Volume 41 Number 3

Temporary diverting end-colostomy in critically Ill children with severe perianal wound infection

Emrah Gün, Tanıl Kendirli, Edin Botan, Halil Özdemir, Ergin Çiftçi, Kübra Konca, Meltem Koloğlu, Gülnur Göllü, Özlem Selvi Can, Ercan Tutar, Ahmet Rüçhan Akar and Erdal İnce

Keywords Colostomy, diverting colostomy, meningococcemia, pediatric, perianal

For referencing Gün E et al. Temporary diverting end-colostomy in critically Ill children with severe perianal wound infection. WCET® Journal 2021;41(3):38-43

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.38-43

Submitted 24 June 2020

Accepted 25 September 2020

Abstract

Broad and deep perianal wounds are challenging in both adult and pediatric ICUs. These wounds, if contaminated with gastrointestinal flora, can cause invasive sepsis and death, and recovery can be prolonged. Controlling the source of infection without diverting stool from the perianal region is complicated. The option of protective colostomy is not well-known among pediatric critical care specialists, but it can help patients survive extremely complicated critical care management.

These authors present three critically ill children who required temporary protective colostomy for perianal wounds because of various clinical conditions. Two patients were treated for meningococcemia, and the other had a total artificial heart implantation for dilated cardiomyopathy. There was extensive and profound tissue loss in the perianal region in the patients with meningococcemia, and the patient with cardiomyopathy had a large pressure injury. Timely, transient, protective colostomy was beneficial in these cases and facilitated the recovery of the perianal wounds. Temporary diverting colostomy should be considered as early as possible to prevent fecal transmission and accelerate perianal wound healing in children unresponsive to local debridement and critical care.

Introduction

Open perianal wounds are challenging problems in ICUs, especially in morbidly obese adult patients because of poor tissue circulation, pressure-related tissue necrosis, and insufficient or inconsistent position changes. This problem is seen in paediatric ICUs (PICUs) less frequently than in adult ICUs. However, in paediatric patients, perianal wounds can be fatal. Open perianal wounds may lead to sepsis as a result of uncontrolled infection after contamination with gastrointestinal flora. Perianal sepsis is associated with a high mortality of up to 78%.1 The most common infections in neutropenic patients with perianal sepsis are caused by Escherichia coli and Enterococcus, Bacteroides, and Klebsiella species.2 This concept is well-known, but there are only a few reports about how to control it, especially in PICUs.

A temporary diverting colostomy can be used to keep feces out of the colon and off of skin that is inflamed, diseased, infected, or newly emerging. The procedure provides time for healing. Whether to perform a colostomy is still controversial; there are no consensus guidelines describing indications for and appropriate timing of colostomy.3 In addition, even though there is little information about the management of perineal burns and faecal diversion strategies in the literature, colostomy is generally recommended to prevent faecal contamination.4 Diverting colostomy remains the most common procedure in children when stool diversion is indicated.5

Meningococcemia is a severe infection in children associated with high mortality and significant morbidity if it is not treated efficiently and quickly. Occasionally, meningococcemia is seen as a severe form known as purpura fulminans (PF). Correct and timely management of PF is critical. Although there are several reports regarding the management of a patient with PF and severe tissue loss,6,7 no report describes how to control open perianal and gluteal wounds from the PF form of meningococcemia.

Here, the authors describe the cases of three critically ill children with extensive perianal tissue loss. Their cases invite a discussion about the timing of diverting colostomy, its duration, and associated outcomes. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, temporary diverting colostomy has not previously been considered in the management of PF.

