Volume 30 Number 4

The financial burden of diabetes-related foot disease in Australia: a protocol for a systematic review

Nicoletta Frescos, Shirley Jansen, Lucy Stopher and Michelle R Kaminski

Keywords diabetic foot, amputation, cost analysis, diabetes-related foot disease, diabetes-related foot ulcer

For referencing Frescos N et al. The financial burden of diabetes-related foot disease in Australia: a protocol for a systematic review. Wound Practice and Research 2022; 30(4):223-227.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.30.4.223-227

Submitted 19 April 2022

Accepted 17 May 2022

Abstract

Background Diabetes-related foot disease (DFD) is one of the most common, costly and severe complications of diabetes, which poses a substantial burden on patients, healthcare systems and society. Contemporary data on the financial burden of DFD treatment in Australia is ambiguous. Therefore, the aim of this proposed protocol is to identify, summarise and synthesise existing evidence by undertaking a systematic review to estimate the costs associated with DFD treatment in Australia.

Methods This systematic review will conduct searches in MEDLINE, Embase, AMED, CINAHL, Joanna Briggs Institute EBP and the Cochrane Library from November 2011 to November 2021. Peer-reviewed articles evaluating the costs associated with DFD treatment within Australia will be included. Study quality and risk of bias will be assessed using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS 2022). A meta-analysis of estimated costs will be performed if data from included studies are sufficiently homogenous, otherwise, a narrative synthesis will be used.

Discussion The results of this systematic review will provide insight into the current economic impact of DFD management within Australia. Such data may help to inform optimisation of national service delivery and result in improved outcomes for individuals with DFD in Australia.

Registration PROSPERO Registration No. CRD42022290910

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a highly prevalent chronic health condition, with over 537 million people living with diabetes globally1. Diabetes-related foot disease (DFD) is a serious limb-threatening complication encompassing diabetes-related foot ulceration, infection, ischaemia, and lower limb amputation. DFD is known to negatively impact health-related quality of life2 and poses a substantial personal and financial burden on patients, healthcare systems and society3. The prevalence of DFD has been reported to affect 4.6–4.8% of the global population4,5. DFU has a lifetime incidence between 19–34%, and an annual incidence of 2%6–8. Following successful wound closure, recurrence rates for DFU are high, where 40% will reoccur within 1 year and 60% within 3 years7–9.

DFU is a growing problem and is recognised as a leading cause of hospital admissions and lower limb amputations worldwide10. It is estimated that every 30 seconds a lower limb (or part of a lower limb) is amputated due to DFU11,12. In addition, chronic DFUs and amputations are associated with early death, where up to 70% of patients who undergo a diabetes-related amputation will die within a 5-year period, which is higher than some cancers7. Importantly, these figures are likely to be underestimated due to poor data collection in low-income countries and a high proportion of undiagnosed diabetes13.

In Australia, it is estimated that 50,000 people are living with DFU. This equates to approximately 28,000 hospital admissions, 4,500 lower limb amputations and 1,700 deaths attributable to DFU each year10,14–16. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of Australian data reported a DFD prevalence of 1.2–1.5% within diabetes populations and 7.0–15.1% within inpatients with diabetes17. For diabetes-related amputations, the reported incidence is 5.2–7.2 per 1000 person-years within diabetes populations, and the prevalence of amputations during hospitalisation is between 1.4-5.8%17.

The financial burden of DFD can vary greatly as it often depends upon the severity, healing outcomes, patient factors, management approaches, and the interventions used17. Direct healthcare costs of DFD may include long and repeated hospital stays and high bed occupancy, rehabilitation, medications, materials (e.g. wound dressings, offloading devices), diagnostic tests and imaging, artificial limbs and surgical procedures (e.g. revascularisation)18,19.

