Volume 18 Number 3

Renal healthcare: Voicing recommendations from the journey of an Aboriginal woman with chronic kidney disease

Alyssa Cormick, Kelli Owen, Deborah Turnbull, Janet Kelly and Kim O’Donnell

Keywords kidney journey mapping, person-centred kidney care, social and emotional wellbeing, strength and resilience, Aboriginal kidney care

For referencing Cormick A, Owen K, et al. Renal healthcare: Voicing recommendations from the journey of an Aboriginal woman with chronic kidney disease. Renal Society of Australasia Journal 2022; 18(3):88-100.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/rsaj.18.3.88-100

Submitted 7 June 2022

Accepted 21 November 2022

Abstract

Current healthcare systems often fail to recognise and address the healthcare needs of First Nations People, resulting in unacceptable gaps in health outcomes. Biomedical frameworks used to examine chronic conditions, like chronic kidney disease (CKD), focus on ill health rather than on the strengths First Nations People use to be resilient and sovereign. Healthcare systems, staff and researchers need to collaborate with First Nations People to understand and value lived experiences to best address health and wellbeing needs.

This research was carried out within Aboriginal Kidney care together: improving outcomes now (AKction). Using decolonised methods and a participatory action approach, research yarning and thematic analysis were collaboratively conducted to map the health journey of an Aboriginal woman with lived experience of kidney disease.

The woman utilised a range of strengthening factors to maintain resilience during her kidney health journey, including Ngolun/connections (to land, language, culture, spirit and ancestors; family; people who understood experiences; strong women; supportive health staff; community), Kunulun/actions (engaging with culture, taking control, advocacy and support, sharing knowledge) and Peranbun/positive mindset (identity, choosing to be strong, outlook on situation, focus). Lacking these strengths and life stressors contrastingly acted as a barrier to her resilience.

The woman’s journey acts as a case study providing recommendations for improving First Nations People’s kidney care by applying a person-centred approach. Recommendations include the need for relevant community kidney health education and awareness, early testing, treatment options on country, peer support, First Nations People healthcare staff, post-transplantation support, and holistic healthcare addressing the patients’ social and emotional wellbeing.

Introduction

The benefits of person-centred kidney care have increasingly been recognised. This has resulted in healthcare that aims to respect and respond to the preferences, needs and values of individual patients (Morton & Sellars, 2019). Despite this approach and efforts of healthcare staff, many First Nations People continue reporting disconnection and disregard by healthcare systems (Jones, Heslop & Harrison, 2020). Many First Nations People of Australia hold holistic and strengths-based perspectives of health which recognise how interconnected parts of their lives impact or promote health and wellbeing (Fogarty et al., 2018). These perspectives are inclusive of social, cultural, family and historical health determinants, extending beyond colonial biomedical models which identify the presence or absence of disease (Dudgeon et al., 2020). Healthcare systems and staff need to acknowledge cultural perspectives of social and emotional wellbeing, including impacts of colonisation, strengths and resilience of First Nations People to provide culturally responsive and person-centred care (Bryant et al., 2021).

The failure of healthcare systems to appropriately address the needs of First Nations People has resulted in unacceptable gaps in health outcomes for this cohort (Kelly et al., 2022). Historical and ongoing experiences of colonisation and racism have further influenced disparities in outcomes related to chronic diseases like chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Schwartzkopff, Kelly, & Potter, 2020). First Nations People are more likely to be diagnosed with CKD at younger ages, start renal replacement therapy (RRT), not be on the kidney transplantation work up list, and not receive kidney transplantation (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2020).

These outcomes are compounded by a higher proportion of First Nations People experiencing comorbidities and having to manage multiple health conditions, and many living in rural or remote areas requiring relocation to receive treatment. This impacts personal responsibilities, commitments, and connection to family, community and culture (Conway et al., 2018). A significant number of First Nations People with CKD also report that their diagnosis was sudden and shocking, that they received limited information which was often not culturally appropriate, that they were unfamiliar with healthcare settings, and that they experienced poor communication and cultural barriers with health staff, impacting their ability to engage and adhere to renal treatment (Hughes et al., 2019).

In addition, specific biomedical, social and behavioural risk factors impact heavily on First Nations People, increasing the incidence and complexity of CKD. Biomedical risk factors include premature births, low birth weights, under-developed kidneys at birth, genetic disorders, being overweight, and having comorbidities including heart disease and diabetes (AIHW, 2020). Social and behavioural risk factors include having poorer access to healthy foods, food security, clean water, housing and education, and engagement in higher risk behaviours such as alcohol and tobacco use and lower levels of physical activity (Kelly et al., 2022). The origins and causes of these risk factors may or may not be understood clearly by kidney health professionals, leading to fluctuating levels of professional judgement and understanding (McMullen et al., 2015).

The strength and resilience of First Nations People living with CKD and the way First Nations People navigate significant health, family, community, cultural and social complexities is also often overlooked (Schwartzkopff et al., 2020). Understanding and appreciating the ways in which individuals overcome adversities and flourish is central to holistic and person-centred care. Whole of life approaches offer new opportunities for healthcare providers, patients and families to work together, supporting people to thrive, rather than just survive, kidney care (Kelly et al., 2022). Recognising individual, family and community resiliency and strengths offers new opportunities for partnerships in healthcare interactions, improving experiences and outcomes of CKD journeys (Gregory, 2019).

Journey mapping is a process increasingly being used in health, research and education to record, plan and assess the stages of a patient’s health journey. This applies a whole of life and person-centred approach, recording information about healthcare interactions alongside other life events and experiences. This process can be used to support culturally responsive healthcare as it enables: a holistic approach of health to be applied; First Nations People’s knowledge and perspectives to be acknowledged; personal strengths and resilience to be identified; and gaps in care to be recognised and appropriately responded to in a timely way (The Lowitja Institute, 2022).

Kidney care research is increasingly focusing on care as perceived by recipients (Morton & Sellars, 2019); however, little has been published about how the social and emotional wellbeing of First Nations People can be best supported (Dingwall et al., 2019). This study aimed to map the health journey of Kelli Owen, an Aboriginal woman with kidney disease, and identify how she was strong and resilient throughout her health journey. Using a decolonising approach, Kelli was actively involved in the mapping, analysis and writing of this paper. This approach repositioned power and control in research, and enabled Kelli to share her lived experiences in ways, and to the extent to which, she was comfortable. The aim of this paper is to share Kelli’s experiences and how she managed CKD, and provide person-centred and culturally responsive recommendations for healthcare systems and staff.

Ethics

The AKction research project and this study have approval from the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (AHREC): 04-18-79, the University of Adelaide: 33394, and the Central Adelaide Local Health Network (CALHN): R20190124. Amendments were made specifically for this student research and case study, including a consent form which specifically gave the participant choice over whether or not they were identified in subsequent research publications.