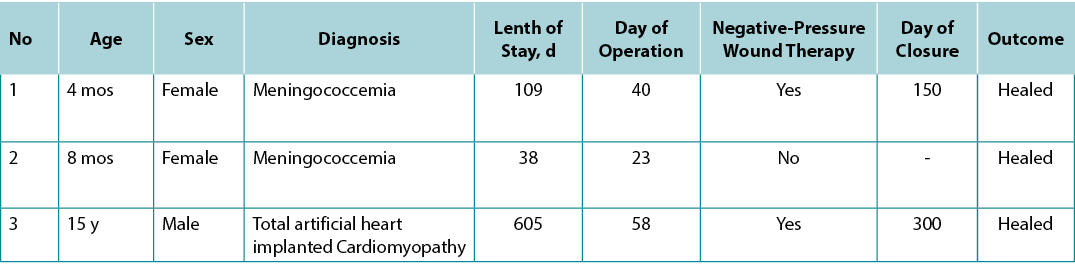

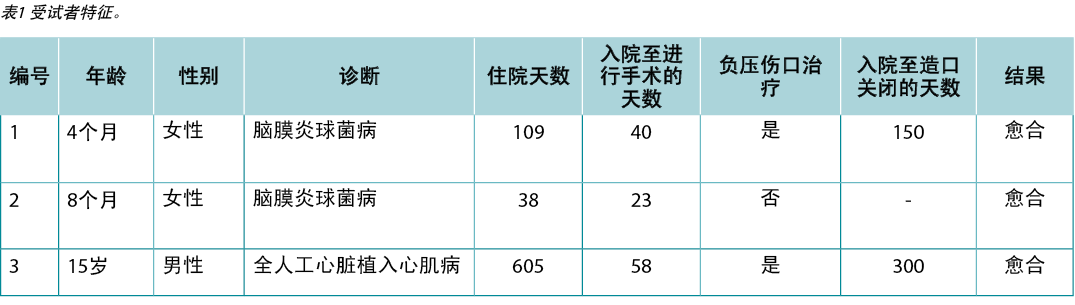

Written informed consent to reprint the case details and associated images was obtained from each patient’s family. All demographic features and clinical courses are reported in the Table.

Table1 participant characteristics.

Case 1

A 4-month-old girl was transferred to the authors’ PICU from another hospital because of fever and widespread petechial and purpuric rashes with suspicion of meningococcemia. She had extensive hemorrhagic purpuric lesions on her body and findings of decompensated septic shock (Figure 1A). The patient required intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation. Ceftriaxone, inotropic support, and hydrocortisone commenced. Laboratory workup showed severe metabolic acidemia, electrolyte imbalance, elevated acute phase reactants, and impaired coagulation parameters. Her blood culture showed Neisseria meningitides, but not in cerebrospinal fluid sample. During the follow-up, the patient underwent seven plasma exchange (PEX) sessions because of thrombocytopenia-associated multiorgan failure and continuous venovenous hemodialysis from fluid overload and sepsis for 6 days. Antibiotics were revised according to culture antibiograms during hospitalisation.

The patient was extubated on the 15th day of hospitalisation. Acinetobacter baumannii was isolated from necrotising wound culture in the perianal region. The patient developed septic shock, which was treated with fluid boluses, epinephrine, meropenem, and colistin. The interdisciplinary team decided to proceed with colostomy given that the patient had extensive infected necrotising perianal wounds, and preventing stool and gastrointestinal flora from coming into contact with deep open wounds was crucial for wound healing and treatment of sepsis (Figure 1B). A temporary diverting colostomy was performed on the 30th day of PICU admission without any surgical complication.

The patient’s open wounds were healed in a short time after colostomy, and she could eat on the 35th day of PICU admission. She was transferred to paediatric infectious diseases (PIDs) service without any oxygen therapy or antibiotics, and her colostomy was taken down in the fifth month of hospital admission after all of her open perianal wounds were healed (Figure 1C).

Currently, the patient is 20 months old, her mental findings are positive, and she can walk. However, she lost the distal parts of her hand and feet after autoamputation because of severe ischemic changes related to meningococcemia, and the skin of her right leg and foot is also compromised.

Figure 1, case 1. A, A 4-month-old girl presented with fever and widespread petechial and purpuric rashes, with suspicion of meningococcemia. Extensive ecchymosis and purpuric lesions were noted on the face, body, extremities, and perineal region. B, Before temporary diverting colostomy, deep and large necrotizing wounds in the perianal region and lower extremities are noted. C, This photograph was taken on the 35th day of pediatric ICU admission with the healing of the necrotizing perianal wound after diverting colostomy.

Case 2

A previously healthy 8-month-old girl was admitted to the authors’ hospital with a diagnosis of meningococcemia. As in the first case, the patient had petechial and purpuric lesions all over her body (Figure 2A). On presentation, she had decompensated septic shock findings, which were treated with fluid boluses, antibiotics, inotropes, vasopressors, and hydrocortisone. She was intubated and received respiratory support from a mechanical ventilator. The authors performed eight PEX sessions for thrombocytopenia-associated multiorgan failure. Her femoral pulses on the left leg were palpable, but Doppler ultrasound revealed no flow on the left popliteal artery. Her blood culture was positive for N meningitides, as was the cerebrospinal fluid. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were given to combat the facility-acquired infections during hospitalisation.

She had a diverting colostomy on the 23rd day of PICU admission to prevent extensive necrotising perianal wounds from contamination with stool (Figure 2B). After the colostomy, her clinical situation improved, infection abated, and the open and deep wounds improved in a short time. The patient was extubated on the 27th day of hospitalisation. She was transferred to the PID clinic for further care of her open wounds on the 38th day of PICU admission. She was discharged from hospital 83 days after her transfer to the PID service with fully healed perineal wounds and scheduled to have her colostomy closed. Unfortunately, her distal limbs did not improve, and she experienced an amputation (Figure 2C).

