Volume 29 Number 3

The experience of six women living with pelvic surgical mesh complications – interventions and adaptions: a phenomenological inquiry

Jacqueline L Tuffnell

Licensed under CC BY 4.0

Keywords surgical mesh, restorative, mesh complications

For referencing Tuffnell JL. The experience of six women living with pelvic surgical mesh complications – interventions and adaptions: a phenomenological inquiry. Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal 2023; 29(3):59-66.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/anzcj.29.3.59-66

Submitted 17 April 2023

Accepted 7 August 2023

Abstract

This study follows up six women from a 2018 study examining the experience of women living with pelvic surgical mesh complications. Qualitative research relating to women’s experience of treatment for mesh complications is limited. Participants had subsequently undergone surgical and non-surgical interventions for their complications. The aim of the current study was to understand the lived experience of these interventions and establish the impact of these interventions on participants’ quality of life and wellbeing.

Hermeneutic phenomenology was used with thematic analysis linking findings back to Van Manen’s four lifeworld existentials used in the 2018 study – lived space, lived body, lived time and lived other. Participants completed a repeat International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire Lower Urinary Tract quality of life (ICIQ-LUTSqol) questionnaire and following this were interviewed via Zoom using a semi-structured approach. During the interview participants self-rated their movement across recovery trajectories. Findings were compared between the 2018 study and the 2022 follow-up.

Comparison of the women’s 2018 and 2022 overall ICIQ-LUTSqol scores approached but did not reach statistical significance. However, most participants described some areas of improvement and improved quality of life after surgical and/or non-surgical intervention for mesh complications. These interventions, along with interactions with key health stakeholders, continue to have significant impacts, both positive and negative, on women’s lived space, body, time, relationships and recoveries.

Introduction

Polypropylene mesh commonly used for abdominal repairs was first used in the female pelvis for vault prolapse in 1993. By 1997 polypropylene mesh was being used in urogynaecological surgery in New Zealand. Notifications from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 and 2011 flagged complications with mesh1,2 and in 2016 the FDA changed the status of transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) from Class II (moderate risk) to Class III (high risk).

In New Zealand high complication rates with pelvic mesh were brought to the attention of the Parliamentary Health Select Committee in 2014 via a petition. The Ministry of Health (MOH) responded to recommendations of the Health Committee by establishing a Surgical Mesh Roundtable in 2017 with all stakeholders, including consumers, to begin work on implementing the Committee’s recommendations.

In 2018, in response to one of the recommendations, the New Zealand government asked people injured by surgical mesh to share their experiences to improve future patient safety as part of a restorative process. More than 600 consumers, family members and health professionals shared their stories. As a result of the report and recommendations of this process, four key workstreams evolved – credentialling, education and harm prevention, specialist mesh services and a registry workstream3. It is against this background that insider research in 2018 reported the lived experience of seven New Zealand women with pelvic surgical mesh complications4.

Literature overview

The pool of literature focusing on clinical aspects of surgical mesh complications continues to grow5–8. Writing about best practice in diagnosis and treatment, Bueno Garcia Reyes and Hashim describe the symptoms of patients with mesh complications saying that they can be “catastrophic” with a huge impact on health and quality of life9. There is now some international consensus on the management of mesh complications10. However, there remains limited qualitative research from the women’s lived perspective.

Dunn et al. undertook one of the first qualitative studies in 2014, interviewing 84 women experiencing surgical mesh complications. They identified three recovery trajectories, finding that only a small number of women fell into the third category, returning to health. Most continued to have ongoing challenges with their recoveries. The authors compared their findings with their previous study of women awaiting surgery for POP and noted that the difference was “the sustained, emotional, and life-changing trajectory of women who experience repair of mesh complications” along with the amplification of “the severe pain, despair and permanent loss of physical and socioemotional health”11.

