Volume 23 Number 2

Engaging the person with a lower leg skin tear in the wound-healing journey: A case study

Marlene Varga, Kimberly LeBlanc, Leslie Whitehead

Keywords skin tears, person-centred care, self-management, engagement, involvement, and wound care

DOI 10.35279/jowm2022.23.02.02

Abstract

Background Skin tears are common acute wounds found among aging populations and most commonly occur over the extremities. Along with increased age, risk factors include general health, mobility and skin condition. The ageing of the world’s population means that the burden of skin tears will continue to increase; therefore, a focus on awareness, prevention and evidence-informed wound management is imperative.

Aim To present a collaborative case study report of a patient in the community setting with a Type 1 skin tear.

Method This case report includes the patient (Leslie) as a co-author, to bring the experience of the person in her own words to the forefront in her journey towards healing in a community setting.

Results Leslie was unsure of how to care for her skin tear and felt frustrated by the variety of instructions and inconsistent approaches to her skin tear management. Decisions around her care were made without attention to her involvement. Leslie’s own words describe her experiences in the care of this initial acute wound that became hard-to-heal, but eventually closed.

Conclusion This case study captures the impact of hard-to-heal skin tears on the individual and identifies gaps and opportunities in wound care provision. Clinicians can reflect on their care delivery models to ensure that they provide patient-centred care.

Implications for clinical practice This case study may increase awareness among patients, providers, educators and policymakers of how we can better prevent and care for persons with skin tears and involve them in all aspects of care.

INTRODUCTION

The following case study is unique in that the individual in question is a contributing author of the manuscript. Her willingness to collaborate was based on her desire to share her journey with a skin tear, in hopes that it will inspire healthcare professionals to engage patients in their own care.

Person involvement and shared care encompasses approaches and interventions that may assist patients in participating in care planning, decision-making and care delivery.1 This approach values the person as an active participant, rather than a passive recipient of care.2 Person involvement can not only improve wound care outcomes, but also reduce overall health costs and improve quality of life.3 Under every dressing lies a story, and behind every clinical scenario there is a person with a wound waiting to be heard.4 This case presentation aims to involve the person with the skin tears actively in the presentation of her skin tear journey in her own words.

Background

Skin tears are common acute wounds found among aging populations and most commonly occur on the extremities.5,6 The International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP) defines skin tears as ‘a traumatic wound caused by mechanical forces, including removal of adhesives. Severity may vary by depth (not extending through the subcutaneous layer)’.7,8 In Canada, there are only limited studies estimating the prevalence of skin tears across healthcare settings. The prevalence among long-term care (LTC) settings is estimated to be between 14.7% and 22%9–12, and it is 30% in palliative care;13 the burden of skin tears in other Canadian healthcare settings is not known.

ISTAP developed a Skin Tear Risk Framework to aid in the risk assessment and prevention of skin tears.14 The framework indicates important risk factors to consider, including general health, mobility and skin condition, with the presence of one or more factors placing the individual at higher risk and prompting risk-reduction actions. LeBlanc et al.15 concluded that, within the three risk factors previously mentioned, individuals with the highest risk of skin tears included those suffering from chronic or critical disease, aggressive behaviour, dependence on others for activities of daily living, history of falls, history of a previous skin tear, displaying skin changes associated with aging and signs of photo damage. Skin changes, including ecchymosis, senile purpura, skin atrophy, photodamage and stellate pseudoscars, ultimately result in increased skin tear risk.16 Changes with ageing can also decrease sensation and lead to an increased risk of mechanical trauma.17 The ageing of the world’s population means that the burden of skin tears will continue to increase; therefore, a focus on awareness, prevention and evidence-informed wound management is imperative.

