Volume 25 Number 2

Management of complicated sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease

Ian Whiteley and Anil Keshava

Keywords chronic wound, sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease, wound products, wound therapies, psychological assessment.

Abstract

This case study documents the treatment interventions and outcomes of a young man with complex pilonidal sinus (PNS) disease. The healing process fluctuated, with periods of improvement and regression. Various wound care products were introduced with the aim of optimising wound bed preparation and healing. Seven general anaesthetics were required to perform surgical interventions, examine wound progress or to apply topical negative pressure wound therapy. The delayed wound healing caused disappointment and frustration for the patient, his family and the team involved in his care. The challenges were exacerbated as treatment took place during his final year of school, while completing the Higher School Certificate (HSC). No pre-existing medical conditions contributed to the delayed healing. Primary wound closure or flap techniques were not recommended due to infection and proximity to the anus. Complete healing was achieved in 343 days.

Introduction

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus (PNS) disease describes a hair-filled cavity in the subcutaneous fat of the natal/gluteal cleft. PNS disease often presents clinically as an abscess, or may manifest as a chronic discharging sinus. Young males are affected twice as often as females, with the highest incidence in the second and third decades. The incidence of PNS disease in the general population is 26 cases per 100,000 people1. PNS wounds will, in general, heal more rapidly after primary closure than following excision and healing by secondary intention2,3. With primary closure, the benefits of off-midline closure compared with midline closure have been demonstrated2,3 and where surgery is the treatment of choice, off-midline closure should be the standard management3. Faster healing times and lower surgical site infections present when an off-midline closure performed3. There was no difference in the rate of surgical site infections reported when comparing surgical closure over versus healing by secondary intention; however, recurrence rates were lower with open healing3. No consensus currently exists on the optimum treatment for PNS and all therapies have various advantages and disadvantages4. No clear benefit was shown for surgical closure over open healing3 leading to investigation of alternative interventions such as fibrin glue for which evidence remains uncertain4. The mean time to healing for open versus surgical closure 65.7:16.6 days3. The purpose of this case study was to document the treatment and outcomes of a complex open PNS wound where healing by secondary intention was substantially delayed.

Background

The patient was a 17-year-old male who turned 18 during treatment. A chronic PNS was evident when the patient presented for the first surgical intervention. The patient was unable to recall the exact duration of symptoms; however, confirmed symptoms had been present for greater than two months. Initial treatment consisted of incision, wide debridement and drainage, following which the patient was discharged with daily community nursing services attending to packing of the wound with a hydrofibre rope (Aquacel®). In the ensuing days the patient experienced increasing pain, exudate and odour from the wound and was referred for a second opinion with a colorectal surgeon at a second hospital and care was taken over.

Presentation

It was arranged for the patient to be reviewed in the Stomal Therapy Outpatient Clinic by a colorectal surgeon and stomal therapy and wound care nurse (STN) at the second hospital. On examination there was purulent exudate, offensive odour, erythema and induration of the surrounding tissue and pain. There was a deep subcutaneous cavity under the right buttock tracking towards the anus resulting from the inflammatory process and infection. A length of ribbon gauze was found packed deep under the flap, this had been retained within the wound track for at least 7 days and not been detected during subsequent daily re-packing. The retained dressing was the result of irregularity in the staff allocated to review and attend to wound care, with several different nurses visiting the patient during the early treatment period. Following this incident the patient and family wanted consistency of care and decided to attend the outpatient wound clinic for ongoing assessment and management.

