Volume 39 Number 4

Comparing fluid handling and microclimate conditions under superabsorbent polymer and superabsorbent foam dressings over an artificial wound

Evan Call, Craig Oberg, Iris Streit and Laurie M Rappl

Keywords Exudate, microclimate, wound, superabsorbent, dressing

For referencing Call E et al. Comparing fluid handling and microclimate conditions under superabsorbent polymer and superabsorbent foam dressings over an artificial wound. WCET® Journal 2019; 39(4):11-23

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.4.11-23

Abstract

Introduction Superabsorbent foam (SAF) and superabsorbent polymer (SAP) dressings are compared on their abilities to handle moisture exuding from an artificial wound and to affect the microclimate beneath the dressings by measuring: the amount of moisture absorbed; the amount of moisture evaporated through the outer layer; the humidity, both beneath and outside the dressing and the difference between the two; and the temperature, both beneath and outside the dressing and the difference between the two.

Method A thermodynamic indenter was used in a laboratory setting to deliver a steady flow of moisture vapour across a standard wound size to each dressing under the weight of the indenter. Sensors recorded the humidity and temperature inside and outside each dressing over 3 hours and 16 minutes with a 45-second complete unweighting of the dressing at the 3- hour mark to simulate a patient weight shift. Dressings were weighed at test end to determine moisture absorbed and moisture evaporated.

Results There were no significant differences between the SAF and the SAP dressing groups in moisture absorption nor evaporation, nor in humidity nor temperature inside versus outside the dressings.

Conclusion It can therefore be determined that SAF and SAP dressings appear to be equally competent in maintaining a warm and moist microclimate in the wound bed. It should also be noted that these dressings do not dry the wound bed as the term superabsorbent may imply.

Introduction

Wound dressings are selected to manage moisture during wound healing for three reasons: to absorb exudate; to maintain an appropriate microclimate in the wound bed; and to protect the periwound from damage due to maceration from excessive moisture. Broad categories of absorptive technologies are foams, hydrocolloids, calcium alginates, hydrofibres, and moisture-binding polymers1,2. More complex superabsorbent foam (SAF) and superabsorbent polymer (SAP) dressings have been developed recently that claim to go beyond earlier dressings in managing wound moisture; however, these have been untested in comparison to each other. In addition, the term superabsorbent raises questions as to the possibility of over-absorption and therefore drying of the wound bed and inhibition of wound healing.

Exudate management

Since Winters published his pivotal work in 1963, moist wound healing has become accepted as best practice2,3. Cytokines and growth factors require moisture to diffuse throughout the wound bed to stimulate healing via wound closure and re-epithelialisation4. Maintaining the proper moisture level in a wound bed prevents desiccation which allows epithelial cells to migrate freely across the wound surface. Moist wounds granulate, epithelialise and heal two to three times faster than dry wounds5.

Exudate occurs naturally as a part of the wound healing process and keeps the wound bed moist to stimulate closure in most wounds. Some types of wounds are naturally more exudative than others, especially venous wounds, large pressure ulcers, and burns. Chronic wounds are highly exudative due to a sustained state of inflammation and disruption of normal cellular activity. Chronic wound exudate differs markedly from acute wound exudate, consisting of high levels of protein-degrading enzymes, matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), neutrophils and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Exuding wounds therefore require absorptive dressings whose capabilities match the flow of exudate to maintain an optimum moisture level at the wound bed. As these wounds begin to granulate, exudate decreases and dressing needs move from absorption to protection as a primary characteristic2.

The amount of exudate or moisture coming from a wound is commonly documented in a patient’s records with subjective descriptors such mild, moderate, severe and excessive rather than objective measurements. Several validated scales have been proposed for documenting exudate amount, including the Wound Exudate Score, the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool and the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH) tool. Each scale provides a descriptor for each level on that scale. A summary and comparison of the available tools and their descriptors can be found in Wound exudate: effective assessment and management, a consensus document on exudate published by the World Union of Wound Healing Societies in 20195.

Wound microclimate

The microclimate has been identified as a key factor in both wound prevention and healing. The microclimate is the combination of temperature and humidity, and sometimes airflow, in a local region as compared to the ambient or surrounding area6. A warm moist environment is conducive to wound healing. Dini et al.7 show wound healing is impaired at <33°C by a decrease in neutrophil, fibroblast and epithelial cell activity. This same study shows a correlation between improvements in the wound bed and wound bed temperatures between 33–35°C. In addition, Salvo et al.8 report two studies showing that temperatures in the range of 36–38°C appear to promote wound healing.

Dressings, however, resist moisture escape, increasing heat and humidity levels beneath them. Advanced absorptive dressings can therefore affect the microclimate of the wound bed by drawing excessive moisture off the wound surface and maintaining warmth and humidity while dissipating excess heat and moisture through a vapour-permeable outer layer. Occlusive dressings do not have these functions.

Periwound skin

Excessive moisture on intact periwound skin weakens the dermis and epidermis by interrupting the arrangement of lipids in the stratum corneum (SC) and the linkages between epidermal cells1. The resulting increase in permeability makes the periwound more susceptible to invasion by contaminants and to the compounding effect of friction and shear. The term moisture-associated skin damage (MASD) refers globally to epidermal injuries resulting from exposure of the skin to moisture (for example perspiration) and irritants (for example urine, stool, ostomy effluent, wound exudate)1. One of the four clinical categories of MASD is periwound skin damage. Compounding the bond-weakening effects of moisture, enzymes in wound exudate that normally degrade contaminants in the wound also degrade proteins in intact skin. The resulting damage can cause pain, an increase in wound size, and decreased keratinocyte migration from the wound edges, therefore impairing wound closure9. As such, clinicians should choose dressings that prevent exudate from coming in contact with the periwound by locking in absorbed exudate. Ideally, the absorptive pad of a dressing should also be sized to that of the open wound bed rather than extending to the periwound.

Dressing constructions

Dressings are a dynamic primary method of either resisting moisture loss from a dry wound bed or absorbing excessive moisture from a wet wound bed while keeping the periwound free from excessive moisture.

Basic dressings such as pads made from cotton gauze or absorbents made from cellulose fibres or foams cover the wound bed and protect it from trauma and from the environment as well as simply absorbing moisture. Island dressings include an adherent border around the absorbent area. Dressings with increased capacities and enhanced features are used to treat highly exudative wounds that can overwhelm basic dressings.

SAP dressings are comprised of multiple layers in order to accommodate more highly exudative wounds by both absorption and evaporation of wound moisture. The superabsorbent core is often a mixture of cellulose and hydrophilic polymers wrapped in a cellulose tissue and/or a non-woven material. Most SAP dressings have an outer low-friction vapour-permeable polyurethane layer that allows moisture to transpire, thereby drawing more exudate from the wound and allowing a longer wear time. Polyurethane with a moisture vapour transmission rate of more than 35g/m2/hr is correlated with faster wound healing under occlusive dressings10. The sum of the fluid absorbed into the dressing and the fluid transpired through the dressing is called the fluid-handling capacity of the dressing, as defined by the European Committee for Standardization11.

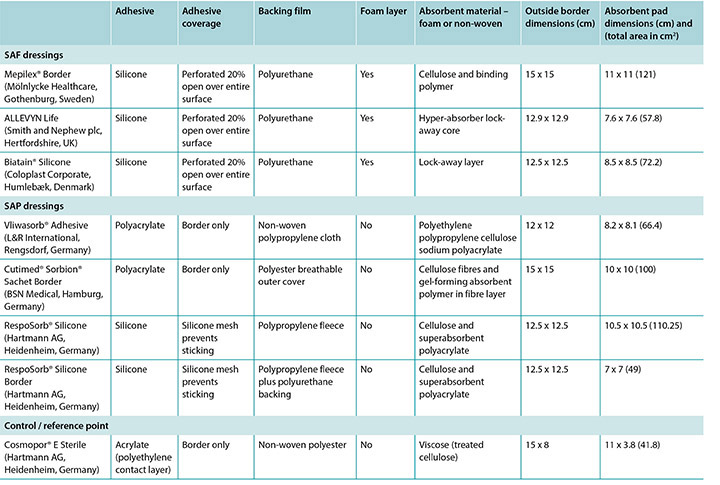

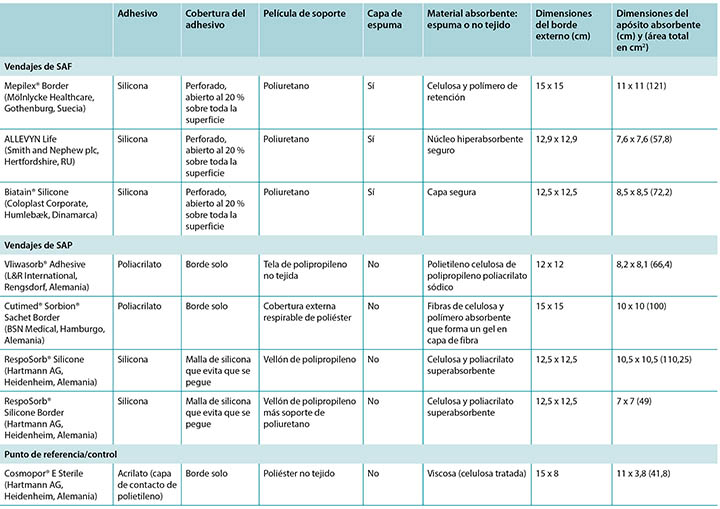

Some SAP dressings have acrylic adhesive on a border around the absorbent island so no additional taping nor fixation of such dressing is required. Some of these dressings also feature a silicone layer across the wound surface of the dressing to minimise trauma to the wound bed – see Table 1 for an examination of the similarities and differences among a representative group of these dressings.

Table 1. Size and construction of representative test dressings.

It should also be noted that the term superabsorbent can imply that a dressing can draw too much moisture from a wound and dry it out, thereby counteracting moist wound healing. One subgroup of SAP dressings – SAF dressings – are constructed in a manner similar to the SAP dressings and include an extra foam layer between the silicone and the polymer that is purported to prevent drying of the wound bed and to optimise the microenvironment of the wound bed (Table 1). Furthermore, removing pressure from a wound and dressing through a pressure release manoeuvre or a repositioning of the patient may affect moisture evaporation and heat dissipation and enhance the function of the dressing, increasing wear time.

There are few published studies comparing the effects of different dressings on similar wound types in patient use, nor ones examining the claims made by manufacturers in reference to benefits of their products in affecting the wound bed or the microclimate. Clinical research comparing dressings is very difficult to accomplish due to the many variables affecting wound healing and the impossible task of standardising patients. However, well-designed laboratory research can standardise the wound size and the exudate amount so that test dressings can be compared to each other. This standardisation limits applicability of results to the highly variable clinic population, but can provide some evidence to give guidance as to the effectiveness of a dressing in controlling the physical properties of a wound to optimise wound healing.

Study purpose

This in vitro study compares dressings in the SAF and the SAP dressing categories described in Table 1. A basic non-polymer surgical dressing was included as a control or a reference point. The dressings were studied for their abilities to handle moisture exuding from an artificial wound by measuring the:

- Amount of moisture absorbed, reported as total grams per dressing and g/cm2.

- Amount of moisture evaporated through the outer layer, reported as total grams per dressing and g/cm2.

- Humidity, both inside the covered wound bed and at the outer layer and the difference between the two.

- Temperature, both inside the covered wound bed and at the outer layer and the difference between the two.

Additionally, the effect of a pressure release or patient repositioning on each of these parameters was measured.

It is important to note that previous work was reported as simply moisture per dressing12. For this study, due to the large variation in dressings mass and surface area, these values are reported in grams of moisture per cm2.

Method

This study was conducted by an independent laboratory that is a contributor to the development of standards for support surfaces, wheelchair cushions, dressings and other wound-related medical equipment. The laboratory had an ambient temperature of 23°C ±2°C and a relative humidity of 50% ±5% as specified in ISO 554-1976(E)13.

