Volume 24 Number 1

Foot-related conditions in hospitalised populations: a literature review

Peter A Lazzarini, Sheree E Hurn, Suzanne S Kuys, Maarten C Kamp and Lloyd Reed

Keywords Foot, conditions, wounds, infections, risk factors.

Abstract

Background: No reviews have investigated foot-related conditions prevalence in hospitalised populations. This literature review reports foot-related conditions (foot wounds, foot infections, amputations, other) and foot risk factors (peripheral arterial disease [PAD], peripheral neuropathy [PN], foot deformity) prevalence in representative or specific hospitalised populations.

Methods: Electronic databases were searched for publications between 1980 and 2011. Keywords and synonyms relating to foot-related conditions, foot risk factors, inpatients and prevalence were used. Studies reporting any foot-related conditions or foot risk factor prevalence in representative or specific hospitalised populations were included, and data were extracted.

Results: Of 3,297 records identified, 141 studies were included; 27 in representative and 114 in specific inpatients. Foot wound prevalence was: 0.9–8.3% in representative and 0.1-96.4% in specific inpatients; foot infection: 0.1–1.1% in representative inpatients; amputation: 0.1–1.5% in representative, 0.2–82.5% in specific inpatients; PAD: 2.1–25.0% in representative, 9.0–72.0 in specific inpatients; and PN: 0.2–100% in specific inpatients.

Conclusions: This review suggests foot wounds are the main foot-related condition in hospitalised populations. Indications are up to 25% of representative inpatients have a foot risk factor for a foot wound, up to 8% have a foot wound and up to 1.5% an amputation. These rates were higher in specific inpatients, particularly inpatients with chronic disease and major trauma.

Background

Foot-related conditions appear to be present in many hospitalised patients and may result in amputation1-5. Leading causes of foot-related condition hospitalisation include foot trauma and foot disease disorders such as foot wounds, foot infections and other severe foot-related conditions such as ischaemia1-6. These foot disease disorders are typically precipitated by common foot risk factors, such as peripheral arterial disease (PAD), peripheral neuropathy (PN), and foot deformity1-4.

Much literature investigating foot-related conditions in hospital has been focused on inpatient groups with specific conditions. Diabetes is frequently acknowledged as the specific condition that is associated with most foot-related hospitalisations1-4,6 and has been reported to account for up to 5% of total hospital bed days used in Australia1,2,7. Other specific chronic diseases have also been shown to cause foot-related hospitalisation, including chronic kidney disease8-10, cardiovascular disease11-13, cancer14,15 and arthritis16,17. Furthermore, other specific conditions, such as trauma4,18,19, infections20,21 and hospital-acquired complications5,22 have been reported to cause foot-related hospitalisation.

Although foot-related conditions and foot risk factors appear to be present in a substantial proportion of hospitalised patients, prevalence estimates across representative and specific inpatient groups has not been ascertained. Without this information it is difficult for clinicians, researchers and policy makers to understand the overall burden of foot-related hospitalisation. This literature review aimed to search, review and tabulate the existing literature reporting prevalence of foot-related conditions (foot wounds, foot infections, other foot-related conditions and amputations) and foot risk factors (PAD, PN and foot deformity) in representative or specific hospitalised populations.

Methods

Data sources

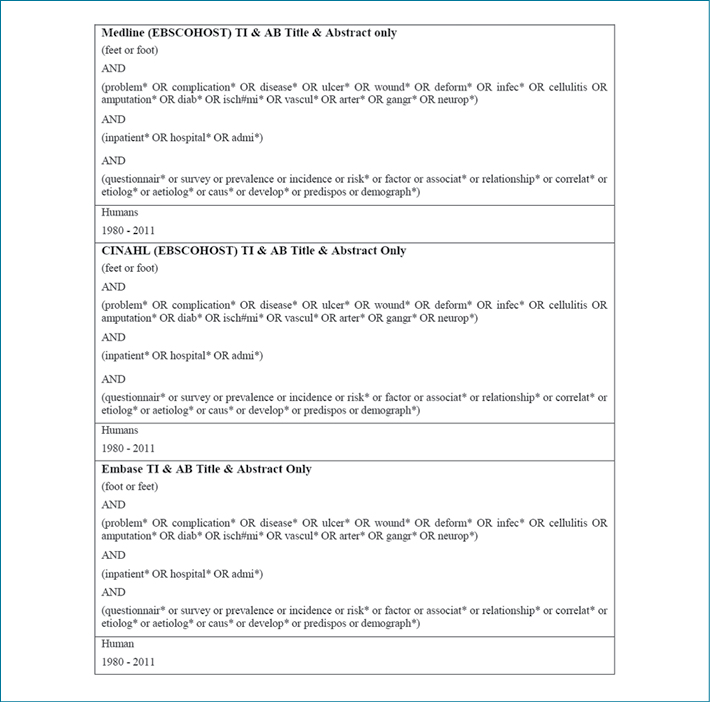

Electronic databases (Medline, Embase, and CINAHL) were searched for all publications between 1980 and 2011 discussing prevalence of foot-related conditions and foot risk factors in hospitalised inpatient populations. Broad keywords and synonyms were used combining: foot-related conditions or foot risk factors, inpatients and prevalence. The search strategy is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Literature review full search syntax used for electronic databases

Study selection

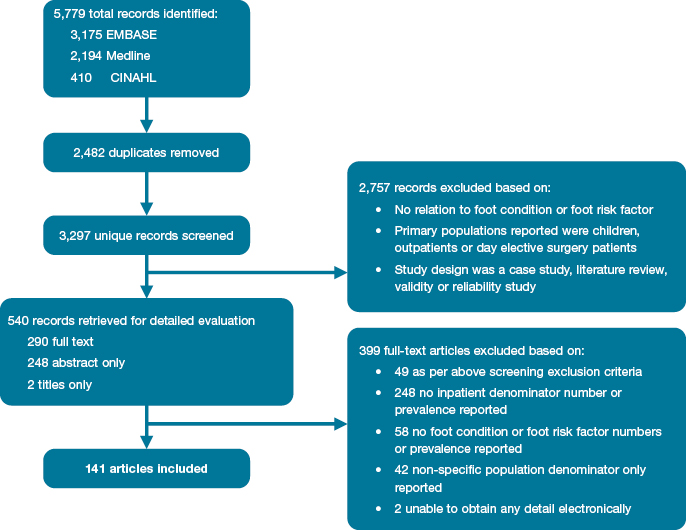

Figure 2 displays the PRISMA flow diagram of the search used. All titles and abstracts retrieved were scanned by the first author (PAL) using an overarching initial screening question: Does the article appear to discuss prevalence of major foot-related conditions or foot risk factors within populations staying overnight in hospital? The full text was sought if the article appeared to address the screening question and was electronically available.

Figure 2: Literature review search results

As this was a narrative literature review, the inclusion eligibility criteria were quite broad. Studies were eligible for inclusion if published in a peer-reviewed journal and referred to the prevalence or number of any foot-related conditions or foot risk factors (the numerator) in a defined inpatient population (the denominator). The numerator of foot-related conditions (foot wound, foot infection, amputation or other foot-related conditions such as ischaemia, Charcot, malignancy or fracture) or foot risk factors (PAD, PN or foot deformity) were defined as listing the foot-related condition or foot risk factor concerned (or a synonym) in the study. The inpatient population denominator could have been either a representative or specific inpatient population. Representative inpatient populations were defined as those that incorporated the diverse range of people hospitalised in the majority of wards of a typical hospital. Specific inpatient populations were a subgroup of inpatients with the same specific medical condition, such as those with diabetes or affected by trauma. Exclusion criteria included case studies, literature reviews, validity or reliability studies; studies investigating populations of primarily children, outpatients or day elective surgery patients; and studies reporting prevalence or incidence in populations other than inpatient populations (for example, amputation procedures per 100,000 general population). The eligibility assessment was undertaken by the first author (PAL) to determine final study inclusion.

Papers that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed and grouped into representative or specific inpatient populations. No formal quality assessment was performed as part of this literature review. Data extracted and tabulated included sample size, age (mean or median), gender, study design and foot-related conditions or foot risk factors prevalence.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported on included studies. If only numbers were reported, these were converted to a prevalence proportion using the ratio of the number of individuals with the foot-related condition or foot risk factor variables (numerator) and the number of the total sample size of the study (denominator).

Results

Search results

Figure 2 displays the results of the literature review search strategy. Database searches yielded a total of 3,297 unique records, of which 540 relevant records were identified for detailed evaluation. Of these, 290 full texts were sourced electronically for evaluation and the remaining 250 could only be evaluated by title and abstract (conference papers, non-English papers or full text unavailable electronically). After evaluation of the 540 records, 141 satisfied the inclusion criteria and were included in this review.

