Volume 22 Number 2

Exploring wellbeing in individuals with diabetic foot ulcers: the patient perspective

Lauren Connell, MPhil, Claire MacGilchrist, PhD, Molly Smith, BSc, Caroline McIntosh, PhD.

Keywords wellbeing, Diabetes, diabetic foot ulcers, outcome measures, PPI

DOI 10.35279/jowm202107.08

Abstract

Background Optimising wellbeing for those living with DFU is a critical component of holistic patient management. Evidence demonstrates that outcomes improve when patients are actively involved in their care. Yet, wellbeing is often overlooked for patients with DFU and there is a lack of measurement tools regarding this concept.

Aim The aim of this research process was to identify—through PPI collaboration and engagement with patients—the potential for development of a wellbeing tool specifically for people living with DFU.

Methods A PPI panel consisting of six members was established. The COM-B model as a framework and trigger questions on wellbeing were used as a focus for tool generation. The guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 – Short Form (GRIPP2-SF) was used to guide the process.

Findings All content was analysed using thematic analysis to map emerging themes and subthemes and create recommendations. A total of five recommendations were developed: 1. Patient education, 2. Self-efficacy, 3. Health literacy and knowledge translation, 4. Social support and 5. Holistic approach.

Conclusions Further research in this area should comprehensively address the holistic elements of wellbeing to optimise outcomes for those with DFU. The development of an outcome tool for wellbeing is required to support further research.

Implications for clinical practice Healthcare professionals should adopt a holistic approach to the care of patients with DFU. Early and positive education strategies are needed, particularly at the point of diagnosis. The participants recommended access to suitable coping strategies and encouragement from care providers to improve self-efficacy. Psychological support should be integrated into the care of people suffering from diabetes and DFU.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, there has been an increased prevalence of diabetes across the globe.1 This has led to a higher incidence of diabetes-specific complications, including diabetic foot disease (DFD), which is associated with devastating outcomes, including diabetic foot ulceration (DFU), amputation and premature death.2 DFU is a common complication of diabetes, with an estimated global prevalence of 6.3%.3 It is recognised as a burdensome complication that comes with a high cost of treatment and a five-year mortality rate comparable to that of cancer.4

People with DFU are at risk of depression, anxiety and low self-esteem.5 Such psychosocial factors are known to be associated with delayed healing.6 Evidence shows that outcomes improve when individual patients are actively involved in their care.7 Treatment goals should aim to optimise wellbeing and engage patients in their treatment. However, while the physical aspects of DFU can be measured easily, the concept of “wellbeing” is more difficult to capture.7,8

For those with DFU, wellbeing may be adversely affected by non-healing wounds, while people with healed ulcers may have a poorer health-related quality of life due to fear of recurrence and/or amputation.9 Furthermore, DFU can significantly impact an individual’s wellbeing—including spirituality—and engrain feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness for the future.10 The concept of wellbeing extends beyond physical symptoms and considers the holistic wellbeing of the person as well. Wellbeing can be defined as “a dynamic matrix of factors, including physical, social, psychological and spiritual. The concept of wellbeing is inherently individual, will vary over time, is influenced by culture and context, and is independent of wound type, duration or care setting”.7

Wellbeing encompasses multifactorial considerations from a psychosocial perspective. However, within research and clinical practice on people living with chronic lower extremity wounds, the topic of patient wellbeing is often overlooked and the focus is more frequently put on quality of life issues. The concept of wellbeing may not be assessed appropriately due to a lack of resources and evidence to support its importance in clinical practice.2 This is despite International Consensus documents on wound care suggesting that optimising patient wellbeing can lead to improved patient and clinical outcomes.7 Enhanced wellbeing is also recognised to be associated with wider economic and social benefits.7 Therefore, it is necessary to optimise wellbeing in this patient population in a comprehensive and holistic manner with appropriate patient engagement.

Wellbeing is assessed to gain insight into how patients perceive their lives.10 It is an important indicator of the level of social adaptation, life satisfaction and leisure participation of patients living with ulcerations.10 A dearth of literature exists concerning patient wellbeing, yet addressing wellbeing in this high-risk group has the potential to prevent DFU and aid healing in those living with it through improved quality of life, promotion of positive health behaviours and improved patient outcomes.

Patient-reported outcome measurement tools used in wound care are generally generic for chronic wounds and only address certain parameters of wellbeing. The research team completed a scoping review11 of tools to evaluate wellbeing in people with DFU and there are currently no tools that specifically measure wellbeing in this disease and existing generic tools fail to address the more holistic concept of wellbeing, including physical, psychological, social and spiritual factors.11

Traditionally, studies aiming to optimise outcomes for DFU have not incorporated the perspective of individuals with lived experience of this disease. With the advent of patient and public involvement (PPI) initiatives in recent years, including the establishment of organisations such as INVOLVE12 - originating in the UK - there is now an increased uptake of PPI in recognition of its importance in the setting of research priorities.8 INVOLVE defines public involvement in research as “research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ’to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’”.12 Currently, PPI in the area of wellbeing in DFU remains under-utilised. As the concept of wellbeing is underreported in the literature, using an innovative PPI approach in research, this body of work set out to include stakeholders in the research process from design and development to dissemination. Working in partnership with individuals affected by DFU will help map future research priorities and guide public involvement. Therefore, the aim of this research study was to identify, through PPI collaboration and engagement with patients, the potential for the development of a wellbeing tool specifically for people living with DFU.

