Volume 44 Number 1

Wound bed preparation 2024: Delphi consensus on foot ulcer management in resource-limited settings

Hiske Smart, R Gary Sibbald, Laurie Goodman, Elizabeth A Ayello, Reneeka Jaimangal, John H Gregory, Sadanori Akita, Afsaneh Alavi, David G Armstrong, Helen Arputhanathan, Febe Bruwer, Jeremy Caul, Beverley Chan, Frans Cronje, Belen Dofitas, Jassin Hamed, Catherine Harley, Jolene Heil, Mary Hill, Devon Jahnke, Dale Kalina, Chaitanya Kodange, Bharat Kotru, Laura Lee Kozody, Stephan Landis, Kimberly LeBlanc, Mary MacDonald, Tobi Mark, Carlos Martin, Dieter Mayer, Christine Murphy, Harikrishna Nair, Cesar Orellana, Brian Ostrow, Douglas Queen, Patrick Rainville, Erin Rajhathy, Gregory Schultz, Ranjani Somayaji, Michael C Stacey, Gulnaz Tariq, Gregory Weir, Catharine Whiteside, Helen Yifter, Ramesh Zacharias

Keywords Diabetes, wound bed preparation, low-resource settings, foot ulcer, rural, delphi consensus, low- and middle-income countries, innovation

For referencing Smart H et al. Wound bed preparation 2024: Delphi consensus on foot ulcer management in resource-limited settings. WCET® Journal 2024;44(1):13-35.

DOI 10.33235/wcet.44.1.13-35

Abstract

Background Chronic wound management in low-resource settings deserves special attention. Rural or underresourced settings (ie, those with limited basic needs/healthcare supplies and inconsistent availability of interprofessional team members) may not be able to apply or duplicate best practices from urban or abundantly resourced settings.

Objective The authors linked world expertise to develop a practical and scientifically sound application of the wound bed preparation model for communities without ideal resources.

Methods A group of 41 wound experts from 15 countries reached a consensus on wound bed preparation in resource-limited settings.

Results Each statement of 10 key concepts (32 substatements) reached more than 88% consensus.

Conclusions The consensus statements and rationales can guide clinical practice and research for practitioners in low-resource settings. These concepts should prompt ongoing innovation to improve patient outcomes and healthcare system efficiency for all persons with foot ulcers, especially persons with diabetes.

General purpose

To review a practical and scientifically sound application of the wound bed preparation model for communities without ideal resources.

Target audience

This continuing education activity is intended for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses with an interest in skin and wound care.

Learning objectives/putcomes

After participating in this educational activity, the participant will:

- Summarise issues related to wound assessment.

- Identify a class of drugs for the treatment of type II diabetes mellitus that has been shown to improve glycemia, nephroprotection, and cardiovascular outcomes.

- Synthesise strategies for wound management, including treatment in resource-limited settings.

- Specify the target time for edge advancement in chronic, healable wounds.

Introduction

A framework for wound bed preparation (WBP) was introduced in 2000 to emphasise treating the whole person as a foundation of optimal local wound care.1 As this has evolved into an international framework, it became clear that not all wounds are healable. These concepts of maintenance and nonhealable wounds led to revisions of local wound care principles and WBP expansion. The importance of integrated coordinated care with nurses, doctors, and allied healthcare professionals working together to optimise patient care outcomes and healthcare system utilisation was paramount in further WBP developments.

This article focuses on applying the WBP framework to manage foot-related wounds, particularly in persons with diabetes (PWDs), leprosy-related neuropathic foot ulcers, and other complications that include neuropathy and vascular disease. Several parameters are critical to PWDs, including poor glycemic control, BP changes, high cholesterol, inadequate plantar pressure redistribution, infections, and lack of exercise. The effects of smoking are also particularly detrimental to saving limbs and lives of PWDs.

Critical for this article is a set definition for resource-restricted settings, including low resource availability; lacking or restricted funding; remote, isolated, or rural settings; and Indigenous populations. These terms all relate to healthcare settings that may have challenges accessing supplies, equipment, specialists, and advanced wound care competencies and skills. Low-resource settings can be present anywhere in the world and are not limited to lower-income or developing countries.

The Delphi process underpinning this work expanded and developed the WBP framework in its current format. Forty-one authors drawn from 15 countries took part in the Delphi process, which occurred over two rounds using a four-part Likert-type scale (1, strongly agree; 2, agree; 3, disagree; 4, strongly disagree). The first round consisted of 29 statements. Although all statements exceeded the desired 80% consensus level, there were 299 comments considered by the lead group of authors. A professional editor was employed to improve the comprehension and grammatical accuracy of the statements before a Delphi round 2 was deployed with 32 constructed statements. All statements exceeded 88% consensus level.

In round 2, 14 statements achieved 100% consensus. One statement stood out and was rated as “strongly agree” by all Delphi panel members: 10C. Establish timely and effective communication that includes the patient and all interprofessional wound care team members for improved healthcare system wound outcomes. In parallel, each of the international wound experts worked in groups to develop the manuscript content. Refer to Supplemental Table 1 (http://links.lww.com/NSW/A176) for the consensus statements.

