Volume 44 Number 2

Atopic Dermatitis: clinical aspects and treatments

Ryan S Q Geng, R Gary Sibbald

Keywords eczema, risk factors, atopic dermatitis, anti-inflammatory therapies, biologics, lesions, phototherapy, trials

For referencing Geng RSQ, Sibbald RG. Atopic Dermatitis: clinical aspects and treatments. WCET® Journal 2024;44(2):29-36

DOI 10.33235/wcet.44.2.29-36

Abstract

Atopic Dermatitis is the most common eczematous inflammatory skin condition, presenting with lesions that typically appear as poorly demarcated erythematous and scaly papules and plaques. The lesions most commonly occur on flexural surfaces of the knees, elbows, and wrists and are associated with moderate to severe itching. This article focuses on the clinical presentation of atopic dermatitis and treatment options. Other related topics include epidemiology, pathogenesis, risk factors, triggers, and differential diagnoses.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or atopic eczema, is the most common eczematous inflammatory skin condition, with a lifetime prevalence of 15%.1 Although patients of all ages can be affected, onset peaks in infancy, with 90% of cases occurring before 5 years of age.2 Notably, the prevalence of AD has increased two- to threefold over the past 3 decades.3

The pathogenesis of AD is multifactorial and involves a complex interplay between the skin barrier, genetic factors, and environmental exposures. Skin barrier dysfunction can be characterised by increased transepidermal water loss, increased skin pH, or decreased levels of ceramides, humectants, and structural proteins. Other challenges to skin barrier function include aberrant filaggrin (FLG; a protein that binds keratin fibers in epidermis) expression or excess soap usage, which can also increase skin permeability.4 As mast cells and basophils become sensitised to environmental antigens, type I immunoglobulin E-mediated hypersensitivity reaction, cytokine release, and inflammation are triggered, often resulting in intense itching. Scratching of the lesions results in further damage to the skin barrier, referred to as the itch-scratch cycle. Chronically, this can lead to worsening inflammation and lichenification.5

With the physical discomfort and cosmetic appearance of AD lesions, patients can experience significant psychosocial challenges, including social distress, embarrassment, and activity limitation.6 Given the potential impact on quality of life and increasing incidence, this review will focus on the clinical features of AD and available treatment options.

Risk Factors

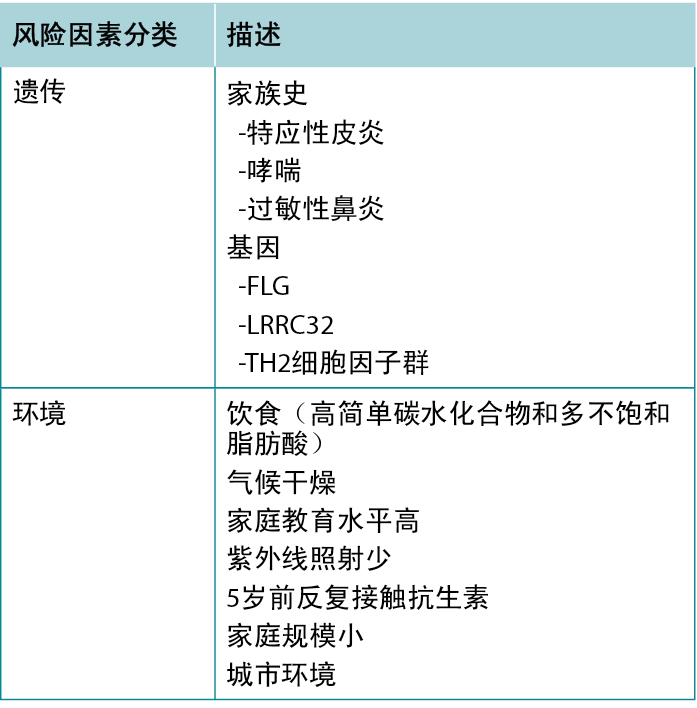

Atopic dermatitis is part of the atopic triad consisting of AD, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. There are several risk factors for developing AD, with the strongest predictor being a positive family history for any atopic disease, especially AD. The implicated genes include FLG, TH2 cytokine cluster, and LRRC32 (which encodes glycoprotein A repetitions predominant).7

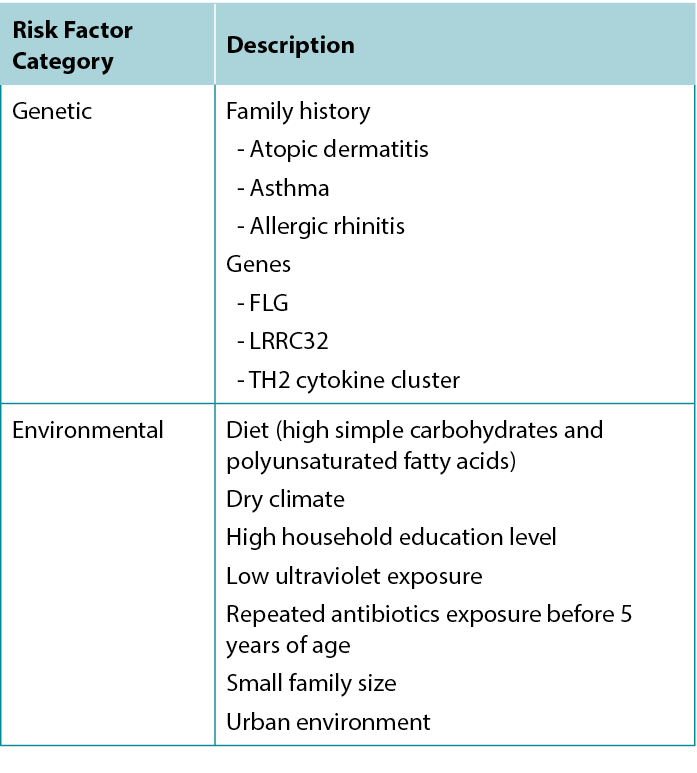

Environmental risk factors have also been identified: Living in an urban environment, dry climate, low UV light exposure, and a diet high in simple carbohydrates and polyunsaturated fatty acids are all associated with increased risk of AD.7 Table 1 summarises risk factors associated with AD.

Table 1 Factors associated with increased risk of developing Atopic Dermatitis.

