Volume 25 Number 3

Resources for optimising wound outcomes in low-resource settings

Laura L Bolton

Keywords Wound care, low-resource settings

Abstract

Individuals with wounds deserve quality care and outcomes even if they live in low-resource settings (LRS). Those planning to provide LRS wound care services can enhance their experience and optimise patient and wound outcomes by learning as much as possible in advance about patient and wound challenges they will face, the environment and policies of practice and safe, effective interventions for wound care likely to be available. This work identifies resources to inform and equip wound care professionals for successful practice to make a sustainable difference to patients with wounds in LRS. Wound care practice pearls about how to prepare and how to improve outcomes with limited resources are summarised from The World Health Organization paradigm for practice innovation in LRS. The Wound Healing and Management (WHAM) node of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) collaborating with the Western Australia Centre for Evidence-Informed Health Care Practice offers Evidence Summaries for safe, effective interventions such as hydrogen peroxide, acetic acid, banana leaves or boiled potato peels that can be a vital resource for anyone considering practice in an LRS. These are supplemented with an interim summary of randomised controlled evidence supporting aloe vera and honey.

Introduction

Injuries such as wounds and lacerations accounted for 11% of the global burden of disease in 20101, and are associated with a substantial, growing burden of disability1,2. They can be especially challenging to manage in low-resource settings (LRS), defined as settings where local “health care resources (financial and human) are scarce”3, whether they occur in rich or under-resourced countries. To address these challenges, the World Health Organization (WHO) has encouraged governments and non-government organisations to integrate their knowledge, resources and initiatives across settings to improve wound and related lymphoedema outcomes around the world. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 3% of all volunteers are involved with medical care4, despite increasing needs for volunteers to meet medical care needs due to economic challenges. Volunteers are in demand in LRS whether they occur in distant countries or without leaving home in economically stressed areas.

Purpose

The purpose of this work is to introduce readers planning to provide innovative wound care in an LRS to techniques for successful volunteering recommended by the WHO, volunteering resources and wound care evidence that can prepare them for an interval of mutually enriching service that offers both those served and those serving sustainable benefit.

World Health Organization Paradigm for Success

For those facing the challenge of managing wounds in an LRS, two important resources summarised below for wound care can help optimise services provided. First, consistently practising the five World Alliance for Wound and Lymphedema (WAWLC) basic wound care principles favours improved wound care

— protect the wound from trauma

— promote a clean wound base and control infection

— maintain a moist wound environment

— enhance systemic conditions

— control periwound lymphoedema/oedema.

A second way to optimise enduring value of LRS service is to use the WHO time-tested paradigm for improving outcomes for wounds and chronic conditions3. It can serve as a primer for what to learn and prepare before one serves in an LRS, what to do while there, and what to leave behind in the LRS that will sustain improved wound outcomes long after one returns home:

(1) Learn in advance about special wound challenges and opportunities in the planned LRS setting. In addition to communicating with the setting host, learn all you can from online searches focused on the planned LRS setting. Volunteers can discover opportunities online (for example, http://createthegood.org/volunteer-search) or receive valuable orientation and learn more about their destination’s health care system challenges, opportunities, requirements and customs from organisations such as:

a. Health Volunteers Overseas (website)

b. Health Care Volunteer (http://www.healthcarevolunteer.com/home),

c. Doctors Without Borders (Medicines Sans Frontiers: website),

d. Red Cross (http://www.redcross.org/volunteer/become-a-volunteer#step1)

(2) Gain familiarity with the decision making process in the planned LRS, as well as current practice preferences and taboos. Knowing who makes wound care decisions and how they are made can contribute greatly to an inspiring interval of practice and mutual education that makes a sustainable difference to patients, to the LRS community and all involved. The old adage “listen first, then be listened to” applies in all endeavours. Appreciating cultural beliefs and attitudes5 can help one understand and harmonise with reasons why patients, families and local health care workers do what they do or don’t do. For example those who, believe that the “badness of the disease” is excreted through the wound may wonder where the badness goes if the wound is closed. Preparing a consistent explanation that nature will allow the wound to close only after the wound’s “bad” cause is resolved may mesh with local beliefs. Identify and build relationships with local caregivers, opinion leaders and community leaders. Approaching the experience with a mind open to discover practice pearls within the LRS while sharing pearls from one’s own experience may surprise those who serve and those served.