Study characteristics

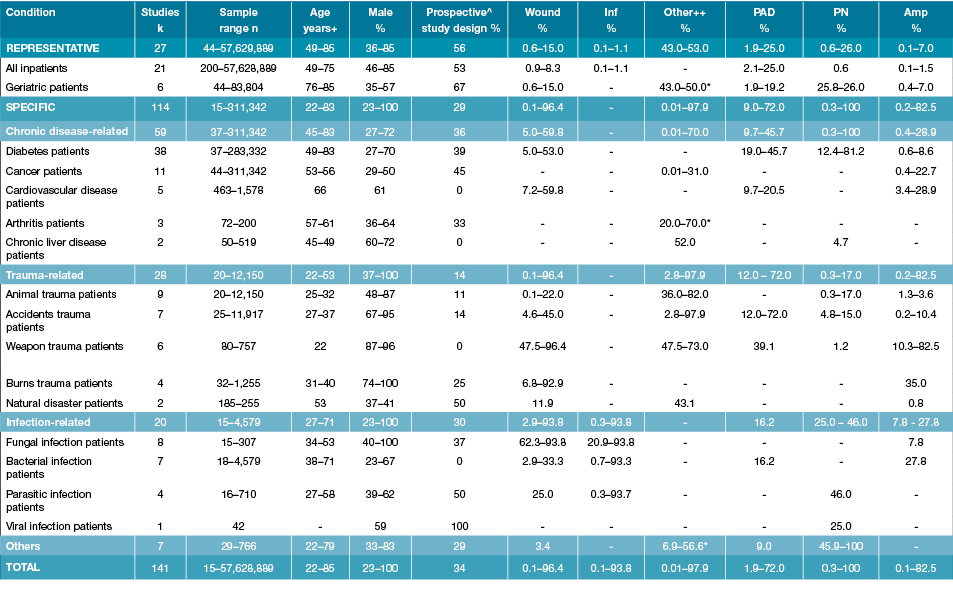

Table 1 summarises the 141 included studies grouped according to study inpatient population (representative or specific), while individual study characteristics are outlined in Tables 2–7. Study characteristics varied considerably in terms of inpatient population, sample size, demographics, study design and the foot-related condition or foot risk factor outcome investigated. Sample sizes varied from 15 to 57 million. There were a large range of average ages (22–79 years) and proportion of males investigated (23–100%). Ninety-three studies (66%) were retrospective, employing medical record audits or hospital discharge database analysis, whilst 48 (34%) were prospective audits using clinical examinations or self-reported questionnaires. One hundred and seven studies were published after the year 2000, 23 in the 1990s and 11 in the 1980s. Lastly, studies were conducted across the world, including 39 in Europe, 31 in Africa, 28 in Asia, 25 in North America, eight in the Middle East, eight in Australasia and two in South America.

Table 1: Summary characteristics of 141 included studies grouped by representative or specific inpatient population

k = Study numbers; n: numbers in study; % prevalence; +Age range from the median or mean age of different studies; ^Prospective study design includes prospective longitudinal and cross-sectional studies; ++Other is either malignancy, combination of injuries or hand-foot-syndrome, unless otherwise specified (refer to Tables 2–7 for further details); *Foot deformity; - Not reported; Amp: Amputations; Inf: Infection; PAD: Peripheral arterial disease; PN: Peripheral neuropathy.

