Volume 30 Number 3

Building wound care capability: the development of an education and training directory for health professionals in Australia

Christina Parker, Andrew Francis, Laura Robson and Angela Jones

Keywords Wound care, education, recommendations, directory

For referencing Parker C et al. Building wound care capability: the development of an education and training directory for health professionals in Australia. Wound Practice and Research 2022; 30(3):143-149.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.30.3.143-149

Submitted 8 December 2021

Accepted 24 February 2022

Abstract

Aim To identify and categorise active wound care education courses available to healthcare workers in Australia in order to establish an accessible wound care education resource directory.

Method A modified point prevalence enquiry of active wound care education courses was conducted in 2021. Data was collected via an initial desk search, with follow-up by direct contact with education course providers and representative wound care professionals as required to identify and categorise wound care education courses.

Results Sixty-one (61) currently available active wound care educational courses available to healthcare workers met the inclusion criteria for identification and categorisation, providing the content for an online accessible wound care education resource directory.

Conclusion Access to wound care educational courses in Australia is ad hoc, with courses identified as available from a wide range of providers. The identification and categorisation of these courses providing the content for an online accessible wound care education resource directory will likely improve access to knowledge and treatments leading to improved consumer outcomes.

Impact

What is already known?

Anecdotally, it has proven difficult for healthcare workers to locate wound care educational courses applicable to their personal and professional circumstances. This has likely resulted in a high variability of practice and lack of evidence-based wound care approaches for consumers in differing care settings, as well as in differing geographical locations (e.g. differing states and metropolitan vs regional/rural/remote locations).

What does this project contribute?

- This project confirmed that access to information regarding wound care educational courses in Australia is ad hoc, with courses available from a wide range of providers. Accessing accurate and current information about available courses is challenging for healthcare workers.

- A directory of current active wound care educational courses available to healthcare workers has been developed and will be made available on a publicly accessible website.

- It is anticipated that the establishment and maintenance of a robust single directory of education resources will improve access to wound care knowledge and treatments leading to improved consumer outcomes.

Introduction

Chronic wounds are a large burden on healthcare budgets, with care of chronic wounds comprising up to 4% of the total healthcare expenditure in western countries1–3. In Australia this equates to approximately A$3 billion annually4. These wounds can be debilitating and often result in a decreased quality of life5,6. Despite Australian and international studies regarding wound care demonstrating a lack of knowledge, poor application of knowledge, and a need for improved access to education for undergraduate and post-graduate healthcare workers, anecdotally it remains difficult for healthcare workers to locate and participate in wound care educational courses applicable to their personal and/or professional circumstances7–10.

The scope of work environments and the breadth and range of qualifications and skills of healthcare workers in the various clinical settings is broad and spans vastly different needs. For example, the educational needs of high level formal postgraduate qualifications for relatively small numbers of dedicated specialty wound care practitioners are very different to the educational needs of large numbers of more generally qualified healthcare workers such as support care workers, assistants in nursing or general registered nurses working in non-specialty areas or in aged care or disability care settings. In these latter environments, a focus on prevention and management of pressure injuries and skin tears (with the ability to draw upon specialty expertise when required) may well be more appropriate.

It is recognised that specialty academic courses exist and are available, and that there are appropriate professional organisations and accredited private and industry-sponsored training resources available. However, currently, a single readily accessible comprehensive list of all wound care-related education and training courses for healthcare workers in Australia does not exist.

Objective

To undertake a modified point prevalence enquiry of individual state/territory/national and international wound care-related courses that require active participation by enrolees, and to facilitate the development of a single accessible publicly available wound care education resource directory of active formal education courses.

Methods

Data sources

The methodological approach was broadly based upon, and adapted from, an accepted international methodology to uncover and assimilate broad data and information from widely disparate and non-standardised sources11. The project was undertaken during 2021 and involved two major approaches to searching for data sources:

- Desk research – website/grey literature search.

- A data collection tool (where appropriate) including a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods.

Primary data sources were identified as:

- Organisational websites and/or Google searches.

- Data collection tool emailed as appropriate.

Secondary data sources were identified as:

- Websites/grey literature, including relevant links identified from the primary data sources.

- State/territory and national contacts, collaborators, wound care leaders.

- State/territory Wounds Australia committee members.

Course selection

All attempts were made to ensure that as many courses as possible were detailed for potential inclusion in a resource directory.

