Volume 40 Number 1

Enhancing recovery: raising awareness of everyday struggles of patients with ostomies

Connie Johnson, Judy Kelly, Katrina Jones Heath, Ashley Palmisano, Lawrence Jordan III and Maureen Zielinski

Keywords quality of life, ostomy, ostomy patients, ostomy education, collaboration

For referencing Johnson C et al. Enhancing recovery: raising awareness of everyday struggles of patients with ostomies. WCET® Journal 2020;40(1):27-31

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.1.27-31

Abstract

Purpose Within our facility the number of surgical procedures resulting in ostomy formation is increasing. Inpatient ostomy care helps patients learn how to care for their ostomy and become as independent as possible to maintain a high quality of life (QoL) following surgery. But more needs to be done to assess patients’ QoL when they return home. This study was designed to support improvement in the QoL for patients living with ostomies post-discharge. It will assist in promoting patients’ full potential and optimal health within the community.

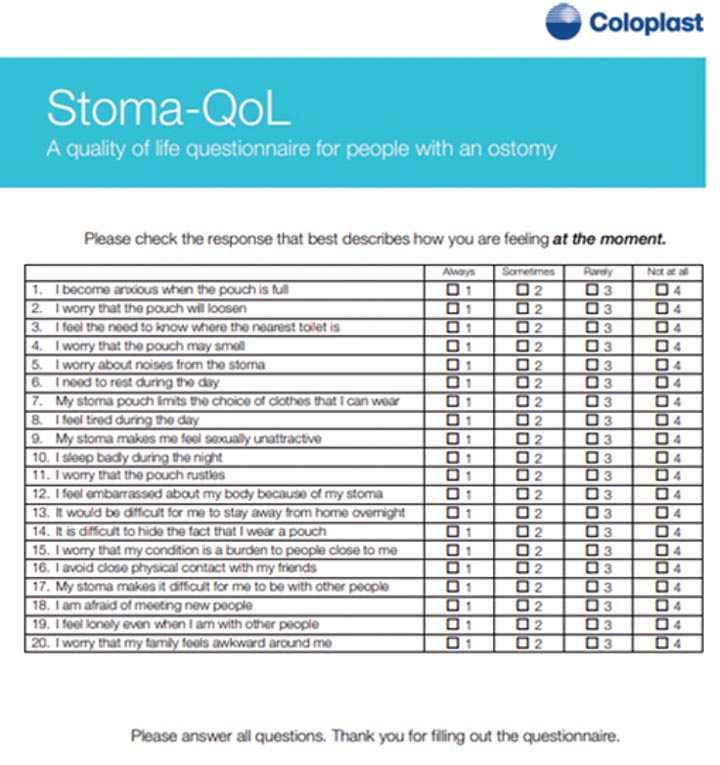

Method The Stoma-QoL Tool was used to evaluate patients’ perception of living with an ostomy at 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-discharge via a telephone survey. The Stoma-QoL Tool contained 20 closed questions to rate QoL. Ostomy education was provided using multiple written and visual aids.

Results There were 28 new ostomy patients who completed the surveys at the stipulated time periods. The highest score achieved in the Stoma-QoL Tool was used an indicator of QoL at each time period. An example of one patient demonstrated a change in score of 28 to 44 between 1 and 8 weeks. Body image and issues related to the ostomy appliance were the main concerns expressed.

Conclusion Quality of life can affect a patient’s well-being, not only physically but also emotionally and socially. Using an ostomy QoL survey, patients were able to quantify their QoL, allowing members of the research team to individualise patients’ care within the Princeton Healthcare System. (IRB Study: BN2332).

Introduction

Many ostomy patients who presented postoperatively to the emergency room in our facility to see the wound/ostomy nurse were found to be experiencing difficulties that were often emotional, not stoma nor appliance related management issues. Several of the new ostomy patients expressed general sadness about their situation; they felt frustrated with a lack of knowledge about the care of their stoma, adjustments to living with an ostomy, and perceived lack of control over their situation, and they were anxious about changes in their body image. In addition, and as a result of the large volume of calls received from ostomy patients weekly expressing similar concerns, the ostomy staff decided to look further into the quality of life (QoL) for ostomy patients.

