Volume 42 Number 4

A risk factor model for peristomal skin complications

Anne Steen Hansen, Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft, Lina Martins, Jane Fellows, Birgitte Dissing Andersen, Gillian Down, Tonny Karlsmark, Gregor Jemec, David Voegeli, Zenia Størling and Lene Feldskov Nielsen

Keywords peristomal skin complications, ostomy care, leakage, risk factor model

For referencing Hansen AS et al. A risk factor model for peristomal skin complications. WCET® Journal 2022;42(4):14-30

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.4.14-30

Submitted 2 September 2022

Accepted 23 November 2022

Abstract

For people living with an ostomy, leakage and peristomal skin complications (PSC) are common issues that often appear together. Better means of preventing these issues could improve the quality of life of these patients. The purpose of the research presented here was to identify and build a model of risk factors for PSC.

Risk factors were identified via discussion sessions with Coloplast’s internal ostomy care experts, the Coloplast Skin Expert Panel, the Global Coloplast Ostomy Forum (COF), and 18 national COF boards, collectively representing more than 400 ostomy care nurses from around the world. Risk factors were identified by these expert groups, analysed, clustered into categories, and discussed in several stages, resulting in the risk factor model for PSC, comprising three overall categories and their related risk factors (n=24). Consensus on the model was achieved using a modified Delphi process involving over 4000 experts within ostomy care from 35 countries. In parallel, a systematic literature review of risk factors for PSC was performed to identify primary literature supporting the model. Relevant articles published from 2000 until August 2020 were included in the review, and 58 articles were found to support 19 out of the total 24 risk factors. The risk factor model for PSC was ratified by the Coloplast Skin Expert Panel and the Global COF and holds potential to be included in guidelines for healthcare professionals and to be used as a tool in daily clinical practice.

Introduction

For people living with an ostomy, the risk of leakage and peristomal skin complications (PSC) are typical concerns. It has been estimated that 91% of people living with an ostomy worry about leakage and 76–77% have experienced leakage within the last 6 months1,2. Worrying about leakage may challenge everyday activities and social interactions; further, leakage is a major contributor for developing PSC.

In one study, four main diagnoses (faeces-induced erosion, maceration, erythema and contact dermatitis) accounted for 77% of all ostomy-related diagnoses, and these were all related to contact with ostomy effluent3. When the integrity of the skin is damaged, adherence between the skin and the ostomy product is challenged, potentially leading to further leakage4. As a result, pain, anxiety and a loss of confidence in the ostomy product may occur, leading to a risk of less participation in social activities and a negative impact on the individual’s quality of life1.

Lack of awareness of PSC seems to be common. A study reported that less than half (43%) of the individuals with PSC were aware of the problem4. Improving awareness of risks factors that may lead to leakage and PSC among people living with an ostomy has a great potential to help preventing PSC.

Several factors in addition to those inherent to ostomy products may predispose people living with an ostomy to PSC4,5. Some of these risk factors can be addressed at routine visits to the clinic to increase awareness in people living with an ostomy and initiate mitigating actions as part of a prevention strategy against PSC. Identification of these risk factors may also give rise to new interventions for preventing leakage and PSC in people living with an ostomy.

The concept of a consensus-based PSC risk factor model was identified as a potential solution to increasing the awareness of which risk factors can be intervened upon to prevent the development of PSC. The purpose of the research presented here was to develop consensus on the most important risk factors for PSC and incorporate them in a risk factor model, while simultaneously identifying evidence and gaps in the literature pertaining to these risk factors. The aim is to guide practice in ostomy care and support healthcare professionals and people living with an ostomy in the prevention of PSC. We hypothesised that the development process of a comprehensive PSC risk factor model to support daily practice in preventing PSC will highlight a gap of good or high quality evidence from the literature to support the model.

Methods

Development of the risk factor model

The risk factor model for PSC was developed in collaboration with the Coloplast Skin Expert Panel (consisting of seven experts in the field of dermatology, wounds and ostomy care), the Global Coloplast Ostomy Forum (Global COF), an exclusive entity consisting of 13 internationally recognised experts, and the national COF boards. The national COF boards represent more than 400 ostomy care nurses from around the world, including Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America.

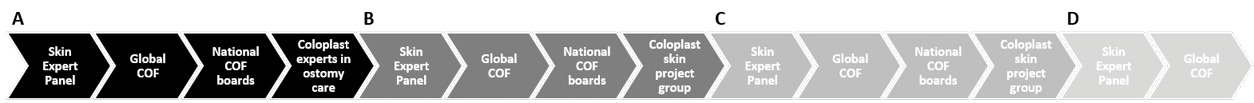

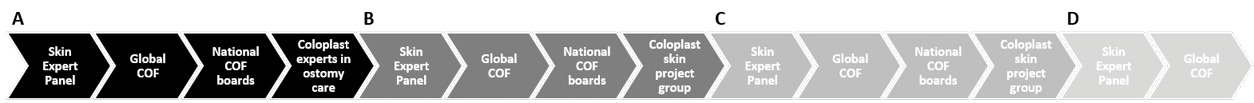

The development of the risk factor model for PSC was a multistep process with four main stages, namely scoping, exploring, convergence and ratification (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Method for development of the risk factor model for PSC.

A. Step 1: Scoping stage. Meetings were held to brainstorm on risk factors for PSC with the Skin Expert Panel, Global COF, national COF boards and internally in Coloplast with experts in ostomy care from R&D and Marketing. Discussions with the Skin Expert Panel and Global COF based on a scoping literature review guided the further process Steps 2 and 3.

B. Step 2: Exploring stage. After all the data gathered in Step 1 had been grouped into 10 themes by the internal Coloplast skin project group, the Skin Expert Panel, Global COF, and national COF boards condensed the 10 themes even further, resulting in three overall categories to be outlined by the Coloplast skin project group.

C. Step 3: Convergence stage. The three categories were presented to the Expert Skin Panel and Global COF before discussions in the national COF boards aimed to align the content and name the three categories, and the Coloplast internal skin group adjusted the three categories to a final draft. In parallel, a systematic literature review was performed to support discussions and consensus building. The Skin Expert Panel and Global COF agreed to the final draft before an international consensus process resulted in the final version.

D. Step 4: Ratification stage. The final risk factor model for PSC was ratified by the Expert Skin Panel and the Global COF.

In Step 1 (the scoping stage), an initial meeting was held with the Skin Expert Panel to brainstorm risk factors for PSC. The panel members individually made suggestions for risk factors; further discussions within the panel helped identify additional risk factors and risk factor categories. This process was repeated with the Global COF, the national COF boards, and internally at Coloplast with ostomy care experts from the Research and Development (R&D) and Marketing departments. In parallel, a literature search on PSC risk factors was conducted. The results of this search were shared with the Skin Expert Panel and the Global COF to guide the next steps.

In Step 2 (the exploring stage), an internal Coloplast skin project group categorised all data gathered from the different expert panels in the scoping phase into themes. These themes, with interlinked risk factors, were presented to the Skin Expert Panel, Global COF, and the national COF boards, and they were each tasked with further condensing these themes into overall risk factor categories.

In Step 3 (the convergence stage), the overall risk factor categories were presented to the Skin Expert Panel and the Global COF before discussion sessions were held within the national COF boards to align the content and nomenclature of these categories. The Coloplast internal skin project group updated the categories based on the input from the national COF boards and prepared a final draft. Agreement on this draft was obtained from the Skin Expert Panel and the Global COF before an international consensus process was conducted, resulting in the final version of the risk factor model6,7. The consensus process is described in detail in a separate publication7. Briefly, using a modified Delphi process, consensus was reached among ostomy care specialists across 35 countries. This stage was supported by a systematic literature review (see description below) to identify the level of evidence behind each identified risk factor. In Step 4 (the ratification stage), the final risk factor model was ratified by the Skin Expert Panel and the Global COF7.

Literature review

A systematic review was performed during the convergence stage to support the discussions and consensus building and ascertain the level of evidence behind the identified risk factors. The literature search was performed by an information specialist using the PubMed (including Medline), Derwent World Patents Index, and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) databases. The searches were performed on 19 June 2020 (PubMed and Derwent) and 19 August 2020 (CINAHL).

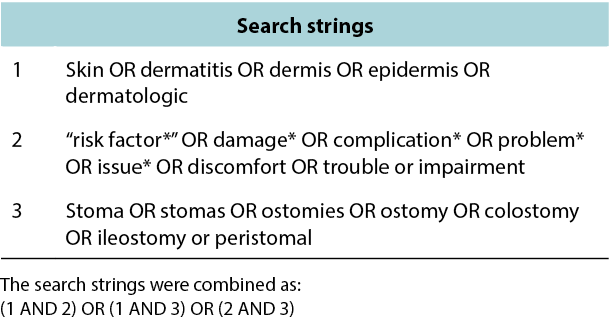

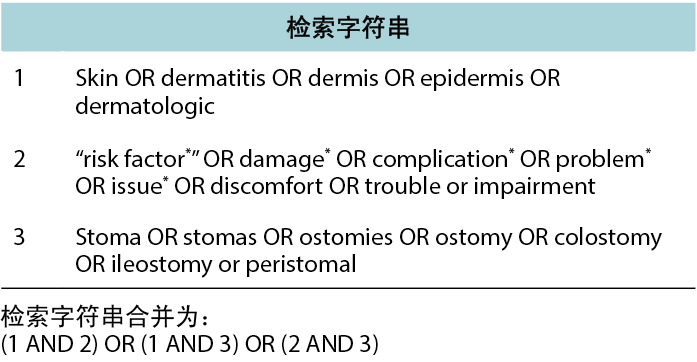

The search timeline was restricted to articles published between 2000 and 2020 (August). The time interval was chosen based on receiving relevant published literature; 10 years was considered a too limited time interval to receive an optimal amount of relevant literature within ostomy care. The search was made sufficiently broad by searching for text words related to skin descriptors and combining these with skin issue and ostomy synonyms. Furthermore, search terms were mapped to the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in Medline: skin, dermatitis, dermis, epidermis, dermatologic agents, ostomy, colostomy and ileostomy. The search strings generated were combined with Boolean operators (AND, OR) to arrive at the final results (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Method for the literature search: search strings.

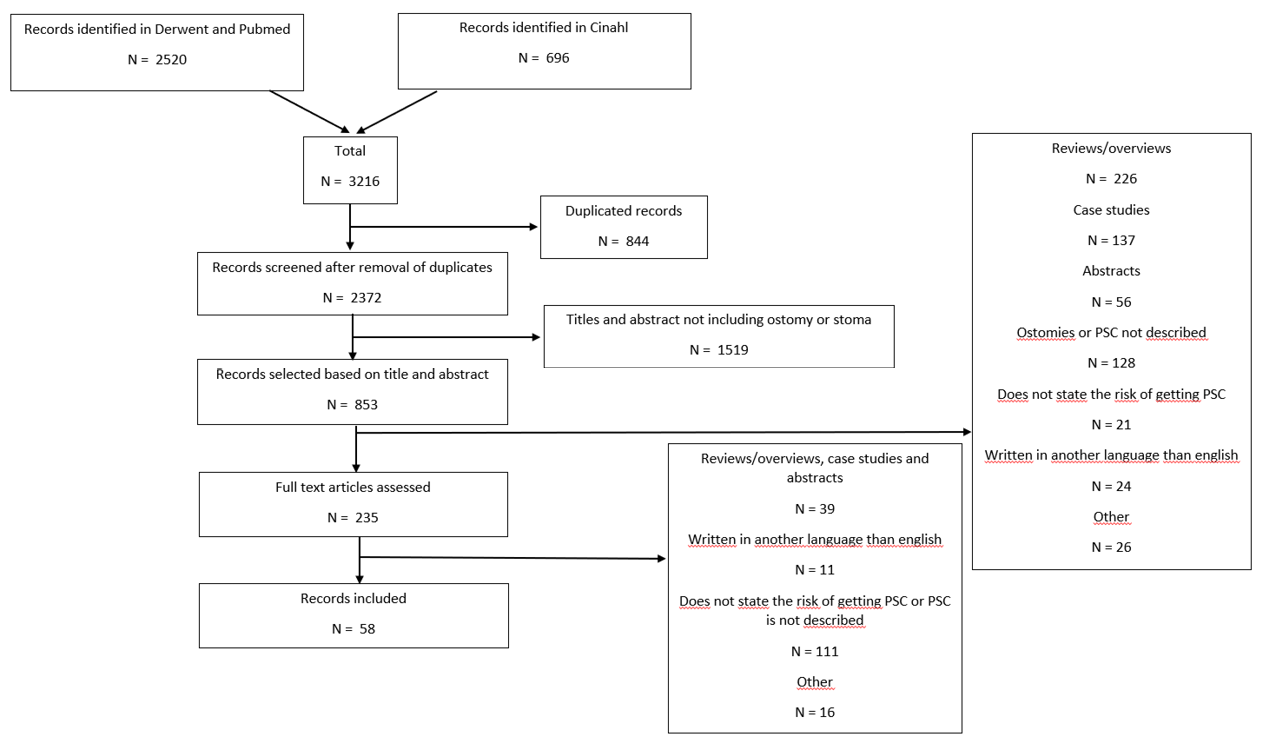

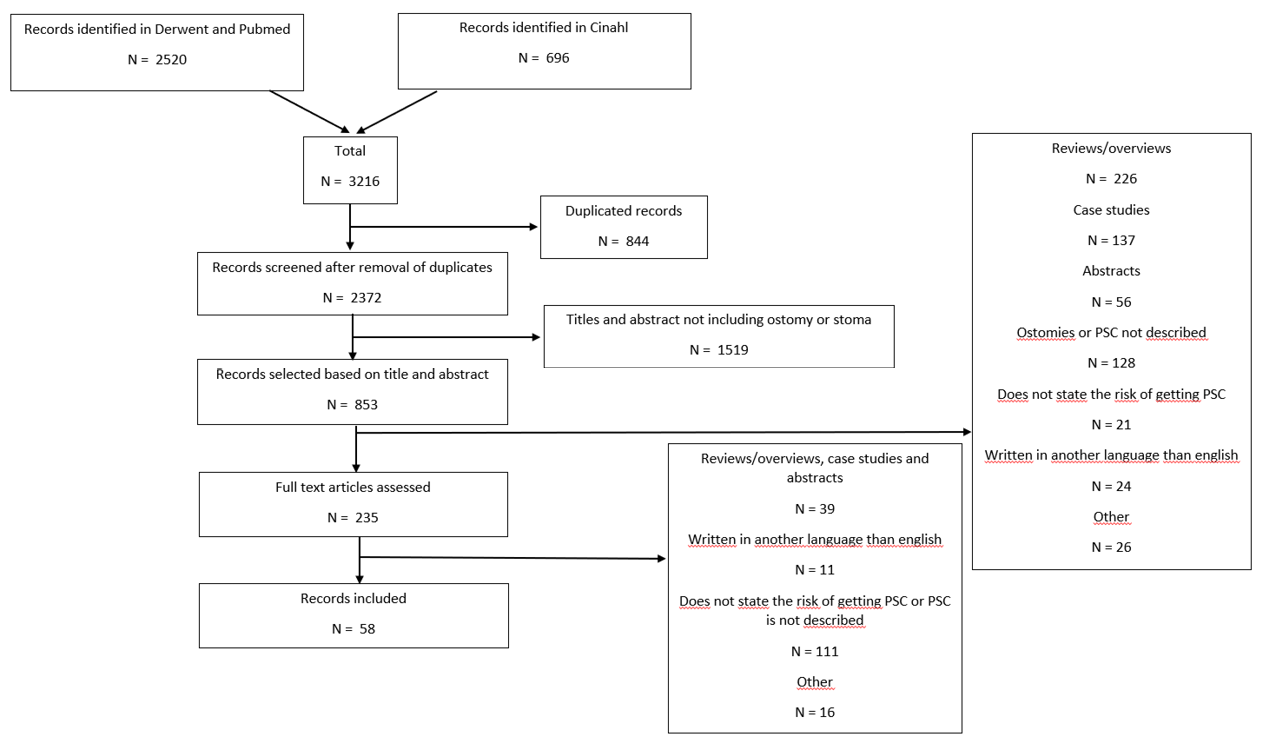

The study selection process is depicted via a PRISMA flow chart in Figure 3. Duplicates were identified manually based on titles and abstracts. These were removed, and thereafter the remaining references were independently screened by two authors based on titles and abstracts. The title or abstract would include words related to ostomy/stoma and problems or PSC to be included. The two independent screenings were compared, and a list of articles made based on the agreed selection. If there was doubt about the relevance of an article, a third author was consulted. The selected articles were evaluated based on exclusion criteria such as reviews, overviews, case studies/case series with less than 10 subjects, opinion pieces, editorials, conference abstracts, and book chapters; the aim was to find published primary literature providing clinical evidence to support the risk factor model. Articles written in languages other than English were also excluded. Thereafter, the full-text versions of the remaining articles were read and studies included if evidence for the identified PSC risk factors were described and both reviewers agreed on the inclusion. Lastly, the evidence quality of the selected articles was evaluated using a 3‑point scale adapted from John Hopkins evidenced-based practice methodology8. The selected articles found to support the risk factor model were consolidated and approved by the Coloplast skin expert panel and the Global COF.