Inclusion criteria included all active wound care courses that have been assessed by the senior project team members as having more than 50% content applicable to chronic or ‘hard to heal’ wounds were included in this data collection. The types of wounds that were included were diabetic foot ulcers, foot ulcers, pressure injuries, leg ulcers or wounds that have the potential to become chronic or hard to heal. Additionally:

- An ‘active’ course was defined as one that requires formal and interactive participation by the enrolee.

- A chronic wound was defined as a wound that occurs when the reparative process does not proceed through an orderly and timely process as anticipated, and healing is complicated and delayed by intrinsic and extrinsic factors that impact on the person, their wound and their healing environment12.

- All courses needed to be publicly available.

Exclusion criteria included:

- Passive and non-interactive educational events, including webinars, conferences, online videos etc.

- Acute wounds.

- Courses not publicly available.

- Courses not currently available.

Desk research

While published literature and healthcare databases bear consideration, information regarding available wound care educational resources is not primarily published or collated in these arenas, and much of the available information regarding educational resources pertaining to the prevention and management of wound care and pressure injuries in Australia is to be found in the grey literature, including websites and material with limited circulation. We engaged the various state and territory project leaders to identify these sources and conducted a detailed website/grey literature search.

For each website identified, an initial review of the site was performed targeting clearly identifiable resources such as drop-down menus and/or webpage tabs on potentially relevant topics/headings including: ‘Education’/’Clinical Education’/’Education & Training’; ‘Resources’; ‘Courses’; ‘Learning Centre/Academy’; ‘For Professionals/Healthcare Professionals’; ‘Wound Management’; ‘e-Health’; ‘e-Learning’; ‘Events’; ‘CPD’; ‘Knowledge/Knowledge hub’; ‘Online store or Catalogue’.

Searches of the website for key words were also used. As sites that did not have the above-listed major headings/links to resources were much less likely to have applicable relevant resources, search terms were broad to endeavour to capture all relevant resources available. Search terms used included: ‘course’; ‘education’; ‘wound’; ‘ulcer’; ‘dressing’; ‘pressure’; ‘debride’.

The use of more specific search terms, and even the broad search terms used to try to maximise the yield of searches and identify all relevant courses, was often minimal or nil. Further, depending upon the database/grey literature being searched, search terms were modified/limited to identify any possibly relevant information, or to exclude numerous inappropriate/inapplicable results.

Educational courses were broadly grouped into eight course provider types (international courses, hospital/health service-based courses, community health and aged care-related courses, professional organisations, teaching and research institutions, university-based courses, industry courses and other privately provided courses). Within each category, key organisations were identified and searched. Additional organisations and links identified from each website were also further explored.

Data collection tool

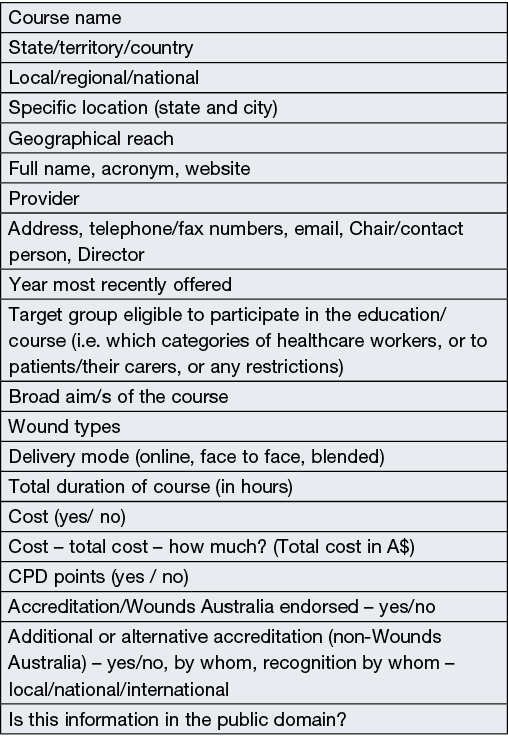

Design of the data collection tool was based on previous studies and was determined by the research group to be the most common requirements that healthcare workers are seeking when searching for wound care courses, but also ensuring the data on the directory was not likely to change regularly which would be an issue for the accuracy, currency and sustainability of the directory. Following from previous work, professional experience in the field, and the desk research (above), the data collection items were initially developed by the research team and then further refined through consultation and review with the larger project group (the variables collected in the data collection tool are provided in Box 1).