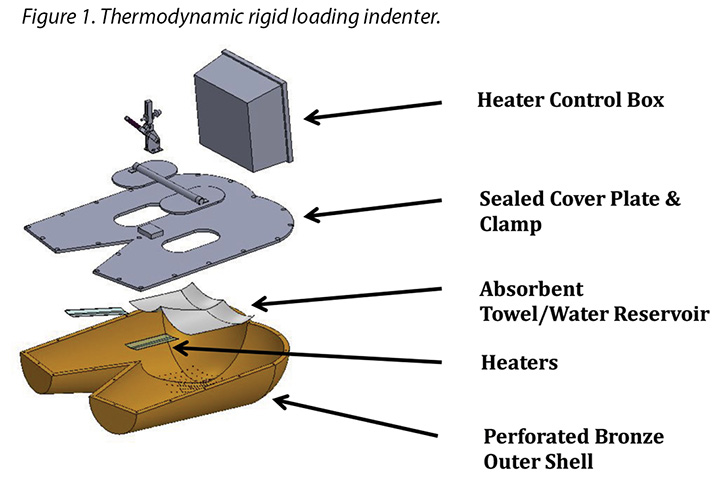

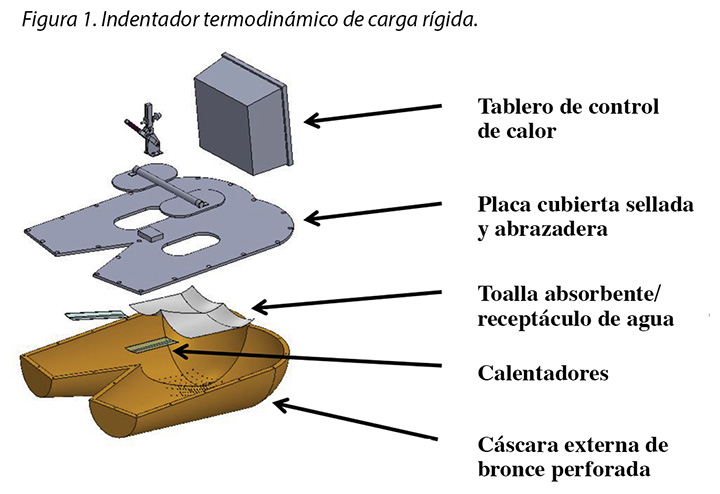

The human model was a bronze thermodynamic rigid cushion loading indenter first described by Ferguson-Pell et al.14 for use in testing wheelchair cushions. The model was developed by a group of researchers from the United Kingdom, Japan and the United States. Since 2009 it has become a standard piece of testing equipment for studying support surfaces, dressings and wheelchair cushions in the international wound care market15 (Figure 1).

The test indenter was compliant with the American National Standards for Support Surfaces16. The indenter is shaped according to the buttocks and upper thighs of a 50th percentile human male and has pre-drilled holes in the area of the sacrum and ischium. The indenter can be loaded with pre-measured amounts of water, heated and cooled, and weighted. Diffusion of the water through the pre-drilled holes simulates moisture loss through the skin. This indenter mimics the heating, cooling, sweating and drying, weighting and unweighting of the human sacral area. Resulting conditions at the indenter–surface interface are measured, and can be compared between products, as well as in steady-state and transient conditions.

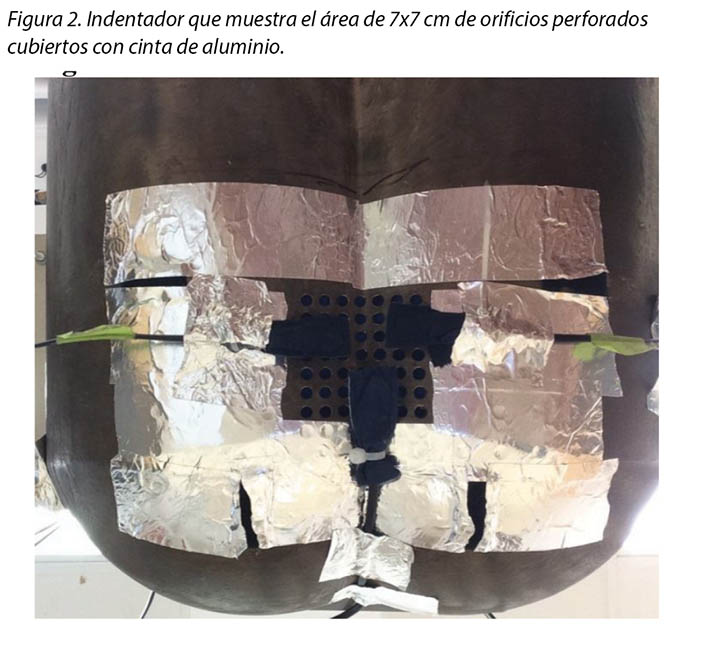

For this study the indenter was weighted with 64lbs ± 2.25lbs (just over 29kgs ± just over 1kg) which is the weight of this segment of the body for a 50th percentile male lying in bed supine. An artificial wound was created by covering all sweating pore holes not covered by the dressing pad; aluminised tape ensured no moisture evaporated outside the artificial wound area (Figure 2). This left an area of 7x7cm holes for moisture vapour; this was used for all dressings tested.

Challenging dressings under these conditions provides a scenario that is clinically relevant because foams and polymers are compressed and moisture vapour escape is reduced by the actual use conditions of the test14,15. For example, temperature and humidity sensors are high accuracy digital sensors manufactured by Sensirion AG (Staefa ZH, Switzerland) which are accurate to ±1.8% at 0–80% relative humidity and ±0.3°C at 20–50°C. The test support surface was an open-cell foam cushion 3x18x18” (7.6x45.7x45.7cm) covered with a breathable liquid moisture-resistant mattress cover by Dartex Coating US (Slaterville, RI) and positioned on a rigid mattress board.

Moisture and humidity were supplied by a weighed amount of distilled water soaked into EnduracoolTM Microfiber Cooling towels. This towel was chosen because the microfibre is a thermo-regulating technology with a moisture release rate compatible with previous published studies on LAL support surfaces17,18. In a laboratory setting, wound exudate is represented by distilled water. While the properties of each fluid differ markedly, the study is designed to demonstrate performance differences and this can be accomplished with a standard fluid. Previous publications characterising the moisture-handling capacity of dressings using this method provide a comparative baseline12.

The wound model used here is not a highly exudating model; it is a water vapour model. This model delivers a low level of moisture to the dressing surface over a period of time in a controlled manner so that a researcher can determine if the moisture is bound to the dressing or transpires through it. Test dressings were chosen from conveniently acquired and commonly utilised multilayer dressings in the European Union and in the United States. The representative dressings are listed in Table 1.

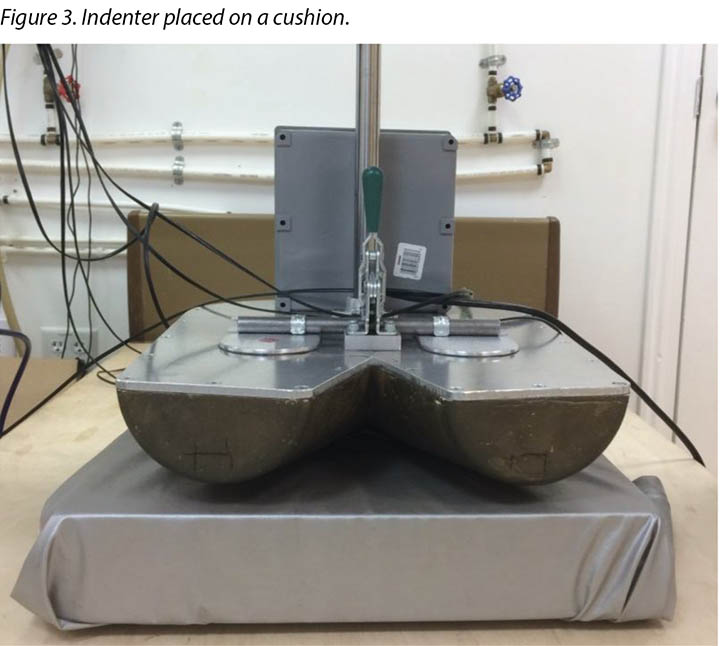

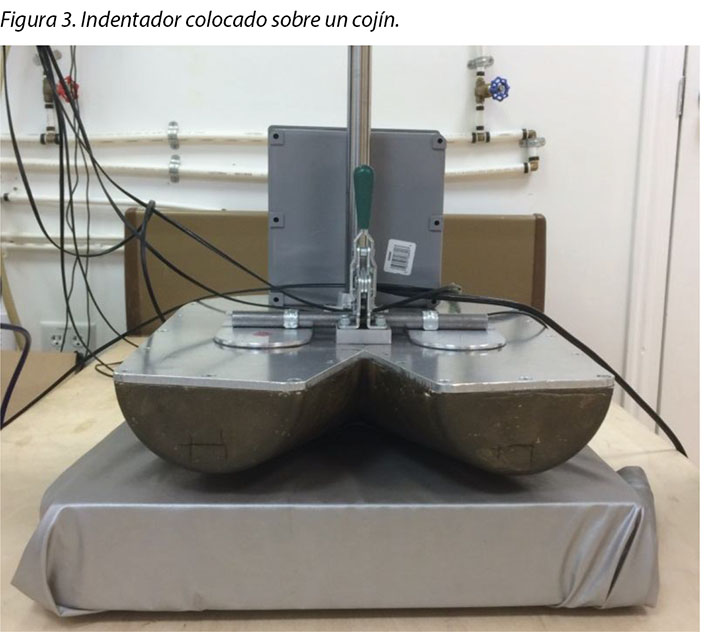

The indenter was suspended over the cushion by an H-frame which was positioned around the bed frame at about the midpoint of the bed frame. The cushion was centred under the indenter so that the ischial tuberosity area of the indenter was located 10–15cm from the rear edge of the cushion (Figure 3). The indenter was set to 37°C. The weights of two dry sets of EnduracoolTM towels were recorded, then 100±1g of distilled water was added to each towel set providing a potential for 200g to be delivered to the dressing. Each towel was folded in thirds and placed inside the indenter so that the towels covered all of the sweating pore holes. Heated weights were placed on top of the towels to facilitate moisture delivery.

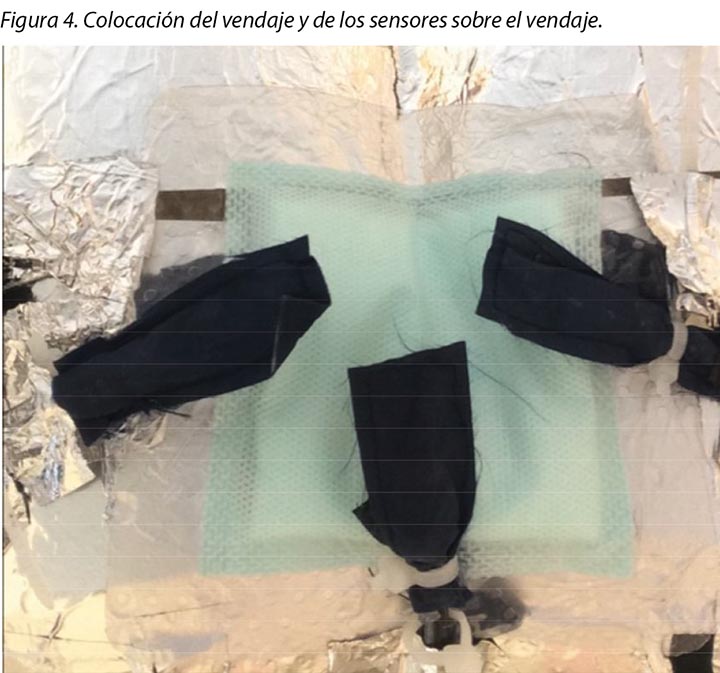

Three sensors were placed to sense moisture escaping from the artificial wound area (Figure 4). Sensor locations were modified to accommodate the size of each dressing. The dressing was centred over the open sweating pore holes and covered all three sensors. Sensors placed outside the dressing lined up with those under the dressing (Figure 4). The indenter was lowered so that it settled on the support surface and transferred the full load of 64lbs ± 2.25lbs (just over 29kgs ± just over 1kg) to the support surface. A seventh sensor was used to measure ambient temperature and humidity. An EK-H4 Viewer program was set to log data at 30-second intervals through the test period.

To simulate a pressure release or patient repositioning, the indenter was raised from the support surface for 45 seconds at 3 hours ± 6 minutes. Readings were taken five minutes before the lift, identified as 175 minutes in the results section, to provide an air gap between the indenter and the support surface. It was held fully suspended from the support surface for a total of 45 seconds ± 10 seconds, then lowered back onto the support surface fully loaded for an additional 15 minutes ± 1 minute. Final readings are reported as 196 minutes in results.

At the end of the test the indenter was raised and the towels were removed and weighed. The dressing was removed from the indenter and artificial wound, and its weight recorded. The weight of a dry paper towel was recorded, the towel was used to wipe all moisture remaining in the indenter, and the towel was weighed again.

Between trials the indenter was allowed to return to steady state before the next trial was initiated. Distilled water was added to return the towels and the water mass back to the total weight of the dry towels plus 200±1g of distilled water. Two cushions and two covers were used; these were switched between trials to allow full recovery. A total of three trials were done for each dressing. Three trials were also performed with the indenter hanging in the air for 3 hours and 16 minutes without a dressing applied to measure the moisture vapour output of the artificial wound.

The final weight of the towels plus the paper towel was subtracted from the starting weight of the towels to ascertain the total amount of distilled water delivered to the system. Moisture absorbed in the dressing pad was calculated by subtracting the dressing initial weight from the dressing’s final weight. The amount of water vapour produced from the system was calculated by subtracting the starting weight of the towels from the end weight of the towels and adding the moisture recovered from inside the indenter using the paper towel. The amount of moisture that evaporated the dressing was calculated by subtracting the amount of moisture trapped in the dressings from the amount of water vapour produced by the system. The 95% CI was calculated.

