Volume 29 Number 4

The management of urinary incontinence in nursing homes: a scoping review

Joan Ostaszkiewicz, Leona Kosowicz, Jess Cecil, Deidree Somanader, Briony Dow

Licensed under CC BY 4.0

Keywords residential aged care, scoping review, urinary incontinence, evidence, nursing homes

For referencing Ostaszkiewicz J et al. The management of urinary incontinence in nursing homes: a scoping review. Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal 2023; 29(4):80-100.

DOI

10.33235/anzcj.29.4.80-100

Submitted 3 October 2023

Accepted 4 November 2023

Abstract

The aim of the research was to identify interventions for the management of urinary incontinence (UI) in nursing homes. A scoping review was conducted with methods adapted from The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015 methodology for conducting scoping reviews and reporting was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews guidelines. Findings were synthesised without meta-analysis. Databases that were searched were MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL, JBI Evidence-Based Practice Database and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from 2010 to September 2021. The search was augmented with hand searching.

A total of 3,885 records were located. After exclusions and screening of 370 full-text articles, 30 publications were included – seven systematic reviews, 15 randomised-controlled trials, seven quasi-experimental studies and one cohort study. Studies addressed toileting assistance programs, exercise programs, drug therapies, technology-based interventions, education programs and multi-component interventions.

Multi-component interventions facilitated by specialist healthcare professionals offer the strongest evidence. Evidence about exercise programs was limited and inconsistent, as was evidence for anticholinergics. Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation is unlikely to reduce rates of UI in nursing homes with residents with high rates of cognitive impairment. Further evidence is required on the use of telemonitoring systems. Education programs for staff that provide on-site support and competency-based learning, led by specialist healthcare professionals, improve staff knowledge, attitudes and compliance with assessments, toileting and documentation. Education about person-centred approaches is required to provide appropriate care for residents living with dementia.

We conclude that a multicomponent approach led by a specialist such as a nurse with advanced clinical and leadership skills offers the most benefit. Nursing home policies and practices should focus on education programs for staff, with interventions that increase residents’ choice, activity level, nutritional status, hydration and toileting opportunities.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) in nursing homes has physical, psychological, economic and social consequences for residents, their families and staff. Despite its impact, little is known about strategies for the organisation and delivery of care. Medically, incontinence is conceptualised as a symptom of an underlying condition that can be prevented and treated, even in frail older people in nursing homes1. International research suggests 50–70% of nursing home residents have UI2–5, making it an important policy and practice issue for nurses and the nursing profession. In many countries, the quality of continence care in institutional settings is not consistent with recommended prevention and treatment guidelines and falls far below the public’s expectations, as evidenced by the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry6 in the UK and the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety7 in Australia. However, understandings about what constitutes quality continence care in nursing homes vary8,9. As such, an investigation summarising the quantitative evidence about interventions for UI management is required.

The review

The causes of UI in nursing homes are multifactorial1. The International Consultation on Incontinence identifies both intrinsic (individual) and extrinsic (environmental) factors that increase nursing home residents’ risk of developing UI1. There is a mounting body of evidence to suggest that the processes of care in nursing home settings are not designed to promote therapeutic continence care for care-dependent older people6–10.

A modelling of risk factors for UI in nursing home residents living with dementia found the strongest predictor was impaired functional status, expressed and measured as dependence in activities of daily living (ADL)11. This is an important finding that highlights the need for interventions to optimise nursing home residents’ functional status and prevent premature decline.

Another potential cause of UI in nursing homes is a lack of assessment to identify potentially reversible causes. An early study from the US found up to 81% of nursing home residents had potentially reversible causes of UI that were rarely investigated or treated12.

UI has a negative impact on some domains of nursing homes residents’ quality of life (QOL)13. Xu and Kane13 compared the overall QOL of 8,620 eligible residents with and without UI from 371 nursing homes. Although UI was not associated with overall QOL, it decreased the QOL domains of dignity, autonomy and mood. Jerez-Roig et al.14 found 24.1% of residents with UI reported a severe impact on their QOL.

UI also impacts on nursing home residents’ physical health, increasing their risk of incontinence-associated dermatitis15, falls16, functional decline14 and death17. Organisational costs are another important consideration. Research from the US from 2003 reported that the cost of proactively managing UI in nursing homes over a 6-month period was US$586,436, with 46% attributed to direct labour costs alone18.

Toileting assistance programs have been the focus of prior research on the management of UI in nursing homes. Seminal research conducted by Schnelle19–23 demonstrated it was possible to reduce rates of UI immediately following the implementation of a toileting assistance program in this setting. The challenge has been for usual care staff to sustain these improvements in usual care conditions24. There is a lack of contemporary data about actual rates of toileting assistance programs in nursing homes, as well as evidence about the best ways to identify residents who would benefit from this intervention. Similarly, there are questions about the best ways to implement and sustain toileting assistance programs for residents who need this assistance.

To address the personal, social and financial costs of UI in nursing homes there is a need to better understand the range of interventions available and their evidence base. This information could inform workforce planning, research, future funding and policies and practice for nursing home care.

Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to map and summarise the body of quantitative evidence about interventions for the management of UI in nursing homes. The PICO question was What interventions have been trialled for the management of UI in nursing homes and what is their effectiveness?

Methods

Design

A scoping review was conducted using methodology adapted from The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) reviewers’ manual 2015 methodology for JBI scoping reviews25 and reporting methods were guided by PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews) guidelines26. The rationale for conducting a scoping review rather than a systematic review was to map research about interventions for the management of UI in nursing homes, ie, to identify interventions that have been evaluated using quantitative research methods.

Search methods

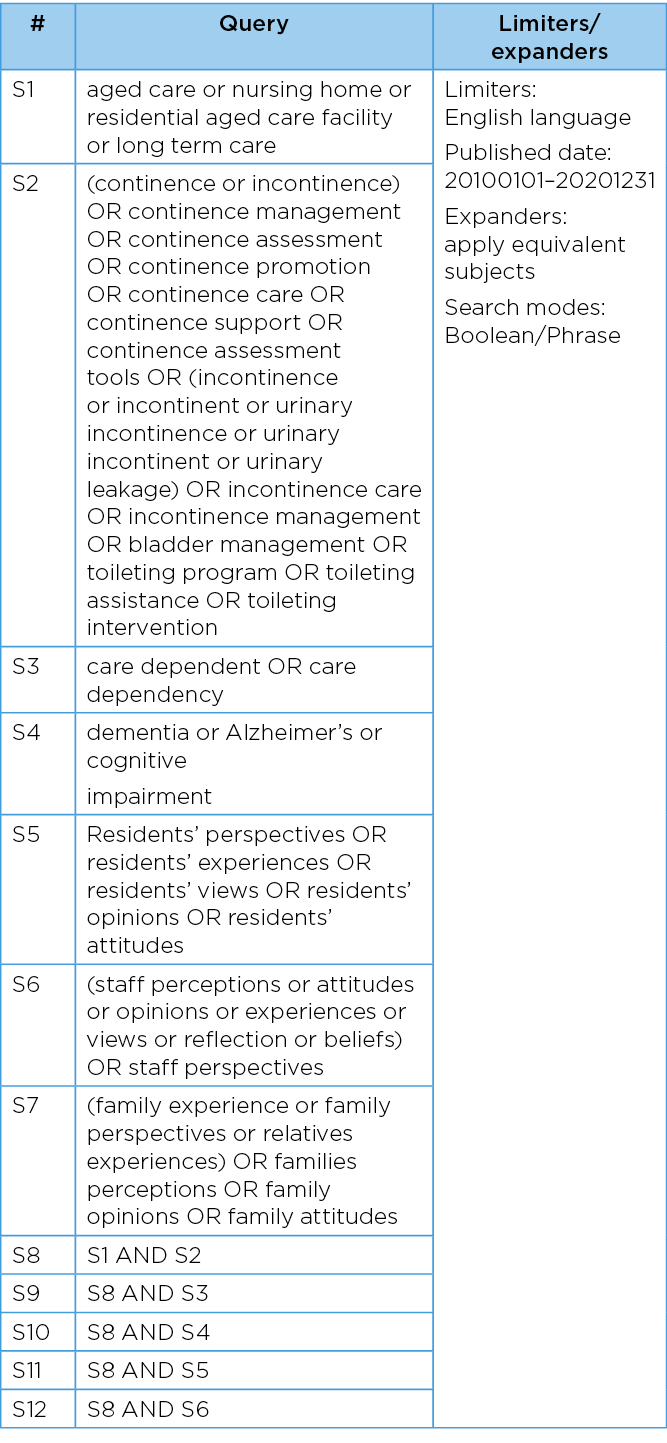

The bibliographic search of health and medical databases followed a three-step methodology described by the JBI guidelines. Firstly, limited searches of Ovid MEDLINE and CINAHL were conducted. An experienced librarian was consulted to assist with identifying relevant keywords from the titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved from this initial search. Secondly, a comprehensive search for English-language articles published from 2010 to September 2021 was performed using the finalised keywords and MeSH terms. Six electronic databases were comprehensively searched – MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL, JBI Evidence-Based Practice Database, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The search strategy is available in Table 1. Lastly, selected publications were hand searched for additional relevant references.

Table 1. Search strategy

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search was limited to primary sources and systematic reviews of primary sources. Grey literature and government reporting was excluded. Publications that evaluated interventions for the management of UI in nursing home residents were included. Publications that focused on the management of other types of incontinence (ie, faecal or dual incontinence), incontinence-associated dermatitis, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, urinary catheters or ostomies were excluded. Surgical interventions for the management of UI were also excluded.

Search outcome

All identified articles were imported into Covidence for screening (www.covidence.org). Three reviewers (LK, JO and DS) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all identified sources from the database search. Five reviewers (LK, JO, BD, JC and DS) then completed a full-text review of the remaining material, with conflicts resolved through consensus.

Data abstraction

A data extraction form was developed to identify the key characteristics of each study as well as relevant information regarding interventions for the management of UI in nursing homes. Three reviewers (LK, JO and DS) independently extracted the data and resolved inconsistencies through consensus. The variables included study objectives, methods, setting/sample characteristics, intervention type, outcomes measured, findings, and key recommendations.

Synthesis

Because of anticipated heterogeneity of included studies, findings were synthesised without meta-analysis27. They were then reported in narrative form according to the type of intervention, ie, toileting assistance programs, exercise programs, drug therapies, technology-based interventions, education programs, or multicomponent interventions.

