审查。使用发布表来获得临床医生和患者对发布、复制和分发与评估相关的任何数据或结果的许可。为确保患者隐私,未收集任何识别信息(例如,患者姓名、医院识别号)或图片。临床医生和患者完全自愿参与,患者可以随时停止评估而不受处罚。

临床医生使用经过验证的DET量表(造口皮肤工具)测量造口周围皮肤损伤,评估变色、糜烂和组织过度生长19。综合DET评分范围为0(正常完整的造口周围皮肤)到15(严重受损的造口周围皮肤)。造口周围皮肤疼痛的评分采用数字评分量表(NRS-11),从0(“无疼痛”)至10(“可想象的最严重疼痛”)20。

为估计造口袋的利用率,前期评估和后期评估的使用时间转换为造口袋的每日利用率。每日使用量的计算方法是将一个pH缓冲底盘除以使用造口袋的天数(例如,2天的佩戴时间表示每天使用半个底盘)。假设每天更换不止一次造口袋的患者每天使用两个造口袋。假设患者每7天或更长时间更换一次造口袋,佩戴时间为10天(即每天使用1/10的底盘)。为便于解释,最后一步是将每日使用量转换为每月使用量(假设每月30天)。

使用SAS v9.4(SAS Institute,Cary,NC,USA)和Microsoft Excel(Redmond,WA,USA)对975例患者的表格进行分析。统计数据基于总体非缺失答复计数进行计算。当样本量至少为30例患者时,进行统计检验。

结果

患者人口统计学和基线临床特征

患者平均年龄为63岁(范围:16岁–96岁,n=963)。如果将患者按国家分类,大多数(n=406)来自英国。完成前期评估和后期评估之间的平均时间为18天(范围1-354天)。一半的评估在12天内完成,90%的评估在42天内完成。在基线时,973例患者中有231名(23.7%)已经在使用pH缓冲底盘。

在基线时收集的造口特征如表1所示。共有95%的患者接受了结肠造口术或回肠造口术(n=974)。造口的平均时间(n=898)为22.1个月,中位数为1.9个月。四分之三的受访者带造口生活时间不到12个月。不到一半的造口人群有共病或PSC。931例患者中有一半以上(567名(60.9%))患者没有导致造口周围皮肤风险的共病,951例患者中有486名(51.1%)患者在基线时报告没有PSC。在基线时报告PSC的患者中,最常见的是急性刺激性皮炎(24.5%,n=233),其次是浸渍(12.3%,n=117)和慢性刺激性皮炎(6.9%,n=66)。

DET和造口周围皮肤疼痛评分结果

共有797例患者符合纳入标准,且DET评分数据有效。随DET得分下降,皮肤在使用pH缓冲底盘后显示出显著改善(图1A)。前期评估平均DET评分(SD)为3.21(3.39)分,后期评估平均DET评分(SD)为1.36(2.40)分。对于整个用户评估人群,DET(SD)的平均变化显著,下降了1.85(3.01)个点(p<0.001)(表2)。

开始评估前已在使用底盘的患者的平均DET评分从0.79分降至0.52分;这种变化无显著统计学差异。相比之下,在前期评估时开始使用底盘的患者DET评分平均降低2.35分(从3.98分降至1.63分,p<0.001)。

在观察了整个群体的造口周围皮肤健康状况后,我们按PSC类型对数据进行了分层。使用465例患者记录的635个PSC,按皮肤状况对DET评分的变化进行了细分(图2)。所有皮肤状况下的DET评分均有降低。对于经检验具有统计学意义的皮肤状况(即,n≥30的状况),DET评分显著下降幅度最大的是浸渍(3.9),其次是急性刺激性皮炎(3.5)、产品敏感性(2.8)和慢性刺激性皮炎(2.3),而在基线时无PSC的患者中下降幅度最小(0.6分)(p<0.001)。

与DET评分类似,在抽样队列中,造口周围皮肤疼痛评分在统计学上显著降低。392例患者中208名(53.1%)的疼痛评分下降,165例患者的疼痛评分没有变化,19例患者的疼痛评分上升(图1B)。在报告得分的392例患者中,平均(SD)疼痛得分降低了1.8(2.6)分(p<0.001)(表2)。按PSC类型分层时,所有皮肤状况下的造口周围疼痛评分均降低(图2)。对于经检验具有统计学意义的皮肤状况(n≥30,p<0.001),每个检验类别的评分均显著下降-急性刺激性皮炎(3.4)、慢性刺激性皮炎(2.2)和浸渍(3.3)。此外,基线时无PSC患者报告的疼痛评分出现具有统计学意义的降低(0.7,p<0.001)。

