Volume 39 Number 4

Retrospective review on the effectiveness of compression therapy in venous leg ulcer healing at a wound care centre in Hong Kong

Michelle Lee, Ka Wai Wong and Ka Kay Chan

Keywords Venous ulcer, compression bandage, compression stocking, elastic tubular compression device

For referencing Lee M et al. Retrospective review on the effectiveness of compression therapy in venous leg ulcer healing at a wound care centre in Hong Kong. WCET® Journal 2019;39(4):24-31

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.4.24-31

Abstract

Introduction Venous ulcers are a serious clinical consequence of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). The basis for successful management is compression therapy such as compression bandages, compression stockings and/or elastic tubular compression devices.

Aim The purpose of this study is to undertake a retrospective review on the effectiveness of compression therapies in a wound care nurse clinic in Hong Kong.

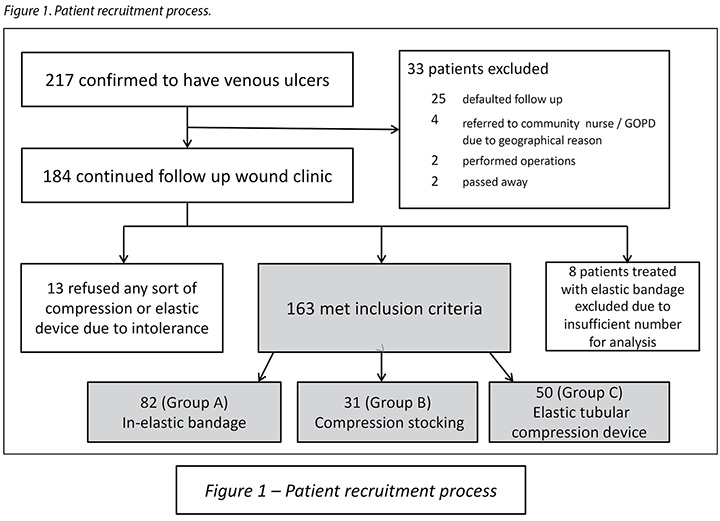

Method Patients in the clinic who presented with lower limb ulcers which showed either the signs and symptoms of CVI with an ankle brachial index >0.8 or where CVI was confirmed by Duplex scan were included in this study (Figure 1). The search period was from the start of treatment (Week 0) up to 24 weeks.

Results Time to heal was compared by using the log-rank test; 152 wounds healed within 24 weeks, with an overall healing rate of 93.3%. A total of 90.2% of wounds healed with compression bandages, 93.5% of wounds healed with compression stockings, and 98% of wounds healed with elastic tubular compression devices. The mean healing time was 10 weeks, 8 weeks and 9 weeks respectively.

Discussion In view of the various wound sizes between the three groups, there was relatively less difference in the overall wound healing rate among the three groups – relative risk (RR)<1. For ulcers sized >4cm2 to ≤12cm2, the difference in the wound healing rate between using compression bandages rather than compression stockings was found to be only 0.8% (RR=1.08).

Conclusion Taking into account the result from our study and considering both economic factors and patients’ convenience, elastic tubular compression devices may be more suitable for our group of patients.

Introduction

Venous ulcers are one of the most common wound problems in clinical practice and are a serious clinical consequence of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). In the United States, it is estimated that around 500,000–600,000 people are treated for venous ulcers in wound centres annually1. In Australia, a study has shown that community nurses spend around 50% of their time treating venous ulcers2. Although the prevalence and incidence for people with venous ulcers in Hong Kong are not well documented, a study conducted in the community nursing services of one district (Kwun Tong) found that there were around 200 patients receiving wound care from community nurses each month, around 11% of these for leg ulcers3.

The treatment of venous ulcers requires expensive wound dressing materials, compression therapy, pharmacological therapy, debridement and surgical interventions4. In 2002, it was estimated that Australia’s national health system spent around A$114 a month for each patient on the management of their venous ulcers4. In the United States, Ma et al.5 performed a cohort study on 84 patients within a period of 6 months and found the mean total cost of treating venous ulcers was US$15,732. This evidence shows that venous ulcers create a huge financial burden on the healthcare system.

The management of venous ulcers is not only a great burden to both the healthcare system and to the nurses, but it also adversely affects patients’ physiological and psychosocial wellbeing, and also has a direct impact on the quality of life of elderly patients6,7. Physically, pain and immobility can impair their activities of daily living8. Psychologically, it is reported that venous ulcers can result in various problems such as feelings of helplessness, a loss of self-esteem, and increased stress and anxiety6,9. All of these negative impacts may impair the initial inflammatory responses, disturb the neuro-endocrine immune equilibrium and, finally, affect wound healing10,11.

Literature Review

The basis for successful management of venous ulcers is compression therapy. It is believed the application of compression therapy to the limbs will lead to reabsorption of interstitial fluid, promote venous return, shift blood volume from peripheral to central circulation, reduce venous pressure, and prevent venous stasis12-15.

The therapy consists of either a compression bandage system or elasticated compression stockings. Studies show that the mean healing time for using short-stretch (inelastic) compression bandages was around 12–24 weeks, while 50% of patients with wounds healed within 6 months when using long-stretch (elastic) compression bandages16–17. The effectiveness of compression stockings has also been demonstrated by various research. A study conducted by Dolibog et al.18 shows the healing rate using compression stockings with pressure around 30–40mmHg over a 2 month timeframe to be 56.7%. When comparing the time for ulcer healing between a two-layer compression stocking (35–40mmHg) and a four-layer compression bandage (40mmHg), Ashby19 observed the median time to ulcer healing for both were similar – 70.9% in 99 days and 70.4% in 98 days respectively. In addition, a meta-analysis conducted by Amsler, Willenberg & Blättler20 reports that the healing of stockings (35–56mmHg) was greater than that of bandages (27–49mmHg) (62.7% vs 46.6%; p<0.00001) and that the average time to healing was 3 weeks shorter for compression stockings (p=0.0002). Mauck et al.21 also performed a comparative systematic review and meta-analysis of compression modalities for venous ulcer healing. The review demonstrates there is no overall difference between compression stockings and compression bandages in ulcer healing, nor in time to ulcer healing.

Elasticated tubular compression devices are mainly used to help reduce lower limb oedema. In 2003, Bale & Harding22 conducted a study using three layers of graduated Tubigrip (Mölnlycke) for patients with venous ulcers and found a 50% healing rate within 12 weeks. In addition, Weller23 performed a randomised control trial on the wound healing rate of a graduated three-layer tubular device compared to inelastic compression bandages. Although the mean pressure was consistently at least 13mmHg higher in the inelastic bandage group, the result reflected a higher healing rate within the tubular device group in 12 weeks (74% vs 46%; p=0.05). However, further related studies on this area were limited.

