Volume 39 Number 3

Podoconiosis: an important but forgotten cause of non-filarial lymphoedema

Merna Adly, Kwadwo Mponponsuo and Ranjani Somayaji

Keywords Podoconiosis, lymphoedema, elephantiasis

For referencing Adly M et al. Podoconiosis: an important but forgotten cause of non-filarial lymphoedema. WCET® Journal 2019; 39(3):10-14

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.3.10-14

Abstract

Podoconiosis is a preventable, non-infectious and non-communicable cause of lymphoedema leading to chronic swelling of the foot and lower leg. Most prevalent in Africa, Central America and India, it is caused by long-term exposure to irritant red volcanic clay soil. Risk factors for disease are related to the absence or inadequacy of footwear. However, not all those at risk develop the disease, indicating that both genetic and environmental predispositions contribute to disease development.

Symptoms of podoconiosis include asymmetrical limb swelling with associated itching, burning sensation and lymphatic ooze. Late stages are characterised by irreversible swelling and joint fixation. Due to the disfiguring nature of the disease, those affected often experience social stigmatisation. Associated economic losses result from reduced productivity and absenteeism. The disease must be differentiated from conditions such as filarial lymphoedema and congenital lymphoedema, which can have similar presentations, such that appropriate therapy can be implemented.

Primary management of podoconiosis is prevention which involves the regular use footwear such as shoes and education of the disease. In the early stages of podoconiosis, compression therapy and limb elevation delays clinical progression in affected individuals. In later stages, changes are irreversible; however, additional therapy can include surgical intervention and limb elevation for symptom control. Psychosocial care is also needed to address the mental distress associated with the disease. Despite the preventable nature of podoconiosis, it remains prevalent in developing countries, necessitating further investment of resources.

Introduction

Podoconiosis is a form of non-filarial (infectious disease) lymphoedema and is a debilitating chronic swelling of the foot and lower leg. Podoconiosis occurs with long-term exposure to irritant red volcanic clay soil in the highland regions of Africa, Central America and India1. It is caused by the passage of microparticles of volcanic silica and aluminum silicates through the skin of those walking barefoot in areas with a high content of volcanic soil2. Podoconiosis is a non-communicable (no person-to-person spread) tropical disease with high potential for eradication, but it remains a neglected condition.

Globally, it is estimated that there are four million people affected with podoconiosis3. The highest reported prevalence values are in Africa, including 8.08% in Cameroon, 7.45% in Ethiopia, 4.52% in Uganda, 3.87% in Kenya, and 2.51% in Tanzania4. In India, the prevalence was estimated to be 0.21%, primarily from Manipur, Mizoram and Rajasthan States4. The prevalence is higher in adults compared to children or adolescents, and is likely due to a longer duration of exposure to volcanic soil4.

Several risk factors have been implicated in the development of podoconiosis such as a family history of the disease, absence of footwear, poor foot hygiene and low frequency of wearing shoes5. Other factors, such as being from a medium income household and having primary education, lower the risk of developing podoconiosis5. Studies have shown, however, that even in those with risk factors, podoconiosis develops in only a subgroup of people. One study conducted in Ethiopia found familial clustering, with a high heritability of 63%6. A genome-wide scan of 194 cases and 203 controls, alongside family-based testing, demonstrated association between variants in HLA Class II loci with podoconiosis, suggesting that the condition may be a T cell-mediated inflammatory disease6.

Social stigma of patients with podoconiosis is widespread. It is, at times, erroneously believed to run in families – which may occur due to the same exposures and not due to person-to-person spread – leading to isolation of those afflicted7. However, the diagnosis of podoconiosis is linked with a lower quality of life. Additionally, similar to other chronic illnesses, a recent study identified depression prevalence to be 12.6% amongst individuals living with podoconiosis8. Factors associated with this include social stigmatisation, living in an urban area, being illiterate, and being single9. Economic losses are also enormous since it mainly affects adults. This leads to reduced productivity and absenteeism, and contributes to the disease–poverty–disease cycle10. The estimated productivity losses per patient amount to 45% of working days per year, causing a significant economic impact11.

