Volume 26 Number 3

Evidence summary: Skin care to reduce the risk of pressure injuries

Emily Haesler

Keywords pressure injury, pressure ulcer, decubitus ulcer, skin care, massage, cleansing, moisturising

Question

What is the best available evidence on skin care to reduce the risk of pressure injuries?

Summary

Preventive skin care incorporates a range of strategies that reduce risk factors for PIs. Selection of appropriate interventions should be based on an individualised assessment, and include cleansing1 and moisturising2 (Levels 1c & 2d evidence), reducing moisture3, 4 (Levels 1c & 3c evidence) and avoiding massage5 (Level 1c evidence).

Clinical practice recommendations

- Use a pH balanced cleanser to promote healthy skin. (Grade B)

- Use a moisturiser to maintain moisture balance and reduce the risk of skin damage. (Grade B)

- Protect the skin from moisture sources (e.g. incontinence) to reduce the risk of skin damage. (Grade B)

- Avoid skin massage to reduce the risk of skin damage. (Grade B)

Evidence

A comprehensive skin regimen that includes best practice recommendations and preferences of the individual promotes the best clinical outcomes for people at risk of PIs.

A cohort with control group study reported on a comprehensive skin care regimen that included gentle skin cleansing, moisturiser applied after bathing, barrier cream, a faecal continence management device, continence pads, avoiding massage and regular skin assessment. Compared to a standard care group, the comprehensive skin regimen group had significant reduction in PIs (13.2% versus 50%, p=0.001)6 (Level 3c evidence).

Cleansing

Maintaining clean, dry skin is a foundation principle in skin care.7 Consensus opinion is that skin should be cleansed with a pH balanced cleanser. A pH balanced cleanser reduces skin irritation and dryness, reducing the risk of impaired skin integrity7, 8 (Level 5b and 5c evidence).

One randomised controlled trial (RCT)1 has compared the impact of cleansers on PI incidence. In a small trial (n=93) a standard 1% aqueous soap solution with an alkaline pH was compared with a foam no-rinse, pH balanced, emollient-containing cleanser. After14 days of use, significantly more individuals with Category/Stage 2 PIs or greater experienced improvement in or maintenance of skin condition (p=0.05)1 (Level 1c evidence).

Moisturising

Maintaining hydrated skin is a foundation principle in skin care.7 When skin is inadequately hydrated, the risk of PI increases9 (Level 1b evidence).

A quality improvement study demonstrated that a comprehensive skin management plan that included a skin emollient was more effective than a similar management plan without a moisturiser or emollient component. After implementing the new skin care regimen in an in-patient wound centre there was a significant (p=0.008) reduction in PIs and a significant cost saving demonstrated2 (Level 2.d evidence).

In one RCT, a moisturiser of hyper-oxygenated fatty acids applied every 12 hours for 14 days was not significantly different to a placebo cream for preventing PIs in individuals at high risk10 (Level 1c evidence). Another study compared a hyper-oxygenated fatty acid moisturiser to olive oil and found no significant difference between the two products for reducing PIs11 (Level 1c evidence). A third RCT (n=164) comparing a hyper-oxygenated fatty acid moisturiser to a perfumed glycerol-based product reported significant reduction in in sacral, trochanter and heel PIs when the fatty acid moisturiser was applied twice daily for 30 days12 (Level 1c evidence). Although these findings are mixed, none of these trials provided a strong evaluation of the efficacy of moisturising versus not moisturising, and all had significant limitations.

Reducing moisture exposure

There is a greater risk of PI when skin is exposed to moisture in conjunction with pressure and/or shear9 (Level 1b evidence). The most common sources of moisture at the skin surface are incontinence, perspiration and wound exudate13 (Level 5b evidence). Strategies to reduce exposure to excessive moisture that have been explored with respect to PI incidence include continence management and application of barrier creams.

Continence management

An RCT (n=200) that explored a positioning device that elevated the perianal area, thereby increasing ability to perform continence care and reducing skin exposure to faecal incontinence, was associated with a significant reduction in skin breakdown compared with regular continence care (11% versus 39%, p<0.001). Although the use of such a suspension device may not be possible in most clinical areas, the findings demonstrated that maintaining strict perianal hygiene in individuals with faecal incontinence can reduce PIs4 (Level 1c evidence).

A small RCT (n=59) compared two different faecal management systems to usual care for reducing PIs. A zinc-based barrier cream was used for the usual care group and the intervention groups received either a bowel management catheter or a rectal trumpet. Pressure injury rates were not significantly different between either faecal bowel management system and using a barrier cream,14 although the researchers acknowledge numerous methodological limitations (Level 1c evidence).

A single group cohort study evaluated the use of high absorbency continence pads for improving health-related quality of life for incontinent individuals in rehabilitation. Although no significant difference in PIs was observed after two weeks, there was a 67% decrease in facility-acquired PIs after ten intervention weeks (95% confidence interval [CI] 16% to 78%)3 (Level 3e evidence)

Barrier cream

In a small case series (n=20), not all of whom had PIs), strategies to protect the skin from moisture, including use of a spray-on barrier cream and a faecal management system for individuals with loose stools were associated with 85% of moisture lesions with and without erythema/ PIs being classified as healed after 3 to 28 days. Some individuals also received a prophylactic dressing, which may have contributed to the results15 (Level 4e evidence).

Massage

Consensus opinion is that massage and vigorous rubbing of the skin is more likely to cause skin/cellular/blood vessel damage and tissue inflammation than to promote beneficial outcomes associated with massage (such as increased tissue blood flow)8, 16 (Level 5b evidence).

