Volume 40 Number 1

Terminal ulcers, SCALE, skin failure, and unavoidable pressure injuries: results of the 2019 Terminology Survey

R. Gary Sibbald and Elizabeth A. Ayello

Keywords pressure injuries, Kennedy terminal ulcer, SCALE, skin changes at life’s end, skin failure, survey, terminal ulcers, terminology, Trombley-Brennan terminal tissue injury

For referencing Sibbald RG and Ayello EA. Terminal ulcers, SCALE, skin failure, and unavoidable pressure injuries: results of the 2019 Terminology Survey. WCET® Journal 2020;40(1):18-26

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.1.18-26

Abstract

This article reports the results of a global wound care community survey on Kennedy terminal ulcers, skin changes at life’s end, Trombley-Brennan terminal tissue injuries, skin failure and unavoidable pressure injury terminology. The survey consisted of 10 respondent-ranked statements to determine their level of agreement. There were 505 respondents documented. Each statement required 80% of respondents to agree (either “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree”) for the statement to reach consensus. Nine of the 10 statements reached consensus. Comments from two additional open-ended questions were grouped by theme. Conclusions and suggested recommendations for next steps are discussed. This summary is designed to improve clinical care and foster research into current criteria for unavoidable skin changes at the end of life.

Introduction

In March 2019, an article was published in Advances in Skin & Wound Care entitled “Reexamining the Literature on Terminal Ulcers, SCALE, Skin Failure, and Unavoidable Pressure Injuries.”1 It summarised and proposed relationships among terminal ulcers, skin failure, Skin Changes At Life’s End (SCALE), and unavoidable pressure injuries (PIs), based in part on sessions hosted at the 2017 National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel conference.1 This article presents the results of a survey that was partially based on that article and designed to assess healthcare professionals’ opinions about relevant terminology to determine their levels of agreement and consensus.

Methods

Evidence-based medicine is a combination of the scientific evidence, expert opinion/knowledge, and patient preference.2 This survey was designed to solicit expert knowledge/opinion on this terminology. The survey was created by the study authors in January and February 2019 and implemented with the SurveyMonkey platform (San Mateo, California). It contained seven demographic questions about respondents’ clinical experience and background, as well as one question on whether the respondent had read the original CE/CME article.1 The instructions stated that it was not necessary to have read the article to complete the survey, and the questions were designed to stand alone from it.

In the second section of the survey, participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with 10 consensus statements. The options were strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree. Participants could also elaborate by appending narrative comments to any of the survey questions. The consensus statements included four questions concerning skin failure, two questions on Kennedy terminal lesions (now known as Kennedy terminal ulcers [KTUs]), and a single question for each of the following: SCALE, Trombley-Brennan terminal tissue injury, avoidability of terminal ulceration, and the CMS definition of PI. A final open-ended question asked participants to comment on what they believe is needed to provide a better conceptual framework for end-of-life skin changes.

Respondents were informed at the start of the survey that results were anonymous and completion implied permission to participate. As an incentive, participants could enter their name and email at the end of the survey for a chance to win one of five $100 American Express gift cards or a print copy of a wound care textbook. This information was stored separately from survey results, and only deidentified results were shared with these authors.

The survey was open from March 1 to June 30, 2019. To publicise the survey, notices were placed in the March through June issues of Advances in Skin & Wound Care, as well as in one issue of Nursing2019. In addition, emails were sent to members of relevant organisations that agreed to disseminate notification about the survey, including the American Professional Wound Care Association, the World Union of Wound Healing Societies, the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®, the International Interprofessional Wound Care Group, and attendees of the International Interprofessional Wound Care Course. Notices were also displayed on the journal website (www.woundcarejournal.com) and social media platforms, as well as in professional presentations by the survey coauthors.