Method

This research was conducted as a student’s fourth year psychology honours research project within the broader Aboriginal Kidney care together: improving outcomes now (AKction) project. The AKction research project is guided by the AKction reference group (ARG) of Aboriginal people who have lived experience of kidney disease, conducting decolonising and participatory action research (PAR) (Bateman et al., 2022). The health journey of one participant was mapped and explored in depth as a case study to provide person-centred and strengths-based recommendations for healthcare staff and services (Kushniruk, Borycki, & Parush, 2020).

Reflexivity statements

The journey mapping participant Kelli Owen and the research student Alyssa Cormick were both positioned as co-researchers and co-authors for this project. Kelli is a Kaurna, Narungga and Ngarrindjeri woman born and raised on Kaurna Yarta, Adelaide, South Australia. She has lived experience with CKD, peritoneal dialysis (PD), haemodialysis (HD) and kidney transplantation. Kelli is a member of the ARG, an advocate for First Nations patients with CKD, and is a teacher, mother, sister and friend. Kelli chose to be identified in this article to acknowledge her involvement, strengthen the findings and clinical recommendations, to be re-empowered, to have her voice and the voices of other First Nations women strengthened, and to raise First Nations sovereignty and ownership of data by linking research to a real and identifiable person.

Alyssa identifies as a woman of Dutch/Irish/British cultural background who grew up on the land of the Ngunnawal People in Canberra. Prior to this project, Alyssa had limited experience working with First Nations People or conducting research. This project was collaboratively conducted for Alyssa’s fourth year psychology honours research project. To minimise bias, Alyssa engaged in ongoing reflection and collaborated deeply with Kelli, members of the AKction project (co-author Kim O’Donnell) and research supervisors (co-authors Janet Kelly and Deborah Turnbull) to collect, analyse and interpret data, ensuring they reflected Kelli’s true experiences.

Participants

Multiple female members of the ARG were identified as potential participants. Due to her availability and interest, Kelli was identified as the sole participant whose journey would be explored in depth. The participant was positioned as a co-researcher and co-author, involved in the data collection, analysis, interpretation and write up.

Data collection

Initial consultations were conducted with ARG members to identify their priorities. Due to cultural gender considerations, it was decided that Alyssa would map the health journey of a female reference group member. Kelli provided informed consent to have her journey mapped, be audio recorded, and have ongoing involvement in the research process, including the option to choose whether she was identified or not in subsequent publications. Kelli and Alyssa planned the mapping process together, identifying their individual and collective aims and how they could be collaboratively achieved. Kelli and Alyssa used a research yarning approach to map Kelli’s journey, while writing out events on butchers’ paper, guided by the strategic health journey mapping tool (The Lowitja Institute, 2022).

Following this method, Kelli was positioned as an expert who directed mapping, yarning about events in her health journey from diagnosis to present day. Alyssa was positioned as a listener and learner, asking follow up questions for further elaboration of events (Leeson, Smith, & Rynee, 2016). Yarning was conducted over 7 hours, with breaks taken as required, while attending an AKction women’s retreat at a private property in Mount Pleasant, South Australia. The health journey map was written up by Alyssa and provided to Kelli.

Data analysis

Alyssa generated initial codes and themes in NVivo using deductive thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke (2013). Kelli and Alyssa collaboratively reviewed themes to coded extracts and checked that themes accurately reflected Kelli’s lived experiences. Kelli gave permission for agreed upon extracts and themes to be shared, and they were then reviewed with the research supervisors (co-authors Janet Kelly and Deborah Turnbull). Kelli provided Ngarrindjeri words for the themes. Themes were then collaboratively mapped across Kelli’s health journey, identifying her strengths and barriers to resilience in relation to major health journey events.

