Volume 42 Number 3

A consensus on stomal, parastomal and peristomal complications

Keryln Carville, Emily Haesler, Tania Norman, Pat Walls and Leanne Monterosso

Keywords stomal, parastomal, peristomal

For referencing Carville K et al. A consensus on stomal, parastomal and peristomal complications. WCET® Journal 2022;42(3):12-22

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.3.12-22

Submitted 1 May 2022

Accepted 10 July 2022

Abstract

Aim To establish a consensus on terminology used to define stomal, parastomal and peristomal complications in Australia.

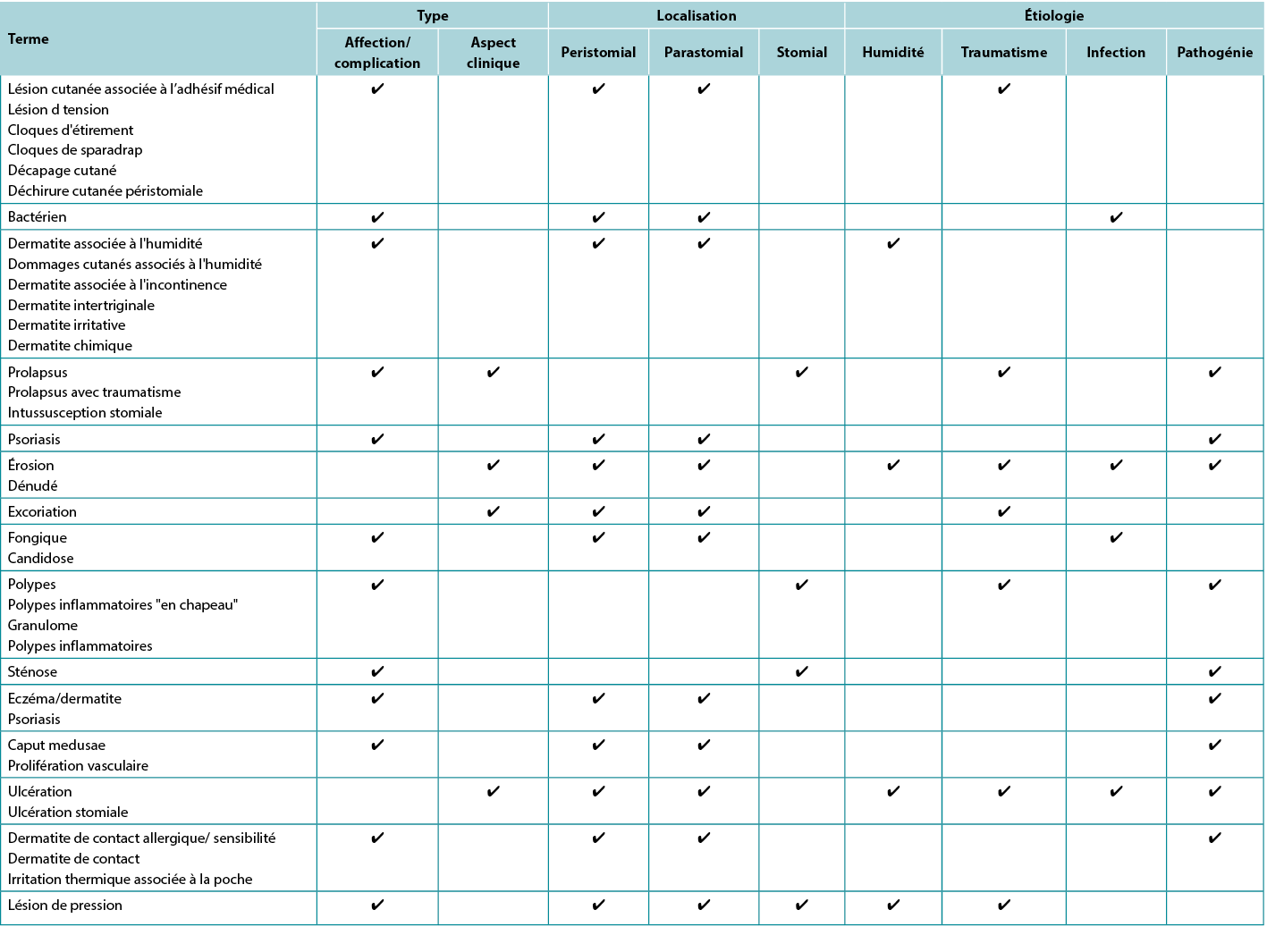

Methods A list of stomal, parastomal and peristomal complications was generated through group dialogue which was informed by the clinical and academic knowledge of the researchers. An extensive literature review was undertaken to identify any additional terms and to create a database of definitions/descriptions. A library of images related to the identified conditions was generated. An online Delphi process was conducted amongst a representative, purposive sample of Australia expert wound, ostomy, continence nurses (WOCNs) and colorectal surgeons. Ten terms were presented to the panel with descriptive photographs of each complication. Up to three Delphi rounds, and if necessary a priority voting round, were conducted.

Results Seven of the ten terms reached agreement in the first round. One term (allergic dermatitis) was refined (allergic contact dermatitis) and reached agreement in the second round. Two terms (mucocutaneous granuloma and mucosal granuloma) were considered by the panel to be the same condition in different anatomical locations and were combined as one term (granuloma). Two terms (skin stripping and tension blisters) were combined as one term – medical adhesive related skin injury (MARSI) – and reached agreement in round two.

Conclusion A consensus in terminology used to describe stomal, para/peristomal complications will enhance communication amongst patients and health professionals, and advance opportunities for education and benchmarking of stomal, para and peristomal complications nationally.

Introduction

Surgery that results in an enteric or urinary stoma is usually performed following a diagnosis of malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, neurogenic disorders, congenital abnormality, trauma or to rest a distal surgical anastomosis1. There are approximately 47,000 persons living with a stoma in Australia2 and this number swells to 100,000 in the United Kingdom3 and 1,000,000 in the United States of America (USA) where 130,000 related surgical procedures are performed annually4.

Regardless of the type of stoma and its method of management, the postoperative recovery and rehabilitation of a person who has undergone faecal or urinary diversion surgery is very much dependent upon their ability to avoid stomal, parastomal or peristomal skin complications5. Peristomal refers to the skin circumferential to the stoma and parastomal refers to the skin at the side of the stoma, but in both instances it relates to skin covered by the ostomy appliance skin barrier1,3.

The prevalence of stomal, parastomal and peristomal skin complications following stoma surgery varies widely due to study designs, heterogeneous populations, sample sizes, types of stomas studied (that is enteric or urinary), types of complications under review and differences in definitions and terminologies used to describe them4–8. However, the extent of this disparity is evident in the literature which reports stomal and peristomal complications range between 6%9 to 80%4. Moreover, these complications differ clinically and are subject to the type of stoma created and whether the surgery was elective or emergent, the latter being responsible for a greater number of complications10–12.

It appears that there are higher complication rates amongst patients with enteric stomas such as ileostomies, particularly loop ileostomies, which were found by Park et al.9 to be up to 75% as compared to 6% amongst patients with end colostomies. However, Wood et al.13 found 34.4% of patients who had an ileal conduit created experienced stomal complications and 25% of this cohort required surgery for treatment of herniation or stomal retraction. Park et al.9 conducted a 19-year retrospective medical chart audit on 1,616 patients and determined the reasons for the stomal complications in their cohort were: patient age; surgical discipline performing the procedure, that is colorectal surgeon versus general surgeon; surgical procedure performed; and that no preoperative siting of the stoma by a wound, ostomy, continence nurse (WOCN) occurred9. Kann14 reported patient obesity and inflammatory bowel disease to be independent predictors of stoma-related complications in his review.

A lack of consensus in definitions and terminology has long been a hindrance to communication between health professionals, patients and formal and informal carers. Furthermore, disparities in definitions and terminology potentially leads to less than optimal care and lost opportunities for benchmarking care outcomes. In an attempt to investigate this anomaly, Colwell and Beitz7 undertook a survey amongst 686 WOCNs in the USA to establish content validity of published stomal and peristomal complication definitions and related interventions. Although they found a strong level of content validity for definitions of stomal and peristomal complications, they failed to do so for the related management interventions. Moreover, the respondents identified a considerable number of omitted stomal and peristomal complications, especially amongst neonatal and paediatric populations, which indicates a greater diversity in definitions and terminology used across clinical settings7.

Walls conducted a survey in 2017 in Australia to determine the use and agreement on definitions and terminology for peristomal skin conditions and clinical presentations amongst 191 stomal therapy nurses (STNs) who are synonymous with WOCNs. She also found great disparity in definitions and terminology used15. Wall’s study, like that of Colwell and Beitz, alerted WOCNs to the need for a national consensus on stomal and para/peristomal complications; however, until now there has been little endeavour to facilitate this initiative7,14. This is particularly relevant when one considers the significant burden associated with stomal and peristomal skin conditions. Taneja et al.16 found that patients with peristomal skin complications had increased readmission rates and a mean increased healthcare cost of US$7400 which equates to A$11,654 as compared to those without complications.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to establish an Australian consensus on terminology used to define stomal, parastomal and peristomal complications.

Methods

The study comprised the scoping and prioritising of terminology used by Australian WOCNs to describe stomal, parastomal and peristomal complications. A literature review was undertaken to define these terms, and an online Delphi process was conducted amongst expert Australian WOCNs and colorectal surgeons to gain a consensus of the related definitions and terminology used. Ethics approval was granted by Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2020-0441) and the University of Notre Dame Australia Human Research Ethics Committee and all institutional guidelines were followed.

First, the research team generated a list of potential stomal, parastomal and peristomal complications of interest through group dialogue informed by clinical and academic knowledge of the researchers (Appendix 1). After generating the list of complications, an extensive literature review was undertaken to identify any additional terms found to be associated with stomal, para/peristomal complications and to create a database of definitions/descriptions for each of those identified. Next, indicative clinical photographs were collected from participating researchers and health services, with the consent of the individuals involved. Finally, the research term reviewed the list of complications to select those for which there was sufficient variation in terminology and/or understanding either clinically and/or in the literature.

To achieve national agreement on the most acceptable term and definition/description for each complication, a Delphi process involving WOCN experts and colorectal surgeons was undertaken using a project-specific online platform. Recruitment was via an open invitation and was disseminated by the Association of Stomal Therapy Nurses (AASTN) Inc. and to networks of the researchers. Respondents to the invitation were evaluated as expert in the field using Benner’s Novice to Expert Theoretical explanation of expertise17, with duration of clinical experience, professional appointment within the domain, publication/presentations and peer acknowledgement used to define expertise. From the pool of respondents, 20 participants from Australian States and Territories were selected and sent an email participant information sheet that included information on the anonymous nature of participant responses in the consensus process. All invited respondents agreed to participate and confirmed consent on accessing the online Delphi process platform.

