Volume 44 Number 2

Evaluating risk factors for development of a parastomal hernia: a retrospective matched case-control study

Lynette Cusack, Fiona Bolton, Kelly Vickers, Amelia Winter, Jennie Louise, Leigh Rushworth, Tammy Page, Amy Salter

Keywords Parastomal hernia, risk factors, stomas, stomal therapy nurses, retrospective matched case-control study

For referencing Cusack L, Bolton F, Vickers K, et al. Evaluating risk factors for development of a parastomal hernia: a retrospective matched case-control study. WCET® Journal 2024;44(2):20-28

DOI

10.33235/wcet.44.2.20-28

Submitted 6 February 2024

Accepted 14 May 2024

Abstract

Aim Identify risk factors most likely to contribute to parastomal hernia development.

Methods Retrospective matched case-control study using retrospective case note reviews. One public and one private South Australian hospital. Ostomates who underwent stoma formation surgery between 2018 and 2021, and did (‘cases’, n=50) or did not (‘controls’, n=50) develop parastomal hernia were matched by ostomy type. Potential parastomal hernia risk factors were identified from the literature and expert opinion to build a case note review tool. Case notes were selected by surgical date from 2018. Analyses were conducted in which univariable logistic regression investigated relationships between potential risk factors and parastomal hernia development. Exploratory subgroup analyses investigated whether relationships between risk factors and development of parastomal hernia differed according to ostomy type.

Results Patient characteristics were summarised descriptively and by hospital. Statistically significant evidence was found of links between development of parastomal hernia and higher BMI (OR for 5 kg/m2 increase: 1.74; 95% CI: 1.19, 2.76), post-operative infection (OR 2.68; 95% CI: 1.04, 7.33), multiple abdominal surgeries (OR 4.21; 95% CI: 1.18, 19.90), time since surgery (OR >30 months: 0.003; 95% CI: 0.0004, 0.02), and aperture size (OR for 1mm increase: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.02,1.24). Sufficient evidence was not found of expected relationships with factors such as smoking, chemotherapy and/or pelvic radiotherapy, lifestyle and activity factors.

Conclusions This study contributes to furthering the understanding of the relationships between known risk factors to inform stomal therapy nurses’ practice in the prevention of a parastomal hernia.

High body mass index, postoperative infection, multiple surgeries, wide diameter of the stoma, and time since surgery of less than 30 months increased the risk of parastomal hernia, other factors did not reach significance probably due to use of an underpowered sample.

Opportunities to repeat this study would further strengthen the necessary evidence of the most important risk factors.

Background

Several conditions may lead to the formation of an intestinal stoma, including bowel/rectal and bladder cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. A stoma is a surgically created opening on the abdomen allowing stool or urine to leave the body via a colostomy, urostomy, or ileostomy. Estimated ostomy numbers vary worldwide. Recent numbers in the United States are more than 725,000;1 European numbers are estimated at around 700,000;2 and Australian numbers are approximately 50,000.3 A parastomal hernia, when the intestines press outward through an abdominal wall defect in the vicinity of the stoma, is one of the most common complications experienced by people (Ostomates) who have had stoma formation surgery.4 While estimated rates of parastomal hernia development vary, many estimates suggest around 50% of people with a stoma will develop a potentially preventable parastomal hernia.4 Parastomal hernias are often painful and disruptive, impairing an Ostomate’s quality of life.5,6,7

A systematic review by Zelga et al,8 identified multiple risk factors that may contribute to developing a parastomal hernia including: body mass index (BMI); tobacco or alcohol misuse; presence of comorbid conditions (such as diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Several surgery-related factors were also identified including type of stoma (e.g. in the small or the large intestine, loop versus end stoma, surgeon’s expertise), position of the stoma on the abdomen and the setting in which the ostomy was created (emergency vs elective). Another factor identified in the literature is malnutrition causing poor healing of the stoma or wound.9 Finally, some research suggests parastomal herniation is more likely to occur in women than men.10

The purpose of this article is, firstly, to report the results on the most likely risk factors that would contribute to the development of a parastomal hernia to refine current parastomal hernia risk assessment tools; and secondly, to document the process of undertaking a retrospective matched case-control study. It is hoped that this will inform replication by future researchers to strengthen the available evidence and advance the understanding of the risks for developing a parastomal hernia. STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies provided direction on reporting.11

Methods

Research Design

A retrospective matched case-control study by way of case note review was undertaken to identify risk factors that appear to have strongest association with development of parastomal hernia after surgery.

Setting

The case note review was conducted at two sites: one major metropolitan public hospital and one smaller private metropolitan hospital in South Australia where stoma surgery is undertaken. Experienced stomal therapy nurses are employed at both hospitals working closely with colorectal surgeons to provide support to Ostomates.

Participants

The retrospective case note review consisted of two participant groups of Ostomates who had stoma formation surgery between 2018–2021. Group 1 were ‘cases’: a selection of case notes of some, not all, Ostomates who developed a parastomal hernia within this time frame (after original surgery) (n=50). The second group were controls: a selection of case notes of Ostomates who did not develop a parastomal hernia between 2018–2021 (after original surgery) (n=50), and they were proportionally matched according to type of ostomy. The identification and reporting of parastomal hernias were informally diagnosed by stomal therapy nurses or by confirmed computed tomography scans following medical review for suspected parastomal hernia. Selection of case notes was sequential, starting with the earliest surgeries from 2018. An equal number of case and control notes was to be selected from each of the two hospitals, with the intention that each hospital provide 25 case and 25 control case notes. However, this was not able to be achieved due to availability of case notes on each site. Therefore, 99 case notes were analysed: 50 from the public hospital (25 cases and 25 controls), and 49 from the private hospital (23 case and 26 control).