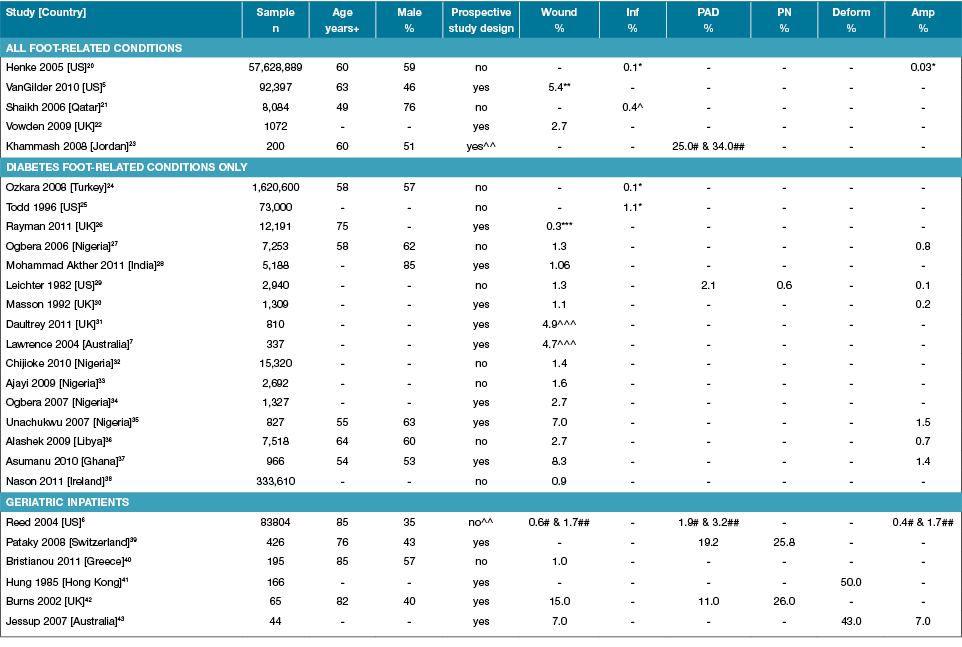

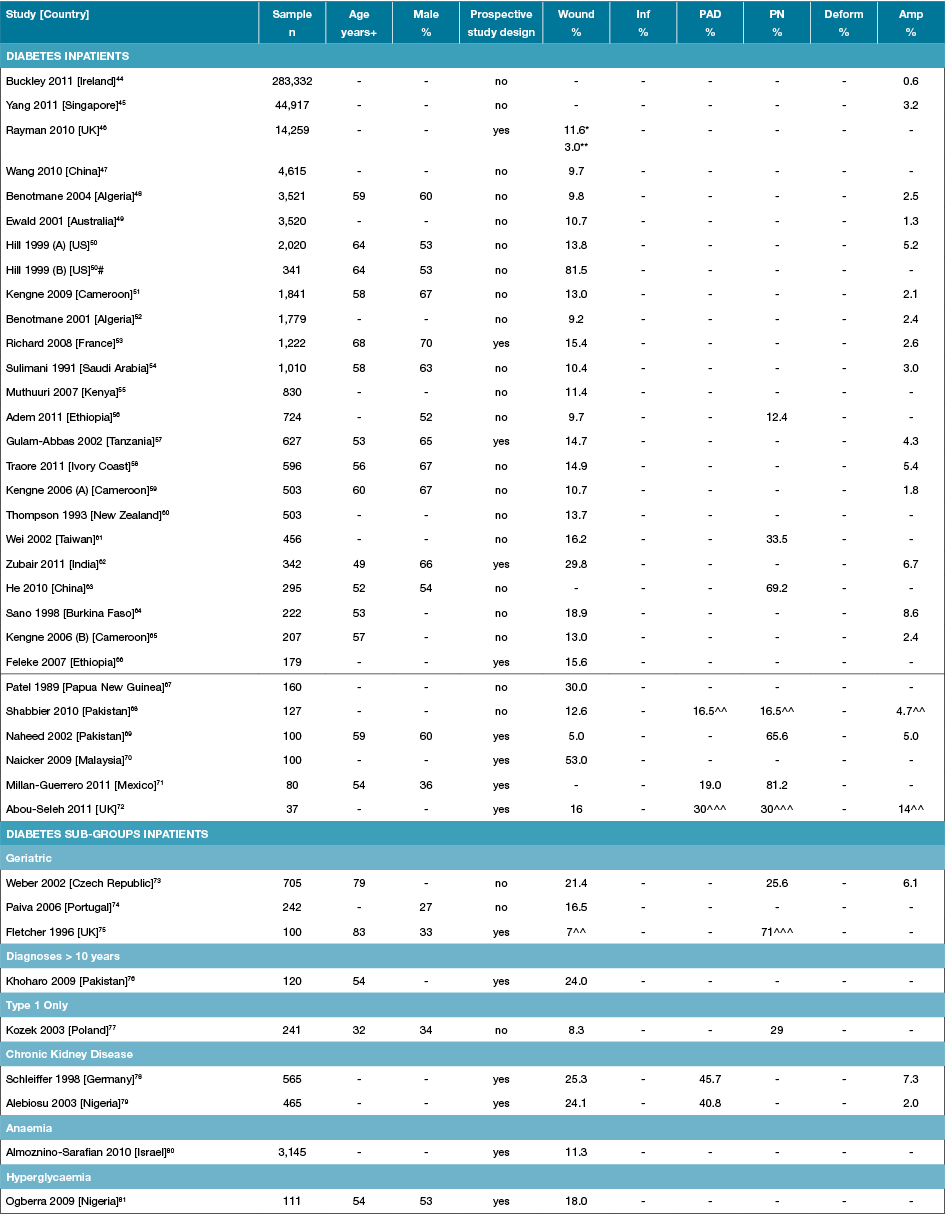

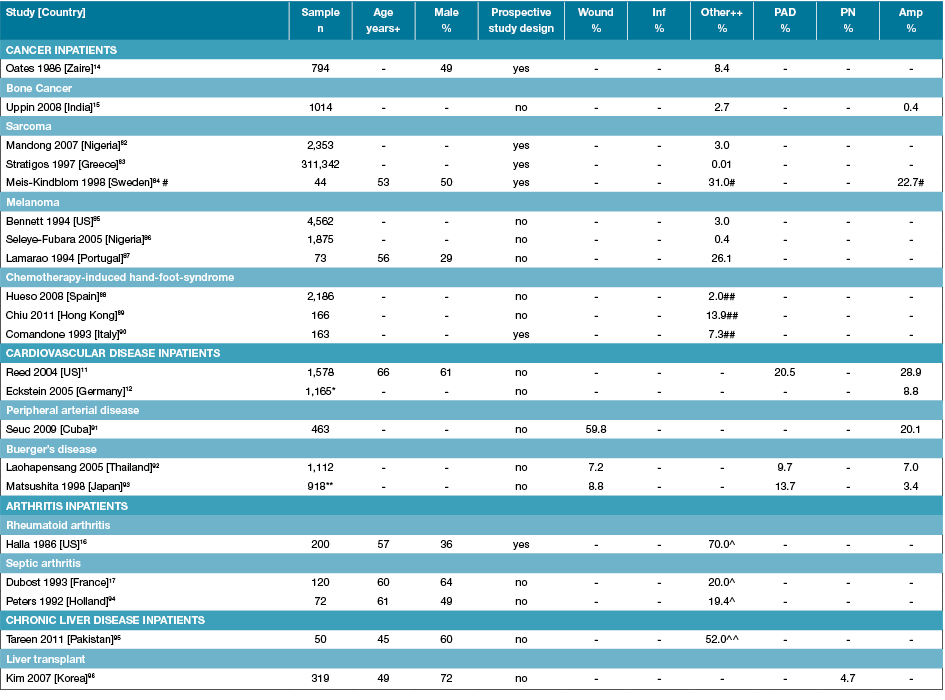

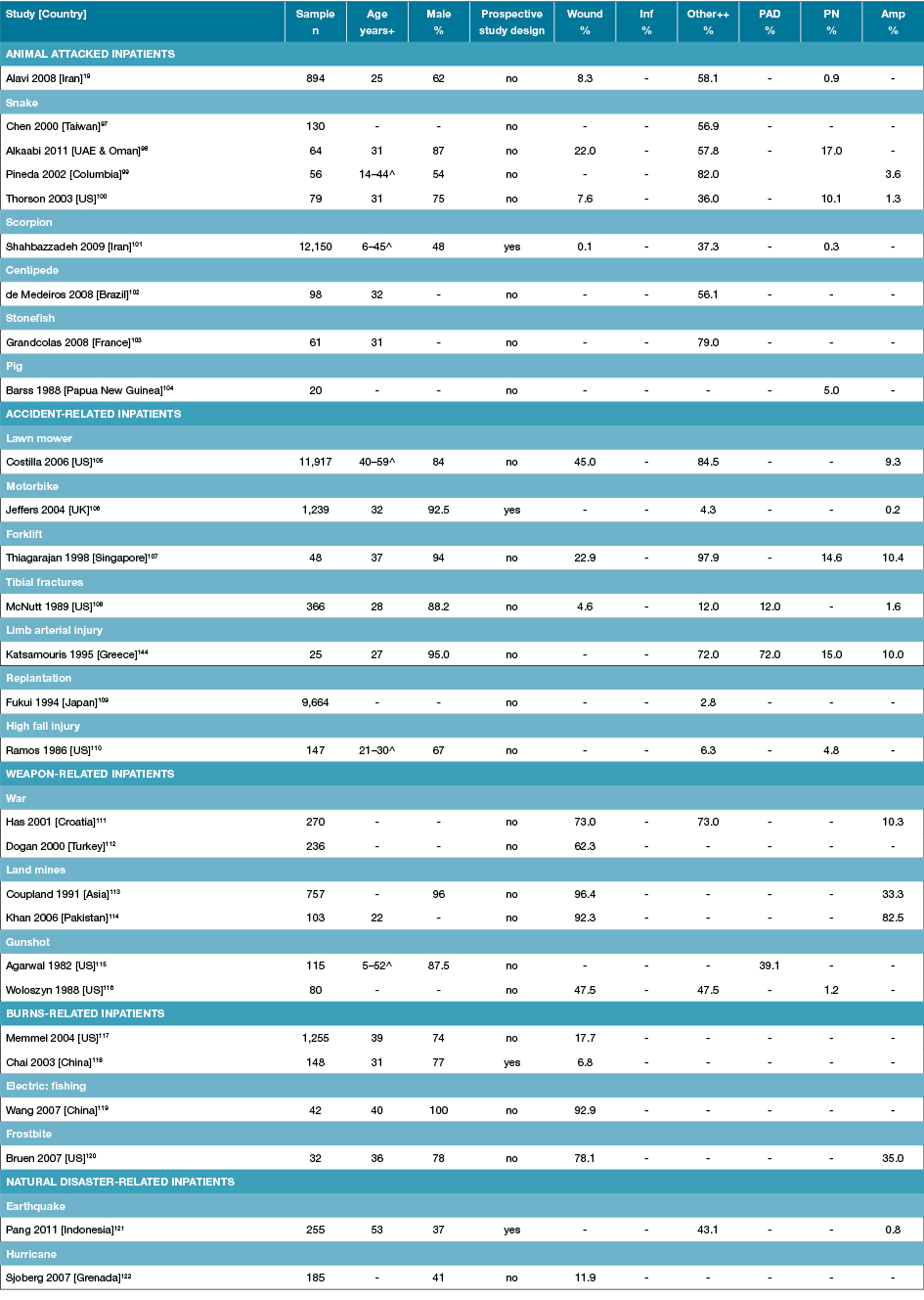

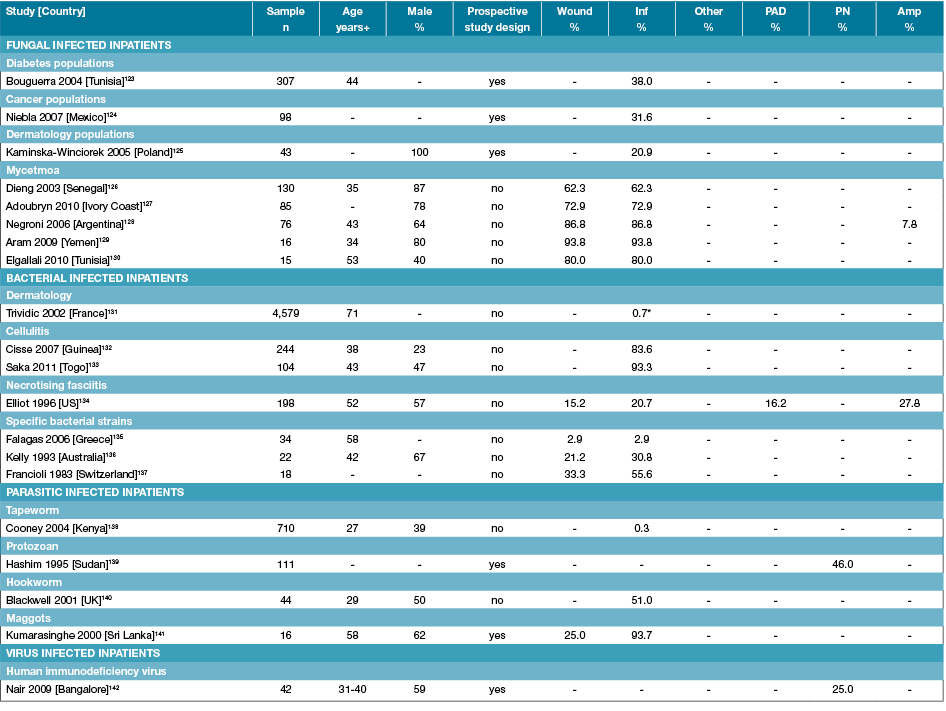

Included studies reported different foot-related conditions and foot risk factors in a wide variety of representative and specific inpatient populations. Twenty-seven studies investigated a representative inpatient population; including five studies investigating foot-related conditions in representative inpatients, 16 investigating only diabetes-related foot conditions in representative inpatients and six investigating foot-related conditions in representative geriatric inpatient populations (Table 2). The other 114 studies investigated a specific inpatient population; including 38 in diabetes (Table 3), 21 other chronic disease (Table 4), 28 trauma-related (Table 5), 29 infection-related (Table 6) and seven in other specific populations (Table 7).

Table 2: Characteristics of studies reporting foot disease and foot risk factors in representative inpatients

Amp: Amputations; Deform: Foot deformity; Inf: Infection; n: Numbers; PAD: Peripheral arterial disease; PN: Peripheral neuropathy; % prevalence; +Median or mean age of sample; - Not reported; *Osteomyelitis only; ** Pressure ulcers only; *** New foot ulcers only; ^ Necrotising fasciitis only; ^^ Case-control study; # non-diabetes inpatients; ## diabetes inpatients; ^^^ Includes history of past ulcers.

Table 3: Characteristics of studies reporting foot disease and foot risk factors in diabetes-specific inpatients

Amp: Amputations; Deform: Foot deformity; Inf: Infection; n: Numbers; PAD: Peripheral arterial disease; PN: Peripheral neuropathy;% prevalence; +Median or mean age of sample; - Not reported; * Includes history of past ulcers; ** New foot ulcers only; ^^ High risk foot (past ulcer or amputation); ^^^ At risk foot risk (PAD or PN); # Foot wounds only.

Table 4: Characteristics of studies reporting foot disease and foot risk factors in other chronic disease-specific inpatients

Amp: Amputations; n: Numbers; PAD: Peripheral arterial disease; PN: Peripheral neuropathy; % prevalence; +Median or mean age of sample; ++ Other is a malignancy or cancer located on the foot unless otherwise specified; - Not reported; *Median of 44 German vascular depts; ** Evaluated from mean yearly figures over 12 years); ^ Foot deformity only; ^^ Palmer erythema only; #Acral sarcoma; ##Hand-foot syndrome located on foot

Table 5: Characteristics of studies reporting foot disease and foot risk factors in trauma-related specific inpatients

Amp: Amputations; Inf: Infection; n: Numbers; PAD: Peripheral arterial disease; PN: Peripheral neuropathy; % prevalence; +Median or mean age of sample; ++ Other is a combination of injuries located on the foot; - Not reported; ^Age range rather than mean age given.

