Volume 28 Number 1

Mental health drug and alcohol skin integrity champions as part of a district-wide model of care for wound prevention and management

Susan Monaro, Damon McKenzie, Kerrie Cunningham and Emma Underwood

Keywords model of care, skin integrity, champion, mental health, drug and alcohol

For referencing Monaro S et al. Mental health drug & alcohol skin integrity champions as part of a district-wide model of care for wound prevention and management. Wound Practice and Research 2020; 28(1):22-29.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.28.1.22-29

Abstract

Pressure injuries are a significant problem across the healthcare system. Historically, the focus of prevention programs has been in acute care settings, but skin vulnerability has been recognised in other settings, in particular where consumers are older and frail. In our health district, we sought to extend a model of care for wound prevention and management into the mental health and drug and alcohol (MHDA) services where many consumers are not necessarily in the older age group but are frail due to their mental and physical morbidities. The model was a district-wide program which relied on front line clinicians in each unit taking on the role of a ‘skin integrity champion’. Champions were recruited, inducted and supported to drive practice change in their units. The need for change was derived from an auditing framework developed specifically for measuring pressure injury prevention bundles of care in mental health and drug and alcohol settings. Baseline data demonstrated the need to improve pressure injury risk assessment and risk reduction. Additional strategies to support the model of care were refined by a focus group with the skin integrity champions which determined what the model needed to provide in these unique settings. Serial data demonstrated improvement in identifying consumers at risk and implementing pressure injury prevention strategies.

Introduction

It is recognised that people with mental illness experience reduced physical health and the onset of frailty at an earlier age when compared to the general population1. Many of the causes for this poor physical health are not well addressed by clinicians but, with modification, could potentially reduce the severity of frailty, and consequently morbidity and mortality. Minimum standards for care in Australian healthcare settings have been recognised through the National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards2. This has provided a framework to address both physical and mental health, and now includes actions related to health literacy, end-of-life care, care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and care for people with lived experience of mental illness or cognitive impairment.

Standard 5 of the NSQHS Standards is Comprehensive care; this addresses cross-cutting issues underlying many adverse events and aims to reduce the failure to: provide continuous and collaborative care; work in partnership with patients, carers and families to adequately identify, assess and manage patients’ clinical risks, and find out their preferences for care; and communicate and work as a team2.

Skin integrity has become a subject of increasing attention, particularly as people enter healthcare facilities. Initially, pressure injuries were the focus of this attention but, more recently, this has been broadened to include other types of skin injuries, including skin as part of the concept of frailty. Skin vulnerability is part of this concept3, encompassing a range of skin injuries including skin tears, moisture-associated skin injury and pressure injuries. In the vulnerable cohort of older people with mental health conditions, reducing harm from pressure injuries, falls, poor nutrition and malnutrition, cognitive impairment, unpredictable behaviours and restrictive practices are particularly relevant.

As such, programs to address physical health, including skin integrity, are receiving increasing attention in mental health settings. Clinicians in these settings are recognised as experts at managing mental health, with the evolution of advanced practice roles and champions4; however, whether physical health receives the level of care required in increasingly frail consumers likely needs further investigation. More recently, the need to expand practice to manage increasingly complex physical health problems has been identified and has resulted in the implementation of champions across a range of clinical issues in the mental health settings.

The evolution of skin integrity champions has been well described in a range of healthcare settings, including acute care5–9, rehabilitation10, aged care11,12, palliative care13 and primary care14. The difficulty in maintaining skin integrity in patients with mental health conditions is multifactorial, including the management of challenging behaviours. This has led to settings also creating skin integrity champions in mental health15. One study demonstrated that organisations who implemented unit-based skin integrity champions as part of a pressure injury prevention program reported a 40% to 50% decrease in hospital-acquired pressure injuries16.