The process to achieve consensus definitions consisted of four rounds – three Delphi rounds and a priority voting round. The Delphi consensus rounds were conducted using the RAND Appropriateness Method, a methodology designed to assist a panel to reach agreement18. Validity, reliability and application of the method is previously reported18–21. The online platform was designed to apply the RAND/UCLA method to calculate voting results. In the first round, each complication was presented with:

- Photographs of the complication.

- A range of terms commonly used to describe that complication, with one term identified as used most often in the Australian context presented as the nominal term for the complication.

- A definition/description derived from the literature.

Participants were asked to nominate their level of agreement with using the nominated term and their level of agreement with the definition using a 9-point Likert scale. Participants also provided a written justification indicating the reasoning behind their level of agreement, as well as suggested improvements for the definition.

The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method18 uses a 9-point Likert scale with tertiles representing agreement, uncertainty or disagreement. The scale included descriptors (tertile one: strongly agree, agree, weakly agree; tertile two: uncertain leaning toward agree, uncertain, uncertain leaning toward disagree; tertile three: weakly disagree, disagree and strongly disagree) to indicate the direction and strength of participant’s opinion. The vote outcome was calculated by transferring the Likert scale points to a corresponding numerical value, with the median Likert scale agreement score taken as the result. The RAND Appropriateness Method was used to determine if consensus was reached18. The 30% to 70% interpercentile range (IPR) was calculated, along with the IPR adjustment for symmetry (IPRAS). The IPRAS is a linear function of the distance of the IPR centre-point (IPRCP) from the centre-point of the Likert scale (5.0). If the IPRAS was higher than, or equal to, the magnitude of the IPR, then agreement was reached. However, an IPRAS value lower than the IPR magnitude indicated no panel agreement18. When the panel reached agreement, and the comments indicated that no improvements could be made to the definition/description, it was accepted as the consensus description.

If consensus was not reached, or if comments suggested that improvements to the definition could be made, a summary of the panel’s reasoning statements was compiled by grouping commentary in dis/agreement or neutral to the definition. The research team then adjusted the definition to incorporate improvements suggested by the panel. For the next consensus round, participants were presented with the refined definition, together with the outcome and summary of comments from the previous round. A maximum of three consensus rounds was considered a feasible number of votes over which to maintain participant engagement20,21.

For some terms, multiple definitions reached consensus agreement. Where the voting results indicated a group preference, that definition was selected. Where no clear group preference was evident, a final priority ranking round was undertaken. In this round, participants were presented with all definitions reaching agreement plus a final definition/description derived from the last round of comments. Participants ranked the definitions/descriptions from most to least preferred. The preferred definition was calculated using a nominal group multi-voting method using weighted ranking scores. The method, which was based on a review of nominal voting methods, is previously reported21.

Results

Following a nationally disseminated invitation to participate, 20 applicants were invited and accepted. The participants had backgrounds in wound, ostomy, continence nursing or colorectal surgery, with 18 participants having more than 10 years’ experience in their respective disciplines. Participation in individual rounds ranged from 13 to 20 panel members.