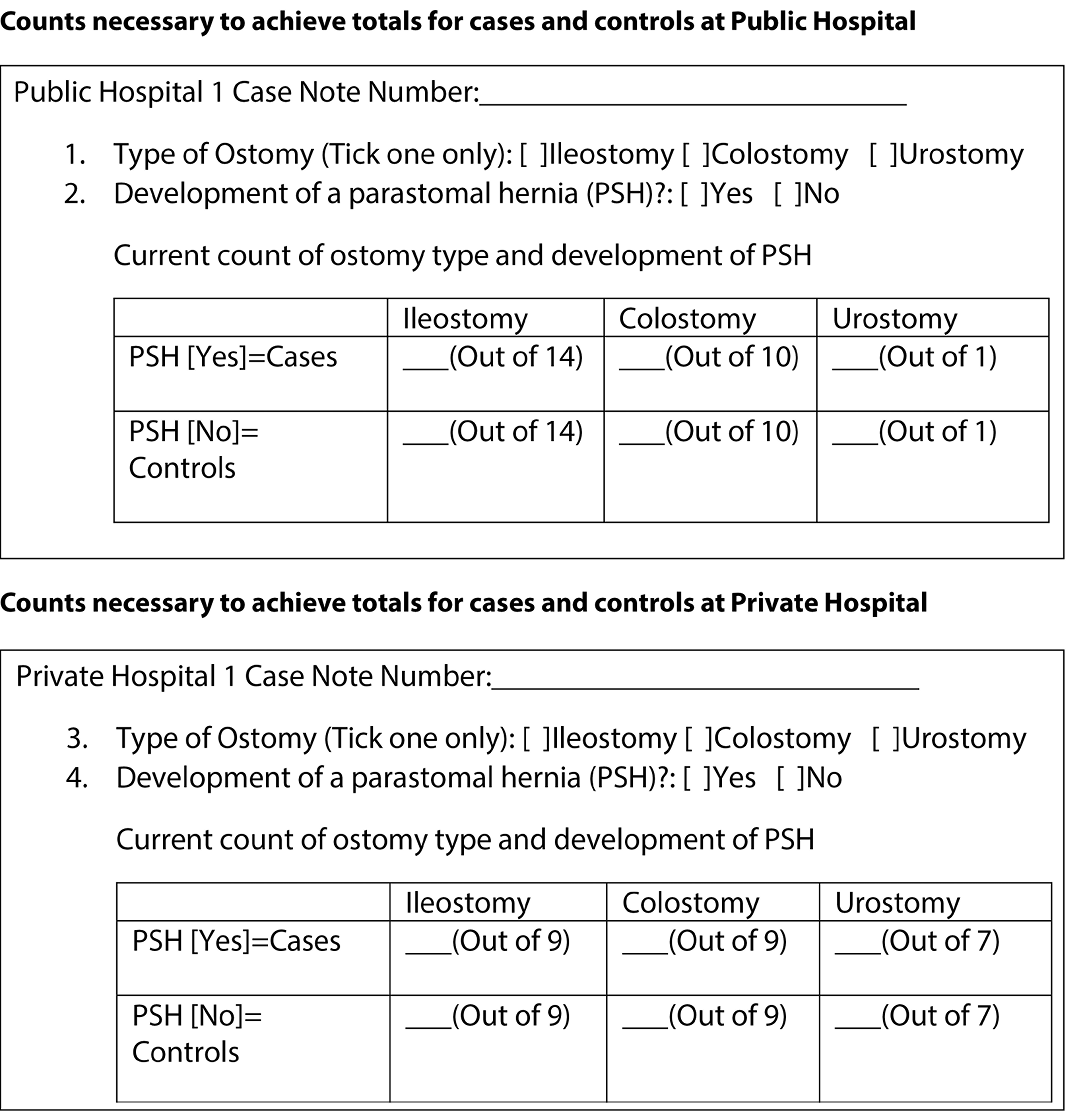

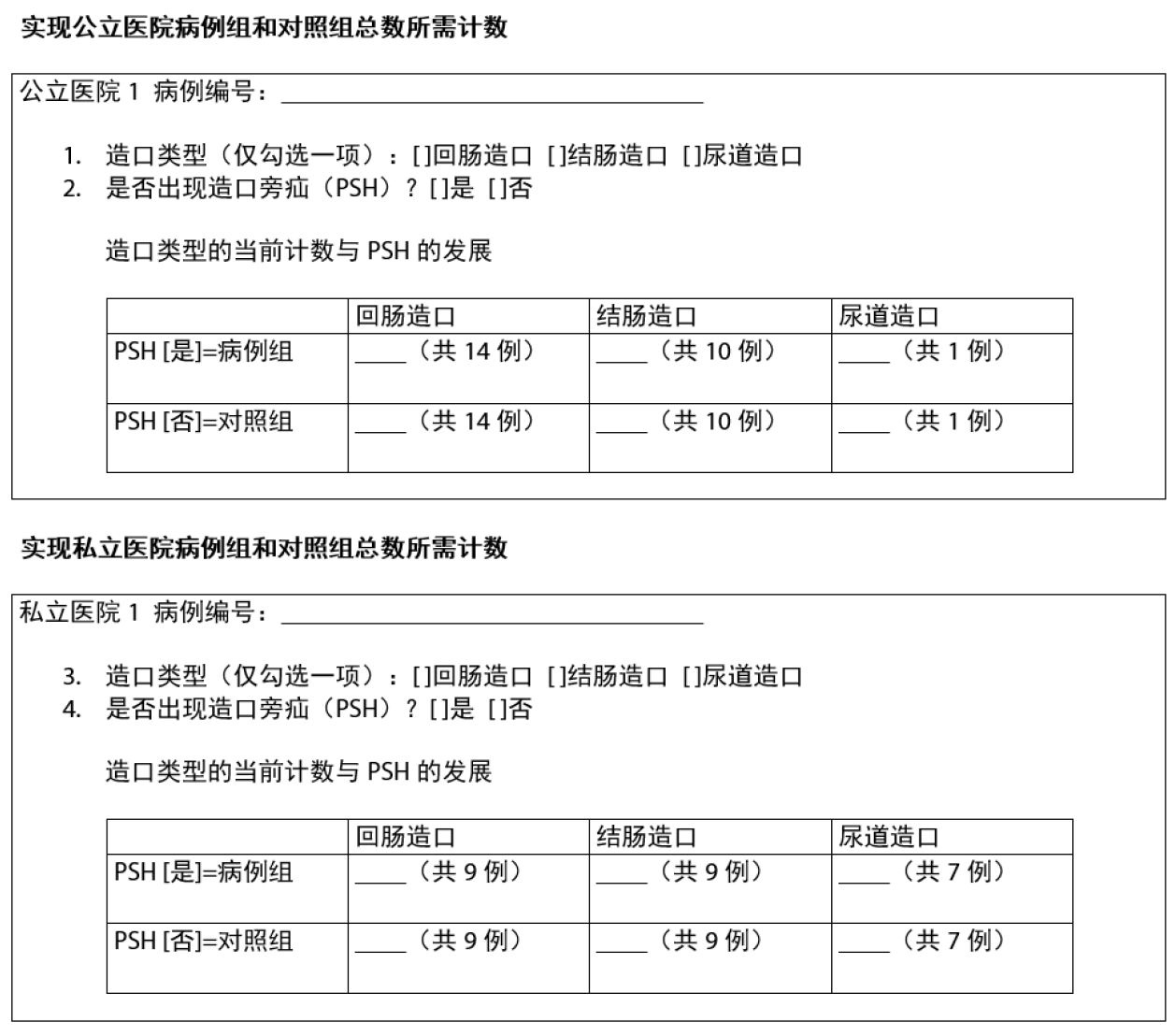

To ensure appropriate representation of ostomy type at each of the two hospitals (with different ostomy profiles), approximate observed proportions between 2018 and 2021 were purposively, or specifically, sampled. At the public hospital the proportion was 56% Ileostomy/40% Colostomy/4% Urostomy, while at the private hospital the proportion was 36% Ileostomy/36% Colostomy/28% Urostomy which corresponds with the percentage of ostomy surgery type at each respective hospital. To achieve these proportions, this meant (for example) ignoring notes from one ostomy type if the requisite quota for that type had already been met (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Format for determining sampling for each hospital based on Ostomy type and presence of parastomal hernia.

Review tool and data sources

The case note review tool was developed through identifying key risk factors for parastomal hernias from the literature, the Association of Stoma Care Nurses, United Kingdom Risk Assessment Tool,12 two previous Australian studies of stomal therapy nurses’ perceptions13 and the lived experiences of Ostomates.14 The multidisciplinary nature of the research team was critical in the development and appraisal of the review tool to ensure input of relevant academic and clinical experience including physiotherapy, stomal therapy, and psychology, as well as a robust understanding of the evidence base (from biostatisticians). To ensure inter-user reliability and consistency in data collection, the final review tool was piloted by four members of the research team, who held positions in each hospital, until 100% agreement was reached on the items within the review tool. Four case notes each from the case and control groups were piloted. These case notes were not included in the final review. Assessing activity levels proved difficult when piloting the tool. However, the decision to include the metabolic equivalent of task (frequently referred to as METs)15 made this more feasible. This tool was often used by anaesthetists and was therefore recorded in the patients’ preoperative anaesthetic assessment. Other minor changes were made to the review tools’ wording and items to improve clarity and relevance.

Data collection and Statistical methods

Using patient case note numbers (unit records), case notes for review were selected through sequential selection from a list from each hospital. The case note review tool was manually completed for each case note by the four researchers from the two hospitals involved, as both hospitals still used hardcopy case notes.

Data from the review forms were imported from Excel into R v4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) for cleaning and subsequent analysis, according to a pre-specified analysis plan. Patient characteristics were summarised descriptively both overall and by study centre. Univariable relationships between pre-specified potential risk factors and development of a parastomal hernia were analysed using logistic regression. For binary risk factors, estimates were reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for ‘yes’ vs ‘no’; for nominal or ordinal risk factors estimates were reported as OR and 95% CI for each subsequent level versus a reference level; and for continuous risk factors, estimates were reported as OR and 95% CI for a stipulated increase. All models were adjusted for type of ostomy (variable used for matching cases and controls), and some models were additionally adjusted for year of surgery. Exploratory subgroup analysis was also carried out to investigate whether relationships between risk factors and development of parastomal hernia differed according to type of ostomy. An interaction term between ostomy type and risk factor was included in the model, and separate estimates of risk (as OR) were obtained for each ostomy type.

Ethics

This project received approval from both the public and private hospitals Human Research Ethics Committees: Central Adelaide Local Health Network Ref 16705: St Andrews Hospital Number 138: University of Adelaide H-2020-231. The research team sought waiver of patient consent from each Ethics Committee, which was approved based on the assurance of anonymity and confidentiality by not reporting identifiable information about individuals. Strict processes of access and storage of case notes were followed according to each hospital’s policy during data collection.

