Volume 27 Number 1

Compression bandaging: identification of factors contributing to non-concordance

Sharon L Boxall, Keryln Carville, Gavin D Leslie and Shirley J Jansen

Keywords venous leg ulcers, concordance, Chronic Venous Insufficiency, Compression bandaging, Venous disease

For referencing Boxall SL et al. Compression bandaging: Identification of factors contributing to non-concordance. WP&R Journal 2019; 27(1):6-20.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.27.1.6-20

Abstract

Aims To elucidate reasons for non-concordance with compression bandaging, subject the identified reasons to thematic analysis and use the resultant themes as the basis for the development of a screening tool to identify those patients at risk of non-concordance with compression bandaging.

Method A literature search was undertaken using the terms ‘concordance’, ‘compression bandaging’ and ‘venous leg ulcer’. Articles were included if they discussed reasons for non-concordance with compression bandaging. Forty-one articles were identified which met inclusion criteria. The full texts were read and the reasons for non-concordance tabulated. These were then subjected to thematic analysis.

Results Six themes emerged. These were termed knowledge deficit; resource deficit; psychosocial issues; pain/discomfort; physical limitations; and wound management. These themes were used to develop a screening tool to identify patients who exhibit barriers to concordance with compression bandaging.

Discussion Compression bandaging is the recommended treatment for venous leg ulceration1-3. However, the degree of concordance with compression bandaging therapy remains at sub-optimal levels4,5. Consequently patients experience protracted ulceration. The development of a risk screening tool for non-concordance will permit targeted intervention to address barriers to concordance before the patient has a poor experience of compression therapy.

Introduction

Compression bandaging remains the gold standard treatment for venous leg ulceration1,6-8; however, not all patients find it an achievable, acceptable therapy9,10. The adoption and tolerance of recommended levels of compression by patients has been described as compliance, adherence or concordance with treatment11. However, the degree of concordance with compression bandaging therapy is reported to be frequently at sub-optimal levels4,5.

The purpose of this review is to determine the reasons for patient non-concordance with compression bandaging and subject these reasons to thematic analysis.

Literature search

A literature search was undertaken using the terms ‘concordance’, ‘compression bandaging’ and ‘venous leg ulcer’, covering the period from 1995 to July 2016 and using the following tools and resources: PubMed, Medline, Internurse, CINAHL, ProQuest, Ovid and Wiley Online. This initial search identified 15 articles of high relevance. Only articles in English were included.

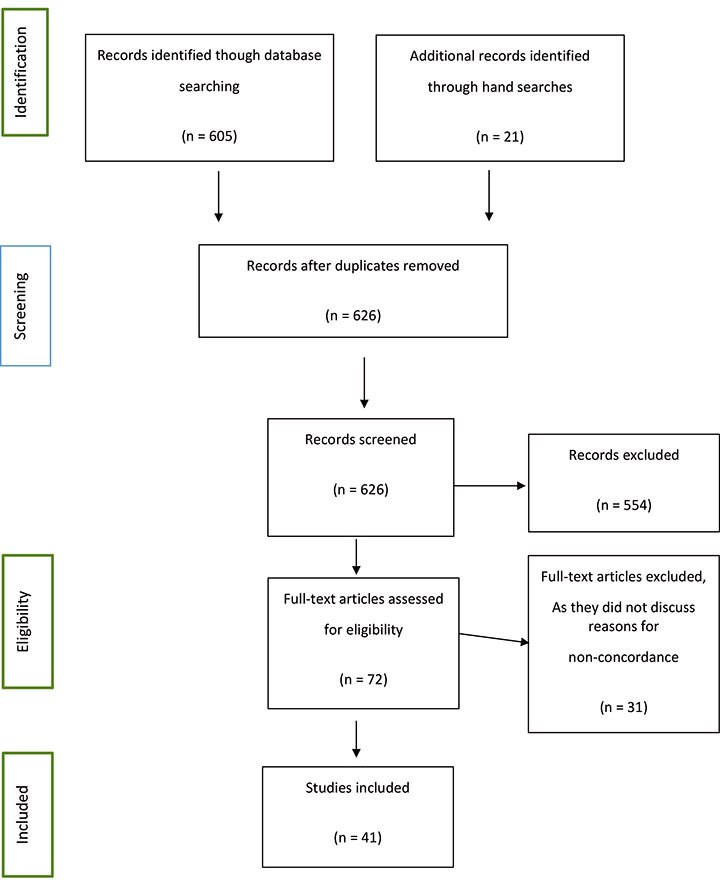

Given the relative paucity of literature recovered, it was decided to widen the search to include the Mark Allen Group (MAGOnline) database and Google Scholar, using search terms as described. These searches returned 232 (MAGOnline) and 358 (Google Scholar) results, respectively. The titles of these 605 articles were screened and the abstracts examined to determine if they contained information regarding reasons for non-concordance with compression bandaging. There were 554 papers excluded at this point.

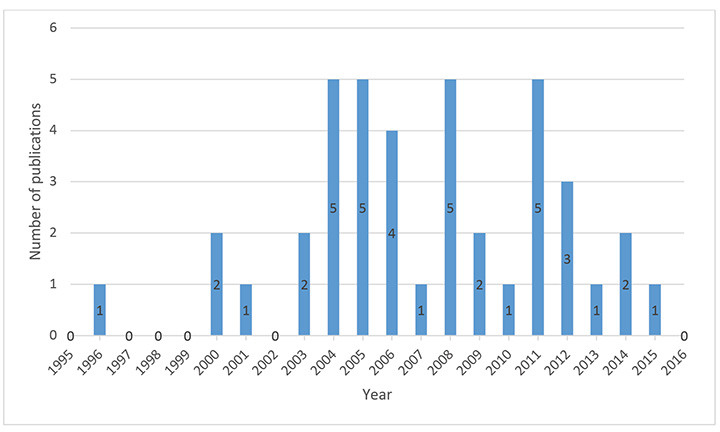

The reference lists of the initial 15 articles and 36 articles identified in the second search were then hand searched. A further 21 articles were recovered. The full texts of these 72 articles were screened and 31 articles excluded as they did not discuss reasons for non-concordance with compression bandaging. The remaining 41 articles were included in the review. A PRISMA diagram of this process is found in Figure 1 and a graphical representation of the years in which the studies were published is displayed as Figure 2.