Demographic results

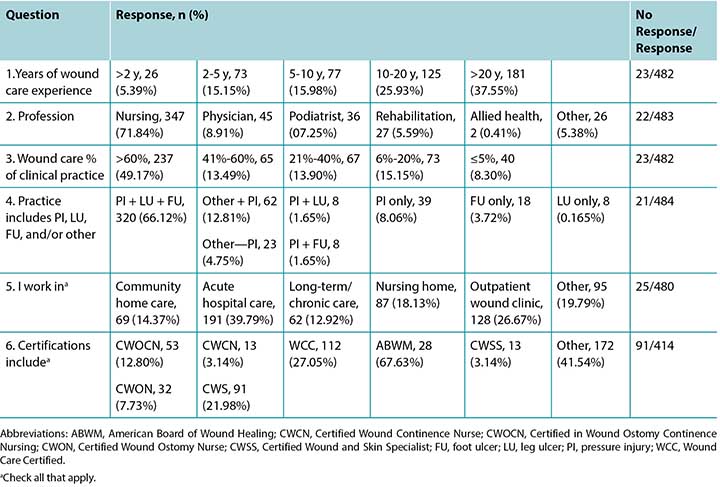

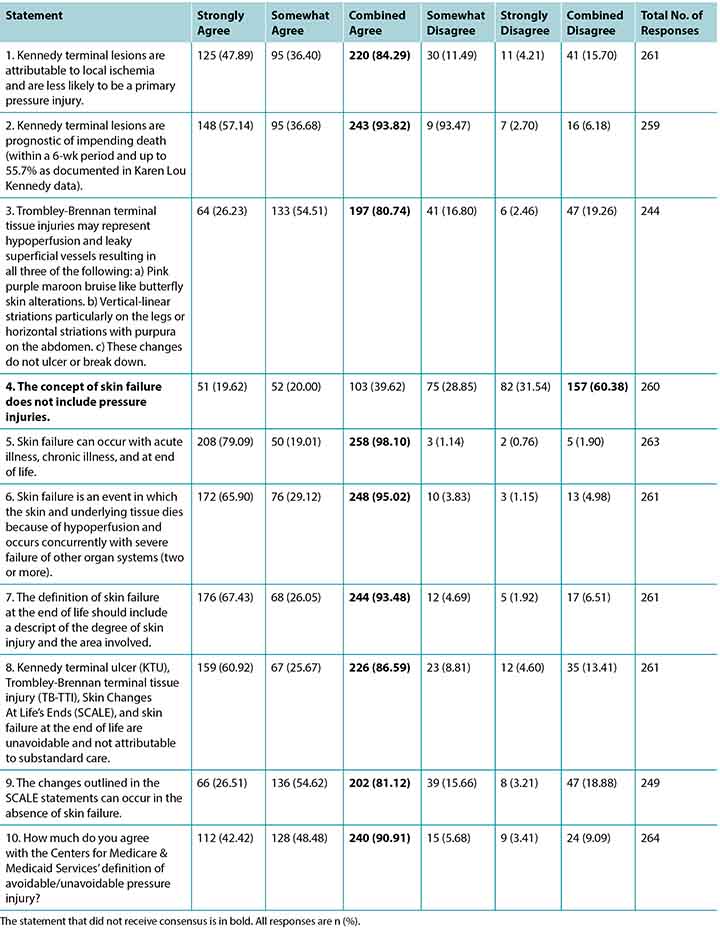

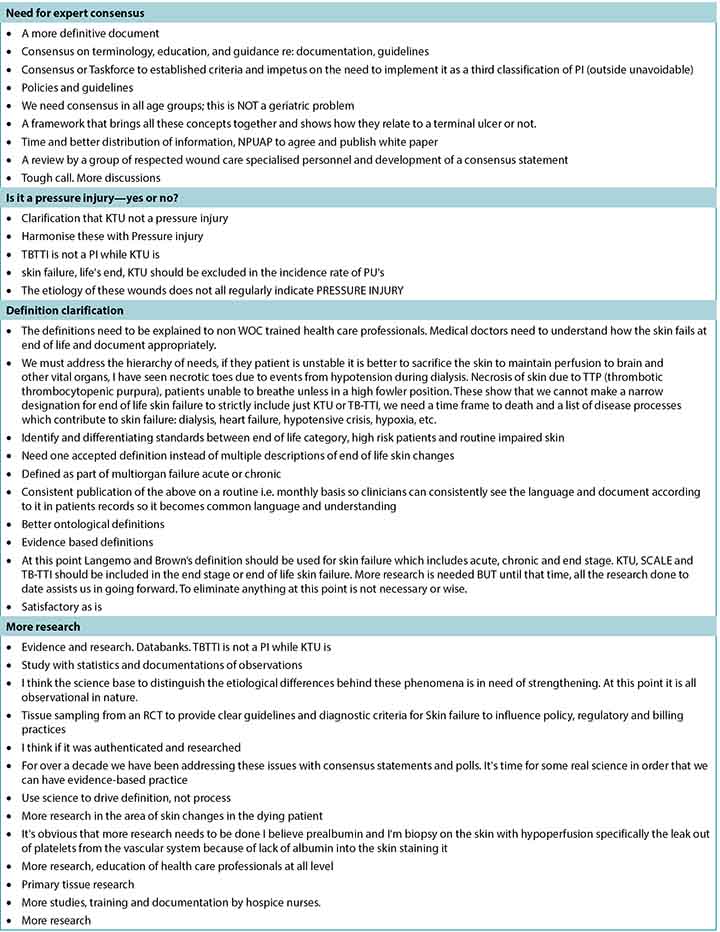

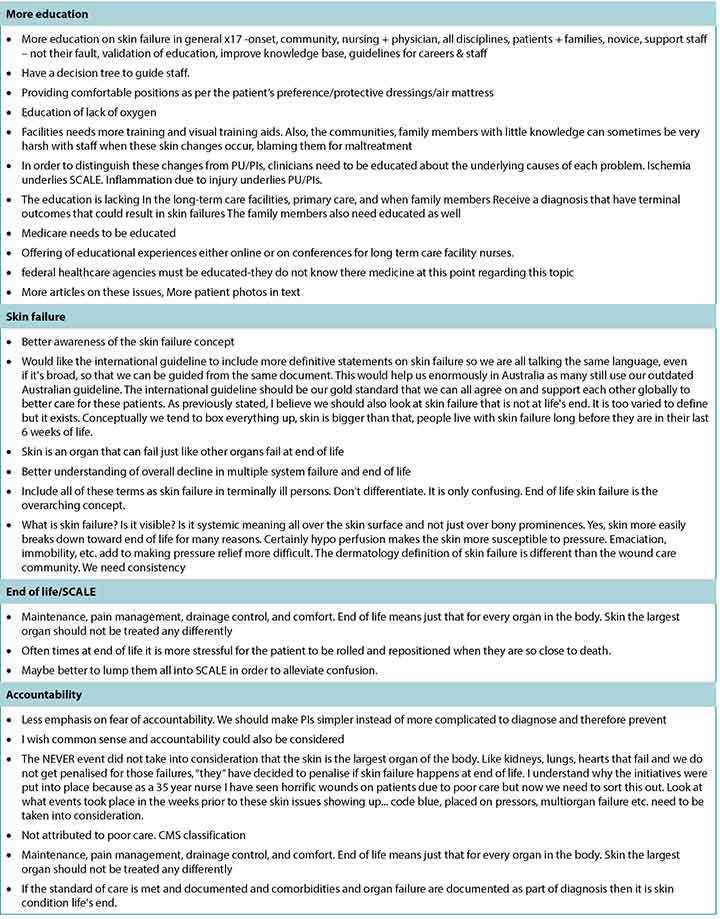

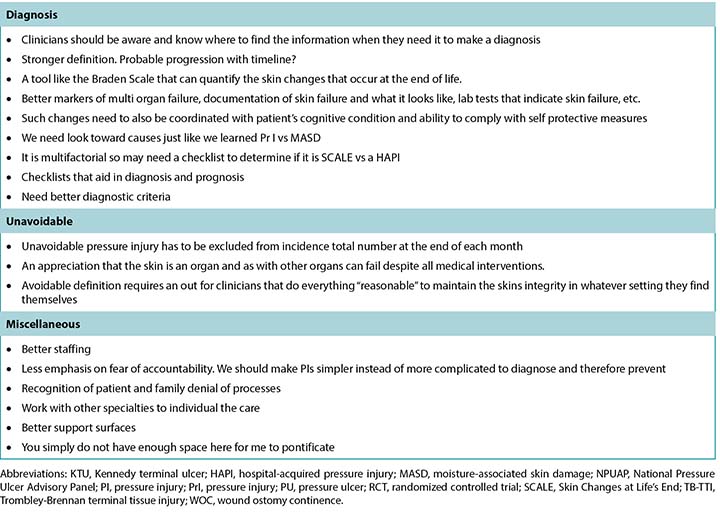

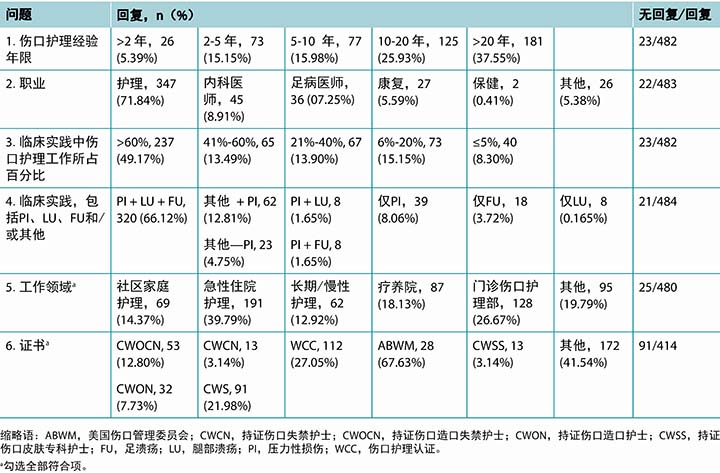

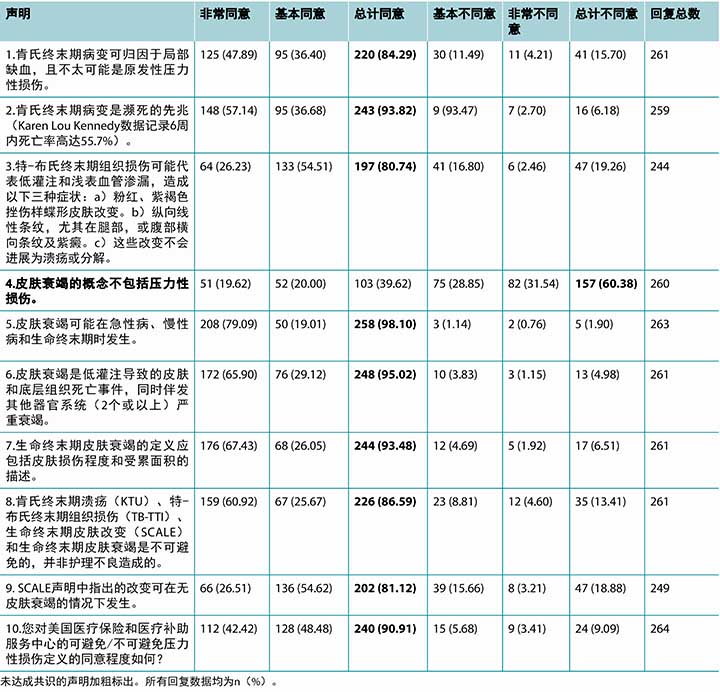

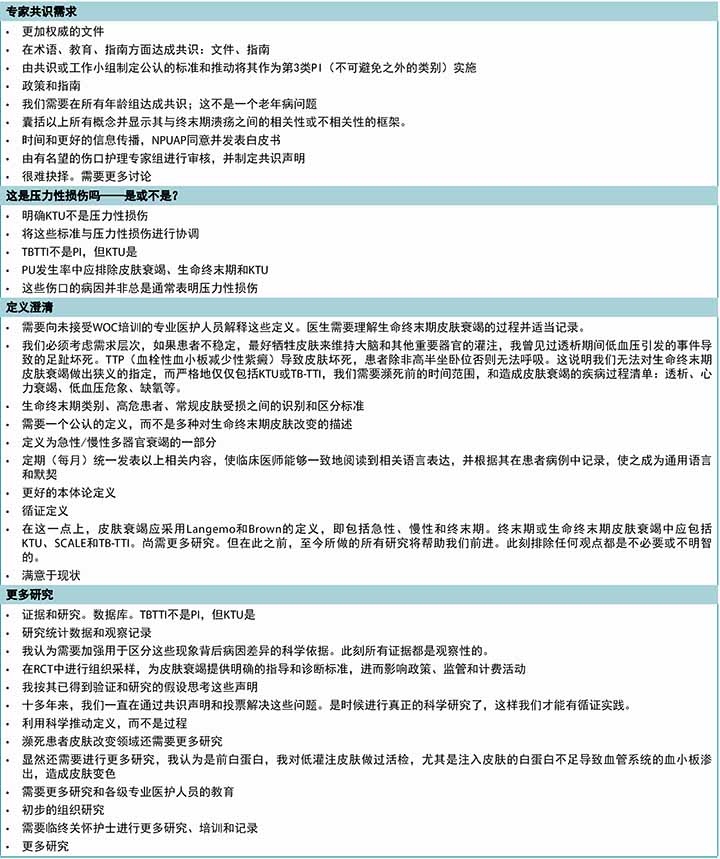

A total of 505 responses were received, but not all respondents answered every question. Most completed surveys were from North America, with global respondents from Europe, South America, the Middle East, Asia, and Australia. Fewer than half of the participants (n = 208, 42.89%) stated they had read the article the survey was based on; 20 respondents did not answer this question. Table 1 summarises the participant demographics. Table 2 reports on their responses by level of agreement or disagreement. Each statement required 80% of respondents to agree (either strongly agree or somewhat agree) to reach consensus; 9 of the 10 statements reached consensus. A total of 119 comments were received, and selected open-ended responses are grouped by themes in Table 3.