Results

Process and Descriptive Statistics

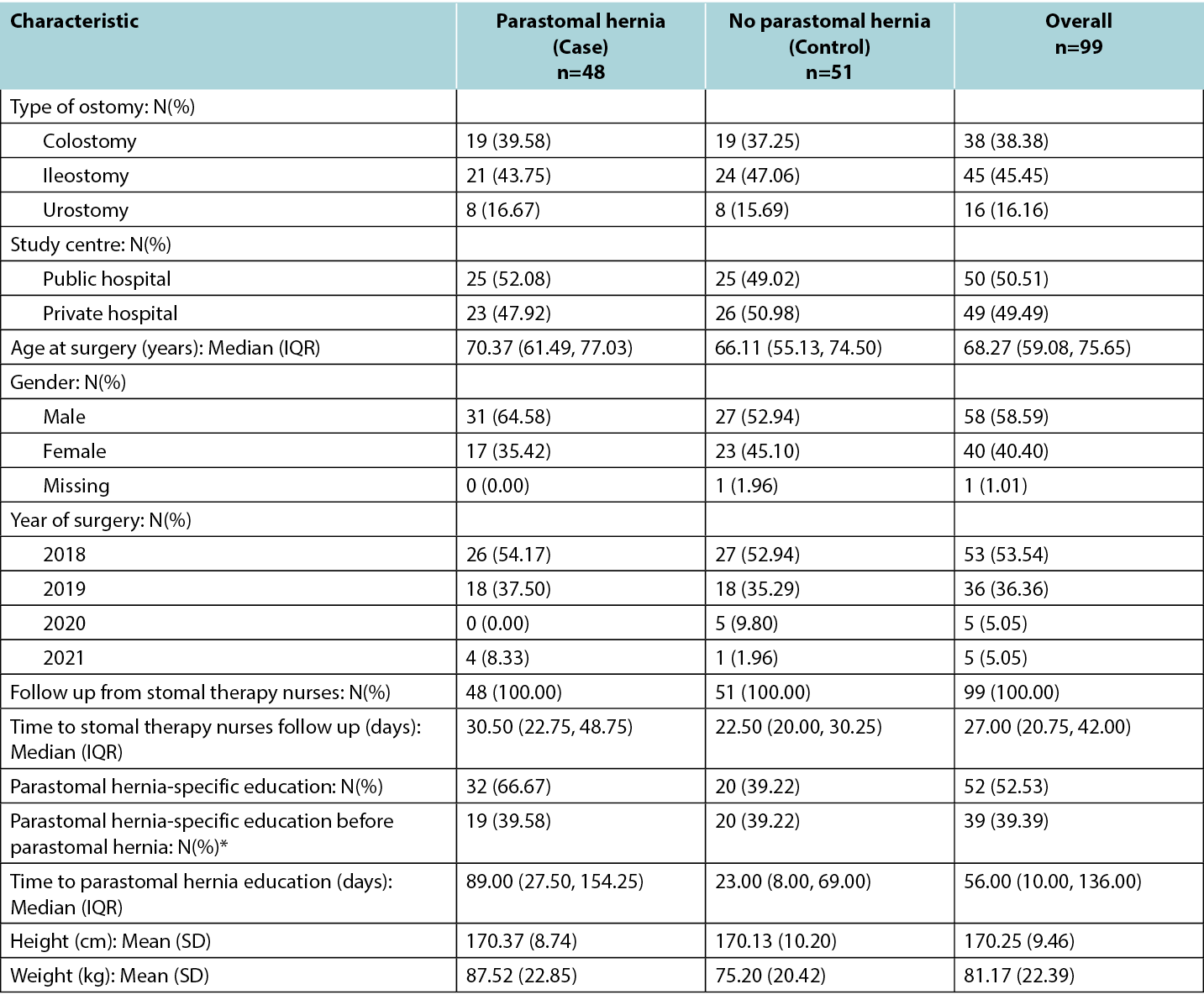

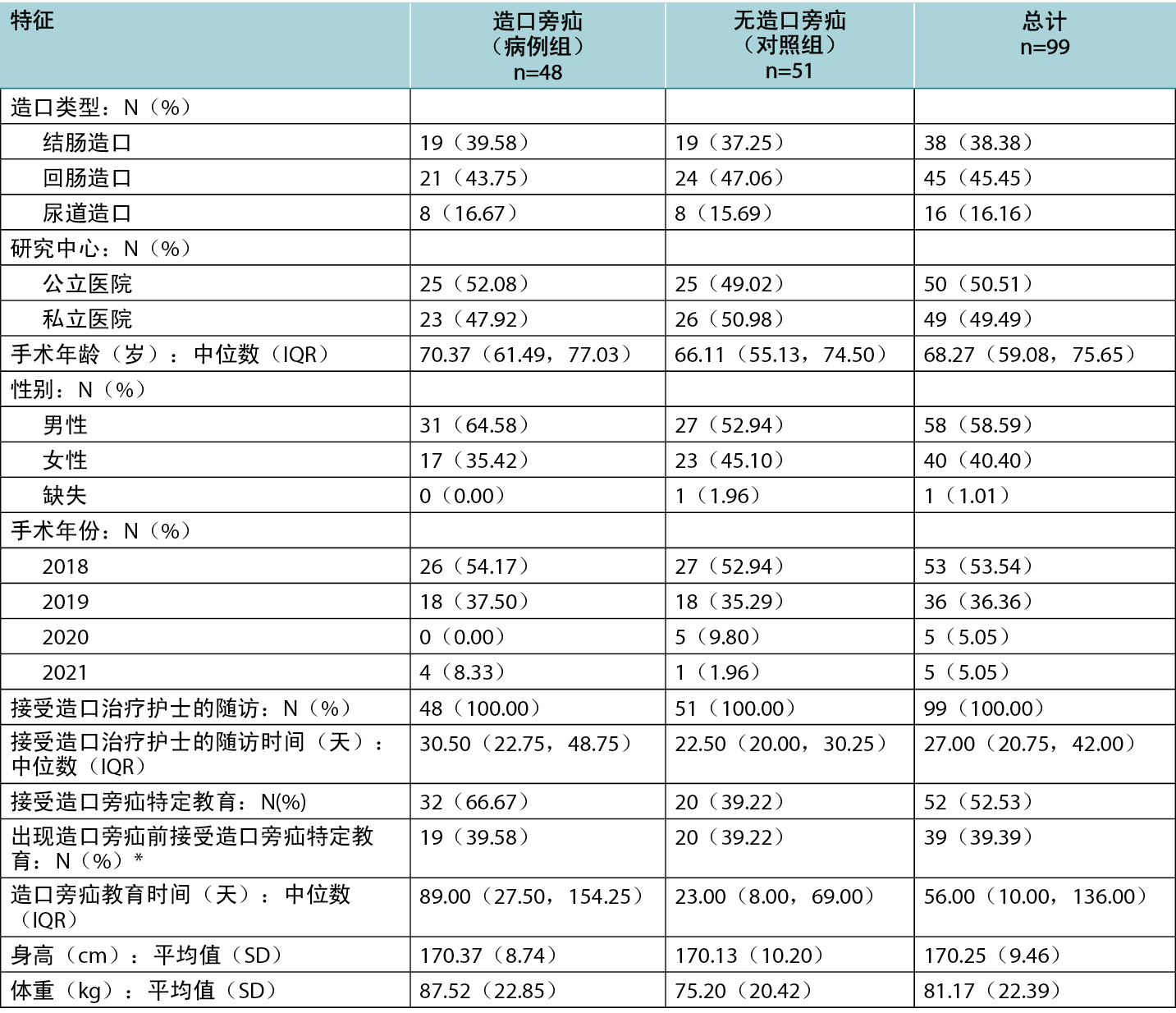

The approach for the matched case-control study was necessarily pragmatic, given that the number of case notes reviewed was limited by time available to the researchers and ability to access case notes within the hospital. As neither hospital had electronic records, original hard copy case notes were accessed. This process was very time consuming. Table 1 reports characteristics of included participants, by case/control status and overall. The numbers for cases (parastomal hernia) and controls (no parastomal hernia) are not precisely equal for each ostomy type. Patient characteristics differed slightly between cases and controls, with cases being slightly older (median age 70.37 years compared to 66.11 years for controls), more likely to be male (64.6% of cases compared to 52.9% of controls) and having a higher mean weight (87.5 kg compared to 75.2kg for controls). The rate of follow up from stomal therapy nurses was 100% in both groups, and the proportion of patients receiving parastomal hernia-specific education prior to development of a hernia was similar in cases (39.6%) and controls (39.2%).

Patient characteristics were similar between the two study centres (See Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants by case/control status and overall.