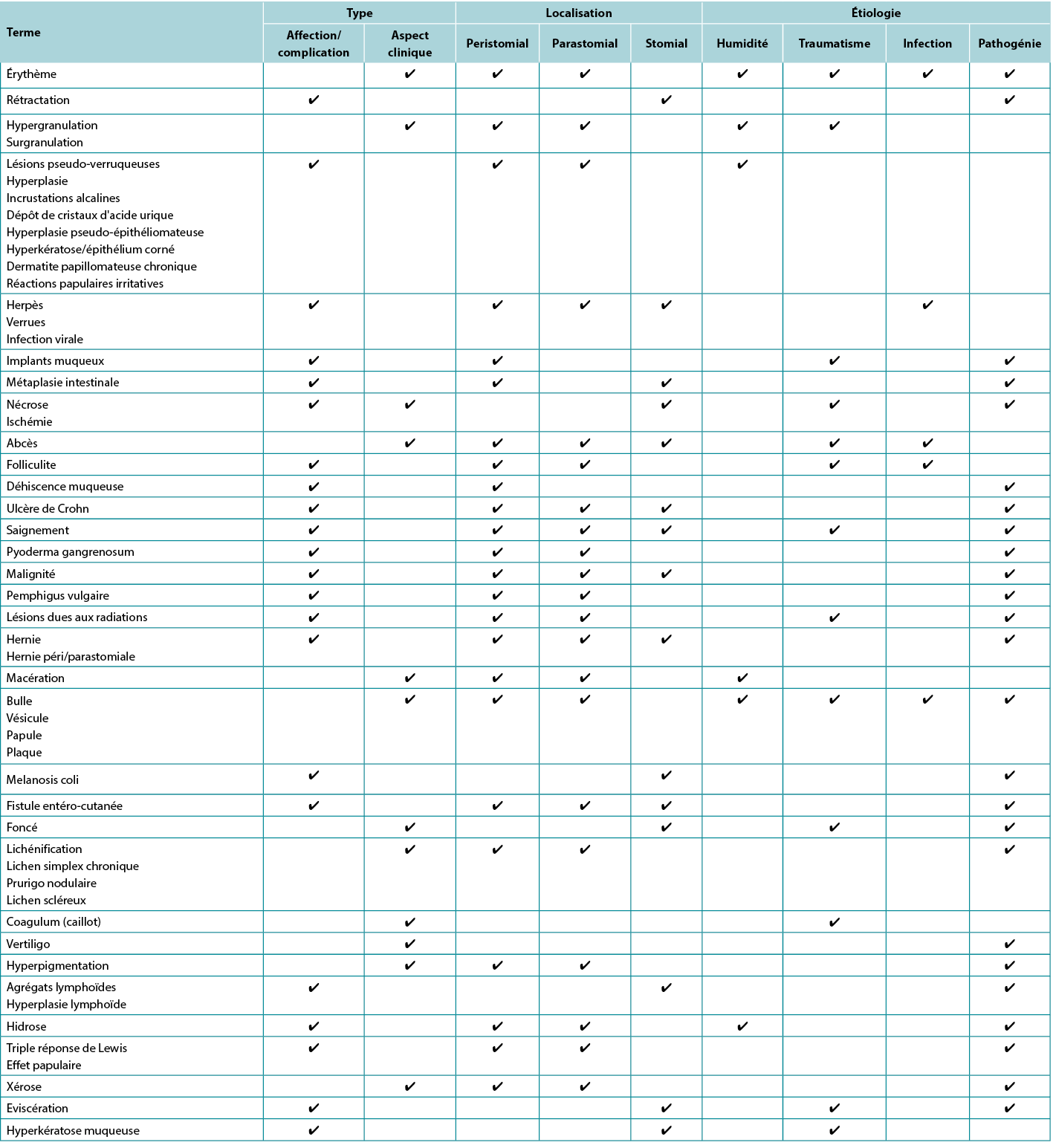

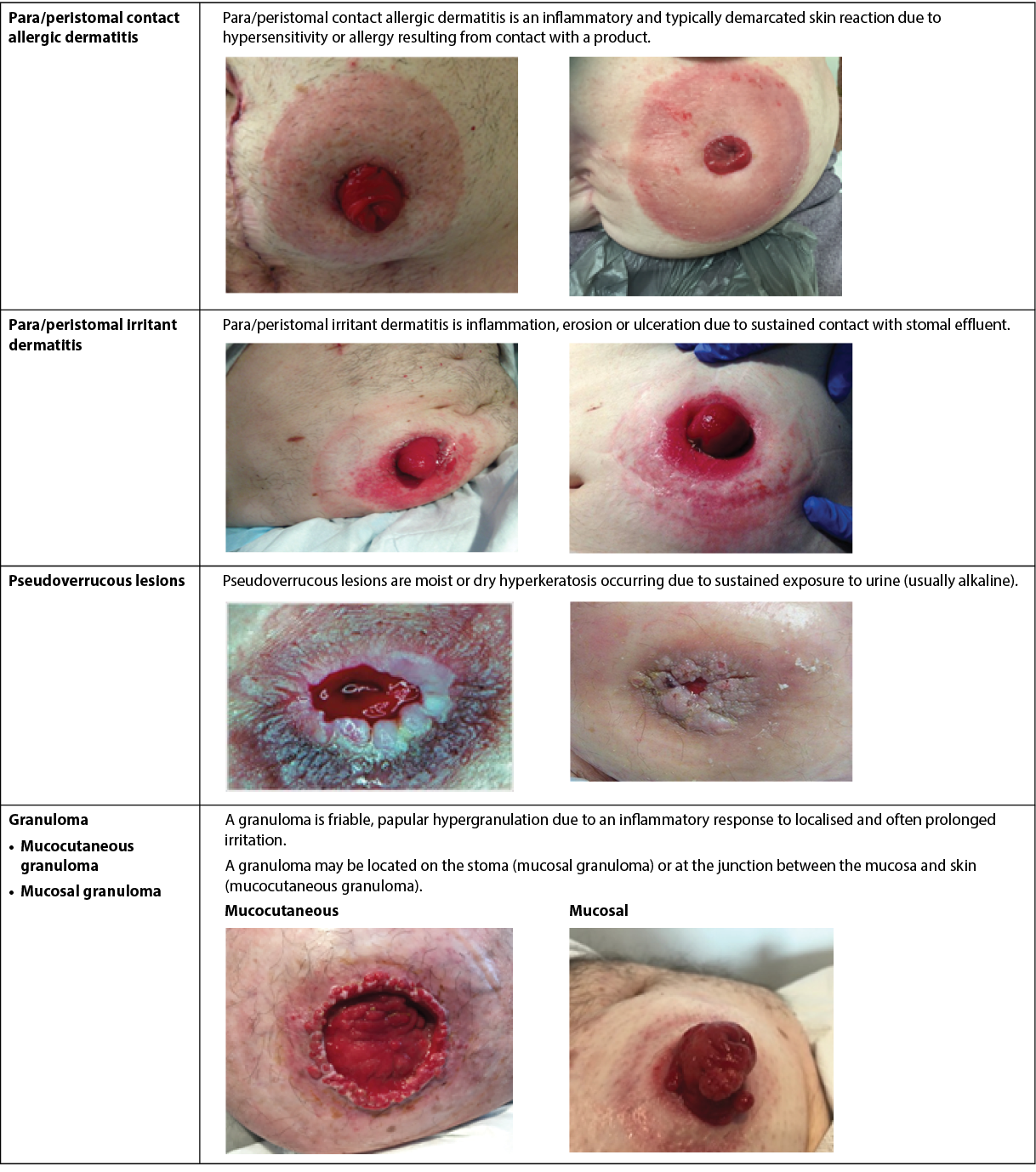

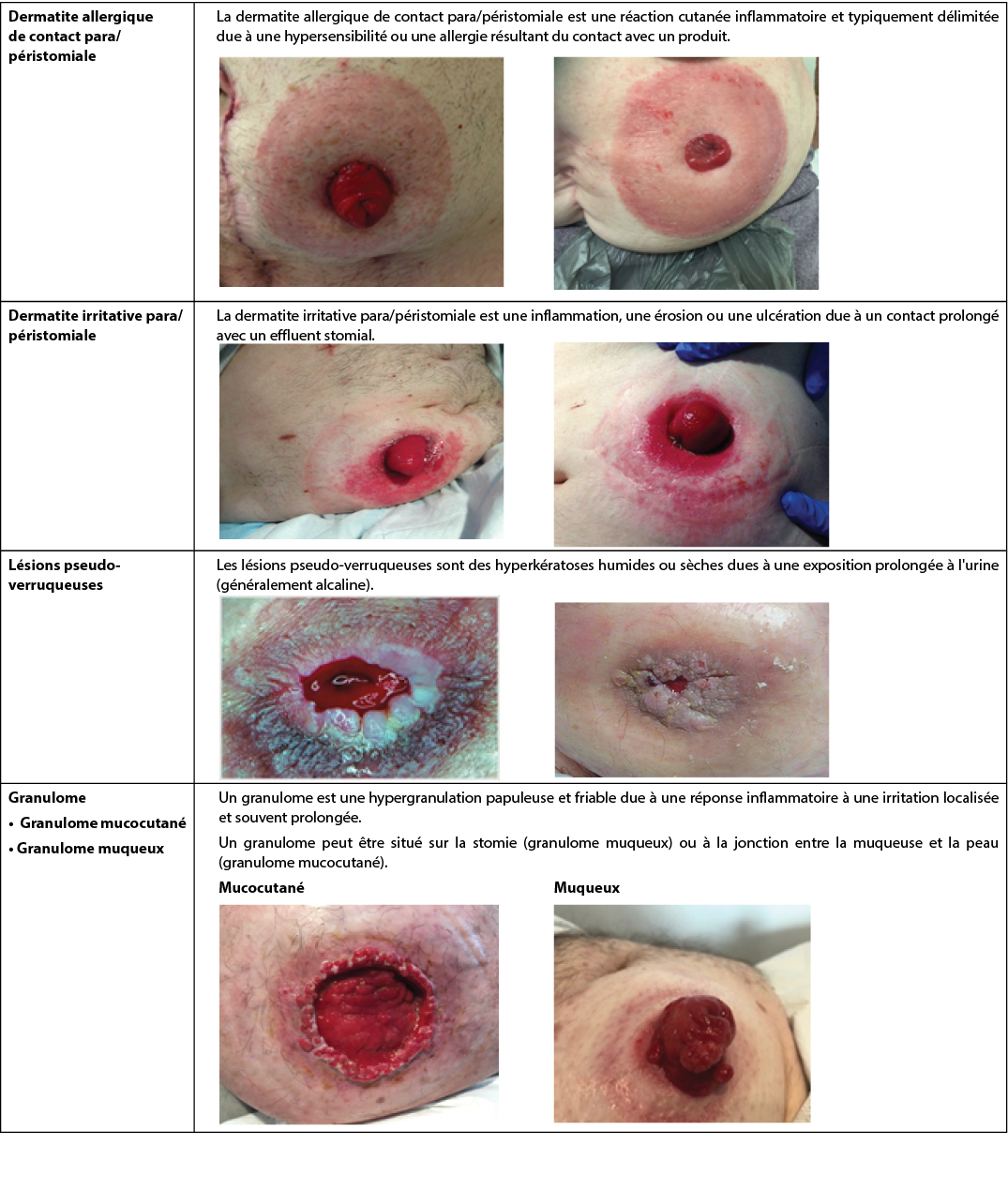

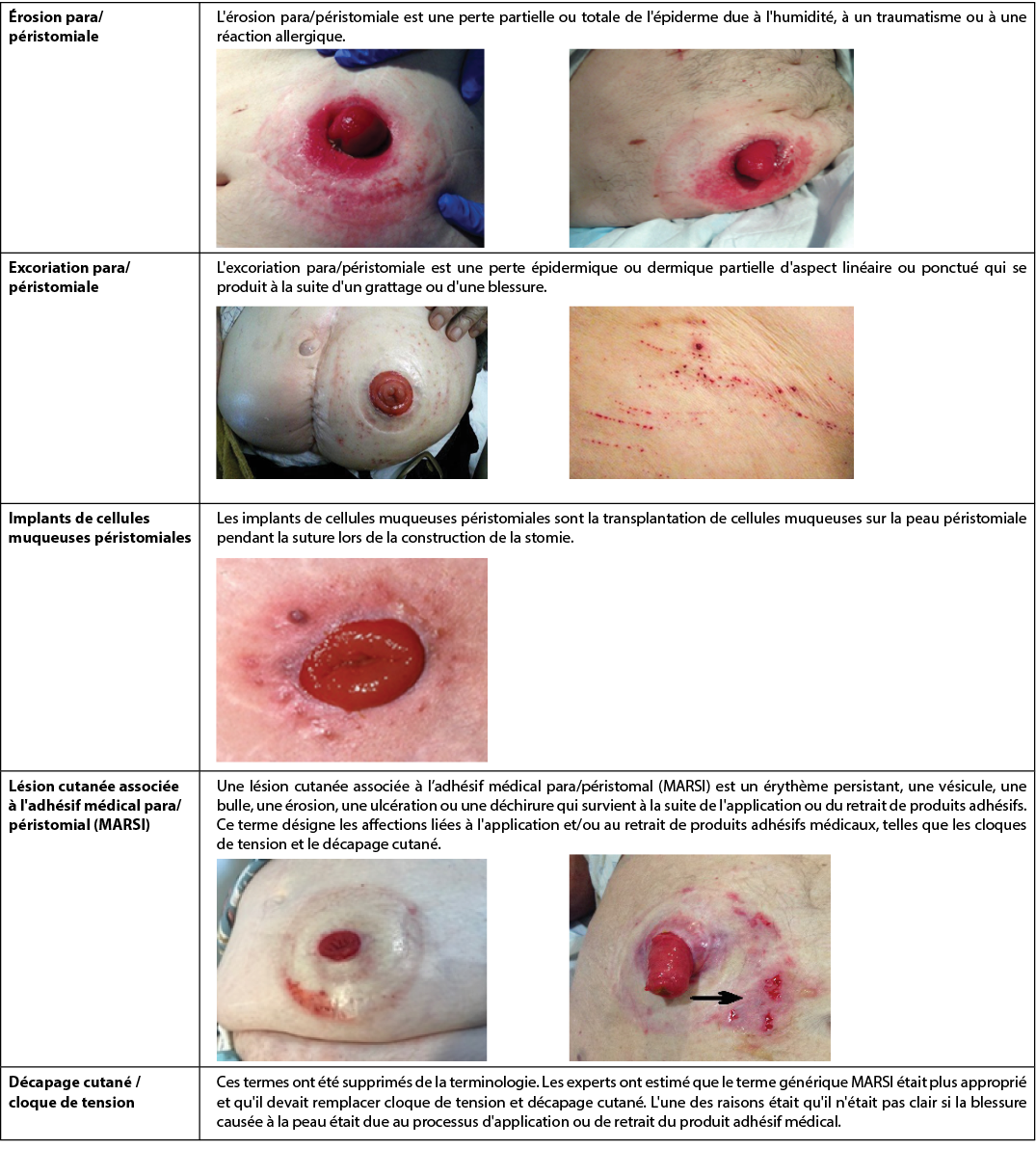

Ten terms were presented to the panel, seven of which reached agreement in the first round. One term (allergic dermatitis) was refined (allergic contact dermatitis) and reached agreement in the second round. Two terms (mucocutaneous granuloma and mucosal granuloma) were considered by the panel to be the same condition in different anatomical locations and were combined as one term (granuloma). Two terms (skin stripping and tension blisters) were combined as one term – medical adhesive related skin injury (MARSI) – that reached agreement in round two. The final glossary (Figure 1) includes eight terms for which definitions were agreed.

Figure 1. Australian consensus glossary terms for stomal complications.

All photos are used with permission, © the authors

Most vote outcomes achieved consensus in agreement with the presented definition. Agreement ranged from 55.56% to 98.95% in the first consensus round (ten terms), 56.25% to 81.25% in the second round (seven terms) and 55.0% to 80.0% in the third round (four terms). For all terms, consensus in agreement with the presented definitions/descriptions was achieved in every round, although respondents’ comments frequently indicated that improvements on the definition could be made. No clear preference for definitions/descriptions was evident for three terms (irritant dermatitis, granuloma, excoriation), leading to their inclusion in the priority ranking round.

Discussion

The skin, which is comprised of the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis, is a dynamic and responsive organ to external stimuli or wounding. The skin sustains homeostasis, structural integrity and cosmesis, whilst the stratum corneum or outer layer of the epidermis optimises the skin barrier function to protect against external environmental stressors such as exposure to maceration or desiccation and chemical and mechanical trauma22. Furthermore, the skin fulfils a pivotal role as an immunological barrier due to its innate and adaptive immune responses to pathogens. This response is significantly aided by the pH of the skin which ranges between 4.1–5.8 and is referred to as the acid mantle23. The acidic pH of the skin not only discourages bacterial colonisation and reduces the risk of opportunistic infection, but plays a role in the regulation of skin barrier function, lipid synthesis and aggregation, epidermal differentiation and desquamation24. Dysfunction of the skin barrier function impairs skin protection against mechanical trauma such as removal of adhesive agents, chemical trauma from irritants found in body effluent, and invasion of microorganisms. Resultant loss of skin integrity causes pain, impaired quality of life and challenges to one’s perception of bodily cosmesis.

For many, perceptions of cosmesis and alterations in body image are further challenged by the creation of a stoma. Increased morbidity in the form of stomal, para/peristomal complications is frequently associated with the creation of a urinary or faecal stoma12,25,26. The rate of para/peristomal and stomal complications varies significantly and is reported to be 20–80%4–6,26.

Interestingly, the type of stomal complication differs with occurrences within the first 30 days postoperative (referred to as early complications) or after 30 days (referred to as late complications)10–12,27-29. Early stomal complications described in the literature include stomal ischaemia/necrosis, retraction, mucocutaneous dehiscence, and parastomal abscess, which are primarily related to impaired perfusion, surgical technique or infection10–12,14. Late stomal complications are more commonly parastomal hernia, stomal prolapse, retraction and stenosis12,28–30.