Quality of life after ostomy surgery is a major factor in a person’s rehabilitative processes that impacts on their ability to accept changes to their health and physical status, manage their stoma, connect socially with family and friends, and re-integrate meaningfully with society, inclusive of returning to paid or voluntary work1,2.

Failure to adjust physically and psychosocially after ostomy surgery can have adverse short- or long-term consequences. Therefore, it is important to understand what factors contribute to people’s lack of confidence and/or ability to adjust to living with a stoma especially in the immediate postoperative period. There have been a number of tools designed to assess QoL after ostomy surgery, including the City of Hope Quality of Life Scale – Ostomy questionnaire, the Stoma Quality of Life Scale, and the Stoma Quality of Life Index3,4.

The Stoma-QoL Tool¹ was developed to measure QoL among people with a stoma (Table 1). The following concerns associated with having a stoma are itemised within the Tool: sleeping; intimate relations; relationships with family and close friends; concerns regarding relationships with people other than family and close friends; wearing an ostomy appliance; access to toilet facilities; body image; and self-worth. The questions asked in the Tool are reflective of those found to be most important in ostomy patients’ QoL1–5.

Table 1. The Stoma-QoL Tool

Wound/ostomy nurses at our facility provide inpatient education on ostomy care including the supply of an ostomy educational folder. Ostomy educational folders include written information on: all aspects of stoma care; the ostomy appliance and skin care accessories in use; purchasing of ostomy supplies; community resources; and matters related to body image and sexuality. Such education, combined with face to face specific counselling by wound/ostomy nurses, helps patients (and families) to properly care for their ostomy as independently as possible while encouraging patients to maintain a high QoL following ostomy surgery. Patients also receive Your Guide to Recovery after Ostomy Surgery which provides additional guidance6. During the course of a hospital stay for a new ostomy patient at our facility, they will be seen on average between 10–14 hours for tuition and counselling on how to manage their stoma.

Methods

Institutional Review Board: study approval

According to Section 5.05 in the Rules and Regulations of The Medical Staff of Princeton HealthCare System, staff are guided by “federal, state and institutional regulations, including all aspects of informed consent and patient protection”7 for the conduct of any research.

A facility-based Institutional Review Board (IRB) is a committee that applies all relevant regulations and the principles of research ethics by reviewing the methods proposed for research to ensure that they are ethical. The IRB board at our facility is comprised of a designated panel incorporating medical, nursing, quality assurance and legal representation for example, which approve or reject research studies and continue to monitor approved studies when it involves humans.

Research applications must be submitted prior to any study starting, and a formal meeting with the IRB is held to determine whether or not a research study should proceed. The IRB also protects the rights and welfare of humans participating as subjects in a research study. Potential risks to study participants are to be disclosed within an application to the IRB. Study researchers declared there were no risks – physical, confidential or legal – involved in this study8. It was noted that potential discomfort might be experienced by some study participants when asked to respond to questions that addressed intimate relations or relationships. Obtaining approval from the IRB panel took several months to complete. Study researchers were awarded IRB study approval #BN2332 and were given 1 year for data collection.

Interviewing patients was performed by an ostomy nurse (while inpatient), use of visual materials (ostomy folders/brochures, ostomy apron), and analysis of documents (Stoma-QoL Tool) was performed across the continuum of care, beginning in acute care. Patients in our community teaching hospital were identified through inpatient consult lists.

Research method and data collection

This study used a quantitative methodological approach. Quantitative research can be applied by patients assigning numbers to their answers using a validated survey tool. The Stoma-QoL5 Tool was chosen to measure QoL in this study as it was simple to execute. It was also deemed to assist in identifying QoL issues that facilitated better planning processes to improve QoL for patients living with ostomies. The instrument has 20 items, each of which were to be rated by study participants on a 4-point Likert scale9 using numbers ranging from 1 to 4 (Always, Sometimes, Rarely, and Not at all). The questions are closed end. The highest and lowest possible raw scores to be achieved are 80 (best QoL) and 20 (worst QoL) respectively3.

The Stoma-QoL Tool was administered over five time periods – before surgery, and then 1, 2, 4 and 8 weeks after surgery – by wound/ostomy nurses during scheduled interviews with consenting participants.

Over the 12-month study period new ostomy patients were approached to participate in the study whilst inpatients. Patients at the 8-week period of the study who had been discharged and who remained as study participants were surveyed in the home setting via a contact telephone call. Participants were asked to verbally rate their responses to the Stoma-QoL Tool using the Likert scale.