Methods

Study setting

The wound care nurse clinic in the hospital in this study aims to provide continuity care for patients with acute and chronic wounds. For patients with venous ulcers, our standard treatment regimen is to wash the lower limbs using soap and tap water, followed by application of hypoallergenic cream to moisturise the skin. Standard wound dressings for large amounts of exudate are Hydrofiber (ConvaTec), Gelfiber ((Durafiber) Smith & Nephew), or a foam dressing. Alginate dressings are normally for moderate amounts of exudate. For infected or severe colonised wounds, hypertonic sodium chloride dressings or Hydrofiber, Gelfiber or foam dressings containing silver are used.

In accordance with international guidelines, the majority of our patients are treated with compression therapy such as elastic (Setopress, Mölnlycke) or inelastic bandages (Pütter-Verband, Hartmann), compression stockings (Venosan 6002, Swisslastic Ag St. Gallen) or elastic tubular compression devices (Lastogrip, Hartmann) according to the patients’ occupation, activities, age, and compliance. All nursing staff working in the wound clinic are trained to perform bandage application. However, due to some patients in our clinic not tolerating compression bandages, class 2 compression stockings are usually applied to provide medium support (23–32mmHg). With patients who are unable to tolerate either compression bandages or compression stockings, it is suggested that they use an elastic tubular compression device to control lower limb oedema. Pressure transducer (Kikuhime small probe, MediTrade) is used to measure the pressure on the medial aspect at the ankle. Normal dressing frequency is twice weekly unless required more frequently for excessive amounts of exudate.

Aim

The purpose of this study is to undertake a retrospective review on the effectiveness of compression therapies employed in the wound care nurse clinic of a university hospital in Hong Kong.

Inclusion / exclusion criteria

Patients were included who had lower limb ulcers with signs and symptoms of CVI with an ankle brachial index >0.8 or where CVI was confirmed by Duplex scan.

Patients were excluded if they met the inclusion criteria but refused to have any sort of compression nor elastic device. They were also excluded if they had recent deep vein thrombosis or cardiac or respiratory problems for which compression therapy is contraindicated. In addition, patients with mixed ulcers or causes of ulceration other than venous disease were excluded from the study.

Patient recruitment

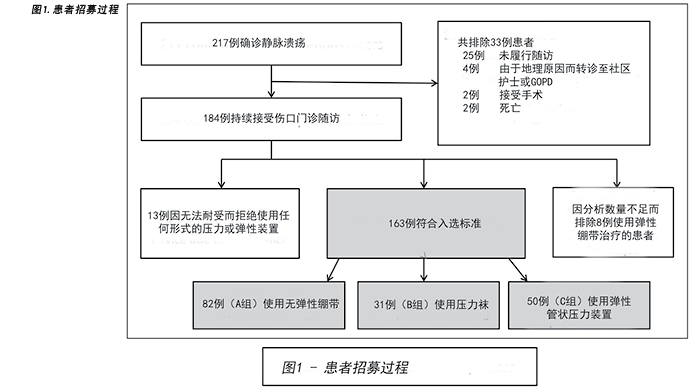

This is a retrospective design to perform a 6-year review (2011–2016) of all patients with venous ulcers who have undergone application of compression therapies in the clinic. A total of 217 patients were confirmed to have venous ulcers during the study period. Of these, 25 patients defaulted at follow-up, four were referred to community nurses or to a general out-patient clinic due to geographical reasons, two had operations performed, two passed away, and 13 patients refused any sort of compression or elastic device due to intolerance. Since the aim of our study is to review the effectiveness of compression therapies employed in our wound care nurse clinic, these patients were therefore excluded from our study, leaving an effective sample of 171. Of these, 82 were treated with inelastic bandages, eight with elastic bandages, 31 with compression stockings and 50 with elastic tubular compression devices. Due to insufficient number of patients treated with elastic bandages for data analysis (eight patients), this was excluded so the valid sample of this study was 163 (Figure 1). For patients with multiple ulcers over the lower limb, only the largest wound was included in this study. These 163 were then divided into three further groups.

Group A consisted of patients who were treated with two layers of inelastic compression bandages (Pütter-Verband, Hartmann). The bandages used were 15cm wide and either 5cm or 10cm long – according to limb circumference – with 100% stretch. The patients’ affected limbs were wrapped with a tubular cotton gauze (Stulpa, Hartmann) without tension. The first layer of inelastic bandages was applied in a spiral motion with a 50% overlap in a clockwise direction with the patient in the recumbent or sitting position and the foot in dorsal flexion. The second layer was applied in the same method but in an anti-clockwise direction, creating an average total pressure of around 20–30mmHg over the two layers. A pressure transducer (Kikuhime small probe, MediTrade) was used to measure the pressure on the medial aspect at the ankle. Pressure was measured during the first application of compression bandages and then irregularly, such as when lower limb oedema was obviously reduced or there was deterioration in wound condition. The bandaging system was worn day and night and, normally, the wound dressing, together with the bandages, would be changed twice weekly. The bandages were washed by patients with water and soap and then reused. The bandages were renewed every 3–6 months or when damaged.

Group B consisted of patients who could not tolerate compression bandages, so class 2 compression stockings providing medium support (23–32mmHg) (Venosan 6002, Swisslastic Ag St. Gallen) were applied. The stocking size was determined for each patient according to the circumference of the leg as measured at the ankle and at the largest part of the calf; small, medium, large and extra-large sizes were available. The patients were taught about the application and removal of the stockings once soiled. The stockings were washed by the patients and were renewed every 3 months or when damaged.

Group C consisted of patients who were unable to tolerate neither compression bandages nor compression stockings; they were treated with elastic tubular compression devices knitted in tubular form (Lastogrip, Hartmann) to control lower limb oedema. The size was determined for each patient according to the circumference of the leg measured at the largest part of the calf. The common sizes used were C (6.75cm in width), D (8cm in width) and E (8.5cm in width), with pressure varying from 10–15mmHg. Normally, one layer of elastic tubular compression device would be applied for wounds ≤2cm2, with pressure around 10mmHg. For wounds >2cm2, two layers were applied, with pressure around 12–15mmHg. Patients were taught about the application and removal of the tubular compression device once soiled. The tubular compression devices were washed by patients and were renewed every 2 months or when damaged.