However, the most significant peristomal skin complication in both the early and late postoperative periods is contact irritant dermatitis due to peristomal skin exposure to body effluent3,9,12,31. Contact irritant dermatitis was found by 91% (n=919) of international surveyed nurses as the most common peristomal skin complication in their practice32. Synonymous terms such as skin irritation9,32, chemical irritant dermatitis11, irritant dermatitis10,11, peristomal dermatitis3, moisture-associated skin damage (MASD)4 and peristomal moisture-associated skin damage (PSMASD)33,34 are used by some authors to define this condition. Regardless of terminology, the skin erosion and ulceration that results from repeated contact with bodily effluent due to ineffectual appliances leads to pain, negative body image, decreased health related quality of life and health utility and increased care costs35,36. Peristomal skin complications are reported to account for 40% of patient contact visits with a WOCN35.

Other peristomal skin conditions found to be problematic in the literature include contact allergic dermatitis, atypical pathological conditions such as varices and pyoderma gangrenosum and mechanical skin trauma7,12,30,32,33. Again, the literature reveals inconsistency in terminology as several synonymous terms are used by health professionals to describe mechanical skin trauma, including skin stripping4, skin tear4, medical adhesive related skin injury (MARSI)37, peristomal MARSI (pMARSI)4,33 and tension injuries or blisters4,33.

It was the lack of consensus in terminology/definitions for stomal and para/peristomal complications that were to be found in clinical practice and the literature that led to the researchers undertaking this study, which built upon the study conducted by Walls15 and which sought to achieve a consensus in stomal and para/peristomal terminology amongst Australian health professionals. The need for such a consensus was even more apparent following the researchers’ literature search which identified eight different definitions for ‘contact irritant dermatitis’3,4,26,38–42 and another three for ‘chemical irritation’3,41,43 and six more for ‘moisture-associated skin damage/peristomal moisture-associated skin damage’44–49. In effect, there were 17 definitions/descriptors for what could be considered synonymous terms for para/peristomal loss of skin integrity due to exposure to moisture/effluent.

Similar confusion in terminology was found for para/peristomal clinical presentations related to mechanical trauma such as medical adhesive related skin injury (pMARSI) (eight definitions)1,4,15,25,38,39,43,50 and tension blisters (three definitions)4,37,38 and infective skin conditions such as folliculitis (seven definitions)3,4,26,37,40,42,51. Pseudoverrucous lesions, also referred to as pseudoepitheliomaous hyperplasia and chronic papillomatous dermatitis, scored eight definitions1,3,11,40–42,52,53. In fact, the literature search revealed on average three to five definitions/descriptors for each para/peristomal skin complication terms searched.

Conversely, the literature revealed a more succinct agreement in regard to terms used to describe the majority of potential stomal complications such as retraction, stenosis, prolapse or metaplastic conditions. Similar agreement was found for para/peristomal pathological alterations in skin integrity such as pyoderma gangrenosum, mucosal implants, caput medusa/varices, eczema, psoriasis. Therefore, the ten terms ultimately included in the Delphi process were those found to have a higher number of definitions/descriptors used to describe stomal, para/peristomal complications as used by WOCNs. Amongst these there were three terms – para/peristomal irritant dermatitis, granuloma and excoriation – that required three voting rounds and a priority ranking voting round to reach consensus in definitions.

Para/peristomal irritant dermatitis was ultimately defined as “inflammation, erosion or ulceration due to sustained contact with stomal effluent”. However, the participants’ responses that ultimately led to this consensus were initially varied and led to significant discussion during the voting rounds.

A similar journey to consensus was found during the early voting rounds for granulomas which was defined as “friable, papular, hypergranulation occurring on the mucocutaneous junction/on the stoma, due to an inflammatory response to localised and often prolonged irritation”.

Para/peristomal excoriation was perhaps the most contentious term and the journey to this consensus was peppered with many comments, including the following:

I do agree with the definition of excoriation being linear, superficial loss of epidermis to the peristomal (skin) from scratching. However, I thought moisture was also involved with the presentation of excoriation.

I think the most important part in this definition is using the word ‘linear’ which depicts a scratch line.

I see no difference between ‘erosion’ and ‘excoriation’ – they have the same causative factors and there is nothing about ‘excoriation’ that implies a linear morphology or artefactual cause.

[The final definition is] easy to understand for the general nurse who often confuses this term with moisture associated skin damage or IAD [incontinence associated dermatitis].

I like the addition of linear/ punctate and scratching / injury. People can associate with these descriptors.

Excoriation was ultimately defined as “epidermal or partial dermal loss with a linear or punctate appearance that occurs due to scratching or injury”.

Although two terms (skin stripping and tension blisters) were ultimately conceded to be MARSI and agreement was reached on the definition in round two, there was initial debate as to confusion or lack of awareness regarding this term, as evidenced by the following responses:

The term ‘skin stripping’ is the cause, not an assessment of the peristomal skin itself. The cause of the skin loss is due to the skin been torn or stripped. If this section is meaning to describe MARSI then this should probably be reflected in the name.

When the term MARSI was introduced, I didn’t know what it meant – I find the term skin stripping much clearer without extra information needed. The term ‘skin stripping’ also differentiates from skin tears.

Tension blister is the same as skin stripping because these are blisters related to tension forces caused by medical adhesive surfaces… As there is a blister present, I think it should be classified as a blister only; it may be from tension, but it may not be, for example, following removal of appliance and assessment there may be another reason identified as cause of blister.

The term describes the mechanism in the term and suggests the treatment strategy. Technically it could also be classified under MARSI. I’ve never heard the phrase, but it reflects well how the blister occurred thus leading to effective management/prevention early.

Ultimately, skin stripping and tension blisters were seen to be synonymous with MARSI and the latter definition reached consensus.

Conclusion

A literature review and discussion with expert WOCNs identified lack of consensus in definitions/descriptors used to define common stomal, para and peristomal skin complications in Australia. A Delphi process was undertaken and ten terms were presented to 20 panel members who participated in voting rounds. The resultant consensus for definitions was achieved for eight terms. Mucocutaneous granuloma and mucosal granuloma were considered to be synonymous, as was skin stripping, tension blisters and MARSI. The results of this study are now being disseminated nationally and it is the researchers’ hope that WOCNs in other countries will take up the challenge and replicate the study methodology to enable a wider international consensus on terminology. Such a consensus will afford opportunities for communication amongst health professionals and patients, education and benchmarking of stomal, para and peristomal complications internationally.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with gratitude: the research grant awarded by the Australian Association of Stomal Therapy Nurses (AASTN) that enabled this study; the stomal therapy nurses and colorectal surgeons who participated in the Delphi process and willingly gave of their time and expertise; Paul Haesler, who designed and managed the project-specific online consensus voting platform.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Un consensus sur les complications stomiales, parastomiales et péristomiales

Keryln Carville, Emily Haesler, Tania Norman, Pat Walls and Leanne Monterosso

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.3.12-22

Résumé

Objectif Établir un consensus sur la terminologie utilisée pour définir les complications stomiales, parastomiales et péristomiales en Australie.

Méthodes Une liste de complications stomiales, parastomiales et péristomiales a été générée par le biais d'un dialogue de groupe éclairé par les connaissances cliniques et universitaires des chercheurs. Un examen extensif de la littérature a été entrepris afin d'identifier tout terme supplémentaire et de créer une base de données de définitions/descriptions. Une bibliothèque d'images associées aux conditions identifiées a été générée. Un processus Delphi en ligne a été mené auprès d'un échantillon représentatif et ciblé d’infirmières et infirmiers spécialisés dans les plaies, les stomies et la continence (WOCN) ou entérostoma-thérapeutes (IET) et de chirurgiens colorectaux australiens. Dix termes ont été présentés au panel avec des photographies descriptives de chaque complication. Jusqu'à trois tours Delphi, et si nécessaire un tour de s prioritaire, ont été menés.

Résultats Sept des dix termes ont fait l’objet d’un accord dès le premier tour. Un terme (dermatite allergique) a été affiné (dermatite de contact allergique) et a fait l'objet d'un accord lors du deuxième tour. Deux termes (granulome mucocutané et granulome muqueux) ont été considérés par le panel comme étant la même affection dans des localisations anatomiques différentes et ont été combinés en un seul terme (granulome). Deux termes (décapage cutané et cloques de tension) ont été combinés en un seul terme - MARSI (lésion cutanée associée à l’adhésif médical) - et ont fait l'objet d'un accord lors du deuxième tour.

Conclusion Un consensus sur la terminologie utilisée pour décrire les complications stomiales, para et péristomiales améliorera la communication entre les patients et les professionnels de santé, et fera progresser les possibilités de formation et d'évaluation comparative des complications stomiales, para et péristomiales au niveau national.

Introduction

La chirurgie créatrice d’entérostomies ou d’urostomies est généralement pratiquée à la suite d'un diagnostic de malignité, de maladie inflammatoire de l’intestin, de troubles neurogènes, d'anomalie congénitale, de traumatisme ou pour soulager une anastomose distale chirurgicale1. Il y a environ 47 000 personnes vivant avec une stomie en Australie2 et ce chiffre atteint 100 000 au Royaume-Uni3 et 1 million aux États-Unis d'Amérique (USA) où 130 000 procédures chirurgicales sont effectuées chaque année4.

Indépendamment du type de stomie et de sa méthode de prise en charge, la récupération et la réadaptation postopératoires d'une personne ayant subi une chirurgie de diversion fécale ou urinaire dépendent beaucoup de sa capacité à éviter les complications cutanées stomiales, parastomiales ou péristomiales5. Le terme péristomial désigne la peau qui entoure la stomie et le terme parastomial désigne la peau située sur les côtés de la stomie, mais dans les deux cas, il s'agit de la peau couverte par la barrière cutanée de l'appareil de stomie1,3.

La prévalence des complications cutanées stomiales, parastomiales et péristomiales à la suite d'une opération de stomie varie considérablement en raison de la conception des études, de l'hétérogénéité des populations, de la taille des échantillons, des types de stomies étudiées (c'est-à-dire entériques ou urinaires), des types de complications examinées et des différences dans les définitions et les terminologies utilisées pour les décrire4-8. Ainsi, l'ampleur de cette disparité est évidente dans la littérature qui rapporte que les complications stomiales et péristomiales varient entre 6 %9 et 80 %4. De plus, ces complications diffèrent d'un point de vue clinique et dépendent du type de stomie créée et du caractère électif ou urgent de l'intervention chirurgicale, ce dernier étant responsable d'un plus grand nombre de complications10-12.