Individuals, caregivers or healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and practices pertaining to skins tears, their physical environment and local healthcare policies will further influence the incidence of skin tear development. Commonly, the focus for skin tear prevention is centred around the LTC sector, with little attention paid to those living in the community, as reflected in the lack of Canadian community setting skin tear prevalence data. Individuals in the community need to be educated about the changes associated with aging, the impact of medications, opportunities for self-management in skin care and skin tear prevention and management. Providing patient education and involving the person with the skin tear in the care plan’s development and evaluation are imperative for supporting wound healing and improving outcomes.1

Skin tears are often underestimated and trivialised, leading to suboptimal prevention and delayed or inappropriate management.18 Although skin tears typically proceed to closure within two to four weeks17,19, comorbidities such as diabetes and oedema, in combination with aged skin, can put the individual with the skin tear at risk for a delay in wound closure and result in a chronic, non-healing wound.20 A non-healing or chronic wound can develop due to a variety of reasons, such as modifiable and non-modifiable intrinsic and extrinsic factors7, resulting in increased healthcare costs and the human costs of pain, suffering and decreased health-related quality of life.11 Not everyone is aware that living with a complex wound is challenging and affects many physical and psychosocial aspects of lives.21

Leslie’s Story

This is a case study report of a 77-year-old Caucasian female (Leslie) with a medical history of a right total knee replacement, asthma, hypertension, arthritis, osteopenia and atrial fibrillation. Her current medications include rivaroxaban, bisoprolol, montelukast, budesonide/formoterol, beclomethasone dipropinate, ipratropium bromide, telmisartan, cholecalciferol and cyanocobalamin; she is allergic to doxycycline hyclate. Leslie is a retired Registered Nurse (RN) (graduated in 1965) and last worked as an RN in 1980. She has resources to draw on when she needs help. She has a need to know about things, a penchant to ask questions and a desire to be her own advocate. Leslie is a divorced mother of two and now lives with her second husband. She enjoys walking, cooking, baking, reading, painting, knitting, movies and spending time with her children and grandchildren. Informed consent was obtained in writing from Leslie, allowing us to obtain and share wound images and recount her personal experience.

