Volume 39 Number 1

The importance of a holistic approach to stoma care: A case review

Melanie C Perez

Keywords Holistic approach, complex care needs, ileostomy, ileal conduit, enterocutaneous fistula.

For referencing Perez MC. The importance of a holistic approach to stoma care: A case review. WCET® Journal 2019; 39(1):23-32

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.1.23-32

Abstract

This case review discusses the importance of providing a holistic approach to the care of a patient with two stomas and an enterocutaneous fistula. In this case, the stomas and fistula significantly affected the patient; not just physically but emotionally and socially. The different challenges that arose in pouching a high-output ileostomy, enterocutaneous fistula and ileal conduit with Foley catheter in situ are explored. It also delves into the various options for discharging a patient with complex ostomy complications requiring different needs and resources. Finally, it aims to highlight the therapeutic comprehensive care the stomal therapy nurse provided to the patient and their family.

Introduction

In 2014, bladder cancer was the eleventh most diagnosed cancer in Australia1. There were 2094 males and 654 females with new cases of bladder cancer diagnosed1. Meanwhile, in the same year colorectal cancer was the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and there were 6886 females and 8368 males with new cases of colorectal cancer2. In the general population, it is still unknown whether there is an association between urologic cancer and colorectal cancer3. It is rare for patients to have synchronous carcinoma of the bladder and colorectum4. Urologic cancer patients with other primary malignancies may be on the rise due to increased exposure to numerous environmental causative agents, increased worldwide incidence of obesity and an ageing population4. This paper explores the case of a 63-year-old man diagnosed with bladder and bowel cancer and the complications he developed post-surgery.

Pre-operative counselling and stoma site marking are recommended to prepare patients for life with a stoma, to choose an optimal location, and to reduce potential surgical complications post-operatively and other future problems5. In the event of an emergency procedure, the patient’s stoma site is often not able to be marked and education about living with a stoma is not provided. Marking a patient for a stoma in an emergency may not always be possible and subsequently a stoma that is poorly positioned is likely to reduce the quality of life of the patient6. Factors that may influence where the surgeon might position the stoma during emergency surgery are: sepsis; oedema; inflammation of the bowel; nature of any underlying disease; an unstable and deteriorating patient; and time constraints. In addition, with patients in a supine position it is difficult to determine skin folds, assess body mass index and creation of the stoma is often delegated to a junior member of the surgical team. Common long-term complications associated with emergency ostomy surgery are skin problems, stenosis, prolapse, parastomal hernias, side fistulae and increased length of hospital stay7,8.

In addition to any stomas and their location, other sequelae of emergency ostomy surgery that may contribute to the patient’s ability to self-care and be discharged in a timely manner relate to a lack of pre-operative counselling, ability to see the stoma, management of the stoma and appliance and psychosocial issues7,9.

Case Review

Patient overview and presenting complaint

Mr TA is a 63-year-old gentleman who presented to the facility with rectal bleeding and haematuria, on a prior background of both colorectal and bladder cancer. His medical history includes hypertension and diabetes mellitus type 2. He underwent an emergency anterior resection requiring formation of end colostomy and cystectomy with formation of an ileal conduit.

Post-operative complications

Intra-abdominal sepsis

Post-operatively, Mr TA developed intra-abdominal sepsis, requiring three exploratory laparotomies for abdominal washouts. He subsequently developed ischaemia of his small and large bowel. The surgeon estimated less than 2 metres of small bowel remained and consequently an ileostomy was formed on the right side of the abdomen. The surgeon was not able to accurately measure the length of the small bowel due to the patient’s condition at the time of the operation.

Ileostomy location

The ileostomy was fashioned approximately 2 centimetres in distance from the ileal conduit at 12 o’clock position. The location of the ileostomy had a huge impact on the care of the stomas, pouching processes, and patient’s ability to self-care of his stomas.

Fistulae development

Mr TA developed a fistula from his ileal conduit that began leaking urine into his abdomen. To divert urine from the ileal conduit, bilateral nephrostomies were created. Unfortunately, an enterocutaneous fistula also erupted from his midline wound dehiscence that proceeded to discharge 3 to 6 litres of faecal output per day. Initially, the impression was the enterocutaneous faecal fistula would heal with time, but this did not occur. After approximately seven months, an attempt to endoscopically close the site of the fistula leakage was unsuccessful.

Cancer recurrence

A biopsy taken during the endoscopic procedure showed recurrent colonic disease. It was at this stage that a collective decision was made not to pursue any further surgical intervention. Due to the multiple laparotomies and ensuing complications, this patient’s journey has been full of challenges, both for the patient and the health care providers.

Challenges

The major challenges faced by Mr TA and staff were the proximity of the stomas, high faecal and fistula outputs, stomal complications and protection of the peristomal and peri-wound skin.

Ileostomy: In Mr TA’s case his ileostomy created dual challenges, which were a combination of the ileostomy spout being flush to the skin as well as the high output from the ileostomy.

Ileal conduit: Additionally, his ileal conduit was retracted, necessitating insertion of a Foley catheter to prevent stenosis.