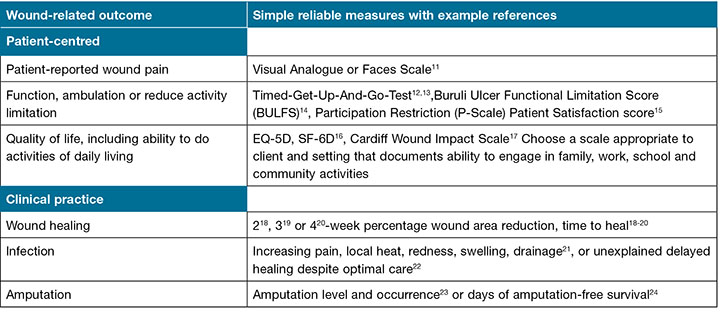

(3) Prepare a registry to monitor outcomes across settings to the extent possible by identifying local structures in place that foster consistency of care. Even paper and pencil registries can help assure that important patient wound-related hygiene, preventive and treatment care and outcomes are consistently practised and monitored across all patient settings. Monitoring clinical wound healing and infection rates and patient-centred outcomes, such as pain, limited mobility or quality of life can inform those who serve in an LRS, whether wound outcomes are improving or not as a result of practised interventions. Integrating care across settings helps resolve local hygiene wound causes and challenges6,7. Consistently documenting outcomes like healing progress, incidence of infection, patient-reported pain, mobility or other outcomes that affect quality of life can provide feedback for caregivers and patients. Feedback about patient and wound progress can hearten patients and encourage caregivers and local health care opinion leaders and administrators to support effective practices. For example, feedback about lack of chronic wound progress after four weeks alerted those involved in care to improve care and outcomes8. Examples of simple, low-cost, reliable, valid patient and wound measures that can inform clinical decisions and assess outcomes important to patients are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Example simple reliable, valid important measures of wound-related patient-centred or clinical practice outcomes10

(4) Align health care sectors that may influence wound prevention, such as private village health workers and traditional healers, so that all reinforce each other’s wound prevention and treatment practices. Engaging population-based activities in collaboration with other government sectors to encourage simple practices such as consistent use of footwear, preventive hygiene practices and early diagnosis can reduce morbidity, disability and socio-economic burden of Buruli ulcers9.

(5) Promote basic skills training for health care workers7 to help patients manage wounds with clean moisture-retentive dressings that minimise dressing frequency, pain, healing time and likelihood of infection, without the hazards of cross contamination associated with hand washing and reusing bandages. Document progress, outcomes and consistency of these wound management processes for patients across settings and multiple care givers. Assure that all know cues to look for and how, when and to whom to refer the patient for specialist care in time to avoid serious complications. For example, when pain can no longer be managed with a patient-appropriate dose of acetaminophen alternated with meal-time ibuprofen, consider consulting a specialist to manage the pain and its underlying cause.

(6) Engage patients and families in wound self-management with appropriate instruction during health care interactions, so they help maintain consistency and quality of wound care.

(7) Work with community institutions and non-governmental organisations to ensure that patients with wounds and their families have adequate community support with needed services, such as dependable, adequately trained local health care workers and/or wound self-care training or similar training for family care-giver(s). Social services may be needed to provide transportation, time off work or child support during treatment. Successful wound care also requires an adequate supply of clean water, easy, nearby, low-cost access to supplies and materials for managing oedema, protecting feet and changing dressings. Arrange for institutions to exchange information needed for consistent support of patient and family wound care needs and support their role in planning wound care services and making policies.