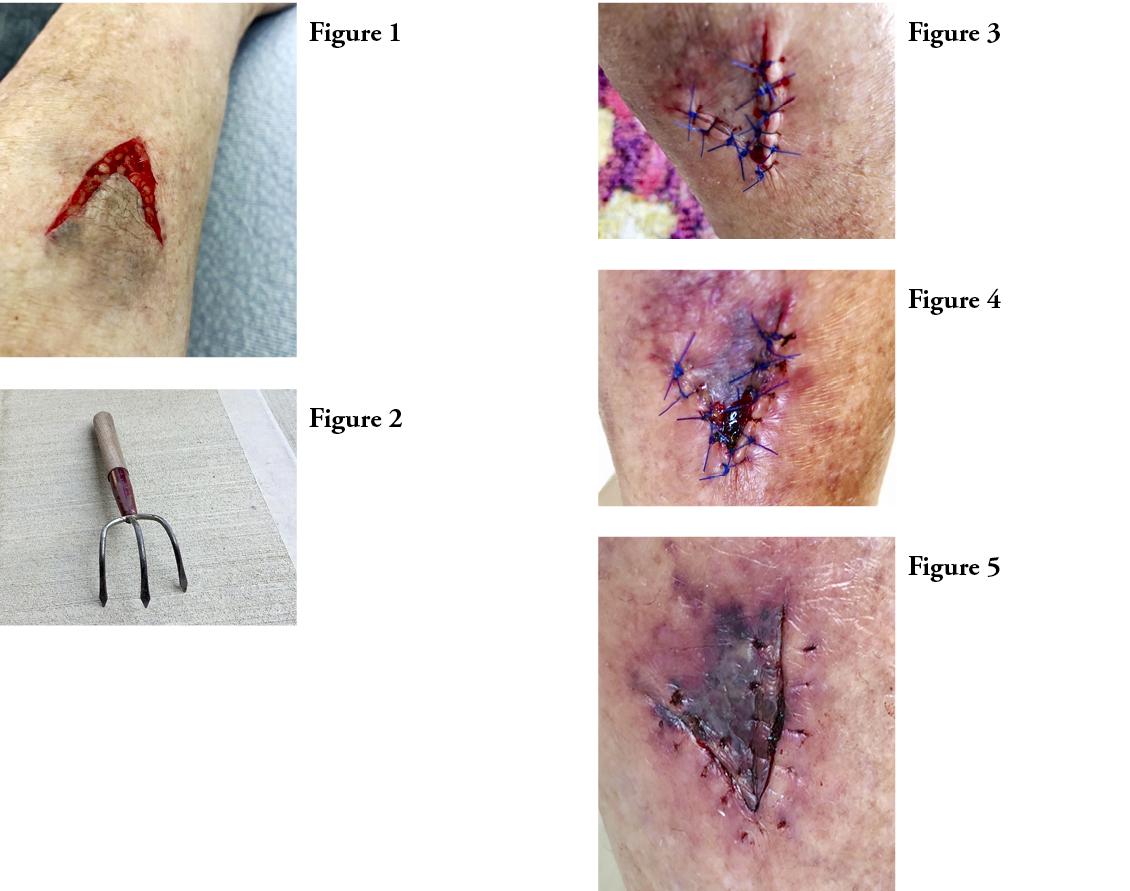

Leslie suffered a blunt force trauma resulting in a V-shaped Type 1 partial flap loss skin tear to her right lower leg (Figure 1) after she accidently caught her pant leg on a 3-prong cultivating gardening tool (Figure 2).

I had a fight with a garden tool, the attacker and [I] lost. My leg looks like it is about 200 years old. With every bump, I get a bleed and bruise. Then the skin stays discoloured.

She went to the local emergency department (ED), where the wound was cleaned with normal saline and then closed by primary intension (Figure 3). An antibiotic ointment was applied, and the wound was covered with a non-adherent mesh dressing. She received a tetanus vaccine booster and was discharged to home with instructions to clean the wound with soap and water and follow up with her family physician as needed.

The wound continued to ooze blood for approximately four days, resulting in a hematoma approximately 3 cm squared (Figure 4). Leslie reported that she felt unsure of how to manage the wound, not knowing whether to keep it covered or left open to the air. She reached out to members of the healthcare team to learn more about caring for her wound and was told to continue using the topical antibiotic ointment and a gauze dressing. She accessed the online Care at Home document from Wounds Canada to document the journey of her wound.22

On Day 6, the wound edges were inflamed, and wound moisture was increased. Leslie stopped using soap and water to clean the wound and switched to normal saline. She discontinued using the topical antibiotic ointment, switched to petroleum jelly and covered it with a non-adherent foam dressing.

On Day 10 (Figure 5), the sutures were removed and the wound edges were unattached; there was circumferential peri-wound inflammation. The petroleum jelly was discontinued, and the skin tear was covered with a non-adherent silver foam dressing.

The doctor called me later to say that she had spoken to a plastic surgeon to see if a skin graft should be considered, and the reply was ‘no’ because the wound will heal in a month (4 weeks).

The flap seems to be intact so far; however, I’m not convinced it will survive. I’m going to call home care. The Physician made a referral to the homecare and the wound clinic.

On Day 13, Leslie reported throbbing wound pain in the night. The peri-wound remained inflamed. Her lower leg was slightly oedematous, and there was scant wound drainage. She had planned on going back to the ED, but decided on a ‘wait and see approach’. She was spending the day with her grandchildren and did not want to change her plans, so she relied on homecare to follow-up.

I see that if the flap is dying or already dead that it should probably be debrided. Let’s hope the silver will work some magic and at least settle down the surrounding tissue: living in hope.

Leslie continued to wait a for a wound specialist visit and a lower leg assessment, which she thought should be done. She elevated her affected leg to manage the slight oedema. The skin tear and surrounding area felt itchy and prickly, with occasional sharp, stabbing pain.

If the flap is dying or dead, is it best to leave it sealed in place to keep the wound covered while it heals under it or is it better to debride and remove it exposing the inner tissue and risk infection? Also, I cannot see the wound clearly because of the location on my leg and the angle in which I look at it. I feel sometimes that my injury is treated as a minimal inconvenience, however it seems very serious and upsetting to me. I am worried and concerned about infection and the healing process seems to be very slow. I’m keeping busy with grandchildren though!