Fistula: Mr TA’s mid-abdominal enterocutaneous fistula, which had three openings, was draining 3–6 litres of faecal fluid daily.

Stoma locations: All the stomas were near each other (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Ileostomy, urostomy, mid-abdominal fistula

Interventions: Stoma and fistula management strategies

Peristomal skin care

The peristomal skin was cleansed with warm water from the tap, dried with chux (a soft woven cloth) and CavilonTM No Sting Skin Barrier wipes were applied to the skin for protection. In some instances, Stomahesive® Protective Powder was used if the skin was eroded to provide further protection and encourage healing.

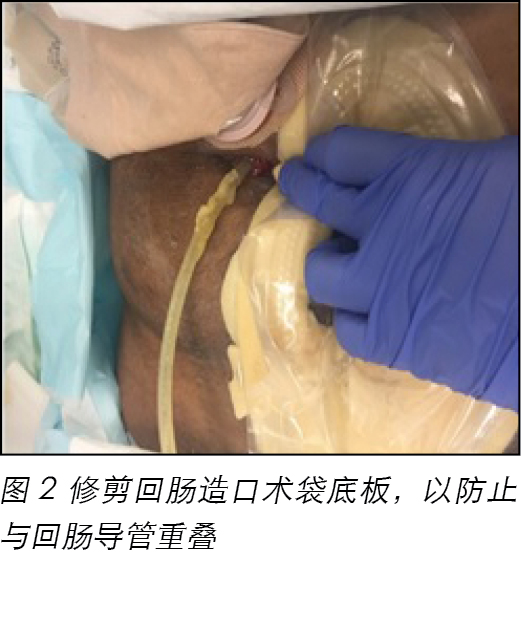

Pouching strategies

Measurements were obtained of the diameters of the stomas and enterocutaneous fistula to find the pouches that would best suit individual management of each of the stomas and fistula, which were in very close proximity to one another. A decision was made to pouch the ileal conduit, ileostomy and fistula separately to accurately measure the output of each stoma and the fistula and to enable a better seal to prevent peristomal skin complications. It was found that the base plates of all the pouches needed to be trimmed to keep them separate and facilitate adherence to the skin (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Base plate of ileostomy pouch trimmed to avoid overlapping with ileal conduit

The ileostomy was managed with a convex, high-output pouch that was connected to a long drainage bag to keep the bag empty. This was due to the significant amount of faecal output that was watery in consistency and classified as type 7 in accordance with the Bristol stool chart10. Attempts to regulate the faecal output with medications such as Loperamide, Lomotil, Codeine Phosphate and Octreotide subcutaneous injection all failed.

A 2-piece soft convex system was used to manage the ileal conduit in order to easily thread the Foley catheter through the base plate. And, further, the length of the high-output pouch accommodated the length of the Foley catheter when in situ.

The base of the wound pouch used to contain the fistula output was cut off-centre to keep the pouch separated from the other pouch as much as possible.

Other Challenges

Pain

One of the issues that coincided with changing all Mr TA’s pouches was pain. It was evident from Mr TA’s facial grimaces that changing his pouches caused him considerable pain. Mr TA, however, declined any analgesia most of the time, despite receiving frequent education on the importance and use of pain relief. Even though his facial grimaces indicated he was in pain, he always stated that after the procedure, the pain resolved; therefore, he thought there was no benefit in taking pain relief.

Due to the patient experiencing pain on pouch changes, minimising the frequency of routine pouch changes was an essential strategy for this patient. The pain experienced was mostly due to the pouch adhesives, the pressure applied to his abdomen to remove the pouches, when cleaning the skin and re-applying the pouches. The revised care plan to change the pouches twice a week only or when they leaked was well tolerated by the patient. The pouches were checked daily for intactness so that potential leaks were avoided. Additionally, the staff and the patient were encouraged to keep the pouches empty to reduce the weight, tension and drag on the adhesion between the pouches and his skin.

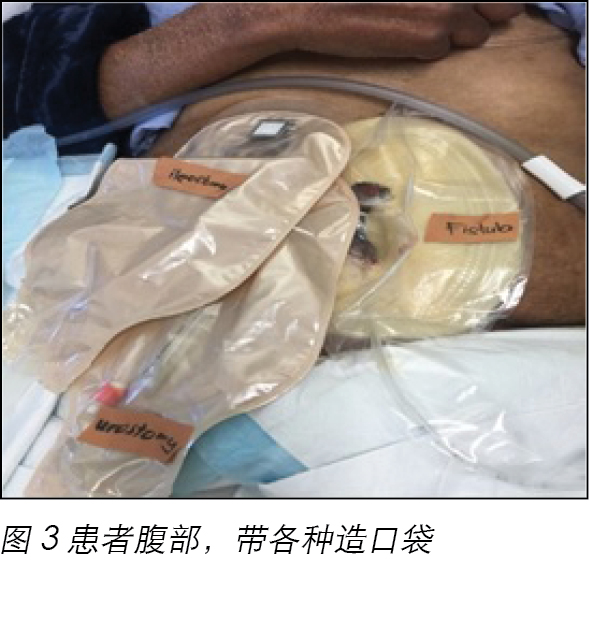

Body image and maintaining dignity

The normal anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal or urinary systems are changed following creation of an ostomy11. An abdominal opening is created, allowing for the bowel, bladder or ureters to be exteriorised where the intestinal fluid or urine are diverted, the outflow of which is collected by external pouches. This results in marked changes for the individual in relation to physical appearance and day-to-day functioning of a person11. In the case of Mr TA, the impact of these changes on his body image were exacerbated thrice by the presence of three different pouches covering most of his abdomen (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Patient’s abdomen with pouches in place