Clinical features

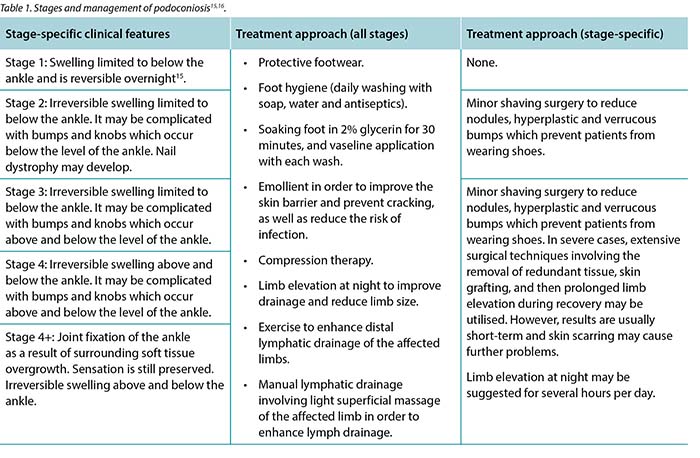

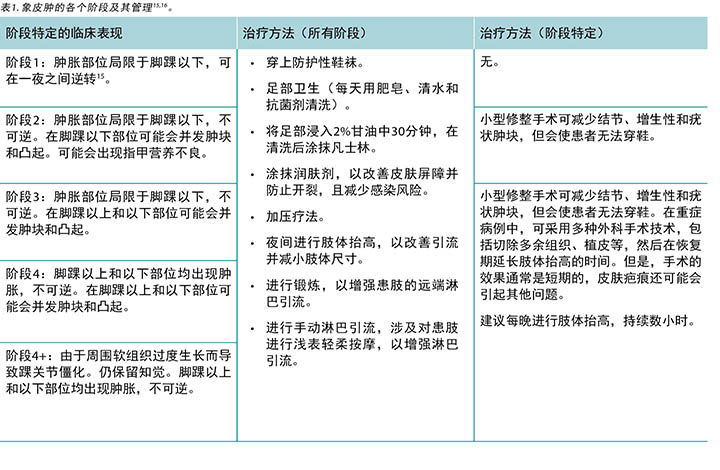

Podoconiosis presents as bilateral asymmetrical lower limb swelling below the knee lasting more than a month, plus any one of the following symptoms – skin itching or burning, foot oedema, lymph ooze (due to build-up and overflow of lymph fluid from the vessels), prominent skin markings, rigid toes and/or mossy papillomata12 (Figures 1 & 2). Podoconiosis has a curable pre-elephantiasic phase but causes lifelong disability once the elephantiasis phase is established. Progression to chronic disease (incurable state) occurs over years and has five stages (Table 1). Podoconiosis demonstrates changes of chronic lymphoedema with extensive sclerosis (hardening of tissue), loss of elastic fibres, verrucous acanthosis (hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic plaques), and reactive changes of eccrine structures (destruction of sweat and sebaceous glands)13,14,15,16.

Figure 1 Podoconiosis with foot and lower limb deformity.

Figure 2: Podoconiosis with gross nodular involvement.

Pathophysiology

Traditionally, it has been identified that silicate particles absorbed via the skin induce an inflammatory process of the lower leg lymphatics. However, more recent work has identified that minerals enriched in incompatible elements such as calcium, potassium, magnesium and sodium are strongly implicated in the development of the disease14. Persons with dry skin have a greater risk – due to skin cracking or splitting – of particle absorption, lymphoedema and infection15. Silicate particles entering through skin are then thought to be taken up by macrophages in the lower limb lymphatics, causing subendothelial oedema, lymph inflammation and, eventually, destruction of the lymphatic lumen. In addition, immune cells are activated which contribute to ongoing inflammation. Eventually, these changes lead to clinical lymphoedema. The chronic inflammation transforms the swollen soft tissues to hard and thickened skin over time, contributing to the irreversibility of the condition.

Approach to treatment

Research has shown that the provision of a simple, inexpensive package of lymphoedema self-care has considerable impact on both clinical progression and self-reported quality of life of affected individuals2. Several qualitative research studies show that culturally-informed education programmes that increase the perceived controllability of stigmatised hereditary health conditions like podoconiosis have promise for increasing preventative behaviours and reducing interpersonal stigma17. Additionally, several factors have been described as barriers to preventive behaviour, including uncomfortable footwear for farm activities and sports, affordability of shoe wear, shortage of soap for washing, as well as cultural influences promoting gender inequality which result in women being least able to access shoes18. As a result, it is essential to link podoconiosis-affected families with local governmental or non-governmental organisations providing socioeconomic support for households so families are able to better engage in behaviours that will reduce the risk of podoconiosis18. Finally, in order to address the high burden of mental distress among people with podoconiosis, it is essential to integrate psychosocial care into the current morbidity management of podoconiosis19.