Results

Search outcomes

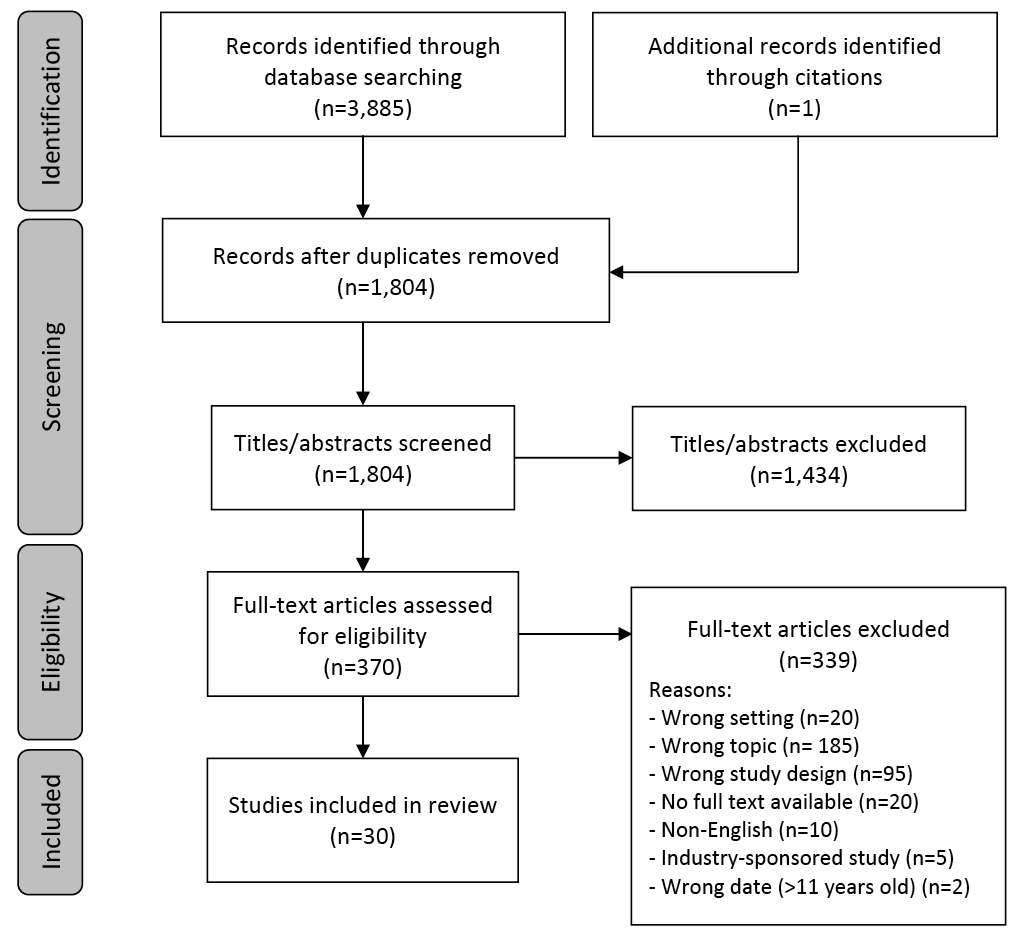

A total of 3,885 records were located through the database search, and one additional study was found through citations. Of the publications identified, 30 were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). This included seven systematic reviews28–34, 15 randomised-controlled trials (RCTs)35–49, seven quasi-experimental studies50–56 and one retrospective cohort study57. The majority of intervention studies were from Europe (n=10, 43.6%), while the remaining studies were from the US (n=7, 30.5%), Asia (n=3, 13%), Australia (n=1, 4.3%), New Zealand (n=1, 4.3%) and Iran (n=1, 4.3%).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of study selection process

Characteristics of included studies

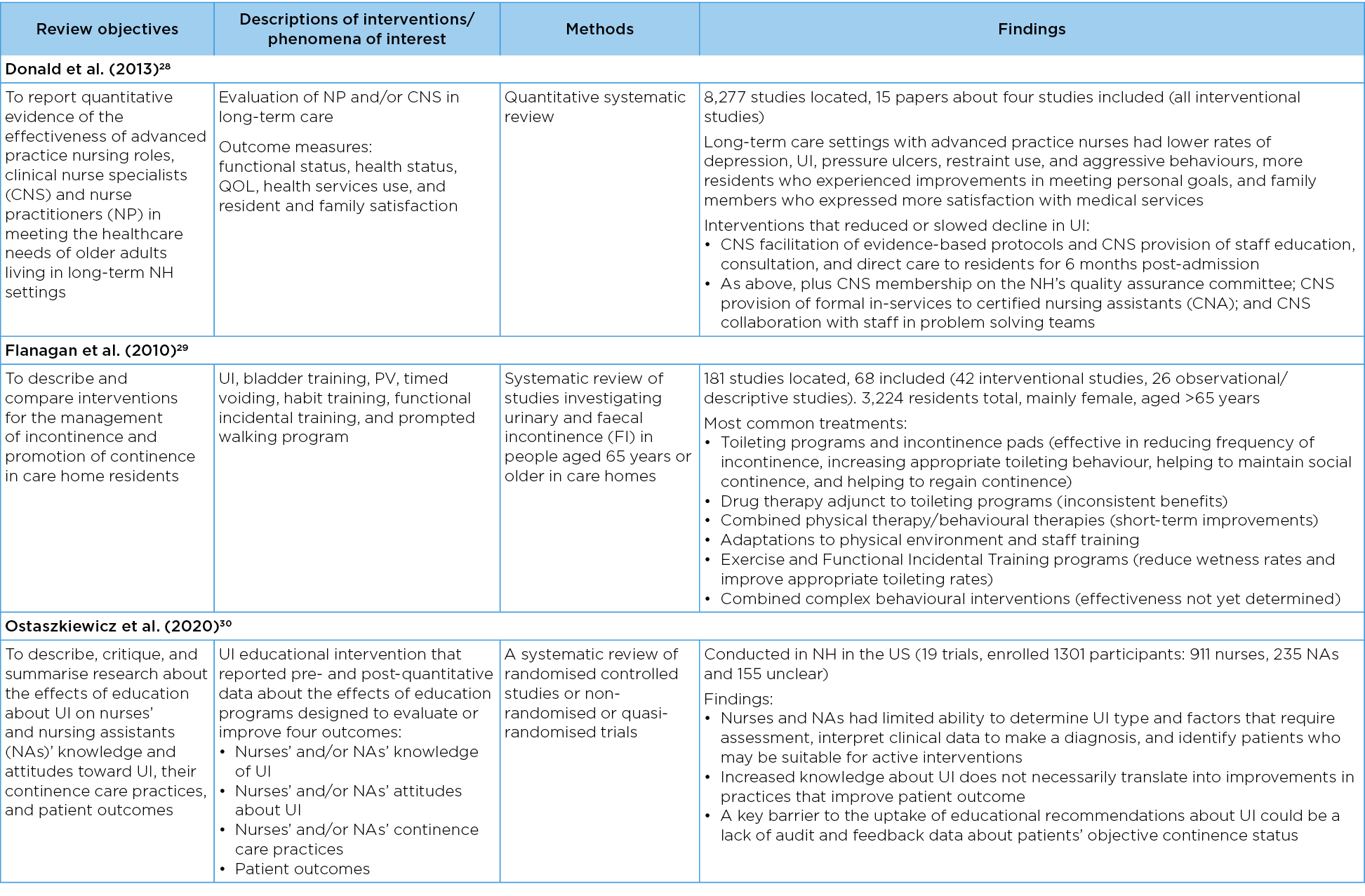

Of the 30 included publications, six evaluated toileting assistance programs29,31,32,42,46,55, four addressed exercise programs29,34,47,48, three addressed drug therapies29,33,57, and two described a technology-based intervention37,56. A total of 11 publications described the effects of education programs for nursing home staff38–41,44,45,49,51–54 and six evaluated multicomponent interventions29,28,35,36,43,50. There was considerable heterogeneity with respect to the types of interventions, how they were delivered (ie, duration, intensity, components), and how outcomes were evaluated. Therefore, there is no one intervention that can be recommended over another. The following section describes the evidence for each intervention type; detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in Tables 2–5.

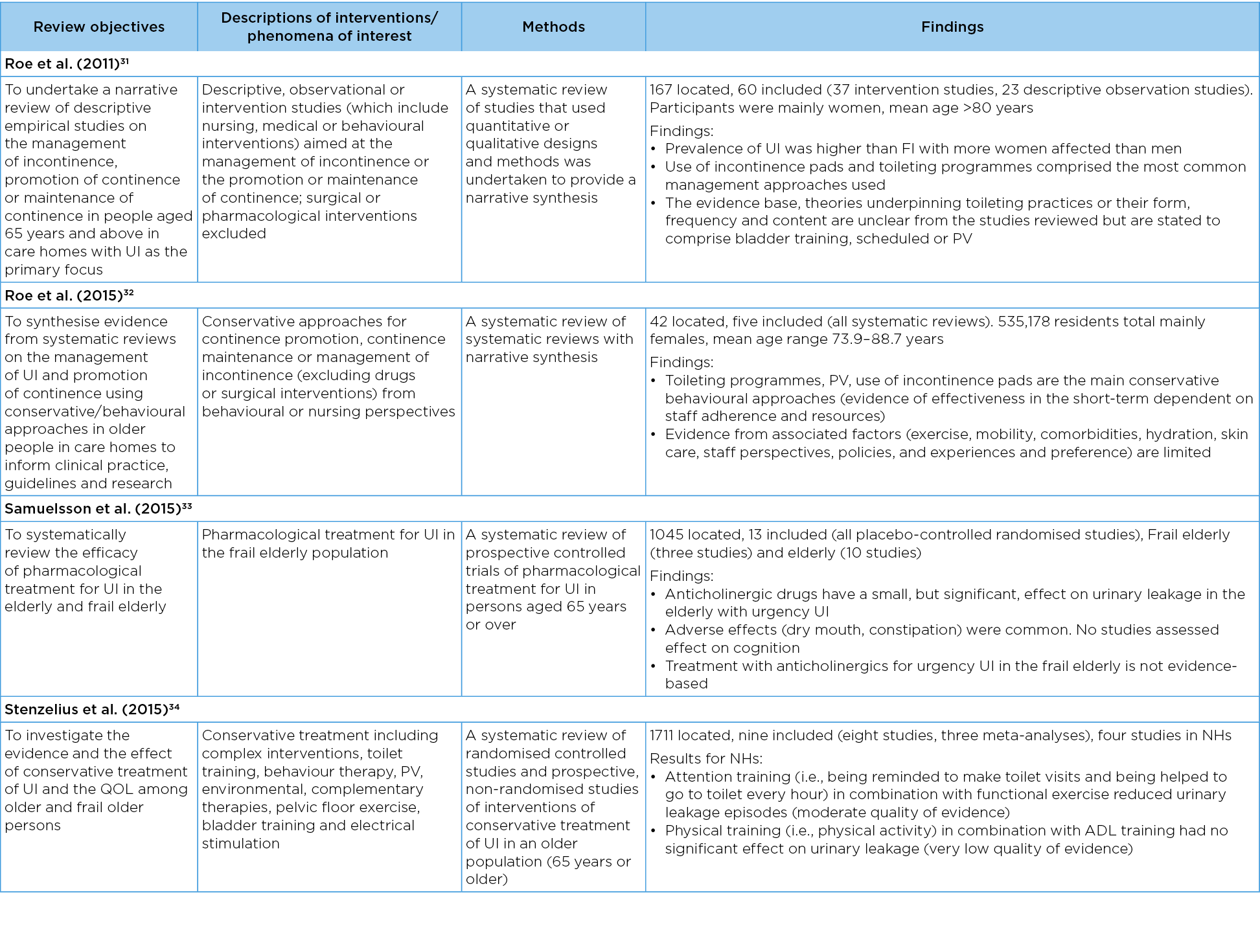

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies: systematic reviews

Legend for all tables:

