Volume 43 Number 2

Healing peristomal wounds around retracted stomas with negative-pressure wound therapy: a case series

Jarosław Cwaliński, Jacek Hermann, Tomasz Banasiewicz

Keywords ostomy, Wound care, Negative-pressure wound therapy, hydrofiber dressing, peristomal infection, peristomal leak, retraction

For referencing Cwaliński J, Hermann J & Banasiewicz T. Healing peristomal wounds around retracted stomas with negative-pressure wound therapy: a case series. WCET® Journal 2023;43(2):29-34

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.2.29-34

Submitted 16 February 2022

Accepted 29 April 2022

Abstract

One method for treating a retracted stoma is a vacuum dressing that cleans the wound and protects against intestinal leakage. This case series describes the use of an integrated, single-use negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) dressing to treat retracted stomas as an alternative to other noninvasive remedies. The report includes seven patients who were hospitalized in the authors’ surgical department from 2019 to 2020. All patients developed severe peristomal infection that failed to respond to local treatment with proper ostomy appliances or specialist dressings. After cleaning each wound and removing necrotic lesions, the authors applied a single-use hydrofiber NPWT dressing to each patient. The dressing was changed every 2 to 5 days, depending on the effects of the therapy. The stoma orifice was covered with a bag with two-piece ostomy systems. The peristomal wound healed in all cases and leakage was eliminated. The mean time of treatment was 14 days (range, 10-21 days), and the vacuum dressings were changed an average of four times (range, 3-7). None of the patients required a stoma translocation or other additional surgery. Three patients received systemic IV antibiotic therapy to treat general infection. Single-use NPWT dressings protect peristomal wounds from bowel leakage and do not hinder the application of stoma bags. This system, similar to standard NPWT devices, effectively protects infected stomas from retraction.

Introduction

An ostomy is a communication between the lumen of a bowel loop and the abdominal wall; stoma creation is one of the most basic procedures of colorectal surgery. It is performed on the large or small bowel to treat malignant, inflammatory, or vascular diseases and following bowel injuries. Colorectal cancer is the most common indication, comprising up to 75% of cases.1,2 Ostomies are performed for almost 100,000 patients per year in the US, and the procedure reduces major morbidity and mortality.3

However, there is a relatively high rate of ostomy-related morbidity. The early complications, such as peristomal infection, skin irritation, ischemia, and retraction continue to challenge surgeons.2 Ostomy retraction causes continuous leakage of bowel contents into the subcutaneous tissue; this can be followed by severe necrosis and infection of the tissues surrounding the ostomy, with ostomy detachment occurring in some cases.4,5 Although most of the aforementioned complications are treated with proper ostomy appliances and specialist dressings, severe complications can require advanced modalities such as negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT), which offers effective, continuous evacuation of infectious effusion and pus. However, although ostomy salvage using standard NPWT devices has been described, to the authors’ knowledge there are no extant reports about single-use NPWT systems. Accordingly, this case series described the treatment of peristomal wounds and stoma retraction prevention with integrated single-use vacuum dressings.

Methods

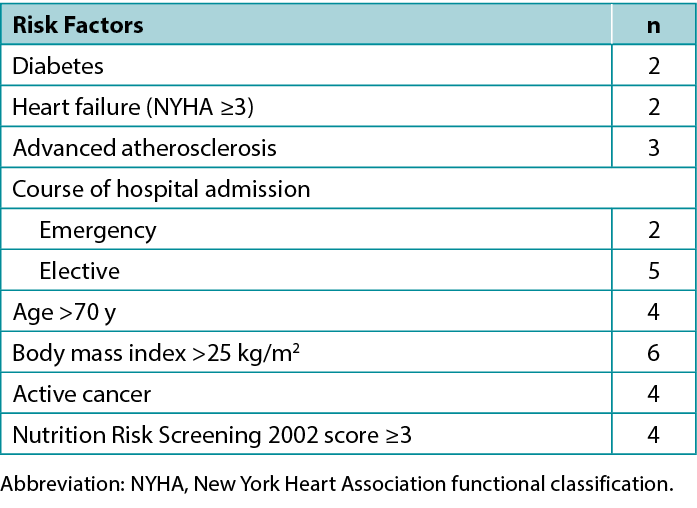

A preliminary and prospective study was carried out from 2019 to 2020 on a group of seven patients with early retracted ostomy and peristomal wounds. The series included four men and three women whose characteristics are presented in Table 1.

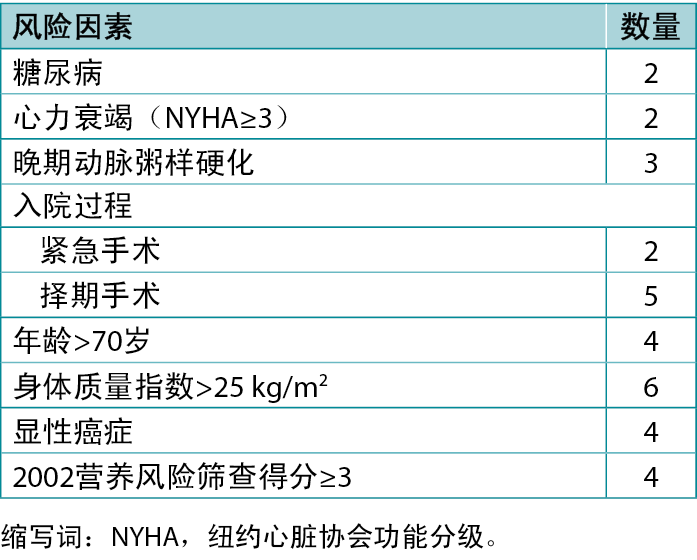

Table 1. Patient characteristics (N = 7)

All of the patients had a moderate or severe peristomal infection that failed to respond to local treatment with proper ostomy appliances and specialist dressings. In addition, preoperative risk factors for healing dysfunction were observed in the study group, including emergency surgery, malnutrition, steroid use, active inflammatory bowel disease, and other comorbidities (Table 2). All patients received oral immunomodulatory nutrition beginning the second day after surgery, and four of the patients were also fed intravenously during the four postoperative days. Further, three patients required systemic antibiotic therapy due to septic complications.

Table 2. Preoperative risk factors for surgical site infection

Ethics and Consent

Negative-pressure wound therapy is widely approved for medical therapy and the aim of the study was to adapt this method to the treatment of stoma-related complications. Therefore, the ethics committee of the author’s institution concluded that there was no need to issue a separate consent for this study. However, due to this atypical application of single-use NPWT, the authors obtained informed consent for the therapy from each patient, as well as written approval to publish images and case details.

