Volume 1 Issue 2

The stuck catheter: a hazardous twist to the meaning of permanent catheters

Venkat Sainaresh Vellanki, Diane Watson, Dheeraj K. Rajan, Cynthia B. Bhola, Charmaine E. Lok

Abstract

Introduction: Permanent central venous catheter use is associated with significant complications that often require their timely removal. An uncommon complication is resistant removal of the catheter due to adherence of the catheter to the vessel wall. This occasionally mandates invasive interventions for removal. The aim of this study is to describe the occurrence of this “stuck catheter” phenomenon and its consequences.

Methods: A retrospective review of all the removed tunneled hemodialysis catheters from July 2005 to December 2014 at a single academic-based hemodialysis center to determine the incidence of stuck catheters. Data were retrieved from a prospectively maintained computerized vascular access database and verified manually against patient charts.

Results: In our retrospective review of tunneled hemodialysis catheters spanning close to a decade, we found that 19 (0.92%) of catheters were retained, requiring endovascular intervention or open sternotomy. Of these, three could not be removed, with one patient succumbing to catheter-related infection. Longer catheter vintage appeared to be associated with ‘stuck catheter’.

Conclusions: Retention of tunneled central venous catheters is a rare but important complication of prolonged tunneled catheter use that nephrologists should be aware of. Endoluminal balloon dilatation procedures are the initial approach, but surgical intervention may be necessary.

Keywords: Embedded, Hemodialysis, Retention, Tunneled catheters

Reprinted from J Vasc Access 2015; 16 (4): 289-293 with permission of the Publisher.

INTRODUCTION

Ensuring an adequately functioning vascular access is one of the important challenges of routine nephrology practice. There has been a positive increase in dialysis prevalence over the last few decades, and with it, there has been a concomitant rise in the use of tunneled catheters for vascular access. Few of the well established reasons for converting to tunneled catheters are an increasingly older population with diabetic kidney disease with concomitant conditions that prohibit new or continued arteriovenous (AV)-access use such as peripheral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, AV-access aneurysms, vascular steal phenomenon, unfavorable anatomy, and simply exhaustion of available vascular access sites. Some patients prefer -tunneled catheters as a long-term alternative to a definite AV access due to their ease of use and convenience (1). However, along with this greater dependence on tunneled catheters is the increased risk of complications and the need for catheter removal.

Removal of tunneled catheters for various indications such as catheter malfunction, catheter sepsis, central venous stenosis, successful kidney transplantation, or successful maturation of an AV fistula or AV-graft is considered a routine procedure wherein, ideally, the catheter slides out smoothly from the subcutaneous tunnel on gentle traction once the fibrous sheath is dissected out from the surrounding cuff. However, rarely catheters become resistant to removal as a result of getting tethered to the vessel wall (2). In such cases, one has to often resort to direct exploration or endoluminal procedures by interventional radiology (IR) and even, at times, open surgical measures as thoracotomy to facilitate extraction of the catheter; such maneuvers can be associated with significant morbidity (2, 3). These catheters are popular by the name of ‘permcath’; however, along with the other well known complications of hemodialysis catheters (4, 5), the increasingly recognized complications of catheter adhesion and subsequent retention should give a pause to such notion. We aimed to describe the occurrence of this ‘stuck catheter’ phenomenon and its consequences.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective review of all the removed tunneled hemodialysis catheters from July 2005 to December 2014 at a single academic-based hemodialysis center to determine the incidence of stuck catheters. We also documented each patient’s clinical demographics and comorbidity profile, the need for surgical or radiological intervention, the specific type of intervention needed to remove the stuck catheters and the subsequent patient follow-up and outcome. Data were retrieved from a prospectively maintained computerized vascular access database and verified manually against patient charts.