Table 1. Summary of responses

Table 2. Results by Statement

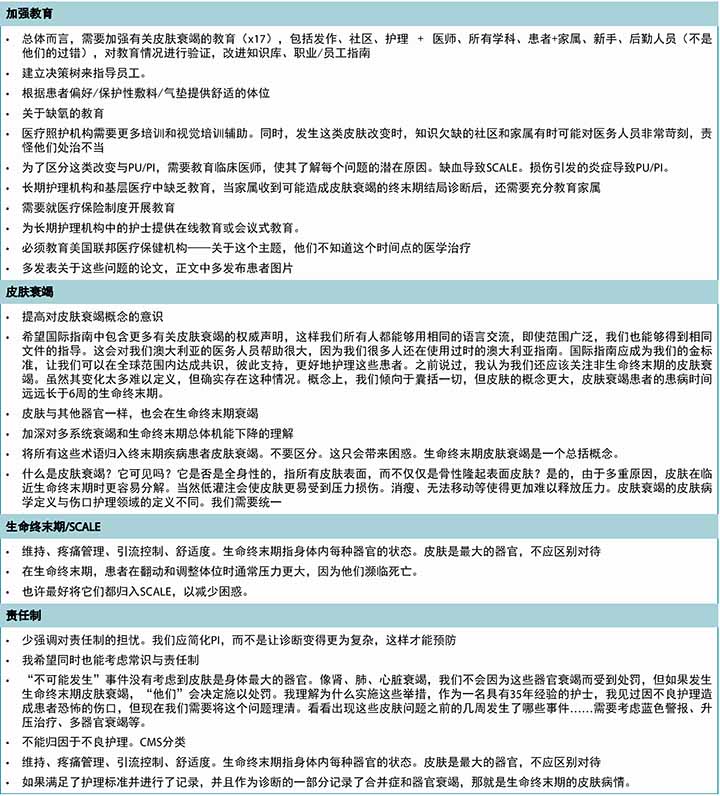

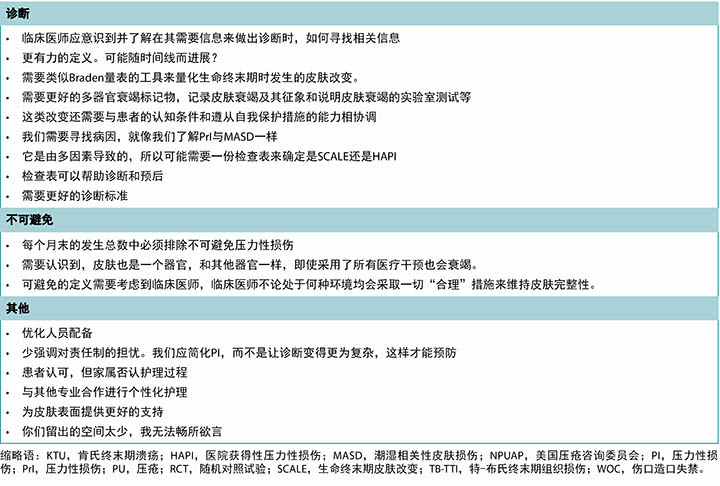

Table 3. Selected written comments grouped by theme

Table 3 continued. Selected written comments grouped by theme

Table 3 continued. Selected written comments grouped by theme

Survey respondents were experienced in skin and wound care, with the largest group (n = 181, 37.55%) having more than 20 years of experience and 125 respondents (25.93%) stating they had 10 to 20 years’ experience (Table 1). Of the 505 respondents, 483 identified their profession. Most were nurses (n = 347, 71.84%) who primarily identified as direct care providers, NPs, or nurse educators. Responding physicians (n = 45, 8.91%) were primarily specialists with identified specialties including plastic or general surgery, emergency medicine, and dermatology. Almost half of the respondents (n = 237, 49.17%) estimated that wound care comprised greater than 60% of their clinical practice. Pressure injuries were a part of clinical care for 90.2% of respondents (n = 437). Two-thirds of the respondents (n = 320, 66.12%) took care of patients with all three of the following: leg ulcers, foot ulcers, and PIs. The majority worked in acute hospital care (n = 191, 39.79%), followed by outpatient wound care clinics (n = 128, 26.67%).

One question in the demographic section of the survey asked about participant certifications. Seven common certifications and an “other” category were provided as responses, and respondents could check all that applied. In total, the respondents held 342 individual certifications, but some individuals held more than one. Most of the “other” responses (n = 172) were advanced degrees and not formal wound care certifications.

Consensus statements

The following section details each consensus statement and the reported results. To help contextualise the responses, a summary of some of the concepts is included. For a more in-depth overview, refer to the summary article and/or the primary sources of related terms.

All of the statements reached consensus except for the proposed association of PIs as part of skin failure. High-quality research is needed to validate the clinical observations and proposed mechanisms of these injuries.

Statements 1 and 2: Kennedy Terminal Ulcers

Statement 1, “Kennedy terminal lesions are attributable to local ischemia and are less likely to be a primary pressure injury,” reached 84.29% agreement. In Statement 2, “Kennedy terminal lesions are prognostic of impending death,” there was 93.82% agreement.