Surgical Technique

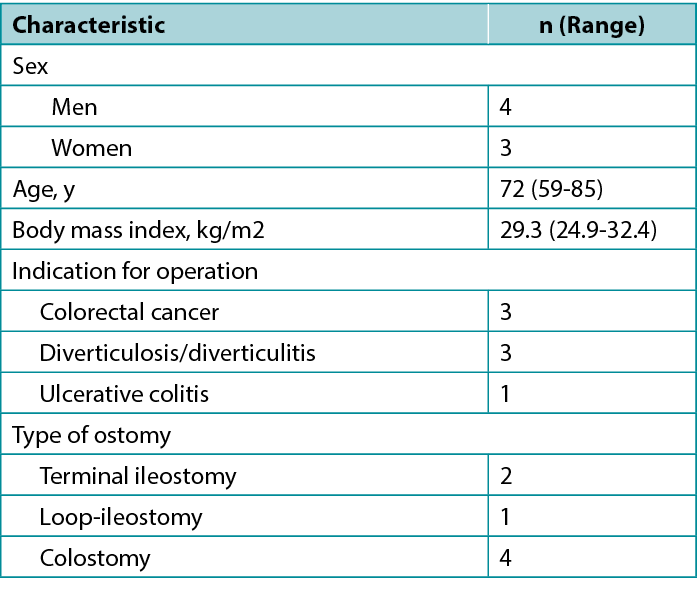

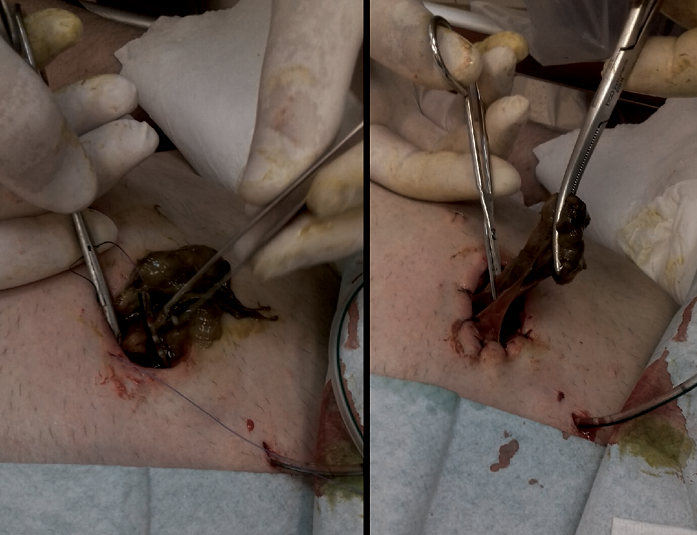

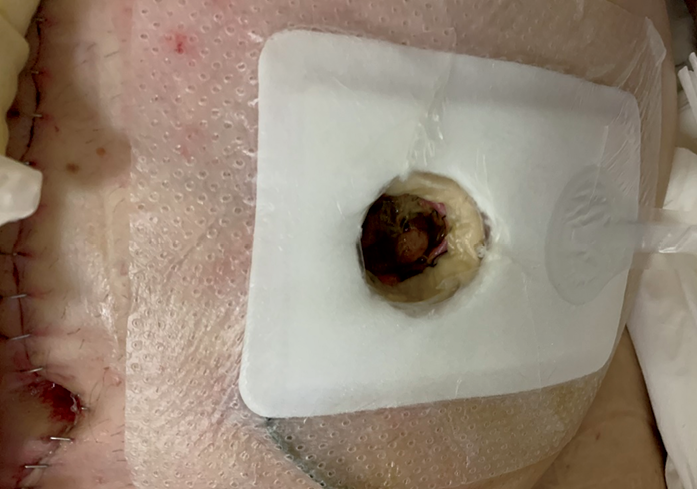

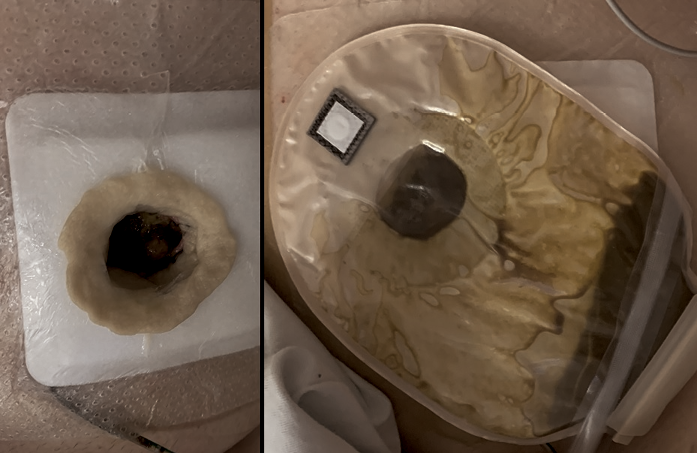

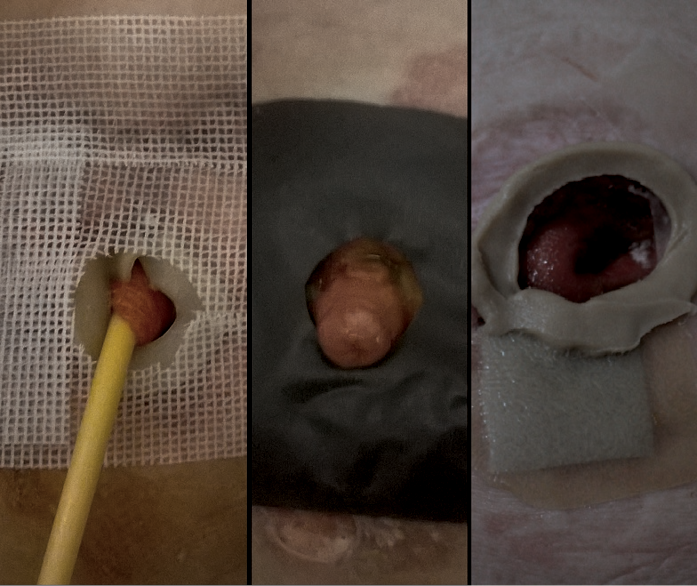

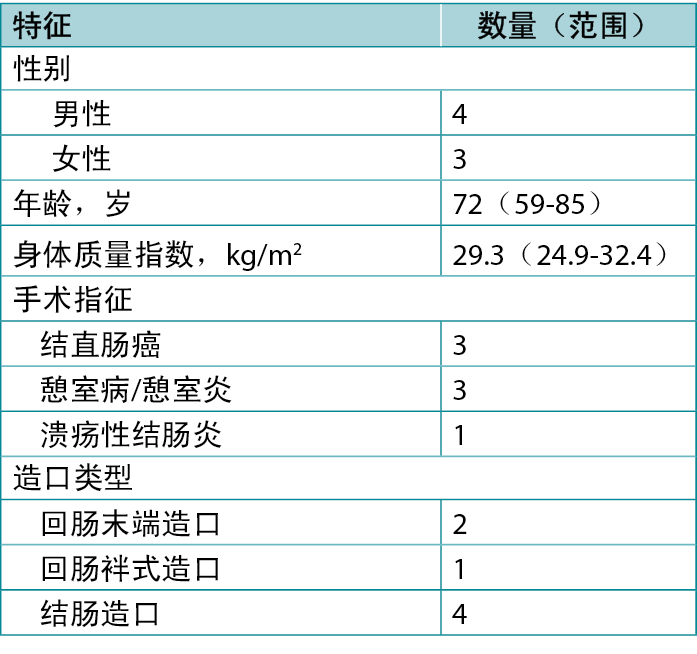

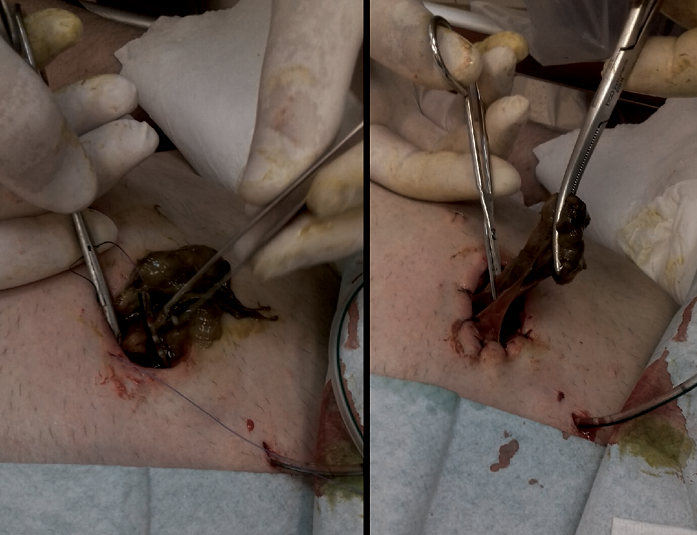

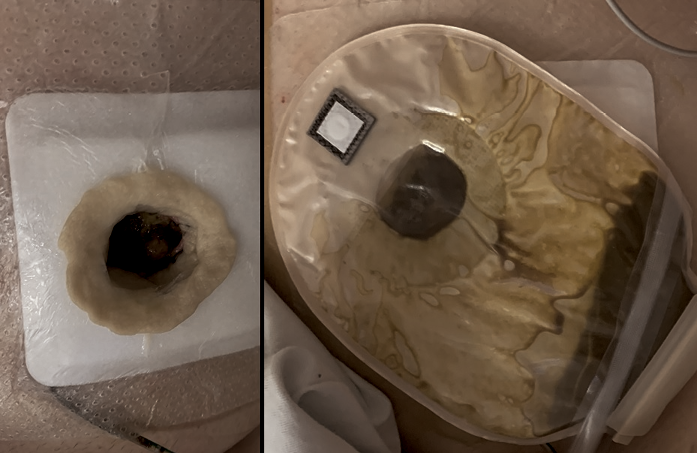

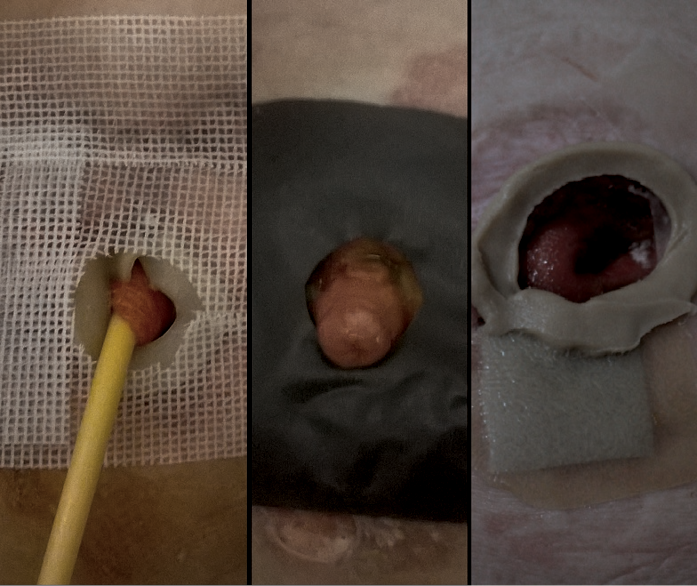

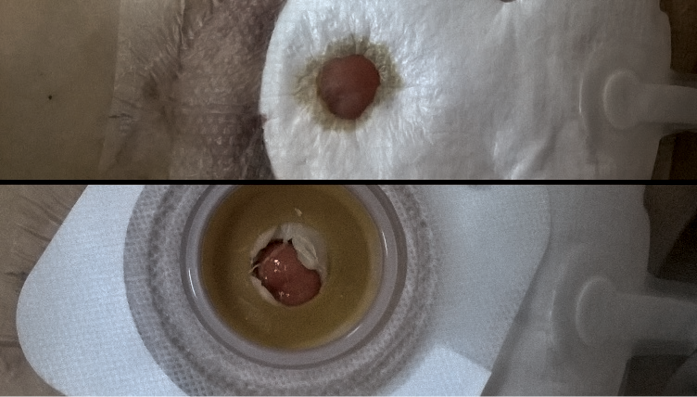

First, the authors debrided the infected wound surrounding the retracted ostomy and, if necessary, placed a drain derived from a separate cut given any persistent leakage of the bowel contents into the surgical site (Figure 1). Next, they washed the wound and surrounding skin with disinfectant and applied a carboxymethylated cellulose fiber dressing measuring 15 × 10 cm or 10 × 10 cm (Avelle NPWT System, ConvaTec; or PICO NPWT System, Smith & Nephew; Figure 2). A hole was cut in the dressing to fit the ostomy as well as the wound. The adherence and tightness of the dressings were enhanced with adhesive foil strips placed on the margins (Figure 2). In the next step, a hydrocolloid stoma paste was applied to increase adhesion of the ostomy bag or plate edges (Figure 3). The stoma paste also used to improve the system seal and create a barrier between the stoma contents and the hydrofiber filling of the NPWT dressing. In addition, deep peristomal wound recesses with residual necrosis were filled with silver alginate dressing or silicone open-weave gauze (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Stabilization of retracted ostomy with necrectomy and bowel-to-skin sutures