While the artificial wound size was constant throughout the study, the absorbent pads for the dressings varied from 41.8cm2 to 121cm2 (Table 1). As such, the total moisture absorbed and evaporated per dressing was calculated. Calculations for moisture absorbed and moisture evaporated were done on a per cm2 basis as well to account for the variability in dressing sizes and to more accurately compare dressing performance. The average difference in temperature and humidity between the outside or cushion surface of the dressing and the inside or patient side of the dressing at 175 minutes and over the full length of the test was calculated by averaging the difference between the value over the dressing and the value under the dressing for each data point.

Results

The aim of the study was four-fold, namely to measure: the amount of moisture absorbed; the amount of moisture evaporated through the outer layer; the humidity, both beneath and outside the dressing and the difference between the two; and the temperature, both beneath and outside the dressing and the difference between the two.

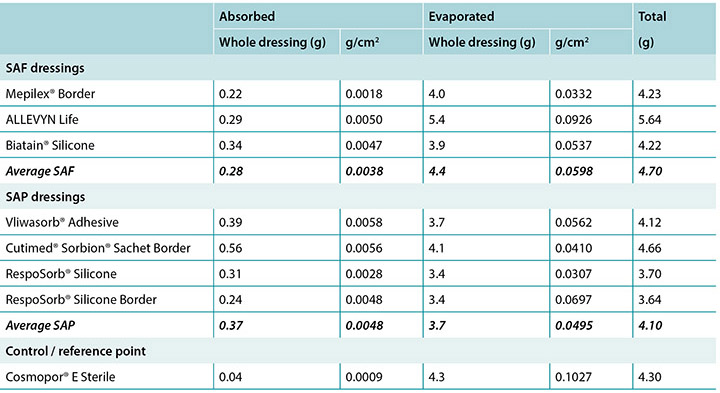

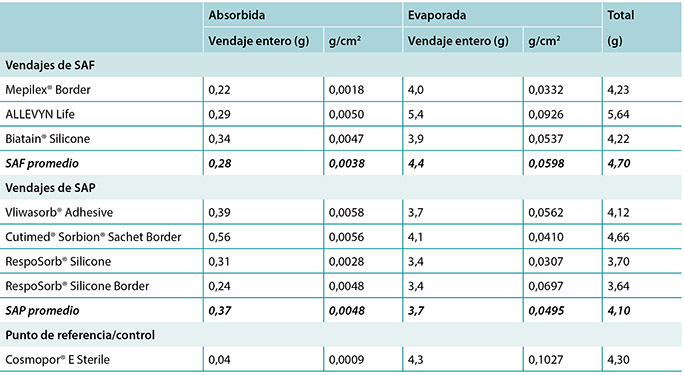

The amount of moisture each dressing absorbed is shown in Table 2. This shows the total moisture and the moisture absorbed in g/cm2 per dressing as well as showing the average. The range of the SAF dressing group was 0.22–0.34g. The range of the SAP dressing group was 0.24–0.39g if the one outlier at 0.56g is not considered. The reference dressing was the smallest in area and absorbed the least by far. The range for six of the seven study dressings was 0.22–0.39g.

Table 2. Moisture absorbed in absorptive pad and moisture evaporated per dressing in total g and g/cm2 and averages of SAF and SAP.

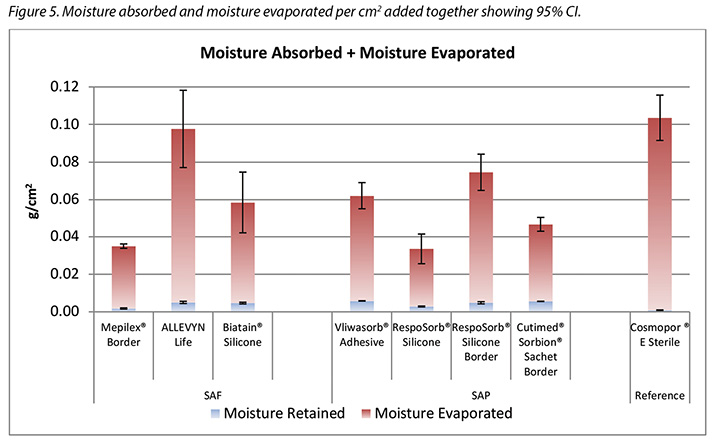

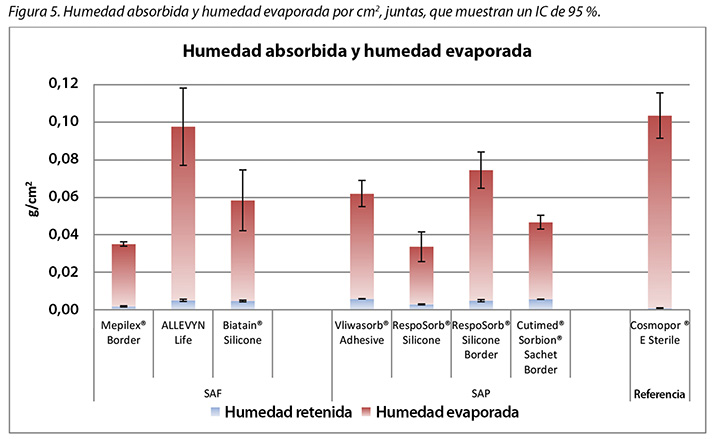

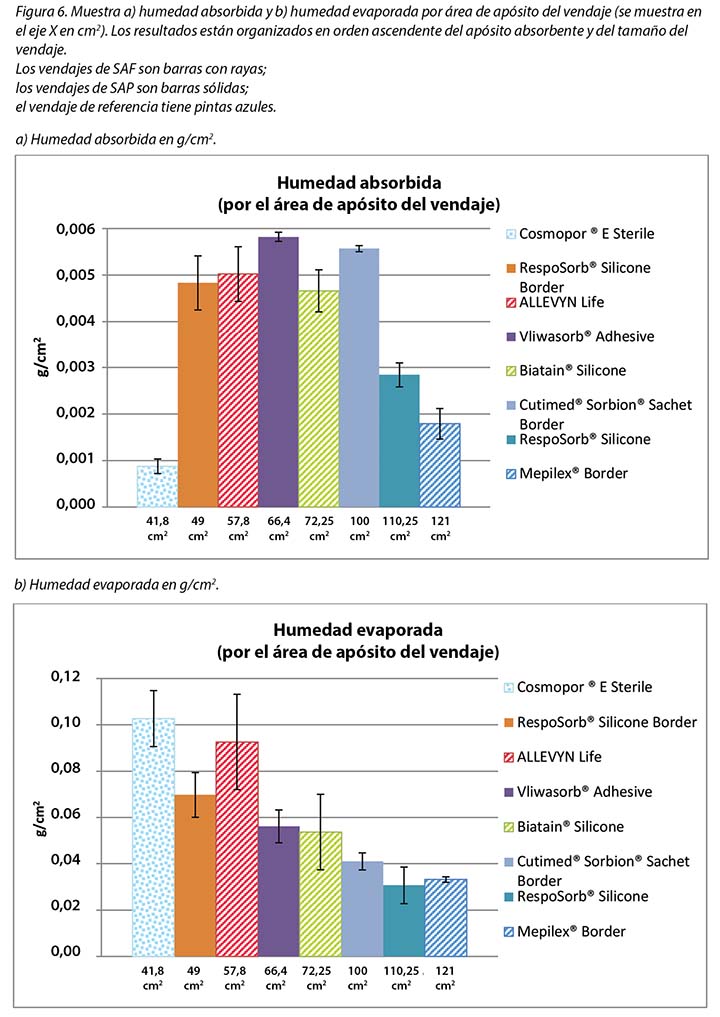

The amount of moisture evaporated (transpired or evaporated) through the outer polyurethane layer is also shown in Table 2 and in Figure 5. The range of the SAF dressing group was 3.9–5.4g, a difference of 1.5g, whereas the range of the SAP dressing group was 3.4–4.1g, a difference of just 0.7g. Indeed, six of the seven test dressings were within 0.7g of each other (range 3.4–4.1g). There was no significant difference among the dressings at a 95% CI.

In Table 2 it should be noted that the total amount of moisture delivered by the indenter was 5.9g. Adding together moisture absorbed and moisture evaporated shows that none of the dressings removed all of the moisture.

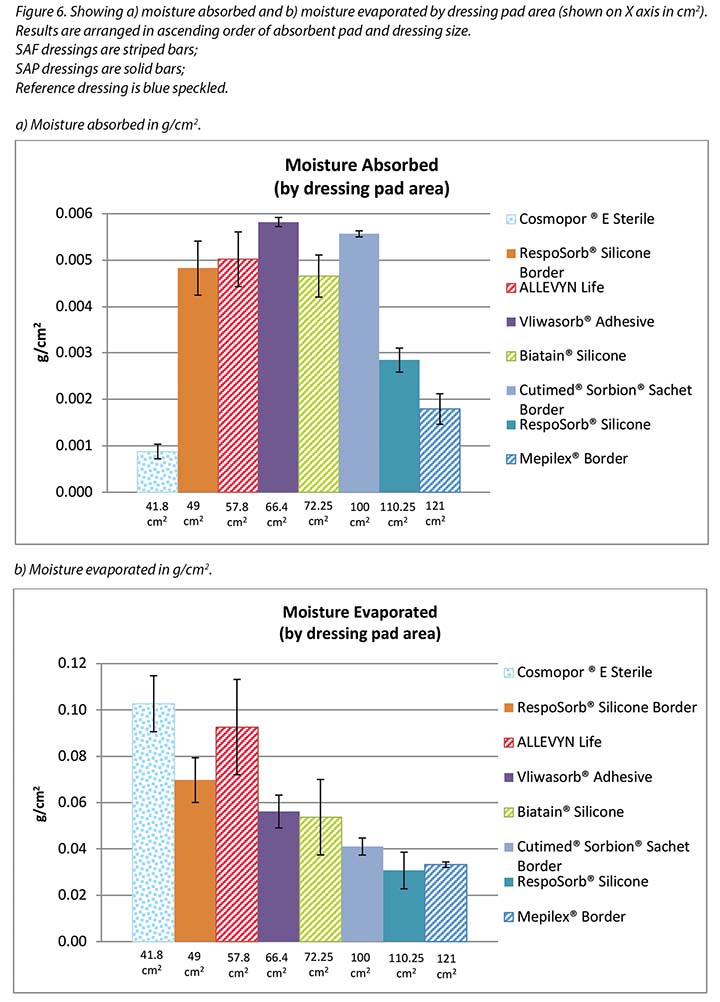

Figure 5 graphs the total amount of moisture absorbed and moisture evaporated in gcm2 for each dressing. Figures 6a and 6b graph the moisture absorbed and the moisture evaporated per cm2 arranged in order of size of the absorbent pad, from smallest to largest. As the dressing size increased, the amount of moisture absorbed and escaping per cm2 appears to decrease, making the larger pads appear to perform more poorly. However, larger dressings have more area over which to absorb and evaporate moisture, and this graph is not standardised for wound and dressing size.

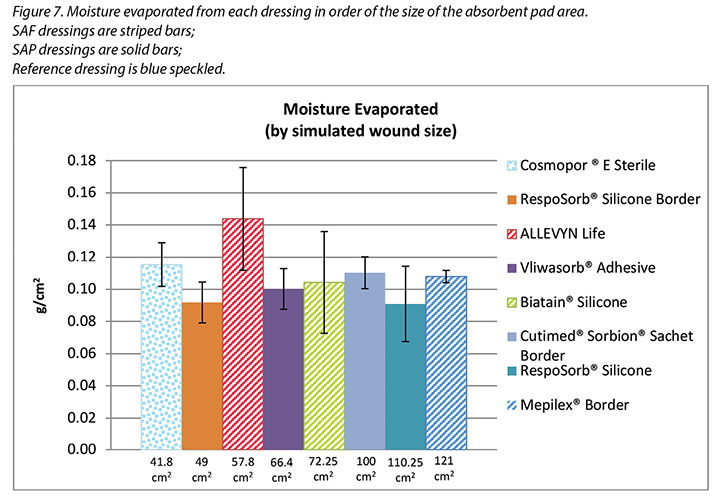

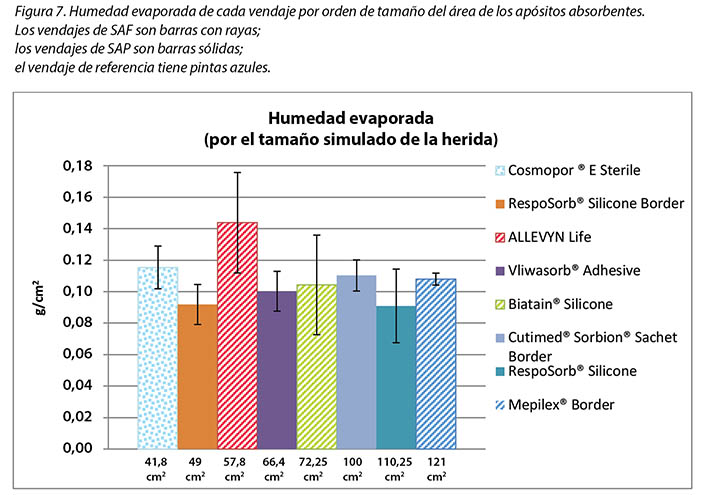

Figure 7 graphs the moisture evaporated per cm2 per wound area. That is, the dressings are compared by using both a standard wound size – the area of the exposed holes in the indenter – and a standard amount of vapour across a standard area. When compared in this way, all dressings manage approximately the same amount of moisture according to their absorbent area.

