Volume 23 Number 2

Skin tears anno 2022: An update on definition, epidemiology, classification, aetiology, prevention and treatment

Hanne Van Tiggelen, Dimitri Beeckman

Keywords treatment, prevention, skin tears, epidemiology, Aetiology, classification, state of the science

DOI 10.35279/jowm2022.23.02.09

INTRODUCTION

People with skin vulnerability are at increased risk for a range of skin injuries, with skin tears being one of the most common conditions.1 Throughout life, there are periods of increased skin vulnerability, making people more susceptible to a variety of skin injuries.2 The aim of this article is to provide a review of the scant but emerging evidence base on the epidemiology, aetiology, classification, prevention and treatment of skin tears.

1. DEFINITION AND IMPACT

The International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP) advocates a universal taxonomy and defines skin tears as ‘traumatic wounds caused by mechanical forces, including removal of adhesives. Severity may vary by depth (not extending through the subcutaneous layer)’.3 Although skin tears can occur in any anatomical location, they are particularly common on the extremities, such as the upper and lower limbs, or the dorsal aspect of the hands.4 Skin tears are reported in all healthcare settings and in all age groups, but are most common in the elderly, neonates and the critically and chronically ill.5

Although skin tears are acute wounds that have the potential to heal through primary intention, they are at high risk of developing into chronic wounds if improperly treated.6 Individuals suffering from wounds that are difficult to heal are vulnerable to prolonged pain, emotional distress, embarrassment, infection and decreased quality of life.4 Conducting qualitative studies that examine patient experiences and the impact of skin tears on physical, psychological and social functioning is strongly recommended.3 From a health economics perspective, skin tears can result in high labour and material costs, increased caregiver workload and prolonged hospital stays.7,8

2. AN UPDATE ON EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although largely preventable, skin tears are considered common wounds with prevalence and incidence rates very similar to those of pressure ulcers.9,10,11,12 To date, only a limited number of studies have examined the prevalence and incidence of skin tears in different patient populations, healthcare settings and countries. Prevalence reflects the number of existing cases of a disease or injury at a specific point in time. Incidence refers to the number of new cases of a disease or injury over a specified period of time.13,14

2.1.Prevalence of skin tears

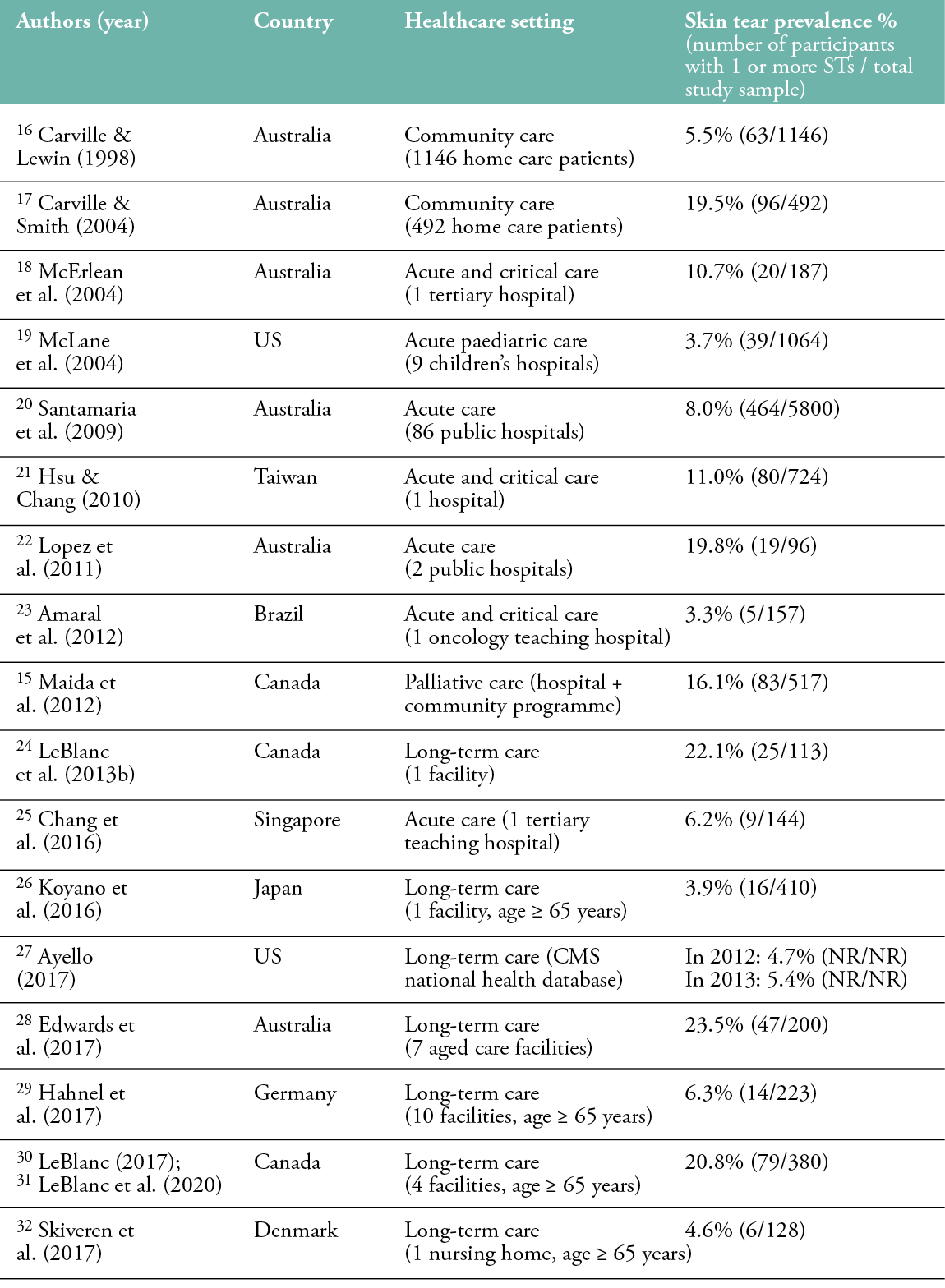

The prevalence of skin tears is estimated between 1.1% and 41.2%, with the highest prevalence in long-term care facilities (Table 1). Studies in long-term care have reported skin tear prevalence rates between 3.0% and 41.2%, measured in samples ranging from 34 to 1253 residents. In acute care settings, skin tear prevalence is slightly lower, varying from 1.1% to 19.8%. One study was conducted in the palliative care setting, reporting a skin tear prevalence of 16.1%.15 Carville and Lewin (1998) and Carville and Smith (2004) documented skin tear prevalence rates of 5.5% and 19.5%, respectively, among Australian patients in community care.16,17 In several studies, only the extremities of the body were observed, which may have resulted in the omission and underreporting of skin tears.