Background

Our metropolitan Mental Health and Drug and Alcohol (MHDA) service provides services at all stages of the consumer experience, from health promotion, telephone triage and assessment to early intervention, inpatient – both acute and long stay – and community teams. Units are dispersed across a large geographical area, with inpatient units located at three campuses and community teams at a further four sites. Services are offered across the lifespan, from child and adolescent through adult and older people. The great diversity of services offered and the vastly differing needs of the consumers bring challenges in providing appropriate management. An increasing emphasis on the physical health needs of MHDA consumers required a redesign of how care is delivered and recognition of the need to build the capacity of the staff to meet this need.

For our service, there was difficulty in accessing specialist wound practitioners at the required frequency; therefore, alternative options to provide effective wound prevention and management were needed. In addition, the desire to minimise transfers to acute facilities or ambulatory care for the management of skin/wounds was important. Consumers should ideally remain in their usual environment wherever possible, as frequent transfers to new settings and clinicians may likely not be beneficial for holistic care.

MHDA units are managing increasingly complex skin dysfunction but this was not historically an area of high priority in mental health settings. Clinicians lack experience and/or exposure to skin as a management speciality and were reticent to address skin integrity due to perceived complexity. There was a need to increase the capacity of clinicians to make this an integral part of comprehensive care available to all consumers given the: ageing and frailty in MHDA settings; functionally aged consumers; use of psychotropic medications; high incidence of metabolic syndromes, vascular and chronic diseases; poor nutrition; potential for reduced movement and exercise (locked wards) and consequent difficulties with lifestyle modification and the impact that this has on health.

MHDA as a speciality has many subspecialties with different consumer profiles and presentations. These include age – ranging from child, youth, adult to the older person– high acuity, and varied diagnoses – psychosis, schizophrenia, eating disorders, depression, mania, suicidal ideation, substance use and neglect. The partnerships that MHDA has with other services are important, as consumers move between services across the care continuum. Examples include the pathway to community living teams who follow-up consumers in the home setting, residential aged care facilities (RACFs) in general, and the community health teams that provide variable levels of case management once consumers are discharged to either home or residential care facilities.

This paper aims to describe the implementation of skin integrity champions in the MHDA setting within a whole-of-district model to engage champions in all units within our service. Our health district is moving towards a model of care for wound prevention and management which spans the hospital–community continuum. All units and community nursing centres identified clinicians to be a clinical lead for skin integrity. Champions are inducted and have regular contact in a community of practice17, with the intention of a whole of hospital or service approach. They have been inducted in a large range of clinical settings. Trended data on all skin injuries, but in particular pressure injury incidence and severity from a state-wide Incident Information Management System (IIMS), identified the MHDA units which were at higher risk for skin injuries. Nurse unit managers of these high-risk units nominated a team member to become a mental health skin integrity champion. The skin integrity champions in mental health were part of the district-wide model of care which sought to prioritise wound prevention and management across the care continuum. To date, there have been limited publications relating to skin integrity champions in the mental health setting.

Aim

To identify, engage and support clinicians in a skin integrity champion role in high-risk units in a large MHDA service in the Sydney metropolitan area. The champions’ role was to improve pressure injury prevention and management practice, including reporting and documentation. Champions facilitated unit-based education and quality activities for skin integrity. Elements of the role included: auditing using a Bundle Measurement Method (BuMM); providing education consisting of facilitating online modules or organising face-to-face sessions in pressure injury risk assessment and management; and networking with key clinicians across the district for advice regarding consumer management where there was high complexity for skin integrity.