Figure 3. Method for the literature search: PRISMA flowchart

Results

Risk factor categories from the risk factor model

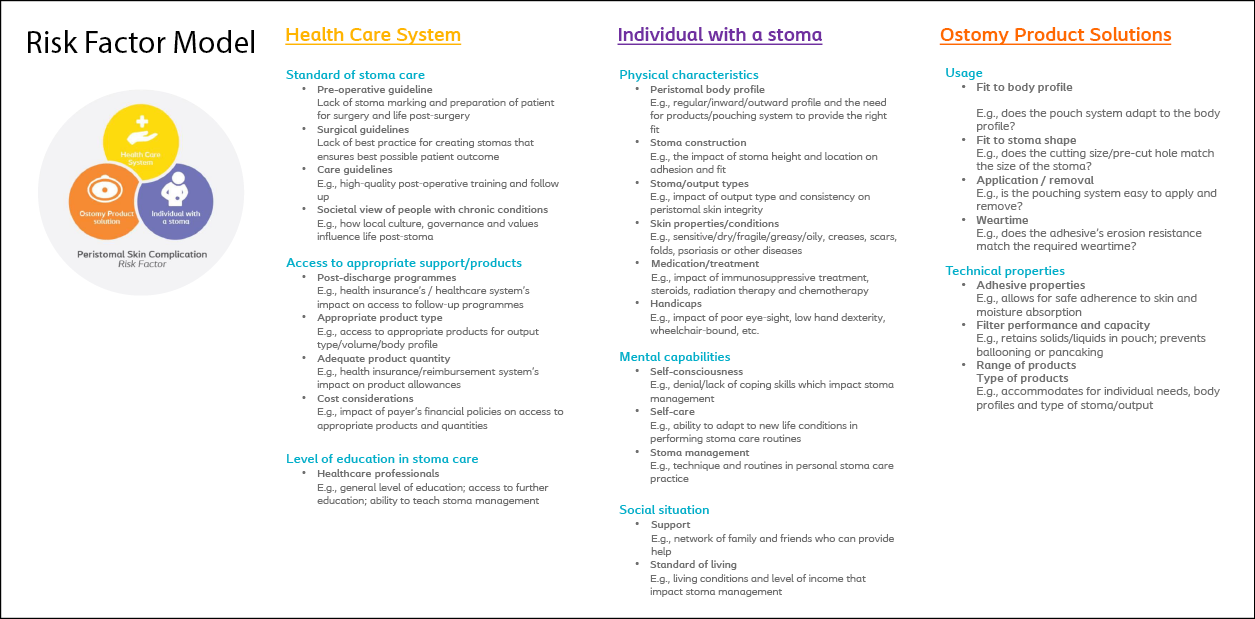

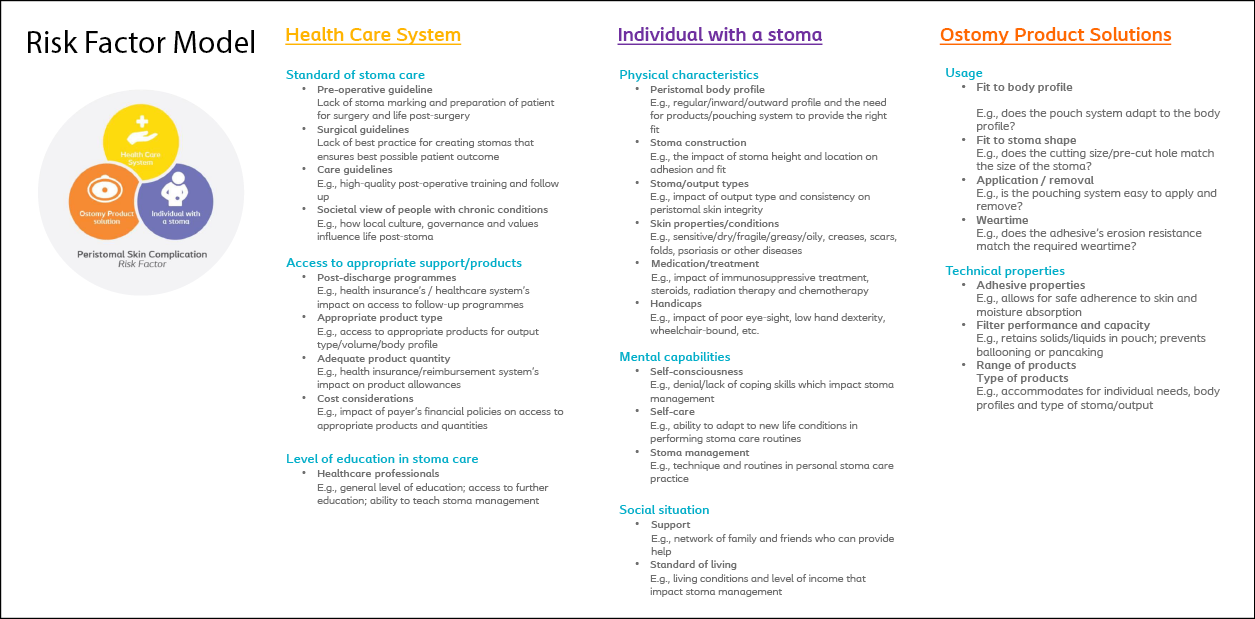

In Step 1 (the scoping stage) of the PSC risk factor model development, more than 100 risk factors were identified. In Step 2 (the exploring stage), these were condensed into 10 ensuing themes: skin-related; user characteristics; resources; environment; mental compliance and adaption; stoma and body profiles; output properties; product usage, compliance, and routines; product performance; and training and education. These 10 themes with interlinked risk factors were condensed further with the help of the expert panels (the Skin Expert Panel, Global COF and the national COF boards) resulting in three suggestions for the overall risk factor categories – Healthcare system, Individual with an ostomy, and Ostomy product (Figure 4).

In Step 3 (the convergence stage), the content and nomenclature of the three categories were refined further, resulting in 24 risk factor subcategories (Figure 4). In Step 4 (the ratification stage), these risk categories and subcategories were ratified by the Skin Expert Panel and the Global COF to constitute the final risk factor model.