Table 1: Prevalence of skin tears

2.2. Incidence of skin tears

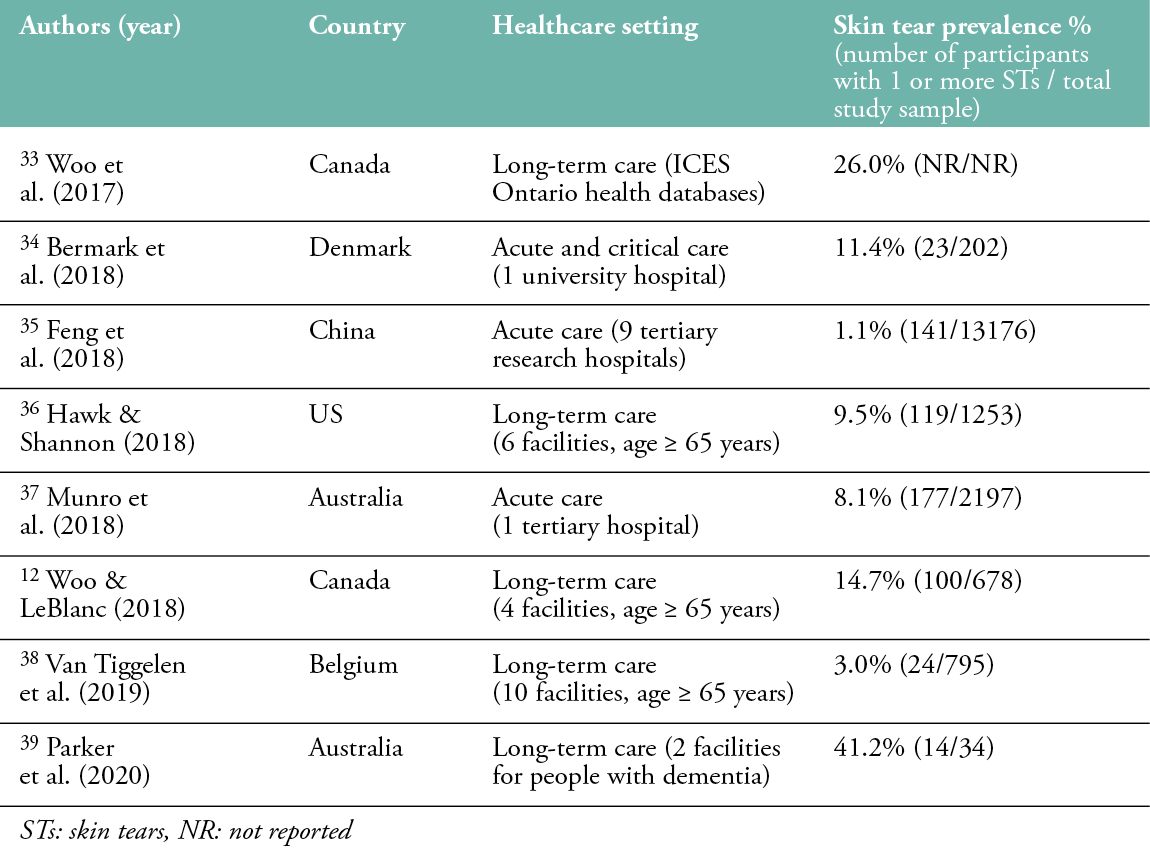

The incidence of skin tears varies from 2.2% to 62.0%, with the highest incidence in rehabilitation and critical care settings (Table 2). Everett and Powell (1994) and Finch et al. (2018) reported incidence rates of skin tears of 6.3% and 8.8%, respectively, in Australian acute care patients over a 1-month follow-up period.40,41 Kennedy and Kerse’s (2011) study showed a skin tear incidence rate of 5.0% among 2401 outpatients from a primary healthcare facility in New Zealand over a 2-year follow-up period.42 In long-term care facilities, incidence rates of skin tears ranged from 2.2% to 44.8%, measured in a sample of 29 to 1567 residents. Consistent with the studies reporting the prevalence of skin tears, almost all skin tear incidence studies were conducted in Asia, Australia, Canada and the United States. Only one incidence study was conducted in Europe. Powell et al. (2017) reported an incidence rate for skin tears of 20.0% in 90 primary care outpatients and nursing home residents (aged ≥ 65 years) in the United Kingdom over a follow-up period of 112 days.43

The wide variability in prevalence and incidence rates may be due in part to different patient populations and differences in methodologic design, prevention and management practices, caregivers, knowledge, attitudes and equipment. Another explanation for this variability may be the complexity of correctly diagnosing a skin tear and distinguishing it from other skin lesions, such as superficial pressure ulcers.10 The lack of an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code for skin tears and a standardised, universally accepted classification system to support accurate and consistent assessment may have contributed significantly to these variations.3

Table 2: Incidence of skin tears

3. AN UNDERRECOGNISED AND UNDERREPORTED ISSUE

Despite their significant impact, skin tears are often unrecognised and underreported in clinical practice, resulting in suboptimal prevention and delayed or inappropriate treatment.56 One reason for this could be that skin tears are often regarded as unavoidable and relatively insignificant wounds. They are frequently perceived as a normal occurrence of ageing skin, and their effects are often downplayed by healthcare professionals.57

A second reason could be the lack of standardised terminology. The term ‘skin tear’ is not commonly used, and skin tears are often referred to as ‘lacerations’, ‘abrasions’, ‘geri tears’ or ‘epidermal tears.3,58 The lack of a specific code for skin tears in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) may exacerbate their perceived insignificance and potential for underreporting.59 In ICD-11, skin tears are subsumed under the general term ‘laceration’ and referred to according to their anatomical site of injury60; however, a skin tear is a specific injury that is distinct from a general laceration, which is defined as a jagged and irregular cut or tear of soft body tissue.61 Because soft tissue includes muscle, fatty and fibrous tissue, tendons, ligaments, nerves and blood vessels, lacerations can involve more extensive tissue types than skin tears.62

A third reason may be that skin tears are often misdiagnosed as other wound causes, such as medical adhesive-related skin injuries (MARSI) or pressure ulcers (PUs).3,59 MARSI is a relatively new category of skin damage defined as ‘an occurrence in which erythema and/or other manifestation of a cutaneous abnormality (including but not limited to vesicles, blisters, erosions or tears) persists for 30 minutes or longer after removal of an adhesive’.63 (page 371) Although skin tears are a common manifestation of MARSI, they can be caused by factors other than medical adhesives.64 A PU is defined as ‘a localised injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue, usually over a bony prominence, resulting from sustained pressure (including pressure associated with shear)’.65 (page 12) In contrast to skin tears, PUs are chronic wounds in which damage is initiated by changes in soft tissue beneath and within the skin due to sustained mechanical stress in the form of pressure, or pressure combined with shear.66

4. AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Skin tears can be caused by a variety of mechanical forces, such as shear and friction, including blunt trauma, falls, poor positioning/transfer techniques, injury from devices and the removal of adhesive dressings. As a result, the epidermis is separated from the dermis (partial thickness wound), or both the epidermis and dermis are separated from underlying structures (full thickness wound). Less force is required to cause a skin tear in individuals with fragile or vulnerable skin.3

Due to age-related physiological skin changes, neonates and the elderly are particularly susceptible to skin tears.2 Newborns have significantly fewer layers of stratum corneum, fewer collagen and elastic fibres, increased transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and less cohesion between the epidermis and dermis.67,68 Because neonatal skin is not fully mature, it is more sensitive and less resistant to mechanical stresses such as friction and shear forces.2,69

Later in life, the normal ageing process causes structural and functional changes in the skin, resulting in increased vulnerability.70 With age, the skin loses collagen and elastin, the epidermis gradually thins and there is a loss of dermal and subcutaneous tissue, making the skin more fragile and less elastic.71,72 Keratinocyte proliferation and turnover time in the epidermis are reduced.73 In addition, the dermo-epidermal junction begins to flatten, increasing the susceptibility of the epidermis to detach from the underlying dermis12, and barrier function and mechanical protection are impaired.70 In addition, the content of natural moisturising factors (NMF) and lipids in the stratum corneum decreases, as do sweat and sebum production, resulting in dry and itchy skin.74 Other skin changes associated with the normal ageing process include increased skin surface pH and decreased immune responses, sensory perception and blood supply.75 Blood vessels become thinner, more fragile and rupture easily, resulting in subcutaneous haemorrhages known as senile purpura and ecchymosis.76 Haemorrhages beneath the epidermis allow the skin to lift off more easily when friction or shear forces are applied.77 These lesions should not be confused with a haematoma, which is a palpable bruise or localised collection of blood in tissue caused by trauma to an underlying blood vessel.78 The skin tension resulting from haematoma formation may make the skin more susceptible to breakdown from further trauma.79

Skin atrophy, senile purpura, ecchymosis and haematomas have been previously identified as intrinsic skin changes due to ageing, representing a chronic state of cutaneous insufficiency/fragility termed ‘dermatoporosis’.80 The ageing process is genetically determined, but can be highly influenced by environmental factors such as extensive UV exposure (photoaging), air pollution and smoking.81 Several studies have identified chronic renal insufficiency, anticoagulant therapy and long-term use of topical and systemic corticosteroids as additional significant risk factors for dermatoporosis.82,83,84,85,86 The skin of individuals with dermatoporosis has a reduced mechanical protective function and lower tolerance to friction and shear forces.87 As a result of this weakness, these individuals are at increased risk of skin damage from even minor forces or trauma.73 Some studies in the French and Finnish elderly populations have found prevalence rates for dermatoporosis ranging from 27.0% to 37.5%. Dermatoporosis occurred mainly in the upper limbs.82,84,85,86

In addition to intrinsic and extrinsic skin ageing, there are several other factors that can compromise skin integrity.1 For example, excessive washing with alkaline soap leads to a significant increase in skin pH and TEWL, as well as the removal of natural oils from the stratum corneum, resulting in epidermal barrier disruption and dry skin.71 Dry skin is more susceptible to friction and shear forces.69 Other factors that contribute to skin fragility and make skin vulnerable and at risk to tears include chronic and critical illness, poor nutrition, limited mobility and polypharmacy.1,2,72,73,76