Clinical classifications

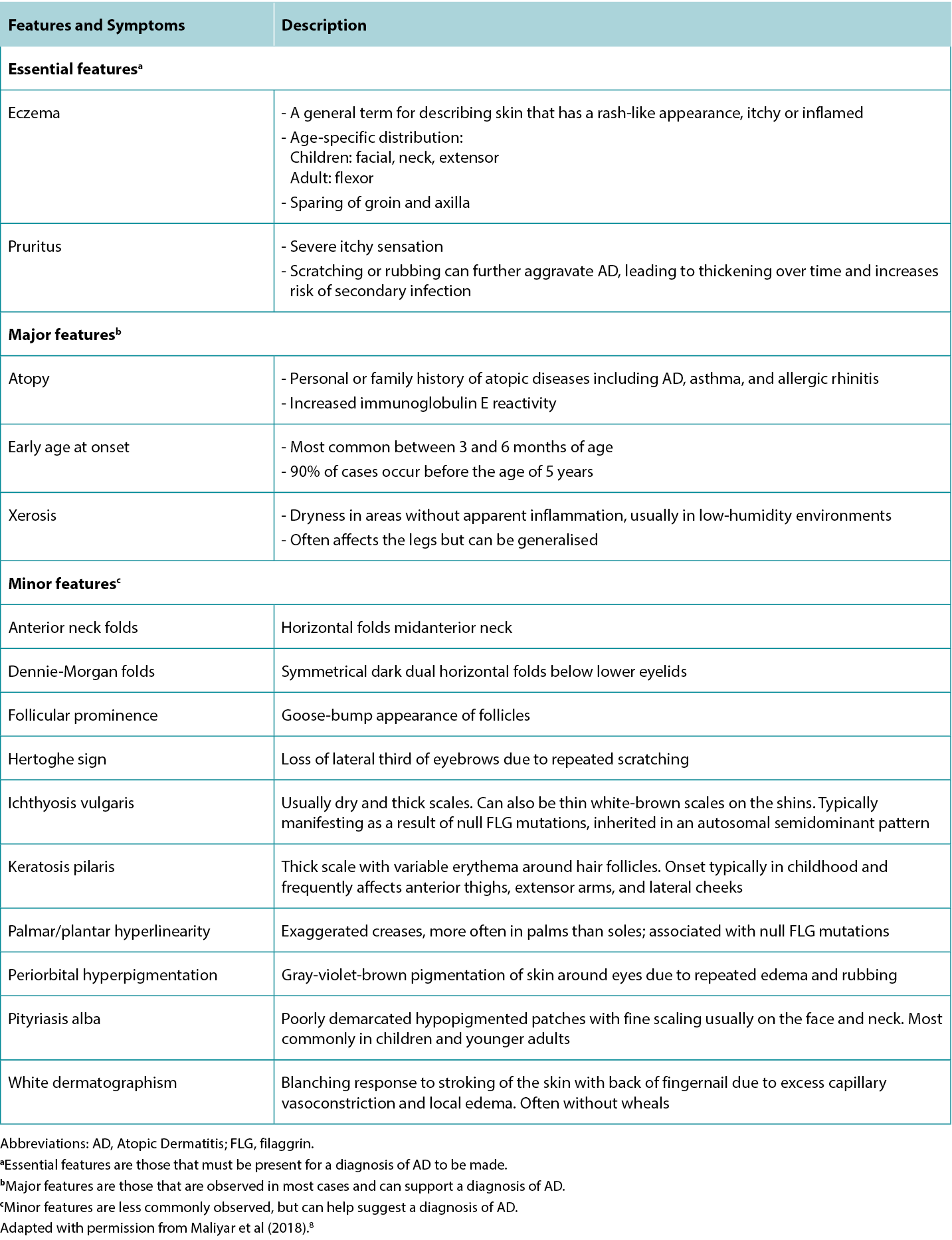

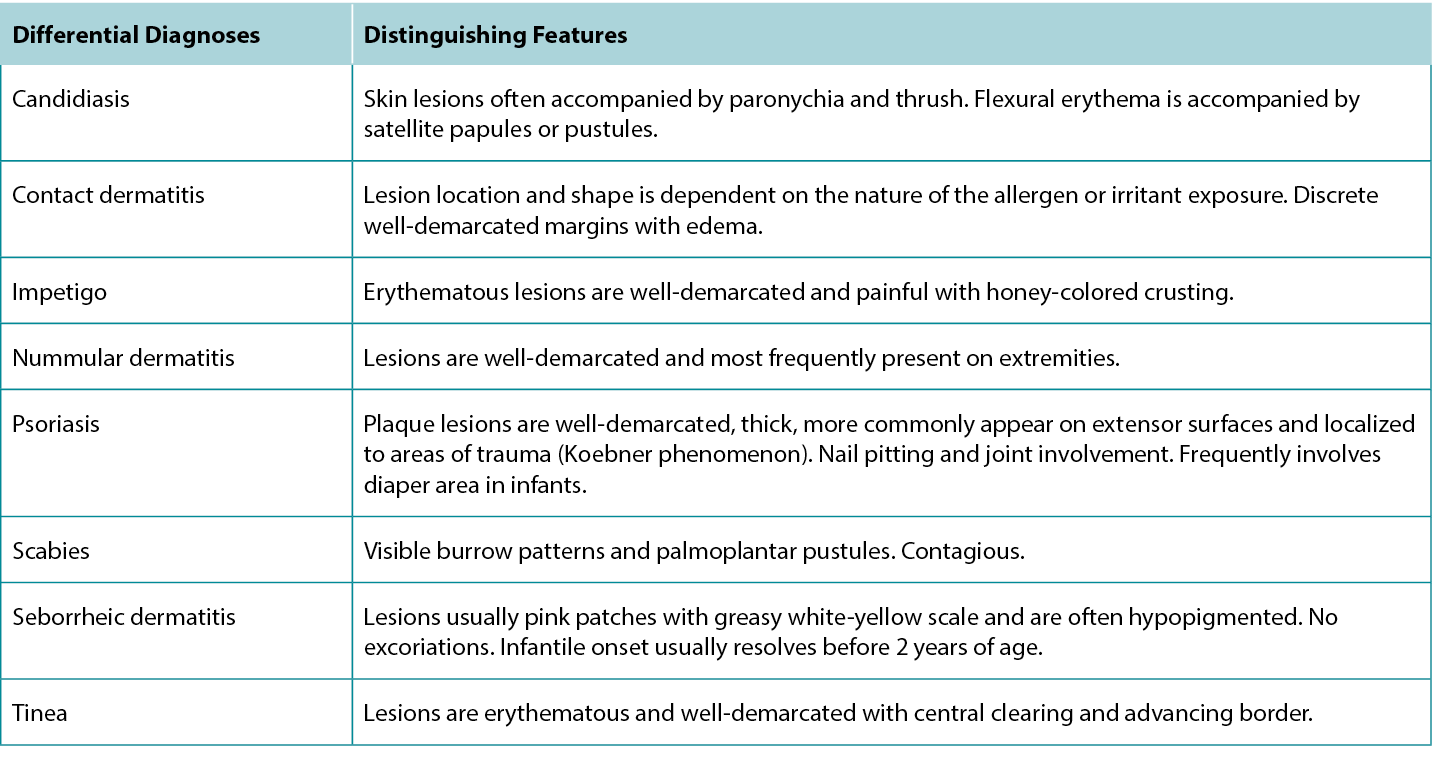

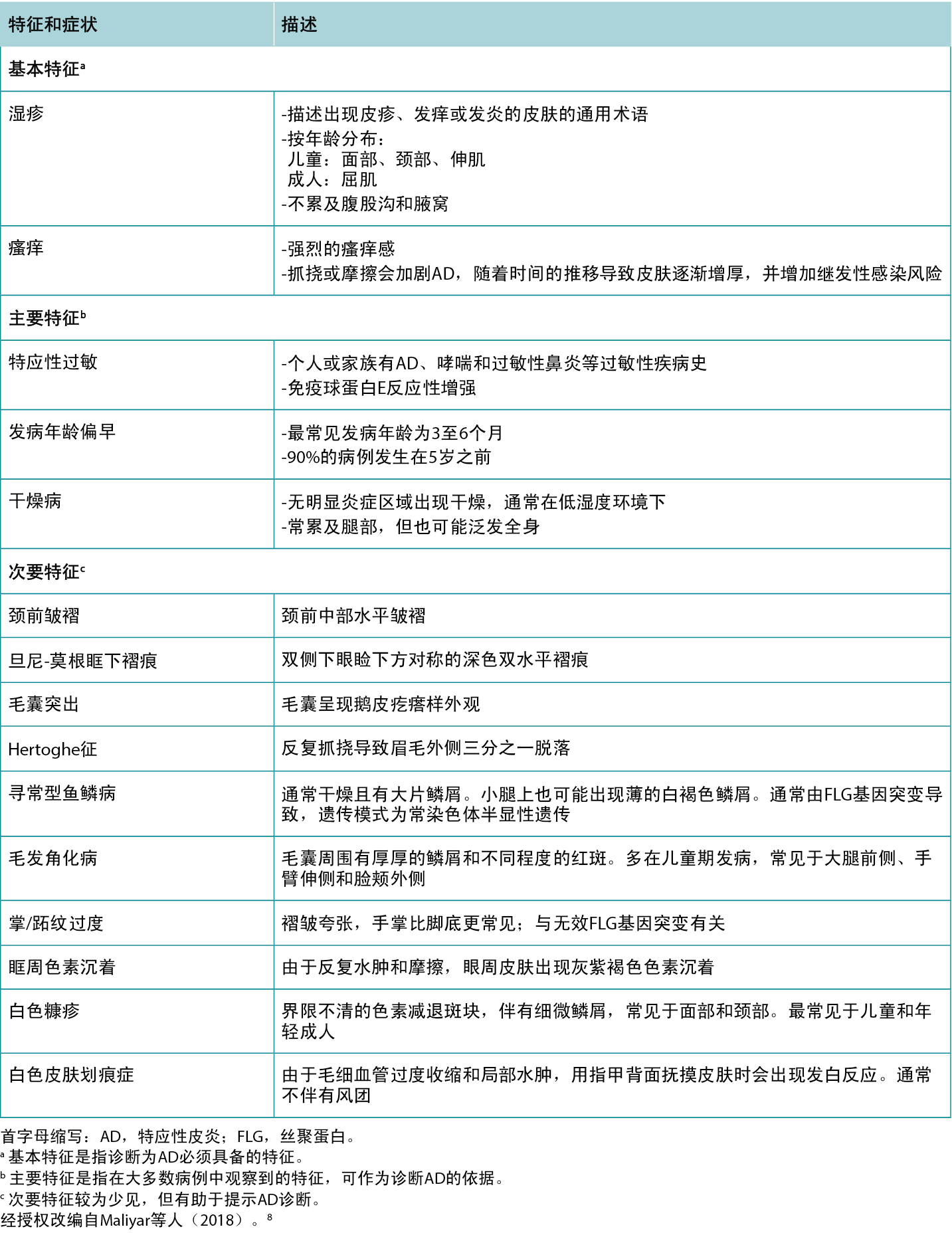

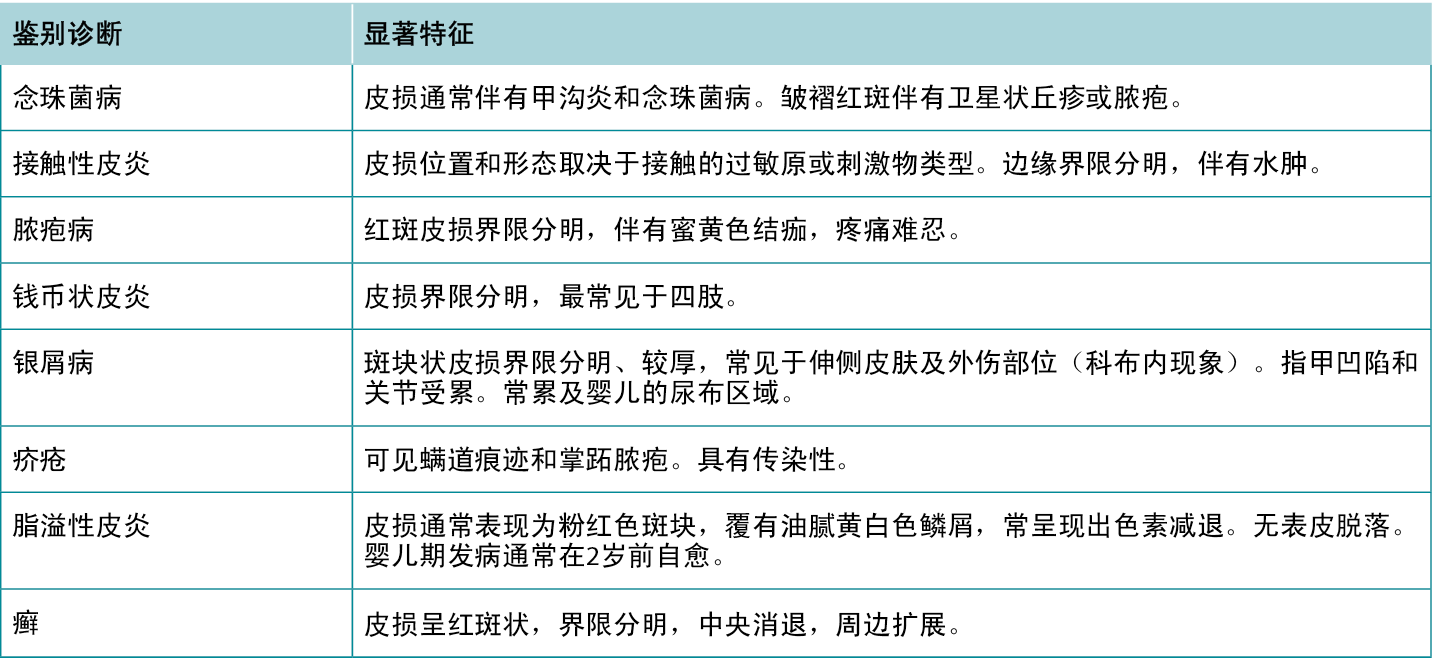

Although the clinical presentation of AD is heterogeneous with various features and symptoms, lesions are typically characterised as poorly demarcated, scaly, and erythematous papules that coalesce into plaques with severe itching that are most commonly found on flexural surfaces of knees, elbows, and wrists. The clinical features of AD are outlined in Table 2, with the essential, major, and minor features being indicated based on American Academy of Dermatology guidelines.2 Because of the wide variation in clinical presentation of AD, there is a broad differential, outlined in Table 3. Classification of AD is based on biomarker serology (IgE), acuity of presentation, and age at onset. Clinical presentations of AD are provided in Figure 1.

Table 2 Features and symptoms of AD.

Table 3 Differential diagnoses of Atopic Dermatitis and distinguishing features.

Figure 1 Clinical presentations of Atopic Dermatitis

A, Poorly demarcated erythematous plaques with fine scale on flexural aspect of the elbow. B, Well-demarcated erythematous plaques distributed on the dorsal aspect of the feet, ankle, and below the knee. C, Poorly demarcated erythematous patch on the flexural aspect of the wrist.

Classification by Serum IgE Levels

Extrinsic. The extrinsic subtype is characterised by elevated total IgE levels (>200 kU/L) in response to specific protein allergens, typically from the Dermatophagoides genus of mites, including Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farina. The main elevated cytokines include interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13, characteristic of a TH2 response. The extrinsic subtype arises from impaired skin barrier function, with 20% to 30% of patients having pathogenic FLG variants, and is much more common than the intrinsic subtype.9

Intrinsic. The intrinsic subtype is characterised by normal total IgE levels (<200 kU/L) and shows a sexual predilection toward women. The main elevated cytokine is interferon γ, characteristic of a TH1 response. Although the skin barrier is intact in the intrinsic subtype, metals and haptens can still penetrate the skin and trigger a response.9

Classification by Acuity of Presentation

Individual lesions of AD can be classified based on the acuity of presentation into acute, subacute, or chronic categories. An individual with AD may present with a combination of lesions in any of these different stages.