Box 1. Data collection tool

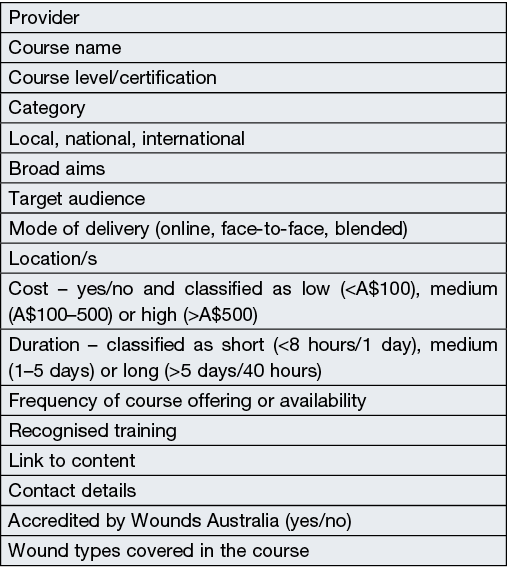

This specific information regarding each available course was then consolidated and categorised for inclusion in the directory. The included variables are shown in Box 2.

Box 2. Included variables

Results

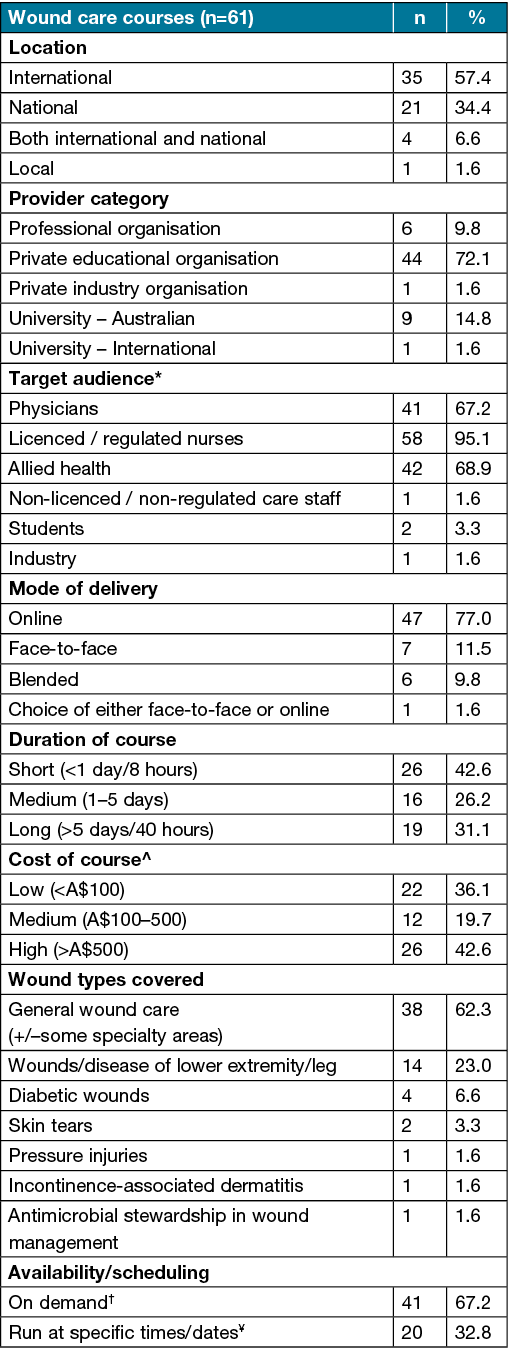

Searches and enquiries yielded a total of 130 courses, of which 61 met the criteria for final inclusion in the directory. The main reasons for exclusion included past events/outdated information, discontinued courses and/or an inability to determine whether courses were currently active (potentially an impact of COVID‑19) or that the courses were regularly conducted. Of the identified courses, ten were provided by universities and 51 were provided by non-university providers, either private or professional. Broadly, identified education course providers included one international university, nine Australian universities, 44 private educational organisations, six professional organisations, and one industry organisation. Table 1 provides further details of the courses identified.

