Volume 17 Number 2

Sustaining the renal nursing workforce

Kathy Hill, Kim Neylon, Kate Gunn, Shilpa Jesudason, Greg Sharplin,

Anne Britton, Fiona Donnelly, Irene Atkins and Marion Eckert

Keywords Renal, workforce, nurse, nephrology

For referencing Hill K et al. Sustaining the renal nursing workforce. Renal Society of Australasia Journal 2021; 17(2):5-11.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/rsaj.17.2.5-11

Submitted 20 May 2021

Accepted 27 July 2021

Abstract

Background The prevalence of kidney disease continues to increase, as does the acuity of kidney care. Patients with kidney failure are older, sicker and less mobile. Health systems are under more pressure to manage growing care needs and capacity constraints. This is likely to have an impact on nursing workforce experiences.

Aims The aim of this research was to examine nephrology nursing in South Australia to understand the impact of increasing acuity and organisational factors that may support and sustain the workforce.

Methods An exploratory semi-structured qualitative approach, facilitating eight focus groups with 36 nephrology nurses across six public metropolitan renal units was applied. Data were thematically analysed.

Findings Three central themes relating to nursing culture, patient acuity and organisational factors that impact the nursing workforce were identified. Sub-themes identified were pride and passion, teamwork and collegiality, increasing patient acuity and the lack of clinical rationalisation in kidney care, the value of a ‘flat’ hierarchy, and vulnerability during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Consequently, we identified a disconnect between institutional expectations and what the participants considered pragmatic reality. Participants reported sustained workplace pressure, a ‘triage’ approach to care, and a sense of work left undone.

Conclusion Nephrology nurses experience a gap between ‘supply and demand’ on their time, resources and workload. These findings highlight the need for further exploration of the root causes and the development of new systems to provide quality, safe and rewarding care for patients and to reduce the risk of workforce moral distress and burnout.

Introduction

The burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Australia and New Zealand is high; it is estimated to affect one in 10 people over the age of 18 (Kidney Health Australia, 2020). As reported by the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA, 2019), 26,746 Australian and New Zealanders received kidney replacement therapy (KRT) for kidney failure in 2019. The provision of KRT (haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and transplantation) nursing care is a highly specialised field (Wolfe, 2014).

However, limited research has been undertaken in the nephrology specific nursing workforce and the unmet workplace needs of nephrology nurses are not well reported (Brown et al., 2013).The shortage in the nephrology nursing workforce has largely been considered a “subset of overall supply” (Wolfe, 2014); however, with a significant number of vacancies in positions globally and increases in population level kidney failure, the nephrology nursing specialty is under additional pressure (Wolfe, 2014). Nurses in kidney care have a unique relationship with the people that they care for because of the lengthy and intensive context of care (Brown et al., 2013; Wolfe, 2014). Evidence suggests that the intensity of job burnout resulting from high stress environments is particularly high among dialysis nurses (Hayes, Douglas, & Bonner, 2015) and that job satisfaction and “organisational justice” is a critical factor that can ameliorate the negative effects of burnout (Hayes, Douglas, & Bonner, 2014; Kavurmacı, Cantekin, & Tan, 2014). Stress in nephrology nursing occurs due to increased pressure in the workplace without an associated increase in satisfaction with the job (Jones, 2014), the complexity of care, and unrealistic patient expectations (Dermody & Bennett, 2008). Inadequate staffing has been cited as a driver of stress and burnout and is correlated with nursing turnover. In turn, nursing turnover can disrupt care continuity and increase adverse events for patients (Gardner et al., 2007). Therefore, workforce renewal will be required to sustain this vitally important skilled nursing workforce and reduce turnover into the future.

Aim

The aim of this research was to examine nephrology nursing experiences in South Australia in order to understand the impact of increasing acuity on the workforce and on patients, and determine organisational factors that may support and sustain the nursing workforce.