根据这一趋势,我们发现在前期评估和后期评估,DET和疼痛评分之间均存在统计上显著的相关性。DET和疼痛评分之间的相关系数(rho)分别为0.77(前期评估)和0.53(后期评估)(两者均p<0.001)。还观察到DET变化与疼痛评分之间的相关性(0.73)(图1C)。综上所述,这些发现表明,无论是否使用pH缓冲底盘,DET和疼痛评分都是紧密一致的。尽管这些相关性对临床医生来说已较为直观,但这份用户评估第一次明确报告了这一趋势。

医疗资源使用

根据我们的资源使用结果,该底盘有可能通过提供更长的佩戴时间以及更少的相关造口附件和局部造口周围药物使用来降低造口护理成本。900例患者中有342名(38.0%)在使用pH缓冲底盘时佩戴时间延长。每天更换造口袋超过一次的患者数量减少了55%。此外,达到2天或更长佩戴时间的患者数量增加了34%。佩戴时间方面的改进使得每月袋数减少,从前期评估的31.2(20.0)袋减少到后期评估的23.7(16.3)袋。

我们的评估还收集了每位患者使用的造口相关附件的信息。前期评估中最常用的附件是粘合剂去除剂,其次是封口条、造口带和糊剂。在后期评估中,使用糊剂、封口条、粘胶去除剂、皮肤保护剂、造口粉、造口带、支撑带、法兰扩展器和胶带的患者百分比均有所下降(表3)。无需任何附件的患者百分比从24.6%增加至34.5%(p<0.001),相对变化为+40.2%。在评估期间,共有52例患者使用局部造口周围皮肤药物;26名(50%)患者在后评估中注意到药物使用减少,7例患者报告使用增加。

临床医生对pH缓冲底盘的满意度和经验

接下来,我们试图记录临床医生对pH缓冲底盘在多个维度上的满意度,大多数人对所检查的所有属性报告“满意”或“非常满意”(图3)。pH缓冲底盘设计中认可的四个属性——易用性、与造口周围皮肤的粘附性、易去除性和吸收水分的能力——有至少86%临床医生表示满意。结果显示的高满意度表明临床医生认为这些底盘和技术对他们的工作和患者具有很高的价值。

满意度答复与临床医生推荐pH缓冲底盘的可能性呈正相关(图3)。960名临床医生中,共有829名(86%)医生“非常可能”或“可能”推荐将该产品纳入评估患者的造口护理计划。对患者提出相同的问题时,681例患者中有567名(83%)表示“非常可能”或“可能”推荐该产品。同样,满意度答复的结果和推荐pH缓冲底盘的可能性与积极的皮肤结果一致。

讨论

pH缓冲底盘用于在所有液体暴露条件下保持皮肤的酸性保护膜。体外评估表明,暴露于碱性盐水后,pH缓冲底盘保持在皮肤的健康pH范围内,pH值与底盘下可能泄漏的流出物相似21。这些特质可能是造口护理护士所期望的,因为造口输出物多和大便过多尤其常见22,他们希望从造口手术一开始就为患者提供最好的护理。根据DET和造口周围皮肤疼痛评分在统计学上显著降低的情况,我们的研究结果表明,使用pH缓冲底盘可以改善皮肤健康。在前期评估之前,约有24%的受试者使用pH缓冲底盘。与预期一致,结果表明在评估前后,DET得分没有统计学意义上的显著变化。相比之下,在前期评估时转而使用pH缓冲底盘的受试者在使用pH缓冲底盘后,DET评分出现具有统计学意义的降低。这两项发现的评估偏差最小,因为我们预计已经使用pH缓冲底盘(前期评估之前)的患者DET评分不会有任何实质性变化。

前人的研究对带造口生活的不良影响之一——疼痛,已经作了评估23。但据作者所知,对造口周围皮肤疼痛与DET评分之间关系的分析,本次为第一份发表的评估。疼痛是临床医生报告高度强调的问题,其对HRQoL的影响可能会使人身体衰弱。Kini等人的研究结果表明,慢性疼痛患者的平均症状效用得分为0.7724。换句话说,患者愿意用他们预期寿命的23%来避免疼痛。我们的研究结果表明,使用底盘与患者报告的造口周围皮肤疼痛显著减少相关。我们相信,造口护理护士在确定病人疼痛和提供明智解决方案时会将这份有力证据纳入考虑。此外,我们发现皮肤损伤的变化(通过DET分数定量测量)与疼痛之间存在正相关,这是此前从未探讨过的。

造口袋渗漏和疼痛会对患者产生负面的心理影响。有证据表明,造口周围皮肤健康的患者的HRQoL得分高于造口周围皮肤受刺激的患者16,25。此外,渗漏和造口袋安全性不足问题会导致患者无法活动,引发各种社会和身体应对机制需求。26在我们的评估中,在所有PSC类别中,DET和造口周围疼痛评分均有改善,且这些变化对于急性刺激性皮炎、慢性刺激性皮炎和浸渍而言,均具有统计学意义。这些发现表明,pH缓冲底盘减轻了底盘渗漏的影响,从而降低了PSC的严重程度和发生率,提高了疼痛评分。因此,pH缓冲底盘有可能通过减少或预防PSC来改善HRQoL。