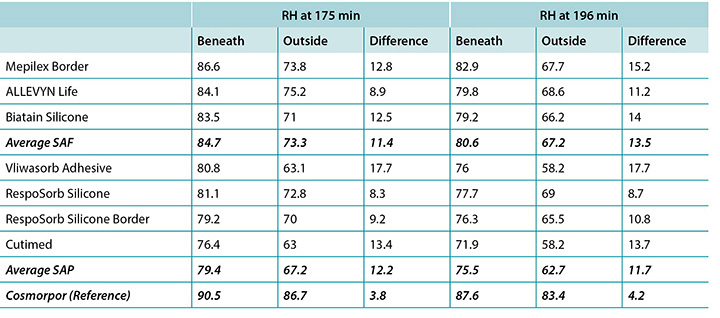

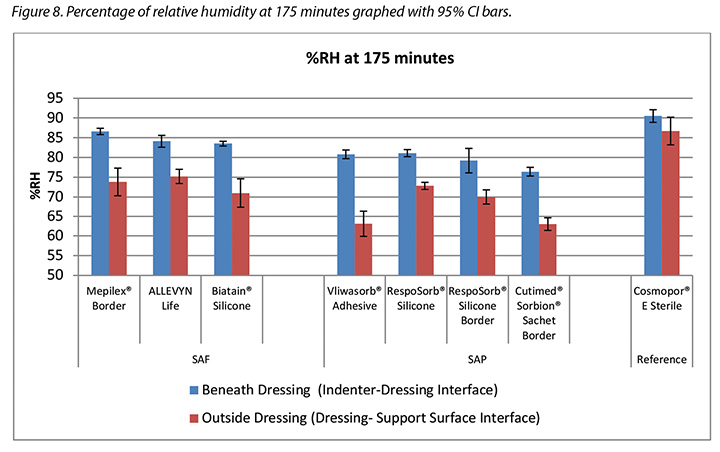

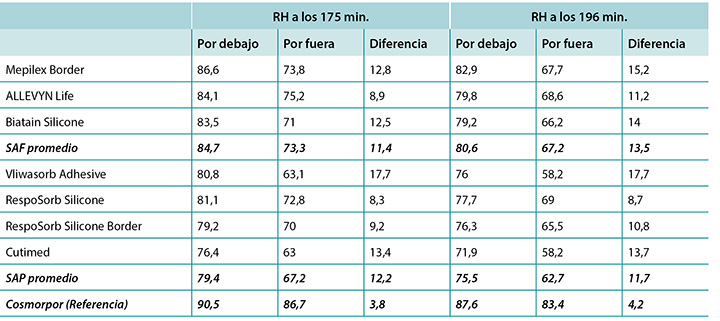

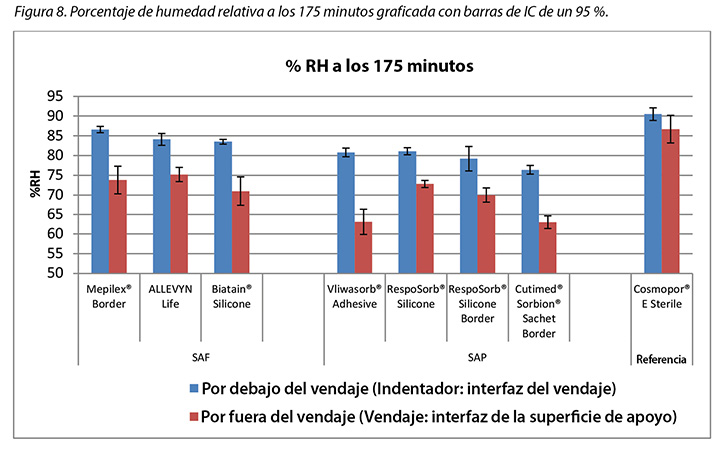

The humidity, both beneath and outside the dressing as well as the difference between the two, was also recorded. Table 3 shows the average percentage of relative humidity at 175 minutes (before pressure release) and at 196 minutes (after pressure had been reapplied for 15 minutes, at test end) inside and outside the dressings, and the difference between the inside and outside dressings, by dressing and by group. At 175 minutes all humidity readings outside the dressings were above ambient (50%), indicating active transpiration across the polyurethane backings. The SAF dressing group had a higher average humidity both inside and outside the dressing than the SAP dressing group, but the difference between the inside and the outside of the two groups was similar, 11.4 and 12.2% respectively. The reference dressing had much higher humidity both inside and outside the dressing, with a difference of only 3.8% (Table 3 and Figure 8). At 196 minutes the SAF dressing group had higher average humidities inside and outside the dressing than the SAP dressing group, but the differences between the inside and the outside were greater in the SAF dressing group. The reference dressing had a very small difference between the inside and the outside (Table 3). Looking at the error bars in Figure 8, there were no significant differences among the dressings at the 95% CI.

Table 3. Average percentage of relative humidity at 175 and 196 minutes.

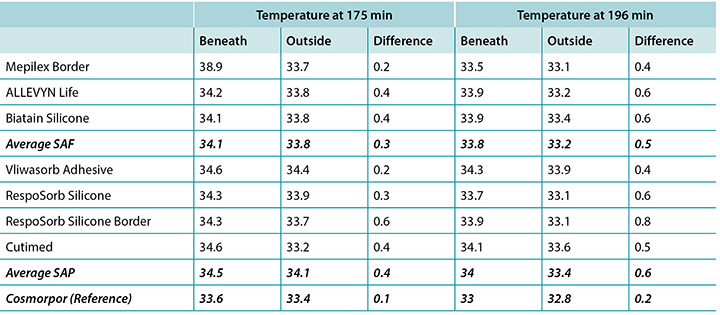

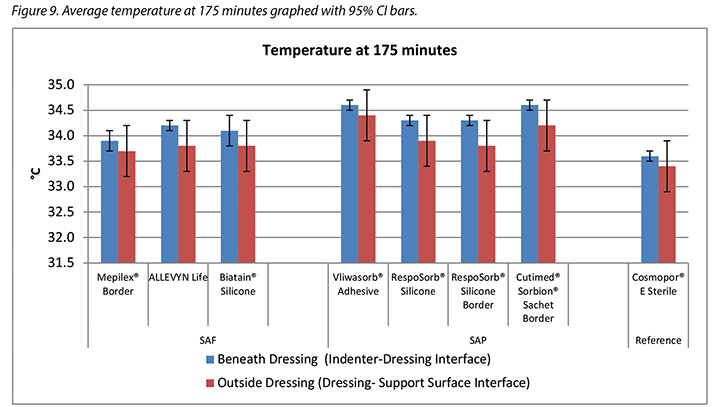

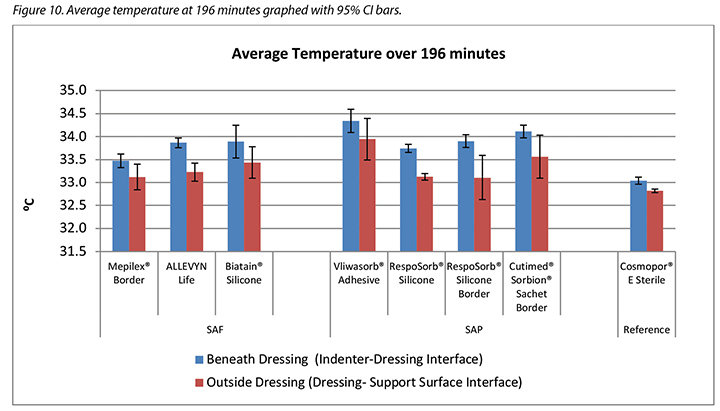

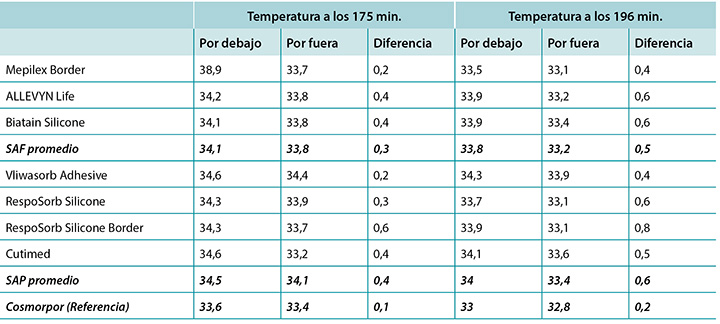

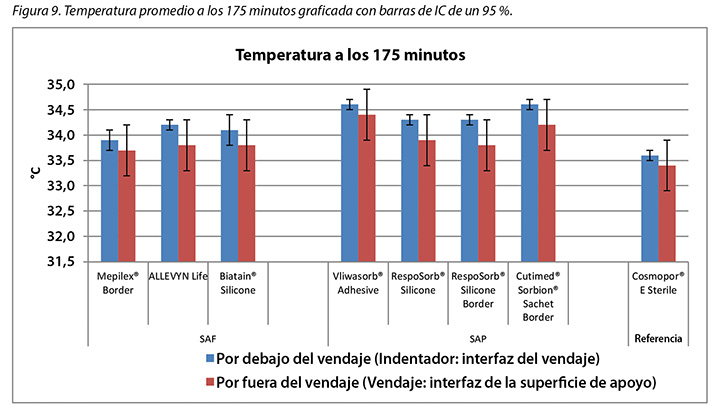

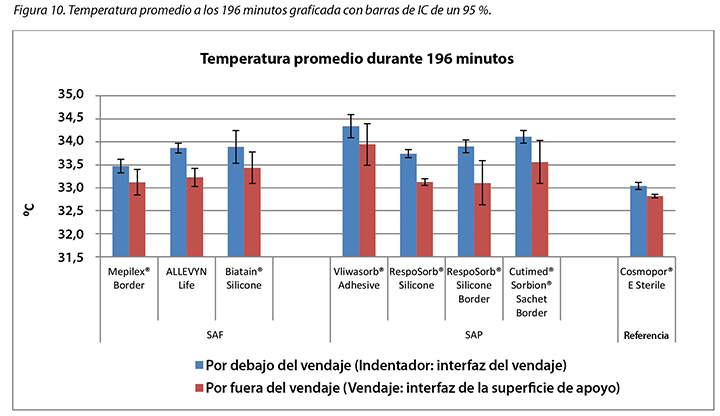

The temperature, both beneath and outside the dressing as well as the difference between the two, was also recorded. At 175 minutes, the average temperatures of the SAF dressing group, the SAP dressing group, and the reference dressing were within 0.9°C. The SAF and the SAP dressing groups had larger differences in temperature between the inside and the outside of the dressings than the reference dressing (Table 4 and Figure 9). At 196 minutes the average temperatures of the SAF and SAP dressings both inside and outside the dressings were within 0.2°C of each other. The reference dressing was only slightly below the two groups (Table 4 and Figure 10). The range of temperatures inside and outside the dressings at 196 minutes was 33.1–34.3°C. The range of temperature difference between the inside and the outside of the dressings was 0.4–0.8°C. The negative control had a temperature difference of only 0.2°C. There were no significant differences among the dressings at the 95% CI.

Table 4. Average temperature at 175 and 196 minutes.

Discussion

This study measures the relative performance of dressings in a laboratory setting by comparing results at specific time points and averaged across time. While the 3+ hour test period is a small segment of time compared to the length of time that a patient normally wears these types of dressings, the test gives an indication of how they may perform relative to each other over longer times.

This method tested how dressings handle moisture from a low steady exuding of vapour. When the integument is compromised in a stage 2, 3 or 4 wound, the regulation of moisture vapour escape is compromised as well, adding to the moisture that a dressing must handle. Total vapour can compromise the integument and must therefore also be considered when evaluating dressings6,19.

As expected, the more advanced SAF and SAP dressings outperformed the control/reference point basic island dressing in most categories.