Methods

Research methodology

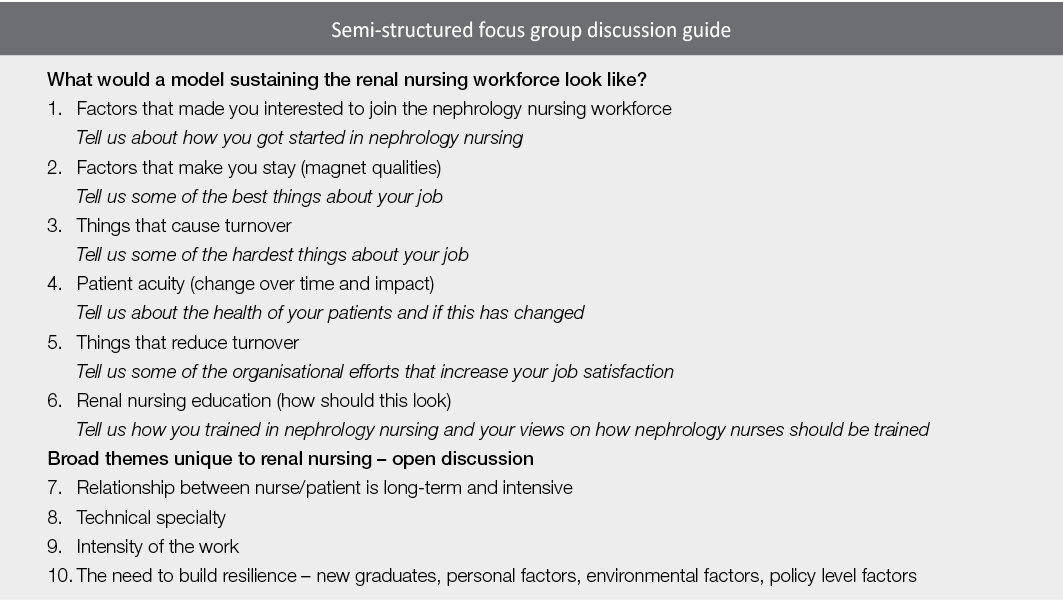

This research used a qualitative focus group methodology with nephrology nurses in both acute and satellite care settings utilising a semi-structured method (Jayasekara, 2012). A focus group discussion guide (Figure 1) was used to explore how factors such as patient acuity, complex care, workplace culture, values, time, finances, shift work, overtime, and professional development opportunities affect decision making about and satisfaction with work, while also allowing participants to raise topics they considered most important. The focus group discussion guide was developed following an extensive review of the existing literature on this topic.

Figure 1. Semi-structured focus group discussion guide

Setting

The focus groups were conducted in six South Australian renal units; they were 1–2 hours in duration and audio-recorded, and field notes were also taken. A private room in the renal unit setting was booked ahead of time to allow participants to leave their workplace to participate. Two members of the research team facilitated the focus groups, one a senior renal nurse [KH PhD], the other a qualitative ethnographic researcher with no renal expertise [KN PhD]. The benefits of dual facilitators reduced perceived prior knowledge ‘leading’ the discussion.

Sampling

Participants self-selected to participate by responding to a flyer advertising the research.

Data analysis

The audio recordings were de-identified and professionally transcribed verbatim; the researchers used NVivo 12™ to support coding trees and discourse analysis to code the data into common themes (Liamputtong, 2011). Discourse analysis uses not only the words in the transcripts but also the relationships seen between participants in the focus groups using the extensive field notes taken during the discussion. This analysis was conducted in the first instance independently by the focus group facilitators and then jointly examined for correlating themes. Data saturation was confirmed by the determination of several similar themes in all of the focus groups.

Ethical considerations

The research received approval from a human research ethics committee (CALHN HREC 12818) and all participants gave informed written consent. They were also assured of anonymity of both their identity and the specific renal unit in the reporting of the findings. Key findings in an abbreviated form were discussed with the units involved and all members of the research team before the analysis was finalised.

Findings

Thirty-six renal nurses participated in eight focus groups across six public metropolitan renal units, and included those working in leadership roles, haemodialysis, renal wards, peritoneal dialysis, transplantation and clinical trials. Participants had a range of experience in renal nursing from new graduates in their first year, mid-career nurses and those with over 30 years’ experience. Participants were predominantly female (97%, n=35).

Three broad themes were identified from the data: nursing culture, workforce education and professionalism; patient-related factors impacting on the workforce; and macroenvironmental factors impacting on the workforce.