Figure 1: Literature search

Figure 2: Year of publication of studies

Reasons for Non-concordance: The Evidence Base

Only four of the included studies report identification of reasons for non-concordance as a primary area of investigation12-15. Primary research where the focus was not specifically non-concordance and case studies including the use of compression therapy accounted for a further 17 articles. The remaining 24 studies reviewed the literature. The two most comprehensive reviews of the literature were those of van Hecke, Grypdonck and Defloor16 and Moffatt, Kommala, Dourdin and Choe8. Both were published in 2009.

Since then, the only primary research identified in the literature was that by Miller et al.17 and a case study by Yarwood-Ross and Haigh18. Miller et al.17 analysed the data obtained in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) which measured the effects of two different antimicrobial dressings beneath compression bandages and identified that larger ulcer size and shallower ulcer depth were negatively associated with compression concordance. Yarwood-Ross and Haigh18 were the first authors to mention that failure to consult with the patient about the treatment process reduced concordance. However, these authors cited a secondary source which was a 1995 study by Tonge19, which could not be located.

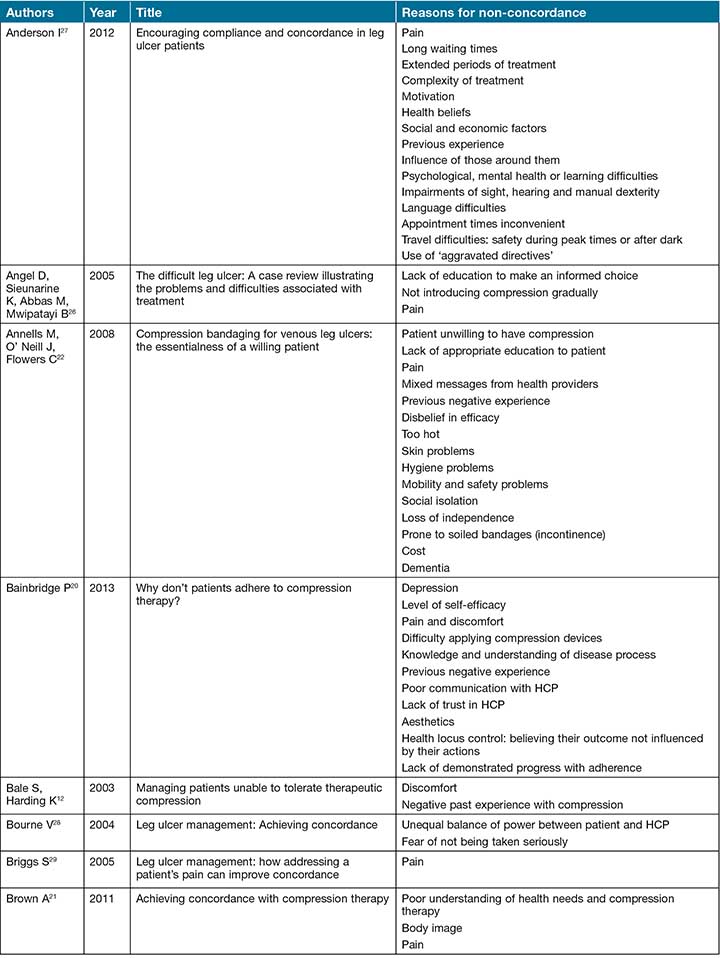

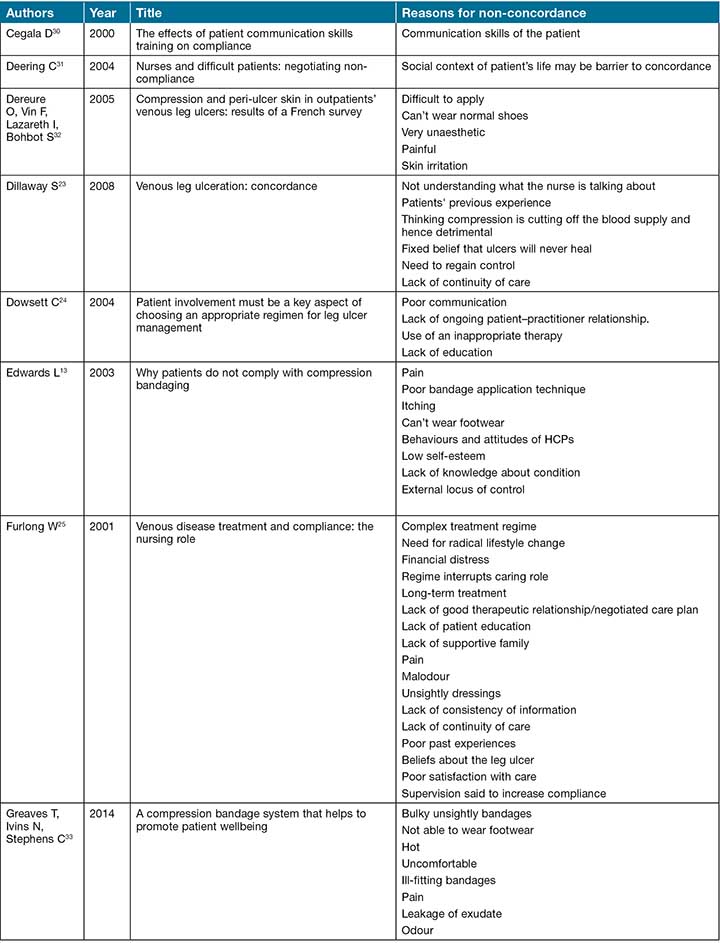

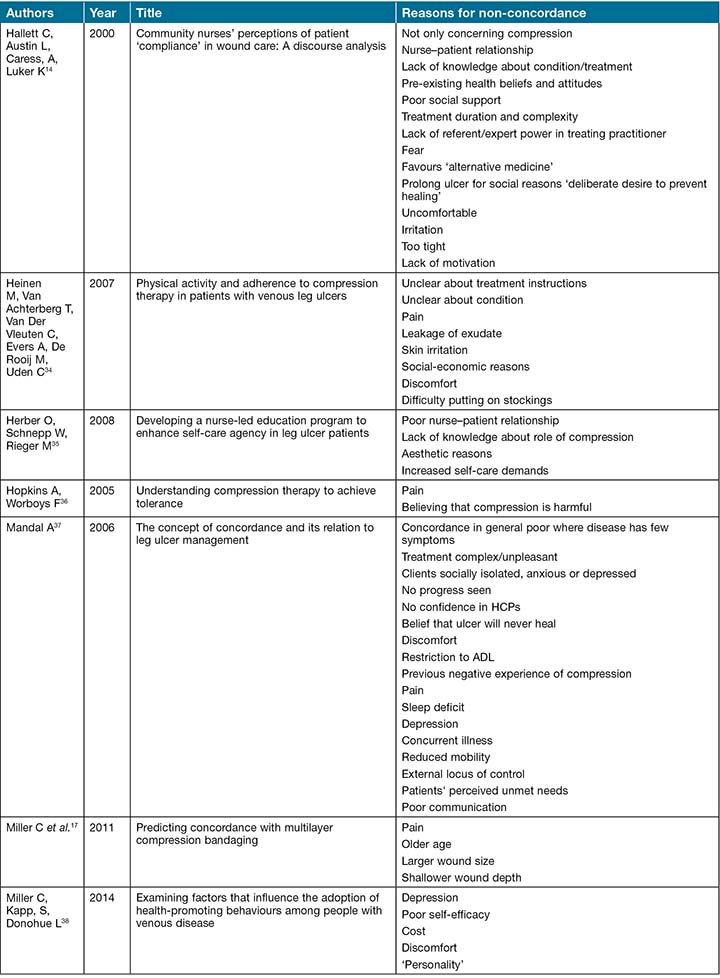

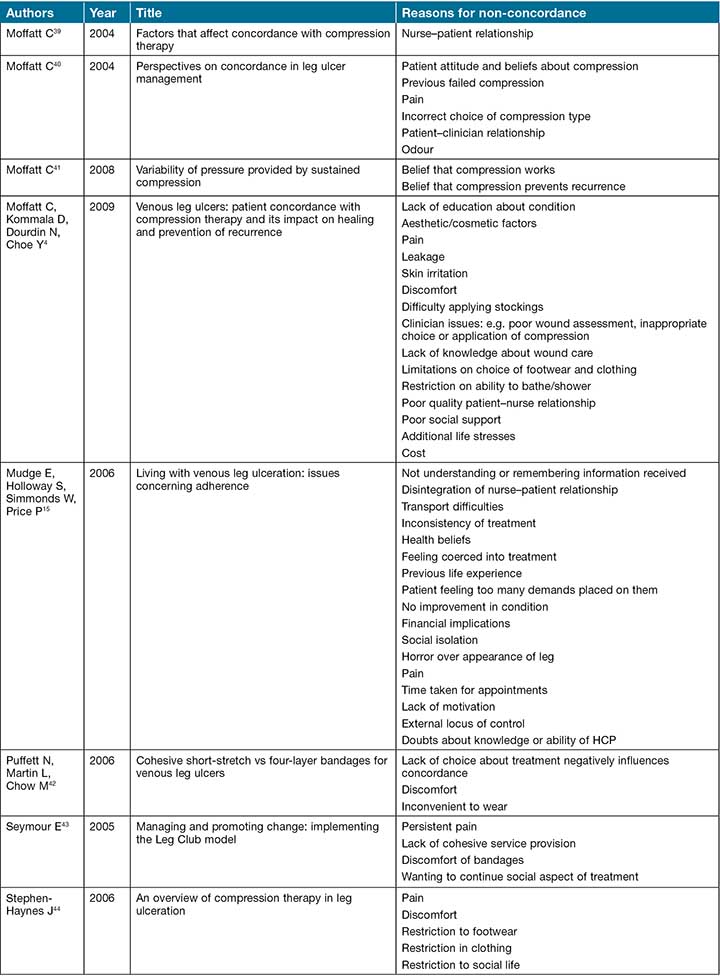

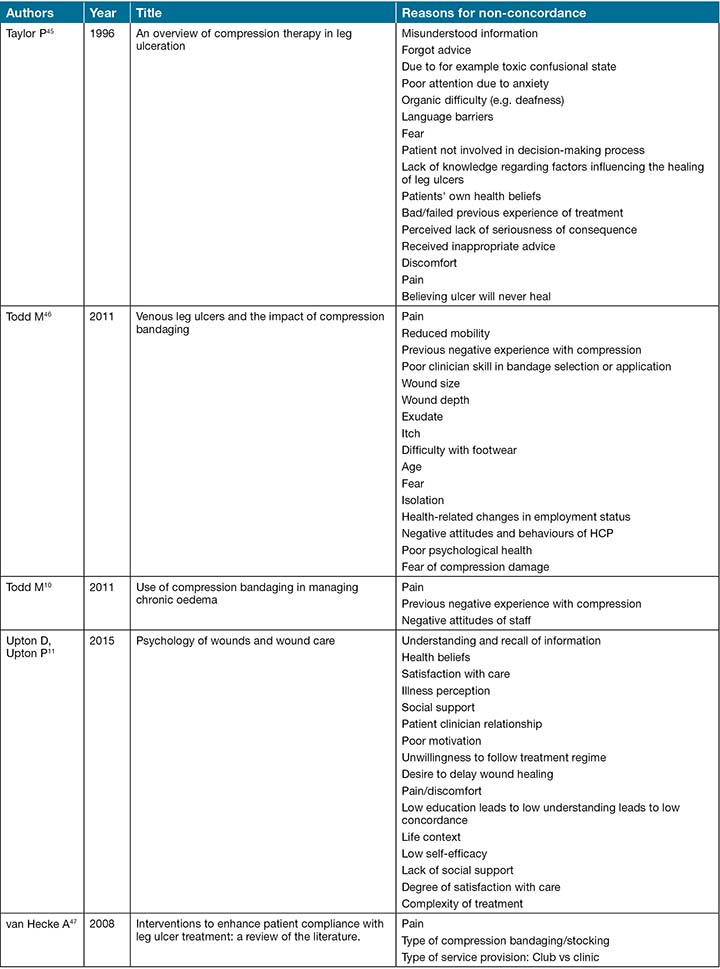

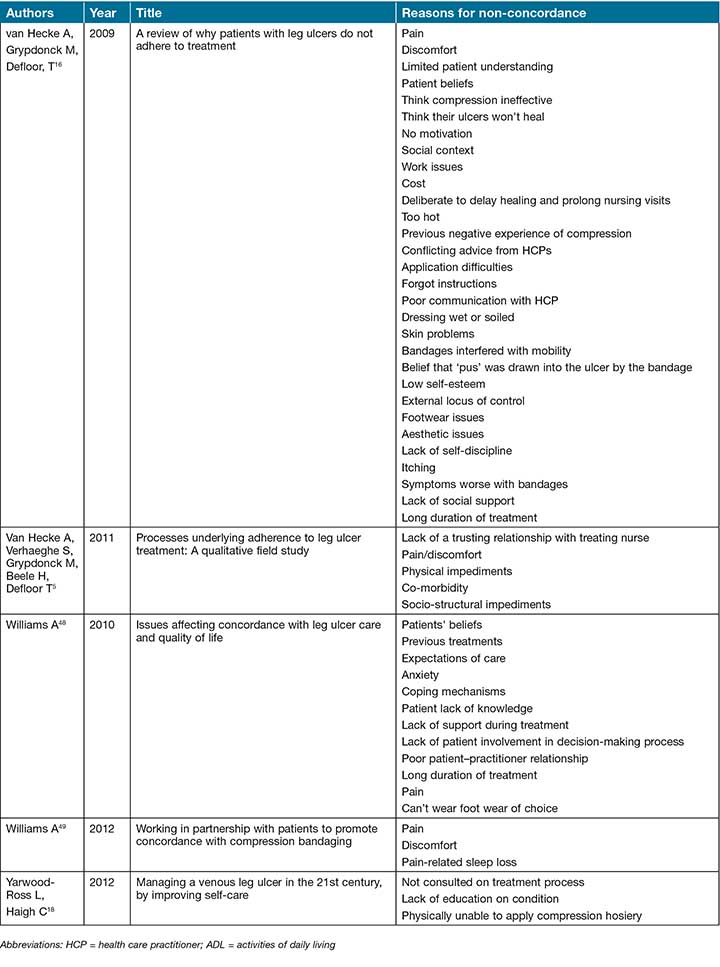

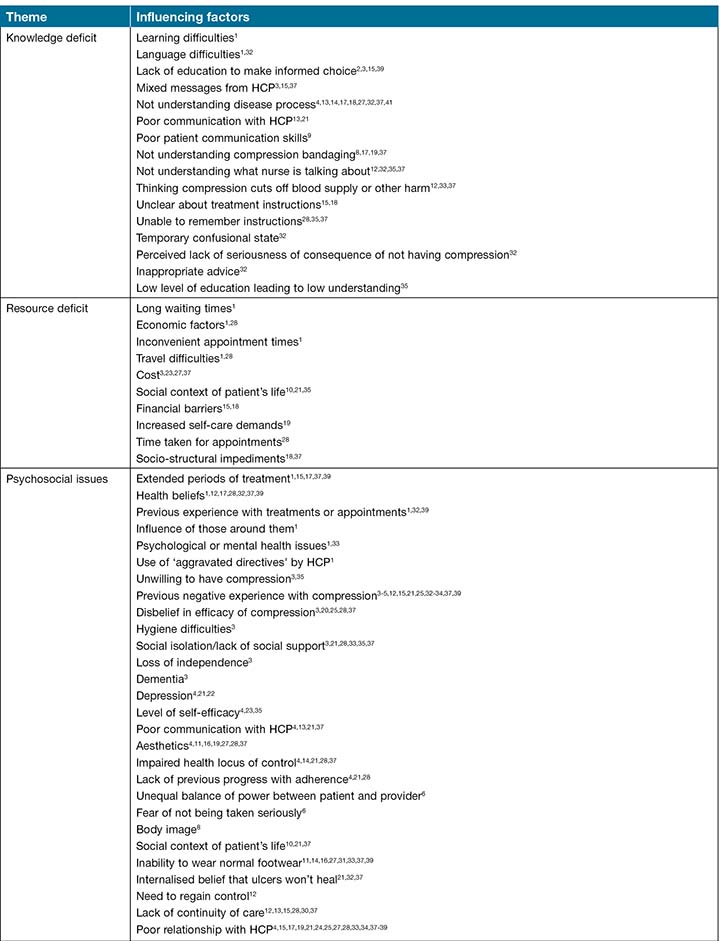

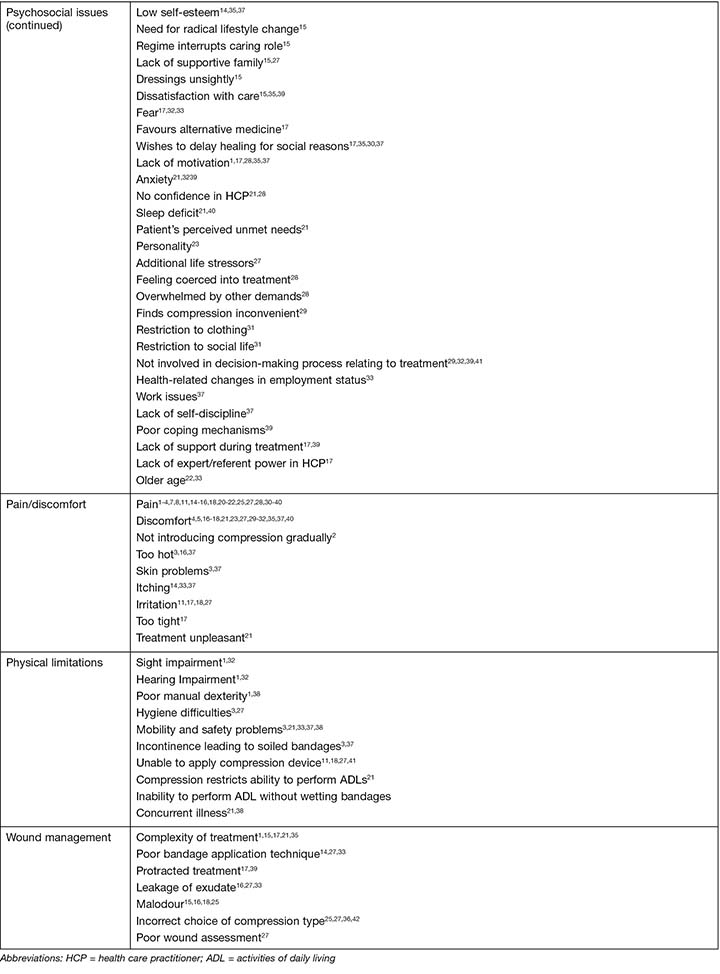

The full texts of all 41 articles were read and the reasons for non-concordance reported in each article tabulated. The list is extensive and a total of more than 300 recorded reasons were extracted from the literature, though there is considerable overlap between studies. This information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Reason for non-concordance with compression bandaging reported in the literature

