Volume 42 Number 3

WHAM evidence summary: topical turmeric for wound healing

Emily Haesler

Keywords wounds, wound healing, turmeric, curcumin, curcuma longa

For referencing Haesler E. WHAM evidence summary: topical turmeric for wound healing. WCET® Journal 2022;42(3):38-41

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.3.38-41

Clinical question

What is the best available evidence for topically applied turmeric products for promoting healing in wounds?

Summary

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) is a spice harvested in India and other Asian countries that has traditionally been used to treat many ailments, including skin conditions. Although it is recognised as having anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antiseptic effects that are beneficial to the processes of wound healing, to date, the scientific evidence on its use as a topical wound treatment is limited1–3. Level 2 evidence4 suggested turmeric washes are associated with faster healing of postpartum perineal wounds compared with management with oral antibiotic and nutritional supplements. Level 2 evidence5 also suggested that a turmeric-containing herbal oil was as effective as povidone-iodine in achieving improvements in the wound bed (including size and depth). Level 4 evidence6–9 reported use of a turmeric paste to reduce signs and symptoms in fungating wounds7, a novel turmeric-impregnated dressing to heal acute and chronic wounds6, and application of turmeric with a goal of amplifying the benefits of phototherapy for hard-to-heal wounds8,9. All these studies were small and had methodological limitations, providing insufficient support for a graded recommendation.

Clinical practice recommendations

All recommendations should be applied with consideration to the wound, the person, the health professional and the clinical context.

|

There is insufficient evidence on the effectiveness of topically applied turmeric products to make a graded recommendation on their use for promoting healing in wounds. |

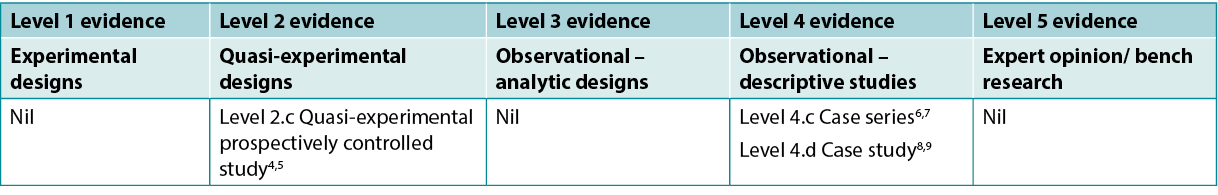

Sources of evidence: search and appraisal

This summary was conducted using methods published by the Joanna Briggs Institute10–12. The summary is based on a systematic literature search combining search terms related to turmeric/curcumin/curcuma longa and wounds/wound healing. Studies reporting turmeric for management of non-wound skin conditions (e.g. psoriasis and dermatitis) were excluded. Searches were conducted in the CINAHL, PubMed® and Hinari databases and in the Cochrane Library for evidence conducted in human wounds published up to April 2022 in English. Levels of evidence for intervention studies are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Levels of evidence for clinical studies

Background

Turmeric (C. longa) is a spice prepared from a rhizome, with curcumin being the active chemical substance3,13. It is described as having anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiseptic and anti-cancer effects1–3. It has been used traditionally to treat skin conditions including psoriasis, redness, erythema and pain and burning from lesions14. Laboratory studies have demonstrated the ability of curcumin to enhance wound healing by inhibiting the production of cytokines and influencing free radical behaviour, thereby reducing oxidative stress and inflammatory responses2,3,13. In animal studies, curcumin has been associated with an increase in fibroblast migration, leading to enhanced granulation tissue formation, as well as increased collagen deposition and neovascularisation. In these ways, curcumin appears to influence wound healing at the inflammatory, proliferation and remodelling stages3,13.

As a traditional treatment for wounds in India and other Asian countries, turmeric is prepared for application as a paste or wash. In Asia it has been marketed as an additive in sticking plaster15. There is an extensive body of animal-based research exploring its use to enhance the performance of wound dressings, including chitosan, alginate, collagen and polymeric experimental products2,3. However, turmeric is observed to have poor water solubility, low penetration of skin, and the active ingredients degrade rapidly, which have thus far limited its commercialisation14.