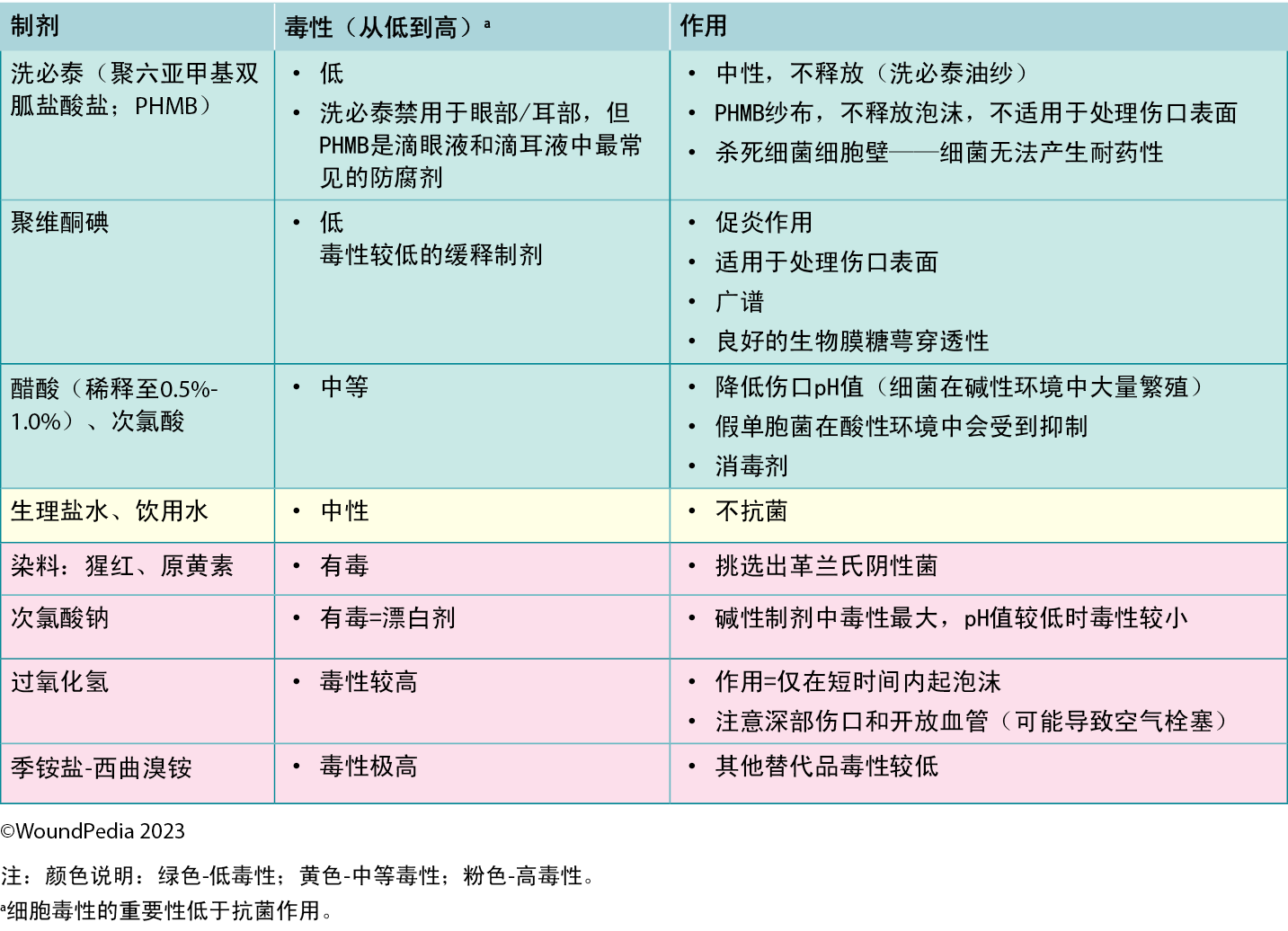

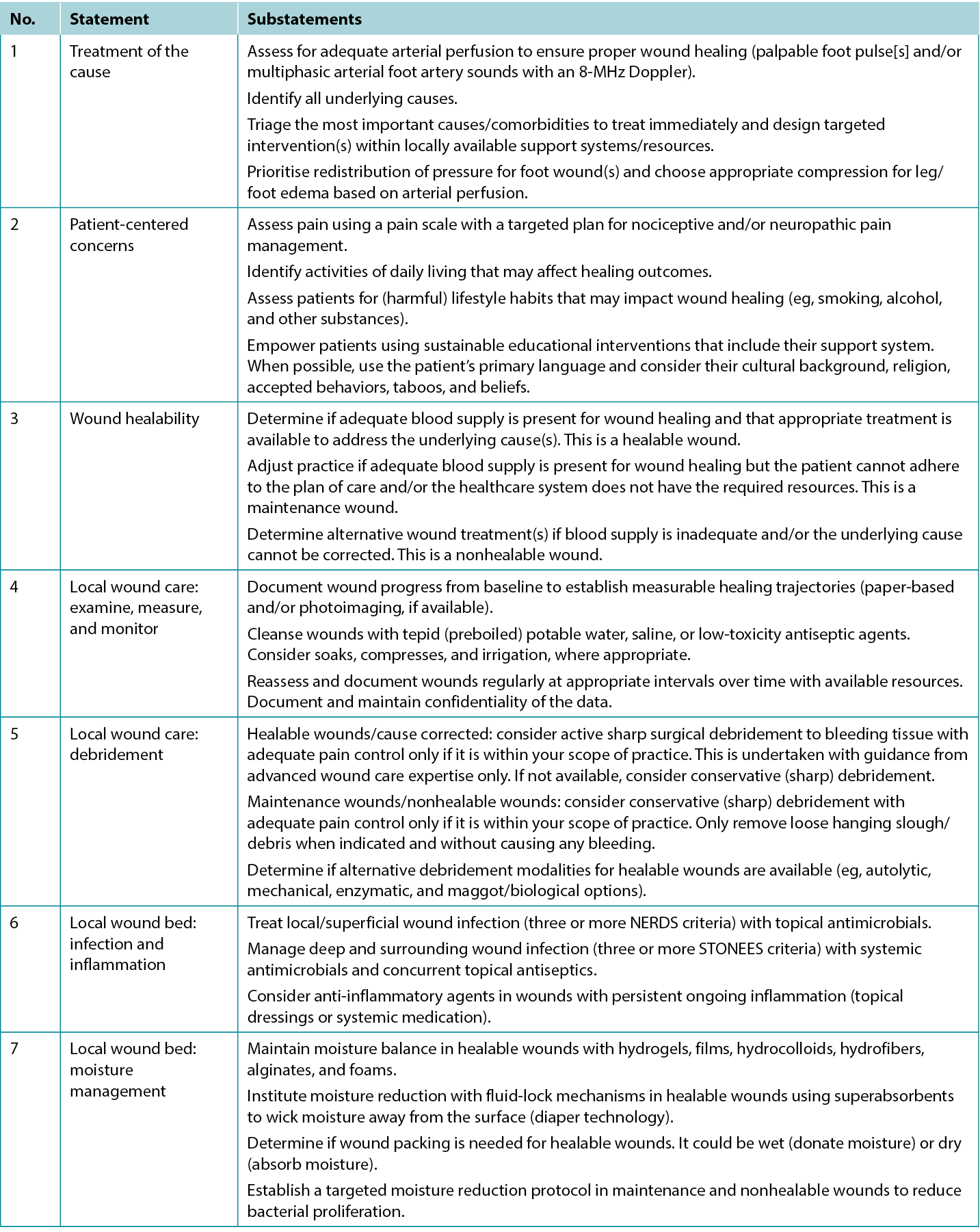

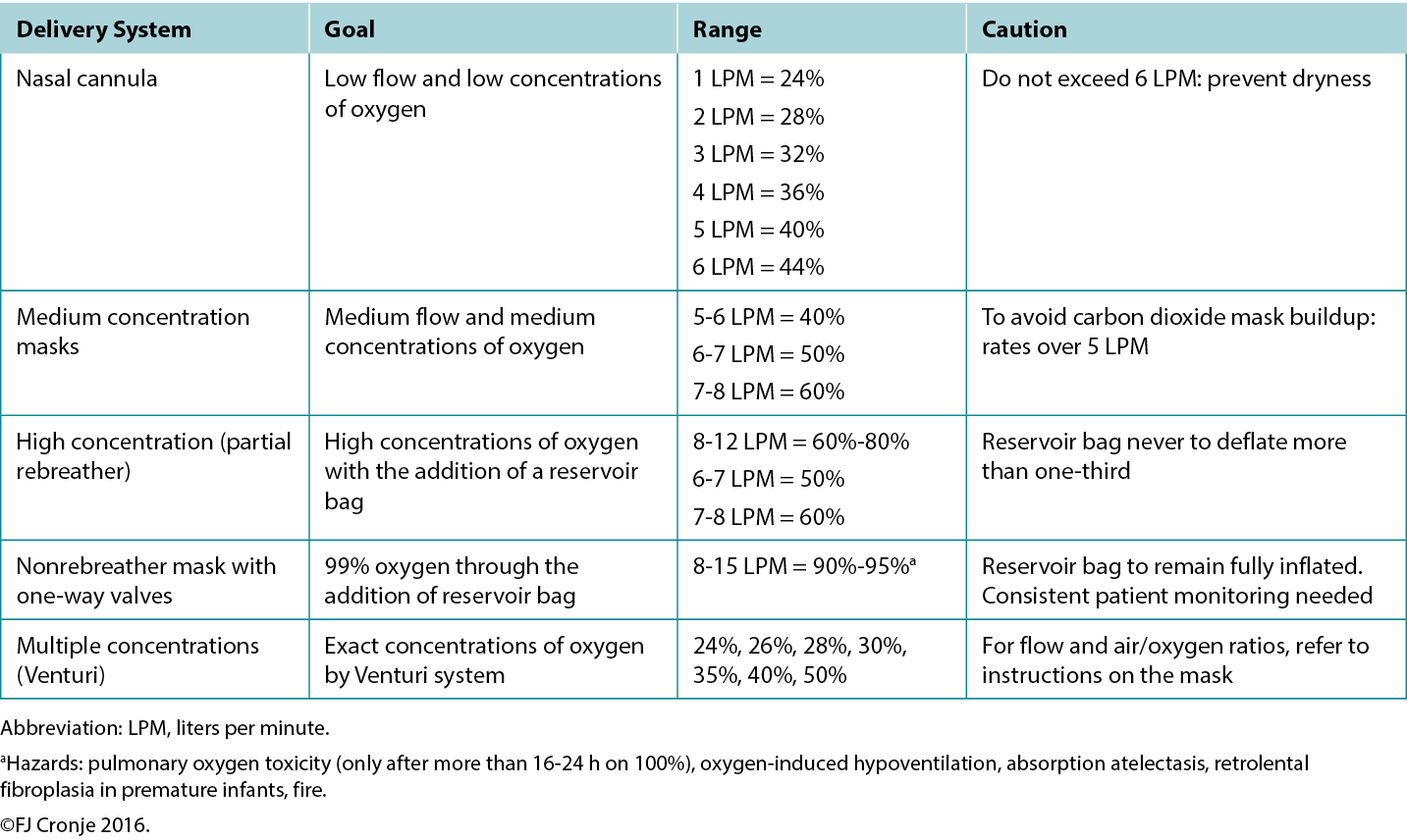

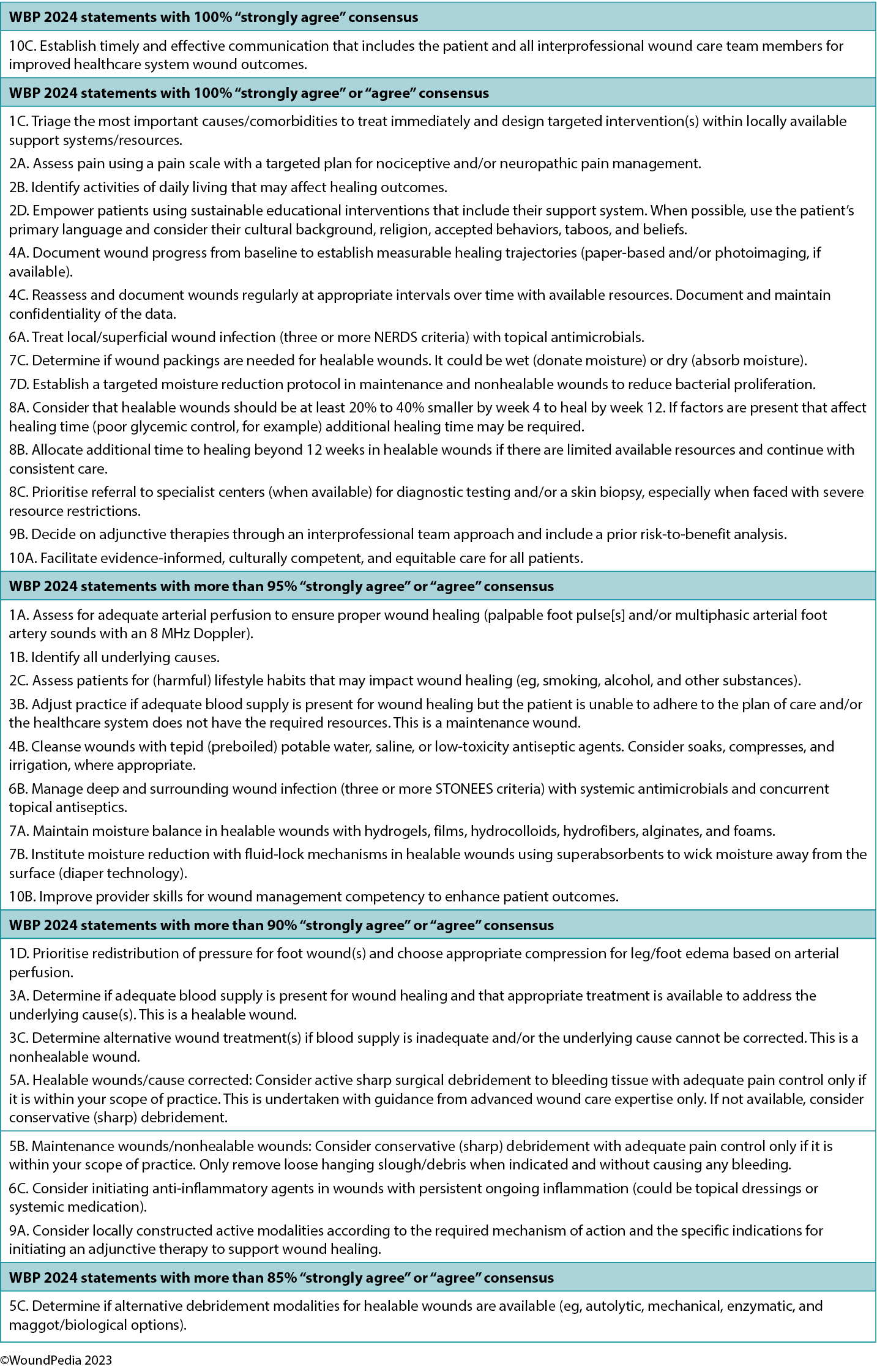

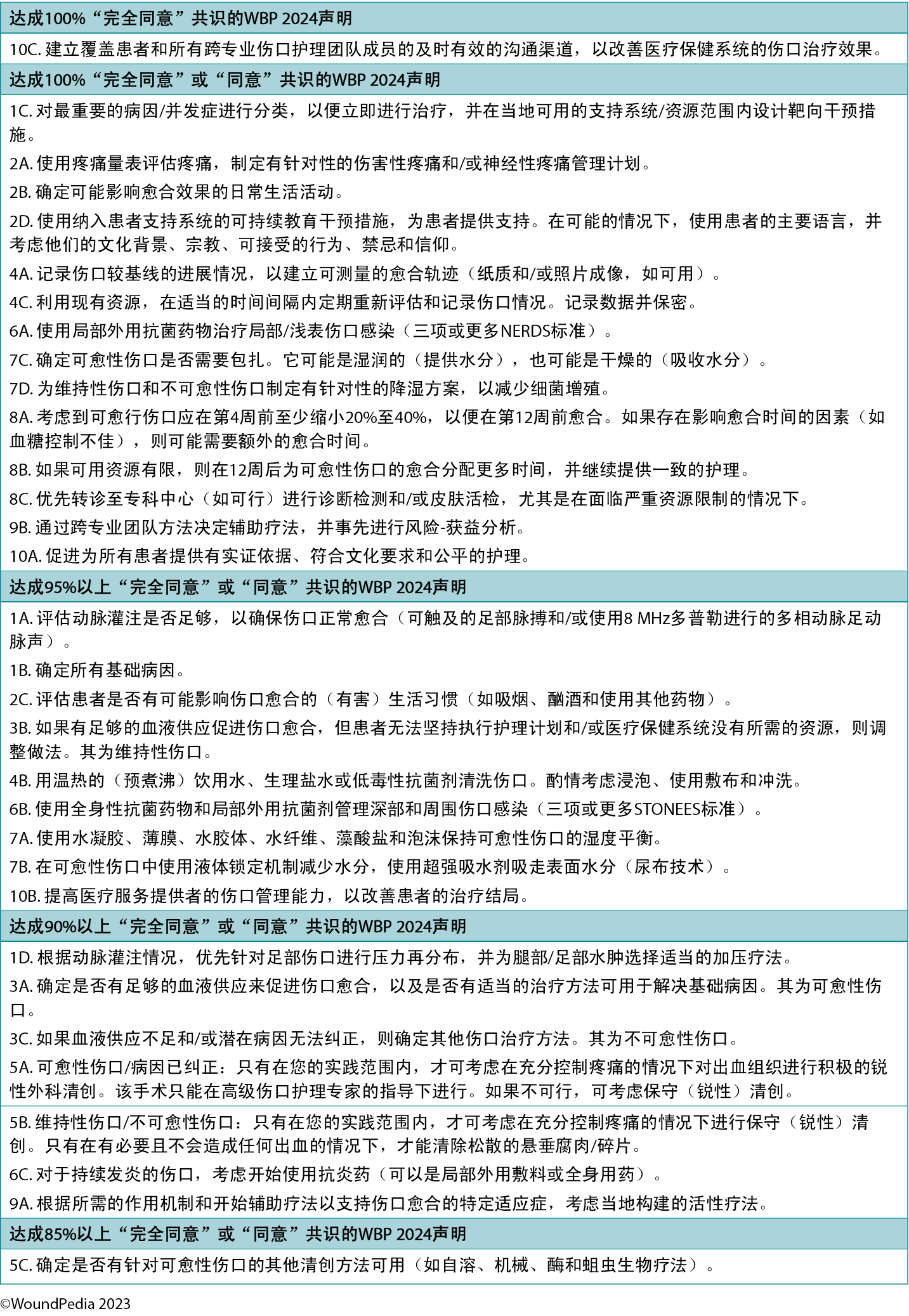

The consensus aimed to set a scientifically based minimal standard of care that could be optimised for available resources. Refer to Table 1 for the 10 key steps and 32 substatements for wounds in limited-resource environments. This consensus process updated the framework for WBP to be applicable regardless of resource availability. In addition, it also includes the concepts of healing trajectories and healthcare system change for the first time (Figure 1).

The remainder of this report will highlight the 10 consensus statements and discuss the rationale for each statement.

Figure 1. Wound bed preparation 2024. ©WoundPedia 2023

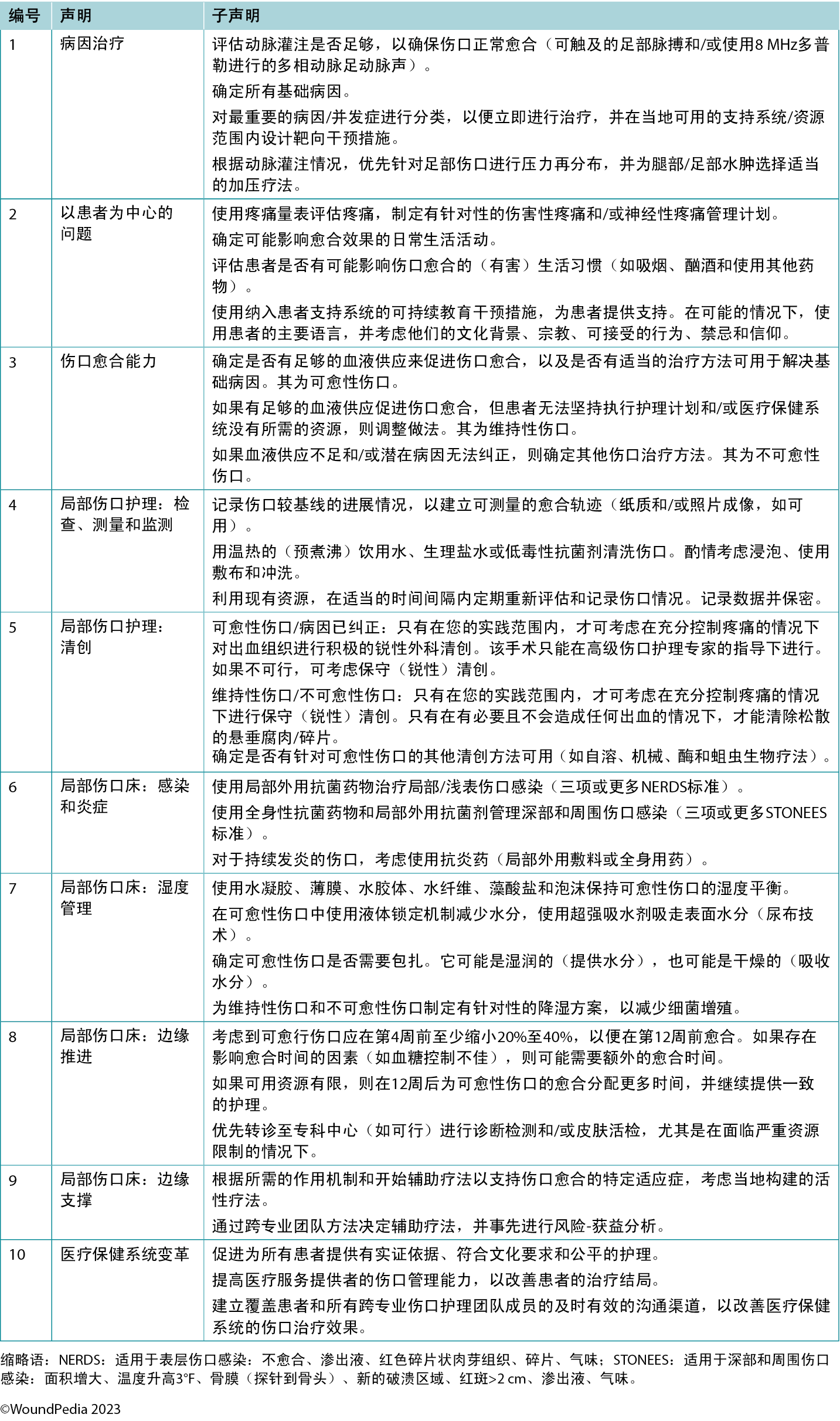

Table 1. Wound bed preparation for wounds below the knee in environments with limited resource availability

Statement 1: treatment of the cause

1A. Assess for adequate arterial perfusion to ensure proper wound healing (palpable foot pulse[s] and/or multiphasic arterial foot artery sounds with an 8-MHz Doppler)

To determine lower-limb blood flow, find a palpable foot pulse(s) as a vital first action. Start with the dorsalis pedis and/or the posterior tibial pulses. If an 8-MHz handheld Doppler is available, confirm multiphasic flow patterns (biphasic/triphasic). Refer to vascular specialists when a monophasic or absent Doppler sound is observed or foot pulses are not palpable. Other signs of inadequate arterial perfusion are lower limb pain at rest and ischemic limb changes (cold extremity with dependent rubor that blanches on elevation).

Persons with diabetes are susceptible to microvascular issues (peripheral neuropathy, Charcot foot changes) and macrovascular complications including peripheral arterial disease (PAD). These conditions contribute to calluses, foot ulcers, and mixed tissue loss. Because up to 50% of susceptible populations experience both diabetes and PAD,2 timely identification of PAD is critical (using physical examination and vascular tests) because it is a major risk factor for poor ulcer healing and amputation. If detected, immediate revascularisation (angioplasty or vascular bypass) is vital to restore proper arterial flow to the foot. Additional assessment may include capillary refill time, a Buerger blanching test (pale on elevation, bright red rubor on dependency), and claudication with walking.

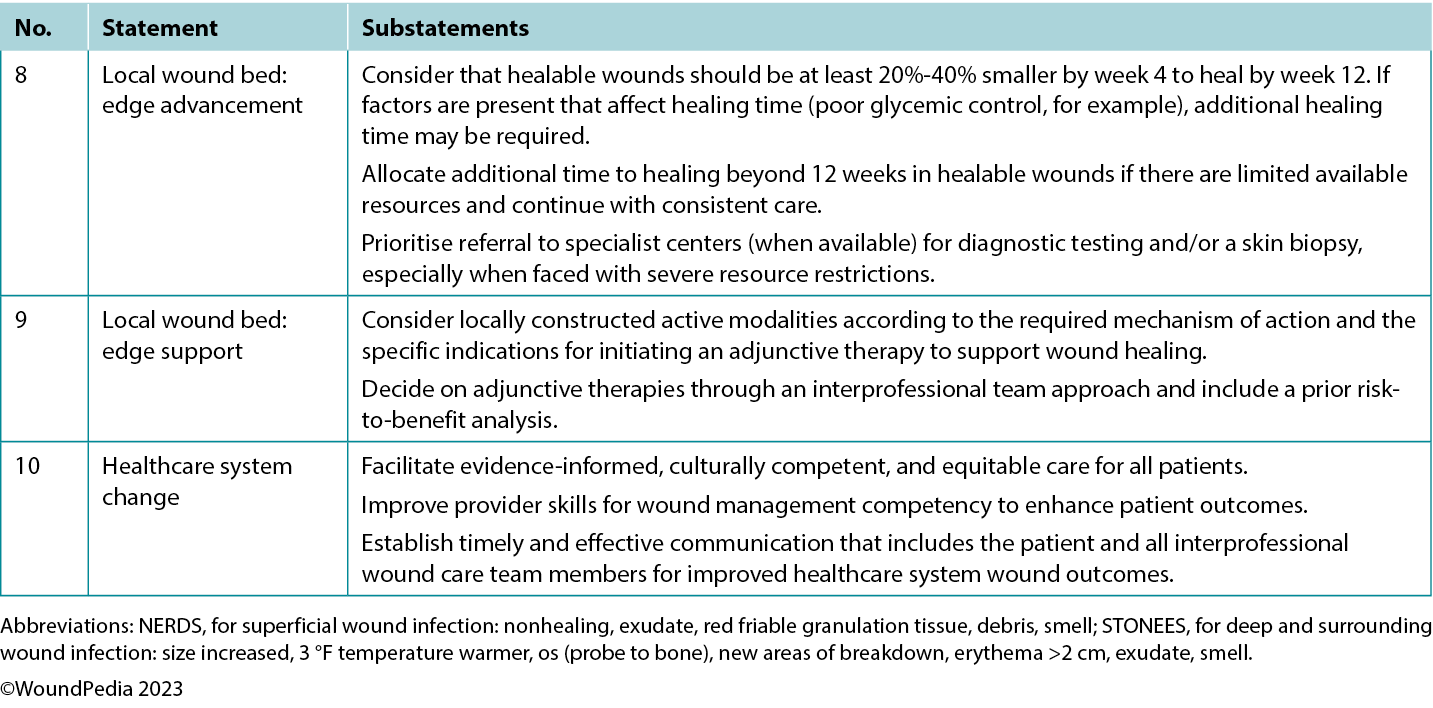

Vascular examination. In cases of arterial insufficiency, the extremity is often cool to the touch because of insufficient nutrient and oxygen supply (Table 2). Severe cases may manifest tissue necrosis presenting as ulcers, macerated toe webs (often with secondary infection), fissures, or gangrene. Other severe case indicators include pallor upon leg elevation, exercise-induced claudication that resolves with rest, dependent cyanosis or rubor, and muscle atrophy. Notably, lower extremity edema is more indicative of venous rather than arterial issues. Arterial lesions are generally punched out, with a deep base that often contains tendons, whereas venous ulcers show irregular border morphology with a shallow granulation tissue base.3

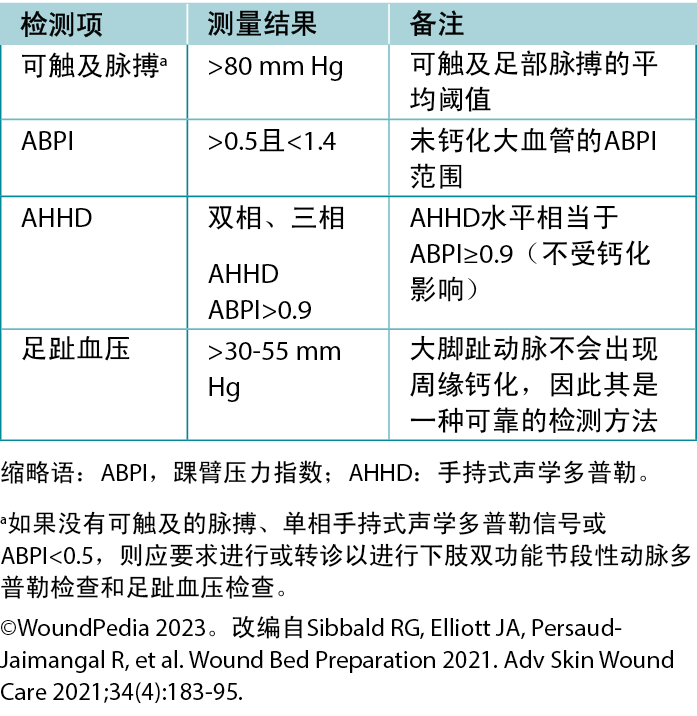

Table 2. Vascular supply needed for tissue healing

Ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI) examination. The ABPI measures the ratio of ankle systolic BP divided by the brachial systolic BP using an 8-MHz Doppler. The procedure involves using a BP cuff and recording systolic BP when arterial sounds reappear after cuff inflation. However, factors such as edema, inflammation, and arterial calcification can affect its accuracy. If an 8-MHz Doppler cannot be afforded/obtained, early referral to a tertiary assessment center becomes the priority in cases where the absent foot pulses are present. In certain healthcare settings, an ABPI is still required as vital quantification assessment before beginning any lower limb intervention.