Nursing culture, workforce education and professionalism

This theme explored the sustainability of the nephrology nursing workforce in relation to nursing culture, training modules and succession planning.

Experience versus recognised qualification: a false dichotomy in renal nurse training

There are currently two models of renal nurse education available to South Australian nursing clinicians. Trainees either undertake a university-accredited postgraduate qualification offered remotely from another state, or a hospital-based training program offered here in South Australia. Participants described fundamental flaws in this hybrid model that presents a false dichotomy:

That’s why nursing did go into the university sector to bring up the professionalism but often forgetting that it is a hands on role and we do a lot of our learning with our patients, you know, actually getting our hands dirty so to speak [FG 2].

Nurses also described the gradual and total erosion of renal specific in-place education opportunities in their units as patient numbers and acuity increased. No participants were able to describe any recent workplace-dedicated education sessions for nephrology nurses.

Training the future workforce in difficult working environments

In South Australia the three universities train a large number of undergraduate student nurses every year to address a predicted future workforce shortfall. This creates pressure on renal units already overwhelmed to find time to train the future workforce:

I could hear myself sometimes when say a student or someone would ask me something and I love teaching, I love working with students, I love working with the new grads, and I could hear this voice sometimes that was a bit snappy. I thought that’s not me, that’s awful [FG 4].

There was, however, a keen sense of the importance of developing early career nurses to sustain the renal nursing workforce, particularly given the increasing age of the nursing workforce overall.

Pride, enjoyment and passion

Nephrology nurses in South Australia consistently described themselves as proud of the work they do. They describe the capacity to “make a difference” and a passion for their specialty. Many of the more senior nurses described entering renal nursing almost by accident but “falling in love” with the specialty with very little intention of leaving:

I mean, it’s a fantastic area to work in. I didn’t know anything about renal at all before I came here. I love it. I’m passionate about renal. I love it. It’s very rewarding [FG 8].

Teamwork and collegiality

Whilst describing their challenges in an open way, participants also reported pride in their collegiality, teamwork and capacity to support each other:

Sometimes you just make yourself even later home by having a chat in the car park. Sometimes we stand in the wind and the rain and we don’t care [FG 3].

Supporting each other and working as a team is described as integral to a successful shift, especially after a challenging day. There was also consistent evidence of the extreme dedication that renal nurses have towards each other and towards their patients:

To be honest, even though I get annoyed about the staffing levels and whatever I get annoyed about that sort of side of it, it’s the patients you stay for and it’s the staff members that you stay for. Because we have got some beautiful patients and we’ve got some beautiful staff members [FG 8].

Patient-related factors impacting on the workforce

This theme explored the patient-related factors that supported the workforce culture or were a negative aspect of care.

The long-term trajectory of the patient/nurse relationship

A consistent theme raised by participants when discussing patient satisfaction was the longevity of patient/nurse relationships. Participants in all focus groups described how the long-term nature of the patient/nurse relationship generates a sense of closeness:

It’s like a family. In maintenance dialysis unit. The nurse/patient relationship is there but it’s more like a family. You’re caring like your family member [FG 2].

The nurses described continuity of care and emotional connection to their long-term patients in positive and endearing terms, often highlighting this as the most appealing aspect of renal nursing. While participants were saddened when seeing patients “at their worst” and witnessing the inevitable downward trajectory of their renal journey, their experience helping the patient and their families through that journey was often seen as a privilege and a highlight of their nursing careers. However, participants also indicated significant frustration and regret that increased patient acuity, ageing patients, and nurse/patient ratios limited their capacity to connect significantly with all patients.

Increased patient acuity, acute deterioration risk and safety

All participants reported experiencing a significant increase in patient acuity over the past few years, describing a much older, more frail dialysis population:

Patients are living longer. We have about four patients from nursing homes that come in, that you question why you even dialyse them. But the acuity of the patient is so much, is so different to what it used to be years ago. So different. They have so many more comorbidities. They yeah, they’re just more difficult. They have heart conditions that you can’t even dialyse them. You can’t even remove their fluid, so they’re in and out of hospital all the time [FG 5].

