Volume 22 Number 3

Survey of physicians’ and nurses’ needs and expectations regarding a multidisciplinary wound clinic

Majchrzak, Karine, Bobbink, Paul, Probst, Sebastian

Keywords Wound care; chronic wounds; multidisciplinary team; health services

DOI 10.35279/jowm202110.04

Abstract

Aim To describe needs and expectations from healthcare professionals while setting up a multidisciplinary wound clinic.

Methods An online survey was conducted in a 190-bed hospital in Western Switzerland from the 2nd to 15th of June 2020. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data.

Results A total of 166 healthcare professionals (118 nurses, 48 physicians) participated in the survey. Half of the participants (48%) saw the importance of setting up a wound clinic as 47% were taking care of wounds daily. Almost all participants (83 %) disclosed having no educational wound care background and half of them (54%) indicated having no skills and knowledge in wound management. The main aetiologies treated in a specialist centre should be diabetic foot, leg and pressure ulcers, then malignant wounds. It is expected a specialist clinic cares for complex or non-healing wounds. Furthermore, 48% of participants wished a multidisciplinary expert approach with a common protocol to guarantee a continuity of care. The wound centre should also have an educational role, essential in maintaining up-to-date practice.

Conclusions and implications for clinical practice In conclusion, a wound clinic should have a multidisciplinary specialist approach while ensuring evidence-based and uniform practices to provide a person-centred care. Furthermore, further-education must be offered.

INTRODUCTION

Providing better care for patients with chronic wounds is a challenge to healthcare professionals. Wounds affect a large proportion of the population in developed countries, with an incidence rate reaching as high as 2%.1,2 In the United Kingdom, the annual costs devoted to wound care are estimated to be £8.3 billion3, as care is complex, patient-centred and usually provided by a dedicated team.4,5

A multidisciplinary team approach is crucial when treating wounds, and doing so implies a reliance on knowledge and expertise from different specialties.6 This approach is beneficial to the patient, the healthcare provider and the health institution.5 For example, studies have shown that multidisciplinary care provided to patients suffering from diabetic foot ulcers resulted in positive outcomes with reduced amputation and death rates, shorter-length hospital stays, increased quality of life and better healing rates.7,8

A recent systematic review concluded that the implementation of a multidisciplinary care team’s amputation prevention programme can result in an amputation rate reduction of 39–56%.9 These prevention programmes may also overcome the negative effects of neighbourhood socioeconomic deprivation that are frequently described in the diabetic population.10 Care algorithms and clinical pathways are key tools for ensuring success in reducing diabetic foot amputations11 and increasing amputation-free survival for chronic limb ischemia patients.12 Other benefits of such programmes include improved surgical outcomes and low pressure ulcer recurrence rates and readmissions.13 Patients treated in the outpatient wound clinics of specialised centres benefit equally from these approaches.14,15 Wound centres that collaborate in a partnership with hospitals have easier access to these hospitals’ infrastructures and resources, and to specialists and ancillary services16 with clear financial advantages.17

In the French-speaking part of Switzerland, only a few hospitals offer patients dedicated multidisciplinary wound care on an outpatient basis. The aim of this survey is to describe the needs and expectations of healthcare professionals in a private hospital in the western part of Switzerland with regard to the establishment of a multidisciplinary wound clinic.

METHODS

An online survey was conducted from 2–15 June 2020 in a private hospital in western Switzerland. A survey link was sent via two online mailing lists to 353 nurses and 182 physicians. Online surveys have provided unique and safe opportunities for research in the Covid-19 era. This is because many conventional methods for obtaining data have not been feasible during the pandemic.18 Additionally, the survey design is anonymous, cost-effective and easy to complete.19

Based on a literature review20, different items encompassing the reasons to contact a wound centre and its educational and preventive purposes were used to develop a questionnaire to describe the importance of healthcare professionals’ (HCP) needs and expectations when establishing a multidisciplinary wound clinic.

The survey was created online using Lime Survey and organised into three sections encompassing a total of 15 questions. The first section was related to the healthcare provider’s general information, such as activities, affiliation and wound care background. The second section addressed their current clinical practices for wound management in terms of frequency, types of wounds, expertise and the reasons why they seek advice from emergency department-affiliated wound specialist nurses. The third section focused on the HCPs’ perceptions of the impact of the establishment of a multidisciplinary wound clinic. Participants’ opinions were collected with the help of a four-point Likert scale (from ’never’ to ‘very often’). It clarified the types of wounds (leg ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers, traumatic wounds, burns, surgical and malignant fungating wounds) and the types of services needed (expert care, multidisciplinary council, common wound protocol, wound dressing). Closed binary questions were used to identify the usefulness of a wound centre and its educational and preventive purposes. The final two questions were open-ended, allowing the participants to elaborate on their specific needs and to add comments about wound care practices in the hospital.

Survey participation was on a voluntary basis and eligibility criteria included every queried nurse and physician working in the hospital, regardless of their specialty and outpatient/inpatient activity. Medical residents considered temporary employees were not included. Informed consent was assumed by the voluntary completion of the questionnaire.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data. The last two sets of answers, relating to the HCPs’ needs and comments about wounds, were analysed using qualitative thematic analysis.