Differential diagnosis

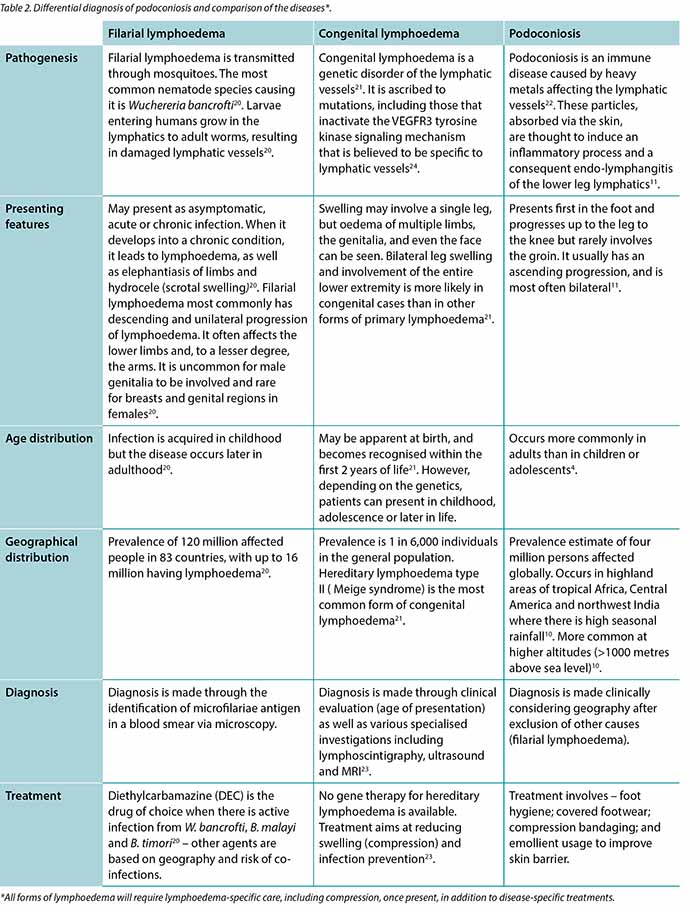

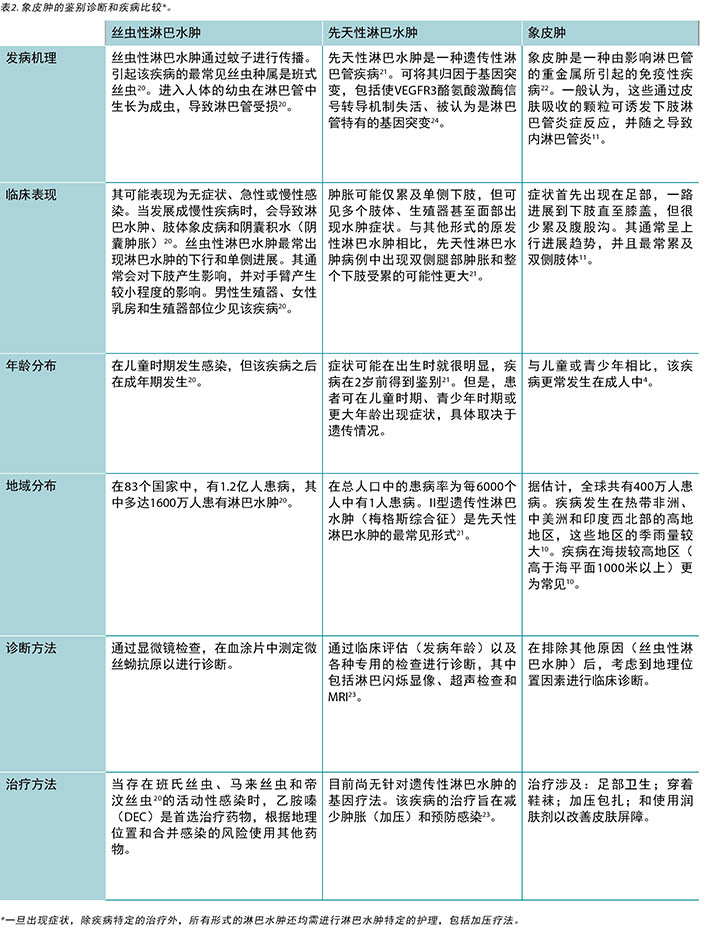

Accurate diagnosis of podoconiosis is essential for appropriate patient management and treatment. The diagnosis is established clinically as there is no gold standard diagnostic tool. It is a diagnosis of clinical exclusion based on history, physical exam, and certain antigen-antibody specific tests to exclude diseases included in the differential diagnosis such as filarial (infectious) lymphoedema and congenital lymphoedema. The differentiating features of filarial lymphoedema, congenital lymphoedema and podoconiosis are detailed below (Table 2).

Conclusion

Podoconiosis is a chronic swelling of the foot and lower leg caused by long-term exposure to irritant red volcanic clay soil in the highland regions of Africa, Central America and India. Those affected by podoconiosis have significant morbidity, loss of productivity, and frequently experience stigma and isolation. As there are simple measures for prevention, the elimination of podoconiosis is feasible. Global and local advocacy efforts for shoe provision and education are therefore urgently needed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