RESULTS

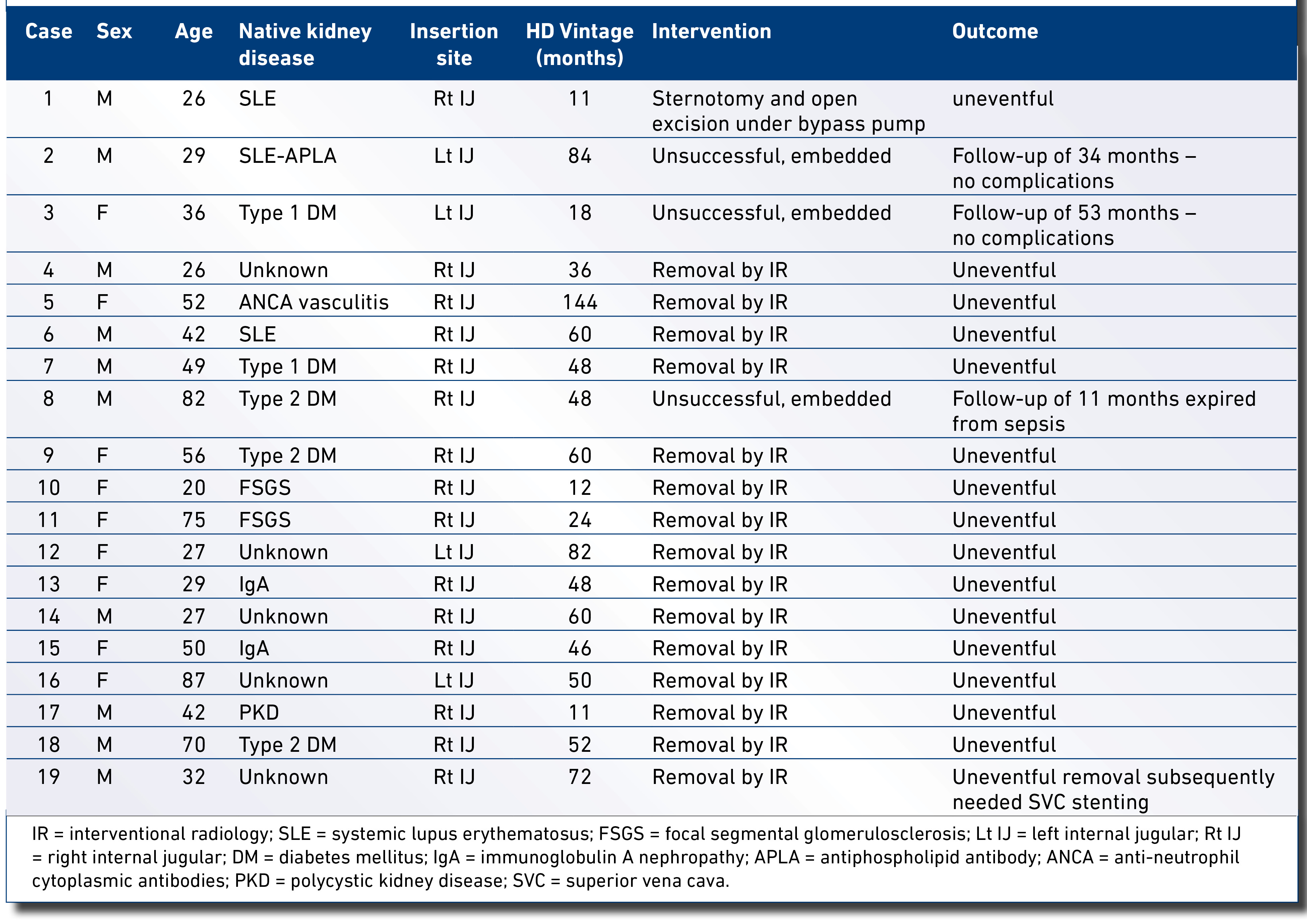

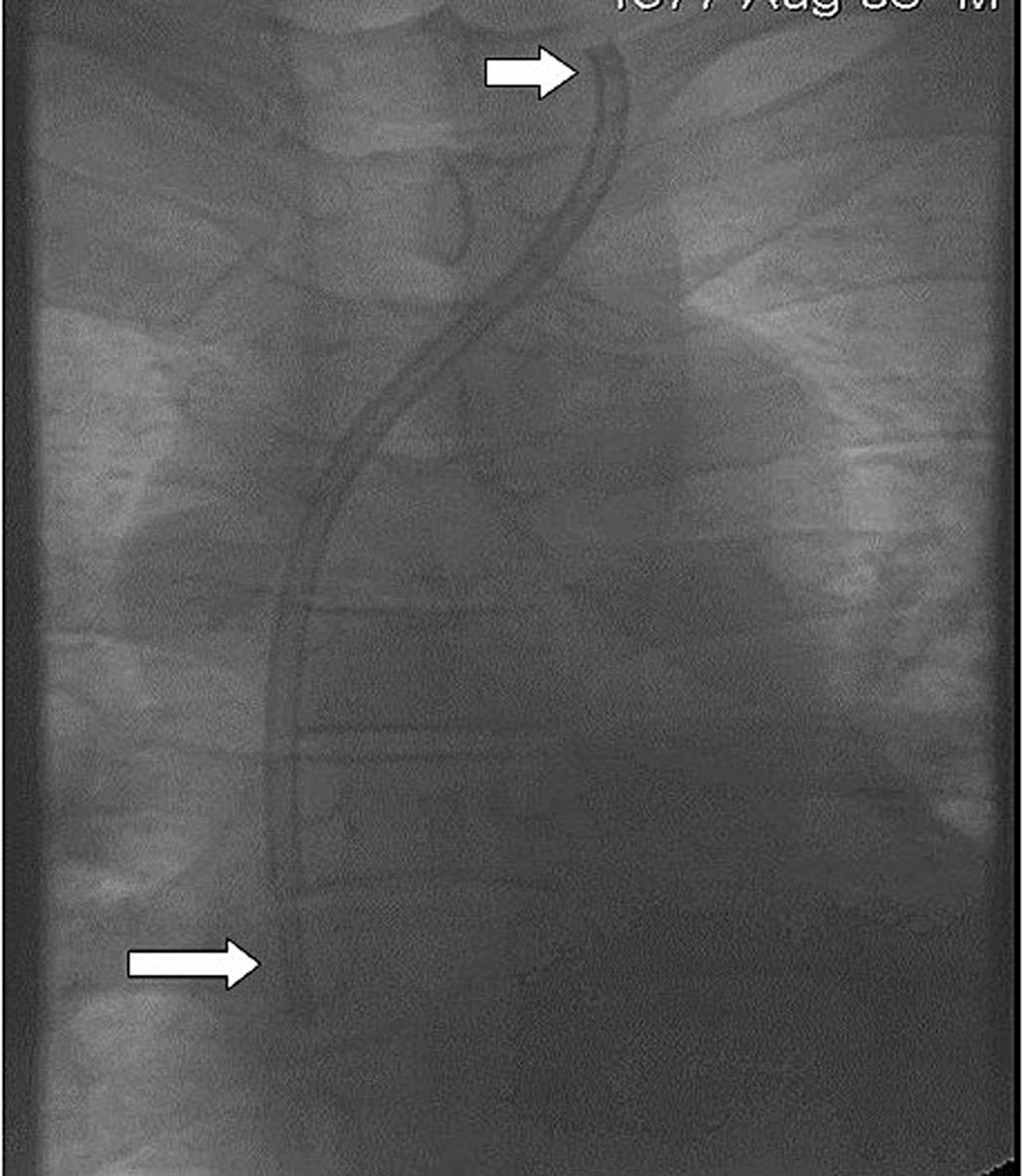

During the study period, there were 2048 catheters removed in 1061 patients. There were 19 cases (0.92%) of stuck catheters needing IR or surgical intervention for removal (Tab. I). These stuck catheters occurred in 10 men and nine women and appeared to be representative of the hemodialysis population. Of interest, three patients (15.7%) had significant secondary hyperparathyroidism and underwent surgical parathyroidectomy. In terms of catheter characteristics, the majority (79%) were in the right internal jugular vein and the mean catheter duration was 50.8 months (range 11-144 months). Three catheters could not be removed from the vessel and were embedded by IR. The procedure involved a surgical incision at the base of the neck and the catheter was dissected free from the surrounding tissue. A visual inspection and firm traction was done to confirm incorporation of the catheter into the vein. Subsequently, the catheter was transfixed and tied with 2-0 prolene suture and then cut; this lead to retraction of the catheter into deeper planes and closure was obtained at the base of the neck using 3-0 vicryl (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Patients and reatained catheters profile

Fig. 1 - Embedded catheter into mediastinal fascial planes. The small upper arrow shows the proximal ligated and divided part of the catheter, while the bigger arrow shows the right atrial part of the catheter under fluoroscopy.