Day 19:

Homecare was here today and changed the dressing; I find my wound is looking better to me; not so red all around the perimeter tissue and has the feel of itchiness of healing. Is it wishful thinking on my part? Homecare will come twice a week, so will be here again next Tuesday. The gal hinted that I could do my own dressing, which I can, but I want them to monitor it until I get a response from the wound care specialist.

Day 26:

The homecare nurse said she talked to Wound Care and she said surgical debridement would be too painful so they suggested gel. They did not discuss doing debridement in my home. They are not coming till Monday to do that (today is Friday). I asked for a lower leg assessment, so homecare felt my pedal pulses and said it was strong and everything was ok. I’m still waiting for call from wound care clinic. I manage to wear my compression stocking that was recommended but only in the cooler weather. I’m doing quite well considering. I’m certainly not getting anywhere with evidence-based practice here though. Slow and steady but not very pretty.

Day 30:

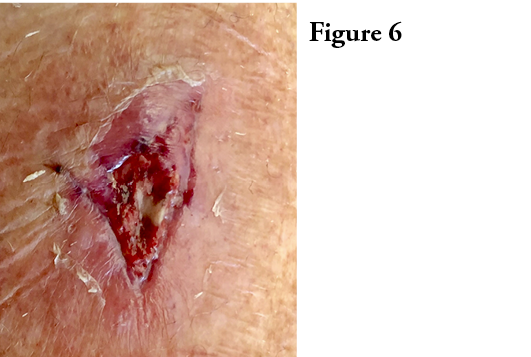

With the dressing change today the entire flap sloughed off! (Figure 6). Guess it was time. Homecare was here and didn’t put gel on today. They will be back on Friday. Time to relax.

The Homecare nurse noted some hyper granulation tissue in the wound. I asked about putting some gel on but she felt that the wound was too moist, so she wanted to just put dry gauze on it today. I wasn’t sure if it should be completely dry for 4 days, so she compromised and put a very small piece of silver mesh across the top area. Overall, I think it is healing slowly.

The dressing protocol was subsequently changed by homecare to dry gauze, to cover the wound.

Day 40:

The dry gauze dressing had to be soaked off, the wound itself looked quite dryish but healing. Homecare really wanted to leave it with a dry dressing and suggested the hyper granulation was much better and it was close to being healed. I did insist on one more silver mesh dressing, which she did put on; she said it will take longer to heal. Homecare will not come next Tuesday as I have my appointment with the Wound Care Clinic next Wednesday. That will be day 45!

Day 45:

I had my appointment at the Wound Clinic yesterday and was there for almost 3 hours. The fellow who did all the work and prep of my wound was a physiotherapist who has been trained to work there because of nurses being called to work with Covid patients. He manually debrided the sheets of dead skin from all around the wound and removed dead tissue from in the wound to clean it up. The edges are certainly healing, but there is still a fairly deep hole or two in the middle. I had a session with the Dietician who went over my diet and diverticulosis and constipation issues and reminded me to eat protein with every meal to help healing and gave me tip sheets about foods to eat to promote healing and increase fibre. Then I saw the doctor who thought that because of my age that I should wear stronger compression so they put on a silver mesh topped with a small foam pad then snuggly wrapped my leg…toes to knee with 2-layer compression bandage. I have an appointment to return to the clinic in 2 weeks, and they are going to give homecare instructions of what to do. I’ll see if I hear from homecare tomorrow as that is my regular day. So on I go with hope that the holes will fill in eventually and a totally healed wound will be the outcome…..sooner than later!

Day 60:

I went for my second visit to the Wound Clinic today. It has been 8 1/2 weeks now since the injury and I can say I am getting really tired of this. The compression wraps are extremely uncomfortable, although I hope they are helping. Today at the clinic they suggested I order new compression stockings. It looks so different than it did at last change. I finally had a chance to talk to the pharmacist today about a steroid ointment. I will pick up a small tube tomorrow and will have to convince homecare to put it on for me when they change the dressing and wrap the lite compression wraps.