Results

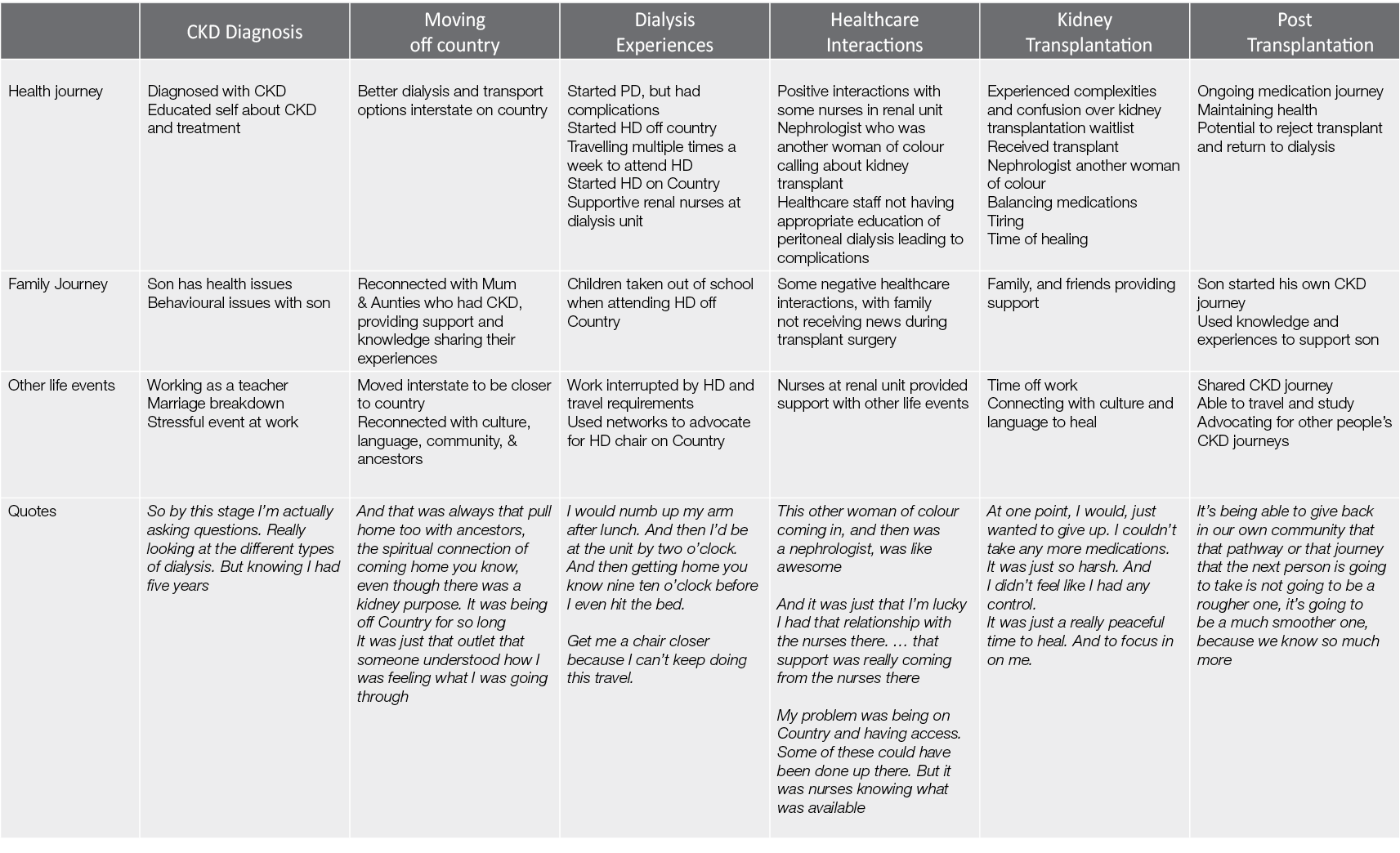

Kelli’s kidney journey involved being diagnosed with CKD, starting PD as an end stage treatment, having complications with PD, starting HD with a chair far from home, getting a HD chair on country, receiving a kidney transplantation, and ongoing post-transplantation experiences. These stages of her kidney journey were interwoven with family, friends, community, culture, work and educational experiences and obligations (Table 1).

Table 1. Kelli’s health journey, depicting what happened in her health, family and other life events across her CKD diagnosis, moving off Country, PD and HD, healthcare interactions, transplantation and post-transplantation

* Themes translated into Ngarrindjeri, the traditional language of the Ngarrindjeri peoples of the lower Murray River, lakes and Coorong South Australia, by Kelli Owen