NH: nursing home; UI: urinary incontinence; FI: faecal incontinence; IG: intervention group; CG: control group

NA: nursing assistant; CNA: certified nursing assistant; CNS: clinical nurse specialist; IF: internal facilitator; LPN: licensed practical nurse

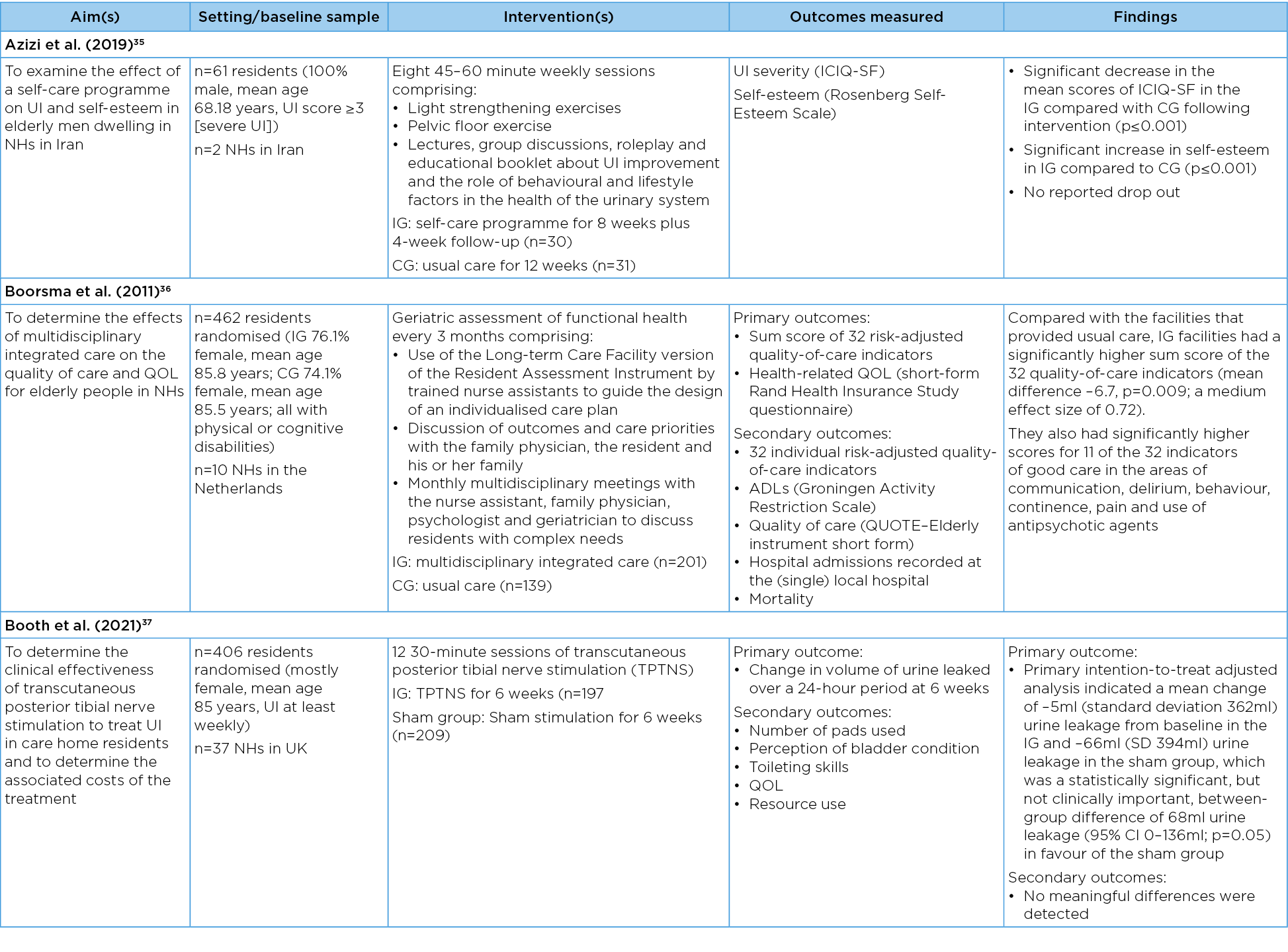

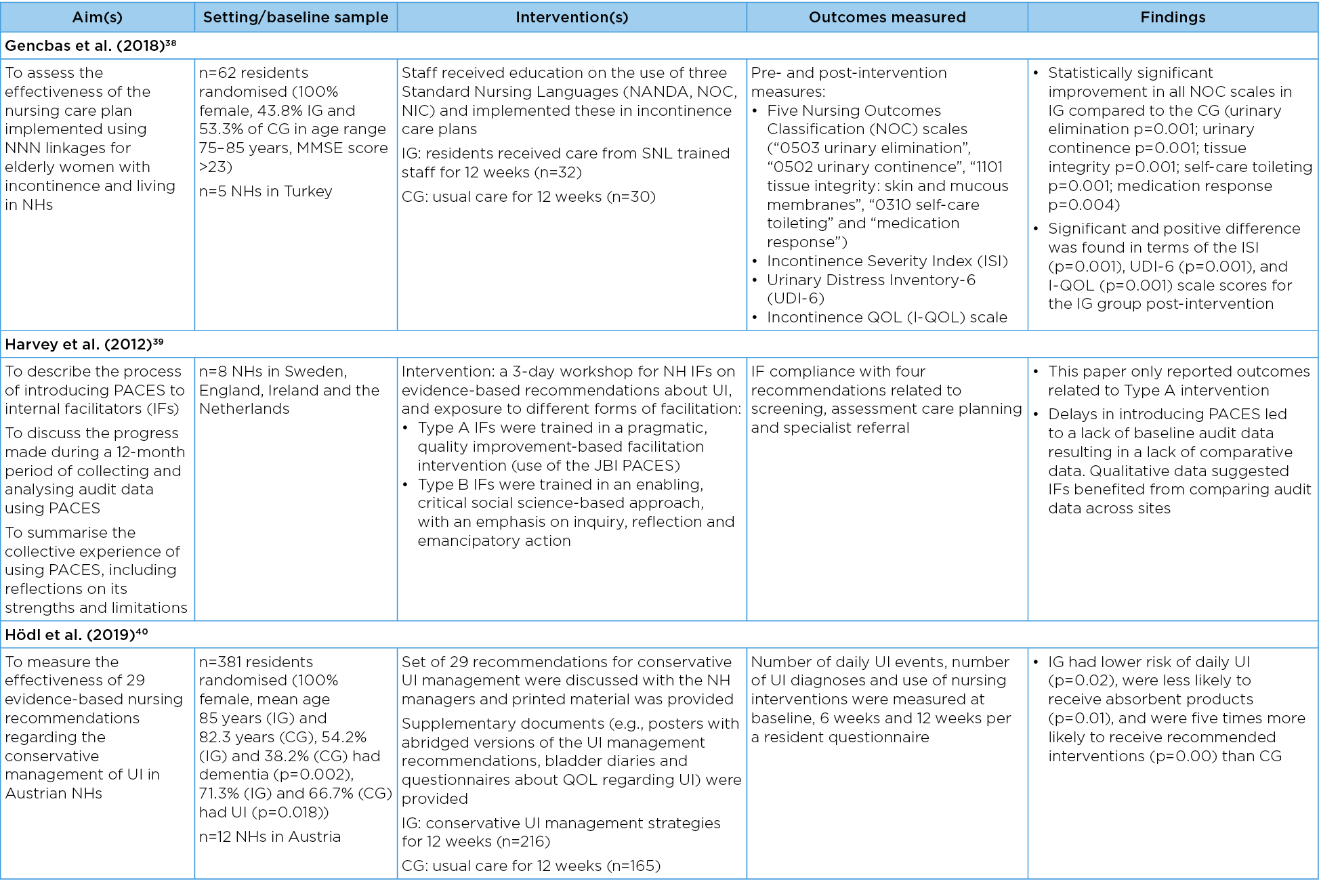

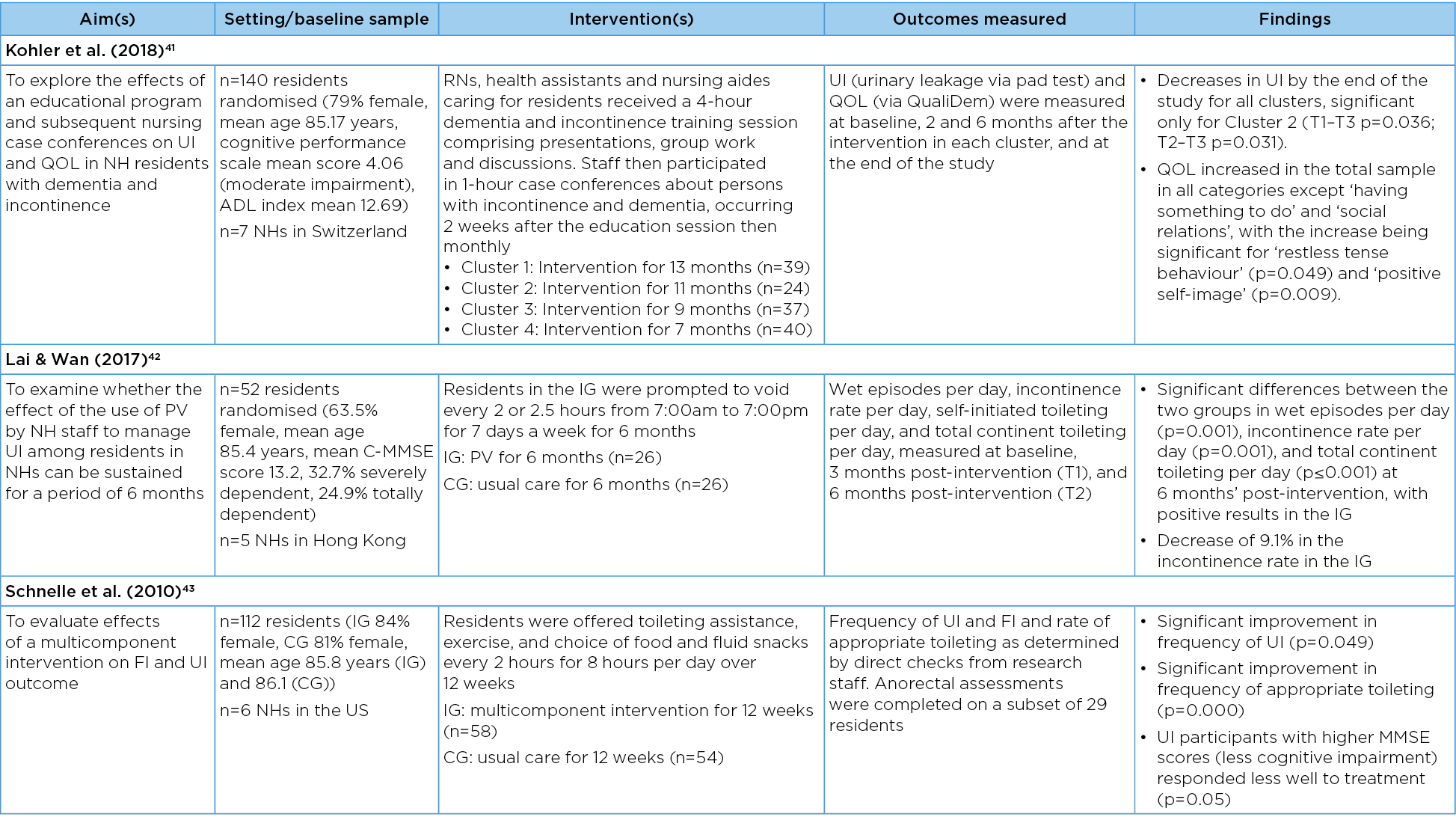

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies: RCTs

Table 4. Characteristics of included studies: quasi-experimental studies

Table 5. Characteristics of included studies: retrospective cohort studies

Toileting assistance programs

Systematic reviews from 201131, 201229 and 201532 reported moderate evidence that toileting assistance programs can reduce the frequency of UI in nursing homes, increase residents’ appropriate toileting behaviour, maintain their social continence, and regain continence. However, they also reported that the effects were short-term and dependent on staff resources and time32.

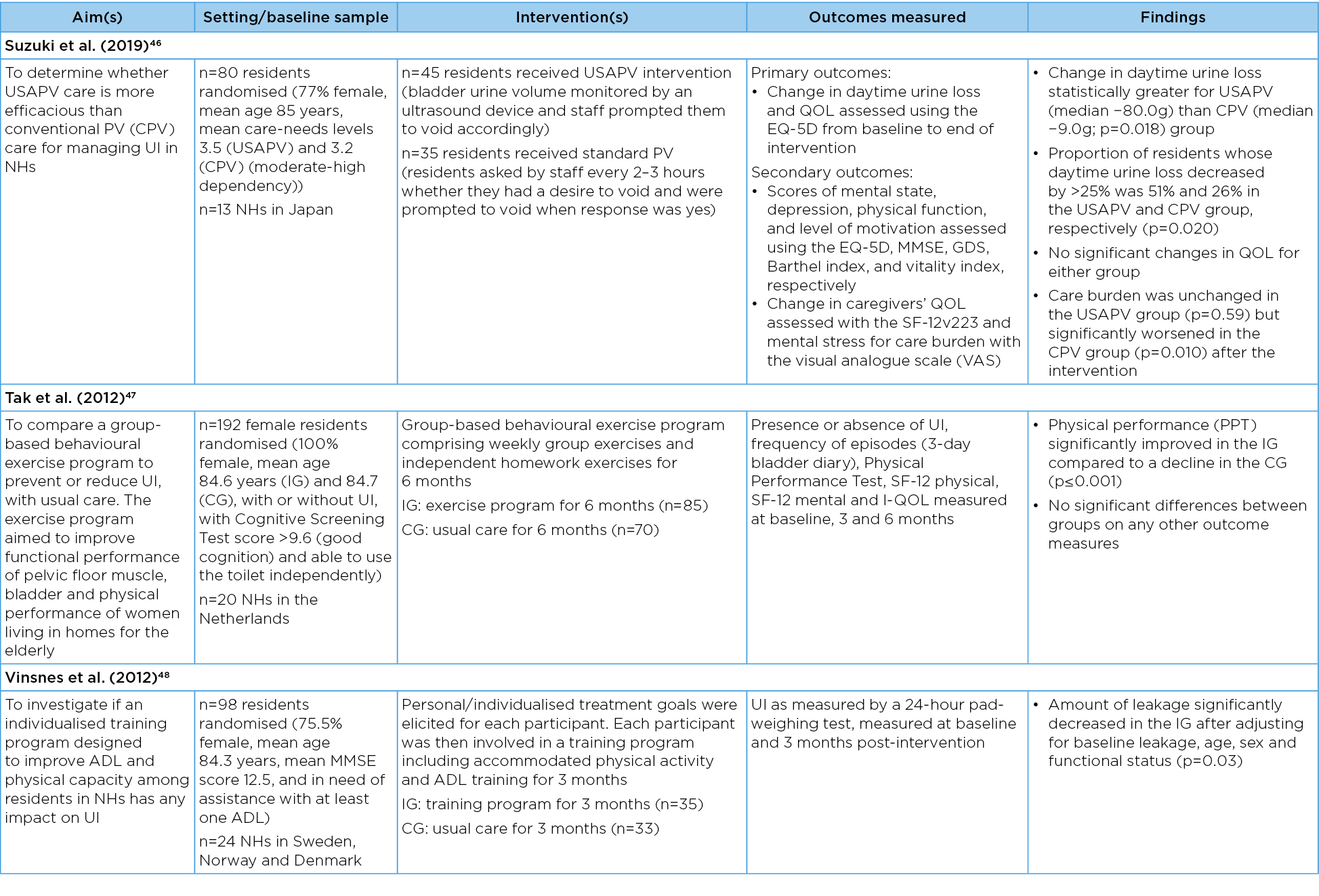

A further three studies suggest it is possible to implement toileting assistance programs in nursing homes over a longer period of time and with usual care staff. These include a RCT conducted by Lai and Wan42 that evaluated a 6-month, 2-hourly prompted voiding (PV) intervention implemented by usual care staff in 52 nursing home residents in five nursing homes in Hong Kong. The intervention was compared with usual care. The researchers reported a significant difference in wet episodes per day (p=0.001), UI rate per day (p=0.001), and total continent toileting per day (p≤0.001) with positive results in the intervention group. Using a quasi-experimental design, Suzuki et al.55 trialled PV for 1 week followed by ultrasound-assisted prompted voiding (USAPV) for 12 weeks in a cohort of 77 nursing homes residents in six nursing homes in Japan. The researchers reported an 11.8% reduction in the cost of incontinence products from baseline (p=0.006) and significant improvements in care workers’ QOL.