I managed to obtain the steroid ointment from the pharmacy and have been applying it on my own for two applications while wearing my compression stockings. With some advice from a friend experienced in wound care I switched to using a bandaid like dressing (hydrocolloid it’s called) which seems to work out fine. I just passed the 12-week mark. I am doing these dressing changes myself and homecare will come once a week to monitor the wound. The wound care clinic said they will phone me in 2 weeks to see how things are going. I switched to cleaning the wound with iodine and after doing that it looks a little strange to me (Figure 7): like an abstract painting. It seems to me it is getting very close to being done. I am overall doing well but I am somewhat confused by all the different instructions and approaches to my wound. I think that has been the most frustrating part of this journey.

Day 99:

Fourteen weeks and my wound has finally closed and in the final stages of healing! This was much different than the original 28-day estimate (Figure 8). It I had been told at the beginning of this journey that it would take this long, I wouldn’t have believed it! I am so grateful for the care and attention that I received from the various healthcare providers. However, as a senior with other health complications, I know it would have been less stressful and more encouraging for me if there had been better understanding and a more consistent approach in the care protocol for my wound by everyone involved. I suspect updated information and education is the key for everyone from the attending emergency physician, wound clinic and homecare providers involved.

DISCUSSION

Leslie’s journey was complex. The initial ED visit resulted in the application of sutures to close the wound via primary intension. Of paramount importance was avoiding any further risks of trauma; therefore, it was recommended to avoid the use of skin closure strips and sutures for wound closure.7 It has been documented elsewhere that sutures and staples are not recommended for skin tear management, due to the fragility of elderly skin.18 Other methods of wound closure may need to be considered, such as topical skin glue23 or healing by secondary intention. In addition, traditional adhesive strips are not advised, due to their adhesive nature, which increases the risk of skin injury.23,24

The decision on how to close a Type 1 skin tear is subjective, and ED physicians must make judgement calls based on the presentation of the wound, the peri-wound skin and the risk of infection. It must be noted that there are no clinical trials to date comparing skin tear outcomes of wounds closed with sutures, staples, skin closure strips, cyanoacrylates or other topical dressings, and that best practice recommendations are based on experts’ opinions.23

Leslie’s skin tear became chronic and complicated due to flap failure, lower leg oedema, a dry wound bed and hypergranulation tissue. LeBlanc et al.9 hypothesised that possessing skin tear risk factors will not equate to the development of a skin tear or chronicity of the skin tear, if one develops other mediating factors, such as the knowledge, attitudes and practices of the individual, caregiver and/or healthcare provider, coupled with the system policies that will influence skin tear outcomes. Leslie highlighted that she was unsure if evidence-based wound management strategies were consistently applied in her case. There was inconsistent support for the principle of moist wound healing and a missed opportunity to enhance self-managed care and knowledge to increase understanding of the complex wound-healing process. These gaps in care left Leslie confused, tired and frustrated, as she felt that her skin tear was trivialised throughout the care process. The care providers cared about her wound and wanted her wound to heal, yet they minimised her wound and did not identify that skin tears have the potential to become chronic and complex. With some background knowledge, she felt that she had to convince providers to support moist wound healing and the transition to a steroid ointment. The use of topical corticosteroid ointments has been documented in the literature as a fast and relatively painless method for managing hypergranulation.25,26

Although Leslie is a retired nurse, there were gaps in her understanding of the wound-healing trajectory. As many methods of treatment have changed since Leslie’s actual nursing days, she had the expectation that the skin tear would heal within four weeks. She noted, ‘Being an old nurse and being an old patient are very different situations’.