Acute. Acute lesions appear as poorly demarcated erythematous papulovesicular papules and plaque eruptions with blistering, weeping, and/or crusting. Widespread edema may also be present, with or without scales. Scratching can lead to erosions and pustules that are susceptible to secondary infection, primarily with Staphylococcus aureus.10

Subacute. Subacute lesions appear as poorly demarcated erythematous scaly plaques and papules.10

Chronic. Chronic lesions can involve lichenification (thickening of skin with increased visibility of skin markings) due to repeated scratching over time and scale.10

Classification by Age at Onset

Infantile (2 weeks to 2 years of age). Infantile-onset AD typically presents with lesions characterised as itchy papules and vesicles with associated serous exudate and/or crusting, most commonly affecting the head and neck. Lesions usually first appear as erythema and scaling on the cheeks, which then extend to the forehead, scalp, and neck. Extensor surfaces are also often involved as a result of trauma from crawling. Over time, scratching and rubbing can result in crusting and lichenification (thickening and increased skin surface markings).8

Childhood (2 years of age through puberty). In childhood-onset AD, facial involvement is less prominent, and instead the feet, ankles, wrists, and the flexural aspect of the knees and elbows are more commonly involved. Lesions are typically dry with lichenified plaques, papules, erosions (breakdown of epidermis with epidermal base), and/or crusts.8

Adult (postpuberty). Similar to childhood-onset AD, adult-onset AD primarily involves flexural regions, but also more commonly affects the face and neck. Lesions typically present as symmetrical, dry, scaly plaques, and papules. Excoriations and lichenification are commonly observed, whereas crusting and exudation are less frequent.8

Severity scoring

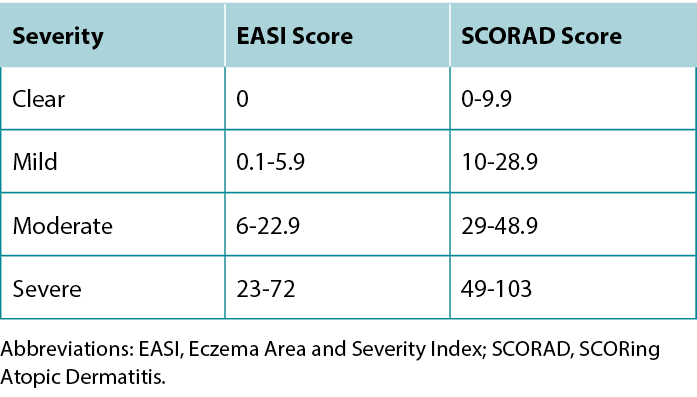

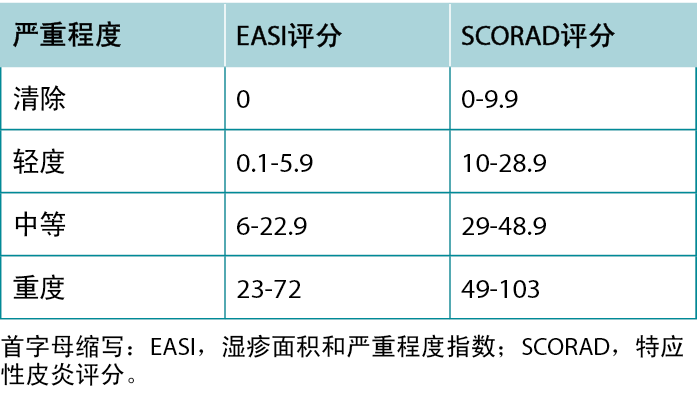

Once a diagnosis of AD has been achieved, describing the severity of the disease can guide treatment selection. The most commonly used severity scoring tools are the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) and SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD). Although both tools include the extent of erythema, swelling, excoriation, lichenification, and body area affected, the SCORAD also considers subjective patient measures.11 A summary of the severity grading strata for EASI and SCORAD is provided in Table 4.