Figure 4. The risk factor model for PSC

Literature search results

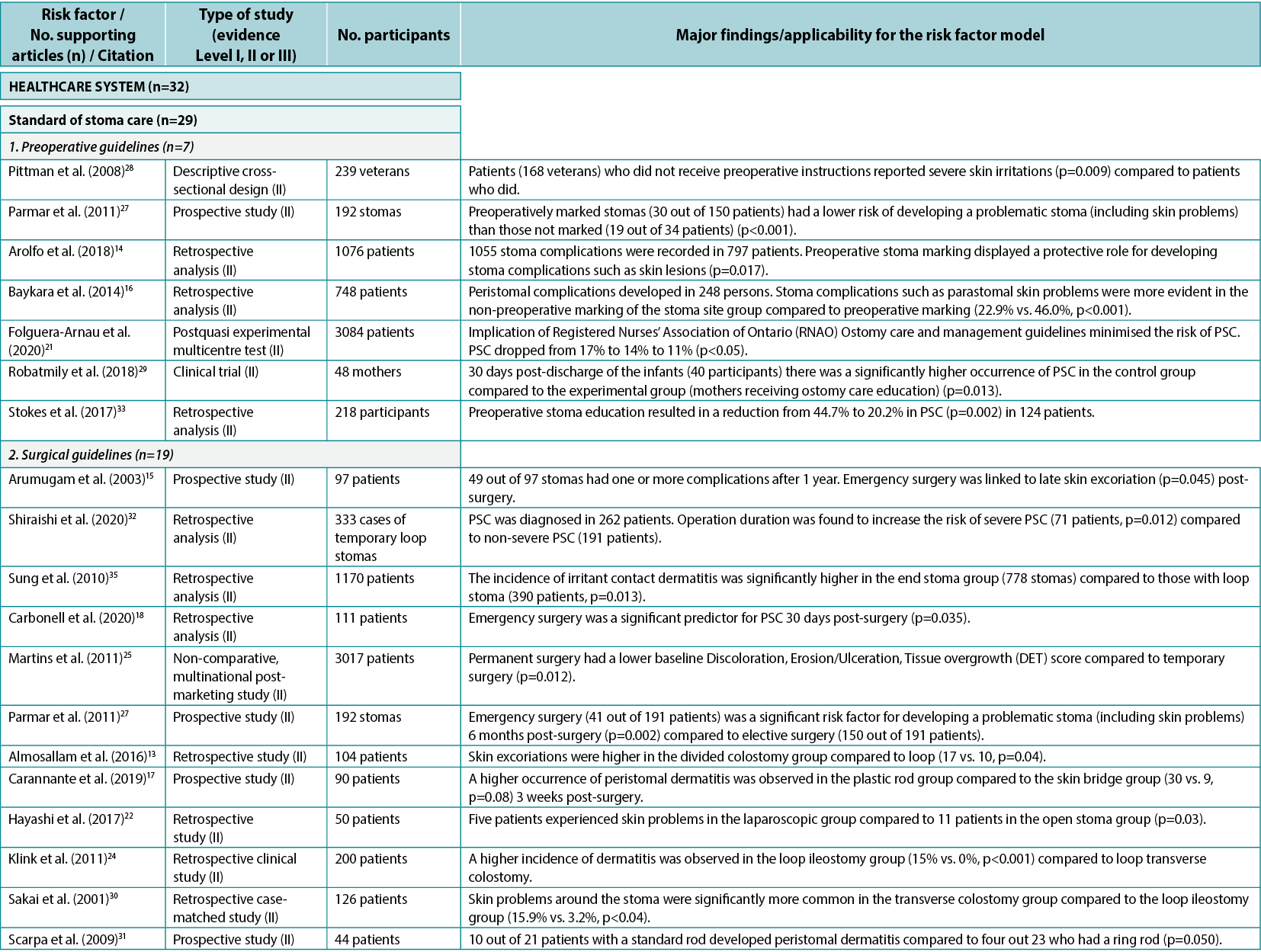

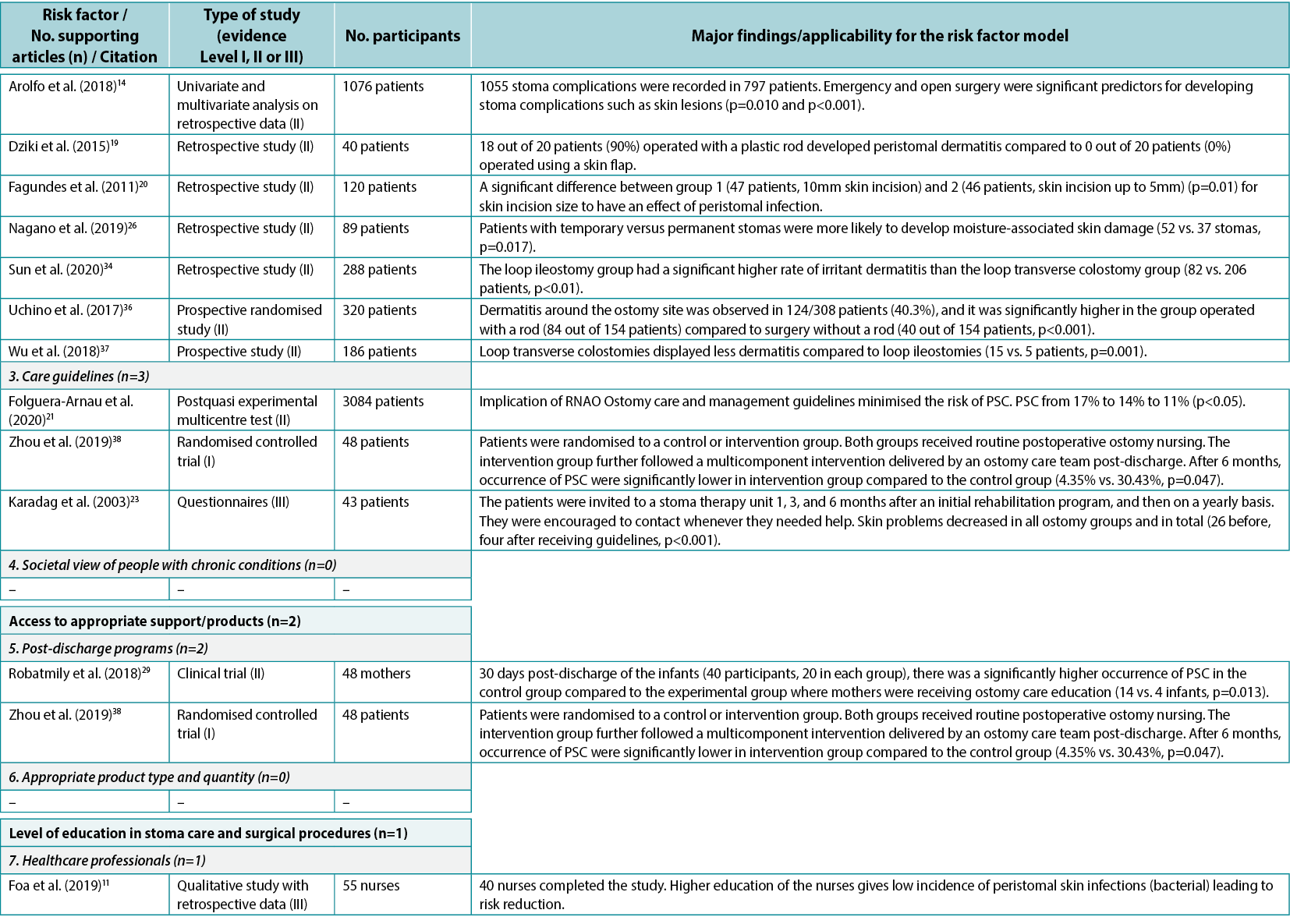

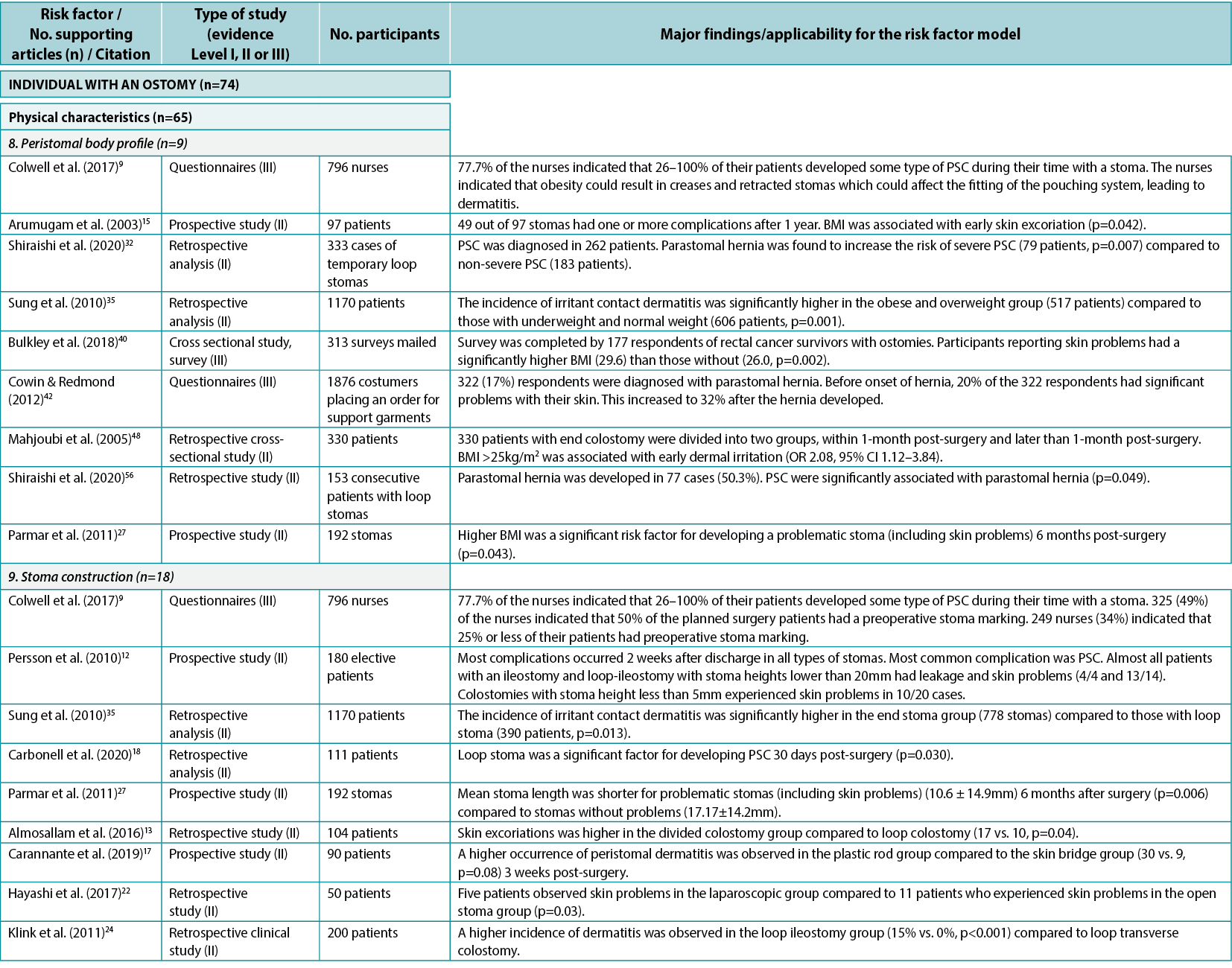

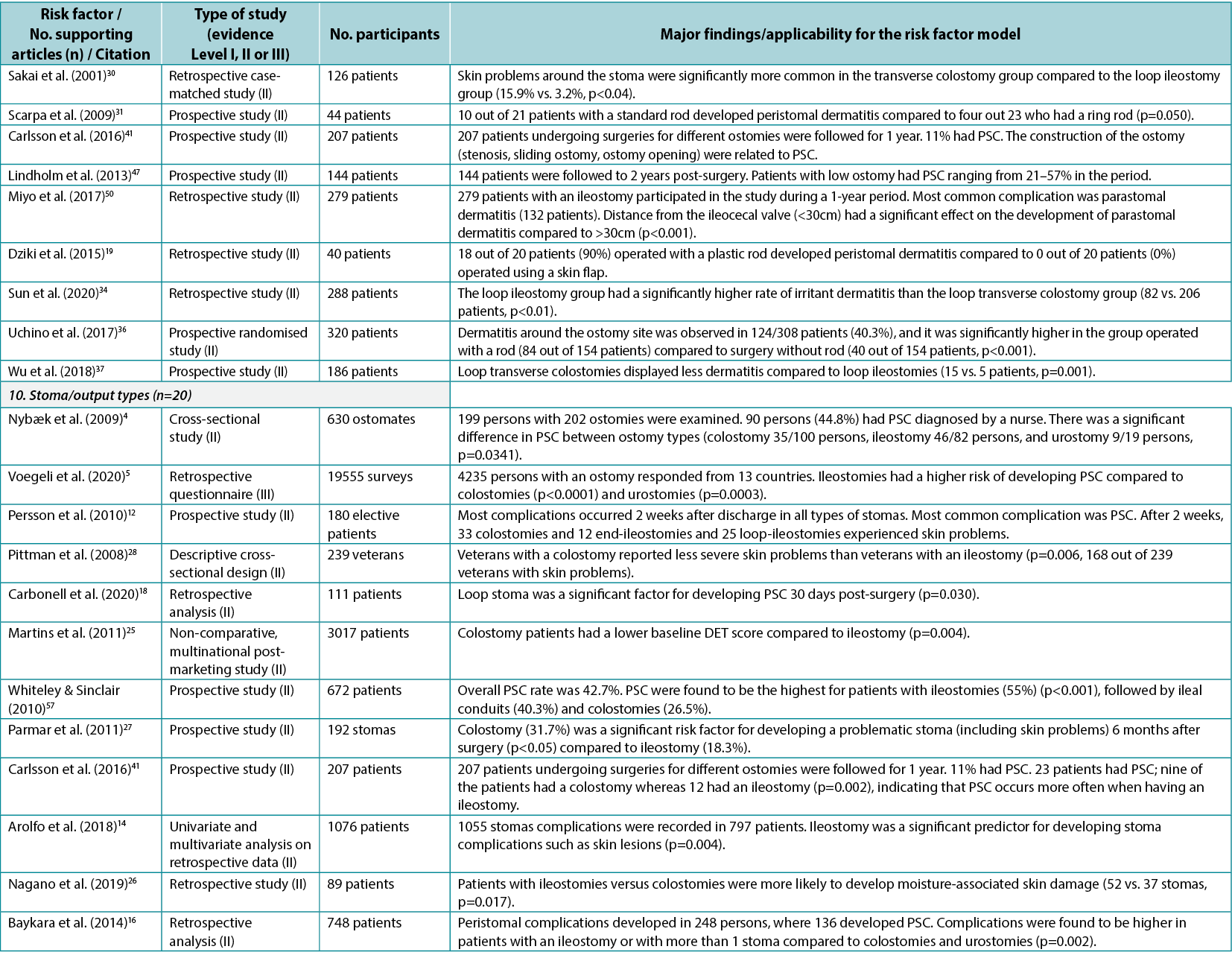

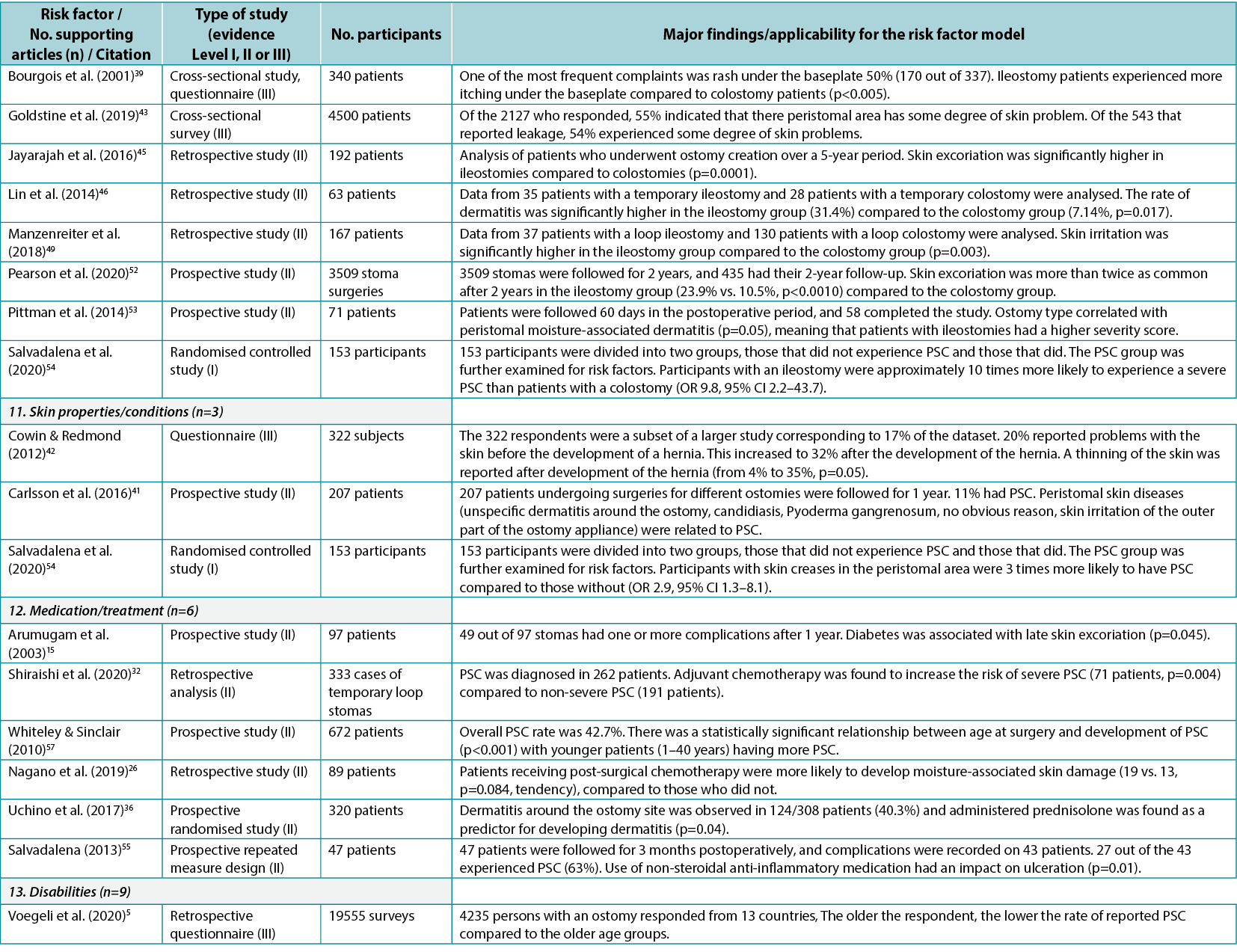

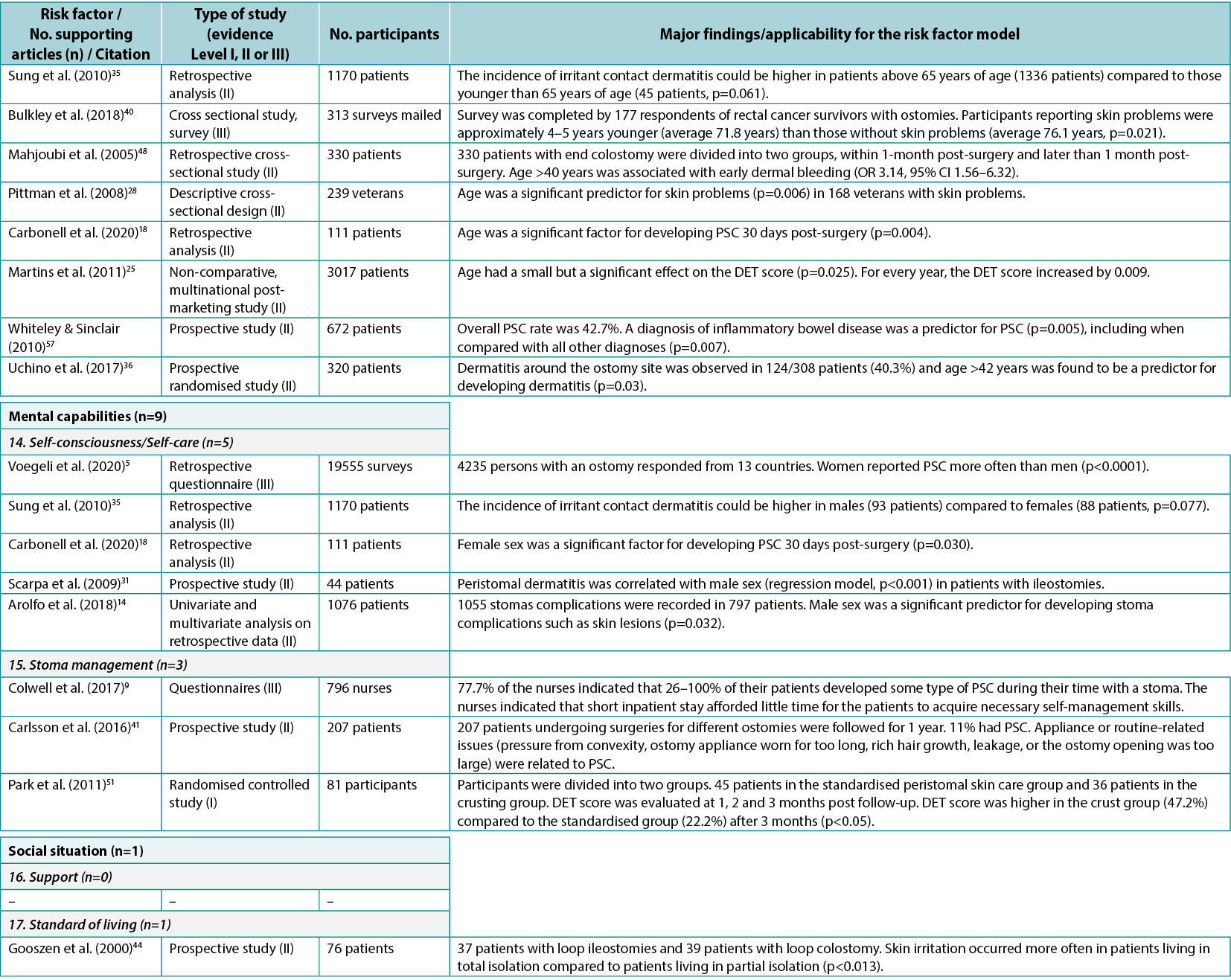

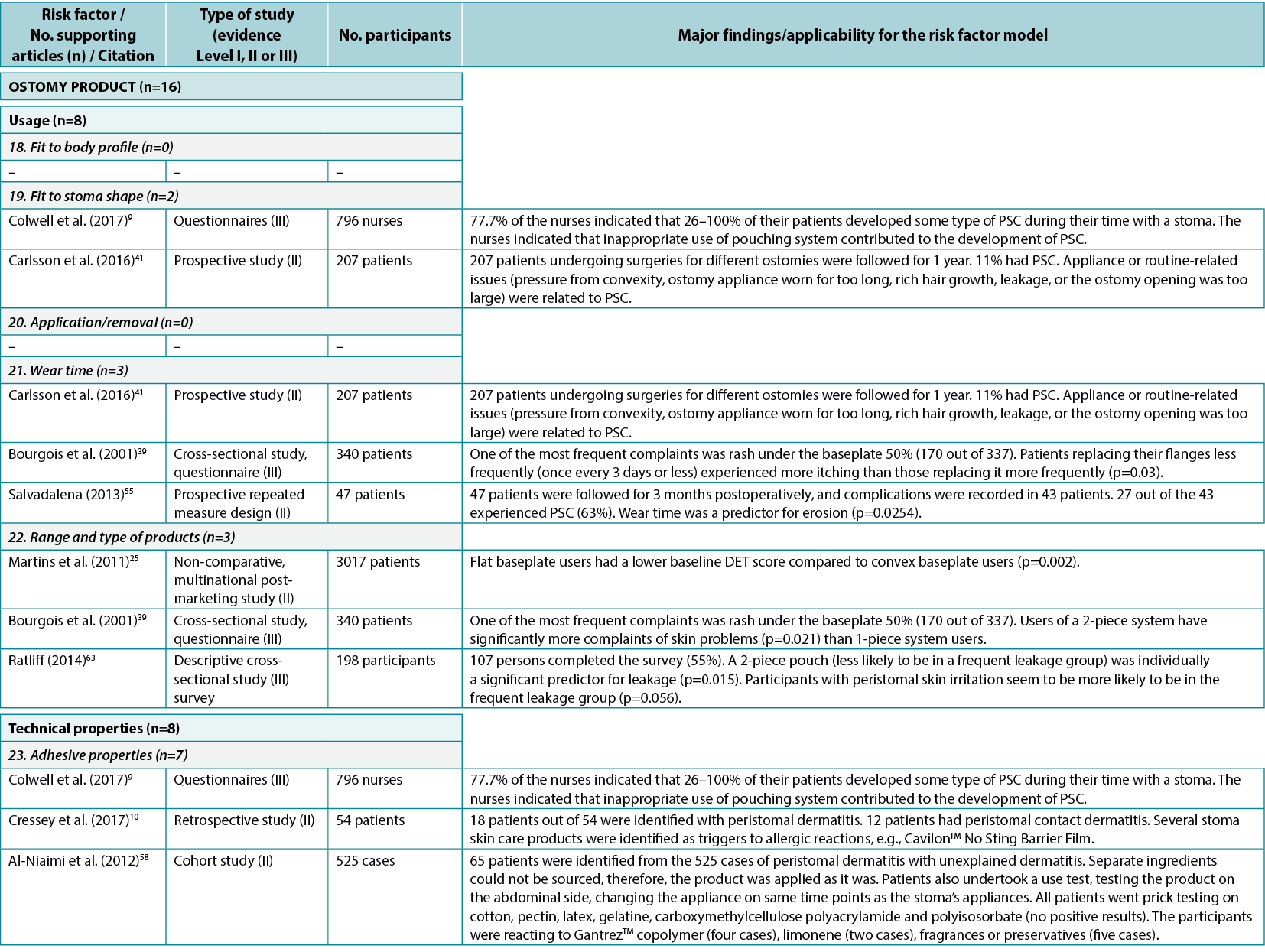

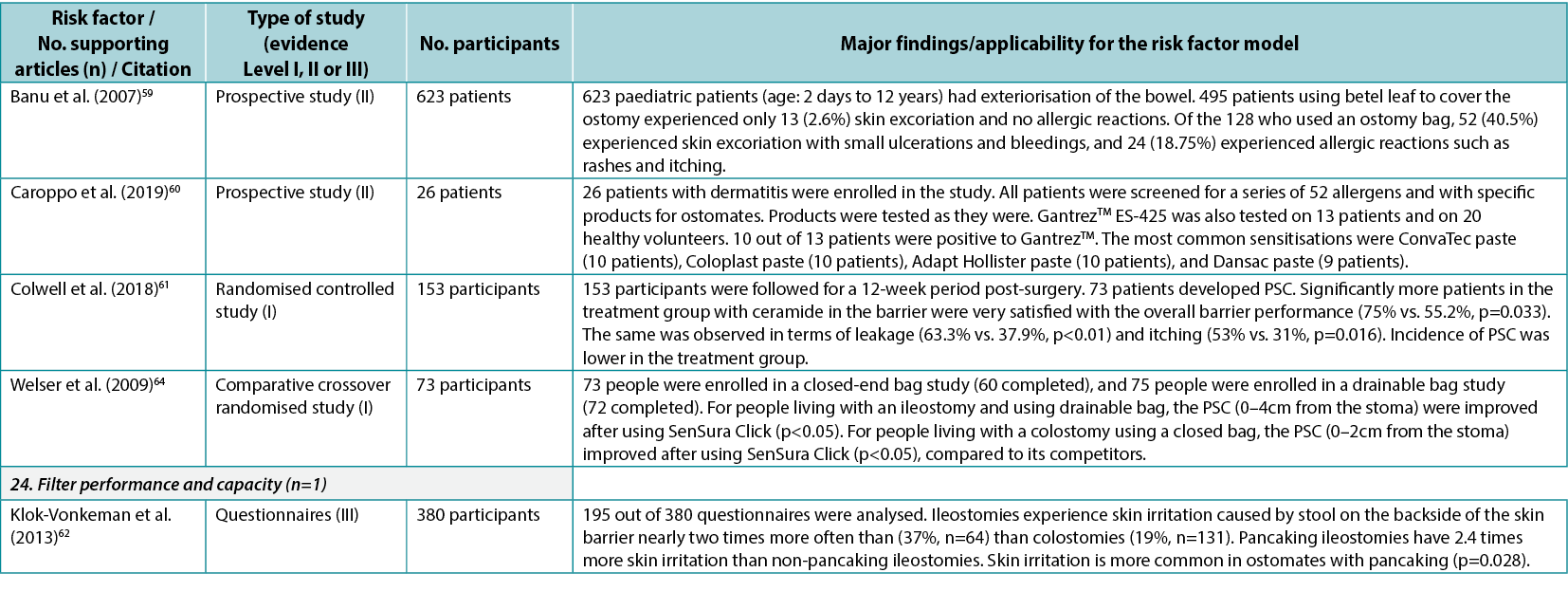

Based on the combined searches, 3216 references were found (Figure 3). After removing 844 duplicates, 2372 articles were screened by title and abstract, and 235 read and screened for the final selection. It was not possible to retrieve four articles; they were therefore excluded. Four articles9–12 did not display any statistics but were included because of their relatively large sample sizes, ranging from 18–796 subjects. In total, 58 articles were included in the review, supporting 19 of the 24 risk factor subcategories identified. Of the included articles, 27 were found to fit into the Healthcare system category11,13–38 (with 32 citations within this category), 43 into the Individual with an ostomy category4,5,9,12–19,22,24–28,30–32,34–37,39–57 (74 citations), and 13 into the Ostomy product category9,10,25,39,41,55,58–64 (16 citations); several articles were found to fit into two or more categories or subcategories. The articles were divided into three evidence levels8: Level I (high), five articles38,51,54,61,64; Level II (good), 43 articles4,10,12–22,24–37,41,44–50,52,53,55–60; and Level III (low), 10 articles5,9,11,39,40,42,43,62,63. A list of the individual studies supporting each identified risk factor within each risk factor category is available in Appendix 1.