Patients considered for inclusion within the study were identified through inpatient consult lists.

Study interventions

Structured telephone interviews were conducted by wound/ostomy nurses of new ostomy patients in accordance with the above time periods prior to and after surgery using the Stoma-QoL Tool. The study used visual materials such as ostomy folders/brochures and an ostomy apron10 to educate new patients on the gastro-intestinal tract, type of surgical procedure to be formed, type of stoma to be created and how to care for their stomas. Data was analysed using simple descriptive statistics.

Results

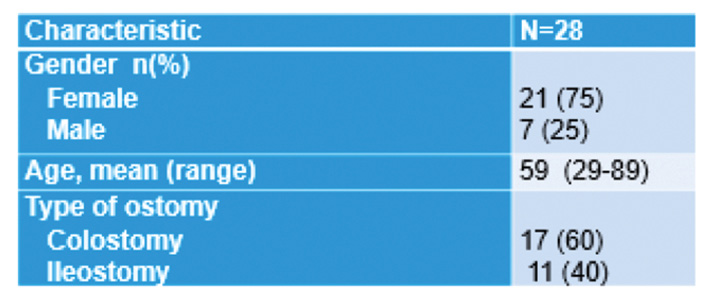

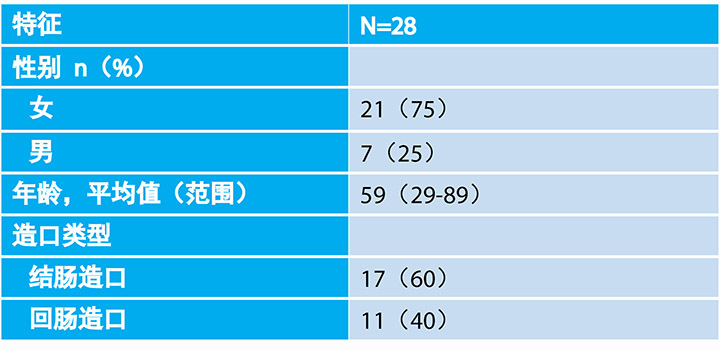

During the 12-month study period there were 102 new ostomy patients. Collectively, over 300 ostomy consults were undertaken during their periods of hospitalisation. Of the 102 new patients, 82 had permanent ostomies, 17 people had colostomies, and 11 had ileostomies. The mean age of patients was 65, and 75% were female and 25% were male (Table 2).

