Volume 26 Number 3

Evidence summary: Prevention of pressure injuries in individuals with overweight or obesity

Emily Haesler

April 2018

Question

What is the best available evidence on preventing pressure injuries (PIs) in individuals with overweight or obesity?

Summary

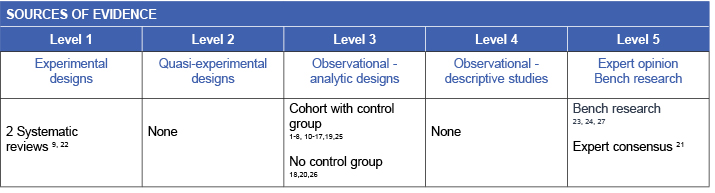

Overweight and obesity are excessive fat accumulation that can impair health status. Individuals with a body mass index (BMI) 25 to 30kg/m2 are classified as being overweight and those with a BMI of over 30 kg/m2 are classified as having obesity. These individuals are more likely to exhibit factors significantly associated with an increase in PI risk. Conducting a structured risk assessment1-20 (Level 3b evidence) and implementing individualised preventive strategies, including nutrition management21 (Level 5b evidence), provision of a pressure redistribution support surface22 (Level 1b evidence), and attention to positioning21, 23, 24 (Level 5 evidence) and skin care21, 23, 24 (Level 5 evidence) are cornerstone principles in reducing the risk of PI in individuals with overweight and obesity.

Clinical practice recommendations

- Conduct a structured risk assessment that considers factors that may increase the risk for PIs for an individual with overweight and obesity (Grade A).

- Refer individuals with overweight and obesity to an accredited practicing dietitian (APD) for a nutritional assessment and development of an appropriate nutrition management plan (Grade B).

- Assess skin and skin folds and perform preventive skin care (Grade B).

- Evaluate safety of equipment for bariatric use, select chairs and beds with adequate dimensions for safe repositioning and evaluate ‘bottoming out’ (Grade B).

- Provide a high specification pressure redistribution support surface (Grade A).

- Consider using a bed system with advanced microclimate technology (Grade B).

- Regularly reposition the individual using appropriate repositioning aids and encourage early mobilisation (Grade A).

Evidence

Pressure injury risk

Evidence on the relationship between increased weight and the incidence of PI is mixed, with some studies showing increased risk, some showing lower risk and some showing no significant influence of high BMI on PI risk21 (Level 5b evidence). The most recent evidence indicates that the risk of PI is significantly higher in individuals who are extremely obese compared to those of normal BMI (odds ratio 0.53, (95% confidence interval 0.33 to 0.85, p=0.009)4 (Level 3b evidence). However, all individuals with overweight and obesity are at increased risk of several factors associated with an increased risk of PI, including:

- Decreased mobility (particularly chair and bed mobility) resulting from difficulty distributing increased body weight. A majority of risk studies investigating the relationship show that reduced mobility is significantly associated with PIs1, 2, 10-12, 17, 25 (Level 3b evidence)

- Increased risk of friction and shear when repositioning due to restricted movement from increased body weight. Friction and shear are significantly associated with increased PI risk in about one third of studies exploring this relationship5, 6, 13, 16, 19 (Level 3.b evidence).

- Increased pressure load on skin and tissues due to increased tissue weight. Increased interface pressure is significantly associated with increased risk of PI in two studies.7, 18 (Level 3.b evidence).

- Increased risk for intertriginous dermatitis and other types of moisture-associated skin damage due to moisture from diaphoresis or incontinence accumulating in skin folds. Skin moisture is significantly associated with PI risk in about 60% of studies investigating the relationship3, 7, 15 (Level 3.b evidence).

- Increased risk of impairment of the vascular and lymphatic systems that support skin and tissues due to increased tissue weight. Reduced circulatory system function is associated with a significant increase in PI risk in about 50% of studies investigating the relationship2, 8, 14, 15, 17 (Level 3.b evidence).

Promoting nutrition

Promoting optimal nutritional status is associated with superior health outcomes, including preventing and healing PIs. There is no specific evidence on the efficacy of weight reduction in preventing or treating PIs. However, individuals with overweight and obesity are considered to be at increased nutritional risk that may require management21 (Level 5.b evidence).

Clinical guidelines recommend that individuals at risk of PIs who are assessed as having risk of malnutrition are provided with an individualised diet under the direction of an APD21 (Level 5.b evidence). An adequate energy intake, calculated using the Miffin-St Jeor equation9 (Level 1.b evidence) and adjusted based on the level of overweight or obesity21 (Level 5.b evidence), is recommended to prevent PIs.

Promoting skin integrity

Individuals with overweight and obesity are at risk of PIs in unexpected locations due to the excess weight of tissues. A regular skin assessment that includes all skin folds (e.g. behind the neck, under the pannus and breasts, perineal, buttock and scrotal region) should be conducted on a regular basis to identify areas at risk of PI21, 23, 24 (Level 5 evidence).