象皮肿:一个重要但被忽视的非丝虫性淋巴水肿病因

Merna Adly, Kwadwo Mponponsuo and Ranjani Somayaji

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.3.10-14

摘要

象皮肿是一种可预防的非感染性和非传染性淋巴水肿病因,可导致足部和下肢慢性肿胀。象皮肿在非洲、中美洲和印度的患病率最高,由长期接触刺激性红色火山粘土所致。疾病的风险因素与患者未穿鞋袜或鞋袜保护性不足相关。但是,并非所有处于风险之中的人都会患病,这表明遗传和环境易感性也是患病与否的影响因素。

象皮肿的病症包括肢体不对称肿胀,伴有瘙痒、烧灼感和淋巴液渗出。其晚期症状表现为不可逆性肿胀和关节僵化。由于该疾病可造成外貌损伤,因此,受累患者通常会有社交耻辱感。生产力的下降和旷工缺勤的情况还会造成相关的经济损失。该疾病必须与具有类似表现的丝虫性淋巴水肿和先天性淋巴水肿等疾病进行区分,以便对症治疗。

象皮肿的初期管理为实施预防措施,涉及常规使用鞋袜(如穿鞋)和进行疾病教育等。在象皮肿的早期阶段,加压疗法和肢体抬高法均可延缓患病个体的临床进展。在后期阶段,症状变化是不可逆的;但是,可使用其他疗法,包括外科手术和肢体抬高法来控制症状。同时,还需要心理照护来解决与疾病相关的精神困扰。尽管象皮肿具有可预防性,但其在发展中国家的患病率仍然较高,因此有必要进一步投入相关资源。

前言

象皮肿是一种非丝虫性(感染性)淋巴水肿,该疾病可导致足部和下肢慢性肿胀,感到虚弱无力。在非洲、中美洲和印度1等高地地区,患者因长期接触刺激性红色火山黏土而发生象皮肿。这是因为在火山土含量较高的地区,火山二氧化硅和铝硅酸盐微粒会通过皮肤进入赤脚行走的当地人体内2。象皮肿是一种非传染性(非人传人)热带疾病,具有较高的根治可能性,但仍是一种被忽视的疾病。

在全球范围内,估计有四百万人患有象皮肿3。报告的患病率最高的地区为非洲,包括喀麦隆(8.08%)、埃塞俄比亚(7.45%)、乌干达(4.52%)、肯尼亚(3.87%)和坦桑尼亚(2.51%)4。在印度地区,估计的患病率值为0.21%,患者主要来自曼尼普尔邦、米佐拉姆邦和拉贾斯坦邦4。与儿童或青少年相比,成人的患病率更高,这很可能是由于其接触火山土的时间更长4。