Audible handheld Doppler (AHHD) examination. An AHHD can easily be added as an additional parameter in certain settings, should providers choose a simpler and faster test (not influenced by calcification, no need to squeeze a painful calf, and no need to be recumbent for 20 minutes). The AHHD assessment also can provide accurate results in case of large toe amputation and be recorded as an MP3 or MP4 file and transferred for remote verification of the signal interpretation.

Healthcare professionals should apply gel on the appropriate foot pulse sites with an 8-MHz Doppler probe positioned at a 45° angle to the skin on the dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries. The acquired Doppler signals/waveforms can then be analysed (either by audible sound or visual tracings): A comprehensive tutorial on the AHHD procedure is available online at https://journals.lww.com/aswcjournal/Pages/videogallery.aspx?videoId=20. Optimise signal quality with careful repositioning of the probe to obtain the loudest or most multiphasic signal.

A monophasic or absent waveform warrants a comprehensive vascular assessment, including a Duplex segmental lower leg arterial Doppler in the vascular laboratory. A multiphasic waveform typically indicates the absence of peripheral vascular disease.4 In PWDs, interpret the ABPI ratio with caution (due to arteriosclerosis or arterial calcification); AHHD multiphasic findings are a preferable choice to confirm adequate blood supply for wound healing. A multiphasic waveform (biphasic, triphasic) suggests an AHHD value equivalent to a normal ABPI ≥0.9.

Although AHHD is effective in excluding arterial disease, it may not identify existing segmental perfusion deficits—islands of ischemia or angiosome defects.5 Therefore, physical examination of the foot and lower limb is vital for a conclusive diagnosis. Healthcare professionals can record AHHD signals and transmit them to specialists, facilitating either synchronous or asynchronous assessments remotely. Synchronous assessments enable real-time patient involvement and prompt decision-making.

Chronic venous insufficiency. Chronic venous insufficiency may coexist in PWDs and those with foot ulcers. It mainly affects the lower limbs and impairs the return of deoxygenated blood to the heart and lungs. This condition often arises from venous valve dysfunction that can be triggered by factors including pregnancy or weight gain. Symptoms commonly include varicose veins, edema, skin discoloration from hemosiderin, lipodermatosclerosis, and venous ulcers.6 These ulcers can be any size (from small to circumferential) and form quickly over areas of venous pooling, usually on the medial aspects of the lower limbs.

The cornerstone of treatment for venous ulcers is compression therapy. This compensates for valve dysfunction by enhancing the peristaltic action of the calf muscle pump. Additional measures include leg elevation and walking. Venous ablative procedures may be considered when ulcers are attributed to superficial veins. Untreated venous edema can delay foot ulcer healing.7

For the medical optimisation of PAD, key strategies include optimal BP control, initiating cholesterol medication, and, often, starting statin therapy. Recent studies also recommend treating patients with PAD and concurrent coronary artery disease or carotid disease using a combination of low-dose aspirin (91-100 mg PO daily) and low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg PO BID).8 Additional modifiable factors are smoking cessation and walking or exercise programs. For patients with a foot ulcer (especially in PWDs), appropriate plantar pressure redistribution or offloading is essential.

1B. Identify all underlying causes

Foot complications are of great concern to PWDs and represent a significant burden of disease to healthcare systems. A holistic approach is represented by the mnemonic AIM (assessment, identification, management) and focuses on treating or mitigating the underlying cause of diabetic foot issues, especially neuropathy. The application of a focused assessment approach as a baseline standard of care (VIPS: vascular, infection, pressure, surgical debridement) is crucial in preventing severe complications, including foot ulcerations, lower limb amputations, and an increased incidence of early/preventable death. Some critical foot-related elements in resource-challenged settings include late presentations to formal care, delayed diagnosis,9 barefoot walking, neglected wounds, and the absence of preventive foot care. A hospital-based observational analysis conducted in Ethiopia identified several factors contributing to diabetic foot complications;10 these included high humidity, foot deformity, neuropathy, unidentified active ulcers, inadequate or ill-fitting footwear, poor foot hygiene (eg, foot and toenail fungus), and lack of foot care awareness. A systematic review on plantar ulcers among patients with leprosy (n = 7 studies) identified the following risk factors for developing ulcers: inability to feel a 10 g monofilament on sensory testing, severe foot deformities or hyperpronation, lower education, and unemployment.11 Addressing these challenges in any resource-challenged environment requires a multipronged approach that may include patient and healthcare professional education, early detection, access to care, footwear programs, and community engagement.

Regular and thorough foot assessments include detecting neuropathy (loss of protective sensation), vascular issues (poor or absent lower limb blood circulation), signs of infection, areas of high pressure (callus formation), and friction (blisters, often with hemorrhagic components) to facilitate timely interventions. The simplified 60-second screening tool may be a valuable means to quickly assess, stratify, and follow up patients based on their risk levels without significant cost.12 Patients with a history of ulceration, amputation, peripheral vascular surgery, or Charcot neuroarthropathy are at the highest risk for skin breakdown and should receive additional attention to prevent ulceration and further complications.

To detect infection, the NERDS (superficial wound infection: nonhealing, exudate, red friable granulation tissue, debris, smell) or STONEES (deep and surrounding wound infection: size increased, 3 °F temperature warmer, os [probe to bone], new areas of breakdown, erythema >2, exudate, smell) criteria along with using noncontact infrared thermometry can be helpful.13 Elevated temperatures of 3 °F compared with the opposite limb may signal inflammation and a foot at a higher risk of ulceration.13 A comparative change of 1.67 °C is difficult to measure clinically. This same finding in a person with a lower leg or foot ulcer is eight times more likely to signify deep and surrounding infection when accompanied by two or more additional STONEES criteria.13

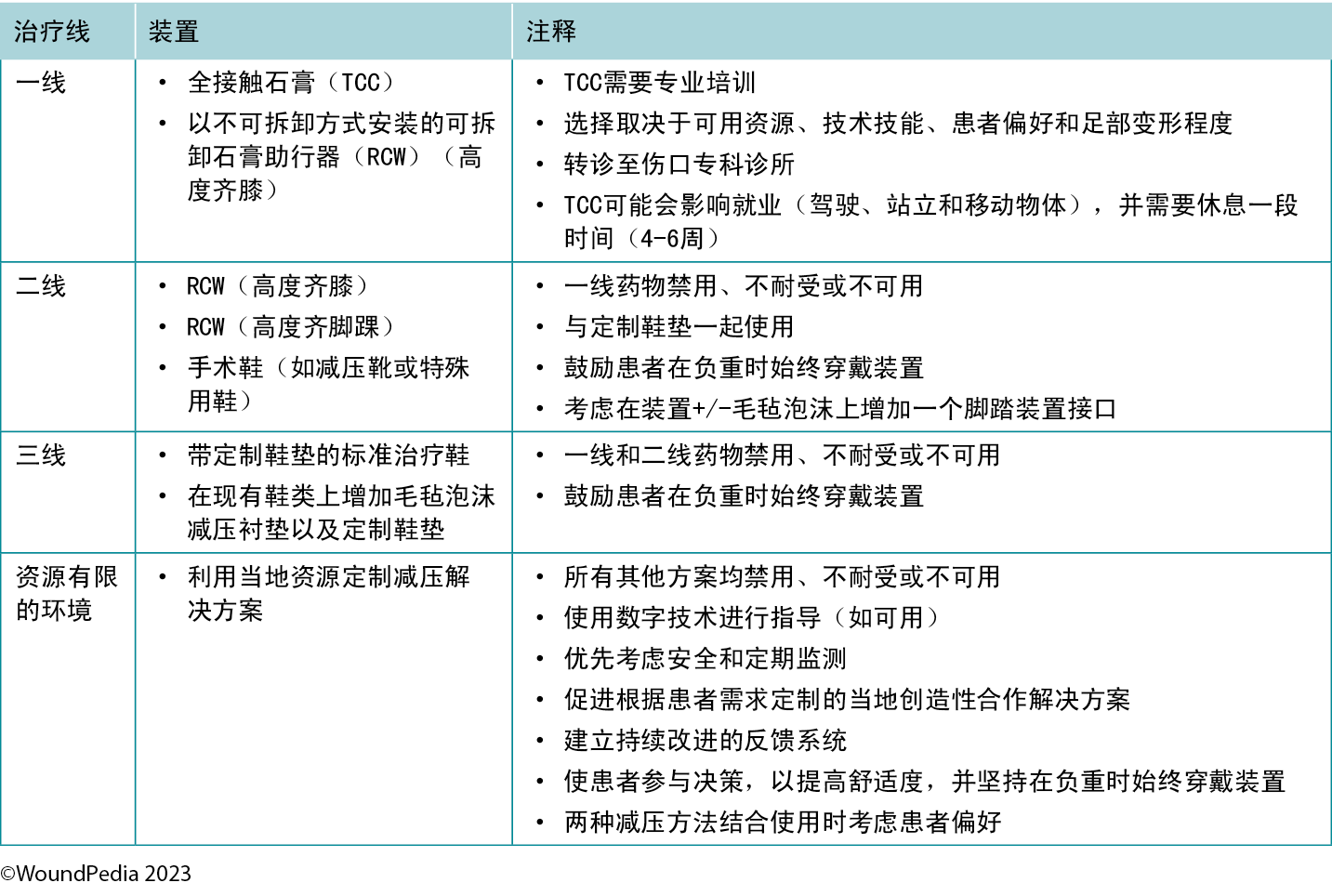

Patients with neuropathy without an ulcer and presenting with a hot swollen foot could have acute Charcot neuroarthropathy. Infrared thermometry is a valuable assessment tool in these cases: acute Charcot feet may be 8 to 15 °F warmer than the mirror image on the opposite foot. These patients require a comprehensive medical history, physical examination, and radiographic images to facilitate early detection. Further actions include the application of a total contact cast for stabilisation and complete plantar pressure offloading with a wheelchair to prevent further bone deterioration and prevent lower limb amputation (Table 3).

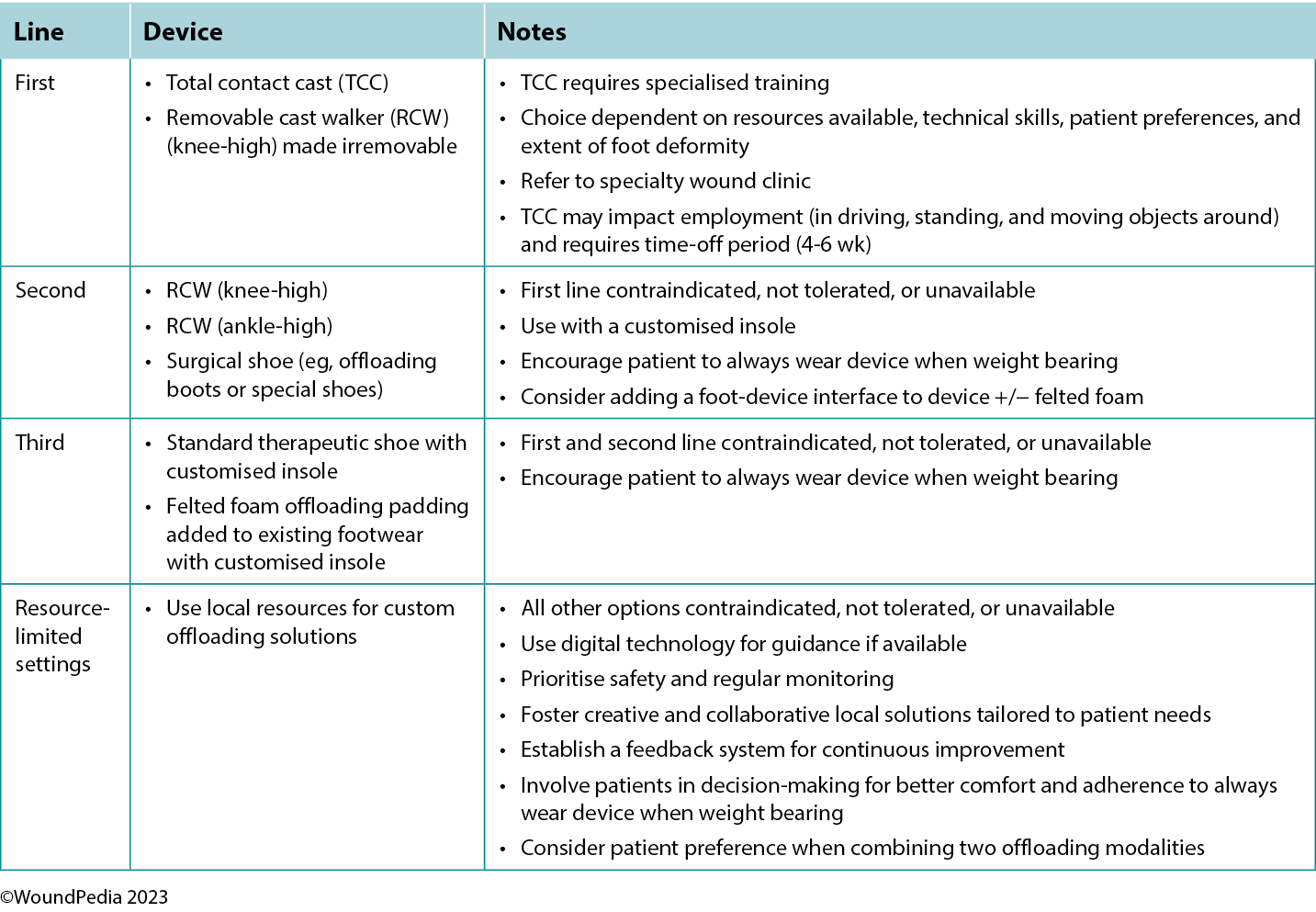

Table 3. Offloading interventions for a plantar diabetic/neuropathic foot wound28

Callus formation in PWDs is positively correlated with pressure and shear stress. In individuals with diabetic neuropathy, various factors including foot deformities, limited joint mobility, repetitive stress during walking, and poorly fitting shoes can increase the risk of callus formation.14 Moreover, the presence of calluses can pose a significant risk because repetitive trauma may lead to subcutaneous hemorrhage and eventually progress to ulceration. Provide tailor-made pressure redistribution devices (soft insoles, cobbler interventions to adapt shoes, and reduced barefoot walking) to prevent subsequent callous-to-ulcer progression.

Different etiologic causes may lead to foot ulcers in PWDs: neuropathic because of peripheral neuropathy, ischemic associated with PAD, or a combination of both—neuroischemic foot complications. The presence of diabetic neuropathy is established from medical history; physical examination (5.07/10 g monofilament test); altered sensation distributed symmetrically in both limbs (stocking and glove distribution); and burning, stinging, shooting, or stabbing pain.

1C. Triage the most important causes/comorbidities to treat immediately and design targeted intervention(s) within locally available support systems/resources

A diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) occurs in 25% to 34% of PWDs and is one of the most feared complications, potentially leading to lower limb amputation, severe disability, and reduced life expectancy.15 Multifactorial in origin, diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy and PAD leave feet highly vulnerable to traumatic injury. Access to timely diagnosis and intervention are determinant factors in effective management and limb preservation.

Chronic hyperglycemia measured by elevated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is a major risk factor for sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy. Both PAD and dry skin increase foot vulnerability to infection and delayed healing, all contributing to poor outcomes. Chronic kidney disease adds to the risk.16 Recent studies of continuous glucose monitoring report that high glucose variability (reduced time to target range levels) may additionally contribute to long-term complications.17

Up to 50% of PWDs will develop neuropathy with no known cure. Management includes proper daily foot inspections for evidence of trauma or infection, foot care, and effective glucose control.18 In addition to neuropathy, PAD contributes equally to DFUs; PAD is largely asymptomatic and may remain underdiagnosed and untreated for a prolonged period. Individuals with diabetes have more than a twofold increased prevalence of PAD compared with those without.19 A systematic review of community-based studies for global prevalence and risk factors for PAD ranked diabetes highest next to smoking.20

The European Society of Hypertension recommends providers and patients target a systolic BP less than 130 mm Hg and diastolic BP less than 80 mm Hg. In PWDs, systolic BP should not fall less than 120 mm Hg to prevent reduced blood flow to vital organs and lower limbs.21 Although diuretics, calcium-channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and β-blockers can all be used, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers reduce cardiovascular events.22,23 Recently, SGLT2 inhibitors have shown excellent results in improving glycemia, nephroprotection, and cardiovascular outcomes.24 In addition, DFU incidence is reduced by early detection of PAD with lifestyle modifications.17

The complexity of managing a DFU requires an interprofessional team approach to identify biological, social, geographic, and cultural determinants of health. In Denmark, PWDs are registered by region with access to specialised clinics with interprofessional wound care teams. Lower limb amputation rates have declined significantly due to improved diabetes care, regular foot inspection, better self-care, and timely treatment.25 In more geographically dispersed diverse populations (eg, Ontario, Canada), significant disparities in amputation rates exist, highest in rural regions where timely prevention such as revascularisation surgery and foot care specialists are underserviced or absent.

The most vulnerable persons for diabetic foot-related amputations in Canada are Indigenous people, immigrants, and persons living in rural and northern regions.26 The Indigenous Diabetes Health Circle provides a culturally sensitive approach to local Ontario First Nations communities with education and knowledge about diabetes, wellness, and self-management. Its holistic foot care program supports a continuum of services that connects community members to Indigenous agency partners and local healthcare professionals and is proven to reduce DFU incidence and prevent amputations.27

1D. Prioritise redistribution of pressure for foot wound(s) and choose appropriate compression for leg/foot edema based on arterial perfusion

The criterion standard for plantar pressure redistribution devices is the total contact cast or the removable cast walker made irremovable.28 Even in healthcare systems in which these offloading modalities are readily available, less than 10% of eligible patients are fitted for and adherent to the use of these devices.29

Offloading is paramount to healing foot ulcers (Table 3). The aim is to select the best device for the patient incorporating patient-centered concerns, the goals of care, and best practice evidence. Consider creative solutions to repurpose local materials such as soft felted inserts for offloading in resource-limited settings. It is important to establish an early surveillance program between the patient and healthcare professional to monitor and ensure the desired offloading outcomes. Healthcare professionals need to evaluate the effectiveness of the devices and continually make modifications as needed through established follow-up. In regions lacking specialised practitioners, empowering healthcare workers with competencies in basic offloading can bridge this gap.