Clinical Evidence

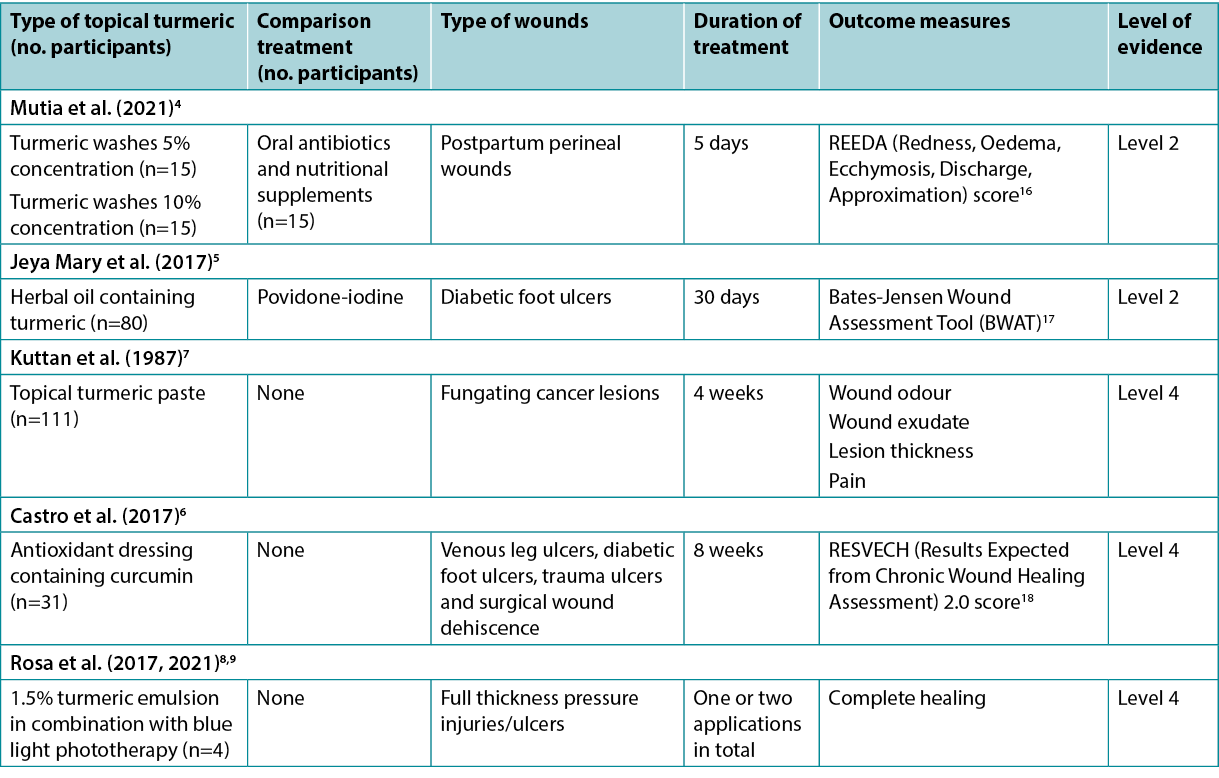

The evidence on turmeric products applied topically to human wounds is summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of the evidence

Topical turmeric washes for promoting wound healing

One quasi-experiment4 at moderate risk of bias reported the use of topical turmeric as a cleansing wash for promoting healing of perineal wounds. Postpartum women with Grade II perineal wounds were assigned to one of three intervention groups (n=15 in each group) – 5% concentration turmeric perineal washes twice daily, 10% concentration turmeric perineal washes twice daily or a control group receiving oral antibiotics and nutritional supplements. The treatment duration was 5 days for all groups. At day 5 and day 7, the turmeric perineal wash groups achieved superior outcomes compared with the control group for measures of perineal healing (redness, oedema, ecchymosis, discharge and approximation using the previously validated REEDA scale). The 5% concentration turmeric wash group had a faster rate of healing on average (5 days postpartum versus 7 days for the 10% concentration turmeric wash group versus >7 days for the control group, p<0.05)4 (Level 2).

Turmeric paste/oil preparations for promoting wound healing

A prospective study5 (n=160) at high risk of bias investigated treatment of diabetic foot ulcers over 30 days. Participants received a povidone-iodine dressing or a herbal oil dressing that contained curcumin, neem and coconut oil (prepared by heating the leaves and oils together and then straining and cooling). Evaluation was conducted at baseline, day 15 and day 30 using the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool (BWAT). Both groups showed statistically significantly better scores on all variables on the BWAT. There was minimal between-group comparison and it was unclear how many ulcers healed during the study,5 but the herbal oil was reported to be cost effective (Level 2).