Table 1 continued: Reason for non-concordance with compression bandaging reported in the literature

Table 1 continued: Reason for non-concordance with compression bandaging reported in the literature

Table 1 continued: Reason for non-concordance with compression bandaging reported in the literature

Table 1 continued: Reason for non-concordance with compression bandaging reported in the literature

Table 1 continued: Reason for non-concordance with compression bandaging reported in the literature

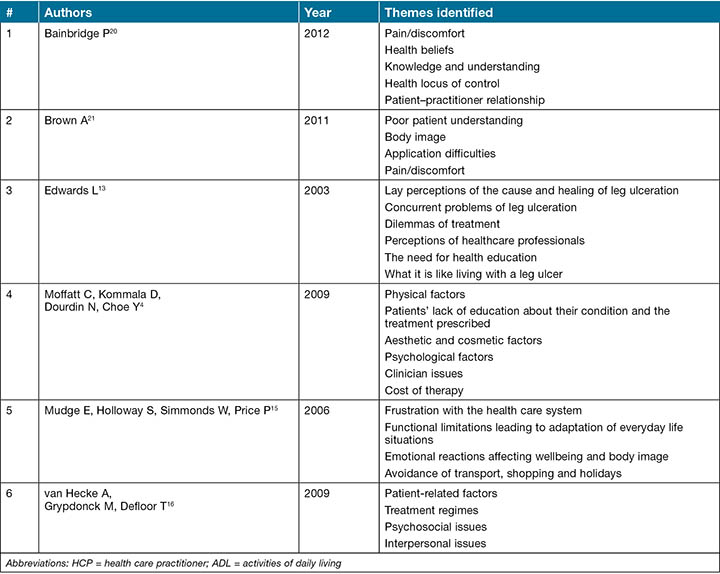

A number of authors undertook thematic analysis of their literature searches. These included Bainbridge20, Brown21, Edwards13, Moffatt, Kommala, Dourdin and Choe4, Mudge, Holloway, Simmonds and Price15 and van Hecke, Grypdonk and Defloor16.

Each of these authorship teams identified between four and six themes contributing to non-concordance with compression bandaging. There was considerable diversity in the themes identified and the four teams identified a total of 13 themes. Although the most obvious disincentive to concordance might be perceived to be pain, not all authors found this to be so, and pain was specifically itemised only by Bainbridge20 and Brown21, although Edwards13 discusses pain under the theme of concurrent problems of leg ulceration and Moffatt, Kommala, Dourdin and Choe4 included it under physical factors. Van Hecke, Grypdonk and Defloor16 noted that although patients frequently report pain as an important determinant of adherence to compression treatment, it was seldom the focus in the studies eligible for inclusion in their review. All authors identified a lack of patient knowledge regarding treatment as a contributing factor to non-concordance. The themes for non-concordance with compression bandaging identified by these authors are itemised in Table 2.

Table 2: Thematic analysis of compression bandaging non-concordance reported in the literature