Moisture absorbed and moisture evaporated

Both SAF and SAP dressing groups absorbed significantly more moisture in the pad than the reference dressing, indicating that their polymer materials absorb and lock in moisture and prevent it from migrating to the periwound or the wound bed. Six of the seven advanced dressings absorbed between 0.24–0.39g, with one outlier absorbing 0.56g. Dressings are expected to absorb enough to prevent maceration of the wound bed but not so much as to dry it. In order to dry a wound, a dressing would have to absorb and transpire all of the moisture provided to it. None of these dressings did, therefore the total of the moisture for each dressing in Table 2 does not equal the total moisture delivered by the indenter, 5.9g. It appears from these results that the SAF and SAP dressings are adept at absorption and will not dry a wound that exudes at the moderate level of the test fixture. The ALLEVYN Life comes closest to absorbing and transpiring all of the fluid supplied.

The same amount of moisture was delivered to all dressings. The smallest dressing had the least moisture absorbed and the most moisture which evaporated; this may be expected because the wound size was constant throughout, leaving the ratio of area of the artificial wound delivering the moisture to the area of the dressing that is available to transpire it dramatically greater for the larger dressings. Larger dressings are able to absorb and retain more, and the polymer locked in that moisture so that it could not – and did not – escape. Larger dressings can also spread and diffuse the moisture over a larger area.

The SAF dressing group, the SAP dressing group and the reference dressing were not significantly different in the amount of fluid that evaporated or transpired from the wound area at the 95% CI (Figure 6b). When moisture evaporated is graphed based on both moisture delivered and pad area in g/cm2, the advanced dressings are very similar (Figure 7). Various sizes of dressing can affect results. However, when results are shown in g/cm2 in order to compare various sized dressings, the differences are very small. This makes interpretation more difficult.

This test was performed consistent with other testing – some published and some unpublished – where striking differences in moisture handling between advanced dressings were shown6,12. This has inspired manufacturers to improve their products and the polymers and vapour-permeable backings used in the dressings, possibly resulting in more uniformity in dressing structures and the similarity in apparent handling capacities among the tested dressings.

Humidity and temperature

Specific temperature and humidity values defining the optimal microclimate conditions have not yet been determined by clinical nor laboratory research. Dressings are expected to keep the wound bed moderately warm and moist rather than too wet or too dry, too warm or too cool relative to the individual patient’s normal subdermal or dermal body conditions and to the external atmosphere. Higher humidity and moisture levels may negatively impact the wound environment just as they weaken intact skin1. The SC is in equilibrium hydration at ambient humidity of 40–60% but absorbs water at disproportionately increasing rates above 60%20–22. Wildnauer’s results show that relative humidity above 60% has the greatest influence in decreasing internal cohesive forces within the SC23.

At 175 minutes, all dressings were above 75% relative humidity beneath the dressing with a range of 83.5–86.6% for SAF dressings and 76.4–81.1% for the SAP dressings. It is reasonable to consider these values as moist. Dressings with higher inside humidities – the SAF dressing group and the reference dressing at 90.5% – may be cause for concern in potentially over-hydrating the wound bed or periwound. At 175 minutes, all dressings also had lower humidity readings outside the dressing than inside, as would be expected. All of the humidity levels outside the dressings were higher than ambient, indicating that the polyurethane backing does evaporate or transpire fluid. There was also a correlation between relative humidity beneath the dressing and moisture absorbed by the dressing pad. Lower moisture absorbed by the pad correlated with higher humidity beneath the dressing (Pearson’s correlation coefficient = –0.83).

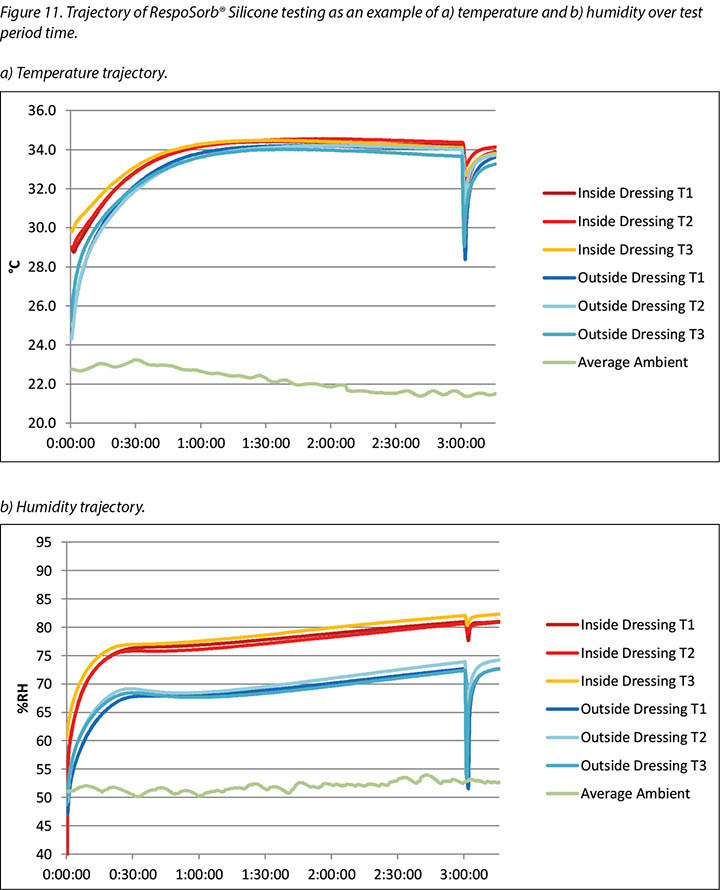

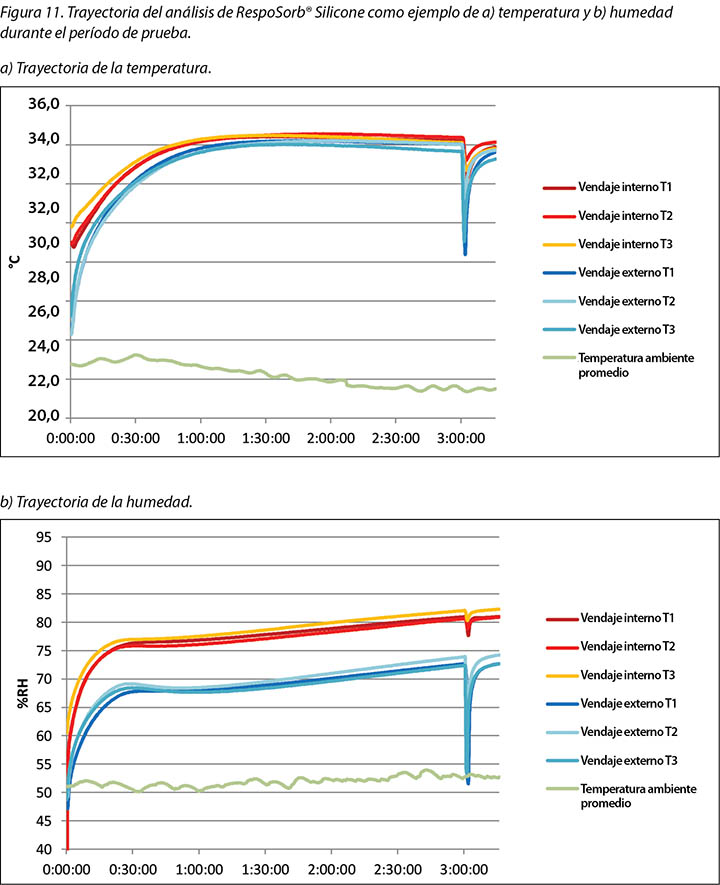

The complete release of pressure at 176 minutes suspended the indenter and the test dressing in air and allowed exchange of heat and moisture with the environment. Figure 11 shows the graphed results for one of the dressings, RespoSorb® Silicone, across the 196 minutes of the test. This is illustrative of a similar path seen for all dressings. Temperatures and humidities rose early in data collection, then temperatures eventually plateaued while humidities continued to rise. Both values dropped sharply when the indenter was lifted for the 45 second pressure release, then increased to or near pre-lift levels. It was impressive that a pressure release can have a rapid, measurable and significant affect on both heat and moisture which demonstrates the benefits of frequent position changes beyond addressing simply pressure and shear. Fifteen minutes after the pressure relief lift, at 196 minutes, all humidity levels were above 70%, with the reference dressing the highest at 87.6%. It appears that moisture vapour escapes more readily than it is trapped as, within 15 minutes of the lift, all values returned to the 175-minute levels.

Both dressing groups kept the wound bed relatively warm as indicated by lower temperatures outside the dressing than inside. This is conducive to wound healing as all were within the recommended 33–35°C range7. Yusuf et al.24 reported that a skin temperature difference of only 0.3°C predicted pressure ulceration. While this measurement is not in a wound bed, it does indicate that small differences in skin temperature can relate to damage. The range of inside dressing temperatures among the dressings was 1°C at 175 minutes and 0.8°C at 196 minutes, so these ranges could be problematic. While Yusuf’s study does not prove causation, we need to be aware of a possible effect of temperature on tissue integrity.

Temperature differences are cumulative. The rate at which temperature drops after a pressure release could affect this accumulation. A small difference accumulated over time can make a large difference. The drops in temperatures at 175 and 196 minutes per dressing were greatest for both the RespoSorb® dressings.

Limitations

It would be of interest to perform this study on a heavily exuding wound model rather than a vapour-exuding intact skin model in order to examine the performance of the dressings under conditions in which they are normally used more accurately.

Conclusion

This in vitro study concludes that SAF dressings and SAP dressings appear to be equally competent in maintaining a warm and moist microclimate at the wound bed level to enhance wound healing. They absorb more moisture per cm2 and evaporate or transpire more moisture than more basic dressings. The foam layer in SAF dressings does not appear to improve microclimate conditions at the wound bed over SAP dressings without the foam layer. Neither the SAF nor the SAP dressings dry the wound bed as the term superabsorber may imply. It was also shown that periodic relief of pressure markedly decreases temperature and humidity at the wound bed which enhances the function of the dressing and may increase wound healing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by Paul Hartmann AG, Heidenheim, Germany, manufacturer of RespoSorb® Silicone and RespoSorb® Silicone Border.

Comparación entre el manejo de líquidos y las condiciones microclimáticas por debajo de los vendajes de polímeros superabsorbentes y de espuma superabsorbente en una herida artificial

Evan Call, Craig Oberg, Iris Streit and Laurie M Rappl

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.4.11-23

Resumen

Introducción Se comparan los vendajes de polímeros superabsorbentes (SAP) y de espuma superabsorbente (SAF) respecto de su capacidad de absorber el exudado de humedad de una herida artificial y de afectar el microclima por debajo del vendaje midiendo: la cantidad de humedad absorbida; la cantidad de humedad evaporada a través de la capa externa; la humedad, tanto por debajo como por fuera del vendaje y la diferencia entre ambas; y la temperatura, tanto por debajo como por fuera del vendaje y la diferencia entre ambas.

Método Se utilizó un indentador termodinámico en un entorno de laboratorio con el fin de proporcionar un flujo constante de vapor de humedad en toda la superficie de la herida estándar para cada vendaje bajo el peso del indentador. Los sensores registraron la humedad y la temperatura por dentro y por fuera de cada vendaje durante 3 horas y 16 minutos con un porcentaje de reducción completo de 45 segundos del vendaje al punto de las 3 horas para simular el cambio de peso del paciente. Al finalizar la prueba se ponderaron los vendajes para determinar la humedad absorbida y la humedad evaporada.

Resultados No hubo diferencias importantes entre los grupos de vendajes de SAF y de SAP en cuanto a la absorción o a la evaporación de la humedad ni tampoco con respecto a la humedad y temperatura por dentro o por fuera de los vendajes.

Conclusión Por consiguiente, se puede determinar que los vendajes de SAF y de SAP parecen ser igualmente adecuados para mantener el microclima de humedad y calor en el lecho de la herida. Se debe destacar que estos vendajes no secan el lecho de la herida del modo que implica el término superabsorbente.

Introducción

Se seleccionan los vendajes de las heridas para controlar la humedad durante la cicatrización de la herida debido a tres motivos: absorber el exudado; mantener un microclima adecuado en el lecho de la herida; y proteger la periferia de la herida para protegerla del daño causado por la maceración debida al exceso de humedad. Las categorías generales de tecnologías de absorción son espumas, hidrocoloides, alginatos de calcio, hidrofibras y polímeros de retención de humedad1,2. Se alega que los vendajes de polímeros superabsorbentes (SAP) y de espuma superabsorbente (SAF) más complejos que han sido desarrollados de manera reciente son mejores que los vendajes anteriores con respecto al control de la humedad de la herida; sin embargo, estos últimos no se han evaluado comparándolos con los de SAP y de SAF. Además, el término superabsorbente plantea preguntas en cuanto a la posibilidad de sobreabsorción y, por consiguiente, del secado del lecho de la herida y de la inhibición de la cicatrización de la herida.