One case series7 at high risk of bias explored topical application of turmeric paste to fungating cancerous lesions (n=111) of the face, breast, skin and miscellaneous anatomical locations. A 0.5% concentration curcumin paste was applied three times daily and no concomitant therapy was used. After 4 weeks of treatment, 90% of lesions exhibited reduction in malodour, 50% were less painful, 70% had a reduction in exudate, and 10% showed reduction in lesion “thickness”. One participant experienced severe adverse allergic reaction7 (Level 4).

Turmeric wound dressings for promoting wound healing

Despite the literature search identifying a large volume of research exploring experimental wound dressings utilising turmeric, only one study was identified that reported clinical outcomes for a turmeric dressing applied to human wounds. In this case series6, which was at low risk of bias, outcomes were reported for lower limb acute (n=9) and hard-to-heal (n=22) wounds treated with an antioxidant, galactomannan-based matrix dressing containing curcumin [REOXCARE by Histocell, study conducted in Spain] that was applied every 3 days. The wounds were assessed as infection-free at baseline; however, the participants had significant co-morbidities (e.g., diabetes and venous insufficiency). At 8-week follow-up, 32% of the hard-to-heal wounds and 9% of the acute wounds completely healed. Only 52% of participants completed the treatment period, but withdrawals were not related to the wound dressing6 (Level 4).

Topical turmeric in conjunction with light therapy for promoting wound healing

The literature search identified several case studies8,9 at high risk of bias that reported use of topical turmeric with the goal of amplifying the absorption of blue light applied to hard-to-heal wounds. The curcumin-enhanced phototherapy treatment was combined with low level laser therapy and a cellulose dressing. Turmeric is reported to be photosensitive, and in these case studies it was applied as an emulsion across the surface of the wound immediately prior to phototherapy to increase the efficacy of the light therapy. In one case study9 an association between curcumin-enhanced phototherapy and reduction in microorganisms in a Category/Grade 3 pressure injury/ulcer, as well as total healing in 30 days, were reported. In other case studies8 in which the same combination therapy was used, five full thickness pressure injuries/ulcers healed in 20–30 weeks (excepting one that was not healed by 45 weeks of treatment) (Level 4).

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest in accordance with International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) standards.

About wham collaborative evidence summaries

The WHAM Collaborative evidence summaries are consistent with methodology published in Munn, Lockwood and Moola19.

Methods are outlined in resources published by the Joanna Briggs Institute10–12 and on the WHAM Collaborative website: http://WHAMwounds.com. WHAM evidence summaries undergo peer review by an international, multidisciplinary Expert Reference Group. WHAM evidence summaries provide a summary of the best available evidence on specific topics and make suggestions that can be used to inform clinical practice. Evidence contained within this summary should be evaluated by appropriately trained professionals with expertise in wound prevention and management, and the evidence should be considered in the context of the individual, the professional, the clinical setting and other relevant clinical information.

Copyright ©2021 Wound Healing and Management Collaboration, Curtin Health Innovations Research Institute, Curtin University, WA, Australia.

WHAM证据总结:外用姜黄用于伤口愈合

Emily Haesler

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.3.38-41

临床问题

外用姜黄产品促进伤口愈合的最佳可用证据是什么?

总结

姜黄(Turmeric,学名Curcuma longa)是产于印度和其他亚洲国家的一种香料,传统上被用来治疗许多疾病,包括皮肤病。尽管它被认为具有抗炎、抗氧化和抗菌作用,有利于伤口愈合过程,但迄今为止,其用作外用伤口治疗的科学证据有限1–3。2级证据4表明,与口服抗生素和营养补充剂相比,姜黄洗剂与产后会阴伤口的快速愈合有关。2级证据5还表明,含有姜黄的草药油在改善伤口床(包括大小和深度)方面与聚维酮碘同样有效。4级证据6-9报告了使用姜黄糊剂来减少真菌感染伤口7体征和症状,一种用于治疗急性和慢性伤口6的新型姜黄浸渍敷料,以及应用姜黄以扩大光疗对难以愈合伤口的益处8,9。所有这些研究均规模较小,且存在方法学局限性,不足以支持分级建议。