有了pH缓冲底盘,患者的佩戴时间更长,造口附件和局部皮肤药物的使用更少。这些有利结果可使造口护理计划简单化,无需多个处方和耗时的步骤。对昂贵造口相关资源的需求减少也表明pH缓冲底盘具有潜在经济效益。需要额外分析来确认我们的发现能够转化为潜在的成本节约。

除临床结果外,我们发现临床医生对pH缓冲底盘的满意度和推荐度都很高,另外他们对底盘使用和移除便利性、造口周围皮肤的粘附性以及佩戴时间等方面也表示满意。虽然没有对患者满意度进行调查,但通过评估患者对pH缓冲底盘解决不适的能力的感知,临床医生报告了满意结果。

综上,这些评估结合真实世界的证据,证明pH缓冲技术对造口周围皮肤健康结果的影响。我们采用了受试者内设计来最大限度地减少选择偏差,确保有足够的统计功效来估计pH缓冲底盘对结果的影响。该评估没有对每位临床医生的护理标准进行任何强行更改,遵循了真实世界实践原则。此外,使用了特定的调查工具,均为经过验证且可靠的评估工具,可比较不同研究的结果。

局限性

由于这项研究的观察性质,只能从研究结果中建立关联(而非因果关系)。完成前期评估和后期评估之间的时间因患者而异,可能导致答复中出现未知方向的偏倚。对DET评分而言,敏感性分析表明,DET随时间的评分变化不具有统计学意义。对于本次用户评估,没有向参与的临床医生提供有关使用DET或疼痛量表的正式培训;因此,评估本身可能因临床医生的经验而异。为确保符合欧盟《一般数据保护条例》,对评估表进行了必要的修改。一共发布了三个版本。因此,某些调查答复未能囊括每位患者。

我们虽然认为我们的跨国临床医生和患者群体是一个优势,但我们没有考虑每个国家的护理标准差异或造口护理中典型患者或临床医生工作模式的差异。没有将个人带造口生活的总时间计入数据分析。此外,我们的研究不是比较评估,因此我们无法将pH缓冲底盘的影响与其他因素分开。

结论

皮肤底盘应该安全、可靠、经济,且保持造口周围皮肤健康。我们的评估在信息丰富的评估基础上,展示了产品在保护造口周围皮肤的基本方面的实际效果。本研究旨在帮助患者及其医疗保健提供者在护理造口和造口周围皮肤方面作出明智决定。研究利用临床医生和患者报告的结果生成综合数据,并通过各种调查工具提供反馈。可以从DET和造口周围疼痛评分降低看出,患者通过使用pH缓冲底盘,获得了积极的护理结果,同时通过增加佩戴时间、减少造口附件和局部造口周围皮肤药物的使用,带来了潜在的经济利益。

我们特别发现,造口周围皮肤疼痛,虽然经常无法解释,但对于造口患者来说是一个突出的问题。而使用pH缓冲底盘与减轻疼痛相关。此外,在我们的用户评估群体中,多种皮肤疾病的皮肤健康得到改善。这些结果可能为造口护理护士治疗患有特定PSC或需预防PSC的患者提供有用信息。选择维护皮肤pH值的造口底盘可有助于皮肤健康,提升患者幸福感。

致谢

感谢来自Hollister Incorporated,Libertyville,IL的Gary Inglese RN,MBA对手稿的宝贵意见。医学写作服务由Oxford PharmaGenesis,Incorporated,Newtown,PA的Sabiha Runa博士提供,并由Hollister Incorporated,Libertyville,IL资助。

利益声明

这项研究由美国Hollister Incorporated,Libertyville,IL,USA赞助。David Fischer、Jimena Goldstine和George Skoutrianos是Hollister Incorporated的员工。研究期间,Louise Hannan是丹麦Dansac A/S, Fredensborg的员工。Scarlett Summa从德国Lectures, Erlangen和德国ICEF consulting, Bonn获得个人费用和非财务支持。最后,参与本次评估的英国临床医生中有44%(184名中的81名)受雇于或由Dansac A/S赞助;没有向任何参与的临床医生提供奖励。

Author(s)

Scarlett Summa

Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurse

University Hospital, Erlangen, Chirurgische Klinik, Stomatherapie, Krankenhausstr. 12, 91054 Erlangen, Germany

George Skountrianos

Statistician, Global Clinical Affairs

Hollister Incorporated, 2000 Hollister Drive, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA

Jimena V Goldstine*

Director, Value and Evidence Strategy

Hollister Incorporated, 2000 Hollister Drive, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA

Email: Jimena.goldstine@hollister.com

Louise Hannan**

Global Marketing Manager

Dansac A/S, Lille Kongevej 304, 3480 Fredensborg, Denmark

David Fischer

Global Market Insights Manager

Hollister Incorporated, 2000 Hollister Drive, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA

* Corresponding author

** Affiliation at the time of the research

References

- Almutairi D, LeBlanc K, Alavi A. Peristomal skin complications: what dermatologists need to know. Int J Dermat 2018;57(3):257–264.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Eaves D, Oster G. Risk and economic burden of peristomal skin complications following ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019.