A qualitative systematic review in 202112 examined women’s experiences of and perspectives on surgical mesh for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and POP and suggested that women’s agency in managing complications should be recognised. Medical professionals, they suggested, had a special responsibility towards women who have been unable to adapt to their changed lives. They also highlighted the importance of patient-centred accounts of outcomes12. A 2022 study that analysed 153 women’s written submissions to the Australian Senate Inquiry gave insight into women’s lived experience, highlighting that “impacts rarely affected only one health domain; instead adverse physical, psychological and social experiences interacted resulting in reduced quality of life for women”13. A 2023 study acknowledged that women’s lives are “irreversibly altered” by mesh complications and noted that some participants demonstrated resilience in the form of acceptance of their situation14.

Inquiries in Australia, the United Kingdom, Scotland, and New Zealand that have incorporated submissions from large numbers of mesh-injured women have identified problems with device regulation, adverse event monitoring, acknowledging harm, the lack of data due to the absence of registries, inadequate informed consent, and women’s loss of trust in the medical profession3,15–18.

The qualitative report of the New Zealand restorative justice process for surgical mesh harm described multiple physical and psychosocial harms experienced by mesh-injured men and women who shared their stories. The report noted they were left “grieving losses to their physical wellbeing, relationships, identity, employment and financial status”19.

The current follow-up study aimed to follow up the 2018 study participants’ lived experience of interventions for their mesh complications and establish the impact of these interventions on their quality of life and wellbeing. As much of the research on mesh complications is international, a secondary aim was to provide local data to inform the evidence base in New Zealand.

Methods

Hermeneutic phenomenology asserts that individuals are as unique as their life experiences20. This methodology was used to investigate the women’s lifeworlds across four domains – impact on day-to-day life (lived space), body and ability to do what you need to (lived body), hopes and plans for the future (lived time), and relationships with others (lived other)21.

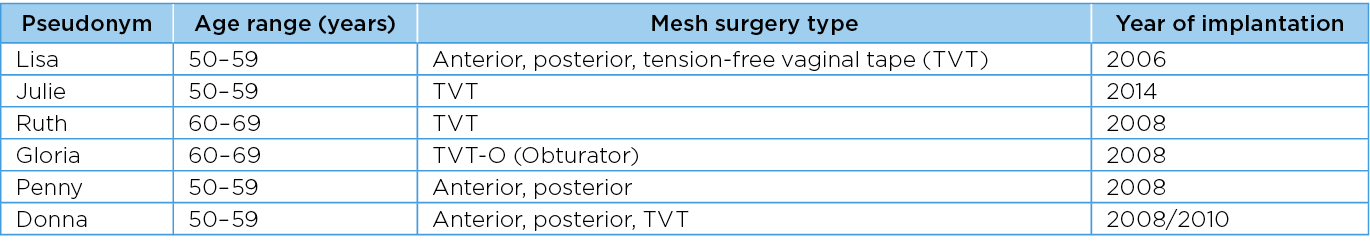

Participants from the 2018 study were contacted by email and asked if they would be willing to participate in a follow-up study. All seven agreed, one later withdrawing for family reasons. All participants were of European ethnicity, their average age was 49 years, ranging from 43–69 years of age. Four of the seven women had SUI and POP combination surgeries, one had POP only, and two had SUI only (Table 1).

Table 1. Participant surgery types

An extension of University of Otago Human Ethics Committee Approval No: H17/142 was granted and the participants consented. Following this, they were asked to complete a repeat International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire Lower Urinary Tract quality of life (ICIQ-LUTSqol) without referring to their 2018 questionnaire. The researcher re-read each participant’s 2018 interview transcript and compared the 2018:2022 ICIQ-LUTSqol questionnaires prior to interview. Participants were then interviewed via Zoom (an online video conferencing software) for up to 1 hour with semi-structured questions across five key areas:

- Events since 2018 in terms of pelvic surgical mesh complications and any subsequent interventions.

- Lifeworld changes.

- Where participants felt they sat in terms of Dunn et al.’s recovery trajectories – cascading health problems, settling for a new normal and returning to health11.

- Sources of strength, comfort and hope.

- Participation in the New Zealand MOH restorative process and its impact.