A needs assessment of patients and caregivers should be performed and documented, including baseline information pertaining to knowledge, beliefs, health practices and perceived learning needs from patients, families and caregivers.7 Given that the greatest risk factor for developing a skin tear is a previous history of a skin tear9, an integral part of any management plan should include skin tear prevention strategies. Prevention strategies can include moisturising the skin twice per day, to add moisture to dry skin.27,28

The key areas of skin tear prevention and management include primary prevention, identifying and treating the cause, addressing patient- and family-centred concerns, determining healing potential and providing local wound care. The ISTAP suggests that the principles of Wound Bed Preparation and Tissue, Infection/Inflammation, Moisture Balance, and Edge Effect (TIME) be used to guide wound assessment and management.29,30 Moist wound healing is imperative, as skin tears tend to be dry wounds31, and moist wounds heal two to three times faster than dry wounds.32 The healing of skin tears in the lower extremities can be complicated by co-existing conditions such as peripheral arterial disease and venous insufficiency.7 LeBlanc et al.31 recommended that a lower-limb assessment be undertaken in persons who present with a skin tear on the lower limb. Compression therapy should be considered in the absence of significant arterial disease.16

Weekly reassessment of the skin tear should be undertaken, and topical management adjusted accordingly. If the person with the skin tear has fragile skin, it is preferable to leave the dressing in place for up to five days, to avoid further trauma if there is a skin flap.33 LeBlanc and Woo9 conducted a pragmatic, randomised controlled clinical study to evaluate the use of silicone dressings for the treatment of skin tears. They concluded that silicone dressings (silicone contact layers or silicone foam dressings) are a superior option for the treatment of skin tears. In their study, it was reported that skin tears healed almost two times faster with silicone dressings, compared to conventional nonadherent dressings over the course of three weeks. Furthermore, the proportion of healed subjects was almost three times higher in the silicone treatment group. The wound management plan requires a collaborative interdisciplinary approach with timely referral to an appropriate specialist if the skin tear fails to progress or deteriorates.34

It has been reported that there is a lack of attention to skin tears across all healthcare settings, and the lack of prevalence data pertaining to community settings reflects that this is especially true in the homecare sectors.7 Given our aging population and the increase in the number of individuals who choose to stay in their own homes, rather than transition to a retirement home or LTC facility, it is imperative that we raise awareness of skin tears among this population.7 It is also imperative that we engage and involve persons with skin tears in the wound-healing process and support them with education, encouragement and self-management strategies when appropriate. A person who has experienced a skin tear will be at risk for future skin tears; therefore, adopting a self-care checklist for prevention is recommended to help them monitor their skin health and subsequent complications.31,35 With the above in mind, an important next step and future goal for Leslie will be to focus on preventing further skin tears.

Living with a wound is challenging and impacts many aspects of a person’s life.21 This case study captures the impact of hard-to-heal skin tears on the individual and has identified gaps and opportunities in wound care provision. Clinicians can reflect on their care delivery models to ensure that the individuals are at the centre of care and are supported in being active participants in care and decision-making. In the current system, there is a lack of coordinated case management for wounds, as a variety of providers with varying levels of knowledge and experience that interact with patients. This is a reality, especially in the community care setting. Implementing skin tear prevention and treatment pathways and consistently involving patients in the centre of care are not yet consistently applied in practice.

In this case study, Leslie might have benefited from support for greater involvement and shared decision-making related to dressing choice, lifestyle management and the consistent use of an evidence-based skin tear management and prevention pathway.

To support patient involvement in all wound types, public awareness and education needs to be increased. The purpose of this case study was not to point a finger of blame or to criticise the care received, but rather to present the lived experience of someone in the community with a skin tear and to raise awareness among providers, educators and policymakers related to these complex wounds.

CONCLUSION

Skin tears are under-recognised acute wounds that have the potential to become non-healing, complex chronic wounds if not adequately assessed, classified and treated with evidenced-informed care. The effect of skin tears on a person’s quality of life is not fully known, and gaining knowledge of a person’s perspectives, experiences and voice requires further research. Providers, policy makers, patients and caregivers can refer to the ISTAP website for the most up-to-date information on skin tears.36

I have very strong feelings and much gratitude about the fact that if I didn’t have the opportunity to seek your advice, guidance and new research info about wound care especially flap wound care that I would not have had a clue as to whether I was getting good care or to question the protocol so thank you once again for your help and support. Moist wound healing was totally new to me!

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

- Wound management plans should be patient-centred, with open communication to support opportunities for involvement between health-care providers and the individual suffering with the wound.