METHODS

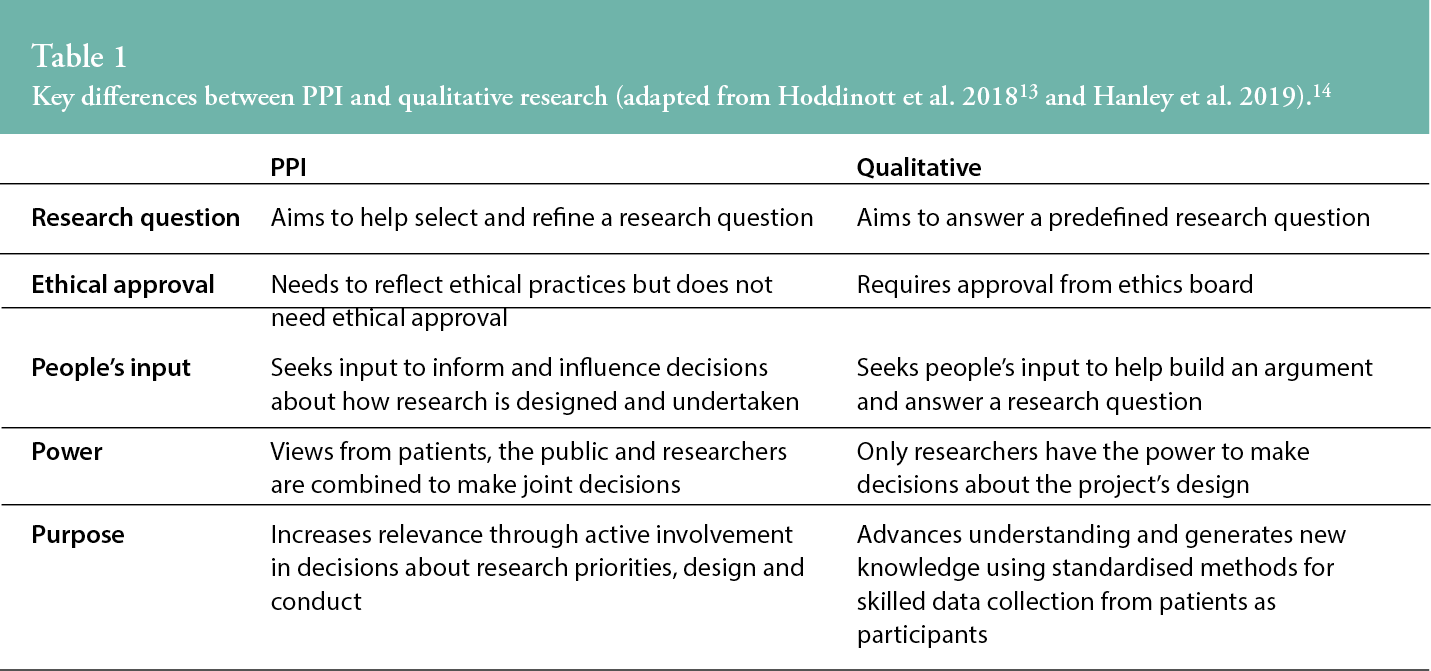

A PPI panel was established to gain insight into the barriers and enablers experienced by the DFU community to inform the development of a measurement tool to assess wellbeing in people with DFU. PPI research has key differences with qualitative research, as outlined in Table I below.13,14

The PPI panel was established through a recruitment strategy including a social media campaign and clinician involvement in a podiatry clinic in western Ireland.

A PPI exercise was undertaken involving face-to-face discussions with six individuals affected by DFU. Thematic analysis (TA) of the discussion content was undertaken to develop recommendations related to wellbeing and its subdomains in DFU. A similar approach was adopted by researchers reporting on a PPI event that sought patient and carer involvement to identify research priorities and address a lack of their involvement in wound care research.15

A private room was chosen at this clinic in agreement with the PPI panel to facilitate one-on-one meetings with the primary investigator and facilitator (LC), under Covid-19 regulations on social distancing and travel. PPI panellists attended this clinic for their treatment regularly, which allowed their presence at the PPI session immediately afterwards and to avoid the need for further unnecessary travel. Similarly, a single facilitator met with each panellist to avoid needless contact and possible crowding, under the health regulations of the time.

The sessions with each PPI panellist lasted on average forty minutes. As it was not possible to have two facilitators present or a group meeting process, with the participants’ consent, LC took written field notes and audio recordings for personal use only to allow full engagement in this process. According to the local research ethics committee’s opinion, no formal ethical approval was required for this PPI process.