Table 6: Characteristics of studies reporting foot disease and foot risk factors in infection-related specific inpatients

Amp: Amputations; n: Numbers; PAD: Peripheral arterial disease; PN: Peripheral neuropathy; % prevalence; +Median or mean age of sample; - Not reported; * Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

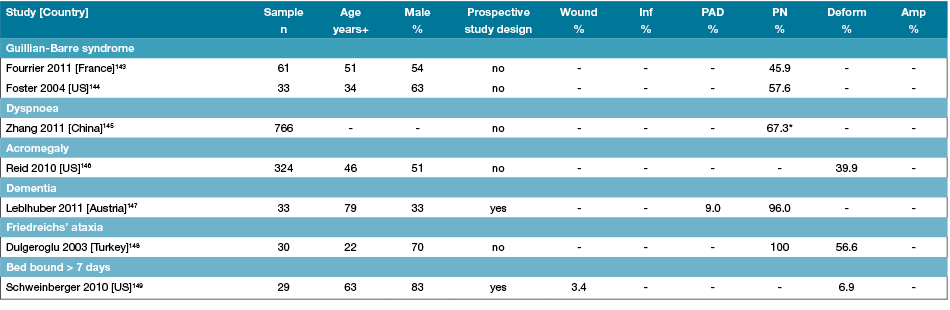

Table 7: Characteristics of studies reporting foot disease and foot risk factors in other specific inpatients

Amp: Amputations; Deform: Foot deformity; n: Numbers; PAD: Peripheral arterial disease; PN: Peripheral neuropathy; % prevalence; +Median or mean age of sample; - Not reported;

*PN symptoms

Prevalence of foot-related conditions and foot risk factors

Table 1 summarises the prevalence ranges from all 141 included studies for foot wounds, foot infections, other foot-related conditions, amputations, PAD, PN and foot deformity in representative and different specific inpatient populations. Data extracted from individual studies is presented in Tables 2–7. Foot wound prevalence ranged from: 0.9–8.3% in representative inpatients, 0.6–15.0% in geriatric, 5.0–53.0% in diabetes, 7.2–59.8% in other chronic diseases, 0.1–96.4 in different trauma-related and 2.9–93.8% in different infection-related specific inpatients. Foot infection prevalence ranged from: 0.1–1.1% in representative inpatients and 0.3–93.8% in different infection-related specific inpatients. Other foot-related condition prevalence ranged from: 0.01–52.0% in other chronic disease and 2.8–97.9% in trauma-related specific inpatients. Amputations occurred in 0.1–1.5% of representative inpatients, 0.4–7.0% geriatric, 0.6–8.6% diabetes, 0.4–28.9% other chronic disease, 0.2–82.5% trauma-related inpatients, 7.8–27.8% in infection-related specific inpatients. PAD prevalence ranged from: 2.1–25.0% in representative inpatients, 1.9–19.2% in geriatric, 19.0–45.7% in diabetes and 12.0–72.0% in trauma-related specific inpatients. PN prevalence ranged from: 25.8–26.0% in geriatric inpatients, 12.4–81.2% in diabetes, 0.3–17.0% in trauma-related, 25.0–46.0 in infection-related and 45.9–100% in other, mainly neurological specific inpatients. Lastly, foot deformity prevalence ranged from: 43.0–50.0% in geriatric inpatients, 20.0–70.0% arthritis and 6.9–56.6% in the other mainly neurological-specific inpatients.

Discussion

This literature review suggests that no study has yet investigated the overall prevalence of foot-related conditions and foot risk factors within a representative inpatient population. Overall, a very broad range of different specific conditions appeared to be associated with foot-related conditions in inpatient populations. Diabetes had by far the largest volume of specific inpatient literature in this foot-related hospitalisation area; yet, multiple studies also investigated other chronic disease, trauma-related, infection-related and other neurological-related specific inpatients for foot–related condition prevalence. All these specific inpatient populations appeared to be associated with a higher prevalence of foot-related conditions or foot risk factors than the average representative inpatient population, indicating these specific conditions may be the leading causes of major foot-related conditions in representative inpatient populations. Foot wounds were the most investigated foot-related condition and were present in approximately 1–8% of representative inpatients, rising to 5–53% in diabetes, 7–60% in other chronic diseases and 0–96% of those inpatients affected by trauma. Foot risk factors were present in up to 25% of representative inpatients and up to 100% of specific inpatient populations. The vast majority of studies identified from this review investigated specific inpatient populations, were retrospective in design and most studies did not appear to investigate the foot-related condition or foot risk factor as the primary outcome of the study. However, as this was a narrative review, it is recommended that a more robust systematic review be performed to systematically identify all literature in the area, the quality of this literature and determine pooled prevalence estimates to more precisely determine the prevalence of foot-related conditions present in inpatient populations.

No study identified in this review investigated a range of foot-related conditions and foot risk factors within a representative inpatient population. Four studies investigated an individual foot-related condition in a representative inpatient population18,20-22. Two studies reported a foot wound prevalence of 2.7%22 and 5.4%5, whilst the other two studies retrospectively investigated large national hospital discharge datasets reporting foot infection represented by an osteomyelitis prevalence of 0.1%20 and a 0.4% necrotising fasciitis prevalence21. Arguably, the closest study to report the prevalence of a range of foot-related conditions and foot risk factors across the broadest cross-section of adult inpatient populations identified by this review was a US study by Reed and colleagues6. This 2004 study retrospectively interrogated a large national discharge dataset in two evenly matched random samples of patients aged 80 years or older to determine foot disease disorder and foot risk factor prevalence for representative geriatric patients discharged with diabetes and without diabetes6. The authors specifically analysed the dataset for codes representing foot ulcers, abscesses, infections, osteomyelitis, PAD and amputation6. A 3.1% prevalence of any foot disease was reported in geriatric inpatients with diabetes and 1.3% for geriatric inpatients without diabetes6. The foot risk factor of PAD was additionally reported in 3.2% of inpatients with diabetes and 1.9% of non-diabetes inpatients6. Individual foot disease disorder prevalence was different for diabetes and non-diabetes inpatients, including foot ulcers (1.7% vs 0.6%), foot infection (0.04% vs 0.02%), osteomyelitis (0.6% vs 0.2%) and amputation (1.7% v 0.4%)6. Overall, the authors concluded that diabetes “in the octogenarian patient imposes an additive risk for [foot] complications”6. However, this study relied entirely on retrospective hospital discharge data. The accuracy of such data capture for specific foot disease disorders and foot risk factors has previously been queried150. This was evident when comparing the very low reporting of PAD in this retrospective study (1.9–3.2%)6 compared to prospective studies reporting PAD in representative inpatients included in this review (11–34%)23,42. Nevertheless, this study is arguably the most complete of the identified studies in this review.

The main foot-related condition reported in inpatient populations was foot wounds. Foot wound prevalence from this review ranged from 0.9–8.3% in representative inpatients37,38 and 0.6–15% in geriatric inpatients6,42. Diabetes-related foot wounds appeared to make up the majority of these reported foot wounds37,38. The higher diabetes-related foot wound prevalence rates (2.7–8.3%) were reported in developing countries34-37, whilst lower rates (1–1.7%) were reported in developed countries29,30,38, with some studies reporting up to 4.9% of representative inpatients had either a current or past diabetes-related foot wound7,31. Interestingly, an interrogation of the studies in developed countries reporting both diabetes and foot wound prevalence in representative inpatients indicates approximately 14–23% of representative inpatients have diabetes7,26,31 and of those foot wounds are present in 11–16%49,50,53,72. These ranges suggest a perhaps more plausible diabetes-related foot wound prevalence of 1.5–3.7% in representative inpatients. In general, diabetes contributed to the largest proportion of foot wound admissions identified from studies in this review6,50. Interestingly, a retrospective US study suggested that diabetes-related foot wounds made up approximately 81% of all foot wound admissions50. Meanwhile, a large pressure ulcer study indicated that pressure ulcers on the foot contributed up to 5% of representative inpatient admissions5. Furthermore, foot wounds were consistently reported to have long lengths of hospitalisation (7–60 days)24,25,27,31,33,35-38, thus potentially inflating this prevalence rate for an analysis of inpatient occupied hospital bed days; although a recent retrospective Irish study reported around 1% of beds were used for diabetes-related foot wound management38.

Most amputations were reported to result in people with a preceding foot wound from the studies included in this review6,27,28,30,35-37,49,50,53. With the exception of a few outliers, amputations appeared to occur in 12–38% of diabetes-related foot wound admissions, or contribute to approximately 0.1–1.5% of representative inpatient admissions in developed countries27,28,30,35-37. Interestingly, amputations in patients admitted with vascular disease also appeared to occur in 10–30% of cases11,12. Most diabetes-related amputations seemed to be the result of severe infection or osteomyelitis of a foot wound6; thus it seems plausible that study results reported in this review had similar amputation6,27,28,30 and osteomyelitis6,20,21,25 prevalence rates as a proportion of total representative inpatient admissions.

The major foot risk factors for foot disease are PAD, peripheral neuropathy and foot deformity2,3,8,9. PAD in this review was present in approximately 11–46% of prospectively examined inpatient populations depending on the underlying specific condition11,23,39,71; the highest prevalence occurred in inpatients with diabetes and kidney disease78,79. Peripheral neuropathy was also highly prevalent in diabetes inpatients (12–81%)39,42,56,60,63,69,73,75,77 and inpatients with other neurological conditions (46–100%), including Guillain-Barre syndrome and Friedreich’s ataxia143,144,148. Interestingly, in one study, PN was reported to be highly prevalent in dementia inpatients; however, this study did state that eliciting a clinical response to neurological testing may have had limitations in this population147. Foot deformity was highly prevalent in geriatric inpatients and those with other neurological conditions. Although foot deformity criteria did differ in most studies, prevalence rates were around 43–50% in geriatric inpatients41,43, 20–70% in arthritic conditions16,17,94 and around 50% of other neurological conditions143,144,148.