象皮肿的发生涉及一些风险因素,例如存在疾病家族史、未穿鞋袜、足部卫生较差和穿鞋频率低等5 。其他因素(例如来自中等收入家庭和受过初等教育)则会降低象皮病患病风险5。然而,研究已表明,即使在具有风险因素的人群中,也仅在人群亚群中发生象皮肿。在埃塞俄比亚进行的一项研究发现了家族聚集性现象,疾病的遗传率高达63%6。对194例病例和203例对照病例进行了全基因组扫描筛查,同时也进行了基于家族的检测,结果证明了HLA II类基因座变异体与象皮肿的相关性,这表明该疾病可能是T细胞介导的炎症性疾病6。

象皮肿患者存在普遍的社交耻辱感。有时,人们错误地将象皮肿视为家族传染性疾病(但实际上可能是由于存在相同的接触情况而非由于人传人),因此会导致患者隔离的情况7。然而,象皮肿这一诊断结果与生活质量较低有关。此外,与其他慢性病类似,最近的一项研究发现,在患有象皮肿的人群中,抑郁症的患病率为12.6%8。与之相关的因素包括社交耻辱感、居住在市区、未受教育和单身9。疾病带来的经济损失也很大,因为它的主要影响人群为成人。其导致生产力下降和旷工缺勤,并加剧了疾病-贫困-疾病的周期循环10。据估计,每例患者的生产力损失占其每年工作日数的45%,这将导致严重的经济影响11。

临床表现

象皮肿表现为持续一个月以上的膝盖以下双侧下肢不对称肿胀,并伴有以下任何一种症状:皮肤瘙痒或灼烧感、足部水肿、淋巴液渗出(由于淋巴液积聚并从血管溢出)、明显的皮肤斑纹、脚趾僵硬和/或苔藓样乳头状瘤12(图1和2)。象皮肿存在可治愈的象皮病前阶段,但一旦确立为象皮病阶段,就会导致终身残疾。该慢性病(无法治愈状态)的进展期为数年,分为五个阶段(表1)。象皮肿表现为慢性淋巴水肿的改变,伴有大量硬化(组织硬化)、弹性纤维丢失、疣状棘皮症(色素过度沉着和角化过度斑块)以及外分泌结构的反应性改变(汗液和皮脂腺的破坏)13,14,15,16。

图1:象皮肿及足部和下肢畸形。

图2:象皮肿及受累的严重足部结节。.

病理生理学

传统上,已发现通过皮肤吸收的硅酸盐颗粒会诱发下肢淋巴管的炎症反应。但是,最近的研究发现,富含钙、钾、镁和钠等不相容元素的矿物质也与疾病的发作密切相关14。皮肤干燥者因皮肤开裂或裂开而导致颗粒吸收、淋巴水肿和感染的风险更高15。研究还认为,穿过皮肤进入的硅酸盐颗粒被下肢淋巴管中的巨噬细胞吸收,引起皮下水肿、淋巴炎症反应,并最终破坏淋巴管腔。此外,免疫细胞被激活,导致炎症反应持续。最终,这些改变导致患者出现淋巴水肿的临床表现。慢性炎症反应会随着时间的推移将肿胀的软组织转化为坚硬且增厚的皮肤,从而导致该疾病的不可逆性。

治疗方法

研究表明,提供简单廉价的淋巴水肿自我护理方案,对患病个体的临床进展和自我报告的生活质量都具有相当大的影响 2。几项定性研究表明,传达文化信息的教育课程如能增加人们对带来耻辱感的遗传性疾病(如象皮肿)的感知可控性,则有望增加人们的预防性行为并降低人际耻辱感17。此外,已发现一些因素对实施预防性行为造成了障碍,包括在农场活动和体育活动中穿着的鞋袜不舒适、鞋袜的负担能力、洗涤用肥皂的缺乏,以及造成性别不平等并导致女性最难以获取鞋袜的的文化影响等18。因此,很有必要将患象皮肿的家庭与为家庭提供社会经济支持的地方政府或非政府组织联系起来,以便使这些家庭能够更好地参与到减少象皮肿患病风险的预防性行为中18。最后,为了解决象皮肿患者中较大的精神困扰负担,必须将心理照护融入象皮肿当前的发病率管理中19。

鉴别诊断

象皮肿的正确诊断对于进行适当的患者管理和治疗至关重要。由于目前尚无该疾病诊断工具的金标准,因此仅可在临床上确定诊断。这种诊断是一种基于病史、体检和某些抗原抗体特异性测试的临床排除诊断,以排除鉴别诊断中所包含的疾病,如丝虫性(感染性)淋巴水肿和先天性淋巴水肿。丝虫性淋巴水肿、先天性淋巴水肿和象皮肿的鉴别特征详述如上(表2)。