The COM-B model16 was used to help formulate a sequential format for the meeting while addressing multiple aspects of the individuals’ daily lives. The COM-B model was considered the most suitable framework because it can assist in identifying domains that might be targeted as levers for change to inform intervention design.17 The main objective of each PPI session was to discuss what the PPI stakeholders would like to be considered in the development of a tool to measure patient wellbeing and how it could be addressed from the patient’s perspective. The three aspects—capability, motivation and opportunity—were considered for what could affect individuals’ wellbeing. This was aided by previously suggested trigger questions,18 including:

- Has your wound improved or gotten worse? Please describe. If it is a new wound, how did it happen?

- Has your wound stopped you from doing things in the last week? If so, what?

- What causes you the most disturbance/distress and when does this occur?

- Do you have anyone to help you cope with your wound?

- What would help ease/improve your daily experience of living with a wound?

Daily routine and different times of the day were also

noted as a point of conversation, as it is acknowl-

edged that often disturbances regarding sleep, daily activities and dressings can occur with patients who have wounds.18

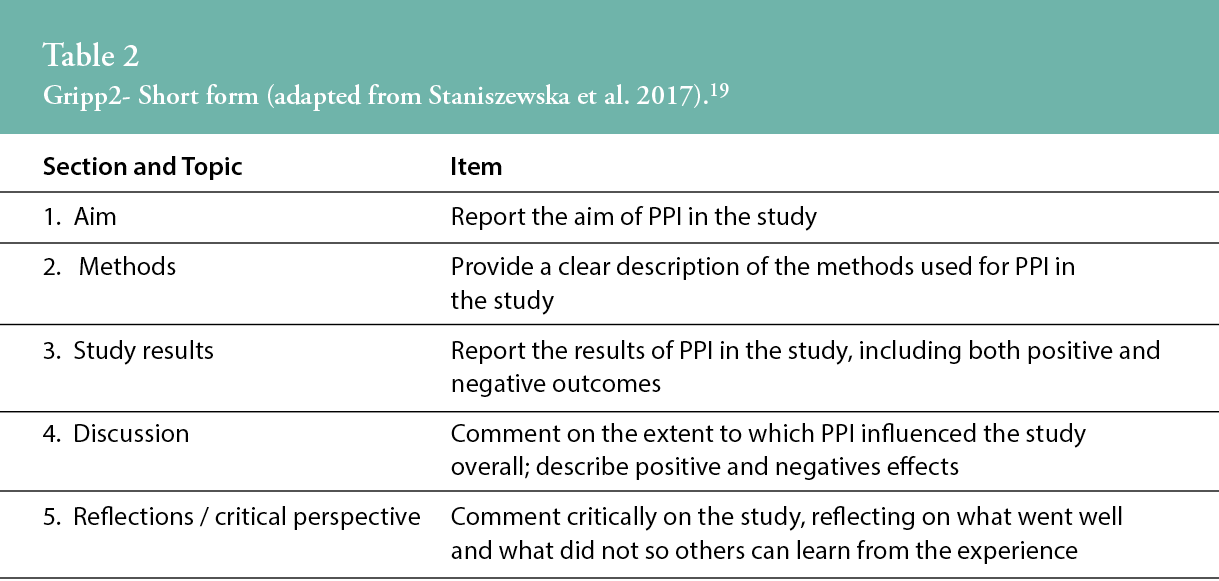

The Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 – Short Form (GRIPP2-SF) guided reporting of the PPI sessions to provide structure to the presentation of themes and subthemes in a coherent manner19 (Table 2).

All content was analysed using Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis20 as guidance to map emerging themes and subthemes from PPI engagement and create recommendations. The thematic analysis was undertaken subsequent to immersion of LC in the data collected in accordance with the six-step procedure set out by Braun and Clarke. Themes were identified on a semantic level, so resultant themes represented the explicit meaning of the presenting data, where the researcher did not aim to interpret the data.21 Similar methods have been used and are recognised as appropriate to analyse the findings of PPI given there is an absence of PPI-specific frameworks to formulate recommendations.15,22