Figure 2. Peristomal wound after single-use negative pressure wound therapy dressing application

Figure 3. Ostomy bag application during the treatment of a retracted stoma with a negative-pressure wound therapy dressing

Stoma paste fills the space between the edge of the tissues and the dressing (left) ensuring better adhesion of the pouch and protecting against leakage (right)

Figure 4.Peristomal wound with silver alginate dressing or silicone open-weave gauze

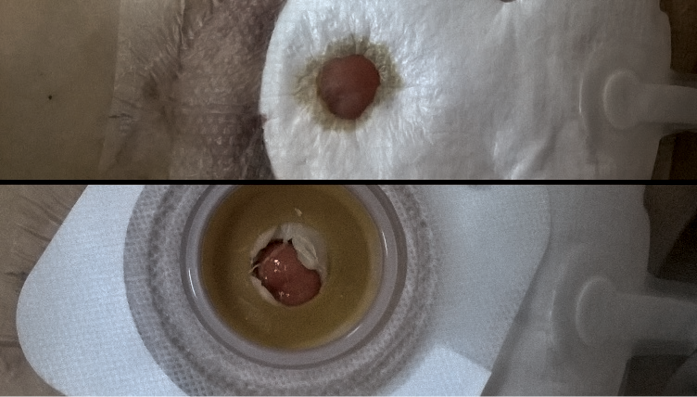

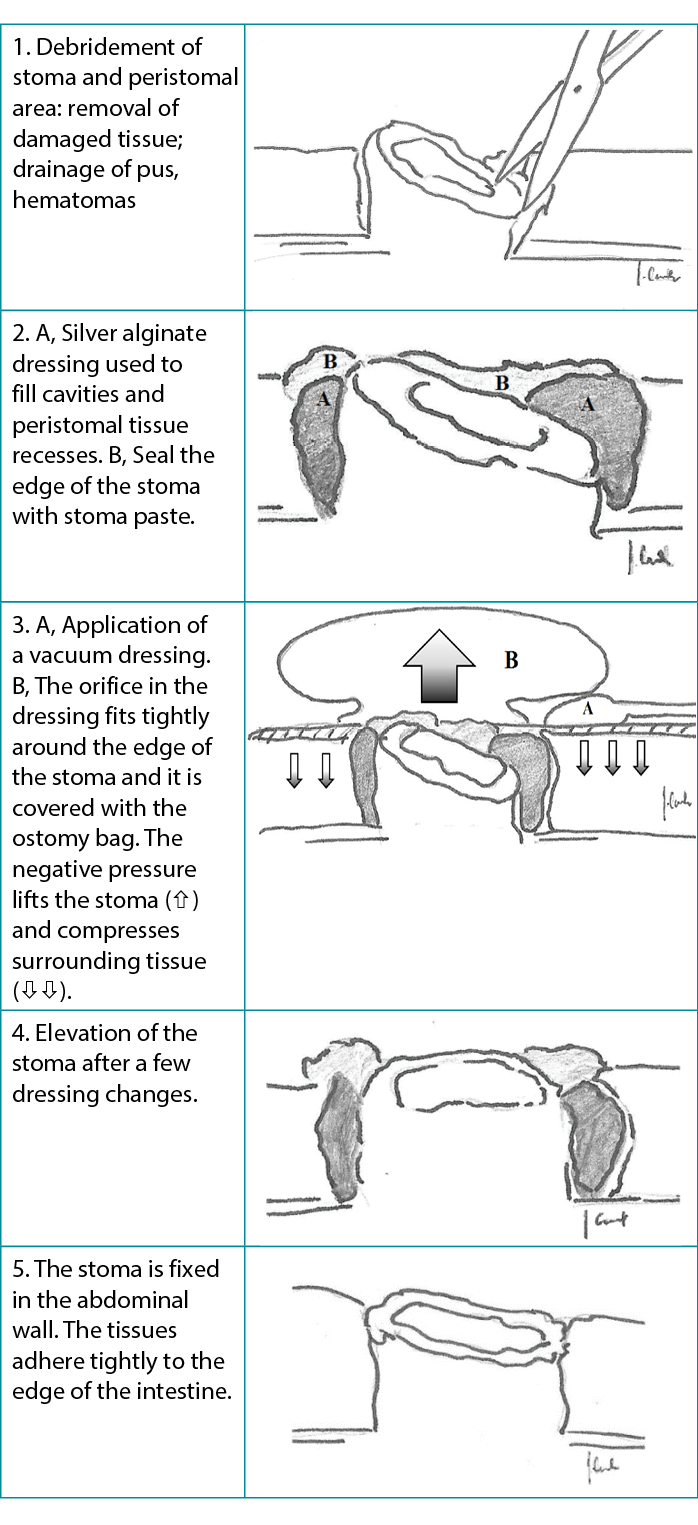

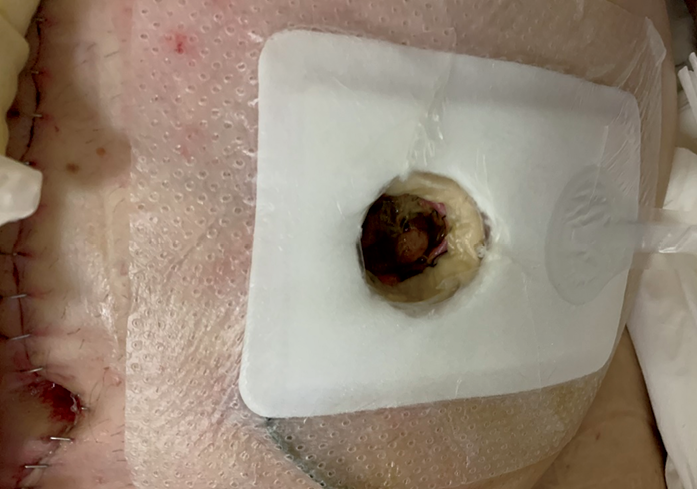

Finally, the port of a negative-pressure generator was attached to the dressing and a stable negative pressure of 80 mm Hg was maintained during the therapy. At each dressing change, any bowel leakage into the wound was controlled and eliminated as needed (Figure 5). The dressings were changed at the beginning of every second day with the use of a one-piece stoma bag. Subsequently, dressings were left in place for 3 to 5 days using two-piece ostomy systems (Figure 6). A summary diagram of the procedure is presented in the Table 3.

