Volume 27 Number 3

Evidence summary: Venous leg ulcers – pneumatic compression

Emily Haesler

For referencing Haesler E. Evidence summary: Venous leg ulcers – pneumatic compression. Wound Practice and Research 2019; 27(3):147-148.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.27.3.147-148

July 2018

Question

What is the best available evidence on effectiveness of pneumatic compression for healing venous leg ulcers (VLUs)?

Summary

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are ulcers that occur on the lower leg as a result of venous insufficiency. Compression therapy is recognised as gold standard treatment for promoting healing of VLUs1,2. The best available evidence indicates that pneumatic compression is effective in promoting VLU healing, when used as the only form of compression therapy2-5, or in conjunction with continuous compression from bandages or stockings6 (Level 1).

Best practice recommendations

When there are no contra-indications, use pneumatic compression therapy for achieving VLU healing (Grade A).

Note: Compression therapy carries a higher risk for individuals with peripheral arterial disease, peripheral neuropathy, heart failure or vasculitic ulcers, but may still be indicated5.

Background

Venous insufficiency describes a condition in which the venous system does not carry blood back to the heart in the most efficient manner, causing blood to pool in the veins of the lower limbs. Venous insufficiency occurs due to2,7:

- previous blood clots,

- impaired valves in the lower leg veins that do not close sufficiently after each muscle contraction, allowing blood to flow back to a previous section of the vein (venous reflux), and

- calf muscle pump function not adequately assisting in returning blood to the heart.

- Compression therapy works by generating external pressure on the superficial veins and tissues, thereby assisting in venous return. This helps to reduce peripheral oedema and induration, and to promote lower limb wound healing8. Compression systems usually utilise graduated pressure. Traditionally, higher pressure is attained at the ankles with pressure decreasing up the leg, although some contemporary systems use a negative pressure gradient9,10.

Pneumatic compression is compression applied by continuous, intermittent or sequential cycles of pressure applied by an air inflatable boot. The intermittent compression cycle, achieved with inflation and deflation of different air chambers in the boot, can be programmed to individualised cycles1,11. Unlike bandaging or stockings that are worn continuously, pneumatic compression is used intermittently, usually on a daily basis.

Evidence

Pneumatic compression compared with no compression therapy for healing VLUs

There is significant evidence that any compression therapy intervention is superior to no compression for healing VLUs. One trial reports specifically on pneumatic compression therapy compared to no compression therapy. The pneumatic compression regimen consisted of one hour sessions, five days per week for up to six months using sequential pressure of 50mmHg at the ankle and 40mmHg at the thigh. Significantly more VLUs healed when pneumatic compression was used (p=0.004) (risk ratio [RR] 2.27, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.30 to 3.97)6,12 (Level 1).

Pneumatic compression in conjunction with compression bandages or stockings

Pooling of results from three small RCTs favored the addition of pneumatic compression to a regimen of continuous compression bandaging or stockings. Significantly more VLUs healed with the addition of pneumatic compressions (risk ratio [RR] 1.31, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.63, p=0.013)6 (Level 1)

Overall, there is no strong evidence on whether pneumatic compression should be used alone or as an adjuvant with other types of compression therapy6 (Level 1).

Pneumatic compression compared with other compression therapy interventions

A RCT4 compared intermittent pneumatic compression with compression stockings and 2-layer short stretch bandaging (SSB). There was a significant difference based on treatment in VLU healing rates in individuals with superficial vein reflux, with both compression stockings (27% healed) and intermittent pneumatic compression (25% healed) demonstrated to be superior to SSBs (10%, p=0.01).Similar results were observed in individuals with deep reflux4 (Level 1).

Intermittent pneumatic compression has been shown to be more effective than 2-layer short stretch bandages (p=0.003) and Unna’s boot (p=0.03) in an RCT. A multi-chamber intermittent pneumatic compression system used once a day, five days per week for two months achieved significantly better reduction in VLU surface area, length, width and volume. There was no difference in efficacy between pneumatic compression and 4-layer bandaging or compression stockings3. These results were supported by another RCT that compared an intermittent pneumatic compression regimen that used both intermittent and sustained cycles to 4-layer bandaging. There were similar VLU healing rates after 12 weeks of therapy (31.6 vs 42.3%, p=0.30)13.