The KTU was one of the first terminal ulcers reported in modern literature.3 Therefore, it is possible that respondents were familiar with this lesion. Similar to Charcot’s ulcer ominous, it is most common over the sacrum or coccyx. It is described as a red, yellow, and/or black pear-shaped lesion that appears suddenly. It may be on intact skin or form an erosion (ie, loss of epidermis with an epidermal base) or an ulcer (ie, loss of epidermis with a dermal or deeper base).3

The majority of respondents agreed that ischemia probably played a greater role than pressure in KTUs (84.29%; Statement 1). The sacrum does not have good collateral circulation and is prone to injury. When the heart or brain is compromised, circulation from the skin, kidneys, liver, lungs, or gastrointestinal tract is often shunted to preserve vital functions. Blood is shifted—literally squeezed—by vasoconstriction, first from skin and soft tissues toward the heart and brain, and then from visceral organs because of the ingenious adrenergic distribution in the body organs that makes the brain the most protected organ.4 It is hypothesised that when the capillaries become leaky, local hemorrhage can cause a red color on the surface of the skin. As a bruise resolves, it can evolve to a yellow-brown color. If local ischemia is complete, and the blood supply shuts down, a black color can result. The color changes can vary in the KTU depending on the relative amount of ischemia.

Knight and colleagues5 measured sacral local tensions of oxygen and carbon dioxide, along with sweat lactate and urea, for indirect measures of ischemia in 14 healthy volunteers. With varying external applied pressures, they concluded that oxygen levels were lowered in soft tissues subjected to higher pressures and that this decrease is generally associated with an increase in carbon dioxide levels “well above the normal basal levels (with) considerable increases, in some cases up to twofold, in the concentrations of both sweat lactate and urea at the loaded site compared with the unloaded control.”5 The investigators also stated “…it is well established that prolonged-pressure ischemia will affect the viability of soft tissues, leading to their eventual breakdown.” Therefore, the KTU may represent local ischemia partly from shunted cutaneous circulation subject to a much lower-than-usual pressure, contributing to the local lesion.

Although more than 90% of the respondents agreed that KTUs are prognostic of impending death, one of the comments noted that according to Kennedy’s data 44.3% of patients did not die in the 6-week period following the lesion’s appearance. There is only one published data-based article about KTUs.3 Future research should include prospective databases, case series, and cohort-based studies. These lesions are most likely unavoidable and should not be included in PI incidence and prevalence studies.6

According to the CMS’s State Operations Manual: Guidance to Surveyors (F686), KTUs need to be differentiated from other ulcers/injuries:6

The facility is responsible for accurately assessing and classifying an ulcer as a KTU or other type of PU /PI and demonstrate that appropriate preventative measures were in place to prevent non-KTU pressure ulcers. KTUs have certain characteristics which differentiate them from pressure ulcers such as the following:

- KTUs appear suddenly and within hours;

- Usually appear on the sacrum and coccyx but can appear on the heels, posterior calf muscles, arms and elbows;

- Edges are usually irregular and are red, yellow, and black as the ulcer progresses, often described as pear, butterfly or horseshoe shaped; and

- Often appear as an abrasion, blister, or darkened area and may develop rapidly to a Stage 2, Stage 3, or Stage 4 injury.

However, there is no statement regarding KTUs in the Resident Assessment Instrument User’s Manual for long-term care.7

Statement 3: Trombley-Brennan Terminal Tissue Injuries

The third survey statement reached 80.74% agreement. In examining the etiology of these injuries, the pink color would again come from hemorrhage of the superficial vessels, and the purple-maroon color could arise from deeper vessels and could mature into a bruise type of evolution. Vertical striations on the legs and horizontal areas on the abdomen may follow skin folds, edema patterns, or the vascular plexus structure of the skin.8

In the original report, none of the lesions lost their skin integrity or broke down to form an ulcer. However, the survey authors received seven respondent comments about these injuries breaking down with ulcer formation.

Statements 4 to 7: Skin Failure

Of all the concepts in the survey, skin failure has the most related articles in the literature.9-13 Skin failure may be acute or chronic and occur at the end of life or with acute and chronic illnesses.9-13 All but one of the statements on skin failure achieved consensus. In Statement 7, “The definition of skin failure at the end of life should include a description of the degree of skin injury and the area involved,” there was 93.4% agreement. Statement 6, “Skin failure is an event in which the skin and underlying tissue die because of hypoperfusion and occurs concurrently with severe failure of other organ systems (two or more),” achieved 95.62% agreement. Statement 5, “Skin failure can occur with acute illness, chronic illness, and at end of life,” achieved an even greater 98.1% agreement. However, consensus was not reached for Statement 4, “The concept of skin failure does not include pressure injuries;” 60.38% of respondents disagreed with this statement.

In defining skin failure, Langemo and Brown9 state: “Skin failure is an event in which the skin and underlying tissue die due to hypoperfusion that occurs concurrent with severe dysfunction or failure of other organ systems.” Levine has also published commentaries on skin failure10,11 that include proposed definitions of skin failure such as “the state in which tissue tolerance is so compromised that cells can no longer survive in zones of physiologic impairment such as hypoxia, local mechanical stresses, impaired delivery of nutrients, and buildup of toxic metabolic byproducts. In this schema, skin failure can occur over bony prominences where skin and underlying tissues, including muscle, are stretched and subjected to external pressure.”11 These criteria for skin failure with hypoperfusion and compromise of two or more other organs can occur with an acute illness, chronic illness, or at the end of life.

What continues to need clarity is whether skin failure involves one or more organs. The survey featured a number of written comments concerning the desire for more evidence to clarify whether one severe organ failure is enough (eg, cardiac arrest) or if two internal organs must fail.

It is important to distinguish skin failure from other dermatologic disease processes that can cause skin compromise from mechanisms other than hypoperfusion (eg, erythroderma with hyperperfusion compromise of the skin where >90% of the skin is red). The extent of skin compromise is an important component in describing ischemic injury associated with skin failure. Specific descriptions of skin changes should also be documented. Some written comments from the survey suggest that the severity of skin injury (erythema, erosion, ulcer, necrosis, bruising) and extent of the injury (percent of body surface area) may be a better documentation base to define treatment than the degree of skin injury.