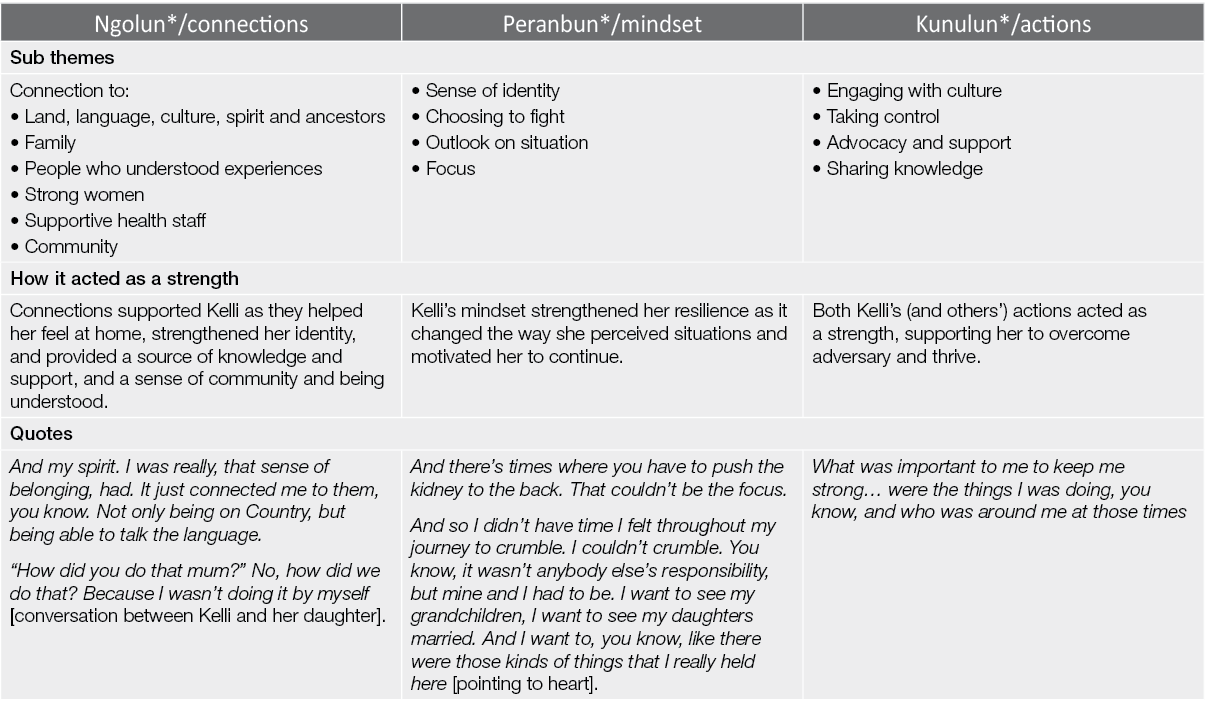

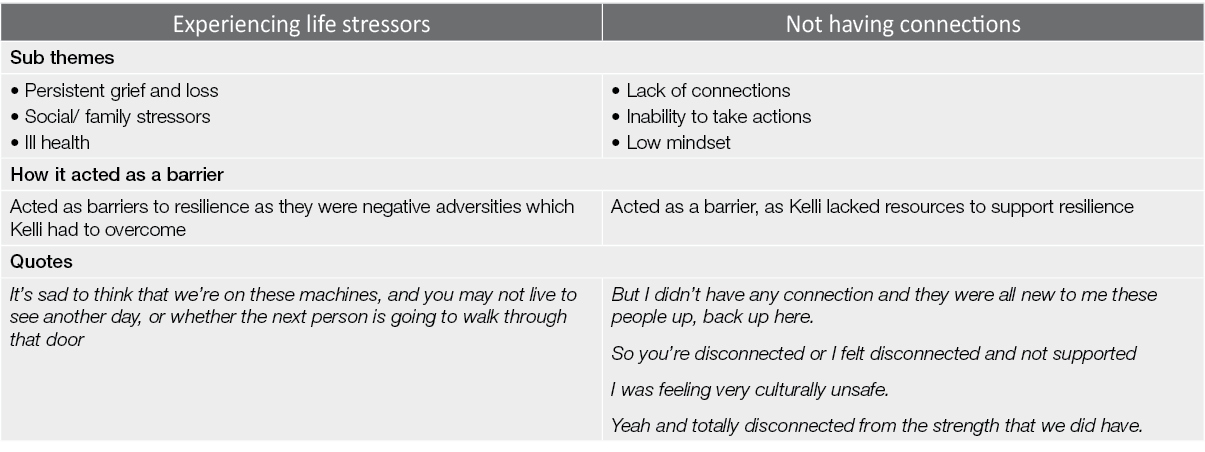

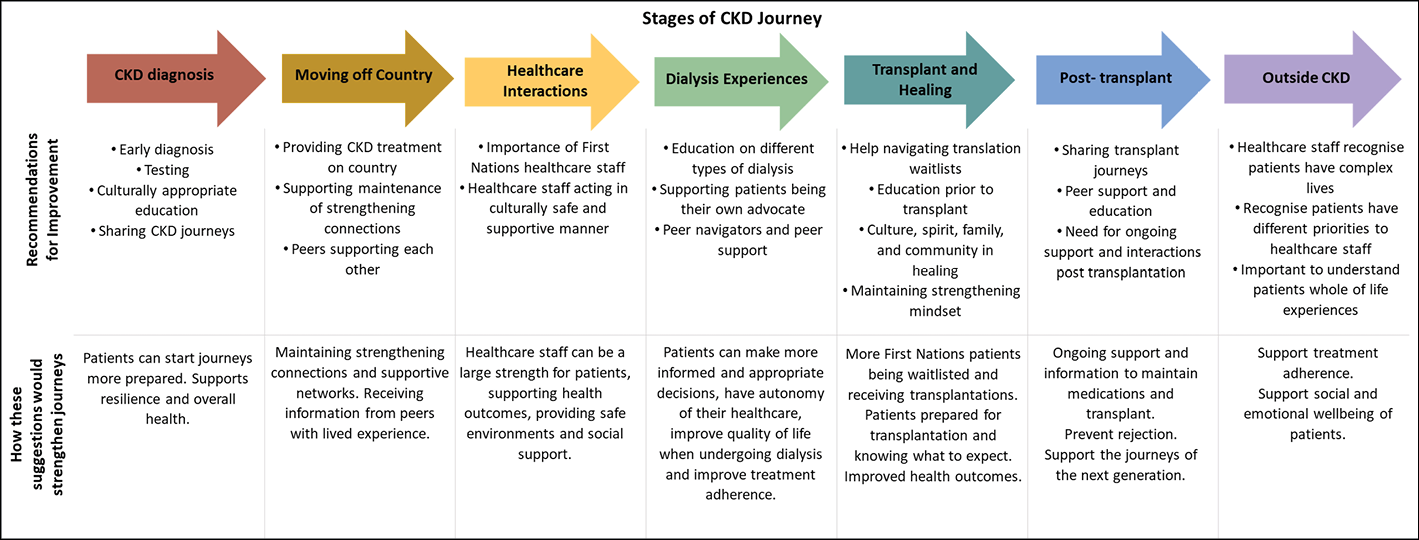

Thematic analysis identified that Ngolun/connections, Peranbun/actions and Kunulun/mindset acted as strengthening factors for Kelli (Table 2) while experiencing life stressors not having strengths acted as a barrier (Table 3) (Figure 1).

Table 2. Explanation of the strengths to Kelli’s resilience

Table 3. Explanation of barriers to Kelli’s resilience

Figure 1. Summary of recommendations from Kelli’s health journey and their implications

Discussion

CKD is an ongoing and complex condition, impacting all areas of an individual’s life (Rix et al., 2014). Findings from mapping and conducting thematic analysis on Kelli’s journey identify her experiences and the strengths she utilised to maintain resilience and thrive. Many of these strengths (Eades, 2017; Goin & Mill, 2013; Gregory, 2019; Kilcullen, Swinbourne, & Cadet-James, 2013) and experiences with kidney disease (Anderson et al., 2008; Anderson Cunningham, 2012; Anderson Devitt 2012; Rix et al., 2014; Schwartzkopff et al., 2020) are similar to those reported by other First Nations People. Mapping Kelli’s journey from her perspective addressed a gap in literature, as health journeys are rarely mapped from the perspective of First Nations People, or published with First Nations participants as co-authors (Hughes et al., 2022). Healthcare staff and services can use this case study as a reflection of how to apply a person-centred and strengths-based approach to support the social and emotional wellbeing of First Nations People with kidney disease.

CKD diagnosis

Many First Nations People are diagnosed late into their progression of CKD, requiring immediate RRT. This is reportedly a shocking experience, resulting in lacking preparation, understanding and control of what is happening (Rix et al., 2014). Kelli, contrastingly, had 5 years between diagnosis and starting dialysis. This provided her time to prepare, educate herself, connect with others who had like experiences, and come to terms psychologically with her diagnosis and its implications. Engaging with these strengthening factors, which have also been identified as strengthening for other First Nations women, promoted her resilience and supported her subsequent CKD journey (Kilcullen et al., 2013). This highlights the importance of early diagnosis, testing and education. By services increasing culturally appropriate education and awareness of CKD, individuals can start their journeys in a more prepared position, strengthening their resilience and health outcomes.

Moving off country

Many First Nations People are required to move off country to access RRT. This is reportedly stressful, with people becoming disconnected from their family, culture and community (Conway et al., 2018). First Nations People are often younger than non-First Nations Australians when starting RRT, and more likely to be female (AIHW, 2020). This move to receive treatment can significantly impact work, study commitments and children in their care. Kelli, however, returned to country between her CKD diagnosis and starting ESKD treatment. Like many other First Nations People, being on country enabled Kelli to connect with various strengthening factors that supported her resilience, including family, community, spirit, ancestors, language and culture (Dudgeon et al., 2020; Gregory, 2019). By connecting with these strengthening factors, her resilience was supported for her subsequent health journey. This highlights the importance of providing access to CKD treatments on country so that people can maintain their strengthening connections.

Some of the family members that Kelli connected with on country also had CKD, providing her with knowledge about their personal experiences. She reported that this provided her a sense of comfort, as she was able to connect with others who had had like experiences. Sharing journeys and experiences with others who have had similar experiences is an important strength for First Nations People (Kilcullen et al., 2013) that healthcare services can support by providing avenues for people to connect and advocate for and alongside each other. An example of this is peer support groups, where people with similar experiences can share and support each other. This also identifies the importance of people recording their own journeys, sharing their experiences to inform and help others and taking control of their own narratives (Kelly et al., 2022).

Healthcare interactions

There is often a disconnect between healthcare services, staff and First Nations People. Many First Nations People report communication barriers and a lack of education and understanding of their CKD condition. These gaps are often attributed to cultural barriers, the use of medical jargon, and a lack of experience in healthcare settings which can impact treatment adherence (Hughes et al., 2019). Interactions with renal nurses are important, especially for those undergoing HD in medical units, as they frequently engage with nurses to receive treatment (Anderson et al., 2008). While on HD, renal nurses provided Kelli with support and social networks, helping her through stressful dialysis and personal experiences. Healthcare workers can be a strengthening factor in patients’ journeys by engaging in a culturally safe and supportive manner (Kelly et al., 2022). While not all interactions with health staff were positive, supportive healthcare interactions made a significant impact on Kelli’s health journey. Having a nephrologist who was also a woman of colour was specifically an important healthcare interaction. It is important for healthcare staff to come from multicultural backgrounds to have personal understanding of the cultures and experiences of the people they support. There is a particular need for First Nations healthcare workers who understand the perceptions and experiences of First Nations patients (Kelly et al., 2022).