Additionally, the output from his enterocutaneous fistula was explosive, erupting like a fountain at two points and a blowhole on another. This both embarrassed and frustrated Mr TA, who was most apologetic whenever the fistula discharged in this manner while the pouches were being changed. No matter how many times he was reassured that this was not his fault and timing of the fistula discharging was beyond his control, he still felt helpless.

In this situation, it was important to make the mood lighter through light conversation to attempt to divert his attention from focussing on the presence and management of the fistula, which was found to be a useful strategy. This was a crucial factor in assisting Mr TA to maintain his dignity amidst the management of multiple stomas and the fistula.

Odour control

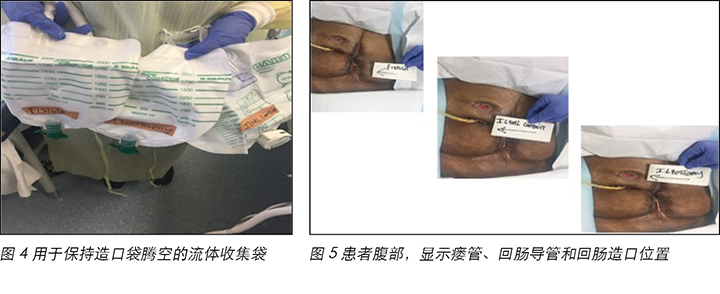

The characteristic odour in faeces has obvious implications for patients with a stoma, which causes considerable concern when either wearing or emptying the pouch12. The odour emanating from Mr TA’s pouches was difficult to minimise, despite using some drops of eucalyptus oil in the bag. This was attributed to the frequency of emptying the pouches due to the volume, thereby removing the efficacy of the eucalyptus oil that was dropped in the pouches. This led to feelings of shame for the patient and his family that was manifested by the amount of air freshener they used within the room. Changing the pouched two times a week was found to minimise the odour, so pouch changes were routinely set every Monday and Friday. The faecal pouches used by Mr TA had a charcoal filter to minimise the odour. In addition, long drainage bags were attached to all pouches to reduce the impact of odour (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4 (left) Flow collector used to keep the pouches empty. Figure 5 (right) Abdomen showing location of fistula, ileal conduit and ileostomy

Discharge planning and no discharge destination

Another issue that arose was discharge planning. It became apparent that due to the complexity of Mr TA’s care, such as the pouching changes, amount of ostomy and fistula output plus his requirements for intravenous fluids and palliative care needs, the options for a discharge destination were very limited. Returning home for Mr TA was not an option. There were not enough resources and services to cater to the patient’s needs in the community. It was found that around the area where Mr TA resides, most of the nursing homes did not have the resources to provide his daily intravenous fluid needs, and the community nurses could not undertake the changing of his pouches for an extended period.

An option to teach Mr TA and his wife to change his pouches was attempted. Three weeks were devoted to teaching Mr TA and his wife the pouching regime, but it was proven to be too difficult for his wife due to the technicalities of the pouching procedures and the unpredictability of when the stomas or fistula could potentially discharge. In addition, they needed suction equipment to assist with pouch changes. Further, if multiple instances of leakage occurred, they may have insufficient products to use in the home.

Nursing home options were explored three times, but after showing the nurse unit managers and more experienced staff the steps to change the pouches, they all concluded they would not be able to manage the pouching regimes within their facilities. Further, they did not have the resources and manpower to be able to handle the task. Mr TA would also need intravenous fluids to be able to replace ileostomy and fistula outputs. All efforts to support the nursing staff and nursing homes were provided through a step-by-step guide with photos on how to change the pouches. A PowerPoint presentation was also completed. The prospective facilities approached were reassured that ongoing stomal therapy support would be provided if the patient was accepted, but these strategies were to no avail.

The inability to find nursing home placement led to feelings of rejection from the patient and his family; therefore emotional support was provided by the stomal therapy nurse and social worker.

Discussion

Approximately one-fifth of all stomas are sited during emergency procedures8. The incidence of complications associated with ileal conduit is reported to range from 15% to 65% and one of the most commonly reported complications are stoma or abdominal wall-related changes that includes stoma stenosis and retraction13.

Management of any resultant post-operative complications, therefore, requires a holistic and inter-professional approach to patient care9. Ideally, ileostomy and ileal conduit stomas should protrude several centimetres from the abdominal wall. The rationale for an extended spout is due to the amount, consistency and constituents of the faecal and urinary outputs. Added to that are the challenges presented to contain and protect the skin with higher stomal outputs in the presence of flush or retracted stomas14.