FINDINGS

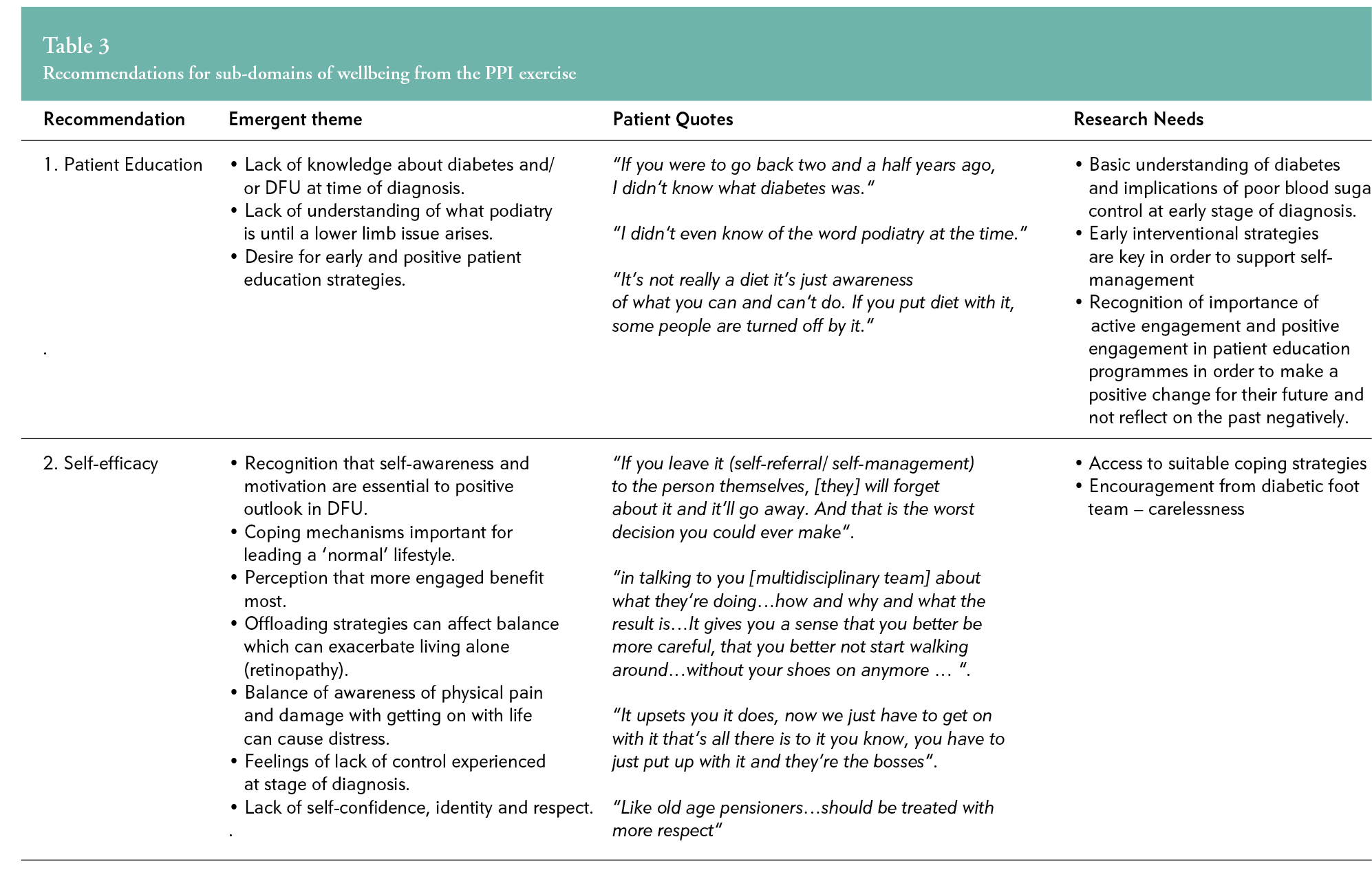

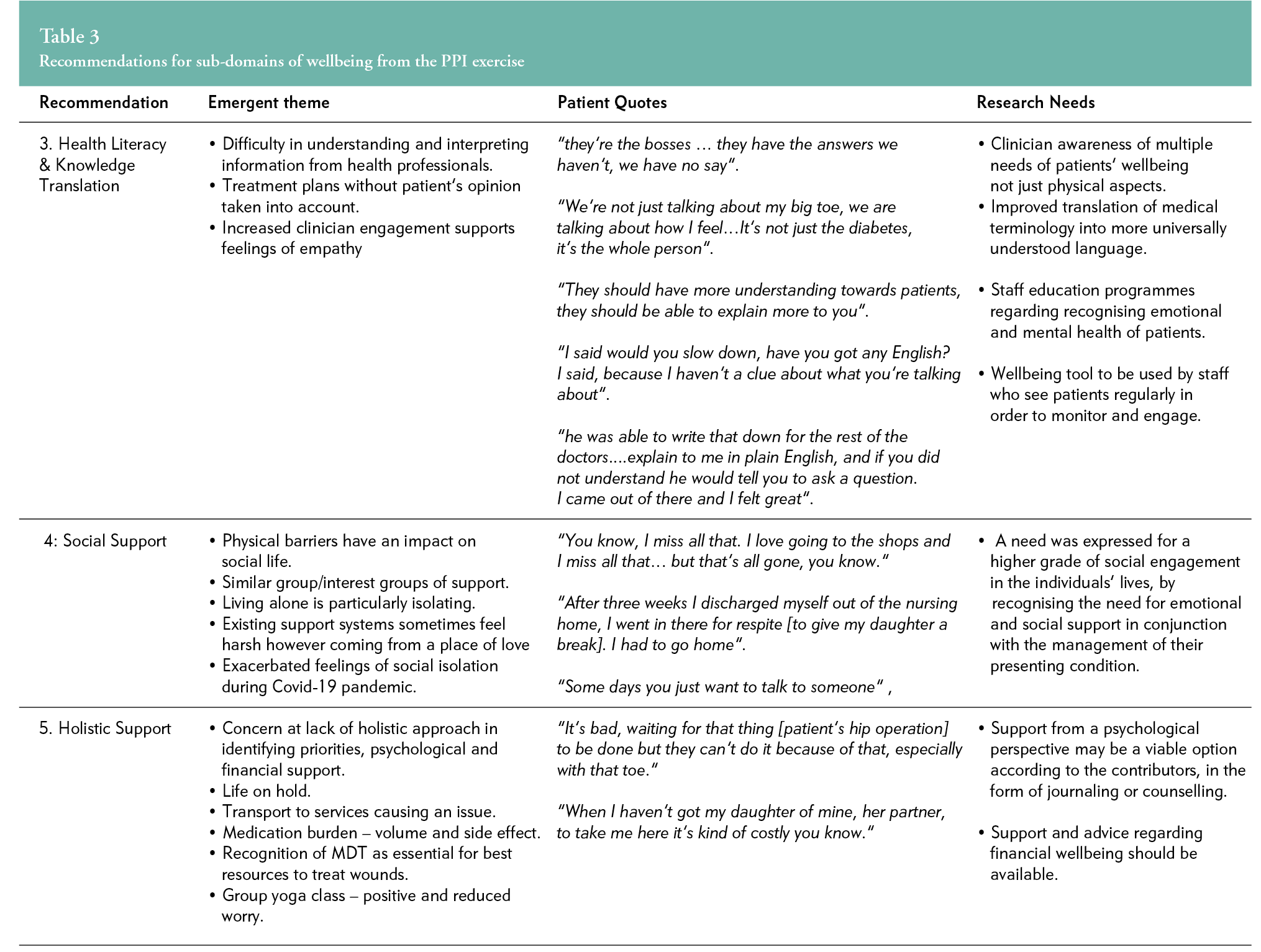

Five recommendations regarding the sub-domains of wellbeing were developed based on the thematic analysis of the stakeholders’ statements and are summarised as follows:

1. Patient education

Panellists perceived their knowledge of DFU and podiatry as poor early in their treatment and desired more patient education in both areas at an earlier stage.

2. Self-efficacy

Panellists communicated a need for increased self-awareness and coping strategies, which they felt were required for more positive outcomes.

3. Health literacy and knowledge translation

Panellists expressed difficulty in understanding and interpreting information, with a desire for staff education for a greater understanding of patients’ needs.

4. Social support

Feelings of isolation and physical limitations were articulated with a desire for increased social support in tandem with the management of their physical condition.

5. Holistic Approach

Concern was evident about the lack of understanding of competing patient priorities, such as psychological, financial and transport issues, and more support was sought in managing these.

Table 3 refers to the recommendations above in full.

DISCUSSION

The results of this PPI process support findings by other research in this area2 and the need for future research focusing particularly on the multidimensional facets of wellbeing involving PPI for people living with and/or affected by DFU. Panellists in this PPI process identified five key themes for consideration:

Patient education

Patient education is considered to be an important intervention to improve knowledge and change behaviour among people with diabetes and foot ulcerations.23 A Cochrane systematic review evaluated patient education programmes for preventing foot ulcers among people with diabetes mellitus. While the authors acknowledged that the evidence for the effectiveness of patient education for prevention of foot problems is still scarce, there is evidence that foot care knowledge and self-reported patient behaviour are positively influenced by patient education, at least in the short term.24 The individuals in the PPI process highlighted a desire for early and positive patient education strategies on diabetes and its complications, particularly at the time of diagnosis. Furthermore, individuals stressed the need for people to have a greater awareness of podiatry at an earlier stage rather than at the point of a foot complication arising. It has been recognised that patient education on diabetes is a predictor of podiatric self-care behaviours. Therefore, it is integral that clinicians recognise their position and ability to help motivate and inspire positive behaviours in this population.18