Apart from diabetes, other specific conditions that appeared to cause higher prevalence of foot-related conditions and foot risk factors in inpatients identified from this review included cancer14,15,82,85,88, cardiovascular disease11,12,91, arthritis16,17,94, trauma19,101,105,116,117,122, infection126,132,134,142 and different neurological conditions143,144,148. However, studies investigating these specific conditions were extremely heterogeneous, in terms of the populations and foot-related conditions studied, sample sizes, and quality of methodology. Foot-related conditions and foot risk factors seem to be involved in similar proportions of each specific condition’s inpatient population. For example, cancers located on the foot contributed to around 0.4–3.0% of all bone cancers, sarcoma and melanoma admissions15,82,85, excluding studies with small samples and one historical African study conducted over 25 years ago suggesting an 8.4% prevalence14. Furthermore, hand-foot-syndrome, a hospital-acquired complication of chemotherapy in cancer inpatients, was present in 2–13.9% of those particular inpatients88,90. Lastly, the prevalence of foot trauma admissions seemed to contribute to 2.8–6.3% of admissions caused by the overall trauma investigated, such as replantation of severed body parts, motorbike accidents and high fall injuries106,109,110.

Other specific conditions with seemingly high prevalence of foot-related hospitalisations were conditions associated with the ground in developing nations with warm climates or those in war zones; such as animal attacks19,101, land mine injuries113,114, burns117,120, injuries from natural disasters121,122 and fungal infections123,126. Animal attacks resulting in hospitalisation were mainly reported in developing nations, with injuries mostly occurring from snakes, scorpions and dogs19,97-99,101-103, and affecting the feet in 36–82% of cases. Land mine injury admissions affected the feet in up to 96% of admissions and were predominantly reported in nations that had been affected by war111,113,114. Burns to the feet typically from walking on hot surfaces made up 7–17% of burns admissions in studies undertaken in both developing and developed nations117,118. Foot fungal infections occurred in 20–38% of admissions for different conditions and again were reported in developing nations with a warmer climate123-125, with a higher prevalence in medical conditions causing immunosuppression such as cancer and diabetes123,124. Lastly, two studies reported foot-related conditions made up 12–43% of all hospitalisations caused by injuries following natural disasters121,122. The main foot-related injuries following an earthquake were reported to be fractures, lacerations and contusions (Indonesia121), whilst diabetic foot wounds were the main foot-related condition requiring hospitalisation following a hurricane (Grenada122).

Interestingly, no papers meeting criteria in this review specifically focussed on chronic kidney disease-specific inpatient populations. Outpatient populations with chronic kidney disease or end-stage kidney disease have consistently been found to have foot disease disorders and foot risk factors that are similar to those found in diabetes populations8-10. However, kidney disease in this review was often found to be included as a subgroup of diabetes populations78,79. A number of included studies investigated patients with diabetes together with chronic kidney disease and reported foot wound prevalence of 25%, and a PAD prevalence of 45% for this specific inpatient population78,79. These studies also demonstrated diabetes patients on dialysis again had much higher rates of foot wounds (67–75%)78,79, PAD (72–77%)78,79 and amputations (approximately 7%)45,78.

Age and gender also appeared to influence foot-related conditions and foot risk factor rates in inpatient populations. Of the studies investigating representative inpatient populations for foot-related conditions, average age ranged from 49–75 years and there were more males (46–85%) than females in these populations5,20,21,23. Patients admitted with diabetes-related foot disease also tended to demonstrate similar mean age ranges (49–83 years) and higher male proportions (52–70%)24,35-37,48,50,51,53,54,57-59,62,65,81. Other chronic disease-specific foot-related hospitalisations occurred between the ages of 45 and 65 years, and more evenly affected males and females (males 29–72%)14,16,17,84,90,94. Whereas, foot-related hospitalisation due to trauma affected predominantly younger (mean age 22–53 years) male populations (37–100%)19,43,98,110,114,117. Yet, foot infection admissions appeared to occur across a broad range of mean ages (27–71 years) depending on the type of infection and affect similar proportions of males and females126,132,134,138,140.

Only a limited number of studies reported on current or past foot treatment of inpatients with foot-related conditions. This may have been due to the focus of this review being primarily on prevalence and not on treatment. However, those studies reporting past foot treatment were mainly UK-based studies investigating diabetes complications in inpatients26,30,31,46,75. The only study that discussed past foot treatment prior to hospitalisation was a 1996 UK paper indicating 50% of diabetes-specific inpatients had visited a podiatrist in the preceding 12 months, irrespective of their foot-related condition or foot risk factor present75. However, several large point-prevalence cross-sectional studies conducted in UK diabetes inpatient populations indicate that less than one-third of diabetes-specific inpatients have their feet examined whilst in hospital30,31,46. Furthermore, around one-quarter of hospitals did not have inpatient podiatry services or multidisciplinary foot teams26,46.

Limitations

There were several consistent limitations in the papers identified in this review. First, the vast majority of identified studies were retrospective and investigated specific inpatient populations. Second, the majority of papers were primarily investigating other non-foot outcomes and reported foot-related conditions or foot risk factors as minor additional outcome variables. Third, very few prospective papers reported the instruments used for data collection. The only papers specifically reporting testing data collection instruments referred to piloting the instrument prior to the study but did not report any validity or reliability results. Thus, the reliance on either retrospective datasets or prospective data collection instruments of unknown quality and reliability, poses the significant risk of under-reporting foot-related conditions150.

There are a number of limitations to the methodology used for this review. First, the literature search was very broad, performed by one author only, was unable to obtain all full texts, did not hand-search reference lists of included papers, or contact prominent authors for any papers overlooked in the search; thus, there is a likelihood that papers may have been missed. Second, no formal quality assessment of included papers was performed and only descriptive data was extracted. Lastly, only papers published between 1980 and 2011 were included in this review and further applicable literature may have become available. However, a delay between the final search date and the publication date of large literature reviews in the field of foot disease is not unusual151,152 as they still typically provide the first synthesis of the literature in a particular sub-field of the foot disease literature. This review is also the first to synthesise the literature in this sub-field of foot disease and provides a comprehensive understanding of foot-related hospitalisation; demonstrating that foot wounds are the main foot-related conditions in hospitalised populations.

This literature review indicates a gap in the literature investigating the prevalence of foot-related conditions and foot risk factors in representative inpatient populations. It also recommends further more robust systematic reviews are required to verify this gap and provide pooled prevalence estimates of the foot-related inpatients burden. Additionally, it seems that no comprehensive data collection instrument designed to capture foot-related condition data in representative inpatient populations has been tested for validity and reliability. Thus, there is need to develop and test such instruments in future and ensure the instrument includes the specific conditions identified from this review to be associated with higher prevalence of foot-related conditions. Whilst large point-prevalence studies investigating foot-related conditions and foot risk factors within diabetes-specific inpatient populations are beginning to occur26,30,31,46, studies investigating foot-related conditions and foot risk factors in more representative inpatient populations are still required to fully appreciate the overall foot-related hospitalisation.

Conclusions

This review appears to be the first to synthesise the literature surrounding the prevalence of foot-related conditions and risk factors in hospitalised populations. No individual study has investigated the overall foot-related inpatient burden. Specific conditions reported to increase the likelihood of foot-related hospitalisation were diabetes, other chronic diseases, trauma, infection and some neurological conditions. It appears foot wounds have the largest impact on foot-related hospitalisation; contributing to an estimated 1–8% of representative inpatients. Foot infection and amputation appears to complicate 10–40% of these foot wound admissions, whilst the foot risk factors of PAD and PN were present in up to 25% of all inpatients. Interestingly, foot disease-related hospitalisation appears to disproportionately affect 50- to 80-year-old males, whilst foot trauma-related hospitalisation affects 20- to 50-year-old males. The majority of included papers analysed in this review were retrospective, investigated specific conditions and did not report foot-related conditions or foot risk factors as primary outcomes. To more accurately understand the overall foot-related inpatient burden systematic reviews are required to provide more precise prevalence estimates.

Authorship statement

PAL conceived and designed the study, carried out the literature searches, data extraction, and drafted the manuscript. SHE, SSK, MCK and LFR conceived and designed the study, contributed to discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant funding from Queensland Health (Queensland Government, Australia) and the Wound Management Innovation Cooperative Research Centre (Australia).

Author(s)

Peter A Lazzarini*

BAppSci, PhD Candidate

School of Clinical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Allied Health Research Collaborative, Metro North Hospital & Health Service, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Department of Podiatry, Metro North Hospital & Health Service, Queensland Health, Brisbane,

QLD, Australia

Wound Management Innovation Cooperative Research Centre, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Tel: (07) 3139 6172

Email: Peter.Lazzarini@health.qld.gov.au

Sheree E Hurn

PhD

School of Clinical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Suzanne S Kuys

PhD

Allied Health Research Collaborative, Metro North Hospital & Health Service, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

School of Physiotherapy, Australian Catholic University, Banyo, QLD, Australia

Maarten C Kamp

MBBS, FRACP, MHA

School of Clinical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Lloyd Reed

PhD

School of Clinical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

*Corresponding author

References

- Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Diabetes: Australian Facts. In: AIHW, editor. Canberra: Australian Government; 2008.

