Volume 28 Number 4

WHAM Evidence Summary: Polyhexamethylene biguanide for chronic wounds

Wound Healing and Management Unit, Curtin University (WHAM@Curtin)

For referencing Wound Healing and Management Unit. Evidence Summary: Polyhexamethylene biguanide for chronic wounds. Wound Practice and Research 2020; 28(4):189-191

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.28.4.189-191

Clinical question

What is the best available evidence for using polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) to reduce infection and promote healing in chronic wounds in all populations?

Summary

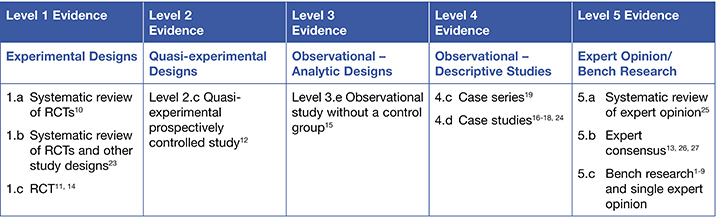

Polyhexamethylene biguanide is an antiseptic available as solution, gel or impregnated in wound dressings. Level 51-9 bench research indicates that PHMB products have broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against gram positive and negative bacteria (including biofilms), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), fungus and viruses. Level 110, 11 and Level 212 evidence reports mixed findings on the effectiveness of PHMB in delivering significant reduction in bacterial load in chronic wounds, with some studies reporting superiority compared to control cleansers and others finding no statistically significant differences. However, this evidence is generally of low quality. Level 513 expert opinion supports the use of PHMB in combination with debridement for managing infection, particularly biofilm. Level 1,10, 14 Level 315 and Level 416-19 evidence indicates PHMB is associated with improvements in wound healing outcomes, 10, 15-18 reduction in wound pain10, 14 and management of wound odour.14, 19

Clinical practice recommendations

Polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) can be used to reduce local infection and promote healing in chronic wounds (Grade B).

Sources of evidence

This summary was conducted using methods published by the Joanna Briggs Institute.20-22 The summary is based on a literature search combining search terms related to PHMB and wounds. Only studies that reported on the use of PHMB for a chronic wound were included in the clinical evidence summary. Searches were conducted in CINAHL, Medline, the Cochrane Library and Google Scholar for evidence published up to December 2019 in English.

Background

Polyhexamethylene biguanide is a an antiseptic, that has a chemical structure similar to naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides (AMPs).26, 27 A systematic review (SR) 1 of bench research included nine in vitro studies that reported on the antibacterial qualities of PHMB. This review found PHMB is effective in reducing non-specified strains of biofilm, with an average performance superior to silver but inferior to iodine1 (Level 5). Additional studies have demonstrated that PHMB-impregnated wound dressings and PHMB solutions are effective against gram positive and gram negative bacteria (including MRSA), fungus and viruses in laboratory settings2-5, 8 (Level 5). Effect against confirmed biofilm has also been demonstrated in vitro6 (Level 5).

Clinical evidence

Reduction in local infection

- In a SR10 that included six (primarily low quality) randomised controlled trials (RCTs),28-33 treatment of chronic wounds with PHMB dressings was associated with more substantial reduction in bacterial count (two studies), reduction in types of bacteria in the wound (two studies) and reduction in specific strains of bacteria (two studies), including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter cloacae and Staphylococcus aureus.10 The comparators included non-antimicrobial gauze, sponge and foam dressings, polihexadine impregnated cotton swab and a silver dressing10 (Level 1).

- In an RCT conducted in venous leg ulcers (VLUs, n= 27 analysed) that had biofilm presence confirmed by microscopy, cleansing with a PHMB-iodine solution statistically significantly reduced overall bacterial count compared to baseline, but this was not significantly different from saline cleansing (p > 0.05). There was a statistically significantly greater reduction in bacterial count in relation to wound size in the PHMB-iodine group (p = 0.07)11 (Level 1).

- In chronic wounds with clinical signs of local infection (n = 31), one group received 0.5% PHMB for cleansing and as a gauze-soaked dressing, and a comparator group received the same regimen using Ringer’s solution. After daily treatment for three weeks, there was no statistically significant between-group difference in percent of wound tissue cultures that were negative (47.4% PHMB versus 52.6% Ringer’s solution, p=0.886). However, individuals receiving the PHMB regimen had statistically significant superior reductions in C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell count (WBC)12 (Level 2).

Improvement in wound healing outcomes

- In a SR10 that included six RCTs,28-33 treatment of chronic wounds with PHMB dressings was superior to comparator for complete wound healing in only one study. One of the RCTs also noted PHMB to be associated with improved granulation.10 Comparators are reported above (Level 1).

- In chronic wounds with clinical signs of local infection (n = 31), treatment with 0.5% PHMB solution daily for three weeks showed no statistically significant between-group difference in percent of wounds reaching full closure compared with Ringer’s solution (66.7% PHMB versus 43.8% Ringer’s solution, p=0.181)12 (Level 2).