Dialysis experiences

Dialysis places a significant burden on the lives of those requiring it, their families and communities (Anderson, Cunningham et al., 2012). Many First Nations People “crash start” dialysis, requiring immediate and unplanned treatment which is both emotionally and physically shocking, and significantly disruptive to their lives (Mathew et al., 2018). HD is the most commonly used form of dialysis for First Nations People, requiring individuals to attend multiple sessions a week for several hours. This ties individuals to a machine, takes over their life, limits their capacity to work, is physically and emotionally tiring, and requires frequent travel to units to receive treatment (Schwartzkopff et al., 2020). This is especially a barrier to individuals who live in rural or remote locations requiring relocation or travel over long distances (Conway et al., 2018). PD can, contrastingly, be managed from home; however, this requires knowledge and can be a burden of care upon CKD patients and families (Mathew et al., 2018).

Kelli used both PD and HD treatments during her CKD journey. She initially started PD but faced complications due to limited training and education. Kelli then started HD, but did not have a chair on country and was required to travel to receive treatment, leaving work and removing her children from school. This was incredibly invasive to her and her family’s lives, highlighting the negative impact treatment can have on social and emotional wellbeing. Using social connections, Kelli was, however, able to advocate for herself and receive access to a chair on country. Advocacy, social networks, and having a determined mindset have also been identified as strengthening factors for other First Nations People (Goin & Mill, 2013).

However, many First Nations People do not have appropriate networks or knowledge of available options to advocate for themselves during their CKD journeys. This is compounded by cultural and language barriers and, in many instances, not being provided with the relevant health literacy of colonised systems (Schwartzkopff et al., 2020). This gap can be addressed by increasing peer support and patient navigators roles, so that those with lived experiences and relevant knowledge can advocate for and help First Nations People navigate colonial health systems (Kelly et al., 2022).

Kidney transplantation and the healing process

First Nations People are less likely to be on the kidney transplantation waitlist and receive a kidney transplant than non-First Nations Australians (AIHW, 2020). Like many other First Nations People, Kelli found the transplantation waitlist process unclear and confusing, needing to meet many barriers and health requirements for eligibility (Devitt et al., 2017; Kelly et al, 2022). Kelli was able to use her strengths to overcome this confusing space, and successfully received a kidney transplant. Transplantation and healing were difficult for Kelli, as she struggled with her body healing while trying to simultaneously understand and balance new medications. She identified that she would have been better supported through the process had information about medications been provided beforehand to ensure she properly understood and was prepared.

Other First Nations transplant recipients have similarly reported that this lack of information and conflicting priorities can prevent medication adherence and perceived compliance by healthcare staff (Devitt et al., 2017; Majoni & Abeyaratne, 2013). This is significant as it not only affects post-transplantation outcomes, but patients’ eligibility to receive a transplant (Anderson, Devitt et al., 2012). It is therefore important for more appropriate education and support to be provided to patients pre-transplantation so that they are eligible to receive a transplant, and that they and their families are prepared for the transplantation process. This can be supported by kidney disease education in community, peer education, and sharing of knowledge amongst people with similar experiences.

Kelli was able to be resilient and heal after receiving her kidney transplant, supported by her family, friends and community, and by engaging her cultural and spiritual connections. Families, support networks, culture and community are commonly reported strengths for First Nations People (Eades, 2017). However, as many First Nations People with CKD are required to leave country for treatments (Conway et al., 2018), they are removed from these factors that can support their healing. Healthcare services need to acknowledge the importance of these strengths for First Nations People and support patients maintaining these connections pre and post-transplantation in order to strengthen social and emotional wellbeing and physical health outcomes.

Post-transplant experiences

Health journeys do not finish with transplantation. Individuals are required to continue balancing medications and maintain health, facing the ongoing potential of losing their kidney and requiring dialysis again. Medications also have ongoing effects on the body which must be monitored and assessed regularly (Low, Crawford, & Maniass, 2018). First Nations People have poorer post-transplantation outcomes than non-First Nations transplant recipients, with lower patient survival, graft survival and delayed graft function. The reason for these poorer post-transplantation outcomes is likely complex and due to multiple factors, including poorer healthcare interactions, comorbidities, longer times on transplant waitlists and social determinants (McGuire et al., 2019).

Despite these ongoing health considerations, transplantation gave Kelli greater access to life. A kidney transplant enabled her to travel, pursue further education, share her experiences and knowledge with others, and use her CKD experiences to advocate for equitable outcomes for others. This is important as limited literature discusses First Nations People’s experiences post-transplantation.

Healthcare workers also have less interactions with individuals post-transplant. When supported and understood, First Nations People can lead, and take control of, their own CKD journeys, and use their experiences to support and educate others. Health journeys are ongoing throughout people’s lives and continue post-transplantation, thus social and emotional wellbeing should be supported to maintain strength and continuous positive health outcomes (Kelly et al., 2022).

Journey outside of CKD

Kelli lived many significant experiences relating to her family, consistent grief and loss, study and work commitments outside of her CKD journey. She discussed that CKD was often not a focus or priority to her, as there were other more important issues impacting her life. This is important for healthcare workers to understand as they may fail to recognise the complexities of patients’ lives when their predominant focus is on the patient’s healthcare. Outside events and patient priorities may explain distractions, failure to attend appointments, perceived non-adherence to treatment, or preferences in care. Talking with patients and families to better understand their priorities and past experiences can ensure the healthcare provided is appropriate and person-centred.

Like many other First Nations People in Australia with chronic diseases, Kelli used her family as a strength, focusing on them to overcome and remain resilient (Eades, 2017; Rix et al., 2014). She was not alone in her experiences, and her experiences impacted her family, friends and wider community. This can remind healthcare staff that First Nations patients are not alone, but are part of a broader relational network of people, providing a great source of strength during health journeys. Healthcare staff should also be aware that family and other life events may be a personal priority over healthcare, which needs to be considered when providing care (Kelly et al,. 2022).

Strengths, limitations and considerations

By collaboratively planning, conducting and analysing research with Kelli, her kidney health journey was mapped with a deep and reflective approach. This method enabled her to share her experiences in a strengths-based and culturally safe manner, with autonomy, control and governance over how information was shared, what information was shared, and what happened to it. This research approach would not have been achievable without the pre-established and long-term relations built on trust and respect between the ARG members and research team. In addition, two experienced academic supervisors carefully ensured academic rigour was maintained throughout.

Limitations and considerations of this research project involved: time restrictions; research, including sensitive and private data being conducted by a student with limited prior research experience; unexpected life events of potential participants and Kelli; balancing the requirements of the research project, the expectations of the ARG and the priorities of different team members; and upholding a decolonising methodology. These areas were addressed by team members collaboratively working together, engaging in ongoing reflections about processes and ways of working together, and holding each other accountable to ensure methods, findings and recommendations were appropriate. The publication was compared with: the nine principles outlined in the Australian Aboriginal Health Research Accord Table 7, and how they were upheld in this research (SAHMRI, 2014); the CREATE Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool (Harfield et al., 2020); and the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) qualitative research checklist (n.d.). (Appendices 1–3).