Statistical analysis

All demographic data, patients’ general assessment, wound assessment, wound treatment protocol, types of compression therapy and follow-up frequencies were obtained through the electronic records (clinical management system) of the study hospital. The search period was from the start of treatment (Week 0) up to 24 weeks. Healing rates at 24 weeks were calculated for Group A, Group B and Group C by using Kaplan–Meier survival analyses. Specific risk factors for ulcer healing – such as age, gender, ulcer location – were assessed using the Cox regression proportional hazards model. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. All analyses were performed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) advanced statistical software (v. 10.0 statistical package).

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the study hospital. All patients were under the same treatment team which comprised of six nurses who had completed a recognised wound care course and were trained in compression therapies.

Results

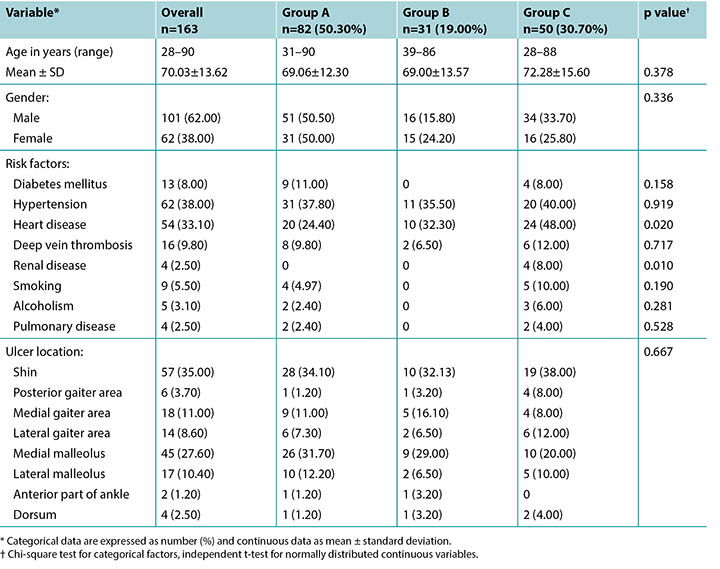

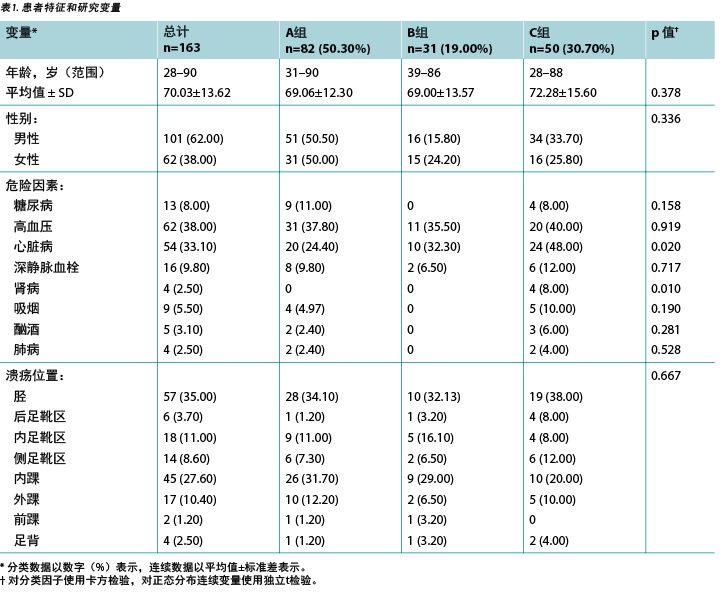

A total of 163 patients with CVI met inclusion criteria in this study; 82 were treated with compression bandages (Group A), 31 were treated with compression stockings (Group B) and 50 were treated with elastic tubular compression devices (Group C). Patients’ characteristics, risk factors and ulcer locations are shown in Table 1, with categorical data expressed as number (%). There are no significant differences in gender nor ulcer locations between the groups. In risk factors and co-mortalities, there was also no significant difference except in heart and renal disease (p=0.020, p=0.010 respectively).

Table 1. Patient characteristics and study variables.

Overall wound healing

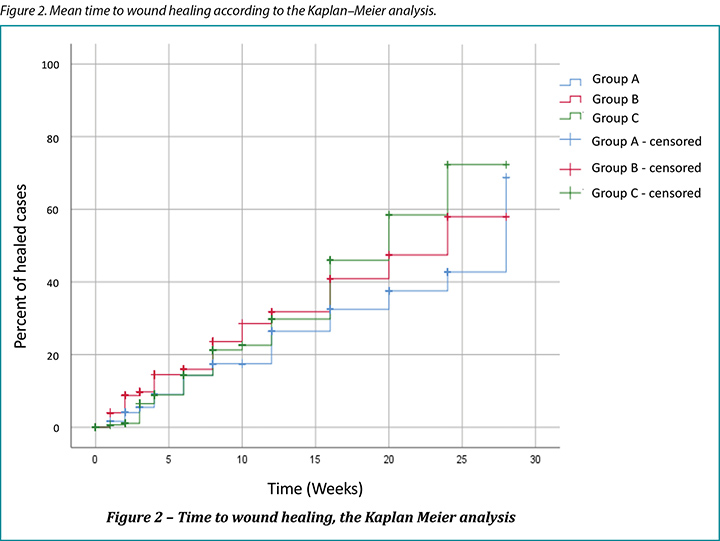

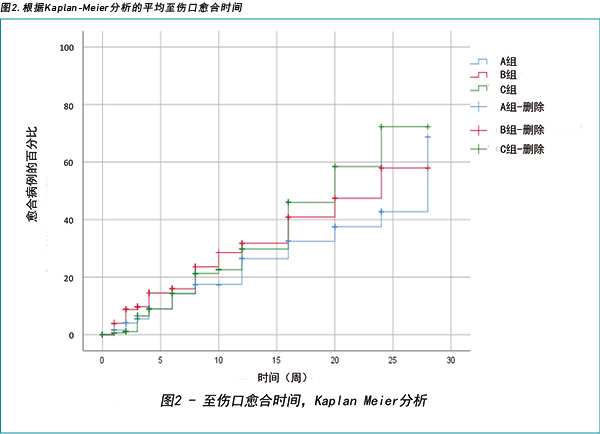

A total of 152 wounds healed within 24 weeks; an overall healing rate of 93.3%. By Kaplan–Meier survival analyses, the healing rates were 90.2% for Group A, 93.5% for Group B, and 98% for Group C at 24 weeks respectively. The mean healing time in Group A was 10 weeks, 8 weeks in Group B and 9 weeks in Group C (Figure 2).

