Ahead of Print

Burnout and job satisfaction among wound care staff in Saudi Arabia: Implications for quality of care

Abdulaziz Binkanan

Keywords Wound care, job satisfaction, burnout syndrome, Saudi Arabia

For referencing Binkanan A. Burnout and job satisfaction among wound care staff in Saudi Arabia: Implications for quality of care. Wound Practice and Research. 2024;32(2):To be assigned.

DOI

10.33235/wpr.32.2.To be assigned

Submitted 24 November 2023

Accepted 7 April 2024

Abstract

Introduction The demanding nature of wound care, coupled with increased reports of elevated stress among healthcare staff in Saudi Arabia, warranted the examination of burnout and job satisfaction in this healthcare domain.

Aim The study aimed to assess the prevalence of burnout and the level of job satisfaction among wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia.

Methods A cross-sectional online survey was conducted among wound care staff in Saudi Arabia. Participants provided demographic information and responded to standardised questionnaires measuring burnout and job satisfaction.

Results A total of 118 wound care professionals participated in the study. The results revealed alarming levels of burnout among wound care professionals, with many participants experiencing high disengagement (84.7%), exhaustion (83.1%), and burnout (79.7%). Job satisfaction scores were moderately low overall, highlighting the importance of addressing both burnout and job satisfaction in this workforce. Demographic factors such as age, gender, marital status, and working hours per duty showed no significant associations with burnout. However, differences were observed among professional roles, with nurses exhibiting lower burnout levels compared to other professions.

Conclusion The study findings highlight the urgent need for targeted interventions to mitigate burnout and enhance job satisfaction among wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia.

What is already known about the topic

- Existing literature highlights the pervasive issue of burnout among healthcare professionals worldwide, emphasising its prevalence in demanding specialties.

- Studies consistently demonstrate that burnout negatively affects the quality of healthcare delivery, leading to increased medical errors, decreased patient satisfaction, and compromised patient outcomes.

- The healthcare sector, including wound care, faces challenges, such as high workload, long working hours, and emotional strain, all contributing factors to burnout.

Contributions of the current study

- The study contributes by specifically focusing on wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia, providing a deep understanding of burnout and job satisfaction within this unique cultural and healthcare context.

- The study sheds light on the cultural dimension, revealing higher disengagement levels among Saudi participants, and prompting a deeper exploration into cultural factors influencing burnout.

Introduction

Wound care professionals shoulder a significant responsibility, providing specialised care to patients with a variety of wounds, complex medical conditions, and unique healthcare needs. In Saudi Arabia, the high prevalence of diabetes and associated complications add a layer of complexity to the already demanding nature of wound care.1 Recent studies have highlighted a rising prevalence of stress among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia,2–5 indicating a critical need for understanding its impact on professionals in specialised fields, such as wound care.

Job satisfaction of the employees represents a significant factor in the effective functioning of the medical facilities and there is a documented impact of health workers’ satisfaction on multiple aspects of healthcare delivery.6 The satisfaction of health professionals depends on multiple factors including communication with patients, intellectual stimulation, the possibility of continuing medical education, and relationships with colleagues and managers.7 Job satisfaction of the employees represents a significant factor in the effective functioning of the medical facilities and there is a documented impact of physician satisfaction on multiple aspects of healthcare delivery.6 Many studies have shown that job satisfaction measures are a significant predictor of burnout syndrome. 8–10

According to the World Health Organization, burnout is defined as “A syndrome conceptualised as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.”11 Burnout has three sub-dimensions: emotional exhaustion, characterised by lack of energy and enthusiasm, as well as depletion of emotional resources; reduced personal achievement, manifested as a tendency of the worker to negatively evaluate themselves and showing dissatisfaction with their own performance at work; and depersonalisation, defined as negative attitudes toward clients, colleagues, and the service/organisation.12

Burnout has a detrimental influence on both organisations and individuals, resulting in increased staff turnover, absenteeism, sickness, injury and accidents, reduced productivity, as well as interpersonal and organisational issues.13 In addition, one of the symptoms of burnout, depersonalisation among healthcare professionals was associated with self-reported suboptimal patient care practices.14 Burnout is an emerging problem facing health systems, it is a common problem especially in primary care settings.15,16 Burnout and job satisfaction are critical factors that can significantly affect the performance and well-being of healthcare professionals, including wound care staff. The quality of care provided to patients is closely linked to the mental and emotional well-being of healthcare workers. Understanding the levels of burnout and job satisfaction among wound care staff in Saudi Arabia is essential to improving staff well-being and the quality of wound care services.