Populations at highest risk for skin tears are also at increased risk for complications such as infection and delayed wound healing, which can lead to skin tears developing into complex chronic wounds.6,56,88

5. CLASSIFICATION OF SKIN TEARS

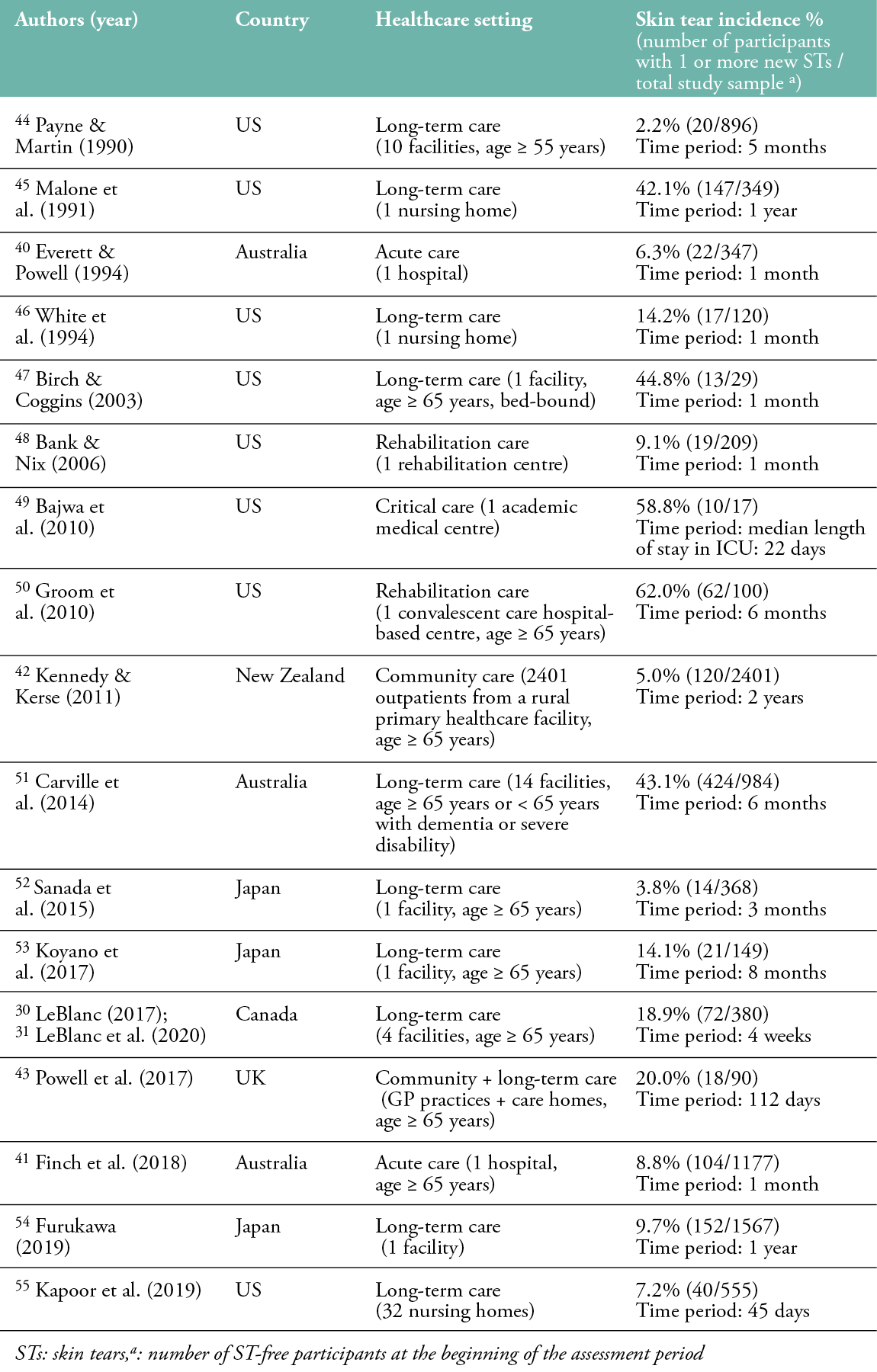

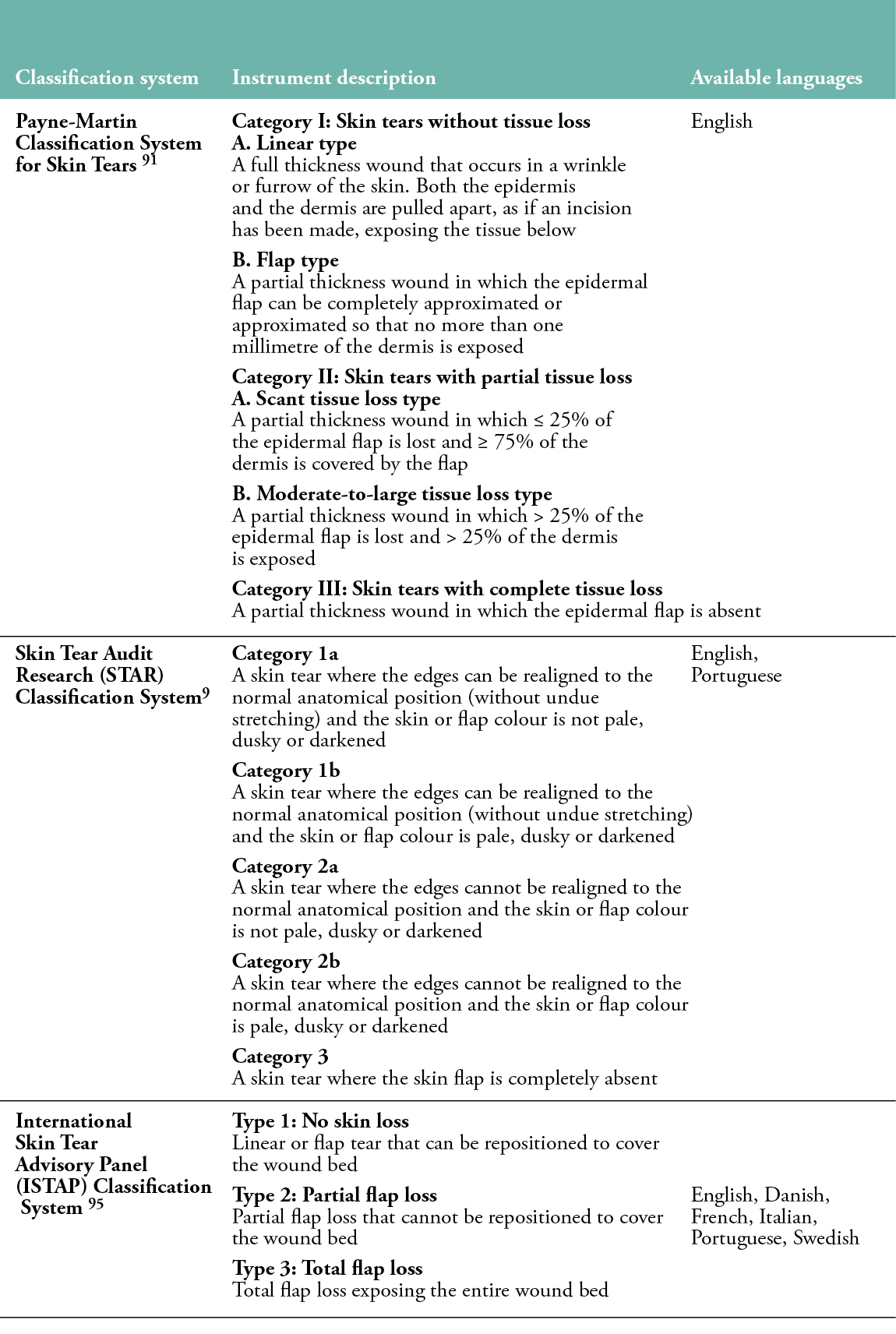

Classification systems are valuable tools to support and standardise the diagnostic process by providing common descriptions of the severity of skin tears based on the extent of tissue loss.88 Assessing the extent of tissue (skin flap) loss is important for treatment decisions.89 In addition, the use of a common classification system enables clinical and scientific communication and promotes consistency in documentation for clinical practice, auditing and research purposes.5,90 Three classification systems for skin tears have been developed to date (Table 3).