Implementation of the MHDA hub of the model

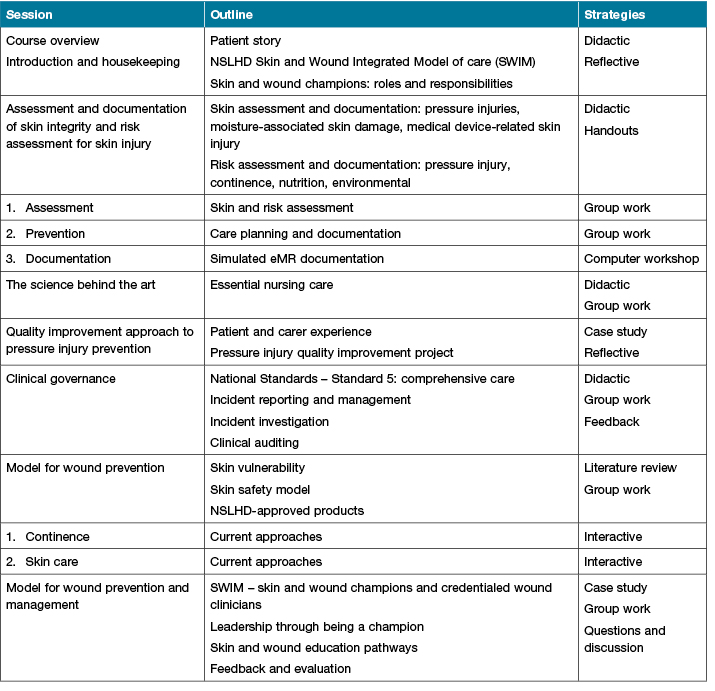

A document outlining the roles and responsibilities of MHDA skin integrity champions accompanied a guide developed as a reference for champions. Champions either volunteered or were nominated by their nurse unit manager. Champions were required to complete online learning modules in pressure injury prevention and management and attend a classroom activity specifically for MHDA. Champions also participated in a district-wide champion induction day which provided opportunities for ongoing networking with other champions across a range of specialities and settings. The program outline is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Skin integrity champions’ induction program

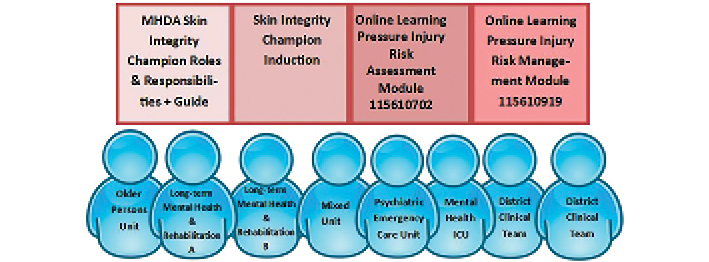

The role was monitored by the nurse unit managers and by the MHDA skin integrity committee. This is a health service level committee with representation from each mental health unit and a member from the mental health quality improvement unit, the management team and an advanced practice clinical nurse. Its role is to coordinate the skin integrity initiatives of the MHDA service and links up and down to the district committee to ensure across-district coordination. It meets second monthly to monitor consumer skin injuries and coordinate initiatives around skin integrity. The advanced practice nurse maintains a connection and supports the MHDA skin integrity champions. Outcomes included trended data on MHDA hospital-acquired pressure injury incidence and severity, audit results, and IIMS reports relating to all types of skin injury incidents. Figure 1 provides an overview of the MHDA clinical settings and the range of training offered at the induction of the MHDA skin integrity champions.

Figure 1. Overview of the MHDA clinical settings and the range of training offered at the induction of the MHDA skin integrity champions.

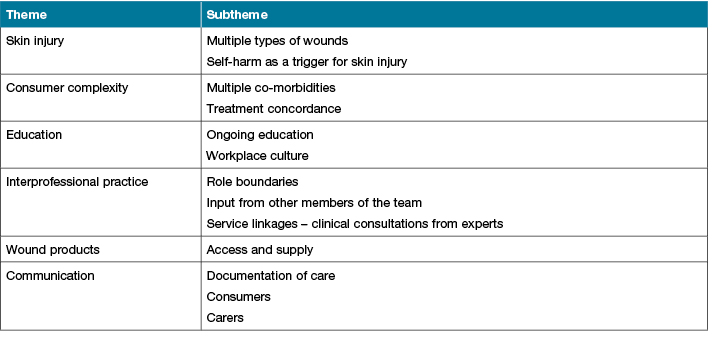

The MHDA skin integrity champions were followed up after induction via intermittent email communication and inclusion at events which focused on skin integrity such as Wound Awareness Week. An additional initiative to engage and retain MHDA skin integrity champions was a clinician focus group 1 year after induction to get feedback on issues impacting on their role. The focus group was guided by a number of broad, open-ended questions. Data were analysed by content analysis and findings are summarised in Table 2 under themes and subthemes.