Discussion/interventions

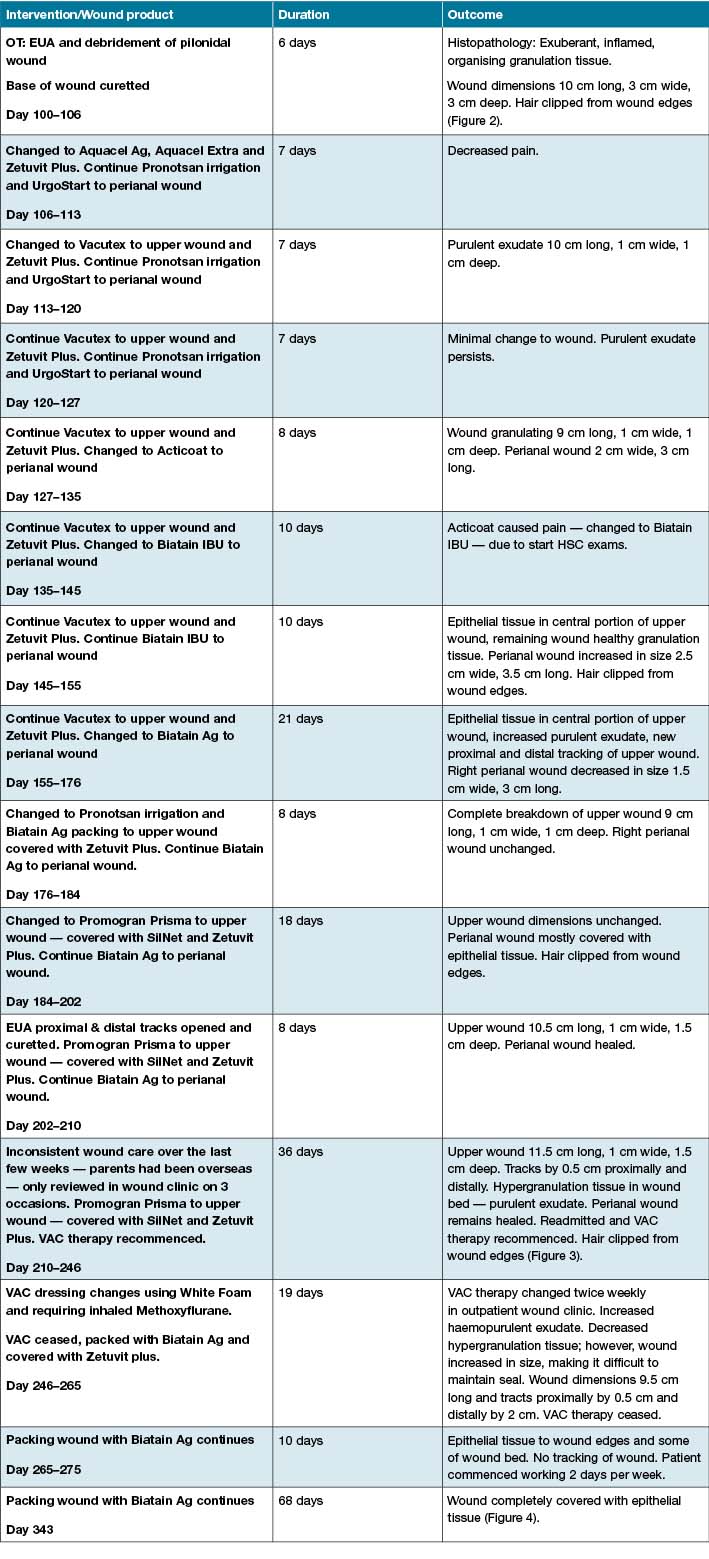

The wound infection persisted and was confirmed with microbial wound culture. The infection in the wound sinus where the ribbon gauze had been packed resulted in further breakdown of the wound, leading to the development of a subcutaneous extension in a caudal direction towards the anus with a skin bridge between the two wounds. This second wound was <1 cm from the anus. Having two wounds complicated the dressing regime and the proximity to the anus made keeping the wound free from faecal contamination challenging (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Day 35 — breakdown of the distal end of the sinus track