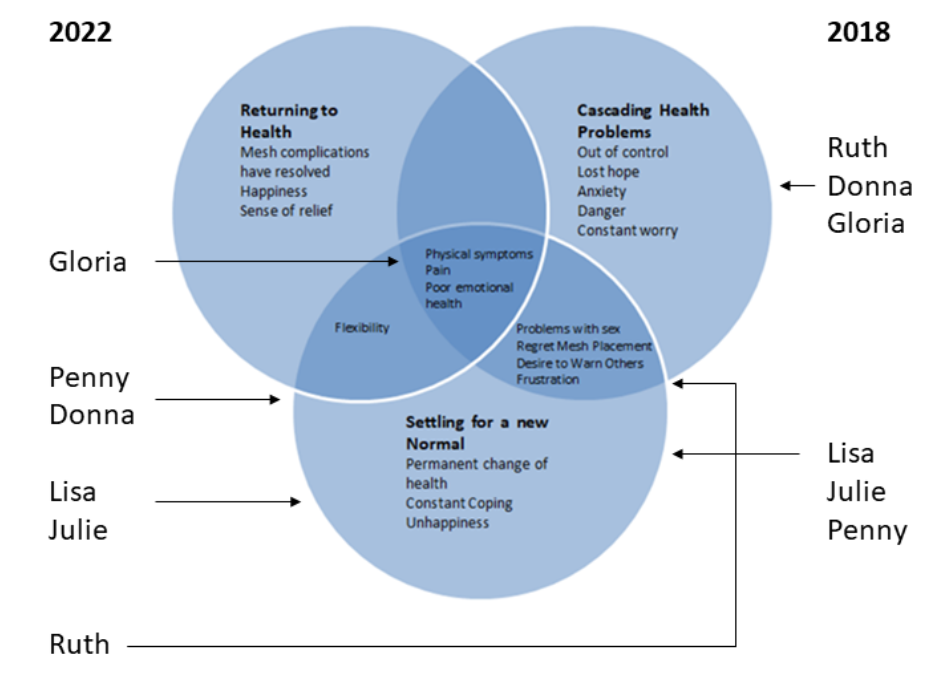

As part of the interview, Dunn et al.’s recovery trajectory Venn diagram was shown and explained, and women were invited to locate where they felt they were in terms of their recovery11. Dunn et al.’s recovery trajectories consist of three interconnecting trajectories:

- Cascading health problems – where women experienced a cascade of health problems and felt their health was out of control.

- Settling for a new normal – where women who once considered themselves healthy now believed they were unhealthy, constantly coping with permanent changes to their health.

- Returning to health – where women described a resolution of most symptoms and issues11.

Transcripts were returned to participants to validate. This was an intentional act of empowerment to enable them to remain in control of their own story. None of the women requested any changes. Transcripts were themed line by line separately and as a group and annotated as key words, phrases or themes emerged. These were compared with the 2018 transcripts. Likewise, the participants’ ICIQ-LUTSqol were compared. Overall themes were extracted and linked to relevant narrative and lifeworld existentials, with the aim of using as much of the women’s verbatim narrative as possible. The same pseudonyms were used as in the original research.

Findings

Five of the six participants had undergone assessment and surgical intervention since the 2018 study (Table 2). Two had travelled overseas at their own cost to seek treatment, a further two had full removal in New Zealand, and one had removal of remnant mesh, also in New Zealand.

Table 2. Interventions since 2018

Choosing to have or not have an intervention, surgical or otherwise, is not always clear cut and the women had to make difficult choices not knowing what the outcome might be. Julie and Gloria took matters into their own hands after being unable to get the help they needed in New Zealand and sought removal of their mesh in the US. The number of women that have travelled overseas for self-funded mesh removal surgery is not known. In Julie’s case, the surgeon removed more mesh than she had been told remained. Gloria underwent a 7.5-hour surgery where both the Prolift mesh and TVT-O sling were removed intact.

Both Julie and Gloria experienced improvements postoperatively – Julie with mobility, and Gloria with mental clarity, improved sexual function, and the ability to lead a more active social life. However, both agree that recovery after full removal is a long process, Gloria took 18 months to recover fully, and Julie is still in the recovery phase nine months postoperative at the time of interview.

Assessment of lifeworld themes

The women’s lifeworlds across four domains – impact on day-to-day life (lived space), body and ability to do what you need to (lived body), hopes and plans for the future (lived time), and relationships with others (lived other)21 – are outlined below.