Table 2. Study demographics

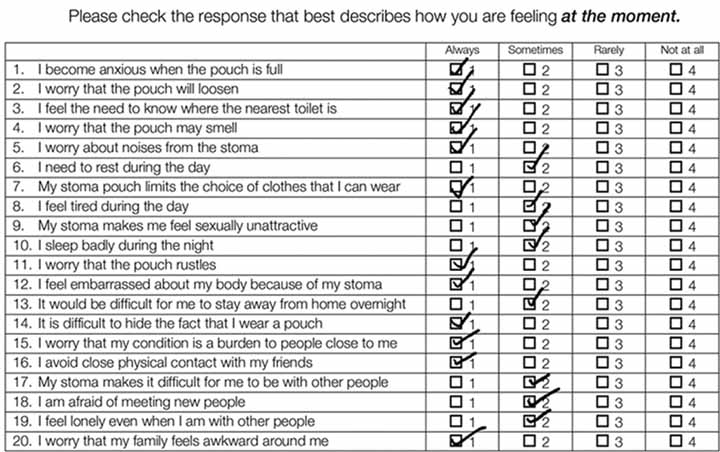

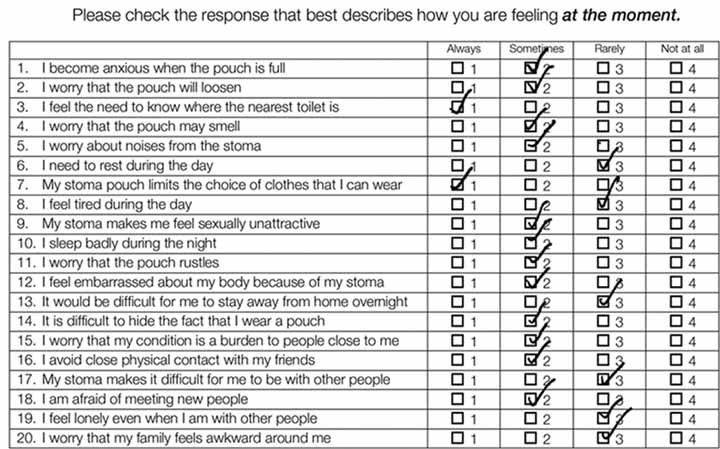

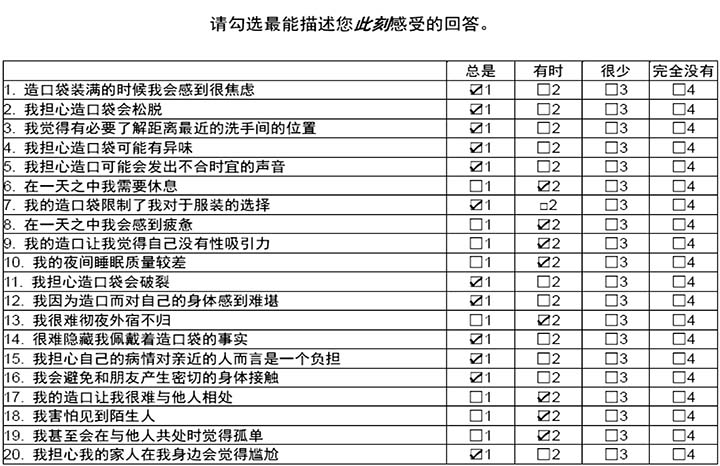

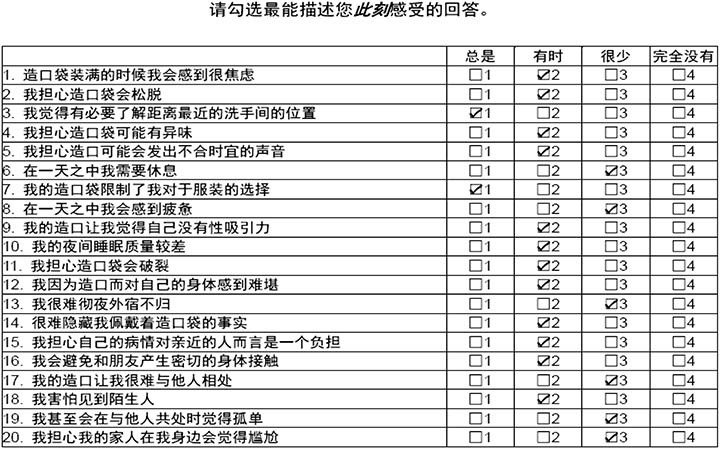

Only 28 patients completed the entire study. An example of one patient’s results that examined the differences in QoL scores between 1 week post-discharge and 8 weeks post-discharge are provided in Tables 3 and 4. At 1 week post-discharge the total QoL score was 28 out of 100, with higher scores for the ‘Always’ category (n=12), with ‘Sometimes’ receiving 8 checked responses. Nil checks were placed in the ‘Rarely’ or ‘Not at all’ categories. The most prevalent themes to responses provided in the ‘Always’ category were related to body image and stoma equipment respectively. In comparison, at the 8-week interval, the total QoL score was 44 out of 100. The patient’s responses from highest to lowest within each category were ‘Sometimes’ (n=12), ‘Rarely’ (n=6) and ‘Always’ (n=2). No responses were checked for the ‘Not at all’ category. Similarly, body image was identified as the most cause of concern.

Table 3. Example of one patient: at 1 week post-discharge

Table 4. Example of the same patient: at 8 weeks post-discharge

Discussion

Utilising the Stoma-QoL Tool was an objective and consistent method that the wound/ostomy nurses could use for assessing QoL in new ostomy patients at prescribed intervals within our facility for the duration of the study.

The initial patient interview by the wound/ostomy nurse using the Stoma-QoL tool was a revelation for both patients and staff. Patients openly discussed their anxieties relating to their forthcoming ostomy surgery, which was an unexpected outcome. The patient results described in Tables 3 and 4 showed that the higher the score achieved, the better QoL is perceived by the patient post-educational interventions.

The tool helped identify areas of difficulty that patients were experiencing in adapting to life with a stoma post-surgery. The most predominant of these difficulties were body image and factors related to ostomy equipment. These findings are consistent with other studies where body image and appliance management were factors inhibiting QoL11,12.