Regular preventive skin care should include:

- Management of moisture with regular skin cleansing, gentle drying and application of moisturiser21, 23, 24 (Level 5 evidence).

- Implementation of a continence management plan when applicable.21, 23

- Careful positioning and regular rotation (as applicable) of medical devices (e.g. tubes, catheters)21, 24 (Level 5 evidence).

- Identification and treatment of impairments to skin integrity from other causes (e.g. intertriginous dermatitis, fungal infection)21, 24 (Level 5 evidence).

Using appropriate equipment

Individuals with overweight and obesity may exceed the safe weight and dimensions for medical equipment. When selecting equipment including chairs, beds, wheelchairs, hoists and bathroom seats:

- Check that equipment is safe for bariatric use (e.g. any weight restrictions)21, 23 (Level 5 evidence).

- Assess the space between the individual and side rails/equipment features is sufficient for the individual to reposition. A recent observational study26 found that a standard 91 cm wide hospital bed provided insufficient space for an individual with a BMI > 35kg/m2 to turn without lateral repositioning. The study showed that for individuals who can turn independently, the minimum dimension for a hospital bed is 91 cm (up to BMI 45kg/m2), 102cm (up to BMI 55kg/m2) and 127cm (≥55kg/m2). Greater bed widths are required for safe repositioning of dependent individuals26 (Level 3e evidence).

- Evaluate support surfaces for ‘bottoming out’, which occurs when the surface provides insufficient support due to excessive immersion such that the individual is supported by the bed or chair base21 (Level 5b evidence).

There is no specific evidence on the efficacy of different support surfaces in preventing PI in individuals with overweight and obesity. A pressure redistribution support surface is associated with a decreased incidence of PI in a large range of patient demographics22 (Level 1b evidence), and is also recommended for individuals with overweight and obesity21 (Level 5b evidence).

In a small observational study (n=21) individuals with overweight or obesity (mean BMI 51.4 ± 10.3) used a low air-loss continuous rotation bariatric bed with advanced microclimate technology for an average of 4.8 days in a critical care unit. In these individuals, who were at high pressure injury risk, no new PIs occurred20 (Level 3e evidence).

Repositioning

Individuals with overweight and obesity are at greater risk of damage to the skin and tissues from shear and friction during repositioning. Extra weight can make it harder for the individual to self-position or for health professionals to move the individual without drag. To reduce this risk:

- Regularly re-positioning the individual. Non-blanchable erythema may present later in individuals with overweight or obesity as damage occurs in deeper tissue without visible skin signs27 (Level 5c evidence).

- Consider the 30 side-lying position with the pannus supported away from underlying tissue24 (Level 5c evidence).

- Use appropriate equipment to assist in repositioning (e.g. bariatric hoist) or when unavailable, ensure sufficient health professionals assist in repositioning to prevent injury to staff and the individual21, 24 (Level 5 evidence).

- Provide appropriate aids to assist individuals to self-position (e.g. overhead or side rails)21, 24 (Level 5 evidence).

- Educate individuals about strategies to self-position and encourage early mobilisation.

Methodology

This evidence summary is based on a structured database search combining search terms that describe pressure injuries with search terms related to bariatric individuals. Searches were conducted in EMBASE, Pubmed, Medline, Scopus and the Cochrane Library. Evidence published up to November 2017 in English was considered for inclusion.

Related evidence summaries

JBI 18874 Pressure injuries: Preventing heel pressure injuries with positioning

JBI 18875 Pressure Injuries: Preventing heel pressure injuries with prophylactic dressings

JBI 18873 Pressure injuries: Preventing medical device related pressure injuries

JBI 19261 Pressure injuries: Alternating pressure support surfaces

JBI 19262 Pressure injuries: Skin care

Author(s)

Emily Haesler

for Wound Healing and Management Node

References

- Bergquist-Beringer S, Gajewski BJ. Outcome and assessment information set data that predict pressure ulcer development in older adult home health patients. Adv Skin Wound Care, 2011;24(9):404-14. (Level 3b evidence).

- Okuwa M, Sanada H, Sugama J, Inagaki M, Konya C, Kitagawa A, Tabata K. A prospective cohort study of lower-extremity pressure ulcer risk among bedfast older adults. Adv Skin Wound Care, 2006;19(7):391-97. (Level 3b evidence).

- Bergquist S, Frantz R. Pressure ulcers in community-based older adults receiving home health care. Prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. AdvWound Care, 1999. Sep;12(7):339. (Level 3b evidence).

- Hyun S, Li X, Vermillion B, Newton C, Fall M, Kaewprag P, Moffatt-Bruce S, Lenz ER. Body mass index and pressure ulcers: Improved predictability of pressure ulcers in intensive care patients. Am J Crit Care, 2014;23(6):494-500. (Level 3b evidence).

- De Laat E, Pickkers P, Schoonhoven L, Verbeek A, Feuth T, Van Achterberg T. Guideline implementation results in a decrease of pressure ulcer incidence in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med, 2007;35(3):815-20. (Level 3b evidence).