Two of the three cases with embedded catheters had 34 and 53 months of uneventful follow-up, while the third case succumbed to sepsis after 11 months. The rest of the catheters were removed by IR under local anesthesia and mild sedation. Subsequently, either more aggressive dissection at the catheter exit site was performed or an incision was made in the area of the neck corresponding to the catheter entry into the internal jugular vein and gentle fine dissection was performed in and around the catheter. The extent of dissection was determined on a case-by-case basis to release the pericatheter fibrinous tissue.

If more aggressive traction was required beyond further dissection, 0.035 inch stiff glidewires were advanced down both lumens of the catheter into the IVC with traction then applied while observing for catheter/mediastinal movement under fluoroscopy. If the patient experienced chest discomfort or obvious shifting of the heart under fluoroscopy, the procedure was abandoned.

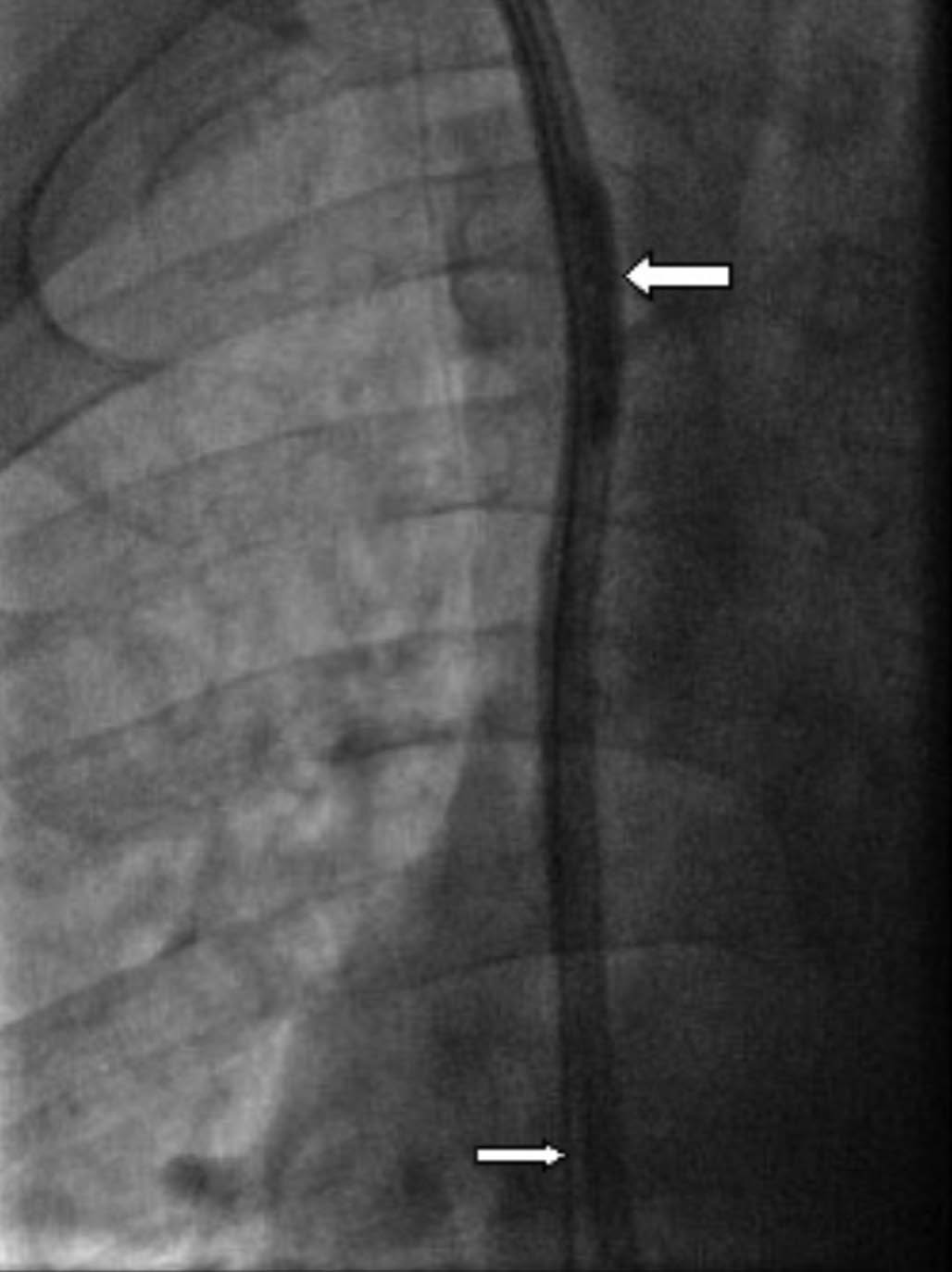

More recently in 2014, when conservative attempts fail, we have now advanced a 0.014 inch wire down a single lumen of the catheter and sequentially dilated the lumen of the catheter with a 4-5 mm Sterling angioplasty balloon (n = 2; Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts, USA). The course of the catheter from the tip to the cuff is dilated to an inflation pressure of 12-14 atmospheres for disruption of the pericatheter adhesions intravascularly and within the subcutaneous tissues of the extravascular tract prior to removal of the catheter (Fig. 2). The procedure was well tolerated and uneventful. In one patient, the stuck catheter required surgical sternotomy for extraction due to a coexistent pericatheter thrombus that was adherent to the right atrial wall; this was confirmed by transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) and contrast cardiac CT scan.

Fig. 2 - Endoluminal balloon dilatation of the stuck catheter. The bigger arrow points to the endoluminal balloon dilating the catheter, while the small arrow points to the glidewire advanced to the inferior vena cava.

The reasons for catheter removal were as follows: successful kidney transplantation and no longer needed the catheter in thirteen cases, catheter dysfunction in five cases, and catheter tip thrombus attached to the right atrium in the one case needing sternotomy.

DISCUSSION