Risk factor categories

Healthcare system

The Healthcare system category included seven system level PSC risk factors related to contact, guidance and input from the healthcare system (Figure 4). In the literature review, 27 articles11,13–38 (one Level I38, 24 Level II13–22,24–37, two Level III11,23), with 32 within-category citations, were found supporting five of these seven risk factors (Appendix 1).

Among the individual risk factors in this category, preoperative guidelines include guidance on preparing the patient for the surgical procedure, marking the spot for the ostomy, and advising the patient on life with an ostomy post-surgery; seven articles14,16,21,27–29,33 (all Level II) were found to support the importance of preoperative ostomy site marking as a risk factor for developing PSC.

Surgical guidelines include best practices for creating ostomies for the best possible patient outcome; 19 articles13–15,17–20,22,24–27,30–32,34–37 (all Level II) were found providing clinical evidence for surgical techniques and indicating the importance of selecting a surgical procedure that reduces the risk of getting PSC. Care guidelines include high quality postoperative training and follow‑up; three articles21,23,38 (Level I, II and III: one each) were found pertaining to guidelines for ensuring the quality of postoperative training of the patients. Post-discharge programs include whether health insurances and healthcare systems provide access to follow-up programs; two clinical trials29,38 (Level I and II: one each) were found to provide evidence on the importance of adequate access to post-discharge programs and demonstrated that support from healthcare professionals post-discharge as well as pre‑surgical education of the patient decreased the risk of developing PSC.

Healthcare professionals as a risk factor subcategory include the general level of education, access to further education, and the type of care and surgical procedures undertaken; one qualitative study11 (Level III) discussed the importance of the level of education of healthcare professionals to provide optimal support to the patient. Other risk factors in this category were access to appropriate ostomy product types and quantity to cover any needs, and societal view of people with chronic conditions; no supporting evidence was found for these subcategories.

Individual with a stoma

In this category, a total of 10 individual level risk factors for PSC were identified (Figure 4). The literature review identified 43 articles4,5,9,12–19,22,24–28,30–32,34–37,39–57 (two Level I51,54, 35 Level II4,12–19,22,24–28,30–32,34–37,41,44–50,52,53,55–57, six Level III5,9,39,40,42,43), cited 74 times, supporting nine of these 10 risk factors (Appendix 1). One of these, peristomal body profile, includes whether the peristomal area has a regular, inward or outward (bulging) profile and informs the selection of the most appropriate ostomy products to provide the right fit and a secure seal. Nine articles9,15,27,32,35,40,42,48,56 (six Level II, three Level III) were found to support peristomal body profile, including a high body mass index (BMI) and parastomal hernias, as an important risk factor for PSC. Ostomy construction indicates how ostomy height and location may impact the adherence and fit of the ostomy product; 18 articles9,12,13,17–19,22,24,27,30,31,34–37,41,47,50 (17 Level II, one Level III) were found dealing with the importance of ostomy construction in terms of appropriate diameter and height as well as the optimal surgical technique. Ostomy output type is a PSC risk factor depending on the output consistency and volume; 20 articles4,5,12,14,16,18,25–28,39,41,43,45,46,49,52–54,57 (one Level I, 16 Level II, three Level III) found evidence that an ileostomy increases the risk of PSC when compared with other ostomies.

The individual’s skin properties/conditions may also have an impact on PSC as the skin can be sensitive, dry, fragile, greasy, or oily, or have creases, scars, folds, wounds or underlying diseases; three articles41,42,54 (Level I, II and III: one each) alluded to skin properties/conditions as risk factors for developing PSC, particularly in terms of impaired mechanical quality of the barrier, skin creases, or age of the patient. Medication/treatment as a PSC risk factor includes side effects from immunosuppressive treatment, steroids, radiation therapy and chemotherapy; six articles15,26,32,36,55,57 (all Level II) showed chemotherapy and conditions such as diabetes to be risk factors for PSC. Both age and disabilities were identified as risk factors. Disabilities that may potentially and adversely impact on PSC are factors such as poor eyesight, low hand dexterity, or being a wheelchair user; nine articles5,18,25,28,35,36,40,48,57 (seven Level II, two Level III) identified age as a risk factor for PSC.

Self‑consciousness/self-care was also deemed to have an impact on PSC as denial or lack of coping skills could affect ostomy management and the ability to adapt to new life conditions; five articles5,14,18,31,35 (four Level II, one Level III) related to this subcategory were found, particularly those dealing with gender as a risk factor for PSC. Ostomy management is a risk factor depending on the individual’s ability to perform ostomy care techniques and routines in personal ostomy care practice; three articles9,41,51 (Level I, II and III: one each) showed the importance of ostomy management skills. Support from family or the individual’s social network to provide help was identified as another risk factor as was the individual’s standard of living, e.g., living conditions, level of income, hydration and nutrition, which may impact ostomy management; one article44 (Level II) supported standard of living as a risk factor displaying an impact of social restriction. No articles providing evidence for support from family/social network were found.

Ostomy product

The consensus development process identified seven product level PSC risk factors (Figure 4). In the literature review, 13 articles9,10,25,39,41,55,58–64 (two Level I61,64, seven Level II10,25,41,55,58–60, four Level III9,39,62,63), cited 16 times, were identified as supporting five of these seven risk factors (Appendix 1).

An identified risk factor, fit to the ostomy shape, highlights the fit between the pre-cut hole in the wafer and the ostomy; two articles9,41 (Level II and III: one each) were found providing evidence for this risk factor subcategory. Wear time is a risk factor for PSC, including how the chosen ostomy product will match the recommended and preferred wear time; three articles39,41,55 (two Level II, one Level III) were found dealing with issues related to wear time. The range and type of products accommodating individual needs, peristomal body profiles, and the type of ostomy output are considered PSC risk factors; three articles25,39,63 (one Level II, two Level III) were found describing, for example, the importance of accommodating individual needs to minimise PSC risk (e.g., by using a convex product).

The adhesive property of the ostomy product is a risk factor as it impacts adherence to the skin, moisture absorption and erosion; seven articles 9,10,58–61,64 (two Level I, four Level II, one Level III) were found describing how different components in the adhesives affect the peristomal skin. Filter performance and capacity of the ostomy product are also risk factors determining the ability of the ostomy product to retain solids and liquids and prevent ballooning or pancaking; only one relevant article62 (Level III) was found in this category. The fit to the body profile, which concerns how the ostomy products adapt to the peristomal body profile, and the ease of application or removal of the ostomy product, were also identified as PSC risk factors; however, no supporting articles were found in the literature.

Discussion

The research presented here depicts the development of an international consensus-based risk factor model for PSC which resulted in 24 risk factors organised in three overall categories, namely those at the system level (Healthcare system), individual level (Individual with an ostomy), and product level (Ostomy product). A systematic literature review identified 58 articles providing evidence for 19 of the 24 risk factors; it also highlighted the gap in good or high quality evidence for specific risk factors included in the model.

In recent years, ostomy products have been the subject of innovation and development to improve the fit or the performance of the ostomy pouching system. However, recent research showed that leakage and PSC are still impacting peoples’ lives and causing worries among people with an ostomy65,66. In a broader perspective, risk factors other than those inherent to ostomy products may offer unexplored opportunities to prevent leakage and skin issues by other means.

The consensus-based risk factor model for PSC gives an insight into which risk factors should be considered in the prevention of leakage and PSC. This risk factor model was developed in collaboration with ostomy care specialists, dermatologists and professors in wound and skin care representing 13 different countries. International consensus was reached among ostomy care specialists across 35 countries using a structured modified Delphi process. The large number and geographic diversity of the participants make this risk factor model unique in the field of PSC, allowing for regionally appropriate emphasis and implementation variations based on system requirements and patient expectations.

A systematic literature review demonstrated the evidence base for the identified risk factors, further strengthening and consolidating the model. For this systematic review, a broad search was conducted in several databases, and study selection was performed independently and thereafter aligned by two different reviewers, making the process robust and the quality of the review sound. By excluding study designs furnishing low levels of evidence, including case studies/series with <10 subjects, the quality of evidence of the included studies seems reasonable. The included studies were also quantitative in nature (except four articles9–12), providing statistical evidence for the risk factors. Therefore, the identified primary articles are believed to display an adequate level of clinical evidence (majority classified as Level II) to support the risk factor model, particularly in a field that is believed to be sparse on clinical evidence.

Among the three overall categories in the model, Individual with an ostomy had the most supporting evidence with 43 articles4,5,9,12–19,22,24–28,30–32,34–37,39–57 (74 citations). In general, most of the individual level risk factors included in this category were well supported by good quality evidence (mostly Level II), including BMI or hernia (peristomal body profile)9,15,27,32,35,40,42,48,56, age (disabilities)5,18,25,28,35,36,40,48,57, ostomy height/diameter (ostomy construction)9,12,13,17–19,22,24,27,30,31,34–37,41,47,50, and surgery type (ostomy construction9,12,13,17–19,22,24,27,30,31,34–37,41,47,50; these citations overlapped with surgical guidelines)13–15,17–20,22,24–27,30–32,34–37; ileostomy (ostomy/output type)4,5,12,14,16,18,25–28,39,41,43,45,46,49,52–54,57, as patients with an ileostomy have a higher risk of developing PSC; and gender (self‑consciousness/self-care, though gender as a risk factor could be conditioned by cultural differences rather than a difference in genders alone)5,14,18,31,35. In addition, at least Level II evidence was found for an individual’s ostomy management skills9,41,51, medication/treatment status15,26,32,36,55,57 (e.g., chemotherapy, diabetes), skin properties/conditions41,42,54, and standard of living44 being risk factors for PSC.

The Healthcare system was the next most supported risk factor category with 27 articles11,13–38 (cited 32 times within the category) providing evidence for five of the seven system level risk factors included in this category. These articles primarily described clinical evidence for surgical techniques13–15,17–20,22,24–27,30–32,34–37 or preoperative guidelines14,16,21,27–29,33, indicating the importance of accurate ostomy site marking and choosing the appropriate surgery technique.

In contrast, very few articles21,23,38 could be found related to care guidelines for ensuring the quality of the postoperative training of the patients. Only two articles supplied evidence on how the healthcare system could provide support for the patient post-discharge29,38. Nevertheless, these articles did show that support from healthcare professionals post-discharge and pre‑surgical education of the patient decreased the risk of developing PSC29,38.

In the Ostomy product category, five of the seven product-related risk factors were accompanied by evidence from the literature (13 articles9,10,25,39,41,55,58–64 being cited 16 times). Apart from the ‘adhesive properties’ of the ostomy product (which was backed by seven articles9,10,58–61,64 providing mostly Level I61,64/II10,58–60 evidence), the rest of the identified risk factors were supported by three or fewer studies. Since these risk factors were identified by healthcare professionals and scientists as important for developing PSC, one could wonder why the clinical evidence on these aspects of ostomy product development is sparse. Nonetheless, the few articles identified in this risk factor category do indicate that both the type25,39,63 and composition of an ostomy product9,10,58–61,64 are important in PSC development.

Overall, the risk factors pertaining to surgical technique (‘surgical guidelines’), ostomy output type, and ostomy construction had the most evidence from the literature with 1913–15,17–20,22,24–27,30–32,34–37, 204,5,12,14,16,18,25–28,39,41,43,45,46,49,52–54,57, and 189,12,13,17–19,22,24,27,30,31,34–37,41,47,50 related articles respectively. However, the majority of the articles in the surgical guidelines and ostomy construction categories overlap. Another 11 risk factors from the three overall categories (namely, preoperative ostomy site marking [preoperative guidelines], postoperative training of patients [care guidelines], peristomal body profile, the individual’s skin properties and conditions, his/her medication/treatment status, age [disability], self‑consciousness/self-care ability, ostomy management skills, range and type of ostomy products, adhesive property of the product, and product wear time) are also sufficiently described in the literature with evidence coming from three to nine studies.

Only five out of the 24 consensus-based risk factors identified in the model lacked any evidence from the literature. These include: system level factors such as access to appropriate ostomy product types and quantity, and the societal view of people with such a condition; individual level support from family or social network; and product level factors such as fit to the body profile and ease of application or removal of the ostomy product. While these factors are not supported by evidence from the literature, they are considered relevant and are internationally recognised based on expert opinion and experience. Combined with the five risk factor subcategories that were only supported by only one to two studies (namely, access to post-discharge programs29,38, level of education of healthcare professionals11, an individual’s income/standard of living44, fit of the ostomy product to the ostomy shape9,41, and filter performance and capacity of the ostomy product62), these represent areas where further research is particularly needed.

It is a goal that the risk factor model for PSC can be used as a tool in daily practice in ostomy care. Some of the identified risk factors can be addressed at an early stage when the patient is discharged from the hospital and can save the patients from some of the initial issues they may face with a trial-and-error approach to self-care. The extensive and geographically diverse process of development of the model make it reasonably generalisable to population of individuals living with an ostomy and allow for regionally appropriate implementation variations. The model thus has the potential to be included in a healthcare professional assessment, intervention and monitoring guide to promote a holistic approach to ensure peristomal skin health and quality of life for people with an ostomy.

Conclusions

The purpose of developing a risk factor model on PSC was to explore existing evidence- and experience-based risks leading to PSC, with the purpose of providing a valid assessment method to guide individualised recommendations and decision making in ostomy care. The intention is to help prevent PSC.

By conducting a comprehensive literature research and by working with specialists in the field of ostomy care we have obtained a solid knowledge base upon which the risk factor model on PSC has been developed.

With the personalised risk factor assessment including quality of life, peristomal body profile and peristomal skin, hand in hand with a professional holistic judgement, a trial-and-error approach should be avoided to save the individual patient from severe negative impact on health and quality of life.

Conflicts of interest, source of funding

This work was supported by Coloplast A/S. Anne Steen Hansen, Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft, Zenia Størling and Lene Feldskov Nielsen were employed by Coloplast A/S when the model was developed, and the manuscript was prepared.

Lina Martins, Jane Fellows, Birgitte Dissing-Andersen, Gillian Down, David Voegeli, Tonny Karlsmark and Gregor Jemec are members of the Coloplast Skin Expert Panel and have received honoraria for participating in different Coloplast Advisory Boards. They have not received compensation for involvement in this publication.

All authors were involved in the writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript, gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Anne Steen Hansen and Lene Feldskov Nielsen were responsible for the risk factor model for PSC and Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft for the literature review. References were screened independently by Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft and Lene Feldskov Nielsen.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the COF and the Coloplast Skin Expert Panel who participated in discussions and shared their invaluable experience about PSC – Gemma Gascón Guitart who was part of the workshops in the beginning of the process and started the literature search in collaboration with Information Specialist Jette Brandt, M.L.I Sc, Library and Information Science, who conducted the literature searches, as well as Louise C. Rosenberg Christ, PhD and Kaushik Sengupta, PhD (Larix A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) for editorial and medical writing services which were funded by Coloplast A/S.