RESULTS

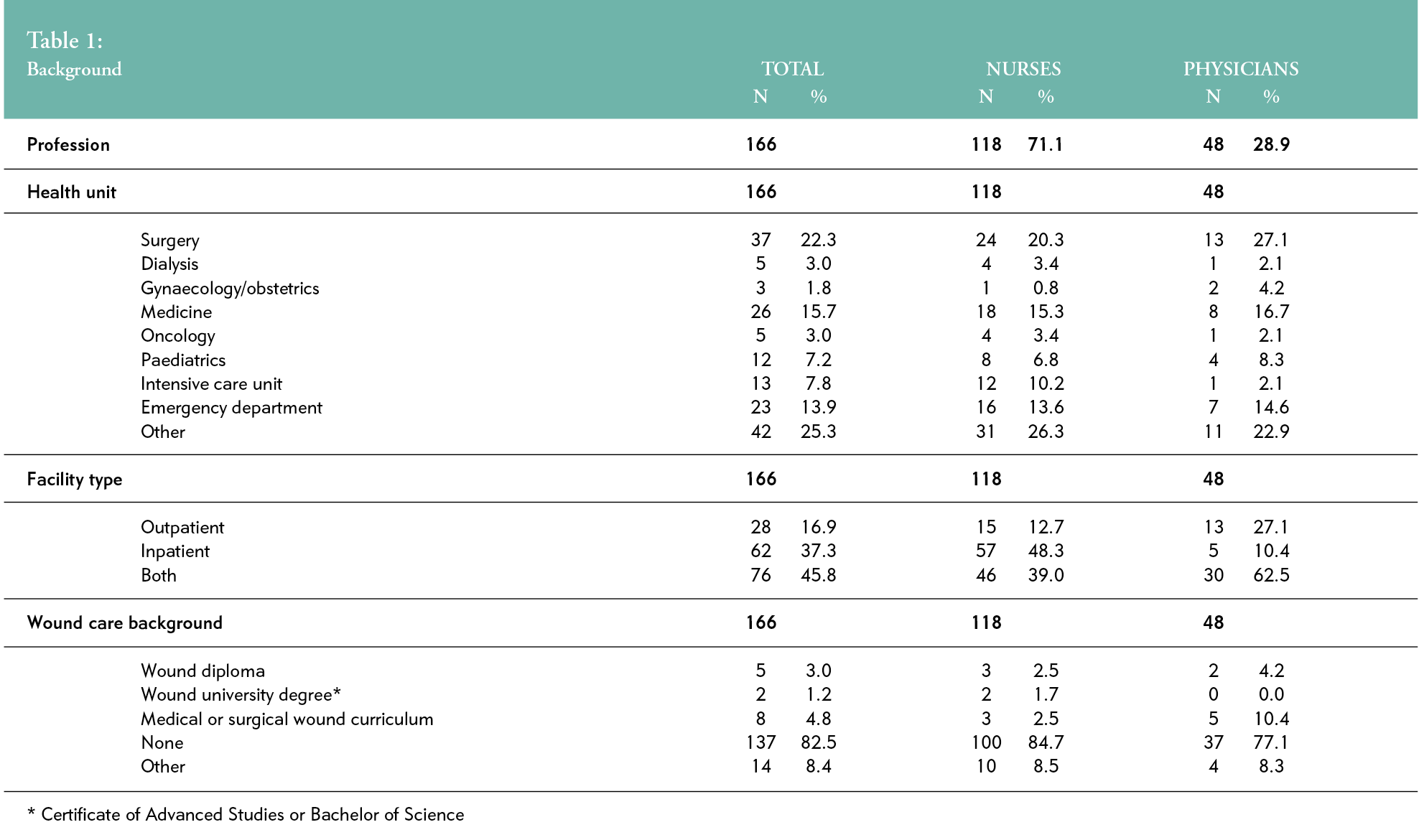

Out of 535 HCPs, 166 completed the survey (response rate: 31%); 118 were nurses (71%) and 48 were physicians (29%). Participants’ departmental affiliations were as follows: surgery (n=37, 22%), internal medicine (n=26, 16%), medical outpatient specialties (n=19, 13%), emergency (n=23, 14%), intensive care unit (n=13, 8%) and paediatrics (n=12, 7%). Almost half of the participants (n=76, 46%) served both outpatients and inpatients, and 17% (n=28) dealt only with outpatient activities. Most (n=137, 83%) specified having no wound education (Table 1).