临床实践建议

采用所有建议时,应考虑伤口、患者、专业医护人员和临床环境。

|

尚无足够的证据表明外用姜黄产品的有效性,无法就其用于促进伤口愈合的用途提出分级建议。 |

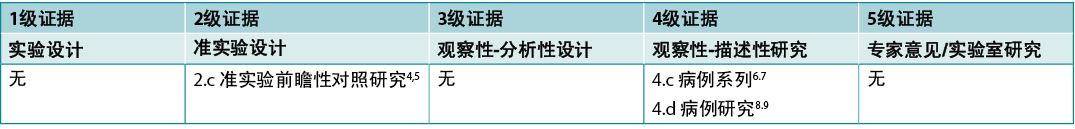

证据来源检索和评价

本总结是采用乔安娜·布里格斯研究所公布的方法进行的10-12。本总结基于系统性文献检索,结合了与姜黄/姜黄素和伤口/伤口愈合相关的检索词。报告姜黄用于治疗非伤口皮肤病(例如银屑病和皮炎)的研究被排除在外。在CINAHL、PubMed®和Hinari数据库和Cochrane 图书馆中检索了截至2022年4月以英文发表的人类伤口证据。干预性研究的证据水平见表1。

表1.临床研究的证据水平

背景

姜黄是一种由根茎制成的香料,姜黄素是活性化学物质3,13。姜黄被描述为具有抗炎、抗氧化、抗菌和抗癌作用1-3。它传统上用于治疗皮肤病,包括银屑病、发红、红斑、病变疼痛和灼痛14。实验室研究证明姜黄素能够通过抑制细胞因子的产生和影响自由基行为来促进伤口愈合,从而减少氧化应激和炎症反应2,3,13。在动物研究中,姜黄素与成纤维细胞迁移増加相关,导致肉芽组织形成増强,以及胶原沉积和新生血管形成増加。通过这些方式,姜黄素似乎在炎症、増殖和重塑阶段影响伤口愈合3,13。

作为印度和其他亚洲国家治疗伤口的传统方法,姜黄制备成糊剂或洗剂使用。在亚洲,姜黄已作为粘性膏药15的添加剂销售。有大量基于动物的研究探索姜黄用于増强伤口敷料的性能,包括壳聚糖、藻酸盐、胶原蛋白和聚合物实验产品2,3。然而,据观察,姜黄的水溶性差,皮肤渗透性低,而且活性成分降解迅速,到目前为止这些因素限制了其商业化14。