Statement 2: patient-centred concerns

2A. Assess pain using a pain scale with a targeted plan for nociceptive and/or neuropathic pain management

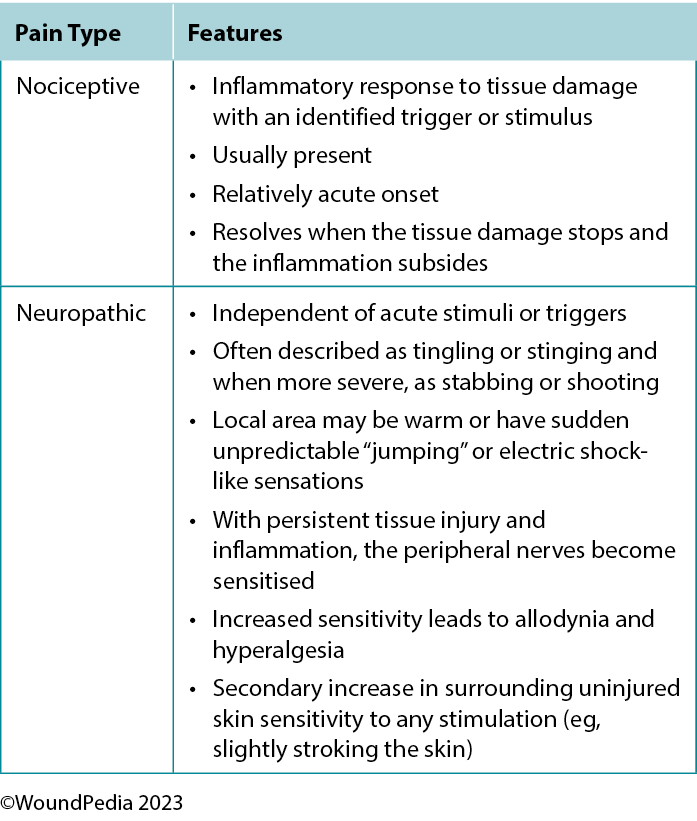

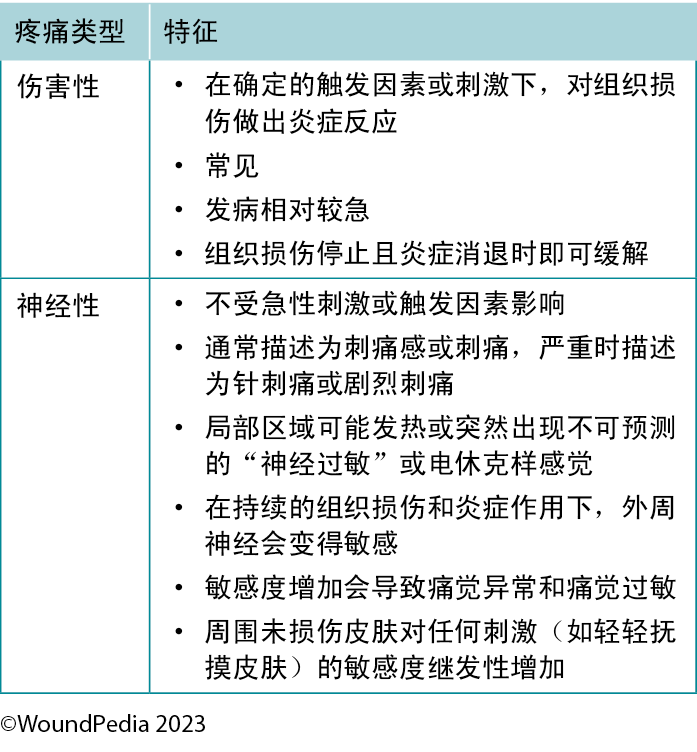

The perception of pain involves a stimulus that may be physical or chemical. There are two main types of pain: nociceptive and neuropathic (Table 4). Wound-related pain is an important component of patient-centered concerns that is often undervalued by healthcare professionals. By the late 1990s, wound pain was a focus for healthcare professionals with the launch of a pivotal position document focused on wound pain.30 The document recognised and focused on the distress of chronic wound pain and its influence on patients’ health-related quality of life. The management of wound pain was then integrated into the WBP framework.1,31

Table 4. Pain types and responses30

Pain can play a significant role in the total management of persons with wounds and their ultimate healing success.32 Pain signals associated with injury play an important function in patient wellness and as such must be acknowledged through adequate assessment and management. For example, pain or any change in pain is a key predictor of wound infection and one of the four cardinal signs of inflammation.1 Unresolved pain is often associated with delayed wound closure.

Assessment. A pain history is essential to wound pain management.32 Assessment must include the nature, onset, duration, and exacerbating and relieving factors. This will help determine the cause of the pain and direct its management. Pain intensity can be reliably measured using validated pain scales. A verbally administered 0- to 10-point numerical rating scale is a good first choice for measuring pain numerical intensity. Most patients can function with a pain level of 3 to 4 out of 10.33

Patients with persistent pain should be reassessed regularly for improvement, deterioration, and adherence to medication regimens. The use of a pain diary with entries regarding pain intensity, medications used, mood, and response to treatment may be a good management strategy. For individuals with communication limitations, the pain scale should incorporate pictures for easy recognition.

Management. The management of wound pain can be integrated into the WBP framework: treat the cause and address local wound factors and patient-centered concerns.3 Treating the cause should determine the correct diagnosis and initiate treatment of the wound pain. Patient-centered concerns must focus on what the patient sees as the primary reasons and resolutions for the pain. Patient anticipatory pain and suffering can be just as disruptive to quality of life as the actual experience of pain.

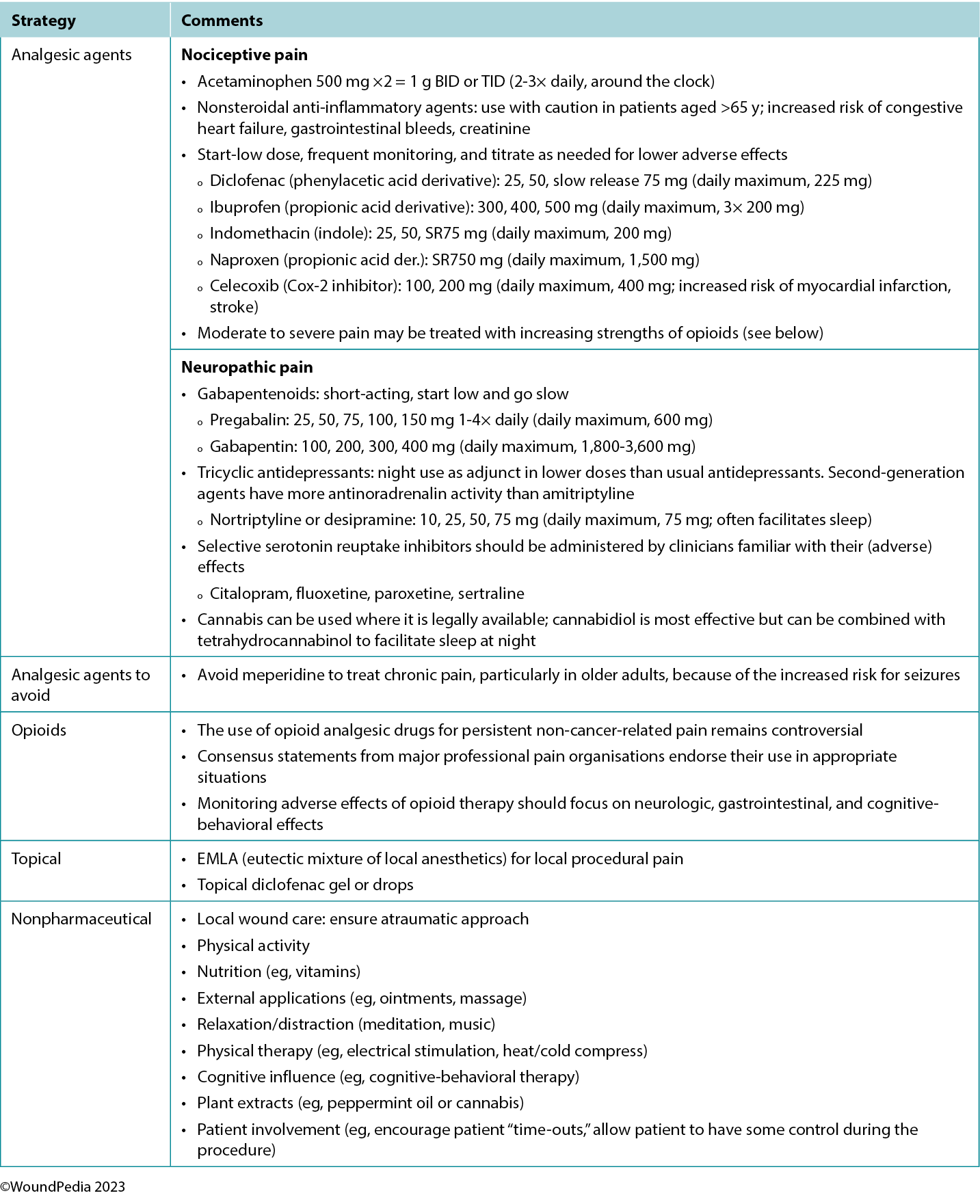

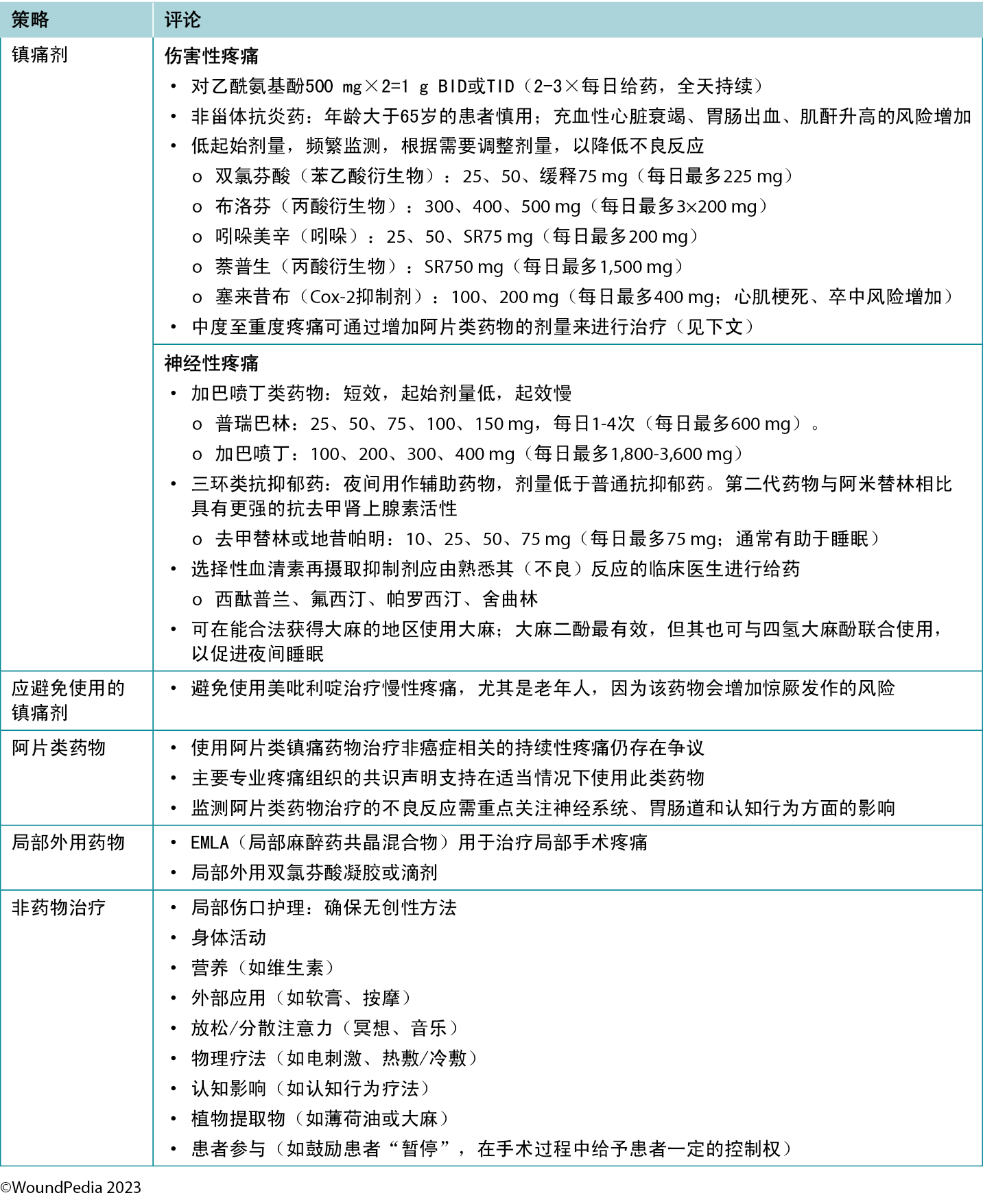

Multiple pain management strategies exist and are not always pharmaceutical (Table 5). Consider total patient management, including all aspects of WBP, in choosing a management strategy. Remember: pain is what the patient says it is.34

Table 5. Pain management strategies

Assessment and management given limited resources. In regions with limited resources, assessment remains possible because it requires no costly tools. Most pain scales are freely available despite some initial cost relative to education and training of practitioners.31 Treatment options for pain in resource-restricted environments may be more practical if driven with nonpharmacologic methods (Table 5). Some of these options may also be more socially acceptable or already practiced culturally (eg, meditation, plant-based treatments) and particularly applicable in nociceptive pain management. Implementing such strategies can then preserve pharmaceutical management for those with pain that cannot be managed by nonpharmacologic means (eg, neuropathic pain).35

2B. Identify activities of daily living that may affect healing outcomes

2C. Assess patients for (harmful) lifestyle habits that may impact wound healing (eg, smoking, alcohol, and other substances)

2D. Empower patients using sustainable educational interventions that include their support system. When possible, use the patient’s primary language and consider their cultural background, religion, accepted behaviors, taboos, and beliefs

In resource-limited environments, patient-centered concerns and barriers to clinical outcomes are crucial for providers to understand and address within the context of cultural, spiritual, and religious beliefs of the respective community.

Wound healing disparities exist among Indigenous populations across the globe. These disparities are often rooted in historical and ongoing socioeconomic, cultural, and healthcare-related factors. Cultural diversity and societal pressure also often dictate formal resource allocation processes to certain health sectors. Some key barriers to wound healing among Indigenous populations include historical trauma, socioeconomic disparities, limited access to healthcare, cultural barriers, chronic health conditions, cultural healing practices, geographic isolation, and healthcare system bias.36 Many cultures have an honor system in managing their sick, older adult, and chronically ill members. These principles are easier upheld if sufficient resources are available to maintain them.

Many studies have identified a major medical illness as one of the core reasons a family can incur large debts.37,38 Even in government-run clinics, additional dressing materials or medicines may be charged to the family. Patients and family members may therefore resort to alternative treatment methods (nonallopathic medicine) from local/Indigenous/traditional healers. Although often less costly, these healers may not have the necessary skills or expertise in managing chronic wounds, leading to deterioration.

Loss of independent mobility because of wound chronicity is another major factor that impacts attendance and regular follow-up. Transport availability varies in resource-restricted environments, and walking may be the only way to access a public transport pick-up point. Secluded rural environments are often affected the most and require traveling significant distances to reach a formal healthcare facility.

The social health of the family environment and willingness to incorporate a person with healthcare needs can drive the quality of care/self-care rendered as well as patient safety within a home environment. Because of the social structure and milieu in various countries, family support and social support may differ by culture. Often, as time passes, the financial burden increases; patient independence and activities of daily living (ADLs) achievement deteriorates; dressing changes become more challenging; and caregivers become stressed, fatigued, and exhausted.39 Late referrals and critical/terminal patient conditions when eventually presenting to formal care are additional aggravating social and behavioral factors that can compound poor wound healing outcomes.

Individuals with wounds treated at home need a designated space to themselves. Wound odor, persistent pain, and a different routine are the main stressors on both the patient and family in settings where space is at a premium. The mere presence of a major skin wound already negatively impacts the patient’s own social interactions, relationships, sexuality, and self-confidence. This leads to progressive anxiety and depression that may bring about pessimism regarding perceived treatment benefits. Subsequently, patients have lowered self-efficacy that is often associated with further wound deterioration including eventual lower-extremity amputations.40

The real challenge occurs when lifestyle modifications are needed. This often requires additional resources or tailor-made education to construct self-care plans.40,41 The need for health education and lifestyle modification interventions to have clear rationales cannot be overemphasised. Lifestyle interventions may become a financial, social, and logistical challenge, first to acquire and then to maintain within any restricted living domain. Further, it is a vital step to ensure that any financial help received is correctly allocated to the family member with a wound.

A biopsychosocial approach is necessary in managing wound care for patients in resource-restricted environments. The wound care team, beyond managing the wound, must address the social stressors/factors affecting the patient. Each patient will need a unique, mutually agreed-upon management plan that fits their constraints (medical, financial, family, social, and emotional support).40

Statement 3: ability to heal

3A. Healable wound: Determine if adequate blood supply is present for wound healing and that appropriate treatment is available to address the underlying cause(s)

3B. Maintenance wound: Adjust practice if adequate blood supply is present for wound healing but the patient cannot adhere to the plan of care and/or the healthcare system does not have the required resources

3C. Nonhealable wound: Determine alternative wound treatment(s) if blood supply is inadequate and/or the underlying cause cannot be corrected

The process of determining the healing classification of a wound begins with a thorough patient history and physical examination. Identifying the underlying cause(s) of the wound is important. Addressing the underlying cause(s) is the first step to developing an achievable management plan.