Many of the participants described patients that met medical emergency team (MET) criteria before dialysis treatment had even commenced. There was a strong sense that the units were struggling to find ways to manage these unwell patients, along with the rest of their patient group, and the use of the word ‘safe’ frequently occurred:

Just the increase in their acuity and all the comorbidities that they have and they’re getting sicker, they’re getting older, and we’re still in the process of finding ways to manage patient and staff safety and wellbeing [FG 3].

Participants also described a major change in the mobility of the patients, discussing the scene “ten or so years ago” when most people needing treatment walked into the unit and physically participated in their care. Participants remarked that this is simply no longer the case, with descriptions of lifting and carrying patients:

Three to four sling lifters, to chair lifters, it all takes time. So, let’s say we organise half an hour slots for putting on a (dialysis) patient, sometimes we might take 20 minutes to even get the stand lifters and get them into chair, let alone another 10 minutes to put on (dialysis) [FG 6].

Caseload pressure and limitations for patient care

Participants described a “conveyor belt” mentality in the dialysis units, with a sense of urgency to get people “in, on, and out” due to high caseloads. Staff described the pressing need for three shifts of patients per day and internal pressure to move patients through, and pressure on patients to rush the discharge; these factors reduced job satisfaction considerably:

I would say it was more stressful and I’d also say it impacts on your job satisfaction because you go home feeling like you haven’t done a good job even though you have and that you would have worked well within parameters. You go home and you think, on reflection, I don’t think you’re satisfied. I think you feel inept [FG 3].

Nurse/patient ratios in the setting of changing acuity

Renal nurses in South Australia accepted a standardised State-wide model for nurse-to-patient ratios several years ago that is still used to supply staff to renal units. Many of the focus group participants expressed regret regarding this agreement, as they believe it no longer reflects the actual nursing care hours needed due to the increased complexity of the people undergoing dialysis:

You do this many treatments therefore there’s this many staff and that is your barrier that you have to fight and prove that you require that extra staff member because why do you need that because you’ve only got this many patients, well that’s because this person is nearly dead and if I leave his side he’s going to be [FG 1].

Stress and responsibility

Participants overwhelmingly described a culture of chronic stress in the workplace. This was not just in dialysis units, but also in renal wards:

Like, it was so scary. Everybody was so sick and sometimes you had very little support and it was very intimidating looking after these very sick patients and sometimes you could be that second to most senior nurse as a graduate or the most senior on a night shift [FG 2].

On an afternoon shift, you never have a meal break, ever

[FG 8].

Whilst all participants described nursing leadership support, they struggled to identify any organisational support for the difficulties and challenges centred within the specialty area. Participants across the board described having to source their own replacement staff to cover sick leave or work overtime, and at times the inability to support the team:

As a Shift Coordinator you just, you can see someone and you desperately want to help them but you’ve got 7 million other things you’re trying to deal with, it’s horrible, really, really horrible, it’s just like you spend a whole day trying to put out whatever fire is burning the most at that second and it’s awful [FG 4].

The patient as an expert

Renal nurses described the uniqueness of the renal patient and their “expertise”. This was genuinely viewed as a partnership for successful treatment. An ideal model of care was seen to involve an active patient:

A lot of, most of them are a knowledgeable group about their own healthcare so they can be quite strong advocates for themselves and are willing to question and I think the staff actually like that. We all like that these patients are questioning and challenging [FG 2].

However, participants also raised a downside to this, namely patient reliance on individual staff members, as long-term relationships facilitated trust or distrust in particular staff, particularly new staff members. Newly graduated nurses described being intimidated by patients that refused to allow them to perform tasks, for example to cannulate a fistula, because of a lack of trust in their ability:

Oh, who is this person, I’ve never seen you. Do you know how to needle? I don’t think you want to needle me [FG 6].

Overall, participants described the capacity to gain trust, and the sense that the patient as an active participant in managing their chronic condition was welcomed by the nursing staff.

Macroenvironmental factors impacting on the workforce

This theme explored factors that were impacting on the workforce that were organisational and external to the participants.