In the United States (US), the annual healthcare expenditure for diabetes is estimated to be around US$966 billion1 where one third of these direct costs are attributable to care for DFD20. In 2015, the annual cost of DFU and amputation in the United Kingdom (UK) has been estimated to be between £837 million and £962 million, with 90% of this expenditure attributable to prolonged and severe ulceration19. The average weekly cost per patient for DFU treatment (i.e. clinic attendances, podiatry, imaging, prescriptions, hospital outreach, orthotics, district nursing, wound dressings and other consumables) in the primary care setting in the UK is approximately £26619. In Europe, the estimated direct and indirect annual expenditure for DFU management at the individual level ranges from €7722 to €20064 based on the Eurodiale study21. A systematic review which converted the costs to equivalent 2016 US$ reported the total cost per patient per year of an uninfected ulcer was US$6,174 in 2002, but increased to US$14,441 in 200522. More specifically, the estimated cost to heal an ulcer in Belgium is US$10,572, while in Sweden it is over double the cost at US$24,9653. In France, the monthly healthcare expenditure for DFU management is US$1,2653.

In Australia, the estimated direct costs on the Australian public hospital system for DFD management is A$348 million, while the overall direct costs to the Australian health system is projected to be around A$1.57 billion10. The associated total care costs of DFU in residential care were US$11 million, with a standard deviation of US$3.01 million23. On average, the total admission cost per patient for a minor and major amputation is A$18,153 and A$68,307, respectively24.

Contemporary data on the financial burden of DFD treatment in Australia is ambiguous, particularly the breakdown of direct unit costs at the individual level in primary, secondary and tertiary care settings. To obtain a holistic understanding of the economic impact of DFD, more detailed information is required on the utilisation of resources and services. Such costs may include consultations with various healthcare professionals, diagnostic tests and imaging, medications, provision of wound dressings and offloading devices, vascular surgery, hospital admissions and rehabilitation.

Given the rising prevalence of DFD and foot-related hospital admissions for specialist care, understanding the costs is critical to ensure policy makers can make informed decisions on preventative strategies and best practice management to reduce the economic impact and improve outcomes in individuals with DFD in Australia. Therefore, the aim of this proposed protocol is to identify, summarise and synthesise existing evidence by undertaking a systematic review to estimate the costs associated with DFD treatment in Australia.

Methods

Registration

The protocol of this systematic review was prospectively registered with The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) – Registration No. CRD42022290910 and has been reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines25.