Il semble qu'il y ait des taux de complication plus élevés chez les patients pour les entérostomies telles que les iléostomies, en particulier les iléostomies à anse, identifiés par Park et al.9 comme pouvant atteindre 75 % contre 6 % chez les patients avec des colostomies terminales. Cependant, Wood et al.13 ont constaté que 34,4 % des patients ayant bénéficié de la création d'un conduit iléal ont connu des complications stomiales et 25 % de cette cohorte ont dû subir une intervention chirurgicale pour traiter une hernie ou une rétractation stomiale. Park et al.9 ont effectué un audit rétrospectif des dossiers médicaux de 1 616 patients sur une période de 19 ans et ont déterminé que les raisons des complications stomiales dans leur cohorte étaient les suivantes : l'âge du patient, la discipline chirurgicale pratiquant l'intervention, c'est-à-dire un chirurgien colorectal versus un chirurgien général, l'intervention chirurgicale pratiquée et l'absence de positionnement préopératoire de la stomie par une infirmière ou un infirmier spécialisé(e) dans les plaies, les stomies et la continence (IET)9. Dans son étude, Kann14 a signalé que l'obésité des patients et les maladies inflammatoires de l'intestin étaient des facteurs prédictifs indépendants de complications associées à la stomie.

L'absence de consensus sur les définitions et la terminologie a longtemps été un obstacle à la communication entre les professionnels de santé, les patients et les soignants formels et informels. En outre, les disparités dans les définitions et la terminologie peuvent conduire à des soins non optimaux et à la perte d'occasions de comparer les résultats des soins. Pour tenter d'étudier cette anomalie, Colwell et Beitz7 ont mené une enquête auprès de 686 IET aux États-Unis afin d'établir la validité du contenu des définitions des complications stomiales et péristomiales publiées et des interventions associées. Bien qu'ils aient trouvé un fort niveau de validité de contenu pour les définitions des complications stomiales et péristomiales, ils ont échoué à faire de même pour les interventions de prise en charge associées. En outre, les répondants ont identifié un nombre considérable de complications stomiales et péristomiales omises, en particulier parmi les populations néonatales et pédiatriques, ce qui indique une plus grande diversité dans les définitions et la terminologie utilisées dans les différents contextes cliniques7.

Walls a mené une enquête en 2017 en Australie pour déterminer l'utilisation et l'accord sur les définitions et la terminologie des affections cutanées péristomiales et des présentations cliniques auprès de 191 infirmières et infirmiers stomathérapeutes (IET) qui sont l’équivalent des WOCN. Elle a également constaté une grande disparité dans les définitions et la terminologie utilisées15. L'étude de Wall, comme celle de Colwell et Beitz, a alerté les IET sur la nécessité d'un consensus national sur les complications stomiales et para/péristomiales; cependant, jusqu'à présent, peu d'efforts ont été faits pour encourager cette initiative7,14. Ceci est particulièrement pertinent si l'on considère la charge importante associée aux affections cutanées stomiales et péristomiales. Taneja et al.16 ont constaté que les patients souffrant de complications cutanées péristomiales présentaient des taux de réadmission plus élevés et une augmentation moyenne du coût des soins de santé de 7 400 dollars US, soit 11 654 dollars australiens, par rapport aux patients sans complications.

L'objectif de cette étude était donc d'établir un consensus australien sur la terminologie utilisée pour définir les complications stomiales, parastomiales et péristomiales.

Méthodes

L'étude a porté sur l'évaluation et la hiérarchisation de la terminologie utilisée par des IET australiens pour décrire les complications stomiales, parastomiales et péristomiales. Une revue de la littérature a été entreprise pour définir ces termes, et un processus Delphi en ligne a été mené parmi des IET et des chirurgiens colorectaux australiens experts afin d'obtenir un consensus sur les définitions et la terminologie utilisées. L'approbation éthique a été accordée par le Comité d'éthique de la recherche humaine de l'Université Curtin (HRE2020-0441) et le Comité d'éthique de la recherche humaine de l'Université Notre Dame en Australie et toutes les directives institutionnelles ont été suivies.

Tout d'abord, l'équipe de recherche a dressé une liste des complications stomiales, parastomiales et péristomiales potentiellement d'intérêt par le biais d'un dialogue de groupe éclairé par les connaissances cliniques et universitaires des chercheurs (Annexe 1). Après avoir dressé la liste des complications, une revue extensive de la littérature a été entreprise pour identifier tous les termes supplémentaires associés aux complications stomiales, para/péristomiales et pour créer une base de données de définitions/descriptions pour chacun de ceux identifiés. Ensuite, des photographies cliniques indicatives ont été recueillies auprès des chercheurs et des services de santé participants, avec le consentement des personnes concernées. Enfin, le groupe de recherche a passé en revue la liste des complications afin de sélectionner celles pour lesquelles il existe une variation suffisante dans la terminologie et/ou la compréhension, que ce soit sur le plan clinique ou dans la littérature.

Pour parvenir à un accord national sur le terme et la définition/description les plus acceptables pour chaque complication, un processus Delphi impliquant des IET experts et des chirurgiens colorectaux a été entrepris à l'aide d'une plateforme en ligne spécifique au projet. Le recrutement s'est fait par le biais d'une invitation ouverte et a été diffusé par l'Association des infirmières et infirmiers stomathérapeutes (AASTN) Inc. et sur les réseaux des chercheurs. Les personnes ayant répondu à l'invitation ont été évaluées en tant qu'experts dans ce domaine en utilisant l'explication de la Théorie de l'expertise de Benner, De novice à expert17, incluant la durée de l’expérience clinique, le poste occupé dans le domaine, les publications/présentations et la reconnaissance par les pairs pour définir l'expertise. Parmi l'ensemble des répondants, 20 participants des États et Territoires australiens ont été sélectionnés et ont reçu par courriel une fiche d'information sur la nature anonyme des réponses des participants au processus de consensus. Tous les répondants invités ont accepté de participer et ont confirmé leur consentement lors de l'accès à la plateforme en ligne du processus Delphi.

Le processus visant à obtenir des définitions consensuelles a consisté en quatre tours - trois tours Delphi et un tour de vote prioritaire. Les tours de consensus Delphi ont été menées à l'aide de la méthode d’adéquation RAND, une méthodologie conçue pour aider un panel à parvenir à un accord18. La validité, la fiabilité et l'application de la méthode ont été rapportées précédemment18-21. La plateforme en ligne a été conçue pour appliquer la méthode RAND/UCLA pour calculer les résultats du vote. Au premier tour, chaque complication a été présentée avec :

- Des photographies de la complication.

- Une gamme de termes couramment utilisés pour décrire cette complication, avec un terme identifié comme étant le plus souvent utilisé dans le contexte australien présenté comme le terme nominal de la complication.

- Une définition/description tirée de la littérature.

Les participants ont été invités à indiquer leur niveau d'accord avec l'utilisation du terme proposé et leur niveau d'accord avec la définition à l'aide d'une échelle de Likert à 9 points. Les participants ont également fourni une justification écrite indiquant le raisonnement qui sous-tendait leur niveau d'accord, ainsi que des suggestions d'amélioration de la définition.

La méthode d'adéquation RAND/UCLA18 utilise une échelle de Likert à 9 points avec des tertiles représentant l'accord, l'incertitude ou le désaccord. L'échelle comprenait des descripteurs (tertile 1 : tout à fait d'accord, d'accord, peu d'accord ; tertile 2 : incertain penchant vers l'accord, incertain, incertain penchant vers le désaccord ; tertile 3 : peu en désaccord, en désaccord et tout à fait en désaccord) pour indiquer la direction et la force de l'opinion du participant. Le résultat du vote a été calculé en transférant les points de l'échelle de Likert à une valeur numérique correspondante, le score médian de l'accord sur l'échelle de Likert étant considéré comme le résultat. la méthode d’adéquation RAND a été utilisée pour déterminer si un consensus avait été atteint18. L'intervalle interpercentile (IIP) de 30 % à 70 % a été calculé, ainsi que l'ajustement IIP pour la symétrie (AIIPS). L'IAIIPS est une fonction linéaire de la distance entre le point central de l'IIP (PCIIP) et le point central de l'échelle de Likert (5,0). Si l’AIIPS était supérieur ou égal à la magnitude de l’IIP, il y avait accord. En revanche, une valeur AIIPS inférieure à la magnitude de l’IIP indiquait l'absence d'accord du panel18. Lorsque le panel est parvenu à un accord, et que les commentaires ont indiqué qu'aucune amélioration ne pouvait être apportée à la définition/description, celle-ci a été acceptée comme description consensuelle.

Si le consensus n'était pas atteint, ou si les commentaires suggéraient que des améliorations pouvaient être apportées à la définition, une synthèse des raisonnements du panel était compilée en regroupant les commentaires en désaccord/accord ou neutres par rapport à la définition. L'équipe de recherche a ensuite ajusté la définition pour intégrer les améliorations suggérées par le panel. Pour le tour de consensus suivant, les participants ont reçu la définition affinée, ainsi que le résultat et la synthèse des commentaires du tour précédent. Un maximum de trois tours de consensus a été considéré comme un nombre de votes suffisant afin de maintenir l'engagement des participants20,21.

Pour certains termes, plusieurs définitions ont fait l'objet d'un consensus. Lorsque les résultats du vote indiquaient une préférence de groupe, cette définition a été retenue. Lorsqu'aucune préférence de groupe claire n'était évidente, un classement final des priorités a été effectué. Lors de ce tour, les participants se sont vus présenter toutes les définitions ayant fait l'objet d'un accord, ainsi qu'une définition/description finale issue du dernier tour de commentaires. Les participants ont classé les définitions/descriptions de la plus à la moins appréciée. La définition préférée a été calculée à l'aide d'une méthode de vote multiple par groupe nominal utilisant des scores de classement pondérés. La méthode, qui s'est appuyée sur un examen des méthodes de vote nominal, a été rapportée précédemment21.

Résultats

Après une invitation à participer diffusée au niveau national, 20 candidats ont été invités et acceptés. Les participants avaient un passé en soins infirmiers pour les plaies, les stomies et la continence ou en chirurgie colorectale, 18 d'entre eux ayant plus de 10 ans d'expérience dans leurs disciplines respectives. La participation aux tours individuels a varié de 13 à 20 membres du panel.

Dix termes ont été présentés au panel, dont sept ont fait l'objet d'un accord lors du premier tour. Un terme (dermatite allergique) a été affiné (dermatite de contact allergique) et a fait l'objet d'un accord lors du deuxième tour. Deux termes (granulome mucocutané et granulome muqueux) ont été considérés par le panel comme étant la même affection dans des localisations anatomiques différentes et ont été combinés en un seul terme (granulome). Deux termes (décapage cutané et cloques de tension) ont été combinés en un seul terme - MARSI (lésion cutanée associée à l’adhésif médical)) - qui a fait l'objet d'un accord lors du deuxième tour. Le glossaire final (figure 1) comprend huit termes pour lesquels les définitions ont fait l’objet d’un accord.

La plupart des résultats des votes ont abouti à un consensus en accord avec la définition présentée. L'accord a varié de 55,56 % à 98,95 % lors du premier tour de consensus (dix termes), de 56,25 % à 81,25 % lors du deuxième tour (sept termes) et de 55,0 % à 80,0 % lors du troisième tour (quatre termes). Pour tous les termes, un consensus en accord avec les définitions/descriptions présentées a été atteint à chaque tour, bien que les commentaires des répondants aient fréquemment indiqué que des améliorations pouvaient être apportées à la définition. Aucune préférence claire pour les définitions/descriptions n'a été mise en évidence pour trois termes (dermatite irritative, granulome, excoriation), ce qui a conduit à leur inclusion dans le tour de classement des préférences.