Figure 2, case 2. A, An 8-month-old girl presented with meningococcemia. Petechial and purpuric lesions all over her body were clearly noted. B, Severe perineal unstageable ulcers were contaminated with stool. C, Rapid healing after diverting colostomy operation.

Case 3

A 15-year-old boy was admitted to the authors’ PICU with decompensated biventricular heart failure and persistent ventricular arrhythmias. He was supported by emergency peripheral venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. He had a history of left ventricular thrombus removal operation 2 months prior at a different facility. He also had renal and liver failure.

After hemodynamic evaluation and interdisciplinary discussions, he received a 50-mL total artificial heart (TAH; SynCardia Systems LLC, Tucson, Arizona), implanted by the hospital’s transplantation team. During the postoperative period, he experienced ventilator-associated pneumonia and sepsis associated with pan-drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and developed multiple organ failure. He received supportive therapy including venovenous hemodiafiltration for 35 days and 22 PEX sessions. He underwent percutaneous tracheostomy on his 41st postoperative day; during this time, there were no TAH-related complications, and his clinical condition improved slowly.

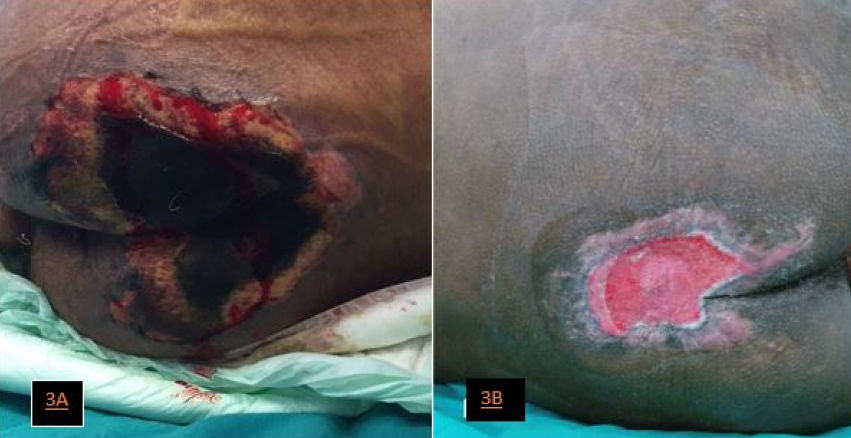

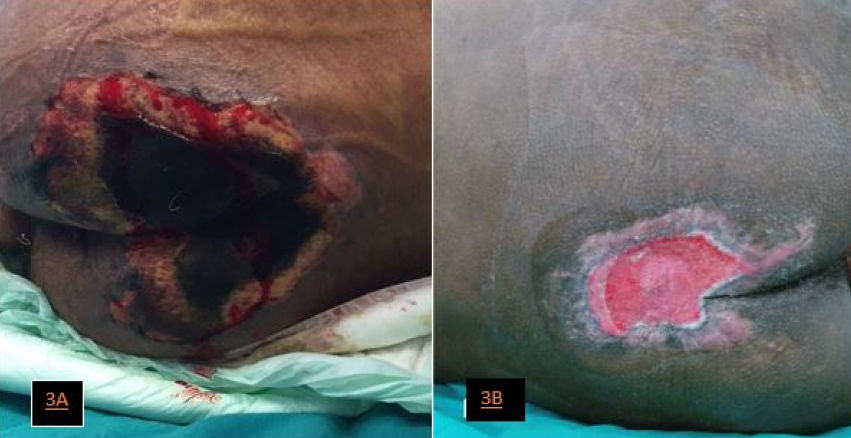

Earlier, during the third week of his PICU admission, and despite frequent position changes, he developed an unstageable pressure ulcer8 (UPU; Figure 3A) because of his lengthy illness, circulatory failure, and septic attacks. This sacral UPU was unresponsive to local care and deteriorated. Deep-tissue biopsy cultures confirmed the presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and pan-drug-resistant K pneumoniae. Accordingly, the decision to proceed with a temporary protective colostomy was made to eradicate the source of septic attacks and keep the patient on the heart transplant list. He had a sigmoid colostomy process on his 58th day of hospitalisation. Following colostomy and debridement of his UPU, negative-pressure wound therapy was applied, and the UPU healed after his transfer to PID.

Independent ambulation of the patient was achieved in the sixth month of PICU admission with an intensive physical therapy and rehabilitation program. Following independent ambulation, the patient’s hepatic and renal failure was resolved, and he was listed for heart transplantation. The patient’s colostomy was taken down in his 10th month of hospitalisation. He was successfully bridged to transplant by TAH and supportive care, but unfortunately, he died after the transplantation.