Research tends to focus on the education of patients. However, in this PPI process, all individuals highlighted the importance of education for care providers and suggested that education may be beneficial for healthcare professionals to increase their awareness of other modalities to help counsel patients and integrate them better, whether in the topic of motivational interviewing, health literacy training or other psychological approaches. Motivational interviewing has been found to be an effective intervention associated with positive behavioural change25 and has therefore been suggested as an intervention for those at risk of diabetic foot ulcerations to improve self-care, though further research is needed.25

Self-efficacy

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients who have higher self-efficacy are more likely to take part in regular positive foot self-care behaviours.26 Self-efficacy is defined as confidence in one’s ability to perform a particular behaviour and is expected to influence the likelihood of the behavioural occurrence.27 An increased focus on self-efficacy regarding diabetes self-care could be both cost- and time-effective for those at risk of lower limb complications.28 The PPI panellists acknowledged that self-awareness and motivation are essential for a positive outlook when living with DFU. They felt that those who engaged in self-care practices experienced the most benefits. The panellists spoke of feeling a lack of control—particularly at the stage of diagnosis—and a lack of self-confidence, identity and respect. They recommended access to suitable coping strategies and encouragement from care providers to improve self-efficacy. A pilot self-efficacy patient education programme was conducted in Malaysia to assess the feasibility, acceptability and potential impact of a self-efficacy patient education programme on improving foot self-care behaviour among older patients with diabetes.27 The findings of the study—post-intervention—demonstrated significant improvements in foot self-care behaviours and improved knowledge of foot care, glycaemic control and quality of life.27 While further research is warranted, a self-efficacy patient education programme may lead to positive health behaviours and improved outcomes.