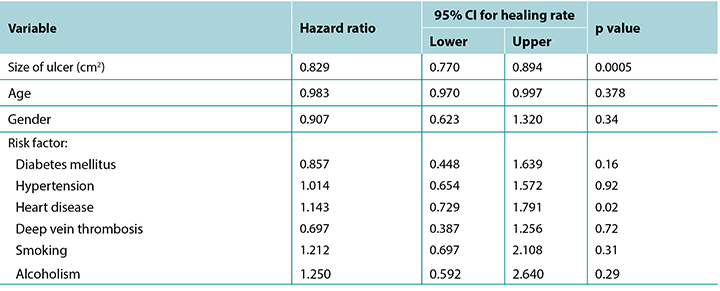

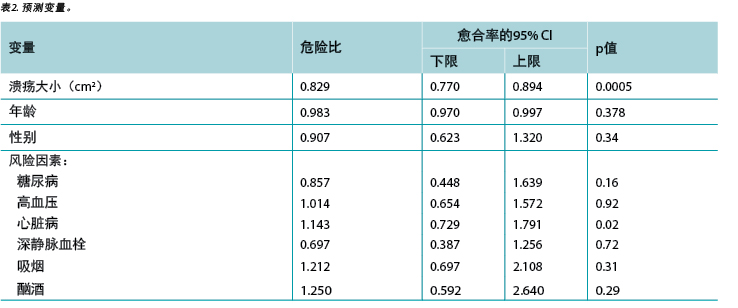

Cox regression identified that different ulcer sizes were independent predictors of ulcer healing. Age, gender and risk factors were not associated with 24-week healing status except heart disease (Table 2).

Table 2. Predictor variables.

Healing rate in regard to wound size

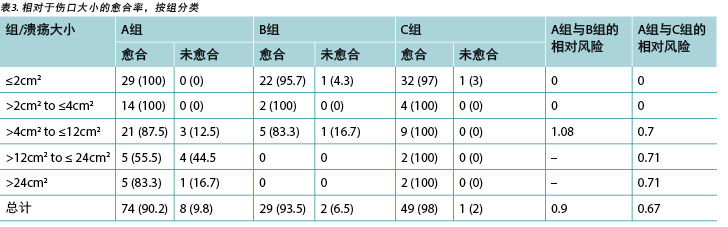

Table 3 shows the healing rate in regard to wound size of the three groups, with categorical data expressed as number (%). In Group A, all wounds ≤4cm2 healed. However, for wounds with an area of >12cm2 to ≤24cm2, Group A had the least healing rate (55.5%). In Group B, the healing rate of wounds ≤4cm2 was satisfactory (over 95%), but only obtained a 83% healing rate for wounds >4cm2 to ≤12cm2. There was no wound >12cm2 in Group B. Group C achieved the overall highest wound healing rate (98%), with a 100% healing rate for wounds with an area from >2cm2 to >24cm2. Overall, for wounds ≤4cm2, a 98% healing rate was achieved within 24 weeks (Table 3).

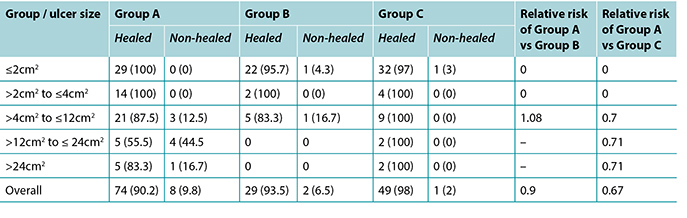

Table 3. Healing rate by group in regard to wound size.

In view of the various wound sizes between the three groups, there was relatively less difference in wound healing rates among groups – relative risk (RR)<1. For ulcers sized >4cm2 to ≤12cm2, the difference in the wound healing rate between using compression bandages rather than compression stockings was found to be only 0.8% (RR=1.08).

Discussion

The literature shows that people over 60 years old are particularly at risk for venous ulcers and around 2% of them are >80 years old24,25. This was reflected in our study population – the mean age was 70.03±13.62, with 24.5% over 80 years old. Our study also showed male patients accounted for 62% of our study population; this revealed a difference from other literature which showed women tended to develop venous ulcers more than men26. However, it may require further studies on the possibility of risk factors such as occupation or mobility level between genders.

Some research indicates the average healing time for venous ulcers was 24 weeks, with about a 45–70% healing rate in specialist clinics27,28. Our study showed that 93.3% of wounds healed within 24 weeks. The other related factors – such as dressing material used and frequency of wound dressing – were also investigated; however, there was no significant difference relating to the healing rate. The result reflected that the treatment regimen in our study population could meet international standards.

The literature also shows compression therapy heals more venous leg ulcers than not using compression therapy; however, there is insufficient evidence on the most effective degree of compression required to achieve ulcer healing13,26,29. A study performed by Milic et al.29 suggests compression systems should be individually determined for patients according to their calf circumference. However, international consensus supports the optimum therapeutic effects of compression to be around 35–50mmHg of pressure at the ankle13,30. In our study population, the pressure applied was lower than the recommendations, with an average pressure of 20–30mmHg in Group A, 23–32mmHg in Group B and 10–15mmHg in Group C. Although we did not measure the sub-bandage pressure of different groups regularly, and cannot compare the pressure difference between these three groups during each visit to our wound clinic, the healing rate of elastic tubular compression devices is similar to compression bandages and stockings (Table 3).

However, the findings of our study differed from those in other studies. It is understood that there are many factors which affect the effectiveness of pressure, such as the skill and technique of the clinician, the stretch of the bandages applied, and the number of times bandages or stockings are washed since this will decrease the elasticity of the material13,31. Moreover, the effectiveness of various layers of elastic tubular compression devices is still limited. Therefore, it is difficult to accurately evaluate the effectiveness of these three groups of therapy. Further investigation to compare one to two layers of elastic tubular compression device with compression bandages and stockings is therefore suggested.

Furthermore, it should be noted that compression bandages tend to be bulky, require skilled application by trained staff, and may also induce footwear and mobility problems for some patients31. In addition, because of humid and hot weather during spring and summer in Hong Kong, some of our patients cannot tolerate the bandaging system and prefer to change to other compression therapies. Compression stockings are less operator-dependent than bandages32. Patients can be taught about application and can change wound dressings themselves. However, elastic tubular compression devices are more economical and are more easily applied by the patients or their carers33. Moreover, these achieved a similar healing rate as the other compression therapies in this review. Taking into account the results from our study, and considering both economic factors and patients’ convenience, elastic tubular compression devices may be more suitable for our group of patients. However, apart from wound healing and patients’ convenience, clinicians should also consider other benefits and disadvantages when selecting the appropriate therapy for patients.