- The importance of a holistic assessment, including a complete lower leg assessment, moist wound healing and the application of compression therapy (if indicated) should not be overlooked.

- Mediating factors such as knowledge, attitudes and practices of the individual, caregiver and/or healthcare provider, coupled with system policies and standardised practices, can influence skin tear outcomes.

Future research

- There is a need for clinical trials comparing skin tear outcomes of wounds closed with sutures, staples, skin closure strips, cyanoacrylates or other dressings.

- Research on skin tears remains in its infancy. More research is needed to fully understand the lived experience of having a skin tear.

- The effect of skin tears on a person’s quality of life is not fully known, and gaining knowledge of a person’s perspectives, experiences and voice requires further research.

Author(s)

Marlene Varga, MSc, RN, BScN, Covenant Health, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Kimberly LeBlanc, PhD, RN, NWSOWN, WOCC © FCAN, Academic Chair, Wound, Ostomy and Continence Institute

Association of Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada

Leslie Whitehead (retired Registered Nurse), Case study participant, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Correspondence: varga.blumarlin@gmail.com

Conflict of interest: None

References

- Moore Z, Kapp S, Sandoz H, Probst S, Milne C, Meaume S, et al. A tool to promote patient and informal carer involvement for shared wound care. Wounds Int 2021; 12(3): 86–92.

- Moore Z, Bell T, Carville K, Fife C, Kapp S, Kusterer K, et al. International best practice statement: Optimising patient involvement in wound management. Wounds Int 2016 1-19.

- Hibbard J. and Gilburt, H. Supporting people to manage their health. An introduction to patient activation. King’s Fund. London 2014. Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1716007/supporting-people-to-manage-their-health/2447678/ on 17 June 2022.

- Frank AW. The standpoint of storyteller. Qual Health Res 2000; 10(3):354–65.

- Hawk J, Shannon M. Prevalence of skin tears in elderly patients: A retrospective chart review of incidence reports in 6 long-term care facilities. Ostomy/Wound Manag 2018; 64(4):30–6.

- Vanzi V, Toma E. Recognising and managing age-related dermatoporosis and skin tears. Nurs Older People 2018; 30(3): 26-31.

- LeBlanc K, Campbell KE, Wood E, Beeckman D. Best practice recommendations for prevention and management of skin tears in aged skin: An overview. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019; 45(6):540–2.

- Van Tiggelen H, LeBlanc K, Campbell K, Woo, KY, Baranoski, S, Chang, Y, et al. Standardizing the classification of skin tears: Validity and reliability testing of the International Skin Tear Advisory Panel Classification System in 44 countries. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183(1):146–54.

- LeBlanc K, Woo KY, VanDenKerkhof E, Woodbury, G. Risk factors associated with skin tear development in the Canadian long-term care population. Adv Skin Wound Care 2021; 34(2):87–95.

- Woo K, LeBlanc K. Prevalence of skin tears among frail older adults living in Canadian long-term care facilities. Int J Palliat Nurs 2018; 24(6):288–94.

- LeBlanc K, Christensen D, Cook J, Culhane B, Gutierrez O. Prevalence of skin tears in a long-term care facility. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013; 40(6):580–4.

- Woo KY, Sears K, Almost J, Wilson R, Whitehead M, VanDenKerkhof EG. Exploration of pressure ulcer and related skin problems across the spectrum of health care settings in Ontario using administrative data. Int Wound J 2017; 14(1):24–30.

- Maida V, Ennis M, Corban J. Wound outcomes in patients with advanced illness. Int Wound J 2012; 9(6):683–92.

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Christensen D, Langemo D, Sammon MA, Edwards K, et al. International Skin Tear Advisory Panel: A tool kit to aid in the prevention, assessment, and treatment of skin tears using a Simplified Classification System©. Adv Skin Wound Care 2013; 26(10):459–76.

- LeBlanc K, Woo KY, VanDenKerkhof E, Woodbury MG. Skin tear prevalence and incidence in the long-term care population: a prospective study. J Wound Care 2020; 29(Sup7):S16–22.

