Volume 39 Number 4

Management of complex head wounds involving the temporalis and sternocleidomastoid muscles: a case series

Angela Yi Jia Liew and Yee Yee Chang

Keywords Head and neck, wound breakdown, chronic wound, chemo-radiation therapy, split skin graft, wound bed preparation

For referencing Liew AYJ & Chang YY. Management of complex head wounds involving the temporalis and sternocleidomastoid muscles: a case series. WCET® Journal 2019;39(4):41-44

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.4.41-44

Abstract

The use of a comprehensive wound assessment tool and appropriate selection of dressing products can aid clinicians in the management of complex wounds. This paper describes the care of two patients presenting with head wounds. The first case is a patient who suffered from a right temporalis flap failure and exposed periosteum after wide excision. The second case explores the management of a sternocleidomastoid abscess that developed during radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. The paper outlines how the choice of healing by secondary intention can prevent patients from undergoing additional surgeries where outcomes may not be favourable.

Introduction

Medical advancements in the management of head and neck cancers allow patients the flexibility of choice in their treatment. However, factors such as active immunotherapy treatments or previous surgical resection can affect the healing outcome or result in an unhealthy wound bed1. In addition, patients may not be suitable candidates for surgery or may prefer conservative management.

This case series will explore two cases which utilised conventional dressing products to assist with wound closure. The first case discusses a patient with a failed right temporal split skin graft with exposed cranium after wide excision for treatment of basal cell carcinoma. The second case focused on a patient who developed a neck abscess at the sternocleidomastoid region during chemotherapy and had undergone incision and drainage. Both cases were reviewed using the triangle of wound assessment which provided the clinicians with a guide for holistic evaluation2.

Case one

Mr A was a 77-year-old Chinese gentleman who presented at the head and neck specialist outpatient clinic in an acute tertiary hospital with a right temporal lesion on 29 April 2016. The lesion had been present since birth; however he had noticed an increase in size to 1x3cm after an accidental injury during a haircut two years ago. The lesion had no contact bleeding, no discharge and was non-tender. Head and neck examination revealed no palpable cervical lymph nodes. Mr A underwent an excision biopsy of the right temporal lump in May 2016. Histology showed apocrine adenocarcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising from a nevus sebaceous cyst. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed no significant Fludeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in other areas, but Mr A required a wider excision for adequate clearance of the tumour.

On 23 May 2016, Mr A underwent a wide excision in which a right temporalis flap was used to cover the exposed periosteum, followed by a split skin graft to cover the wound bed. The split skin graft was anchored down with a polyurethane foam dressing, and the patient was discharged 2 days later. Initial wound inspection of the right temporalis flap 10 days later showed that the split skin graft had taken well. However, wound inspection a week later showed slough at the edges of the split skin graft, and that the periosteum was exposed. The patient’s wound was managed with Aquacel® Ag (United Kingdom), a hydrofiber with silver, and he was offered another surgery for flap coverage as the wound remained stagnant despite every other day change of dressing. His primary surgeon referred him to the wound care team as Mr A refused surgery and requested a conservative approach instead.

On inspection, the right temporalis wound measured 3x5cm overall with a depth of 1cm (Figure 1). The wound bed contained the exposed periosteum measuring 2x3cm with sloughy wound edges and areas of grafted skin which had taken. No signs of local infection were detected. Shaving of hair around the periwound region was done to maintain a good margin for the application of dressings. Wound clinicians did conservative sharp debridement of devitalised tissue at the wound edges. The wound was cleaned with normal saline and primarily dressed with Heliaid®, a collagen sheet dressing. The patient was taught to change the external gauze if stained for exudate control.

On presentation 1 month later, the patient’s wound showed friable, hyper granulating tissue at the inferior aspect of the wound bed (Figure 2). Shave excision using a blade was done to manage the hyper granulating tissue weekly, and the collagen dressing was not changed if it had not degraded as it served as a scaffold for granulating tissue to migrate and cover the exposed periosteum3.

A review by the surgeon 3 months later showed the edges of the wound contracting, covering the periosteum (Figure 3). Hypertrophic granulation was still present at wound edges and required periodic shave excision. Collagen dressing was used until full epithelialisation occurred 5 months after the initial consultation with the wound care team (Figure 4).