Table 2. Summary of findings from the MHDA skin integrity champions gocus group

The qualitative data derived from the focus group confirmed that the MHDA skin integrity champions established that the induction program prepared them for their role. While the role initially was to focus on pressure injuries, the champions themselves have extended their role to champion other skin integrity issues, particularly those which result from self-harm. Becoming a champion resulted in networking with clinical experts in skin and wounds to assist them with care planning for consumers with more complex skin integrity problems. Case study 1 is a pre-implementation example of the delayed identification of a consumer with a deteriorating wound. The eventual consultation with the wound nurse relied on variable handovers of the wound plan. Case study 2 is a post-implementation case which demonstrates escalation and ongoing wound care modelling and monitoring by a MHDA skin integrity champion.

Case study 1: pre champion induction

James was a 63-year-old male with an extensive and complex history, resulting in unique care considerations. James had an enduring mental illness which was not responsive to treatment. He was first diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1977 and has had lengthy hospital admission, including a 29-year admission to a mental health facility, moving through several long-stay units. He had persecutory and bizarre delusions, auditory hallucinations and severe thought disorder.

James was mobile with the use of a four-wheel walker, although limited by lower back pain from degenerative disease, osteoarthritis in his right hip, and chronic pelvic pain due to injuries sustained jumping from a height. These injuries contributed to James being most comfortable in sitting, but with an unusual slanted posture. James required assistance with all his ADLs and used continence pads to manage faecal and urinary incontinence. James had a history of verbal and physical aggression, including assaulting staff.

James developed pressure injuries to his left hip and sacrum. These were managed by unit staff with various dressings but remained unhealed for some months and evolved to Stage 3 pressure injuries. James was identified as suitable for discharge to a RACF with mental health support. James wanted to make the move, as it would enhance his wellbeing returning to a more community-based setting. However, discharge was delayed as it was felt the RACF would not manage his pressure injuries.

The nurse unit manager arranged a review of James’ multiple pressure injuries by a wound specialist in the home nursing service also based on the campus. At the first visit, the pressure injuries were assessed and a wound plan developed. Education was provided to the consumer and the ward staff. Nursing staff involved in the care of James were able to observe wound care and provide continuity of care through the plan.

Wound care

- Cleansing: Normal saline

- Primary dressing: Microdacyn gel – three sprays to ensure entire wound bed was covered

- Secondary dressing: Island dressing (if daily) or if dressing is able to remain intact for more than 1 day, a silicone dressing can be used

Pressure redistribution

- High level of mobility but, if favours left side, a pressure redistribution mattress should be considered.

- Encourage right side lying or supine.

- Seating device for chair if fails to progress.

Nutrition care

- High protein diet 1.2g–1.5g/kg.

The wound specialist remained in regular contact, reviewing the pressure injuries and providing additional education as required. The pressure injuries subsequently healed and James transitioned to the RACF. After James had been there for 2 months he was asked how he felt, and he replied: “I want to stay here forever”. The unit has since identified and inducted a champion to proactively identify consumers at risk of pressure injuries and escalate injuries which are deteriorating. Capacity building is ongoing through liaison with the wound specialist.

Case study 2: post champion induction

Hugh was a 52-year-old male with a recently revised diagnosis of Diogenes. He had been scheduled under the Mental Health Act and admitted to an acute care mental health facility. He had intercurrent bilateral great toe diabetic foot ulcerations. He was abrasive and regularly verbally abusive. He was of tall stature and had very poor self-care which made him difficult to manage in an adult inpatient setting, hence he was referred to a Mental Health Intensive Care Unit (MHICU).

Multiple factors contributed to delayed wound healing, including poor diabetic control and diet, and low treatment concordance to offloading and hygiene. In particular, without nursing intervention, he would pace in wet socks for hours. Hugh had a management plan that focused on optimising self-care, control of diabetes, wound and pain management.