The management interventions revolved around three goals: to maintain skin integrity, minimise unnecessary pain and contain the effluent. Ensuring there was a pouching plan that facilitated good adhesion of the pouches to the skin to maintain patency of the seals was one of the main goals in view of the complexity of Mr TA’s case. This would help to maintain his peristomal/fistula skin integrity. Ostomy effluent that is in contact with the skin is often the result of a less than optimal pouch fit15.

Promoting positive outcomes for patients with a stoma starts with an intact skin. This is the cornerstone of any stoma care and this was established. It is acknowledged that this was made possible by being able to access the necessary products to use, making the challenges physically achievable.

The hydrocolloid baseplates used to manage Mr TA’s stomas kept his skin integrity intact, which also assisted in preserving his dignity and body image. The pouching systems chosen were the two-piece, convex, high-output Dansac Gx plus pouches, the seals of which were maintained. The soft convexity of the base-plate mildly pushed the flush to skin ileostomy outward, preventing leaks, plus it provided a snug fit around the retracted ileal conduit. Using hydrocolloid baseplates with convexity to enhance security of pouch adhesion to protect the peristomal skin is considered best practice15.

Using the Gx plus provided a longer wear time, allowing the pouches to be changed only twice a week. Not only was this more efficient time-wise, it was more economical product wise and more importantly this prevented unnecessary pain for the patient. As the incidence and threat of stomal pouch leakage decreased, this reduced Mr TA’s anxiety and stress levels16.

The high ileostomy output was investigated, and the results were negative for any signs of infection. The quantity and content of the output, therefore, have been attributed by the treating surgical team to the small residual length and irritable nature of the bowel tissue, and his underlying malignancies. No diagnostic interventions were undertaken to identify any potential causes of intestinal insufficiency or intestinal failure. The pouching plan for the patient was effective for the whole year Mr TA was admitted and managed in our health service. The faecal ostomy/fistula output always fluctuated, despite all the medications and other interventions attempted to resolve the high output.

Apart from the physical challenges posed by management of the stomas and enterocutaneous fistula, there was Mr TA’s patient’s wellbeing to consider. Throughout all phases of his illness (pre-operatively, post-operatively and terminal care) he needed to know and feel he was supported mentally as well as physically. A higher level of psychological distress is recognised in stoma patients as they perceive a sense of loss of physical and emotional independence16.

Mr TA often refused any pain relief for the pain he experienced during pouch changes. The differences in perceptions of pain between genders, different cultural groups and those from diverse ethnic backgrounds and how they react to or tolerate pain are acknowledged, whereby some may appear to overreact and others to display relative tolerance or stoicsm17. Potentially, as Mr TA was from an ethnic background, a pastor, and being highly religious impacted his views on and use of analgesia17. Through education, counselling and care of the stomal therapy nurses the Mr TA’s anxiety was lessened16. Truly, there is an ongoing need for the patient to feel supported mentally and emotionally.

Most patients look to the health care provider for guidance on how to proceed and cope with their medical condition. A significant motivating and coping factor for patients is hope18, and this is what Mr TA held on to. To effectively cope and make decisions, hope is a critical aspect, which correlates with quality of life and living with a stoma7. Health care providers play a significant role in patients’ ability to cope and understand everything that is happening to them; hence, the importance of providing holistic care to patients and their family.

Additionally, the therapeutic relationship between the stomal therapy nurse and Mr TA was strengthened by the challenges that were overcome and the length of time he was cared for by the stomal therapy nurse. This provided Mr TA with some relief with regard to continuity of care and that no matter how difficult the pouching could be, the stomal therapy nurse would find a way to overcome these difficulties.

Creating a therapeutic relationship with Mr TA that was based on trust, mutual respect and a feeling of ease helped tremendously with managing this complex case. Establishing rapport early in the relationship assisted with his clinical and therapeutic management in the long term.

Promoting positive outcomes for patients with a stoma starts with an intact skin. This is the cornerstone of any stoma care and this was established. It is acknowledged that this was made possible by being able to access the necessary products to use, making the challenges physically achievable. The pouching plan for the patient has been effective for the whole year that the patient was admitted. The output has always fluctuated, despite all the medications and other interventions attempted for the care of this patient.

Mr TA was not able to be discharged home, nor was he placed in a nursing home; however, with the implementation of evidence-based ostomy and palliative care measures, towards the end of his life he remained comfortable.

Conclusion

The best outcomes gained from this case were the learning experiences that came from resolving the challenges faced. This has reinforced the value of developing early therapeutic relationships between the patient, his family, stomal therapy nurse and the medical team. This case has clearly shown that being able to access different products makes the stomal therapy nurses’ task manageable. And, more importantly, the need for continuous improvement and growth of the stomal therapy services as more complicated and complex cases arise.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The author received no funding for this study.