Case Study 2

Mr B, a 71-year-old Chinese gentleman who had radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the right tonsil presented to the emergency department with an abscess over the right sternocleidomastoid region. A computerised tomography (CT) scan of the neck showed the development of a multi-loculated abscess along the entire length of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle with overlying cellulitis. He underwent emergency incision and drainage of the abscess. As Mr B was undergoing active radiotherapy treatment and was therefore not a surgical candidate for removal of the SCC, he was referred to the wound care team for follow-up management of his surgical site.

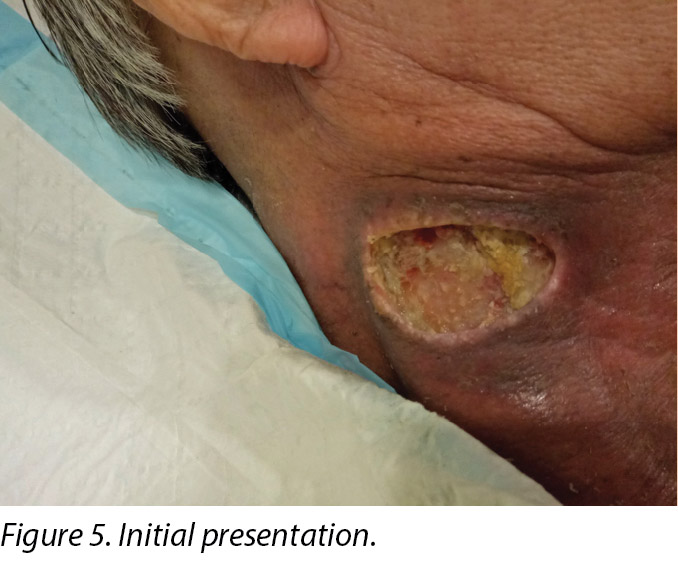

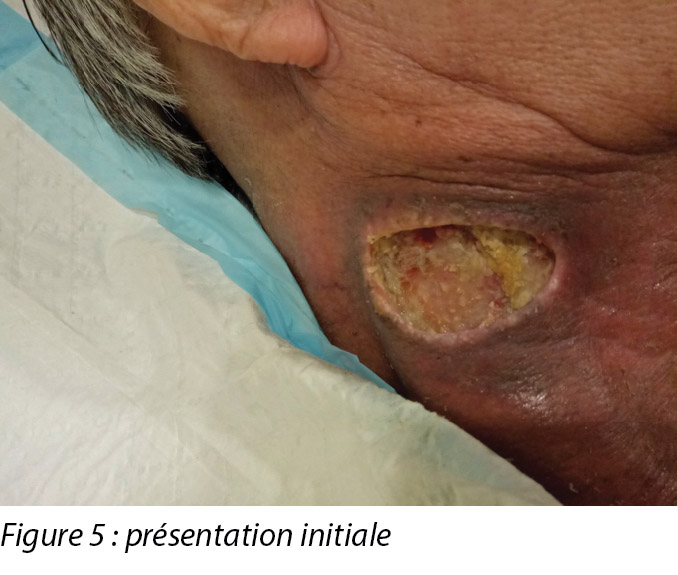

An initial assessment was done on 15 August 2016 in the wound specialist clinic in an acute tertiary hospital. The right sternocleidomastoid wound was a sloughy wound base that measured 3x4.5cm with a depth of 1cm and undermining from 12–2 o’clock to a length of 1cm (Figure 5). Periwound erythema, acute radiotherapy hyperpigmentation, and tenderness with a minimal amount of exudate was present. In addition, as the wound bed was near major neck vessels, sharp debridement was not considered an advisable option. As the patient needed to complete his prescribed radiotherapy treatment, plans were made for the initial management of his wound with a topical antimicrobial. Hence the patient was managed with daily povidone-iodine dressing as it was cost-effective and reduced the bioburden on the wound bed4.