临床证据

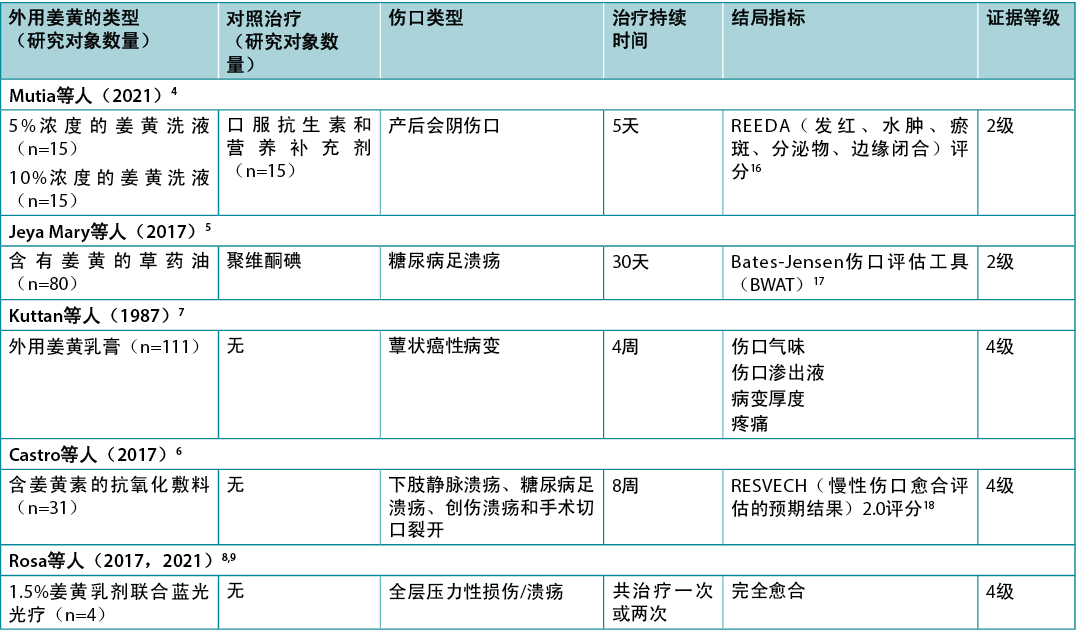

表2总结了将姜黄产品外用于人体伤口的证据。

表2.证据总结

外用姜黄洗剂促进伤口愈合

一项中等偏倚风险的准实验4报告了使用外用姜黄作为清洁洗液促进会阴伤口愈合。将会阴伤口为II级的产后女性分配至三个干预组之一(每组n=15)Å\Å\每日两次使用5%浓度的姜黄会阴洗液、每日两次使用10%浓度的姜黄会阴洗液或接受口服抗生素和营养补充剂的对照组。所有组的治疗持续时间均为5天。在第5天和第7天,与对照组相比,姜黄会阴洗液组在会阴愈合指标(发红、水肿、瘀斑、分泌物和边缘闭合,使用之前经过验证的REEDA量表)方面达到了更好的结局。5%浓度姜黄洗液组的平均愈合速度更快(产后5天,10%浓度姜黄洗液组7天,对照组>7天,p<0.05)4(2级)。

姜黄乳膏/油制剂促进伤口愈合

一项高偏倚风险的前瞻性研究5(n=160)研究了30天内糖尿病足溃疡的治疗。研究对象接受聚维酮碘敷料或含有姜黄素、印楝和椰子油的草药油敷料(通过将叶片和油一起加热,然后过滤冷却来制备)。在基线、第15天和第30天使用Bates-Jensen伤口评估工具(BWAT)进行评估。两组在BWAT的所有变量上均显示出统计学上显著更好的评分。组间比较极少,尚不清楚研究期间有多少溃疡愈合,5但报告草药油具有成本效益(2级)。

一个高偏倚风险的病例系列7探讨了将姜黄乳膏局部应用于面部、乳房、皮肤和其他解剖位置的蕈状癌性病变(n=111)。每日三次使用0.5%浓度的姜黄素糊剂,未使用伴随治疗。治疗4周后,90%的病变显示恶臭减轻,50%疼痛减轻,70%渗出液减少,10%显示病变“厚度”减少。一名研究对象出现了严重的不良过敏反应7(4级)。

姜黄伤口敷料促进伤口愈合

尽管通过文献检索,发现大量探讨使用姜黄的实验性伤口敷料的研究,但仅发现一项研究报告了姜黄敷料用于人体伤口的临床结局。在这个低偏倚风险的病例系列6中,报告了每3天一次使用含有姜黄素的抗氧化剂、半乳甘露聚糖基质敷料[Histocell公司的REOXCARE,在西班牙进行的研究]治疗下肢急性(n=9)和难以愈合(n=22)伤口的结局。在基线时,伤口被评估为无感染;但是,研究对象患有严重共病

(例如,糖尿病和静脉功能不全)。在8周的随访中,32%的难以愈合伤口和9%的急性伤口完全愈合。只有52%的研究对象完成了治疗期,但退出与伤口敷料无关6(4级)。

外用姜黄配合光疗促进伤口愈合

通过文献检索,发现了几项高偏倚风险的案例研究8,9,这些案例研究报告了使用外用姜黄的目的是増强对应用于难以愈合的伤口的蓝光的吸收。姜黄素増强的光疗治疗与低水平激光治疗和纤维素敷料相结合。据报告,姜黄具有光敏性,在这些案例研究中,在光疗前立即将其作为乳剂涂抹在伤口表面,以提高光疗的效果。在一项病例研究中9,报告了姜黄素増强光疗与三类/三级压力性损伤/溃疡中微生物减少以及30天内完全愈合之间的关系。在其他使用相同组合疗法的案例研究8中,5例全层压力性损伤/溃疡在20-30周内愈合(除了一例治疗45周时未愈合)(4级)。

利益冲突

根据国际医学期刊编辑委员会(ICMJE)的标准,作者声明无利益冲突。

关于WHAM的协作证据总结

WHAM的协作证据总结与Munn、Lockwood和Moola19发表的方法一致。

Joanna Briggs Institute10-12和WHAM合作网站(http://WHAMwounds.com)发布的资源列出了这些方法。WHAM证据总结经过国际多学科专家参考小组的同行评审。WHAM证据总结提供了关于特定主题的最佳可用证据的总结,并提出了可用于指导临床实践的建议。本总结中包含的证据应由经过适当培训的具有伤口预防和管理专业知识的专业人士进行评价,并应根据个人、专业人士、临床环境以及其他相关临床信息考虑证据。

版权所有˝2021澳大利亚西澳州科廷大学科廷健康创新研究所伤口愈合与管理协作组织

Author(s)

Emily Haesler

PhD Post Grad Dip Adv Nurs (Gerontics) BNurs Fellow Wounds Australia

Adjunct Professor Wound Healing and Management Collaborative, Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute, Curtin University, WA

References

- Maheshwari RK, Singh AK, Gaddipati J, Srimal RC. Multiple biological activities of curcumin: a short review. Life Sci (1973) 2006;78(18):2081–7.