- Lazzarini PA, Gurr JM, Rogers JR, Schox A, Bergin SM. Diabetes foot disease: the Cinderella of Australian diabetes management? J Foot Ankle Res 2012;5(1):24–.

- Boulton AJM, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 2005;366(9498):1719–24.

- Moxey PW, Gogalniceanu P, Hinchliffe RJ, Loftus IM, Jones KJ, Thompson MM et al. Lower extremity amputations — a review of global variability in incidence. Diabet Med 2011;28(10):1144–53.

- VanGilder C, MacFarlane GD, Harrison P, Lachenbruch C, Meyer S. The demographics of suspected deep tissue injury in the United States: an analysis of the International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey 2006-2009. Adv Skin Wound care 2010;23(6):254–61.

- Reed JF, III. An audit of lower extremity complications in octogenarian patients with diabetes mellitus. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2004;3(3):161–4.

- Lawrence SM, Wraight PR, Campbell DA, Colman PG. Assessment and management of inpatients with acute diabetes-related foot complications: room for improvement. Intern Med J 2004;34(5):229–33.

- Kaminski M, Frescos N, Tucker S. Prevalence of risk factors for foot ulceration in patients with end-stage renal disease on haemodialysis. Intern Med J 2012;42(6):e120–8.

- Freeman A, May K, Frescos N, Wraight PR. Frequency of risk factors for foot ulceration in individuals with chronic kidney disease. Intern Med J 2008;38(5):314–20.

- Korzets A, Ori Y, Rathaus M, Plotnik N, Baytner S, Gafter U et al. Lower extremity amputations in chronically dialysed patients: a 10 year study. Isr Med Assoc J 2003;5(7):501–5.

- Reed T, Jr., Veith FJ, Gargiulo NJ, 3rd, Timaran CH, Ohki T, Lipsitz EC et al. System to decrease length of stay for vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg 2004;39(2):395–9.

- Eckstein HH, Niedermeier HP, Noppeney T, Umscheid T, Wenk H, Imig H. Certification of vascular centers — A project of the German Society of Vascular Surgery. Gefasschirurgie 2005;10(4):263–70.

- Lynch EA, Hillier SL, Stiller K, Campanella RR, Fisher PH. Sensory retraining of the lower limb after acute stroke: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88(9):1101–7.

- Oates KR. A survey of malignant disease in Zaire. Family Practice 1986;3(2):102–6.

- Uppin SG, Sundaram C, Umamahesh M, Chandrashekar P, Jyotsna Rani Y, Prasad VBN. Lesions of the bones of the hands and feet: A study of 50 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132(5):800–12.

- Halla JT, Fallahi S, Hardin JG. Small joint involvement: A systematic roentgenographic study in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1986;45(4):327–30.

- Dubost JJ, Fis I, Denis P, Lopitaux R, Soubrier M, Ristori JM et al. Polyarticular septic arthritis. Medicine 1993;72(5):296–310.

- Epidemiology of lower extremity amputation in centres in Europe, North America and East Asia. The Global Lower Extremity Amputation Study Group. Br J Surg 2000;87(3):328–37.

- Alavi SM, Alavi L. Epidemiology of animal bites and stings in Khuzestan, Iran, 1997–2006. J Infect Public Health 2008;1(1):51–5.

- Henke PK, Blackburn SA, Wainess RW, Cowan J, Terando A, Proctor M et al. Osteomyelitis of the foot and toe in adults is a surgical disease: conservative management worsens lower extremity salvage. Ann Surg 2005;241(6):885–92.

- Shaikh N. Necrotizing fasciitis: A decade of surgical intensive care experience. Indian J Crit Care Med 2006;10(4):225–9.

- Vowden K, Vowden P, Posnett J. The resource costs of wound care in Bradford and Airedale primary care trust in the UK. J Wound Care 2009;18(3):93–4, 6–8, 100 passim.

- Khammash MR, Obeidat KA, El-Qarqas EA. Screening of hospitalised diabetic patients for lower limb ischaemia: Is it necessary? Singapore Med J 2008;49(2):110–3.

- Ozkara A, Delibasi T, Selcoki Y, Fettah Arikan M. The major clinical outcomes of diabetic foot infections: One center experience. Cent Eur J Med 2008;3(4):464–9.

- Todd WF, Armstrong DG, Liswood PJ. Evaluation and treatment of the infected foot in a community teaching hospital. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1996;86(9):421–6.

- Rayman G, Taylor C, Malik R, Holman N, Young B, Morton A et al. The National Diabetes Inpatient Audit 2010 (NaDIA) reveals concerns about inpatient care in English hospitals. Diabetologia 2011;54:S93–S4.

- Ogbera AO, Fasanmade O, Ohwovoriole AE, Adediran O. An assessment of the disease burden of foot ulcers in patients with diabetes mellitus attending a Teaching Hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2006;5(4):244–9.

- Mohammad Akther J, Ali Khan I, Shahpurkar VV, Khanam N, Quazi Syed Z. Evaluation of the diabetic foot according to Wagner’s classification in a rural teaching hospital. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2011;11(2):74–9.

- Leichter SB, Hernandez C, Fisher A, Collins P, Courtney A. Diabetes in Kentucky. Diabetes Care 1982;5(2):126–34.

- Masson EA, MacFarlane IA, Power E, Wallymahmed M. An audit of the management and outcome of hospital inpatients with diabetes: Resource planning implications for the diabetes care team. Diabet Med 1992;9(8):753–5.

- Daultrey H, Gooday C, Dhatariya KK. Increased length of inpatient stay and poor clinical coding in people with diabetes: A point prevalence study. Diabet Med 2011;28:154.

- Chijioke A, Adamu AN, Makusidi AM. Mortality patterns among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Ilorin, Nigeria. Journal of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes of South Africa 2010;15(2):79–82.

- Ajayi EA, Ajayi AO. Pattern and outcome of diabetic admissions at a federal medical center: A 5-year review. Ann Afr Med 2009;8(4):271–5.

- Ogbera AO, Chinenye S, Onyekwere A, Fasanmade O. Prognostic indices of diabetes mortality. Ethn Dis 2007;17(4):721–5.

- Unachukwu C, Babatunde S, Ihekwaba AE. Diabetes, hand and/or foot ulcers: a cross-sectional hospital-based study in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007;75(2):148–52.

- Alashek WA, Ehtuish EF. Surgical management and length of hospital stay for diabetic foot. Jamahiriya Med J 2009;9(2):105–8.

- Asumanu E, Ametepi R, Koney CT. Audit of diabetic soft tissue infection and foot disease in Accra. West Afr J Med 2010;29(2):81–5.

- Nason G, Iqbal N, Strapp H, Gibney J, Egan B, Feeley TM et al. Investment in diabetic foot services: Reducing the drain on resources? Ir J Med Sci 2011;180:S98.

- Pataky Z, Herrmann FR, Regat D, Vuagnat H. The at-risk foot concerns not only patients with diabetes mellitus. Gerontology 2008;54(6):349–53.

- Bristianou M, Panou C, Chatzidakis I, Tsiligrou V, Theodosopoulos I, Rouskas G et al. Causes of fourth aged patients hospitalization in an internal medicine hospital clinic. Eur J Intern Med 2011;22:S108–S9.

- Hung LK, Ho YF, Leung PC. Survey of foot deformities among 166 geriatric inpatients. Foot Ankle 1985;5(4):156–64.

- Burns SL, Leese GP, McMurdo ME. Older people and ill fitting shoes. Postgrad Med J 2002;78(920):344–6.

- Jessup RL. Foot pathology and inappropriate footwear as risk factors for falls in a subacute aged-care hospital. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2007;97(3):213–7.

- Buckley C, Canavan R, O’Farrell A, Lynch T, De La Harpe D, Johnson H et al. Trends in the incidence of lower extremity amputations in individuals with and without diabetes in a 5 year period in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 2011;180:S485.

- Yang Y, Ostbye T, Tan SB, Abdul Salam ZH, Yang KS, Ong BC. Risk factors for lower extremity amputation among patients with diabetes in Singapore. J Diabetes Complications 2011;25(6):382–6.

- Rayman G, Taylor CG, Malik R, Hilson R. The national inpatient diabetes audit reveals poor levels of inpatient foot care. Diabetologia 2010;53:S406.

- Wang C, Lv L, Wen X, Chen D, Cen S, Huang H et al. A clinical analysis of diabetic patients with hand ulcer in a diabetic foot centre. Diabet Med 2010;27(7):848–51.

- Benotmane A, Faraoun K, Mohammedi F, Amani ME, Benkhelifa T. Treatment of diabetic foot lesions in hospital: Results of 2 successive five-year periods, 1918-1993 and 1994-1998. Diabetes Metab 2004;30(3 I):245–50.

- Ewald D, Patel M, Hall G. Hospital separations indicate increasing need for prevention of diabetic foot complications in central Australia. Aust J Rural Health 2001;9(6):275–9.

- Hill SL, Holtzman GI, Buse R. The effects of peripheral vascular disease with osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Am J Surg 1999;177(4):282–6.

- Kengne AP, Djouogo CF, Dehayem MY, Fezeu L, Sobngwi E, Lekoubou A et al. Admission trends over 8 years for diabetic foot ulceration in a specialized diabetes unit in Cameroon. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2009;8(4):180–6.

- Benotmane A, Mohammedi F, Ayad F, Kadi K, Medjbeur S, Azzouz A. Management of diabetic foot lesions in hospital: costs and benefits. Diabetes Metab 2001;27(6):688–94.

- Richard JL, Sotto A, Jourdan N, Combescure C, Vannereau D, Rodier M et al. Risk factors and healing impact of multidrug-resistant bacteria in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Metab 2008;34(4 Pt 1):363–9.