结论

象皮肿是一种在非洲、中美洲和印度等高地地区多发的足部和下肢慢性肿胀,其原因是长期接触刺激性红色火山黏土。象皮肿受累患者具有很高的发病率,其生产力下降,并经常有耻辱感和孤立感。由于存在简单的预防措施,消灭象皮肿是可行的。因此,迫切需要在全球各地开展有关鞋袜供应和教育的宣传工作。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Merna Adly

MD candidate

Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Kwadwo Mponponsuo

MD

Department of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Ranjani Somayaji*

BScPT, MD, MPH, FRCPC

Departments of Medicine; Microbiology, Immunology & Infectious Disease; Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Email rsomayaj@ucalgary.ca

* Corresponding author

References

- Deribe K, et al. The feasibility of eliminating podoconiosis. Bull WHO 2015;93(10):712–718.

- Sikorski C, et al. Effectiveness of a simple lymphoedema treatment regimen in podoconiosis management in Southern Ethiopia: one year follow-up. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4(11):e902.

- Dejene F, Merga H, Asefa H. Community based cross sectional study of podoconiosis and associated factors in Dano district, Central Ethiopia. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2019;13(1):e0007050.

- Deribe K, et al. Global epidemiology of podoconiosis: a systematic review. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2018;12(3):e0006324.

- Feleke BE. Determinants of podoconiosis, a case control study. Ethiopian J Health Sci 2017;27(5):501–506.

- Tekola Ayele F, et al. HLA Class II locus and susceptibility to podoconiosis. NEJM 2012;366(13):1200–1208.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health 2016;8(Suppl 1):i53–70.

- Bartlett J, et al. Depression and disability in people with podoconiosis: a comparative cross-sectional study in rural Northern Ethiopia. Int Health 2016;8(2):124–31.

- Mousley E, et al. The impact of podoconiosis on quality of life in Northern Ethiopia. Health Qual Life Outcome 2013;11(1):122.

- Nenoff P, et al. Podoconiosis – non-filarial geochemical elephantiasis – a neglected tropical disease? JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 2010;8(1):7–13.

- Kebede B, et al. Integrated morbidity mapping of lymphatic filariasis and podoconiosis cases in 20 co-endemic districts of Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018;12(7):e0006491.

- Kihembo C, et al. Risk factors for podoconiosis: Kamwenge District, Western Uganda, September 2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;96(6):1490–1496.

- Wendemagegn E, Tirumalae R, Boer-Auer A. Histopathological and immunohistochemical features of nodular podoconiosis. J Cutan Pathol 2015;42(3):173–81.

- Cooper JN, et al. Regional bedrock geochemistry associated with podoconiosis evaluated by multivariate analysis. Environ Geochem Health 2018;05:05.

- Ferguson JS, et al. Assessment of skin barrier function in podoconiosis: measurement of stratum corneum hydration and transepidermal water loss. Br J Dermatol 2013;168(3):550–554.

- Molla YB, et al. Patients’ perceptions of podoconiosis causes, prevention and consequences in East and West Gojam, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2012;12:828–828.

- Ayode D, et al. Association between causal beliefs and shoe wearing to prevent podoconiosis: a baseline study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016;94(5):1123–8.

- Tora A, et al. Health beliefs of school-age rural children in podoconiosis-affected families: a qualitative study in Southern Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017;11(5):e0005564.

- Mousley E, et al. Mental distress and podoconiosis in Northern Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Int Health 2015;7(1):16–25.

- Shenoy RK. Clinical and pathological aspects of filarial lymphedema and its management. Korean J Parasitol 2008;46(3):119–125.

- Rockson SG. Lymphedema. Am J Med 2001;110(4):288–295.

- Yime, M, et al. Epidemiology of elephantiasis with special emphasis on podoconiosis in Ethiopia: a literature review. J Vector Borne Dis 2015;52(2):111–5.

- Murdaca G, et al. Current views on diagnostic approach and treatment of lymphedema. Am J Medicine 2012;125(2):134–140.

- Irrthum A, Karkkainen MJ, Devriendt K, Alitalo K, Vikkula M. Congenital hereditary lymphedema caused by a mutation that inactivates VEGFR3 tyrosine kinase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:295-301.