Table 3: Description of the skin tear classification systems

The first classification was proposed by Payne and Martin in 1990,44 and then slightly revised in 1993. The Payne-Martin Classification System distinguishes three categories and four subcategories based on the extent of tissue loss, measured as a percentage.91 The system has never been evaluated for its psychometric properties and has been criticised for its complexity, ambiguity and low dissemination outside the United States.3 In 2007, Carville et al. introduced and psychometrically tested the Skin Tear Audit Research (STAR) Classification System, which was developed as a modified version of the Payne-Martin classification and additionally includes the distinction of skin and lobe colour.9 The STAR classification evaluates the skin and any residual flap for haematoma and ischemia, which could affect tissue viability and treatment decisions. Similar to the Payne-Martin classification, the STAR classification has been found to be subjective and complex for use in clinical practice, which may affect the consistency of documentation.3,92,93 Further, it has not been widely implemented outside of Australia, Brazil and Japan.5

A descriptive study among 520 nurses from 104 Australian nursing homes found a need for consistent language to describe and classify skin tears. None of the participating nurses used the Payne-Martin Classification System, though 89% indicated they would be willing to use a common, user-friendly tool to assess and document skin tears, if it were made available.11 In 2010, an international cross-sectional study was conducted involving 1127 healthcare professionals from 16 countries to examine current practices in the assessment, prevention and treatment of skin tears.94 Seventy percent of respondents reported problems with the current assessment and documentation of skin tears in their practice, with an overwhelming majority (90%) favouring a simplified method. Eighty-one percent of respondents reported that they did not use any skin tear classification system, although they did perform weekly skin tear wound assessments. Ten percent of all respondents used the Payne-Martin Classification System, and 5.8% used the STAR Classification System.

In an effort to meet the need for a user-friendly and simple classification tool, an international panel of experts developed and psychometrically tested the ISTAP Classification System, which classifies skin tears into Type 1 (no skin loss), Type 2 (partial flap loss) or Type 3 (total flap loss).95 The presence or absence of haematoma and ischemia was not included in the ISTAP classification because it appears to be prescriptive (e.g., predictive of potential skin rupture risk and healing time), rather than descriptive, which detracts from the simplicity of the instrument.30 Although the ISTAP classification categorises skin tears based on the severity of skin flap loss, it does not include a definition of a ‘skin flap’. In their best practices document (2018), the ISTAP panel indicated the need for standardised terminology and definitions to avoid confusion. Since its development in 2013, the ISTAP classification has been translated into several languages and psychometrically tested in several countries. However, it is acknowledged that further translation and psychometric testing with larger samples of healthcare professionals in different settings and countries is still needed.3

Along with the lack of standardised terminology, the lack of a uniform method for assessing and documenting skin tears using a valid, reliable and internationally accepted classification system can lead to inadequate diagnostic accuracy and inaccurate prevalence and incidence data.94 This can complicate communication among healthcare professionals, benchmarking, making appropriate treatment decisions and analysing care outcomes.9,25,88 In addition to the need for further psychometric testing and translation of existing classification systems, it would be useful to critically evaluate, compare and summarise the quality of their measurement properties to determine which classification can be recommended for use in daily practice and research.3

6. PREVENTION OF SKIN TEARS

Because skin tears are largely preventable wounds that can cause significant suffering and avoidable costs, the primary focus should be on effective prevention.57 Unfortunately, the cost of treating skin tears is poorly reported, although one North American study reported the economic benefits of implementing a skin tear prevention programme.48 The programme included staff training, skin sleeves and padded side rails for high-risk patients, gentle skin cleansers and skin lotion application. Bank and Nix (2006) found that the incidence of skin tears decreased significantly, from an average of 9.1% to an average of 4.3% per month, after the prevention programme was implemented in a 209-bed nursing and rehabilitation centre. This decrease was associated with a reduction of $1,698 per month ($18,168.60 annually) in the cost of dressings and labour to treat skin tears.

Careful and timely identification of patients at risk for skin tears is an essential component of prevention.3 Because the risk for skin fragility, and thus skin tears, can change in different individuals at different times, it is important to assess and reassess patients on a regular basis. Accurate, consistent and comprehensive documentation should be an essential part of this process.1 Once a person is identified as being at risk, tailored preventive care should be provided in accordance with international evidence-based guidelines. Recently, three new best practice guidelines have been developed to guide healthcare professionals in improving the assessment, classification, treatment and prevention of skin tears.1,3,88 It should be noted, however, that evidence for skin tear prevention is sparse and based primarily on experts’ opinions, due to a lack of systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials.88

A multidisciplinary team approach is recommended for implementing a skin breakdown prevention programme. Team members may include, but are not limited to, nurses, physicians, wound specialists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, social workers, dietitians and pharmacists.88 Patients, their families and caregivers should also be involved and educated wherever possible, and their needs and preferences should be prioritised.1 Empowering patients, families and caregivers to engage actively in prevention strategies has been shown to be associated with better health outcomes, improved care experiences, higher quality of life and lower healthcare costs.41,88,96

In a 2010 international study, injuries from equipment, transferring patients, performing activities of daily living, removing dressings and falls were cited as the most common causes of skin tears.94 It should be noted that many of these causes are preventable, such as through the use of skin-friendly dressings and removal techniques (e.g., non-adherent silicone mesh dressings); lifting devices and sliding sheets; protective clothing (e.g., shin/elbow guards, long sleeves/trousers/gloves, knee-high socks); padding on equipment and furniture (e.g., bed rails, arm and leg supports for wheelchairs); fall prevention (e.g., clearing clutter, ensuring adequate lighting, wearing sturdy footwear); avoidance of sharp fingernails and jewellery; and the education of medical staff, patients and family members about appropriate positioning/transfer techniques and skin-friendly equipment, preferably by occupational and physical therapists.1

Appropriate skin care strategies are an effective way to maintain and improve skin health and integrity and restore the skin’s barrier function in individuals with vulnerable skin.74 A structured, individualised skin care regimen consisting of gentle skin cleansing and moisturising is recommended.1 Traditional washing with water and alkaline soap should be avoided, as it compromises the integrity of the skin barrier and increases the skin’s pH.97 Using no-rinse cleansers or soap-free liquid detergents that reflect the pH range of the acid mantle of healthy skin (pH 4.5–6.5) as a soap substitute can help moisturise and protect sensitive skin from damage.74 Excessive cleansing should be avoided, as this can lead to skin dryness and

irritation. Frequency of bathing should be minimised, if possible; water temperature should be lukewarm (not hot); and skin should be gently patted dry with a soft towel, as drying the skin by rubbing causes additional friction.1

Cleansing is often followed by the application of leave-on products with moisturising properties such as lotions, creams or ointments.97 Skin moisturisers aim to repair or strengthen the skin barrier, maintain or increase its water content, reduce TEWL and restore or improve the intercellular lipid structure.1 Emollient therapy is considered an important part of daily skin care for people with dry, sensitive skin to promote overall skin health and reduce the risk of skin damage.72 Dry skin, or xerosis cutis, has been reported to affect between 30% and 100% of residents in aged care facilities and is a major risk factor for developing skin tears.74 An Australian study found that twice-daily application of a pH-neutral, fragrance-free moisturiser to the extremities of elderly care residents reduced the incidence of skin tears by nearly 50%.51 Emollients are available in a variety of formulations, including topical moisturisers (ointments, creams, lotions, gels and sprays) and liquid body washes. They should have a balanced pH, be fragrance-free and not be sensitising. Many emollients contain humectants such as urea, glycerol or isopropyl myristate, which either mimic or consist of the same molecules as NMF.72 Patient preference and acceptability are particularly important when selecting emollients, as they are key to adherence. Skin self-care should be encouraged wherever possible, as it can be an effective means of increasing engagement and improving outcomes as part of a skin care regimen.1

In addition to creating a safe environment and implementing a tailored skin care regimen, skin breakdown prevention programmes should also consider nutrition, polypharmacy and mobility issues.1 Poor nutritional status decreases tissue tolerance, which increases the likelihood of skin tears.88 In addition, malnutrition and dehydration can lead to delayed wound healing and infection, increasing the risk of skin tears developing into complex chronic wounds.98 Monitoring should be continuous, and a nutritionist can be consulted as needed to optimise the patient’s nutrition and hydration.1

A variety of medications can cause changes in the skin that need to be treated appropriately.1 Corticosteroids, for example, inhibit collagen synthesis, decrease keratinocyte proliferation and reduce skin firmness and elasticity.99 Anticoagulant use can cause dermatologic changes such as senile purpura and ecchymosis, which have been identified as contributing factors to skin tears.26 Antidepressants, dopaminergic medications and antipsychotics can cause dizziness, unsteady gait and confusion, which can lead to falls and resulting skin lacerations.100 The effects of medications and polypharmacy on the patient’s skin and wound healing should be continuously monitored and eventually discussed with the prescriber or a pharmacist.88