Control del exudado

Desde que Winters publicó su trabajo de gran trascendencia en 1963, la cicatrización húmeda de la herida se ha aceptado como una mejor práctica2,3. Las citocinas y otros factores de crecimiento necesitan humedad para esparcirse en todo el lecho de la herida para estimular la cicatrización mediante el cierre de la herida y la reepitelización4. Mantener el nivel de humedad adecuado en el lecho de una herida evita la desecación, hecho que les permite a las células epiteliales migrar libremente por toda la superficie de la herida. La mayoría de las heridas húmedas granulan, se epitelizan y cicatrizan dos o tres veces más rápido que las heridas secas5.

El exudado se produce de manera natural como parte del proceso de cicatrización de la herida y mantiene húmedo el lecho de la herida para estimular el cierre en la mayoría de las heridas. Algunos tipos de heridas naturalmente exudan más que otras, específicamente, las heridas venosas, las úlceras grandes por presión y las quemaduras. Las heridas crónicas son altamente exudativas debido a un estado constante de inflamación y de interrupción de la actividad celular normal. El exudado crónico de las heridas difiere marcadamente del exudado agudo de la herida que consiste en altos niveles de enzimas degradantes de proteínas, metaloproteasas de la matriz (MPM), neutrófilos y citocinas proinflamatorias. Por consiguiente, las heridas exudativas necesitan vendajes absorbentes cuya capacidad de absorción coincida con el flujo de exudados para mantener un nivel de humedad óptimo en el lecho de la herida. A medida que estas heridas comienzan a granular, el exudado disminuye y la necesidad de vendajes cambia de absorción a protección como característica primaria2.

La cantidad de exudado o humedad proveniente de una herida está normalmente documentada en la historia clínica de un paciente con descriptores subjetivos como leve, moderado, grave y excesivo en vez de con mediciones objetivas. Se han propuesto diferentes escalas validadas para documentar la cantidad del exudado, entre las que se incluyen la Herramienta de valoración de heridas de Bates-Jensen y la herramienta de escala de úlceras por presión para cicatrización (PUSH, por sus siglas en inglés). Cada escala brinda un descriptor para cada nivel de dicha escala. Se puede encontrar un resumen y una comparación de las herramientas disponibles y sus descriptores en Wound exudate: effective assessment and management, un documento consensuado sobre el exudado publicado por la World Union of Wound Healing Societies en 20195.

Microclima de la herida

Se ha identificado al microclima como un factor clave tanto en la prevención de las heridas como en la cicatrización. El microclima es la combinación de temperatura y humedad, y algunas veces de flujo de aire, en una región localizada en comparación con el ambiente o el área que la rodea6. Un entorno con humedad cálida propicia la cicatrización de la herida. Dini y cols.7 demuestran que la cicatrización de la herida es deficiente a <33 °C debido a una disminución de la actividad de neutrófilos, fibroblastos y células epiteliales. Este mismo estudio muestra una correlación entre las mejorías del lecho de la herida y las temperaturas del lecho de la herida entre 33–35 °C. Además, Salvo y cols.8 demuestran en dos estudios que esas temperaturas en un rango de 36–38 °C aparentemente fomentan la cicatrización de la herida.

Sin embargo, los vendajes resisten la fuga de humedad y aumentan los niveles de humedad y calor por debajo de ellos. Los vendajes de absorción avanzada pueden, por consiguiente, afectar el microclima del lecho de la herida al absorber una cantidad de humedad excesiva de la superficie de la herida y mantener el calor y la humedad a la vez que disipan el exceso de calor y humedad a través de la capa externa permeable al vapor. Los vendajes oclusivos no tienen estas funciones.

Piel de la periferia de la herida

La humedad excesiva en la piel intacta de la periferia de la herida debilita la dermis y la epidermis interrumpiendo la organización de los lípidos en el estrato córneo (EC) y los vínculos entre las células epidérmicas1. El aumento resultante en la permeabilidad hace que la periferia de la herida sea más susceptible a la invasión de contaminantes y al efecto combinado de la fricción y los cortes. El término daño de la piel asociado con la humedad (MASD, por sus siglas en inglés) se refiere globalmente a las lesiones epidérmicas resultantes de la exposición de la piel a la humedad (por ejemplo, por transpiración) e irritantes (por ejemplo, orina, heces, efluentes de ostomía, exudado de la herida)1. Una de las cuatro categorías clínicas del MASD es el daño de la piel en la periferia de la herida. Al sumarse los efectos debilitantes combinados de la adherencia de humedad, las enzimas en el exudado de la herida, que normalmente degradan los contaminantes en la herida, también degradan las proteínas en la piel intacta. El daño resultante puede provocar dolor, un aumento en el tamaño de la herida y la disminución de la migración de los queratocitos de los bordes de las heridas, por consiguiente, afecta el cierre de la herida9. Como tal, los médicos deberían elegir los vendajes que evitan que el exudado entre en contacto con la periferia de la herida mediante el bloqueo del exudado absorbido. Lo ideal es ajustar el tamaño del apósito de absorción de un vendaje al tamaño del lecho de la herida abierta en vez de prolongarlo hasta la periferia de la herida.

Fabricación de vendajes

Los vendajes son un método primario dinámico para la pérdida de humedad persistente del lecho de una herida seca o para la absorción de la humedad excesiva del lecho de la herida húmeda a la vez que se mantiene la periferia de la herida sin humedad excesiva.

Los vendajes básicos tales como apósitos hechos de gasa de algodón o absorbentes hechos de fibras de celulosa o espumas cubren el lecho de la herida y lo protegen de un trauma y del medioambiente, a la vez que sencillamente absorben la humedad. Los vendajes en isla incluyen un borde adherente alrededor del área absorbente. Los vendajes con mayor capacidad y mejores características se utilizan para tratar heridas altamente exudativas que pueden empapar los vendajes básicos.

Los vendajes SAP están compuestos por múltiples capas a fin de adaptarse a las heridas altamente exudativas tanto por absorción como por evaporación de la humedad de la herida. El centro superabsorbente es a menudo una combinación de polímeros de celulosa y de polímeros hidrofílicos envueltos en tisú de celulosa o en un material no tejido. La mayoría de los vendajes SAP tienen una capa externa de poliuretano permeable al vapor y de baja fricción que permite transpirar la humedad; por consiguiente, absorbe más exudado de la herida y permite un mayor tiempo de uso. El poliuretano con un índice de transmisión del vapor de la humedad mayor de 35g/m2/h se correlaciona con una cicatrización de la herida más rápida realizada con vendajes oclusivos10. La suma del líquido absorbido en el vendaje y del líquido transpirado a través del vendaje se llama capacidad de control del fluido de un vendaje, según lo define el Comité Europeo de Normalización11.

Algunos vendajes de SAP tienen adhesivo acrílico en el borde alrededor de la isla absorbente de modo que no es necesario usar más cinta u otro tipo de fijación para dicho vendaje. Algunos de estos vendajes también cuentan con una capa de silicona en toda la superficie de la herida del vendaje para minimizar el trauma del lecho de la herida. Véase el Cuadro 1 para una revisión de las similitudes y diferencias entre un grupo representativo de estos vendajes.

Cuadro 1. Tamaño y construcción de vendajes de prueba representativos.

También se debe resaltar que el término superabsorbente puede implicar que un vendaje pueda extraer demasiada humedad de una herida y la seque, por consiguiente, contrarrestando la cicatrización de la herida húmeda. Un subgrupo de los vendajes de SAP –vendajes de SAF– está realizado de manera similar a los vendajes de SAP e incluyen una capa adicional de espuma entre la silicona y el polímero que se supone que evita que se seque el lecho de la herida y que optimice el microambiente del lecho de la herida (Cuadro 1). Además, quitar la presión de una herida y del vendaje a través de la maniobra de liberación de presión o mediante un cambio de posición del paciente puede afectar la evaporación de la humedad y la disipación del calor, y mejorar la función del vendaje, aumentando el tiempo de uso.

Hay pocos estudios publicados que comparan los efectos de diferentes vendajes, usados por pacientes, sobre tipos de heridas similares, y ninguno analiza las afirmaciones hechas por los fabricantes en referencia a los beneficios de sus productos que afectan el lecho de la herida o el microclima. La investigación clínica que compare los vendajes es muy difícil de lograr debido a las diversas variables que afectan la cicatrización de la herida y la tarea imposible de estandarizar a los pacientes. No obstante, una investigación de laboratorio bien diseñada puede estandarizar el tamaño de la herida y la cantidad de exudado, de modo que se puedan comparar los vendajes de prueba entre sí. Esta estandarización limita la aplicabilidad de los resultados a la población clínica altamente variable, pero puede proporcionar pruebas para dar una orientación con respecto a la eficacia de un vendaje al controlar las propiedades físicas de una herida para optimizar la cicatrización de la herida.

Objetivo del estudio

Este estudio in vitro compara los vendajes en las categorías de vendajes SAF y SAP descritas en el Cuadro 1. Se incluyó un vendaje quirúrgico básico no polímero como control o punto de referencia.

Se estudiaron los vendajes de acuerdo con su capacidad de absorber el exudado de la humedad de una herida artificial midiendo:

- La cantidad de humedad absorbida, informada como gramos totales por vendaje y g/cm2.

- La cantidad de humedad evaporada a través de la capa externa, informada como gramos totales por vendaje y g/cm2.

- Humedad, tanto dentro del lecho de la herida cubierta como en la capa externa y la diferencia entre ambas.

- Temperatura, tanto dentro del lecho de la herida cubierta como en la capa externa y la diferencia entre ambas.

Además, se midió el efecto de la liberación de una presión o del cambio de posición del paciente en cada uno de estos parámetros.

Es importante destacar que en el trabajo anterior se informó sencillamente como humedad por vendaje12. Para este estudio, estos valores se informan en gramos de humedad por cm2 debido a la gran variación del área de superficie y de la masa de los vendajes.

Método

Este estudio fue realizado por un laboratorio independiente que contribuye a la elaboración de las normas para las superficies de apoyo, cojines para sillas de ruedas, vendajes y otros equipos médicos relacionados con las heridas. El laboratorio tenía una temperatura ambiente de 23 °C ±2 °C y una humedad relativa del 50 % ±5 %, según lo especificado en la norma ISO 554-1976(E)13.

El modelo humano era un cojín rígido termodinámico de bronce que carga un indentador descrito primero por Ferguson-Pell y cols.14 para ser utilizado en las pruebas de cojines para sillas de ruedas. El modelo fue desarrollado por un grupo de investigadores del Reino Unido, Japón y los Estados Unidos. Desde 2009, se ha convertido en una pieza estándar de los equipos de pruebas para estudiar las superficies de apoyo, los vendajes y los cojines para sillas de ruedas en el mercado internacional del cuidado de heridas15 (Figura 1).

El indentador de prueba cumplía con las Normas Nacionales Estadounidenses para Superficies de Apoyo16. La forma del indentador es similar a las nalgas y a la parte superior de los muslos de un hombre de percentilo 50.o y tiene orificios pretaladrados en el área del sacro y del ísqueo. El indentador se puede cargar con cantidades de agua, caliente o fría, medidas previamente y pesadas. La difusión del agua a través de los orificios pretaladrados simula la pérdida de humedad a través de la piel. Este indentador simula el calentamiento, el enfriamiento, la sudoración y el secado, el peso y la eliminación del peso del área sacra humana. Se miden las condiciones resultantes en la interfaz superficie-indentador y se pueden comparar entre productos, así como también en condiciones de estado estable y transitorio.

Para este estudio, se le colocó al indentador un peso de 64 lb ± 2,25 lb (justo por encima de 29 kg ± justo por encima de 1 kg) que es el peso de este segmento del cuerpo para un hombre de percentilo 50.o que está en la cama en posición supina. Se generó una herida artificial cubriendo todos los orificios de los poros de sudoración que no estaban cubiertos por un apósito de vendaje; la cinta de aluminio aseguró que no se evaporara la humedad por el área de la herida artificial (Figura 2). Esto dejó un área de orificios de 7x7 cm para el vapor de humedad; esto se utilizó para todos los vendajes probados.

Discutir los vendajes bajo estas condiciones brinda un escenario que es clínicamente pertinente porque las espumas y los polímeros se comprimen y se reduce la fuga del vapor de humedad por las condiciones de uso actual de la prueba14,15. Por ejemplo, los sensores de humedad y temperatura son sensores digitales de alta precisión fabricados por Sensirion AG (Staefa ZH, Suiza) que tienen una precisión de ±1,8 % a una humedad relativa de 0–80 % y ±0,3 °C a 20–50 °C. La superficie de apoyo de la prueba era un cojín de espuma de celdas abiertas de 3x18x18” (7,6x45,7x45,7 cm) cubierto con un colchón de agua, respirable, resistente a la humedad fabricado por Dartex Coating US (Slaterville, RI) y colocado sobre una tabla rígida para el colchón.