Comparison of different pneumatic compression regimens

One RCT reported a fast pneumatic cycle compared to a slow cycle. The fast cycle consisted of 60 seconds inflation, maintain peak pressure (45mmHg at the foot and 30 mmHg at the thigh) for 30 seconds, then 90 seconds deflation. Therapy was delivered for one hour each day. There was a significant difference for number of VLUs healed, favoring the fast cycle (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.79, p=0.0054)14 (Level 1).

Overall, there is no strong evidence for one regimen over another, and most reports provide no rationale for the regimen used in research studies6 (Level 1).

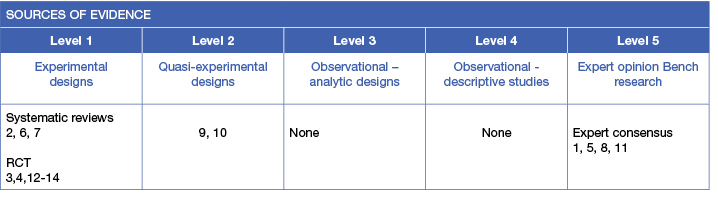

Methodology

The development of this evidence summary is based on the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology15. A structured database search was employed using variations of the search terms describing VLUs and pneumatic compression therapy. Searches were conducted in EMBASE, Medline, AMED and the Cochrane Library for evidence for 1900 to June 21018 in English.

Author(s)

Emily Haesler PhD, P Grad Dip Adv Nurs (Gerontics), BN

References

- Partsch H. Compression therapy: clinical and experimental evidence. Annals of Vascular Diseases, 2012;5(4):416-22. (Level 5).

- O’Meara S, Cullum N, Nelson EA, Dumville JC. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012(11). (Level 1).

- Dolibog P, Franek A, Taradaj J, Dolibog P, Blaszczak E, Polak A, Brzezinska-Wcislo L, Hrycek A, Urbanek T, Ziaja J, Kolanko M. A comparative clinical study on five types of compression therapy in patients with venous leg ulcers. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 2014. 14 Dec;11(1):34-43. (Level 1).

- Franek A, Taradaj J, Polak A, Dolibog P, Blaszczak E, Wcislo L, Hrycek A, Urbanek T, Ziaja J, Kolanko M. A randomized, controlled clinical pilot study comparing three types of compression therapy to treat venous leg ulcers in patients with superficial and/or segmental deep venous reflux. Ostomy Wound Management, 2013. August;59(8):22-30. (Level 1).

- Harding K, et al. Simplifying venous leg ulcer management. Consensus recommendations. www.woundsinternational.com. Wounds International., 2015. (Level 5).

- Nelson EA, Hillman A, Thomas K. Intermittent pneumatic compression for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014;5:CD001899. (Level 1).

- Palfreyman S, Nelson EA, Michaels JA. Dressings for venous leg ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 2007;335(7613):244-56. (Level 1).

- Wounds International. Principles of compression in venous disease: A practitioner’s guide to treatment and prevention of venous leg ulcers. 2013. (Level 5).

- Mosti G, Partsch H. Compression stockings with a negnm76RQ83zsative pressure gradient have a more pronounced effect on venous pumping function than graduated elastic compression stockings. European Journal of Vascular & Endovascular Surgery, 2011;42(2):261-6. (Level 2 ).

- Mosti G, Partsch H. High compression pressure over the calf is more effective than graduated compression in enhancing venous pump function. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, 2012. September;44(3):332-6. (Level 2 ).

- Dissemond J, Assenheimer B, Bultemann A, Gerber V, Gretener S, JKohler-von Siebenthal E, Koller S, Kroger K, Kurz P, Lauchli S, Munter C, Panfil E-M, Probdt S, Protz K, Riepe G, Strohal R, Traber J, Partsch H. Compression therapy in patients with venous leg ulcers. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, 2016;14(4):1072-87. (Level 5).

- Nikolovska S, Pavlova LJ, Petrova N, Gocev G. The efficacy of intermittent pneumatic compression in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Macedonia Medical Review 2002;5:56–9. (Level 1).

- Harding K, Vanscheidt W, Partsch H, Caprini J, Comerota A. Adaptive compression therapy for venous leg ulcers: a clinically effective, patient-centred approach. Int Wound J, 2016;13(3):317-24. (Level 1).

- Nikolovska S, Arsovski A, Damevska K, Gocev G, Pavlova L. Evaluation of two different intermittent pneumatic compression cycle settings in the healing of venous ulcers: a randomized trial. Medical Science Monitor, 2005;11:337–43. (Level 1).

- The Joanna Briggs Collaboration. Handbook for Evidence Transfer Centers – Version 4. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide. 2013