Wound care skills and knowledge

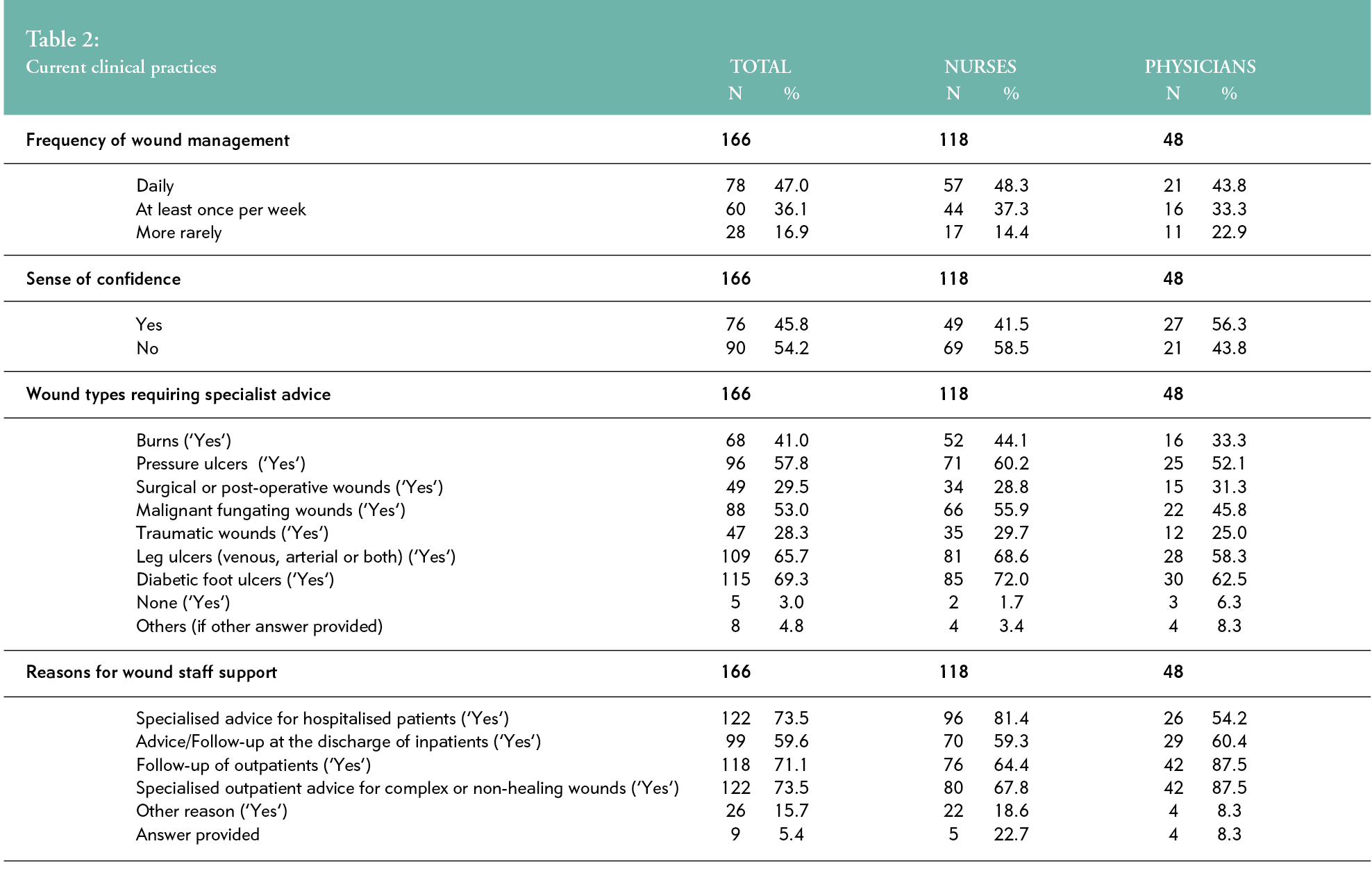

Nearly half of the HCPs (n=78, 47%) provided daily care to wound patients, whereas 17% (n=28) indicated less than one such encounter per week. Almost half (n=76, 46%) of the participants noted need to advocate for better skills and knowledge for wound management. Most reported that they require wound specialist support when taking care of complex wounds, such as diabetic foot (n=115, 69%), leg ulcers (n=109, 66%), pressure ulcers (n=96, 58%) or malignant fungating wounds (MFW) (n=88, 53%) (Table 2).