Potential risk factors

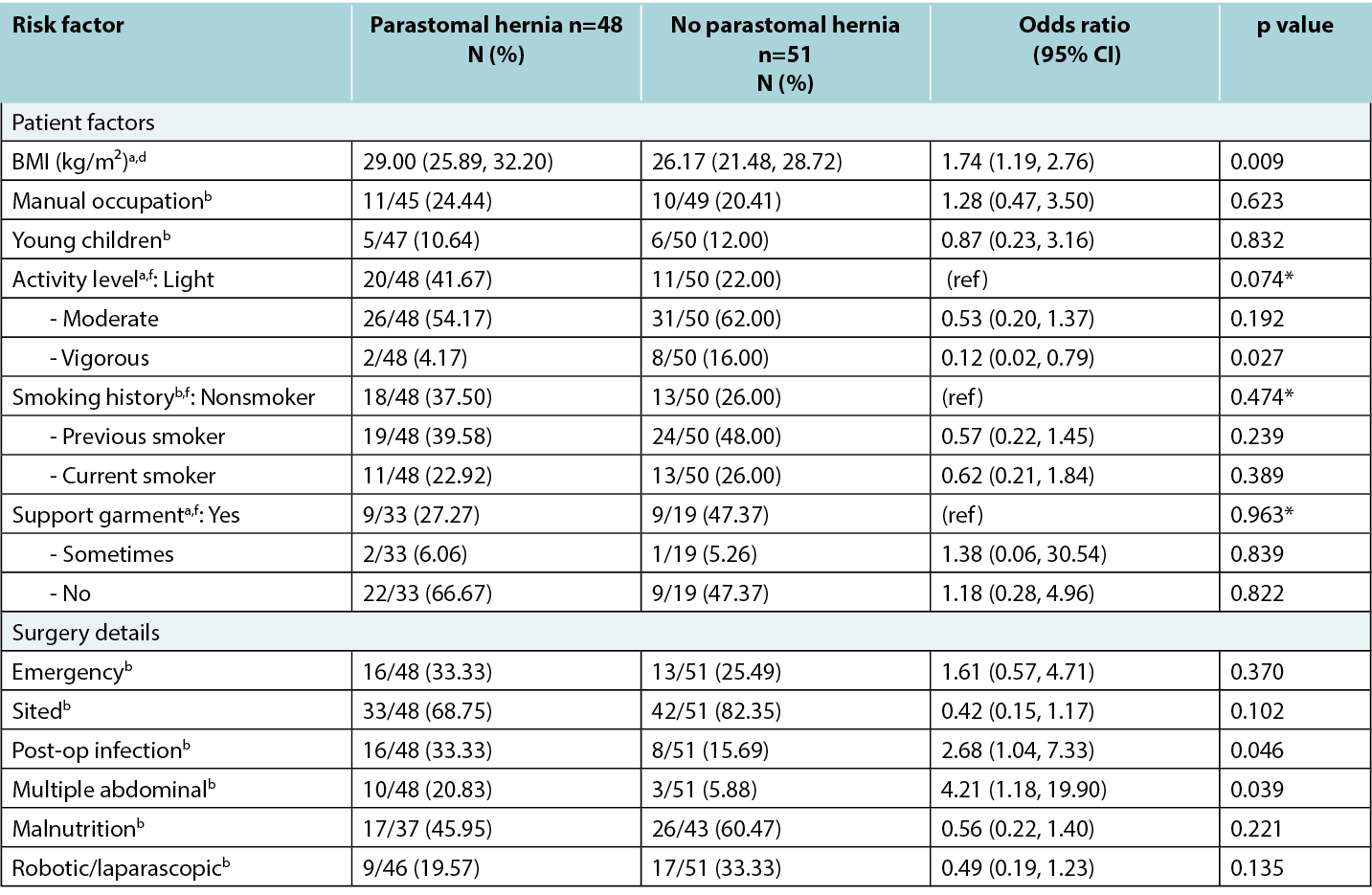

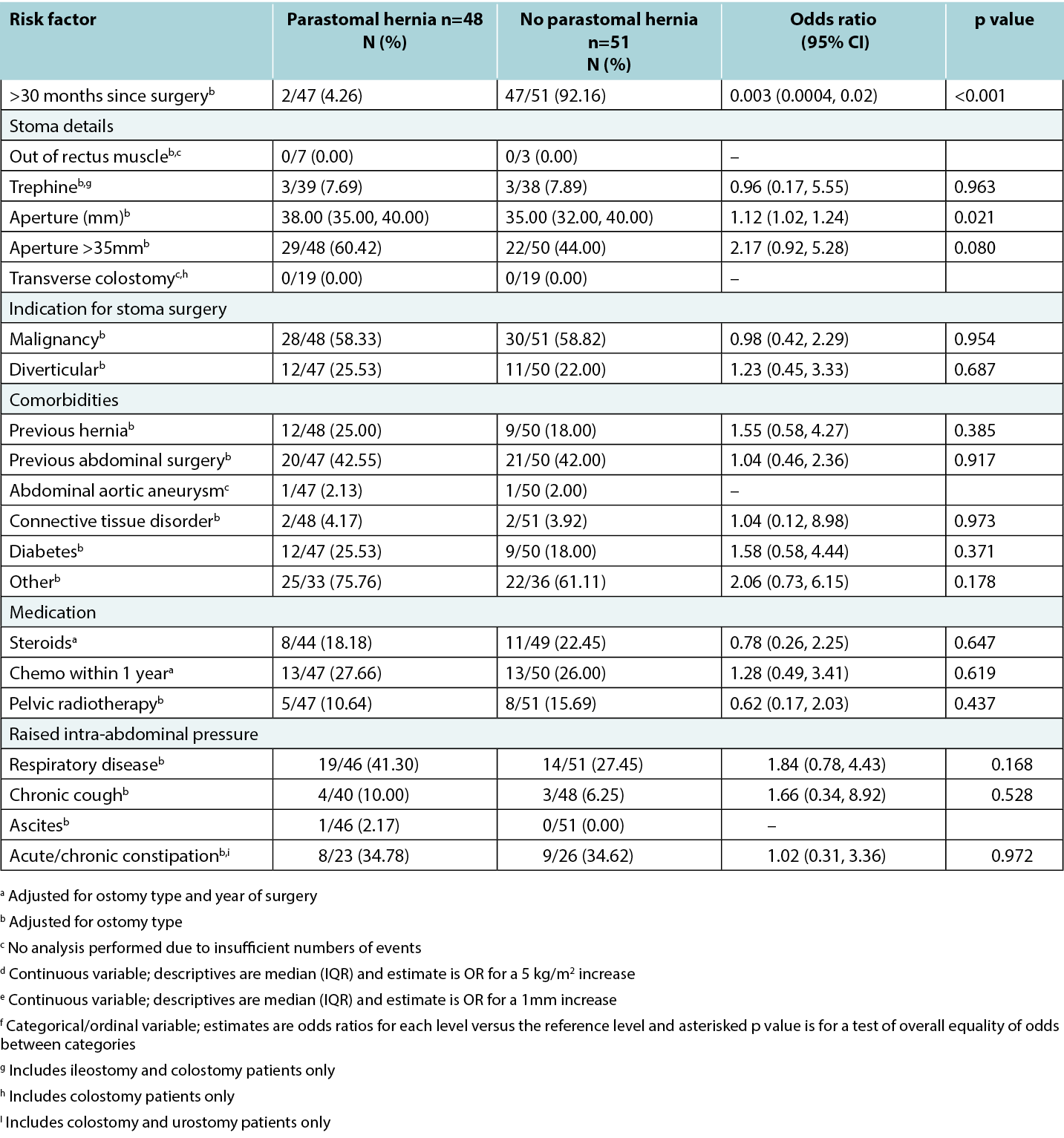

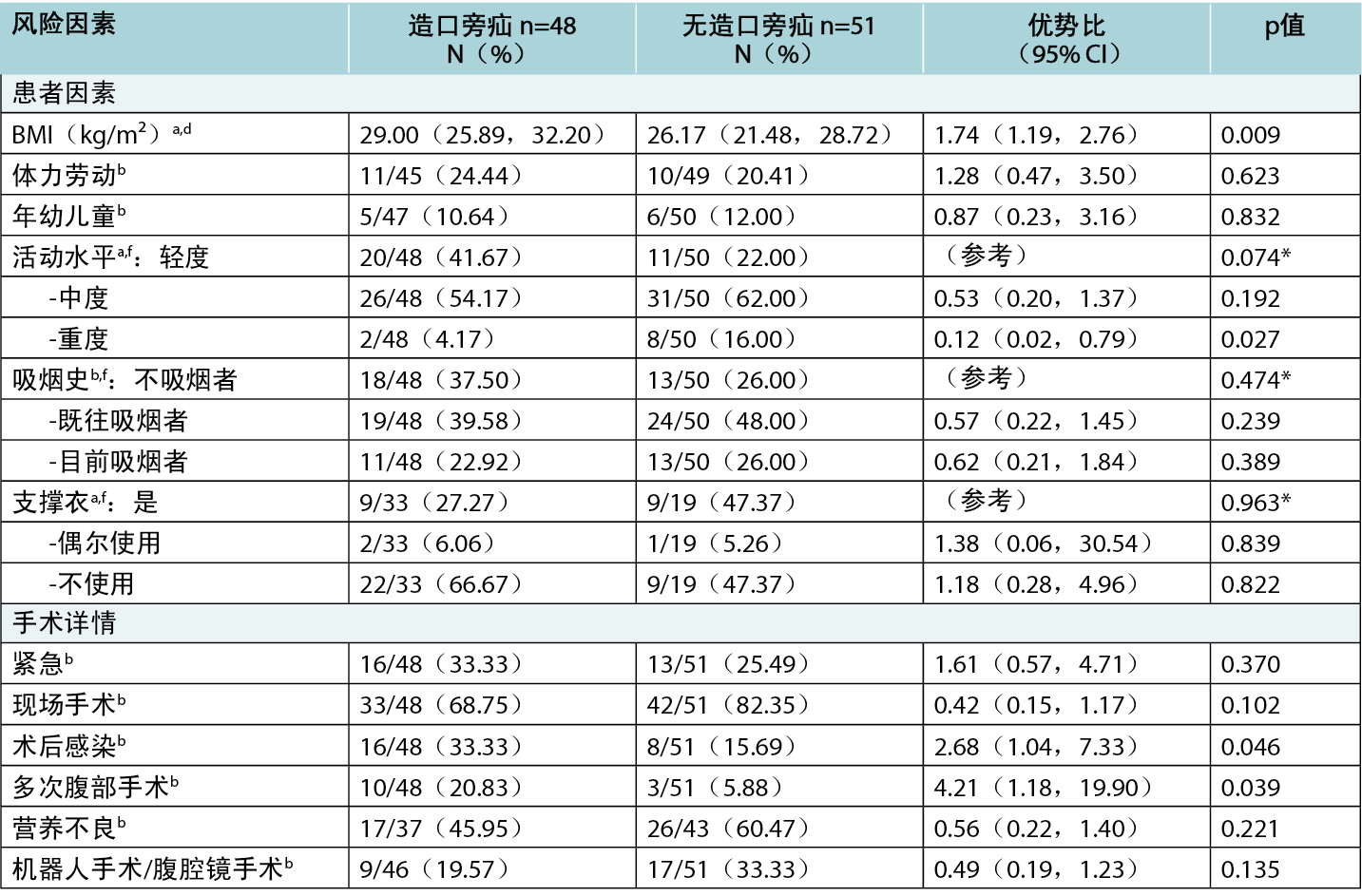

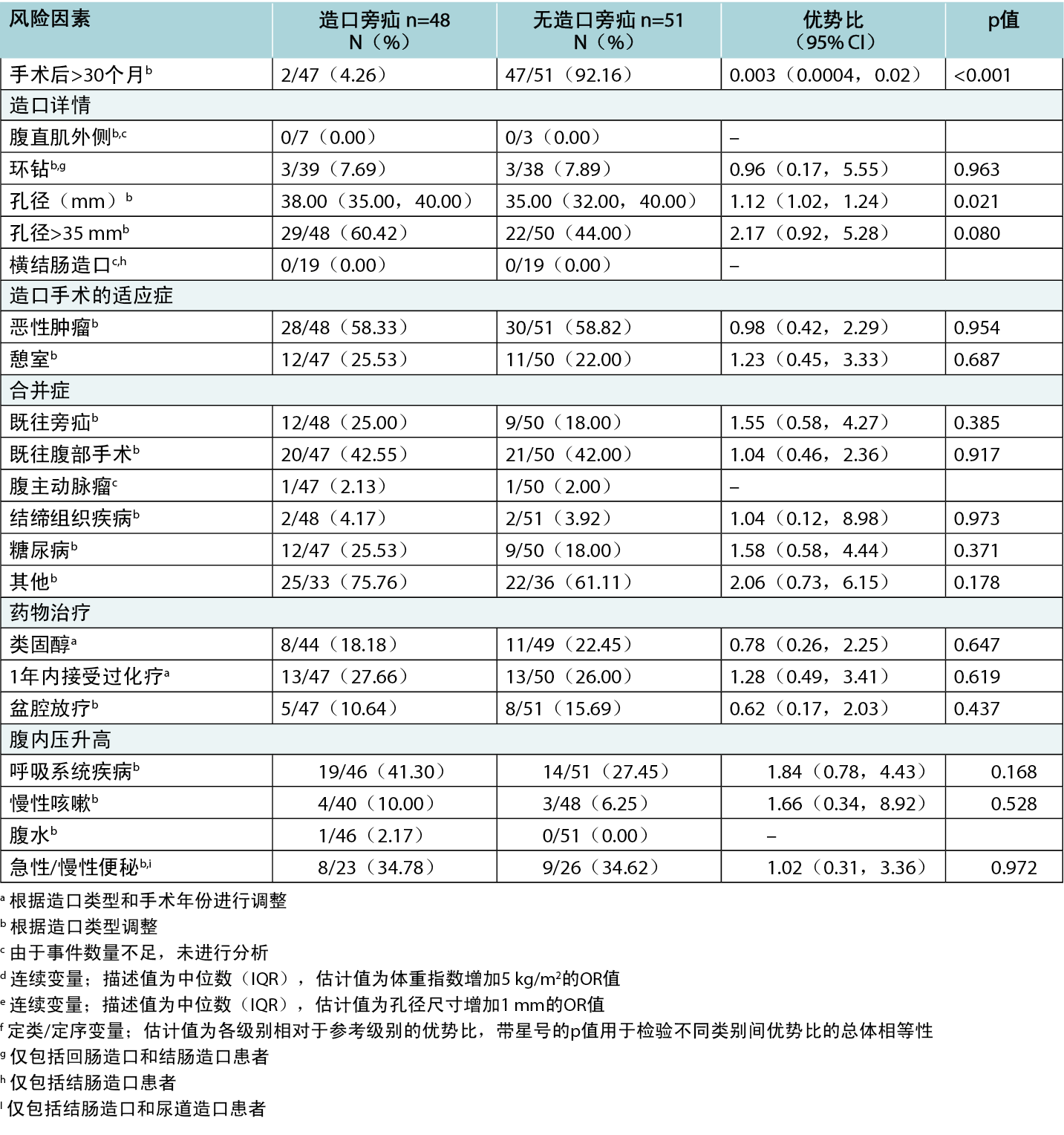

Table 2 reports results of univariable analyses of all risk factors. For most factors there was no evidence of an association with risk of developing parastomal hernia; however, there was evidence of an increased risk of parastomal hernia with higher BMI (OR for a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI 1.74, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.76), and for increased aperture size (OR for 1mm increase in aperture size 1.12, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.24). The aperture size was identified from the patients’ case notes at first STN review post operatively (approx. day 1–3). The risk of parastomal hernia also decreased significantly at >30 months after surgery, with an odds ratio of 0.003 (95% CI: 0.0004 to 0.02). For other factors, there was some evidence that multiple abdominal surgery and post-operative infection increased the risk of parastomal hernia; however, due to relatively small numbers, the confidence intervals for the estimated odds ratios were too wide to be meaningful. Similarly, there was some evidence that higher levels of activity reduce the risk of parastomal hernia, with a statistically significant decrease in odds for those whose activity level was ‘vigorous’ compared to ‘light’. However, there were only small numbers of participants with this level of activity, limiting statistical power.

Table 2. Results of univariable analyses of all risk factors.

In some cases, potential risk factors could not be analysed due to small numbers; for example, only one participant had ascites and only two experienced abdominal aortic aneurysms. Stoma placed out of the rectus muscle had no recorded instances. Siting within the rectus sheath could not be ascertained from medical notes for the majority of participants since it was not clearly documented either before or after surgery. While the proportion of Ostomates using support garments was considerably higher in Ostomates without a parastomal hernia evidence of this relationship was not statistically significant. This may have been due to a large proportion of missing data, especially in the control group, decreasing the power to detect the nature of the relationship.

Subgroup analysis by ostomy type

Subgroup analysis did not reveal any evidence of differences between type of ostomy in the relationship between potential risk factors and development of parastomal hernia. It is prudent to be mindful, however, that this does not mean that no differences exist, as in many cases, the numbers were too small when broken down by ostomy type for analysis to be sensible.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify risk factors that appear to have strongest association with development of a parastomal hernia. It is anticipated that the results will help to refine current risk assessment tools and provide other clinicians and researchers working with Ostomates with a protocol to replicate and gather further evidence regarding parastomal hernia risk.

Completing the case note review

The process of the case note review is outlined in the methods section; however, some additional issues should be highlighted given the invitation to replicate. The review found that many patients had a long history of medical care and so it was not unusual to have a number (three to six) case note files reviewed for each patient which had not been factored into the allocation of time per patient review. Quality of information available within the patient case notes varied; while the reviewers were able to ascertain more precise information regarding body mass index and aperture size than anticipated, information regarding siting of stomas was not well documented. Additionally, documentation regarding discussion with patients on parastomal hernia prevention and support garment use was often only provided when patients had a parastomal hernia, leading to ascertainment bias; the reported results regarding support garment use are therefore possibly not a true reflection of the relationship with parastomal hernia.