Overall, and anecdotally, it was noted after a 2-week period of education, patients generally became more comfortable with their change of life post-surgery. Furthermore, the results of the survey assisted in developing an individualised plan to improve QoL for each patient.

In addition, participants reported the benefits of taking part in this study as they were identifying issues about their stoma, stoma care, body image or others’ perception of themselves as causes of anxiety or concern. In doing so, this helped to enhance their personal care plan to improve their QoL post-stoma surgery13,14.

Collaboration is key to all successful interventions with patients. Wound/ostomy staff at our facility work closely with surgeons, nursing staff and case managers to promote the highest level of patient care and outcomes, thereby increasing the QoL. Case management plays a key role in successfully facilitating a smooth transition for the often emotionally fragile ostomy patient from hospital to home. This involves ensuring the patient has home care follow-up as well as supplies for home use.

Collaborative processes also extend to our hospital’s Center for Pelvic Wellness (CPW). Pelvic rehabilitation focuses on the treatment of pelvic and abdominal wall disorders in men, women and children. It is recognised that many ostomy patients experience some form of pelvic or abdominal wall dysfunction. Therefore, pelvic rehabilitation is seen as beneficial15,16. On referral to the CPW the physical therapist performs a thorough musculoskeletal assessment and provides the patient with an individualised rehabilitation program to meet their needs15,16 that may include further education, fluid and dietary management, pelvic floor physical therapy, pelvic support devices or other conservative treatments. The CPW also coordinates treatment across multiple providers.

An adjunct study finding indicated patients who regularly attended pelvic rehabilitation sessions reported improvements in QoL. Patients also stated that having someone else to speak to made it easier to deal with their ostomy15,17 which in turn was felt to improve the QoL score.

It is critical that health professionals subscribe to collaborative inter-professional practice to ensure the best possible patient outcomes for those discharged with major life-changing illness. This will ensure that patients are better able to cope with those phases of psychological adaptation that may include shock, denial, acknowledgement and adaptation to their situation18.

Study limitations

As participant numbers in this study were very small and only one patient’s example of changes in the QoL score was highlighted post-study interventions, the findings of this study would need to be supported by further large-scale research before being generalised to all patients post-ostomy surgery.

Conclusion

This study was designed to support improvement in the QoL for postoperative patients living with ostomies. Using a validated instrument over time, the researchers obtained clinical indicators of where patients are struggling the most in adjusting to the presence of a stoma. The main areas of concern were body image and issues related to the ostomy appliance. The study has assisted in promoting patients’ full potential and optimal health within the community through further education. Our analysis showed us that QoL for postoperative ostomy patients is very important.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

增强恢复:提高对于造口患者日常困难的意识

Connie Johnson, Judy Kelly, Katrina Jones Heath, Ashley Palmisano, Lawrence Jordan III and Maureen Zielinski

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.1.27-31

摘要

目的 我院形成造口的外科手术数量正不断增加。住院患者造口护理有助于帮助患者学习如何护理造口,术后尽可能独立维持较高的生活质量(QoL)。但是,还需进行更多工作以评估患者返家后的QoL。本研究旨在帮助提高造口患者出院后的QoL。帮助推动患者发挥全部潜力并在社区内获得最佳健康状况。

方法 通过电话调查,采用造口患者生活质量量表(Stoma-QoL)工具评估出院后第1、2、4和8周时,造口患者对生活的认知。Stoma-QoL工具含有20个封闭式问题,用来为QoL进行评分。使用多种文字和视觉辅助工具提供造口教育。

结果 28名新造口患者在规定时间段完成了调查。采用Stoma-QoL工具获得的最高评分作为每个时间段的QoL指标。1例患者示例显示,从第1周到第8周,评分从28上升到44。患者表达的主要担忧是身体形象和造口装置相关问题。

结论 生活质量会从身体以及情绪和社交上影响患者的幸福感。采用造口QoL调查发现,患者能够量化自身的QoL,从而使得研究小组成员能够在普林斯顿医疗系统内为患者进行个性化护理。(IRB研究批件编号:BN2332)。