Initially the wound was irrigated with saline and packed with a silver hydrofibre (Aquacel Ag® — see Table 2). Oral antibiotics and analgesics were prescribed. Daily reviews were conducted by either the colorectal surgeon or STN and the patient’s mother was taught how to attend to wound dressings. An examination under anaesthesia (EUA) was arranged for the following week where the wound was washed out and a VAC® (Vacuum-assisted closure — topical negative pressure wound therapy — TNPWT) dressing was applied. The TNPWT was changed in the operating theatre on the first 3 occasions, as general anaesthetic was required due to severe pain and the difficulty of creating a seal with the distal wound being <1 cm from the anus. A Coloplast Brava® Ring was used to seal around anus. Brava® Rings were selected for their adhesion and durability, they have minimal breakdown with moisture due to the composition of hydrocolloids and ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) co-polymers5.

In an effort to minimise disruption to the patient’s routine, treatment was primarily done on an outpatient basis with most surgical procedures and/or dressing changes performed as day-only cases. The patient continued to attend school with TNPWT. After the first three dressing changes in the operating theatre, subsequent changes were attended in the Stomal Therapy Outpatient Clinic with Methoxyflurane inhaled analgesia for pain relief. Self-administered methoxyflurane inhalation has strong analgesic properties which met the requirements for this patient and dressing changes were well tolerated. Inhaled methoxyflurane should be limited to a maximum daily dose of 6 ml and a total of 15 ml weekly. Use on consecutive days is not recommended and inhaled Methoxyflurane is contraindicated in patients with renal failure or renal impairment6. This patient required 3 ml of inhaled Methoxyflurane for each TNPWT dressing change and this was limited to twice weekly, with renal function checked weekly. Caution should be taken with the ongoing prescription of narcotics and their use should be tapered as appropriate and the use of medications such as inhaled Methoxyflurane can be useful for managing the acute pain experienced during dressing changes. VAC® white foam was used as it was less painful on removal than VAC® Granufoam. TNPWT continued for 28 days.

Appropriate assessment of pain is important when treating chronic PNS disease as patients come to fear interventions and dressing changes7. This fear may manifest as depression which has been linked to the delayed wound healing or anxiety when anticipating pain during dressing changes7,8. Furthermore, delayed healing can result in emotions such as anger, frustration and uncertainty5. Physical inactivity may result from pain or apprehension about causing further trauma to the wound, this can lead to weight gain which may further negatively impact on the psychological wellbeing of some patients8. A chronic PNS wound can affect many aspects of the patients life including, work/education, leisure/sporting ventures and social activities5. Therefore, clinicians should incorporate a mental health assessment into the treatments plan and encourage patients to maintain self-care, independence and their usual routine where feasible.

PNS wounds have been shown to affect the psychological wellbeing of some patients7,8 and this patient initially saw an adolescent Psychologist. A subsequent referral was made to a Clinical Psychologist within our hospital when the need for further assistance was identified. The patient was then referred to an external, age appropriate counselling service for ongoing care.

After 41 days of treatment a family conference was held with the patient, his parents, the colorectal surgeon, a plastic surgeon and the STN, to discuss surgical interventions such as a Rhomboid or VY flap and the possible complications. The decision to continue with conservative wound therapy was agreed upon as the preferred option. The possibility of hyperbaric oxygen therapy was discussed as an option if conservative wound treatments were unsuccessful. A time line of wound progress, interventions and the wound therapies implemented has been included as Table 1. Table 2 highlights the intended action of the wound care products used, providing the rationale for their introduction.