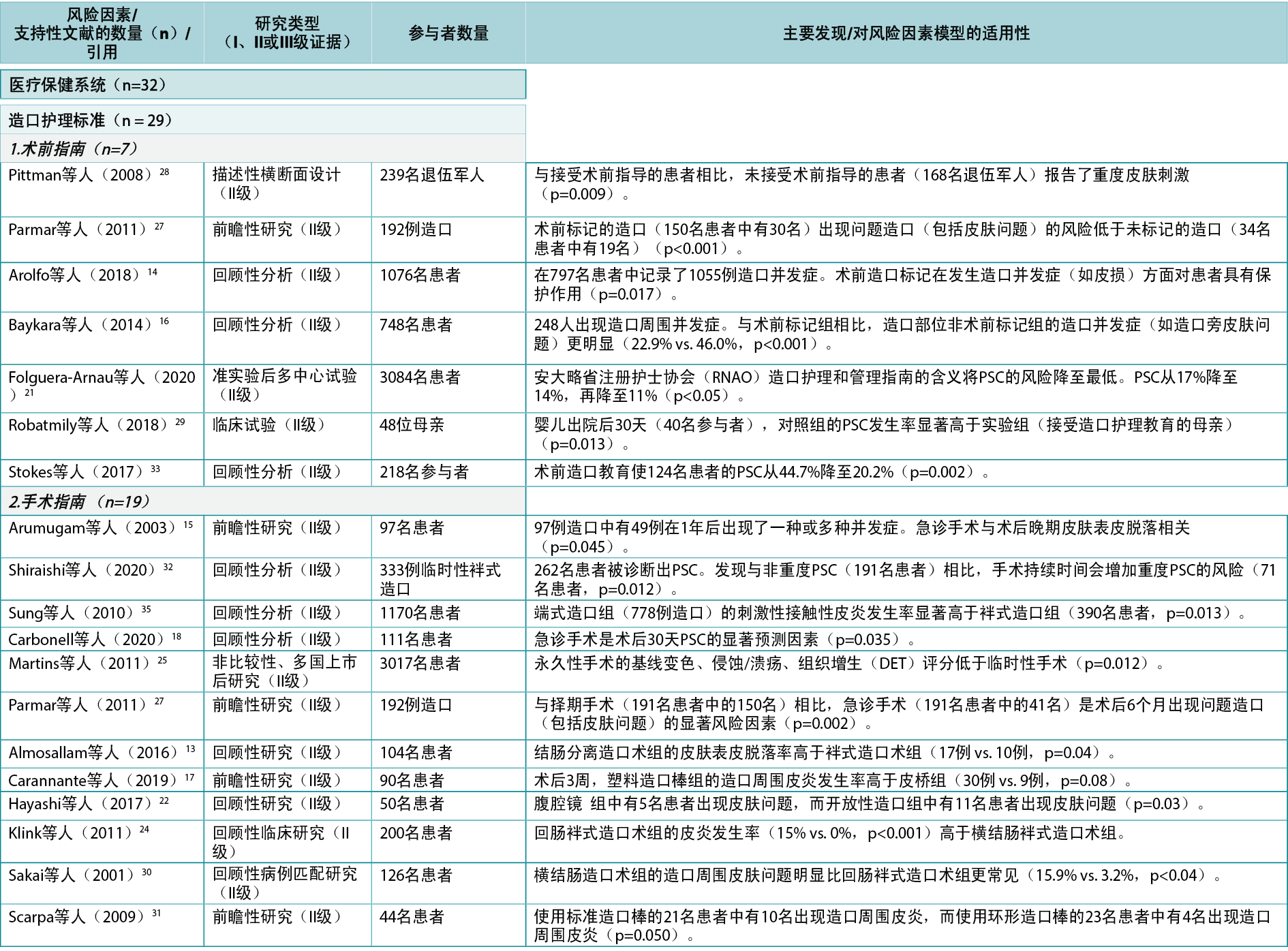

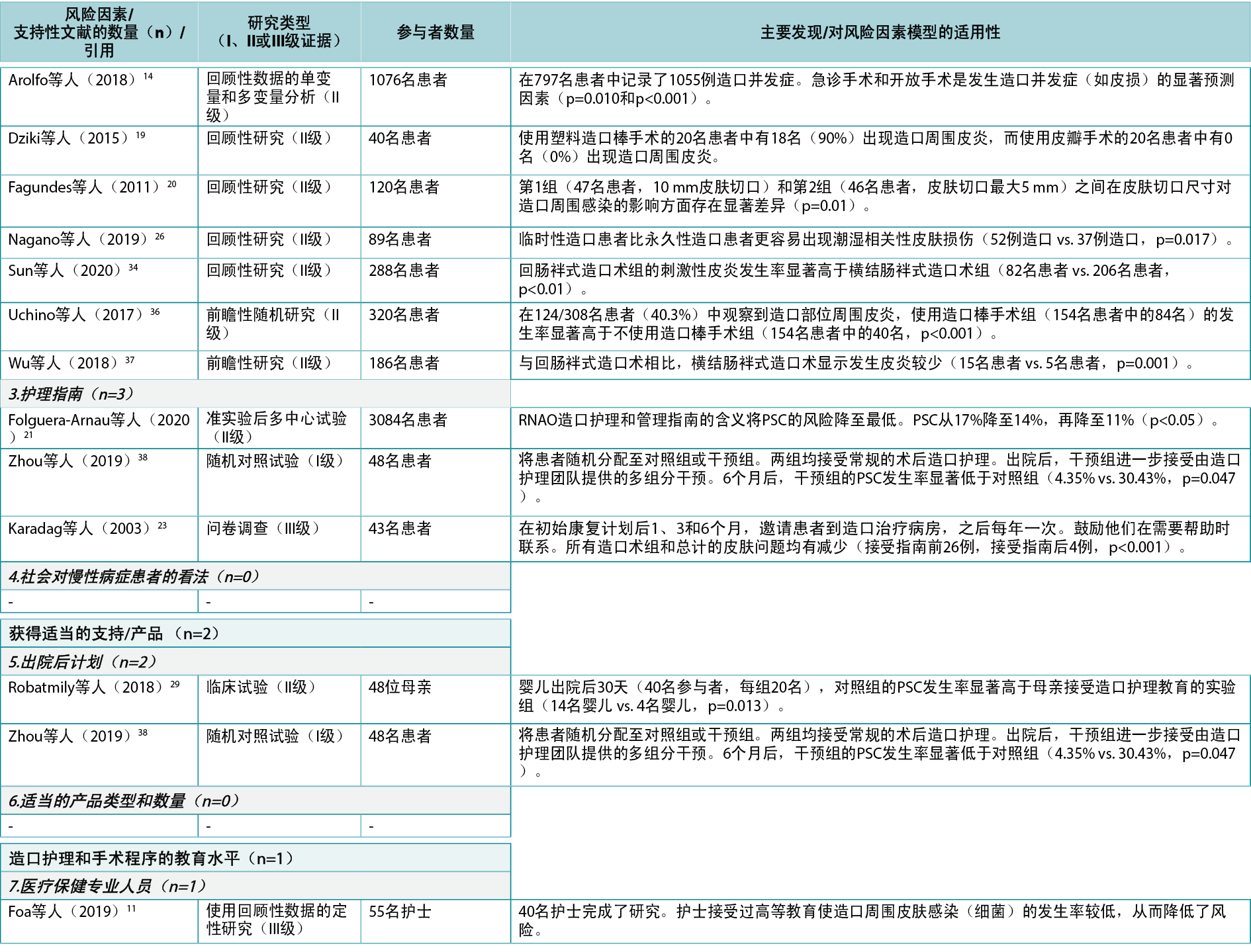

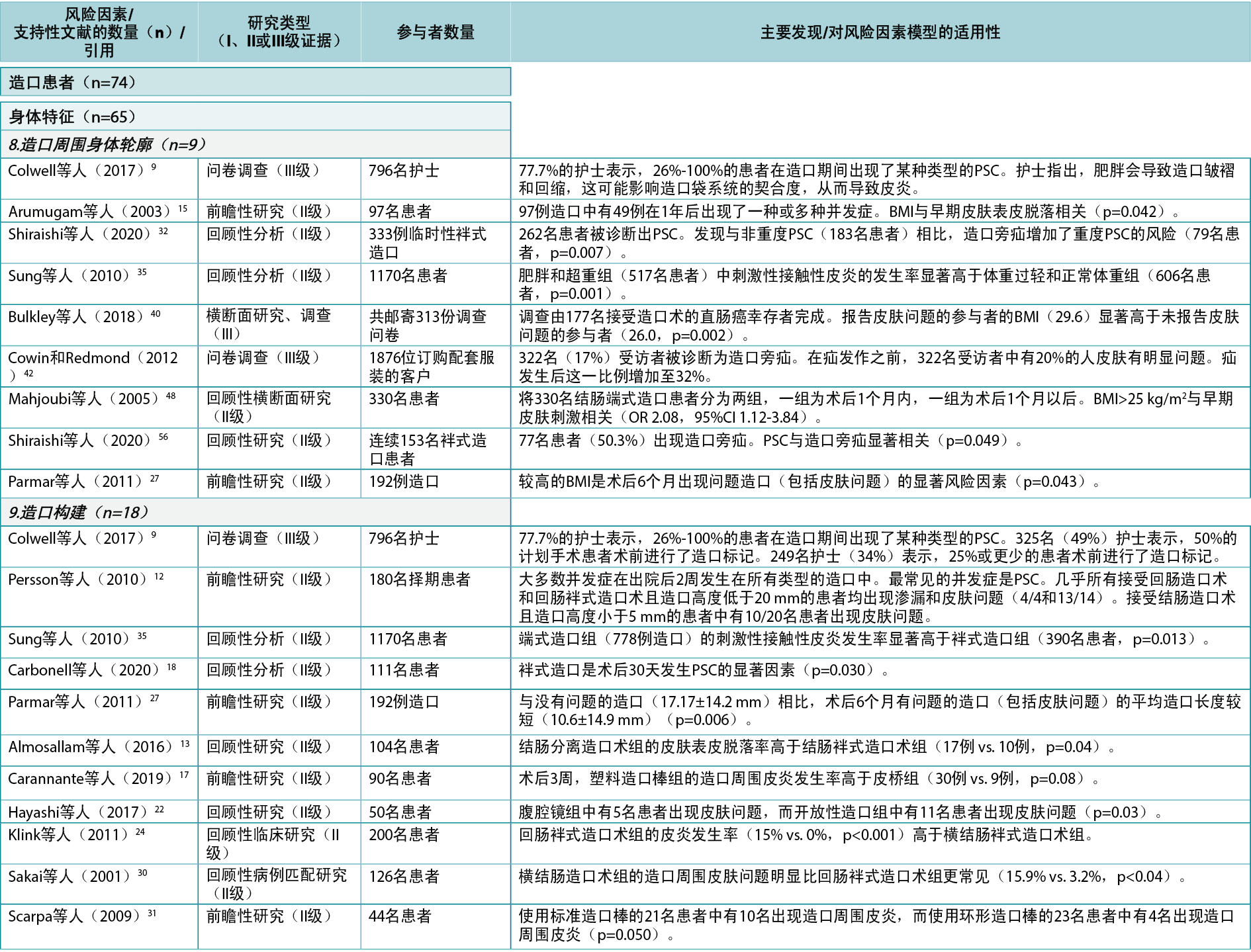

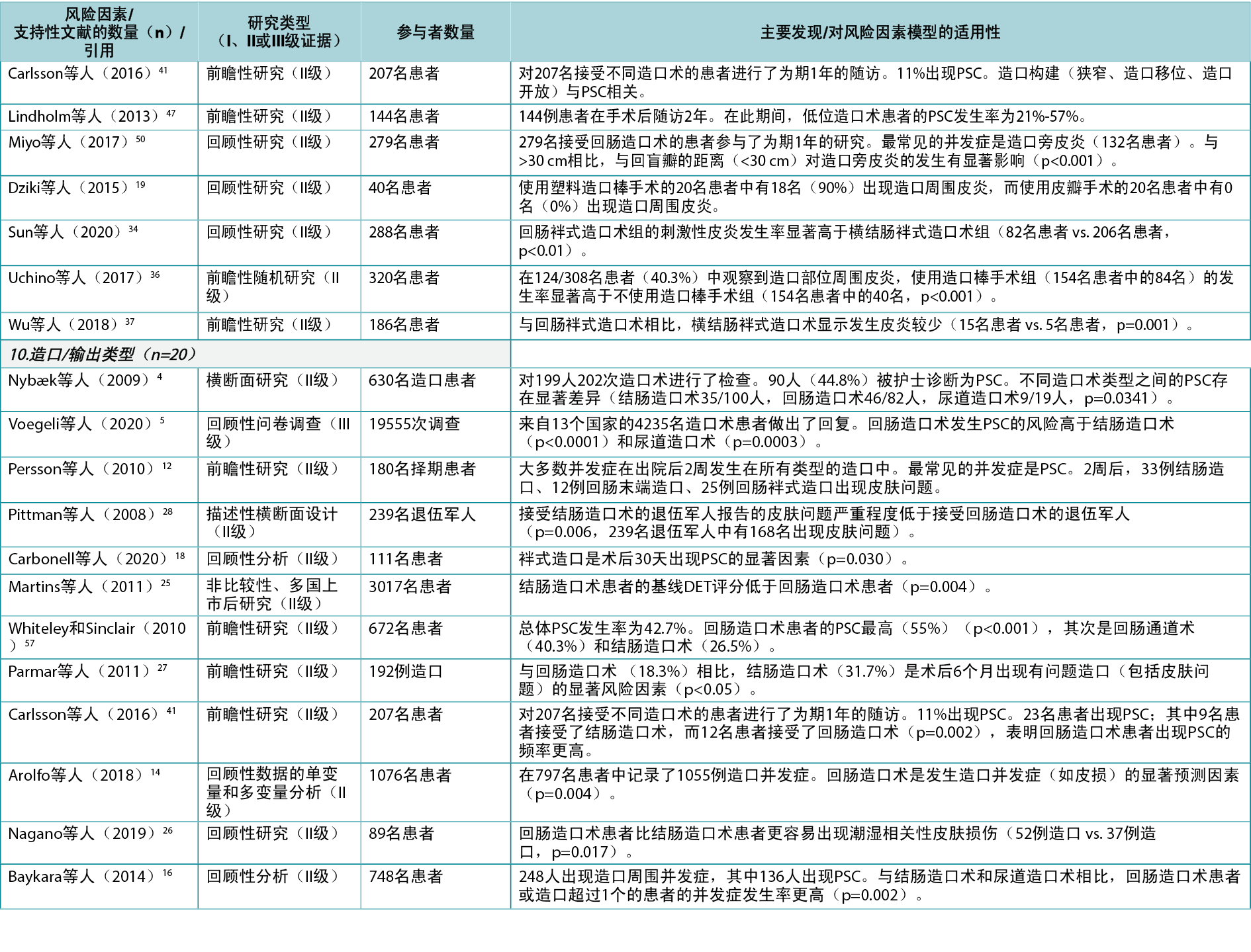

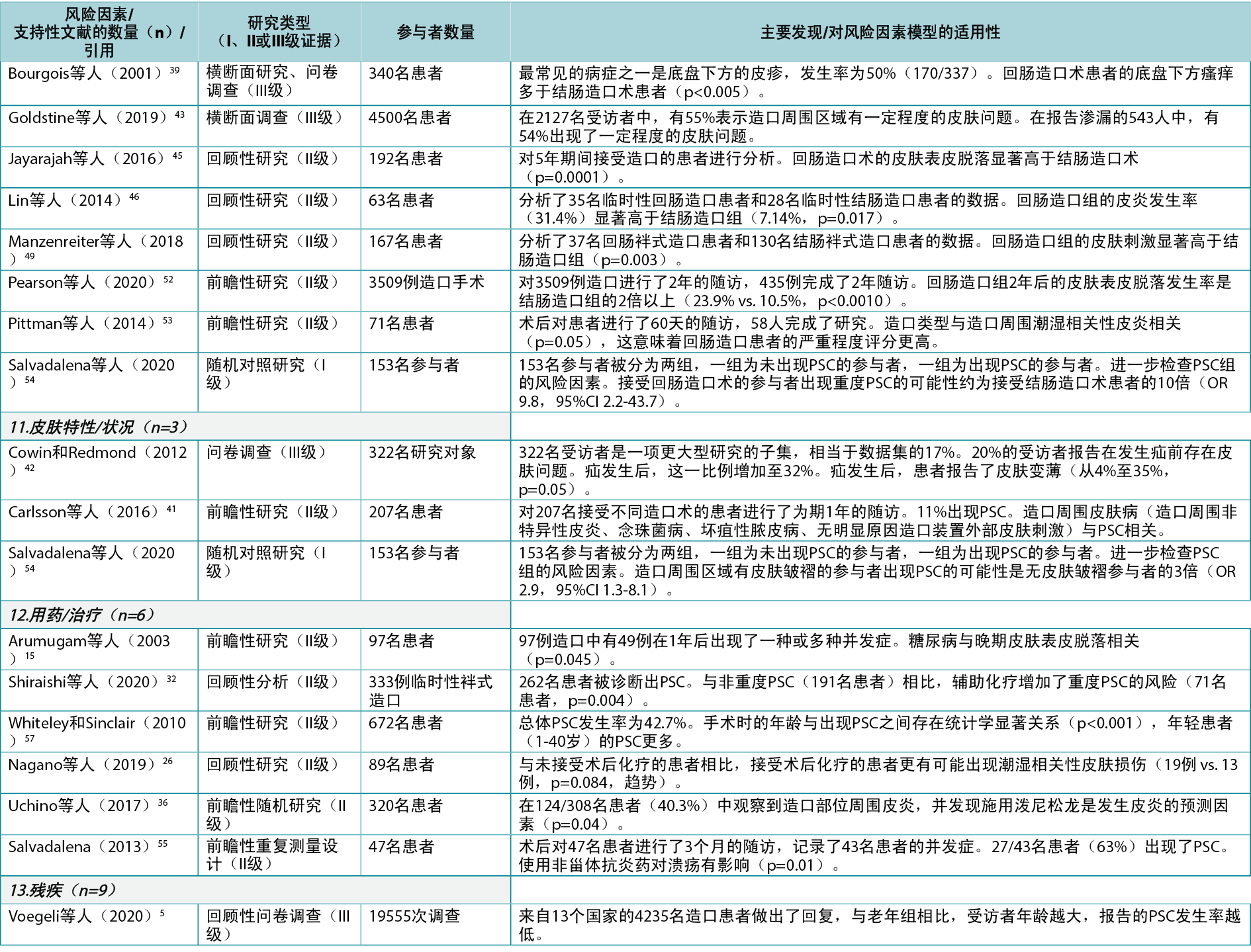

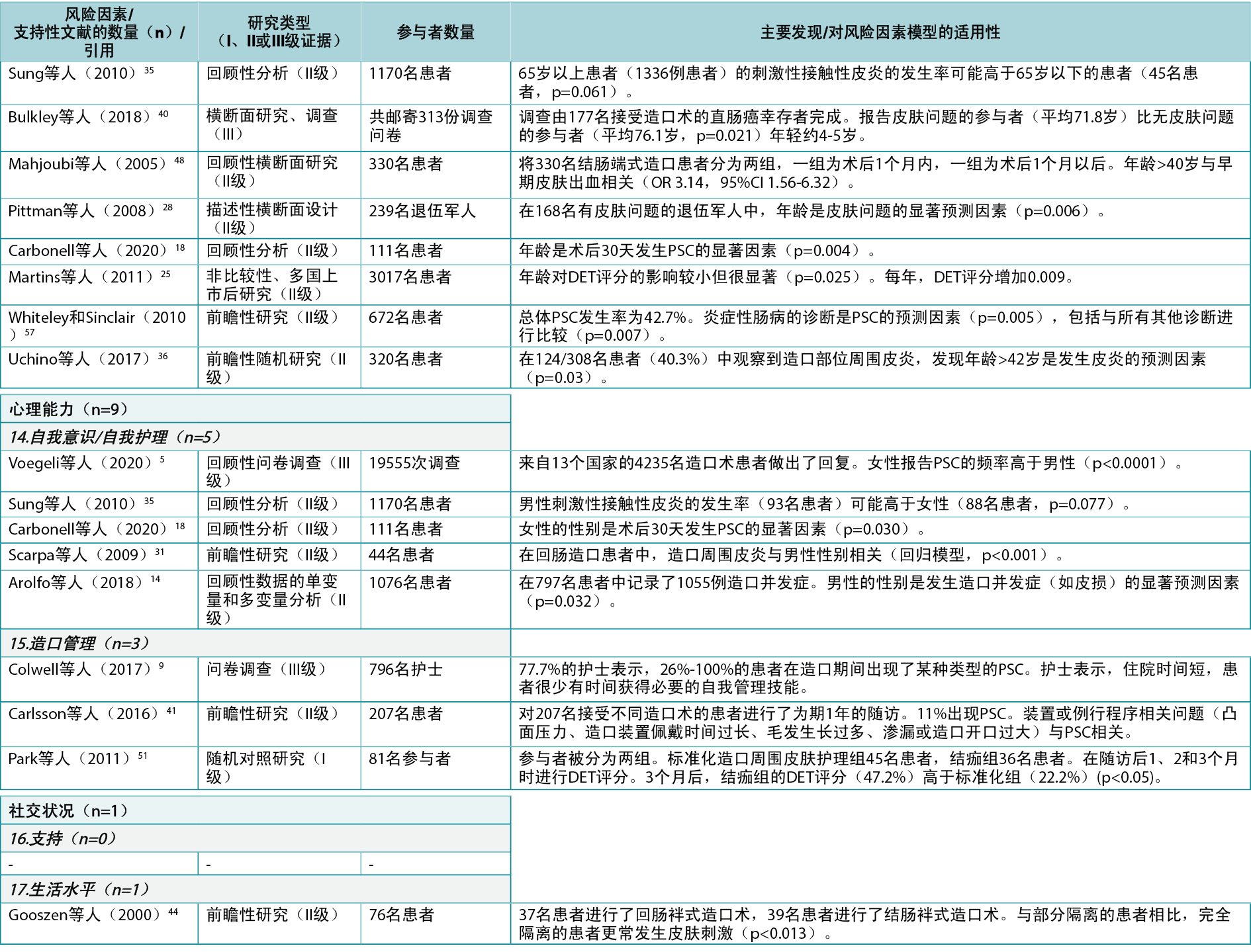

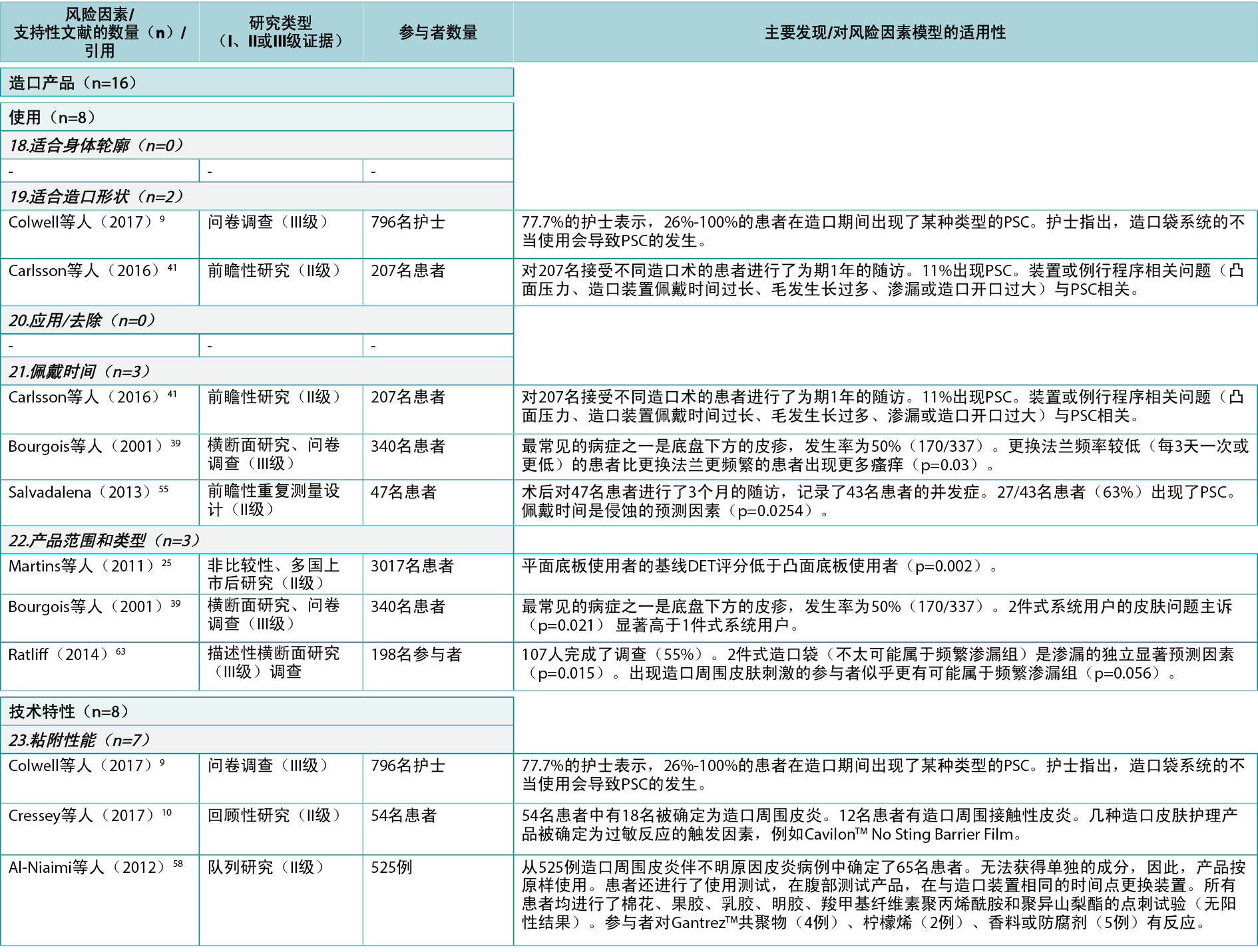

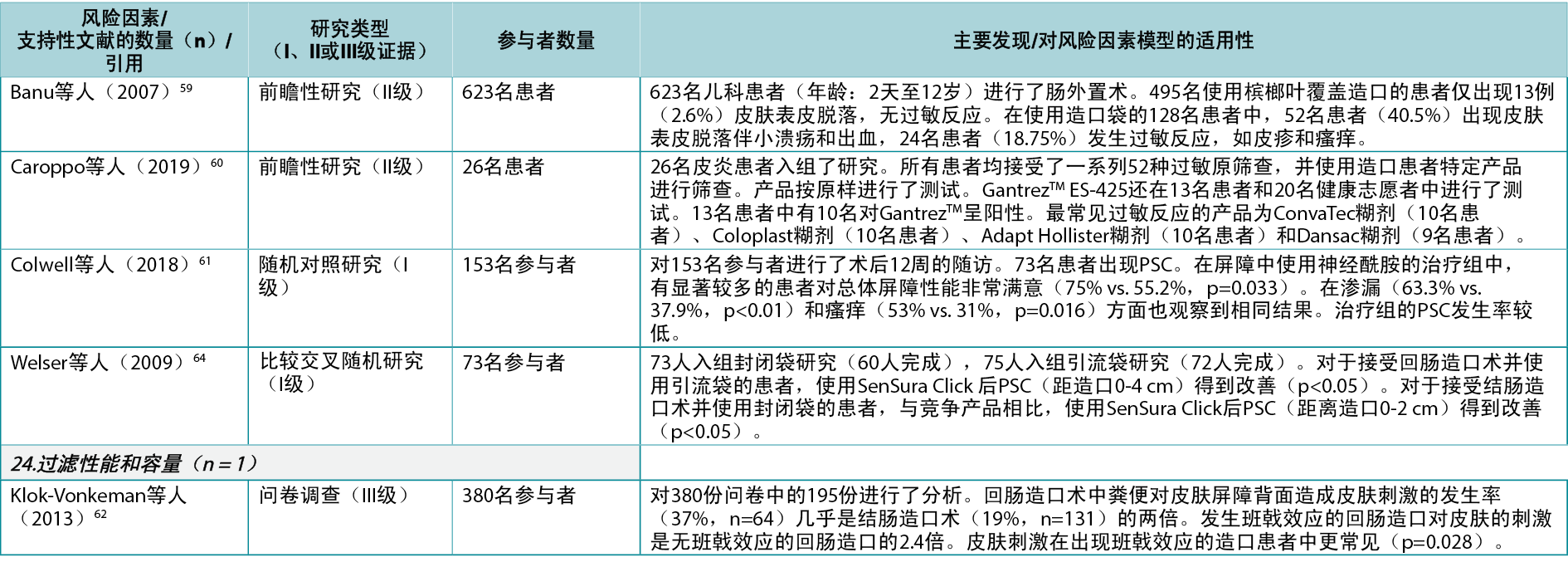

Appendix 1. Literature supporting the identified risk factors.

造口周围皮肤并发症的风险因素模型

Anne Steen Hansen, Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft, Lina Martins, Jane Fellows, Birgitte Dissing Andersen, Gillian Down, Tonny Karlsmark, Gregor Jemec, David Voegeli, Zenia Størling and Lene Feldskov Nielsen

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.4.14-30

摘要

对于造口患者,渗漏和造口周围皮肤并发症(PSC)是经常同时出现的常见问题。更好的预防这些问题的方法可以改善这些患者的生活质量。本研究的目的是确定并建立PSC风险因素模型。

通过与Coloplast内部造口护理专家、Coloplast皮肤专家小组、全球Coloplast造口论坛(COF)和18个国家COF委员会(共同代表来自世界各地的400多名造口护理护士)的讨论会议确定风险因素。这些专家组确定了风险因素,对其进行了分析、分类,并分几个阶段进行了讨论,得到了PSC的风险因素模型,包括三个总体类别及其相关的风险因素(n=24)。通过改良的Delphi过程,来自35个国家的4000多名造口护理专家对模型达成了共识。同时,对PSC的风险因素进行了系统性文献综述,以确定支持该模型的主要文献。将2000年至2020年8月发表的相关文章纳入综述,发现58篇文章支持总计24个风险因素中的19个。PSC的风险因素模型已获得Coloplast皮肤专家小组和全球COF的批准,并有可能被纳入医疗保健专业人员指南,并在日常临床实践中作为工具使用。

引言

对于造口患者,渗漏和造口周围皮肤并发症(PSC)的发生风险是典型的担忧。据估计,91%的造口患者担心渗漏,76-77%的造口患者在过去6个月内发生过渗漏1,2。担心渗漏可能会影响日常活动和社交互动;此外,渗漏是发生PSC的主要因素。

在一项研究中,四种主要诊断(粪便引起的糜烂、浸渍、红斑和接触性皮炎)占所有造口相关诊断的77%,这些均与接触造口流出物有关3。当皮肤完整性受损时,皮肤和造口产品之间的粘附性受到影响,可能导致进一步渗漏4。因此,可能会出现疼痛、焦虑、对造口产品丧失信心,从而导致社会活动参与减少的风险,并对个人的生活质量产生负面影响1。