7. TREATMENT OF SKIN TEARS

Wound management tailored to the individual patient, their skin and wound and other preventive measures require a comprehensive assessment of both the wound and the patient.101 A thorough wound assessment must consider and document the following aspects: cause of wound, duration of injury, anatomic location, dimensions (length, width, depth), characteristics of the wound bed, percentage of viable/non-viable tissue, extent of skin flap loss (classification), type and amount of exudate, presence of bleeding or haematoma, integrity of surrounding skin, signs and symptoms of infection and associated pain. Holistic assessment of the patient should include: medical history, history of skin breakdown, general health, comorbidities, medications, mental health issues, socio-economic and psychosocial factors, self-management potential, mobility, nutrition and hydration.3

Based on the thorough holistic assessment, an individualised care plan should be developed in collaboration with the patient, their family and a multidisciplinary team to maintain a continuous link among prevention, assessment and treatment. The care plan should include realistic goals that take into account the patient’s needs, abilities and preferences, and any opportunities for and potential barriers to ongoing treatment.88 Factors that may impede the wound-healing process (e.g., diabetes, smoking, malnutrition, anticancer medications, peripheral oedema) must be considered whenever possible.57 The assessment process and plan of care should be clearly documented, including dates for reassessment and reasons for choosing interventions.102 Engaging patients and their families in a collaborative care plan is critical for setting appropriate goals, ensuring adherence to planned interventions, improving quality of life and optimising clinical and financial outcomes.103

When possible, the treatment of skin tears should aim to preserve the skin flap, reapproximate the edges of the wound, preserve the surrounding tissue and minimise the risk of infection and further injury.3 The first steps are to stop the bleeding, clean the wound and remove any debris or haematoma. The surrounding skin should be gently patted dry to prevent further injury.88 Skin tears with necrotic tissue or scabs may require debridement, as the presence of devitalised tissue provides a focus for infection, prolongs the inflammatory response and delays wound healing.104 If the skin flap is viable, it should be reapproximated as much as possible to cover the wound surface (without stretching the skin).105 The flap can be pushed back into place with a moistened cotton ball, gloved finger, forceps or silicone strip. Topical skin adhesive can be used to approximate wound edges for primary closure in Type 1 skin tears. Adhesive wound closure strips, sutures and staples are not recommended, due to the fragility of the skin.3

Once the skin flap is in place, a non-adherent and atraumatic dressing should be applied to optimise the healing environment and protect the fragile skin from further injury (e.g., silicone mesh/foam/hydrogel, possibly in combination with a secondary cover dressing). If possible, the dressing should remain in place for at least 5–6 days, to avoid disturbing the skin flap. The ideal dressing should be easy to apply and remove; prevent trauma to the wound bed, skin flap and surrounding skin during removal/dressing changes; provide a protective barrier against shear forces; maintain moisture balance; and allow for extended wear.3 Dressings should be selected in accordance with local wound conditions, patient-related factors and treatment goals.88 When local or deep tissue infection is suspected or confirmed, the use of atraumatic antimicrobial dressings (e.g., methylene blue and gentian violet) should be considered.3 Wound infections can increase healthcare costs, delay healing, cause complications (e.g., sepsis) and significantly impact patients’ daily lives.106 Exudate must be effectively managed to provide the optimal moist environment necessary for wound healing and to protect the skin in the vicinity of the wound from the risks of maceration and excoriation.107 If a skin tear is heavily exudating, an absorbent dressing (e.g., foam, calcium alginate, gelling fibres) and a skin barrier product may be beneficial for protecting the surrounding skin.108 Dressings need to be changed more frequently if signs of infection or heavy exudate are present.88 At each dressing change, the dressing should be removed slowly, working away from the attached skin flap.89 The correct direction of removal can be indicated with an arrow on the dressing.100 Changes in wound status should be carefully monitored to determine response to treatment. If the wound does not improve promptly (e.g., after four assessments) or deterioration is observed, the underlying conditions should be reassessed and the care plan adjusted accordingly.3,102

8. SKIN TEARS ANNO 2022

With an ageing population and increased prevalence of chronic diseases, skin tears are expected to remain a common health problem that poses a significant burden on the world’s healthcare systems and individual patients.12 As a consequence, more patients will benefit from early and accurate identification and classification, comprehensive documentation, appropriate treatment and effective prevention. Although there has been an increased focus on the issue of skin tears in recent years, there are still gaps in knowledge and awareness, and areas that require further research.3

In April 2022, Hanne Van Tiggelen defended her PhD thesis on skin tears. To our knowledge, this is one of the few dissertations in the world on this topic. Her research focuses on epidemiology, classification and knowledge assessment. In an initial study, she reported on the first prevalence study of skin tears in Belgium and only the fourth in Europe.38 This cross-sectional observational study found a prevalence of skin tears of 3.0% among 1153 Belgian nursing home residents. Knowing the prevalence of skin tears is important for gaining insight into the extent of the problem. It can help allocate resources, enable benchmarking, support goal setting and promote the implementation of evidence-based prevention, treatment and education strategies. Because skin tears are largely preventable adverse events that are sensitive to the quality of care delivered by multidisciplinary teams, it is recommended that they be included as part of a multifaceted strategy to improve skin tear care in current wound review programmes. To improve the quality, interpretability and comparability of epidemiologic data on skin tears across healthcare settings and countries, the development of a standardised data collection process using a valid and reliable minimum data set is needed. Policymakers should discuss the importance, potential impact and feasibility of developing and implementing quality indicators for skin tears at the structural, process and outcome levels.

In addition to examining the prevalence of skin tears, this study also aimed to identify factors independently associated with the presence of skin tears.38 This knowledge will allow the early identification of patients at risk, the timely initiation of preventive measures and the targeting of preventive measures to specific associated factors. Multivariate binary logistic regression analyses showed that nursing home residents with advanced age, a history of skin tears, chronic use of corticosteroids, dependence on transfers and use of adhesives/dressings were at higher risk for developing skin tears. Future research should explore how to integrate current knowledge of a wide range of risk factors for skin tears into a reliable and easy-to-use skin tear risk assessment tool with sufficient predictive power for use in research and practice. Consideration should also be given to the introduction of a pooled prevention approach that focuses on common risk factors for a range of different skin lesions.

In a second study, the ISTAP classification was psychometrically validated internationally.109 After a two-round Delphi process involving 17 experts from 11 countries, the following definition of a ‘skin flap’ was included in the tool: ‘A flap in skin tears is defined as a portion of the skin (epidermis/dermis) that is unintentionally separated (partially or fully) from its original place due to shear, friction, and/or blunt force. This concept is not to be confused with tissue that is intentionally detached from its place of origin for therapeutic use, e.g., surgical skin grafting’. The results of psychometric testing on a sample of 1601 healthcare professionals from 44 countries showed that skin tears can be validly and reliably assessed using the ISTAP classification system. Higher accuracy, reliability and agreement scores were found among more experienced and better trained healthcare professionals, suggesting that sufficient and appropriate education and training are important for optimising skin tear identification and classification skills. The use of a standardised and internationally recognised skin tear classification system is recommended to support systematic, accurate and consistent assessment and reporting. Consideration should be given to integrating the ISTAP tool into electronic health records and using it in future skin tear research to improve the accuracy and comparability of study results. As part of our study, the tool was translated into 15 languages, promoting global awareness and use.

In a third study, existing skin tear classifications were critically evaluated, compared and summarised in terms of their measurement properties.110 This systematic review, which included 14 studies in a qualitative synthesis, found that there are five classifications for skin tears (Payne-Martin, Dunkin, Lo, STAR and ISTAP), of which only two have been psychometrically tested (STAR and ISTAP). Due to the methodological heterogeneity of the studies (e.g., study design, procedures, sample characteristics), different statistical analyses, lack of confidence intervals and inadequate reporting, a meta-analysis could not be conducted. Three studies of very low methodological quality showed insufficient reliability and criterion validity of the STAR classification.9,25,111 To date, the ISTAP classification is the most commonly assessed system, with moderate quality evidence for reliability, measurement error and criterion validity. The downgrading of evidence from high to moderate has been associated with the use of photographs in psychometric testing (indirect skin observation). More well-designed, rigorously conducted and adequately reported studies with representative samples, appropriate statistical methods and direct skin observations are needed to draw reliable conclusions.