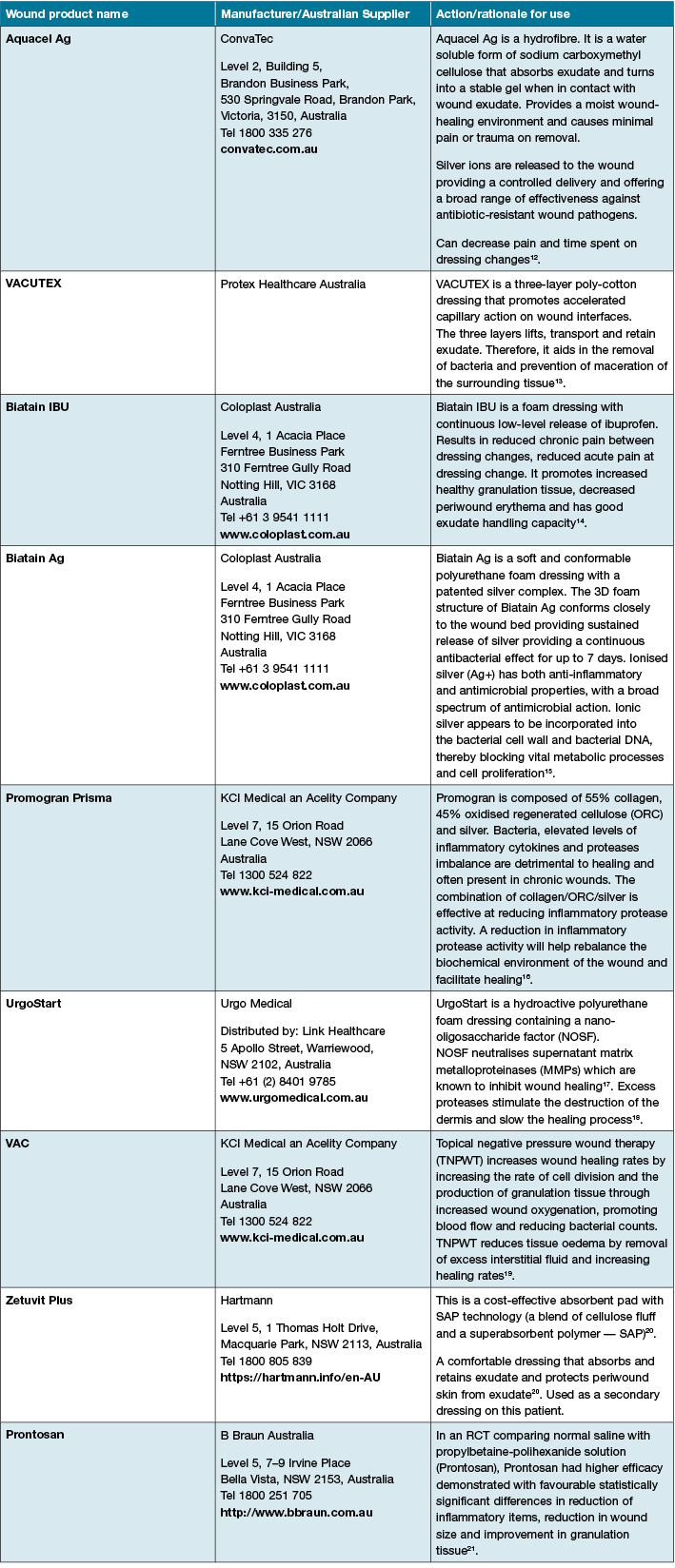

The patient was readmitted with increased pain and fevers after 91 days and underwent another EUA, debridement, curettage and washout (Figure 2). A third opinion was sought from a colorectal surgeon at another institution and the patient was advised to undergo a colostomy and flap reconstruction. It was determined a colostomy would be required due to the proximity of the wound to the anus (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Day 100 — following EUA debridement, curettage and washout

After 162 days the epithelial tissue that had covered some of the upper wound edges and base completely broke down leaving a 9 cm long upper wound, with the distal wound now measuring 3 x 1.5 cm. A further EUA and curette was performed and the wound was packed with Promogran Prisma®. Biatain Ag® (silver polyurethane foam dressing) was continued on the right perianal wound as there was finally some improvement being seen (Table 1).