Table 1. Details of courses identified and meeting inclusion criteria

* Does not add to 100% as many courses had a target audience of more than one type

^ One course = cost not stated; one course = membership discount reduces cost to ‘low’ category

† Includes one course with choice of on demand or scheduled face-to-face

¥ Excludes one course currently on hold due to COVID‑19

All courses were noted to be suitable for a range of health professionals. Most courses are targeted towards regulated nursing staff and/or other registered health professionals. However, only one course included modules or ‘sub-courses’ that were aimed at care workers or unregulated healthcare staff.

Discussion

Active wound care educational courses for healthcare workers are available from a broad range of providers, including formal academic institutions, international, Australian and local professional organisations, private education providers, industry/product supplier organisations and healthcare employers, including public and private healthcare organisations. There is wide variability in the style, nature, content and cost of these courses both within Australia and internationally, and the breadth of courses available spans a broad range across numerous domains. The majority of available courses cover general wound care and/or wounds of the lower extremity and are targeted towards regulated nurses and/or other healthcare professionals.

However, when considering the ability for healthcare workers to access these educational resources, the majority (62.3%) of courses are of medium to high cost and, despite the well-recognised risks of skin tears, pressure injuries and chronic wounds in both disability and aged care settings, very few courses are available to non-regulated healthcare support/patient care workers providing care to individuals in these high risk settings.

The widespread use of the internet over recent decades has delivered both advantages and disadvantages for healthcare education. Unsurprisingly, the majority of courses are available exclusively online (77.0%) and on demand (67.2%), reflecting the relative ease and low cost afforded by the medium, as well as delivering the benefit of widespread accessibility both nationally and internationally13–15. Further, there is perhaps a presumption of equality of costs and access to available online educational resources in rural/remote locations compared to inner urban locations that may not reflect the reality for some healthcare workers.

A specific further challenge encountered was the unique timing of the project during the worldwide COVID‑19 pandemic. During the project it became very clear that educational courses that may have been planned or scheduled (e.g. local or regional face-to-face events across Australia) were either converted into online only events or cancelled completely due to the impact of COVID‑19 directly and/or government-mandated restrictions. This has potentially skewed the results for both the number and range of courses available, as well as the proportion of courses provided via each mode of delivery. Further, if providers failed to respond to queries about their courses to ascertain whether they met the inclusion criteria, possibly relevant courses were excluded from the directory database.

Recommendations

While the directory of current active wound care educational courses developed via this project will be made available to healthcare workers on a publicly accessible website and will be of great benefit to those seeking to access the most appropriate active wound care course, the development of this directory has led to a number of further recommendations going forward.

1. Ongoing maintenance and support should be provided for a permanent single location to host the directory listing all currently available active wound care-related educational courses available for healthcare workers and support workers caring for people or working in aged-care or disability care sectors in Australia. This should include:

a. A master list containing ALL courses, but then categorised and searchable/selectable for the variety of healthcare workers and aged-care/disability-care/support workers that may be looking for this information.

b. If/when relevant courses become available, the directory should also include a separate sub-list (sub directory) of resources and courses applicable to and available for consumers/relatives/carers to aid their independence and improve their ability for autonomy and self-care. This would therefore reduce the need, reliance and costs associated with a healthcare/wound care system requiring all aspects of wound care to be personally provided by a qualified healthcare worker with specialty expertise in wound management.

c. In order to ensure currency and accuracy of the directory, there will be a need to update this directory regularly.

2. Associated with the directory, an online selection tool should be established to aid the ability of all categories of healthcare and other relevant workers to readily identify and select courses relevant and applicable to their personal needs and individual circumstances.

3. A formal ‘Guideline’ of requirements for providers of educational courses in wound care in Australasia should be developed, clearly documenting all requirements for courses that are to be considered for inclusion on the directory (i.e. mandatory inclusion criteria and minimum data requirements).

a. A template/table structure aligned to the structure of the online directory may be appropriate and could be largely based upon the data collection tool.

b. A communication strategy should be developed and executed in order to communicate the directory and the guideline to providers of wound care education and to healthcare and relevant workers and their employers.

4. Academic institutions and other organisations should be encouraged to establish a broader range of wound care-related educational courses. This should be encouraged across the spectrum of knowledge levels, target audiences and cost thresholds, and include an effective mechanism to deliver the necessary practical components of wound care education to meet the needs of:

a. the broad range of healthcare workers and other relevant workers in order to enhance and improve workforce knowledge and skills thus improving quality of wound care.

b. consumers and unregulated workers (by providing appropriately focused courses) as this will empower and encourage independence and improve care and quality of life.

c. undergraduates/students (by ensuring that health professional baccalaureate courses include the necessary wound care knowledge/skill requirements for graduating students).