Lived space: day-to-day existence

Postoperatively, most of the women experienced gains, but conversely some disappointment when symptoms that they had hoped would resolve with mesh removal did not. Postoperatively, Ruth’s expectation for her day-to day existence was:

To get better and that life would return to normal, but that didn’t happen. I’m no better off, worse actually… very incontinent, no control whatsoever now, still got groin pain, still get infections, but not as many as I had before. People say that they feel so good after it’s out… feel a difference. I didn’t.

As with the 2018 study, narrative relating to the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) took up a large part of the women’s responses during the interviews. The ACC is a no-fault personal injury insurance scheme that also covers treatment injury as a direct result of medical treatment where the injury is not a normal side effect of treatment. One of the biggest impacts on four of the women’s lived space was the sense of loss of control and lack of choices engendered by their contact with the ACC system.

After 13 years of battling, assessments, reviews, appeals and a heart attack that she attributes to the stress, Ruth’s claim was finally fully accepted. She said:

I got an email after all this fighting for 13 years and I get an email to say we’ve accepted it and it’s all over. And… you’re uptight, and you’ve fought for so long you couldn’t just relax and think I’ve won and now it’s finished. It didn’t feel any different.

Julie, who had an approved claim, explained how it felt to be dependent on ACC support on a daily basis:

I am solely reliant on ACC and when you get a new case manager, and they cancel something on you it just throws your whole world into chaos. And unless you live and breathe ACC every day, the fear that you live in… it's horrible. You don’t have a choice; you just have to grin and bear it really.

Lisa described the ACC as constantly “on my back” and shared the difficulty of dealing with the ACC while working around pain:

I’ve got to respond to their emails in a timely manner, but I can’t think too much when I am in too much pain. So, effectively, it puts me in danger of losing my services. They are keeping me so damn busy that it’s really hard to live.

Describing herself as “broken but healthy”, Lisa has engaged a life coach to help her achieve her goals.

Lived body: being bodily in the world

Even non-surgical interventions carry risk. Julie had been offered a nerve block for pain originating from the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve, but the possibility of not being able to lift her leg is a trade-off she was not prepared to risk. Ruth had been offered Botox injections to improve her continence, as the neuromodulator (device which uses electrical stimulation of nerves to modulate bladder and/or bowel function) implanted after her mesh removal had not been as successful as hoped. She explained:

The latest thing is they are going to do Botox, and then if that doesn’t work… I will then just have a stoma and a bag.

Options for a further surgery to remove the remaining mesh from her bowel are so daunting for Donna that she has decided to put that surgery “on hold”. She said:

So, the options to get that bit out I would either have to have an open wound in the perineum for six months, or they would go in through my abdomen and it would highly likely damage the bowel and have to have some bowel removed. So now I’m pretty much… this is me.

Two women had neuromodulators inserted to help them manage their bowel and bladder incontinence. Both women have experienced complications with these. Ruth had a wire dislodge during physiotherapy, requiring replacement of her neuromodulator. For Julie, using the neuromodulator is a constant trade-off between continence and pain. She explained:

When I didn’t have the neuromodulator working when I came back from America, I could sit for up to two hours, so I could actually watch a movie. When [NZ surgeon] put the neuromodulator in, it’s in S3 and that posterior femoral cutaneous nerve comes out of S1–S3, it restimulated it, and that’s why I can’t sit. So, I can turn my neuromodulator off when it’s really bad, but the problem is I’m incontinent, and then I have a mess to clean up.

The interventions these women had undergone since 2018 continue to have a significant impact on how they are bodily in the world, requiring constant adaption.

Lived time: past, present and future

Gloria reported substantial improvement in her narrative, but her overall ICIQ-LUTSqol score did not reflect this. Gloria explained that she felt she had been getting her life back and:

... [husband] and I are looking at future plans now rather than worrying I might die.

She described her mesh explant surgery as a “life changer” and while not yet completely recovered, described feeling mentally “on top of it”. She is now able to do some volunteer work and gains a sense of purpose from this.