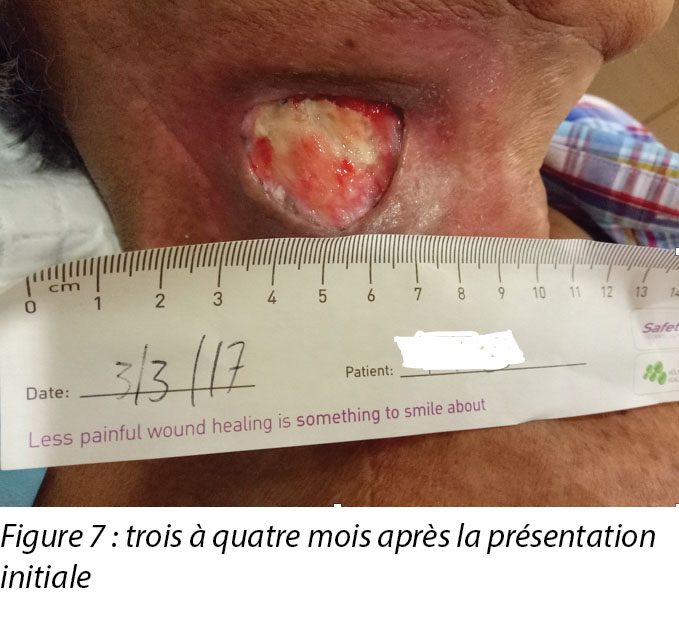

Upon completion of his oncology treatment 2 weeks later, reassessment of his wound was done (Figure 6). Wound measurements were 3x4.5cm with a 1cm depth. Minimal areas of granulation were noted, and the wound bed was mostly covered by adherent slough. Cleansing of the wound was done with normal saline. Mr B was initially started on Iodosorb® (New Zealand) cadexomer iodine powder then switched to cadexomer iodine ointment with Duoderm® CGF® (Denmark) hydrocolloid wafer as a secondary dressing to promote a moist wound healing environment4. As the wound progression was slow, after 3–4 months the treatment modality was switched to Askina® Calgitrol (United Kingdom), a silver gel, but this was stopped after 1 month as more fibrotic tissue was deposited on the wound bed (Figure 7). Mr B was then placed back on cadexomer iodine ointment with a hydrocolloid wafer. He was seen twice a week at the wound care clinic for careful debridement of loose devitalised tissue given the anatomy of major vessels around the wound bed. As the periwound skin was dry, Mr B was advised on the application of moisturiser daily.

Six months after the initial treatment and review, the wound bed measured 3x4cm with a wound depth of 0.5cm (Figure 8). Mr B continued twice weekly dressings at the wound clinic for debridement of loose devitalised tissue with Iodosorb® cadexomer iodine ointment and Duoderm® CGF® hydrocolloid (Denmark) dressing. Once all fibrotic tissue had been debrided and the wound bed was superficial, the patient continued with hydrocolloid wafer primarily to facilitate granulation4. Full epithelialisation occurred 1 year after the initial presentation.

Discussion

Winter’s study5 on wound epithelialisation in porcine models showed that for wound healing to occur, a combination of three factors must be considered – reduction of bacterial burden on the wound bed, vascularisation, and wound hydration. In addition, a recent paper included debridement and oedema management as crucial factors to consider in wound healing6. Understanding these principles, combined with the usage of the triangle of wound assessment tool, aided wound clinicians in developing a patient-centric treatment plan which guided their choice of dressing products for these two cases7.

In the case of Mr A, his wound bed was the exposed periosteum which was devoid of blood supply8. The exudate level on this wound bed provided enough moisture for wound healing and was not excessive. Mr A’s wound did not present with any signs of local, spreading nor systemic infection. The wound edges consisted of hypertrophic tissue3. The temporal region, which was covered with hair, was the periwound area. The periwound skin condition was healthy, with no signs of eczema, maceration nor dehydration. The management plan was therefore to: promote granulation from the edges to close the wound; shear the hypertrophic tissue at the wound edge; and protect the wound bed from external sources of infection that can occur with non-adherence of the secondary dressing. The wound presentation narrowed down the dressing product selection to the ones that could promote angiogenesis and granulation such as collagen2.

The outer layer of the periosteum is cell poor; hence, epithelial advancement is challenging in such a wound bed due to the lack of blood supply and viable tissue for collagen synthesis9. Elastase, which activates matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs), is often present in such non-healing wounds3. It inhibits the extracellular matrix components of elastin and collagen by binding and depleting collagen levels within the wound bed. This resulted in the extracellular matrix degrading and a reduction in fibroblast levels crucial in the proliferative phase for wound healing3. Using a collagen dressing can disrupt the elastase levels, reducing MMP levels by binding to growth factors and further inactivating MMPs on the wound bed3. Also, using a collagen dressing can improve the deposition of new collagen within the wound bed, as fibroblast and macrophages anchor well to the three-dimensional collagen structure. This can propel the wound from the inflammatory to the proliferative phase, initiating angiogenesis3. Lastly, it stimulates cellular migration by providing a moist wound environment and fluid balance within the wound bed3.