- Sulimani RA, Famuyiwa OO, Mekki MO. Pattern of diabetic foot lesions in Saudi Arabia: Experience from King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med 1991;11(1):47–50.

- Muthuuri JM. Characteristics of patients with diabetic foot in Mombasa, Kenya. East Afr Med J 2007;84(6):251–8.

- Adem A, Demis T, Feleke Y. Trend of diabetic admissions in Tikur Anbessa and St. Paul’s University Teaching Hospitals from January 2005–December 2009, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 2011;49(3):231–8.

- Gulam-Abbas Z, Lutale JK, Morbach S, Archibald LK. Clinical outcome of diabetes patients hospitalized with foot ulcers, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Diabetic Med 2002;19(7):575–9.

- Traore A, Krah KL, Kacou AD, Mobiot CD, Yao LB, Soumaro K et al. Multidisciplinary management of the diabetic foot in the University Hospital Center of Yopougon, Abidjan. Louvain Medical 2011;130(5):129-33.

- Kengne AP, Choukem SP, Dehayem YM, Simo NL, Fezeu LL, Mbanya JC. Diabetic foot ulcers in Cameroon: can microflora prevalence inform probabilistic antibiotic treatment? J Wound Care 2006;15(8):363–6.

- Thompson C, McWilliams T, Scott D, Simmons D. Importance of diabetic foot admissions at Middlemore Hospital. N Z Med J 1993;106(955):178–80.

- Wei JN, Sung FC, Lin RS, Li CY, Tsuang MS, Wang PJ et al. Comparison in diabetes-related complications for inpatients among university medical centers, regional hospitals and district hospitals. Taiwan Journal of Public Health 2002;21(2):115–22.

- Zubair M, Malik A, Ahmad J. Clinico-microbiological study and antimicrobial drug resistance profile of diabetic foot infections in North India. Foot 2011;21(1):6–14.

- He M, Ma J, Wang D, Chang J, Yu X. The disease burden analysis of 295 inpatients with diabetes mellitus from Tongji hospital in China. Value Health 2010;13(7):A527.

- Sano D, Tieno H, Drabo Y, Sanou A. Management of the diabetic foot, apropos of 42 cases at the Ougadougou University Hospital Center. Dakar Médical 1998;43(1):109–13.

- Kengne AP, Dzudie AI, Fezeu LL, Mbanya JC. Impact of secondary foot complications on the inpatient department of the Diabetes Unit of Yaounde Central Hospital. Int J Lower Extrem Wounds 2006;5(1):64–8.

- Feleke Y, Mengistu Y, Enquselassie F. Diabetic infections: clinical and bacteriological study at Tikur Anbessa Specialized University Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 2007;45(2):171–9.

- Patel MS. Bacterial infections among patients with diabetes in Papua New Guinea. Med J Aust 1989;150(1):25–8.

- Shabbier G, Amin S, Khattak I, Sadeeq ur R. Diabetic foot risk classification in a tertiary care teaching hospital of Peshawar. Journal of Postgraduate Medical Institute 2010;24(1):22–6.

- Naheed T, Akbar N, Akbar N, Shehzad M, Jamil S, Ali T. Skin manifestations amongst diabetic patients admitted in a general medical ward for various other medical problems. Pak J Med Sci 2002;18(4):291–6.

- Naicker AS, Ohnmar H, Choon SK, Yee KLC, Naicker MS, Das S et al. A study of risk factors associated with diabetic foot, knowledge and practice of foot care among diabetic patients. Int Med J 2009;16(3):189–93.

- Millan-Guerrero RO, Vasquez C, Isais-Millan S, Trujillo-Hernandez B, Caballero-Hoyos R. Association between neuropathy and peripheral vascular insufficiency in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. Rev Invest Clin 2011;63(6):621–9.

- Abou-Saleh A, Sylvester F, Bede F, Ismail M. An audit of inpatient diabetic foot care. Diabet Med 2011;28:87.

- Weber P, Polcarova V, Kubesova H, Meluzinova H. Diabetic patients of advanced age: Complications and treatment. Geriatrics Today: Journal of the Canadian Geriatrics Society 2002;5(1):48–51.

- Paiva I, Baptista C, Ribeiro C, Leitao P, Carvalheiro M. Diabetes in the elderly: Our reality. Acta Med Port 2006;19(1):79–84.

- Fletcher AK, Dolben J. A hospital survey of the care of elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Age Ageing 1996;25(5):349–52.

- Khoharo HK, Ansari S, Qureshi F. Frequency of skin manifestations in 120 type 2 diabetics presenting at tertiary care hospital. Journal of the Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences 2009;8(1):12–5.

- Kozek E, Gorska A, Fross K, Marcinowska A, Citkowska A, Sieradzki J. Chronic complications and risk factors in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus — retrospective analysis. Przegl Lek 2003;60(12):773–7.

- Schleiffer T, Holken H, Brass H. Morbidity in 565 type 2 diabetic patients according to stage of nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications 1998;12(2):103–9.

- Alebiosu CO, Odusan O, Jaiyesimi A. Morbidity in relation to stage of diabetic nephropathy in type-2 diabetic patients. J Natl Med Assoc 2003;95(11):1042–7.

- Almoznino-Sarafian D, Shteinshnaider M, Tzur I, Bar-Chaim A, Iskhakov E, Berman S et al. Anemia in diabetic patients at an internal medicine ward: Clinical correlates and prognostic significance. Eur J Intern Med 2010;21(2):91–6.

- Ogbera AO, Awobusuyi J, Unachukwu C, Fasanmade O. Clinical features, predictive factors and outcome of hyperglycaemic emergencies in a developing country. BMC Endocr Disord 2009;9.

- Mandong BM, Kidmas AT, Manasseh AN, Echejoh GO, Tanko MN, Madaki AJ. Epidemiology of soft tissue sarcomas in Jos, North Central Nigeria. Niger J Med 2007;16(3):246–9.

- Stratigos JD, Potouridou I, Katoulis AC, Hatziolou E, Christofidou E, Stratigos A et al. Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Greece: A clinico-epidemiological profile. Int J Dermatol 1997;36(10):735–40.

- Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a low-grade tumor of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22(8):911–24.

- Bennett DR, Wasson D, MacArthur JD, McMillen MA. The effect of misdiagnosis and delay in diagnosis on clinical outcome in melanomas of the foot. Am Coll Surg 1994;179(3):279–84.

- Seleye-Fubara D, Etebu EN. Histological review of melanocarcinoma in Port Harcourt. Niger J Clin Pract 2005;8(2):110–3.

- Lamarao P, Marques Pinto G, Dias M, Anes M, Pacheco A, Cardoso J et al. Cutaneous malignant melanoma. Casuistics of the Department of Dermatology of a Lisbon hospital (1980-1990). Skin Cancer 1994;9(2):83–91.

- Hueso L, Sanmartin O, Nagore E, Botella-Estrada R, Requena C, Llombart B et al. Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema: A clinical and histopathologic study of 44 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2008;99(4):281–90.

- 89. Chiu CC, Huang CL, Weng SF, Sun LM, Chang YL, Tsai FC. A multidisciplinary diabetic foot ulcer treatment programme significantly improved the outcome in patients with infected diabetic foot ulcers. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2011;64(7):867–72.

- Comandone A, Bretti S, La Grotta G, Manzoni S, Bonardi G, Berardo R et al. Palmar-Plantar erythrodysestasia syndrome associated with 5-fluorouracil treatment. Anticancer Research 1993;13(5 C):1781–3.

- Seuc AH, Lopez M, Rodriguez L, Montequin JF. Short-term prediction of major lower-limb amputation based on clinical indicators on admission: A single institutional experience in a developing country. International Angiology 2009;28(1):38–43.

- Laohapensang K, Rerkasem K, Kattipattanapong V. Decrease in the incidence of Buerger’s disease recurrence in northern Thailand. Surg Today 2005;35(12):1060–5.

- Matsushita M, Nishikimi N, Sakurai T, Nimura Y. Decrease in prevalence of Buerger’s disease in Japan. Surgery 1998;124(3):498–502.

- Peters RH, Rasker JJ, Jacobs JW, Prevo RL, Karthaus RP. Bacterial arthritis in a district hospital. Clin Rheumatol 1992;11(3):351–5.

- Tareen TMK, Taseer IUH, Malik UE, Naqvi SA. Presentation of complications of chronic liver disease at a tertiary care hospital. Medical Forum Monthly 2011;22(7):61–3.

- Kim BS, Lee SG, Hwang S, Park KM, Kim KH, Ahn CS et al. Neurologic complications in adult living donor liver transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 2007;21(4):544–7.

- Chen JC, Liaw SJ, Bullard MJ, Chiu TF. Treatment of poisonous snakebites in northern Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2000;99(2):135–9.

- Alkaabi JM, Al Neyadi M, Al Darei F, Al Mazrooei M, Al Yazedi J, Abdulle AM. Terrestrial snakebites in the South East of the Arabian Peninsula: patient characteristics, clinical presentations, and management. PloS One 2011;6(9):e24637.

- Pineda D, Ghotme K, Aldeco ME, Montoya P. Snake bites accidents in Yopal and Leticia, Colombia, 1996-1997. Biomédica 2002;22(1):14–21.

- Thorson A, Lavonas EJ, Rouse AM, Kerns Ii WP. Copperhead envenomations in the Carolinas. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2003;41(1):29–35.