Lack of clinical rationalisation in kidney care impacting on nursing morale

A factor described as increasing the pressure on the nursing workforce was their perceived powerlessness when it comes to assessing a patient as “too unwell for dialysis” and the decision not being supported by the medical staff. Participants felt that, once a dialysis pathway is chosen, irrespective of the nurses’ beliefs about the patient’s capacity to cope with that treatment, there is pressure on the nursing staff from the medical team to find a way to complete the dialysis treatment:

We have patients here that, once upon a time, wouldn’t dialyse. They are so hypotensive, for example, and you’ll ring the renal registrar but the expectation in many cases is you dialyse them [FG 3].

Sentiments surrounded the way that the participants experienced the increasingly complex ageing population, the increasing burden of all that was expected from them with patients that they felt would have been considered too unwell previously. This theme described a despondent workforce that sometimes felt that they are unable to meet the needs of all deteriorating patients at all times.

A “flat hierarchy” and respect in the workplace

Several units described a “flat hierarchy” where nephrology nurses were respected and valued by the medical teams; this created a very positive workplace culture and increased job satisfaction:

And it’s always been strongly encouraged that if you’re not happy with something miss out the middle man, women, go straight to the consultant, and I think every renal nurse would have no qualms in, whether it’s the middle of the night if they felt something unsafe was happening, giving the consultant a call [FG 2].

Many nurses attributed this to the positive attitudes of doctors towards nurses and described close collegial relationships between the nursing and medical staff; this was celebrated as a positive aspect of nephrology nursing and care coordination.

The “old model for the new reality”: physical space constraints

There is a large degree of commonly felt dissatisfaction with the physical space provisions in renal units, described here as “the old model for a new reality”. Many units report simply having inadequate space and this relates to increased patient numbers, increased use of mobility aids, and increasing numbers of patients requiring dialysis, many of whom are so ill they are in a bed that is much larger than the space designed for the treatment. This was echoed in the units that had a central nursing station and patient stations placed in a circle around this, a model commonly seen in renal units:

And you’re now putting beds in there and sometimes it could look like a war zone [FG 7].

COVID‑19 and workforce vulnerability

This research was conducted in South Australia during the COVID‑19 pandemic which, whilst creating logistic difficulties in terms of research access and social distancing, brought additional insights into the pressure on the nephrology nursing workforce as participants considered the consequences of a potential outbreak in a dialysis facility:

I guess the difference is you can’t get someone else to come and cover from anywhere else. No one else can lend a hand [FG 3].

However, participants also described a common sense of purpose in upskilling as much of the nursing workforce as possible in preparation for the pandemic:

So, that’s where we’re concentrating because we had massive changes with the COVID happening and we had lots of people coming through upskilling. So, that was a major breakthrough for us in opening our eyes into saying, “Yes, we can do this. Yes, we can change things around” [FG 6].

The global COVID‑19 pandemic brought recognition to participants of their own strong commitment to nursing, but also a perceived increased recognition of the vulnerable position nurses put themselves in to help others in the wider community:

But COVID’s been the perfect example. Like we’ve been thanked so many times. I don’t think we’ve ever been thanked, well not as many times [FG 2].

Discussion

This research found that nephrology nurse participants felt pride in their work, but often felt overwhelmed or “powerless” in the face of a rapidly changing renal patient population. Maintaining a professional identity is a strong predictor of personal accomplishment and the driving force “to keep going” (Georgios et al., 2017) and was expressed keenly by the participants of this research. However, increasing patient numbers, increasing patient acuity and physical space constraints led to the staff trying manage an old model of a dialysis unit based upon a smaller, younger and more independent cohort of patients around which renal units were designed, and not being able to successfully manage this. There is also evidence of sustained workplace pressure and a sense of work left “undone”, leading to increasing job dissatisfaction. White, Aiken and McHugh (2019) have previously discussed the interdependent concepts of working in an under-resourced setting creating stress and moral distress due to missed care in nursing (White et al., 2019), something which was evidenced in our focus group discussions.