In 2019, the same authors conducted an RCT comparing PV alone with USAPV in 13 nursing homes with 125 residents over an 8-week period46. They reported a significant reduction in daytime UI for the USAPV group than for the PV group (p=0.018), with the proportion of residents whose daytime urine loss decreased by greater than 25% being 51% and 26% in the USAPV and PV group respectively (p=0.020). Furthermore, while carer burden was unchanged in the USAPV group, it significantly worsened in the PV group after the intervention (p=0.010).

Technology-based interventions

One randomised placebo-controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of a technology-based intervention, namely transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation37. A total of 12 30-minute sessions of this nerve stimulation were provided to 197 nursing home residents with UI over 6 weeks, while 209 residents were provided with sham stimulation. The researchers reported a statistically significant greater reduction in UI over 24 hours in the sham group in comparison to the treatment group (p=0.05). Therefore, this study did not demonstrate evidence that transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation is an effective intervention for UI.

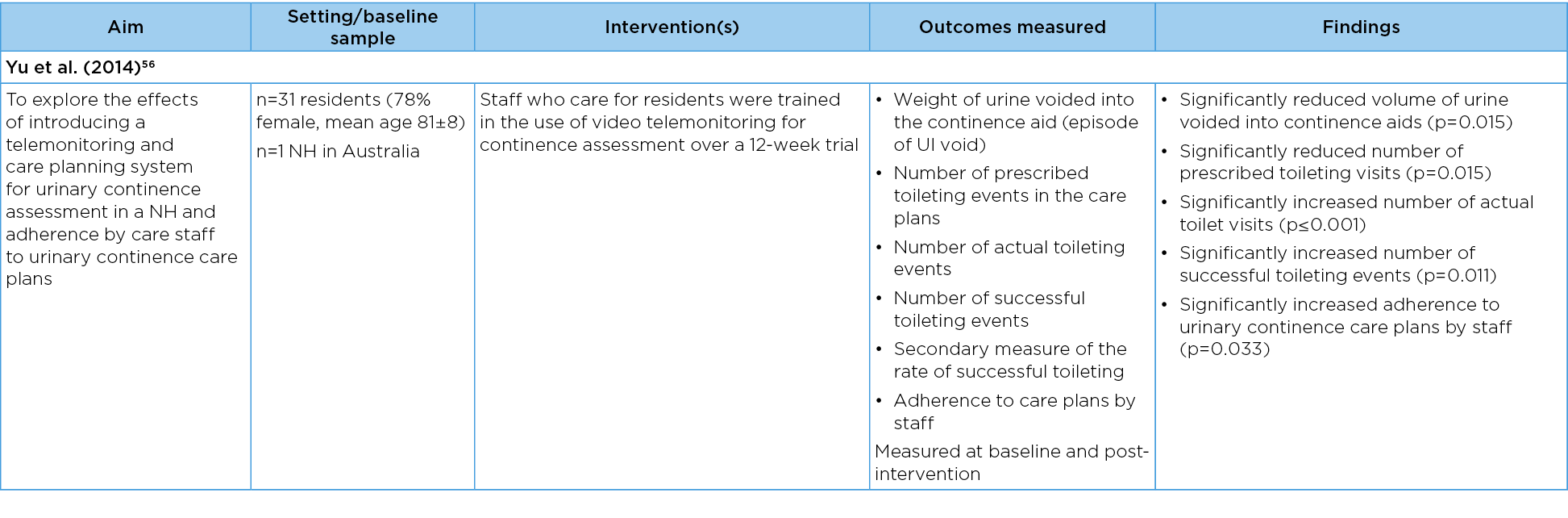

A quasi-experimental study by Yu et al.56 evaluated the effectiveness of a telemonitoring system. In this study, a sensor device was placed in residents’ incontinence products to detect the onset of wetness episodes in 31 residents over a 72-hour assessment period. The data obtained from the assessment was used to develop an individualised continence care plan for each resident. The researchers reported a significant reduction in the volume of urine voided into the pads (p=0.015), significant increases in the number of prescribed toileting visits (p=0.015), significant increases in the actual number of toilet visits (p≤0.001), successful toileting events (p=0.011), and in staff adherence to urinary continence care plans (p=0.033).