Figure 5. Ostomy on day 4 of treatment after second change of vacuum drainage with no bowel contents leakage

Figure 6. One-piece bag applied to ostomy

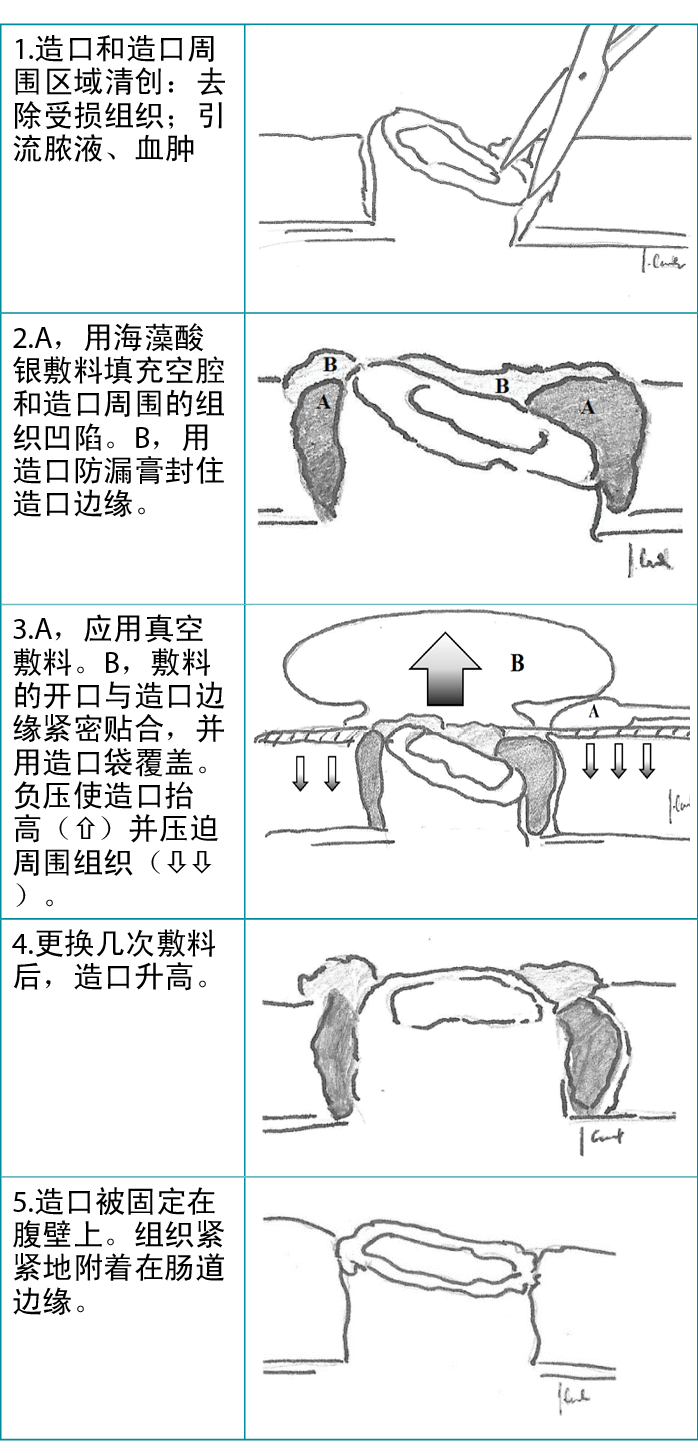

Table 3. Stoma healing: single-use negative-pressure wound therapy dressing removes necrotic tissue and prevents stoma erosion

Results

Patients’ deep, infected peristomal wounds healed and the ostomies were retained in their primary locations. None of the patients required secondary operations. The mean time of treatment was 14 days (range, 10-21 days), and the NPWT was changed an average of four times (range, 3-7). Figure 7 shows a representative treatment effect after four dressing changes. Regular ostomy appliances were used in six patients with terminal ostomy; additional sealing rings were necessary in one patient with loop ostomy. Two patients, one with colostomy and one with ileostomy, received appropriate systemic antibiotic therapy because of elevated inflammatory markers in the serum.

Figure 7. Effect on day 10 of treatment and after four dressing changes

Discussion

The incidence of overall stoma-related complications is reported to be between 10% and 70%.6,7 Hematoma formation, bleeding, ostomy edema, skin irritation with erosion or ulceration, ischemia with necrosis, and early ostomy retraction are the most common complications to occur within 30 days of any procedure, with frequencies ranging from 25% to 34%.1 Although most of these complications resolve spontaneously within a few days or require only conservative medical treatment, patients who develop major complications such as ischemia with necrosis or ostomy retraction usually require secondary surgery because of the threat of severe infection and gastrointestinal tract dysfunction.1,8 Proper surgical technique—displacing the bowel with no tension to the skin surface and suturing it to the pre-planned place—is the most effective way to prevent patients from experiencing complications.