(8) Emphasise prevention (for example, good nutrition, hygiene, appropriate physical activity, reduced tobacco and alcohol use) and a healthy lifestyle as key components of wound care. This can occur in primary health care visits, in training health workers and as community organisations engage the local population.

What to know before you go

Before engaging in practice in any LRS, it is wise to learn what kinds of wounds one will be expected to manage and what resources are available that work safely to manage those wounds. The World Health Organization25 and other sources26 provide rich sources of information about managing wounds and lymphoedema. In addition, the Joanna Briggs Institute has in-depth Evidence Summaries27 describing the safety and efficacy of low-resource interventions including the following topical interventions:

- wound dressings (banana leaves or potato peels)

- wound cleansing (clean tap water)

- topical antiseptics (iodophors, hydrogen peroxide, chlorhexidine compounds, citric or acetic acid or tea tree oil)

- odour management (green tea bags).

These peer-reviewed Evidence Summaries, each based on a comprehensive systematic literature search, can be accessed at the Low-Resource Section of the Wound Healing and Management (WHAM) website node hosted by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) in collaboration with the Western Australia Centre for Evidence-Informed Health Care Practice, Wounds Australia (formerly the Australian Wound Management Association) and Wound Management Innovation CRC.

JBI evidence summaries on boiled potato peels28, or banana leaves29 offer sustainable, low-cost, safe, effective moisture retentive wound dressings that allow faster healing with less pain compared to traditional gauze. Clean/unused plastic food wrap, perforated if needed, with a diaper or sanitary pad secondary dressing to manage excess exudate, can serve as a low-cost alternative affording faster healing than ointment-impregnated gauze30 or similar healing to that achieved using hydrocolloid, hydrogel or foam dressings31. Those who encourage use of such locally available, effective, low cost “practice pearls” will establish sustainable, economical practices that continue to improve wound care outcomes long after their interval of LRS service.

Literature Review Methods

The National Institutes of Health Library of Medicine MEDLINE reference database was searched from inception to 15 April 2017, for terms and synonyms for combined words “clinical AND wound AND randomised” in combination with each of the terms: “aloe vera” or “honey”. These were supplemented with accessible derivative studies and studies learned from proceedings of major wound organisation meetings. Studies were included if they described a randomised clinical trial of burns including radiation burns, traumatic injuries, surgical wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers or venous leg ulcers. Studies were excluded if they were quasi-randomised or non-randomised or on non-clinical wounds or wounds not listed in Table 2 or if they were redundant to a more recent report on the same subjects.

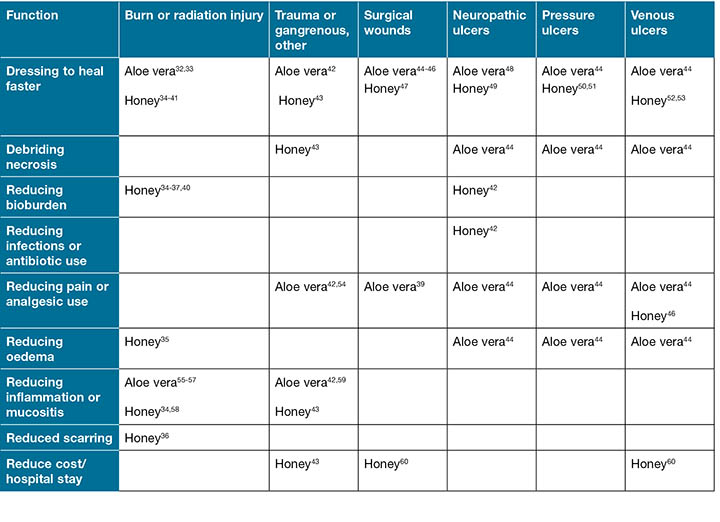

Table 2: RCT significant (p< 0.05) clinical evidence supporting efficacy for using aloe vera or honey on common clinical wounds

All included studies were tabulated according to the type of wound studied and all statistically significant (p< 0.05) effects on wound care outcomes are listed in Table 2, in order to address wound care professional and patient needs efficiently.