Se humectó y humidificó por medio de una cantidad pesada de agua destilada embebida en toallas refrigerantes de microfibra EnduracoolTM. Se eligió esta toalla debido a que la microfibra es una tecnología termoreguladora con un índice de liberación de humedad compatible con los estudios anteriores publicados en las superficies de apoyo LAL17,18. En un entorno de laboratorio, el exudado de la herida está representado por el agua destilada. Si bien las propiedades de cada líquido difieren notoriamente, el estudio está diseñado para demostrar las diferencias de rendimiento, y esto se puede lograr con un fluido estándar. Las publicaciones anteriores que caracterizan la capacidad de controlar la humedad de los vendajes utilizando este método brindan una referencia comparativa12.

El modelo de herida utilizado aquí no es un modelo altamente exudativo; es un modelo del vapor de agua. Este modelo ingresa un bajo nivel de humedad a la superficie del vendaje durante un período y de manera controlada de modo que un investigador puede determinar si la humedad está vinculada al vendaje o transpira a través del mismo. Se eligieron los vendajes de prueba a partir de vendajes multicapas utilizados comúnmente y adquiridos de manera conveniente en la Unión Europea y en los Estados Unidos. Los vendajes representativos están enumerados en el Cuadro 1.

El indentador fue suspendido sobre el cojín por medio de un marco H que se colocó alrededor del bastidor de la cama aproximadamente en el medio de dicho bastidor. El cojín fue centrado debajo del indentador de modo que el área de tuberosidad ísquea del indentador quedó ubicada a 10–15 cm del borde posterior del cojín (Figura 3). El indentador fue configurado a 37 °C. Se registraron los pesos de dos juegos secos de toallas EnduracoolTM, después se agregó 100±1 g de agua destilada a cada juego de toallas proporcionando un potencial de ingreso de 200 g para el vendaje. Cada toalla se plegó en tres partes y se colocó dentro del indentador de modo que las toallas cubrieran todos los orificios de los poros de sudoración. Se colocaron pesos calientes encima de las toallas para facilitar el ingreso de la humedad.

Se colocaron tres sensores para medir el escape de humedad del área de la herida artificial (Figura 4). Se modificaron las ubicaciones de los sensores para adaptarlas al tamaño de cada vendaje. Se centró el vendaje sobre los orificios de los poros de sudoración abiertos y se cubrieron los tres sensores. Se colocaron los sensores que estaban por fuera del vendaje y se los alineó con los que estaban por debajo del vendaje (Figura 4). Se bajó el indentador para que se asiente sobre la superficie de apoyo y se transfirió la carga total de 64 lb ± 2,25 lb (justo por encima de 29 kg ± justo por encima de 1 kg) a la superficie de apoyo. Se utilizó un séptimo sensor para medir la temperatura ambiente y la humedad. Se programó un EK-H4 Viewer para que registre los datos a intervalos de 30 segundos a través de un período de prueba.

Para simular una liberación de presión o el cambio de posición del paciente, se levantó el indentador de la superficie de apoyo durante 45 segundos a las 3 horas ± 6 minutos. Se realizaron lecturas cinco minutos antes de levantarlo, identificadas como 175 minutos en la sección de resultados, para lograr una cámara de aire entre el indentador y la superficie de apoyo. Se sostuvo complemente suspendido sobre la superficie de apoyo durante un total de 45 segundos ± 10 segundos, después se lo bajó nuevamente a la superficie de apoyo totalmente cargado por otros 15 minutos ± 1 minuto. En los resultados se informaron las lecturas finales como 196 minutos.

Al final de la prueba se levantó el indentador, se quitaron las toallas y se pesaron. Se quitó el vendaje del indentador y de la herida artificial, y se registró el peso. Se registró el peso de una toalla de papel seca, la toalla se utilizó para secar toda la humedad restante en el indentador y se pesó la toalla nuevamente.

Entre cada prueba, el indentador volvió a su estado estable antes de iniciar la siguiente prueba. Se agregó agua destilada para que las toallas y la masa de agua volvieran al peso total de las toallas secas además de 200±1 g de agua destilada. Se utilizaron dos cojines y dos cobertores; estos se intercambiaron entre pruebas para permitir una recuperación total. Se realizó un total de tres pruebas para cada vendaje. También se realizaron tres pruebas con el indentador colgando en el aire durante 3 horas y 16 minutos sin que se aplicara un vendaje para medir la salida del vapor de humedad de la herida artificial.

El peso final de las toallas además de la toalla de papel se restó del peso inicial de las toallas para asegurar que la cantidad total de agua destilada haya ingresado al sistema. La humedad absorbida por el apósito del vendaje fue calculada restando el peso inicial del vendaje del peso final del vendaje. La cantidad de vapor de agua producida a partir del sistema se calculó restando el peso inicial de las toallas del peso final de las toallas y agregando la humedad recuperada del interior del indentador utilizando una toalla de papel. La cantidad de humedad que evaporó el vendaje se calculó restando la cantidad de humedad atrapada en los vendajes de la cantidad de vapor de agua producida por el sistema. Se calculó el IC de un 95 %.

Si bien el tamaño de la herida artificial fue constante durante todo el estudio, los apósitos absorbentes de los vendajes variaron de 41,8 cm2 a 121 cm2 (Cuadro 1). De este modo se calculó la humedad total absorbida y evaporada por cada vendaje. Se hicieron cálculos de la humedad absorbida y de la humedad evaporada en base a cm2, así como también para dar cuenta de la variabilidad de los tamaños del vendaje y para comparar con más precisión el rendimiento del vendaje. Se calculó la diferencia promedio de temperatura y humedad entre la parte externa o superficie del cojín del vendaje y la parte interior o el lado del paciente del vendaje a los 175 minutos y durante la duración total de la prueba haciendo un promedio de la diferencia entre el valor sobre el vendaje y el valor por debajo del vendaje para cada punto de datos.

Resultados

El estudio tuvo cuatro objetivos, concretamente medir: la cantidad de humedad absorbida; la cantidad de humedad evaporada a través de la capa externa; la humedad, tanto por debajo como por fuera del vendaje y la diferencia entre ambas; y la temperatura, tanto por debajo como por fuera del vendaje y la diferencia entre ambas.

La cantidad de humedad que absorbió cada vendaje se indica en el Cuadro 2. Esto indica la humedad total y la humedad absorbida en g/cm2 por vendaje, así como también indica el promedio. El rango del grupo del vendaje de SAF fue de 0,22–0,34 g. El rango del grupo del vendaje de SAP fue de 0,24–0,39 g si no se tiene en cuenta la capa externa de 0,56 g. El vendaje de referencia fue el más pequeño del área y, por gran diferencia, el que menos absorbió. El rango para seis de los siete vendajes del estudio fue de 0,22–0,39 g.

Cuadro 2. Humedad absorbida en un apósito de absorción y humedad evaporada por vendaje en g y g/cm2 totales y promedios de SAF y de SAP.

La cantidad de humedad evaporada (transpirada o evaporada) a través de la capa de poliuretano externa también se indica en el Cuadro 2 y en la Figura 5. El rango del grupo de vendaje de SAF fue de 3,9–5,4 g, una diferencia de 1,5 g, mientras que el rango del grupo de vendaje de SAP fue de 3,4–4,1 g, una diferencia de solo 0,7 g. Por cierto, seis de los siete vendajes del estudio estuvieron dentro de los 0,7 g entre ellos (rango 3,4–4,1 g). No hubo una diferencia significativa entre los vendajes a un IC de un 95 %.

En el Cuadro 2, se debe tener en cuenta que el total de humedad proporcionado por el indentador fue de 5,9 g. Al agregar la humedad absorbida y la humedad evaporada en conjunto se demuestra que ninguno de los vendajes eliminó toda la humedad.

La Figura 5 grafica la cantidad total de humedad absorbida y humedad evaporada en g/cm2 para cada vendaje. Las Figuras 6a y 6b grafican la humedad absorbida y la humedad evaporada por cm2 organizado por orden de tamaño del apósito absorbente, desde el más pequeño hasta el más grande. A medida que el tamaño del vendaje aumentaba, la cantidad de humedad absorbida y la que escapaba por cm2 parece disminuir, lo que hace presumir que el rendimiento de los apósitos más grandes es más deficiente. Sin embargo, los vendajes más grandes tienen mayor área disponible para absorber y evaporar la humedad, y este gráfico no está estandarizado ni para la herida ni para el tamaño del vendaje.

La Figura 7 grafica la humedad evaporada por cm2 por área de la herida. Esto implica que los vendajes se comparan utilizando tanto un tamaño de herida estándar –el área de orificios expuestos en el indentador– como una cantidad de vapor estándar en un área estándar. Al compararlo de este modo, todos los vendajes controlan aproximadamente la misma cantidad de humedad de acuerdo con su área absorbente.

También se registró la humedad, tanto por debajo como por fuera del vendaje, así como también la diferencia entre ambas. El Cuadro 3 muestra el porcentaje promedio de la humedad relativa a los 175 minutos (antes de liberar la presión) y a los 196 minutos (después de que se hubiera aplicado presión durante 15 minutos, al finalizar la prueba), por fuera y por dentro de los vendajes, y la diferencia entre los vendajes por dentro y por fuera, por vendaje y por grupo. A los 175 minutos todas las lecturas de humedad por fuera de los vendajes estaban por sobre las de la temperatura ambiente 50 %), que indicaba la transpiración activa en todos los soportes de poliuretano. El grupo de vendaje de SAF tuvo un promedio mayor de humedad, tanto por dentro como por fuera del vendaje que el grupo de vendaje de SAP, pero la diferencia entre los vendajes por dentro y por fuera de ambos grupos fue similar, 11,4 y 12,2 %, respectivamente. El vendaje de referencia tuvo una humedad mucho mayor tanto por dentro como por fuera del vendaje, con una diferencia de solo 3,8 % (Cuadro 3 y Figura 8). A los 196 minutos, el grupo de vendaje de SAF tuvo un promedio mayor de humedad, tanto por dentro como por fuera del vendaje que el grupo de vendaje de SAP, pero la diferencia entre los vendajes por dentro y por fuera fue mayor en el grupo de vendaje de SAF. El vendaje de referencia tuvo una pequeña diferencia entre el vendaje por dentro y por fuera (Cuadro 3). Al mirar las barras de error en la Figura 8, no hubo diferencias importantes entre los vendajes en el IC de 95 %.

Cuadro 3. Porcentaje promedio de la humedad relativa a los 175 y 196 minutos.

También se registró la temperatura, tanto por debajo como por fuera del vendaje, así como también la diferencia entre ambas. A los 175 minutos, las temperaturas promedio del grupo de vendaje de SAF, el grupo de vendaje de SAP y el vendaje de referencia estuvieron dentro del 0,9 °C. Los grupos de vendaje de SAF y de SAP tuvieron diferencias más amplias de temperatura por dentro y por fuera de los vendajes que el vendaje de referencia (Cuadro 4 y Figura 9). A los 196 minutos, las temperaturas promedio de los vendajes de SAF y de SAP, tanto por dentro como por fuera de los vendajes, estuvieron dentro de 0,2 °C de cada una. El vendaje de referencia estuvo ligeramente por debajo de ambos grupos (Cuadro 4 y Figura 10). El rango de temperaturas por dentro y por fuera de los vendajes a los 196 minutos fue de 33,1–34,3 °C. El rango de la diferencia de temperatura por dentro y por fuera de los vendajes fue de 0,4–0,8 °C. El control negativo tuvo una diferencia de temperatura de solo 0,2 °C. No hubo diferencias importantes entre los vendajes en el IC de 95 %.

Cuadro 4. Temperatura promedio a los 175 y 196 minutos.

Discusión

El presente estudio mide el rendimiento relativo de los vendajes en un entorno de laboratorio comparando resultados en puntos de tiempo específicos y promediados en el tiempo. Si bien el período de prueba de más de 3 horas es un segmento de tiempo pequeño en comparación con la cantidad de tiempo que un paciente normalmente utiliza estos tipos de vendajes, la prueba da un indicio de cómo puede ser el rendimiento relativo con respecto a otros en períodos más largos.

Este método probó la manera en que los vendajes controlan la humedad a partir de un bajo exudado de vapor constante. Cuando el tegumento en una herida de estadio 2, 3 o 4 está comprometido, la regulación de la fuga del vapor de humedad también está comprometida, lo que se suma a la humedad que debe controlar un vendaje. El vapor total puede comprometer el tegumento y, por consiguiente, esto también debe tenerse en cuenta al evaluar los vendajes6,19.

Como se esperaba, los vendajes de SAF y de SAP más avanzados tuvieron mejor rendimiento que el vendaje en isla básico del punto de referencia/control en la mayoría de las categorías.