In some cases, chronic wounds may also become stalled and fail to achieve the wound edge advancement over the set time; these are known as hard-to-heal wounds. They often fall into the maintenance category but, with additional assessment, may be healable with a re-evaluation of the patient, history, causes, and treatment plan.3,42

Patient-centered concerns and expectations need to be identified, compared with, and aligned with institutional/clinician resource availability, skills, and immediate intervention options that are available.3,42 The management plan is based on the assigned healing classification, which may change.

Protect nonhealable wounds against tissue loss, deep and surrounding wound infection, and general deterioration from a wet wound environment. Decreasing moisture is a priority. Maintenance wounds also need protection against further tissue losses with dry wound bed management and local infection controls as the mainstay. Tissue protection may also be a temporary measure until resources become available and additional patient factors are controlled to achieve full optimisation.

Stalled but healable wounds (hard-to-heal) need a second chance to achieve edge advancement with urgency in reassessment and interprofessional team intervention as the highest priorities.3,42

Statement 4: local wound care: examine, measure and monitor

4A. Document wound progress from baseline to establish measurable healing trajectories (paper-based and/or photoimaging, if available).

4B. Cleanse wounds with tepid (preboiled) potable water, saline, or low-toxicity antiseptic agents. Consider soaks, compresses, and irrigation, where appropriate.

4C. Reassess and document wounds regularly at appropriate intervals over time with available resources. Document and maintain confidentiality of the data.

Wound assessment documentation is an integral component of healthcare practice. It is instrumental in ensuring the delivery of high-quality patient care, monitoring wound status, and providing direction for any changes in wound interventions. The comprehensive and accurate recording of wound assessments is essential to ensure improved patient outcomes, effective communication among healthcare professionals, and legal and regulatory compliance.43

Monitoring progress. Wound assessment documentation serves as a historical record of the wound’s progression over time. By regularly documenting wound characteristics, including size, depth, color, exudate, infection, tissue type, and so on, healthcare professionals can track changes, identify potential complications, and adjust treatment plans. If photo documentation is used, obtain patient consent according to organisational policy, ensure appropriate technique with adequate lighting and appropriate distance from the wound, and include a measuring guide in the photo.44 This ongoing evaluation is critical for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions and making informed decisions regarding wound management. When measuring surface area or volume, it is imperative to use a consistent technique regardless of technology.

Communication. Accurate wound assessments facilitate effective communication among healthcare professionals. When all team members have access to consistent and up-to-date wound documentation, they can work together to develop and implement a coordinated care plan, ensuring patients receive the best possible treatment. It is vital to use consistent terminology that is common to all disciplines. The International Classification of Diseases medical classification system is an example of a globally applicable standard.45

Legal and regulatory compliance. Proper wound assessment and documentation are essential to meet legal and regulatory requirements. Inaccurate or incomplete records can lead to legal issues and negatively impact a healthcare professional’s practice, even in resource-limited environments.

Reimbursement. In many healthcare systems, proper wound assessment documentation is tied to reimbursement-based funding models. Accurate and detailed records are often necessary to justify the use of specific wound care products or procedures and ensure organisations receive adequate reimbursement for services rendered.

Research and quality improvement. Wound assessment data are a valuable resource for research and quality improvement initiatives. This continuous learning process helps improve global wound care and patient outcomes.

Patient-centered care. Proper wound assessment and documentation are an essential component of patient-centered care. It ensures that patients’ conditions are thoroughly evaluated and their treatment plans are tailored to their specific needs. When patients observe that their healthcare provider is committed to documenting and monitoring their wounds, it can enhance trust and patient satisfaction.

To promote language consistency and enhance data clarity, an increasing number of enterprises are creating electronic wound assessment software and applications to reduce the time required for thorough documentation.43 These programs and applications (some more affordable than others) can provide the healthcare team with a structured set of parameters to ensure all clinical features are documented, thereby enhancing overall communication.46 Although these tools are an asset to healthcare professionals, they are not without risk, such as incorrect copying and pasting from previous reports/consult notes or patient data security risks. In areas where such programs and applications are not available, updating

the patient and providing written assessment and intervention plans may be warranted.

Statement 5: local wound care: debridement

5A. Healable wounds/cause corrected: Consider active sharp surgical debridement to bleeding tissue with adequate pain control only if it is within your scope of practice. This is undertaken with guidance from advanced wound care expertise only. If not available, consider conservative (sharp) debridement

5B. Maintenance wounds/nonhealable wounds: Consider conservative (sharp) debridement with adequate pain control only if it is within your scope of practice. Only remove loose hanging slough/debris when indicated and without causing any bleeding

5C. Determine if alternative debridement modalities for healable wounds are available (eg, autolytic, mechanical, enzymatic, and maggot biological options)

Debridement is an important process in the WBP paradigm to remove necrotic tissue and other biomaterials, including biofilm, in healable wounds and prevent odor and infection in maintenance wounds. For all wounds located below the knee, communicate the outcomes of any vascular testing (eg, ABPI, waveform) to all members of the interprofessional team, and document accordingly before attempting debridement because many types may be deleterious to the wound bed with reduced vascular supply.

For healable wounds, local wound bed interventions are best determined via the WBP paradigm based on the patient and wound characteristics. Consider surgical debridement (to bleeding tissue) as a first-line intervention. However, in many rural and remote regions, access to a skilled healthcare professional with the necessary education, knowledge, and judgment for this procedure may not exist.

Conservative (sharp) debridement (without causing bleeding) requires advanced knowledge and skills and is more suitable for nonacute care or specialty clinic settings. Only remove loose hanging or unattached debris from the wound without causing trauma to the wound bed.

Clinical sterile maggot debridement therapy is a limited treatment modality in resource-restricted environments, except in cases of accidental exposure. Maggot infestation is often discovered during dressing changes. Good debridement outcomes may result from accidental maggot therapy, particularly if the larvae are from the highly selective Lucilia sericata/cuprina bottlefly source, as they focus on devitalised tissue as their food source.47,48 Detrimental outcomes may present if the infestation is from the ordinary housefly (Musca domestica) or other invader species, as those larvae may indiscriminately destroy healthy tissue.47,48

Healthcare professionals should assess alternative methods of debridement (eg, autolytic, enzymatic, mechanical) for community sectors, including primary care, home care, and long-term care. Within available resources it is vital to consider patient safety, assess environmental factors, and identify barriers to wound healing before initiating debridement.

Appropriate debridement protocols for maintenance and nonhealable wounds differ significantly from those for healable wounds. Although moist wound healing provides an optimal environment for wound healing, it is a form of debridement (autolytic) that may be detrimental to nonhealable and maintenance wounds. Debridement is generally not a suitable intervention for stable maintenance or nonhealable wounds, because the goal is to keep those dry and free of infection.49 Consider debridement only when a maintenance or nonhealable wound becomes unstable to remove infected or necrotic wound debris in the most atraumatic manner possible.

Patient goals typically include enhancing comfort, minimising wound-related odor, reducing pain, and improving ADLs. Keeping the wound dry enables the formation of a protective layer, whereas debridement carries the risk of removing this protective layer and introducing pathogenic organisms.

Statement 6: local wound care: infection and inflammation

6A. Treat local/superficial wound infection (three or more NERDS criteria) with topical antimicrobials

6B. Manage deep and surrounding wound infection (three or more STONEES criteria) with systemic antimicrobials and concurrent topical antiseptics

6C. Consider anti-inflammatory agents in wounds with persistent ongoing inflammation (topical dressings or systemic medication)

The validated NERDS and STONEES criteria can guide the assessment and treatment of infection and inflammation in chronic wounds.50 Base the diagnosis of infection on clinical signs and symptoms rather than superficial wound swabs, which should be used only to guide antimicrobial selection in the event of an infection. If deep and surrounding tissue infection is suspected, identify the bacterial species and their sensitivity to commonly used antibacterial agents to help guide systemic antimicrobial use. This is especially true if a deep and surrounding infection is not responding to the empiric treatment.

The best tissue samples for wound bed culture swabs are obtained after cleaning the wound with potable water or saline and sampling the wound base without debris. A culture from tissue samples using a curette or other biopsy technique is most likely to represent the organisms in the wound tissue. Alternately, a semiquantitative swab technique using the Levine method can correlate to tissue biopsies.51 The swab is placed on granulation tissue and pressed enough to extract wound exudate and then rotated 360° to cover all surfaces of the swab. Placing the swab in the transport media to premoisten it prior to placing the swab on the skin may increase the bacterial yield for patients with low-exudate wounds.52

Pathogenic bacteria may infiltrate to the bone and cause osteomyelitis, which derails healing potential and is challenging to cure. A bone biopsy is the criterion standard to diagnose suspected osteomyelitis, because superficial cultures do not access the deep bone tissue, and imaging is limited by variable specificity.53 However, a bone biopsy may be uncomfortable, is dependent on skilled clinicians, and may extend the tissue damage. For these reasons, it frequently is not a feasible option, even more so if resources are scarce.

When deep wound infection is confirmed, antimicrobial dressings are appropriate to locally support systemic antibiotic therapy and prevent spread to the deep and surrounding compartment from surface bacteria. The five most common choices of antimicrobial dressings are silver, polyhexamethylene biguanide, iodine, methylene blue/crystal violet, and honey. Of these, silver and honey have additional anti-inflammatory properties.54

In some wounds, broad-spectrum antiseptics are applied for short-term rapid bacterial burden reduction to support systemic antibiotics. When the risk of infection outweighs the cytotoxic properties, low-cost povidone-iodine-moistened gauze changed daily over exposed bone can reduce surface bacteria. This is a short-term strategy accompanied by clinical evaluation for serum thyroid function levels especially when wound surfaces are large. However, with the newer low-toxicity antiseptics, other options are now available that are less aggressive but equally effective.

In general, wounds in immunocompetent patients that present for less than 1 month are treated with agents for Gram-positive coverage. Polymicrobial infections (typically seen in PWDs) or wounds longer than 1 month in duration call for broad-spectrum agents with Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic coverage because these patients are often also immunocompromised.55

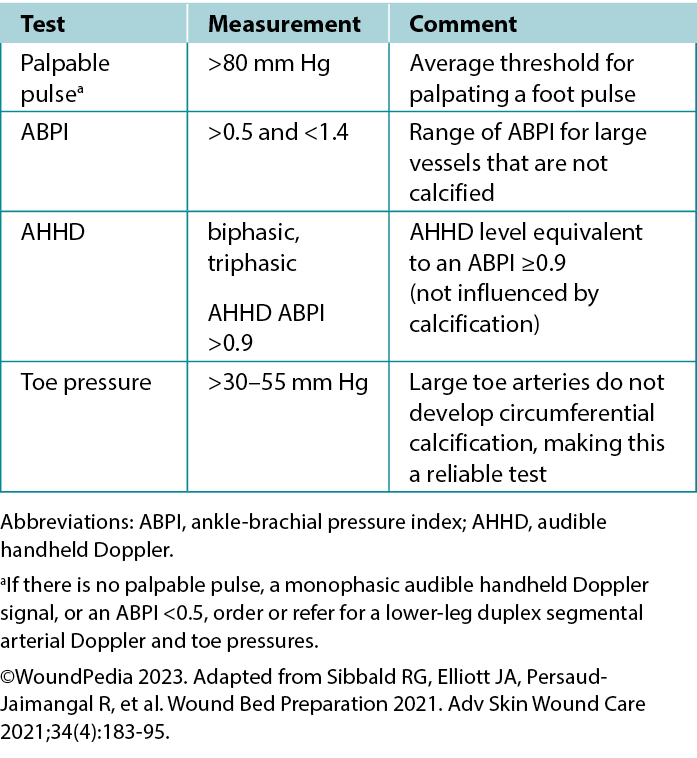

Cytotoxic agents may be appropriate for nonhealable wounds if the need for topical antimicrobial action is greater than the tissue toxicity. Antiseptics are generally preferred over topical antibiotics as part of antibiotic stewardship because of a lower risk of systemic bacterial resistance and adverse effects associated with contact irritant or contact allergic dermatitis.54

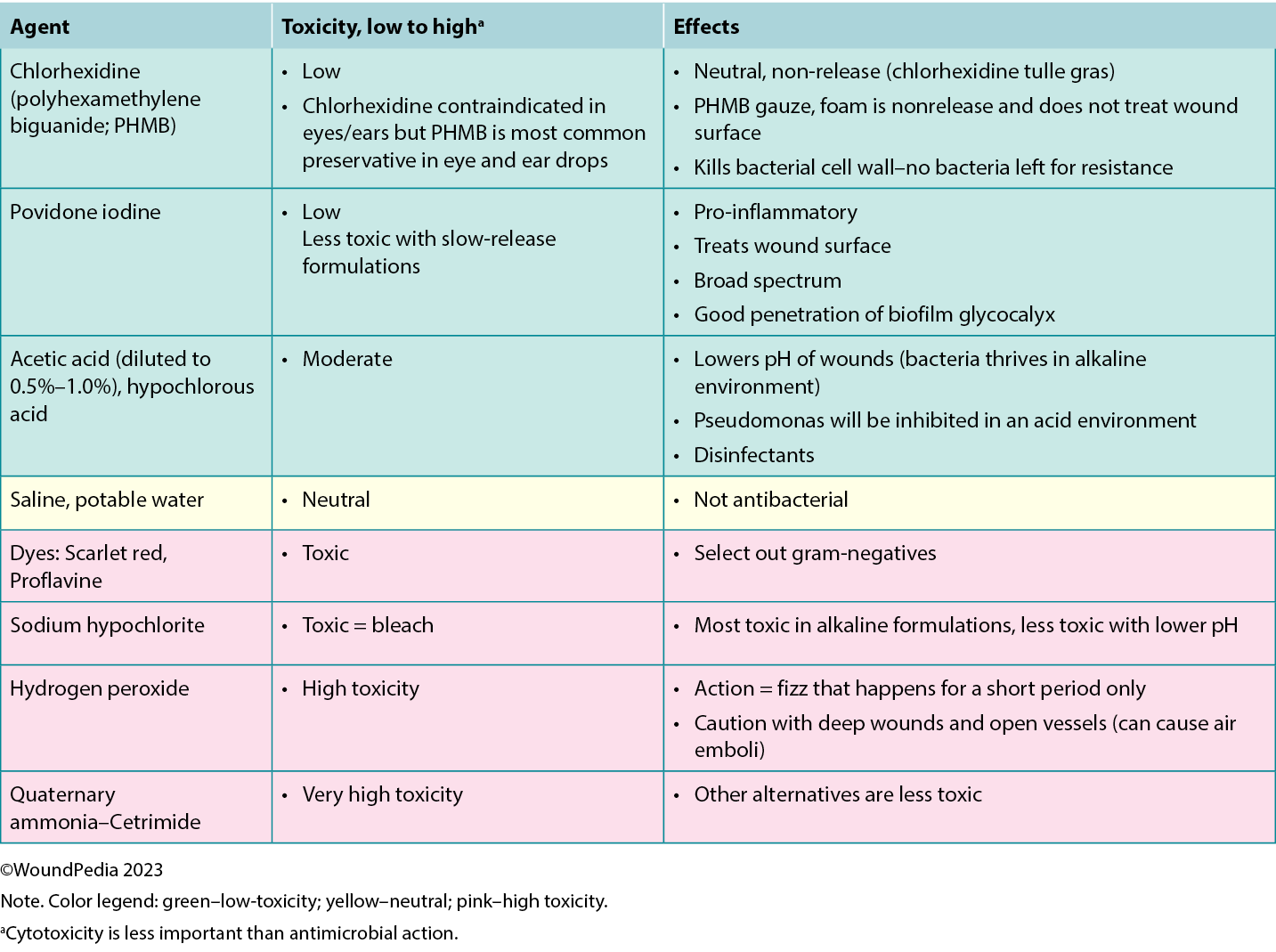

6D. Gently cleanse the wound with low-toxicity solutions (water, saline, noncytotoxic antiseptic agents).

The cleansing solution used depends on the characteristics of the wound and availability in practice. There is poor consensus in the literature on wound cleansing recommendations. An updated 2021 Cochrane review on cleansing solutions of venous leg ulcers concluded that there is a lack of randomised controlled trial evidence “to guide decision-making about the effectiveness of wound cleansing compared with no cleansing and the optimal approaches to cleansing of venous leg ulcers.”56 However, general wound care principles involve low-toxicity solutions including potable or preboiled water, saline, and other wound-friendly antiseptic agents.57 This avoids cytotoxic effects and damage to healthy granulation tissue in healable wounds.

Acetic acid diluted to 0.5% to 1.0% or hypochlorous acid can also be used in some cases in which an acidic environment is preferred (eg, for topical treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa).58 Based on the healability classification of the wound, antiseptic agents with some tissue cytotoxicity may be used after a positive risk-benefit assessment. This includes agents such as low-concentration chlorhexidine or its derivative polyhexamethylene biguanide and povidone-iodine. This may be beneficial in cases of maintenance and nonhealable wounds that have a high potential for infection. Further, these agents can be used to manage odor and exudate in addition to controlling bioburden. In resource-limited environments, consider wound hygiene measures and how solutions are prepared, stored, and distributed to patients to prevent cross-contamination.