- LeBlanc K, Langemo D, Woo KY, Campos HMH, Santos V, Holloway S. Skin tears: Prevention and management. Br J Comm Nurs 2019; 24(Sup9):S12–8.

- Campbell KE, Baronoski S, Gloeckner M, Holloway S, Idensohn P, Langemo D et al. Skin tears: Prediction, prevention, assessment and management. Nurse Prescribing 2018; 16(12):600–7.

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S. Skin tears: State of the science: Consensus statements for the prevention, prediction, assessment, and treatment of skin tears. Adv Skin Wound Care 2011; 24(9):2–15.

- Bryant R, Nix D. Acute and chronic wounds. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, Inc; 2007.

- Tomic-Canic M, Levine J. Skin: An essential organ. In: Baranoski S. & Ayello, EA Wound care essentials: Practice principles 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Costa IG, Phillips C, Spadoni M-M, Botros M, Camargo-Plazas P. Patients’ voices, stories and journeys of navigating social life while having and managing complex wounds: A knowledge mobilization project. Wounds Canada 2021; 19 (2):354–65.

- Wounds Canada [Internet]. Wounds Canada care at home series: Changing a dressing. Available at: [https://www.woundscanada.ca/patient-or-caregiver/care-at-home-series].

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Christensen D, Langemo D, Edwards K, Holloway S, et al. The art of dressing selection: A consensus statement on skin tears and best practice. Adv Skin Wound Care 2016; 29(1):32–46.

- Stephen-Haynes J, Callaghan R. The prevention, assessment and management of skin tears. Wounds UK 2017; 13(2):58-66.

- Ae R, Kosami K, Yahata S. Topical corticosteroid for the treatment of hypergranulation tissue at the gastrostomy tube insertion site: A case study. Ostomy/Wound Manag 2016; 62(9):52–5.

- Saikaly SK, Saikaly LE, Ramos‐Caro FA. Treatment of postoperative hypergranulation tissue with topical corticosteroids: A case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther 2021; 34(2):e14836.

- Awank Baki D, Avsar P, Patton D, O’Conner T, Burdi A, Nugent L, et al. What is the impact of topical preparations on the incidence of skin tears in older people? A systematic review. Wounds UK 2021; 17(2):33-43.

- Carville K, Leslie G, Osseiran-Moisson R, Newall N, Lewin G. The effectiveness of a twice-daily skin-moisturising regimen for reducing the incidence of skin tears. Int Wound J 2014; 11(4):446–53.

- Schultz GS, Sibbald RG, Falanga V, Ayello EA, Dowsett C, Harding K, et al. Wound bed preparation: A systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen 2003; 11:S1–28.

- Sibbald RG, Goodman L, Woo KY, Krasner DL, Smart H, Tariq G, et al. Special considerations in wound bed preparation 2011: An update. Adv Skin Wound Care 2011; 24(9):415–36.

- LeBlanc K, Campbell K, Beeckman D, Dunk A, Harley C, Hevia Campos H, et al. [Internet]. Best practice recommendations for the prevention and management of skin tears in aged skin. London: Wounds International; 2018. Available at: [https://www.woundsinternational.com/uploads/resources/57c1a5cc8a4771a696b4c17b9e2ae6f1.pdf].

- Swezey L [Internet]. Moist wound healing. Wound Eduators.com; [2014 December 12]; Available at: [https://woundeducators.com/wound-moisture-balance/].

- Stephen-Haynes J, Carville K. Skin tears made easy. Wounds Int 2011; 2(4):1–6.

- Idensohn P, Beeckman D, Conceição VL, de Gouveia Santos HH, Campos DL, LeBlanc K, et al. Ten top tips: Skin tears. Wounds Int 2019; 10(2):6–10.

- LeBlanc K, Beeckman D, Campbell K, Hevia Campos H, Dunk A-M, Gloeckner M, et al. Best practice recommendations for prevention and management of peri wound skin complications. Wounds Int 2021; 1-21.

- International Skin Tear Advisory Panel [Internet]. Available at: www.skintears.org