Literature Review Results

There is modest acute and chronic wound RCT support for using aloe vera or honey to reduce healing time, pain, oedema or inflammation, necrotic tissue, antibiotic use and length of hospital stays. (Table 2). These results should be interpreted with caution, as Table 2 contains only RCTs with significant clinical evidence supporting these two interventions. Both clearly supported faster healing compared to gauze dressings for healing acute or chronic wounds, with no RCT suggesting otherwise.

Discussion

Benjamin Franklin once said, “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail”. Turning this maxim to advantage, the more one prepares for practice in LRS, the more one sets the stage for success in improving patient and wound outcomes. Whether one is engaged in LRS wound care by necessity or as a volunteer, using the WHO principles and path to planning and preparing for LRS challenges can add valuable perspective and enhance the experiences of those who serve and outcomes of the patients and wounds served. Keys to success include appreciating and documenting patient, wound and environmental challenges to be faced and monitoring progress toward each wound care goal.

Recognising the environmental barriers and opportunities to engage in evidence-based practice using interventions at hand may not be easy, but can be inspiring and highly rewarding to patients, caregivers and all who serve them. Measuring important outcomes like those in Table 1 can motivate caregivers and patients or provide valuable feedback about delayed healing while there is still time to improve care and outcomes or refer to a specialist, if needed. Documented outcomes also tell LRS practitioners if they are making a difference to their patients. What reward could be greater?

Sound evidence61,62 supports using moisture-retentive dressings which favour healing and avoiding gauze dressings, which foster wound infection. The JBI WHAM Node LRS section provides valuable insight about moisture-retentive banana leaf or potato peel dressings and other wound care interventions at hand that may improve outcomes in many LRS. Table 2 informs readers of possible benefits from the use of honey and aloe vera often available in LRS. A limitation is that Table 2 summarises only significantly positive effects of honey or aloe vera demonstrated in an RCT. For perspective, using different topical treatment or radiation schedules or delivery formulations, several RCTs reported no effect of aloe vera on irradiated skin inflammation. One unreported RCT reported less inflammation using an alternative in a cream formulation63 compared to aloe vera gel, but it was unclear whether the difference was due to the cream as compared to the gel formulation or to lack of aloe vera gel effect. Cumulative radiation dose is an important source of variation that may also obscure aloe vera effects. Among patients receiving higher cumulative doses of radiation (> 2,700 cGy), Olsen et al.57 reported that the median time to radiation-induced skin changes was extended to five weeks by adding aloe vera topical treatment to a mild soap wash, compared to 3 weeks in subjects receiving soap alone. Similarly, honey may improve healing of more severe venous ulcers, without having consistent effects on less challenging ones52. Until sources of variability in wound outcomes are appropriately sorted out, a general conclusion from Table 2 is that honey and aloe vera can, under some circumstances, enhance the wound outcomes tabulated. Readers are encouraged to learn more in depth practical information about these and other LRS wound care interventions directly from the evidence summaries as they become available on the JBI LRS website.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the works of Joanna Briggs Institute pioneers Keryln Carville RN, STN(Cred) PhD, Professor, Domiciliary Nursing Silver Chain Nursing Association and Curtin University of Technology, and Robin Watts AM, RN, BA, MHSc, PhD, FRCNA, Emeritus Professor, School of Nursing and Midwifery — WACEIHP, Curtin University, and neglected tropical disease leaders Linda F Lehman, OTR/L, MPH, C.Ped, Technical Consultant, American Leprosy Missions and Mary Jo Geyer, PhD, PT, C.Ped. This work and the field of LRS practice have been enriched by their passion and dedication to empowering professionals to practise safe wound care that works.

Author(s)

Laura L Bolton

PhD

Adjunct Assoc Professor of Surgery, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson University Medical School,

New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

Email llbolton@gmail.com

References

- Burden of injuries avertable by a basic surgical package in low- and middle-income regions: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. World J Surg July 2014. Available at: http://www.healthdata.org/newsletters/impact-12/innovations (accessed April 23 2017)

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015 Aug 22;386(9995):743–800.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions. Geneva: WHO; 2002. Available at: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/icccreport/en/ (accessed April 23, 2017).