In a final study, an instrument to assess knowledge of skin tears (OASES) was designed and tested internationally.112 OASES was developed based on the latest evidence-based guidelines for the prevention and treatment of skin tears. Content validity was established in a two-round Delphi process by a panel of 10 international experts. Psychometric testing on a sample of 387 nurses from 37 countries revealed adequate validity and reliability of the English version. The final instrument consists of 20 multiple-choice items covering six domains most relevant to skin tears: (1) aetiology, (2) classification and observation, (3) risk assessment, (4) prevention, (5) treatment and (6) specific patient populations. OASES can be used in nursing education, postgraduate education, research and practice to assess both factual knowledge and more complex cognitive skills related to skin tears. Insights into educational needs and priorities can support the development of tailored educational programmes and other strategies aimed at improving the quality of skin tears care. The next step should be to translate and validate OASES into other languages to enable worldwide use.

9. CONCLUSIONS

Skin tears represent a significant problem for patients and multidisciplinary teams across the healthcare spectrum. Despite their high prevalence, significant impact on patient well-being and substantial financial burden on healthcare systems, skin tears remain an understudied injury in clinical practice and research. In recent years, international best practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of skin tears have been developed to assist healthcare professionals in evidence-based decision making, reduce disparities in care, improve patient outcomes and reduce costs; however, adherence to these guidelines in clinical practice is poor. This work contributes to the small but growing body of evidence on the epidemiology of skin tears and provides tools to facilitate the translation of guidelines into practice to improve skin tear care. In addition, this work provides the necessary foundation for future research to develop and evaluate preventive, therapeutic and educational interventions.

Author(s)

Hanne Van Tiggelen1, Dimitri Beeckman1,2

1. Skin Integrity Research Group (SKINT), University Centre for Nursing and Midwifery, Department of Public Health and Primary

Care, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

2. Swedish Centre for Skin and Wound Research (SCENTR), School of Health Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden

Correspondence: Dimitri.Beeckman@UGent.be

Conflict of interest: Hanne Van Tiggelen: None, Dimitri Beeckman: Immediate Past President, ISTAP

References

- Beeckman D, Campbell K, LeBlanc K, Campbell J, Dunk AM, Harley C, et al. [Internet]. Best practice recommendations for holistic strategies to promote and maintain skin integrity. Wounds Int 2020; Available at: [https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/best-practice-recommendations-holistic-strategies-promote-and-maintain-skin-integrity].

- Kottner J, Beeckman D, Vogt A, Blume-Peytavi U. Skin health and integrity. In Innovations and emerging technologies in wound care. Elsevier Academic Press; 2020a. p. 183–96. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-815028-3.00011-0

- LeBlanc K, Campbell K, Beeckman D, Dunk AM, Harley C, Hevia H et al. [Internet]. Best practice recommendations for the prevention and management of skin tears in aged skin. Wounds Int 2018a; Available at: [https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/istap-best-practice-recommendations-prevention-and-management-skin-tears-aged-skin].

- Serra R, Ielapi N, Barbetta A, de Franciscis S. Skin tears and risk factors assessment: A systematic review on evidence‐based medicine. Int Wound J 2018; 15(1):38–42. doi:10.1111/iwj.12815

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S. Skin tears: Finally recognized. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017; 30(2):62–3. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000511435.99585.0d

- Idensohn P, Beeckman D, Campbell KE, Gloeckner M, LeBlanc K, Langemo D, et al. Skin tears: A case-based and practical overview of prevention, assessment and management. J Community Nurs 2019a; 33(2):32–41.

- Brimelow RE, Wollin JA. The impact of care practices and health demographics on the prevalence of skin tears and pressure injuries in aged care. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27(7–8):1519–28. doi:10.1111/jocn.14287

- Vandervord JG, Tolerton SK, Campbell PA, Darke JM, Loch‐Wilkinson AMV. Acute management of skin tears: A change in practice pilot study. Int Wound J 2016; 13(1):59–64. doi:10.1111/iwj.12227

- Carville K, Lewin G, Newall N, Haslehurst P, Michael R, Santamaria N, Roberts P. (2007). STAR: A consensus for skin tear classification. Primary Intention 2007; 15(1):18–28. doi:10.3316/informit.331468593516275

- LeBlanc K, Alam T, Langemo D, Baranoski S, Campbell K, Woo K. Clinical challenges of differentiating skin tears from pressure ulcers. EWMA J 2016; 16(1):17–23.

- White W. Skin tears: A descriptive study of the opinions, clinical practice and knowledge base of RNs caring for the aged in high care residential facilities. Primary Intention 2001; 9(4):138–49. doi:10.3316/informit.772287427077109

- Woo K, LeBlanc K. Prevalence of skin tears among frail older adults living in Canadian long-term care facilities. Int J Palliat Nurs 2018; 24(6):288–94. doi:10.12968/ijpn.2018.24.6.288

- Kuhn JE, Greenfield MLV, Wojtys EM. A statistics primer: Prevalence, incidence, relative risks, and odds ratios: Some epidemiologic concepts in the sports medicine literature. Am J Sports Med 1997; 25(3):414–6. doi:10.1177/036354659702500325

- Noordzij M, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, Jager KJ. Measures of disease frequency: Prevalence and incidence. Nephron Clin Pract 2010; 115(1):17–20. doi:10.1159/000286345

- Maida V, Ennis, M, Corban J. Wound outcomes in patients with advanced illness. Int Wound J 2012; 9(6):683–92. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.00939.x

- Carville K, Lewin G. Caring in the community: A wound prevalence survey. Primary Intention 1998; 6(2):54–62.

- Carville K, Smith J. A report on the effectiveness of comprehensive wound assessment and documentation in the community. Primary Intention 2004; 12(1):41–9. doi:10.3316/informit.657321994879676

- McErlean B, Sandison S, Muir D, Hutchinson B, Humphreys W. Skin tear prevalence and management at one hospital. Primary Intention: 2004; 12(2):83–8. doi:10.3316/informit.663619939164948

- McLane KM, Bookout K, McCord S, McCain J, Jefferson LS. The 2003 national pediatric pressure ulcer and skin breakdown prevalence survey: A multisite study. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs 2004; 31(4);168–78. doi:10.1097/00152192-200407000-00004

- Santamaria N, Carville K, Prentice J. WoundsWest: Identifying the prevalence of wounds within western Australia’s public health system. EWMA J 2009; 9(3):13–8.

- Hsu M, Chang S. A study on skin tear prevalence and related risk factors among inpatients. Tzu Chi Nurs J 2010; 9(4):84–95.

- Lopez V, Dunk AM, Cubit K, Parke J, Larkin D, Trudinger, M, Stuart M. Skin tear prevention and management among patients in the acute aged care and rehabilitation units in the Australian Capital Territory: A best practice implementation project. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2011; 9(4):429–34. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00234.x

- Amaral AFdS, Strazzieri-Pulido KC, Santos, VLCdG. Prevalence of skin tears among hospitalized patients with cancer. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2012; 46(1):44–50. doi:10.1590/S0080-62342012000700007

- LeBlanc K, Christensen D, Cook J, Culhane B, Gutierrez O. Prevalence of skin tears in a long-term care facility. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013b; 40(6):580–4. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e3182a9c111

- Chang YY, Carville K, Tay AC. The prevalence of skin tears in the acute care setting in Singapore. Int Wound J 2016; 13(5):977–83. doi:10.1111/iwj.12572

- Koyano Y, Nakagami G, Iizaka S, Minematsu T, Noguchi H, Tamai N, et al. Exploring the prevalence of skin tears and skin properties related to skin tears in elderly patients at a long‐term medical facility in Japan. Int Wound J 2016; 13(2):189–97. doi:10.1111/iwj.12251

- Ayello EA. CMS MDS 3.0 section M skin conditions in long-term care: Pressure ulcers, skin tears, and moisture-associated skin damage data update. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017; 30(9):415–29. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000521920.60656.03

- Edwards HE, Chang AM, Gibb M, Finlayson KJ, Parker C, O’Reilly M, et al. Reduced prevalence and severity of wounds following implementation of the Champions for Skin Integrity model to facilitate uptake of evidence‐based practice in aged care. J Clin Nurs 2017; 26(23–4): 4276–85. doi:10.1111/jocn.13752

- Hahnel E, Blume-Peytavi U, Trojahn C, Kottner J. Associations between skin barrier characteristics, skin conditions and health of aged nursing home residents: A multi-center prevalence and correlational study. BMC Geriatr 2017; 17(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0655-5

- LeBlanc K. Skin tear prevalence, incidence and associated risk factors in the long-term care population (Doctoral dissertation). Available from QSpace Library, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada; 2017.