Conservative sharp debridement was done for hypertrophic tissue at the wound edges periodically for easier cell migration laterally2. The application of a secondary dressing was challenging; hence shaving of the temporal region was necessary for better visualisation and to prevent foreign bodies such as hair from contaminating the wound bed10. Sebum from hair follicles also made adherence of secondary dressing difficult. Hence a layer of non-sting barrier spray was applied to the periwound area before the application of any secondary dressing.

As for Mr B, the wound presentation differed as he continued on radiotherapy treatment. Initial wound presentation was a wound bed which was dry; the initial treatment goal post-incision and drainage was to reduce the bioburden on the wound bed. Subsequent assessment of his wound post-radiation therapy was a fibrotic, dry and sloughy wound bed. The wound edge and periwound skin were also dry. The management plan was to: rehydrate the wound bed, wound edge and periwound skin to promote a moist wound healing environment; debride the non-viable tissue; and keep the wound free from infection. Conservative sharp debridement was risky to undertake given the anatomical location of the wound and the proximity of large vessels at the sternocleidomastoid region, hence autolytic debridement was selected together with an antimicrobial product which continued to reduce the bioburden on the wound bed4.

With Mr B, the wound clinicians witnessed the early and delay effects of radiation therapy on wound healing, given its proximity to the sternocleidomastoid wound. The redness that Mr B had immediately post-radiation (shown in Figures 5 and 6 in the periwound region), was due to the dry desquamation caused by radiation therapy11. There was also alteration in all layers of tissue post-radiation therapy in which the dermis and subcutaneous tissue were progressively replaced by dense and fibrotic tissue. This was due to the irregularity in collagen fibrils caused by abnormalities in collagen production formed by fibroblasts and myofibroblasts11.

Cadexomer iodine ointment was selected for its antimicrobial and autolytic properties12. The occlusive nature of hydrocolloid dressings helped facilitate granulation and inhibited bacterial growth4. Mr B preferred the conformability and exudate absorption capability of hydrocolloid dressings. He was advised to apply moisturiser on his periwound skin as it was dry and caused him some itch and discomfort. Though the wound size is small, it took almost a year before Mr B could achieve full epithelialisation of his wound.

The triangle of wound assessment tool provided wound clinicians with a comprehensive look at the assessment of a wound so a suitable management plan could be developed. The tool was used in combination with the understanding of wound healing in irradiated areas or wound beds devoid of blood supply. It was also noted that it would be costly for patients if the clinicians were unable to select a dressing product for its intended purpose4. Armed with this information, the wound clinician and the patient were able to set realistic treatment goals and timeframes for healing.

Conclusion

A favourable outcome in wound closures for complex wounds by secondary intention is determined by understanding the challenges a complex wound can pose. The wound clinician can develop a realistic, patient-centric treatment plan and select the appropriate dressing product which is suitable for its intended purpose.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest involved in the studies.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Gestion des plaies complexes de la tête impliquant les muscles sterno-cléido-mastoïdiens et temporaux : une série de cas

Angela Yi Jia Liew and Yee Yee Chang

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.4.41-44

Résumé

L’utilisation d’un outil complet d’évaluation des plaies et la sélection appropriée de pansements peuvent aider les cliniciens à gérer des plaies complexes. Le présent article décrit les soins prodigués à deux patients présentant des plaies à la tête. Le premier cas est un patient ayant subi l’échec d’un lambeau du muscle temporal droit et dont le périoste était exposé suite à une large excision. Le second cas explore la gestion d’un abcès du muscle sterno-cléido-mastoïdien qui s’est développé au cours d’une radiothérapie pour un cancer du cou et de la tête. L’article décrit comment le choix d'une cicatrisation par deuxième intention peut éviter aux patients de subir des interventions chirurgicales supplémentaires dont les résultats ne sont pas toujours favorables.

Introduction

Les progrès médicaux dans la gestion des cancers de la tête et du cou offrent aux patients la flexibilité de choisir leur traitement. Cependant, certains facteurs comme des immunothérapies actives ou une résection chirurgicale précédente peuvent avoir un impact sur la guérison ou entraîner un du lit de plaie malsain.1 En outre, certains patients ne sont pas des candidats appropriés à une intervention chirurgicale ou préfèrent un traitement conservateur.