Search strategy

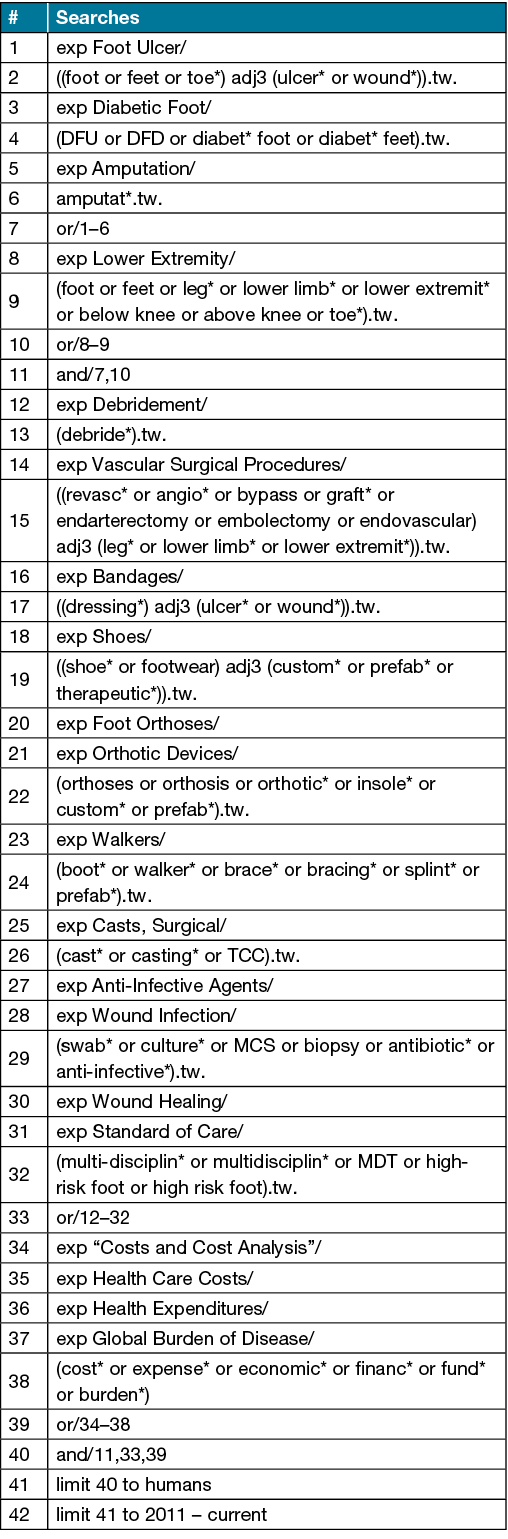

A comprehensive literature search of Australian studies will be conducted in MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), AMED (Ovid), CINAHL (Ebsco), Joanna Briggs Institute EBP (Ovid), and the Cochrane Library from November 2011 to November 2021 without language restriction. The MEDLINE search strategy is available in Supplementary File 1.

Eligibility criteria

Peer-reviewed Australian studies published between November 2011 and November 2021 investigating costs associated with DFD treatment will be eligible for inclusion. The population of interest will be individuals aged ≥18 years with DFD (i.e. DFU, infection, ischaemia, amputation) in any clinical setting. All reported costs for DFD treatment will be considered; however, treatments of particular interest may include visits to a healthcare professional, wound dressings, footwear and offloading devices, anti-infective agents, diagnostic tests/imaging, and/or surgical procedures (e.g. debridement, amputation, revascularisation). Single case reports/studies/series, expert opinion level V studies, protocols, abstracts without full text, conference proceedings, literature reviews, case-control, validity or reliability studies, letters, editorials, notes and short surveys will be excluded.

Data management

The search results obtained from the bibliographic databases will be initially exported into Endnote X9 (Thomson Reuters, New York, USA) and duplicate citations will be removed. All citations will then be imported into the Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) and any further identified duplicates will be removed.

Study selection

The Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) will be used during the study selection process. Two independent reviewers (NF and LS) will screen the titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria. The full-text articles of the remaining studies will be obtained and then examined independently by two reviewers (NF and MK), and studies deemed ineligible will be excluded. Any potential conflicts will be discussed between the two reviewers at each stage of the selection process and any disagreements will be resolved by a third party, if required. To ensure literature saturation, we will scan the reference lists and citations of the included studies to identify any other relevant studies and assess according to the eligibility criteria.

Data extraction

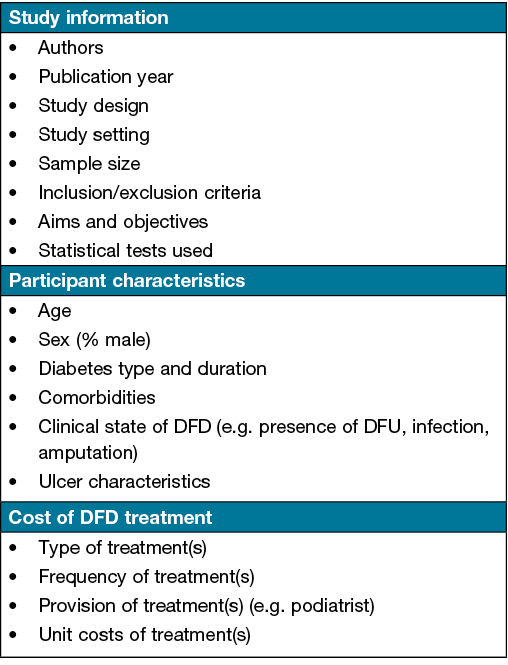

A data extraction form will be used to extract relevant study information (e.g. clinical setting), participant characteristics (e.g. clinical state of DFD) and any reported costs associated with DFD treatment (e.g. wound dressings). The type and frequency of DFD treatments and resource utilisation will also be of interest. Figure 1 provides an outline of the data to be extracted.