Multidisciplinary wound centre development needs

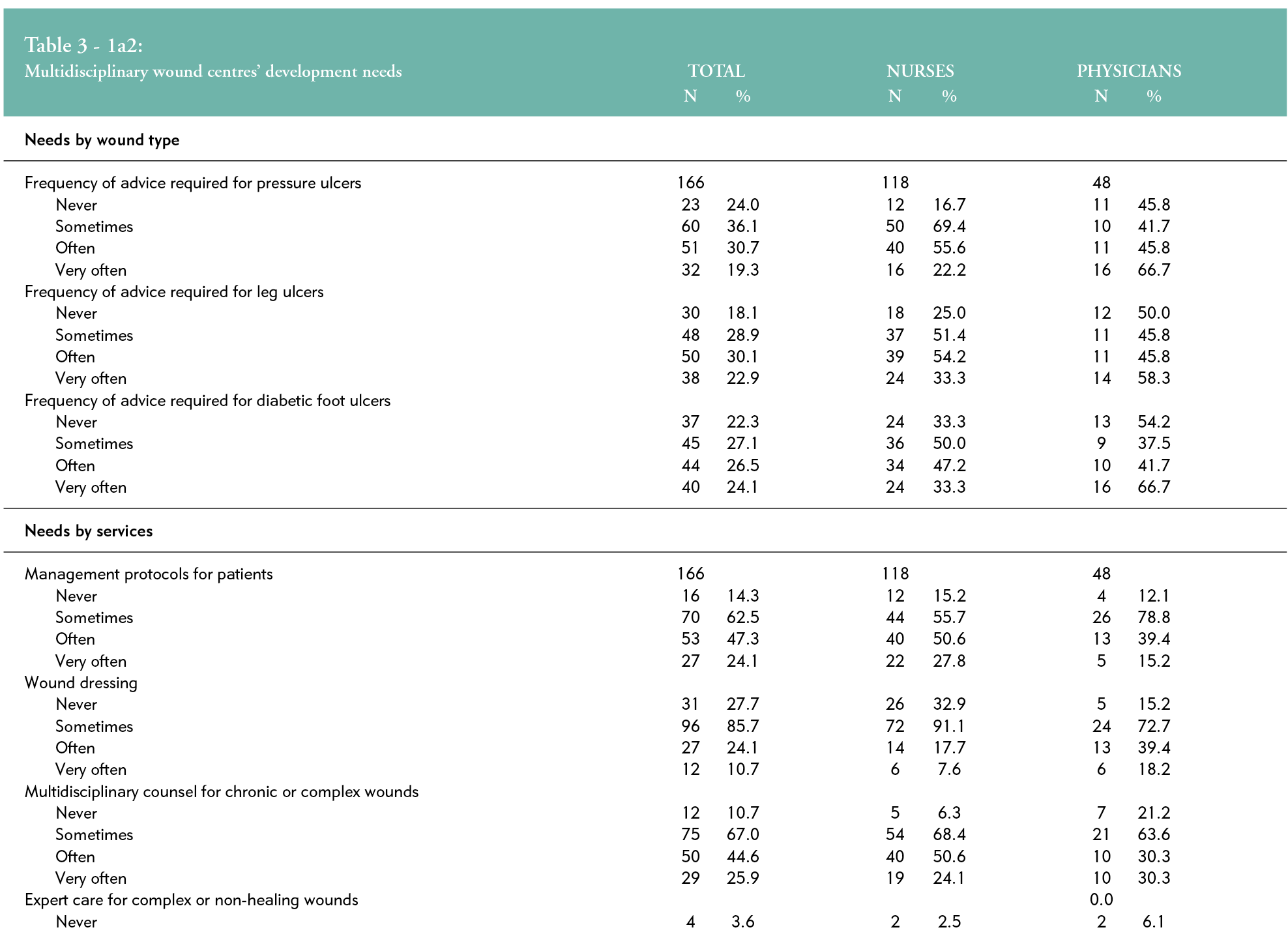

The appeals to a wound centre were reported in 53%, 51%, 50% and 38% of cases, when dealing with leg ulcers (n=88), diabetic foot ulcers (n=84), pressure ulcers (n=83) and oncological wounds (n=63), respectively.

Specialised advice for complex or non-healing wounds was highly requested by as many as 30% of HCPs (n=49). Half of them request the establishment of a wound protocol (n=80) or a multidisciplinary consultation (n=79, 48%) ‘often’ or ‘very often’, but help applying a dressing was ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ necessary in 75% of cases (n=127) (Table 3).

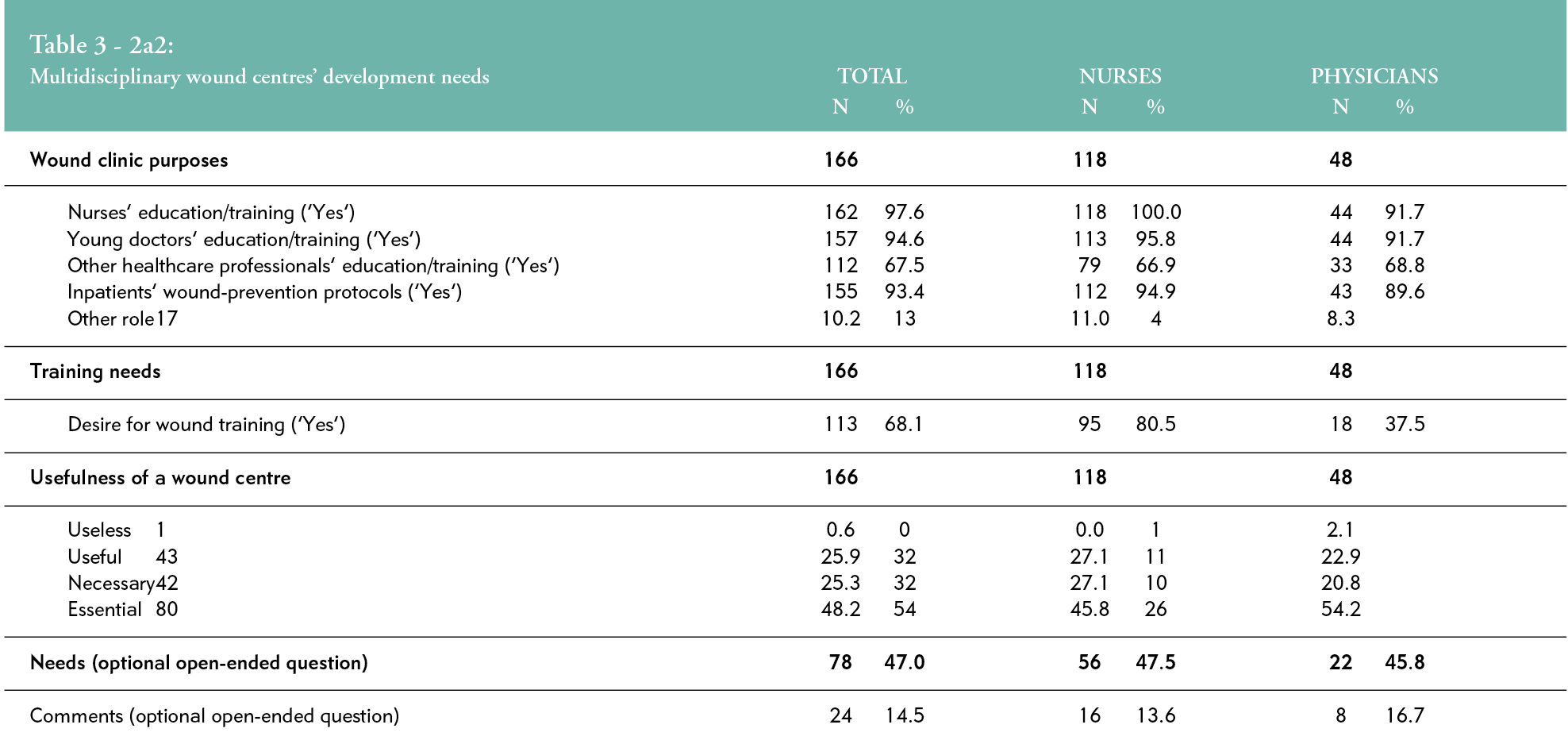

Sixty-eight percent (n=113) of respondents declared a desire to attend a training course in wound management. An ideal wound centre would play an educational role for nurses (n=162, 98%) and junior physicians (n=157, 95%) and a preventive role in establishing inpatient protocols (n=155) for more than 93% of the participants.