Figure 1. Glossaire consensuel australien des termes relatifs aux complications stomiales.

Toutes les photos sont utilisées avec autorisation, ©les auteurs

Discussion

La peau, qui se compose de l'épiderme, du derme et de l'hypoderme, est un organe dynamique et réactif aux stimuli externes ou aux blessures. La peau maintient l'homéostase, l'intégrité structurelle et l’esthétique, tandis que le stratum corneum ou couche externe de l'épiderme optimise la fonction de barrière de la peau pour la protéger contre les facteurs de stress environnementaux externes tels que l'exposition à la macération ou à la dessiccation ainsi qu’aux traumatismes chimiques et mécaniques22. En outre, la peau joue un rôle central en tant que barrière immunologique grâce à ses réponses immunitaires innées et adaptatives aux agents pathogènes. Cette réponse est considérablement favorisée par le pH de la peau, qui se situe entre 4,1 et 5,8 et est appelé manteau acide23. Le pH acide de la peau non seulement décourage la colonisation bactérienne et réduit le risque d'infection opportuniste, mais joue un rôle dans la régulation de la fonction de barrière de la peau, la synthèse et l'agrégation des lipides, la différenciation épidermique et la desquamation24. Le dysfonctionnement de la fonction de barrière de la peau altère la protection de la peau contre les traumatismes mécaniques tels que le retrait des agents adhésifs, les traumatismes chimiques dus aux irritants présents dans les effluents corporels et l'invasion des micro-organismes. La perte d'intégrité de la peau qui en résulte est source de douleur, d'altération de la qualité de vie et de remise en cause de la perception de l'esthétique corporelle.

Pour beaucoup, les perceptions esthétiques et les altérations de l'image corporelle sont plus encore remises en question par la création d'une stomie. Une morbidité accrue sous forme de complications stomiales, para/péristomiales est fréquemment associée à la création d'une stomie urinaire ou fécale12,25,26. Le taux de complications para/péristomiales et stomiales varie considérablement et serait de 20 à 80 %4-6,26.

Il est intéressant de noter que le type de complications stomiales diffère selon qu'elles surviennent dans les 30 premiers jours postopératoires (appelées complications précoces) ou après 30 jours (appelées complications tardives)10-12,27-29. Les complications stomiales précoces décrites dans la littérature comprennent l'ischémie/nécrose stomiale, la rétractation, la déhiscence mucocutanée et l'abcès parastomial, qui sont principalement liés à une mauvaise perfusion, à la technique chirurgicale ou à une infection10-12,14. Les complications stomiales tardives sont plus souvent une hernie parastomiale, un prolapsus stomial, une rétraction et une sténose12,28-30.

Cependant, la complication cutanée péristomiale la plus importante, tant dans la période postopératoire précoce que dans la période tardive, est la dermatite de contact irritative due à l'exposition de la peau péristomiale aux effluents corporels3,9,12,31. La dermatite de contact irritative a été identifiée par 91 % (n=919) des infirmières et infirmiers interrogés au niveau international comme la complication cutanée péristomiale la plus fréquente dans leur pratique32. Des termes synonymes tels que irritation cutanée9,32, dermatite chimique irritative11, dermatite irritative10,11, dermatite péristomiale3, lésion cutanées associée à l'humidité (MASD)4 et lésion cutanée associée à l'humidité péristomiale (PSMASD)33,34 sont utilisés par certains auteurs pour définir cette affection. Quelle que soit la terminologie utilisée, l'érosion et l'ulcération cutanées qui résultent du contact répété avec les effluents corporels en raison de l'inefficacité des appareils entraînent des douleurs, une image corporelle négative, une diminution de la qualité de vie liée à la santé et de l'utilité des soins, ainsi qu'une augmentation de leur coût35,36. Les complications cutanées péristomiales représenteraient 40 % des rendez-vous des patients avec un ou une IET35.

Parmi les autres affections cutanées péristomiales jugées problématiques dans la littérature, citons la dermatite allergique de contact, les états pathologiques atypiques tels que les varices et le pyoderma gangrenosum et les traumatismes cutanés mécaniques7,12,30,32,33. Là encore, la littérature révèle une incohérence dans la terminologie, car plusieurs termes synonymes sont utilisés par les professionnels de santé pour décrire les traumatismes cutanés mécaniques, notamment le décapage cutané4, la déchirure cutanée4, les MARSI (lésions cutanées associées à l’adhésif médical)37, les MARSI péristomiales (pMARSI)4,33 et les lésions de tension ou cloques4,33.

C'est l'absence de consensus dans la terminologie/définition des complications stomiales et para/péristomiales que l'on retrouve dans la pratique clinique et dans la littérature qui a conduit les chercheurs à entreprendre cette étude, qui s'est appuyée sur l'étude menée par Walls15 et qui visait à obtenir un consensus dans la terminologie stomiale et para/péristomiale parmi les professionnels de santé australiens. La nécessité d'un tel consensus était encore plus évidente après la recherche documentaire des chercheurs, qui a permis d'identifier huit définitions différentes pour la "dermatite de contact irritative"3,4,26,38-42, trois autres pour "l'irritation chimique"3,41,43 et six autres pour "les lésions cutanées associées à l'humidité/les lésions cutanées associées à l'humidité péristomiale"44-49. En effet, il y avait 17 définitions/descripteurs pour ce qui pourrait être considéré comme des termes synonymes de perte para/péristomiale de l'intégrité de la peau due à l'exposition à l'humidité/effluent.

Une confusion terminologique similaire a été constatée pour les présentations cliniques para/péristomiales liées à des traumatismes mécaniques tels que les lésions cutanées associées à l’adhésif médical (pMARSI) (huit définitions)1,4,15,25,38,39,43,50, les cloques de tension (trois définitions)4,37,38 et les affections cutanées infectieuses telles que la folliculite (sept définitions)3,4,26,37,40,42,51. Les lésions pseudo-verruqueuses, également appelées hyperplasie pseudo-épithéliomateuse et dermatite papillomateuse chronique, faisaient l'objet de huit définitions1,3,11,40-42,52,53. En fait, la recherche documentaire a révélé en moyenne trois à cinq définitions/descripteurs pour chaque terme de complication cutanée para/péristomiale recherché.

A l'inverse, la littérature a révélé un accord plus succinct en ce qui concerne les termes utilisés pour décrire la majorité des complications stomiales potentielles telles que la rétraction, la sténose, le prolapsus ou les états métaplasiques. Une concordance similaire a été trouvée pour les altérations pathologiques para/péristomiales de l'intégrité de la peau telles que pyoderma gangrenosum, implants muqueux, caput medusae/varices, eczéma, psoriasis. Par conséquent, les dix termes finalement inclus dans le processus Delphi sont ceux qui ont été jugés comme ayant un nombre plus élevé de définitions/descripteurs utilisés pour décrire les complications stomiales, para/péristomiales telles qu'utilisées par les IET. Parmi ceux-ci, trois termes - dermatite irritative para/péristomiale, granulome et excoriation - ont nécessité trois tours de vote et un tour de vote par ordre de préférence pour parvenir à un consensus sur les définitions.

La dermatite irritative para/péristomiale a été finalement définie comme "une inflammation, une érosion ou une ulcération due à un contact prolongé avec un effluent stomial". Cependant, les réponses des participants qui ont finalement abouti à ce consensus étaient initialement variées et ont donné lieu à d'importantes discussions lors des tours de scrutin.

Un cheminement similaire vers le consensus a été constaté lors des premiers tours de scrutin pour les granulomes, qui ont été définis comme "une hypergranulation papuleuse et friable sur la jonction mucocutanée/sur la stomie, due à une réponse inflammatoire à une irritation localisée et souvent prolongée".

L'excoriation para/péristomiale était peut-être le terme le plus controversé et le cheminement vers ce consensus a été émaillé de nombreux commentaires, dont les suivants :

Je suis d'accord avec la définition de l'excoriation qui est une perte linéaire et superficielle d'épiderme au niveau du péristomial (peau) suite à un grattage. Cependant, je pensais que l'humidité était aussi impliquée dans la présentation de l'excoriation.

Je pense que la partie la plus importante de cette définition est l'utilisation du mot "linéaire", qui représente une ligne de démarcation.

Je ne vois aucune différence entre l'"érosion" et l'"excoriation" - elles ont les mêmes facteurs de causalité et il n'y a rien dans l'"excoriation" qui implique une morphologie linéaire ou une cause artéfactuelle.

[La définition finale est] facile à comprendre pour l'infirmière (ou l’infirmier) générale qui confond souvent ce terme avec les lésions cutanées liées à l'humidité ou la dermatite associée à l'incontinence (DAI).

J'apprécie l'ajout des termes linéaire/ponctué et grattage/blessure. Les personnes peuvent s'associer à ces descripteurs.

L'excoriation a finalement été définie comme "une perte épidermique ou dermique partielle avec un aspect linéaire ou ponctué qui se produit en raison d'un grattage ou d'une blessure".

Bien que deux termes (décapage cutané et cloques de tension) aient finalement été reconnus comme étant des MARSI et qu'un accord ait été trouvé sur la définition lors du deuxième tour, il y a eu un débat initial sur la confusion ou le manque de connaissance de ce terme, comme en témoignent les réponses suivantes :

Le terme "décapage cutané" en est la cause, et non une évaluation de la peau péristomiale elle-même. La cause de la perte de peau est due au fait que la peau a été déchirée ou décollée. Si cette section a pour but de décrire les MARSI, cela devrait probablement se refléter dans le nom.

Lorsque le terme MARSI a été introduit, je ne savais pas ce qu'il signifiait - je trouve le terme "décapage cutané" beaucoup plus clair, sans avoir besoin d'informations supplémentaires. Le terme "décapage cutané" se distingue également des déchirures cutanées.

Les cloques de tension est la même chose que le décapage cutané parce que ce sont des cloques liées aux forces de tension causées par les surfaces adhésives médicales... Comme il y a une cloque, je pense qu'elle devrait être classée comme une cloque seulement; elle peut être due à la tension, mais elle peut ne pas l'être, par exemple, après le retrait de l'appareil et l'évaluation, il peut y avoir une autre raison identifiée comme cause de la cloque.

Le terme décrit le mécanisme en question et suggère la stratégie de traitement. Techniquement, elle pourrait aussi être classée comme MARSI. Je n'ai jamais entendu cette expression, mais elle reflète bien la façon dont la cloque s'est produite, permettant ainsi une prise en charge/prévention efficace et précoce.