缺乏对PSC的认识似乎很普遍。一项研究报告,只有不到一半(43%)的PSC患者意识到该问题4。提高造口患者对可能导致渗漏和PSC的风险因素的认识,有助于预防PSC。

除造口产品固有的因素外,还有一些因素可能使造口患者易患PSC4,5。其中一些风险因素可以在常规门诊就诊时加以解决,以提高造口患者的认识,并启动缓解措施,作为PSC预防策略的一部分。识别这些风险因素也可能产生新的干预措施来预防造口患者发生渗漏和PSC。

基于共识的PSC风险因素模型的概念被确定为一种潜在解决方案,可能帮助人们认识到可以干预哪些风险因素以预防PSC发生。本研究的目的是就PSC最重要的风险因素达成共识,并将其纳入风险因素模型,同时确定与这些风险因素相关的文献中的证据和缺口。目的是指导造口护理实践,并为医疗保健专业人员和造口患者预防PSC提供支持。我们假设,支持预防PSC日常实践的综合PSC风险因素模型的开发过程将突出文献中支持该模型的良好或高质量证据的差距。

方法

风险因素模型的开发

PSC风险因素模型是与 Coloplast皮肤专家小组(由皮肤病、伤口和造口护理领域的7名专家组成)、全球Coloplast造口论坛(全球COF)(由13名国际公认专家组成的独家实体)和国家COF委员会合作开发的。国家COF委员会代表来自世界各地的400多名造口护理护士,包括比利时、加拿大、捷克共和国、丹麦、芬兰、法国、徳国、意大利、荷兰、挪威、波兰、斯洛伐克、瑞典、英国和美国。

PSC风险因素模型的开发是一个多步骤的过程,包括四个主要阶段,即范围界定、探索、趋同和批准(图1)。

图1.PSC风险因素模型的开发方法。

A. 第1步:范围界定阶段。与皮肤专家小组、全球COF、国家COF委员会以及Coloplast内部来自研发部和市场部的造口护理专家举行会议,集思广益讨论PSC的风险因素。与皮肤专家小组和全球COF的讨论基于范围界定的文献综述,指导了第2步和第3步。

B. 第2步:探索阶段。在第1步中收集的所有数据被Coloplast内部皮肤项目组分为10个主题后,皮肤专家小组、全球COF和国家COF委员会将这10个主题进一步浓缩,最终形成Coloplast皮肤项目组概述的三个总体类别。

C. 第3步:趋同阶段。将这三个类别提交给皮肤专家小组和全球COF,然后国家COF委员会对其进行讨论,旨在使这三个类别的内容和名称保持一致,Coloplast内部皮肤小组将这三个类别调整为最终草案。同时,进行了系统性文献综述,以支持讨论和建立共识。在国际共识过程产生最终版本之前,皮肤专家小组和全球COF同意了最终草案。

D. 第4步:批准阶段。皮肤专家小组和全球COF批准了PSC的最终风险因素模型。

在第1步(范围界定阶段)中,与皮肤专家小组举行了首次会议,集思广益讨论PSC的风险因素。小组成员分别对风险因素提出建议;小组内的进一步讨论有助于确定其他风险因素和风险因素类别。全球COF、国家COF委员会以及Coloplast内部来自研发(R&D)部和市场部的造口护理专家重复了这一讨论过程。同时,对PSC风险因素进行了文献检索。该检索的结果与皮肤专家小组和全球COF共享,以指导后续步骤。

在第2步(探索阶段)中,Coloplast内部皮肤项目组将在范围界定阶段从不同专家小组收集的所有数据归类为不同主题。这些具有相互关联的风险因素的主题被提交给皮肤专家小组、全球COF和国家COF委员会,他们各自的任务是将这些主题进一步浓缩为总体风险因素类别。