Individuals also highlighted the need for coping strategies. Emotional distress, whether related to the disease process, ulcerations or other factors, prevents patients from performing adequate self-management behaviours.5 The stakeholders also expressed a desire for increased clinician engagement and training in recognising the signs of stress and depression. Healthcare professionals involved in caring for people with DFU should be aware of their patients’ affective state, mental health and its influence on self-care.5

Health literacy and knowledge translation

The PPI panel reported the need for healthcare professionals to have a greater awareness of the multiple needs of patients and not just the physical aspect of the DFU. They expressed difficulties in understanding medical jargon and terminology and interpreting information from health professionals.

Health literacy is an important consideration when treating patients with DFU. It has been reported that patients who have undergone diabetes-related lower limb amputations are eight times more likely to have inadequate health literacy.29 It has therefore been proposed that health literacy screening should be performed to identify individuals at risk and who may benefit from early intervention patient education programmes.29 One study focused on the training of undergraduate healthcare professionals for awareness of health literacy in their engagement with patients to optimise their consumption of material.30 The authors concluded that training health care students in readability assessments and plain language editing can reduce literacy demands on patients and address the need for healthcare professionals with these essential skills.30

Some members of the PPI panel felt that treatment plans were made without considering the patients’ opinions. Person-centred care incorporates and values patients’ perspectives, beliefs and autonomy and considers the person as a whole within the cultural context in which care is provided.31 Healthcare professionals involved in caring for patients with DFU should adopt a patient-centred approach to increase patient engagement and improve patient and clinical outcomes.

Social support

The findings of this PPI process support the use of social outlets, such as support groups/clubs for patients with DFU for their wellbeing. The PPI panel expressed the importance of increased levels of social engagement in their lives. They highlighted the need for both emotional and social support systems in conjunction with the management of their DFU. Within the UK, the concept of “Leg Clubs” is well-established as a support for people requiring lower limb management in a social environment.32 A Leg Club is a social model of care established to provide holistic treatment to people with chronic lower limb ulcerations. There is little robust evidence to correlate such a model with or suggest it for positive health outcomes. Therefore, more in-depth research is required to assess such an intervention.32 Nonetheless, the beneficial effects of social support in patients with chronic illness are widely known.3,34 Currently, no social support is provided to patients with DFU and specific social models of care of this type do not exist. This area of support warrants further exploration of the potential benefits for this population.

Holistic approach

It is well-recognised that DFU and its complications can significantly impact an individual’s wellbeing and spirituality, engraining feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness for the future.35 The PPI panel expressed concern about the lack of holistic approaches for people living with DFU. Furthermore, it is recognised that psychological support should be integrated into the care of people suffering from diabetes and DFU.5 Yet, psychologists and counsellors are not always readily accessible in the multi-disciplinary team, perhaps because of healthcare resource restrictions and budgetary implications. The panel suggested that support is required for psychological health and that viable options may take the form of counselling or spiritual or journaling support for individuals describing the positive impacts of yoga and journaling. The roles of counselling and spiritual support are well-recognised in increasing wellbeing in general and in populations with chronic disease. The role of journaling is also becoming increasingly recognised for its potential to decrease anxiety and increase the ability to deal with stressful events.36,37 This is an area that requires further research in those with lower limb wounds and more research is required on the role of counselling and spiritual support, specifically on this patient population.

Limitations

The limitations of this study relate to the small number of participants in the PPI panel (n=6) and restrictions on geographical location for recruiting panel members, which may have implications for the generalisability and transferability of findings. All individuals who took part in the PPI panel sessions attended treatment at one centre and therefore the views expressed may be reflective of the experiences of that one centre. Additionally, one-on-one sessions were required with panellists because of Covid-19 restrictions, which limited the ability to further validate statements, themes and sub-themes. These limitations were unfortunately unavoidable due to pandemic restrictions at the time of this study. Participants preferred meeting individually immediately after their scheduled appointment. Ideally, the PPI sessions would have taken place in a neutral venue outside of the clinical environment and in a group setting, such as in round-table discussions.

CONCLUSION

We set out to investigate the potential for the development of a wellbeing tool specifically for people living with DFU through PPI collaboration and engagement with patients. The opinions and views of the PPI panel support the need for research in this area. While being cognisant of the fact that the views presented emanated from just six individuals in one clinical site, our participants highlighted five key areas for consideration in future research and tool development: patient education, self-efficacy, health literacy and knowledge translation, social support and holistic support.