Methods

Study Design

A descriptive cross-sectional survey was conducted among wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia using convenience sampling. Physicians, nurses and allied health professionals working at wound care department in healthcare facilities in Saudia Arabia were eligible to participate in the survey. The electronic survey was sent to participants staff between 23 September and 2 November 2023. Initial contact was not made with respondents before commencing the study. Study information inviting individuals to contribute to a study that investigated the levels of burnout and job satisfaction in wound care professional in Saudi Arabia was disseminated, including the Participant Information Sheet (PIS) and a link to the survey. The PIS included information regarding the study’s aims, the protection of participants’ personal data, survey length, consent to participate and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Participants were informed that this was a voluntary survey without any monetary incentives.

Data Collection

Data were collected using an online self-administered questionnaire comprised various domains, including sociodemographic and work-related characteristics and validated instruments for burnout and job satisfaction assessment. The questionnaire was uploaded to Google forms and the questions were distributed with randomisation to reduce the possibility of response bias and response validation (completeness check) for all the mandatory items was activated to prevent missed answers in the submitted responses. Respondents were able to review and change their answers using a ‘back button’ function. To ensure questionnaire clarity and relevance, a pilot study involving 30 wound care staff from diverse professions and academic backgrounds was conducted. Feedback was used to help improve the wording of the initial survey questions. In the study only one submission was permitted from each IP address.

Burnout assessment

Burnout syndrome was assessed using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI). The OLBI is a 16-item validated tool for the investigation of burnout. It has eight questions on emotional exhaustion and eight questions on job disengagement. Items consist of both positively and negatively worded questions recorded on a four-point Likert scale from 1 to 4 (Strongly agree – Strongly disagree) with four points for the highest burnout response and one point for the lowest.17 Participants were considered to be at ‘high risk of burnout’ if they met the cut-offs of 2.1 for the exhaustion subscales and 2.25 for disengagement subscales.18,19 OLBI outcomes are defined by four subscale scores that are calculated as the mean of the item scores for each subscale, categorised as follows:20–22

Burnout – High exhaustion score ≥2.25 and high disengagement score ≥2.1

Exhausted – High exhaustion score ≥2.25 and low disengagement score <2.1

Disengaged – High disengagement score ≥2.1 and low exhaustion score <2.25

No burnout – Low exhaustion score <2.25 and low disengagement score <2.1

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured with the validated version of the Warr-Cook-Wall (WCW) job satisfaction scale developed by Warr et al.23 The 16 items WCW instrument measure overall job satisfaction and satisfaction with nine aspects of work (amount of variety in job; opportunity to use abilities; freedom of working method; amount of responsibility; physical working condition; hours of work; income; recognition for work; and colleagues and fellow workers), with each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = extreme dissatisfaction to 7 = extreme satisfaction). A higher overall mean score indicates higher job satisfaction.

Data Analysis

Responses were stored in Google Sheets secured with a password. The data was cleaned and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 26 (https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/26.0.0). Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were utilised to summarise survey responses. The bivariate analysis was performed to examine factors associated with burnout and its domains. The significance of results was judged at the 5% level of alpha error.