采取整体方式护理造口的重要性:病例回顾

Melanie C Perez

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.1.23-32

摘要

此病例回顾讨论在护理一位有两个造口和一个肠道皮肤瘘管的患者时采取整体方式的重要性。在此病例中,造口和瘘管严重影响患者,不只在身体方面,也包括情感和社交方面。本文将探讨在为高排出量回肠造口术、肠道皮肤瘘管和采用原位Foley导管的回肠导管更换造口袋时遇到的各种挑战。本文还将寻求各种选择,以便让有复杂造口术并发症、需要不同需求和资源的患者顺利出院。最后,本文的目的是强调造口治疗护士对患者及其家人提供全面治疗性护理的重要性。

前言

2014年,膀胱癌在澳大利亚的最常见癌症中排第11位1。有2094位男性和654位女性被诊断患有新发膀胱癌1。与此同时,2014年结直肠癌是第三常见癌症,有6886位女性和8368位男性被诊断患有新发结直肠癌2。在一般人群中,尚不清楚泌尿道癌症与结直肠癌是否存在关联3。患者同时患膀胱癌和结直肠癌的情况非常罕见4。由于暴露于多种环境致癌因素、全球范围内肥胖人群增多和人口老龄化,伴有其他原发恶性肿瘤的泌尿道癌症患者人数可能正在增加4。本文将介绍一例63岁男性患者,他被诊断有膀胱癌和大肠癌,手术后出现多种并发症。

建议进行术前咨询并标记造口部位,帮助患者应对造口术后生活,选择一个理想位置和减少潜在术后并发症和其他未来问题5。在需要实施紧急手术时,往往无法标记患者的造口部位,无法为患者提供有关造口后的生活的辅导。在紧急情况下,不一定每次都能标记患者的造口部位,随后,造口定位不佳可能会降低患者的生活质量6。可能会影响外科医生在紧急外科手术中选择造口位置的因素包括脓毒症、水肿、肠道炎症、任何潜在疾病的性质、患者病情不稳定和恶化、时间有限。另外,在患者处于仰卧位时,很难判断皮肤皱折、评估体重指数,创造造口的工作常常分配给外科团队的初级医生。常见的与紧急造口手术相关的长期并发症包括皮肤问题、狭窄、脱垂、造口周围疝、侧瘘管和住院时间延长7,8。

除任何造口及其定位外,可能会影响患者自理能力和及时出院的紧急造口手术的其他后遗症包括缺乏术前咨询、查看造口的能力、管理造口和器具、心理问题7,9。

病例回顾

患者概况与主诉

患者为一位63岁男性,就诊主诉为直肠出血和血尿,有结直肠癌和膀胱癌既往病史。病史包括高血压和2型糖尿病。曾接受紧急前部切除以便形成结肠造口术末端,以及膀胱切除术以便形成回肠导管。

术后并发症

腹腔脓毒症

患者术后出现腹腔脓毒症,需要三次探查性腹腔镜以便实施腹腔冲洗。随后出现小肠和大肠缺血。外科医生估计残存小肠不足2米,随后在腹腔右侧实施回肠造口术。由于手术期间患者的病情,外科医生无法准确测量小肠长度。

回肠造口术位置

实施回肠造口的位置是在距离回肠导管大约2厘米处的12点钟方向。回肠造口术位置对造口护理、造口袋选择流程和患者自行护理造口的能力产生了巨大影响。

瘘管形成

患者于回肠导管处形成了一个瘘管,尿液开始泄漏至腹腔。为从回肠导管分流尿液,实施了双侧肾造口。不幸的是,患者的中线伤口裂开,造成肠道皮肤瘘管喷出,每天排放3至6升粪便排泄物。最初以为肠道皮肤粪便瘘管会随时间愈合,但并未如此。大约七个月后,尝试通过内窥镜关闭瘘管泄漏部位,但未能成功。

癌症复发

对内窥镜手术期间采集的组织进行活检,发现结肠癌复发。经医生集体讨论后,一致决定不再实施进一步外科干预。由于多次接受剖腹手术和随之而来的并发症,患者的病程对患者本人及医务人员来说都充满了挑战。

挑战

患者和医务人员面临的主要挑战是造口彼此相距太近、大量粪便经瘘管排出、造口并发症、对造口周围和伤口周围皮肤的保护。

回肠造口:在病例中,回肠造口术带来了双重挑战,即,回肠造口与皮肤齐平,以及回肠造口产生大量排泄物。

回肠导管:另外,患者的回肠导管收缩,需要插入一根Foley导管以防止狭窄。

瘘管:患者的中腹部肠道皮肤瘘管有三个开口,每天排泄3至6升粪便液体。

造口位置:所有造口彼此相距太近(图1)。

干预:造口和瘘管管理策略

造口周围皮肤护理

采用自来水龙头的温水清洗造口周围皮肤,用柔软编织布(Chux)擦干,然后用 CavilonTM无刺激屏障膜擦拭,以便保护皮肤。在某些情况下,如果皮肤腐烂明显,则使用Stomahesive® 保护粉提供额外保护,促进愈合。