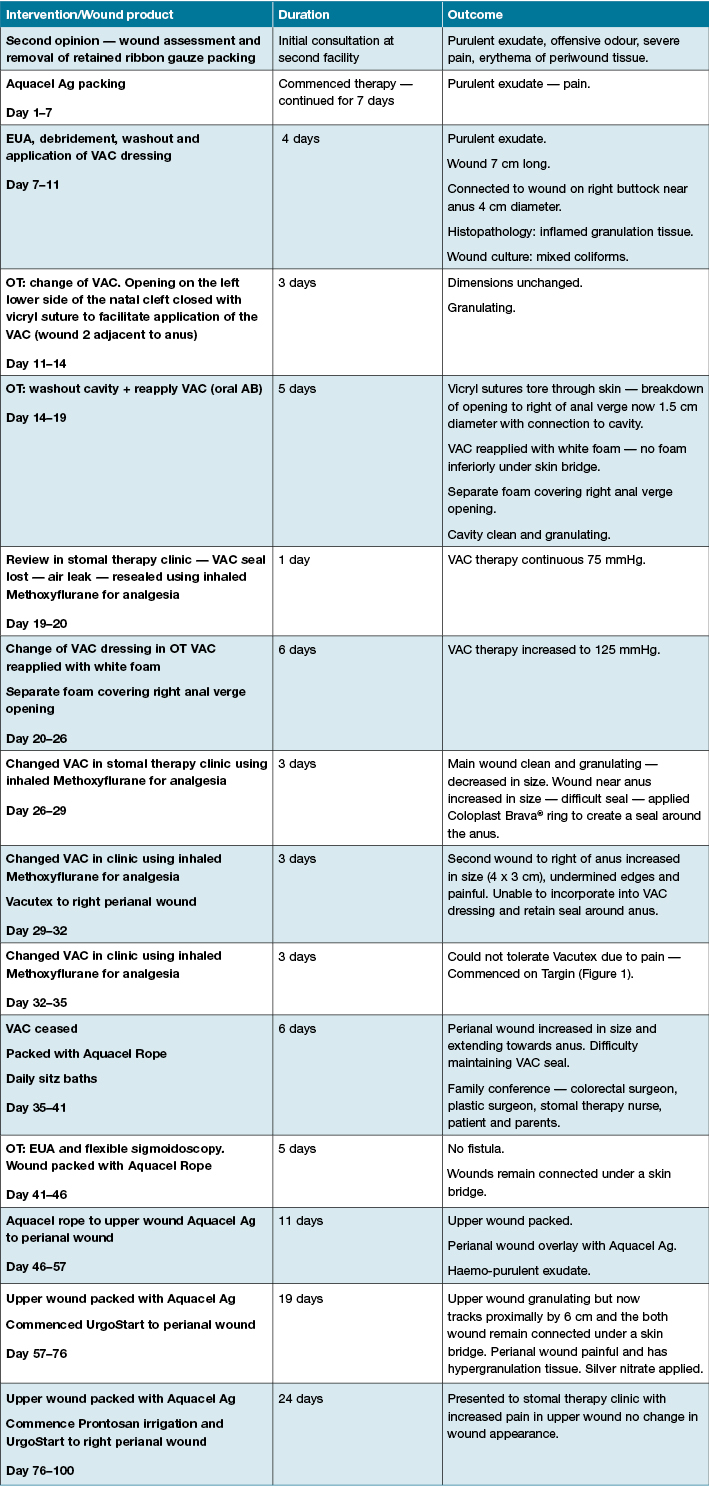

Table 1: Interventions, duration and outcomes

Table 1 (continued): Interventions, duration and outcomes

After 43 days of using Promogran Prisma®, there had been no improvement in the upper wound; however, the distal, right perianal wound that had been dressed with the silver polyurethane foam dressing for just 24 days was now covered with epithelial tissue. The patient was readmitted to the colorectal unit and the proximal wound was soaked in Prontosan® prior to the recommencement of TNPWT (Figure 3). The following day the patient was discharged with subsequent dressing changes attended in the Stomal Therapy Outpatient Clinic with Methoxyflurane used for analgesia. Dressing changes were well tolerated and TNPWT continued for 18 days. The TNPWT was ceased due difficulty maintaining a seal and moisture-associated dermatitis to periwound skin. Wound packing with the silver polyurethane foam dressing was commenced, with the patient’s mother changing dressings twice daily due to exudate levels and twice weekly reviews in the Stomal Therapy Outpatient Clinic were maintained. Within 10 days of changing to the silver polyurethane foam dressing epithelial tissue began to appear in the wound bed and after 94 days the wound was finally healed, this was 343 days from the initial consultation (Figure 4). This healing time is substantially longer than the reported healing time of 21–72 days following laying open and curettage of PNS tracks9.

Figure 3: Day 238 — wound progress, perianal wound healed

Figure 4: Day 343 — wound closure achieved

Table 2: Wound products, supplier and intended action

In this case the patient was initially reviewed daily, this was reduced to twice weekly, then weekly until wound closure was achieved. After the wound was completely healed the patient was referred for laser hair removal. Small studies have shown decreased recurrence of PNS following laser epilation9, whereas razor hair removal (shaving) can potentially increase the risk of long-term recurrence11.

What this paper adds:

Patients and their families benefit from ongoing review and communication with their surgeon and wound care specialist regarding wound progress and the rationale for alterations in the treatment plan. Consistency in the team caring for the patient enables the early recognition of changes to the wound and early intervention when required. A pain assessment and psychological assessment should be routinely incorporated into the treatment plan, with referral to the pain service or psychologist as appropriate. Inhaled Methoxyflurane can be used to effectively manage acute pain during dressing changes in the outpatient setting. The wound care product that led to the most significant improvement in both the wounds documented in this case was the silver polyurethane foam dressing; however, further studies into the effectiveness of this product in treating chronic PNS disease are required.