The MHICU skin integrity champion initiated and maintained liaison with the wound clinical nurse consultant and podiatrist to plan and implement wound care, provide education to other members of the mental health team, and manage behaviours that contributed to delaying wound healing. Much of the education occurred through modelling of good wound care skills, managing wound-related pain, and providing continuity and monitoring. His ulcerations made slow progress and after the 280 days of inpatient management, Hugh was discharged into the community with his previously severe and unhealable wounds progressing.

Wound care

- Dressings every 3 days with pre-procedure analgesia

- Cleansing: Normal saline

- Primary dressing: Pre-moistened nanocrystalline silver

- Secondary dressing: Foam

- Retention: Cloth tape “picture-framed”

- In the event of a Medical Adhesive Related Skin Injury (MARSI), review and assess barrier wipe or silicon tape

Foot care

- Not use courtyard when it is raining or grass is wet.

- Wear open-toed shoes. If refuses to wear, the use of the courtyard is forfeited.

- Change all wet items on his feet.

Diabetes care

- Pre-meal blood glucose level (BGL).

- Coffee to be given with 1x sweetener instead of 2x sugar.

- Ensure meals are appropriate for diabetic.

- Encourage consumption of full meal.

Discussion

Despite these initiatives, the retention of MHDA skin integrity champions has been less than expected due to staff movements, including transfers and resignations. An optional learning activity was offered to champions through enrolling in the Introductory Wound Dynamic Series face-to-face 2-day course to consolidate wound assessment, prevention and management.

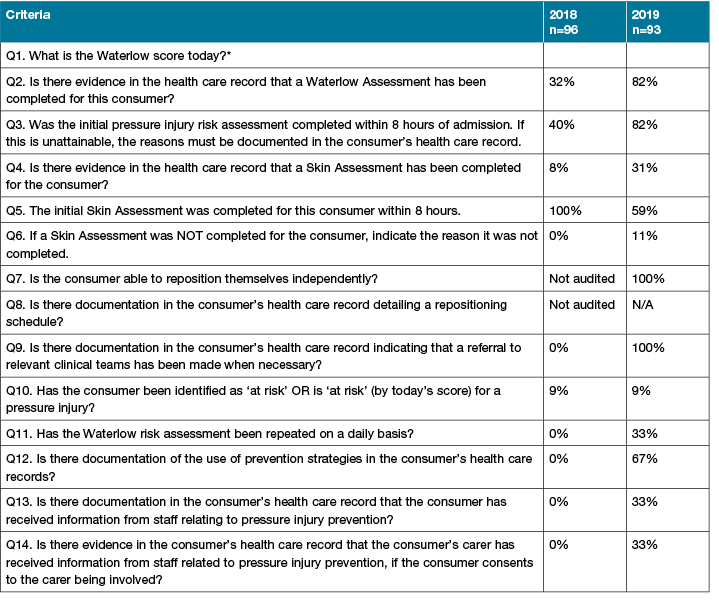

An additional activity that the champions participated in was an audit for pressure injury prevention in MHDA units. An audit tool specific to the MHDA setting was developed which addressed criteria for practice as per the national standards. The audit was piloted in 2017 by the lead MHDA clinical nurse. Subsequently, it was refined and posted on an intranet-based platform to enable the audits to be entered at the point-of-audit. The skin integrity champions were invited to participate by an email generated from the system and were mentored by the lead MHDA and clinical governance facilitator. Audit results for 2 years are contained in Table 3 and indicate incremental improvements across most variables measured.

The skin integrity champion in MHDA has facilitated a clinical network extending into a speciality area that has not previously had a large focus on physical health, in particular skin integrity. Feedback from participants in the induction program indicated a preparedness to take on the roles and responsibilities. The new model using skin integrity champions as the link between mental health and skin/wound clinicians has numerous benefits. These include the priority of skincare, notification of skin injury incidents, skin injury prevention as a component of physical care, access to resources for wound prevention and management, and engagement through skin/wound events.