Exercise programs

In an RCT, Tak et al.47 evaluated the effects of a 6-month group-based behavioural exercise program on 102 female nursing home residents from 20 nursing homes in the Netherlands. Although physical performance significantly improved for the intervention group compared to the control group (p≤0.001), no significant differences were found for continence-related or QOL outcomes. In contrast, when personalised treatment goals were designed for each resident and physical activity and ADL training was implemented for 3 months, Vinsnes et al.48 reported a significant decrease in the amount of UI leakage among 35 nursing home residents in Norway (p=0.03). One systematic review reports exercise and functional incidental training programs reduced wetness rates and improved rates of appropriate toileting29. However, in a subsequent review, Stenzelius et al.34 reported a very low quality of evidence for physical activity in combination with ADL training in reducing UI.

Drug therapies

Two systematic reviews were identified that evaluated the use of drug therapies for the management of UI in nursing homes. In one review, anticholinergics showed a small but significant positive effect on urinary leakage in urge UI33. However, the review also found that adverse events, including dry mouth and constipation, were common, and studies on the impact of anticholinergics on cognition in this population have not yet been conducted. It was concluded that the use of anticholinergics for the treatment of urge UI in frail older people is not evidence-based. Flanagan et al.29 reported that the use of anticholinergics (oxybutynin) as an adjunct to toileting therapy may have benefits for the reduction of UI, but benefits appear to be inconsistent and may be small or non-existent.

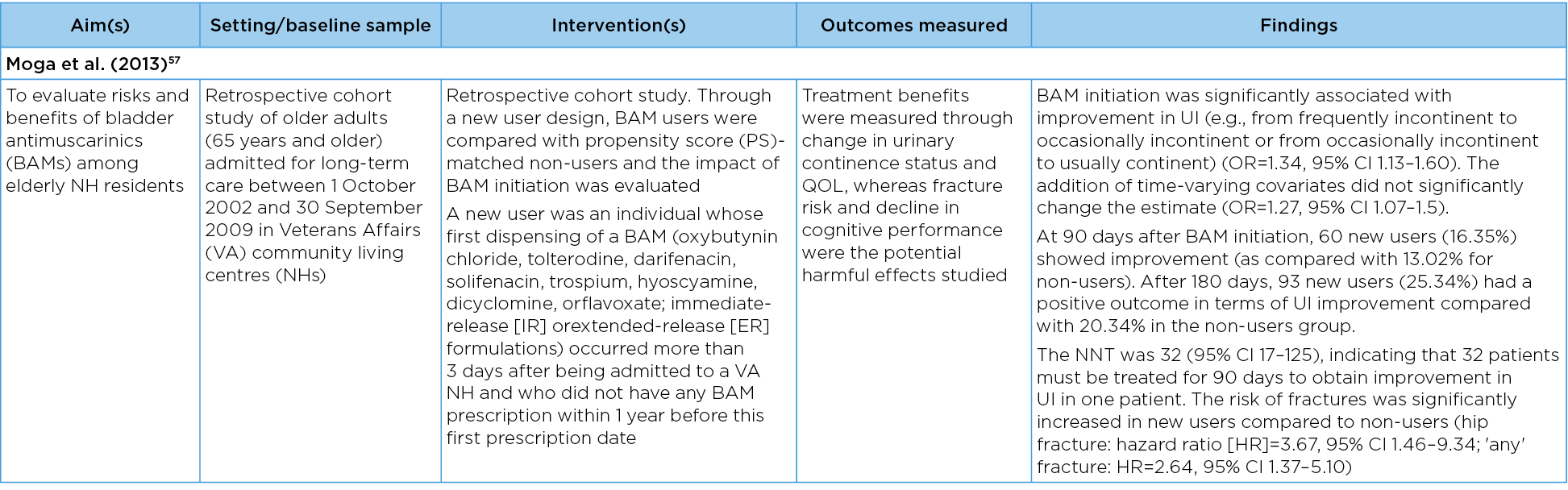

One cohort study also evaluated the use of drug therapies for the management of UI, namely bladder antimuscarinics (BAMs)57. Through new user design, BAM users were compared with propensity score (PS)-matched non-users, and the benefits (change in UI status and QOL) and harmful effects (fracture risk and decline in cognitive performance) of BAM initiation were evaluated. While BAM initiation was significantly associated with improvement in UI (OR=1.34, 95% CI 1.13–1.60), the risk of fractures was also significantly increased in new users compared to non-users (hip fracture: hazard ratio [HR]=3.67, 95% CI 1.46–9.34; 'any' fracture: HR=2.64, 95% CI 1.37–5.10) and there was no clinically significant improvement in social engagement among BAM users. It was concluded that non-selective immediate release BAMs (especially immediate-release oxybutynin chloride) should be approached cautiously as a treatment for UI amongst the nursing home population.

Education programs

Of the 11 publications that evaluated the effects of education programs for nursing home staff, seven were RCTS38–41,44,45,49 and four were quasi-experimental studies51–54. The nature of the educational interventions and the outcomes of interest varied considerably.

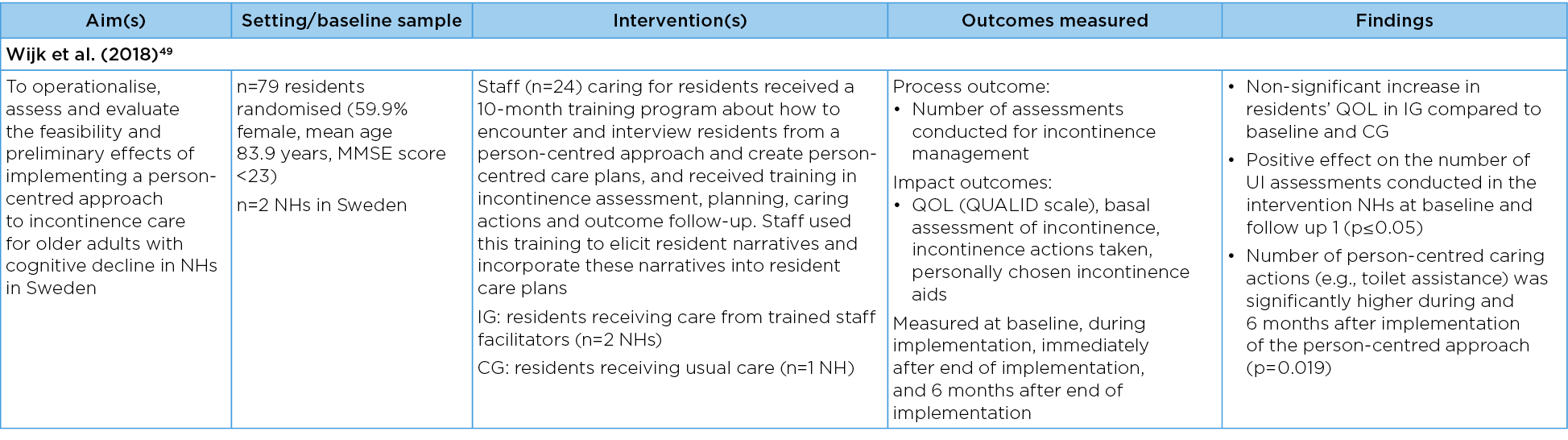

Over a 10-month period, Wijk et al.49 implemented an education program about a person-centred approach to continence care for nursing home staff from two nursing homes in Switzerland. Staff in the intervention group were educated on how to elicit information from residents about their personal identity and preferences and how to use this information to design an individualised continence care plans for each resident. In homes where the approach was used, the number of times residents received toileting assistance was significantly higher during and after the intervention compared to the control home (p=0.019). A significant positive effect was also found in the number of continence assessments conducted in the intervention homes (p≤0.05).

Also conducted in seven Swiss nursing homes over a 14-month period was a step wedge study led by Kohler et al.41. The intervention was a 4-hour education program focusing on continence care for residents living with dementia followed by six case conferences (one per month). The researchers found a decrease in UI for all groups which was only significant in the 11-month group (p=0.036). QOL also significantly increased in seven of the nine domains for residents in all groups.

In Austria, Hödl et al.40 conducted a cluster RCT in which managers from 12 nursing homes received and discussed 29 recommendations for the conservative management of UI. Three months later, residents in the intervention sites were found to have a significantly lower risk of daily UI (p=0.02), were less likely to receive absorbent products (p=0.01), and were five times more likely to receive the recommended interventions (p≤0.001) than those who received usual care.

Two further publications were identified, related to one large cluster RCT conducted across eight nursing homes in four European countries – Sweden, England, Ireland and the Netherlands39,45. The aim was to compare standard dissemination of evidence-based guidelines about UI with two different types of facilitation. The guidelines promoted: (i) screening for UI; (ii) a detailed continence assessment; (iii) an individualised treatment plan; and (iv) referral if needed. The researchers reported no between-group significant differences in the documented percentage compliance with the continence recommendations, which was assessed at baseline, and at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after the intervention and noted that all study arms improved over time. It was not possible to identify whether different forms of facilitation were influential within very diverse contextual conditions.

In the US, Schnelle et al.44 conducted a controlled trial to evaluate the effects of educating nursing home staff about offering residents greater choice about toileting assistance, exercise and choice of food and fluid snacks. They were encouraged to offer this choice every 2 hours for 8 hours per day over 3 months. At 3 months, the researchers reported significant increases in the number of time residents received choice-related toileting (p=0.014). However, they also noted a significant increase in the amount of staff time to provide care (p≤0.001).

Gencbas et al.38 evaluated the effects of educating nursing home staff on the use of a standardised nursing language to identify residents with UI and to design targeted nursing interventions in five nursing homes in Turkey. The cluster RCT conducted over 12 weeks was evaluated with respect to residents’ continence status and QOL. The researchers reported a between-group statistically significant improvement in the use of the standardised nursing language, residents’ QOL and symptom severity.