Tunneled hemodialysis catheters may appear to be advantageous to patients, hemodialysis nursing staff and technicians by its universal availability and its rapid, pain free and easy connection to the dialysis circuit. However, there are serious tradeoffs that are now well recognized, such as catheter-related bacteremia and its complications (e.g. endocarditis), catheter dysfunction from intra and extraluminal thrombosis, mechanical issues such as kinking, accidental bleeding, catheter central venous stenosis, and even air embolism (5, 6). Recently, a new catheter complication, the “stuck catheter”, is being increasingly recognized with its often serious consequences, such as associated bacteremia, loss of functioning vascular access, and complications from hemorrhage during extraction (7). In our series, we report that almost 1% of all catheters inserted, become “stuck”. To put this into perspective, in 2013, there were approximately 100,000 incident hemodialysis patients the United States, with 82% initiating dialysis with a catheter (8, 9). If 1% of 82,000 patients had a retained catheter, the problem with “stuck catheters” could potentially affect as many as 800 U.S. hemodialysis patients. Fortunately, the majority of these incident catheters are removed in a timely manner so that a stuck catheter is avoided; however, the stuck catheter problem highlights the importance of making a point of doing so when so many patients use a catheter.

The antecedent causes for the stuck catheter are not well established; however, animal and human autopsy studies (10-12) suggest that the reactionary changes that occur in the vessel wall subsequent to the initial endothelial injury caused by the catheter insertion leads to formation of thrombus and a fibrous sleeve around the catheter. This later becomes organized into a pericatheter fibrinous sheath composed of stable collagen tissue and transformed proliferating smooth muscle cells covered by endothelium. Electron microscopic studies reveal pedicle-like attachments between the vein wall and the pericatheter sleeve, likely contributing to the adhesion of the catheter to the intima of the vessel wall and possibly the right atrium (10-12). Some of the other risk factors that have been implicated are the stimulus from the natural growth and expansion of the chest in children and adolescents, female sex, longer catheter vintage, left-sided catheter placement, intermittent catheter infections, ipsilateral AV fistula, prior ipsilateral catheterization, presence of stent or pacemaker leads, and calcified vessels (10, 12-15).