Skin integrity as a MHDA clinical priority has led to an awareness of the need for skin assessment including the identification of skin injury. The accurate classification was disseminated by a skin integrity assessment poster which outlined wound types and pressure injury staging. This accurate classification led to improved pressure injury notification in the IIMS. Additionally, previously low completion of pressure injury incident notifications made accurate trending of pressure injuries difficult. A Pressure Injury eForm was placed in the MHDA forms folder; champions were able to encourage other MHDA clinicians to use this to document and trigger an incident notification. However, the IIMS notification process for pressure injuries was not intuitive; the champions addressed misreporting in incident management and were able to facilitate clinicians to report accurately and completely in the system, leading to better data capture.

The induction of MHDA skin integrity champions allowed them to access a range of important resources. These included expert wound clinicians for clinical consultation; education, both face-to-face and online; consumer and carer information for information on skin, skincare, dressings, continence; product lists to enable ease of ordering, and pressure redistribution equipment options for rental or purchase.

The champion role as part of the district-wide model provided an important link for front-line clinicians to the clinical governance unit for facilitating best practice in often difficult scenarios. The link increased the focus on skin integrity, mandating a multi-modal approach including consumer-centred skin care, continence, and nutrition. Skin integrity has important implications for body image, creating an additional impact on consumers’ mental health and quality of life.

The link to the clinical governance unit also meant that MHDA could participate in Wound Awareness Week activities at the unit level. Resources were provided, and the MHDA clinical leadership team developed some innovative approaches to engage consumers and clinicians in skin integrity. These included a card game based on Old Maid where the game aimed to pair cards with the strategies for pressure injury prevention, and an extended version for clinicians relating to identifying and staging pressure injuries. A second engagement exercise was the use of cakes to teach clinicians pressure injury classification and staging. Cakes were decorated to depict the various stages of tissue injury, enabling a graphic representation of pressure injury severity. In addition, the networking provided by such activities was an invaluable connection outside the MHDA service to other clinicians who were skin integrity champions in their units.

Table 3. Serial results for pressure injury prevention BuMM audits

Lastly, and importantly, skin integrity champions were engaged in auditing for pressure injury prevention practice which provided an opportunity to collect data and reflect on practice. The MHDA skin integrity champions were mentored in audit methodology to ensure the reliability of data and completing the quality improvement cycle. They could use the audit results to develop action plans with their unit to ensure engagement with management and frontline staff. These action plans included the following recommendations:

- Increase the rate of risk assessment tool completion on admission/readmission. Screening is a two-part process comprised of the risk assessment tool and a visual skin assessment. This should be completed within 8 hours of admission. If this is clinically contraindicated, the reason should be documented in the medical record.

- Increase the frequency of re-screening for consumers with a long length of stay.

- Promote greater awareness of how to complete both screens, particularly until the electronic medical record forcing function is implemented, to avoid incomplete documentation and no risk rating being generated.

- Include all of the consumers’ risk factors when completing the risk assessment tool to ensure an accurate risk assessment.

- Provide education regarding skin integrity to consumers at risk or with existing injuries, as well as their carers, and document that this has been provided.

Limitations

Staff turn-over, with loss of inducted skin integrity champions and the need for recruitment and recurrent induction, is one limitation. This will be addressed by the MHDA skin integrity committee supporting existing skin integrity champions. Where turn-over does occur, recruitment and induction will be implemented which will be facilitated by the MHDA management team and the district-level program respectively.

Conclusions

The district-wide skin integrity champion model enhances the integration of hospital-based care with community care, ensuring the transition across the continuum is seamless, and the consumer is holistically cared for in terms of both their mental and physical health. The inclusion of MHDA as part of the model ensures that the prevention and management of skin injuries in MHDA settings are consistent with the whole of district best practice.

The model needs to be sustained through ongoing evaluation and refinement to ensure that it meets the needs of consumers in the changing healthcare environment. The viability of the model will be achieved through succession planning for champions by ensuring that attrition will be addressed to maintain an across-service network of skin integrity champions.

The model will improve consumer outcomes by decreasing skin integrity incidents through better prevention and/or management if they do occur. Support for champions will increase clinician confidence, competence and, ultimately, role satisfaction. As the healthcare system continues to evolve, there will be a need for feedback to refine support as well as further education for champions to improve the clinician experience. We have also identified the need to involve family carers where possible to ensure the provision of holistic care which incorporates both the mental and physical health of consumers, Ministry of Health imperatives, and local service plans.