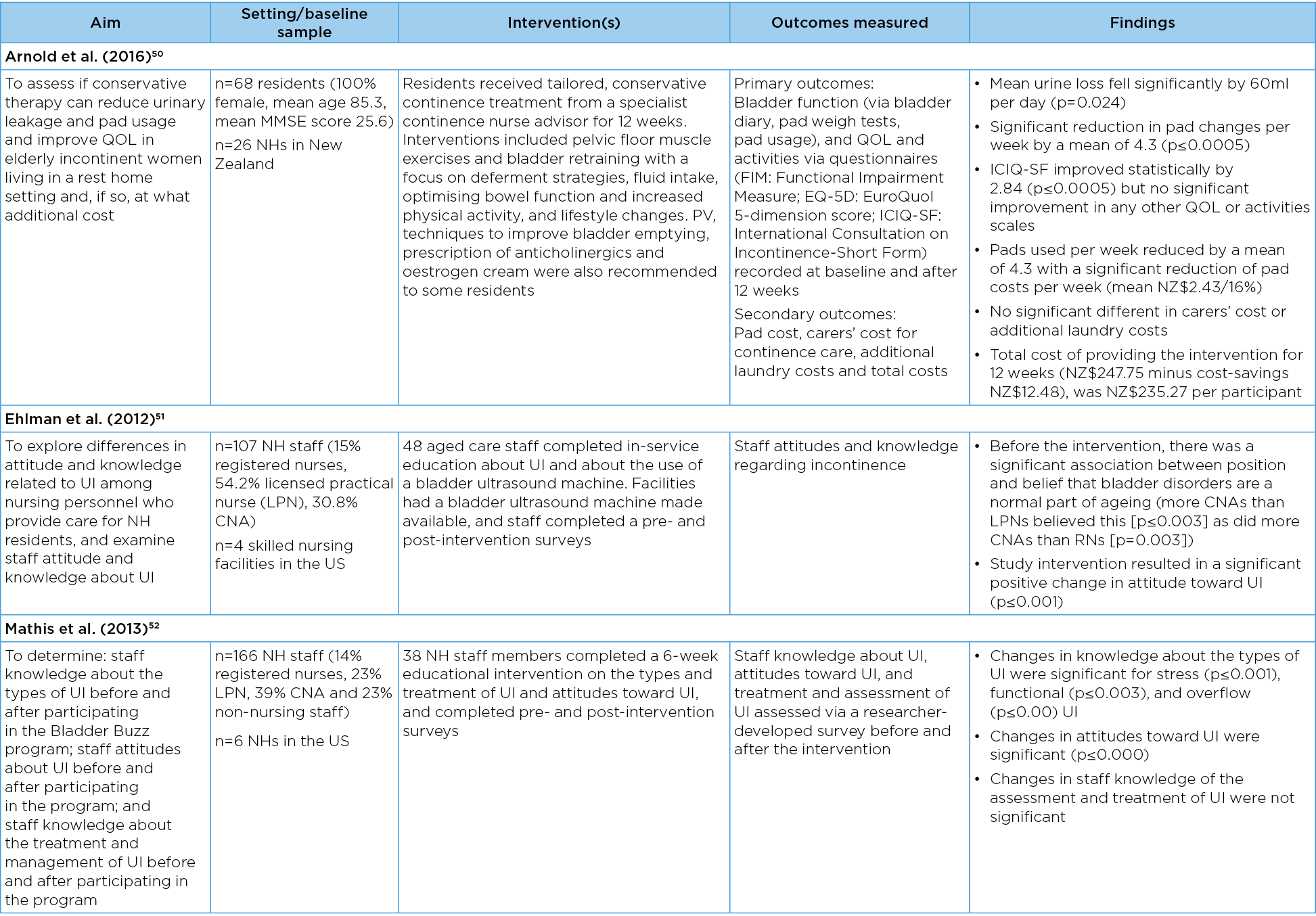

All four quasi-experimental studies that examined the effects of educating nursing home staff about UI were conducted in the US51–54. They included a 6-week pre/post-study by Mathis et al.52 involving 166 nursing home staff from six US nursing homes. The education focussed on the types and treatment of incontinence and was delivered face-to-face. The researchers reported significant improvements in post-education staff knowledge about types of UI (p≤0.001 for all domains) and improved attitudes about UI (p≤0.001), but no significant change in staff knowledge about assessment or treatment.

By contrast, Ehlman et al.51 reported significant improvements in nursing home staff members’ attitudes about UI following nine in-service programs designed to teach 107 staff from four skilled nursing facilities in the US how to use a bladder scanner. This was augmented with a DVD on the same topic, a refresher in-service 12 weeks later, and supplementary information and incentives. Post-intervention improvements were also noted for knowledge about using a bladder scanner, but not for the belief that UI is a normal part of ageing.

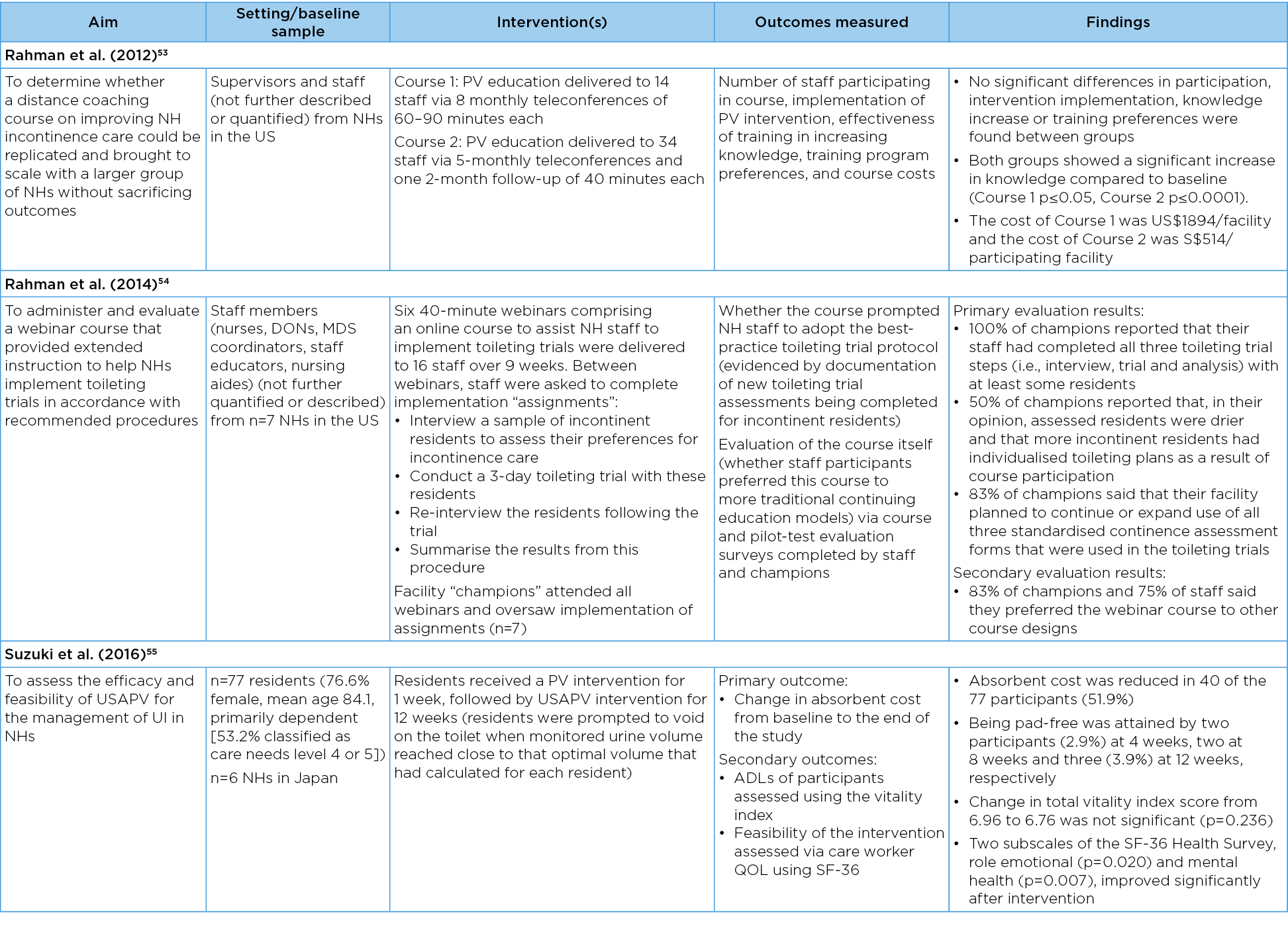

Rahman et al.53,54 compared a 5-month course about PV delivered by teleconference with an 8-month course. The researchers reported a significant increase in nursing home staff knowledge compared to baseline (p≤0.05 and p≤0.001) and that varying the number and duration of teleconference sessions did not produce any significant effects. The researchers also evaluated the effects of six 40-minute webinars on the same topic54. Based on nursing home documentation, 100% of participating homes implemented toileting assistance following the education and 83% reported that they planned to continue the intervention.

Multi-component interventions

Multi-component interventions that combine physical activity with other interventions can reduce UI in nursing homes according to the findings of a systematic review29. In addition, two RCTs demonstrated the effectiveness of multi-component interventions that combine physical activity with other interventions. A trial by Schnelle et al.43 evaluated exercise in combination with toileting assistance and choice of food and fluid snacks every 2 hours for 8 hours per day over 12 weeks. Compared to controls (n=60), residents (n=65) who received this multi-component intervention had a significant reduction in the frequency of UI (p=0.049) and an improvement in the frequency of appropriate toileting (p≤0.001). Azizi et al.35 compared the effectiveness of an 8-week multi-component program (light strengthening exercises, pelvic floor exercises, and an education program about UI with usual care). Residents (n=30) who participated in the program showed a significant decrease in UI severity (p≤0.001).

An additional three publications described the effect of multi-component interventions, albeit specifically focussing on the role of specialist healthcare professionals. They were a systematic review28, a cluster RCT36 and a quasi-experimental study50. The systematic review reported on four studies in which a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) facilitated evidence-based protocols, collaborated with staff, and provided staff education, consultation and direct care to residents for 6 months post-admission28. Residents in nursing homes who received these interventions showed reduced UI or slowed decline in UI28. This finding is further supported by a subsequent quasi-experimental study involving 68 nursing home residents who received tailored, conservative continence treatment from a continence nurse advisor for 12 weeks50. A variety of strategies were implemented for each resident. After implementation, mean urine loss fell significantly by 60ml per day (p=0.024) and a significant reduction in pad changes per week by a mean of 4.3 (p≤0.0005) was observed. Incontinence-related QOL scores improved significantly (p≤0.005) but there was no significant improvement in any other QOL or activities scale measured.