Before elective procedures, a stoma nurse should prepare the location of the stoma, assessing the location of skin folds and scars and considering the patient’s lifestyle and occupation. Typically, the stoma site is designated in standing, lying, and sitting positions. The stoma nurse should also mark an alternative site in case of intraoperative difficulties.9

According to the surgical technique, the stoma should be positioned through the rectus abdominis muscle leaving sufficient gut margin above the skin surface. For an end ostomy, it should be 5 cm for the small intestine and 2 cm for the colon, which allows the stoma to contract to about 2 cm and 0.5 cm after a few months.10 Lack of proper pre-operative preparation may occur in emergency operations, where the rate of morbidity is increasing.11,12

A refractory ostomy may be cause for reoperation, which, in some cases, then increases the risk of additional complications. Avoiding reoperation is extremely important for some patient populations in particular, such as those with cachexia and/or cancer, for whom surgical site infections or other complications may prolong the length of stay and affect chemotherapy. In addition, avoiding reoperation enables the patient to maintain oral nutrition which improves nutrient absorption and the condition of the gut microbiome.12,13

Preventing the continuous leakage of bowel contents into peristomal subcutaneous tissue and enabling the unhindered outflow of bowel contents through the ostomy are the basic therapeutic targets in cases with ostomy complications.11,14 Those targets are met initially with modified stoma appliances in the form of rings, washers, and feet with a concave profile, the aims of which are shape adaptation and leveling the height of the ostomy.15 Vacuum-assisted therapy is recommended as an effective method to treat patients with severely retracted ostomy. Vacuum-assisted dressings consist of a polyurethane foam covered with adhesive foil. A stationary or portable electrical suction pump is attached to the dressing and a stable negative pressure of 50 to 200 mm Hg is maintained during therapy. The objectives of vacuum treatment are to remove tissue exudate, divert bowel contents, reduce edema, and improve blood supply.16,17 The polyurethane foam also removes devitalized and infected tissues and improves lymphatic drainage. Thus, after a few dressing changes, the wound contracts and it is covered with fresh granulation tissue.16,18 The antibacterial mode of action, mostly against Gram-negative bacteria, relies on direct elimination of bacterial cells, followed by local regulation of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic conditions, the effect of which is better antibiotic tissue penetration.19,20

Proper application of vacuum dressings on peristomal wounds with a retracted bowel remnant is challenging because bowel contents can be suctioned into a stoma bag through badly adherent layers of the dressing. It is a priority to isolate the stoma from the wound without secondary tissue damage caused by the vacuum dressing. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary to place an insulating layer between the intestine and the polyurethane foam and use an under pressure between 75 mm Hg and 125 mm Hg.21,22 Close vicinity of the suction port and stoma bag is another drawback of the application. Finally, a patient’s daily life activities may be limited by needing to carry a stationary or portable negative pressure electrical suction pump.23,24 Another important issue remains the long-term outpatient and home-based care with properly selected equipment and qualified personnel. Nurses caring for wounds can successfully carry out vacuum therapy after a few weeks of practical training.25

Applying single-use NPWT dressings can help avoid the aforementioned obstacles. Because single-use NPWT dressings are much thinner than regular polyurethane foam and all the layers (separating, absorbent, and insulating) are integrated into one pack, the dressing thoroughly fills the wound and properly adheres to the ostomy margins. Moreover, this type of vacuum therapy may be left in the wound for up to 7 days, on the condition that it retains its full capacity to absorb exudates. Typically, a portable pump included in the set generates a stable pressure of approximately 80 mm Hg as the surface of a wound decreases and the retracted ostomy is elevated.27,28 Because this system is lightweight, has a silent pump, and requires simple battery changes, it is accepted by patients in both ambulatory settings and at home. In the authors’ experience, telemedicine (eg, iWound; Polmedi) improves the safety of NPWT use in patients’ continued treatment at home.

Conclusions

The use of single-use NPWT dressings combined with properly balanced nutrition and antibiotic therapy is an effective method of treatment for patients with early stoma complications. Single-use NPWT systems are “skin-friendly,” because they do not damage the skin surrounding the ostomy and simultaneously heal the area affected by inflammation or infection. They are inexpensive and easy to use, even in home settings. The authors recommend this treatment method for the management of an early phase retracted ostomy with concomitant peristomal infection.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

采用负压伤口治疗治愈造口周围伤口:一项病例系列研究

Jarosław Cwaliński, Jacek Hermann, Tomasz Banasiewicz

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.2.29-34

摘要

治疗回缩造口的一种方法是使用真空敷料,它可以清洁伤口并防止肠漏。本病例系列介绍了使用一种综合的一次性负压伤口治疗(NPWT)敷料来治疗口缩的造口,作为其他无创疗法的替代方案。本报告包括2019年至2020年在作者所在的外科住院的7名患者。所有患者均出现严重的造口周围感染,使用适当的造口装置或专业敷料进行局部治疗均无效。在清洗每个伤口并清除坏死病灶后,作者为每位患者应用了一次性亲水纤维NPWT敷料。根据治疗效果,每2至5天更换一次敷料。造口的口部用一个带有两件式造口系统的袋子覆盖。所有病例的造口周围伤口均愈合,渗漏也消除了。平均治疗时间为14天(范围为10-21天),真空敷料平均更换4次(范围为3-7次)。患者均不需要进行造口转位或其他额外手术。三名患者接受了全身静脉注射抗生素治疗,以治疗全身感染。一次性NPWT敷料可以保护造口周围伤口免受肠漏的影响,并且不妨碍造口袋的使用。该系统与标准NPWT装置类似,能有效防止受感染的造口回缩。

引言

造口是肠襻腔和腹壁之间的连接;造口术是结直肠外科最基本的手术方式之一。造口术在大肠或小肠上进行,用于治疗恶性、炎症性或血管性疾病以及肠道损伤后的病症。结直肠癌是最常见的适应症,占病例的75%。1,2在美国,每年有近10万名患者接受造口术,该手术可降低主要发病率和死亡率。3

然而,造口相关并发症的发病率相对较高。造口周围感染、皮肤刺激、缺血和回缩等早期并发症继续给外科医生带来挑战。2造口回缩会导致肠内容物不断渗入皮下组织;随后会出现造口周围组织的严重坏死和感染,在某些情况下会出现造口脱离。4,5尽管上述大多数并发症可以通过适当的造口装置和专业敷料进行治疗,但严重的并发症可能需要先进的方法,如负压伤口治疗(NPWT),它可以有效、持续地排出感染性积液和脓液。然而,尽管已经描述了使用标准NPWT装置的造口挽救治疗,但据作者所知,目前尚无关于一次性NPWT系统的报告。因此,本病例系列描述了用综合一次性真空敷料治疗造口周围伤口和预防造口回缩的方法。

方法

2019年至2020年,对一组7名有早期回缩造口和造口周围伤口的患者进行了一项初步前瞻性研究。该病例系列包括四名男性和三名女性,其特征见表1。

表1.患者特征(n=7)

所有患者均出现中度至重度造口周围感染,使用适当的造口装置或专业敷料进行局部治疗均无效。此外,研究组中还观察到愈合功能障碍的术前风险因素,包括紧急手术、营养不良、类固醇的使用、活动性炎症性肠病和其他合并症(表2)。所有患者从术后第二天开始接受口服免疫调节营养,其中四名患者在术后4天内还接受了静脉营养输注。此外,有三名患者因败血症并发症而需要全身抗生素治疗。