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. USDL Report 16-0363. Available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/volun.pdf (accessed April 3 2017).

- Nunnelee JD, Spaner SD. Explanatory model of chronic venous disease in the rural Midwest — a factor analysis. J Vasc Nurs 2000 Mar;18(1):6–10.

- Stocks ME, Freeman MC, Addiss DG. The effect of hygiene-based lymphoedema management in lymphatic filariasis-endemic areas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9(10):e0004171. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004171

- Lehman LF, Geyer MJ, Bolton LL. Ten steps: A guide for health promotion and empowerment of people affected by neglected tropical diseases. Greenville, SC: The American Leprosy Missions; July 2015. PDF accessed at http://www.leprosy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ALM-10Steps-FULLGUIDE-021816.pdf?x28937

- Kurd SK, Hoffstad OJ, Bilker WB, Margolis DJ. Evaluation of the use of prognostic information for the care of individuals with venous leg ulcers or diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17(3):318–25.

- WHO. Buruli ulcer: Objective and strategy for control and research. http://www.who.int/buruli/control/en/ (accessed April 23, 2017).

- Driver VR, Gould LJ, Dotson P et al. Identification and content validation of wound therapy clinical endpoints relevant to clinical practice and patient values for FDA approval. Part 1. Survey of the wound care community. Wound Repair Regen 2017 Apr 3. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 28370922.

- Freeman K, Smyth C, Dallam L, Jackson B. Pain measurement scales: a comparison of the visual analogue and faces rating scales in measuring pressure ulcer pain. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2001;28(6):290–6.

- Galán-Mercant A, Barón-López FJ, Labajos-Manzanares MT, Cuesta-Vargas AI. Reliability and criterion-related validity with a smartphone used in timed-up-and-go test. Biomed Eng Online 2014 Dec 2;13:156.

- Clegg A, Rogers L, Young J. Diagnostic test accuracy of simple instruments for identifying frailty in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2015 Jan;44(1):148–52.

- Stienstra Y, Dijkstra PU, Van Wezel MJ et al. Reliability and validity of the Buruli ulcer functional limitation score questionnaire. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005 Apr;72(4):449–52.

- Stevelink SA, Hoekstra T, Nardi SM et al. Development and structural validation of a shortened version of the Participation Scale. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34(19):1596–607.

- Shearer D, Morshed S. Common generic measures of health-related quality of life in injured patients. Injury 2011 Mar;42(3):241–7.

- Price P, Harding K. Cardiff Wound Impact Schedule: the development of a condition-specific questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life in patients with chronic wounds of the lower limb. Int Wound J 2004 Apr;1(1):10–7.

- van Rijswijk L, Polansky M. Predictors of time to heal deep pressure ulcers. Wounds 1994;6(5):159–165.

- Phillips TJ, Machado F, Trout R et al. and The Venous Ulcer Study Group. Prognostic indicators of venous ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:627–630.

- Sheehan P, Jones P, Caselli A, Giurini J, Veves A. Percent change in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4-week period is a robust predictor of complete healing in a 12-week prospective trial. Diabetes Care 2003;26(6):1879–1882.

- Petrica A, Brinzeu C, Brinzeu A, Petrica R, Ionac M. Accuracy of surgical wound infection definitions — the first step towards surveillance of surgical site infections. TMJ 2009;59(3–4):362–365.

- Rondas AA, Schols JM, Stobberingh EE, Price PE. Definition of infection in chronic wounds by Dutch nursing home physicians. Int Wound J 2009;6(4):267–74.

- Margolis DJ, Jeffcoate W. Epidemiology of foot ulceration and amputation: can global variation be explained? Med Clin North Am 2013 Sep;97(5):791–805.