- LeBlanc K, Woo K, VanDenKerkhof E, Woodbury MG. Skin tear prevalence and incidence in the long-term care population: A prospective study. J Wound Care 2020; 29(Sup7):S16–22. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.Sup7.S16

- Skiveren J, Wahlers, B, Bermark S. Prevalence of skin tears in the extremities among elderly residents at a nursing home in Denmark. J Wound Care 2017; 26(Sup2):S32–6. doi:10.12968/jowc.2017.26.sup2.s32

- Woo K, Sears K, Almost J, Wilson R, Whitehead M, VanDenKerkhof EG. Exploration of pressure ulcer and related skin problems across the spectrum of health care settings in Ontario using administrative data. Int Wound J 2017; 14(1):24–30. doi:10.1111/iwj.12535

- Bermark S, Wahlers B, Gerber AL, Philipsen P A, Skiveren J. Prevalence of skin tears in the extremities in inpatients at a hospital in Denmark. Int Wound J 2018; 15(2):212–7. doi:10.1111/iwj.12847

- Feng H, Wu Y, Su C, Li G, Xu C, Ju C. Skin injury prevalence and incidence in China: A multicentre investigation. J Wound Care 2018; 27(Sup10):S4–9. doi:10.12968/jowc.2018.27.Sup10.S4

- Hawk J, Shannon M. Prevalence of skin tears in elderly patients: A retrospective chart review of incidence reports in 6 long-term care facilities. Ostomy Wound Manag 2018; 64(4):30–6.

- Munro EL, Hickling DF, Williams DM, Bell JJ. Malnutrition is independently associated with skin tears in hospital inpatient setting - Findings of a 6‐year point prevalence audit. Int Wound J 2018; 15(4):527–33. doi:10.1111/iwj.12893

- Van Tiggelen H, Van Damme N, Theys S, Vanheyste E, Verhaeghe S, LeBlanc K, et al. The prevalence and associated factors of skin tears in Belgian nursing homes: A cross-sectional observational study. J Tissue Viability 2019; 28(2):100–6. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2019.01.003

- Parker CN, Finlayson KJ, Edwards HE, MacAndrew M. Exploring the prevalence and management of wounds for people with dementia in long‐term care. Int Wound J 2020; 17(3):650–9. doi:10.1111/iwj.13325

- Everett S, Powell T. Skin tears - The underestimated wound. Primary Intention 1994; 2(1):28–30.

- Finch K, Osseiran-Moisson R, Carville K, Leslie G, Dwyer M. Skin tear prevention in elderly patients using twice-daily moisturiser. Wound Pract Res 2018; 26(2):99–109. doi:10.3316/informit.733684633832684

- Kennedy P, Kerse N. Pretibial skin tears in older adults: A 2‐year epidemiological study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59(8):1547–8. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03520.x

- Powell RJ, Hayward CJ, Snelgrove CL, Polverino K, Park L, Chauhan R, et al. Pilot parallel randomised controlled trial of protective socks against usual care to reduce skin tears in high risk people: ‘STOPCUTS’. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2017; 3(43):1–22. doi:10.1186/s40814-017-0182-3

- Payne RL, Martin ML. The epidemiology and management of skin tears in older adults. Ostomy Wound Manag 1990; 26:26–37.

- Malone ML, Rozario N, Gavinski M, Goodwin J. The epidemiology of skin tears in the institutionalized elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39(6):591–5. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb03599.x

- White MW, Karam S, Cowell B. Skin tears in frail elders: A practical approach to prevention. Geriatr Nurs 1994; 15(2):95–9. doi:10.1016/s0197-4572(09)90025-8

- Birch S, Coggins T. No-rinse, one-step bed bath: The effects on the occurrence of skin tears in a long-term care setting. Ostomy Wound Manag 2003; 49(1):64–7.

- Bank D, Nix D. Preventing skin tears in a nursing and rehabilitation center: An interdisciplinary effort. Ostomy Wound Manag 2006; 52(9):38–40.

- Bajwa AA, Arasi L, Canabal JM, Kramer DJ. Automated prone positioning and axial rotation in critically ill, nontrauma patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). J Intensive Care Med 2010; 25(2):121–5. doi:10.1177/0885066609356050

- Groom M, Shannon RJ, Chakravarthy D, Fleck CA. An evaluation of costs and effects of a nutrient-based skin care programme as a component of prevention of skin tears in an extended convalescent center. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2010; 37(1):46–51. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e3181c68c89

- Carville K, Leslie G, Osseiran‐Moisson R, Newall N, Lewin G. The effectiveness of a twice‐daily skin‐moisturising regimen for reducing the incidence of skin tears. Int Wound J 2014; 11(4):446–53. doi:10.1111/iwj.12326

- Sanada H, Nakagami G, Koyano Y, Iizaka S, Sugama J. Incidence of skin tears in the extremities among elderly patients at a long‐term medical facility in Japan: A prospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015; 15(8):1058–63. doi:10.1111/ggi.12405

- Koyano Y, Nakagami G, Iizaka S, Sugama J, Sanada H. Skin property can predict the development of skin tears among elderly patients: A prospective cohort study. Int Wound J 2017; 14(4):691–7. doi:10.1111/iwj.12675

- Furukawa C. Factors related to skin tears in a long term care facility. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. Cancer & Chemotherapy 2019; 46(Sup1):154–6.

- Kapoor A, Field T, Handler S, Fisher K, Saphirak, C, Crawford S, et al. Adverse events in long-term care residents transitioning from hospital back to nursing home. JAMA Int Med 2019; 179(9):1254–61. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2005

- Vanzi V, LeBlanc K. Skin tears in the aging population: Remember the 5 Ws. EWMA J 2018; 19(1):15–20.

- Hardie C, Wick JY. Skin tears in older people. Sr Care Pharm 2020; 35(9):379–87. doi:10.4140/TCP.n.2020.379

- Rayner R, Carville K, Leslie G, Roberts P. A review of patient and skin characteristics associated with skin tears. J Wound Care 2015; 24(9):406¬–14. doi:10.12968/jowc.2015.24.9.406

- Rayner R, Carville K, Leslie G. Defining age-related skin tears: A review. Wound Pract Res 2019; 27(3):135–43. doi:10.33235/wpr.27.3.135-143

- World Health Organization [Internet]. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (11th Revision). 2018. Available at: [https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en].

- National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Laceration versus puncture wound. 2019. Available at: [https://medlineplus.gov/ency/imagepages/19616.htm].

- Al-Buriahi MS, Arslan H, Tonguç BT. Mass attenuation coefficients, water and tissue equivalence properties of some tissues by Geant4, XCOM and experimental data. Indian J Pure Appl Phys (IJPAP) 2019; 57(6): 433–7.

- McNichol L, Lund C, Rosen T, Gray M. Medical adhesives and patient safety: State of the science consensus statements for the assessment, prevention, and treatment of adhesive-related skin injuries. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs 2013; 40(4):365–80. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e3182995516

- Hitchcock J, Savine L. Medical adhesive-related skin injuries associated with vascular access. Br J Nurs 2017; 26(8):4–12. doi:10.12968/bjon.2017.26.8.S4

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel & Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: Clinical practice guideline. Osborne Park, Western Australia: Cambridge Media; 2014.

- Beeckman D. Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) and pressure ulcers: An overview. In Science and practice of pressure ulcer management. 2nd ed. London: Springer; 2018. p. 89–101.

- Douma, CE. Skin care. In Manual of neonatal care. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. p. 831–9.

- Oranges T, Dini V, Romanelli M. Skin physiology of the neonate and infant: Clinical implications. Adv Wound Care 2015; 4(10):587–95. doi:10.1089/wound.2015.0642

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S. Skin tears: State of the science: Consensus statements for the prevention, prediction, assessment, and treatment of skin tears. Adv Skin Wound Care, 2011; 24(9):2–15. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000405316.99011.95

- Kottner J, Lichterfeld A, Blume‐Peytavi U. Maintaining skin integrity in the aged: A systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169(3):528–42. doi:10.1111/bjd.12469

- Benbow M. Assessment, prevention and management of skin tears. Nurs Older People 2017; 29(4):31–9. doi:10.7748/nop.2017.e904

- Wounds UK [Internet]. Best practice statement: Maintaining skin integrity. 2018. Available at: [https://www.wounds-uk.com/resources/details/maintaining-skin-integrity].