The nature of the recording of two risk factors was enhanced during the review process. Following the UK risk assessment tool,12 obesity (BMI greater than 30) and stoma aperture size greater than 35mm had been added. However, documentation in the case notes allowed for the recording of these as continuous variables. Specifically, case notes included specific aperture size at first STN review post operative review, as well as height and weight of patients which allowed the reviewers to calculate specific body mass index. This is a strength of the study, as reporting aperture and body mass index as continuous variables allowed for higher statistical power and for specific odds ratios to be calculated, providing a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between body mass index and aperture size and parastomal hernia.

BMI

Results of this case note review indicate that patients with higher BMI or larger stoma aperture were more likely to develop a parastomal hernia. In particular, for every 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI, the chances of parastomal hernia increased 74%. This is a particularly important finding as the study’s population is known to have higher than average Body Mass Index, especially at the public hospital located in a lower socioeconomic area. A link between socioeconomic status and obesity has been established.16

Surgery related factors

Some evidence was also found regarding increase in parastomal hernia risk for patients with multiple abdominal surgeries and post-operative infection, however small numbers of patients with these risk factors affected the statistical power to determine risk. While previous literature,4,10,18,19,20,21 suggests increased parastomal hernia risk from some surgery-related factors (rectus muscle, trephine stoma; transverse colostomy) and ascites,22 these potential risk factors could not be examined due to insufficient data (i.e., the number of case notes with these features recorded was not high enough to calculate an odds ratio with sufficient power). Further, for every 1mm in increased aperture, the risk of hernia increased by 12%. This is consistent with previous literature reporting that for every millimetre increase in aperture size, the risk of parastomal hernia increased 10%.8 Additionally, a parastomal hernia is most likely to develop in the first 30 months post-surgery.

Smoking

Interestingly, while previous literature has suggested smoking to be a risk factor for parastomal hernia,12 no evidence of a relationship between smoking and parastomal hernia was found in this study. This was surprising given the tendency of smokers to cough, increasing intra-abdominal pressure and leading to abdominal straining.22 Overall, tobacco smokers are known to have poorer post-surgical outcomes, due to reduced oxygen and nutrient flow throughout the body, delaying healing.24 There is some suggestion that nicotine use may inhibit cell repair, however this has not been a focus of research within the context of parastomal hernia.17

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

No evidence was found of a link between chemotherapy and radiotherapy within a year of surgery, and parastomal hernia development due to a weakening of muscles due to treatment. However, previous studies26 have shown a link. It is possible no effect was found in the recent study due to small sample size, and, therefore, this should be investigated further.

Overall, the significant findings of this study are in keeping with much of the previous literature,8,17,20,22 which reassures its relevance in the Australian setting and motivates the need for clarification on other potentially important factors that potentially require further study with more case notes.

Limitations

Consideration should be given to this study’s limitations. Firstly, while the pragmatic design was necessary given the clinical context of the research (busy metropolitan hospitals with non-digitised case notes), this did leave the study underpowered to detect potential risk for some factors, particularly co-morbidities and additional treatments, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Future research could include prospective data collection of a powered sample from a multi-centric study with long follow-up of the risk factors for parastomal hernia.