In addition, Bong (2019) identified that the attrition rate for new graduates is a result of “moral distress”, a concept whereby the carer knows the right thing to do but is unable to do this due to institutional or resource constraints, and this is compelling enough to cause staff turnover. Whilst we spoke to graduates that were happy with their choice of specialty, senior staff indicated limitations in the training of graduates and students, particularly time restraints, that limited recruitment generally. This research also found that renal nurses wanted organisational acknowledgement, both of the new reality of renal care (compared to 20–30 years ago) and of their endeavours to combat structural constraints, to feel a sense of workplace achievement.

Hospital organisational culture has been found to be a dominant predictor of the quality of nursing care, and nurses, being a caring profession, are drawn to organisations that address “daily census” with appropriate staff patient ratios to increase the quality of care (Mudallal et al., 2017). Whilst intrinsic factors can reduce the impact of stress and burnout, critical to supporting nurses to cope with stress is addressing the macroenvironment with “adequate staffing, appropriate skill mix and support to manage extremely unwell patients” (Jones, 2014). Challenges were evident in participant experiences throughout the state, as they reported feelings of helplessness in the face of growing numbers, patient acuity and time constraints. This was most evident in concerns raised regarding patient safety and the pressure in maintaining visible composure in a chaotic environment. Nevertheless, participants overwhelmingly demonstrated pride in their work and a passion for renal care despite these structural constraints.

This research also provides evidence of a disconnect between the model of care utilised by hospitals and the increasing complexity of renal care. It highlights a need to consider alternative approaches to the delivery of renal care rather than a ‘business as usual’ service delivery that participants describe as inadequate and lowering both staff satisfaction and the quality of care for renal patients. This finding is particularly pertinent for renal staff here in South Australia, as the supply demand gap is widening, resulting in burnout and turnover (Halter et al., 2017). However, its impact could be applicable to renal nursing elsewhere where renal units may be experiencing the same increased acuity and structural constraints.

Whilst we acknowledge the inherent challenges of generalising from qualitative research, the four key findings from this research include:

- The renal nursing workforce has a strong internal supportive culture.

- The working environment and professional development opportunities need to be re-considered (larger spaces and increased training opportunities required).

- Changing patient acuity management requires modifications to the nurse/patient ratio model.

- Attracting nurses to the renal specialty is reliant on changes to the current education model and strategies to attract early career nurses to the speciality.

Limitations and strengths

We acknowledge a limitation of the focus group methodology is that participants self-selected, that senior and junior staff were interviewed together, and that being interviewed as teams could prioritise dominant voices and silence passive ones. Potentially the impact of COVID‑19 on the health system and staff could also confound some of the findings due to the contemporary pressures of the global pandemic. The strength of this research is participants from multiple sites with varying degrees of experience and the experienced facilitators.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the nephrology nurse focus groups undertaken across metropolitan South Australia found evidence of a dedicated and highly specialised nursing profession who described caring for a much larger and more complex cohort of patients under markedly different circumstances than the hospital renal unit structures and systems were designed to cope with. Consequently, a disconnect between institutional expectations and the pragmatic reality perceived by nurses caused these clinicians to feel unsupported and forced into what could be described as a ‘triage’ approach to care. Workplace culture was reported as particularly important with regard to the respect and recognition showed by senior staff both within the nursing teams, other staff such as doctors, other wards whose work intersected with renal, and the institution as a whole. This appeared to be crucial to job satisfaction and a sense of control and had an impact on their patient care. Overall, this research highlights the need for further study into the causes of changing workplace pressures and opportunities for organisations to explore and address key issues that are currently negatively impacting upon patient care and staff retention in this important nursing specialty.

Future work in this area

In addressing the nephrology nursing supply and demand issue that is emerging, research needs to focus on not just the current situation but in developing strategies to create solutions. This is vital to inform organisations how best to support the nephrology nursing workforce to ensure its sustainability. Phase 2 of our research will be investigating the sustainability of the nephrology nursing workforce using a discrete choice quantitative methodology (DCM) via a national workforce survey informed by the findings of this study. The themes developed in this qualitative work will guide the development of a DCM survey that will help us to work towards developing quantitative workforce models to understand and develop strategies to sustain the nephrology nursing workforce. Phase 2 is funded by Kidney Transplant Diabetes Research Australia and will be used to inform the National Strategic Action Plan on Kidney Disease.