Table 4 EASI and SCORAD severity grading strata.

AD treatments

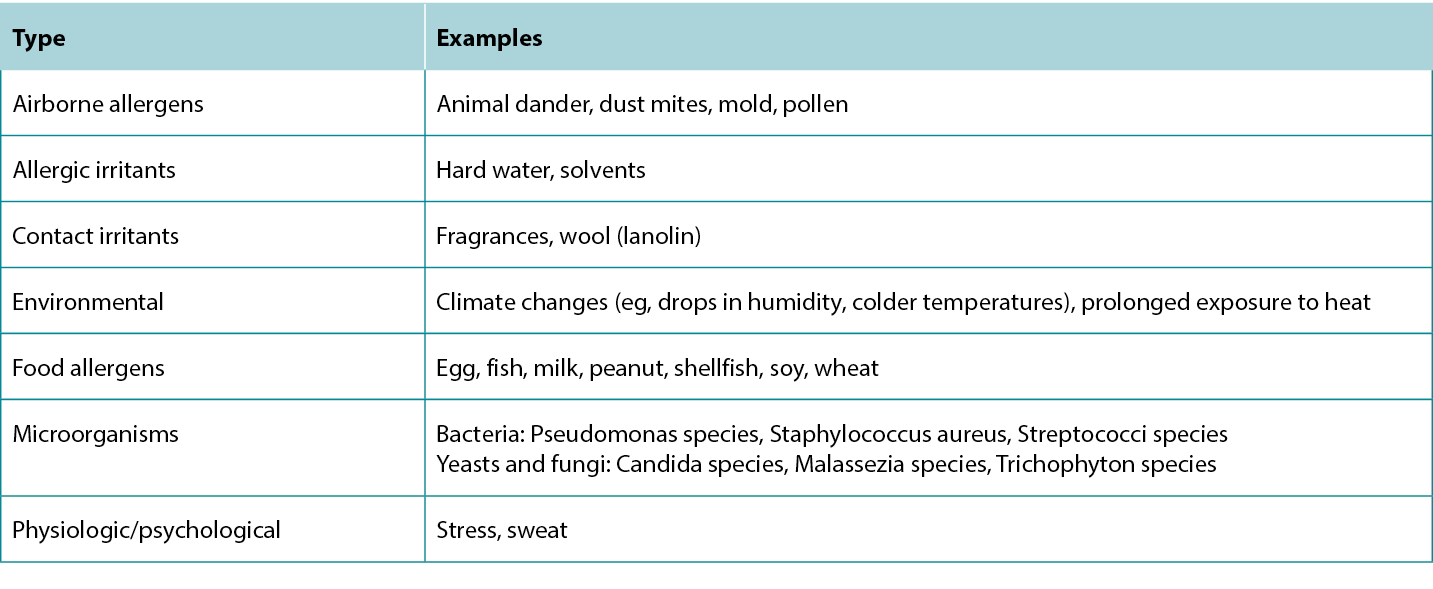

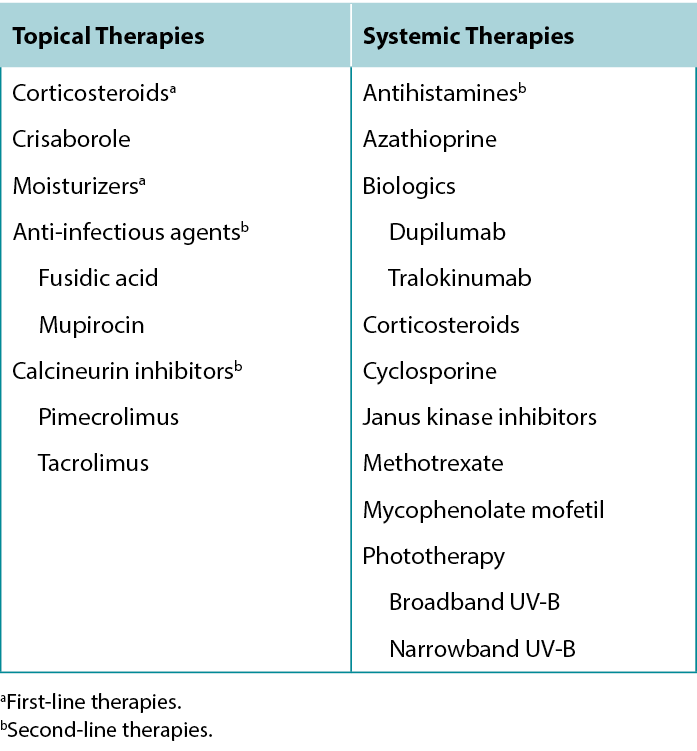

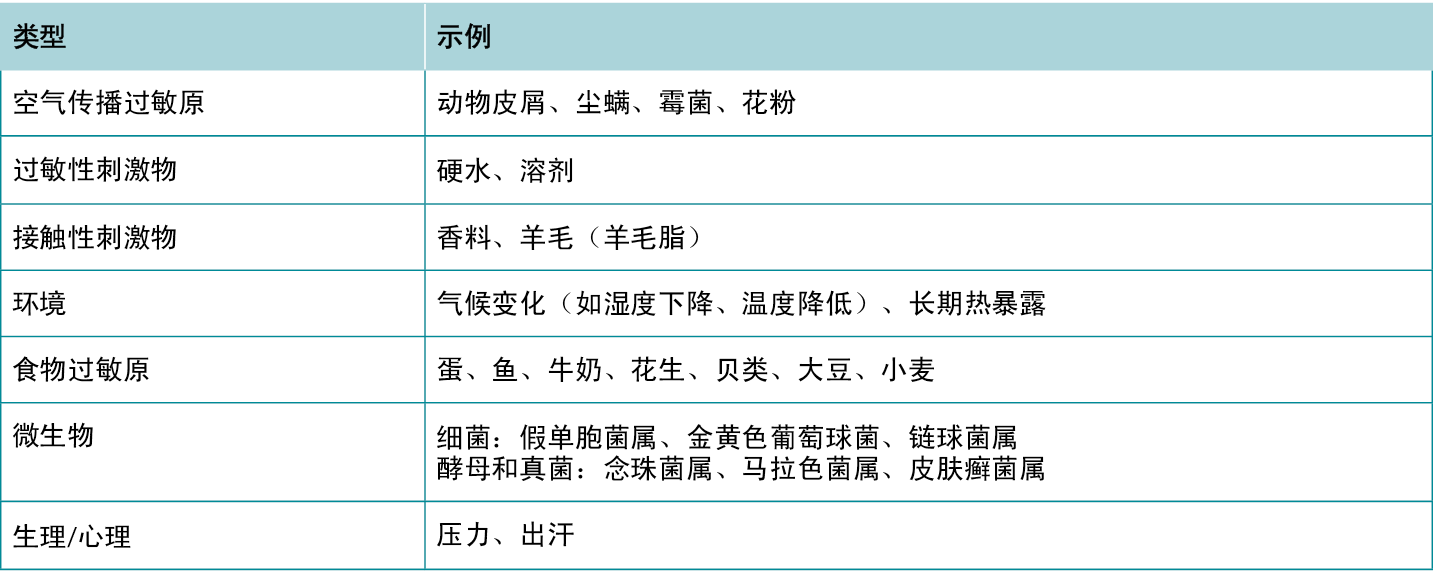

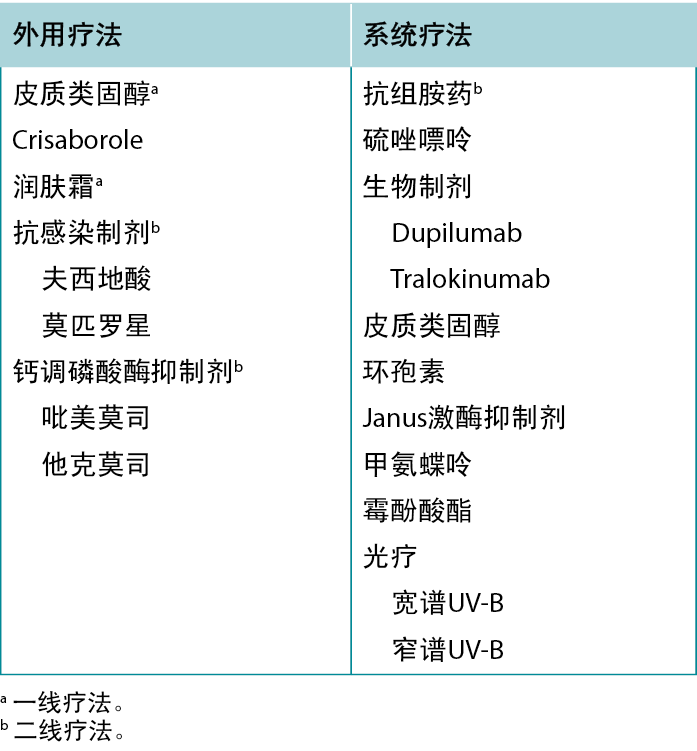

Several treatment options are available for treating AD lesions to provide symptomatic relief for patients and break the itch-scratch cycle to prevent disease progression and development of secondary infection. Counsel patients to regularly use moisturisers with emollients, humectants, and occlusive agents to improve the skin barrier, provide some itch relief, and prevent future flares.12 Patients with AD should avoid products with fragrances to minimise potential exposure to allergens. Discuss the importance of identifying and avoiding factors that trigger or exacerbate AD lesions.13 A list of common trigger factors is provided in Table 5, and a summary of treatment options for AD is provided in Table 6.