For example, lifestyle modification, calf muscle exercise and lower limb elevation are essential elements in venous ulcer healing. The literature reveals that exercise can improve calf muscle strength, mobility can improve calf muscle function, and leg elevation can promote changes in microcirculation and decrease lower limb oedema17,32. Although there is still no high level evidence which indicates their superior effect in venous ulcer wound healing, these are still recommended by various experts and in international guidelines17,32. In this review, our records did not detail patients’ compliance on calf muscle exercise nor leg elevation, hence the analysis could not be performed.

Limitations

In this review, patients who refused compression therapies and defaulted on follow-up were excluded. It would have been more appropriate if these patients’ wounds had been evaluated and compared to the healing rates with other compression therapies. In addition, it was found the majority of the large ulcers (15 patients) were treated by compression bandages (Group A); there were no large ulcers in Group B and only four in Group C. As such, the comparisons in healing rates may be affected by this factor.

Since this is a retrospective study to review our records, some information such as occupation, patients’ calf circumference, body mass index, pain score, history of ulcers and recurrence rates are insufficient. In our clinic, there is also no guideline on the frequency of sub-bandage pressure measurement for these patients. Additionally, patients’ compliance with compression therapy is not recorded in detail. This is an important issue since compression bandages may induce mobility problems for some patients. It may also affect their compliance with the therapy, and therefore negatively alter the outcome. Moreover, our study was only implemented in the wound care clinic of a university hospital, thus findings in this study cannot be generalised in other wound clinics in Hong Kong. Further multi-centre studies on this topic are therefore warranted.

Conclusion

Compression therapy is the gold standard in venous ulcer wound healing. As a general rule, high compression can achieve better healing than low compression, and some pressure is more beneficial than no pressure. In this review, although the sub-bandage pressure difference is not regularly measured between these three groups of patients, their wound healing rate is comparable. However, lifestyle modification, calf muscle exercise, lower limbs elevation and compliance with compression therapy are fundamental elements in venous ulcer healing. Clinicians should be reminded that patient education is also a significant issue for this group of patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

回顾性综述:香港某伤口护理中心的压迫疗法在下肢静脉性溃疡愈合中的有效性

Michelle Lee, Ka Wai Wong and Ka Kay Chan

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.39.4.24-31

摘要

前言 静脉溃疡是慢性静脉功能不全(CVI)的严重临床后果之一。成功管理的基础是压迫疗法,例如压力绷带、压力袜和/或弹性管状压力装置。

目的 本研究旨在对香港某伤口护理护士门诊中压迫疗法的有效性进行回顾性综述。

方法 本研究涵盖在门诊中显示出CVI体征和症状且踝臂指数>0.8,或者经 Duplex 扫描确诊CVI的下肢溃疡患者(图1)。检索期为治疗开始(第0周)至第24周。

结果 采用对数秩检验比较了至愈合时间;24周内有152处伤口愈合,总愈合率为93.3%。共有90.2%的伤口使用压力绷带愈合,93.5%的伤口使用压力袜愈合,98%的伤口使用弹性管状压力装置愈合。平均愈合时间分别为10周、8周和9周。

讨论 鉴于三组之间的伤口大小不同,三组的总体伤口愈合率差异相对较小 - 相对风险(RR)<1。对于>4 cm2且 ≤12 cm2的溃疡,使用压力绷带和压力袜的伤口愈合率差异仅为0.8%(RR=1.08)。

结论 综合考虑本研究的结果以及经济因素和患者的便利性,弹性管状压力装置可能更适合我们的患者组。

前言

静脉溃疡是临床实践中最常见的伤口问题之一,并且是慢性静脉功能不全(CVI)的严重临床后果之一。在美国,据估计每年约有50万人至60万人在伤口中心接受静脉溃疡治疗1。在澳大利亚,一项研究表明,社区护士大约花费50%的时间来治疗静脉溃疡2。尽管香港静脉溃疡患者的患病率和发病率尚无充分记录,但一项在特定地区(观塘)社区护理服务中进行的研究发现,每月约有200例患者接受社区护士的伤口护理,其中11%为下肢溃疡3。

静脉溃疡的治疗需要昂贵的伤口敷料材料、压迫治疗、药物治疗、清创治疗和手术介入治疗4。据估计,在2002年,澳大利亚的国家卫生系统每个月为每例患者的静脉溃疡管理所支出的费用约为114澳元4。在美国,Ma等人5在6个月内对84例患者进行了队列研究,发现静脉溃疡的平均治疗总费用为15732美元。该证据表明静脉溃疡给医疗卫生系统带来了巨大的经济负担。

静脉溃疡管理不仅给医疗卫生系统和护士带来了沉重负担,而且对患者的生理和心理社会健康也产生了不利影响,并且直接影响了老年患者的生活质量6,7。在生理上,疼痛和行动不便会阻碍他们的日常生活8。在心理上,据报告,静脉溃疡也可能会导致各种问题,例如无助感、丧失自尊,以及压力和焦虑情绪增加6,9。上述所有负面影响可能会阻碍初始炎症应答,扰乱神经内分泌免疫平衡,最终影响伤口愈合10,11。

文献综述

成功进行静脉溃疡管理的基础是压迫疗法。人们认为,对四肢进行压迫疗法可诱导组织液的再吸收,促进静脉回流,将血液量从外周循环转移到中心循环,降低静脉压力并防止静脉淤滞12-15。

该疗法包括压力绷带系统或弹性压力袜。研究表明,使用短展(无弹性)压力绷带的平均愈合时间约为12-24周,而使用长展(有弹性)压力绷带患者的伤口有50%在6个月内愈合16-17。各种研究也证明了压力袜的有效性。Dolibog等人18进行的一项研究显示,在2个月的时间内使用压力为30-40 mmHg的压力袜后,愈合率为56.7%。在比较两层压力袜(35-40 mmHg)和四层压力绷带(40 mmHg)的溃疡愈合时间时,Ashby19观察到两者的至溃疡愈合中位时间相似,分别为99天(愈合率为70.9%)和98天(愈合率为70.4%)。另外,由Amsler、Willenberg和Blättler20进行的一项荟萃分析报告称,使用压力袜(35-56 mmHg)的愈合率高于压力绷带(27- 49 mmHg)(62.7%与46.6%;p<0.00001),并且压力袜的平均至愈合时间比压力绷带缩短了3周(p=0.0002)。 Mauck等人21还对静脉溃疡愈合的加压方式进行了比较性系统评价和荟萃分析。该评价表明,压力袜和压力绷带对溃疡愈合的治疗效果并无总体差异,至溃疡愈合时间也无差异。