It was a collaborative decision to position Kelli Owen as the sole participant whose journey was mapped in depth. This framed the research as a case study, providing recommendations on how healthcare staff and services can best apply a strengths-based and person-centred approach to support First Nations People’s social and emotional wellbeing (Kushniruk et al., 2020). While having one participant meant this research did not meet typical colonial qualitative standards of data saturation, it instead follows a decolonising, person-centred and PAR approach, aiming to describe, understand, reflect upon and take action on the individual experiences of a First Nations woman (Bateman et al., 2022; Braun & Clarke, 2019).

Kelli chose to be identified as a co-author in both the honours thesis and this publication to support her ownership of data and to strengthen findings by linking them to herself as a person with lived experience. Identification of Kelli as co-author and co-researcher of this publication promotes First Nations Peoples’ authorship, leadership and methodologies, upholding First Nations Peoples’ sovereignty in publications (Hughes et al., 2022). Decolonising research acknowledges First Nations Peoples’ perceptions of knowledge being relationally or collectively owned rather than the property of an individual researcher. It is therefore important to transparently acknowledge participants’ involvement and continued ownership of their knowledge (Bourke, 2021). The team carefully considered the information included in this article to minimise potential repercussions for Kelli personally, and respected how Kelli preferred that her intellectual property would be shared (Harfield et al. 2020). As Kelli is a co-researcher and co-author, had previously shared her journey publicly at conferences, has supportive and positive relationships with healthcare staff and the research team, and holds multiple senior leadership roles on research projects and health initiatives in First Nations kidney health, it was collectively decided that identification and recognition of Kelli, her experiences and knowledge would be a strength-based and respectful approach. Kelli is emerging as a renal healthcare community leader, champion, research lead and Indigenous academic who is leading change in healthcare and research.

Further research and practice

This research supports and informs ongoing efforts to decolonise research and healthcare practice by applying a person-centred and strengths-based approach. Taking time to listen and reflect upon the experiences of First Nations People, include First Nations People meaningfully in all stages, including writing up and publishing, and explore the benefits of journey mapping as an approach to explore and share the experiences and recommendations from First Nations People are all important elements of academic research.

Conclusion

By mapping Kelli’s CKD journey in depth as a case study, this research project achieved a person-centred, strengths-based and culturally respectful approach. Kelli’s Ngolun/connections, Kunulun/actions and Peranbun/mindset were identified as factors which strengthened her resilience and supported her growth, self-esteem and sovereignty as a First Nations woman in a space dictated and controlled primarily by non-First Nations health professionals. Through reflecting upon the health journeys of First Nations People from their perspective, healthcare services and staff can be informed of how best to support culturally safe care. Recommendations were identified to educate healthcare systems and staff in order to influence policy and best practice that strengthens the social and emotional wellbeing of sovereign mothers, fathers and families and to ensure renal healthcare plays its part to support the continuation of the oldest continuous culture(s) in the world, Australia’s First Nations People.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Author(s)

Alyssa Cormick

Research Assistant, The University of Adelaide, SA, Australia

Kelli Owen

Chief Investigator, The University of Adelaide, SA, Australia

Deborah Turnbull

Professor and Chair in Psychology, The University of Adelaide, SA, Australia

Janet Kelly

Associate Professor, The University of Adelaide, SA, Australia

Dr Kim O’Donnell

Research Fellow, The University of Adelaide, Flinders University, SA, Australia

Correspondence to Alyssa Cormick, The University of Adelaide Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences Ringgold Standard Institution – Nursing, 4 North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia

Email alyssa.cormick@adelaide.edu.au

References

Anderson, K., Cunningham, J., Devitt, J., Preece, C., & Cass., A. (2012). If you can’t comply with dialysis, how do you expect me to trust you with transplantation? Australian nephrologists’ views on indigenous Australians’ ‘non-compliance’ and their suitability for kidney transplantation. International Journal for Equity in Health, 11(21). doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-21

Anderson, K., Devitt, J., Cunningham, J., Preece, C., Jardine, M., & Cass, A. (2012). ‘Looking back to my family’: Indigenous Australian patients’ experiences of haemodialysis. BMC Nephrology, 13(114). doi:10.1186/1471-2369-13-114

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2020). Profiles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with kidney disease. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Bateman, S., Arnold-Chamney, M., Jesudason, S., Lester, R., McDonald, S., O’Donnell, K., Owen, K., Pearson, O., Sinclair, N., Stevenson, T., Williamson, I., & Kelly, J. (2022). Real ways of working together: Co-creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 46(5). doi:10.1111/1753-6405.13280

Bourke, S. (2021). Enacting an Indigenist anthropology: Diversity and decolonising the discipline. Teaching Anthropology, 10(1), 30–36. doi:10.22582/ta.v10i1.583

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage Publications.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Bryant, J., Bolt, R., Botfield, J. R., Martin, K., Doyle, M., Murphy, D., Graham, S., Newman, C. E., Treloar, C., Browne, A. J. & Aggleton, P. (2021). Beyond deficit: ‘Strengths-based approaches’ in Indigenous health research. Sociology of Health & Illness, 43(6), 1405–1421. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.13311

Conway, J., Lawn, S., Crail, S., & McDonald, S. (2018). Indigenous patient experiences of returning to country: A qualitative evaluation on the Country Health SA dialysis bus. BMC Health Services Research, 1010. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3849-4

Critical Appraisal Skills Program UK. (n.d.). CASP checklists. Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

Devitt, J., Anderson., K., Cunningham, J., Preece, C., Snelling, P., & Cass, A. (2017). Difficult conversations: Australian Indigenous patients’ views on kidney transplantation. BMC Nephrology, 18(310). doi:1186/s12882-017-0726-z

Dingwall, K. M., Nagal, T., Hughes, J. T., Kavanagh, D. J., Cass, A., Howard, K., Sweet, M., Brown, S., Sajiv, C., & Majoni, S. W. (2019). Wellbeing intervention for chronic kidney disease (WICKD): A randomised controlled trial study protocol. BMC Psychology, 7(1), 2. doi:10.1186/s40359-018-0264-x

Dudgeon, P., Bray, A., D’Costa, B., & Walker, R. (2020). Decolonising psychology: Validating social and emotional wellbeing. Australian Psychologist, 52(4), 316–325. doi:10.1111/ap.12294

Eades, A. (2017). Understanding how individual, family and societal influences impact on Indigenous women’s health and wellbeing [Doctoral Dissertation]. Retrieved from https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/17774

Fogarty, W., Lovell, M., Langenber, J., & Heron, M. J. (2018). Deficit discourse and strengths-based approaches: Changing the narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute.