The respondents agreed that skin failure can occur at the end of life and also with acute and chronic illnesses. There are two data-based articles on skin failure associated with acute illnesses from Delmore and colleagues.12,13 In 2015, they defined acute skin failure as “hypoperfusion of the skin resulting in tissue death in the setting of critical illness”12 and later revised the definition as “the hypoperfusion state that leads to tissue death that occurs simultaneously to a critical illness.”13

There is evidence that, with ischemia, the threshold pressure for a PI is lower and may occur even with an acceptable standard of care.6 There were 15 open-ended comments stating that PIs occur more readily with skin failure or are part of the concept of skin failure.

Statement 9: SCALE

For the statement “The changes outlined in the SCALE statements can occur in the absence of skin failure,” there was 81.42% agreement and thus consensus. Skin Changes At Life’s End14,15 can occur as patients are dying without two internal organs failing, although many of the SCALE criteria may be present within the definition of skin failure. Further, SCALE includes changes in skin color, turgor, or integrity (involving factors such as medical devices, incontinence, chemical irritants, chronic exposure to body fluids, skin tears, shear, friction, and infection). Suboptimal nutrition can result in weight loss, wasting, and skin changes with dehydration. Diminished tissue perfusion may cause a local decrease in skin temperature, mottled vasculature, and skin necrosis or gangrene. Pressure injuries also a component of SCALE. Most of these changes may be unavoidable.

Statements 8 and 10: Unavoidable Skin Changes

For Statement 8, “Kennedy terminal ulcer (KTU), Trombley-Brennan terminal tissue injury (TB-TII), Skin Changes At Life’s End (SCALE), and skin failure at the end of life are unavoidable and not attributable to substandard care,” there was 86.59% agreement and thus consensus. Similarly, in Statement 10, “How much do you agree with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ definition of avoidable/unavoidable pressure injury?” there was 90.91% agreement and consensus.

The most current CMS definitions (effective November 28, 2017) provided to distinguish avoidable and unavoidable PIs are as follows:6

“Avoidable” means that the resident developed a pressure ulcer/injury and that the facility did not do one or more of the following: evaluate the resident’s clinical condition and risk factors; define and implement interventions that are consistent with resident needs, resident goals, and professional standards of practice; monitor and evaluate the impact of the interventions; or revise the interventions as appropriate.

“Unavoidable” means that the resident developed a pressure ulcer/injury even though the facility has evaluated the resident’s clinical condition and risk factors; defined and implemented interventions that are consistent with resident needs, goals, and professional standards of practice; monitored and evaluated the impact of the interventions; and revised the approaches as appropriate.

The CMS also provides some clarification regarding PIs at the end of life. Even if a resident has an advance directive, the facility still needs to provide the resident with supportive and pertinent care as long as it is not prohibited by the directive.6 Further, statements about whether a PI is avoidable or unavoidable are also provided:6

It is important for surveyors to understand that when a facility has implemented individualised approaches for end-of-life care in accordance with the resident’s wishes, the development, continuation, or worsening of a PU/PI may be considered unavoidable. If the facility has implemented appropriate efforts to stabilise the resident’s condition (or indicated why the condition cannot or should not be stabilised) and has provided care to prevent or treat existing PU/PIs (including pertinent, routine, lesser aggressive approaches, such as cleaning, turning, repositioning), the PU/PI may be considered unavoidable and consistent with regulatory requirements.

Some of the written responses expressed concern about how to define “substandard care.” Perhaps the elements of the process that CMS describes in the “avoidable” definition could be used to define what survey respondents called “substandard care.”

Open-Ended Question

At the end of the survey, survey authors asked for write-in comments; some of these have been organised by theme in Table 3. Many survey participants stated they would like a more definitive statement on skin failure/end-of-life skin changes (eg, from a task force or consensus group). They also requested definitions that are more closely aligned with evidence. Clearly, there is a need for more scientific evidence through research using an improved conceptual framework for end-of-life skin failure. Specific ideas about diagnostic criteria need to be validated, and enhanced definition enhancements require further research. Clinicians also want to know more about how to describe these wounds, how they impact funding, and how to relate these issues to patients and families. The need for more focused education for clinicians is a future opportunity.

Conclusions

This study represents a first step in exploring the global skin and wound care community’s opinions about terminal ulcers/injuries, skin failure, and SCALE in a structured way. It was clear respondents want clarified terminology and hope for a global consensus. Importantly, there was a lack of consensus as to whether skin failure includes PIs. The need for more research in this area, including clear diagnostic criteria, was repeatedly expressed by survey participants. The next steps could include a knowledge translation task force or a global consensus conference to explore terminology and propose scientific validation studies. This research may be facilitated by the development of databases through sponsoring national or international professional organisations.

Practice pearls

- KTU and TB-TTI are believed to be terminal ulcers observed in patients at end of life.

- Survey results reveal that there is no current consensus as to whether the concept of skin failure includes pressure injuries.

- Skin failure (acute, chronic, and/or end of life) criteria must be further defined and then validated.

- Although definitions for unavoidable and avoidable PIs exist from the CMS and other regulatory bodies, global criteria for determining when a PI is avoidable or unavoidable should be validated and agreed upon.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

终末期溃疡、SCALE、皮肤衰竭和不可避免压力性损伤:2019年术语调查结果

R. Gary Sibbald and Elizabeth A. Ayello

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.1.18-26

摘要

本文报告了全球的伤口护理界对肯氏终末期溃疡、生命终末期皮肤改变、特-布氏终末期组织损伤、皮肤衰竭和不可避免压力性损伤等术语进行的调查结果。调查包含10项由受访者分级的声明,以确定受访者的同意程度。记录了505名受访者的回复。每项声明需要获得80%的受访者同意(“非常同意”或“基本同意”)才能达成对于该声明的共识。10项声明有中9项达成共识。另外将2个附加开放式问题的评论按主题分组。讨论了结论和下一步的建议。本总结旨在改善生命终末期不可避免皮肤改变的临床护理,并促成对其当前标准的研究。