Ethics

This research project was approved by the ethics committee of the Northern Sydney Local Health District (NSLHD). The focus group with the MHDA skin integrity champions was conducted in accordance with the ethical approval. Focus group participants received the Participant Information Statement and consent was implied by attendance at the focus group.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Author(s)

Susan Monaro* RN, BAppSc (Nurs), MN, PhD

Skin Integrity Improvement Facilitator

Clinical Governance Unit, Northern Sydney Local Health District NSW, Australia

Email Suemonaro@optusnet.com.au

Damon McKenzie RN, BN

Clinical Nurse Specialist, Hornsby Hospital, NSW

Kerrie Cunningham

RPN, BSc (Nurs), MScMH, MSc (Nurs Prac)

Clinical Quality Manager

Northern Sydney Local Health District, NSW

Emma Underwood RN, BHS (Nurs), MN, MN (PS)

Clinical Nurse Consultant

Northern Sydney Local Health District, NSW

* Corresponding author

References

- Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Gray R, Hardy S, Lambert T, McAllister M, et al. A role for mental health nursing in the physical health care of consumers with severe mental illness. J Psychiatric Ment Health Nurs 2011;18(8):706–11.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. 2nd ed. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2017.

- Campbell J, Coyer F, Osborne S. The skin safety model: reconceptualizing skin vulnerability in older patients. J Nurs Scholarship 2016;48(1):14–22.

- Harris M, Rance S. Mental health champions: the need for specialists. Community Practitioner: J Community Practitioners’ Health Visitors’ Assoc 2016;89(6):22–4.

- Taggart E, McKenna L, Stoelting J, Kirkbride G, Mottar M. More than skin deep: developing a hospital-wide wound ostomy continence unit champion program. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;39(4):385–90.

- Amon BV, David AG, Do VH, Ellis DM, Portea D, Tran P, et al. Achieving 1,000 days with zero hospital-acquired pressure injuries on a medical-surgical telemetry unit. MEDSURG Nurs 2019 Jan/Feb;28(1):17–21.

- Choudry UH, Murphy MM. Implementation of a successful pressure ulcer prevention (PUP) program in a tertiary care hospital. J Am Coll Surg 2014;1:e34.

- Rogers C. Improving processes to capture present-on-admission pressure ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care 2013;26(12):566-72;quiz 73–4.

- Kelleher AD, Moorer A, Makic MF. Peer-to-peer nursing rounds and hospital-acquired pressure ulcer prevalence in a surgical intensive care unit: a quality improvement project. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;39(2):152–7.

- Lin L, Wade C. Comprehensive prevention and management of pressure ulcers in an acute inpatient rehabilitation facility: an evidence ebased assessment. PM R 2016;8(9Supplement):S182-S3.

- Edwards HE, Chang AM, Gibb M, Finlayson KJ, Parker C, O’Reilly M, et al. Reduced prevalence and severity of wounds following implementation of the champions for skin integrity model to facilitate uptake of evidence-based practice in aged care. J Clin Nurs 2017;26(23–24):4276-85.

- Price K, Kennedy KJ, Rando TL, Dyer AR, Boylan J. Education and process change to improve skin health in a residential aged care facility. Int Wound J 2017;14(6):1140–7.

- Evans P. Reflections from a hospice: how to involve carers in skin management. Wounds UK 2015;11(3):22–3.

- Parker CN, Shuter P, Maresco-Pennisi D, Sargent J, Collins L, Edwards HE, et al. Implementation of the champions for skin integrity model to improve leg and foot ulcer care in the primary healthcare setting. J Clin Nurs 2019;28(13–14):2517-25.

- Carson D, Emmons K, Falone W, Preston A. Development of pressure ulcer program across a university health system. J Nurs Care Quality 2012 Jan/Mar;27(1):20–7.

- Bergquist-Beringer S, Derganc K, Dunton N. Embracing the use of skin champions. Nurs Manage 2009;40(1):19–24.

- Wenger E. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.