Figure 3, case 3. A, A 15-year-old boy who underwent total artificial heart implantation developed deep and unstageable pressure ulcers on the sacrococcygeal region and local sepsis. B, Sigmoid colostomy, repeated debridement, and negative-pressure wound therapy resulted in the improvement of the large pressure injury, which allowed the patient to bridge to heart transplantation.

Discussion

Perianal wounds often lead to sepsis in critically ill children, who are particularly susceptible to skin infections. Perianal skin lesions may cause significant problems, such as skin and soft-tissue necrosis and scarring extending to the sphincter apparatus, which can cause lifelong incontinence. Treatments include antimicrobial therapy, extensive debridement, and skin graft.3

There are few reports regarding perianal sepsis management.1 Temporary colostomy should be considered in patients unresponsive to local care and surgical debridement. Colostomy facilitates wound healing by keeping feces out of the colon and off of inflamed, diseased, infected, or newly emerging skin. Performing a colostomy is controversial, and there are no consensus guidelines describing appropriate indications or timing of colostomy.3

However, paediatric surgeons are familiar with the colostomy procedure, given that it is required in children with anorectal malformations (especially rectourethral or rectovesical neck fistulas), long-segment Hirschsprung disease, or Crohn disease; in cases of perineal trauma; or in patients presenting with rectosigmoid perforation. Complications of an adequately performed colostomy are infrequent in children. The most common early complications are skin irritation, poor stoma location, and local necrosis, and the most common late complications are skin irritation, prolapse, and stenosis.4 There were no colostomy-related complications in these three cases.

Temporary, protective, diverting colostomy and its takedown are technically accessible, fast, and comparatively safe procedures in children. Therefore, these authors suggest that there is no basis to avoid colostomy when there is a potentially life-threatening perianal infected wound, and local debridement and wound care are not sufficient for proper wound healing. The other important point is that the colostomy completely diverts stool from the perianal region. Loop colostomies are not suitable for these patients, and diverting colostomies are needed.

Even though there are only a few reports on the management of perineal burns and faecal diversion strategies, the colostomy is generally recommended to prevent faecal contamination. Perianal burns are necessarily exposed to faecal contamination.4 This may cause sepsis and graft loss, contaminate wounds, delay wound healing, and lead to scar contracture or anal and urinary malfunction.4,9 Diverting colostomy in children remains the procedure of choice when stool diversion is indicated.5

Quarmby et al10 reported a successful series of colostomies in 13 paediatric patients with perineal burns; wound healing was achieved in 12 patients. Price et al9 performed protective colostomies in 29 children with perianal burns on day 6 after admission and therapeutic colostomies in 16 patients with deep wound infection and sepsis on day 24. In all cases, they achieved marked improvement and healing of the perianal burn wounds, although two patients died of septic shock. Five (11%) of their patients had complications related to the colostomies such as dehiscence and stomal protrusion requiring manual reduction.9

There may be extensive necrotising perianal wounds in patients with meningococcemia, as seen in this patient series. In this population, colostomy may be required to prevent local and systemic infections. Fulminant meningococcemia is a relatively rare, life-threatening disease induced by N meningitides. It may cause a fatal form of septic shock, and most deaths occur within the first 24 hours. It is distinct from other forms of septic shock, mostly because of the appearance of hemorrhagic skin lesions.7 Meningococcemia is one of the precursors to PF, which is characterised by widespread hemorrhagic skin necrosis from vascular thrombosis. Extensive purpuric necrosis may develop in the extremities and cause amputation. When peripheral gangrene occurs, amputation is indicated because this condition itself can induce sepsis.6

These patients had gangrenous areas and deep clefts in the perineal region and lower extremity. Colostomy was performed in these patients to prevent contamination with feces and perianal wound-induced sepsis. As far as the authors are aware, there are no previously reported cases with meningococcemia who underwent colostomy to prevent perianal sepsis.

The beneficial effects of temporary protective diverting colostomy include controlling local and systemic sepsis, reducing colonisation and spread of multidrug-resistant bacteria, and decreasing multiple drug exposure. These effects may lead to rapid healing of open perianal wounds, restricting catabolic state, and weight loss with quicker healing. The patients may be discharged from PICU in a relatively shorter time.3,7 Before colostomy was performed in these three cases, irrigation with normal saline, a thin layer of antibacterial ointment such as mupirocin, and an antiseptic dressing were used as local wound care. Negative-pressure wound therapy was given to two patients after colostomy. The authors noted all the beneficial effects of diverting colostomy in these patients. The decision to proceed with colostomy was made in the early period of PICU admission. Therefore, the authors did not note any multidrug-resistant bacteria colonisation and septic attacks related to these bacteria.