Additionally, each hospital had its own protocols for documentation, assessment, and action. For example, one hospital has a pathway which directs staff to contact the diet aid or dietitian to assess a patient if their Body Mass Index is low, had lost significant weight unintentionally, or had poor appetite, while the other hospital employed a dietitian who undertook a comprehensive assessment, including routine blood tests e.g., iron, magnesium levels, regardless of BMI. Such differences in protocols may have affected the data.

The assessment of the heavy lifting risk factor was problematic as very little data was recorded in case notes, and any available notes were often ambiguous. This is not particularly surprising due to the subjective nature of the question. However, this meant occupational and recreational activities that required heavy lifting could not be adequately assessed as a risk factor.

Practices had changed over time at each of the hospitals. For example, in the case notes of one hospital, cases before 2021 generally made little reference to parastomal hernia education, however after 2021 this was consistently documented which again could impact the quality of the data collected.

Finally, reporting of the measurement of the stoma was undertaken from a pragmatic point of view as there is no consensus about when to measure the stoma post-operatively to determine the risk of parastomal hernia formation. It is understood that the stoma will change in size and shape post-operatively and generally be at a consistent size at 6 to 8 weeks. When a patient develops a parastomal hernia the stoma may change in size and shape.25 It was observed in the clinical setting at both hospital sites that patients were occasionally developing a parastomal hernia at or before 6 weeks post-operatively. Therefore, the decision was made to measure at the first review post-surgery for consistency. Hence the larger number of stomas over 35mm. The best time to measure an aperture with respect to understanding this as a risk factor is an area for future research.

While the matched case-control design of this study increases the chances of representative data, the issues outlined above mean the findings may not be generalisable more broadly to people with a stoma.

Conclusion

This study was the first of its kind in Australia to synthesise previous findings relating to parastomal hernia risk and to conduct a retrospective case note review to refine these risk factors. As parastomal hernias often impair an Ostomate’s quality of life,5 it is important to continue to understand the potential risk factors to better inform preventative management. By outlining the process of this study our hope is that it may guide future studies by clinicians and researchers in other health settings to enhance the necessary evidence of important risk factors.

High body mass index, postoperative infection, multiple surgeries, wide diameter of the stoma and time since surgery less than 30 months increased the risk of parastomal hernia, other factors did not reach significance probably due to use of an underpowered sample.

The research team found many issues of missing information, particularly related to patient factors, such as lifting and other lifestyle factors. It is recommended that tools to record activity (such as the metabolic equivalent of task15), and for lifting (the Dictionary of Occupational Title23) which are used in other settings and could be incorporated into stomal therapy nurses assessment process.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Divisional and Executive Nursing Directors of the two hospitals: (Northern Adelaide Local Health Network and St Andrews Hospital), South Australia, and Clinical Record Units for their assistance and support of this project.

We also acknoweldge the Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK (ASCN UK) Risk Assessment Tool which inspired us to undertake a series of research studies in Australia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Statement

Central Adelaide Local Health Network Human Research Ethics Committee H-2020-231: St Andrews Hospital Number 138 and University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee Ref. 16705.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Adelaide. Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences.

评价发生造口旁疝的风险因素:一项回顾性匹配病例对照研究

Lynette Cusack, Fiona Bolton, Kelly Vickers, Amelia Winter, Jennie Louise, Leigh Rushworth, Tammy Page, Amy Salter

DOI: 10.33235/wcet.44.2.20-28

摘要

目标 识别最有可能导致造口旁疝发生的风险因素。

研究方法 通过回顾性病例记录审查,进行回顾性匹配病例对照研究。研究在南澳大利亚的一家公立医院和一家私立医院开展。2018年至2021年间接受造口手术的患者,其中发生造口旁疝的患者作为“病例组”(n=50),未发生造口旁疝的患者作为“对照组”(n=50),并按造口类型进行匹配。基于文献回顾和专家意见,识别潜在的造口旁疝风险因素,并构建病例记录审查工具。选取2018年开始的手术日期病例记录进行分析。通过单变量logistic回归分析探究潜在风险因素与造口旁疝形成之间的关系。探索性亚组分析研究了不同造口类型下,风险因素与造口旁疝形成之间的关系是否存在差异。

结果 对患者特征进行了描述性总结,并按医院进行了分类。有统计学意义的证据表明,造口旁疝的形成与以下各项因素有关:较高的BMI(BMI每増加5 kg/m2,OR:1.74;95% CI:1.19,2.76)、术后感染(OR:2.68;95% CI:1.04,7.33)、多次腹部手术(OR:4.21;95% CI:1.18,19.90)、手术后时间(>30个月,OR:0.003;95% CI:0.0004,0.02)和造口孔径大小(每増加

1 mm,OR:1.12;95% CI:1.02,1.24)。对于与吸烟、化疗和/或盆腔放疗、生活方式和活动因素等因素的预期关系,并未发现足够的支持。

结论 本研究深化了对已知风险因素之间关系的理解,为造口治疗护士在预防造口旁疝方面的实践提供了依据。

高体重指数、术后感染、多次手术、造口直径过宽、手术后时间少于30个月等因素均増加了造口旁疝的风险,而其他因素则没有达到显著性水平,这可能是由于样本量不足。

未来重复此类研究将进一步强化对最重要风险因素的必要证据。

背景

多种状况可导致肠造口的形成,其中包括肠癌/直肠癌、膀胱癌以及炎症性肠病。造口是指通过外科手术在腹部创建一个开口,以便粪便或尿液通过结肠造口、尿道造口或回肠造口排出体外。全球范围内估计的造口患者数量各不相同。最近数据显示,美国有超过725,000造口患者;1欧洲约为700,000造口患者;2澳大利亚则大约有50,000造口患者。3造口旁疝,即肠道通过造口附近腹壁缺损向外膨出,是经历过造口手术的患者(造口患者)经历的最常见并发症之一。4虽然造口旁疝发生的估计比率各不相同,但许多估计表明,约50%造口患者可能发生潜在可预防的造口旁疝。4造口旁疝通常会造成疼痛和破坏,影响造口患者的生活质量。5,6,7

Zelga等人的一项系统综述回顾指出8,与造口旁疝形成相关的风险因素众多,包括体重指数(BMI)、烟草或酒精滥用、合并症(如糖尿病、冠状动脉心脏疾病、高血压及慢性阻塞性肺疾病)。此外,还识别出若干与手术相关的因素,如造口类型(位于小肠或大肠、环状或末端造口)、外科医生的经验水平、腹部造口位置以及造口手术实施的背景(急诊或择期手术)。文献中还提及营养不良作为影响因素,导致造口或伤口愈合不良。9 最后,一些研究表明,女性比男性更容易发生造口旁疝。10

本文旨在首先报告最可能促进造口旁疝形成的风险因素研究成果,以完善目前的造口旁疝风险评估工具;其次,记录进行回顾性匹配病例对照研究的过程。希望未来的研究人员能借鉴这一研究成果,以加强现有证据,并加深对造口旁疝发生风险的理解。STROBE观察性研究报告指南为报告提供了指导。11

方法

研究设计

本研究采用回顾性匹配病例对照研究设计,通过病例记录审查的方式,识别与术后造口旁疝形成关联最强的风险因素。

研究地点

病例记录审查工作在两家研究中心进行:南澳大利亚的一家大型都市公立医院,以及该地区一家规模较小的私立医院,两家医院均开展造口手术。两家医院均配备有经验丰富的造口治疗护士,他们与结直肠外科医师紧密合作,为造口患者提供支持。

受试者

病例记录审查涉及两组在2018至2021年间接受过造口形成手术的受试者。第1组为“病例组”,选取此期间(首次手术后)内部分(非全部)发生造口旁疝的造口患者病例记录(n=50)。第二组为“对照组”,选取2018年至2021年间(首次手术后)未发生造口旁疝的患者病例记录(n=50),并根据造口类型按比例匹配。造口旁疝的识别与报告主要由造口治疗护士根据临床观察进行非正式诊断,或在对疑似造口旁疝进行医疗审查后,通过计算机断层扫描进行确认。病例记录选择从2018年的最早手术记录开始,按时间顺序进行。原计划从两家医院各挑选出同等数量的病例组和对照组病例记录,每家医院各提供25份病例组和25份对照组病例记录。但由于研究中心获取病例记录的限制,未能实现这一目标。因此,实际分析了99份病例记录:公立医院50份(病例组25份,对照组25份),私立医院49份(病例组23份,对照组26份)。

为确保两家医院造口类型的代表性(各医院造口构成比例不同),按照2018至2021年间的大致观察比例有针对性地抽样。公立医院的比例为回肠造口56%,结肠造口40%,尿道造口4%;私立医院的比例为回肠造口36%,结肠造口36%,尿道造口28%,这与各医院造口手术类型的比例相对应。当某一类型造口的病例记录数量达到预设配额时,则不再纳入该类型其他病例记录(见图1)。

图1.根据造口术类型和是否存在造口旁疝确定每家医院的抽样形式。

审查工具和数据来源

病例记录审查工具的开发,其基础源于对文献中关键造口旁疝风险因素的深入剖析,同时参考了造口护理护士协会的专业指导、英国风险评估工具的实践经验,12以及两项来自澳大利亚的前期研究13Å\Å\这些研究聚焦于造口治疗护士的洞见与造口患者的真实生活体验。14本研究团队拥有多学科背景,这一点在审查工具的开发与评估过程中发挥了至关重要的作用。团队成员涵盖了物理治疗、造口治疗、心理学及生物统计学等领域,他们的学术与临床经验为工具的设计提供了宝贵的参考,同时也确保了我们对证据基础有着坚实的理解。