Results

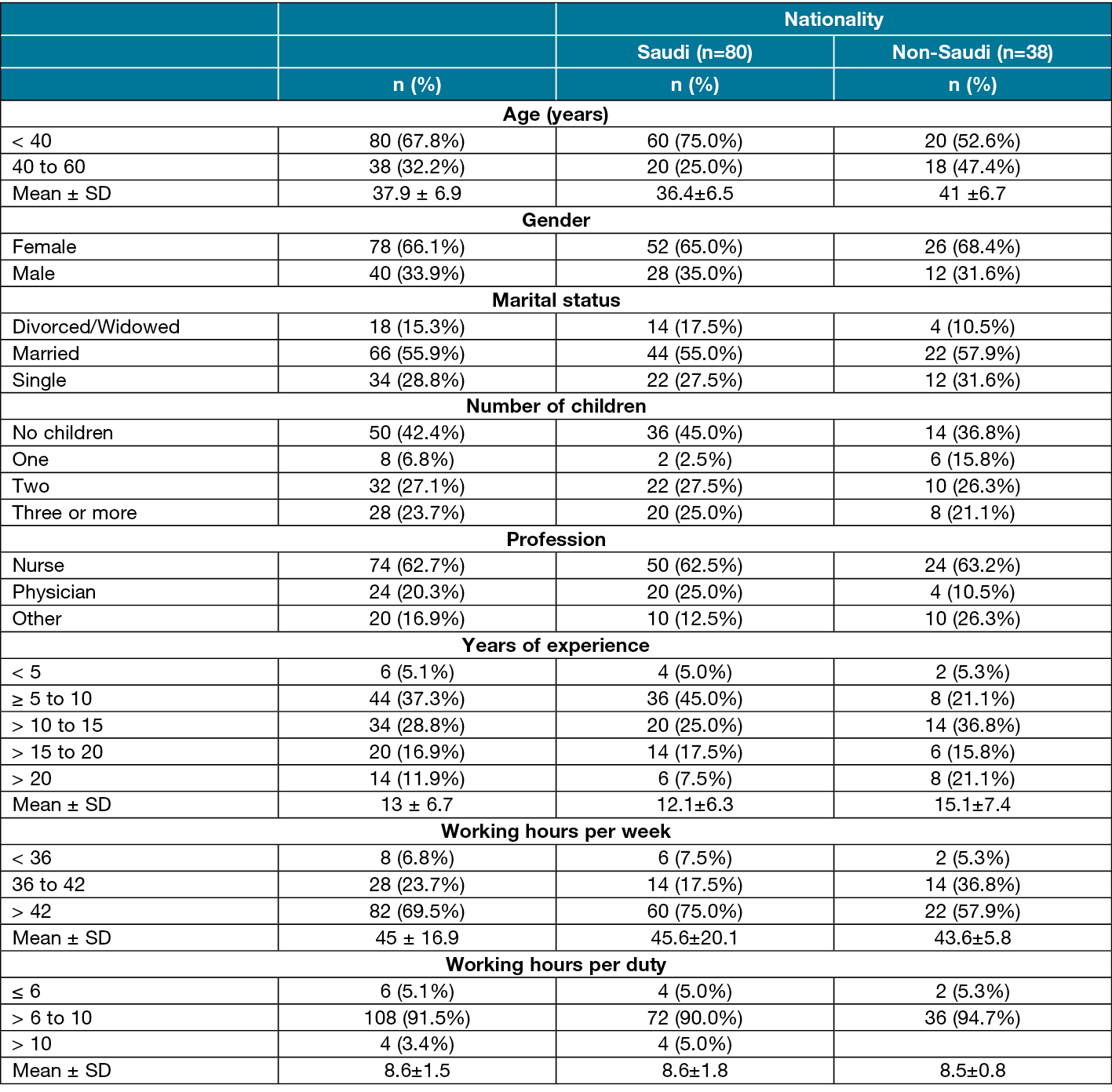

A total of 118 wound care professionals participated in the study. Two thirds of the participants were female; 67.8% were less than 40 years old; 67.8% were Saudis; 66% were married; and 42.4% of the participants had no children. Most (62.7%) of the participants were nurses, and 37.3% of them had five to ten years of experience. Most of participants (69.5%) reported working more than 42 hours per week, and 91.5% were working 6 to 10 hours per duty (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants (n=118)