The providers in the authors’ facility discuss every new development, good or bad, with PICU parents daily and carefully discuss all possible outcomes. Generally, families are prepared for possible deterioration in patient status. However, the families of all three patients were very pleased that there was no increase in wound infections at the end of this difficult process.

Conclusions

Temporary diverting colostomy has many benefits for treating perianal wound infection, septic attacks, and tissue destruction by preventing faecal contamination in critically ill children with large open perineal wounds. Although this clinical condition is not rare, protective colostomy is not well-known among paediatric critical care specialists. These authors believe that this intervention helped these patients to stay alive during their extremely complicated critical care management. Consequently, temporary protective diverting colostomy should be considered as early as possible to prevent faecal transmission and accelerate wound healing in children requiring critical care with large perianal wounds that are not responsive to local debridement and care.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the paediatric ICU nursing staff for all their efforts and support for our critically ill paediatric patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

患有严重肛周伤口感染的危重患儿行临时转流结肠造口术

Emrah Gün, Tanıl Kendirli, Edin Botan, Halil Özdemir, Ergin Çiftçi, Kübra Konca, Meltem Koloğlu, Gülnur Göllü, Özlem Selvi Can, Ercan Tutar, Ahmet Rüçhan Akar and Erdal İnce

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.38-43

摘要

宽而深的肛周伤口在成人和儿科ICU中都具有挑战性。如果这些伤口被胃肠道菌群污染,会导致侵袭性败血症和死亡,恢复时间也会延长。在不将粪便从肛周区域转流的情况下控制感染源颇为复杂。保护性结肠造口术在儿科重症监护专家中鲜为人知,但其可以帮助患者在极其复杂的重症监护管理中存活下来。

这些作者介绍了三名危重儿童,由于各种临床状况,需要临时保护性结肠造口术来治疗肛周伤口。两例患者因脑膜炎球菌病接受治疗,另一例患者因扩张型心肌病接受了全人工心脏植入术。脑膜炎球菌血症患者肛周区域有广泛严重的组织缺损,心肌病患者有较大的压力性损伤。几位患者可从及时、短暂、保护性结肠造口术中受益,促进肛周伤口的恢复。应尽早考虑临时转流结肠造口术,以防止粪便传播并加速对局部清创和重症监护无反应的儿童的肛周伤口愈合。

引言

开放性肛周伤口在ICU中是具有挑战性的问题,尤其在病态肥胖的成年患者中尤为突出,此类患者组织循环不良、压力相关的组织坏死、体位变换不足或不协调。这个问题在儿科ICU(PICU)中出现的频率低于成人ICU。但在儿科患者中,肛周伤口可能致命。由于被胃肠道菌群污染后不受控制的感染,开放的肛周伤口可能导致败血症。肛周脓毒症的死亡率高达78%。1粒细胞减少的肛周脓毒症患者最常见的感染是由大肠杆菌和肠球菌、拟杆菌和克雷伯氏菌属引起。2这个概念众所周知,但关于如何控制的报道很少,尤其是在PICU中。

临时转流结肠造口术可用于防止粪便进入结肠,避免接触发炎、患病、感染或新生皮肤。此手术为愈合提供了时间。是否进行结肠造口术仍存在争议;没有描述结肠造口术的指征和适当手术时机的共识指南。3此外,尽管文献中关于会阴烧伤的管理和粪便转移策略的信息很少,但通常建议进行结肠造口术以防止粪便污染。4当需要大便转流时,转流结肠造口术仍然是儿童最常见的手术。5

脑膜炎球菌病是一种严重的儿童感染,如果没有得到有效和迅速的治疗,会导致高死亡率和显著发病率。脑膜炎球菌病偶尔有一种严重形式,称为暴发性紫癜(PF)。正确及时地管理PF至关重要。尽管存在一些关于PF和严重组织损失患者的管理的报告,6,7没有报告对如何控制PF形式的脑膜炎球菌病引起的肛周和臀部开放性伤口进行过描述。

此处,作者描述了三名患有广泛肛周组织损失的危重儿童的病例。三个病例引发了关于转流结肠造口术的时间、持续时间和相关结果的讨论。据作者所知,以前在PF的管理中没有考虑过临时转流结肠造口术。