- Benoit E, O’Donnell TF Jr, Kitsios GD, Iafrati MD. Improved amputation-free survival in unreconstructable critical limb ischemia and its implications for clinical trial design and quality measurement. J Vasc Surg 2012;55(3):781–9.

- J Macdonald, M Geyer (Eds). Wound and Lymphedema Management. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010, pp. 95–101.

- Bolton L. Improving wound and lymphoedema outcomes in low-resource settings. J Lymphoedema 2010;5(2):100–102.

- Joanna Briggs Institute, Wound Healing and Management Node, Low-Resource Section hosted by the Joanna Briggs Institute in collaboration with the Western Australia Centre for Evidence-Informed Health Care Practice and Wounds Australia (formerly the Australia Wound Management Association). http://connect.jbiconnectplus.org/ (accessed April 20, 2017)

- De Buck E, Van de Velde S. Potato peel dressings for burn wounds. Emerg Med J 2010;27(1):55–6.

- Gore M, Akolekar D. Evaluation of banana leaf dressing for partial thickness burn wounds. Burns 2003;29(5):487–92.

- Takahashi J, Yokota O, Fujisawa Y, Sasaki K, Ishizu H, Aoki T, Okawa M. An evaluation of polyvinylidene film dressing for treatment of pressure ulcers in older people. J Wound Care 2006 Nov;15(10):449–50, 452–4.

- Bito S, Mizuhara A, Oonishi S et al. Randomised controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of wrap therapy for wound healing acceleration in patients with NPUAP stage II and III pressure ulcer. BMJ Open 2012 Jan 5;2:e00037.

- Maenthaisong R, Chaiyakunapruk N, Niruntraporn S, Kongkaew C. The efficacy of aloe vera used for burn wound healing: a systematic review. Burns 2007 Sep;33(6):713–8.

- Khorasani G, Hosseinimehr SJ, Azadbakht M, Zamani A, Mahdavi MR. Aloe versus silver sulfadiazine creams for second-degree burns: a randomized controlled study. Surg Today 2009;39(7):587–91.

- Baghel PS, Shukla S, Mathur RK, Randa R. A comparative study to evaluate the effect of honey dressing and silver sulfadiazene dressing on wound healing in burn patients. Indian J Plast Surg 2009;42(2):176–81.

- Bangroo AK, Katri R, Chauhan S. Honey dressing in pediatric burns. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2005;10:172–5.

- Subrahmanyam M. Topical application of honey in treatment of burns. Br J Surg 1991;78(4):497–8.

- Subrahmanyam M. Honey impregnated gauze versus polyurethane film (OpSite) in the treatment of burns — a prospective randomised study. British J Plast Surg 1993a;46(4):322–3.

- Subrahmanyam M. Honey as a surgical dressing for burns and ulcers. Indian J Surg 1993b;55(9):468–73.

- Subrahmanyam M. Honey dressing for burns — an appraisal. Ann Burns Fire Disasters 1996a;IX(1):33–5.

- Wijesinghe M, Weatherall M, Perrin K, Beasley R. Honey in the treatment of burns: a systematic review and meta-analysis of its efficacy. N Z Med J 2009;122(1295):47–60.

- Subrahmanyam M. A prospective randomised clinical and histological study of superficial burn wound healing with honey and silver sulfadiazine. Burns 1998;24(2):157–61.

- Mansour G, Ouda S, Shaker A, Abdallah HM. Clinical efficacy of new aloe vera- and myrrh-based oral mucoadhesive gels in the management of minor recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Oral Pathol Med 2014;43(6):405–9.

- Subrahmanyam M, Ugane SP. Honey dressing beneficial in treatment of Fournier’s gangrene. Indian J Surg 2004;66(2):75–77.

- Dat AD, Poon F, Pham KB, Doust J. Aloe vera for treating acute and chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Feb 15;(2):CD008762.

- Molazem Z, Mohseni F, Younesi M, Keshavarzi S. Aloe vera gel and cesarean wound healing; a randomized controlled clinical trial. Glob J Health Sci 2014 Aug 31;7(1):203–9.