Finalement, le décapage cutané et les cloques de tension ont été considérés comme synonymes de MARSI et cette dernière définition a fait l'objet d'un consensus.

Conclusion

Une revue de la littérature et une discussion avec des IET experts ont identifié un manque de consensus dans les définitions/descripteurs utilisés pour définir les complications cutanées stomiales, para et péristomiales communes en Australie. Un processus Delphi a été entrepris et dix termes ont été présentés aux 20 membres du panel qui ont participé à des tours de scrutin. Le consensus résultant pour les définitions a été atteint pour huit termes. Le granulome mucocutané et le granulome muqueux ont été considérés comme des synonymes, tout comme le décapage cutané, les cloques de tension et les MARSI. Les résultats de cette étude sont actuellement diffusés au niveau national et les chercheurs espèrent que les IET d'autres pays relèveront le défi et reproduiront la méthodologie de l'étude afin de permettre un consensus international plus large sur la terminologie. Un tel consensus offrira des possibilités de communication entre les professionnels de santé et les patients, de formation et d'évaluation comparative des complications stomiales, para et péristomiales au niveau international.

Remerciements

Les auteurs tiennent à remercier : la subvention de recherche accordée par l'Association des infirmières et infirmiers stomathérapeutes (AASTN) de l'Australie qui a permis la réalisation de cette étude; les infirmières et infirmiers stomathérapeutes et les chirurgiens colorectaux qui ont participé au processus Delphi et ont volontairement donné de leur temps et de leur expertise; Paul Haesler, qui a conçu et géré la plateforme de vote par consensus en ligne spécifique au projet.

Conflit d'intérêt

Les auteurs n'ont aucun conflit d'intérêt à déclarer.

Financement

Les auteurs n'ont reçu aucun financement pour cette étude.

Author(s)

Keryln Carville* RN PhD STN(Cred)1,2

Emily Haesler PhD2,3

Tania Norman RN STN BCN4,5

Pat Walls RN STN Cert Wound Mt6

Leanne Monterosso RN PhD5,7,8,9

1Silver Chain Group, Perth, Australia

2Curtin University, Perth, Australia

3La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

4West Australian Ostomy Association, Australia

5St John of God Hospital, Murdoch, Australia

6St Vincent’s Northside Private Hospital, Brisbane QLD

7University of Notre Dame Australia, Fremantle, Australia

8Edith Cowan University, WA

9Murdoch University, WA

* Corresponding author

References

- Carmel J, Colwell J, Goldberg M, editors. Ostomy management. Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurses Society core curriculum. 2nd ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

- Australian Council of Stomal Associations. [cited 2020 April 12]. Available from: https://australianstoma.com.au/

- Lyons CC, Smith AJ. Abdominal stomas and their skin disorders. London: Martin Dunitz 2001.

- LeBlanc K, Whiteley I, McNicol L, Salvadelena G, Gray M. Peristomal medical adhesive-related skin injury. JWOCN 2019;46(2):125–136.

- Pitman J, Rawl SM, Schmidt CM et al. Demographic and clinical factors related to ostomy complications and quality of life in veterans with an ostomy. JWOCN 2008;35(5):493–503.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Eaves D, Oster G. Risk and economic burden of peristomal skin complications following ostomy surgery JWCON 2019;46(2):143–149.

- Colwell J, Beitz J, Survey of wound, ostomy and continence (WOC) nurse clinicians on stomal and peristomal complications: a content validation study. JWOCN 2007;34(1):57–69.

- Beitz J, Colwell J. Management approaches to stomal and peristomal complications: a narrative descriptive study. JWOCN 2016;43(3):263–268.

- Park JJ, Pino AD, Orsay CP, Nelson RL, Pearl RK, Cintron JR, Abcarian H. Stoma complications. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1575–1580.

- Butler D. Early postoperative complications following ostomy surgery. JWOCN 2009;36(5):513–519.

- Ratcliff CR. Early peristomal skin complications reported by WOC nurses. JWOCN 2010;37(5):505–510.

- Krishnamurty DM, Blatnik J, Mutch M. Stoma complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017;30(3):193–200.

- Wood DN, Allen SE, Hussain M, Greenwell TJ, Shah PJ. Stomal complications of ileal conduits are significantly higher when formed in women with intractable urinary incontinence. J Urol 2004;72(6 Pt. 1):2300–2303.

- Kann B. Early stomal complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2008;21(1):23–30.

- Walls P. Seeking a consensus for a glossary of terms for peristomal skin complications. Stomal Therapy Aust 2018;38(4):8–12.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Eaves D, Oster, G. Risk and economic burden of peristomal skin complications following ostomy surgery. JWOCN 2019;46(2):143–149.

- Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs 1982;82(3):402–7.

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method users’ manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2001.

- Coleman S, Nelson EA, Keen J, et al. Developing a pressure ulcer risk factor minimum data set and risk assessment framework. J Adv Nurs 2014;70(10):2339–52.

- Haesler E, Carville K, Haesler P. Priority issues for pressure injury research: an Australian consensus study. Res Nurs Health 2018;41(4):355–68.

- Haesler E, Swanson T, Ousey K, Carville K. Clinical indicators of wound infection and biofilm: reaching international consensus. J Wound Care 2019;28(3):S4-S12.

- Abdo J, Sopko N, Milner S. The applied anatomy of human skin: a model for regeneration. Wound Med 2020;28(100179).

- Proksch E. pH in nature, humans and skin. J Derm 2018;45(9):1044–1052.

- Ali SM, Yosipovitch G. Skin pH: from basic science to basic skin care. Acta Derm Venereol 2013;93:261–267.

- Almutairi D, LeBlanc K, Alavi A. Peristomal skin complications: what dermatologists need to know. Int J Derm 2018;57(3):257–264.

- Shabbir J, Britton D. Stoma complications: a literature review. Colorectal Dis 2010;12(10):958–964.

- Harputlu D, Ozsoy S. A prospective, experimental study to assess the effectiveness of home care nursing on the healing of peristomal skin complications and quality of life. J Ostomy Wound Manag 2018;64(10):18–30.

- Husain SG, Cataldo TE. Late stomal complications. Clin in Colon and Rectal Surg 2008;21(1):31–40.

- Bosio G, Pisani F, Lucibello L, et al. A proposal for classifying peristomal skin disorders: results of a multicenter observational study. Ostomy Wound Manage 2007;53(9):38–43.

- Tsujinaka S, Tan KY, Miyakura Y, et al. Current management of intestinal stomas and their complications. J Anus Rectum Colon 2020;4(1):25–33.

- Doctor K. Peristomal skin complications: causes, effects, and treatments. Chronic Wound Care Manag Res 2017;4:1–6. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=34122

- Richbourg L, Thorpe JM, Rapp CG. Difficulties experienced by the ostomate after hospital discharge. JWOCN 2007;34(1):70–79.

- Taggart E, Spencer K. Maintaining peristomal skin health with ceramide-infused hydrocolloid skin barrier. J WCET 2018;38(1):S8–10.

- Rae W, Pridham S. Peristomal moisture-associated skin damage and the significant role of pH. J WCET 2018;38(1):S4–7.

- Meisner S, Lehur PA, Moran, Martins L, Jemec GBE. Peristomal skin complications are common, expensive, and difficult to manage: a population based cost modelling study. PLoS One 2012;7(5):e37813 https://doi.org/10/1371/journal.pone.0037813

- Nichols T, Inglese G. The burden of peristomal skin complications on an ostomy population as assessed by health utility and the physical component summary of SF-36v2®. Value in Health 2018;21:89–94.

- McNichol L, Lund C, Rosen T, Gray M. Medical adhesives and patient safety: state of the science, consensus statements for the assessment, prevention and treatment of adhesive-related skin injuries. JWOCN 2013;40(4):365–380.

- Zulkowski, K. Understanding moisture-associated skin damage, medical adhesive-related skin injuries, and skin tears. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017;30(8):372–381.

- Bryant R, Nix D. Acute and chronic wounds: current management concepts. 3rd ed. Missouri, US: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Oakley A. Contact dermatitis; 2012. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/contact-dermatitis/

- Blackley P. Practical stoma wound and continence management. 2nd ed. Vermont, VIC: Research Publications Pty Ltd; 1998.

- Rolstad BS, Erwin-Toth PL. Peristomal skin complications: prevention and management. Ostomy Wound Manage 2004;50(9):68–77.

- Loehner D, Casey K, Schoetz DJ. Peristomal dermatology. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2002;15(3):209–214.

- Voegeli D. Moisture-associated skin damage: an overview for community nurses. Br J Community Nurs 2013;18(1):6,8,10–12.

- Colwell JC, Ratliff CR, Goldberg M, et al. MASD part 3: peristomal moisture-associated dermatitis and periwound moisture-associated dermatitis: a consensus. JWOCN 2011;38(5):541–553;quiz 554–545.

- Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM, et al. Moisture-associated skin damage: overview and pathophysiology. JWOCN 2011;38(3):233–241.

- Woo KY, Beeckman D, Chakravarthy D. Management of moisture-associated skin damage: a scoping review. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017;30(11):494–501.

- Young T. Back to basics: understanding moisture-associated skin damage. Wounds UK 2017;13(4):56–65.

- Carmel J, Colwell J, Goldberg M, editors. Core curriculum: ostomy management. Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

- Stelton S, Zulkowski K, Ayello EA. Practice implications for peristomal skin assessment and care from the 2014 World Council of Enterostomal Therapists international ostomy guideline. Adv Skin Wound Care 2015;28(6):275–284;quiz 285–276.

- Beitz J, Colwell J. Stomal and peristomal complications: prioritizing management approaches in adults. JWOCN 2014;41(5):445–454.

- Szymanski KM, St-Cyr D, Alam T, Kassouf W. External stoma and peristomal complications following radical cystectomy and ileal conduit diversion: a systematic review. Ostomy Wound Manage 56(1):28–35.

- Stelton S. Stoma and peristomal skin care: a clinical review. Am J Nsg 2019;119(6):38–45.