弹性管状压力装置主要用于帮助减轻下肢水肿。2003年,Bale和Harding22使用三层梯度压力绷带Tubigrip(Mölnlycke)对静脉溃疡患者进行了一项研究,发现12周内的愈合率达到50%。另外,Weller23进行了一项随机对照试验,对使用无弹性压力绷带和三层梯度压力管状装置的伤口愈合率进行了研究。尽管无弹性绷带组的平均压力始终比管状装置组高出至少13 mmHg,但结果表明,管状装置组在12周内的愈合率更高(74%与46%;p=0.05)。但是,有关该领域的进一步研究有限。

方法

研究环境

本研究中,医院的伤口护理护士门诊旨在为急性和慢性伤口患者提供连续性护理。对于患有静脉溃疡的患者,我们的标准治疗方案是使用肥皂和自来水清洗下肢,然后使用低变应原性乳霜滋润皮肤。用于高度渗出伤口的标准伤口敷料包括Hydrofiber(ConvaTec)、Gelfiber((Durafiber)Smith&Nephew)或泡沫敷料。藻酸盐敷料通常用于适度渗出伤口。对于感染或严重定植伤口,使用高渗氯化钠敷料或Hydrofiber、Gelfiber或含银泡沫敷料。

根据国际指南,大多数患者均接受压迫疗法,例如弹性(Setopress, Mölnlycke)或无弹性绷带(Pütter-Verband, Hartmann)、压力袜(Venosan 6002, Swisslastic Ag St. Gallen)或弹性管状压力装置(Lastogrip, Hartmann),根据患者的职业、活动、年龄和依从性而定。所有在伤口门诊工作的护理人员都接受过绷带敷贴的培训。但是,由于门诊中某些患者无法耐受压力绷带,因此通常使用2级压力袜来提供中等支撑(23-32 mmHg)。对于无法耐受压力绷带或压力袜的患者,建议他们使用弹性管状压力装置来控制下肢水肿。使用压力传感器(Kikuhime小探头,MediTrade)测量脚踝内侧的压力。正常的敷料更换频率是每周两次,除非因渗出液过多而需要更频繁地更换。

目的

本研究旨在对香港某大学医院的伤口护理护士门诊中采用的压迫疗法的有效性进行回顾性综述。

纳入/排除标准

研究纳入存在CVI体征和症状且踝臂指数> 0.8,或者经Duplex扫描确诊CVI的下肢溃疡患者。

如果患者符合纳入标准但拒绝使用任何形式的压力或弹性装置,则被排除在外。如果患者近期存在禁忌使用压迫疗法的情况,例如深静脉血栓或者心脏或呼吸系统问题,则也被排除在外。此外,本研究排除了混合性溃疡或非静脉疾病导致溃疡的患者。

患者招募

本研究采用回顾性设计,对6年期间(2011-2016年)在门诊接受过压迫疗法的所有静脉溃疡患者进行研究。在研究期间,总共217例患者确诊静脉溃疡。其中,25例患者未履行随访,4例患者由于地理原因而转诊至社区护士或普通门诊,2例患者接受手术,2例患者死亡,13例患者因无法耐受而拒绝使用任何形式的压力或弹性装置。由于本研究旨在回顾伤口护理护士门诊中采用的压迫疗法的有效性,因此将上述患者排除在研究之外,剩下的有效样本为171例。其中,82例使用无弹性绷带治疗,8例使用弹性绷带治疗,31例使用压力袜治疗,50例使用弹性管状压力装置治疗。由于使用弹性绷带治疗的患者数量不足(8例患者),因此将其排除在外,本研究的有效样本为163例(图1)。对于下肢多处溃疡的患者,本研究仅纳入最大的伤口。上述163例患者随后被分为3组。

A组由使用两层无弹性压力绷带(Pütter-Verband, Hartmann)进行治疗的患者组成。使用的绷带宽15cm,长5cm或10cm(根据肢体周长而定),伸展率100%。患者的患肢用无张力的管状棉纱布(Stulpa, Hartmann)包裹。第一层无弹性绷带以螺旋形式沿顺时针方向包扎,每圈有50%的重叠,患者处于斜卧位或坐姿,足背屈。第二层以相同形式但沿逆时针方向包扎,在两层绷带上产生约20-30 mmHg的平均总压力。使用压力传感器(Kikuhime小探头,MediTrade)测量脚踝内侧的压力。在第一次使用压力绷带期间测量一次压力,然后不定期地测量压力,例如当下肢水肿明显减轻或伤口状况恶化时。患者全天佩戴绷带系统,通常情况下伤口敷料和绷带每周更换两次。患者自行用清水和肥皂清洗绷带,然后重复使用。每3-6个月或损坏时更换新绷带。

B组由无法耐受压力绷带的患者组成,因此使用了提供中等支撑(23-32 mmHg)的2级压力袜(Venosan 6002, Swisslastic Ag St. Gallen)。根据在脚踝和小腿周长最大处测量的腿围确定每例患者的压力袜尺寸;提供小、中、大和超大尺寸。告知患者如何穿戴压力袜,以及弄脏后应立即脱下。患者自行清洗压力袜,每3个月或损坏时更换新压力袜。

C组由既无法耐受压力绷带也无法耐受压力袜的患者组成;他们使用管状编织的弹性管状压力装置(Lastogrip, Hartmann)进行治疗,以控制下肢水肿。根据在小腿周长最大处测量的腿围确定每个患者使用的尺寸。常用尺寸为C(宽6.75 cm)、D(宽8 cm)和E(宽8.5 cm),压力范围为10-15 mmHg。通常,对于≤2 cm2的伤口,应使用1层弹性管状压力装置,压力约为10 mmHg。对于>2 cm2的伤口,应施加2层,压力约为12-15 mmHg。告知患者如何穿戴管状压力装置,以及弄脏后应立即脱下。患者自行清洗管状压力装置,每2个月或损坏时更换新管状压力装置。

统计分析

所有人口统计学数据、患者的总体评估、伤口评估、伤口治疗方案、压迫疗法的类型和随访频率均通过研究医院的电子记录(临床管理系统)获得。检索期为治疗开始(第0周)至第24周。通过Kaplan-Meier生存分析,计算A组、B组和C组在第24周时的愈合率。使用Cox比例风险回归模型,评估溃疡愈合的特定风险因素,例如年龄、性别、溃疡位置。计算危险比和95%置信区间(CI)。所有分析均使用社会科学统计软件包(SPSS)的先进统计软件(v. 10.0统计软件包)进行。