Humedad absorbida y humedad evaporada

Tanto los grupos de vendajes de SAF como los de SAP absorbieron de manera significativa más humedad en el apósito que el vendaje de referencia, lo que indica que sus materiales de polímero absorben y atrapan la humedad, y evitan que migren a la periferia de la herida o al lecho de la herida. Seis de los siete vendajes avanzados absorbieron entre un 0,24–0,39 g, y una capa externa absorbió un 0,56 g. Se espera que los vendajes absorban lo suficiente como para evitar la maceración del lecho de la herida, pero no tanto como para secarla. A fin de secar una herida, un vendaje debería absorber y transpirar toda la humedad que ingresa. Ninguno de estos vendajes lo hicieron, por consiguiente, el total de humedad para cada vendaje del Cuadro 2 no iguala la humedad total ingresada por el indentador, 5,9 g. A partir de estos resultados, parece que los vendajes de SAF y de SAP tienen la capacidad de absorber y que no secarán una herida que exuda al nivel moderado del accesorio de prueba. El ALLEVYN Life es el que más se acerca a la absorción y transpiración de todos los líquidos proporcionados.

Se ingresó la misma cantidad de humedad a todos los vendajes. El vendaje más pequeño tuvo la menor cantidad de humedad absorbida y la mayor humedad evaporada; esto es esperable porque el tamaño de la herida fue constante en todo el vendaje, dejando un porcentaje del área de la herida artificial para que ingrese humedad al área del vendaje que esté accesible para transpirar considerablemente más que los vendajes más grandes. Los vendajes más grandes pudieron absorber y retener más, y el polímero atrapó esa humedad para que no pudiera fugarse y de hecho esto no ocurrió. Los vendajes más grandes también pueden esparcir y difundir la humedad a un área más grande.

El grupo de vendajes de SAF, el grupo de vendajes de SAP y el vendaje de referencia no fueron significativamente diferentes con respecto a la cantidad de líquido que evaporaron o transpiraron del área de la herida a un IC de un 95 % (Figura 6b). Cuando la humedad evaporada se grafica basada tanto en la humedad provista como en el área del apósito en g/cm2, los vendajes avanzados son muy similares (Figura 7). Los diferentes tamaños de apósitos pueden afectar los resultados. Sin embargo, cuando se muestran los resultados en g/cm2 a fin de comparar los diferentes tamaños de vendajes, las diferencias son muy pequeñas. Esto dificulta la interpretación.

Esta prueba fue realizada de manera compatible con otras pruebas, algunas publicadas y otras no publicadas, en las que se indicaban notables diferencias de humedad controlada entre los vendajes avanzados6,12. Este hecho inspiró a los fabricantes para mejorar sus productos, y los soportes de polímeros y permeables al vapor usados en los vendajes posiblemente den como resultado más uniformidad en las estructuras del vendaje y la similitud en la capacidad de control aparente entre los vendajes probados.

Humedad y temperatura

Aún no se han determinado mediante investigación clínica o de laboratorio los valores específicos de temperatura y humedad que definen el microclima óptimo. Se espera que los vendajes mantengan el lecho de la herida moderadamente cálido y húmedo en vez de demasiado mojado o demasiado seco, demasiado cálido o demasiado frío en relación con las condiciones dérmicas o subdérmicas normales del cuerpo del paciente y con la atmósfera externa. La mayor humedad y los niveles de humedad pueden producir un impacto negativo en el entorno de la herida a medida que debilitan la piel intacta1. El SC está en hidratación de equilibrio a una humedad ambiente de 40–60 %, pero absorbe agua a índices desproporcionadamente crecientes por encima de un 60 %20–22. Los resultados de Wildnauer muestran que la humedad relativa por encima de un 60 % tiene la mayor influencia al disminuir fuerzas cohesivas internas dentro del SC23.

A los 175 minutos, todos los vendajes se encontraban por encima de un 75 % de humedad relativa por debajo del vendaje con un rango de 83,5–86,6 % para los vendajes de SAF y 76,4–81,1 % para los vendajes de SAP. Es razonable considerar estos valores como humedad. Los vendajes con mayores humedades por dentro –el grupo de vendaje de SAF y el vendaje de referencia a un 90,5 %– pueden ser un motivo de preocupación al sobrehidratar potencialmente el lecho de la herida o la periferia de la herida. A los 175 minutos, todos los vendajes también tenían menores lecturas de humedad por fuera del vendaje que por dentro, tal como era de esperar. Todos los niveles de humedad por fuera de los vendajes eran mayores que los del ambiente, lo que indica que el soporte de poliuretano sí evapora o transpira líquido. Hubo una correlación entre la humedad relativa por debajo del vendaje y la humedad absorbida por el apósito del vendaje. La menor humedad absorbida por el apósito se correlaciona con la mayor humedad por debajo del vendaje (coeficiente de correlación de Pearson = –0,83).

La liberación total de presión a los 176 minutos detuvo el indentador y el vendaje de prueba al aire, y permitió el intercambio de calor y humedad con el ambiente. La Figura 11 indica los resultados graficados para uno de los vendajes, RespoSorb® Silicone, durante los 196 minutos de la prueba. Esto ilustra una evolución similar vista en todos los vendajes. Las temperaturas y humedades se elevaron de manera precoz en la recopilación de datos, luego las temperaturas finalmente se quedaron en una meseta mientras que las humedades continuaron aumentando. Ambos valores descendieron abruptamente cuando se subió el indentador para la liberación de presión de 45 segundos, después se elevaron a casi los niveles previos a que fuera subido. Resultó impresionante el hecho de que una liberación de presión pudiera tener un efecto rápido, mensurable y significativo tanto en el calor como en la humedad, lo que demuestra los beneficios de los cambios frecuentes de posición más allá de abordar simplemente la presión y el corte. Quince minutos después de elevar la liberación de la presión, a los 196 minutos, todos los niveles de humedad estaban por encima de un 70 %, y el vendaje de referencia estaba en su pico a un 87,6 %. Parece que el vapor de humedad escapa más rápidamente de lo que es atrapado, dentro de los 15 minutos de ser subido, todos los valores regresaron a los niveles de los 175 minutos.

Ambos grupos de vendajes mantuvieron el lecho de la herida relativamente tibios según lo indican las temperaturas más bajas por fuera del vendaje que por dentro del mismo. Esto conduce a la cicatrización de la herida dentro del rango recomendado de 33–35 °C7. Yusuf y cols.24 informaron que una diferencia en la temperatura de la piel de solo 0,3 °C pronosticaba la ulceración por presión. Si bien esta medición no está hecha en el lecho de la herida, indica que pequeñas diferencias en la temperatura de la piel puedan estar relacionadas con el daño. El rango de temperaturas internas del vendaje entre los vendajes era de 1 °C a los 175 minutos y de 0,8 °C a los 196 minutos, de modo que estos rangos pueden ser problemáticos. Si bien el estudio de Yusuf no prueba la causa, necesitamos ser conscientes de un posible efecto de la temperatura sobre la integridad del tejido.

Las diferencias de temperatura son acumulativas. El índice al cual la temperatura cae después de liberar la presión puede afectar esta acumulación. Una pequeña diferencia acumulada en el tiempo puede marcar una gran diferencia. Las caídas de temperaturas a los 175 y 196 minutos por vendaje fueron las mayores para ambos vendajes RespoSorb®.

Limitaciones

Sería de interés realizar este estudio en un modelo de herida con alta exudación en vez de realizarlo en un modelo de piel intacta que exuda vapor a fin de analizar el rendimiento de los vendajes bajo las condiciones en las que normalmente se utilizan con más precisión.

Conclusión

La conclusión de este estudio in vitro es que los vendajes de SAF y los vendajes de SAP parecen ser igualmente adecuados para mantener el microclima de humedad y calor en el lecho de la herida para mejorar la cicatrización de la herida. Absorben más humedad por cm2 y evaporan o transpiran más humedad que los vendajes más básicos. La capa de espuma en los vendajes de SAF no parece mejorar las condiciones microclimáticas en el lecho de la herida con respecto a los vendajes de SAP sin la capa de espuma. Ni los vendajes de SAF ni los de SAP secan el lecho de la herida del modo que implica el término superabsorbente. También se demostró que el alivio periódico de la presión disminuye notoriamente la temperatura y la humedad en el lecho de la herida, lo que mejora la función del vendaje y puede aumentar la cicatrización de la herida.

Conflicto de intereses

Los autores declaran que no hay conflictos de intereses.

Financiación

Este estudio fue financiado por Paul Hartmann AG, Heidenheim, Alemania, fabricante de RespoSorb® Silicone y RespoSorb® Silicone Border.

Author(s)

Evan Call

MS, CSM (NRM)

Department of Microbiology, College of Science, Weber State University, Ogden, UT, USA

Craig Oberg

PhD

Department of Microbiology, College of Science, Weber State University, Ogden, UT, USA

Iris Streit

Senior Manager, Global Product Marketing Advanced Wound Management,

HARTMANN GROUP, Heidenheim, Germany

Laurie M Rappl*

PT, DPT, CWS

Rappl & Associates, Simpsonville, SC, USA

Email Lrappl630@gmail.com

* Corresponding author

References

- Woo KY, Beeckman D, Chakravarthy D. Management of moisture-associated skin damage: a scoping review. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017;30(11):494–501.

- Seaman S. Dressing selection in chronic wound management. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2002;92(1):24–33.

- Winter GD, Scales JT. Effect of air drying and dressings on the surface of a wound. Nature 1963;197:91–2.

- Rippon MG, Ousey K, Cutting KF. Wound healing and hyper-hydration: a counterintuitive model. J Wound Care 2016;25(2):68, 70–5.

- World Union of Wound Healing Societies. Wound exudate: effective assessment and management: WUWHS consensus document. London (UK): Wounds International; 2019.

- Kottner J, Black J, Call E, Gefen A, Santamaria N. Microclimate: a critical review in the context of pressure ulcer prevention. Clin Biomech;2018;59:62–70.

- Dini V, Salvo P, Janowska A, Di Francesco F, Barbini A, Romanelli M. Correlation between wound temperature obtained with an infrared camera and clinical wound bed score in venous leg ulcers. Wounds 2015;27(10):274–8.

- Salvo P, Dini V, Kirchhain A, Janowska A, Oranges T, Chiricozzi A, et al. Sensors and biosensors for C-reactive protein, temperature and pH, and their applications for monitoring wound healing: a review. Sensors;2017;17(12).

- Woo KY, Sibbald RG. The ABCs of skin care for wound care clinicians: dermatitis and eczema. Adv Skin Wound Care 2009;22(5):230–6; quiz 7–8.

- Bolton LL, Johnson CL, van Rijswijk L. Occlusive dressings: therapeutic agents and effects on drug delivery. Clin Dermatol 1992;9.

- European Standards. Test methods for primary wound dressings. Part 1: aspects of absorbency. Brussels (Belgium): European Committee for Standardization; 2002.

- Call E, Pedersen J, Bill B, Oberg C, Ferguson-Pell M. Microclimate impact of prophylactic dressings using in vitro body analog method. Wounds 2013;25(4):94–103.

- ISO. ISO 554:1976E Standard atmospheres for conditioning and/or testing: specifications. Geneva (Switzerland): International Organization for Standardization; 1976.

- Ferguson-Pell M, Hirose H, Nicholson G, Call E. Thermodynamic rigid cushion loading indenter: a buttock-shaped temperature and humidity measurement system for cushioning surfaces under anatomical compression conditions. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009;46(7):945–56.

- Call E, Pedersen J, Bill B, Black J, Alves P, Brindle CT, et al. Enhancing pressure ulcer prevention using wound dressings: what are the modes of action? Int Wound J 2015;12(4):408–13.

- ANSI/RESNA. ANSI/RESNA SS-1-2019 for support surfaces volume 1: requirements and test methods for full body support surfaces. Arlington (USA): Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America; 2019.

- Figliola RS. A proposed method for quantifying low-air-loss mattress performance by moisture transport. Ostomy Wound Manage 2003;49(1):32–42.

- Reger SI, Adams TC, Maklebust JA, Sahgal V. Validation test for climate control on air-loss supports. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82(5):597–603.

- Phipps L, Gray M, Call E. Time of onset to changes in skin condition during exposure to synthetic urine: a prospective study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(4):315–20.

- Imhof RE, De Jesus ME, Xiao P, Ciortea LI, Berg EP. Closed-chamber transepidermal water loss measurement: microclimate, calibration and performance. Int J Cosmet Sci 2009;31(2):97–118.

- Li X, Johnson R, Kasting GB. On the variation of water diffusion coefficient in stratum corneum with water content. J Pharm Sci 2016;105(3):1141–7.

- Petrofsky JS, Berk L, Alshammari F, Lee H, Hamdan A, Yim JE, et al. The interrelationship between air temperature and humidity as applied locally to the skin: the resultant response on skin temperature and blood flow with age differences. Med Sci Monit 2012;18(4):CR201–8.

- Wildnauer RH, Bothwell JW, Douglass AB. Stratum corneum biomechanical properties: I. Influence of relative humidity on normal and extracted human stratum corneum. J Investig Dermatol 1971;56(1):72–8.

- Yusuf S, Okuwa M, Shigeta Y, Dai M, Iuchi T, Rahman S, et al. Microclimate and development of pressure ulcers and superficial skin changes. Int Wound J 2015;12(1):40–6.