The current available literature seem to suggest a direct relation between the catheter vintage (range 12-120 months) and female sex implicating a role of the narrow caliber of the blood vessels in the development of catheter retention (13, 14-17). However, these observations are limited to short case series comprising three to six cases. There are cases of retained nondialysis central catheters that have been reported earlier in the pediatric population. Catheter vintage, narrow caliber of the vessels, and the natural growth and expansion of the surrounding structures in this age group seem to predispose them to this complication (18). These retained catheters could be removed largely through a minimally invasive exploration by IR or through an extensive surgical approach. However, due to surgical limitations, several cases of stuck catheters had to be buried in the fascial planes after ligation and division of the catheter ports proximally. The follow-up of such buried catheters did not suggest any increased risk of thrombosis or embolism. Currently, there are no specific recommendations on prophylactic anticoagulation or antibiotic use for stuck catheters, although mortality from sepsis remains a cause of major concern (13, 14, 16, 17).

Recently, newer techniques have been described to retrieve the stuck catheters by radiological interventions employing endoluminal catheter-based balloon dilatation. In studies by Hong and Ryan, low-profile angioplasty balloons are inserted through the lumen of the catheter and then inflated. The catheter itself becomes dilated, potentially disrupting pericatheter adhesions, freeing up the catheter to allow for easy, uncomplicated removal, or exchange. This technique has had encouraging results and offers a simple, safe, and effective way to address the issue of the stuck catheter; this has become our method of choice if conservative attempts with greater traction and dissection fail (19).

Our staged approach for removing stuck catheters begins with nonimage-supported dissection at the exit site with moderate traction to the point where there is concern for catheter fracture. The next step is a cutdown on the catheter at the neck with freeing of tissue around the catheter at this level and traction on the catheter at this site until the point of concern for catheter fracture. If these methods fail, guidewires are advanced down both lumens to maintain access to the catheter and more aggressive traction is applied while observing for mediastinal shift on flourscopy. If the patient experiences moderate discomfort and/or pronounced mediastinal shift, the procedure is abandoned and the patient referred for surgical extraction. As we have begun intraluminal dilation, no extraction attempts requiring surgical extraction or catheter abandonment have been required. Although there are anecdotal reports of using loop snares from the groin to free up catheters or laser-facilitated extraction, we have not attempted these methods.

The current study is the largest to date of this rare complication. About 1% (0.92%) of the total catheters removed during the study period were complicated by retention. In our study, catheter vintage appeared to be an important factor (mean vintage 50.8 months). A significant number of young patients under 30 years old had this complication (n = 7). The reason for removal of the catheter in this group was successful kidney transplantation in all of them. An integrated multidisciplinary chronic kidney disease clinic with a dedicated vascular access team could be instrumental in minimizing complications (20, 21). Such a team approach would ensure timely chronic and endstage kidney disease education, modality selection, and vascular access planning to avoid catheter use and its associated risks, including that of a stuck -catheter. Indeed, although two of the three embedded catheters in our series continued to have an uneventful course with 34 and 54 months of follow-up, the third case succumbed to sepsis. None of the three embedded catheter cases were on prophylactic anticoagulants or antibiotics except for low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily) for cardiac reasons.

Our study highlights that catheters can be associated with serious consequences, even with rare complications such as the stuck catheter. Patients, particularly young dialysis patients, should avoid prolonged catheter use, to reduce their risks of complications, such as having a stuck catheter.

Although earlier case series seem to suggest the need for prophylactic catheter change, preferably by a separate exit site (14, 16), there is no consistent evidence supporting this course of action. Indeed, given the rare occurrence, it is challenging to develop evidence-based management strategies for the stuck catheter (e.g. anticoagulation, antibiotics use, and method of removal). Wherever possible, efforts should be directed to avoid use of catheters to minimize such complications.

CONCLUSION

Retention of tunneled central venous catheters is a rare yet important complication of hemodialysis. Nephrologists should be aware of this complication and its subsequent management. Endoluminal balloon dilatation procedures can be the initial approach to address the issue. In patients who fail less invasive endovascular procedures and are considered at high surgical risk, embedding the catheter after ligation and proximal division of the ports is an option with subsequent surveillance for and timely management of complications, such as sepsis.