Table 5 Triggers and exacerbating factors of Atopic Dermatitis.

Table 6 Treatment options for Atopic Dermatitis.

Pharmaceutical Topical Treatments

Topical moisturisers. Regular usage of moisturisers is the cornerstone of AD therapy. Moisturisers can contain a combination of humectants, occlusives, and emollients that help protect the skin barrier. Humectants are hydrophilic substances that hold onto water, occlusives are hydrophobic substances that form a physical layer over the skin to trap water below, and emollients fill spaces between dead skin cells to soften the skin.

In addition to helping patients manage dryness and itchiness of active AD lesions, moisturisers can also prolong relapse. In a trial involving 44 patients with AD lesions cleared by betamethasone 0.1% cream, those who applied an urea-containing moisturising cream as the sole maintenance therapy relapsed after more than 180 days on average, compared with 30 days for patients who did not use any maintenance therapy.14

Topical corticosteroids. Corticosteroids have anti-inflammatory properties that are used for treating acute flares and itchiness. In a trial involving 40 patients, those treated with mometasone furoate 0.1% cream nightly for 4 weeks achieved a 77% reduction in SCORAD score compared with 17% for Vaseline control (P < .001).15 Corticosteroids are classified by their potency, and choice of corticosteroid should be guided by the patient’s age, region of the body affected, and severity of disease. Generally, low-potency corticosteroids are used for milder disease, younger patients, and in areas involving the face and folds (intertriginous regions).8 Long-term topical corticosteroid use is associated with further decreased skin-barrier function, skin atrophy, telangiectasia, and purpura and can induce or aggravate rosacea and perioral dermatitis. As such, corticosteroids are only recommended for short-term treatment of flares and symptom management. Intradermal corticosteroid injections can also be provided to provide fast-acting relief for acute flares.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus). Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are calcineurin inhibitors with anti-inflammatory properties and skin barrier-preserving properties used in treating AD. In one trial, 49 patients who applied tacrolimus 0.1% ointment twice daily for up to 22 days achieved 72% reduction in EASI score compared with 26% for vehicle (P < .001).16 Unlike corticosteroids, long-term tacrolimus or pimecrolimus use is not associated with skin atrophy; they can be used to reduce corticosteroid load or for maintenance.17 Patients may experience burning or stinging upon application, but cooling the product in the refrigerator prior to application can alleviate this sensation.

Topical phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (crisaborole). Crisaborole is a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor with efficacy in treating AD through downregulating the production of proinflammatory cytokines. In one study involving 400 patients, those treated with crisaborole 2% ointment twice daily for 4 weeks achieved a mean reduction of 60% in EASI score compared with 43% for vehicle (P = .0002).18 Crisaborole is generally well tolerated and is another steroid-sparing option for treating AD.

Topical anti-infectious agents. Anti-infectious agents are typically used as adjunctive therapies in cases where there is accompanying infection or if it is believed that a microbial factor (eg, S aureus) is aggravating the AD.

Fusidic acid and mupirocin are antibiotics used for targeting staphylococcal and streptococcal bacteria and can be effective in treating AD if S aureus colonisation is a contributing pathogenesis factor. In one trial involving 239 patients, those treated with fusidic acid 2% plus hydrocortisone 1% cream showed significant improvements in factors including erythema, itching, and scaling compared with patients treated with fusidic acid 2% cream or hydrocortisone 1% cream alone (P = .009).19

Soaking with bleach (sodium hypochlorite) is another option for reducing colonisation by S aureus. Patients can mix a quarter to a half cup of 6% bleach solution with a bathtub full of water and soak for 5 to 10 minutes.

Systemic Pharmaceutical Treatments

Corticosteroids. Although corticosteroids can be taken orally, this is often not recommended due to rebound flares on cessation and adverse effects associated with systemic corticosteroid use (eg, weight gain, diabetes, muscle loss, gastrointestinal bleeds, etc). However, systemic corticosteroids may have benefits for treating severe acute flares.20

Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine). Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor with anti-inflammatory properties that is useful in treating severe or recalcitrant forms of AD that have failed to respond to topic therapy. In one trial involving 46 patients, those who were treated with cyclosporine 5 mg/kg per day for 6 weeks achieved a mean 55% improvement in total body severity assessment score; in contrast, those with placebo worsened by 4% (P = .0002).21 Although cyclosporine offers rapid relief, its effects are not long-lasting, and maintenance therapy is required to prevent relapse.22 Renal impairment is a concern for initiating cyclosporine treatment and must be carefully monitored.

Purine analogs (azathioprine). Azathioprine is a corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressant used in several inflammatory skin diseases including AD. In a trial involving 37 patients, those treated with azathioprine 2.5 mg/kg per day for 12 weeks reported a mean 26% improvement on factors including erythema, dryness, and lichenification compared with 3% for placebo (P < .01).23 Although azathioprine has similar indications for usage in treating AD as cyclosporine, it is less preferred for acute flares because it does not act as fast. Hepatotoxicity is a concern for initiating azathioprine treatment.

Folic acid inhibitors (methotrexate). Methotrexate has immunosuppressive properties and can be used in low doses to suppress AD symptoms and flares in moderate to severe cases. In a study involving 40 patients, methotrexate was as effective as cyclosporine.24 Patients treated with methotrexate 7.5 mg/wk achieved a mean reduction of 26 SCORAD points compared with a 25-point reduction for those treated with cyclosporine 2.5 mg/kg per day (P = .93).24 Similar to azathioprine, hepatotoxicity should be considered.

Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitors (mycophenolate mofetil). Mycophenolate mofetil is another immunosuppressant with efficacy in treating AD. In a pilot study, 10 patients treated with 2 g/d for 4 weeks followed by 1 g/d for 4 weeks achieved a 55% decrease in SCORAD score (P < .01).25 Mycophenolate does not act as fast as corticosteroids or cyclosporine, but it can achieve satisfactory clinical control with fewer adverse effects and be used for maintenance therapy.

Biologics. Currently, the only approved biologics for treating AD are dupilumab and tralokinumab, both of which target the IL-13 signalling pathway. However, many other biologics are in development.

Dupilumab. Dupilumab is an IL-4/IL-13 inhibitor used in treating moderate to severe cases of AD that are recalcitrant to other topical and systemic therapies. In a trial with 671 patients, 38% of patients treated with dupilumab 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks and 37% of those treated weekly for 16 weeks achieved clear or almost clear on the Investigator’s Global Assessment scale compared with 10% for placebo (P < .001).26 Dupilumab greatly improves inflammation and itchiness without dose-limiting toxicity but is an expensive treatment.

Tralokinumab. Tralokinumab is an IL-13 inhibitor with similar indications for use as dupilumab. In a trial with 802 patients, 25% of those treated with tralokinumab 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks for 16 weeks achieved EASI 75 compared with 13% of patients in the control group (P < .001).27 Whereas both tralokinumab and dupilumab are effective, tralokinumab is associated with a lower risk of conjunctivitis.

Janus kinase inhibitors. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are small-molecule inhibitors that target the JAK signalling pathway, which is associated with several proinflammatory cytokines. In a trial involving 560 patients, 80% of those treated with upadacitinib 30 mg daily for 16 weeks achieved EASI 75 compared with 16% for placebo (P < .0001).28 In addition to offering high-target specificity like the biologics, JAK inhibitors can be applied topically (tofacitinib, ruxolitinib, delgocitinib) or taken orally (tofacitinib, baricitinib, abrocitinib, upadacitinib), offering a simpler route of administration.