- Fluhr JW, Elias PM. Stratum corneum pH: formation and function of the ‘acid mantle’. Exog Dermatol 2002;1:163–175.

- Yosipovitch G MH. Skin surface pH: a protective acid mantle. Cosmet Toilet 1996;111(12):101–102.

- Erwin-Toth P, Thompson SJ, Davis JS. Factors impacting the quality of life of people with an ostomy in North America: results from the Dialogue Study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;39(4):417–422.

- Fellows J, Forest Lalande L, Martins L, Steen A, Størling ZM. Differences in ostomy pouch seal leakage occurrences between North American and European residents. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(2):155–159.

- Formijne Jonkers HA, Draaisma WA, Roskott AM, van Overbeeke AJ, Broeders IA, Consten EC. Early complications after stoma formation: a prospective cohort study in 100 patients with 1-year follow-up. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012;27(8):1095–1099.

- Wilson M. Incontinence-associated dermatitis from a urinary incontinence perspective. Br J Nurs 2018;27(9):S4–S17.

- Andersen PH, Bucher AP, Saeed I, Lee PC, Davis JA, Maibach HI. Faecal enzymes: in vivo human skin irritation. Contact Dermatitis 1994;30(3):152–158.

- Metcalf C. Managing moisture-associated skin damage in stoma care. Br J Nurs 2018;27(22):S6–s14.

- Kelly-O’Flynn S, Mohamud L, Copson D. Medical adhesive-related skin injury. Br J Nurs 2020;29(6):S20–S26.

- Colwell JC, Pittman J, Raizman R, Salvadalena G. A randomized controlled trial determining variances in ostomy skin conditions and the economic impact (ADVOCATE trial). J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(1):37–42.

- Voegeli D, Karlsmark T, Eddes EH, et al. Factors influencing the incidence of peristomal skin complications: evidence from a multinational survey on living with a stoma. Gastrointest Nurs 2020;18(Sup4):S31–S38.

- Colwell JC, McNichol L, Boarini J. North America wound, ostomy, and continence and enterostomal therapy nurses current ostomy care practice related to peristomal skin issues. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(3):257–261.

- Hubbard G, Taylor C, Beeken B, et al. Research priorities about stoma-related quality of life from the perspective of people with a stoma: a pilot survey. Health Expect 2017;20(6):1421–1427.

- Nichols T. Health utility, social interactivity, and peristomal skin status: a cross-sectional study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(5):438–443.

- Martins L, Tavernelli K, Sansom W, et al. Strategies to reduce treatment costs of peristomal skin complications. Br J Nurs 2012;21(22):1312–1315.

- Meisner S, Lehur PA, Moran B, Martins L, Jemec GB. Peristomal skin complications are common, expensive, and difficult to manage: a population based cost modeling study. PloS One 2012;7(5):e37813.

- Martins L, Ayello E, Claessens I, et al. The Ostomy Skin Tool: tracking peristomal skin changes. Br J Nurs 2010;19:932–964.

- McCaffery M, Beebe A. Pain: clinical manual for nursing practice. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1989.

- Taylor M PG, Skountrianos G. Comparative laboratory testing of ostomy seal products. Paper presented at Association for Stoma Care Nurses 2018; UK.

- Baker ML, Williams RN, Nightingale JM. Causes and management of a high-output stoma. Colorectal Dis 2011;13(2):191–197.

- Pittman J, Bakas T, Ellett M, Sloan R, Rawl SM. Psychometric evaluation of the ostomy complication severity index. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(2):147–157.

- Kini SP, DeLong LK, Veledar E, McKenzie-Brown AM, Schaufele M, Chen SC. The impact of pruritus on quality of life: the skin equivalent of pain. Arch Dermatol 2011;147(10):1153–1156.

- Goldstine J, van Hees R, van de Vorst D, Skountrianos G, Nichols T. Factors influencing health-related quality of life of those in the Netherlands living with an ostomy. Br J Nurs 2019;28(22):S10–S17.

- Colwell JC, Bain KA, Hansen AS, Droste W, Vendelbo G, James-Reid S. International consensus results: development of practice guidelines for assessment of peristomal body and stoma profiles, patient engagement, and patient follow-up. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(6):497–504.