Lisa struggled with not having a sense of purpose and linked this to employability:

It’s really hard to get up when you’ve got nothing to do… Losing your employment you lose part of your confidence… you second-guess yourself. It’s also just to be a functional member of society. You don’t feel like you are.

Ruth had been working with a psychologist who was supporting her to let go. She said:

I’ve accepted my lot, and this is it… I’ve just got to live with the life that I’ve got now.

Dibb et al. describe this acceptance as a demonstration of resilience14.

Lived other: social and interpersonal

The importance of the support of significant others as a source of strength is a continuing theme. Two women continued to find strength in their faith in God, while for those that had a spouse, the support of their spouse was vital to their ability to adapt and cope.

Ruth explained:

Without [husband’s name] I wouldn’t have coped… I would have ended it. I wouldn’t have carried on.

Post-surgical intervention, Gloria and Penny had been able to recommence intercourse with their husbands. Sadly, for Ruth, surgical intervention worsened her urinary and faecal continence to the point where it negatively impacted on her ability to have intercourse. The loss of sexual intimacy as a significant cause of grief and loss is well described in the literature3,4,7,11,15,16.

All the women in this study participated in the MOH restorative process Listening Circles. These were facilitated meetings of between 10–20 participants where those harmed shared their stories with each other and key health stakeholders. Some chose individual conferences or contributed to a story database. This gave them an opportunity to be heard and have their lived experience validated. It took courage to share their vulnerability with a group of people they didn’t know, and most were concerned about breaking down while telling their stories. Some women found the experience empowering. Gloria explained:

I wasn’t just a complaining old woman. I was a person who mattered. I didn’t feel alone anymore. I had the language and a voice thanks to Mesh Down Under [online support group].

All but one of the women found it cathartic to some degree, whether it was just writing their story down, or getting it “off their chest” and most had family/whānau attend to support them and share their perspective. However, all six women had concerns about whether the restorative process has changed anything as they have not observed or experienced significant systemic improvements. An evaluation of the restorative approach10 highlighted that consumers were largely unaware of progress on the 19 actions recommended by the MOH, and this is reflected in the women’s responses.

2018:2022 comparisons

Lifeworld themes 2018:2022

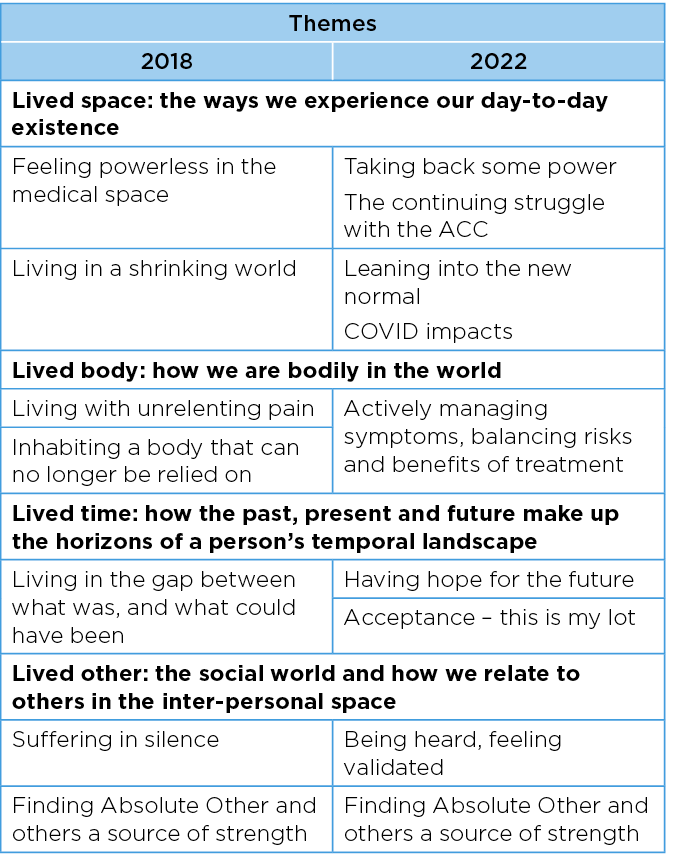

Using Van Manen’s Lifeworld existential domains21 the themes from the current study were compared with those from the 2018 study (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of themes 2018:2022 in relation to Van Manen's Lifeworld existential domains21

