Volume 26 Number 4

Evidence summary: Venous leg ulcers: leg care: elevation and skin hygiene

Emily Haesler

September 2018

Questions

What is the best available evidence on effectiveness of leg elevation for healing venous leg ulcers (VLUs)?

What is the best available evidence on effectiveness of skin hygiene for healing VLUs?

Summary

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) leads to blood pooling in the lower venous system that can also lead to oedema. Symptoms can be exacerbated by standing or sitting for long periods and can be relieved by wearing compression therapy.2 Elevation is thought to be a lifestyle strategy that could relieve oedema by promoting more effective capillary and lymphatic function and venous return thereby improving symptoms of venous disease and promoting VLU healing.3, 4

Regular skin hygiene promotes skin integrity by removing sources of dirt, irritation and infection. Maintaining skin hygiene is thought to reduce dryness, erythema and irritation. This reduces the risk of infection and new skin breakdown.5

Best practice recommendations

- Inform individuals with VLUs about their disease and implementing lifestyle interventions (Grade B).

- Practice leg elevation on a daily basis for a total of 60 minutes or longer in 2 to 3 sessions, if their daily routine allows (Grade B).

- Use a pH appropriate skin cleanser (Grade B).

- Moisturise the skin with a pH appropriate skin moisturizer (Grade B).

- Individuals with VLUs should record their self-care activities in a diary as a prompt to maintain adherence to practice (Grade B).

Background

Venous leg ulcers occur due to venous insufficiency. This describes a condition in which the venous system does not carry blood back to the heart in the most efficient manner, causing blood to pool in the veins of the lower limbs. Venous insufficiency occurs due to:1, 2

- previous blood clots,

- impaired valves in the veins in the lower leg do not close sufficiently after each muscle contraction, allowing blood to flow back to a previous section of the vein (venous reflux), and

- calf muscle pump function not adequately assisting in returning blood to the heart.

Evidence

Leg elevation

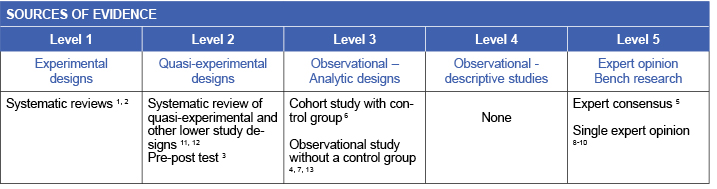

Evidence from small clinical trials conducted in people with venous disease with or without ulceration shows that microcirculation flow and lymphatic function can be improved and lower limb oedema can be reduced by elevating the legs.3, 4 In one trial3 (n=13), people with chronic VLUs elevated their legs at 10° continuously for 24 hours. Compared to baseline, changes in transcutaneous oxygen tension (TcPO2) and laser Doppler fluximetry indicated that individuals had significant improvements in microcirculation after the period of leg elevation. Additionally, significant reduction in lower limb volume and circumference was associated with leg elevation3 (Level 2). In another trial (n=30),6 people with CVI were shown to have significantly higher laser Doppler fluximetry when legs were elevated compared to lying without leg elevation (mean increase 45%, p<0.01) and blood cell velocity also significantly increased (mean increase 41%, p<0.01)6 (Level 3).

Only one study has explored the influence of elevation on VLU healing.4 Individuals with chronic VLUs engaged in elevation for a median of 352 minutes every 24 hours for six weeks. There was a significant reduction in median size of VLUs over time; however, there was no correlation between time spent elevating the legs and VLU healing (p=0.616)4 (Level 3). Thus, although there is some evidence for physiological improvements and relieve of venous symptoms,3, 4, 6 there is currently no evidence indicating this promotes more rapid VLU healing (Level 2 and 3).

One trial7 has investigated the effectiveness of leg elevation in preventing VLU recurrence when initiated by people with healed VLUs. People who experienced an ulcer recurrence were significantly less likely to have practiced leg elevation for at least one hour per day (23% versus 47% for individuals with no recurrence, p<0.005)7 (Level 3).

Although leg elevation is recommended as a component of best practice, there is insufficient evidence on the best regimen. In the trial that explored impact of elevation on VLU recurrence, people who engaged in leg elevation for at least 60 minutes per day had a lower recurrence rate than those who practiced less frequent or shorter duration of elevation7 (Level 3). Other advice includes:

- Elevate lower limbs to above the level of the heart to promote venous return, if the person has no musculoskeletal limitations.7-10 This is best achieved by lying on the bed9 (Level 5).

- Perform elevation for at least 60 minutes throughout the day7, 8 (Level 3).