造口袋选择策略

测量了造口和肠道皮肤瘘管直径,以便选择最符合造口和瘘管的各自管理需求的造口袋。这些造口和瘘管彼此相距太近。决定为回肠导管、回肠造口术和瘘管单独选择造口袋,以便准确测量每个造口和瘘管的排出物,便于更好地密封,以防止造口周围皮肤并发症。发现需要修剪所有造口袋的底板,以保持彼此分离和促进皮肤愈合(图2)。

回肠造口术采用一个锥形大容量造口袋,此造口袋连接一个长长的引流袋,以便于腾空造口袋。这是因为大量粪便排出物是水样便,根据Bristol大便图分类为7型10。曾试图通过药物(如洛哌丁胺、止泻宁、磷酸可待因和奥曲肽皮下注射)减少粪便排出量,但均告失败。

使用一个2件式柔软锥形系统管理回肠导管,以便于轻松地将Foley导管拧入底板。另外,大容量造口袋的长度符合Foley导管在原位的长度。

对于用于容纳瘘管排出物的伤口造口袋,在偏离中心的底部切口,以便尽可能保持造口袋彼此分离。

其他挑战

疼痛

为患者更换所有造口袋时遇到的一个问题是疼痛。从患者痛苦的面部表情可以看出,更换造口袋给他带来了巨烈的疼痛。尽管经常向患者灌输止痛和使用止痛药的重要性,但是他在大多数情况下拒绝使用任何镇痛剂。尽管患者的痛苦面部表情说明他正忍受疼痛,但他总是说操作结束后疼痛就会消失,因此他认为使用止痛药物没有益处。

由于患者在更换造口袋时会经受疼痛,对于此患者来说,最大限度减少造口袋的常规更换次数成为了一个根本策略。所经历的疼痛主要来自造口袋粘连、拆除造口袋、清理皮肤、和重新连接造口袋时在腹部施加的压力、。护理计划改为每周更换造口袋两次或只在泄漏时更换。患者可以很好地耐受修改后的护理计划。每天检查造口袋是否完整,以避免可能的泄漏情况。另外,鼓励医务人员和患者保持造口袋腾空,以便减轻重量、减小造口袋与皮肤之间粘连的张力和牵引。

身体形象和保持尊严

实施造口术后,胃肠或泌尿系统的正常解剖和生理学功能会发生改变11。需要在腹部开口,以便将大肠、膀胱或输尿管外引,分流肠道液体或尿液,然后通过外接造口袋收集排出物。这会极大地改变患者的身体外观和日常功

能11。在本病例中,由于有三个不同的造口袋,覆盖其大部分腹部,这些对其身体形象的影响加剧了三倍(图3)。

另外,肠道皮肤瘘管的排出物呈爆炸性,两个点像喷泉,一个点像喷气孔。这令患者非常难堪和沮丧,在更换造口袋时,每当瘘管以这种方式排泄排出物时,患者都非常抱歉。尽管无数次安慰他,这不是他的错,他无法控制瘘管排泄排出物的时间,但他仍然感到无奈无助。

在这种情况下,重要的是通过轻松谈话分散患者的注意力,避免他关注瘘管的存在和管理,使其情绪变得轻松一些,这个策略被认为很有效。这是在管理多个造口和瘘管的同时帮助患者保持尊严的一个重要因素。

控制异味

对于接受造口术的患者来说,粪便特有的异味对患者影响很大,在佩戴或腾空造口袋时会造成极大不安12。尽管在造口袋里滴过几滴桉树油,但是仍然很难控制从造口袋散发出来的异味。由于排出物的量,需要经常腾空造口袋,从而降低了在造口袋内滴桉树油的效果。这使患者及其家人感到非常羞愧,他们在病房内使用大量空气清晰剂表明了这一点。发现每周更换造口袋两次可以最大限度地减少异味,所以固定在每周一和周五更换造口袋。患者使用的粪便造口袋带一个活性炭过滤器,以便最大限度地减少异味。另外,在所有造口袋上连接长长的排空袋,以减少异味影响(图4和图5)。

出院计划和出院后无去处

另外一个问题是出院计划。对于本病例,由于护理比较复杂,例如需要更换造口袋,造口和瘘管排出量,加上他需要静脉输液和姑息治疗,出院后的去处非常有限。对患者而言,出院后回家很不现实。社区里没有足够的资源和服务可以满足患者需求。经发现,在患者所居住的区域附近,大多数养老院没有可以提供每日静脉输液的资源,社区护士无法长期更换他的造口袋。

曾尝试教患者和其妻子更换造口袋。花费了三周时间向患者和其妻子培训如何更换造口袋,但事实证明,由于更换造口袋的技术性要求较高,且无法预测造口和瘘管何时排泄排出物,他的妻子很难胜任为其更换造口袋。另外,他们需要吸引器械来协助更换造口袋。此外,如果发生多次泄漏,家里的耗材会不够用。