DISCLOSURES

Financial support: The authors have no financial disclosures to make.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

Corresponding author:

Charmaine E. Lok, MD, FRCPC, MSc

200 Elizabeth Street

8N-844

Toronto

ON M5G 2C4, Canada

Author(s)

Venkat Sainaresh Vellanki1, Diane Watson1, Dheeraj K. Rajan2, Cynthia B. Bhola1, Charmaine E. Lok1,3 1 Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario - Canada 2 Division of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Department of Medical Imaging, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario - Canada 3 Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario - Canada

References

- Chaudhry M, Bhola C, Joarder M, et al. Seeing eye to eye: the key to reducing catheter use. J Vasc Access. 2011;12(2):120-126.

- Carrillo RG, Garisto JD, Salman L, Merrill D, Asif A. A novel technique for tethered dialysis catheter removal using the laser sheath. Semin Dial. 2009;22(6):688-691.

- Ryan SE, Hadziomerovic A, Aquino J, Cunningham I, O’Kelly K, Rasuli P. Endoluminal dilation technique to remove “stuck” tunneled hemodialysis catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;

23(8):1089-1093. - Jean G, Charra B, Chazot C, Vanel T, Terrat JC, Hurot JM. Long-term outcome of permanent hemodialysis catheters: a controlled study. Blood Purif. 2001;19(4):401-407.

- Rehman R, Schmidt RJ, Moss AH. Ethical and legal obligation to avoid long-term tunneled catheter access. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):456-460.

- Richard HMIII, Hastings GS, Boyd-Kranis RL, et al. A randomized, prospective evaluation of the Tesio, Ash split, and Opti-flow hemodialysis catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(4):

431-435. - Quaretti P, Galli F, Fiorina I, et al. A refinement of Hong’s technique for the removal of stuck dialysis catheters: an easy -solution to a complex problem. J Vasc Access. 2014;15(3):

183-188. - Lok CE, Foley R. Vascular access morbidity and mortality: trends of the last decade. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(7):1213-

1219. - USRDS. U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2013.

- Forauer AR, Theoharis C. Histologic changes in the human vein wall adjacent to indwelling central venous catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(9 Pt 1):1163-1168.

- Thein H, Ratanjee SK. Tethered hemodialysis catheter with retained portions in central vein and right atrium on attempted removal. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(3):e35-e39.

- Xiang DZ, Verbeken EK, Van Lommel AT, Stas M, De Wever I. Composition and formation of the sleeve enveloping a central venous catheter. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:260-271.

- Mortensen A, Afshari A, Henneberg SW, Hansen MA. Stuck long-term indwelling central venous catheters in adolescents: three cases and a short topical review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54(6):777-780.

- Hassan A, Khalifa M, Al-Akraa M, Lord R, Davenport A. Six cases of retained central venous haemodialysis access catheters. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(7):2005-2008.

- Forneris G, Savio D, Quaretti P, et al. Dealing with stuck hemodialysis catheter: state of the art and tips for the nephrologist. J Nephrol. 2014;27(6):619-625.

- Liu T, Hanna N, Summers D. Retained central venous haemodialysis access catheters. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(3):960-961, author reply 961.

- Field M, Pugh J, Asquith J, Davies S, Pherwani AD. A stuck hemodialysis central venous catheter. J Vasc Access. 2008;9(4):

301-303. - Jones SA, Giacomantonio M. A complication associated with central line removal in the pediatric population: retained fixed catheter fragments. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(4):594-596.

- Hong JH. A breakthrough technique for the removal of a hemodialysis catheter stuck in the central vein: endoluminal balloon dilatation of the stuck catheter. J Vasc Access. 2011;12(4):

381-384. - Goldstein M, Yassa T, Dacouris N, McFarlane P. Multidisciplinary predialysis care and morbidity and mortality of patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(4):706-714.

- Chen YR, Yang Y, Wang SC, et al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for chronic kidney disease in Taiwan: a 3-year prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(3):671-682.