引言

许多造口患者术后到在我院急诊室向伤口/造口护士看诊,结果发现,他们通常正在经历情绪上的困难,而不是造口或造口装置相关的管理问题。几名新造口患者表示对自己的境遇总体上感到悲伤;他们对于缺乏造口护理、如何调整适应造口后的生活等相关知识而感到沮丧,觉得无力控制他们的境遇,而且对自己身体形象的改变感到非常焦虑。此外,由于每周接到大量造口患者的电话,表达类似的担忧,造口医务人员决定深入调研造口患者的生活质量(QoL)。

造口术后的生活质量是患者康复过程中的一个重要因素,影响患者对自身健康和身体状态改变的接受能力,管理自身造口、与家属和朋友进行社会交往的能力,以及有意义地重新融入社会,回归有偿工作和志愿工作的能力1,2。

造口术后未能适当调整身体和心理状态可能会产生短期或长期不良后果。因此,理解造成患者缺乏自信和/或无法调整适应造口后生活(尤其是术后短期内)的具体因素非常重要。有若干工具用于评估造口术后的QoL,包括希望之城生活质量量表-造口术调查问卷、造口生活质量量表,和造口生活质量指数3,4。

Stoma-QoL工具1开发用于测量造口患者的QoL(表1)。该工具将以下造口相关问题列项:睡眠;亲密关系;与家属及密友关系;家属及亲友之外的人际关系;佩戴造口装置;入厕;身体形象;自我价值感。工具中询问的问题反映了造口患者QoL中最重要的问题1–5。

表1. Stoma-QoL工具

我院伤口/造口护士提供住院患者造口护理教育,包括提供造口教育资料文件夹。造口教育资料文件夹包括以下方面的文字信息:造口护理的各方面;使用的造口装置和护肤附件;造口用品的购买;社区资源;身体形象与性行为有关的事项。上述教育加上伤口/造口护士面对面的具体咨询帮助患者(及家属)尽可能独立护理他们的造口,同时鼓励患者维持造口术后的高QoL。患者还收到《造口术后恢复指南》,根据该治疗提供额外的指导6。在一例新造口患者在我院住院过程中,将平均每10–14小时访视患者,向其提供如何管理造口的指导和咨询。

方法

机构审查委员会:研究批准

根据《普林斯顿医疗系统医务人员规章制度》第5.05条,医务人员进行任何研究时,将接受“联邦、州法规和机构规章,包括知情同意和患者保护等各个方面”的指导7。

以医疗照护机构为依托的机构审查委员会(IRB)是施行所有研究伦理相关法规和原则的委员会,其审查提出的研究方法,确保研究符合伦理准则。例如,我院IRB委员会由指定专家小组组成,包括医疗、护理、质量保证和法务代表,负责批准或拒绝研究,并持续监控涉及人体的已批准研究。

开始任何研究前必须提交研究申请,并与IRB举行正式会议,决定是否应当继续进行研究。IRB还保护参与研究的人类受试者的权利和福利。向IRB提交的申请中应披露对研究受试者的潜在风险。本研究的研究人员声明本研究无论从身体上、保密性还是法律上均无风险8。需要注意的是,当要求回答涉及亲密关系或人际关系的问题时,某些研究受试者可能会经历潜在不适感。本研究花费数个月时间获得IRB专家小组批准。向本研究的研究人员授予的IRB研究批件编号为BN2332,给予1年时间收集数据。

由一名造口护士使用视觉材料(造口资料文件夹/手册、造口围裙)采访患者(住院患者),从急性护理开始,在整个连续的护理过程中进行文件分析(Stoma-QoL工具)。通过住院患者就诊表确定本社区教学医院的患者。

研究方法和数据收集

本研究采用定量方法。定量研究可通过采用经验证的调查工具,由患者向其回答分配分值进行实施。本研究选择Stoma-QoL5工具测量QoL,因为它简单易用。而且还认为它能够帮助识别QoL问题,促进更好的计划流程,改善造口患者QoL。该问卷有20个项目,研究受试者按李克特4分量表9对每个项目打分,分值为1到4分(总是、有时、很少、完全不会)。问题是封闭式的。可能达到的最高和最低原始分值分别为80分(最佳QoL)和20分(最差QoL)3。

在与同意的受试者计划的采访期间,由伤口/造口护士在5个时间段(即术前,术后1、2、4、8周)执行Stoma-QoL工具。

在12个月的研究期内,邀请仍为住院患者的新造口患者参与本研究。对于在研究的8周时间段时已出院,但仍然参与本研究的患者,则通过联系电话进行家庭护理环境下的调查。要求受试者采用李克特量表口头评价其对Stoma-QoL工具问题的回答。