在第3步(趋同阶段)中,向皮肤专家小组和全球COF提交总体风险因素类别,然后在国家COF委员会内举行讨论会议,以使这些类别的内容和命名一致。Coloplast内部皮肤项目组根据国家COF委员会的意见更新了类别,并编写了最终草案。在进行国际共识过程之前,皮肤专家小组和全球COF就该草案达成了一致意见,得到了风险因素模型的最终版本

6,7。共识过程在单独的出版物中有详细描述7。简而言之,使用改良的Delphi过程,35个国家的造口护理专家达成了共识。该阶段得到了系统性文献综述(见下文描述)的支持,以判断每个已确定风险因素背后的证据等级。在第4步(批准阶段)中,皮肤专家小组和全球COF批准了最终的风险因素模型7。

文献综述

在趋同阶段进行了系统性综述,以支持讨论和建立共识,并判断已确定风险因素背后的证据等级。文献检索由信息专家使用PubMed(包括Medline)、Derwent世界专利索引和CINAHL(护理与联合健康期刊累积索引)数据库进行。检索于2020年6月19日(PubMed和Derwent)和2020年8月19日(CINAHL)进行。

检索时间线仅限于2000年至2020年(8月)发表的文章。时间间隔是根据获得的相关已发表文献选择的;认为10年的时间间隔太有限,无法在造口护理领域中获得最佳数量的相关文献。通过检索与皮肤描述词相关的文本词,并将其与皮肤问题和造口术同义词相结合,使检索范围足够广泛。此外,还将检索词映射到Medline中的以下医学主题词(MeSH):皮肤、皮炎、真皮、表皮、皮肤病药物、造口术、结肠造口术和回肠造口术。将生成的检索字符串与布尔运算符(AND、OR)结合使用,得到最终结果(图2)。

图2.文献检索方法:检索字符串。

研究选择过程通过图3中的PRISMA流程图进行描述。根据标题和摘要手动识别重复文献。这些文献被删除,然后由两位作者根据标题和摘要独立筛选剩余的参考文献。标题或摘要将包括与造口术/造口和问题相关的单词或待纳入的PSC。对两次独立的筛选进行了比较,并根据商定的选择制定了文章列表。如果对文章的相关性有疑问,则咨询第三作者。根据排除标准(如综述、概述、少于10例受试者的病例研究/病例系列、评论文章、社论、会议摘要和书籍章节)对所选文章进行评价;目的是查找提供临床证据支持风险因素模型的已发表的主要文献。用英语以外语言撰写的文章也被排除在外。然后,阅读剩余文章的全文版本,如果描述了已确定的PSC风险因素的证据,并且两名审查员均同意纳入,则将研究纳入。最后,使用改编自John Hopkins循证实践方法的3分量表评价了所选文章的证据质量8。选择的支持风险因素模型的文章得到了Coloplast皮肤专家小组和全球COF的整合和批准。

结果

风险因素模型中的风险因素类别

在PSC风险因素模型开发的第1步(范围界定阶段)中,确定了100多个风险因素。在第2步(探索阶段)中,这些风险因素被浓缩为10个后续主题:皮肤相关;用户特征;资源;环境;心理依从性和适应性;造口和身体轮廓;输出特性;产品使用、依从性和例行程序;产品性能;培训和教育。在专家小组(皮肤专家小组、全球COF和国家COF委员会)的帮助下,这10个具有相互关联风险因素的主题被进一步浓缩,得到了总体风险因素的三个建议类别Å\Å\医疗保健系统、造口患者和造口产品(图

4)。

在第3步(趋同阶段)中,进一步细化了三个类别的内容和命名,得到了24个风险因素子类别(图

4)。在第4步(批准阶段)中,皮肤专家小组和全球COF批准了这些风险类别和子类别,构成最终的风险因素模型。

文献检索结果

基于组合检索,共找到3216篇参考文献(图3)。剔除844篇重复文献后,通过标题和摘要筛选2372篇文献,阅读并筛选235篇进行最终选择。有4篇文章无法检索到;因此将其排除。4篇文章9-12未显示任何统计数据,但由于其样本量相对较大(18-796例受试者)而被纳入。综述共纳入58篇文章,支持已确定的24个风险因素子类别中的19个。在纳入的文章中,发现27篇属于医疗保健系统类别11,13-38(在该类别中被引用32次),43篇属于造口患者类别4,5,9,12-19,22,24-28,30-32,34-37,39-57(74次引用),13篇属于造口产品类别9,10,25,39,41,55,58-64(16次引用);发现几篇文章符合两个或多个类别或子类别。文章被分为三个证据等级8:I 级(高),5篇38,51,54,61,64;II级(良

好),43篇4,10,12–22,24–37,41,44–50,52,53,55–60;III级(低),10篇5,9,11,39,40,42,43,62,63。支持每个风险因素类别中每个已确定风险因素的单项研究列表见附录1。

图3.文献检索方法:PRISMA流程图

风险因素分类

医疗保健系统

医疗保健系统类别包括与医疗保健系统的接触、指导和输入相关的7个系统级PSC风险因素(图4)。在文献综述中,发现27篇文献11,13-38(1篇I级38,24篇II级13-22,24-37,2篇III级11,23),32次类别内引用,支持这7个风险因素中的5个(附录1)。

在该类别的个体风险因素中,术前指南包括指导患者为外科手术做准备、标记造口部位和对患者术后造口生活提供建议;发现7篇文章14,16,21,27-29,33(均为II级)支持术前造口部位标记(发生PSC的一个风险因素)的重要性。

手术指南包括创建造口的最佳实践,以获得最佳患者结局;发现19篇文章13-15,17-20,22,24-27,30-32,34-37(均为II级)为手术技术提供了临床证据,并指出选择可降低PSC风险的外科手术的重要性。护理指南包括高质量的术后培训和随访;发现3篇文章21,23,38(I、II和III级:各1篇)与确保患者术后培训质量的指南有关。出院后计划包括健康保险和医疗保健系统是否提供随访项目;发现2项临床试验29,38(I级和II级:各1项)为充分获得出院后计划的重要性提供了证据,并证明出院后医疗保健专业人员的支持以及患者的术前教育可降低发生PSC的风险。

医疗保健专业人员作为一个风险因素子类别,包括一般教育水平、接受继续教育的机会以及采取的护理和外科手术类型;一项定性研究11(III级)讨论了医疗保健专业人员的教育水平对于为患者提供最佳支持的重要性。该类别中的其他风险因素为获得适当的造口产品类型和数量以满足任何需求,以及社会对慢性疾病患者的看法;未发现这些子类别的支持性证据。

造口患者

在该类别中,共确定了10个个体层面的PSC风险因素(图4)。文献综述确定了43篇文章4,5,9,12–19,22,24–28,30–32,34–37,39–57(2篇I级51,54,35篇II级4,12–19,22,24–28,30–32,34–37,41,44–50,52,53,55–57,6篇III级5,9,39,40,42,43),被引用74次,支持这10个风险因素中的9个(附录1)。其中的造口周围身体轮廓包括造口周围区域是否具有规则的、向内或向外(膨出)的轮廓,并告知选择最合适的造口产品,以提供正确的贴合和安全的密封。发现9篇文章9,15,27,32,35,40,42,48,56(6篇II级,3篇III级)支持造口周围身体轮廓,包括高身体质量指数(BMI)和造口旁疝,这是PSC的重要风险因素。造口构建表明造口高度和位置如何影响造口产品的粘附性和契合度;发现18篇文章9,12,13,17–19,22,24,27,30,31,34–37,41,47,50(17篇II级,1篇III级)涉及造口构建在适当的直径和高度以及最佳手术技术方面的重要性。造口输出类型是一个PSC风险因素,取决于输出一致性和体积;20篇文章4,5,12,14,16,18,25–28,39,41,43,45,46,49,52–54,57(1篇I级,16篇II级,3篇III级)发现证据表明,与其他造口术相比,回肠造口术会増加PSC的风险。

个体皮肤特性/状况也可能对PSC产生影响,因为皮肤可能敏感、干燥、脆弱、油腻、出油或有皱纹、疤痕、褶皱、伤口或潜在疾病;3篇文章41,42,54(I级、II级和III级:各1篇)提到皮肤特性/状况是发生PSC的风险因素,尤其是在屏障机械质量受损、皮肤皱纹或患者年龄方面。作为PSC风险因素的用药/治疗包括免疫抑制治疗、类固醇、放疗和化疗的副作用;6篇文章15,26,32,36,55,57(均为II级)表明化疗和糖尿病等疾病是PSC的风险因素。年龄和残疾均被确定为风险因素。可能对PSC产生潜在不利影响的残疾包括视力不佳、手部灵活性差或使用轮椅等因素;9篇文章5,18,25,28,35,36,40,48,57(7篇II级,2篇III级)将年龄确定为PSC的风险因素。

自我意识/自我护理也被认为对PSC有影响,因为否认或缺乏应对技能可能影响造口管理和适应新生活条件的能力;发现了与该子类别相关的5篇文章5,14,18,31,35(4篇II级,1篇III级),尤其是将性别作为PSC风险因素的文章。造口管理是一个风险因素,取决于个体在个人造口护理实践中执行造口护理技术和例行程序的能力;3篇文章9,41,51(I级、II级和III级:各1篇)显示了造口管理技能的重要性。家庭或个人社交网络提供的帮助支持被确定为另一个风险因素,以及个人的生活水平,例如生活条件、收入水平、补水和营养,这些都可能影响造口管理;一篇文章44(II级)支持将生活水平作为显示社会限制影响的风险因素。未发现为家庭/社交网络支持提供证据的文章。

造口产品

共识建立过程确定了7个产品层面的PSC风险因素(图4)。在文献综述中,13篇文章9,10,25,39,41,55,58-64(2篇I级61,64,7篇II级10,25,41,55,58–60,4篇III级9,39,62,63)被引用16次,被确定为支持这7个风险因素中的5个(附录1)。

一个符合造口形状的已确定风险因素强调了晶片中预切孔和造口之间的适合性;发现2篇文章9,41(II级和III级:各1篇)为该风险因素子类别提供了证据。佩戴时间是PSC的一个风险因素,包括所选择的造口产品如何匹配推荐和首选的佩戴时间;发现了3篇文章39,41,55(2篇II级,1篇III级)涉及与佩戴时间相关的问题。适应个体需求的产品范围和类型、造口周围身体轮廓和造口输出类型被视为PSC风险因素;发现3篇文章25,39,63(1篇II级,2篇III级)描述了适应个体需求以将PSC风险降至最低的重要性(例如,通过使用凸面产品)。

造口产品的粘附性能是一个风险因素,因为它会影响对皮肤的粘附性、吸湿性和侵蚀性;发现7篇文章9,10,58-61,64(2篇I级,4篇II级,1篇III级)描述了粘合剂中的不同成分如何影响造口周围皮肤。造口产品的过滤性能和容量也是风险因素,决定了造口产品保留固体和液体以及防止膨胀或压扁的能力;在该类别中仅发现一篇相关文章62(III级)。与身体轮廓的契合度(涉及造口产品如何适应造口周围身体轮廓)以及造口产品应用或移除的便利性也被确定为PSC风险因素;但是在文献中未发现支持性文章。

暠4.PSC돨루麴凜羹친謹

讨论

本文介绍的研究描述了基于国际共识的PSC风险因素模型的开发,该模型将24个风险因素分为三个总体类别,即系统层面(医疗保健系统)、个体层面(造口患者)和产品层面(造口产品)。一项系统性文献综述确定了58篇文章,为24个风险因素中的19个提供了证据;还强调了模型中包含的特定风险因素的良好或高质量证据的差距。

近年来,造口产品一直是创新和开发的主题,以改善造口袋系统的契合度或性能。然而,最近的研究表明,渗漏和PSC仍然影响着人们的生活,并引起造口患者的担忧65,66。从更广泛的角度来看,造口产品固有风险因素以外的风险因素可能提供尚未探索的机会,以通过其他方式预防渗漏和皮肤问题。

基于共识的PSC风险因素模型让我们了解在预防渗漏和PSC时应考虑哪些风险因素。该风险因素模型是与代表13个不同国家的造口护理专家、皮肤科医生、伤口和皮肤护理教授合作开发的。采用结构化的改良Delphi过程,35个国家的造口护理专家达成了国际共识。参与者的大数量和地理多样性使得该风险因素模型在PSC领域独一无二,允许基于系统要求和患者期望进行适合于区域的重点调整和实施变化。

系统性文献综述证明了已确定风险因素的证据基础,进一步加强和巩固了模型。对于本系统性综述,我们在几个数据库中进行了广泛的检索,研究选择是独立进行的,随后由两名不同的审查员进行协调,从而确保了过程的稳健性和综述的质量。通过排除提供低等级证据的研究设计,包括受试者<10名的病例研究/系列,纳入研究的证据质量似乎是合理的。纳入的研究在本质上也是定量研究(4篇文章9-12除外),为风险因素提供了统计学证据。因此,确定的主要文章被认为显示出了充分的临床证据等级(大部分被分类为II级)来支持风险因素模型,尤其是在被认为缺乏临床证据的领域。

在模型的三个总体类别中,造口患者的支持性证据最多,有43篇文章4,5,9,12–19,22,24–28,30–32,34–37,39–57(74次引用)。总体而言,该类别中包括的大多数个体层面的风险因素都得到了高质量证据(大部分为II级)的充分支持,包括BMI或疝(造口周围身体轮廓)9,15,27,32,35,40,42,48,56、年龄(残疾)5,18,25,28,35,36,40,48,

57、造口高度/直径(造口构建)9,12,13,17-19,22,24,27,30,31,34-37,41,47,50和手术类型(造口构建9,12,13,17–19,22,24,27,30,31,34–37,41,47,50;这些引用与手术指南重叠)13-15,17-20,22,24-27,30-32,34-37;回肠造口(造口/输出类型)4,5,12,14,16,18,25–28,39,41,43,45,46,49,52–54,57,因为回肠造口患者发生PSC的风险较高;性别(自我意识/自我护理,尽管性别作为风险因素可能受到文化差异的影响,而不仅仅是性别差异的影响)5,14,18,31,35。此外,至少II级证据表明个体的造口管理技能9,41,51、用药/治疗状态15,26,32,36,55,57(例如化疗、糖尿病)、皮肤特性/状况41,42,54和生活水平44是PSC的风险因素。

医疗保健系统是第二受支持的风险因素类别,27篇文章11,13-38(在该类别中被引用32次)为该类别中包含的7个系统层面风险因素中的5个提供了证据。这些文章主要描述了手术技术13–15,17–20,22,24–27,30–32,34–37或术前指南14,16,21,27–29,33的临床证据,表明了准确标记造口部位和选择合适的手术技术的重要性。

相比之下,关于确保患者术后培训质量的护理指南的文章很少21,23,38。只有2篇文章提供了医疗保健系统如何为出院后患者提供支持的证据29,38。尽管如此,这些文章确实表明,医疗保健专业人员对患者出院后和术前教育的支持降低了发生PSC的风险29,

38。

在造口产品类别中,7个产品相关风险因素中有5个附有文献证据(13篇文章9,10,25,39,41,55,58–64被引用16次)。除了造口产品的“粘附性能”(得到了7篇文章9,10,58-61,64的支持,主要提供了I级61,64/II级10,58-60证

据),其余确定的风险因素得到了3项或更少研究的支持。由于这些风险因素被医疗保健专业人员和科学家确定为发生PSC的重要因素,人们可能会想知道为什么关于造口产品开发这些方面的临床证据很少。尽管如此,在该风险因素类别中确定的几篇文章确实表明,造口产品的类型25,39,63和组成9,10,58–61,64对PSC发生都很重要。

总体而言,与手术技术(“手术指南”)、造口输出类型和造口构建相关的风险因素从文献中得到的证据最多,分别有19篇13–15,17–20,22,24–27,30–32,34–

37、20篇4,5,12,14,16,18,25–28,39,41,43,45,46,49,52–54,57和18篇9,12,13,17–19,22,24,27,30,31,34–37,41,47,50相关文章。但是,手术指南和造口构建类别中的大多数文章是重叠的。文献中还充分描述了三个总体类别中的另外11个风险因素(即,术前造口部位标记[术前指南]、患者术后培训[护理指南]、造口周围身体轮廓、个体皮肤特性和状况、他/她的用药/治疗状态、年龄[残疾]、自我意识/自我护理能力、造口管理技能、造口产品的范围和类型、产品的粘附性能和产品佩戴时间),证据来自3至9项研究。

模型中确定的24个基于共识的风险因素中,只有5个缺乏文献证据。这些因素包括:系统层面的因素,例如获得适当的造口产品类型和数量,以及社会对患有此类疾病的患者的看法;来自家庭或社交网络的个人层面的支持;以及产品层面的因素,例如适合身体轮廓、易于应用或移除造口产品。虽然这些因素没有文献证据支持,但它们被认为具有相关性,并根据专家意见和经验得到国际认可。结合仅有1-2项研究支持的5个风险因素子类别(即,获得出院后计划29,38、医疗保健专业人员教育水平11、个人收入/生活水平44、造口产品与造口形状的契合度9,41以及造口产品的过滤性能和容量62),这些是特别需要进一步研究的领域。