Cette série d’études de cas propose d’examiner deux cas dans le cadre desquels des pansements conventionnels ont été utilisés pour la fermeture de plaie. Le premier cas est celui d’un patient présentant un échec de greffe de peau mince du muscle temporal droit avec un crâne exposé après une large excision pour le traitement d’un carcinome basocellulaire. Le second cas est celui d’un patient qui a développé un abcès du cou dans la région du muscle sterno-cléido-mastoïdien lors d’une chimiothérapie et qui a subi une incision et un drainage. Ces deux cas ont été étudiés à l’aide du triangle de l’évaluation de la plaie qui a fourni aux cliniciens un guide d’évaluation holistique.2

Première étude de cas

Monsieur A., un Chinois âgé de 77 ans, s’est présenté, le 29 avril 2016, au service de consultation externe spécialisé tête et cou d’un hôpital de soins tertiaires aigus, avec une lésion du muscle temporal droit. La lésion était présente depuis sa naissance, mais il a remarqué que sa taille avait augmenté pour atteindre 1 x 3 cm après une blessure accidentelle chez le coiffeur deux ans auparavant. La lésion ne présentait aucun saignement par contact, aucun suintement et n’était pas douloureuse. Un examen de la tête et du cou n’a révélé aucun ganglion lymphatique cervical palpable. Monsieur A. a subi une biopsie-exérèse de la grosseur du muscle temporal droit en mai 2016. L’histologie a révélé un adénocarcinome apocrine et un carcinome basocellulaire provenant d’un kyste de nævus sébacé. Une tépographie n’a indiqué aucune accumulation significative de fluorodésoxyglucose (FDG) dans d’autres régions, mais M. A. a dû subir une excision plus large pour une ablation adéquate de la tumeur.

Le 23 mai 2016, M. A. a subi une large excision afin de recouvrir le périoste exposé à l’aide d’un lambeau de muscle temporal droit, suivie d’une greffe de peau mince pour recouvrir le lit de la plaie. La greffe de peau mince a été fixée à l’aide d’un pansement en mousse de polyuréthane et le patient a quitté l’hôpital 2 jours plus tard. Un premier examen de la plaie du lambeau du muscle temporal droit 10 jours plus tard a révélé que la greffe de peau mince avait bien pris. Toutefois, un examen de la plaie une semaine plus tard a révélé une nécrose humide sur les bords de la greffe de peau mince et une exposition du périoste. La plaie du patient a été traitée avec Aquacel® Ag (Royaume-Uni), un pansement hydrofibre contenant de l’argent, et par une autre intervention chirurgicale pour recouvrir le lambeau étant donné que la plaie restait stagnante malgré un changement de pansement tous les deux jours. Le chirurgien principal l’a orienté vers l’équipe de soins des plaies, car M. A. a refusé une intervention chirurgicale et préférait une approche conservative.

À l’inspection, la plaie du muscle temporal droit mesurait 3 x 5 cm avec une profondeur de 1 cm (voir la figure 1). Le lit de la plaie contenait le périoste exposé mesurant 2 x 3 cm avec une nécrose humide sur les bords de la plaie et des zones de peau greffée qui avaient pris. Aucun signe d’infection locale n’a été détecté. Les cheveux ont été rasés autour de la zone périlésionnelle pour assurer une bonne marge pour l’application du pansement. Les cliniciens de soins des plaies ont procédé à un débridement chirurgical conservateur du tissu dévitalisé sur les bords de la plaie. La plaie a été nettoyée avec une solution saline normale et a été pansée pour la première fois avec un pansement à couche de collagène (Heliaid®). Le patient a appris comment changer la gaze externe si elle était souillée pour contrôler l’exsudat.

Lors de sa consultation un mois plus tard, la plaie du patient présentait un tissu d’hypergranulation friable dans l’aspect inférieur du lit de la plaie (voir la figure 2). Une excision à ras utilisant une lame a été effectuée pour gérer le tissu d’hypergranulation chaque semaine et le pansement au collagène n’a été changé que s’il n’était pas dégradé car il servait d’échafaudage permettant au tissu de granulation de migrer et de recouvrir le périoste exposé.3

Un examen par le chirurgien trois mois plus tard a révélé une contraction des bords de la plaie, recouvrant le périoste (voir la figure 3). La granulation hypertrophique persistait sur les bords de la plaie et a nécessité une excision à ras périodique. Le pansement au collagène a été utilisé jusqu’à l’épithélialisation complète qui a eu lieu 5 mois après la première consultation avec l’équipe de soins des plaies (voir la figure 4).