Further research in this area should comprehensively address the holistic elements of wellbeing to optimise outcomes for those with DFU and involve PPI initiatives. The development of an outcome tool for wellbeing and its subdomains is required to support further research in this area and establish the effectiveness of initiatives in areas such as self-management, health literacy and social outlets/clubs.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

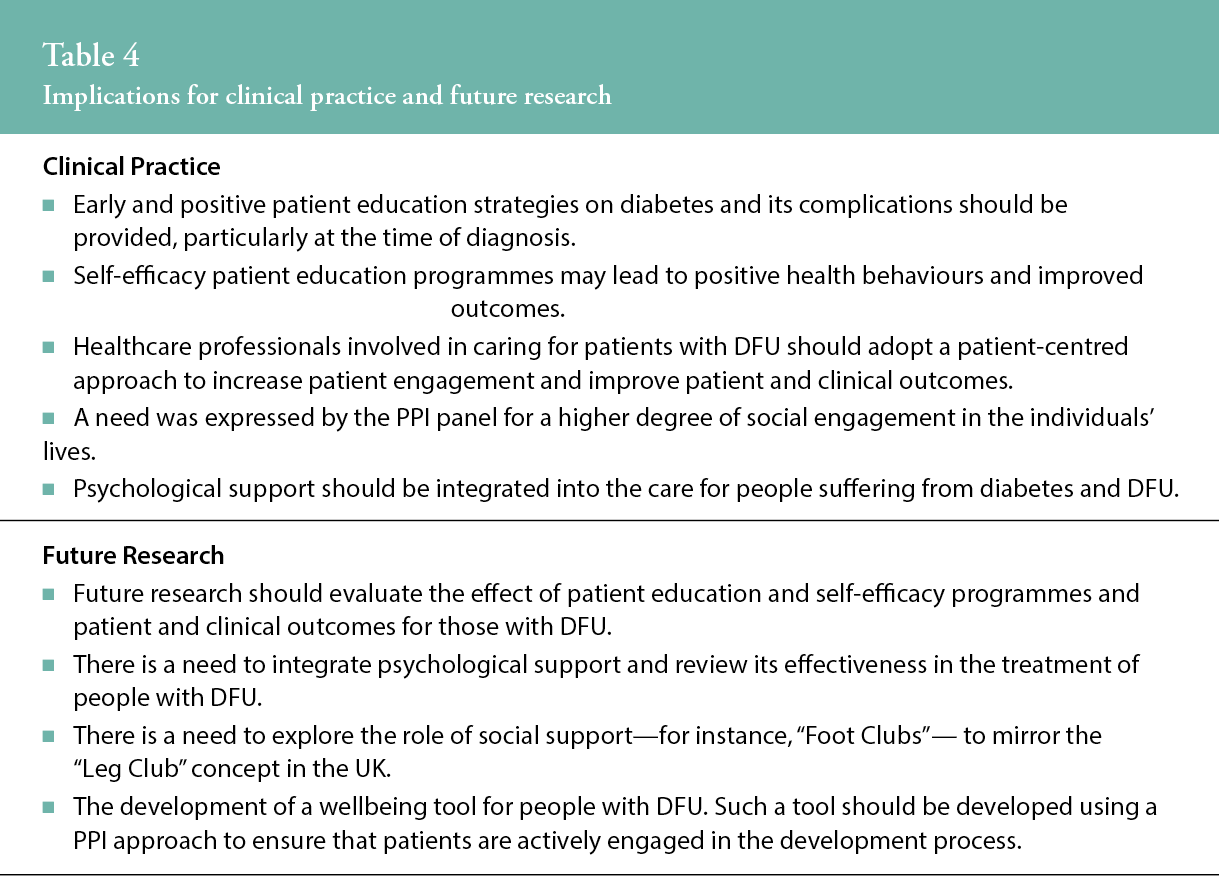

The implications for clinical practice are summarised in Table 4.

Key messages

- Optimising wellbeing for those living with DFU is a critical component of holistic patient management. Yet, there is currently no tool to measure wellbeing among this population.

- This patient and public involvement process sought patient and carer input in research—through a partnership approach—to help our research team develop specific research priorities regarding wellbeing in individuals with diabetic foot ulcers and generate ideas for a tool to measure the dimensions of wellbeing.

- The panel highlighted the need for clinician awareness of the multiple needs of patients’ well-being, and not just physical aspects.

- There is a need for early and positive education strategies regarding diabetes and its complications, particularly at the time of diagnosis.

- There is also a need for a higher grade of social engagement in individuals’ lives by recognising the role of emotional and social support in conjunction with the management of their condition.

Author(s)

Lauren Connell, MPhil,1,2, Claire MacGilchrist, PhD,1,2, Molly Smith, BSc,1,2, Caroline McIntosh, PhD.1,2.

1 Discipline of Podiatric Medicine, School of Health Sciences, NUI Galway, Galway, Ireland.

2 Alliance for Research and Innovation in Wounds, College of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, NUI Galway, Galway, Ireland.

Correspondence: caroline.mcintosh@nuigalway.ie

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- Cho NS, Karuranga JE, Huang S, da Rocha Fernandes Y, Ohlrogge JD, Malanda AW, et al. Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 2018; 138:271-81.

- McIntosh C, Ivory JD, Gethin G, MacGilchrist C. Optimising Wellbeing in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Journal of the European Wound Management Association, 2019:23-8.

- Zhang X, Norris SL, Gregg EW, Beckles G. Social support and mortality among older persons with diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2007; 33(2):273-81.

- Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA. Five-year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2020; 13:1-4.

- Schinckus L, Dangoisse F, Van den Broucke S, Mikolajczak M. When knowing is not enough: Emotional distress and depression reduce the positive effects of health literacy on diabetes self-management. Patient Education and Counseling. 2018; 101(2):324-30.