In the cluster RCT, Boorsma et al.36 compared a multidisciplinary integrated care program with usual care in 10 nursing homes in the Netherlands. The program comprised assessments, individualised care plans, discussions between the family physician, resident and their family, and multidisciplinary staff meetings to discuss residents with complex needs. Each component of the program was repeated quarterly for the duration of the study. Compared with the facilities that provided usual care, intervention facilities had a significantly higher sum score of 32 quality of care indicators and significantly higher scores for 11 of 32 indicators of good care, including UI.

Dicussion

This scoping review was undertaken to map and summarise evidence about interventions for the management of UI in nursing homes. We identified several different intervention types and grouped them according to whether they represented a toileting assistance program, an exercise program, drug therapy, a technology-based intervention, an education program, or a multi-component intervention.

We identified six publications about toileting assistance programs, namely PV — three systematic reviews29,31,32, two RCTs42,46 and one quasi-experimental study55. The latter three studies provide recent evidence to support the use of technology to augment assessment processes and for the implementation and sustainability of PV by usual care staff. The use of ultrasound technology to identify when nursing home residents need to void is a relatively new innovation for the management of incontinence in nursing homes, as is the use of sensor alarms. The technology is based on the observation that some nursing home residents’ have predictable voiding patterns and that, by identifying the pattern, staff will be better placed to provide targeted and timely assistance. As the technology can provide more accurate and objective information about a person’s actual bladder function, they can augment current assessment processes and thereby minimise trial and error. However, important questions remain about the transferability of the findings to different cultural contexts, staff training needs and costs as well as residents’ acceptance of the technology. It is important to understand the relationship between the effectiveness of technological interventions in nursing homes, the provision of staff or carer training and support, and the process of fidelity to the intervention.

Recent evidence also points to the need to optimise nursing home residents’ functional skills and mobility11. Despite this, only two studies specifically described an evaluation of an exercise program, and the findings were inconsistent. The best evidence is for multi-component interventions that combine physical activity programs with systematic efforts to improve residents’ choice, food and fluid intake, and access to toileting assistance. Again, studies point to the value of engaging advanced practice registered nurses to facilitate this approach.

This scoping review found limited evidence about the use of drug therapies for the management of UI in nursing homes. Based on two systematic reviews and a cohort study, the benefits of using anticholinergics are outweighed by the risks of adverse effects. It is also clear that, although acceptable, transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation is unlikely to confer a reduction in UI in nursing homes with a high proportion of older frail residents with reduced cognitive capacity.

Staff education was the focus of 11 publications. Prior research points to gaps in undergraduate education programs for healthcare practitioners in the UK58 and in the US59. A recent review of the effects of UI education for nurses and nursing assistants' knowledge, attitudes and self-reported practices found education improved knowledge, but the most effective forms of education that affects practice and patient outcomes are not known30.

Nursing home staff should be educated on best practice guidelines. The findings from a large cluster RCT reported by Harvey et al.39 and Seers et al.45 highlight the complexities of implementing and evaluating guidelines in nursing homes, even when it is facilitated. The researchers found no significant differences between groups in the documented percentage compliance with the continence recommendations. There could be several reasons for this finding, including limitations of the guidelines themselves. Many guidelines about incontinence are underpinned by the medical goal of diagnosis and treatment. We argue that guidelines and education programs about continence care should place equal value on helping people adjust to changes in bodily function that affect their identity, autonomy, control and independence.

Contemporary forms of education about care in health and social care systems promote person-centred care facilitated through a shared-decision making process60–62. This highlights the importance of the intervention implemented and evaluated by Wijk et al.49 where nursing home staff were educated on how to elicit information from residents about their personal identity and preferences and to then use this information to design individualised continence care plans. It should be noted that introducing a person-centred approach to continence care takes time and commitment and may require a culture change for some nursing homes.

Given the high proportion of residents with a diagnosis of dementia in nursing homes, education programs for staff should also address the prevention and management of incontinence in people with dementia. The education program described by Kohler et al.41 is an important exemplar. The program addressed dementia as well as incontinence and was augmented with case conferences for staff to discuss problematic and challenging situations concerning specific nursing home residents. Our analysis of education interventions also points to the need for direct hands-on education combined with on-site support and competency-based learning approaches, particularly when led by specialist healthcare professionals.

Two studies provide evidence that organisational structures, staff resources, staffing models and care processes impact on nursing home residents’ risk of incontinence63,64. Work environment attributes such as team cohesiveness, consistent assignment and staff cohesion affect residents’ urinary continence status63. Within this context, higher registered nurse to patient ratios is an important consideration. A longitudinal correlational study on the impact of organisational factors on the continence status of patients in Korean long-term care hospitals found higher registered nurse to patient ratios was significantly associated with better resident continence status64. These key findings highlight the important role that registered nurses and nursing home leaders have in creating a therapeutic physical and socio-cultural environment that facilitates continence.

Based on one study and a systematic review, we also recommend multicomponent interventions delivered by registered nurses with advanced practice skills28,50 and for multidisciplinary integrated care36. Ideally, the multicomponent intervention should consist of assessments, individualised care plans, discussions between the family physician, residents and their families, and multidisciplinary staff meetings to discuss residents with complex needs.

Strengths and limitations

A weakness of this scoping review was that we did not develop and register an a priori protocol and thus the review does not fully adhere to the JBI reviewers’ manual 2015 methodology for JBI scoping reviews25, nor the PRISMA-ScR guidelines26. At the same time, a key strength of this scoping review is that the broad nature of the design yielded evidence about several types of interventions for the management of UI in nursing homes.

The review was limited to research with quantitative findings. As such, it focussed on questions of effectiveness rather than context. Further reviews are required to summarise qualitative research about the psychological and sociological aspects of UI in nursing homes.

Finally, nursing homes vary considerably, both within and between countries. Therefore, interventions that are effective in one context may not be effective in another. Aligned with this consideration is the cultural bias in the body of evidence. Most of the research identified was conducted in Western countries and none from lower to middle income countries. Of the 30 studies identified, 18 were conducted in nursing homes in Western countries. Hence, the transferability to non-Western and lower to middle income countries should be considered. Further research is also needed to understand whether existing UI management strategies are able to meet the specific needs of residents from diverse backgrounds, such residents from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, First Nations residents, and residents who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and/or intersex (LGBTIQA+).

Finally, while each study was appraised, studies were not excluded from the review based on their quality. Moreover, findings were reported descriptively and were not subject to rigorous assessment, taking potential biases into account. In several of the studies unblinding may have introduced significant bias; however, given the nature of some of the interventions (ie, personalised therapies, physical activity programs and workshops), unblinding may be acceptable in this context.

Conclusion

UI continues to be a pervasive problem that disproportionately affects people in nursing homes. Interventions to maintain or improve nursing home residents’ functional status and reduce their care dependence should be prioritised. Improvements in staff knowledge, attitudes and continence care practices in nursing homes are possible, particularly when led by specialist healthcare professionals.

This scoping review suggests a multi-component approach to care offers most benefit, ie, where efforts are made to increase residents’ activity level, nutritional status, hydration and opportunity to use the toilet. This approach should also be combined with direct forms of education for staff to optimise compliance. Future directions for policy should promote person-centred continence care, comprehensive multi-disciplinary assessments, and a well-educated and supported workforce. Registered nurses play a key role in creating a therapeutic physical and socio-cultural environment that facilitates continence in nursing homes.

Author contributions

All of the authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. They were all involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgements

The researchers wish to acknowledge input to the research study by Ms Erica Wise and Dr Stephanie Garratt.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The scoping review was funded by the Continence Foundation of Australia as part of a research study to develop a best practice model of continence care for residential aged care homes in Australia.

Author(s)

Joan Ostaszkiewicz*

National Ageing Research Institute, VIC, Australia

Federation University, Health and Innovation Transformation Centre, VIC, Australia

University of Melbourne, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, VIC, Australia

Leona Kosowicz

National Ageing Research Institute, VIC, Australia

Jess Cecil

National Ageing Research Institute, VIC, Australia

Deidree Somanader

Monash University, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, VIC, Australia

Briony Dow

National Ageing Research Institute, VIC, Australia

University of Melbourne, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, VIC, Australia

*Corresponding author

References

- Wagg A, Bower W, Gibson W, Kirschner-Hermanns R, Hunter K, Kuchel GA, Morris V, Ostaszkiewicz J, Suskind A, Suzuki M, Wyman J. Incontinence in frail older adults. In: Cardozo L, Rovner E, Wagg A, Wein A, Abrams P, editors. Incontinence: 7th international consultation on incontinence, vol 13. London: ICUD ICS; 2023.

- Boyington JE, Howard DL, Carter-Edwards L, Gooden KM, Erdem N, Jallah Y, Busby-Whitehead J. Differences in resident characteristics and prevalence of urinary incontinence in nursing homes in the southeastern United States. Nurs Res 2007;56(2):97–107.

- Jachan DE, Müller-Werdan U, Lahmann NA. Impaired mobility and urinary incontinence in nursing home residents: a multicenter study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(6):524–529.

- Harrison T, Blozis S, Manning A, Dionne-Vahalik M, Mead S. Quality of care to nursing home residents with incontinence. Geriatr Nurs 2019;40(2):166–173.

- Mandl M, Halfens RJ, Lohrmann C. Interactions of factors and profiles of incontinent nursing home residents and hospital patients: a classification tree analysis. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):407–413.

- Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry: executive summary. Staffordshire: Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust; 2013. Available from: http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/sites/default/files/report/Executive%20summary.pdf

- The Royal Commission into Quality and Safety in Aged Care. Final report: care dignity and respect. Canberra: Royal Commission into Quality and Safety in Aged Care; 2021. Available from: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/final-report

- Ostaszkiewicz J, Tomlinson E, Hutchinson A. ‘Dignity’: a central construct in nursing home staff understandings of quality continence care. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:2425–2437.

- Ostaszkiewicz J, Tomlinson C, Hutchinson A. Learning to accept incontinence and continence care in residential aged care facilities: family members’ experiences. Aust NZ Cont J 2016; 22(3):14–21.

- MacDonald CD, Butler L. Silent no more: elderly women’s stories of living with urinary incontinence in long-term care. J Gerontolog Nurs 2007;33(1):14–20.

- Li HC, Chen KM, Hsu HF. Modelling factors of urinary incontinence in institutional older adults with dementia. J Clin Nurs 2019;28(23–24):4504–4512.

- Watson NM, Brink CA, Zimmer JG, Mayer RD. Use of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Urinary Incontinence Guideline in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(12):1779–1786.

- Xu D, Kane RL. Effect of urinary incontinence on older nursing home residents’ self-reported quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61(9):1473–1481.

- Jerez-Roig J, Moreira FSM, da Câmara SMA, Ferreira LMBM, Lima KC. Predicting continence decline in institutionalized older people: a longitudinal analysis. Neurourol Urodyn 2019;38(3):958–967.