Currently, three JAK inhibitors have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in AD. The first was ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor that was approved in 2021. The newer JAK1 selective inhibitors, upadacitinib and abrocitinib, were approved in 2022. Because of the novelty of these agents, their safety information may not be comprehensive, and clinicians should practice extra caution. Janus kinase inhibitors have black box warnings including increased risk of serious infection, malignancy, and lipid level changes. The US Food and Drug Administration added additional black box warnings for JAK inhibitors in 2022 because of an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, including heart attack, stroke, and blood clot formation. However, this finding was from a trial studying the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients over the age of 50 years with rheumatoid arthritis and at least one cardiovascular risk factor being treated with tofacitinib, with nearly 100% of patients taking methotrexate and more than 50% taking prednisone concurrently.29 Although clinicians should always pay close attention to black box warnings, it should be noted that the patient demographics in that study are not representative of AD patients, nor does the treatment regimen represent one that would be used in patients with AD.

Antihistamines. Antihistamines are used as an adjunctive treatment in AD to provide itch relief but do not treat the underlying disease itself. Even so, histamines should be considered in patients experiencing great discomfort due to the itchiness, because breaking the itch-scratch cycle is key to preventing disease progression and complications. This is especially relevant for patients who experience difficulty sleeping, in which case sedating antihistamines can provide relief.30

For relieving itch at night, use first-generation antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, etc), which provide a sedative effect to aid in sleep. For daytime, it is best to use second-generation antihistamines (eg, cetirizine, bilastine, etc), which are much less sedating because of their diminished ability to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is another option for patients whose AD cannot be controlled solely with topical therapy or who have extensive bodily involvement. Phototherapy modalities have shown efficacy in treating AD, including broadband UV-B and narrowband UV-B. Narrowband UV-B is considered first-line phototherapy, but its use can be limited by overheating and sweating, which can flare AD.31

Conclusions

Atopic dermatitis is the most common eczematic inflammatory skin condition, and it may reduce patients’ quality of life because of physical discomfort (itching, sleep disturbances) and adverse cosmetic effects. Management of AD often involves a combination of targeting the underlying disease and symptom management to break the itch-scratch cycle to prevent further exacerbation and promote disease remission. This can be achieved through the regular use of moisturisers and avoidance of triggers combined with either topical or systemic therapies.

Practice pearls

- Atopic dermatitis can be classified according to serum IgE levels, age at onset, and time of presentation.

- Atopic dermatitis lesions typically appear as poorly demarcated, scaly, and erythematous plaques associated with severe itching, most commonly found on flexural surfaces of knees, elbows, wrists, and sides of fingers.

- Use of moisturisers with emollient, humectant, or occlusive agents and avoidance of triggers are key to treatment.

- Symptomatic treatment to relieve physical discomfort and break the itch-scratch cycle can improve quality of life and prevent further exacerbation.

- Therapies with anti-inflammatory properties are the cornerstone of ad treatment.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

特应性皮炎:临床表现和治疗方法

Ryan S Q Geng, R Gary Sibbald

DOI: 10.33235/wcet.44.2.29-36

摘要

特应性皮炎是最常见的湿疹性炎症皮肤病,通常表现为界限不清的红斑、鳞屑状丘疹和斑块。此类皮损常见于膝部、肘部和腕部的屈曲表面,并伴有中度至重度瘙痒。本文重点介绍特应性皮炎的临床表现和治疗方案。其他相关主题涵盖流行病学、发病机制、风险因素、诱因和鉴别诊断。

引言

特应性皮炎(AD),又称为特应性湿疹,是最常见的湿疹性炎症性皮肤病,终生患病率约为15%。1尽管各年龄段的人都可能患病,但发病高峰在婴儿期,90%的病例发生在5岁之前。2值得注意的是,过去30年间AD的患病率已増长了两到三倍。3

AD的发病机制复杂多样,涉及皮肤屏障功能、遗传因素及环境暴露之间复杂的相互作用。皮肤屏障功能障碍可表现为经表皮失水増加、皮肤pH值升高或神经酰胺、吸湿剂和结构蛋白水平降低。其他对皮肤屏障功能构成挑战的因素包括丝聚蛋白(FLG;种在表皮中结合角蛋白纤维的蛋白质)表达异常或过度使用肥皂,这些都可増加皮肤渗透性。4当肥大细胞和嗜碱性粒细胞对环境抗原过敏时,就会触发I型免疫球蛋白E介导的超敏反应、细胞因子释放和炎症,通常伴随剧烈的瘙痒感。抓挠皮损会导致皮肤屏障进一步受损,这就是所谓的“瘙痒-抓挠”循环。长期如此,会导致炎症和苔藓样变。5

鉴于AD皮损带来的身体不适和外观影响,患者可能会面临显著的心理社会挑战,包括社交困扰、尴尬和活动受限。6鉴于AD对生活质量的潜在影响和发病率的不断上升,本综述将重点讨论AD的临床特征和现有的治疗方案。

风险因素

特应性皮炎是由AD、哮喘和过敏性鼻炎组成的特应性三联征的一部分。患注意力缺失症的风险因素有多种,其中最主要的预测因素是家族中有人患过特应性疾病,尤其是AD。受影响的基因包括FLG、TH2细胞因子群和LRRC32(主要编码糖蛋白A重复序

列)。7

环境风险因素也已被识别:居住在城市环境中、气候干燥、紫外线照射少以及饮食中简单碳水化合物和多不饱和脂肪酸含量高,这些都与AD风险増加相关。7表1总结了与AD相关的风险因素。

表1 与特应性皮炎患病风险増加相关的因素。

临床分类

尽管AD的临床表现各异,症状多种多样,但其典型皮损特征为界限不清、鳞屑状、红斑性丘疹,可凝聚成斑块,伴有重度瘙痒,最常见于膝部、肘部和腕部的屈曲表面。表2列出了AD的临床特征,根据美国皮肤病学会指南指出了基本特征、主要特征和次要特征。2由于AD临床表现的广泛多样性,其鉴别诊断范围广泛,详情见表3。AD的分类基于血清生物标志物(IgE)水平、病情急缓程度以及发病年龄。AD的临床表现见图1。

表2 AD的特征和症状。

表3 特应性皮炎的鉴别诊断和特征。

图1 特应性皮炎的临床表现

A:肘部屈侧有界限不清的红斑和细微鳞屑。B:脚背、脚踝和膝盖下方分布着界限分明的红斑。C:腕部屈侧有界限不清的红斑。

按血清IgE水平分类

外源型。外源型亚型的特征是总IgE水平升高

(>200 kU/L),以响应特定的蛋白质过敏原,通常来自尘螨属,包括屋尘螨和粉尘螨。主要升高的细胞因子包括白细胞介素4(IL-4)、IL-5和IL-13,以TH2反应为特征。外源型亚型源于皮肤屏障功能受损,约20%至30%的患者携带致病性FLG变体,比内源型亚型更为常见。9

内源型。内源型亚型的特征是总IgE水平正常

(<200 kU/L),并且女性更易患此亚型。主要升高的细胞因子是干扰素É¡,以TH1反应为特征。尽管内源型亚型的皮肤屏障相对完整,但金属和半抗原仍能穿透皮肤并引发反应。9

按病情急缓程度分类

AD的单个皮损可根据病情的急缓程度分为急性、亚急性和慢性类别。AD患者可能在这些不同阶段呈现各种皮损的组合特征。

急性。急性皮损表现为界限不清的红斑性丘疹、水疱性丘疹和斑块疹,伴有水疱、渗液和/或结痂。也可能出现广泛的水肿,伴有或不伴有鳞屑。抓挠可导致糜烂和脓疱,容易出现继发性感染,主要是金黄色葡萄球菌感染。10

亚急性。亚急性皮损表现为界限不清的红斑、鳞屑状丘疹和斑块。10

慢性。慢性皮损可因长期反复抓挠和鳞屑而导致苔藓样变(皮肤増厚,皮肤印记更加明显)。10

按发病年龄分类

婴儿期(2周至2岁)。婴儿期发病的AD通常表现为瘙痒性丘疹和嚢泡,伴有浆液性渗出和/或结痂,最常见于头部和颈部。皮损通常最初表现为面颊上的红斑和脱屑,随后扩展至前额、头皮和颈部。由于蚁行导致的外伤,伸侧表面也常受累。随着时间推移,抓挠和摩擦可导致结痂和苔藓样变(皮肤表面増厚和斑纹増多)。8

儿童期(2岁至青春期)。儿童期发病的AD,面部受累并不明显,相反,足部、脚踝、腕部以及膝部和肘部的屈侧更常受累。皮损通常是干燥的苔癣化斑块、丘疹、糜烂(表皮与表皮基底破裂)和/或结