- Halfens R, Van Achterberg T, Bal R. Validity and reliability of the braden scale and the influence of other risk factors: a multi-centre prospective study. Int J Nurs Stud, 2000;37(4):313-19. (Level 3b evidence).

- Suriadi, Sanada H, Sugama J, Kitagawa A, Thigpen B, Kinosita S, Murayama S. Risk factors in the development of pressure ulcers in an intensive care unit in Pontianak, Indonesia. Int Wound J, 2007;4(3):208-15. (Level 3b evidence).

- Kwong EW-y, Pang SM-c, Aboo GH, Law SS-m. Pressure ulcer development in older residents in nursing homes: influencing factors. J Adv Nurs 2009;65(12):2608-20. (Level 3b evidence).

- Frankenfield D, Roth-Yousey L, Compher C. Comparison of predictive equations for resting metabolic rate in healthy nonobese and obese adults: a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc, 2005;105(5):775-89. (Level 1b evidence).

- Berlowitz D, Wilking S. Risk factors for pressure sores. A comparison of cross-sectional and cohort-derived data. J Am Geriatr Soc, 1989;37(11):1043-50. (Level 3b evidence).

- Schnelle J, Adamson G, Cruise P, Al-Samarrai N, Sarbaugh F, Uman G, Ouslander J. Skin disorders and moisture in incontinent nursing home residents: intervention implications. J Am Geriatr Soc, 1997;45(10):1182-88. (Level 3b evidence).

- Allman R, Goode P, Patrick M, Burst N, Bartolucci A. Pressure ulcer risk factors among hospitalized patients with activity limitation. J Am Med Assoc, 1995;273(11):865-70. (Level 3b evidence).

- Perneger T, A.C. R, Gaspoz J, Borst F, Vitek O, C. H. Screening for pressure ulcer risk in an acute care hospital: development of a brief bedside scale. J Clin Epidemiol, 2002;55(5):498-504. (Level 3b evidence).

- Manzano F, Navarro MJ, Roldán D, Moral MA, Leyva I, Guerrero C, Sanchez MA, Colmenero M, Fernández-Mondejar E. Pressure ulcer incidence and risk factors in ventilated intensive care patients. J Crit Care, 2010;25(3):469-76. (Level 3b evidence).

- Compton F, Hoffmann F, Hortig T, Strauss M, Frey J, Zidek W, Schafer JH. Pressure ulcer predictors in ICU patients: nursing skin assessment versus objective parameters. Journal of Wound Care, 2008;17(10):417. (Level 3b evidence).

- Tescher AN, Branda ME, Byrne TJ, Naessens JM. All At-Risk Patients Are Not Created Equal: Analysis of Braden Pressure Ulcer Risk Scores to Identify Specific Risks. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 2012. May;39(3):282-91. (Level 3b evidence).

- Olson B, Langemo D, Burd C, Hanson D, Hunter S, Cathcart-Silberberg T. Pressure ulcer incidence in an acute care setting. Journal of Wound,Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 1996;23(1):15-20. (Level 3b evidence).

- Suriadi, Sanada H, Sugama J, Thigpen B, Subuh M. Development of a new risk assessment scale for predicting pressure ulcers in an intensive care unit. Nurs Crit Care, 2008. Jan-Feb;13(1):34. (Level 3e evidence).

- Tourtual D, Riesenberg L, Korutz C, Semo A, Asef A, Talati K, Gill R. Predictors of hospital acquired heel pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Management, 1997;43(9):24-34. (Level 3b evidence).

- Pemberton V, Turner V, VanGilder C. The effect of using a low-air-loss surface on the skin integrity of obese patients: results of a pilot study. Ostomy/Wound Management, 2009;55(2):44-8. (Level 3e evidence).

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. Haesler E, editor. Osborne Park, Western Australia: Cambridge Media; 2014.(Level 1b and 5b evidence).

- McInnes E, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SEM, Dumville JC, Middleton V, Cullum N. Support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015;9(CD001735). (Level 1b evidence).

- Rush A, Muir M. Maintaining skin integrity bariatric patients. Br J Community Nurs, 2012. Apr;17(4):154, 6-9. (Level 5c evidence).

- Phillips J. Care of the bariatric patient in acute care. J Radiol Nurs, 2013. March;32(1):21-31. (Level 5c evidence).

- Nijs N, Toppets A, Defloor T, Bernaerts K, Milisen K. Incidence and risk factors for pressure ulcers in the intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs, 2009;18(9):1258-66. (Level 3b evidence).

- Wiggermann N, Smith K, Kumpar D. What Bed Size Does a Patient Need? The Relationship between Body Mass Index and Space Required to Turn in Bed. Nurs Res, 2017;66(6):483-9. (Level 3e evidence).

- Levy A, Kopplin K, Gefen A. A Computer Modeling Study to Evaluate the Potential Effect of Air Cell-based Cushions on the Tissues of Bariatric and Diabetic Patients. Ostomy Wound Management, 2016. Jan;62(1):22-30. (Level 5c evidence).