There are significant changes and adaptions in the women’s lifeworlds. Previously feeling as though they were living in shrinking worlds, the women have leaned into the new normal, despite the additional isolating impacts of COVID-19. The women have expanded their worlds where they can and developed resilience where they cannot. While their bodies still cannot be relied on as they were pre-mesh, the women are confident in their expert knowledge of their own bodies and actively managing their day-to-day symptoms. They balance rest and activity to allow them to participate in the activities that are important to them. They have actively sought treatment and in doing so are faced with difficult choices, risks and benefits to balance, and unknown outcomes. Even small improvements as a result of interventions (surgical and non-surgical) have enabled them to have hope for the future.

ICIQ-LUTSqol scores 2018:2022

Although descriptively the ICIQ-LUTSqol 2022 scores were lower than the 2018 scores, they did not reach statistical significance (affect: M2018=9, T2022=8.33, t(5)=1.348, p=0.12; bother: M2018=63.66, M2022=61.0, t=1.38, p=1.11). However, it is worth noting that the sample size was small, and the observed differences were in the predicted direction and approached statistical significance. Had the sample size been larger, the study may have detected a significant effect.

Recovery trajectories

In the 2018 analysis of the interview narratives the researcher determined where participants sat in terms of their recovery trajectories using Dunn et al.’s Venn framework11. In the current study the participants were shown the Venn diagram during the interview with an explanation, and asked to rate where they felt they sat. Figure 1 highlights the differences 2018:2022.

Figure 1. Dunn et al.’s recovery trajectories comparison 2018:2022

Lisa felt that her ongoing struggles with the ACC meant that she was unable to move beyond “settling for a new normal”. Julie was still finding her new normal after her surgery. Ruth, experiencing a worsening of her continence post full removal, felt that she was sitting between dealing with the “cascading health problems” related to the surgery, and accepting that that was her new normal. Gloria also selected a midpoint between “settling for a new normal” and “returning to health” that emphasised ongoing physical symptoms. Donna and Penny selected this midpoint as well but with emphasis on the increasing flexibility they now experienced in their lives.

Each surgical intervention required adapting to a “new normal” and sometimes dealing with a range of new or cascading health problems before finally reaching that new normal. The new normal looks different for every woman. The women in this study are unlikely to experience full resolution of their mesh complications because of the severity of their injuries. However, acceptance of their reality, the support of significant others and the active management of physical symptoms giving a sense of control appeared to be a key factor to improving mental and emotional health.

Discussion

The most striking observation during the Zoom interviews was the improvement in mental and emotional wellbeing evident in the women’s demeanour during interview. This was despite the acknowledgement in their narratives that for them there will be no return to health that equates with their health pre-mesh implantation.

This improvement is demonstrated in the contrast in themes, those in 2018 evidencing grief, loss and suffering, the 2022 themes evidencing resilience, acceptance and moving forward. This may be due to a combination of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Extrinsically, the increased understanding by the national and international medical community of the harms caused by pelvic surgical mesh and various inquiries have given voice to those injured by mesh. They have laid bare the multi-faceted impacts of the harm and have shattered the ‘silence’. While this has improved the women’s lived space in a broad sense, they continue to struggle with other factors that limit their agency on a day-to-day basis. Despite high level engagement by the ACC in the restorative process and associated structural improvements in the organisation, participant narratives suggest there is more work to be done at the interface with mesh-injured women.

From a lived body perspective, the women are faced with potentially life-changing decisions about interventions without the benefit of recent clinical studies to guide understanding of risks and benefits.

Intrinsically, acceptance of their changed lives has led to adaptation, moving forward with what is possible with increasing resilience. Edgar and Pattison describe this movement in relation to quality of life, arguing that as patients become used to their condition, they modify their expectations and goals; they re-identify themselves as successful persons with disabilities and may even flourish despite the absence of some material conditions of wellbeing22. This is evident with the women in the study in terms of lived time, as they have each engaged with their past mesh injury, made sense of their new normal and have some hope for the future. Surgical and non-surgical interventions have enabled them to regain some quality of life and achieve varying degrees of wellness across bio-psycho-socio-spirito domains.