痂。8

成人(青春期后)。与儿童期发病的AD相似,成人期发病的AD主要是屈侧区域受累,但面部和颈部更常受累。皮损通常表现为对称性、干燥、鳞状斑块和丘疹。常见抓痕和苔藓样变,而结痂和渗出较少

见。8

严重程度评分

一旦确诊为AD,描述疾病的严重程度可以为选择治疗方案提供指导。最常用的严重程度评分工具是湿疹面积和严重程度指数评分(EASI)和特应性皮炎评分(SCORAD)。尽管这两种工具都包括红斑、肿胀、表皮脱落、苔藓样变和受累身体部位的程度,但SCORAD还考虑了患者的主观测量。11表4总结了EASI和SCORAD的严重程度分级。

表4 EASI和SCORAD严重程度分级。

AD治疗

针对AD皮损有多种治疗方法,旨在缓解患者的症状,打破“瘙痒-抓挠”循环,防止疾病进展及继发性感染的发生。建议患者定期使用含有润肤剂、吸湿剂和封包剂的保湿霜,以改善皮肤屏障、缓解瘙痒并预防未来的发作。12AD患者应避免使用含香料的产品,以减少潜在的过敏原接触。讨论识别和避免引发或加重AD皮损因素的重要性。13常见诱因列表见表5,AD治疗方案概览见表6。

表5 特应性皮炎的诱因和加重因素。

表6 特应性皮炎的治疗方案。

外用药物治疗

外用润肤霜。定期使用润肤霜是AD治疗的基石。润肤霜可包含吸湿剂、封包剂和润肤剂的组合,有助于保护皮肤屏障。吸湿剂是一种亲水性物质,能保持水分;封包剂是一种疏水性物质,能在皮肤上形成一层物理层,将水分阻隔在其下;润肤剂能填补死皮细胞之间的空隙,软化皮肤。

润肤霜除了能帮助患者控制活动性AD皮损的干燥和瘙痒,还能延长复发时间。在一项涉及44例患者使用0.1%倍他米松乳膏消除AD皮损的试验中,使用含有尿素的保湿霜作为唯一维持疗法的患者平均在超过180天后复发,相比之下,未采取任何维持治疗的患者平均在30天后复发。14

外用皮质类固醇。皮质类固醇具有抗炎特性,用于治疗急性发作和瘙痒。在一项涉及40例患者的试验中,连续4周每晚使用0.1%糠酸莫米松乳膏的患者的SCORAD评分降低了77%,而凡士林对照组仅降低了17%(P<0.001)。15皮质类固醇根据其效力进行分类,皮质类固醇的选择应根据患者的年龄、受影响身体部位和疾病的严重程度而定。一般而言,弱效皮质类固醇适用于病情较轻、较年轻的患者,以及面部和皱褶部位(间擦区域)。8 长期外用皮质类固醇激素会导致皮肤屏障功能进一步降低、皮肤萎缩、毛细血管扩张和紫癜,并可能诱发或加重酒渣鼻和口周皮炎。因此,只建议将皮质类固醇用于复发的短期治疗和症状控制。皮内注射皮质类固醇也可快速缓解急性发作。

外用钙调磷酸酶抑制剂(他克莫司和吡美莫司)。他克莫司和吡美莫司均属于钙调磷酸酶抑制剂,具有抗炎和保护皮肤屏障的特性,可用于治疗AD。在一项试验中,49例连续22天每天两次使用0.1%他克莫司软膏的患者的EASI评分降低了72%,而安慰剂组降低了26%(P<0.001)。16 与皮质类固醇不同,长期使用他克莫司或吡美莫司不会导致皮肤萎缩;它们可作为减少皮质类固醇用量或维持治疗的选

项。17 患者在使用时可能会感到灼热或刺痛,但在使用前将产品放入冰箱冷却可减轻这种感觉。

局部使用磷酸二酯酶-4抑制剂(crisaborole)。Crisaborole是一种磷酸二酯酶-4抑制剂,可通过下调促炎细胞因子的产生来有效治疗AD。在一项涉及400例患者的研究中,连续4周每天两次使用2% crisaborole软膏的患者的EASI评分平均降低了60%,相比之下,安慰剂组的EASI评分平均降低了43%(P=0.0002)。18Crisaborole通常耐受性良好,是另一种减少皮质类固醇使用的AD治疗选择。

外用抗感染制剂。在伴有感染或认为微生物因素(如金黄色葡萄球菌)加重AD的情况下,抗感染制剂通常用作辅助治疗。

夫西地酸和莫匹罗星是针对葡萄球菌和链球菌的抗生素,如果金黄色葡萄球菌定植是致病因素,则可有效治疗AD。在一项涉及239例患者的试验中,与仅使用2%夫西地酸乳膏或1%氢化可的松乳膏治疗的患者相比,使用2%夫西地酸加1%氢化可的松乳膏治疗的患者在红斑、瘙痒和脱屑等因素方面表现出显著改善(P=0.009)。19

用漂白剂(次氯酸钠)浸泡是减少金黄色葡萄球菌定植的另一种选择。患者可以将四分之一至半杯的6%漂白剂溶液加入满缸水中,浸泡5 min-10 min。

系统性药物治疗

皮质类固醇。虽然皮质类固醇可以口服,但通常不推荐使用,因为停药后会反弹,并且系统使用皮质类固醇会产生不良反应(如体重升高、糖尿病、肌肉减少、胃肠出血等)。不过,系统使用皮质类固醇可能对治疗严重急性发作有益。20

钙调磷酸酶抑制剂(环孢素)。环孢素是一种具有抗炎特性的钙调磷酸酶抑制剂,可用于治疗对局部疗法无效的严重或顽固型AD。在一项涉及46例患者的试验中,连续6周每天接受5 mg/kg环孢素治疗的患者的全身严重程度评估评分平均改善了55%;相比之下,安慰组恶化了4%(P=0.0002)。21尽管环孢霉素能迅速缓解症状,但其作用并不持久,需要进行维持治疗以防止复发。22 肾功能损害是开始环孢素治疗时需要关注的问题,必须对其进行仔细监测。

嘌呤类似物(硫唑嘌呤)。硫唑嘌呤是一种减少皮质类固醇使用的免疫抑制剂,可用于治疗包括AD在内的多种炎症性皮肤病。在一项涉及37名患者的试验中,连续12周每天接受2.5 mg/kg硫唑嘌呤治疗的患者报告红斑、干燥和苔藓样变等因素平均改善26%,而安慰剂组仅改善3%(P<0.01)。23虽然硫唑嘌呤在治疗AD方面的适应症与环孢素相似,但由于起效不如后者迅速,在急性发作时不太受青睐。开始硫唑嘌呤治疗时需要关注肝脏毒性问题。

叶酸抑制剂(甲氨蝶呤)。甲氨蝶呤具有免疫抑制作用,可低剂量用于抑制中度至重度病例的AD症状和发作。在一项涉及40例患者的研究中,证实了甲氨蝶呤与环孢素同样有效。24接受7.5 mg/wk甲氨蝶呤治疗的患者的SCORAD评分平均降低了26分,而接受2.5 mg/kg/天环孢素治疗的患者则降低了25分(P=0.93)。24与硫唑嘌呤类似,应考虑肝脏毒性。

肌苷单磷酸脱氢酶抑制剂(霉酚酸酯)。霉酚酸酯是另一种有效治疗AD的免疫抑制剂。在一项预实验研究中,10例患者先连续4周接受2 g/d的治疗,后又连续4周接受1 g/d的治疗,结果SCORAD评分下降了55%(P<0.01)。25虽然霉酚酸酯的作用不如皮质类固醇或环孢素迅速,但它可以达到令人满意的临床控制效果,不良反应较少,可用于维持治疗。

生物制剂。目前,唯一获批用于AD治疗的生物制剂是dupilumab和tralokinumab,这两种药物都以IL-13信号通路为靶点。不过,还有许多其他生物制剂正处于研发阶段。

Dupilumab。Dupilumab是一种IL-4/IL-13抑制剂,用于治疗对其他局部和全身治疗无效的中度至重度AD病例。在一项涉及671例患者的试验中,每2周皮下注射300 mg dupilumab的患者中,有38%在16周后达到了研究者整体评估量表的皮损清除或几乎清除标准,每周注射一次的患者中也有37%达到这一标准,而安慰剂组仅有10%达到这一标准(P<0.001)。26 Dupilumab极大改善了炎症和瘙痒,且无剂量限制性毒性,但治疗成本较高。