Conclusion

Ideally a short acute hospital admission is all that will be required follow the initial surgical intervention for PNS disease. Subsequent care can be continued on an outpatient basis with the intention of minimising disruption to activities of daily living such as work/study, leisure and social activities. Patients require access to consistent outpatient services for ongoing care and review. If the wound fails to heal and becomes chronic, further investigations and interventions must be conducted. Patients require education regarding wound hygiene, the rationale for the interventions performed and the wound products chosen. Finally, the psychological impact of having a chronic wound should not be underestimated and should be assessed as part of routine care with appropriate referrals made for supportive care.

Acknowledgements:

We wish to thank the patient for consenting to sharing his story and photographs. Further, we would like to acknowledge the contribution of his mother for her dedication to providing ongoing wound care. The wound had superficial breakdown after 4 months, with the development of a 1 cm long 0.5 cm deep ulcer. This took 36 days to heal. A further 6 months later another 1 cm long opening occurred in the centre of the previous PNS scar, this healed after 33 days. Both recurrent wounds were treated by clipping surrounding hair, removal of hair and foreign material from the wound bed, daily irrigation with Pronotsan® and overlaying with Biatain Ag®.

Author(s)

Ian Whiteley*

MClinNurs

Nurse Practitioner — Stomal Therapy

Concord Repatriation General Hospital

Hospital Road, Concord, NSW 2139, Australia

Clinical Senior Lecturer

The University of Sydney, Sydney Nursing School

Email ian.whiteley@sswahs.nsw.gov.au

Anil Keshava

MBBS, MS, FRACS

Clinical Associate Professor

Concord Institute of Academic Surgery

Concord Clinical School

University of Sydney, Hospital Road

Concord, NSW 2139, Australia

Email anilkeshava@gmail.com

* Corresponding author

References

- de Parades V, Bouchard D, Janier M, Berger A. Pilonidal sinus disease. J Visc Surg 2013;150(4):237–47.

- McCallum IJ, King PM, Bruce J. Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;336(7649):868–879.