表2.手术部位感染的术前风险因素

伦理与知情同意

负压伤口治疗被广泛批准用于医学治疗,本研究旨在将这种方法应用于造口相关并发症的治疗。因此,作者所在机构的伦理委员会得出结论,本研究无需另行签署知情同意书。然而,由于一次性NPWT的这种非典型应用,作者获得了每位患者对治疗的知情同意,并获得了发表图像和病例细节的书面批准。

手术方法

首先,作者对回缩造口周围的受感染伤口进行清创,如果肠内容物持续渗漏到手术部位,则在必要时将引流管从一个单独的切口引出(图1)。接下来,用消毒剂清洗伤口和周围的皮肤,并使用尺寸为15Å~10厘米或10Å~10厘米的羧甲基纤维素敷料(Avelle NPWT系统,ConvaTec;或PICO NPWT系统,Smith & Nephew;图2)。在敷料上开一个洞,以适应造口和伤口形状。通过在边缘放置粘性箔条来増强敷料的粘附性和紧密性(图2)。下一步中,使用水胶体造口防漏膏来増加造口袋或造口板边缘的粘性(图3)。造口防漏膏还用于改善系统的密封性,并在造口内容物和NPWT敷料的亲水性纤维填充物之间形成一道屏障。此外,用海藻酸银敷料或硅酮稀织纱布填充有残留坏死的深层组织周围伤口凹陷处(图4)。

图1.通过坏死物切除术和肠-皮肤缝合来稳定回缩的造口

图2.应用一次性负压伤口治疗敷料后的造口周围伤口

图3.在用负压伤口治疗敷料治疗回缩造口时应用造口袋

造口防漏膏填充了组织边缘和敷料之间的空间(左),确保造口袋有更好的粘性并防止渗漏(右)

图4.用海藻酸银敷料或硅酮稀织纱布包扎的造口周围伤口

最后,将负压发生器的端口连接到敷料上,在治疗期间保持80 mmHg的稳定负压。在每次更换敷料时,根据需要控制和消除任何渗入伤口的肠漏(图5)。使用一件式造口袋,每隔一天在当天的开始时间更换敷料。随后,使用两件式造口系统将敷料留在原位3至5天(图6)。该过程的概要图见表3。

图5.治疗第4天在第二次更换负压引流后的造口,无肠内容物渗漏

图6.应用于造口的一件式造口袋

表3.造口愈合:一次性负压伤口治疗敷料可去除坏死组织,防止造口糜烂

结果

患者的深部受感染造口周围伤口愈合,造口被保留在原位置。患者均不需要二次手术。平均治疗时间为14天(范围为10-21天),NPWT平均更换4次(范围为3-7次)。更换敷料四次后的代表性治疗效果见图7。六名末端造口术患者使用了常规造口装置;一名袢式造口术患者需要使用额外的密封环。两名患者,一名结肠造口术患者和一名回肠造口术患者,因为血清中的炎症标志物升高而接受了适当的全身抗生素治疗。

图7.治疗第10天及四次更换敷料后的效果

讨论

据报告,造口相关并发症的总体发生率为10%-70%。6,7血肿形成、出血、造口水肿、皮肤刺激伴糜烂或溃疡、缺血伴坏死以及早期造口回缩是任何手术后30天内最常见的并发症,发生率为25%-34%。1虽然这些并发症大多数会在几天内自然消退或只需要保守治疗,但由于存在严重感染和胃肠道功能障碍的威胁,出现缺血伴坏死或造口回缩等重大并发症的患者通常需要二次手术。1,8适当的手术方法Å\Å\在不牵拉皮肤表面的情况下将肠道移位并将其缝合到预先计划的位置Å\Å\是防止患者出现并发症最有效的方法。

择期手术前,造口护士应准备好造口的位置,评估皮肤褶皱和疤痕的位置,并考虑病人的生活方式和职业。通常情况下,造口部位在站立、卧位和坐位时指定。造口护士还应标记一个替代部位,以防术中出现困难。9

根据手术方法,造口应通过腹直肌定位,在皮肤表面上方留出足够的肠道边缘。对于末端造口术,小肠的造口长度应为5厘米,结肠应为2厘米,这样可以允许造口在几个月后收缩到大约2厘米和0.5厘米。10在紧急手术中,缺乏适当的术前准备可能导致其发病率増加。11,12

难治性造口可能导致再次手术,在某些情况下,这会増加其他并发症的风险。避免再次手术对某些患者群体尤其重要,如患有恶病质和/或癌症的患者,手术部位感染或其他并发症可能会延长住院时间并影响化疗。此外,避免再次手术使患者能够维持口服营养,从而改善营养吸收和肠道菌群状况。12,13

防止肠内容物持续渗漏到造口周围的皮下组织,并使肠内容物通过造口无阻碍地流出,是造口并发症病例的基本治疗目标。11,14这些目标最初是通过改良的造口装置来实现的,该装置包括造口环、垫圈和具有凹形轮廓的脚,其目的是适应形状并调平造口高度。15建议将真空辅助治疗作为治疗造口严重回缩患者的有效方法。真空辅助敷料由覆盖有粘性箔条的聚氨酯泡沫组成。将一个固定式或便携式电动抽吸泵连接到敷料上,在治疗期间保持50 mmHg至200 mmHg的稳定负压。真空治疗的目的是去除组织渗出液,转移肠道内容物、减轻水肿并改善血液供应。16,17聚氨酯泡沫还可以去除失活和感染的组织,改善淋巴引流。因此,在更换几次敷料后,伤口就会收缩,并被新鲜的肉芽组织所覆盖。16,18抗菌的作用方式(主要是针对革兰氏阴性菌)依靠直接消除细菌细胞,然后对药效学和药代动力学条件进行局部调节,其效果是抗生素的组织渗透性更好。19,20

在有回缩肠残余物的造口周围伤口上正确应用真空敷料具有挑战性,因为肠内容物可能会通过粘附性较差的敷料层被吸入造口袋。首要任务是将造口与伤口隔离,避免真空敷料造成二次组织损伤。因此,绝对有必要在肠道和聚氨酯泡沫之间放置一个绝缘层,并使用75 mmHg和125 mm Hg之间的压力。21,22 靠近抽吸口和造口袋是该应用的另一个缺点。最后,由于需要携带固定式或便携式负压电动抽吸泵,患者的日常生活活动可能会受到限制。23,24另一个重要的问题仍然是长期的门诊和家庭护理,并适当选择设备和合格人员。护理伤口的护士在需要经过几周的实践培训后才可以成功地进行真空治疗。25