- Ahangari N, Kargozar S, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Baino F, Pasdar A, Sahebkar A, Ferns GAA, Kim HW, Mozafari M. Curcumin in tissue engineering: a traditional remedy for modern medicine. Biofactor 2019;45(2):135–51.

- Mohanty C, Sahoo SK. Curcumin and its topical formulations for wound healing applications. Drug Discov Today 2017;22(10):1582–92.

- Mutia WON, Usman AN, Jaqin N, Prihantono, Rahman L, Ahmad M. Potency of complemeter therapy to the healing process of perineal wound; turmeric (Curcuma longa Linn) Infusa. Gaceta Sanitaria 2021;35 Suppl 2:S322-S6.

- Jeya Mary A, Vaithiyanathan R, Vijayaragavan R. Effectiveness of conventional and herbal treatment on diabetic foot ulcer using Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool. Int J Nurs Ed 2017;9(4):53–7.

- Castro B, Bastida FD, Segovia T, Lopez Casanova P, Soldevilla JJ, Verdu-Soriano J. The use of an antioxidant dressing on hard-to-heal wounds: a multicentre, prospective case series. J Wound Care 2017;26(12):742–50.

- Kuttan R, Sudheeran PC, Josph CD. Turmeric and curcumin as topical agents in cancer therapy. Tumori J 1987;73(1):29–31.

- Rosa LP, Silva FCD, Luz SCL, Vieira RL, Tanajura BR, Silva Gusmão AGD, de Oliveira JM, Jesus Nascimento F, Dos Santos NAC, Inada NM, Blanco KC, Carbinatto FM, Bagnato VS. Follow-up of pressure ulcer treatment with photodynamic therapy, low level laser therapy and cellulose membrane. J Wound Care 2021;30(4):304–10.

- Rosa LP, da Silva FC, Vieira RL, Tanajura BR, da Silva Gusmao AG, de Oliveira JM, Dos Santos NAC, Bagnato VS. Application of photodynamic therapy, laser therapy, and a cellulose membrane for calcaneal pressure ulcer treatment in a diabetic patient: a case report. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2017;19:235–8.

- Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual; 2017. Available from: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/The Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. New JBI grades of recommendation. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2013.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. Supporting document for the Joanna Briggs Institute levels of evidence and grades of recommendation. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014. Available from: www.joannabriggs.org

- Akbik D, Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci (1973) 2014;116(1):1–7.

- Barbalho SM, de Sousa Gonzaga HF, de Souza GA, de Alvares Goulart R, de Sousa Gonzaga ML, de Alvarez Rezende B. Dermatological effects of Curcuma species: a systematic review. Clin Exp Dermatol 2021;46(5):825–33.

- Marketing Practice. Band-aid: continuous care; 2006 Nov 28. Available from: http://marketingpractice.blogspot.com.au/2006/11/band-aid-brand-becoming-generic.html

- Alvarenga MB, Francisco AA, de Oliveira SMJV, da Silva FMB, Shimoda GT, Damiani LP. Episiotomy healing assessment: Redness, Oedema, Ecchymosis, Discharge, Approximation (REEDA) scale reliability. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2015;23(1):162–8.

- Bates-Jensen BM, McCreath HE, Harputlu D, Patlan A. Reliability of the Bates-Jensen wound assessment tool for pressure injury assessment: the pressure ulcer detection study. Wound Repair Regen 2019;27(4):386–95.

- Domingues EAR, Carvalho MRF, Kaizer UAO. Cross-cultural adaptation of a wound assessment instrument. Cogitare Enferm 2018;23(3):e54927.

- Munn Z, Lockwood C, Moola S. The development and use of evidence summaries for point of care information systems: a streamlined rapid review approach. Worldview Evid Based Nurs 2015;12(3):131–8.