- Eshghi F, Hosseinimehr SJ, Rahmani N, Khademloo M, Norozi MS, Hojati O. Effects of aloe vera cream on posthemorrhoidectomy pain and wound healing: results of a randomized, blind, placebo-control study. J Altern Complement Med 2010 Jun;16(6):647–50.

- Al-Waili NS, Saloom KY. Effects of topical honey on post-operative wound infections due to gram positive and gram negative bacteria following caesarean sections and hysterectomies. Eur J Med Res 1999;4(3):126–30.

- Panahi Y, Izadi M, Sayyadi N et al. Comparative trial of aloe vera/olive oil combination cream versus phenytoin cream in the treatment of chronic wounds. J Wound Care 2015 Oct;24(10):459–60, 462–465.

- Kamaratos AV, Tzirogiannis KN, Iraklianou SA, Panoutsopoulos GI, Kanellos IE, Melidonis AI. Manuka honey-impregnated dressings in the treatment of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J 2012;9:1–7.

- Weheida SM, Nagubib HH, El-Banna HM, Marzouk S. Comparing the effects of two dressing techniques on healing of low grade pressure ulcers. Journal of the Medical Research Institute —Alexandria University 1991;12(2):259–278.

- Yapucu Güneş U, Eşer I. Effectiveness of a honey dressing for healing pressure ulcers. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34(2):184–90.

- Gethin G. Manuka honey versus hydrogel — a prospective, open label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial to compare desloughing efficacy and healing outcomes in venous ulcers. Unpublished PhD thesis 2007.

- Gulati S, Qureshi A, Srivastava A, Kataria K, Kumar P, Balkrishna Ji A. A prospective randomized study to compare the effectiveness of honey dressing vs povidone iodine dressing in chronic wound healing. Ind J Surg July 2012;1–7.

- Rahmani N, Khademloo M, Vosoughi K, Assadpour S. Effects of aloe vera cream on chronic anal fissure pain, wound healing and hemorrhaging upon defecation: a prospective double blind clinical trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014;18(7):1078–84.

- Sahebjamee M, Mansourian A, Hajimirzamohammad M et al. Comparative efficacy of aloe vera and benzydamine mouthwashes on radiation-induced oral mucositis: a triple-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Oral Health Prev Dent 2015;13(4):309–15.

- Di Franco R, Sammarco E, Calvanese MG et al. Preventing the acute skin side effects in patients treated with radiotherapy for breast cancer: the use of corneometry in order to evaluate the protective effect of moisturizing creams. Radiat Oncol 2013 Mar 12;8:57.

- Olsen DL, Raub W Jr, Bradley C et al. The effect of aloe vera gel/mild soap versus mild soap alone in preventing skin reactions in patients undergoing radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001;28(3):543–7.

- Song JJ, Twumasi-Ankrah P, Salcido R. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of honey to protect from the effects of radiation-induced oral mucositis. Adv Skin Wound Care 2012;25(1):23–8.

- Reddy RL, Reddy RS, Ramesh T, Singh TR, Swapna LA, Laxmi NV. Randomized trial of aloe vera gel vs triamcinolone acetonide ointment in the treatment of oral lichen planus. Quintessence Int 2012;43(9):793–800.

- Ingle R, Levin J, Polinder K. Wound healing with honey — a randomised controlled trial. S Afr Med J 2006;96(9):831–5.

- Brölmann FE, Eskes AM, Goslings JC et al.; REMBRANDT study group. Randomized clinical trial of donor-site wound dressings after split-skin grafting. Br J Surg 2013;100(5):619–627.

- Hutchinson J. McGuckin M. Occlusive dressings: A microbiologic and clinical review. Am J Infect Control 1990;18:257–68.

- Heggie S, Bryant GP, Tripcony L et al. A Phase III study on the efficacy of topical aloe vera gel on irradiated breast tissue. Cancer Nurs 2002;25(6):442–51.