我们的目标是将PSC的风险因素模型用作造口护理日常实践中的工具。一些已确定的风险因素可以在患者出院的早期阶段解决,并且可以使患者通过自我护理的试错法避免他们可能面临的一些初始问题。该模型广泛和地理多样性的开发过程使其可以合理地推广到造口患者群体,并允许根据区域进行适当的实施变化。因此,该模型有可能被纳入医疗保健专业人员评估、干预和监测指南中,以促进采用整体方法来确保造口患者的造口周围皮肤健康和生活质量。

结论

开发PSC风险因素模型的目的是探索导致PSC的现有基于证据和经验的风险,目的是提供一种有效的评估方法来指导造口护理的个体化建议和决策。目的是帮助预防PSC。

通过进行全面的文献研究并与造口护理领域的专家合作,我们获得了坚实的知识基础,并在此基础上开发了PSC的风险因素模型。

通过个体化的风险因素评估,包括生活质量、造口周围身体轮廓和造口周围皮肤,辅以专业的整体判断,应避免试错法,以免对个体患者的健康和生活质量造成严重的负面影响。

利益冲突与资金来源

本文得到了Coloplast A/S的支持。Anne Steen Hansen、Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft、Zenia Størling和Lene Feldskov Nielsen在开发模型和撰写稿件时受雇于Coloplast A/S。

Lina Martins、Jane Fellows、Birgitte Dissing-Andersen、Gillian Down、David Voegeli、Tonny Karlsmark和 Gregor Jemec是Coloplast皮肤专家小组的成员,并因参加不同的Coloplast咨询委员会而获得酬金。他们没有因参与本出版物而获得报酬。

所有作者都参与了稿件的撰写、审阅和编辑,给予了最终批准并同意对文章的各个方面负责。Anne Steen Hansen和Lene Feldskov Nielsen负责PSC的风险因素模型,Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft负责文献综述。参考文献由Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft和Lene Feldskov Nielsen独立筛选。

致谢

感谢COF和Coloplast皮肤专家小组的成员,他们参与讨论并分享了他们关于PSC的宝贵经验Å\Å\感谢Gemma Gascón Guitart,在研究一开始参与了研讨会,并与进行文献检索的信息专家Jette Brandt(M.L.I Sc,图书馆和信息科学)合作开始文献检索,感谢Louise C. Rosenberg Christ博士和Kaushik Sengupta博士(Larix A/S,Copenhagen,丹麦)提供编辑和医学写作服务,该项工作由Coloplast A/S资助。

附录1.支持已确定风险因素的文献。

Author(s)

Anne Steen Hansen*

BSc/MA, ET

Coloplast A/S, Holtedam 1, 3050 Humlebæk, Denmark

Email dkasn@coloplast.com

Cecilie Jæger Leidesdorff Bechshøft

PhD

Coloplast A/S, Holtedam 1, 3050 Humlebæk, Denmark

Lina Martins

NSWOC, BSc/MSc

London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario, Canada

Jane Fellows

MSN, RN, CWOCN-AP

Duke University Health System, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Birgitte Dissing Andersen

RN, Diploma in Nursing Management, ET

The Stoma Clinic, Herlev Hospital, Herlev, Denmark

Gillian Down

Diploma in Cancer Nursing, EBN (continence and stoma care), Reg. Midwife, RN, NHS

North Somerset and South Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group, Bristol, UK

Tonny Karlsmark

MD, Sc

Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark

Gregor Jemec

MD, Sc

Roskilde Hospital, Roskilde, Denmark

David Voegeli

PhD, BSc, RN

University of Winchester, Winchester, Hampshire, UK

Zenia Størling

PhD

Coloplast A/S, Holtedam 1, 3050 Humlebæk, Denmark

Lene Feldskov Nielsen

MSc

Coloplast A/S, Holtedam 1, 3050 Humlebæk, Denmark

* Corresponding author

References

- Claessens I, Probert R, Tielemans C, et al. The Ostomy Life Study: the everyday challenges faced by people living with a stoma in a snapshot. Gastrointest Nurs 2015;13(5):18–25. doi:10.12968/gasn.2015.13.5.18

- Coloplast. Perception of leakage: data from the Ostomy Life Study 2019. In Press.

- Herlufsen P, Olsen AG, Carlsen B, et al. Study of peristomal skin disorders in patients with permanent stomas. Br J Nurs 2006;15(16):854–862. doi:10.12968/bjon.2006.15.16.21848

- Nybæk H, Knudsen DB, Laursen TN, Karlsmark T, Jemec GBE. Skin problems in ostomy patients: a case-control study of risk factors. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2009;89(1):64–67. doi:10.2340/00015555-0536

- Voegeli D, Karlsmark T, Eddes EH, et al. Factors influencing the incidence of peristomal skin complications: evidence from a multinational survey on living with a stoma. Gastroint Nurs 2020;18(Supplement 4):S31-S38.

- James-Reid S, Bain K, Hansen AS, Vendelbo G, Droste W, Colwell J. Creating consensus-based practice guidelines with 2000 nurses. Br J Nurs 2019;28(22):S18-S25. doi:10.12968/bjon.2019.28.22.S18

- Bain KA, Bain M. Clinical preventative-based best practices to reduce the risk of peristomal skin complications – an international consensus report. Publication in progress.

- Dearholt SL and Dang D. (2012) Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice: Models and Guidelines. 2nd Edition, Sigma Theta Tau International, Indianapolis, IN.

- Colwell JC, McNichol L, Boarini J. North America wound, ostomy, and continence and enterostomal therapy nurses current ostomy care practice related to peristomal skin issues. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(3):257–261. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000324

- Cressey BD, Belum VR, Scheinman P, et al. Stoma care products represent a common and previously underreported source of peristomal contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2017;76(1):27–33. doi:10.1111/cod.12678

- Foa C, Bisi E, Calcagni A, et al. Infectious risk in ostomy patient: the role of nursing competence. Acta Biomed 2019;90(11-S):53–64. doi:10.23750/abm.v90i11-S.8909

- Persson E, Berndtsson I, Carlsson E, Hallen AM, Lindholm E. Stoma-related complications and stoma size: a 2-year follow up. Colorectal Di 2010;12(10):971–6. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01941.x

- Almosallam OI, Aseeri A, Shanafey SA. Outcome of loop versus divided colostomy in the management of anorectal malformations. Ann Saudi Med 2016;36(5):352–355. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2016.352

- Arolfo S, Borgiotto C, Bosio G, Mistrangelo M, Allaix ME, Morino M. Preoperative stoma site marking: a simple practice to reduce stoma-related complications. Tech Coloproctol 2018;22(9):683–687. doi:10.1007/s10151-018-1857-3

- Arumugam PJ, Bevan L, Macdonald L, et al. A prospective audit of stomas-analysis of risk factors and complications and their management. Colorectal Dis 2003;5:49–52.

- Baykara ZG, Demir SG, Karadag A, et al. A multicenter, retrospective study to evaluate the effect of preoperative stoma site marking on stomal and peristomal complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2014;60(5):16–26.

- Carannante F, Masciana G, Lauricella S, Caricato M, Capolupo GT. Skin bridge loop stoma: outcome in 45 patients in comparison with stoma made on a plastic rod. Int J Colorectal Dis 2019;34(12):2195–2197. doi:10.1007/s00384-019-03415-x

- Carbonell BB, Treter C, Staccini G, MajnoHurst P, Christoforidis D. Early peristomal complications: detailed analysis, classification and predictive risk factors. Ann Ital Chir 2020;91(1).

- Dziki L, Mik M, Trzcinski R, et al. Evaluation of the early results of a loop stoma with a plastic rod in comparison to a loop stoma made with a skin bridge. Polski Przeglad Chirurgiczny 2015;87(1):31–34.

- Fagundes RB, Cantarelli JC, Fontana K, Motta GL. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and peristomal infection: an avoidable complication with the use of a minimum skin incision. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2011;21(4):275–277.

- Folguera-Arnau M, Gutiérrez-Vilaplana JM, González-María E, et al. Implementation of best practice guidelines for ostomy care and management: care outcomes. Enfermería Clínica (English edition) 2020;30(3):176–184. doi:10.1016/j.enfcle.2019.10.008

- Hayashi K, Kotake M, Hada M, et al. Laparoscopic versus open stoma creation: a retrospective analysis. J Anus Rectum Colon 2017;1(3):84–88. doi:10.23922/jarc.2016-014

- Karadag A, Mentes BB, Üner A, Irkörkücü O, Ayaz S, Özkan S. Impact of stomatherapy on quality of life in patients with permanent colostomies or ileostomies. Int J Colorectal Dis 2003;18:234–238.

- Klink CD, Lioupis K, Binnebosel M, et al. Diversion stoma after colorectal surgery: loop colostomy or ileostomy? Int J Colorectal Dis 2011;26(4):431–6. doi:10.1007/s00384-010-1123-2

- Martins L, Samai O, Fernandez A, Urquhart M, Hansen AS. Maintaining healthy skin around an ostomy: peristomal skin disorders and self-assessment. Gastrointest Nurs 2011;9(2)(Supplement):9–13.

- Nagano M, Ogata Y, Ikeda M, Tsukada K, Tokunaga K, Iida S. Peristomal moisture-associated skin damage and independence in pouching system changes in persons with new fecal ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(2):137–142. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000491

- Parmar KL, Zammit M, Smith A, et al. A prospective audit of early stoma complications in colorectal cancer treatment throughout the Greater Manchester and Cheshire colorectal cancer network. Colorectal Dis 2011;13(8):935–8. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02325.x

- Pittman J, Rawl SM, Schmidt CM, et al. Demographic and clinical factors related to ostomy complications and quality of life in veterans with an ostomy. JWOCN 2008;35(5):493–503.

- Robatmily A, Anboohi Z, Shirinabadi Farahani A, Nasiri M. Effect of Providing Ostomy Care Education to Mothers of Neonates with Peristomal Skin Complications. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2018;27(3):6-10. doi:10.21859/ANM-027033

- Sakai Y, Nelson H, Larson D, Maidl L, Young-Fadok T, Ilstrup D. Temporary transverse colostomy vs loop ileostomy in diversion. Arch Surg 2001;136:338–324.

- Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Boetto R, Pozza A, Sadocchi L, Angriman I. Diverting loop ileostomy after restorative protocolectomy: predictors of poor outcome and poor quality of life. Colorectal Dis 2009;12:914–920.

- Shiraishi T, Nishizawa Y, Nakajima M, et al. Risk factors for the incidence and severity of peristomal skin disorders defined using two scoring systems. Surg Today 2020;50(3):284–291. doi:10.1007/s00595-019-01876-9

- Stokes AL, Tice S, Follett S, et al. Institution of a preoperative stoma education group class decreases rate of peristomal complications in new stoma patients. JWOCN 2017;44(4):363–367. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000338

- Sun X, Han H, Qiu H, et al. Comparison of safety of loop ileostomy and loop transverse colostomy for low-lying rectal cancer patients undergoing anterior resection: a retrospective, single institution, propensity score-matched study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2020. Journal of BUON: Official Journal of the Balkan Union of Oncology 24(1): 123-129; 2019 ISSN/ISBN: 1107-0625 PMID: 30941960 doi:10.1111/ajco.13322

- Sung YH, Kwon I, Jo S, Park S. Factors affecting ostomy-related complications in Korea. JWOCN 2010;37(2):166–172.

- Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Bando T, Chohno T, Sasaki H, Horio Y. Is an ostomy rod useful for bridging the retraction during the creation of a loop ileostomy? A randomized control trial. World J Surg 2017;41(8):2128–2135. doi:10.1007/s00268-017-3978-7

- Wu X, Lin G, Qiu H, Xiao Y, Wu B, Zhong M. Loop ostomy following laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Med Res 2018;23(1):24. doi:10.1186/s40001-018-0325-x

- Zhou H, Ye Y, Qu H, Zhou H, Gu S, Wang T. Effect of ostomy care team intervention on patients with ileal conduit. JWOCN 2019;46(5):413–417. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000574

- Bourgois M, Evers G, Filez L. Satisfaction of ileostomy and colostomy patients with their ostomy collection devices. WCET J 2001;21(3):16–20.

- Bulkley JE, McMullen CK, Grant M, Wendel C, Hornbrook MC, Krouse RS. Ongoing ostomy self-care challenges of long-term rectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2018;26(11):3933–3939. doi:10.1007/s00520-018-4268-0

- Carlsson E, Fingren J, Hallen AM, Petersen C, Lindholm E. The prevalence of ostomy-related complications 1 year after ostomy surgery: a prospective, descriptive, clinical study. Ostomy Wound Manage 2016;62(10):34–48.

- Cowin C, Redmond C. Living with a parastomal hernia. Gastrointest Nurs 2012;10(1):16–24.

- Goldstine J, Hees RV, de Vorst DV, Skountrianos G, Nichols T. Factors influencing health-related quality of life of those in the Netherlands living with an ostomy. Br J Nurs 2019;28(22)(Stoma supplement):S10-S17.

- Gooszen AW, Geelkerken RH, Hermans J, Lagaay MB, Gooszen HG. Quality of life with a temporary stoma. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43(5):650–655.

- Jayarajah U, Samarasekara AM, Samarasekera DN. A study of long-term complications associated with enteral ostomy and their contributory factors. BMC Res Notes 2016;9(1):500. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2304-z

- Lin Z, Yu W, Shi J, Chen Q, Tan S, Li N. Temporary decompression in critically ill patients: retrospective comparison of ileostomy and colostomy. Hepato-Gastroenterol 2014;64:647–651.

- Lindholm E, Persson E, Carlsson E, Hallen AM, Fingren J, Berndtsson I. Ostomy-related complications after emergent abdominal surgery: a 2-year follow-up study. JWOCN 2013;40(6):603–10. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e3182a9a7d9

- Mahjoubi B, Moghimi A, Mirzaei R, Bijari A. Evaluation of the end colostomy complications and the risk factors influencing them in Iranian patients. Colorectal Dis 2005;7(6):582–7. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00878.x

- Manzenreiter L, Spaun G, Weitzendorfer M, et al. A proposal for a tailored approach to diverting ostomy for colorectal anastomosis. Minerva Chirurgica 2018;73(1):29–35.

- Miyo M, Takemasa I, Ikeda M, et al. The influence of specific technical maneuvers utilized in the creation of diverting loop-ileostomies on stoma-related morbidity. Surg Today 2017;47(8):940–950. doi:10.1007/s00595-017-1481-2

- Park S, Lee YJ, Oh DN, Kim J. Comparison of standardized peristomal skin care and crusting technique in prevention of peristomal skin problems in ostomy patients. J Korean Acad Nurs 2011;41(6):814–20. doi:10.4040/jkan.2011.41.6.814

- Pearson R, Knight SR, Ng JCK, Robertson I, McKenzie C, Macdonald AM. Stoma-related complications following ostomy surgery in 3 acute care hospitals: a cohort study. JWOCN 2020;47(1):32–38. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000605

- Pittman J, Bakas T, Ellett M, Sloan R, Rawl SM. Psychometric evaluation of the ostomy complication severity index. JWOCN 2014;41(2):147–57. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000008

- Salvadalena G, Colwell JC, Skountrianos G, Pittman J. Lessons learned about peristomal skin complications: secondary analysis of the ADVOCATE trial. JWOCN 2020;47(4):357–363. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000666

- Salvadalena GD. The incidence of stoma and peristomal complications during the first 3 months after ostomy creation. JWOCN 2013;40(4):400–6. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e318295a12b

- Shiraishi T, Nishizawa Y, Ikeda K, Tsukada Y, Sasaki T, Ito M. Risk factors for parastomal hernia of loop stoma and relationships with other stoma complications in laparoscopic surgery era. BMC Surg 2020;20(1):141. doi:10.1186/s12893-020-00802-y

- Whiteley I, Sinclair G. A review of peristomal complications after the formation of an ileostomy, colostomy or ileal conduit. WCET J 2010;30(3)

- Al-Niaimi F, Beck M, Almaani N, Samarasinghe V, Williams J, Lyon C. The relevance of patch testing in peristomal dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2012;167(1):103–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10925.x

- Banu T, Talukder R, Chowdhury TK, Hoque M. Betel leaf in stoma care. J Pediatr Surg 2007;42(7):1263–5. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.02.025

- Caroppo F, Brumana MB, Biolo G, Giorato E, Barbierato M, Belloni Fortina A. Peristomal allergic contact dermatitis caused by ostoma pastes and role of Gantrez ES-425. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2019;154(1):1–5. doi:10.23736/S0392-0488.18.05957-6

- Colwell JC, Pittman J, Raizman R, Salvadalena G. A randomized controlled trial determining variances in ostomy skin conditions and the economic impact (ADVOCATE trial). JWOCN 2018;45(1):37–42. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000389

- Klok-Vonkeman SI, Douw G, Janse AJ. Pancaking: an underestimated problem among ostomates. WCET J 2013;33(4):16–25.

- Ratliff CR. Factors related to ostomy leakage in the community setting. JWOCN 2014;41(3):249–53. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000017

- Welser M, Riedlinger I, Prause U. A comparative study of two-priece ostomy appliances. Br J Nurs 2009;18(9):530–538.

- Martins L, Andersen BD, Colwell J, Down G, Forest-Lalande L, Novakova S, Probert R, Hedegaard CJ, Hansen AS. Challenges faced by people with a stoma: peristomal body profile risk factors and leakage. Br J Nurs. 2022 Apr 7;31(7):376-385. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2022.31.7.376. PMID: 35404660.

- Coloplast. The emotional impact of stoma leakage: data from the Ostomy Life Study 2019. In press.