A multidisciplinary wound centre is seen as ‘essential’ by 48% (n=80) of the HCPs.

Forty-seven percent (n=78) of HCPs expressed a need for wound treatment protocols, inpatient care protocols regarding dressings and other wound devices, continuous medical training and updates of wound management knowledge. Respondents expected better follow-up with wound patients and specialised counselling or therapy for complex, non-healing, specific wounds such as child burns, post-operative infected wounds and ischemic arterial wounds. Multidisciplinary collaboration with better communication was also advocated.

Fourteen percent (n=24) underlined the need for around-the-clock availability of the wound staff and confirmed their strong interest in a project to imple-ment a wound centre.

Eighty percent (n=95) of nurses were in favour of a post-graduate education programme in wound management, compared to 37.5% (n=18) of physicians (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This online survey aimed to describe the needs and expectations of HCPs from a multidisciplinary wound clinic. We used a short questionnaire with both closed- and open-ended questions based on a Likert scale with pre-conceived categories, which is known as a recognised bias.21 However, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, this was the simplest and most feasible way to ascertain both physicians’ and nurses’ needs and expectations. In hopes of obtaining a higher response rate, we used an email reminder and excluded trainees.22,23 Nevertheless, another limitation of the survey was that the overall response rate remained low (31%). The short deadline for the completion of the questionnaire, or the content and aim of the survey could, have also limited24 the participants’ replies.

Our results showed differences between the physicians’ and the nurses’ needs, though both groups expressed the same expectations and goals regarding wound care and the roles of a wound clinic, in both outpatient and inpatient settings.

This survey also highlighted how commonly wounds are encountered, as only 17% of the HCPs reported dealing with wound patients no more than once per week. Evidence shows that providing care to wound patients will become increasingly important in the future, as the prevalence of chronic wounds is rising.2 The most prevalent and common forms of chronic wounds today are venous leg ulcers, followed by pressure ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers, which are complicated for HCPs to treat.25,26 Our findings are in alignment with these data, suggesting the need for specialised advice for chronic wounds. Our results also demonstrated that the number of patients with an MFW is more frequent than that described in the literature. In Switzerland, a prevalence of 6.6% has been reported.27 The high incidence of MFW in our survey is related to the more challenging management of MFW28 and the nearby oncological centre, which is part of the hospital.

Wound care skill and knowledge

Exploring HCPs’ skills and knowledge of wounds is helpful for understanding their needs and expectations when setting up a wound clinic. Regardless of the participants’ different specialty backgrounds, which seem representative of all wards and services that a hospital can provide, a large majority expressed having no wound education, and half of them had no confidence in their skills to manage wounds. Our findings are in alignment with other studies pointing out that medical students’29 and nurses’ curricula are lacking when it comes to wound care.26,30 Lupon et al. demonstrated in their survey of 711 assistant physicians that 79% had received no training in wound healing, and 94% mentioned having insufficient wound care knowledge.31 This lack is also reported for nurses.32 In clinical practice, skills and knowledge are learned from colleagues.33 The current tendency seems to provide a wider range of educational interventions and continuous training opportunities, which is effective for chronic wound management.34 Hence, different national societies throughout Europe35, together with universities, have implemented wound care curricula into their existing courses of studies to enhance the wound care skills and knowledge of future physicians.29,36 The European Wound Management Association (EWMA) for example, has developed European wound curricula for physicians37 and nurses38,39, with the aim of providing students with theoretical and practical skills to support applicable decision-making. However, evidence suggests that educational interventions improved the knowledge of junior doctors in wound assessment and dressing selection, but did not improve their lack of confidence in this area.40

Multidisciplinary wound centre development needs

Because the care of patients with a chronic or non-healing wound is complex, 60% of HCPs frequently ask for a specialised consultation from a wound team. Evidence demonstrates that wound care must be provided by wound specialists, those with wound care skills, experience and qualifications in adapted settings14,20,41,42, as expertise makes it possible to address the complexity of chronic wound management and the patient’s needs.43 Adequate knowledge of chronic wound care44, specialised training for healthcare practitioners managing chronic wounds45 and constant briefings and updating of knowledge, especially for malignant fungating wounds46, are needed to carry out safe, evidence-based, high-quality and cost-effective care.47

In our study, HCPs outlined the need for taking advice from a multidisciplinary team, which highlights the need for more communication and collaboration among the different specialists in a hospital. Additionally, they mentioned the need for better availability of the wound care staff. These findings are in alignment with those of the EWMA Wound Centre Endorsement Project, which has highlighted the importance of emphasising the multidisciplinary approach to avoid both the discontinuity of care and potential harm to patients. No single discipline is thought able to independently meet the multiplicity of needs for wound patients.20 Moreover, patient-centred care is achieved by the complementarity of the different disciplines involved in the team.5 The composition and size of the multidisciplinary wound team are not well defined in the literature and are often variable.42,48–50 A strong commitment and passion for wound care16, mutual respect, closed-loop communication and trust among the members51, and their ability to take on difficult problems at any given time, are important.50