应用一次性NPWT敷料可以帮助避免上述障碍。由于一次性NPWT敷料比普通的聚氨酯泡沫薄得多,而且所有的层(分离层、吸收层和绝缘层)都集成在一个包装中,敷料能完全填满伤口并正确地粘附在造口边缘。此外,在保持充分吸收渗出液的能力的条件下,这种类型的真空治疗可以在伤口中保留长达7天。通常情况下,随着伤口表面缩小和缩回的造口升高,套件中包含的便携式泵会产生约80 mmHg的稳定压力。27,28 因为该系统重量轻,采用静音泵,且仅需要简单的电池更换,它在门诊和家庭环境都被患者所接受。根据作者的经验,远程医疗(如iWound;Polmedi)可以提高患者在家中继续治疗时使用NPWT的安全性。

结论

使用一次性NPWT敷料,并结合适当的均衡营养和抗生素治疗,是治疗早期造口并发症患者的有效方法。一次性NPWT系统是Åg皮肤友好型Åh,因为它不损害造口周围的皮肤,同时可以治愈受炎症或感染影响的区域。它们价格低廉,易于使用,对于家庭环境而言也是如此。作者推荐将这种治疗方法用于处理伴有造口周围感染的早期回缩造口。

利益冲突声明

作者声明无利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Jarosław Cwaliński*

MD, PhD

Jacek Hermann

MD, PhD

Tomasz Banasiewicz

MD, PhD

* Corresponding author

In the Department of General, Endocrinological Surgery and Gastroenterological Oncology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland, Jaroslaw Cwalinski, MD, PhD and Jacek Hermann, MD, PhD are Senior Assistants and Tomasz Banasiewicz, MD, PhD, is Professor and Head of Clinic.

References

- Ambe PC, Kurz NR, Nitschke C, Odeh SF, Möslein G, Zirngibl H. Intestinal ostomy. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2018; 16;115(11):182-7.

- Malik T, Lee MJ, Harikrishnan AB. The incidence of stoma related morbidity - a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2018;100(7):501-8.

- Goldberg M, Aukett LK, Carmel J, et al. Management of the patient with a fecal ostomy: best practice guideline for clinicians. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2010;37:596–8.

- Kann BR. Early stomal complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2008;21(1):23-30.

- Duchesne JC, Wang Y, Weintraub SL, Boyle M, Hunt JP. Stoma complications: a multivariate analysis. Am Surg 2002;68:961–6.

- Robertson I, Leung E, Hughes D, et al. Prospective analysis of stoma-related complications. Colorectal Dis 2005;7(3):279-85.

- Sheetz KH, Waits SA, Krell RW, et al. Complication rates of ostomy surgery are high and vary significantly between hospitals. Dis Colon Rectum 2014;57(5):632-7.

- Beraldo S, Titley G, Allan A. Use of w-plasty in stenotic stoma: a new solution for an old problem. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:715–6.

- Whitehead A, Cataldo PA. Technical considerations in stoma creation. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017;30(3):162-71.

- WOCN Society, AUA, and ASCRS Position Statement on Preoperative Stoma Site Marking for Patients Undergoing Ostomy Surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2021;48(6):533-6.

- Bass EM, Del Pino A, Tan A, Pearl RK, Orsay CP, Abcarian H. Does preoperative stoma marking and education by the enterostomal therapist affect outcome? Dis Colon Rectum 1997;40:440–2.

- Park JJ, Del Pino A, Orsay CP, et al. Stoma complications: the Cook County Hospital experience. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42(12):1575-80.

- Shellito PC. Complications of abdominal stoma surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41(12):1562-72.

- Kwiatt M, Kawata M. Avoidance and management of stomal complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2013;26(2):112-21.

- LeBlanc K, Whiteley I, McNichol L, Salvadalena G, Gray M. Peristomal medical adhesive-related skin injury: results of an international consensus meeting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(2):125-136.

- Cwaliński J, Paszkowski J, Banasiewicz T. New perspectives in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds. NPWTJ 2018;5(4):10-2.

- Banasiewicz T, Borejsza-Wysocki M, Meissner W, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy in patients with large postoperative wounds complicated by multiple fistulas. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2011;6(3):155–63.

- Hasan MY, Teo R, Nather A. Negative-pressure wound therapy for management of diabetic foot wounds: a review of the mechanism of action, clinical applications, and recent developments. Diabet Foot Ankle 2015;1,6:27618.

- Li T, Zhang L, Han LI, et al. Early application of negative pressure wound therapy to acute wounds contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus: an effective approach to preventing biofilm formation. Exp Ther Med 2016;11(3):769–76.

- Omar A, Wright JB, Schultz G, at al. Microbial biofilms and chronic wounds. Microorganisms 2017;5(1):9.

- Herrero Valiente L, García-Alcalá DG, Serrano Paz P, Rowan S. The challenges of managing a complex stoma with NPWT. J Wound Care 2012;21(3):120-3.

- Wright H, Kearney S, Zhou K, Woo K. Topical management of enterocutaneous and enteroatmospheric fistulas: a systematic review. Wound Manag Prev 2020;66(4):26-37.

- Herrero Valiente L, García-Alcalá DG, Serrano Paz P, Rowan S. The challenges of managing a complex stoma with NPWT. J Wound Care. 2012 Mar;21(3):120-3.

- Sun X, Wu S, Xie T, Zhang J. Combing a novel device and negative pressure wound therapy for managing the wound around a colostomy in the open abdomen: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(52):e9370.

- Mohamed E, Elmoniem AE, Elmowafi HM, Shebl AM. Effect of training program on performance of nurses caring for patient with negative pressure wound therapy. IOSR-JNHS 2019;8(1):31-5.

- Malmsjö M, Huddleston E, Martin R. Biological effects of a disposable, canisterless negative pressure wound therapy system. Eplasty 2014;2,14:e15.

- Ozkan B, Markal Ertas N, Bali U, Uysal CA. Clinical Experiences with Closed Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Treatment on Various Anatomic Locations. Cureus. 2020, 26;12(6):e8849.