曾三次探讨养老院的选择,但在向护理科经理和富有经验的工作人员介绍更换造口袋的步骤后,他们都认为无法在其养老院内完成造口袋更换操作。此外,他们没有足够的资源和人力来完成此项工作。患者还需要静脉输液以补充经回肠造口术和瘘管排出的排泄物。提供了一份含照片的逐步指南介绍如何更换造口袋,以此向护理人员和养老院提供所有支持。还制作了一份幻灯片演示文稿。我们向所接触的机构保证,如果他们能够接纳患者,我们会持续提供造口治疗支持,但这些策略均告失败。

由于无法找到接纳患者的养老院,患者和其家人感觉到很受排斥。因此,造口治疗护士和社会工作者提供了情感支持。

讨论

大约五分之一的造口术通过紧急手术完成8。据报道,与回肠导管有关的并发症发生率在15%至65%之间,一个最常见的并发症是与造口或腹壁相关的变化,包括造口狭窄和收缩13。

因此,对任何术后并发症的管理,需要对患者护理采取整体和跨专业的方式9。在理想情况下,回肠造口术和回肠导管造口应该从腹壁突出数厘米。延长出口是因为粪便和尿液排出物的量、一致性和构成成分。另外,在造口齐平或收缩时,对造口大量排出物的控制以及对皮肤的保护也构成挑战14。

管理干预围绕三个目标:保持皮肤完整性、最大限度地减轻不必要的疼痛和控制流出物。鉴于本病例的复杂性,确保制订一个造口袋计划,以促进造口袋与皮肤紧密粘合,保持密封完整性是主要目标之一。这有助于保持造口/瘘管周围皮肤的完整性。造口袋佩戴不好,常常会造成造口术后流出物与皮肤接触15。

皮肤完整是促进患者接受造口术后获得积极结果的起点。这是所有造口护理的基础,并且已获得共识。人们认识到,只有能够获得要使用的必要产品,才能实际克服这些挑战。

使用水凝胶底板管理患者的造口,以便保持皮肤完整性,这也有助于维护患者的自尊和身体形象。选择的造口袋系统是2件式锥形大容量Dansac Gx plus造口袋,可以保持密封。底板柔软的凸起将与皮肤齐平的回肠造口稍微向外推出,以防止泄漏。另外,它可以很好地卡在回缩的回肠导管周围。使用凸出式水凝胶底板可以提高造口袋粘连的牢固性,保护造口周围皮肤,因此被认为是最佳做法15。

Gx plus可以长时间佩戴,以便造口袋每周只需更换两次。这不仅节省时间,而且节省成本,最重要的一点是,可以防止给患者造成不必要的疼痛。随着造口袋泄漏的发生率降低、征兆减少,患者的焦虑和压力水平也随之下降16。

研究了回肠造口术的大量排出物问题,结果未发现任何感染迹象。因此,治疗外科团队将排出物的量和内含物归因于残留肠道长度过短、肠道组织易受刺激和患者潜在的恶性肿瘤。未试图通过诊断性干预以确定肠功能不全或肠道衰竭的潜在原因。在患者入住并且在本卫生服务机构接受治疗的全年里,为患者制订的造口袋计划行之有效。尽管所有药物和其他干预方法都试图降低排出量,但造口术/瘘管的粪便排出量始终波动。

除了在管理造口和肠道皮肤瘘管时遇到的实际挑战外,还要考虑患者的福祉问题。在其患病的所有阶段(术前、术后和临终护理),他需要知道并感觉到他在精神和躯体两方面都得到了支持。我们认识到,患者在接受造口术后会出现较大心理压力,因为他们感觉到在身体和情感方面都失去了独立性16。

患者经常拒绝任何止痛药物以减轻更换造口袋时他所经历的疼痛。必须承认,不同性别、不同文化人群和不同种族背景对疼痛的观念以及对疼痛作出反应或耐受疼痛的方式有所不同,有些人可能会表现地反应过激,有些人表现出相对耐受或坚忍17。由于患者来自一个少数民族,是一位牧师,虔诚地信教可能对他看待和使用止痛剂的影响很大17。经过造口治疗护士的教育、咨询和看护,患者的焦虑水平有所缓解16。事实上,患者需要在精神和情绪上感觉到持续的支持。

大多数患者会向医疗提供机构寻求指导,以了解如何接受和应对他们的病症。对患者来说,抱有希望18是一个重要的激励和应对因素,而正是希望让患者一直坚持下来。为有效应对和做出决策,抱有希望是一个重要方面,与造口术后的生活和生活质量相关7。对于让患者应对和理解他们身上所发生的一切,医疗提供机构扮演着一个非常重要的角色。因此,为患者及其家人提供整体护理至关重要。

另外,由于克服了种种挑战,并且造口治疗护士长时间为患者提供护理,造口治疗护士与他之间的治疗关系得到了巩固。这在护理的连续性方面为患者带来一些安慰,因为无论更换造口袋有多困难,造口治疗护士总能找到克服这些困难的方法。