There is emerging interest in the use of surfactants to remove biofilms that often exist within wound debris and have two surfaces of different viscosity (Supplemental Table 2, http://links.lww.com/NSW/A177). Wound irrigation remains a controversial topic for use in chronic wounds. However, expert opinion is not to irrigate wounds if the base of the wound is not visible to avoid accumulation of the irrigation solution in closed spaces and accidental enlargement of the wound.57 Irrigate wounds with an adequate solution volume (50-100 mL per centimeter of wound length).59

Statement 7: local wound care: moisture management

7A. Maintain moisture balance in healable wounds with hydrogels, films, hydrocolloids, hydrofibers, alginates, and foams

7B. Institute moisture reduction with fluid-lock mechanisms in healable wounds using superabsorbents to wick moisture away from the surface (diaper technology)

7C. Determine if wound packing is needed for healable wounds. It could be wet (donate moisture) or dry (absorb moisture)

7D. Establish a targeted moisture reduction protocol in maintenance and nonhealable wounds to reduce bacterial proliferation

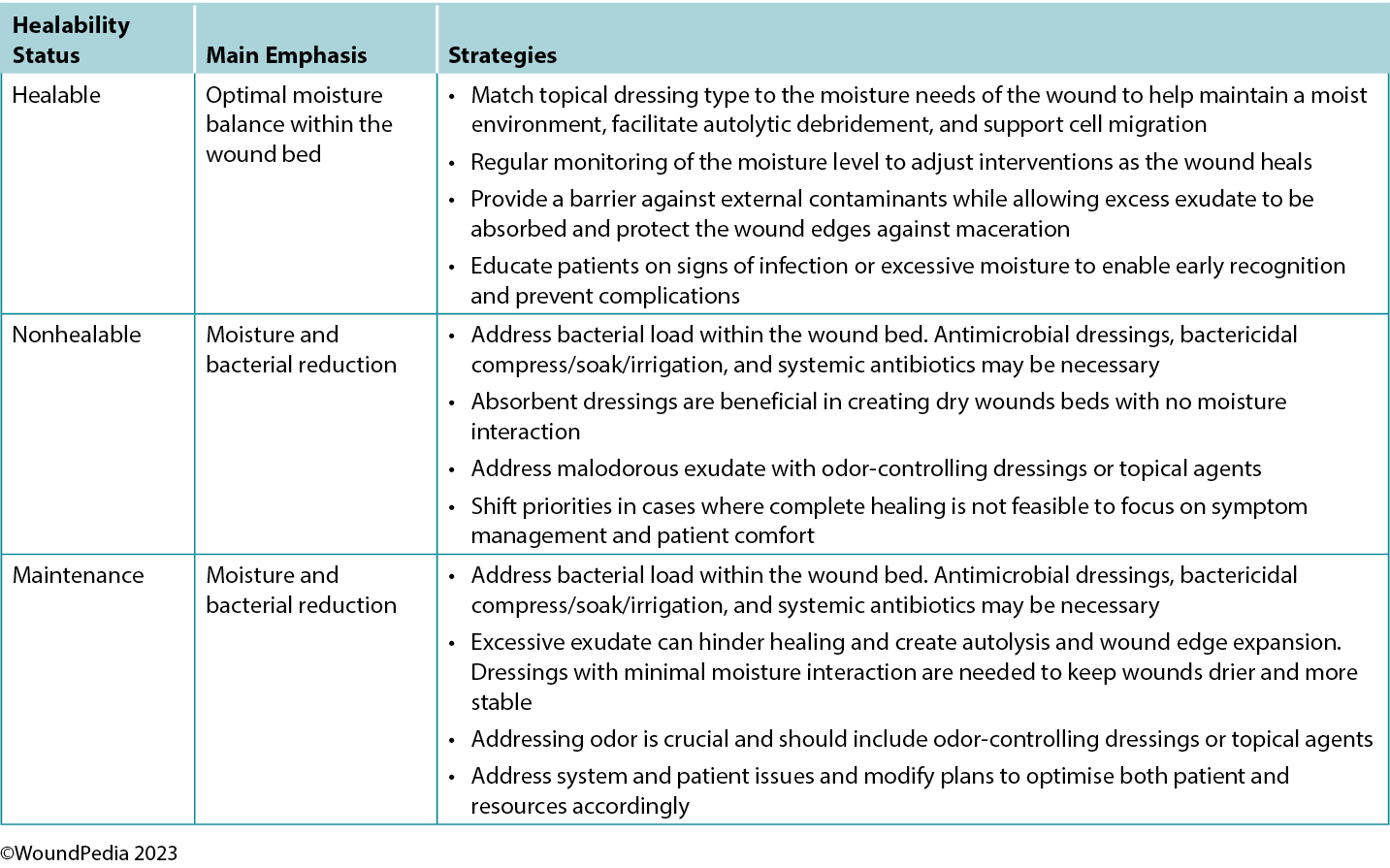

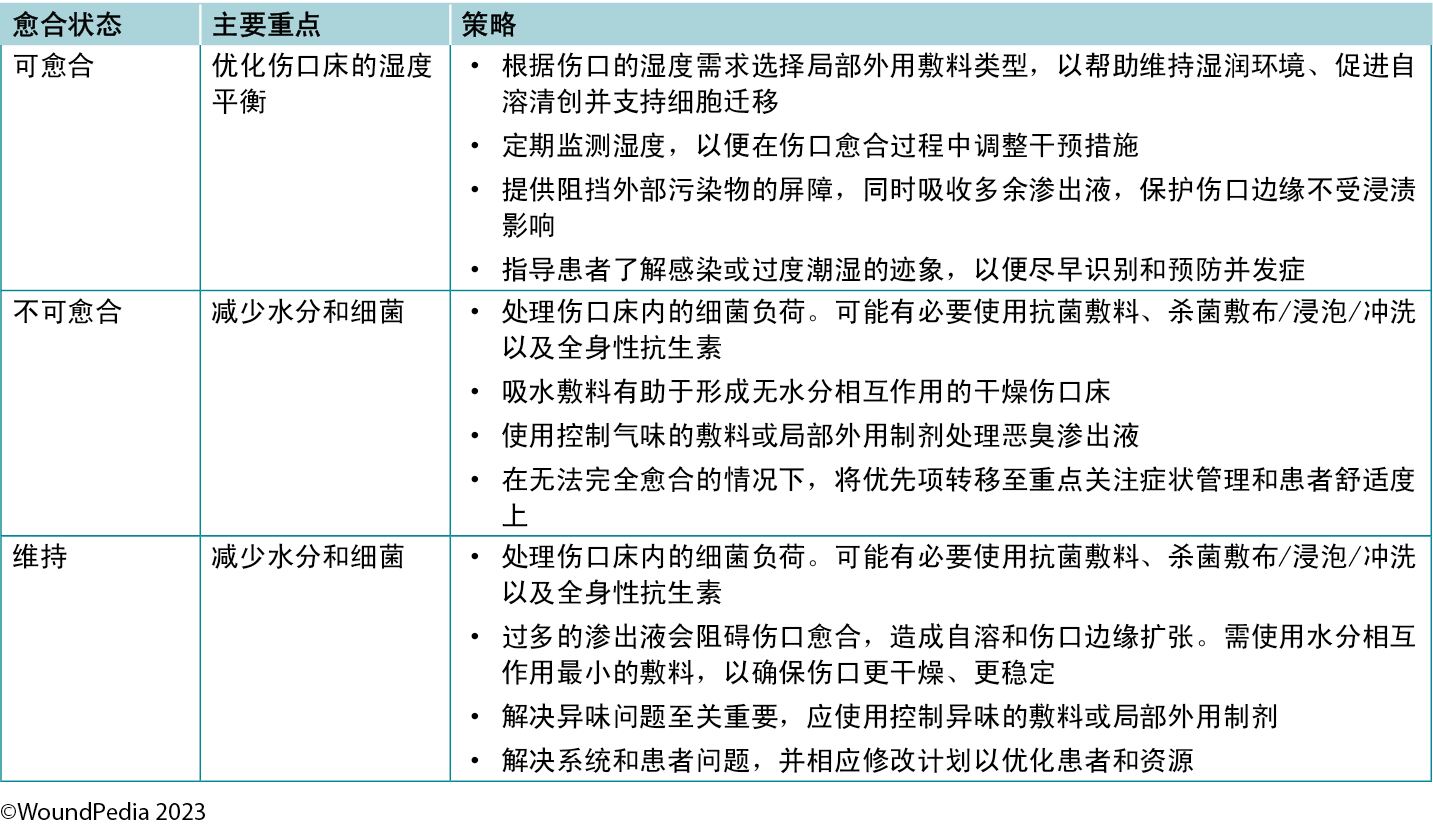

Maintaining moisture balance is complex and depends on the wound type and healing classification. Consider moisture balance, infection control, and patient education in selection of dressing materials.60 Incorporating and tailoring moisture management strategies to the specific wound type and the resources available can optimise patient outcomes and minimise complications (Table 6).3,54 Further research and clinical studies should continue to refine our understanding of wound moisture management to enhance wound care practices in the future.3,54

Table 6. Goals of moisture management based on wound healability3,42,54

In general, as the level of exudate increases, so should the moisture absorbency or transferring capability of the dressing.3 Moisture-balance dressing options can be combined with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties to further meet the wound needs.

The choice of dressing for maintenance and nonhealable wounds should prioritise comfort while avoiding fluid donation to the wound bed and maceration of the wound edges. These wounds require regular reassessment for any progress or deterioration and should be managed to reduce bacterial load. Depending on wound evolution and characteristics over time, dressings may need to be adapted.

Statement 8: Healing trajectory

8A. Consider that healable wounds should be at least 20% to 40% smaller by week 4 to heal by week 12. If factors are present that affect healing time (poor glycemic control, for example), additional healing time may be required

8B. Allocate additional time to healing beyond 12 weeks in healable wounds if there are limited available resources, and continue with consistent care

8C. Prioritise referral to specialist centers (when available) for diagnostic testing and/or a skin biopsy, especially when faced with severe resource restrictions

Wound healing trajectories are useful and necessary for evaluating the needed time to heal, especially using clinical data (measurements) for both acute and chronic wounds. The healing trajectory is based on accurate and consistent wound measurements that determine the wound surface area closure over time. This helps to distinguish wound progression, stalled wounds, and worsening wound status.

Healable acute wounds should be completely closed within 30 days. Expect chronic healable wounds to have a 20% to 40% edge advancement at 30 days (4 weeks) and to close within 12 weeks.3,42,61,62 Nonhealable wounds have no defined time allocated to close, no edge advancement is expected, and all initiated steps are to prevent further deterioration. Maintenance wounds are not expected to heal nor deteriorate, and wound healing may progress slowly without a fixed time expectation unless patient/institution/system optimisation is achieved.

Re-evaluate hard-to-heal wounds periodically for alternate diagnoses. In these cases, consider wound biopsy, further investigation, and/or referral to an interprofessional assessment team. A healing trajectory can be assessed in the first 4 to 8 weeks to predict if a wound is likely to heal by week 12, provided there are no new complicating factors.63 Changes in the wound, the individual, or the environment may necessitate the reclassification of a wound to the maintenance or nonhealable category.

Statement 9: Edge advancement

9A. Consider locally constructed active modalities according to the required mechanism of action and the specific indications for initiating an adjunctive therapy to support wound healing

9B. Decide on adjunctive therapies through an interprofessional team approach and include a prior risk-to-benefit analysis

Select adjunctive therapies according to healability. Initiate these as soon as possible after injury in persons with major trauma to prevent sequelae of long chronicity. Select modalities using an interprofessional team approach based on what is available and the physical mechanism required (while ensuring trauma tissue healability). In hard-to-heal wounds, the wound may need a second chance to heal after reassessment.42 Ensure informed consent is a part of adjunctive therapy decisions.

A risk-to-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis is helpful and will add in system sustainability. The key to effective adjunctive modality decisions is based on the risk it poses to initiate the therapy (physical discomfort, financial hardship, patient adherence) versus the benefit it will provide (tissue oxygenation, wound contraction, edema reduction, cellular reactivation).42,64 The best risk-benefit decisions are made within an interprofessional team including the patient, ensuring group commitment and treatment completion within optimal use of resources.

Optimising resources, or the slight repurposing thereof, may lead to creative strategies in the hands of interprofessional teams to tailor-make solutions to ensure all patients are optimally treated despite resource restrictions.

Surgery. Even in the most restricted environments, this is the one modality that is mostly available within a medical catchment area, often in tertiary care settings with referrals received from primary care clinics to provide debridement, general surgery with primary/tertiary intention closure, skin grafts, and/or amputations.

Skin grafts may be available in resource-restricted environments as an advanced modality to achieve tissue closure to reduce healing times and prevent recurrent deep wound infections. The procedure can minimise the extensive use of dressing materials over a prolonged period and reduce primary care chronic wound workload. Skin graft decisions are often made to preserve body functionality and promote early wound closure above aesthetic outcomes.65 However, avoid skin grafts for ischemic wounds and most venous stasis ulcers; consider them only in wounds where a favorable outcome could be expected.66,67

Electrical stimulation. Wound healing can be accelerated by enhancing the natural electrical current present in injured skin. In resource-limited environments, this modality should be investigated for wound healing because of its high-level evidence base and availability of devices of this nature (direct current, alternating current, low-intensity direct current, pulsed electromagnetic fields, high-voltage pulsed current, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation devices). The evidence supports increased cellular proliferation and increased microcapillary perfusion, as well as a reduction in bacterial burden and infection on treated wound beds.68

Wall-mounted negative-pressure wound therapy. This can give the healthcare professional control over exudate management and accuracy in fluid replacement for inpatients with high exudate and large tissue defects. Start with the lowest possible pressure (minus 50-80 mm Hg). The patient becomes bedbound for the modality to be maintained, and the base layer (often gauze or petrolatum-impregnated dressings) needs to be replaced at least daily. This, together with starting on the lowest possible negative-pressure setting, will prevent mechanical trauma to the wound bed from tissue adherence and traumatic dressing removal in cases where nonadherent base layers are not available.69 There are now disposable negative-pressure wound therapy devices designed for use in the community as well as do-it-yourself options that can render acceptable clinical outcomes.70,71

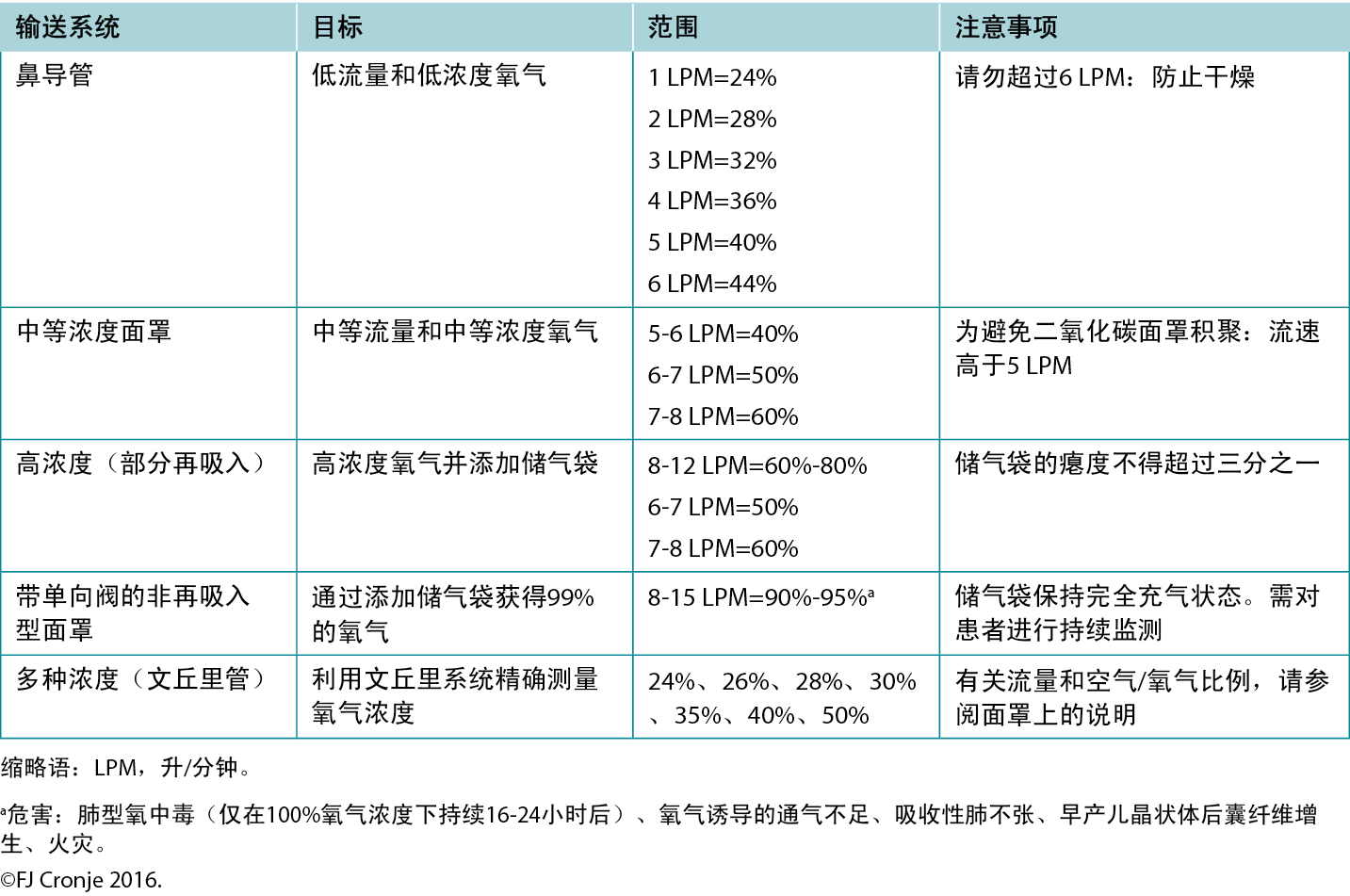

Breathing high-flow, highly concentrated oxygen. Oxygen is often overlooked as a legitimate wound healing modality.72 Ironically, it is rarely used, although nearly all formal healthcare settings have copious amounts of oxygen available, even in relatively resource-poor environments. The availability of oxygen concentrators has also increased because of the COVID-19 pandemic, making oxygen administration also a possibility on an outpatient basis in home-based settings.73 Although hyperbaric oxygenation is the most effective means of increasing plasma oxygen concentration and tissue oxygen delivery, this modality is not always readily available. However, providing normobaric (ward) oxygenation still produces a 7.5-fold increase in plasma-borne oxygen (ie, from 0.3 mL/dL to 2.3 mL/dL; Table 7).74 Moreover, intermittent inhalation of 100% oxygen in patients without chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (eg, 6 hours on/2 hours off by nonrebreather mask) over 3 to 4 days is not harmful to the lungs and may provide significant additional oxygen substrate, while the intermittent increase and decrease in oxygen delivery activate the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (a strong stimulus for angiogenesis).75 This would suggest that in lieu of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, normobaric oxygen is justified for mitigating conditions on the FDA-approved list of indications for hyperbaric oxygen (Table 7).76 This may include tissue reperfusion injuries (eg, crush injuries, compartment syndromes before and after surgical release); bacterial toxin inhibition (ie, infective myonecrosis or other anaerobic infections); or large-tissue defects (after debridement to maintain the reactivated inflammatory response for up to 48 hours). Normobaric oxygen provides 50% of the Po2 of typical hyperbaric oxygen therapy (at 2 atmospheres); however, many of the pharmacologic effects of oxygen are achieved only under hyperbaric dosages.77,78

Table 7. Normobaric oxygen therapy mechanisms and delivery systems

Note that topical oxygen administration directly to a wound does not have the same physiologic effects attributed to systemic oxygen delivery.79 Topical oxygen delivery systems remain subject to ongoing research to determine their beneficial actions beyond improved epithelialisation and possibly a mild antiseptic effect.64 The latter effect has also been attributed to ozone therapy.80 A systematic review completed in 2018 indicated that these therapies could potentially elicit mild oxidative stress or disinfection but that the risk of toxicity due to uncontrolled reactive oxygen species is high.81 Within the limited-resource environment, these devices and use thereof are likely uncontrolled.