Deuxième étude de cas

Monsieur B., un Chinois de 71 ans, qui avait subi une radiothérapie pour un carcinome squameux (CCS) de l’amygdale droite, s’est présenté aux urgences avec un abcès dans la région du muscle sterno-cléido-mastoïdien droit. Une tomodensitométrie (TDM) du cou a révélé le développement d’un abcès multiloculé sur toute l’étendue du muscle sterno-cléido-mastoïdien droit avec cellulite sus-jacente. Le patient a subi une incision et un drainage d’urgence de l’abcès. Du fait que M. B subissait une radiothérapie active et donc n’était pas candidat à une ablation chirurgicale du CCS, il a été orienté vers l’équipe de soins des plaies pour une gestion de suivi du site chirurgical.

Une première évaluation a été effectuée le 15 août 2016 dans la clinique spécialisée des plaies d’un hôpital de soins tertiaires aigus. La plaie du muscle sterno-cléido-mastoïdien était une base de plaie nécrosée mesurant 3 x 4,5 cm, d’une profondeur de 1 cm et creusante de 12 à 14 heures sur une longueur de 1 cm (voir la figure 5). On a noté la présence d’un érythème périlésionnel, d’une hyperpigmentation aiguë due à la radiothérapie, et d’une sensibilité avec une quantité minimale d’exsudat. En outre, du fait que le lit de la plaie se situait près d’importants vaisseaux du cou, un débridement chirurgical était déconseillé. Comme le patient devait poursuivre la radiothérapie prescrite, une gestion initiale de sa plaie avec un antimicrobien topique a été envisagée. Un pansement quotidien de povidone iodée a donc été utilisé, car il était économique et réduisait la charge microbienne du lit de la plaie.4

Une fois le traitement oncologique terminé deux semaines plus tard, une nouvelle évaluation de sa plaie a été effectuée (voir la figure 6). Les dimensions de la plaie étaient de 3 x 4,5 cm et 1 cm de profondeur. Des zones minimes de granulation ont été observées et le lit de la plaie était essentiellement recouvert de nécrose humide adhérente. La plaie a été nettoyée avec une solution saline normale. Monsieur B. a tout d’abord reçu de la poudre d’iode cadexomérique Lodosorb® (Nouvelle-Zélande), puis une pommade d’iode cadexomérique avec une plaque hydrocolloïde Duoderm® CGF® (Danemark) et comme pansement secondaire pour favoriser un environnement de cicatrisation de plaie humide.4 Comme la progression de la plaie était lente, la modalité de traitement a été modifiée après 3 ou 4 mois en faveur du gel d’argent Askina® Calgitrol (Royaume-Uni), mais a été abandonnée au bout d’un mois en raison d’une multiplication du tissu fibrotique sur le lit de la plaie (voir la figure 7). Monsieur B a ensuite de nouveau reçu une pommade d’iode cadexomérique avec une plaque hydrocolloïde. Il s’est rendu à la clinique de soin des plaies deux fois par semaine pour un débridement soigné du tissu dévitalisé lâche, étant donné l’anatomie des principaux vaisseaux autour du lit de la plaie. Comme la peau périlésionnelle était sèche, il lui a été conseillé d’appliquer une crème hydratante tous les jours.

Six mois après le traitement et l’examen initiaux, le lit de la plaie mesurait 3 x 4 cm avec une profondeur de 0,5 cm de la plaie (voir la figure 8). Monsieur B. a continué de recevoir deux pansements hebdomadaires à la clinique de soins des plaies pour le débridement du tissu dévitalisé lâche, avec la pommade d’iode cadexomérique Iodosorb® et le pansement hydrocolloïde Duoderm® CGF® (Danemark). Une fois tout le tissu fibrotique a été retiré et que le lit de la plaie était superficiel, le patient a continué d’utiliser une plaque hydrocolloïde essentiellement pour encourager la granulation.4 L’épithélialisation totale a été constatée un an après la première consultation.

Discussion

L’étude de Winter5 sur l’épithélialisation des plaies dans un modèle porcin a démontré que pour qu’une cicatrisation des plaies ait lieu, la combinaison de trois facteurs doit être prise en compte : la réduction de la charge bactérienne sur le lit de la plaie, la vascularisation et l’hydratation de la plaie. De plus, un article récent a inclus le débridement et la gestion de l’œdème comme facteurs essentiels dans la cicatrisation des plaies.6 La compréhension de ces principes, combinée à l’utilisation du triangle d’évaluation des plaies, a aidé les cliniciens de soins des plaies à élaborer un plan de traitement centré sur le patient qui a guidé leur choix en matière de pansements pour ces deux cas.7