Tralokinumab。Tralokinumab是一种IL-13抑制剂,其适应症与dupilumab相似。在一项涉及802例患者的试验中,连续16周每2周接受一次300 mg tralokinumab皮下注射治疗的患者中有25%达到EASI 75,而对照组中仅有13%的患者达到这一标准(P<0.001)。27虽然tralokinumab和dupilumab都有效,但tralokinumab发生结膜炎的风险较低。

Janus激酶抑制剂。Janus激酶(JAK)抑制剂是针对与多种促炎细胞因子相关的JAK信号通路的小分子抑制剂。在一项涉及560例患者的试验中,连续16周每天接受30 mg upadacitinib治疗的患者中有80%达到EASI 75,而接受安慰剂治疗的患者仅有16%达到这一标准(P<0.0001)。28 除了像生物制剂一样具有高度靶向特异性外,JAK抑制剂还可外用(tofacitinib、ruxolitinib、delgocitinib)或口服(tofacitinib、baricitinib、abrocitinib、upadacitinib),给药途径更为简便。

目前,美国食品和药物管理局已批准三种用于AD治疗的JAK抑制剂。第一种是2021年获批的JAK1/2抑制剂ruxolitinib。更新型的JAK1选择性抑制剂upadacitinib和abrocitinib已于2022年获得批准。由于这些制剂较为新颖,其安全性信息可能不够全面,临床医师在使用时应格外谨慎。Janus激酶抑制剂带有黒框警告,包括増加严重感染、恶性肿瘤和血脂水平变化的风险。鉴于使用JAK抑制剂治疗的患者中观察到心血管不良事件风险増加(包括心脏病发作、卒中和血栓形成),美国食品药品监督管理局2022年添加了额外的黒框警告。然而,这一发现源自一项研究,该研究调查了接受tofacitinib治疗的50岁以上、至少有一个心血管风险因素的类风湿关节炎患者发生重大心血管事件的发病率,其中近100%的患者同时接受tofacitinib治疗,超过50%的患者还同时接受了泼尼松治疗。29虽然临床医生应始终密切关注黒框警告,但应该注意的是,该研究中的患者人口统计信息并不代表AD患者,也不代表将用于AD患者的治疗方案。

抗组胺药。抗组胺药是AD的辅助治疗药物,可缓解瘙痒,但不能治疗潜在疾病本身。尽管如此,对于因瘙痒而感到极度不适的患者,也应考虑使用组胺类药物,因为打破“瘙痒-抓挠”循环是防止疾病进展和并发症的关键。这对于睡眠困难的患者尤其重要,在这种情况下,镇静抗组胺药可缓解症状。30

为了缓解夜间瘙痒,可选用第一代抗组胺药(如diphenhydramine、羟嗪等),它们具有镇静作用,有助于睡眠。白天则宜使用第二代抗组胺药(如西替利嗪、比拉斯汀等),这类药物由于难以穿透血脑屏障,因此镇静作用较弱。

光疗

对于仅靠外用治疗无法控制或皮损广泛累及全身的AD患者,光疗是另一种可行的治疗方案。宽谱UV-B和窄谱UV-B等光疗模式已被证实对AD具有治疗效果。窄谱UV-B被视为一线光疗选择,但其使用可能受限于过热和出汗,这些反应可能加剧AD病情。31

结论

特应性皮炎是最常见的湿疹性炎症皮肤病,由于身体不适(瘙痒、睡眠失调)和不良的外观影响,可能会降低患者的生活质量。AD的管理往往需要结合针对基础疾病和症状管理的策略,以打破“瘙痒-抓挠”循环,防止病情进一步恶化,促进疾病缓解。这可以通过定期使用润肤霜、避免诱因,结合外用或系统性疗法来实现。

实践要点

- 特应性皮炎可根据血清IgE水平、发病年龄和病程时间进行分类。

- 特应性皮炎的皮损通常表现为界限不清、鳞屑状和红斑性斑块,伴有剧烈瘙痒,最常见于膝部、肘部、腕部和手指两侧等屈曲表面。

- 使用含有润肤剂、吸湿剂或封包剂的润肤霜以及避免诱因是治疗的关键。

- 对症治疗可缓解身体不适,打破“瘙痒-抓挠”循环,从而提高生活质量,防止病情进一步恶化。

- 抗炎性质的治疗是AD治疗的基石。

利益冲突声明

作者声明无利益冲突。

资助

作者在本研究中未收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Ryan S Q Geng*

MSc

Temerty School of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

R Gary Sibbald

MD Med FRCPC (Med Derm) FAAD MAPWCA JM

Dalla Lana School of Public Health & Division of Dermatology,

Department of Medicine, University of Toronto

* Corresponding author

References

- Deckers IA, McLean S, Linssen S, Mommers M, van Schayck CP, Sheikh A. Investigating international time trends in the incidence and prevalence of atopic eczema 1990-2010: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. PLoS One 2012;7(7):e39803.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70(2):338-51.

- Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006;368(9537):733-43.

- O’Regan GM, Sandilands A, McLean WHI, Irvine AD. Filaggrin in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122(4):689-93.

- Perkin MR, Strachan DP, Williams HC, Kennedy CT, Golding J, Team AS. Natural history of atopic dermatitis and its relationship to serum total immunoglobulin E in a population-based birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2004;15(3):221-9.

- Gochnauer H, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Cardwell L, Anolik RB. The psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017;1027:57-69.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018;4(1):1.

- Maliyar K, Sibbald C, Pope E, Sibbald GR. Diagnosis and management of atopic dermatitis: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care 2018;31(12):538-50.

- Tokura Y, Hayano S. Subtypes of atopic dermatitis: from phenotype to endotype. Allergol Int 2022;71(1):14-24.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP, Roh EK. Atopic dermatitis. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2017:34-40.

- Chopra R, Vakharia PP, Sacotte R, et al. Severity strata for Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), modified EASI, Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), objective SCORAD, Atopic Dermatitis Severity Index and body surface area in adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2017;177(5):1316-21.

- Ellis C, Luger T, Abeck D, et al. International Consensus Conference on Atopic Dermatitis II (ICCAD II): clinical update and current treatment strategies. Br J Dermatol 2003;148 Suppl 63:3-10.

- Jones SM. Triggers of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2002;22(1):55-72.

- Wiren K, Nohlgard C, Nyberg F, et al. Treatment with a barrier-strengthening moisturizing cream delays relapse of atopic dermatitis: a prospective and randomized controlled clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23(11):1267-72.

- Islam MZ, Ali ME, Wahab MA, Khondker L, Siddique MRU. Efficacy of topical mometasone furoate 0.1% cream in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Med Today 2014;26(1):36-40.

- Boguniewicz M, Fiedler VC, Raimer S, Lawrence ID, Leung DY, Hanifin JM. A randomized, vehicle-controlled trial of tacrolimus ointment for treatment of atopic dermatitis in children. Pediatric Tacrolimus Study Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;102(4 Pt 1):637-44.

- Queille-Roussel C, Paul C, Duteil L, et al. The new topical ascomycin derivative SDZ ASM 981 does not induce skin atrophy when applied to normal skin for 4 weeks: a randomized, double-blind controlled study. Br J Dermatol 2001;144(3):507-13.

- Ma L, Zhang L, Kobayashi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment in Chinese and Japanese patients aged ≥2 years with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol 2023;50:847-55.

- Ramsay CA, Savoie JM, Gilbert M, Gidon M, Kidson P. The treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical fusidic acid and hydrocortisone acetate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1996;7:S15-S22.

- Goh MS, Yun JS, Su JC. Management of atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Med J Aust 2022;216(11):587-93.

- Van Joost T, Heule F, Korstanje M, van den Broek MJ, Stenveld HJ, van Vloten WA. Cyclosporin in atopic dermatitis: a multicentre placebo-controlled study. Br J Dermatol 1994;130(5):634-40.

- Lee SS, Tan AW, Giam YC. Cyclosporin in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. Ann Acad Med Singap 2004;33(3):311-3.

- Berth-Jones J, Takwale A, Tan E, et al. Azathioprine in severe adult atopic dermatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Br J Dermatol 2002;147(2):324-30.

- Tsakok T, Flohr C. Methotrexate vs. ciclosporin in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children: a critical appraisal. Br J Dermatol 2014;170(3):496-8.

- Grundmann-Kollmann M, Podda M, Ochsendorf F, Boehncke W-H, Kaufmann R, Zollner TM. Mycophenolate mofetil is effective in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 2001;137(7):870-3.

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2016;375(24):2335-48.

- Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br J Dermatol 2021;184(3):437-49.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2021;397(10290):2151-68.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2022;386(4):316-26.

- Klein PA, Clark RA. An evidence-based review of the efficacy of antihistamines in relieving pruritus in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 1999;135(12):1522-5.

- Rodenbeck DL, Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Phototherapy for atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol 2016;34(5):607-13.