Goin, L., & Mill, J. E. (2013). Resilience: A health promoting strategy for Aboriginal women following family suicide. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, 11(3), 485–499.

Gregory, J. (2019). How did we survive and how do we remain resilient? Aboriginal women sharing their lived experiences and knowledge of lessons learned in life [Masters Thesis]. Retrieved from https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/120987/1/Gregory2019_MPhil.pdf

Harfield, S., Pearson, O., Morey, K., Kite, E., Canuto, K., Glover, K., Streak, J., Carter, D., Aromataris, E. & Braunack-Mayer, A. (2020). Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 1–9. doi:10.1186/s12874-020-00959-3

Hughes, J. T., Freeman N., Beaton, B., Puruntatemeri, A., Hausin, M., Tipiloura, G., Wood, P., Signal, S., Majoni, S. W., Cass, A., Maple Brown, L. J., & Kirkham, R. (2019). My experiences with kidney care: A qualitative study of adults in the Northern Territory of Australia living with chronic kidney disease, dialysis and transplantation. PLoS ONE, 14(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225722

Hughes, J. T., Kelly, J., Cormick, A., Coates, P. T., & O’Donnell, K. M. (2022). Resetting the relationship: Decolonizing peer review of First Nations’ kidney health research. Kidney International, 102(4), 683–686. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.08.011

Jones, B., Heslop, D., & Harrison, R. (2020). Seldom heard voices: A meta-narrative systematic review of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples healthcare experiences. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(222). doi:10.1007/s40615-018-0495-9

Kelly, J., Dent, P., Owen, K., Schwartzkopff, K., & O’Donnell, K. (2022). Cultural bias indigenous kidney care and kidney transplantation report. The Lowitja Institute. Retrieved from https://www.lowitja.org.au/content/Image/Cultural_Bias_Scoping_Review_Dec2020.pdf

Kilcullen, M., Swinbourne, A., & Cadet-James, Y. (2013). Chapter 3: Factors affecting resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander grandmothers raising their grandchildren. In B.F. McCoy, P. Stewart & N. Poroch (Eds.), Urban health: Strengthening our voice, culture and partnerships. Sydney: AIATSIS Research Publications.

Kushniruk, A. W., Borycki, E. M., & Parush, A. (2020). A case study of patient journey mapping to identify gaps in healthcare: Learning from experience with cancer diagnosis and treatment. Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal, 12(4), 405–418. doi:10.34105/j.kmel.2020.12.022

Leeson, S., Smith, C., & Rynne, J. (2016). Yarning and appreciative inquiry: The use of culturally appropriate and respectful research methods when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in Australian prisons. Methodological Innovations, 9. doi:10.1177/2059799116630660

Low, J. K., Crawford, K., & Maniass, A. (2018). Quantifying the medication burden of kidney transplant recipients in the first year post-transplantation. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 40, 1242–1249. doi:10.1007/s11096-018-0678-9

Majoni, S. W., & Abeyaratne, A. (2013). Renal transplantation in Indigenous Australians of the Northern Territory: Closing the gap. Internal Medicine Journal, 43(10). doi:10.1111/imj.12274

Mathew, A. T., Park, J., Sachdeva, M., Sood, M. M., & Yeates, K. (2018). Barriers to peritoneal dialysis in Aboriginal patients. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 5. doi:10.1177/2054358117747261

McGuire, C., Kannathasan, S., Lowe, M., Dow, T., & Bezuhly, M. (2019). Patient survival following renal transplantation in Indigenous populations: A systematic review. Clinical Transplantation, 34(1). doi:10.1111/ctr.13760

McMullen, S., Grootemaat, P., Winch, S., Senior, K., van den Dolder, P., Facci, F., & Clapham, K. (2015). Perspectives on chronic disease in the Australian Indigenous population: A review of. University of Wollongong, Centre for Health Service Development: Australian Health Services Research.

Morton, R. L., & Sellars, M. (2019). From patient-centered to person-centered care for kidney diseases. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 14(4), 623–625. doi:10.2215/CJN.10380818

Rix, E. F., Barclay, L., Stirling, J., Tong, A., & Wilson, S. (2014). ‘Beats the alternative but it messes up your life’: Aboriginal people’s experiences of haemodialysis in rural Australia. BMJ Open, 4(9). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005945

Schwartzkopff K. M., Kelly, J., & Potter, C. (2020). Review of kidney health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, 20(4). Retrieved from http://healthbulletin.org.au/articles/review-of-kidney-health-among-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people

South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI). (2014). Wardliparingga Aboriginal research in Aboriginal hands: South Australian Aboriginal Health Research Accord Companion Document. Retrieved from https://www.sahmriresearch.org/user_assets/2fb92e8c37ba5c16321e0f44ac799ed581adfa43/companion_document_accordfinal.pdf

The Lowitja Institute. (2022). Health journey mapping. Retrieved from https://www.lowitja.org.au/page/services/tools/health-journey-mapping

Appendices

Appendix 1

How this research project aligned with the nine principles outlined in the Australian Aboriginal Health Research Accord Table 7, and how they were upheld in this research (SAHMRI, 2014).

- PRIORITIES: Research should be conducted on priorities arising from and endorsed by the Aboriginal community to enhance acceptability, relevance and accountability. The AKction Reference Group (ARG), an Aboriginal Reference group, and the participant chose the research question and design. They collaborated with the researcher at all stages of research to ensure it followed their priorities and that it was relevant to them.

- INVOLVEMENT: The involvement of Aboriginal people and organisations is essential in developing, implementing and translating research. ARG members, the participant and Aboriginal mentors were involved in all stages of research. They had input into development, implementation, analysis and write up. They also provided constant feedback regarding research and the direction it was taking to.

- PARTNERSHIP: Research should be based on the establishment of mutual trust and equivalent partnerships, and the ability to work competently across cultures. The participant was positioned as a co-researcher to reposition her to be working alongside the researcher. The participant and researcher had an ongoing relationship throughout the research project. This relationship was built on pre-established trust and respect from the AKction project, enabling open communication and collaboration to occur.

- RESPECT: Researchers must demonstrate respect for Aboriginal knowledge, Aboriginal knowledge systems and custodianship of that knowledge. The researcher demonstrated respect for Aboriginal knowledge and customs, prioritising Aboriginal knowledge and ways of doing research. The participant and ARG’s preferences were respected and upheld throughout the research project, with their voices recognised as important and directing research.

- COMMUNICATION: Communication must be culturally and community relevant and involve a willingness to listen and learn. Open two way communication occurred between Kelli (coresearcher/particpant) Alyssa (coresearcher/student) the supervisors (Janet and Deborah), ARG members, and other AKction researchers involved in the project.