Figure 1. Data to be extracted from eligible studies

Data will be recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. One investigator (NF) will complete the data extraction. All extracted data will be checked for accuracy and omissions by a non-blinded second investigator (LS). Any potential conflicts will be discussed between the two authors and any disagreements will be resolved by a third party, if required. In cases where additional raw data is needed to complete meta-analyses, study authors will be contacted for unreported data or additional details. For continuous scaled outcomes, means, standard deviations, and sample sizes will be extracted. For nominal scaled outcomes, frequency counts and sample sizes will be extracted.

Study quality and risk of bias

The Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS 2022) statement will be used to assess study quality and risk of bias26. The CHEERS 2022 statement is a user-friendly 28-item checklist that is recommended for studies reporting on economic evaluations of health interventions to ensure that they are identifiable, interpretable, and useful for decision making26. Two reviewers (NF and MK) will independently appraise the quality and risk of bias of included studies. Any disagreements will be discussed and resolved by consensus. A third-party will be consulted if consensus cannot be reached, if required.

Data synthesis

A quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) will be performed using Review Manager (RevMan, Version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) if data from included studies are sufficiently homogenous. A meta-analysis of estimated costs for treatment of DFD is planned for all eligible studies. Pooled estimates will be calculated using a random-effects model where three eligible studies are available. Where meta-analysis is not possible due to heterogeneity across studies, a narrative synthesis will be used to summarise the characteristics and findings of included studies. The narrative synthesis will explore the findings both within and between included studies and will present any similarities, differences and patterns within the results27.

Discussion

The proposed systematic review protocol aims to identify, summarise and synthesise existing evidence to estimate the costs associated with DFD treatment in Australia. Given that DFD is one of the most common, costly and severe complications of diabetes and its prevalence is on the rise, understanding the financial burden of DFD is critical to ensure policy makers can make informed decisions on preventative strategies and best practice management. While both direct and indirect costs for DFD management are not easily quantified, this systematic review may assist in identifying and bridging gaps within the Australian literature and may guide future health economic evaluations in DFD. This in turn may inform optimisation of national service delivery, and ultimately reduce the economic impact and improve outcomes in individuals with DFD in Australia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

An ethics statement is not applicable.

Funding

This systematic review is funded by an unconditional grant by the URGO Foundation. The URGO Foundation is not involved in any other aspect of the project, such as the design of the project’s protocol and analysis plan, the collection and analyses and will have no input on the interpretation or publication of the study results.

Author contribution

NF, MK, SJ, LS conceived and designed the systematic review protocol. NF and MK drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Author(s)

Nicoletta Frescos1,2*, Shirley Jansen3–5 and Lucy Stopher4,5, Michelle R Kaminski1,2

1Discipline of Podiatry, School of Allied Health, Human Services and Sport, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

2Department of Podiatry, St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

3Curtin Medical School, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

4Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, WA, Australia

5Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, Perth, WA, Australia

*Corresponding author Email n.frescos@latrobe.edu.au

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 10th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2021.

- Khunkaew S, Fernandez R, Sim J. Health-related quality of life among adults living with diabetic foot ulcers: a meta-analysis. Qual Life Res 2018;28(6):1413–27.

- Raghav A, Khan ZA, Labala RK, Ahmad J, Noor S, Mishra BK. Financial burden of diabetic foot ulcers to world: a progressive topic to discuss always. Ther Adv Endocrin Metab 2018;9(1):29–31.

- Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, Tang S, Zhu D, Bi Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med 2017;49(2):106–16.

- Zhang Y, Lazzarini PA, McPhail SM, van Netten JJ, Armstrong DG, Pacella RE. Global disability burdens of diabetes-related lower-extremity complications in 1990 and 2016. Diabetes Care 2020;43(5):964–74.

- Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Update on management of diabetic foot ulcers. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018;1411(1):153–65.

- Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N Engl J Med 2017;376(24):2367–75.

- Bus SA, Lavery LA, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, Raspovic A, Sacco ICN, et al. Guidelines on the prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020;36(S1):e3269.

- Huang ZH, Li SQ, Kou Y, Huang L, Yu T, Hu A. Risk factors for the recurrence of diabetic foot ulcers among diabetic patients: a meta-analysis. Int Wound J 2019;16(6):1373–82.

- Van Netten J, Lazzarini P, Fitridge R, Kinnear E, Griffiths I, Malone M, et al. Australian diabetes-related foot disease strategy 2018–2022: The first step towards ending avoidable amputations within a generation. Brisbane: Diabetic Foot Australia, Wound Management CRC. Available from: https://www.diabetesfeetaustralia.org/australian-diabetes-related-foot-disease-strategy-2018-2022/

- Yazdanpanah L, Shahbazian H, Nazari I, Arti HR, Ahmadi F, Mohammadianinejad SE, Cheraghian B, Hesam S. Incidence and Risk Factors of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Population-Based Diabetic Foot Cohort (ADFC Study)-Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Int J Endocrinol. 2018 Mar 15;2018:7631659. doi: 10.1155/2018/7631659. PMID: 29736169; PMCID: PMC5875034.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 8th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2017.

- Ogurtsova K, Guariguata L, Barengo NC, Ruiz PL, Sacre JW, Karuranga S, Sun H, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022 Jan;183:109118. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109118. Epub 2021 Dec 6. PMID: 34883189.

- Lazzarini PA, Hurn SE, Kuys SS, Kamp MC, Ng V, Thomas C, et al. Direct inpatient burden caused by foot-related conditions: a multisite point-prevalence study. BMJ Open 2016;6(6):e010811e.

- Lazzarini PA, Hurn SE, Kuys SS, Kamp MC, Ng V, Thomas C, et al. The silent overall burden of foot disease in a representative hospitalised population. Int Wound J 2017;14(4):716–28.

- Lazzarini PA, Gurr JM, Rogers JR, Schox A, Bergin SM. Diabetes foot disease: the Cinderella of Australian diabetes management? J Foot Ankle Res 2012;5(1):24.

- Zhang Y, van Netten JJ, Baba M, Cheng Q, Pacella R, McPhail SM, et al. Diabetes-related foot disease in Australia: a systematic review of the prevalence and incidence of risk factors, disease and amputation in Australian populations. J Foot Ankle Res 2021;14(1):8.

- Driver VR, Fabbi M, Lavery LA, Gibbons G. The costs of diabetic foot: the economic case for the limb salvage team. J Vasc Surg 2010;52(3 Suppl):17S-22S.

- Kerr M, Barron E, Chadwick P, Evans T, Kong WM, Rayman G, et al. The cost of diabetic foot ulcers and amputations to the National Health Service in England. Diabetic Med 2019;36(8):995–1002.

- Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res 2020;13(1):16.

- Prompers L, Huijberts M, Schaper N, Apelqvist J, Bakker K, Edmonds M, et al. Resource utilisation and costs associated with the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Prospective data from the Eurodiale Study. Diabetologia 2008;51(10):1826–34.

- Tchero H, Kangambega P, Lin L, Mukisi-Mukaza M, Brunet-Houdard S, Briatte C, et al. Cost of diabetic foot in France, Spain, Italy, Germany and United Kingdom: a systematic review. Annales d’Endocrinologie 2018;79(2):67–74.

- Graves N, Zheng H. Modelling the direct healthcare costs of chronic wounds in Australia. Wound Pract Res 2014;22:20-33.

- Pena G, Cowled P, Dawson J, Johnson B, Fitridge R. Diabetic foot and lower limb amputations: underestimated problem with a cost to health system and to the patient. ANZ J Surgery 2018;88(7–8):666–7.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, de Bekker-Grob E, Briggs AH, Carswell C, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMC Med 2022;20(1):23.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71.

Supplementary File 1. Search strategy example: Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to 4 November 2021