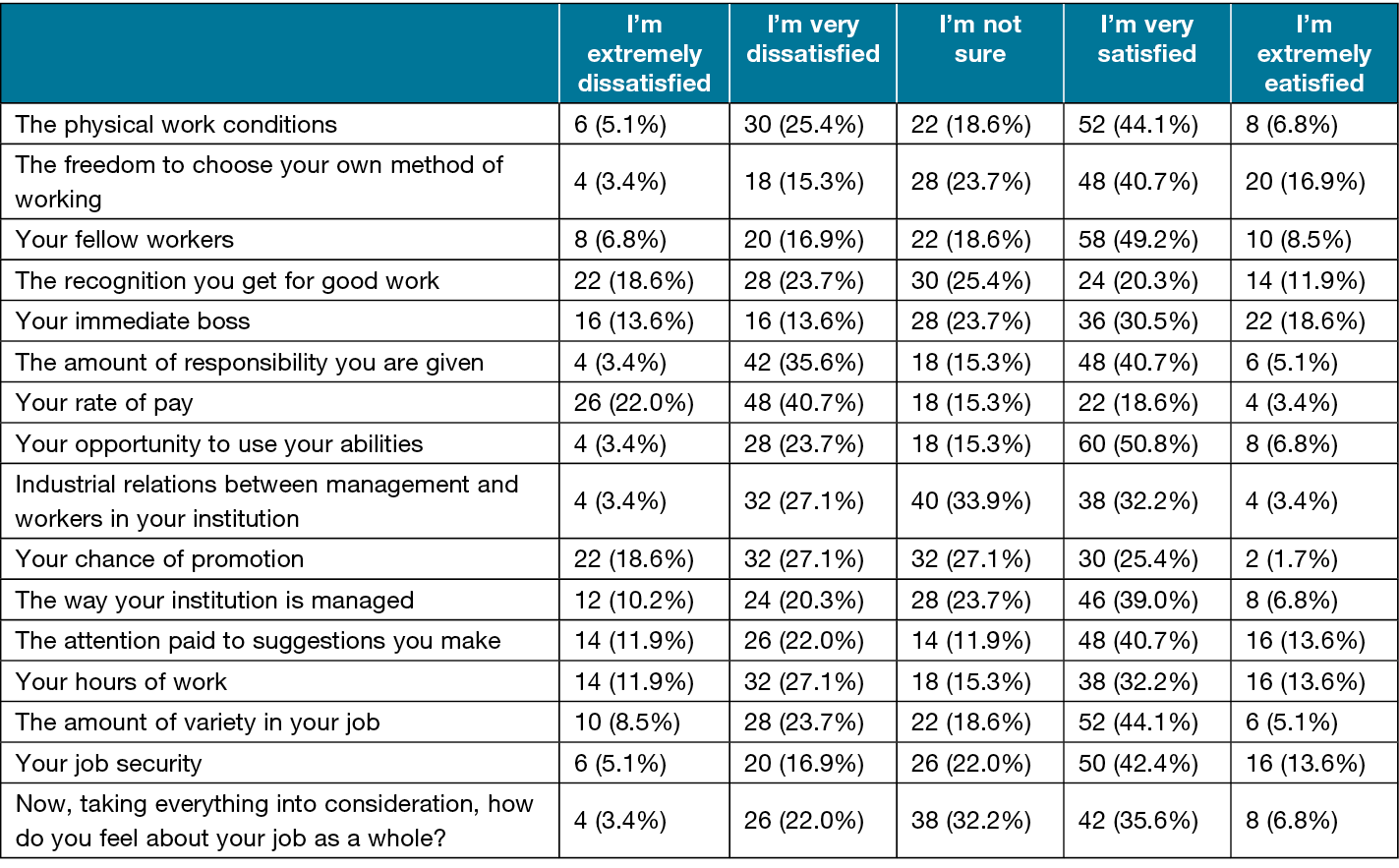

More than half of the participants were satisfied about their physical work conditions, their freedom to choose their own method of working, their fellow workers, their opportunity to use their abilities, the attention paid to their suggestions, and about their job security (Table 2). The total score of job satisfaction among the participants in our study ranged from 31 to 78, with a mean score of 49.9±10.3.

Table 2. Job satisfaction among wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia (n=118)