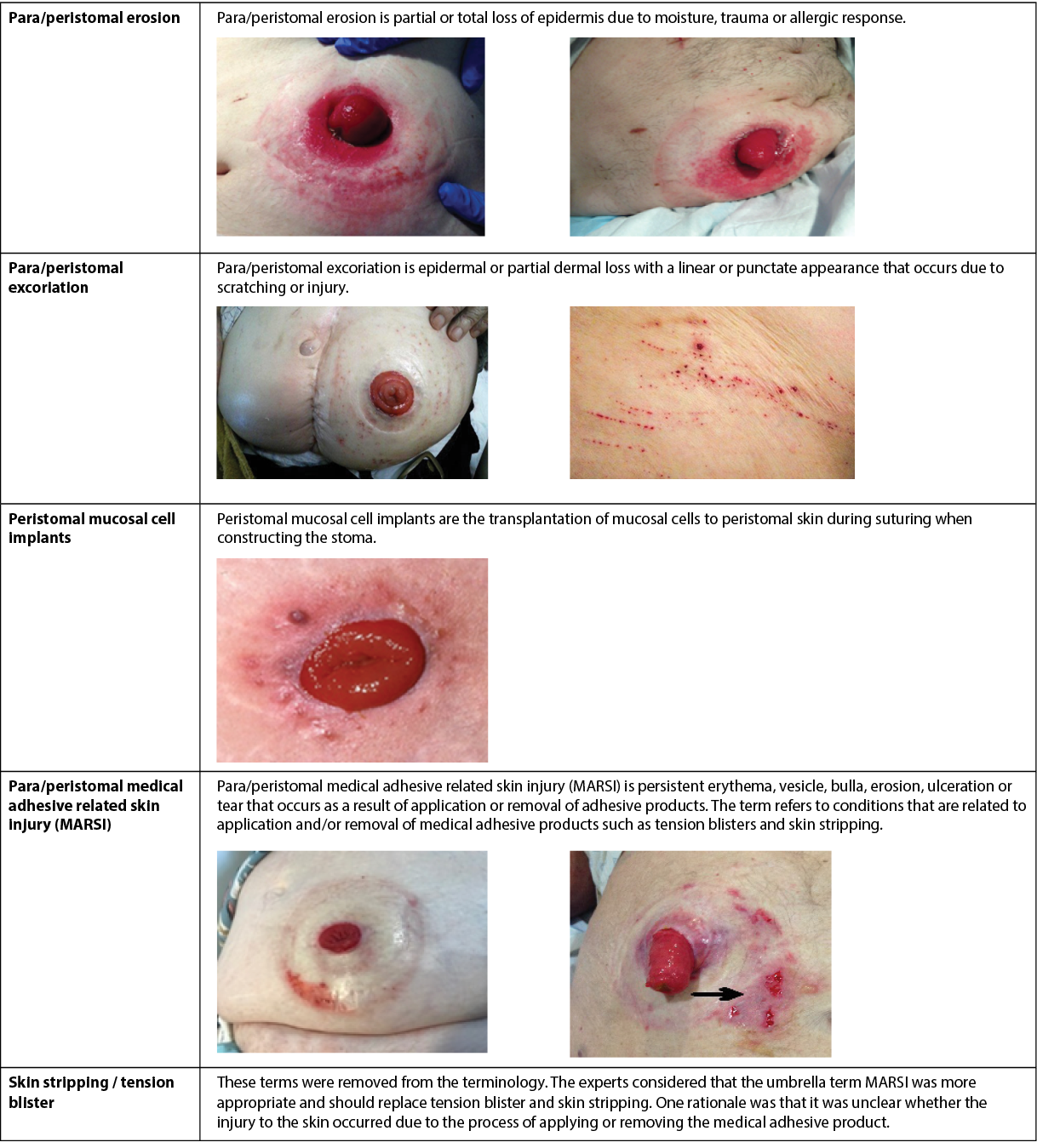

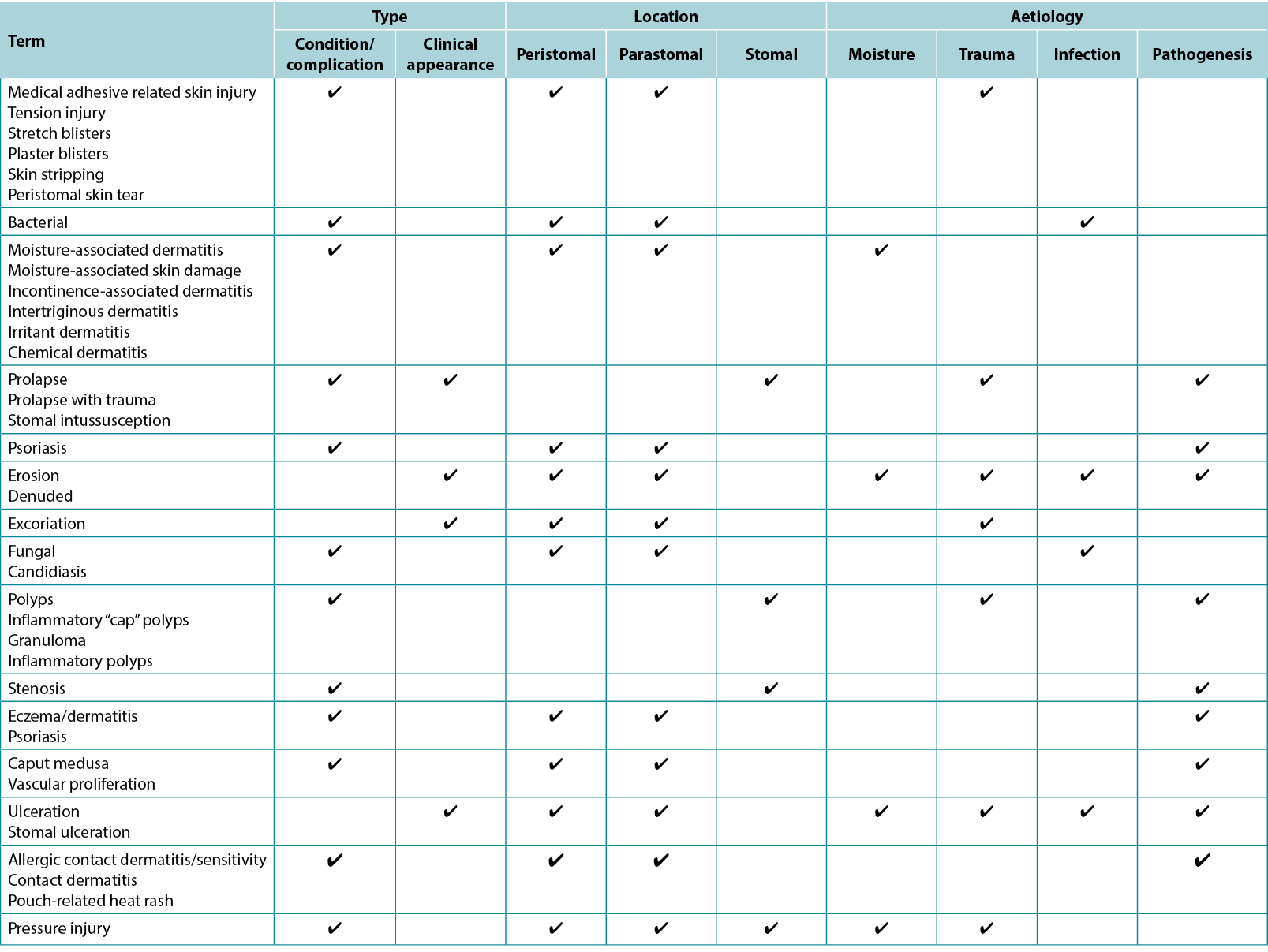

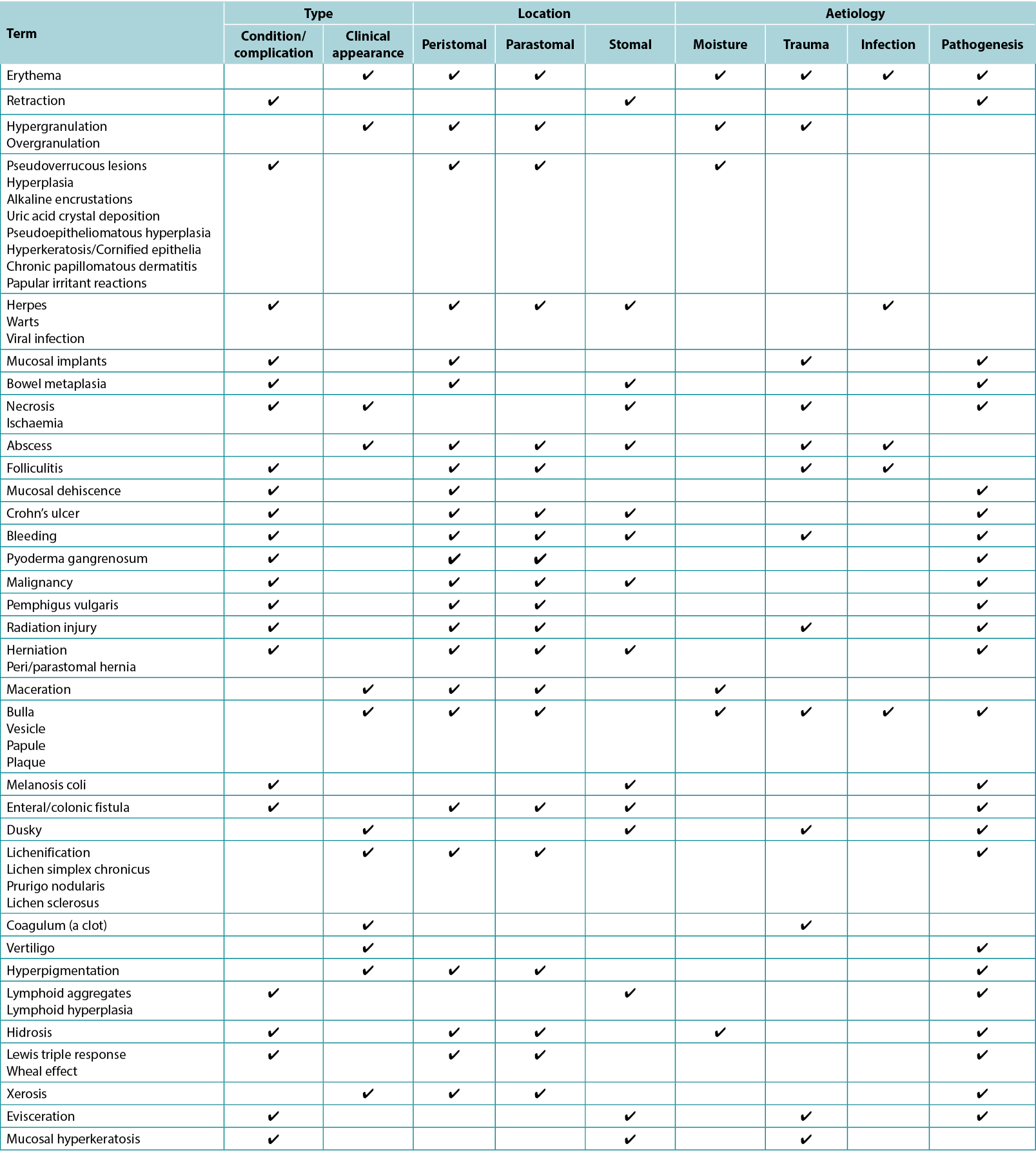

Appendix 1. Terms associated with peristomal, parastomal and stomal complications

Annexe 1. Termes associés aux complications péristomiales, parastomiales et stomiales