Acknowledgements / Funding statement

The researchers would like to thank all of the renal nurses who participated in this study for their time, thoughts, ideas and expert opinions. This research was funded by a project specific grant from the Rosemary Bryant Foundation South Australia. Would also like to acknowledge the Rosemary Bryant AO Research Centre, University of South Australia for their support in progressing this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author(s)

Dr Kathy Hill PhD MPH Grad Cert (Neph) BN RN Lecturer in Nursing

University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Dr Kim Neylon PhD

University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Dr Kate Gunn PhD

University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Dr Shilpa Jesudason MBBS, FRACP, PhD

Central Northern Adelaide Renal Transplantation Service (CNARTS), SA, Australia

Greg Sharplin Mpsych (Org & HF) MSc (Epi)

University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Anne Britton

Clinical Practice Director, Central Northern Adelaide Renal Transplantation Service (CNARTS), SA, Australia

Fiona Donnelly

MNP Central Northern Adelaide Renal Transplantation Service (CNARTS), SA, Australia

Irene Atkins

CNM Renal Unit FMC SALHN, SA, Australia

Professor Marion Eckert PhD

University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Correspondence to Dr Kathy Hill, Lecturer in Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery City East Campus

University of South Australia

Email Kathy.Hill@unisa.edu.au

References

Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA). (2019). Annual report. South Australia: ANZDATA.

Bong, H. E. (2019). Understanding moral distress: How to decrease turnover rates of new graduate pediatric nurses. Pediatric Nursing, 45, 109–114.

Brown, S., Bain, P., Broderick, P., & Sully, M. (2013). Emotional effort and perceived support in renal nursing: A comparative interview study. Journal of Renal Care, 39, 246–255.

Dermody, K., & Bennett, P. N. (2008). Nurse stress in hospital and satellite haemodialysis units. Journal of Renal Care, 34(1), 28–32.

Gardner, J. K., Thomas-Hawkins, C., Fogg, L., & Latham, C. E. (2007). The relationships between nurses’ perceptions of the hemodialysis unit work environment and nurse turnover, patient satisfaction, and hospitalizations. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 34, 271–81.

Georgios, M., Theodora, K., Eugenia, M., Christos, T., Smaragdi, K., Athina, K., & Alexandra, D. (2017). Is self-esteem actually the protective factor of nursing burnout? International Journal of Caring Sciences, 10, 1348–1359.

Halter, M., Boiko, O., Pelone, F., Beighton, C., Harris, R., Gale, J., Gourlay, S., & Drennan, V. (2017). The determinants and consequences of adult nursing staff turnover: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 17, 824–824.

Hayes, B., Douglas, C., & Bonner, A. (2014). Predicting emotional exhaustion among haemodialysis nurses: A structural equation model using Kanter’s structural empowerment theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 2897–2909.

Hayes, B., Douglas, C., & Bonner, A. (2015). Work environment, job satisfaction, stress and burnout among haemodialysis nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 23, 588–598.

Jayasekara, R. S. (2012). Focus groups in nursing research: Methodological perspectives. Nursing Outlook, 60, 411–416.

Jones, C. (2014). Stress and coping strategies in renal staff. Nursing Times, 110, 22–25.

Kavurmacı, M., Cantekin, I., & Tan, M. (2014). Burnout levels of hemodialysis nurses. Renal Failure, 36, 1038–1042.

Kidney Health Australia. (2020). Chronic kidney disease management in primary care (4th ed). Melbourne: Kidney Health Australia.

Liamputtong, P. (2011). Focus group methodology: Principles and practice. London: Sage Publishing.

Mudallal, R. H., Saleh, M. Y. N., Al-Modallal, H. M., & Abdel-Rahman, R. Y. (2017). Quality of nursing care: The influence of work conditions, nurse characteristics and burnout. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 7, 24–30.

White, E. M., Aiken, L. H., & McHugh, M. D. (2019). Registered nurse burnout, job dissatisfaction, and missed care in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 67, 2065–2071.

Wolfe, W. A. (2014). Are word-of-mouth communications contributing to a shortage of nephrology nurses? Nephrology Nursing Journal, 41, 371–378.