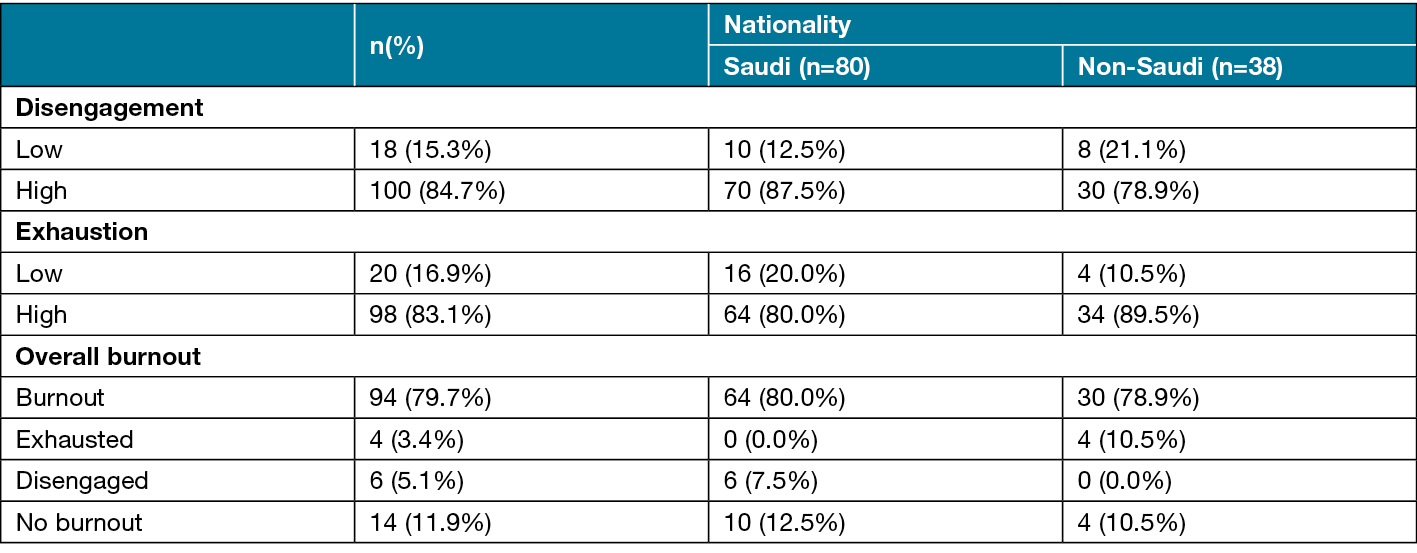

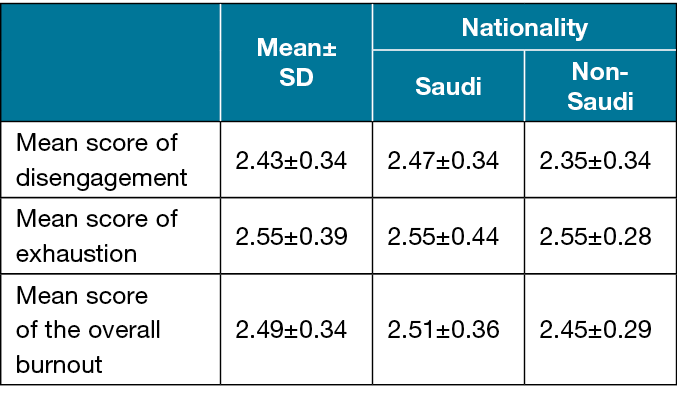

Most of the participants had high levels of disengagement (84.7%), and exhaustion (83.1%). Further, 79.7% suffered burnout syndrome (Table 3). The mean score of disengagement among the participants was 2.43±0.34, and of exhaustion was 2.55±0.39. The mean score of the overall burnout was 2.49±0.34 (Table 4).

Table 3. The distribution of wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia, according to levels of burnout domains

Table 4. Mean scores of burnout syndrome among wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia

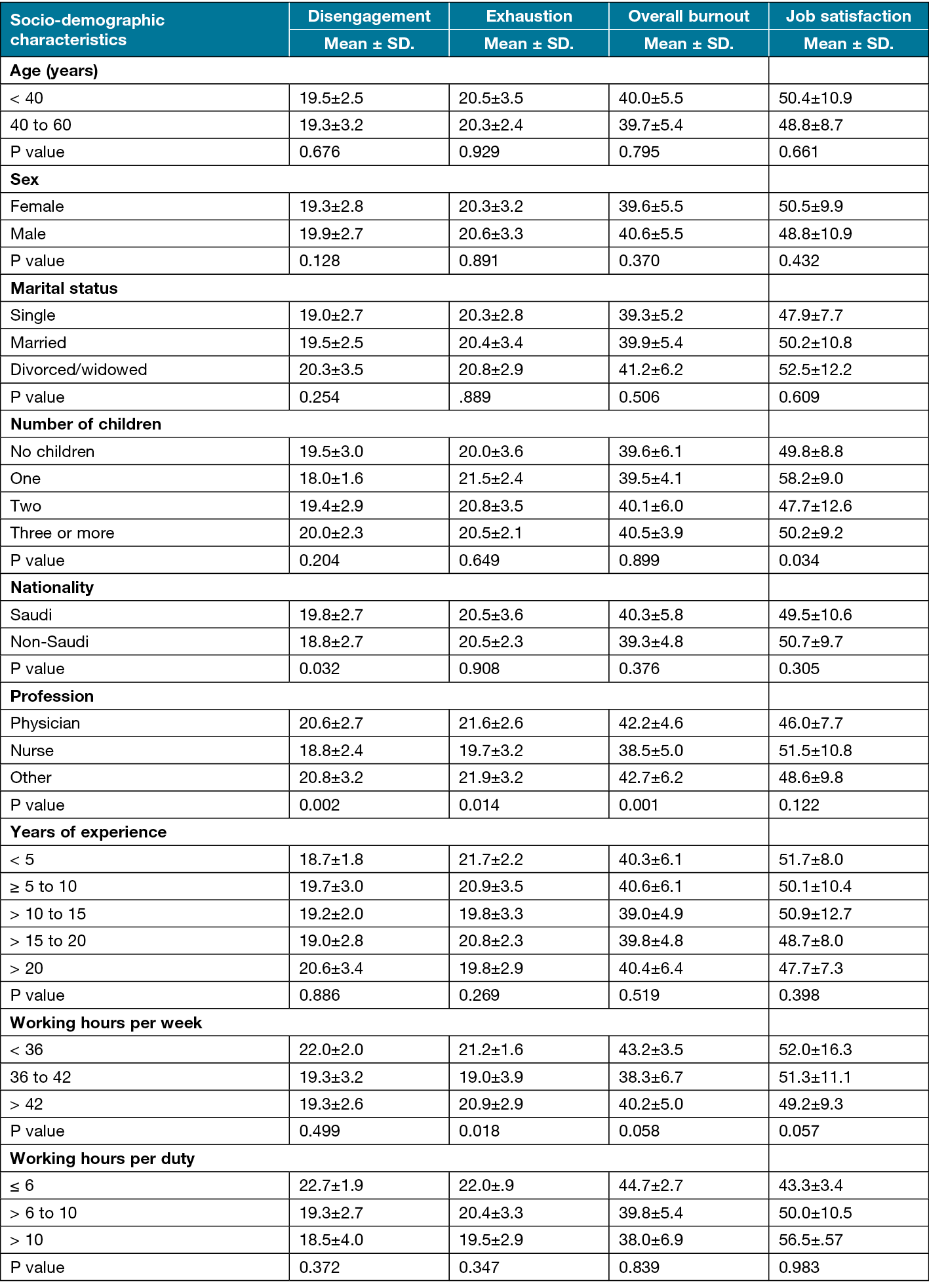

The participants’ age, gender, marital status, number of children, years of experience and working hours per duty had no association with the level of the disengagement, exhaustion, nor the overall burnout (P>0.05). The Saudi participants had significantly higher levels of disengagement compared to non-Saudis (P<0.05), however, exhaustion and the overall burnout showed no association with the participants’ nationality. Nurses had significantly lower levels of disengagement, exhaustion, and overall burnout compared to physicians and other professions (P<0.05). Those who work for 36 to 42 hours per week had lower scores for exhaustion compared to others, and the highest mean score was among those who worked less than 36 hours per week (Table 5). The score of job satisfaction was not significantly affected by the participants’ sociodemographic factors.

Table 5. Relationship between participants’ characteristics and burnout syndrome

Discussion

Studying job satisfaction and burnout among wound care staff is crucial for healthcare delivery as it helps understand the emotional and physical states of this category of workforce, enabling interventions to be tailored to their unique challenges, and nurturing a resilient and satisfied wound care professionals capable of delivering optimal care to patients with complex healthcare needs. To our knowledge this is the first study to investigate the levels of job satisfaction and burnout among wound care professionals.

The first concerning aspect highlighted by our study is the alarming magnitude of burnout among wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia with 79.7% of the participants reported experiencing high levels. This finding suggests that these professionals face elevated levels of work-related stress, aligning with previous studies highlighting heightened stressors and burnout among health professionals in Saudi Arabia.24–26 Beyond the immediate impact on individual well-being, high levels of burnout can have organisational implications, contributing to increased turnover rates within the healthcare profession.27 Addressing burnout among wound care professionals is crucial for both workforce well-being and the quality of care provided. Interventions focused on reducing workload, providing psychological support, promoting work-life balance, and fostering a positive work environment are essential. Implementing stress management programs, providing counseling services, and fostering a culture of mutual support and appreciation can contribute significantly to mitigating burnout in this specialised healthcare domain.

Furthermore, with 84.7% reporting disengagement and 83.1% reporting exhaustion, the study reveals that a substantial portion of the workforce is grappling with the emotional and physical demands of their profession. These findings align with a study conducted in a tertiary teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia, highlighting a similar struggle among healthcare professionals with 61.8% of participants suffering high levels of emotional exhaustion, 58.3% experiencing depersonalisation and 41.0% reporting a sense of decreased professional accomplishment.28 The emotional exhaustion and disengagement reported by our participants – if not addressed − may compromise their ability to deliver patient-centered care, potentially impacting the overall quality and effectiveness of wound care services.

Another interesting observation is the difference in disengagement levels between Saudi and non-Saudi participants. While the reasons behind this discrepancy are not explored in this study, it highlights the need for further research to understand the underlying factors contributing to higher disengagement among Saudi professionals. This information could be invaluable for designing culturally sensitive interventions tailored to the specific needs of Saudi wound care professionals, potentially improving their engagement and overall job satisfaction.