The need for uniform wound care practices in standardising the care protocols across services is another key theme expressed by study participants. It is expected that a wound centre will provide wound prevention and treatment protocols, including explanations of the indications for different wound dressings and devices. Evidence demonstrates that nurses experience difficulties in obtaining a standardisation of wound care protocols because of the multidisciplinary nature of wound care providers and the wide variety of wound care products.52 Furthermore, there are a variety of guidelines depending on a chronic wound’s aetiology (arterial, venous, diabetic foot and pressure ulcers), and a lack of evidence for wound-healing products’ efficacy, as demonstrated by a series of inconclusive Cochrane reviews.53–59 National guidelines are necessary to support wound teams60, and our results highlight their absence in Switzerland.

Finally, regarding the small number of nurses who have already attended a wound programme and their lack of confidence in their skills and knowledge in wound care, as previously described, almost all participating nurses expressed a willingness to be trained in the future. This result confirms the interest of nurses in wound care and the possibility of implementing a wound care training educational programme in our hospital. Our findings are in alignment with a previous qualitative study reporting that HCPs are committed to delivering best practices in wound care and that effective, patient-focused, evidence-based wound care involves having a healthcare system with a clear mandate to ensure that wound care is a priority.61 When setting up a wound clinic, a higher value could be placed on wound management; wound education for both nurses and doctors; patient-centred care and improving patients’ outcomes, such as satisfaction and quality of life.4,62

CONCLUSION

Our healthcare professionals expect a wound clinic that provides care, treatment and prevention protocols for chronic wound patients. By applying a multidisciplinary specialist approach, such a clinic could ensure uniform practices and continuity of care, to enable a person-centred approach to care. Further continuing education should be offered to improve HCPs’ wound care skills and the knowledge of nurses and physicians, to guarantee up-to-date and evidence-based practices.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Multidisciplinary cooperation with effective communication, availability and expertise while managing chronic wounds are the main expectations of our healthcare professionals regarding a wound centre. Implementation of a wound clinic could also enhance outpatient and inpatient continuity of care and person-centred wound care.

Nurses and physicians need more wound care education, at both the undergraduate and professional levels, to improve their skills and knowledge and to help them provide more evidence-based wound care.

There is also a need to develop national guidelines targeted at chronic wounds to help HCPs and guarantee a standardised approach to their prevention, decision-making, treatment and dressing choices.

KEY MESSAGES

- As prevalence and complexity of chronic wounds are increasing, a patient-centred wound management within a multidisciplinary approach is crucial to improve patient’s outcomes.

- This survey describes needs and expectations of healthcare professionals, while setting up a multidisciplinary wound clinic.

- Nurses and physicians need care, treatment and prevention protocols for chronic wound patients, mainly with leg, diabetic foot, and pressure ulcers.

They expect a multidisciplinary cooperation with expertise in wound products and management while ensuring uniform practices and continuity of care. - Further wound education for nurses and physicians is essential.

Author(s)

Majchrzak, Karine1, Bobbink, Paul2, Probst, Sebastian2,3,4

1La Tour Hospital, Meyrin, Switzerland

2HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Geneva, Switzerland

3University Hospital Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

4Faculty of Medicine Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

Correspondence: Karine.majchrzak@latour.ch

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- Howell RS, Kohan LS, Woods JS, Criscitelli T, Gillette BM, Donovan V, et al. Wound care center of excellence: A process for continuous monitoring and improvement of wound care quality. Adv Skin Wound Care 2018; 31(5):204–3. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000531354.39232.70

- Martinengo L, Olsson M, Bajpai R, Soljak M, Upton Z, Schmidtchen A, et al. Prevalence of chronic wounds in the general population: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Epidemiol 2019; 29:8–15. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.10.005

- Guest JF, Fuller GW, Vowden P. Cohort study evaluating the burden of wounds to the UK’s National Health Service in 2017/2018: Update from 2012/2013. BMJ Open 2020; 10(12):e045253. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045253

- Gethin G, Probst S, Stryja J, Christiansen N, Price P. Evidence for person-centred care in chronic wound care: A systematic review and recommendations for practice. J Wound Care 2020; 29(Sup9b):S1–22. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.Sup9b.S1

- Moore Z, Butcher G, Corbett LQ, McGuiness W, Snyder RJ, van Acker K. Exploring the concept of a team approach to wound care: Managing wounds as a team. J Wound Care 2014; 23 Suppl 5b:S1–38. doi:10.12968/jowc.2014.23.Sup5b.S1

- Choi BCK, Pak AWP. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clin Investig Med Clin Exp 2006; 29(6):351–64.