引言

2019年3月,《皮肤与伤口护理进展》杂志中发表了一篇题为“对有关终末期溃疡、SCALE、皮肤衰竭和不可避免压力性损伤的文献进行的重新审视”的论文。1其部分基于美国压疮咨询委员会2017年大会举办的研讨会,总结和提出了终末期溃疡、皮肤衰竭、生命终末期皮肤改变(SCALE)和不可避免压力性损伤(PI)之间的关系。1本文介绍了部分基于该文进行的、旨在评估专业医护人员对相关术语意见的一项调查的结果,从而确定其同意程度和共识度。

方法

循证医学是科学证据、专家意见/知识和患者偏好的结合。2 本调查旨在征求关于以上术语的专家意见/知识。本调查由研究作者在2019年1月和2月创建,并在SurveyMonkey平台(加利福尼亚州圣马特奥)上实施。其中包括7个有关受访者临床经验和背景的人口统计学问题,以及1个有关受访者是否阅读了原始CE/CME论文的问题。1填写说明中称,完成本调查无需阅读该论文,本调查中的问题是独立于该论文而设计的问题。

在调查的第2部分,要求受访者指出他们对10个共识声明的同意程度。意见分为非常同意、基本同意、基本不同意和非常不同意。受访者还可以在任何调查问题后附上叙述评论进行阐述。共识声明包括4个有关皮肤衰竭的问题,2个关于肯氏终末期病变的问题(现称为肯氏终末期溃疡[KTU]),以及以下每项各1个问题:SCALE、特-布氏终末期组织损伤,终末期溃疡的可避免性、CMS的PI定义。最后的一个开放式问题是要求受访者提供意见,评论其认为为了提供更好的生命终末期皮肤改变概念框架还需要什么。

调查开始时,告知受访者结果是匿名的,填写本调查即意味着其对参与调查的许可。作为激励,在调查结束时受访者可以填写其姓名和电子邮箱,有机会赢得一份价值100美元的美国运通礼品卡(总计5份),或1册伤口护理教科书的纸质本。该信息与调查结果分开存储,仅向作者分享去标识化结果。

本调查于2019年3月1日至6月30日开放填写。为宣传本调查,在《皮肤与伤口护理进展》3月期到6月期,以及1期《护理2019》中刊登告示。另外,向同意传播本调查告示的有关组织成员发送电子邮件,包括美国专业伤口护理协会、世界伤口愈合学会联合会、世界造口治疗师委员会®、国际跨专业伤口护理组以及国际跨专业伤口护理课程的学员。还在杂志网站(www.woundcarejournal.com)、社交媒体平台,和本调查共同作者的专业演讲中发布调查告示。

人口统计学结果

共收到505份回复,但并非所有受访者均回答了每一个问题。多数调查回复来自北美洲,另外还有来自欧洲、南美洲、中东、亚洲和澳大利亚等世界各地的回复。不到一半的受访者(n=208,42.89%)称,其读过本调查的参考论文;20名受访者未回答该问题。表1总结了受访者的人口统计学特征。表2根据同意和不同意程度报告了其回复。每项声明需要80%的受访者同意(非常同意或基本同意)才能达成共识;10项声明中9项达成共识。共收到119条评论,根据主题对入选的开放式问题回复分组,见表3。

表1. 回复总结

表2. 各声明的结果

表3 按主题分组的选定书面评论

表3 按主题分组的选定书面评论(续)

表3 按主题分组的选定书面评论(续)

调查受访者对皮肤和伤口护理经验丰富,人数最多的一组(n=181,37.55%)有20年以上的经验,另外125名受访者(25.93%)称他们有10到20年经验(表1)。这505名受访者中,483名表明了职业。大多数是护士(n=347,71.84%),主要是直接护理人员、执业护士,或护士导师。受访医师(n=45,8.91%)主要是整形或普通外科、急诊医学和皮肤科等认定专业的专科医师。几乎一半的受访者(n=237,49.17%)估计伤口护理占其临床护理实践的60%以上。90.2%的受访者(n=437)称压力性损伤是其临床护理的一部分。三分之二的受访者(n=320,66.12%)护理过所有以下三种疾病的患者:腿部溃疡、足溃疡、压力性损伤。大部分受访者(n=191,39.79%)从事急性住院护理方面的工作,其次是门诊伤口护理部(n=128,26.67%)。

本调查的人口统计学部分中的1个问题是询问受访者的资质证书。调查提供了7种常见证书和1个“其他”类别作为回答项,受访者可以勾选其拥有的所有证书。受访者总计拥有342份个人证书,但某些人士同时持有多份证书。大部分选择“其他”的受访者(n=172)拥有高级学位,但不是正式的伤口护理证书。

共识声明

下文详述了每项共识声明和所报告的结果。为帮助理解回复的背景,提供了部分概念的总结。如需了解更深入的概述,参阅相关术语的摘要文章和/或原始来源。

除了有关PI作为皮肤衰竭一部分的拟议关联的声明,其他所有声明均达成共识。但尚需高质量研究来验证临床观察结果和这些损伤的拟议机制。

声明1和2:肯氏终末期溃疡

声明1,“肯氏终末期病变可归因于局部缺血,且不太可能是原发性压力性损伤,”获得84.29%的同意。声明2,“肯氏终末期病变是濒死的先兆,”获得93.82%的同意。

KTU是现代文献中首个报告的终末期溃疡之一。3因此,可能受访者熟悉该病变。与Charcot溃疡前兆类似,KTU最常见于骶骨或尾骨。据文献描述,KTU为突发的红色、黄色和/或黑色梨形病变。可能出现在完整皮肤上,或形成糜烂(即表皮缺损,留有表皮基底)或溃疡(即表皮缺损,留有真皮或更深层基底)。3