One RCT5 specifically explored the relationship between massage and PI development. The three randomised study groups received a placebo cream, massage with a topical antioxidant cream, or position change with no massage. There was no benefit in reducing PIs associated with massage, with those individuals who received no massage having a non-significant superior outcome (odds ratio [OR] 0.636 versus 1.136 for massage with placebo)5 (Level 1c evidence).

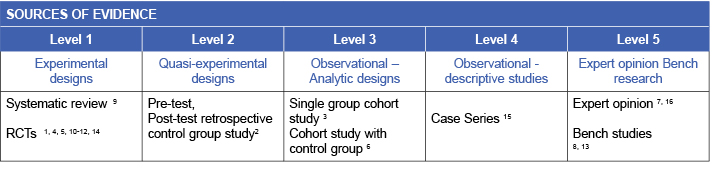

Methodology

This evidence summary is based on a structured database search combining search terms that describe pressure injuries with search terms related to massage, cleansing, moisturising, and preventive skin practices. Searches were conducted in EMBASE, Pubmed, Medline, Scopus and the Cochrane Library. Evidence published up to June 2017 in English was considered for inclusion. Retrieved studies were appraised for relevance and rigour using Joanna Briggs Institute appraisal tools.17

Related evidence summaries

JBI 18874 Pressure injuries: Preventing heel pressure injuries with positioning

JBI 18875 Pressure Injuries: Preventing heel pressure injuries with prophylactic dressings

JBI 18873 Pressure injuries: Preventing medical device related pressure injuries

Author(s)

Emily Haesler

Wound Healing and Management Node

References

- Cooper P, Gray D. Comparison of two skin care regimes for incontinence. Br J Nurs, 2001;10(6):S6-S20. (Level 1c evidence).

- Shannon RJ, Coombs M, Chakravarthy D. Reducing hospital-acquired pressure ulcers with a silicone-based dermal nourishing emollient-associated skincare regimen. Adv Skin Wound Care, 2009;22(10):461-7. (Level 2d evidence).

- Teerawattananon Y, Anothaisintawee T, Tantivess S, Wattanadilokkul U, Krajaisri P, Yotphumee S, Wongviseskarn J, Tonmukayakul U, Khampang R. Effectiveness of diapers among people with chronic incontinence in Thailand. Int J Technol Assess Health Care, 2015. 08 Dec;31(4):249-55. (Level 3e evidence).

- Su MY, Lin SQ, zhou YW, Liu SY, Lin A, Lin XR. A prospective, randomized, controlled study of a suspension positioning system used with elderly bedridden patients with neurogenic fecal incontinence. Ostomy Wound Manage, 2015. Jan;61(1):30-9. (Level 1c evidence).

- Duimel-Peeters I, Halfens R, Ambergen A, Houwing R, Berger P, Snoeckx L. The effectiveness of massage with and without dimethyl sulfoxide in preventing pressure ulcers: a randomized, double-blind cross-over trial in patients prone to pressure ulcers. Int J Nurs Stud, 2007;44(8):1285-95. (Level 1c evidence).

- Park KH, Kim KS. Effect of a structured skin care regimen on patients with fecal incontinence: A comparison cohort study. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 2014;41(2):161-7. (Level 2c evidence).

- Wounds Australia. Standards for Wound Prevention and Management 3rd ed. Osborne Park, WA: Cambridge Media; 2016.(Level 5c evidence).

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. Haesler E, editor. Osborne Park, Western Australia: Cambridge Media; 2014.(Level 1b and 5b evidence).

- Coleman S, Gorecki C, Nelson A, Closs SJ, Defloor T, Halfens R, Farrin A, Brown J, Schoonhoven L, Nixon J. Patient risk factors for pressure ulcer development: Systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud, 2013;50(7):974-1003. (Level 1b evidence).

- Verdú J, Soldevilla J. IPARZINE-SKR study: Randomized, double-blind clinical trial of a new topical product versus placebo to prevent pressure ulcers. Int Wound J, 2012;9(5):557-65. (Level 1c evidence).

- Lupianez-Perez I, Uttumchandani SK, Morilla-Herrera JC, Martin-Santos FJ, Fernandez-Gallego MC, Navarro-Moya FJ, Lupianez-Perez Y, Contreras-Fernandez E, Morales-Asencio JM. Topical olive oil is not inferior to hyperoxygenated fatty aids to prevent pressure ulcers in high-risk immobilised patients in home care. Results of a multicentre randomised triple-blind controlled non-inferiority trial. PLoS ONE, 2015. 17 Apr;10(4). (Level 1c evidence).

- Torra I Bou J, Segovia G, Verdu S, Nolasco B, Rueda L, Perejamo M. The effectiveness of a hyperoxygenated fatty acid compound in preventing pressure ulcers. J Wound Care, 2005;14(3):117-21. (Level 1c evidence).

- Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM, Bliss DZ, Colwell JC, Goldberg M, Kennedy-Evans KL, Logan S, Ratliff CR. Moisture-associated skin damage: Overview and pathophysiology. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2011. May-June;38(3):233-41. (Level 5b evidence).

- Pittman J, Beeson T, Terry C, Kessler W, Kirk L. Methods of bowel management in critical care. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2012;39(6):633-39. (Level 1c evidence).

- Bateman SD, Roberts S. Moisture lesions and associated pressure ulcers: Getting the dressing regimen right. Wounds UK, 2013;9(2):97-102. (Level 4c evidence).

- Australian Wound Management Association (AWMA). Pan Pacific Clinical Practice Guideline for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Injury. Osborne Park, WA: Cambridge Media; 2012.(Level 5b evidence).

- The Joanna Briggs Collabortion. Handbook for Evidence Transfer Centers – Version 4. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide. 2013.