与患者建立了一种基于信任、相互尊重和轻松的治疗关系,这种关系极大地帮助了此复杂病例的管理。及早建立和睦关系有助于患者的长期临床和治疗管理。

皮肤完整是促进患者接受造口术后获得积极结果的起点。这是所有造口护理的基础,并且已获得共识。人们认识到,只有能够获得要使用的必要产品,才能实际克服这些挑战。在患者住院的全年里,为患者制订的造口袋计划行之有效。尽管为患者的护理采取了药物和其他干预,但排出物始终波动。

该患者无法出院回家,也无法转至养老院。但是,采取循证造口术和姑息治疗措施后,患者的临终生活仍然比较舒适。

结论

从此病例获得的最佳成果是在解决所面临的挑战所带来的学习经验。这强化了患者、其家人、造口治疗护士和医疗团队及早建立治疗关系的价值所在。此病例明确证明,能够获得不同产品使得造口治疗护士的任务易于管理。另外,重要的一点是,随着更复杂案例的出现,造口治疗服务需要持续改进和发展。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Melanie C Perez

BSN, RN, STN, Grad Cert (Stomal Therapy), Grad Dip (Acute Care), MN (Acute Care)

St George Public Hospital, Kogarah, NSW, Australia

Email Melanie.Perez@health.nsw.gov.au

References

- Australian Government Cancer Australia. Bladder Cancer [Internet]. Australia: Bladder Cancer Statistics; 2018 [cited 2018 Sept 4]. Available from: https://bladder-cancer.canceraustralia.gov.au/statistics

- Australian Government Cancer Australia. Bowel Cancer [Internet]. Australia: Bowel Cancer Statistics; 2018 [cited 2018 Sept 4]. Available from: https://bowel-cancer.canceraustralia.gov.au/statistics

- Calderwood AH, Huo D & Rubin DT. Association between colorectal cancer and urologic cancers. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168(9):1003–1009. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.9.1003.

- Liu Z, Chen G, Zhu Y & Li D. Simultaneous radical cystectomy and colorectal cancer resection for synchronous muscle invasive bladder cancer and cT3 colorectal cancer: Our initial experience in five patients. J Res Med Sci 2014; 19(10):1012–5.

- Cronin E. Stoma siting: why and how to mark the abdomen in preparation for surgery. Gastrointestinal Nursing [Internet] 2014 Apr [cited 2017 Oct 16]; 12(3):12–19. Available from: CINAHL Complete.

- Slater R. Optimizing patient adjustment to stoma formation: siting and self-management. Gastrointestinal Nursing [Internet] 2010 Dec [cited 2017 Oct 17]; 8(10): 21–25. Available from: CINAHL Complete.

- Qureshi A, Cunningham J & Hemandas A. Elective vs emergency stoma surgery outcomes. World J Surg Surgical Res 2018; 1:1050.

- Pengelly S, Reader J, Jones A, Roper K, Douie WJ & Lambert AW. Methods for siting emergency stomas in the absence of a stoma therapist. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014; 96:216–218. doi 10.1308/003588414X13814021679717.

- Wasserman MA & McGee MF. Preoperative Considerations for the Ostomate. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017; 30:157–161.

- Blake MR, Raker JM, Whelan K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther [Internet] 2016 [cited 2019 Feb 3]; (7):693. Available from: https://login.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgih&AN=edsgcl.462472621&site=eds-live

- Jayarajah U & Samarasekera D. Psychological adaptation to alteration of body image among stoma patients: a descriptive study. Indian J Psychol Med [Internet] 2017 Jan [cited 2017 Oct 31]; 39(1):63–68. Available from: Academic Search Ultimate.

- Williams J. Flatus, odour and the ostomate: coping strategies and interventions. BJN [Internet] 2008 Jan 24 [cited 2017 Oct 31]; 17(2):S10–4. Available from: CINAHL Complete.

- Szymanski KM, St-Cyr D, Alam T & Kassouf W. External stoma and peristomal complications following radical cystectomy and ileal conduit diversion: a systematic review. OWM 2010; 56(1):28–35.

- Boyles A & Hunt S. Care and management of a stoma: maintaining peristomal skin health. BJN [Internet] 2016, Sep 22 [cited 2017 Oct 30]; 25(17):S14–S21. Available from: CINAHL Complete.

- Nichols T & Purnell P. Are there advantages to barrier rings? J WCET 2014; 34(1):7–11 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jan 28]. Available from: https://login.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsihc&AN=edsihc.273020111481012&site=eds-live

- Lee MWK, Wan YP, Lui TYL & Lo SKC. Quality of life, anxiety and depression levels of Chinese stoma patients in Hong Kong. WCET J [Internet] 2016 Jan [cited 2019 Jan 28]; 36(1):28–33. Available from: https://login.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=113971590&site=eds-live

- Khan M, Raza F & Khan I. Pain: history, culture, and philosophy. Acta Med Hist Adriat [Internet] 2015, Jan [cited 2017 Oct 31]; 13(1):113–130. Available from: Academic Search Ultimate.

- Chunli L & Ying Q. Factors associated with stoma quality of life among stoma patients. Int J Nurs Sci 2014; 1(2):196–201 [Internet] [cited 2017 Nov 1]; (2):196. Available from: Directory of Open Access Journals.