伦理事宜

本研究得到了研究医院机构审查委员会的批准。所有患者均接受同一个治疗小组的治疗,该小组由六名护士组成,其完成了公认的伤口护理课程并接受了压迫疗法的培训。

结果

共有163例CVI患者符合本研究的纳入标准 ;其中82例使用压力绷带进行治疗(A组),31例使用压力袜进行治疗(B组),50例使用弹性管状压力装置进行治疗(C组)。患者的特征、风险因素和溃疡位置列于表1 ,分类数据以数字(%)表示。各组之间的性别和溃疡位置均无显著差异。除了心脏病和肾病外,各组之间的风险因素和致死率也无显著差异(分别为p=0.020,p=0.010)。

整体伤口愈合

在24周内共有152处伤口愈合;总体愈合率为93.3%。通过Kaplan-Meier生存分析,在第24周时,A组的愈合率为90.2%, B组为93.5%,C组为98%。A组的平均愈合时间为10周,B组为8周,C组为9周(图2)。

根据Cox回归确定,不同的溃疡大小是溃疡愈合的独立预测因子。除心脏病外,年龄、性别和风险因素与24周的愈合状态无关(表2)。

相对于伤口大小的愈合率

表3显示了相对于伤口大小的三组愈合率,分类数据以数字(%)表示。在A组中,所有≤4 cm2的伤口均愈合。但是,对于>12 cm2且≤24 cm2的伤口,A组的愈合率最低(55.5%)。在B组中,≤4 cm2的伤口愈合率令人满意(超过95%),但是对于>4 cm2且≤12 cm2的伤口,愈合率仅为83%。B组中没有>12 cm2的伤口。C组的伤口愈合率整体最高(98%),其中>2 cm2且>24 cm2的伤口愈合率达到100%。总体而言,对于≤4 cm2的伤口,24周内的愈合率达到98%(表3)。

鉴于三组之间的伤口大小不同,三组的伤口愈合率差异相对较小 - 相对风险(RR)<1。对于>4 cm2且≤12 cm2的溃疡, 使用压力绷带和压力袜的伤口愈合率差异仅为0.8 %(RR = 1.08)。

讨论

文献显示,60岁以上的人特别容易发生静脉溃疡,其中约2%的人> 80岁24,25。这在本研究的人群中有所反映,其平均年龄为70.03±13.62岁,其中24.5%的人为80岁以上。本研究表明,男性患者占研究人群的62%;这揭示了与其他文献的不同之处,后者表明女性比男性更容易发生静脉溃疡26。但是,可能需要进一步研究风险因素的可能性,例如不同性别的职业或活动程度。

一些研究表明静脉溃疡的平均愈合时间为24周,在专科门诊中的愈合率约为45-70%27,28。本研究表明,93.3%的伤口在24周内愈合。还研究了其他相关因素,例如使用的敷料材料和伤口敷料的更换频率;但是,愈合率并无显著差异。结果表明,本研究人群的治疗方案可以达到国际标准。

文献还显示,与不使用压迫疗法相比,压迫疗法可以治愈更多的下肢静脉性溃疡;然而,尚无足够的证据证明为实现溃疡愈合所需的最有效的压迫程度13,26,29。Milic等人29进行的一项研究建议,应根据每位患者的小腿周长为其单独确定压迫系统。然而,国际共识支持的最佳压迫治疗效果是在踝部承受约35-50 mmHg的压力13,30。在本研究人群中,施加的压力低于建议值,A组的平均压力为20-30 mmHg,B组为23 - 32mmHg,C组为10-15 mmHg。尽管没有定期测量不同组别中的绷带下压力,并且无法在每次伤口门诊就诊时比较三组之间的压力差异,但由结果可知弹性管状压力装置的愈合率与压力绷带和压力袜类似(表3)。

但是,本研究的结果不同于其他研究。这一点可以理解,因为许多因素都会影响压力的有效性,例如临床医师的技能和技术、所用绷带的伸展程度,以及绷带或压力袜的洗涤次数(可能降低材料的弹性)13,31。而且,弹性管状压力装置中各层的有效性仍然受到限制。因此,难以准确评价三组疗法的有效性。因此,建议进行进一步研究,将1至2层弹性管状压力装置与压力绷带和压力袜进行比较。

此外,应注意的是,压缩绷带往往很笨重,需要训练有素的工作人员才能熟练使用,并且还可能在某些患者中引发穿鞋和活动性问题31。此外,由于香港春季和夏季的潮湿炎热天气,有些患者无法耐受绷带系统,因此倾向于改用其他压迫疗法。压力袜对操作者的依赖性小于绷带32。可告知患者如何穿戴,并且患者可以自行更换伤口敷料。然而,弹性管状压力装置更经济,并且更易于由患者或其护理者使用33。而且,在本回顾性综述中,其愈合率与其他压迫疗法相似。综合考虑本研究的结果以及经济因素和患者的便利性,弹性管状压力装置可能更适合我们的患者组。但是,除了伤口愈合和患者便利之外,临床医生在为患者选择合适的治疗方法时还应考虑其他利弊。

例如,改变生活方式、锻炼小腿肌肉和抬高下肢是静脉溃疡愈合的基本要素。文献表明,运动可以增强小腿肌肉的力量,活动可以改善小腿肌肉的功能,而抬高下肢可以促进微循环的改变并减少下肢水肿17,32。尽管尚无高水平的证据表明其在静脉溃疡伤口愈合中具有优越的作用,但是仍然获得了各类专家和国际指南的推荐17,32。在本回顾性综述中,我们没有详细记录患者对锻炼小腿肌肉或抬高下肢的依从性,因此无法进行分析。

局限性

在本回顾性综述中,排除了拒绝接受压迫疗法和未履行随访的患者。如果对此类患者的伤口进行评价,并与其他压迫疗法的愈合率进行比较,则研究会更加完善。此外,研究发现大多数大面积溃疡(15例患者)均采用压力绷带治疗(A组);此外,B组中没有大面积溃疡患者,C组中只有4例。因此,愈合率的比较可能受此因素影响。

由于本研究为回顾性研究,旨在回顾相关记录,因此某些信息(例如职业、患者的小腿周长、体质指数、疼痛评分、溃疡病史和复发率)不足。门诊中也没有针对此类患者的绷带下压力测量频率的指南。此外,本研究没有详细记录患者对压迫疗法的依从性。这是一个重要的问题,因为压力绷带可能会在某些患者中引发活动性问题。它还可能影响患者对治疗的依从性,因此会对结果产生负面影响。此外,本研究仅在某大学医院的伤口护理门诊进行,因此研究结果无法外推至香港其他伤口门诊。因此,有必要就该主题开展进一步的多中心研究。

结论

压迫疗法是静脉溃疡伤口愈合的金标准。通常,高压迫的愈合效果优于低压迫,有压力比无压力更有益。在本综述中,尽管没有定期测量三组患者之间的绷带下压力差异,但其伤口愈合率具有可比性。但是,改变生活方式、锻炼小腿肌肉、抬高下肢和依从压迫疗法是静脉溃疡愈合的基本要素。应当提醒临床医生,对于此类患者,患者教育也是一个重要问题。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Michelle Lee*

7H, Block 2, Academic Terrace, 101 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong

Email leewkmichelle@gmail.com

Ka Wai Wong

Ka Kay Chan

* Corresponding author

References

- Abbade LP, Lastoria S. Venous ulcer: epidemiology, physiopathology, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol 2005;44:449–456.