- Shahbazzadeh D, Amirkhani A, Djadid ND, Bigdeli S, Akbari A, Ahari H et al. Epidemiological and clinical survey of scorpionism in Khuzestan province, Iran (2003). Toxicon 2009;53(4):454–9.

- de Medeiros CR, Hess PL, Nicoleti AF, Sueiro LR, Duarte MR, de Almeida-Santos SM et al. Bites by the colubrid snake Philodryas patagoniensis: a clinical and epidemiological study of 297 cases. Toxicon 2010;56(6):1018–24.

- Grandcolas N, Galea J, Ananda R, Rakotoson R, D’Andrea C, Harms JD et al. Stonefish stings: difficult analgesia and notable risk of complications. Presse Medicale 2008;37(3 PART 1):395–400.

- Barss P, Ennis S. Injuries caused by pigs in Papua New Guinea. Med J Aust 1988;149(11–12):649–56.

- Costilla V, Bishai DM. Lawnmower Injuries in the United States: 1996 to 2004. Ann Emerg Med 2006;47(6):567–73.

- Jeffers RF, Boon Tan H, Nicolopoulos C, Kamath R, Giannoudis PV. Prevalence and patterns of foot injuries following motorcycle trauma. J Orthop Trauma 2004;18(2):87–91.

- Thiagarajan P, Neeta S, Das De S. Forklift-related injuries. J Orthop Surg 1998;6(2):11–4.

- McNutt R, Seabrook GR, Schmitt DD, Aprahamian C, Bandyk DF, Towne JB. Blunt tibial artery trauma: Predicting the irretrievable extremity. J Trauma 1989;29(12):1624–7.

- Fukui A, Tamai S. Present status of replantation in Japan. Microsurgery 1994;15(12):842–7.

- Ramos SM, Delany HM. Free falls from heights: A persistent urban problem. J Natl Med Assoc 1986;78(2):111–5.

- Has B, Jovanovic S, Wertheimer B, Kondza G, Grdic P, Leko K. Minimal fixation in the treatment of open hand and foot bone fractures caused by explosive devices: Case series. Croat Med J 2001;42(6):630–3.

- Dogan M, Oguz S, Celen O. Injuries of the extremities caused by high energy gunshots and land-mines. Ulus Travma Derg 2000;6(4):231–3.

- Coupland RM, Korver A. Injuries from antipersonnel mines: the experience of the International Committee of the Red Cross. BMJ 1991;303(6816):1509–12.

- Khan MI, Zafar A, Khan N, Saleem M, Mufti N. Outcome of tissue sparing surgical intervention in mine blast limb injuries. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2006;16(12):773–6.

- Agarwal N, Shah PM, Clauss RH, Reynolds BM, Stahl WM. Experience with 115 civilian venous injuries. J Trauma 1982;22(10):827–32.

- Woloszyn JT, Uitvlugt GM, Castle ME. Management of civilian gunshot fractures of the extremities. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988(226):247–51.

- Memmel H, Kowal-Vern A, Latenser BA. Infections in Diabetic Burn Patients. Diabetes Care 2004;27(1):229–33.

- Chai J, Song H, Sheng Z, Chen B, Yang H, Li L. Repair and reconstruction of massively damaged burn wounds. Burns 2003;29(7):726–32.

- Wang F, Chen X, Wang Y, Chen X, Guo F, Sun Y. Electrical burns in Chinese fishermen using graphite rods under high-voltage cables. J Burn Care Res 2007;28(6):897–904.

- Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, Cochran A, Edelman LS, Saffle JR. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg 2007;142(6):546–51.

- Pang HN, Lim W, Chua WC, Seet B. Management of musculoskeletal injuries after the 2009 western Sumatra earthquake. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2011;19(1):3–7.

- Sjoberg L, Yearwood R. Impact of a category-3 hurricane on the need for surgical hospital care. Prehosp Disaster Med 2007;22(3):194–8.

- Bouguerra R, Essais O, Sebai N, Ben Salem L, Amari H, Kammoun MR et al. Prevalence and clinical aspects of superficial mycosis in hospitalized diabetic patients in Tunisia. Med Mal Infect 2004;34(5):201–5.

- Niebla RML, Sangines EG, Becerril FDLB, Ramirez MA, Santiago JL, Arenas R. Superficial mycosis in oncologic patients. A study in 98 patients. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am 2007;35(2):83–8.

- Kaminska-Winciorek G, Brzezinska-Wcislo L. Tinea pedis in dermatological patients in the own study. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2005;22(3):148–55.

- Dieng MT, Sy MH, Diop BM, Niang SO, Ndiaye B. Mycetoma: 130 Cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2003;130(1 I):16–9.

- Adoubryn KD, Koffi KE, Doukoure B, Troh E, Kouadio-Yapo CG, Ouhon J et al. Mycetoma of West African non residents in Cote d’Ivoire. J Mycol Med 2010;20(1):26–30.

- Negroni R, Lopez Daneri G, Arechavala A, Bianchi MH, Robles AM. Clinical and microbiological study of mycetomas at the Muniz Hospital of Buenos Aires between 1989 and 2004. Rev Argent Microbiol 2006;38(1):13–8.

- Aram FO, Bin Bisher SA, Barabba RO, Bafageer SS. Mycetoma in South Yemen. J Bahrain Med Soc 2009;21(2):259–63.

- Elgallali N, El Euch D, Cheikhrouhou R, Belhadj S, Chelly I, Chaker E et al. Mycetoma in Tunisia: A 15-case series. Med Trop 2010;70(3):269–73.

- Trividic M, Gauthier ML, Sparsa A, Ploy MC, Mounier M, Boulinguez S et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dermatological practice: Origin, risk factors and outcome. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2002;129(1):27–9.

- Cisse M, Keita M, Toure A, Camara A, Machet L, Lorette G. Bacterial dermohypodermitis: A retrospective single-center study of 244 cases in Guinea. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2007;134(10):748–51.

- Saka B, Kombate K, Mouhari-Toure A, Akakpo S, Boukari T, Pitche P et al. [Bacterial dermohypodermitis and necrotizing fascitis: 104-case series from Togo]. Médecine tropicale: revue du Corps de santé colonial 2011;71(2):162–4.

- Elliott DC, Kufera JA, Myers RA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg 1996;224(5):672–83.

- Falagas ME, Rosmarakis ES, Avramopoulos I, Vakalis N. Streptococcus agalactiae infections in non-pregnant adults: single center experience of a growing clinical problem. Med Sci Monit 2006;12(11):CR447–CR51.

- Kelly KA, Koehler JM, Ashdown LR. Spectrum of extraintestinal disease due to Aeromonas species in tropical Queensland, Australia. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1993;16(4):574–9.

- Francioli P, Vaudaux B, Glauser MP. Group B streptococcus septicemia. Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift 1983;113(2):38–41.

- Cooney RM, Flanagan KP, Zehyle E. Review of surgical management of cystic hydatid disease in a resource limited setting: Turkana, Kenya. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16(11):1233–6.

- Hashim FA, Ahmed AE, el Hassan M, el Mubarak MH, Yagi H, Ibrahim EN et al. Neurologic changes in visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1995;52(2):149–54.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: Clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol 2001;145(3):434–7.

- Kumarasinghe SP, Karunaweera ND, Ihalamulla RL. A study of cutaneous myiasis in Sri Lanka. Int J Dermatol 2000;39(9):689–94.

- Nair SN, Mary TR, Prarthana S, Harrison P. Prevalence of pain in patients with HIV/AIDS: a cross-sectional survey in a South Indian state. Indian J Palliat Care 2009;15(1):67–70.

- Fourrier F, Robriquet L, Hurtevent JF, Spagnolo S. A simple functional marker to predict the need for prolonged mechanical ventilation in patients with Guillain-Barre syndrome. Crit Care 2011;15(1).

- Foster EC, Mulroy SJ. Muscle belly tenderness, functional mobility, and length of hospital stay in the acute rehabilitation of individuals with Guillain Barre Syndrome. J Neurol Phys Ther 2004;28(4):154–60.

- Zhang A, Hu Z. Analysis of emergency functional dyspnea in a general hospital. Respirology 2011;16:257.

- Reid TJ, Post KD, Bruce JN, Nabi Kanibir M, Reyes-Vidal CM, Freda PU. Features at diagnosis of 324 patients with acromegaly did not change from 1981 to 2006: Acromegaly remains under-recognized and under-diagnosed. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72(2):203–8.

- Leblhuber F, Schroecksnadel K, Beran-Praher M, Haller H, Steiner K, Fuchs D. Polyneuropathy and dementia in old age: Common inflammatory and vascular parameters. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2011;118(5):721–5.

- Dulgeroglu D, Kurtaran A, Erkin G, Kaya K, Aybay C. General properties of patients with Friedreich’s Ataxia and rehabilitation outcomes: A retrospective study. Turkiye Fiziksel Tip ve Rehabilitasyon Dergisi 2003;49(1):27–31.

- Schweinberger MH, Roukis TS. Effectiveness of instituting a specific bed protocol in reducing complications associated with bed rest. J Foot Ankle Surg 2010;49(4):340–7.

- Wraight PR, Lawrence SM, Campbell DA, Colman PG. Retrospective data for diabetic foot complications: only the tip of the iceberg? Intern Med J 2006;36(3):197–9.

- Elraiyah T, Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Tsapas A, Nabhan M, Frykberg RG et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of debridement methods for chronic diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg 2016;63(2):37S–45S.e2.

- Wang Z, Hasan R, Firwana B, Elraiyah T, Tsapas A, Prokop L et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of tests to predict wound healing in diabetic foot. J Vasc Surg 2016;63(2):29S–36S.e2.