- In non-healing wounds (n=16), treatment with a biocellulose dressing impregnated with 0.3% PHMB solution for 2-3 weeks (length determined by visual condition of the wound) was associated with improved condition. At 24 weeks, granulation tissue had significantly increased (38.2 ± 34.6% versus 77.4 ± 36.0%, p < 0.04), slough had significantly decreased, and 75% of wounds had completely healed15 (Level 3).

- Improved wound healing with PHMB products has been reported in case studies. Case studies reporting use of 0.5% PHMB impregnated dressings demonstrated decrease in wound size for VLUs (n = 5) treated for up to seven weeks,16 complete wound healing within six weeks for diabetic ulcers (n = 5)34 and reduction in wound size for lower leg ulcers (n = 5) treated for three weeks.17 Improvements were also reported for lower leg ulcers receiving (n = 4) receiving PHMB solution in combination with ultrasonic debridement.18 ( all Level 4).

Considerations for use

The following points could be considered when using PHMB:

- A PHMB topical solution alone is unlikely to eradicate biofilm in a chronic wound.7 Although bench research has established the effectiveness of PHMB in vitro,6 it has been demonstrated that in vitro biofilm modelling fails to account for clinical realities (e.g. time the solution spends in contact with the skin).7 Combining topical antimicrobials with debridement is recommended for biofilm management in chronic wounds13 (Level 5) and has been demonstrated in a small case series combining use of topical PHMB with ultrasonic debridement18 (Level 4).

- A PHMB product might help manage wound pain. In a SR,10 treatment with PHMB dressings was associated with statistically significantly greater reductions in patient-reported pain (two studies), compared with a non-antimicrobial foam and a silver dressing10 (Level 1). However, an additional RCT (n = 24) found the pain reduction associated with 0.2% PHMB solution was not significantly different from that achieved with 0.8% metronidazole solution14 (Level 1).

- A PHMB solution might reduce wound odour. An RCT (n = 24) found that wound odour statistically significantly reduced after four days of treatment with 0.2% PHMB solution. This was not significantly different from 0.8% metronidazole solution14 (Level 1). A case series conducted in wounds with clinical signs of local infection (n = 25) also reported reduction in odour in 100% of wounds treated with 0.5% PHMB solution19 (Level 4).

- Three of the RCTs,28, 30, 32 included in a SR,10 reported no adverse effects associated with PHMB (Level 1). A safety review concurred that studies have reported minor or no adverse events; however, the review noted the lack of good quality, sufficiently large trials23 (Level 1). Caution has been recommended for use in wounds with exposed bone and cartilage due to PHMB’s cytotoxicity on cartilage and suppression of PHMB action by joint/nasal cavity fluid9, 25 (Level 5).

Author(s)

Wound Healing and Management Unit

Curtin University (WHAM@Curtin)

References

- Schwarzer S, James GA, Goeres D, Bjarnsholt T, Vickery K, Percival SL, Stoodley P, Schultz G, Jensen SO, Malone M. The efficacy of topical agents used in wounds for managing chronic biofilm infections: A systematic review. J Infect, 2020.

- Kirker K, Fisher S, James G, McGhee D, Shah C. Efficacy of a ployhexamethylene biguanide-containing antimicrobial foam dressing against MRSA relative to standard foam dressing. Wounds Int, 2009;21(9):229-33.

- Hirsch T, Limoochi-Deli S, Lahmer A, Jacobsen F, Goertz O Steinau H-U, Seipp H-M, Streinstrasser L. Antimicrobial activity of clinical used antiseptics and wound irrigating agents in combination with wound dressings. Plastic Repr Surg, 2011;127(4):1539-45.

- Hübner N-O, Matthes R, Koban I, Rändler C, Müller G, Bender C, Kindel E, Kocher T, Kramer A. Efficacy of chlorhexidine, polihexanide and tissue-tolerable plasma against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms grown on polystyrene and silicone materials. Skin Pharmacol Physiol, 2010;23(suppl 1):28-34.

- Rippon MG, Rogers AA, Sellars L, Styles KM, Westgate S. Effectiveness of a non-medicated wound dressing on attached and biofilm encased bacteria: Laboratory and clinical evidence. J Wound Care, 2018. 03 02;27(3):146-55.

- Machuca J, Lopez-Rojas R, Fernandez-Cuenca F, Pascual A. Comparative activity of a polyhexanide-betaine solution against biofilms produced by multidrug-resistant bacteria belonging to high-risk clones. J Hosp Infect, 2019. Sep;103(1):e92-e6.

- Johani K, Malone M, Jensen SO, Dickson HG, Gosbell IB, Hu H, Yang Q, Schultz G, Vickery K. Evaluation of short exposure times of antimicrobial wound solutions against microbial biofilms: From in vitro to in vivo. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2018;73(2):494-502.

- Lopez-Rojas R, Fernandez-Cuenca F, Serrano-Rocha L, Pascual A. In vitro activity of a polyhexanide-betaine solution against high-risk clones of multidrug-resistant nosocomial pathogens. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin, 2017;35(1):12-9.