为确保不同使用者之间的操作一致性与数据收集的可靠性,我们特别邀请了研究团队的四位核心成员(均来自研究合作医院)对最终的审查工具进行实地试用。经过反复讨论与修订,团队成员就审查工具的所有内容达成了全面共识。在试用阶段,我们特意选取了病例组和对照组各四份病例记录进行测试,但这些记录并未被纳入最终的数据回顾。在试用过程中,我们发现在评估活动水平时存在一定的难度。为了克服这一难题,我们决定引入代谢当量(通常称为MET)15作为评估指标,这一改进显著提高了评估的可行性。值得注意的是,麻醉师在日常工作中已广泛采用此工具,并将其记录在患者的术前麻醉评估中。此外,为了进一步提升工具的清晰度和相关性,我们对审查工具的措辞和具体项目进行了细致的优化调整。

数据收集和统计方法

利用患者病例编号(单位记录),从每家医院的清单中按顺序挑选出需要审查的病例。由于两家医院仍在使用硬拷贝病例记录,来自两家医院的四名研究人员使用病例记录审查工具手动完成了每份病例记录的审查。

根据预先设定的分析计划,将审查表中的数据从Excel导入R v4(R统计计算基金会)进行清理和后续分析。对总体和各研究中心的患者特征进行了描述性总结。采用logistic回归分析了预先设定的潜在风险因素与造口旁疝形成之间的单变量关系。对于二元风险因素,以“是”与“否”的优势比(OR)和95%置信区间(CI)来报告估计结果;对于定类或定序风险因素估计结果,以各项后续级别相对于参考级别的OR和95% CI报告;而对于连续风险因素,则以特定増幅的OR和95% CI报告。所有模型均根据造口类型(用于匹配病例组和对照组的变量)进行了调整,部分模型还根据手术年份进行了调整。此外,还进行了探索性亚组分析,以研究不同造口类型下风险因素与造口旁疝形成之间关系的差异。模型中包含了造口类型与风险因素的交互项,并对每种造口类型分别进行了风险估计(OR)。

伦理批准

本项目已获得公立和私立医院人类研究伦理委员会的批准:中央阿徳莱徳地方健康网络(编号16705)、圣安徳鲁斯医院(编号138)、阿徳莱徳大学(H-2020-231)。研究团队向各伦理委员会申请了患者知情同意书豁免,在保证匿名和保密的基础上,不报告可识别个人的信息,因此获得了批准。在数据收集过程中,各医院均按照各自的政策严格执行病例记录的访问和存储流程。

结果

过程和描述性统计

鉴于审查病例记录的数量受研究者可用时间和医院内部获取病例记录能力的限制,匹配病例对照研究的方法必须实用化。两家医院都没有电子病历,因此查阅了原始的硬拷贝病例记录。这一过程非常耗时。表1按病例/对照状态和总体情况报告了纳入受试者的特征。各造口类型的病例组(造口旁疝)和对照组(无造口旁疝)数量并非完全相等。病例组与对照组的患者特征略有不同,病例组年龄稍大(中位年龄:病例组70.37岁 vs. 对照组66.11岁)、男性比例更高(病例组64.6% vs. 对照组52.9%)、平均体重较高(病例组87.5 kg vs. 对照组75.2 kg)。 两组患者接受造口治疗护士随访的比例均为100%,患者在发生造口旁疝前接受造口旁疝特定教育的比例相似(病例组39.6% vs. 对照组39.2%)。

两家研究中心的患者特征相似(见表1)。

表1.按病例/对照状态和总体情况划分的受试者特征。

潜在风险因素

表2报告了所有风险因素的单变量分析结果。大多数因素与造口旁疝发生风险之间没有关联性的证据;但有证据表明,较高的BMI(BMI每増加5 kg/m2,OR:1.74;95% CI:1.19-2.76)和较大的造口孔径(造口孔径每増加1 mm,OR:1.12;95% CI:1.02-1.24)会増加造口旁疝的风险。造口孔径是在患者首次STN审查(约术后第1-3天)时从患者的病例记录中识别的。手术后>30个月,发生造口旁疝的风险显著降低,优势比为0.003(95% CI:0.0004-0.02)。对于其他因素,有部分证据表明,多次腹部手术和术后感染会増加造口旁疝的风险,但由于样本量相对较少,估计优势比的置信区间过宽,难以得出有意义的结论。同样,有部分证据表明,活动量越大,患腹旁疝的风险越低,与活动水平“轻度”的患者相比,活动水平“重度”的患者患造口旁疝的几率在统计学上有显著下降。然而,只有少数受试者达到这种活动水平,限制了统计功效。

表2.所有风险因素的单变量分析结果。

在某些情况下,由于样本量较少,无法对潜在的风险因素进行分析;例如,患有腹水的受试者仅有一例,患有腹主动脉瘤的受试者仅有两例。置于直肠肌外的造口未记录实例。对于大多数受试者,无法从病历中确定造口是否位于腹直肌鞘内,因为在术前或术后均未明确记录。虽然无造口旁疝的造口患者中支撑衣使用比例明显较高,但这种关系的证据并不具有统计学意义。这可能是由于数据缺失比例较大(尤其是在对照组中),降低了检测关系性质的能力。

按造口类型进行的亚组分析

亚组分析并未发现任何表明不同类型的造口在潜在风险因素与发生造口旁疝之间存在差异的证据。但是,需要注意的是,这并不意味着不存在差异,因为在许多情况下,按造口类型细分后的数量太少,分析起来并不合理。

讨论

本研究旨在识别与造口旁疝形成关联最强的风险因素。预计研究结果将有助于完善当前的风险评估工具,并为其他临床医生和造口术研究者提供一个可复制和收集更多关于造口旁疝风险证据的方案。

完成病例记录审查

虽然病例记录审查流程在方法部分已有概述,但鉴于邀请其他学者复制研究,还需强调一些额外问题。审查过程中发现,许多患者的医疗史较长,每位患者都有若干(三至六份)病例记录档案需要审查,这种情况并不罕见,但在分配每例患者审查时间时未被充分考虑。病例记录中提供的信息质量参差不齐;虽然审查人员能够获取比预期更精确的体重指数和造口孔径尺寸信息,但关于造口位置的记录却不甚详尽。此外,仅在患者出现造口旁疝时,才会提供与患者讨论预防造口旁疝和使用支撑衣的记录,这导致了确认偏倚;因此,所报告的有关支撑衣使用的结果可能无法真实反映与造口旁疝的关系。

在审查过程中,两项风险因素的记录方式得到了加强。根据英国风险评估工具12,将肥胖(BMI>30)和造口孔径大于35 mm作为増加风险的因素。然而,病例记录中的文件允许将这些变量作为连续变量进行记录。具体来说,病例记录包括首次STN审查手术后审查时记录的确切孔径尺寸以及患者的身高和体重,以便审查员计算具体的体重指数。这是这项研究的优势所在,因为将孔径和体重指数作为连续变量进行报告可以提高统计功效,并计算出具体的优势比,从而更细致地了解体重指数和孔径尺寸与造口旁疝之间的关系。

BMI

本病例审查的结果表明,BMI较高或造口孔径较大的患者更易发生造口旁疝。具体而言,BMI每増加

5 kg/m2,患造口旁疝的几率就増加74%。这是一个特别重要的发现,尤其对于位于社会经济地位较低地区的公立医院,这些研究群体的体重指数通常高于平均水平。社会经济地位与肥胖之间存在联系。16

手术相关因素

研究还发现一些证据,表明多次腹部手术和术后感染的患者患造口旁疝的风险会増加,但具有这些风险因素的患者人数较少,影响了确定风险的统计功效。虽然先前的文献4,10,18,19,20,21表明一些手术相关因素(腹直肌、穿刺造口;横结肠造口术)和腹水会増加造口旁疝的风险,22但由于数据不足(即记录的具有这些特征的病例记录数量不足以计算具有足够功效的优势比),无法对这些潜在风险因素进行研究。此外,孔径尺寸每増加1 mm,造口旁疝风险就会増加12%。这与之前的文献报道一致,即孔径尺寸每増加1 mm,发生造口旁疝的风险就会増加10%。8此外,手术后30个月内最有可能出现造口旁疝。

吸烟

有趣的是,尽管既往文献表明吸烟是造口旁疝的一个风险因素,12但在本项研究中没有发现吸烟与造口旁疝之间存在关系的证据。这一点令人惊讶,考虑到吸烟者容易咳嗽,腹内压増加,导致腹部受力,理论上可能促成造口旁疝的形成。22总体而言,吸烟者的术后效果较差是众所周知的,这是因为全身的氧气和营养物质流动减少,延迟了伤口愈合。24有迹象表明,尼古丁的使用可能会抑制细胞修复,但这并不是造口旁疝的研究重点。17

化疗和放疗

没有证据表明手术后一年内的化疗和放疗与因治疗导致肌肉变弱而引发的造口旁疝之间存在联系。不过,以往的研究表明,26这两者之间存在联系。最近的研究可能由于样本量较小而没有发现影响,因此,应对此进行进一步调查。

总体而言,本研究的重要发现与之前的许多文献8,17,20,22相吻合,这保证了其在澳大利亚环境中的相关性,并促使有必要澄清其他潜在的重要因素,这些因素可能需要通过更多的案例记录来进一步研究。