从每位患者的家属中获得了重印病例详细信息和相关图像的书面知情同意书。表中报告了所有人口统计学特征和临床过程。

病例1

一名4个月大的女孩因发烧、大面积瘀点、紫癜性皮疹和疑似脑膜炎球菌病从另一家医院转移到作者所在的PICU。患儿身体有大面积的出血性紫癜病变,并出现失代偿性感染性休克(图1A)。患者需要插管和有创机械通气。开始使用了头孢曲松、正性肌力药物和氢化可的松。实验室检查显示严重的代谢性酸血症、电解质失衡、急性期反应物升高和凝血参数受损。患儿血培养显示存在脑膜炎双球菌,但脑脊液样本中不存在。在随访期间,由于血小板减少症相关的多器官衰竭和连续6天因体液超负荷和败血症导致的静脉血液透析,患者接受了7次血浆置换(PEX)治疗。住院期间根据培养抗菌谱对抗生素进行了修改。

患儿在住院第15天拔管。从肛周区域的坏死伤口培养物中分离出了鲍曼不动杆菌。患儿出现感染性休克,给予液体推注、肾上腺素、美罗培南和粘菌素治疗。鉴于患儿有广泛的感染坏死性肛周伤口,跨学科团队决定进行结肠造口术,防止粪便和胃肠道菌群接触深部开放性伤口对于伤口愈合和脓毒症治疗至关重要(图1B)。在PICU入住第30天进行了临时转流结肠造口术,未出现任何手术并发症。

患儿的开放性伤口在结肠造口术后短时间内愈合,入住PICU第35天即可进食。在没有使用任何氧疗或抗生素的情况下,患儿被转入了儿科传染病门诊(PID)接受治疗,在所有开放性肛周伤口愈合后,其结肠造口在入院的第5个月被拆除(图1C)。

目前,该患儿已满20个月,精神状态良好,可以行走。然而,由于脑膜炎球菌病相关的严重缺血性改变,她在自体截肢后失去了手和脚的远端部分,右腿和右脚的皮肤也受到损害。

图1,病例1. A,一名4月大的女孩因发烧和大面积瘀点、紫癜以及疑似脑膜炎球菌病就诊。面部、身体、四肢和会阴部有大面积瘀斑和紫癜性病变。B,在临时转流结肠造口术之前,注意到肛周区域和下肢的深而大的坏死性伤口。C,这张照片是在入住儿科ICU第35天拍摄,在转流结肠造口术后,坏死性肛周伤口正在愈合。

病例2

一例先前健康的8个月大女孩被送往作者所在的医院,经诊断为脑膜炎球菌病。与第一个病例一样,患儿全身都有出血斑疹和紫癜性病变(图2A)。就诊时,患儿出现失代偿性感染性休克,接受了液体推注、抗生素、正性肌力药、血管加压药和氢化可的松治疗。她接受了插管和机械呼吸机支持。作者针对血小板减少症相关的多器官衰竭进行了8次PEX治疗。患儿左腿可触及股动脉搏动,但多普勒超声显示左腘动脉没有血流。她的血培养对N脑膜炎球菌呈阳性,脑脊液也呈阳性。在住院期间给予其广谱抗生素以对抗设备获得性感染。

在入住PICU的第23天,对患儿进行了转流结肠造口术,以防止大面积坏死的肛周伤口被粪便污染(图2B)。结肠造口术后,患儿临床情况好转,感染减轻,开放性和深部伤口在短时间内得到改善。患儿在住院第27拔管。在入住PICU的第38天,她被转移到PID门诊以进一步护理其开放性伤口。她在转入PID门诊83天后出院,会阴伤口完全愈合,计划关闭结肠造口。不幸的是,她的四肢没有得到改善,经历了截肢(图2C)。

图2,病例2.A,一名8个月大的女孩出现脑膜炎球菌病。其全身的点状和紫癜性皮损清晰可见。B,严重会阴部不明确分期溃疡被粪便污染。C,转流结肠造口术后的快速愈合。

病例3

一名15岁男孩因失代偿性双心室心力衰竭和持续性室性心律失常入住作者的PICU。对其使用了紧急外周静脉动脉体外膜肺氧合进行支持。2个月前,他曾在另一家机构做过左心室血栓清除手术。他还患有肾功能衰竭和肝功能衰竭。

经过血液动力学评估和跨学科讨论,患儿接受了由医院移植团队植入的50-mL全人工心脏(TAH; SynCardia Systems LLC, Tucson, Arizona)。在术后期间,他出现呼吸机相关性肺炎和泛耐药肺炎克雷伯菌相关的败血症,并发生多器官功能衰竭。对其进行了支持疗法,包括35天的静脉血液透析滤过和22次PEX治疗。他在术后第41天接受了经皮气管切开术;期间未出现TAH相关并发症,临床情况缓慢好转。