5. A formal ‘Guideline’ of requirements for providers of healthcare baccalaureate courses in Australasia regarding wound care-related knowledge/skills should be developed. This guideline should clearly document minimum mandatory requirements in these courses.

6. Further considerations of relevance for consideration when developing or enhancing wound care courses include:

a. While all courses must have appropriate academic rigour and standards, not all courses need to lead to formal qualifications and consideration should be given to providing low-cost open access courses to suit specific target audiences and/or clinical conditions.

b. Structuring wound care education courses using a ‘unitised’ model may aid delivery of education on targeted topics to various categories of healthcare and other relevant workers and consumers/carers who are seeking knowledge on specific topics/conditions/treatments. This may improve access, reduce costs, and thereby improve uptake of wound care education. Such an approach may also allow inclusion of some wound care units/topics into baccalaureate healthcare courses as either mandatory or elective subjects/elements.

7. Consideration should be given to undertaking further research in order to assess the impact of this project and establishment of the directory. Areas/topics for consideration in future project/s could include:

a. A survey/audit of a representative random selection of workers in different care settings to assess:

i. Historical/past access to information about, and past participation in, wound care education courses.

ii. Awareness of the directory and accessibility of educational course information.

iii. Use of/intention to use the directory.

iv. Actual participation in wound care education courses since directory became available.

b. A survey/audit of education providers in each category to assess:

i. Historical/past uptake of wound care education courses provided.

ii. Awareness of the guidelines and directory regarding educational course information/requirements.

iii. Use of/intention to use the directory to encourage uptake of provided courses.

iv. Proposed and/or actual changes to the wound care courses offered, e.g. range of courses/cost/target audience/wound types covered.

c. A scoping project to assess the areas of weakness in wound care knowledge/skills of the various categories identified under Recommendation 5 above – to inform detailed planning for development of education courses that will meet the specific needs of each group, address the identified weaknesses, and thus improve healthcare delivery and patient outcomes.

Further recommendations

While it was not formally assessed as part of the project, feedback received during the course of the project highlighted numerous requests from graduates of baccalaureate healthcare courses seeking wound care education. This suggests an underlying lack of knowledge, skills and confidence regarding wound care felt by graduates of these baccalaureate courses which could warrant further research and investigation.

COVID‑19, as has been indicated, has impacted on the delivery of education; this has been challenging due to the nature of wound care education which is best delivered with both theory and practical components. This has led to cancellation of some courses entirely, changes to delivery in the form of online content, and the cancellation of practical sessions. This is likely to have ongoing impacts to wound care education. While recommencement of some courses and a significant shift to online theoretical content is anticipated in the post-pandemic period, the key practical elements of wound care education will inevitably necessitate a means of delivering essential practical knowledge and skills to healthcare workers in order to improve standards of wound care and patient outcomes.

Limitations

We acknowledge that active formal wound care courses are a small part of education for healthcare professionals and that many other resources – including conferences, workshops, guidelines and journal reading – could have also been included in educational content. However, it was outside the scope of this project to include everything and/or include education content that regularly changes. We have focused on the first step of identifying and categorising active formal wound education courses that could be managed in an online directory and that would remain sustainable over a period of time. Once the directory is developed there is potential to include further information and/or links to other resources; however, this needs to avoid unnecessary duplication and remain manageable.

This project encountered some of the disadvantages of the current online mode of communication and content delivery with numerous challenges relating to outdated information, discontinued but still publicly advertised courses/organisations, and non-working links/URLs.

It should also be noted that the quality of courses was not assessed in this project.

Conclusion

Access to active educational courses relevant to wound care in Australia is ad hoc, with courses available from a wide range of providers, from formal academic institutions through to industry-sponsored courses, other private providers, and special interest professional groups.