Regarding factors associated with burnout and its dimensions, the significantly lower levels of disengagement, exhaustion, and overall burnout among nurses compared to physicians and other professions are noteworthy. This finding might be attributed to the supportive team environment often found in nursing professions, where teamwork, shared responsibilities, and camaraderie can serve as protective factors against burnout.30–32 There were no significant associations noted between demographic factors such as age, gender, marital status, number of children, years of experience, and working hours per duty with the levels of disengagement, exhaustion, and overall burnout among wound care professionals in the current study. This suggests that burnout in this population is not solely dependent on individual characteristics or work-related variables commonly examined in other studies. The complex nature of burnout indicates that multiple factors, including organisational culture, workload, and job demands, might contribute to the high prevalence of burnout among these professionals.32–35

The job satisfaction scores reported in our study provide valuable insights into the overall contentment levels among wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia. More than half of the participants expressed satisfaction with various aspects of their work environment, such as physical work conditions, freedom to choose their working methods, relationships with colleagues, ability utilisation, attention to their suggestions, and job security. This indicates that there are positive aspects within the workplace that contribute to job satisfaction among wound care staff, as Saudi Arabia commendably strengthened the healthcare system and it prioritises the continuous healthcare workforce development in its 2030 vision.36,37 However, it is essential to note that while some participants reported satisfaction in specific areas, the overall mean job satisfaction score of 49.9±10.3 suggests a moderate level of job satisfaction. This shows that there are areas within the work environment that could be further improved to enhance overall job satisfaction among these professionals.

Limitations

This study encountered several limitations. Adding to the inherent limitations of the research design, the use of convenience sampling technique and online data collection introduces risk of bias potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to all wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia. Also, the use of self-reported questionnaires introduces social desirability bias. Finally the study did not assess stress coping strategies to avoid having a lengthy questionnaire.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the critical issue of burnout among wound care professionals in Saudi Arabia. The findings reveal alarmingly high levels of disengagement, exhaustion, and overall burnout within this workforce. The study uncovered a higher disengagement rate among Saudi professionals, urging further investigation into the cultural and organizational factors contributing to this discrepancy. The findings underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions to address burnout effectively. These interventions are not only crucial for the well-being of wound care professionals but also directly impact the quality of care provided to patients.

Acknowledgements

None

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. It was approved by King Fahd Medical City committee (IRB log Number: 24-303) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The anonymity and confidentiality of the data were ensured, and all participants provided a consent to participate. Participants were informed before the study began that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Participants were aware of study aim and had the right to refuse participation or withdraw at any point.

Funding

None

Authors contribution

AB developed and conceived the study, collected and analysed data and prepared the manuscript for submission.

Author(s)

Abdulaziz Binkanan

Wound Care Department, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding author email binkanan-az@hotmail.com

References

- Alnaim MM, Alrasheed A, Alkhateeb AA, Aljaafari MM, Alismail A. Prevalence of microvascular complications among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who visited diabetes clinics in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2023;44(2):211−217. doi:10.15537/SMJ.2023.44.2.20220719

- Alwaqdani N, Amer HA, Alwaqdani R, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Perceived stress scale measures. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11(4):377−388. doi:10.1007/S44197-021-00014-4

- Alqarni T, Alghamdi A, Alzahrani A, Abumelha K, Alqurashi Z, Alsaleh A. Prevalence of stress, burnout, and job satisfaction among mental healthcare professionals in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0267578. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267578

- AlMuammar SA, Shahadah DM, Shahadah AO. Occupational stress in healthcare workers at a university hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2022;29(3):196. doi:10.4103/JFCM.JFCM_157_22

- Al-Mansour K. Stress and turnover intention among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia during the time of COVID-19: Can social support play a role? PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258101. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258101

- Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Heal Q. 2014;3(4):1−15.