- Buggy A, Moore Z. The impact of the multidisciplinary team in the management of individuals with diabetic foot ulcers: A systematic review. J Wound Care 2017;26(6):324-339. doi:10.12968/jowc.2017.26.6.324

- Huizing E, Schreve MA, Kortmann W, Bakker JP, de Vries JPPM, Ünlü Ç. The effect of a multidisciplinary outpatient team approach on outcomes in diabetic foot care: A single center study. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2019; 60(6):662–71. doi:10.23736/S0021-9509.19.11091-9

- Albright RH, Manohar NB, Murillo JF, Kengne LAM, Delgado-Hurtado JJ, Diamond ML, et al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care teams in reducing major amputation rate in adults with diabetes: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020; 161:107996. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107996

- Hicks CW, Canner JK, Mathioudakis N, Sherman RL, Hines K, Lippincott C, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage is not associated with wound healing in diabetic foot ulcer patients treated in a multidisciplinary setting. J Surg Res 2018; 224:102–11. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2017.11.063

- Musuuza J, Sutherland BL, Kurter S, Balasubramanian P, Bartels CM, Brennan MB. A systematic review of multidisciplinary teams to reduce major amputations for patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg 2020; 71(4):1433–46.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2019.08.244

- Chung J, Modrall JG, Ahn C, Lavery LA, Valentine RJ. Multidisciplinary care improves amputation-free survival in patients with chronic critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2015; 61(1):162-169.e1 doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2014.05.101

- Tadiparthi S, Hartley A, Alzweri L, Mecci M, Siddiqui H. Improving outcomes following reconstruction of pressure sores in spinal injury patients: A multidisciplinary approach. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 2016; 69(7):994–1002. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.02.016

- Gottrup F, Holstein P, Jørgensen B, Lohmann M, Karlsmar T. A new concept of a multidisciplinary wound healing center and a national expert function of wound healing. Arch Surg Chic Ill 1960 2001; 136(7):765–72. doi:10.1001/archsurg.136.7.765

- Coerper S, Schäffer M, Enderle M, Schott U, Köveker G, Becker HD. The wound care center in surgery: An interdisciplinary concept for diagnostic and treatment of chronic wounds. Chir Z Alle Geb Oper Medizen 1999; 70(4):480–4. doi:10.1007/s001040050676

- Kim PJ, Evans KK, Steinberg JS, Pollard ME, Attinger CE. Critical elements to building an effective wound care center. J Vasc Surg 2013; 57(6):1703–9. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.11.112

- Attinger CE, Hoang H, Steinberg J, Couch K, Hubley K, Winger L, et al. How to make a hospital-based wound center financially viable: The Georgetown University Hospital model. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 111(2 Suppl):S92–7. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.044

- Wright KB. Researching internet-based populations: Advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. J Comput-Mediat Commun 2005; 10(3): 00–00. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00259.x

- Buchanan EA, Hvizdak EE. Online survey tools: Ethical and methodological concerns of human research ethics committees. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2009; 4(2):37–48. doi:10.1525/jer.2009.4.2.37

- Gottrup F, Pokorná A, Bjerregaard J, Vuagnat H. Wound centres-how do we obtain high quality? The EWMA wound centre endorsement project. J Wound Care. 2018; 27(5):288–95. doi:10.12968/jowc.2018.27.5.288

- Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care 2003; 15(3):261–6. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzg031

- Cook JV, Dickinson HO, Eccles MP. Response rates in postal surveys of healthcare professionals between 1996 and 2005: An observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9:160. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-9-160

- Mol CV. Improving web survey efficiency: The impact of an extra reminder and reminder content on web survey response. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2017; 20(4):317–27. doi:10.1080/13645579.2016.1185255

- Fan W, Yan Z. Factors affecting response rates of the web survey: A systematic review. Comput Hum Behav 2010; 26(2):132–9. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.10.015

- Makrantonaki E, Wlaschek M, Scharffetter‐Kochanek K. Pathogenesis of wound healing disorders in the elderly. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2017; 15(3):255–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.13199

- Schaarup C, Pape-Haugaard LB, Hejlesen OK. Models used in clinical decision support systems supporting healthcare professionals treating chronic wounds: Systematic literature review. JMIR Diabetes 2018; 3(2):e11. doi:10.2196/diabetes.8316

- Probst S, Arber A, Faithfull S. Malignant fungating wounds: A survey of nurses’ clinical practice in Switzerland. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2009; 13(4):295–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2009.03.008

- Rupert KL, Fehl AJ. A patient-centered approach for the treatment of fungating breast wounds. J Adv Pract Oncol 2020; 11(5):503–10. doi:10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.5.6

- Kamath P, Agarwal N, Salgado CJ, Kirsner R. Wound healing elective: An opportunity to improve medical education curriculum to better manage the increasing burden of chronic wounds. Dermatol Online J 2019; 25(5) :13030/qt3qv3b5fb..

- Gottrup F. Optimizing wound treatment through health care structuring and professional education. Wound Repair Regen 2004; 12(2):129–33. doi:10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012204.x

- Lupon E, Turrian U, Malloizel-Delaunay J, Bura-Rivière A, Grolleau JL. Medical residents and wound healing: A French national survey. J Med Vasc 2019; 44(5):324–30. doi:10.1016/j.jdmv.2019.06.003

- Welsh L. Wound care evidence, knowledge and education amongst nurses: A semi-systematic literature review. Int Wound J 2018; 15(1):53–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12822

- Haram R, Ribu E, Rustøen T. The views of district nurses on their level of knowledge about the treatment of leg and foot ulcers. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs 2003; 30(1):25–32. doi:10.1067/mjw.2003.4

- Martinengo L, Yeo NJY, Markandran KD, Olsson M, Kyaw BM, Car LT. Digital health professions education on chronic wound management: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2020; 104:103512. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103512

- Gottrup F. Education in wound management in Europe with a special focus on the Danish model. Adv Wound Care 2012; 1(3):133–7. doi:10.1089/wound.2011.0337