此前,在入住PICU的第三周,尽管经常变换体位,但由于长期患病、循环衰竭和脓毒症发作,患儿出现了不明确分期压疮8(UPU;图3A)。这种骶骨不明确分期压疮对局部护理无反应,发生恶化。深部组织活检培养证实存在耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌和泛耐药肺炎克雷伯菌。因此,决定进行对患儿临时保护性结肠造口术以根除脓毒症发作的根源,并将其保留在心脏移植名单上。在住院第58天,患儿进行了乙状结肠造口术。在对其UPU进行结肠造口术和清创后,进行了负压伤口治疗,转入PID门诊后PUP愈合。

通过强化物理治疗和康复计划,患者在入住PICU的第6个月实现了独立行走。独立行走后,患儿的肝肾功能衰竭得到解决,并被列入心脏移植名单。患儿的结肠造口在住院的第10个月被拆除。通过TAH和支持治疗,患儿成功过渡到移植阶段,而不幸的是,他在移植后死亡。

图3,病例3.A,一名接受全人工心脏植入术的15岁男孩在骶尾部出现深部且不明确分期压疮和局部败血症。B、乙状结肠造口、反复清创和负压伤口治疗改善了大压力性损伤,让患者能够过渡到心脏移植。

讨论

危重儿童的肛周伤口常常导致败血症,他们特别容易受到皮肤感染。肛周皮肤损伤可能导致严重问题,例如皮肤和软组织坏死,疤痕延伸至括约肌,可能导致终生失禁。治疗包括抗菌治疗、大面积清创和皮肤移植。3

关于肛周脓毒症治疗的报告稀少。1对于局部护理和手术清创无反应的患者,应考虑进行临时结肠造口术。结肠造口术通过防止粪便接触结肠以及发炎、患病、感染或新生皮肤来促进伤口愈合。进行结肠造口术存在争议,并且没有描述结肠造口术的适当适应症或手术时机的共识指南。3

不过,小儿外科医生熟悉结肠造口手术,因为有肛门直肠畸形(尤其是直肠尿道或直肠膀胱颈瘘)、长段先天性巨结肠或克罗恩病的儿童需要此类手术,另也适用于会阴外伤,或出现直肠乙状结肠穿孔的患者。充分进行结肠造口术的并发症在儿童中并不常见。最常见的早期并发症是皮肤刺激、造口位置不良和局部坏死,最常见的晚期并发症是皮肤刺激、脱垂和狭窄。4这三例病例均未发生结肠造口相关并发症。

临时性、保护性、转流性结肠造口术及其拆除在技术上是可行的、快速且相对安全的儿童手术。因此,本文作者认为,当存在可能危及生命的肛周感染性伤口且局部清创和伤口护理不足以使伤口正常愈合时,没有理由不采取结肠造口术。另一个重要的点是结肠造口可完全将粪便从肛周区域转移。这类患者不适合环状结肠造口术,需进行转流结肠造口术。

尽管关于会阴烧伤和粪便转流策略的报告还在少数,一般仍建议进行结肠造口术以防止粪便污染。肛周烧伤必然会受到粪便污染。4这可能会导致败血症和移植物丢失、污染伤口、延迟伤口愈合,并导致瘢痕挛缩或肛门和泌尿系统功能障碍。4,9当儿童需要粪便转流时,转流结肠造口术仍然是首选手术。5

Quarmby等人10报告了对13名会阴部烧伤患儿进行的一系列成功的结肠造口术;12例患者的伤口愈合。Price等人9对入院第6天的29名肛周烧伤儿童进行了保护性结肠造口术,并对入院第24天的16名深部伤口感染和败血症患者进行了治疗性结肠造口术。所有病例中,尽管有两例患者死于感染性休克,但所有患者的肛周烧伤伤口均获得显著改善和愈合。其中5名(11%)的患者出现与结肠造口术相关的并发症,例如开裂和造口脱垂需要手动复位。9

正如本文病例中所见,脑膜炎球菌病患者可能存在大面积坏死性肛周伤口。在此类病例中,可能需要进行结肠造口术以预防局部和全身感染。暴发性脑膜炎球菌病是一种由脑膜炎奈瑟菌引起的相对罕见且可危及生命的疾病。此病可能导致致命的感染性休克,大多数死亡发生在休克24小时内。此病导致的休克与其他形式的感染性休克不同,主要原因为出现出血性皮肤病变。7脑膜炎球菌病是PF的前兆之一,其特征是血管血栓形成引起的大面积出血性皮肤坏死。四肢可能会出现大面积紫癜性坏死并导致截肢。当发生外周坏疽时,需要截肢,因为这种情况本身会诱发败血症。6

这些患者在会阴区和下肢有坏疽区和深部裂口。对这些患者进行结肠造口术以防止粪便污染和肛周伤口引起的败血症。据作者所知,之前没有报告过接受结肠造口术以预防肛周脓毒症的脑膜炎球菌病病例。