- Perform elevation 3-4 times per day,10 or in the afternoon8 (Level 5).

- Protect the heels from pressure by floating the heels or using a heel protector legs are elevated9 (Level 5).

- Removing compression prior to elevating the legs (and reapplying compression after leg elevation) may increase the impact of elevation on venous return8, 11 (Level 5).

Skin cleansing and moisturising

There is no evidence indicating that cleansing and moisturizing the skin will promote VLU healing; however, applying a skin moisturizer after cleansing and gently drying the legs may relieve some venous symptoms by reducing irritation and dryness. Consensus opinion5, 8 provides guidance on general skin hygiene, suggesting that cleansing with a pH appropriate cleanser (from 4.0 to 7.0) is best practice in skin and wound care. A skin cleanser should be pH appropriate to avoid skin dryness and irritation that can occur with a higher pH soap.5 Application of a pH appropriate moisturizer is also recommended as best practice in skin and wound care5, 8 (Level 5).

Sustainability of elevation and hygiene interventions

Education interventions have been associated with improving adherence to leg elevation. A systematic review12 reported that people with VLUs who participated in a nurse-led behavioural education program raised their legs for longer durations than people who received no reinforcing education (Level 2). An Australian study13 also found that participation in an education program (a web-based learning package over six weeks) was associated with an initial increase in the practice of leg elevation, and some improvement in adherence to practice was sustained for up to 9 months (p=0.005)13 (Level 3). Both the systematic review12 and the study suggested that adherence may be higher when a daily diary is used to self-record performance of lifestyle interventions (Levels 2 and 3).

The same Australian study13 found similar increase in skin hygiene practices (applying a soap substitute and moisturiser) immediately after completing the six-week learning program. After 8-9 months, there was no significant increase in percent of participants still engaging in cleansing with soap substitute (p=0.642) or applying moisturiser (p=0.053). However, level of participation in these activities was over 60% at baseline13 (Level 3).

Methodology

The development of this evidence summary is based on the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology.14 A structured database search was employed using variations of the search terms describing VLUs and elevation and skin hygiene. Searches were conducted in EMBASE, Medline, AMED and the Cochrane Library for evidence from 1990 to May 2018 in English.

Author(s)

Haesler, E. for JBI Wound Healing & Management Node

References

- Palfreyman S, Nelson EA, Michaels JA. Dressings for venous leg ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 2007;335(7613):244-56. (Level 1).

- O’Meara S, Cullum N, Nelson EA, Dumville JC. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012(11). (Level 1).

- Barnes M, Mani R, Barret D, White J. Changes in skin microcirculation at periulcerous sites in patients with chronic venous ulcers during leg elevation. Phlebology, 1992;7:36-9. (Level 2).

- Dix F, Reilly B, David M, Simon D, Dowding E, Ivers L, Bhowmick A, McCollum C. Effect of leg elevation on healing, venous velocity and ambulatory venous pressure in venous ulceration. Phlebology, 2005;20(2): 87-94. (Level 3).

- Wounds Australia. Standards for Wound Prevention and Management 3rd ed. Osborne Park, WA: Cambridge Media; 2016.(Level 5).

- Abu-Own A, Scurr JH, Coleridge-Smith PD. Effect of leg elevation on the skin microcirculation in chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg, 1994;20:705-10. (Level 3).

- Finlayson K, Edwards H, Courtney M. Relationships between preventive activities, psychosocial factors and recurrence of venous leg ulcers: A prospective study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2011. October;67(10):2180-90. (Level 3).

- Brown A. Self-care strategies to prevent venous leg ulceration recurrence. Practice Nursing 2018;29(4):152-8. (Level 5).

- Anderson I. Treating patients with venous leg ulcers in the acute setting: part 1. Br J Nurs, 2017;26(12):S32-41. Level 5).

- Kelechi TJ, Johnson JJ. Guideline for the management of wounds in patients with lower-extremity venous disease: An executive summary. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 2012. November-December;39(6):598-606. (level 5).

- Heinen MM, van Achterberg T, op Reimer WS, van de Kerkhof PC, de Laat E. Venous leg ulcer patients: a review of the literature on lifestyle and pain-related interventions. J Clin Nurs, 2004;13(3):355-66. (Level 2).

- Van Hecke A, Grypdonck M, Defloor T. Interventions to enhance patient compliance with leg ulcer treatment: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs, 2008 17(1):29-39. (Level 2).

- Miller C, Kapp S, Donohue L. Sustaining behavior changes following a venous leg ulcer client

- The Joanna Briggs Collaboration. Handbook for Evidence Transfer Centers – Version 4. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide. 2013