- Van Damme N, Van den Bussche K, De Meyer D, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S, Beeckman D. Independent risk factors for the development of skin erosion due to incontinence (incontinence-associated dermatitis category 2) in nursing home residents: results from a multivariate binary regression analysis. Int Wound J 2017;14(5):801–810.

- Hasegawa J, Kuzuya M, Iguchi A. Urinary incontinence and behavioural symptoms are independent risk factors for recurrent and injurious falls, respectively, among residents in long-term care facilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010;50(1):77–81.

- Moon S, Hong GS. Predictive factors of mortality in older adult residents of long-term care facilities. J Nurs Res 2020;28(2):e82.

- Frantz RA, Xakellis Jr GC, Harvey PC, Lewis AR. Implementing an incontinence management protocol in long-term care: clinical outcomes and costs. J Gerontolog Nurs 2003;29(8):46–53.

- Schnelle JF. Treatment of urinary incontinence in nursing home patients by prompted voiding. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:356–360.

- Schnelle JF, Newman DR, Fogarty TE, Wallston K, Ory M. Assessment and quality control of incontinence care in long term nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;36:165–71.

- Schnelle JF, Newman D, White M, Abbey J, Wallston KA, Fogarty T, Ory MG. Maintaining continence in nursing home residents through the application of industrial quality control. Gerontologist 1993;33:114–121.

- Schnelle JF, MacRae PG, Ouslander JG, Simmons SF, Nitta M. Functional incidental training, mobility performance, and incontinence care with nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43(12):1356–62.

- Schnelle JF, Alessi CA, Simmons SF, Al-Samarrai NR, Beck JC, Ouslander JG. Translating clinical research into practice: a randomized controlled trial of exercise and incontinence care with nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1476–1483.

- Eustice S, Roe B, Paterson J. Prompted voiding for the management of urinary incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database System Rev 2000;(2), CD002113.

- Peters M, Godfrey C, Mclnernery P, Soares CB, Khalilm H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annal Int Med 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, Hartmann-Boyce J, Ryan R, Shepperd S, Thomas J, Welch V, Thomson H. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. Br Med J 2020;368:l6890.

- Donald F, Martin-Misener R, Carter N, Donald EE, Kaasalainen S, Wickson-Griffiths A, Lloyd M, Akhtar-Danesh N, DiCenso A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of advanced practice nurses in long-term care. J Adv Nurs 2013;69(10):2148–2161.

- Flanagan L, Roe B, Jack B, Barrett J, Chung A, Shaw C, Williams KS. Systematic review of care intervention studies for the management of incontinence and promotion of continence in older people in care homes with urinary incontinence as the primary focus (1966–2010). Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012 Oct;12(4):600–11.

- Ostaszkiewicz J, Tomlinson E, Hunter K. The effects of education about urinary incontinence on nurses’ and nursing assistants’ knowledge, attitudes, continence care practices and patient outcomes. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2020;47(4):365–380.

- Roe B, Flanagan L, Jack B, Barrett J, Chung A, Shaw C, Williams K. Systematic review of the management of incontinence and promotion of continence in older people in care homes: descriptive studies with urinary incontinence as primary focus. J Adv Nurs 2011;67(2):228–250.

- Roe B, Flanagan L, Maden M. Systematic review of systematic reviews for the management of urinary incontinence and promotion of continence using conservative behavioural approaches in older people in care homes. J Adv Nurs 2015;71(7):1464–1483.

- Samuelsson E, Odeberg J, Stenzelius K, Molander U, Hammarström M, Franzen K, Andersson G, Midlöv P. Effect of pharmacological treatment for urinary incontinence in the elderly and frail elderly: a systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15(5):521–534.

- Stenzelius K, Molander U, Odeberg J, Hammarström M, Franzen K, Midlöv P, Samuelsson E, Andersson G. The effect of conservative treatment of urinary incontinence among older and frail older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2015;44(5):736–744.

- Azizi M, Azadi A, Otaghi M. The effect of a self-care programme on urinary incontinence and self-esteem in elderly men dwelling in nursing homes in Iran. Aging Male 2020;23(5):687–693.

- Boorsma M, Frijters DH, Knol DL, Ribbe ME, Nijpels G, van Hout HP. Effects of multidisciplinary integrated care on quality of care in residential care facilities for elderly people: a cluster randomized trial. Can Med Assoc J 2011;183(11):E724–E732.

- Booth J, Aucott L, Cotton S, Davis B, Fenocchi L, Goodman C, Hagen S, Harari D, Lawrence M, Lowndes A, Macaulay L, MacLennan G, Mason H, McClurg D, Norrie J, Norton C, O’Dolan C, Skelton D, Surr C, Treweek S. Tibial nerve stimulation compared with sham to reduce incontinence in care home residents: ELECTRIC RCT. Health Technol Assess 2021;25(41):1–110.

- Gencbas D, Bebis H, Cicek H. Evaluation of the efficiency of the nursing care plan applied using NANDA, NOC, and NIC linkages to elderly women with incontinence living in a nursing home: a randomized controlled study. Int J Nurs Know 2018;29(4):217–226.

- Harvey G, Kitson A, Munn Z. Promoting continence in nursing homes in four European countries: the use of PACES as a mechanism for improving the uptake of evidence-based recommendations. Int J Evid-based Health 2012;10(4):388–396.

- Hödl M, Halfens RJG, Lohrmann C. Effectiveness of conservative urinary incontinence management among female nursing home residents: a cluster RCT. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2019;81:245–251.

- Kohler M, Schwarz J, Burgstaller M, Saxer S. Incontinence in nursing home residents with dementia: influence of an educational program and nursing case conferences. Gerontologie und Geriatrie 2018;51(1):48–53.

- Lai CKY, Wan X. Using prompted voiding to manage urinary incontinence in nursing homes: can it be sustained? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18(6):509–514.

- Schnelle JF, Leung FW, Rao, SS, Beuscher L, Keeler E, Clift JW, Simmons S. A controlled trial of an intervention to improve urinary and faecal incontinence and constipation. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(8):1504–1511.

- Schnelle JF, Rahman A, Durkin DW, Beuscher L, Choi L, Simmons SF. A controlled trial of an intervention to increase resident choice in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14(5):345–351.

- Seers K, Rycroft-Malone J, Cox K, Crichton N, Edwards RT, Eldh AC, Estabrooks CA, Harvey G, Hawkes C, Jones C, Kitson A, McCormack B, McMullan C, Mockford C, Niessen, T, Slater P, Titchen A, van der Zijpp T, Wallin L. Facilitating Implementation of Research Evidence (FIRE): an international cluster randomised controlled trial to evaluate two models of facilitation informed by the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci 2018;13(1):137.

- Suzuki M, Miyazaki H, Kamei J, Yoshida M, Taniguchi T, Nishimura K, Igawa Y, Sanada H, Homma Y. Ultrasound-assisted prompted voiding care for managing urinary incontinence in nursing homes: a randomized clinical trial. Neurourol Urodyn 2019;38(2):757–763.

- Tak EC, van Hespen A, van Dommelen P, Hopman-Rock M. Does improved functional performance help to reduce urinary incontinence in institutionalized older women? a multicenter randomized clinical trial. BMC Geriatr 2012;12:51.

- Vinsnes AG, Helbostad JL, Nyrønning S, Harkless GE, Granbo R, Seim A. Effect of physical training on urinary incontinence: a randomized parallel group trial in nursing homes. Clin Intervent Aging 2012;7:45–50.

- Wijk H, Corazzini K, Kjellberg IL, Kinnander A, Alexiou E, Swedberg K. Person-centered incontinence care in residential care facilities for older adults with cognitive decline: feasibility and preliminary effects on quality of life and quality of care. J Gerontol Nurs 2018;44(11):10–19.

- Arnold EP, Milne DJ, English S. Conservative treatment for incontinence in women in rest home care in Christchurch: outcomes and cost. Neurol Urodyn 2015;35(5):636–641.

- Ehlman K, Wilson A, Dugger R, Eggleston B, Coudret N, Mathis S. Nursing home staff members’ attitudes and knowledge about urinary incontinence: the impact of technology and training. Urolog Nurs 2012;32(4):205–213.

- Mathis S, Ehlman K, Dugger BR, Harrawood A, Kraft CM. Bladder Buzz: the effect of a 6-week evidence-based staff education program on knowledge and attitudes regarding urinary incontinence in a nursing home. J Contin Ed Nurs 2013;44(11):498–506.

- Rahman AN, Schnelle JF, Applebaum R, Lindabury K, Simmons S. Distance coursework and coaching to improve nursing home incontinence care: lessons learned. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(6):1157–1164.

- Rahman AN, Schnelle JF, Osterweil D. Implementing toileting trials in nursing homes: evaluation of a dissemination strategy. Geriatr Nurs 2014;35(4):283–289.

- Suzuki M, Iguchi Y, Igawa Y, Yoshida M, Sanada H, Miyazaki H, Homma Y. Ultrasound-assisted prompted voiding for management of urinary incontinence of nursing home residents: efficacy and feasibility. Int J Urol 2016;23(9):786–790.

- Yu P, Hailey D, Fleming R, Traynor V. An exploration of the effects of introducing a telemonitoring system for continence assessment in a nursing home. J Clin Nurs 2014;23(21–22):3069–3076.

- Moga DC, Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Pendergast JF, Wallace RB, Torner JC, Li Y, Chrischilles EA. Risks and benefits of bladder antimuscarinics among elderly residents of Veterans Affairs community living centers. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14(10):749–760.

- McClurg D, Cheater FM, Eustice S, Burke J, Jamieson K, Hagen S. A multi-professional UK wide survey of undergraduate continence education. Neurourol Urodyn 2013;32(3):224–229.

- Morishita L, Uman GC, Pierson CA. Education on adult urinary incontinence in nursing school curricula: can it be done in two hours? Nurs Outlook 1994;42(3):123–129.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Patient-centred care – improving quality and safety through partnerships with patients and consumers. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare; 2011. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/patient-centred-care-improving-quality-and-safety-through-partnerships-patients-and-consumers

- Care Quality Commission. Regulation 9: person-centred care. UK: Care Quality Commission; 2022. Available from: https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/regulations-enforcement/regulation-9-person-centred-care

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academy Press (US); 2001.

- Temkin-Greener H, Cai S, Zheng NT, Zhao H, Mukamel DB. Nursing home work environment and the risk of pressure ulcers and incontinence. Health Serv Res 2012;47:1179–200.

- Yoon JY, Lee YJ, Bowers BJ, Zimmerman DR. The impact of organizational factors on the urinary incontinence care quality in long-term care hospitals: a longitudinal correlational study. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49(12):1544–51.