Mesh complications have a well-documented negative impact on intimate relationships4,11,15,16,18,23. In terms of lived other, this study showed the practical and psychological support of others have a reciprocal but positive impact on the wellbeing of the women. For women in this study with partners, their partner was integral to their ability to cope with their mesh complications. For those without partners, the support of children, and the knowledge gained through Listening Circles that they were not alone was significant.

While descriptively the ICIQ-LUTSqol showed improvements in quality of life, the total scores and overall bother levels did not reach statistical significance. However, the ICIQ-LUTSqol provided a holistic framework within which to explore aspects of quality of life, providing consistency between the 2018 study and the present study.

Limitations

A limitation of the study is its small sample size; however, this is not uncommon for qualitative research. Its strengths are that it built on the 2018 study, followed the women over four years, and used the adapted ICIQ-LUTSqol to explore aspects of quality of life. The author’s insider status and prolonged engagement in the field allowed access to the women’s private stories. Radley and Billig suggest that whether the researcher gets the private or public account depends on the interviewer relationship24. This study was conducted on the strength of a four-year relationship with participants. Radley and Dua posit that clinical interview data is prone to inaccuracy and non-disclosure due to the taboo nature of pelvic floor disorders25. Being an insider researcher and using qualitative methods helped counter this. While insider researchers may sacrifice some objectivity, the depth of the information they are able to gather is considered valuable compensation. Kerstetter argues that in fact all researchers fall somewhere on a continuum between complete insiders and complete outsiders26.

A further limitation is that all the study participants were of European ethnicity. ACC statistics show that there were only a small number of women from Māori, Asian, Pasifica and other ethnicities who experienced mesh complications27; however, this may be due to underreporting and inequity of access to health services.

Conclusion

Qualitative research related to women’s experience of treatment for surgical mesh complications is limited. This follow-up study showed that both surgical and non-surgical interventions can have significant impacts, both positive and negative, on women’s lived space, body, time and relationships with others.

Key health stakeholders sharing the power, giving information and options, hearing and responding actively and in a timely manner to the multiple harms caused by surgical mesh is important for women’s quality of life and wellbeing. Respecting women’s agency and enabling them to self-identify the interventions and resources they need to flourish is critical.

I am hopeful that as specialist mesh clinics begin to provide funded multidisciplinary and holistic wrap-around care for New Zealand women with mesh injury many more women will experience improved quality of life and renewed hope for the future. It is vital that further lived experience research examining the impact of interventions for complications is undertaken. Co-designing outcome measures with mesh-injured women would provide direction for future interventions and service development.

Author(s)

Jacqueline L Tuffnell

Department of Theology and Religion, University of Otago, New Zealand

Email jacqueline.tuffnell@postgrad.otago.ac.nz

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The author received no funding for this study.

References

- US Food and Drug Administration. UPDATE on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse [safety communication]; 2011 July 13.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence [public health notification]; 2008 [cited 2023 March 6]. Available from: http://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170111190506/http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm

- Wailling J, Marshall CD, Wilkinson JA. Hearing and responding to the stories of survivors of surgical mesh (Ngā kōrero a ngā mōrehu – he urupare): report for the Ministry of Health. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington, Te Herenga Waka; 2019 [cited 2023 July 20]. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/hearing-and-responding-stories-survivors-surgical-mesh

- Brown JL. The experiences of seven women living with pelvic surgical mesh complications. Int Urogynecol J 2020;31(4):823–9.

- Pace N, Artsen A, Baranski L, Palcsey S, Durst R, Meyn L, et al. Symptomatic improvement after mesh removal: a prospective longitudinal study of women with urogynaecological mesh complications. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2021;128(12):2034–43. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.16778

- Morton S, Wilczek Y, Harding C. Complications of synthetic mesh inserted for stress urinary incontinence. BJU Int 2021;127(1):4–11. doi:10.1111/bju.15260

- De Vries C, Boszek B, Oostlander A, Van Baal J. Long term complications of transvaginal mesh implants: a literature review. Netherlands: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment; 2018 [cited 2023 July 20] Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/2018-0130.pdf

- Carter P, Fou L, Whiter F, Delgado Nunes V, Hasler E, Austin C, et al. Management of mesh complications following surgery for stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2020;127(1):28–35. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15958

- Bueno Garcia Reyes P, Hashim H. Mesh complications: best practice in diagnosis and treatment. Ther Adv Urol 2020;12:1756287220942993. doi:10.1177/1756287220942993.