- Carville K, Smith J. A report on the effectiveness of comprehensive wound assessment and documentation in the community. Prim Intent 2004;12(1):41–4.

- Wong I. Measuring the incidence of lower limb ulceration in the Chinese population in Hong Kong. J Wound Care 2002;11:377–9.

- Smith E, McGuiness W. Managing venous leg ulcers in the community: personal financial cost to sufferers. Wound Pract Res 2010;18(3):9134–9139.

- Ma H, O’Donnell TF, Rosen NA, Iafrati MD. The real cost of treating venous ulcers in a contemporary vascular practice. J Vasc Surg 2014;2:355–361.

- Wong IKY, Lee DTF. Chronic wounds: why some heal and others don’t? Psychosocial determinants of wound healing in older people. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol 2008;16:71–76.

- So WKW, Wong IKY, Lee DTF, Thompson DR, Lau YW, Chao DVK, et al. Effect of compression bandaging on wound healing and psychosocial outcomes in older people with venous ulcers: a randomized control trial. Hong Kong Med J 2014;20(Suppl 7):S40–1.

- Wong I, Lee D, Thompson D. Lower limb ulcerations in older people in Hong Kong. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:118–9.

- Cole-King A, Harding KG. Psychological factors and delayed healing in chronic wounds. Psychosom Med 2001;63:216–20.

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, Malarke WB, Mercado AM, Glaser R. Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet 1995;346:1194–6.

- Augustin M, Maier K. Psychosomatic aspects of chronic wounds. Dermatol Psychosomatic 2003;4:5–13.

- Nelson EA, Adderley U. Venous ulcers. BMJ Clin Evid 2016;pii:1902.

- AWMA/NZWCS. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guideline for prevention and management of venous leg ulcers. Perth (Australia): Cambridge Publishing; 2011.

- Moffatt C, Martin R, Smithdale R. Leg ulcer management. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

- Kelechi T, Johnson JJ. Guideline for management of wounds in patients with lower extremity venous disease: an executive summary of the WOCN lower extremity venous disease evidence based guideline. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;39(6):598–606.

- Nelson EA, Iglesias CP, Cullum N, Torgerson DJ, VenUS I collaborators. Randomized clinical trial of four-layer and short-stretch compression bandages for venous leg ulcers [VenUS 1]. Br J Surg 2004;91(10):1292–1299.

- Franks PJ, Moody M, Moffatt CJ, et al. Randomized trial of cohesive short-stretch versus four-layer bandaging in the management of venous ulceration. Wound Repair Regen 2004;12(2):157–162.

- Dolibog P, Franek A, Taradaj J, Dolibog P, Blaszczak E, Polak A, et al. A comparative clinical study on five types of compression therapy in patients with venous leg ulcers. Int J Med Sci [Internet]. 2013;11(1):34–43. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7548.

- Ashby RL, Gabe R, Ali S, Adderley U, Bland JM, Cullum NA, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of compression hosiery versus compression bandages in treatment of venous leg ulcers (venous leg ulcer study IV, VenUS IV): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet [Internet]. 2014;383(9920):871–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62368-5

- Amsler F, Willenberg T, Blättler W. In search of optimal compression therapy for venous leg ulcers: a meta-analysis of studies comparing divers bandages with specifically designed stockings. J Vasc Surg 2009;50(3):668–674.

- Mauck KF, Asi N, Elraiyah TA, Undavalli C, Nabhan M, Altayar O, et al. Comparative systematic review and meta-analysis of compression modalities for the promotion of venous ulcer healing and reducing ulcer recurrence. J Vasc Surg 2014;60:71S–90S.

- Bale S, Harding KG. Managing patients unable to tolerate therapeutic compression. Br J Nurs 2003;12(19 Suppl):S4–13.

- Weller CD, Evans SM, Staples M, Aldons P, McNeil J. Randomized clinical trial of three-layer tubular bandaging system for venous leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen [Internet]. 2012;20(6):822–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00839.x

- New Zealand Ministry of Health. Population ageing and health expenditure: New Zealand 2002–2051. Wellington (New Zealand): Ministry of Health; 2004.

- Petherick ES, Cullum NA, Pickett KE. Investigation of the effect of deprivation on the burden and management of venous leg ulcers: a cohort study using the THIN database. PLoS One 2013;8(3):e58948.

- WOCN. Guideline for management of wounds in patients with lower-extremity venous disease. Glenview (USA): Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society; 2005.

- Chaby G, Senet P, Ganry O, et al. Prognostic factors associated with healing of venous leg ulcers: a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Br J Dermatol 2013;169(5):1106–13.

- Sauer K, Rothgang H, Glaeske G. BARMER GEK Heil- und Hilfsmittelreport [Internet]. Berlin (Germany): BARMER GEK; 2014 [cited 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: http://www.zes.uni-bremen.de/uploads/News/2014/140916_Heil_Hilf_Report_2014.pdf.

- Milic DJ, Zivic SS, Bogdanovic DC, et al. The influence of different sub-bandage pressure values on venous leg ulcers healing when treated with compression therapy. J Vasc Surg 2010;51(3): 655–661.

- O’Donnell TF, Passman MA, Marston WA, et al. Management of venous leg ulcers: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery® and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2014;60(2):3S–59S.

- Weller CD, Jolley D, McNeil J. Sub-bandage pressure difference of tubular form and short-stretch compression bandages: in-vivo randomized controlled trial. Wound Pract Res 2010;18(2):100–104.

- Latz CA, Brown KR, Bush RL. Compression therapies for chronic venous leg ulcers: interventions and adherence. Chronic Wound Care Manage Res 2015;2:11–21.

- Weller CD, Evans S, Reid C, Wolfe R, McNeil J. Protocol for a pilot randomized controlled clinical trial to compare the effectiveness of a graduated three layer straight tubular bandaging system when compared to a standard short stretch compression bandaging system in the management of people with venous ulceration: 3VSS2008. Trials 2010;11:26.