研究局限性

本研究存在若干局限性,需予以考虑。首先,尽管考虑到研究的临床背景(繁忙的大都市医院,病例记录未数字化),务实的设计是必要的,但这确实使研究在检测某些因素的潜在风险时功效不足,特别是在合并症和额外治疗(如化疗或放疗)方面。未来研究可考虑通过多中心设计,对造口旁疝风险因素进行长期跟踪,确保收集功效足够的样本量前瞻性数据。

各医院在文档记录、评估及应对措施上遵循各自的规程。例如,某家医院针对体重指数偏低、体重无意中明显下降或食欲不佳的患者设有路径,指导员工联系营养辅助人员或营养师进行评估;而另一家医院则雇佣营养师,负责对患者进行全面评估,包括常规血液检查(如铁、镁水平),而不论其BMI如何。这种方案上的差异可能会对数据产生影响。

重物搬运风险因素的评估很成问题,因为病例记录中记录的数据很少,而且现有的记录往往模棱两可。考虑到该问题的主观性,这一现象并不意外。但这也意味着无法充分评估职业或休闲活动中重物搬运作为风险因素的作用。

随着时间的推移,各家医院的实践操作也在变化。例如,在一家医院的病例记录中,2021年之前的病例一般很少提及造口旁疝教育,但2021年之后的病例则一直有这方面的记录,这同样会影响所收集数据的质量。

最后,报告对造口的测量是从实用的角度出发的,因为对于术后何时测量造口以确定造口旁疝形成的风险还没有达成共识。据了解,术后造口的尺寸和形状会发生变化,通常在术后6至8周达到稳定尺寸。患者发生造口旁疝时造口尺寸和形状亦可能改变。25在两家医院的临床观察中,有患者在术后6周甚至之前发生造口旁疝。因此,为了保持一致性,决定在术后首次复查时进行测量。这解释了为何超过

35 mm的造口较多。最佳测量时机作为风险因素理解的探讨,将是未来研究的方向。

尽管本研究采用匹配病例对照设计提高了数据代表性的可能性,但上述问题意味着研究结果可能难以广泛推广至所有造口患者。

结论

本研究是澳大利亚首例综合了以往与造口旁疝风险有关的研究结果,并对病例进行回顾性审查以细化这些风险因素。由于造口旁疝通常会损害造口人士的生活质量,5必须继续了解潜在的风险因素,以便更好地进行预防管理。通过阐述本研究过程,我们期望能为临床医生和研究人员今后在其他医疗机构的研究提供指导,以加强重要风险因素的必要证据。

高体重指数、术后感染、多次手术、造口直径过宽、手术后时间少于30个月等因素均増加了造口旁疝的风险,而其他因素则没有达到显著性水平,这可能是由于样本量不足。

研究团队发现了许多信息缺失的问题,尤其是与患者因素有关的信息,如重物搬运和其他生活方式因素。建议引入在其他领域使用的活动记录工具(如代谢当量任务15)和重物搬运评估工具(职业名称词典23),并将其整合进造口治疗护士的评估流程中。

致谢

感谢南澳大利亚两家医院(阿徳莱徳北部地方卫生网络和圣安徳鲁斯医院)的护理部主任和执行护理主任以及临床记录科对本项目的协助和支持。

同时,我们也感谢英国造口护理护士协会(ASCN UK)开发的风险评估工具,启发我们在澳大利亚开展一系列研究。

利益冲突声明

作者声明无利益冲突。

伦理声明

本研究已获得中央阿徳莱徳地方健康网络人类研究伦理委员会H-2020-231:圣安徳鲁斯医院(编号138)和阿徳莱徳大学人类研究伦理委员会(编号16705)的批准。

资助

本研究工作获得了阿徳莱徳大学健康与医学科学学院的支持。

Author(s)

Lynette Cusack*

PhD

University of Adelaide, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,

Northern Adelaide Local Health Network SA Health,

Lyell McEwin and Modbury Hospitals, Adelaide, Australia

Email lynette.cusack@adelaide.edu.au

Fiona Bolton

BNurs

St Andrews Hospital, Adelaide, Australia

Kelly Vickers

BNurs

Northern Adelaide Local Health Network SA Health,

Lyell McEwin and Modbury Hospitals, Adelaide, Australia

Amelia Winter

BPsychSci (Hons)

University of Adelaide, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,

Adelaide, Australia

Jennie Louise

PhD Biostatistics

Biostatistics Unit, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, Australia

Leigh Rushworth

MAdvClinPhysio (cardiorespiratory)

University of Adelaide, School of Allied Health Science and Practice, Adelaide, Australia

Tammy Page

PhD

University of Adelaide, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,

St Andrews Hospital, Adelaide, Australia

Amy Salter

PhD Biostatistics

University of Adelaide, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,

Adelaide, Australia

* Corresponding author

References

- United Ostomy Associations of America. Living with an Ostomy: FAQs 2022. https://www.ostomy.org/living-with-an-ostomy/

- Malik T, Lee MJ, Harikrishnan AB. The incidence of stoma related morbidity: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2018;100(7):501–8.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. About the Stoma Appliance Scheme 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/stoma-appliance-scheme/about-the-stoma-appliance-scheme.

- Antoniou SA, Agresta F, Garcia Alamino JM, Berger D, Berrevoet F et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on prevention and treatment of parastomal hernias. Hernia. 2018;22:183–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1697-5

- van Dijk SM, Timmermans L, Deerenberg E, Lamme B, Kleinrensink G-J, Jeekel J, et al. Parastomal hernia: Impact on quality of life? World Journal of Surgery. 2015;39(10):2595–2601.

- Claessens I, Probert R, Tielemans C, Steen A, Nilsson C, Andersen BD, et al. The ostomy life study: the everyday challenges faced by people living with a stoma in a snapshot. Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2015;13(5):18–25.

- van Ramshorst GH, Eker HH, Hop WCJ, Jeekel J, Lange JF. Impact of incisional hernia on health-related quality of life and body image: a prospective cohort study. The American Journal of Surgery. 2012;204(2):144–150.

- Zelga P, Kluska P, Zelga M, Piasecka-Zelga J, Dziki A. Patient-related factors associated with stoma and peristomal complications following fecal ostomy surgery: a scoping review. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 2021;48(5):415–430.

- Sohn YJ, Moon SM, Shin US, Jee SH. Incidence and risk factors of parastomal hernia. Journal of the Korean Society of Coloproctology. 2012;28(5):241–246.

- Shiraishi T, Nishizawa Y, Ikeda K, Tsukada Y, Sasaki T, Ito M. Risk factors for parastomal hernia of loop stoma and relationships with other stoma complications in laparoscopic surgery era. BMC surgery. 2020;20(1):141 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00802-y

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of obser-vational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61(4):344–349.

- Association of Stoma Care Nurses United Kingdom. Stoma care national guidelines: parastomal hernia prevention. 2016. https://ascnuk.com/_userfiles/pages/files/national_guidelines.pdf Accessed 6 June 2023.

- Perrin A. Vice Chairpersons Report 2023. Association of Stoma Care Nurses United Kingdom. 2023. https://ascnuk.com/_userfiles/pages//files/committeeroles/report//vice_chair_persons_report_2024.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2024.

- Cusack L, Salter A, Vickers K, Bolton F, Winter A, Rushworth L. Perceptions and experience on the use of support garments to prevent parastomal hernias: a national survey of Australian stomal therapy nurses. Journal of Stomal Therapy Australia. 2022;42(4):18–25.

- Winter A, Cusack L, Bolton F, Vickers K, Rushworth L, Salter A. Perceptions and attitudes of ostomates towards support garments for prevention and treatment of parastomal hernia: A qualitative study. Journal of Stomal Therapy Australia. 2022;42(3):19–24.

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498-S516.

- Anekwe CV, Jarrell AR, Townsend MJ, Gaudier GI, Hiserodt JM, Stanford FC. Socioeconomics of obesity. Current obesity reports. 2020;9(3):272–279.

- McGrath A, Porrett T, Heyman B. Parastomal hernia: an exploration of the risk factors and the implications. British Journal of Nursing. 2006;15(6):317–321.

- Martin L, Foster G. Parastomal hernia. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1996;78(2):81–84.

- Aquina CT, Iannuzzi JC, Probst CP, Kelly KN, Noyes K, et al. Parastomal hernia: A growing problem with new solutions. Digestive Surgery. 2014;31:366–376. DOI: 10.1159/000369279

- Tivenius M, Nasvall P, Sandblom G. Parastomal hernias causing symptoms or requiring surgical repair after colorectal cancer surgery—a national population-based cohort study. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2019;34:1267–1272 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03292-4

- Manole TE, Daniel I, Alexandria B, Dan PN, Andronic O. Risk factors for the development of parastomal hernia: a narrative review. Saudi Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences 11(3). 2023 July-September; 11(3):187–192. https:/doi 10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_235_22

- Bower C, Roth JS. Economics of abdominal wall reconstruction. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2013;93(5):1241–1253.

- Dazhen L, Long Z, Changhai Y. The effect of preoperative smoking and smoke cessation on wound healing and infection in post-surgery subjects: A meta-analysis. Int Wound J.2022;19:2101–2106 DOI: 10.1111/iwj.13815

- Osborne W, North J, Williams J. Using a risk assessment tool for parastomal hernia prevention. British Journal of Nursing. 2018; 27(5):15–19. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2018.27.5.S15