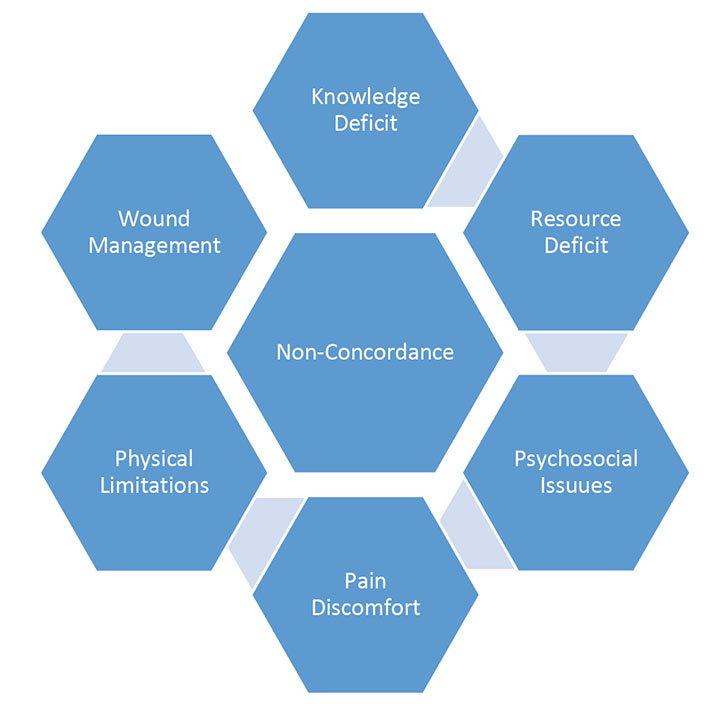

Following the tabulation of the numerous reported contributing factors to non-concordance with compression bandaging itemised in Table 1 and in response to the variety of themes extracted by the various authorship teams presented in Table 2, the authors undertook to conduct a comprehensive thematic analysis of the data. After initial familiarisation with the data, five themes were generated. These were termed knowledge deficit; resource deficit; psychosocial issues; pain/discomfort; and physical limitations. However, on final analysis it was decided to add a sixth theme in order to capture otherwise unclassified issues which related directly to wound management practices. In this way, it was possible to capture all the reasons identified in Table 1. These themes are illustrated in Figure 3. Each factor is then discussed.

Figure 3: Factors contributing to non-concordance with compression bandaging

Factors contributing to non-concordance with compression bandaging

Knowledge deficit

A failure to understand what treatment entails13,20-25, the rationale behind compression bandaging13,20,21,23,24,26, or the possible consequences of failing to adopt a recommended treatment13,20,21,24,26, were reasons cited for non-concordance with compression bandaging. Factors contributing to this knowledge deficit included learning and language difficulties27, temporary confusion45 and ongoing dementia22. Patients reported being unable to remember instructions and one author reported that a generalised low level of education could contribute to a low understanding of treatment requirements11.

With the exception of patients experiencing an organic confusional state, it is proposed that an informed health professional should be able to provide education and explanation in a manner applicable to the patient’s health literacy and cognition. This may involve the use of interpreters or written information in languages other than English. Tools exist to assist practitioners to design effective patient education material, such as the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool promoted by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2017)50.

The health professional needs first to identify what the patient needs to know, effectively communicate the information to the patient and ascertain that the information has been transferred and interpreted. The use of written educational material in layman’s terms and at an appropriate literacy level may assist in knowledge translation and retention51.

Effective methods of communicating health information include the use of written material52, demonstration and a variety of technological interventions such as audiovisual material and computer-based learning53. The use of culturally appropriate material geared to specific patient needs enhances the chance of a successful outcome51.

Resource deficit

The second theme concerned patients who experienced resource-related barriers to concordance. Both time and finances were implicated barriers and these were identified in regard to both the patient and the health service. Patient-related issues included absolute resource deficiency such as not being able to afford the cost of treatment4,16,22,25,34,38 or available safe transport options for treatment15,27. Conflicting demands on the patient’s time due to multiple medical appointments, demanding carer responsibilities25 or employment or familial restrictions may produce a relative resource deficit. Long waiting times27 or the inability of the health service to provide an appointment at a time that a patient can attend27 may be symptomatic of a lack of resources within the health care environment. A well-resourced health care provider may be able to partially alleviate the patient resource deficit through the provision of free or subsidised transport and treatment or provision of local or in-home care. Liaison with social services may be needed to assist the patient facing barriers related to the caring role.

Psychosocial Issues

By far the largest category of contributors to non-concordance related to psychosocial issues. An extensive list of reasons recovered from the literature described issues related to patients' health beliefs11,14,15,27,41,45, treatment-related distress11,14,16,37,41,45,48, mental health issues27,46, the social impact of leg ulcer treatment22,27,31,34,44,47 and the quality of interaction with the health care provider5,13-15,35,39.

Health-related beliefs such as not thinking of compression as an efficacious treatment16 or that the ulcer will never heal23,37,45 were poorly correlated with concordance as was holding an external locus of control with regard to health outcomes16. Patients described distress regarding the protracted nature of treatment25,27, sleep deprivation related to the ulcer37,49, fear46 and a loss of independence due to not being able to treat their own wound4,18,34. Some also expressed concerns about them being coerced into treatment15 and they had therefore not fully entered into a concordance arrangement regarding compression.

Social issues related to body image and impaired aesthetics as a result of them not being able to wear footwear and clothing of choice4,16,33,44,46, restrictions treatment placed on their social and employment activities22,44, the inability to perform personal hygiene activities as desired22 and consequent social isolation15,22,41 reduced their acceptability of compression bandages. Mental health issues, including depression20,38,41, anxiety41,45,48, poor self-efficacy20,38 and a lack of motivation11,14-16 also contributed to poor concordance.

A critical psychosocial impact on the patient was found to be the quality of the relationship with the health care provider. A lack of confidence in the provider’s ability37,41, lack of continuity of care15,23,24 and a history of a negative interaction with the practitioner contributed to a lack of concordance13,22,25,27,28,35,39.

Pain/discomfort

Of great importance to the patient, though reportedly poorly studied in the literature, is the impact of pain and other discomfort on concordance with compression bandaging4,5,10,11,13,15-17,20-22,25-27,29,32-34,36,37,39-41,43-49. Patients expressed not only pain but irritation, itch, unacceptable feelings of tightness or heat and concurrent skin problems13,16,22,46. Some of these symptoms may be alleviated by provision of suitable analgesics, a comprehensive skin care regime and the graduated introduction to compression therapy26. Lifestyle guidance to minimise exposure to extreme temperatures such as the use of home cooling and avoiding exertion during the heat of the day may also improve wellbeing and concordance.