通过住院患者就诊表确定考虑为纳入研究的患者。

研究干预

根据以上术前和术后时间段,由伤口/造口护士采用Stoma-QoL工具对新造口患者进行结构化电话采访。本研究采用视觉材料(如造口资料文件夹/宣传册和造口围裙10)来向新患者提供有关胃肠道、将形成的外科手术类型、将制造的造口类型和如何护理造口的教育知识。采用简单的描述性统计分析数据。

结果

12个月的研究期内,共有102例新造口患者。总体上,在其住院期间进行了300多次造口就诊。这102例新造口患者中,82例为永久性造口,17例为结肠造口,11例为回肠造口。患者平均年龄为65岁,75%为女性,25%为男性(表2)。

表2. 研究人口统计学数据

仅28例患者完成整个研究。表3和表4列出了1例患者结果的示例,即该患者在出院后1周和出院后8周之间QoL分值的差异。出院后1周时,QoL总分为28(满分100),勾选最高分“总是”类别的回答有12个,勾选“有时”类别的回答有8个。没有勾选“很少”或“完全没有”类别的回答。勾选“总是”类别的回答中,最普遍的主题分别与身体形象和造口装置有关。相比之下,在8周时间段时,QoL总分为44分(满分100)。患者对每个类别的回答数量从高到低为“有时”(n=12),“很少”(n=6)和“总是”(n=2)。没有勾选“完全没有”类别的答复。同样,确定身体形象是最大的担忧来源。

讨论

使用Stoma-QoL工具是一种客观而一致的方法,研究期间,伤口/造口护士可以用它在规定时间段评估我院新造口患者的QoL。

伤口/造口护士利用Stoma-QoL工具首次采访患者时,对患者和医务人员都是一次披露。患者公开讨论其对于即将到来的造口术的焦虑,这是一个意外的结果。表3和表4中列出的患者结果表明,得分越高,患者在教育性干预后感知到的QoL越好。

表3. 一例患者示例:出院后1周

表4. 同一例患者示例:出院后8周

该工具有助于发现患者在适应术后造口生活时正在经历哪些困难。这些困难中,最主要的困难是身体形象和造口装置相关的因素。这些发现与其他研究一致,这些研究表明身体形象和造口装置管理是QoL的妨碍因素11,12。

根据传闻,总体而言,注意到教育2周后,患者普遍对术后生活改变感到更加舒适。另外,本调查结果帮助为每例患者制定改善QoL的个性化方案。

此外,受试者报告了参与本研究的受益,因为他们发现了导致其焦虑或担忧的有关造口、造口护理、身体形象或其他自我认知的问题。在此过程中,这帮助他们强化了个人护理计划,改善了造口术后的QoL13,14。

合作是所有成功进行的患者干预的关键。我院伤口/造口医务人员与外科医师、护理人员和病例管理员紧密合作,促进最高水平的患者护理和结局,因此提高了QoL。病例管理在成功帮助通常情绪脆弱的造口患者从医院顺利过渡到家庭的过程中发挥着重要作用。这涉及确保患者得到家庭护理随访和家庭使用物资。

合作过程还扩大到我院的骨盆健康中心(CPW)。骨盆康复关注男性、女性和儿童骨盆和腹壁疾病的治疗。众所周知,许多造口患者经历了某些形式的骨盆或腹壁功能障碍。因此,认为骨盆康复是有益的15,16。转诊到CPW时,理疗师进行了详细的肌肉骨骼评估,并根据患者需求向其提供个性化康复方案15,16,其中可能包括进一步教育、体液和饮食管理、盆底理疗、骨盆支撑装置或其他保守治疗。CPW还在多个医疗人员之间协调治疗。

某个附属研究的结果表明,定期参加骨盆康复疗程的患者报告了QoL的改善。患者还称,与人交谈使他们更容易处理自己的造口15,17,感知到这一点后,反过来提高了QoL分值。

专业医护人员同意采取跨专业医疗实践合作非常重要,这能够确保患有改变生活的重大疾病患者出院后尽可能获得最佳的患者结局。还能确保患者更好地应对心理适应阶段,这可能包括震惊、否认、承认和适应他们的境遇18。