- AL-Khamis A, McCallum IJ, King PM & Bruce J. Healing by primary versus secondary intention after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; Issue 1. Art. No.: CD006213. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006213.pub3.

- Lund J, Tou S, Doleman B & Williams JP. Fibrin glue for pilonidal sinus disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; Issue 1. Art. No.: CD011923. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011923.pub2.

- Brava® Mouldable Rings: A durable ring for reduced leakage. Coloplast Pty Ltd — product information and resources Website. http://www.coloplast.com.au/brava-mouldable-ring-en-au.aspx#section=product-description_3 (accessed September 5, 2016).

- Gaskell AL, Jephcott CG, Smithells JR, Sleigh JW. Self-administered methoxyflurane for procedural analgesia: experience in a tertiary Australasian centre. Anaesthesia 2016;71:417–423.

- Bradley L. Pilonidal sinus disease: a review. Part two. J Wound Care 2010;19(12):522–530.

- Stewart AM, Baker DJ, Elliott D. The psychological wellbeing of patients following excision of a pilonidal sinus. J Wound Care 2012;21(12):595–600.

- Garg P, Menon GR, Gupta V. Laying open (deroofing) and curettage of sinus as treatment of pilonidal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZ J Surg 2016;86:27–33.

- Ghnnam WM, Hafez DM. Laser hair removal as adjunct to surgery for pilonidal sinus: our initial experience. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2011;4(3):192–195.

- Petersen S, Wietelmann K, Evers T, Huser N, Matevossian E, Doll D. Long-term effects of postoperative razor epilation in pilonidal sinus disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52(1):131–134.

- Huang SH, Lin CH, Chang KP et al. Clinical evaluation comparing the efficacy of Aquacel Ag with Vaseline gauze versus 1% silver sulfadiazine cream in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Adv Skin Wound Care 2014;27(5):210–215.

- Russell L, Deeth M, Jones HM, Reynolds T. VACUTEX capillary action dressing: A multicentre, randomized trial. Brit J Nurs 2001;10(11):S66–70.

- Sibbald RG, Coutts P, Fierheller M, Woo K. A pilot (real-life) randomised clinical evaluation of a pain-relieving foam dressing: (ibuprofen-foam versus local best practice). Int Wound J 2007;4(1):16–23.

- Leaper D, Munter C, Meaume S et al. The use of Biatain Ag in hard-to-heal venous leg ulcers: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2013;8(7):1–7.

- Gottrup F, Cullen BM, Karlsmark T, Bischoff-Mikkelsen M, Nisbet L, Gibson, MC. Randomized controlled trial on collagen/oxidized regenerated cellulose/silver treatment. Wound Repair Regen 2013;21:1–10.

- Augustin M, Herberger K, Kroeger K, Muenter KC, Goepel L, Rychlik R. Cost-effectiveness of treating vascular leg ulcers with UrgoStart and UrgoCell Contact. Int Wound J 2014;13(1):82–87.

- Shanahan DR. The Explorer study: the first double-blind RCT to assess the efficacy of TLC-NOSF on DFUs. J Wound Care 2013;22(2):78–82.

- Tansarli GS, Vardakas KZ, Stratoulias C, Peppas G, Kapaskelis A, Falagas ME. Vacuum-assisted closure versus closure without vacuum assistance for preventing surgical site infections and infections of chronic wounds: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Infect 2014;15(4):363–367.

- Kaspar D. Zetuvit® Plus tested in clinical practice. Dealing effectively with heavily exuding wounds. Wound Forum 2010;10:6–8. http://www.hartmann.co.uk/images/Wound_Forum_A4_Issue_10.pdf Accessed August 29, 2016

- Bellingeri A, Falciani F, Traspedini P et al. Effect of a wound cleansing solution on wound bed preparation and inflammation in chronic wounds: a single-blind RCT. J Wound Care 2016;25(3):160–166.