- Fabry W, Reimer C, Azem T, Aepinus C, Kock HJ, Vahlensieck W. Activity of the antiseptic polyhexanide against meticillin-susceptible and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2013. Dec;1(4):195-9.

- To E, Dyck R, Gerber S, Kadavil S, Woo K. The effectiveness of topical polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) agents for the treatment of chronic wounds: A systematic review. Surg Technol Int, 2016;29:45-51.

- Borges EL, Frison SS, Honorato-Sampaio K, Guedes ACM, Lima V, Oliveira OMM, Ferraz AF, Tyrone AC. Effect of polyhexamethylene biguanide solution on bacterial load and biofilm in venous leg ulcers: A randomized controlled trial. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2018;45(5):425-31.

- Ceviker K, Canikoglu M, Tatlioglu S, Bagdatli Y. Reducing the pathogen burden and promoting healing with polyhexanide in non-healing wounds: a prospective study. J Wound Care, 2015. Dec;24(12):582-6.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline. Emily Haesler (ed). EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA; 2019.

- Villela-Castro DL, Santos V, Woo K. Polyhexanide versus metronidazole for odor management in malignant (fungating) wounds: A double-blinded, randomized, clinical trial. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2018;45(5):413-8.

- Lenselink E, Andriessen A. A cohort study on the efficacy of a polyhexanide-containing biocellulose dressing in the treatment of biofilms in wounds. J Wound Care, 2011;20(11):534-9.

- Hagelstein SM, Ivins N. Treating recalcitrant venous leg ulcers using a PHMB impregnated dressing: A case study evaluation. Wounds UK, 2013;9(4):84-90.

- Stanway S, Spruce P. A review of a foam dressing containing 0.5% polyhexamethylene biguanide under compression therapy in the management of lower limb ulceration. Geneva: EWMA; 2010.

- Vallejo A, Wallis M, Horton E, McMillan D. Low-frequency ultrasonic debridement and topical antimicrobial polyhexamethylene biguanide for use in chronic wounds: A case series. Wound Practice and Research, 2018;26(1):4-13.

- Johnson S, Leak K. Evaluating a dressing impregnated with polyhexamethylene biguanide. Wounds UK, 2011;7(2):20-5.

- Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

- Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. New JBI Grades of Recommendation. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2013.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. Supporting Document for the Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation. www.joannabriggs.org: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014.

- Fjeld H, Lingaas E. Polyhexanide - safety and efficacy as an antiseptic. Tidsskrift for Den norske laegeforening 2016;136(8):707-11.

- Bowen G, Spruce P. An evaluation of a foam dressing impregnated with 0.5% polyhexamethylene biguadine (PHMB) within the care pathway of the diabetic foot ulcer. UK: Wounds UK; 2009.

- Hübner NO, Kramer A. Review on the efficacy, safety and clinical applications of polihexanide, a modern wound antiseptic. Skin Pharm Physiol, 2010;23(Suppl 1):17-27.

- Barrett S, Battacharyya M, Butcher M, Enoch S, Fumerola S, Gray D, Stephen-Haynes J, Edwards-Jones V, Leaper D, Strohal R, White R, Wicks G, Young T. Consensus document: PHMB and its potential contribution to wound management. Aberdeen: Wounds UK; 2010.

- Gray D, Barrett S, Battacharyya M, Butcher M, Enoch S, Fumerola S, Stephen-Haynes J, Edwards-Jones V, Leaper D, Strohal R, White R, Wicks G, Young T. PHMB and its potential contribution to wound management. Wounds UK, 2010;6(2):40-6.

- Romanelli M, Dini V, Barbanera S, Bertone MS. Evaluation of the efficacy and tolerability of a solution containing propyl betaine and polihexanide for wound irrigation. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2010;23(Suppl):41S–4S.

- Wild T, Bruckner M, Payrich M, Schwarz C, Eberlein T, Andriessen A. Eradication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pressure ulcers comparing a polyhexanide-containing cellulose dressing with polyhexanide swabs in a prospective randomized study. Adv Skin Wound Care, 2012;25(1):17-22.

- Motta G, Milne C, Corbett L. Impact of antimicrobial gauze on bacterial colonies in wounds that require packing. Ostomy Wound Manag, 2004;8.

- Motta GJ, Trigilia D. The effect of an antimicrobial drain sponge dressing on specific bacterial isolates at tracheostomy sites. Ostomy Wound Manage, 2005;51(1):60–6.

- Sibbald R, Coutts P, Woo K. Reduction of bacterial burden and pain in chronic wounds using a new polyhexamethylene biguanide antimicrobial foam dressing-Clinical trial results. Adv Skin Wound Care, 2011;24(2):78-84.

- Eberlein T, Haemmerle G, Signer M, Gruber-Moesenbacher U, Traber J, Mittlboeck M, et al. Comparison of PHMB-containing dressing and silver dressings in patients with critically colonised or locally infected wounds. J Wound Care, 2012;21(1):12-20.

- Bowen G, Spruce P. An evaluation of a foam dressing impregnated with 0.5% polyhexamethylene biguadine (PHMB) within the care pathway of the diabetic foot ulcer. UK: Wounds UK; 2009.