研究局限性

本研究受试者人数非常小,仅突出了1例患者实施研究干预后的QoL分值改变示例,将本研究的发现推及所有造口术后患者之前,需要通过进一步的大型研究进行支持。

结论

本研究旨在帮助提高造口术后患者的QoL。在一定时期使用经验证的工具进行研究时,研究人员获得了患者在调整适应造口的存在时,感到最困难的相关方面的临床指标。担忧的主要方面是身体形象和造口装置相关问题。本研究通过进一步教育帮助推动患者发挥全部潜力,并在社区内获得最佳健康状况。研究分析表明,术后造口患者的QoL非常重要。

利益冲突

作者声明无利益冲突。

资助

作者未因本研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Connie Johnson*

MSN RN WCC OMS LLE DWC

Email connie.johnson@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

Judy Kelly

BSN RN COCN WCC

Katrina Jones Heath

PT, DPT, PRPC

Ashley Palmisano

RN ONC

Lawrence Jordan III

MD

Maureen Zielinski

RN

* Corresponding author

References

- Coca C, Fernández de Larrinoa I, Serrano R & García-Llana H. The impact of specialty practice nursing care on health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies. J WOCN 2015;42(3):257–263.

- Erwin-Toth P, Thompson SJ & Stoia Davis J. Factors impacting the quality of life of people with an ostomy in North America: results from the dialogue study. J WOCN 2012;39(4):417–422.

- Prieto L, Thorsen H & Juul K. Development and validation of a quality of life questionnaire for patients with colostomy or ileostomy. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005;3:62. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-3-62

- Indrebø K L, Andersen JR. Natvig GK. The Ostomy Adjustment Scale translation into Norwegian language with validation and reliability testing. J WOCN 2014;41(4):357–364.

- Coloplast. Stoma-QoL Tool. www.coloplast.ca/ostomy/professional/clinical

- ConvaTec Inc. (2018). Your guide to recovery after Ostomy surgery. meplus.convatec.com/media/1576/meplusrecoveryhandbook_final_lores_stickerdisclaimer.pdf

- Princeton Medical Institutional Review Board. Available from https://www.princetonhcs.org/care-services/princeton-department-of-medicine/research/institutional-review-board

- Rid A, Emanuel EJ, Wendler D. Evaluating the risks of clinical research. JAMA 2010;304(13):1472–1479. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1414

- Joshi A, Kale S, Chandel S, Pal D. Likert Scale: explored and explained. Br J App Sci & Technol 2015;7:396-403. doi:10.9734/BJAST/2015/14975.

- Hooper J. Ostomy autonomy: using an anatomical apron for visual instruction. J WOCN 2012,39(3):S1-91. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182546a04

- Vonk-Klaassen SM, de Vocht HM & den Ouden MEM et al. Ostomy-related problems and their impact on quality of life of colorectal cancer ostomates: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 2016;25:125–133. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-1050-3

- Liao C, QinY. Factors associated with stoma quality of life among stoma patients. Int J Nurs Sci 2014;196–201.

- Schultz JC. Preparing the patient for colostomy care: a lesson well learned. Ostomy Wound Manage 2002;48(10):22–25.

- Jayarajah U, Samarasekera DN. Psychological adaptation to alteration of body image among stoma patients: a descriptive study. Indian J Psychol Med 2017;39(1):63–68. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.198944

- Kim JK, Jeon BG, Song YS, et al. Biofeedback therapy before ileostomy closure in patients undergoing sphincter-saving surgery for rectal cancer: a pilot study [published correction appears in Ann Coloproctol 2015 Oct;31(5):205]. Ann Coloproctol 2015;31(4):138–143. doi:10.3393/ac.2015.31.4.138

- Physical therapy considerations for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Herman & Wallace Blog; 2019. Available from: https://hermanwallace.com/blog/physical-therapy-considerations-for-patients-with-inflammatory-bowel-disease/

- Gautam S, Koirala S, Poudel A, Paudel D. Psychosocial adjustment among patients with ostomy: a survey in stoma clinics, Nepal. Dovepress 29 August 2016;2016(6):13–21. doi: 10.2147/NRR.S112614

- United Ostomy Association of America. Emotional issues. United Ostomy Associations of America, 2020. Available from: www.ostomy.org/emotional-issues/