Dans le cas de M. A, le lit de la plaie était le périoste exposé, qui n’était plus irrigué.8 Le taux d’exsudat sur le lit de la plaie assurait suffisamment pour la cicatrisation de la plaie et n’était pas excessif. La plaie de M. A. ne présentait pas de signes d’infection locale, systémique ou extensive. Les bords de la plaie étaient constitués de tissu hypertrophiques.3 La région temporale, recouverte de cheveux, correspondait à la région périlésionnelle. La peau périlésionnelle était saine, sans aucun signe d’eczéma, de macération ou de déshydratation. Le plan de gestion était donc le suivant : faciliter la granulation depuis les bords de la plaie pour la refermer, exciser à ras le tissu hypertrophique au bord de la plaie ; et protéger le lit de la plaie des sources externes d’infection pouvant survenir en raison du manque d’adhérence du pansement secondaire. La présentation de la plaie a limité le choix des pansements à ceux capables de stimuler l’angiogenèse et la granulation, comme les pansements au collagène.2

La couche externe du périoste est pauvre en cellules ; par conséquent, la progression épithéliale est difficile dans un tel lit de plaie en raison d’une mauvaise irrigation sanguine et de l’absence de tissu viable pour la synthèse du collagène.9 L’élastase, qui active la métalloprotéinase matricielle (MMP), est souvent présente dans ce type de plaies non cicatrisantes.3 Elle inhibe les composants de la matrice extracellulaire (élastine et collagène) en liant et en épuisant les niveaux de collagène dans le lit de la plaie. Il en résulte une dégradation de la matrice extracellulaire et une réduction des niveaux de fibroblastes essentiels à la phase proliférative de cicatrisation de la plaie.3 Un pansement au collagène risque de perturber les niveaux d’élastase, réduisant les niveaux de MPM en se liant aux facteurs de croissance et en inactivant la MPM sur le lit de la plaie.3 De même, l’utilisation d’un pansement au collagène peut accroître le dépôt de nouveau collagène dans le lit de la plaie, car le fibroblaste et les macrophages se fixent bien à la structure tridimensionnelle du collagène. Cela peut propulser la plaie de la phase inflammatoire à la phase proliférative, initiant ainsi l’angiogénèse.3 Pour finir, cela stimule la migration cellulaire en assurant un environnement de plaie humide et l’équilibre du fluide au sein du lit de la plaie.3

Un débridement chirurgical conservateur du tissu hypertrophique a été effectué périodiquement aux bords de la plaie afin de faciliter la migration latérale des cellules.2 La pose d’un pansement secondaire a présenté des difficultés ; il a donc fallu raser la région temporale afin de rendre la zone plus visible et d’empêcher la contamination du lit de la plaie par des corps étrangers tels que des cheveux.10 Le sébum des follicules pileux a également rendu l’adhérence du pansement secondaire difficile. Une couche protectrice d’agent non piquant a été pulvérisée sur la zone périlésionnelle avant l’application du pansement secondaire.

Comme pour M. B., la présentation était différente, car il poursuivait sa radiothérapie. La présentation initiale de la plaie était un lit de plaie sec ; l’objectif initial du traitement après l’incision et le drainage était de réduire la biocharge sur le lit de la plaie. Une évaluation de sa plaie après la radiothérapie était un lit de plaie fibrotique, sec, et fibrineux. Le bord de la plaie et la peau périlésionnelle étaient également secs. Le plan de gestion était le suivant : réhydratation du lit de la plaie, des bords de la plaie et de la peau périlésionnelle pour favoriser un environnement de cicatrisation de plaie humide ; débridement du tissu non viable ; et prévention des infections. Un débridement chirurgical conservateur était risqué vu l’emplacement anatomique de la plaie et sa proximité avec de gros vaisseaux de la région sterno-cléido-mastoïdienne. Un débridement autolytique a donc été sélectionné avec un produit antimicrobien qui a continué de réduire la charge microbienne du lit de la plaie.4

Dans le cas de M. B, les cliniciens de soin des plaies ont constaté les effets précoces et retardés de la radiothérapie sur la cicatrisation de la plaie, vu sa proximité avec la plaie sterno-cléido-mastoïdienne. Les rougeurs que présentait M. B immédiatement post-irradiation (illustrées dans les figures 5 et 6 dans la région périlésionnelle) étaient dues à une desquamation sèche causée par la radiothérapie.11 Il y avait également une altération de toutes les couches de tissu post-radiothérapie, le derme et le tissu sous-cutané ayant été progressivement remplacés par du tissu dense et fibrotique. Cela était dû à l’irrégularité des fibrilles de collagène causée par des anomalies de production de collagène formées par les fibroblastes et les myofibroblastes.11