- RECIPROCITY: Research should deliver tangible benefits to Aboriginal communities. These benefits should be determined by Aboriginal people themselves and consider outcomes and processes during, and as a result of, the research. The research directly related to issues that were of importance to the participant, as she and other ARG members determined the research question. The participant was positioned as a co-researcher and co-author, with ownership and acknowledgment of her knowledge and data. The participant was provided an avenue to share her lived experience and provide recommendations to healthcare for improvements. She also reported that involvement itself was beneficial, as it was therapeutic and provided her the ability to be heard.

- OWNERSHIP: Researchers should acknowledge, respect and protect Aboriginal intellectual property rights and transparent negotiation of intellectual property use and benefit sharing should be ensured. It is acknowledged that the participant has ownership of the knowledge and intellectual property which she has shared for this research project. There has been negotiation with her regarding what information will be shared publicly. She has also chosen to be identified to further acknowledge her ownership of the information included in this research and how it is tied to her journey and experiences.

- CONTROL: Researchers must ensure the respectful and culturally appropriate management of all biological and non-biological research materials. The participant had control over information she shared during the yarning (data collection) process, and what happened to it. She had control over what information would be made public and what would remain private. The participant provided feedback throughout the research process to ensure direction of research was respectful and culturally appropriate.

- KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION: Sharing and translation of knowledge generated through research must be integrated into all elements of the research process to maximise impact on policy and practice. First Nations People knowledge and ways of doing were prioritised throughout research. Aboriginal mentors, the ARG members, and the participant were consulted throughout the research process.

Appendix 2

How this research project responded to the CREATE Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool (Harfield et al., 2020).

- Did the research respond to a need or priority determined by the community?

Yes, research question and direction were set by the AKction reference group (ARG). - Was community consultation and engagement appropriately inclusive?

Yes, included all members of the ARG. - Did the research have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research leadership?

Yes, research was co-designed and co-conducted with members of the ARG and the First Nations participant. - Did the research have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance?

Yes, First Nations members of the ARG and the research participant held roles in directing research question, design, and how the data were shared. - Were local community protocols respected and followed?

Yes, Kaurna community members apart of the ARG were involved in planning of the project to ensure community protocols were respected and followed. - Did the researchers negotiate agreements in regards to rights of access to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People’s existing intellectual and cultural property?

Yes, researchers negotiated with First Nations People’s right of access to existing intellectual and cultural property, respecting and upholding First Nations People’s governance. - Did the researchers negotiate agreements to protect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People’s ownership of intellectual and cultural property created though the research?

Yes, researchers identified that information included was owned by the participant and negotiated with her how her intellectual property would be shared, e.g. being identified in publications. - Did Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities have control over the collection and management of research materials?

Yes, the participant had control over collection and management of research materials positioned as a co-researcher and co-author. - Was the research guided by an Indigenous research paradigm?

Yes, research followed a decolonising approach, aiming to priories the knowledge and experience of First Nations People. - Does the research take a strengths-based approach, acknowledging and moving beyond practices that have harmed Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples in the past?

Yes, the research applies a strengths-based approach, focusing on the strengths and resilience of the participant, moving away from a deficit approach. - Did the researchers plan and translate the findings into sustainable changes in policy and/or practice?

Yes, the research translates findings into recommendations for healthcare staff and services linking many recommendations to the cultural bias report (Kelly et al., 2022). - Did the research benefit the participants and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities?

Yes, the participant identified that involvement was strengthening, re-empowering and therapeutic for her, enabling her voice and experiences to be heard. The participant was also benefited by being involved in research, as she is an emerging renal healthcare community leader, champion, research lead and Indigenous academic, whose position would be strengthened by having her journey shared in an academic publication. - Did the research demonstrate capacity strengthening for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals?

Yes. The research demonstrated capacity strengthening for the First Nations participant, as she was provided the opportunity to be involved in an Honours level research project, and authoring peer review articles. - Did everyone involved in the research have opportunities to learn from each other?

Yes. All members of the research team had opportunities to learn from each other, engaging in ongoing reflection and discussions.

Appendix 3

Appraising this research to the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) qualitative research checklist (n.d.):

- Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

Yes, line 87–89. - Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

Yes, research seeks to explore experiences of research participant. - Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

Yes, the research design followed a decolonising and participatory action research approach, with the process co-designed with the participant and members of the AKction reference group (ARG) to ensure it supported First Nations governance and priorities. - Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

Yes, recruitment involved working with a pre-existing reference group of First Nations People with lived experience of kidney disease, and negotiating with female members who were available and interested in participation. It provided discussion as to why some potential members were not included, and why the decision was made to conduct a case study on one participant. - Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

Yes, clearly identified data collection process (yarning with the patient in depth) was guided by the strategic health journey mapping tool. Data collected in this manner follows a decolonising and participatory action research approach, enabling the participant to collaboratively share in depth her experiences, applying a person-centred, whole of life, and strengths-based approach. - Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

Yes, the researcher and participant had a pre-existing relationship, having met on multiple occasions and acting as co-researchers and co-authors. This relationship and potential bias were addressed by engaging in ongoing reflection and adaptation of research processes to ensure data analysis and interpretation were appropriate and accurately reflected the participant’s lived experiences. - Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

Yes, ethical issues were considered. The project had ethics approval from the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee, the University of Adelaide and the Central Adelaide Local Health Network. The research team also engaged in ongoing reflections to ensure research was culturally safe and appropriate for First Nations participants (see review to Nine Principles Outlined in the Australian Aboriginal Health Accord and the CREATE tool). Research had ethics approval and engaged in ongoing reflections regarding the naming of the participant. - Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

Yes. Thematic analysis was used; this described how themes were derived and was reviewed with multiple members of the research team; 7 hours of data were obtained. Data (quotes) were presented to support findings, were agreed upon by participant and were reviewed with the participant to ensure they supported her lived experience. The researcher critically examined their role, providing a reflective statement, and identifying how all members of the research team engaged in ongoing reflections to ensure data and findings were appropriate and trustworthy. - Is there a clear statement of findings?

Yes, there is a clear statement of the findings. The researcher has discussed findings to other strengths and experiences of First Nations People in the literature. The credibility of findings is supported by the researcher reviewing the results with the participant to ensure they reflected their lived experience. - How valuable is the research?

This research is valuable, addressing significant gaps in the literature. The research addresses gaps in First Nations authorship, collaborative decolonising methodologies, and journeys of First Nations People with kidney disease presented from their perspective. The researchers have identified recommendations from the findings to support culturally safe, person-centred and strengths-based kidney care for First Nations People. The research supports future decolonising research and healthcare practice for and with First Nations People.