The difficulties encountered during this project reflect the challenges encountered by healthcare workers trying to find relevant current information and trying to access and participate in such courses. The relatively high costs of most courses and the lack of availability of courses to all relevant workers, particularly in the aged-care and disability care sectors, highlight a significant gap that provides an ‘opportunity for improvement’, i.e. that warrants addressing. Thus, beyond simply identifying currently available active wound care education courses and establishing a publicly available resource directory of these, this project has taken the opportunity to develop a series of recommendations that should lead to more robust and improved access to wound care education for both healthcare workers, other relevant workers, and potentially in future for consumers and their carers, thus ultimately leading to improved consumer care and reducing the impact, burden and costs of chronic wounds on the community and on the healthcare system.

Acknowledgements

Contributions from our expert advisory group from across Australia are appreciated and acknowledged in this work.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors. Dr Parker is a member of, and committee member of, Wounds Australia. Dr Parker is a paid academic of Queensland University of Technology. Drs Parker and Francis are project leads/team members commissioned by Health Translation Queensland and Dr Jones and Ms Robson are team members of Monash Partners.

Ethics statement

An ethics statement is not applicable.

Funding

This project was supported by the Australian Government’s Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) Rapid Applied Research Translation program grant awarded to Brisbane Diamantina Health Partners (now known as Health Translation Queensland).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to conceptualisation and methodology. All authors contributed to screening, critical appraisal, data extraction and data synthesis, and all authors were responsible for manuscript preparation including providing feedback and critical comments on the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final paper manuscript.

Author(s)

Christina Parker*1,2, Andrew Francis1,3, Laura Robson4 and Angela Jones4

1Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Victoria Park Road, Kelvin Grove, QLD 4059, Australia

2Centre for Healthcare Transformation, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology (QUT),

Victoria Park Road, Kelvin Grove, QLD 4059, Australia

3Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4029, Australia

4Monash Partners Academic Health Science Centre, 43–51 Kanooka Grove, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia

*Corresponding author Email christina.parker@qut.edu.au

References

- Bennett G, Dealy C, Posnett J. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age Ageing 2004;33:230–5.

- Posnett J, Franks P. The cost of skin breakdown and ulceration in the UK: the silent epidemic. Hull: Smith and Nephew Foundation; 2007.

- Guest JF, Ayoub N, McIlwraith T, Uchegbu I, Gerrish A, Weidlich D, et al. Health economic burden that wounds impose on the National Health Service in the UK. BMJ Open 2015;5(12):e009283-e.

- Graves N, Zheng H. Modelling the direct health care costs of chronic wounds in Australia. Wound Pract Res 2014;22(1):20–33.

- Chase SK, Whittemore R, Crosby N, Freney D, Howes P, Phillips TJ. Living with chronic venous leg ulcers: a descriptive study of knowledge and functional health status. J Community Health Nurs 2000;17(1):1–13.

- Persoon A, Heinen MM, van der Vleuten CJM, de Rooij MJ, van de Kerkhof PCM, van Achterberg T. Leg ulcers: a review of their impact on daily life. J Clin Nurs 2004;13(3):341–54.

- Innes-Walker K, Edwards H. A wound management education and training needs analysis of health consumers and the relevant health workforce and stocktake of available education and training activities and resources. Wound Pract Res 2013;21(3):104–9.

- Kielo E, Salminen L, Stolt M. Graduating student nurses’ and student podiatrists’ wound care competence – an integrative literature review. Nurse Educat Pract 2018;29:1–7.

- McCluskey P, McCarthy G. Nurses’ knowledge and competence in wound management. Wounds UK 2012;8(2):37–47.

- Zulkowski K, Capezuti E, Ayello EA, Sibbald R. Wound care content in undergraduate programs: we can do better. WCET J 2015;35(1):10–3.

- Bello AK, Johnson DW, Feehally J, Harris D, Jindal K, Lunney M, et al. Global Kidney Health Atlas (GKHA): design and methods. Kidney Int Suppl 2017;7(2):145–53.

- Wounds Australia. Standards for wound prevention and management. 3rd ed. Osborne Park, WA: Cambridge Media; 2016.

- Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of e-learning in medical education. Academ Med 2006;81(3):207–12.

- Detroyer E, Dobbels F, Debonnaire D, Irving K, Teodorczuk A, Fick DM, et al. The effect of an interactive delirium e-learning tool on healthcare workers’ delirium recognition, knowledge and strain in caring for delirious patients: a pilot pre-test/post-test study. BMC Med Education 2016;16(1):17-.

- Sinclair PM, Kable A, Levett-Jones T, Booth D. The effectiveness of internet-based e-learning on clinician behaviour and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;57:70–81.