La pommade d’iode cadexomérique a été choisie pour ses propriétés antimicrobiennes et autolytiques.12 La nature occlusive des pansements d’hydrocolloïde a contribué à faciliter la granulation et inhibé la prolifération bactérienne.4 Monsieur B. a préféré la conformabilité et la capacité d’absorption d’exsudat qu’offrent les pansements d’hydrocolloïde. Il lui a été conseillé d’appliquer une crème hydratante sur sa peau périlésionnelle, car elle était sèche et provoquait une gêne et des démangeaisons. Même si la plaie était de petite taille, M. B a dû patienter presque un an avant l’épithélialisation totale de sa plaie.

Le triangle d’outil d’évaluation de la plaie a fourni aux cliniciens de soins des plaies une vue globale de l’évaluation d’une plaie qui leur a permis de concevoir un plan de gestion adapté. Cet outil a été utilisé en combinaison avec une compréhension de la cicatrisation des plaies dans des zones irradiées ou des lits de plaie non irrigués. Il a également été noté que les patients seraient exposés à des frais si les cliniciens étaient incapables de sélectionner un pansement pour le but auquel il est destiné.4 Bien informés, le clinicien du soin des plaies et le patient ont pu fixer des objectifs de traitement et un calendrier de cicatrisation réalistes.

Conclusion

Une issue favorable dans le domaine de la fermeture de plaies complexes par deuxième intention dépend d’une bonne compréhension des défis que présentent les plaies complexes. Le clinicien de soins des plaies doit élaborer un plan de traitement réaliste centré sur le patient, et sélectionner le pansement adapté qui permettra d’obtenir les résultats souhaités.

Conflit d’intérêts

Les auteurs déclarent n’avoir aucun conflit d’intérêts avec ces études.

Financement

Les auteurs n’ont reçu aucun financement pour cette étude.

Author(s)

Angela Yi Jia Liew*

RN, CWOCN

Assistant Nurse Clinician, Division of Nursing, Speciality Nursing (Wound Care), Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Email Angela.liew.y.j@sgh.com.sg

Yee Yee Chang

MN, RN, CWOCN

Nurse Clinician, Division of Nursing, Speciality Nursing (Wound Care), Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

* Corresponding author

References

- Coskun H, Erisen L, Basut O. Factors affecting wound infection rates in head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Neck Surg [Internet]. 2000;123(3):328–33.

- Dowsett C, Protz K, Drouard M, Harding K. Triangle of wound assessment made easy. Wounds Asia [Internet]. 2015;1–6.

- Fleck CA, Simman R. Modern collagen wound dressings: function and purpose. J Am Col Certif Wound Spec [Internet]. 2010;2(3):50–4.

- Vowden K, Vowden P. Wound dressings: principles and practice. Surg (UK) [Internet]. 2017;35(9):489–94.

- Winter GD. Some factors affecting skin and wound healing. J Tissue Viability [Internet]. 2006;16(2):20–3.

- Jones J. Winter’s concept of moist wound healing: a review of the evidence and impact on clinical practice. J Wound Care 2005;14(6):273–6.

- Baranoski S, Ayello EA. Wound dressings: an evolving art and science. Adv Ski Wound Care 2012;25(2):87–92.

- Dwek JR. The periosteum: what is it, where is it, and what mimics it in its absence? Skeletal Radiol 2010;39(4):319–23.

- Agarwal A, Andrew LE, Ayello EA, Baranoski S, Bates-Jensen BM, Bauer C, et al. Chapter two: wound healing. In: Doughty DB, McNichol L, editors. Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses SocietyTM core curriculum: wound management. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2016. p. 24–68.

- Sebastian S. Does preoperative scalp shaving result in fewer postoperative wound infections when compared with no scalp shaving? A systematic review. J Neurosci Nurs [Internet]. 2012;44(3):149–56.

- Wang J, Boerma M, Fu Q, Hauer-Jensen M. Radiation responses in skin and connective tissues: effect on wound healing and surgical outcome. Hernia 2006;10(6):502–6.

- Sandoz H, Swanson T, Weir D, Schultz G. Biofilm-based wound care with cadexomer iodine. Wounds Int [Internet]. 2017;(November):1–6.