Physical limitations

Patients detailed a variety of physical barriers to compression therapy, some of which may not be immediately obvious to the inexperienced practitioner. A patient with impaired sight or hearing not only faces difficulty understanding and accessing treatment but also in managing usual activities of daily living (ADL) with the added complication of compression bandaging27. Compression bandages need to be kept dry when bathing and this may necessitate the application of a protective waterproof bag to one or possibly both legs. Patients with sensory or mobility deficits face additional difficulties, not only applying the shower bags but they also increase risk of sustaining a fall54. Incontinent patients face the fear of, or actual, contamination of bandages22. Many people are reluctant to disclose issues regarding incontinence. An incontinent patient who has removed soiled bandages may be incorrectly considered to be ‘deliberately’ interfering with a dressing regime and be reluctant to disclose the real reason for bandage removal. Remediation of these barriers may necessitate the provision of assistance to perform ADL and the sensitive and appropriate management of any continence issues.

Wound management

Failure to provide evidence-based wound management was deemed a reason for non-concordance4. A wound assessment that fails to adequately diagnose peripheral arterial disease prior to the application of compression therapy not only increases the likelihood of intolerable pain, but potential ischaemic damage1. An inaccurate assessment of exudate level can contribute to dressing strikethrough and malodour, which may make compression therapy unacceptable25. Undiagnosed infection can be a cause of both increased pain and increased exudate, both adversely affecting the patient’s tolerance of compression therapy55. Poorly applied bandages, which become dislodged prior to the next planned dressing change, may create the impression of non-concordance56. Compression applied at an inappropriate high pressure may prove intolerable and studies show that the vast majority of practitioners fail to apply compression therapy at target pressure57,58.

Table 3 maps the identified themes to the listed influencing factors for non-concordance.

Table 3: Thematic classification of listed reasons for non-compliance.

Table 3 continued: Thematic classification of listed reasons for non-compliance.

Conclusion

Compression bandaging remains the gold standard for the treatment of venous leg ulceration as long as it is maintained at the correct pressure1,6-8. The analysis of the 41 texts provided a comprehensive list of factors found to contribute to non-concordance with compression bandages, and these were categorised into six thematic areas. These six themes offer insight into the reasons for non-concordance, namely knowledge deficit; resource deficit; psychosocial issues; pain/discomfort; physical limitations; and wound management issues. It was surprising that none of the included studies held the identification of reasons for non-concordance as their primary purpose, neither, to the best of our knowledge, has there been any attempt to develop a risk screening tool to identify patients at risk of non-concordance. The research team intends to address this anomaly and develop and test a screening tool to identify patients at risk of non-concordance with compression bandaging. The development of such a tool may prove a valuable precursor to the development of an intervention pathway to maximise wound healing of chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulcers.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge the funding support for Project Officer and PhD student Ms Sharon Boxall from the Wound Management CRC.

Disclosure of interests

Nil to report.

Author(s)

Sharon L Boxall*

RN, MN, PhD (c)

School of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedicine, Curtin University, Bentley, WA, Australia

Silver Chain Group, Osborne Park, WA, Australia

Email sboxall1967@gmail.com

Keryln Carville

RN, PhD

Professor Primary Health Care and Community Nursing Curtin University, Bentley, WA, Australia

Silver Chain Group, Osborne Park, WA, Australia

Gavin D Leslie

RN, PhD, BAppSc, Post Grad Dip (Clin Nurs), FACN

Professor Critical Care Nursing and Director Research Training, School of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedicine, Curtin University, Bentley, WA, Australia

Shirley J Jansen

MBChB, FRCS, PhD, FRACS

Dept Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, WA, Australia

Curtin Medical School, Curtin University, Bentley, WA, Australia

Heart and Vascular Research Institute, Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, Perth, WA, Australia

* Corresponding author

References

- Australian Wound Management Association Inc & New Zealand Wound Care Society. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guideline for prevention and management of venous leg ulcers. Osborne Park, W. Australia: Cambridge Publishing, 2011, p.132.

- Simon D, Dix F and McCollum C. Management of venous leg ulcers. British Medical Journal. 2004; 328: 1358-62.

- O’Meara S, Cullum N, Nelson E and Dumville J. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012; 2012.

- Moffatt, Kommala D, Dourdin N and Choe Y. Venous leg ulcers: patient concordance with compression therapy and its impact on healing and prevention of recurrence. International Wound Journal. 2009; 6: 386-93.

- Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S, Grypdonck M, Beele H and Defloor T. Processes underlying adherence to leg ulcer treatment: A qualitative field study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2011; 48: 145-55.

- Blair SD, Wright DD, Backhouse CM, Riddle E and McCollum CN. Sustained compression and healing of chronic venous ulcers. Br Med J. 1988; 297: 1159-61.

- Ratliff RC, Yates RS, McNichol RL and Gray RM. Compression for Primary Prevention, Treatment, and Prevention of Recurrence of Venous Leg Ulcers: An Evidence-and Consensus-Based Algorithm for Care Across the Continuum. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2016; 43: 347-64.

- Nicolaides AN, Allegra C, Bergan J, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs: Guidelines according to scientific evidence. International Angiology. 2008; 27: 1 - 59.

- Finlayson K, Edwards H and Courtney M. The impact of psychosocial factors on adherence to compression therapy to prevent recurrence of venous leg ulcers. Journal of clinical nursing. 2010; 19: 1289-97.

- Todd M. Use of compression bandaging in managing chronic oedema. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2011; 16: S4-S12.

- Upton D and Upton P. Psychology of Wounds and Wound Care. Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- Bale S and Harding KG. Managing patients unable to tolerate therapeutic compression. British Journal of Nursing. 2003; 12: S4-S13.

- Edwards L. Why patients do not comply with compression bandaging. British Journal of Nursing. 2003; 12: S5-S16.

- Hallett C, Austin L, Caress A and Luker K. Community nurses’ perceptions of patient ‘compliance’ in wound care: A discourse analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000; 32: 115.

- Mudge E, Holloway S, Simmonds W and Price P. Living with venous leg ulceration: issues concerning adherence. British Journal of Nursing. 2006; 15: 1166-71.

- Van Hecke A, Grypdonck M and Defloor T. A review of why patients with leg ulcers do not adhere to treatment. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009; 18: 337-49.