- Rardin CR, Duckett J, Milani AL, Paván LI, Rogo-Gupta L, Twiss CO. Joint position statement on the management of mesh-related complications for the FPMRS specialist. Int Urogynecol J 2020;31(4):679–94. doi:10.1007/s00192-020-04248-x

- Dunn GE, Hansen BL, Egger MJ, Nygaard I, Sanchez-Birkhead AC, Hsu Y, et al. Changed women: the long-term impact of vaginal mesh complications. Female Pelvic Med & Reconstr Surg 2014;20(3):131–6.

- Motamedi M, Carter SM, Degeling C. Women’s experiences of and perspectives on transvaginal mesh surgery for stress urine incontinency and pelvic organ prolapse: a qualitative systematic review. Patient 2022;15(2):157–69.

- McKinlay KA, Oxlad M. ‘I have no life and neither do the ones watching me suffer’: women’s experiences of transvaginal mesh implant surgery. Psychol Health 2022:1–22. doi:10.1080/08870446.2022.2125513

- Dibb B, Woodgate F, Taylor L. When things go wrong: experiences of vaginal mesh complications. Int Urogynecol J 2023;34(7):1575–81. doi:10.1007/s00192-022-05422-z

- Siewert RC. Number of women in Australia who have had transvaginal mesh implants and related matters. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, Committee TSCA; 2018 [cited 2023 July 20]. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/publication/publications/australian-government-response-senate-community-affairs-references-committee-report

- The Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review. First do no harm: The report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review; 2020 [cited 2023 July 20]. Available from: https://www.immdsreview.org.uk/Report.html

- The Scottish Government. Scottish independent review of the use, safety and efficacy of transvaginal mesh implants in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: final report; 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/independent-report/2017/03/scottish-independent-review-use-safety-efficacy-transvaginal-mesh-implants-treatment-9781786528711/documents/00515856-pdf/00515856-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00515856.pdf

- Health and Social Care Alliance. My life, my experience: capturing lived experience of complication following transvaginal mesh surgery. Glasgow, Scotland: Health and Social Care Alliance; 2019 [cited 2023 July 20]. Available from: https://www.alliance-scotland.org.uk/blog/resources/my-life-my-experience/

- Wailling J, Wilkinson J, Marshall C. Healing after harm: an evaluation of a restorative approach for addressing harm from surgical mesh. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka; 2020 [cited 2023 March 3]. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/healing-after-harm-evaluation-restorative-approach-addressing-harm-surgical-mesh

- Miles M, Francis K, Chapman Y, Taylor B. Hermeneutic phenomenology: a methodology of choice for midwives: hermeneutic phenomenology methodology. Int J Nurs Pract 2013;19(4):409–14.

- Van Manen M. Researching lived experience human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany NY: State University of New York Press; 1990.

- Edgar A, Pattison S. Flourishing in health care. Health Care Anal 2016;24(2):161–73.

- Brown J. A thorn in the flesh: the experience of women living with pelvic surgical mesh complications. Master of Chaplaincy. Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago; 2019.

- Radley A, Billig M. Accounts of health and illness: dilemmas and representations. Sociol Health Illn 1996;18(2):220–40.

- Radley S, Dua A. Quality of life measurement and electronic assessment in urogynaecology. Obstet Gynaecol 2011;13(4):219–23.

- Kerstetter K. Insider, outsider, or somewhere in between: the impact of researchers’ identities on the community-based research process. J Rural Soc Sci 2012;27(2):99–117.

- Accident Compensation Corporation. Analysis of treatment injury claims 1 July 2005 to 30 June 2014. Wellington, New Zealand: Accident Compensation Corporation; 2015 March 13 [cited 2023 March 3]. Available from: https://www.acc.co.nz/assets/provider/surgical-mesh-report.pdf