- Monami M, Longo R, Desideri CM, Masotti G, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. The diabetic person beyond a foot ulcer: healing, recurrence, and depressive symptoms. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2008; 98(2):130-6.

- International Consensus. Optimising wellbeing in people living with a wound. London; 2012.

- Gethin G, Ivory JD, Connell L, McIntosh C, Weller CD. External validity of randomized controlled trials of interventions in venous leg ulceration: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2019; 27:702-10.

- Sekhar MS, Thomas RR, Unnikrishnan MK, Vijayanarayana K, Rodrigues GS. Impact of diabetic foot ulcer on health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Seminars in Vascular Surgery. 2015; 28(3):165-71.

- Salomé GM, Pereira VR, Ferreira LM. Spirituality and subjective wellbeing in patients with lower-limb ulceration. Journal of wound care. 2013; 22(5):230-6.

- Connell L. Current Tools in Evaluating Wellbeing in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulceration (DFU) and Venous Leg Ulceration (VL): A Scoping Review with Public and Patient Involvement. Unpublished MPhil Thesis. NUI Galway: James Hardiman Library; 2020.

- Hayes H, Buckland S, Tarpey M. INVOLVE: Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. UK: NHS-National Institute for Health Research; 2012.

- Hoddinott P, Pollock A, O’Cathain A, Boyer I, Taylor J, Macdonald C, et al. How to incorporate patient and public perspectives into the design and conduct of research. 2018; 7:752.

- Hanley B, Staley K, Stewart D, Barber R. Qualitative research and patient and public involvement in health and social care research: What are the key differences? 2019.

- O’Regan M, Gethin G, O’Loughlin A, O’Connor G, Dineen S, Pandit A, et al. Public & patient involvement to guide research in wound care in an Irish context. A round table report. J Tissue Viability. 2020; 29(1):7-11.

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:42.

- Paton J, Abey S, Hendy P, Williams J, Collings R, Callaghan L. Behaviour change approaches for individuals with diabetes to improve foot self-management: a scoping review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2021; 14(1):1.

- Consensus International. Optimising wellbeing in people living with a wound. An expert working group review. Wounds International; 2012.

- Staniszewska SB, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K, Mockford C, Goodlad S et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem. 2017; 3:13.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3(2):77-101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2014; 9:26152.

- Abayomi JC, Charnley MS, Cassidy L, McCann MT, Jones J, Wright M, et al. A patient and public involvement investigation into healthy eating and weight management advice during pregnancy. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2020; 32:28-34.

- Nemcová J, Hlinková E. The efficacy of diabetic foot care education. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014; 23(5-6):877-82.

- Dorresteijn JAN, Kriegsman DMW, Assendelft WJJ, Valk GD. Patient education for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014; 12.

- Binning J, Woodburn J, Bus SA, Barn R. Motivational interviewing to improve adherence behaviours for the prevention of diabetic foot ulceration. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019; 35(2):e3105.

- McCleary-Jones V. Health literacy and its association with diabetes knowledge, self-efficacy and disease self-management among African Americans with diabetes mellitus. ABNF Journal. 2011; 22(2).

- Sharoni SKA, Abdul Rahman H, Minhat HS, Shariff Ghazali S, Azman Ong MH. A self-efficacy education programme on foot self-care behaviour among older patients with diabetes in a public long-term care institution, Malaysia: a Quasi-experimental Pilot Study. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(6):e014393.

- Wendling S, Beadle V. The relationship between self-efficacy and diabetic foot self-care. Journal of clinical & translational endocrinology. 2015; 2(1):37-41.

- Hadden K, Martin R, Prince L, Barnes CL. Patient health literacy and diabetic foot amputations. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2019; 58(5):877-9.

- Hadden KB. Health literacy training for health professions students. Patient Educ Couns. 2015; 98(7):918-20.

- Gethin G, Probst S, Stryja J, Christiansen N, Price P. Evidence for person-centred care in chronic wound care: A systematic review and recommendations for practice. J Wound Care. 2020; 29(Sup9b):S1-s22.

- Lindsay E. Leg clubs: a new approach to patient‐centred leg ulcer management. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2000; 2(3):139-41.

- Ghazaleh HA, Artom M, Sturt J. A systematic review of community Leg Clubs for patients with chronic leg ulcers. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2019; 20.

- Pruitt S, Epping-Jordan J. Preparing a global healthcare workforce. Chronic disease management. 2008; 38.

- de Jesus Pereira MT, Magela Salomé G, Guimarães Openheimer D, Cunha Espósito VH, Aguinaldo de Almeida S, Masako Ferreira L. Feelings of powerlessness in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Wounds. 2014; 26(6):172-7.

- Smyth MS, Johnson JA, Auer BJ, Lehman E, Talamo G, Sciamanna CN. Online positive affect journaling in the improvement of mental distress and well-being in general medical patients with elevated anxiety symptoms: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 2018; 5(4).

- Ullrich P, Lutgendorf SK. Journaling about stressful events: Effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Annals of Behavioural Medicine 2002; 24, 244-259.