- Cervero RM, Gaines JK. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: An updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2015; 35(2):131–8. doi:10.1002/chp.21290

- European Union of Medical Specialists. Wound curriculum of physicians. Published online 2018. https://ewma.org/what-we-do/education/ewma-wound-curricula/wound-curriculum-for-physicians

- Holloway S, Pokorná A, Janssen A, Ousey K, Probst S. Wound curriculum for nurses: Post-registration qualification wound management — European qualification framework level 7. J Wound Care 2020; 29(Sup7a):S1–39. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.Sup7a.S1

- Probst S, Holloway S, Rowan S, Pokornà A. Wound curriculum for nurses: Post-registration qualification wound management — European qualification framework level 6. J Wound Care 2019; 28(Sup2a):S1–33. doi:10.12968/jowc.2019.28.Sup2a.S1

- Catton H, Geoghegan L, Goss AJ, Adami RZ, Rodrigues JN. Foundation doctor knowledge of wounds and dressings is improved by a simple intervention: An audit cycle-based quality improvement study. Ann Med Surg 2020; 51:24–7. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2020.01.004

- Iakova M, Charbonneau L, Bial L. Guidelines for the recognition of wound care centers. Published online in the Swiss association for wound care. 2020 Jan 9;8. https://www.safw-romande.ch/

- Seaton PCJ, Cant RP, Trip HT. Quality indicators for a community-based wound care centre: An integrative review. Int Wound J 2020; 17(3):587–600. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13308

- Woo KY, Wong J, Rice K, Coelho S, Haratsidis E, Teague L, et al. Patients’ and clinicians’ experiences of wound care in Canada: A descriptive qualitative study. J Wound Care 2017; 26(Sup7):S4–13. doi:10.12968/jowc.2017.26.Sup7.S4

- de Leon J, Bohn GA, DiDomenico L, Fearmonti R, Gottlieb HD, Lincoln K, et al. Wound care centers: Critical thinking and treatment strategies for wounds. Wounds Compend Clin Res Pract 2016; 28(10):S1–23.

- Dhar A, Needham J, Gibb M, Coyne E. The outcomes and experience of people receiving community-based nurse-led wound care: A systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2020; 29(15–16):2820–33. doi:10.1111/jocn.15278

- Tsichlakidou A, Govina O, Vasilopoulos G, Kavga A, Vastardi M, Kalemikerakis I. Intervention for symptom management in patients with malignant fungating wounds - a systematic review. J Balk Union Oncol 2019; 24(3):1301–8.

- Kielo E, Suhonen R, Salminen L, Stolt M. Competence areas for registered nurses and podiatrists in chronic wound care, and their role in wound care practice. J Clin Nurs 2019; 28(21–22):4021–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14991

- Abrahamyan L, Wong J, Pham B, Trubiani G, Carcone S, Mitsakakis N, et al. Structure and characteristics of community-based multidisciplinary wound care teams in Ontario: An environmental scan. Wound Repair Regen 2015; 23(1):22–9. doi:10.1111/wrr.12241

- Flores AM, Mell MW, Dalman RL, Chandra V. Benefit of multidisciplinary wound care center on the volume and outcomes of a vascular surgery practice. J Vasc Surg 2019; 70(5):1612–9. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2019.01.087

- Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Steinberg JS, Evans KK, Akbari C, Mitnick CDB, et al. Building a multidisciplinary hospital-based wound care center: Nuts and bolts. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016; 138(3 Suppl):241S–S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002648

- Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J 2014; 90(1061):149–54. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168

- Jiang Y, Xia L, Jia L, Fu X. Survey of wound-healing centers and wound care units in China. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2016; 15(3):274–9. doi:10.1177/1534734614568667

- Broderick C, Pagnamenta F, Forster R. Dressings and topical agents for arterial leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 1:CD001836. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001836.pub4

- Dumville JC, Gray TA, Walter CJ, Sharp CA, Page T, Macefield R, et al. Dressings for the prevention of surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 2016(12). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003091.pub4

- Liu Z, Dumville JC, Hinchliffe RJ, Cullum N, Game F, Stubbs N, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy for treating foot wounds in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 10:CD010318. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010318.pub3

- Norman G, Westby MJ, Rithalia AD, Stubbs N, Soares MO, Dumville JC. Dressings and topical agents for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 6:CD012583. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012583.pub2

- Ramasubbu DA, Smith V, Hayden F, Cronin P. Systemic antibiotics for treating malignant wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 8:CD011609. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011609.pub2

- Walker RM, Gillespie BM, Thalib L, Higgins NS, Whitty JA. Foam dressings for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;10:CD011332. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011332.pub2

- Westby MJ, Dumville JC, Soares MO, Stubbs N, Norman G. Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 6:CD011947. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011947.pub2

- Gottrup F. Organization of wound healing services: The Danish experience and the importance of surgery. Wound Repair Regen 2003; 11(6):452–7. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11609.x

- Kuhnke JL, Keast D, Rosenthal S, Evans RJ. Health professionals’ perspectives on delivering patient-focused wound management: A qualitative study. J Wound Care 2019; 28(Sup7):S4–13. doi:10.12968/jowc.2019.28.Sup7.S4

- Boersema GC, Smart H, Giaquinto-Cilliers MGC, Mulder M, Weir GR, Bruwer FA, et al. Management of nonhealable and maintenance wounds: A systematic integrative review and referral pathway. Adv Skin Wound Care 2021; 34(1):11–22. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000722740.93179.9f