临时保护性转流结肠造口术的有益作用包括控制局部和全身性败血症,减少多重耐药菌的定植和传播,并减少多种药物暴露。这些作用可使开放性肛周伤口快速愈合,限制分解代谢状态,并通过更快的愈合限制体重下降。患者可以在相对较短的时间内离开PICU。3,7这3例患者在进行结肠造口术前,均使用生理盐水冲洗,涂上薄层莫匹罗星等抗菌药膏,再使用抗菌敷料进行局部伤口护理。两例患者在结肠造口术后接受了负压伤口治疗。作者发现在这些患者中改道结肠造口术都起到了有益效果。进行结肠造口术的决定是在入住PICU早期做出的。因此,作者没有发现任何与这些细菌相关的多重耐药菌定植和败血症发作。

无论疾病进展好坏,作者所在医院的手术医生会每天告知PICU父母新的疾病变化情况,同时也会与之仔细讨论所有可能的结果。通常,家属已准备好应对患者状况可能恶化的情况。不过,直到这个艰难的过程结束,伤口感染都没有增加,三例患者的家属都很高兴。

结论

临时转流结肠造口术通过预防会阴大伤口的危重儿童的粪便污染,在治疗肛周伤口感染、脓毒症发作和组织破坏方面益处众多。尽管这种临床情况并不罕见,但保护性结肠造口术在儿科重症监护专家中仍鲜有人知。本文作者认为,这种干预措施帮助了这些患者在极其复杂的重症监护管理期间存活下来。由此,应尽早考虑临时保护性转流结肠造口术,以防止粪便传播并加速需要重症监护且肛周大伤口对局部清创和护理无反应的儿童的伤口愈合。

致谢

感谢所有儿科ICU护理人员为我们重症儿科患者所做的一切努力和支持。

利益冲突声明

作者声明不存在利益冲突。

资金支持

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Emrah Gün*†MD

Fellow, Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine

Tanıl Kendirli †MD

Professor, Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine

Edin Botan †MD

Fellow, Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine

Halil Özdemir †MD

Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Infectious Disease

Ergin Çiftçi †MD

Professor, Department of Pediatric Infectious Disease

Kübra Konca †MD

Fellow, Department of Pediatric Infectious Disease

Meltem Koloğlu †MD

Professor, Department of Pediatric Surgery

Gülnur Göllü †MD

Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Surgery

Özlem Selvi Can †MD

Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Anesthesia

Ercan Tutar †MD

Professor, Department of Pediatric Cardiology

Ahmet Rüçhan Akar †MD

Professor, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery

Heart Centre, Cebeci Hospitals

Erdal İnce †MD

Professor, Department of Pediatric Infectious Disease

* Corresponding author

†Ankara University School of Medicine, Turkey

References

- Morcos B, Amarin R, Abu Sba A, Al-Ramahi R, Abu Alrub Z, Salhab M. Contemporary management of perianal conditions in febrile neutropenic patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39(4):404-7.

- Baker B, Al-Salman M, Daoud F. Management of acute perianal sepsis in neutropenic patients with hematological malignancy. Tech Coloproctol 2014;18(4):327-33.

- Vuille-dit-Bille RN, Berger C, Meuli M, Grotzer MA. Colostomy for perianal sepsis with ecthyma gangrenosum in immunocompromised children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2016;38(1):53-7.

- Bordes J, Le Floch R, Bourdais L, Gamelin A, Lebreton F, Perro G. Perineal burn care: French working group recommendations. Burns 2014;40(4):655-63.

- Bordes J. Response to letter to the editor: perineal burn care: French working group recommendations [Burns 2014;40:655-63]. Burns 2015;41(6):1368-9.

- Ichimiya M, Takita Y, Yamaguchi M, Muto M. Case of purpura fulminans due to septicemia after artificial abortion. J Dermatol 2007;34(11):786-9.

- Bouneb R, Mellouli M, Regaieg H, Majdoub S, Chouchene I, Boussarsar M. Meningococcemia complicated by myocarditis in a 16-year-old young man: a case report. Pan Afr Med J 2018;29:149.

- Simsic JM, Dolan K, Howitz S, Peters S, Gajarski R. Prevention of pressure ulcers in a pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Pediatr Qual Saf 2019;4(3):e162.

- Price CE, Cox S, Rode H. The use of diverting colostomies in paediatric peri-anal burns: experience in 45 patients. S Afr J Surg 2013;51(3):102-5.

- Quarmby CJ, Millar AJ, Rode H. The use of diverting colostomies in paediatric peri-anal burns. Burns 1999;25(7):645-50.