Statement 10: Healthcare system change

10A. Facilitate evidence-informed, culturally competent, and equitable care for all patients

10B. Improve provider skills for wound management competency to enhance patient outcomes

10C. Establish timely and effective communication that includes the patient and all interprofessional wound care team members for improved healthcare system wound outcomes

Globally, chronic wound management consumes a significant portion of healthcare resources; preventive care represents the most cost-effective strategy for reducing healthcare system expenditures. There are numerous approaches to integrating preventive care into practice. For instance, DFUs are notorious for leading to high amputation rates and morbidity worldwide, even though many DFUs are preventable. Although diabetes was initially believed to be most prevalent in developed countries, it is noteworthy that 80% of diabetes-related deaths occur in countries with limited resources.82 A validated screening tool, an educated and available interprofessional team, and the implementation of prevention algorithms can be used in countries regardless of the availability of resources.83-85 Other organisational strategies that could be implemented include the following.

Patient navigation. Managing a DFU requires continual support from a circle of care that includes family members and healthcare professionals (including home care and wound care) working as a team. Timely access to both health and social services is often necessary to prevent and heal DFUs. Regionalised, community-based integrated diabetes services linked to interprofessional wound care clinics are proving to be most successful.86

One effective way to ensure optimal and timely care is patient navigation. This concept is adaptable to all healthcare sectors and can improve the timely diagnosis and treatment of wound infections, optimise pain management, and increase access to specialised care, thereby expediting wound closure rates.87 Patient navigation is becoming a vital component of integrated care, facilitating seamless transition between sectors and enhanced clinical outcomes. Further, it is accompanied by a boost in morale for both patient and healthcare professional, decreased nonacute hospital admissions or readmissions, enhanced patient quality of life, and improved adherence to treatment protocols. All these factors combined generate significant cost savings to healthcare systems.87,88

A critical element of successful patient navigation programs is the inclusion of a comprehensive and systematic approach to guide healthcare professionals in assessing and delivering care to each individual patient (eg, the WBP framework). These pathways do not need to be complicated or time consuming, but should ensure specific criteria are met, including regular foot care for those at high risk of amputation, glycemic control to an HbA1c less than 9%, and a BP less than 130/90 mm Hg.23,89

Policy interventions. Organisational policies that detail and provide guidance on best practice interventions and pathways are crucial for the successful and sustainable implementation of wound care protocols. Base these policies on current published guidelines for each specific wound type and translate them into the environment they need to serve. The institution needs to accept them as standards of practice and be approved as such to serve as evidence-based care in environments in which other guidelines may not be successfully adopted because of cultural or language translation challenges. Further, these policies must clearly outline the process for entering and using data, as ongoing quality improvement initiatives are based on data to improve and maintain effective care processes.

Adapted wound care. Although the delivery of care should be adapted to the unique needs of each healthcare sector, certain concepts should be standard, particularly those that enhance effective communication both within and across sectors. The increased adoption of digital technology expedites assessments, enhances access to specialised care, and optimises the allocation of limited resources.90 Where adaptations are implemented as care processes, these practices should be well documented as care standards and be easily accessible to ensure consistency and continuity of care within respective institutions.

Delphi consensus highlights

Some important comments from the panel:

- The ability to heal (healability) is a changeable modality and not to be seen as a static classification as patient condition, circumstances, and choices drive the classification allocation process (3A).

- The adjustment of practice as required in maintenance wounds incorporates the establishment of a conservative wound bed approach, with attention to the allowances the patient is willing to make within their life choices to slowly ensure patient optimisation and subsequently increase host competence (3B).

- When the method of patient documentation is agreed upon within an institution, it should be uniformly used to prevent communication gaps between providers that may inadvertently cause a negative impact on patient care outcomes (4A).

- Antiseptic mouth washes suitable for mucosa are often also friendly for use on a wound bed (4B). This may be considered off-label use.

- The choice for topical bacterial burden control should be on topical (low) toxicity antiseptics (the five most important ones), depending on the ability to heal and bacterial burden priorities to be addressed. Refrain from using topical antibiotic preparations, ointments, and creams on chronic wounds because those preparations are often focused only on Gram-positive organisms and would allow Gram-negative and anaerobic organisms on the wound bed to multiply freely. Further, topical antibiotic preparations need only one mutation to create systemic resistance to the targeted organism. Topical antibiotics are often in a carrier medium that is associated with contact irritant or contact allergic dermatitis (6A and 6B).

- When a healable wound has a significant moisture burden and remains in need of superabsorbent dressings to control the moisture balance of the wound bed, the wound needs thorough reassessment to ensure all underlying causes have been corrected for (7B).

- In establishing an interprofessional team, use any means of communication to build and maintain such a team as that could significantly optimise local capacity despite distances between providers and specialists to increase clinical outcomes despite local limitations (9B).

Conclusions

Optimise chronic wound care in resource-limited environments by initiating small adaptations and creative interventions without compromise to the core principles of care required. Interprofessional wound care teams can serve as a virtual resource to isolated and remote communities to improve clinical outcomes. All of the critical elements for (diabetic) foot management and care can easily be incorporated into diverse environments by increasing local capacity and providing clinician education and culturally appropriate patient empowerment.

Practice pearls

- The holistic care of PWDs includes the optimisation of HbA1c levels, BP, cholesterol levels, and drugs with cardiac- and renal-protective properties.

- The audible handheld 8-MHz Doppler pulse signal is a suitable bedside test for arterial blood supply to the lower limbs. It can be performed as a modification of the traditional ABPI, and the pulse sounds are easy verifiable by remote expert team members using MP3 or MP4 recordings from a cellphone.

- The NERDS and STONEES mnemonics can guide diagnosis and treatment of local/deep and surrounding infection, including an oral antibiotic indication for osteomyelitis.

- Plantar pressure redistribution can be accomplished from innovative, less costly alternatives such as soft felted simple inserts, to the total contact cast and removable cast walker made irremovable if the latter are unavailable or unsuitable for patient preferences or ADLs.

- Integrated coordinated care teams can connect with virtual expertise by equipping healthcare professionals with skills in patient navigation.

- Toolkits containing enablers for practice along with 8-MHz Dopplers and infrared thermometers can facilitate care in resource-limited settings.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

伤口床准备2024:在资源有限的环境中进行脚部溃疡管理的Delphi共识

Hiske Smart, R Gary Sibbald, Laurie Goodman, Elizabeth A Ayello, Reneeka Jaimangal, John H Gregory, Sadanori Akita, Afsaneh Alavi, David G Armstrong, Helen Arputhanathan, Febe Bruwer, Jeremy Caul, Beverley Chan, Frans Cronje, Belen Dofitas, Jassin Hamed, Catherine Harley, Jolene Heil, Mary Hill, Devon Jahnke, Dale Kalina, Chaitanya Kodange, Bharat Kotru, Laura Lee Kozody, Stephan Landis, Kimberly LeBlanc, Mary MacDonald, Tobi Mark, Carlos Martin, Dieter Mayer, Christine Murphy, Harikrishna Nair, Cesar Orellana, Brian Ostrow, Douglas Queen, Patrick Rainville, Erin Rajhathy, Gregory Schultz, Ranjani Somayaji, Michael C Stacey, Gulnaz Tariq, Gregory Weir, Catharine Whiteside, Helen Yifter, Ramesh Zacharias

DOI: 10.33235/wcet.44.1.13-35

摘要

背景 低资源环境中的慢性伤口管理值得特别关注。农村或资源不足的环境(即基本需求/医疗保健供应有限、跨专业团队成员不稳定的环境)可能无法应用或复制城市或资源丰富的环境所采用的最佳实践。

目的 作者汇集了世界范围内的专业知识,为缺乏所需资源的社区开发一种具有科学性的实用伤口床准备模式。

方法 来自15个国家的41位伤口专家组成的小组就资源有限环境下的伤口床准备工作达成了共识。

结果 关于10个关键概念的每项声明(32项子声明)均达成了88%以上的共识。

结论 共识声明和基本原理可以指导低资源环境中从业人员的临床实践和研究。这些概念应促使我们不断创新,改善所有脚部溃疡患者,尤其是糖尿病患者的治疗效果,提高医疗保健系统的效率。

总体目的

回顾一种具有科学性的实用伤口床准备模式在缺乏所需资源的社区中的应用情况。

目标受众

本次持续教育活动的预期对象是对皮肤和伤口护理感兴趣的医生、医生助理、执业护士和护士。

学习目标/结果

参加本次教育活动后,参与者将:

1. 总结与伤口评估相关的问题。

2. 确定一类经证明可改善血糖、肾脏保护和心血管结局的II型糖尿病治疗药物。

3. 整合伤口管理策略,包括在资源有限的情况下进行治疗。

4. 说明慢性可愈性伤口边缘推进的目标时间。

引言

2000年推出了伤口床准备(WBP)框架,以强调将全人治疗作为最佳局部伤口护理的基础1。随着这一框架发展成为一个国际框架,就能明确并非所有伤口均能愈合。这些关于维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口的概念导致需对当地伤口护理原则进行修订,以及对WBP进行扩展。护士、医生和综合医疗保健人员携手合作,优化患者护理效果和医疗保健系统利用率,这种综合协调护理对于进一步开发WBP至关重要。

本文重点介绍如何应用WBP框架来管理足部相关伤口,尤其是对于患有糖尿病、麻风相关神经性脚部溃疡以及包括神经病和血管疾病在内的其他并发症的患者。以下几个参数对PWD十分重要:血糖控制不佳、血压变化、高胆固醇、足底压力再分布不足、感染和缺乏运动。吸烟对挽救PWD的肢体和生命也特别有害。

本文的重点在于资源有限环境的一系列定义,包括资源可用性较低;缺乏资助或资助有限;偏远、隔离或农村环境;以及土著人口。这些术语均与医疗保健机构相关,这些机构在获取用品、设备、专家以及高级伤口护理能力和技能方面可能会遇到困难。低资源环境可能存在于世界任何地方,并不局限于低收入国家或发展中国家。

作为这项工作的基础,Delphi过程促进了当前形式WBP框架的扩展和开发。来自15个国家的41位作者参加了Delphi过程,该过程分为两轮,采用李克特四级量表(1级,完全同意;2级,同意;3级,不同意;4级,完全不同意)。第一轮共有29项声明。虽然所有声明均超过了所期望的80%的共识水平,但主要作者小组仍考虑了299条意见。在进行Delphi过程第二轮讨论之前,我们聘请了一位专业编辑来提高声明的可理解性和语法准确性,共构建了32项声明。所有声明均达到了超过88%的共识水平。

在第二轮中,有14项声明达成了100%的共识。其中一项声明非常突出,Delphi小组的所有成员均将其评为“完全同意”:10C。建立覆盖患者和所有跨专业伤口护理团队成员的及时有效的沟通渠道,以改善医疗保健系统的伤口治疗效果。与此同时,每一位国际伤口专家均以小组为单位编写手稿内容。有关共识声明,请参阅补充表1(http://links.lww.com/NSW/A176)。

该共识旨在制定一个以科学为基础的最低护理标准,以优化可用资源。在资源有限的环境中处理伤口的10个关键步骤和32项子声明请参阅表1。这一共识过程更新了WBP框架,使其适用于任何环境,不论其资源自用性。此外,它还首次纳入了愈合轨迹和医疗保健系统变革的概念(图1)。

图1.伤口床准备2024.˝WoundPedia 2023

表1.在资源可用性有限的环境中为膝下伤口准备伤口床

本报告的其余部分将重点介绍10项共识声明,并讨论每项声明的原理。

声明1:病因治疗

1A. 评估动脉灌注是否足够,以确保伤口正常愈合

(可触及的足部脉搏和/或使用8 MHz多普勒进行的多相动脉足动脉声)

要测定下肢血流量,首先需找到可触及的足部脉搏。从足背动脉和/或胫后脉搏开始。如果可进行8 MHz手持式多普勒检查,则应确认多相血流模式(双相/三相)。当观察到单相或无多普勒声或无法触及足部脉搏时,请转诊至血管专科医生。动脉灌注不足的其他体征包括静息时下肢疼痛和肢体缺血性改变(肢端发冷伴抬高时发白的下垂部位红紫)。

糖尿病患者容易出现微血管问题(周围神经病、Charcot足部病变)和大血管并发症,包括外周动脉疾病(PAD)。这些情况会导致胼胝、脚部溃疡和混合组织损失。由于多达50%的易感人群同时患有糖尿病和PAD2,及时确认PAD至关重要(通过体格检查和血管试验),该疾病是导致溃疡愈合不良和截肢的主要风险因素。检测到该疾病后,必须立即进行血管重建(血管成形术或血管搭桥术),以恢复足部正常的动脉血流。其他评估可包括毛细血管再充盈时间、Buerger肢体发白试验(抬高时皮肤苍白,下垂时皮肤红紫)和行走时的跛行。

血管检查。在动脉功能不全的情况下,由于营养和氧气供应不足,肢体触感通常较为冰凉(表2)。重度病例可能会出现组织坏死,表现为溃疡、趾蹼浸渍(通常伴有继发性感染)、龟裂或坏疽。其他重度病例指标包括抬腿时皮肤苍白、运动引发的跛行(静息后缓解)、下垂部位发绀或红紫以及肌肉萎缩。值得注意的是,下肢水肿大多指示静脉问题,而非动脉问题。动脉溃疡一般呈穿凿样,基底较深,通常含有肌腱,而静脉溃疡的边界形态不规则,基底肉芽组织较浅3。

表2.组织愈合所需的血管供应

踝臂压力指数(ABPI)检查。ABPI使用8 MHz多普勒测量踝关节收缩压除以肱动脉收缩压的比值。该程序包括使用血压袖带,并在袖带充气后动脉声再次出现时记录收缩压。不过,水肿、炎症和动脉钙化等因素会影响其准确性。如果无法负担/无法进行8 MHz多普勒,在出现足部脉搏消失的情况下,应优先考虑尽早转诊至三级评估中心。在某些医疗保健机构中,在开始进行任何下肢干预之前,仍需要进行ABPI作为重要的定量评估。

手持式声学多普勒(AHHD)检查。如果医疗服务提供者选择更简单、更快捷的检测方法(不受钙化影响,无需挤压疼痛的小腿,也无需斜卧20分钟),那么在某些情况下,可以很容易地将AHHD添加为附加参数。在大脚趾截肢的情况下,AHHD评估也能提供准确的结果,并能以MP3或MP4文件格式进行记录和传输,以便对信号解释进行远程验证。

医疗保健人员应使用8 MHz多普勒探头将凝胶涂抹在脚背动脉、胫后动脉和腓动脉的适当足部脉搏部位,探头与皮肤成45度角。然后可以对获取的多普勒信号/波形进行分析(通过可听声或视觉轨迹):请访问https://journals.lww.com/aswcjournal/Pages/videogallery.aspx?videoId=20获取有关AHHD程序的全面教程。通过仔细调整探头位置来优化信号质量,以获得最响亮或最多相的信号。

对于单相或无波形的情况,需进行全面的血管评估,包括在血管实验室进行双功能节段性小腿动脉多普勒检查。多相波形通常表示不存在外周血管疾病4。在PWD中,需谨慎解释ABPI比值(由于动脉硬化或动脉钙化);AHHD多相检查结果是确认伤口愈合所需血液供应充足的首选参数。多相波形(双相、三相)表明AHHD值相当于ABPI正常值,即≥0.9。

虽然AHHD可有效排除动脉疾病,但其可能无法识别现有的节段性灌注缺陷Å\Å\缺血区或血管区域缺损5。因此,足部和下肢的体格检查对于确诊至关重要。医疗保健专业人员可以记录AHHD信号,并将其传输给专家,以便进行同步或异步远程评估。同步评估可使患者实时参与并迅速做出决策。