- Miller C, Kapp, Newall N, et al. Predicting concordance with multilayer compression bandaging. Journal of Wound Care. 2011; 20: 101-12.

- Yarwood-Ross L and Haigh C. Managing a venous leg ulcer in the 21st century, by improving self-care. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2012; 17: 460-5.

- Tonge H. A review of factors affecting compliance in patients with leg ulcers. J Wound Care. 1995; 4: 84-5.

- Bainbridge P. Why don’t patients adhere to compression therapy? British Journal of Community Nursing. 2013; 18: S35-S40.

- Brown A. Achieving concordance with compression therapy. Nursing and Residential Care. 2011; 13: 537-40.

- Annells M, O’ Neill J and Flowers C. Compression bandaging for venous leg ulcers: the essentialness of a willing patient. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008; 17: 350-9.

- Dillaway S. Venous leg ulceration: concordance. Journal of Community Nursing. 2008; 22: 22.

- Dowsett C. Patient involvement must be a key aspect of choosing an appropriate regimen for leg ulcer management. Journal of Wound Care. 2004; 13: 443-4.

- Furlong W. Venous disease treatment and compliance: the nursing role. British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing). 2001; 10: S18-S25.

- Angel D, Sieunarine K, Abbas M and Mwipatayi B. The difficult leg ulcer: A case review illustrating the problems and difficulties associated with treatment. Primary Intention: The Australian Journal of Wound Management. 2005; 13: 7.

- Anderson I. Encouraging compliance and concordance in leg ulcer patients. Wounds UK. 2012; 8: S6-S8.

- Bourne V. Leg ulcer management: Achieving concordance. Practice Nursing. 2004; 15: 286-9.

- Briggs S-L. Leg ulcer management: how addressing a patient’s pain can improve concordance. Professional Nurse. 2005; 20: 39-41.

- Cegala D. The effects of patient communication skills training on compliance - Comment. Arch Fam Med. 2000; 9: 64-.

- Deering C. Nurses and difficult patients: negotiating non-compliance. Journal of advanced nursing. 2004; 46: 110.

- Dereure O, Vin F, Lazareth I and Bohbot S. Compression and peri-ulcer skin in outpatients’ venous leg ulcers: results of a French survey. Journal of wound care. 2005; 14: 265.

- Greaves T, Ivins N and Stephens C. A compression bandage system that helps to promote patient wellbeing. Journal of Community Nursing. 2014; 28: 25-6,8-30.

- Heinen MM, Van Achterberg T, Van Der Vleuten C, Evers AWM, De Rooij MJM and Uden CJT. Physical activity and adherence to compression therapy in patients with venous leg ulcers. Archives of Dermatology. 2007; 143: 1283-8.

- Herber OR, Schnepp W and Rieger MA. Developing a nurse-led education program to enhance self-care agency in leg ulcer patients. Nursing science quarterly. 2008; 21: 150-5.

- Hopkins A and Worboys F. Understanding compression therapy to achieve tolerance. WOUNDS UK. 2005; 1: 26.

- Mandal A. The concept of concordance and its relation to leg ulcer management. Journal of Wound Care. 2006; 15: 339-41.

- Miller C, Kapp S and Donohue L. Examining factors that influence the adoption of health‐promoting behaviours among people with venous disease. International wound journal. 2014; 11: 138-46.

- Moffatt C. Factors that affect concordance with compression therapy. Journal of Wound Care. 2004; 13: 291-4.

- Moffatt C. Perspectives on concordance in leg ulcer management. Journal of Wound Care. 2004; 13: 243-8.

- Moffatt. Variability of pressure provided by sustained compression. International Wound Journal. 2008; 5: 259-65.

- Puffett N, Martin L and Chow MK. Cohesive short-stretch vs four-layer bandages for venous leg ulcers. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2006; 11: S6-S11.

- Seymour E. Managing and promoting change: implementing the Leg Club model. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2005; 10: S16-S24.

- Stephen-Haynes J. An overview of compression therapy in leg ulceration. Nursing standard. 2006; 20: 68-76.

- Taylor P. Assisting patients to comply with leg ulcer treatments. British Journal of Nursing. 1996; 5: 1355-60.

- Todd M. Venous leg ulcers and the impact of compression bandaging. British Journal of Nursing. 2011; 20: 1360-4.

- van Hecke A, Grypdonck M and Defloor T. Interventions to enhance patient compliance with leg ulcer treatment: a review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008; 17: 29-39.

- Williams A. Issues affecting concordance with leg ulcer care and quality of life. Nursing Standard (through 2013). 2010; 24: 51-2, 4, 6 passim.

- Williams A. Working in partnership with patients to promote concordance with compression bandaging. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2012; 17: S1-S16.

- Shoemaker S, Wolf M and Brach C. The patient education materials assessment tool (PEMAT) and User’s Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency For Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013.

- Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatton-Bauer J and Turnball G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: A systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. Journal of Cancer Education. 2011; 26: 12 - 21.

- Hoffmann T and Worrall L. Designing effective written health education materials: Considerations for health professionals. Disability & Rehabilitation, 2004, Vol26(19), p1166-1173. 2004; 26: 1166-73.

- Smith AJ and Zsohar AH. Patient-education tips for new nurses. Nursing. 2013; 43: 1-3.

- Corbett L, Kelly C and B M. Falls fisk associated with mulyi-layer compression wrap therapy in venous leg ulcers. 2007.

- Mudge E and Orsted H. Wound infection and pain management make easy. Wounds International. 2010; 1.

- Todd M. Venous disease and chronic oedema: treatment and patient concordance. British Journal of Nursing. 2014; 23: 466-70.

- Feben K. How effective is training in compression bandaging technique? British Journal of Community Nursing. 2003; 8: 80-4 5p.

- Taylor AD, Taylor RJ and Said SS. Using a bandage pressure monitor as an aid in improving bandaging skills. Journal of Wound Care. 1998; 7: 131-3.