- Verulava T. Job satisfaction and associated factors among physicians. Hosp Top. Published online June 23, 2022:1−9. doi:10.1080/00185868.2022.2087576

- Abd-Ellatif EE, Anwar MM, AlJifri AA, El Dalatony MM. Fear of COVID-19 and its impact on job satisfaction and turnover intention among Egyptian physicians. Saf Health Work. 2021;12(4):490−495. doi:10.1016/j.shaw.2021.07.007

- Zhang Y, Feng X. The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):1−13. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-235/TABLES/6

- Kaplan D. Determinants of job satisfaction and turnover among physicians. Masters Thesis. Published online 2009. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4969&context=etd_theses

- WHO. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. 2019. Accessed April 18, 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99−113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205

- Cordes CL, Dougherty TW. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad Manag Rev. 1993;18(4):621. doi:10.2307/258593

- Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358−367. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008

- Zarei E, Ahmadi F, Sial MS, Hwang J, Thu PA, Usman SM. Prevalence of burnout among primary health care staff and its predictors: a study in Iran. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(12). doi:10.3390/IJERPH16122249

- Seda-Gombau G, Montero-Alía JJ, Moreno-Gabriel E, Torán-Monserrat P. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on burnout in primary care physicians in Catalonia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9031. doi:10.3390/IJERPH18179031

- Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Vardakou I, Kantas A. The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2003;19(1):12−23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.19.1.12

- Bhugra D, Sauerteig SO, Bland D, et al. A descriptive study of mental health and wellbeing of doctors and medical students in the UK. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31(7−8):563−568. doi:10.1080/09540261.2019.1648621

- Westwood S, Morison L, Allt J, Holmes N. Predictors of emotional exhaustion, disengagement and burnout among improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) practitioners. J Ment Heal. 2017;26(2):172−179. doi:10.1080/09638237.2016.1276540

- Peterson U, Demerouti E, Bergström G, Samuelsson M, Åsberg M, Nygren Å. Burnout and physical and mental health among Swedish healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):84−95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04580.x

- Nwosu ADG, Ossai EN, Mba UC, et al. Physician burnout in Nigeria: a multicentre, cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):863. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05710-8

- Card AJ. Burnout and sources of stress among healthcare risk managers and patient safety personnel during the covid-19 pandemic: A pilot study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. Published online 2021. doi:10.1017/dmp.2021.120

- Warr P, Cook J, Wall T. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. J Occup Psychol. 1979;52(2):129−148. doi:10.1111/J.2044-8325.1979.TB00448.X

- Abdoh DS, Shahin MA, Ali AK, Alhejaili SM, Kiram OM, Al-Dubai SAR. Prevalence and associated factors of stress among primary health care nurses in Saudi Arabia, a multi-center study. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2021;10(7):2692. doi:10.4103/JFMPC.JFMPC_222_21

- Alyahya S, Abogazalah F. Work-related stressors among the healthcare professionals in the fever clinic centers for individuals with symptoms of COVID-19. Healthc. 2021;9(5):548. doi:10.3390/HEALTHCARE9050548

- Elbarazi I, Loney T, Yousef S, Elias A. Prevalence of and factors associated with burnout among health care professionals in Arab countries: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2319-8

- Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36. doi:10.1370/AFM.2338

- Alwhaibi M, Alhawassi TM, Balkhi B, et al. Burnout and Depressive Symptoms in Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthc 2022, Vol 10, Page 2447. 2022;10(12):2447. doi:10.3390/HEALTHCARE10122447

- Lu MA, O’Toole J, Shneyderman M, et al. “Where You Feel Like a Family Instead of Co-workers”: a Mixed Methods Study on Care Teams and Burnout. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(2):341. doi:10.1007/S11606-022-07756-2

- Vargas-Benítez MÁ, Izquierdo-Espín FJ, Castro-Martínez N, et al. Burnout syndrome and work engagement in nursing staff: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med. 2023;10. doi:10.3389/FMED.2023.1125133/FULL

- Babiker A, El Husseini M, Al Nemri A, et al. Health care professional development: Working as a team to improve patient care. Sudan J Paediatr. 2014;14(2):9. PMCID: PMC4949805.

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J Organ Behav. 2004;25(3):293−315. doi:10.1002/job.248

- Chou LP, Li CY, Hu SC. Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004185. doi:10.1136/BMJOPEN-2013-004185

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); October 23, 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

- Mijakoski D, Karadzhinska-Bislimovska J, Stoleski S, Minov J, Atanasovska A, Bihorac E. Job demands, burnout, and teamwork in healthcare professionals working in a general hospital that was analysed at two points in time. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(4):723. doi:10.3889/OAMJMS.2018.159

- Rahman R, Al-Borie HM. Strengthening the Saudi Arabian healthcare system: Role of Vision 2030. Int J Healthc Manag. 2021 Oct 2:1-9. doi:10.1080/20479700.2020.1788334

- Alasiri AA, Mohammed V. Healthcare transformation in Saudi Arabia: An overview Since the launch of Vision 2030. Heal Serv Insights. 2022 Sep 3;15. doi:10.1177/11786329221121214