慢性静脉功能不全。PWD和脚部溃疡患者可能同时患有慢性静脉功能不全。其主要影响下肢,阻碍脱氧血液返回心肺。该疾病通常由静脉瓣膜功能障碍引起,而妊娠或体重升高等因素均可能诱发静脉瓣膜功能障碍。症状通常包括静脉曲张、水肿、血铁黄素导致的皮肤变色、脂肪皮肤硬化症和静脉溃疡6。这些溃疡大小不一(从小尺寸向圆周扩散),在静脉汇集区域迅速形成,通常位于下肢内侧。

加压疗法的治疗静脉溃疡的基石。其可以通过増强小腿肌肉泵的蠕动作用来补偿瓣膜功能障碍。其他措施包括抬高腿部和步行。如果溃疡由浅静脉引起,可以考虑进行静脉消融术。未经治疗的静脉水肿会延迟脚部溃疡愈合7。

对于PAD的医疗优化,关键策略包括最佳血压控制、开始胆固醇药物治疗,通常还包括开始他汀类药物治疗。最近的研究还建议对PAD并发冠状动脉疾病或颈动脉疾病的患者采用低剂量阿司匹林(每日91-100 mg PO)和低剂量利伐沙班

(2.5 mg PO BID)联合治疗8。其他可调整因素包括戒烟和步行或运动计划。适当的足底压力再分布或减轻压力对于脚部溃疡患者(尤其是PWD)至关重要。

1B. 确定所有基础病因

足部并发症是PWD极为关注的问题,也是医疗保健系统的一项重大疾病负担。助记符AIM(评估、识别、管理)是一种整体方法,其重点是治疗或减轻糖尿病足问题(尤其是神经病)的基础病因。采用重点评估方法作为基线护理标准(VIPS:血管、感染、压力、手术清创),对于预防重度并发症(包括足部溃疡、下肢截肢以及早期/可预防死亡发生率的増加)至关重要。在资源匮乏的环境中,与足部相关的一些关键因素包括:接受正式治疗的时间较晚、诊断延迟9、赤足行走、伤口被忽视以及缺乏预防性足部护理。在埃塞俄比亚进行的一项基于医院的观察性分析确定了导致糖尿病足并发症的几个因素10;这些因素包括湿度过高、足部变形、神经病、未识别的活动性溃疡、鞋袜不足或不合脚、足部卫生状态较差(如足部和趾甲真菌)以及缺乏足部护理意识。一项关于麻风患者足底溃疡的系统性综述(n=7项研究)确定了以下溃疡发生的风险因素:在感觉测试中无法感知到10 g单丝、重度足部变形或足旋前过度、教育程度较低以及无业11。在任何资源匮乏的环境中应对这些挑战,均需采取多管齐下的方法,其中可能包括患者和医疗保健专业人员教育、早期检测、提供护理、鞋类项目和社区参与。

定期和全面的足部评估包括检测神经病(保护性感觉丧失)、血管问题(下肢血液循环不良或缺失)、感染迹象、高压区域(胼胝形成)和摩擦(水泡,通常伴有出血成分),以便及时采取干预措施。这种简化的60秒钟筛查工具可能是根据患者的风险水平进行快速评估、分层和随访的重要手段,而且成本较低12。有溃疡病史、截肢史、外周血管手术史或Charcot神经性关节病史的患者发生皮肤破溃的风险最高,应给予更多关注,防止溃疡和进一步的并发症。

NERDS(浅表伤口感染:不愈合、渗出液、红色碎片状肉芽组织、碎片、气味)或STONEES(深部和周围伤口感染:面积増大、温度升高3ÅãF、骨膜[探针到骨头]、新的破溃区域、红斑>2、渗出液、气味)标准以及使用非接触式红外测温仪均对检测感染有所帮助13。与对侧肢体相比,温度升高3ÅãF可能预示着炎症和足部溃疡风险较高13。1.67ÅãC的比较变化在临床上难以测量。在小腿或脚部溃疡患者中,如果同时符合两个或更多STONEES标准,那么同样的检查结果意味着深部和周围感染的可能性要高出八倍13。

未出现溃疡但表现出热肿足的神经病患者可能患有急性Charcot神经性关节病。在这些病例中,红外测温仪是一种极具价值的评估工具:急性Charcot足的温度可能比对侧足的镜像温度高8-15ÅãF。此类患者需进行全面的病史、体格检查和放射影像检查,以便及早检测到相关症状。进一步的措施包括使用全接触石膏进行稳定,以及使用轮椅完全减轻足底压力,以防止骨骼进一步恶化和下肢截肢(表3)。

表3.对足底糖尿病性/神经病变性足部伤口进行减压干预28

PWD中的胼胝形成与压力和剪切应力呈正相关。对于糖尿病神经病变患者而言,足部变形、关节活动受限、行走时重复受力以及鞋子不合适等各种因素均会増加胼胝形成的风险14。此外,胼胝的存在也会带来重大风险,因为重复性外伤可能会导致皮下出血,最终进展为溃疡。提供量身定制的压力再分布装置(软鞋垫、鞋匠干预调整鞋子、减少赤足行走),以防止胼胝后续进展为溃疡。

不同的病因可能导致PWD出现脚部溃疡,具体如下:周围神经病引起的神经性溃疡、与PAD相关的缺血性溃疡,或两者结合的神经缺血性足部并发症。根据病史、体格检查(5.07/10 g单丝测

试)、双侧肢体对称分布的感觉改变(袜套和手套式分布)以及烧灼感、刺痛、剧烈刺痛或针刺痛,可确定是否存在糖尿病神经病变。

1C. 对最重要的病因/并发症进行分类,以便立即进行治疗,并在当地可用的支持系统/资源范围内设计靶向干预措施

25%至34%的PWD会出现糖尿病足溃疡(DFU),这是最令人担忧的并发症之一,可能导致下肢截肢、重度残疾和预期寿命缩短15。糖尿病相关周围神经病和PAD可由多种因素导致,会使足部极易受到外伤性损伤。及时接受诊断和干预是有效管理和保护肢体的决定性因素。

以血红蛋白A1c(HbA1c)升高进行衡量的慢性高血糖症是感觉、运动和自主神经病变的主要风险因素。PAD和皮肤干燥均会増加足部感染和延迟愈合的可能性,从而导致不良结局。慢性肾脏疾病会増加患病风险16。最近关于持续血糖监测的研究报告称,较高的血糖水平变异性(达到目标范围水平的时间缩短)也可能导致长期并发症17。

多达50%的PWD会出现神经病,但目前尚无治愈方法。管理措施包括每天适当检查足部是否有外伤或感染迹象、足部护理和有效控制血糖18。除神经病外,PAD也同样会导致DFU;PAD大多无症状,可能长期未得到诊断和治疗。与未患糖尿病的人群相比,糖尿病患者的PAD患病率増加了两倍多19。一项对基于社区的PAD全球患病率和风险因素研究进行的系统性回顾显示,糖尿病位居首位,其次为吸烟20。

欧洲高血压学会建议医疗服务提供者和患者旨在将收缩压控制在130 mm Hg以下,舒张压控制在80 mm Hg以下。PWD的收缩压不应低于120 mm Hg,以防止重要器官和下肢的血流量减少21。虽然利尿剂、钙通道阻滞剂、血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂、血管紧张素受体阻滞剂和É¿阻滞剂均可使用,但血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂和血管紧张素受体阻滞剂可减少心血管事件的发生率22,23。最近,SGLT2抑制剂在改善血糖、肾脏保护和心血管结局方面显示出良好的效果24。此外,通过改变生活方式及早发现PAD可降低DFU的发生率17。

管理DFU十分复杂,需要采用跨专业团队方法,以识别健康状况的生物、社会、地理和文化决定因素。在丹麦,PWD按地区进行登记,并可前往设有跨专业伤口护理团队的专科诊所就诊。由于糖尿病护理的改善、定期足部检查、自我护理质量提高和及时治疗,下肢截肢率已显著下降25。在地理位置较为分散的不同人群中(如加拿大安大略省),截肢率存在显著差异,其中农村地区的截肢率最高,因为在这些地区,血管重建术和足部护理专家等及时预防服务不足或缺乏此类服务。

在加拿大,最易发生糖尿病足相关截肢的人群包括土著人、移民以及生活在农村和北部地区的人群26。土著糖尿病健康圈为安大略省当地的第一民族社区提供了一种具有文化敏感性的方法,提供有关糖尿病、健康和自我管理的教育和知识。其整体足部护理计划支持一系列服务,将社区成员与土著机构合作伙伴和当地医疗保健专业人员联系起来,经证明可降低DFU发生率并防止截肢27。

1D. 根据动脉灌注情况,优先针对足部伤口进行压力再分布,并为腿部/足部水肿选择适当的加压疗法

标准足底压力再分布装置为全接触石膏或以不可拆卸方式安装的可拆卸石膏助行器28。即使在可随时获得这些减压装置的医疗保健系统中,也只有不到10%的合格患者适合安装并坚持使用这些装置29。

减轻压力对脚部溃疡的愈合至关重要(表3)。目的是结合以患者为中心的问题、护理目标和最佳实践证据,为患者选择最佳装置。考虑创造性解决方案,重新利用当地材料,如在资源有限的环境中使用软毡垫进行减压。重要的一点是,需在患者和医疗保健专业人员之间制定早期监测计划,以监测和确保达到所需的减压效果。医疗保健专业人员需要对装置的有效性进行评价,并通过既定的随访不断进行必要的修改。在缺乏专科从业人员的地区,使医护人员具备基础减压能力可以填补这一需求空白。

声明2:以患者为中心的问题

2A. 使用疼痛量表评估疼痛,制定有针对性的伤害性疼痛和/或神经性疼痛管理计划

对疼痛的感知涉及物理或化学刺激。疼痛主要有两种类型:伤害性疼痛和神经性疼痛(表4)。在以患者为中心的问题中,伤口相关疼痛是一个重要组成部分,但医护人员往往对其关注过少。到20世纪90年代末期,随着一份聚焦于伤口疼痛的关键立场文件的发布,伤口疼痛成为医疗保健专业人员的关注重点30。该文件认可并关注慢性伤口疼痛带来的痛苦及其对患者健康相关生活质量的影响。随后,将伤口疼痛管理纳入了WBP框

架1,31。

表4.疼痛类型和反应30

疼痛在伤口患者的整体管理和最终成功愈合方面起着重要作用32。损伤相关疼痛信号在确保患者健康方面发挥着重要作用,因此必须通过适当的评估和管理加以确认。例如,疼痛或疼痛的任何变化均为伤口感染的关键预测因素,也是炎症的四大主要体征之一1。疼痛无法缓解往往与伤口闭合延迟相关。

评估。疼痛史对于伤口疼痛管理至关重要32。评估必须包括疼痛的性质、发作时间、持续时间、恶化和缓解因素。这将有助于确定疼痛的原因并指导管理。疼痛强度可通过有效的疼痛量表进行可靠测量。0-10分的口头数字评分表是测量疼痛数字强度的首选。大多数患者的疼痛程度为3分至4分(满分10分),即可正常工作33。

应定期重新评估持续疼痛患者的病情改善、恶化情况以及对药物治疗方案的依从性。使用疼痛日记来记录疼痛强度、用药情况、情绪和对治疗的反应可能是一种较好的管理策略。对于有交流障碍的个体,疼痛量表应包含图片,以便于识别。

管理。可将伤口疼痛的处理纳入WBP框架:治疗病因,解决局部伤口因素和以患者为中心的问题3。病因治疗应确定正确的诊断结果,并开始治疗伤口疼痛。以患者为中心的问题必须侧重于患者认为疼痛的主要原因和解决方案。患者预期的疼痛和痛苦与实际经历的疼痛一样会影响生活质量。

目前存在多种疼痛管理策略,但均非药物治疗(表5)。在选择管理策略时,需考虑全面的患者管理,包括WBP的各个方面。请记住:疼痛是患者的感知34。

表5.疼痛管理策略

在资源有限的情况下进行评估和管理。在资源有限的地区,评估仍然是可行的,因为它无需借助昂贵的工具。虽然初始成本与从业人员的教育和培训有关,但大多数疼痛量表均可免费获取31。在资源有限的环境中,采用非药物方法治疗疼痛可能会更加实际(表5)。其中一些治疗方案可能更容易被社会接受,或在文化方面已得到实践(如冥想、植物疗法),并且尤其适用于管理伤害性疼痛。实施此类策略可以为那些无法通过非药物手段控制的疼痛患者(如神经性疼痛)保留药物管理方案35。

2B. 确定可能影响愈合效果的日常生活活动

2C. 评估患者是否有可能影响伤口愈合的(有害)生活习惯(如吸烟、酗酒和使用其他药物)

2D. 使用纳入患者支持系统的可持续教育干预措施,为患者提供支持。在可能的情况下,使用患者的主要语言,并考虑他们的文化背景、宗教、可接受的行为、禁忌和信仰

在资源有限的环境中,医疗服务提供者必须在相应社区的文化、精神和宗教信仰的背景下,了解和解决以患者为中心的问题以及影响临床效果的障碍。

全球各地的土著人口在伤口愈合方面存在差异。这些差异往往源于历史和当前的社会经济、文化和医疗保健相关因素。此外,文化多样性和社会压力往往决定了某些卫生部门的正式资源分配过程。土著人口中伤口愈合的一些关键障碍包括历史创伤、社会经济差异、获得医疗保健的机会有限、文化障碍、慢性疾病、文化相关愈合实践、地理隔离以及医疗保健系统偏倚36。在许多文化背景下,会采用荣誉制度来管理患者、老年人和慢性疾病患者。如果有足够的资源来维护这些原则,就更容易坚持这些原则。

许多研究表明,重大疾病是一个家庭产生巨额债务的核心原因之一37,38。即使在政府开办的诊所,也可能会向家庭收取额外的敷料或药品费用。因此,患者和家属可能会采用当地/土著/传统治疗者提供的替代治疗方法(非对抗疗法药物)。虽然这些治疗者收取的费用通常较低,但他们可能不具备处理慢性伤口的必要技能或专业知识,从而导致伤口恶化。

因伤口长期存在而失去独立行动能力是影响就诊和定期随访的另一个主要因素。在资源有限的环境中,交通工具的可用性各不相同,步行可能是到达公共交通上车点的唯一方式。偏僻的农村环境往往受影响最大,需要长途跋涉才能到达正规医疗保健机构。

家庭环境的社会健康状况以及将有医疗保健需求的个体纳入其中的意愿,均会影响所提供的护理/自我护理的质量,以及患者在家庭环境中的安全。由于各国的社会结构和环境有所不同,家庭支持和社会支持也因文化而异。通常情况下,随着时间的推移,经济负担会加重;患者的独立性和日常生活活动(ADL)能力会有所下降;更换敷料变得更具挑战性;护理者会感到压力、疲劳和筋疲力尽39。转诊时间过晚以及患者最终接受正式护理时病情危重/处于终末状态,均为进一步导致伤口愈合效果不佳的额外加重社会和行为因素。

在家治疗伤口的患者需要特定的私人空间。在空间有限的情况下,伤口异味、持续疼痛和不同的生活习惯是患者和家属面临的主要压力源。仅仅是严重皮肤伤口就已经对患者自身的社会互动、人际关系、性能力和自信心带来了负面影响。这会导致进行性焦虑和抑郁,并可能会使人对所感知到的治疗获益产生悲观情绪。随后,患者的自我效能感降低,这往往与伤口进一步恶化有关,包括最终的下肢截肢40。

当需要改变生活方式时,真正的挑战才开始。这往往需要额外的资源或量身定制的教育来制定自我保健计划40,41。健康教育和生活方式调整干预措施必须具有明确的原理,这一点怎么强调都不为过。生活方式干预措施可能会成为经济、社会和后勤方面的挑战,首先是获取此类干预措施,然后是在任何受限的生活领域内维持。此外,这是确保将获得的任何经济帮助正确分配给出现伤口的家庭成员的重要步骤。

在资源有限的环境中,有必要采用生物心理社会学方法来管理患者的伤口护理。伤口护理团队除了管理伤口外,还必须解决影响患者的社会压力源/因素。每例患者均需要一个独一无二的、相互协商一致的、适合其限制因素(医疗、经济、家庭、社会和情感支持)的管理计划40。

声明3:愈合能力

3A. 可愈性伤口:确定是否有足够的血液供应来促进伤口愈合,以及是否有适当的治疗方法可用于解决基础病因

3B. 维持性伤口:如果有足够的血液供应促进伤口愈合,但患者无法坚持执行护理计划和/或医疗保健系统没有所需的资源,则调整做法

3C. 不可愈性伤口:如果血液供应不足和/或基础病因无法纠正,则确定其他伤口治疗方法

在确定伤口愈合分类的过程中,首先要对患者进行全面的病史和体格检查。确定伤口的基础病因非常重要。解决基础病因是制定可实现的管理计划的第一步。

在某些情况下,慢性伤口也可能会停止愈合,无法在规定时间内实现伤口边缘的推进;这些伤口被称为难愈性伤口。这些症状通常属于维持性症状,但经过额外评估,即对患者、病史、病因和治疗计划进行重新评价后,可能会愈合3,42。

需要确定以患者为中心的问题和期望,并将其与机构/临床医生资源可用性、技能和可用的即时干预方案进行比较和调整3,42。管理计划以指定的愈合分类为基础,而愈合分类可能会发生变化。

不可愈性伤口需要保护,防止组织损失、伤口深部和周围感染以及伤口潮湿环境造成的整体恶化。当务之急是降低湿度。维持性伤口也需要保护,防止组织进一步损失,主要是进行干伤口床管理和局部感染控制。在有可用资源且其他患者因素得到控制以实现全面优化之前,组织保护也可能是一项临时措施。

停止愈合的可愈性伤口(难愈性伤口)需要第二次治疗来实现边缘推进,重新评估和跨专业团队干预的紧迫性是优先级最高的事项3,42。

声明4:局部伤口护理:检查、测量和监测