- Levine JM. Clinical aspects of aging skin: Considerations for the wound care practitioner. Adv Skin Wound Care 2020; 33(1):12–9. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000613532.25408.8b

- Lichterfeld-Kottner A, El Genedy M, Lahmann N, Blume-Peytavi U, Büscher A, Kottner J. Maintaining skin integrity in the aged: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2020; 103:e103509. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103509

- Lichterfeld A, Hahnel E, Blume-Peytavi U, Kottner J. Preventive skin care during skin aging. In Textbook of aging skin. Berlin: Springer; 2014. p. 1–12.

- Holmes RF, Davidson MW, Thompson BJ, Kelechi TJ. Skin tears: Care and management of the older adult at home. Home Healthc Now 2013; 31(2):90–101. doi:10.1097/NHH.0b013e31827f458a

- Koyano Y, Nakagami G, Tamai N, Sugama J, Sanada H. Morphological characteristics of skin tears to estimate the etiology-related external forces that cause skin tears in an elderly population. J Nurs Sci Engineer 2020; 7:68–78. doi:10.24462/jnse.7.0_68

- Newall N, Lewin GF, Bulsara MK, Carville KJ, Leslie GD, Roberts PA. The development and testing of a skin tear risk assessment tool. Int Wound Journal 2017; 14(1):97–103. doi:10.1111/iwj.12561

- Lewin GF, Newall N, Alan JJ, Carville KJ, Santamaria NM, Roberts PA. Identification of risk factors associated with the development of skin tears in hospitalised older persons: A case-control study. Int Wound J 2016; 13(6):1246–51. doi:10.1111/iwj.12490

- Kaya G, Saurat JH. Dermatoporosis: A chronic cutaneous insufficiency/fragility syndrome. Dermatol 2007; 215(4):284–94. doi:10.1159/000107621

- Wollina U, Lotti T, Vojvotic A, Nowak, A. Dermatoporosis – The chronic cutaneous fragility syndrome. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2019; 7(18):3046–9. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2019.766

- Chanca L, Fontaine J, Kerever S, Feneche Y, Forasassi C, Meaume S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of dermatoporosis in older adults in a rehabilitation hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021; 70(4):1252–6. doi:10.1111/jgs.17618

- Dyer JM, Miller RA. Chronic skin fragility of aging: Current concepts in the pathogenesis, recognition, and management of dermatoporosis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2018; 11(1):13–8.

- Kluger N, Impivaara S. Prevalence of and risk factors for dermatoporosis: A prospective observational study of dermatology outpatients in a Finnish tertiary care hospital. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33(2):447–50. doi:10.1111/jdv.15240

- Mengeaud V, Dautezac-Vieu C, Josse G, Vellas B, Schmitt AM. Prevalence of dermatoporosis in elderly French hospital in-patients: A cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166(2):442–3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10534.x

- Saurat JH, Mengeaud V, Georgescu V, Coutanceau C, Ezzedine K, Taïeb C. A simple self‐diagnosis tool to assess the prevalence of dermatoporosis in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(8):1380–6. doi:10.1111/jdv.14240

- Vanzi V, Toma E. Recognising and managing age-related dermatoporosis and skin tears. Nurs Older People, 2018; 30(3):26–31. doi:10.7748/nop.2018.e1022

- LeBlanc K, Woo K, Christensen D, Forest-Lalande L, O’Dea J, Varga, M et al. Best practice recommendations for the prevention and management of skin tears. Foundations of Best Practice for Skin and Wound Management. A supplement of Wound Care Canada 2018b; Available at: [https://www.woundscanada.ca/docman/public/health-care-professional/bpr-workshop/552-bpr-prevention-and-management-of-skin-tears/file].

- Stephen-Haynes J. Skin tears: An introduction to STAR. Wound Essentials 2013; 8(1):17–23.

- Kottner J, Cuddigan J, Carville K, Balzer K, Berlowitz D, Law S, et al. Pressure ulcer/injury classification today: An international perspective. J Tissue Viability 2020b; 29(3):197–203. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2020.04.003

- Payne RL. Martin ML. Defining and classifying skin tears: Need for a common language. Ostomy Wound Manag 1993; 39(5):16–20.

- Chaplain V, Labrecque C, Woo KY, LeBlanc K. French Canadian translation and the validity and inter-rater reliability of the ISTAP Skin Tear Classification System. J Wound Care 2018; 27(9):15–20. doi:10.12968/jowc.2018.27.Sup9.S15

- Skiveren J, Bermark S, LeBlanc, K, Baranoski S. Danish translation and validation of the International Skin Tear Advisory Panel skin tear classification system. J Wound Care 2015; 24(8):388–92. doi:10.12968/jowc.2015.24.8.388

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Holloway S, Langemo, D, Regan, M. A descriptive cross‐sectional international study to explore current practices in the assessment, prevention and treatment of skin tears. Int Wound J 2014; 11(4):424–30. doi:10.1111/iwj.12203

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Holloway S, Langemo, D. Validation of a new classification system for skin tears. Adv Skin Wound Care 2013a; 26(6): 263–5. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000430393.04763.c7

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff 2013; 32(2):207–14. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061

- Lichterfeld A, Hauss A, Surber C, Peters T, Blume-Peytavi U, Kottner, J. Evidence-based skin care. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015; 42(5):501–24. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000162

- Stechmiller JK. Understanding the role of nutrition and wound healing. Nutr Clin Pract 2010; 25(1):61–8. doi:10.1177/0884533609358997

- Ghosh A, Coondoo A. Systemic side effects of topical corticosteroids. In A treatise on topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 241–9.

- Idensohn P, Beeckman D, Santos VLCdG, Hevia H, Langemo D, LeBlanc K. et al. Ten top tips: Skin tears. Wounds Asia 2019b; 2(2):20–4.

- Wounds UK [Internet]. Best practice statement: Addressing skin tone bias in wound care: assessing signs and symptoms in people with dark skin tones. 2021. Available at: [https://www.wounds-uk.com/resources/details/addressing-skin-tone-bias-wound-care-assessing-signs-and-symptoms-people-dark-skin-tones].

- Wounds UK [Internet]. Best practice statement: The use of topical antimicrobial agents in wound management. 2013. Available at: [https://www.wounds-uk.com/resources/details/best-practice-statement-use-topical-antimicrobial-agents-wound-management].

- Kapp S, Santamaria N. The effect of self-treatment of wounds on quality of life: A qualitative study. J Wound Care 2020; 29(5):260–8. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.5.260

- Dowsett C, Newton H. Wound bed preparation: TIME in practice. Wounds UK 2005; 1(3):58–70.

- Ewart J. Caring for people with skin tears. Wound Essentials 2016; 11(1): 13–7.

- Dissemond J, Gerber V, Lobmann R, Kramer A, Mastronicola D, Senneville E, et al. Therapeutic index for local infections score (TILI): A new diagnostic tool. J Wound Care 2020; 29(12):720–6. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.12.720

- White R, Cutting KF [Internet]. Modern exudate management: A review of wound treatments. World Wide Wounds. Available at: [https://www.worldwidewounds.com/2006/september/White/Modern-Exudate-Mgt].

- Nair HKR, Chong SSY, Kamis SAB, Zakaria AMB. Clinical evaluation of a barrier cream in periwound skin management. Wounds Asia, 2020; 3(3):64–7.

- Van Tiggelen H, LeBlanc K, Campbell K, Woo K, Baranoski S, Chang YY, et al. Standardizing the classification of skin tears: Validity and reliability testing of the International Skin Tear Advisory Panel Classification System in 44 countries. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183(1):146–154. doi:10.1111/bjd.18604

- Van Tiggelen H, Kottner J, Campbell K, LeBlanc K, Woo K, Verhaeghe S, et al. Measurement properties of classifications for skin tears: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2020; 110:e103694. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103694

- Strazzieri-Pulido KC, Santos VLCdG, Carville K. Cultural adaptation, content validity and inter-rater reliability of the “STAR Skin Tear Classification System”. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2015; 23(1):155–161. doi:10.1590/0104-1169.3523.2537

- Van Tiggelen H, Alves P, Ayello E, Bååth C, Baranoski S, Campbell K, et al. Development and psychometric property testing of a skin tear knowledge assessment instrument (OASES) in 37 countries. J Adv Nurs 2021; 77(3):1609–1623. doi:10.1111/jan.14713