大部分受访者同意,在KTU中,缺血的影响可能超过压力(84.29%;声明1)。骶骨缺乏良好的侧支循环,容易损伤。心脏或大脑受损后,皮肤、肾脏、肝脏、肺或胃肠道的循环通常被分流,以保存生命机能。通过血管收缩将血液转移(确切的说,是挤出),先从皮肤和软组织转移到心脏和大脑,然后从脏器转移,因为人体器官中巧妙的肾上腺素能分布使大脑成为最受保护的器官。4据假说,毛细血管渗漏时,局部出血可导致皮肤表面呈红色。挫伤消退后,其可变为棕黄色。如果发生完全局部缺血,供血中断,则可能变为黑色。KTU中,皮肤的颜色改变可能取决于相对缺血量。

Knight及其同事5测量了14名健康志愿者的骶骨局部氧气和二氧化碳张力,以及汗液乳酸和尿液,用于间接测量缺血。施加不同外部压力后,他们得出结论,更高压力下,软组织氧含量降低,这种氧含量降低通常与二氧化碳含量升高到“远超正常基础水平,升幅较大,在一些病例中,承受载荷的部位与未承受载荷的对照相比,汗液乳酸和尿液浓度均升高达2倍。”5研究人员还称“……众所周知,长时间压力性缺血将影响软组织活性,最终造成软组织分解。”因此,KTU可能代表因分流的皮肤血液循环承受的压力远低于正常压力这一部分原因而造成的局部缺血,从而导致局部病变。

尽管超过90%的受访者同意,KTU是濒死的先兆,但其中一个评论指出,根据Kennedy的数据,44.3%的患者出现这种病变后的6周内没有死亡。有关KTU的已发表数据文献只有一篇。3未来研究应包括前瞻性数据库、病例系列和队列研究。这些病变几乎是不可避免的,不应纳入PI发生率和患病率研究。6

根据CMS的《国家操作手册:调查员指南》(F686),需要区分KTU与其他溃疡/损伤:6

医疗照护机构负责准确评估和将溃疡分类为KTU或其他PU/PI类型,并证明采取了适当预防措施防止非KTU压疮。KTU的某些特征与压疮不同,如:

- KTU为突发型,在数小时内发生;

- 通常出现在骶骨和尾骨,但也可出现在足跟、小腿后肌、手臂和手肘;

- 边缘通常不规则,随着溃疡进展呈红色、黄色、黑色,通常为梨形、蝶形或马蹄形;及

- 外观通常似擦伤、水疱或暗区,可能迅速发展为2、3、4期损伤。

但是,在长期护理的《居民评估工具用户手册》中没有关于KTU的声明。7

声明3:特-布氏终末期组织损伤

第3个调查声明获得80.74%的同意。检查这些损伤的病因时,粉色还是来源于浅表血管出血,紫褐色则可能来自更深层血管,并发展成一种挫伤的演变类型。腿部的纵向条纹和腹部的横向条纹区可能是沿皮肤褶皱、水肿图案或皮肤的血管丛结构形成的。8

原始报告中,以上病变均没有丧失其皮肤完整性,或分解形成溃疡。但是,调查作者收到7条关于这些损伤分解且形成溃疡的受访者评论。

声明4至7:皮肤衰竭

在调查的所有概念中,文献中皮肤衰竭的相关论文最多。9-13皮肤衰竭可以是急性或慢性的,也可以在生命终末期时发生,或伴发急性病和慢性病。9-13关于皮肤衰竭的声明,除了1项声明外,其他均达成共识。声明7,“生命终末期皮肤衰竭的定义应包括皮肤损伤程度和受累面积的描述”获得93.4%的同意。声明6,“皮肤衰竭是低灌注导致的皮肤和底层组织死亡事件,同时伴发其他器官系统(2个或以上)严重衰竭”获得95.62%的同意。声明5,“皮肤衰竭可能在急性病、慢性病和生命终末期时发生”获得高达98.1%的同意。但是,声明4“皮肤衰竭的概念不包括压力性损伤”未达成共识,有60.38%的受访者不同意该声明。

定义皮肤衰竭时,Langemo和Brown9称:“皮肤衰竭是低灌注导致的皮肤和底层组织死亡事件,同时伴发其他器官系统严重功能障碍或衰竭。”Levine还发表了关于皮肤衰竭的评注,10,11包括提出的皮肤衰竭定义,如“组织耐受性严重受损的一种状态,导致生理损伤区域(如缺氧、局部机械应力、营养输送障碍、毒性代谢副产物积聚区域)内的细胞无法存活。在该模式中,皮肤衰竭可能发生于皮肤及底层组织(包括肌肉)受到拉伸和外部压力的骨性隆起部位。”11按照这些标准,低灌注和伴发2个或多个其他器官受损的皮肤衰竭可以发生在急性病、慢性病或生命终末期时。

还需继续明确的是皮肤衰竭是否累及1个或多个器官。调查获得多个书面评论,均关于希望获得更多证据以明确标准是1个严重器官衰竭(如心脏骤停),还是必须2个内脏器官衰竭。

重要的一点是区分皮肤衰竭与可能因低灌注以外的机制而造成皮肤受损的其他皮肤病过程(如过度灌注引起皮肤受损,>90%的皮肤发红的红皮病)。皮肤受损范围在描述皮肤衰竭相关的缺血性损伤时是一个非常重要的组成部分。还应记录皮肤改变的具体描述。调查中收到的某些书面评论建议,采用皮肤损伤的严重程度(红斑、糜烂、溃疡、坏死、挫伤)和损伤范围(占身体表面积的百分比)作为确定治疗的记录依据可能比皮肤损伤度更好。

受访者同意,皮肤衰竭可能发生在生命终末期,也可能发生在急性病、慢性病中。Delmore及其同事发表了2篇关于急性病相关皮肤衰竭的基于数据的论文。12,13 2015年,他们将急性皮肤衰竭定义为“重症下,皮肤低灌注导致组织死亡”12,随后将该定义修改为“与重症同时发生的造成组织死亡的低灌注状态。”13

有证据表明,缺血时,PI的阈值压力更低,即使在可接受的护理标准下也可能发生。6还有15个开放式评论称PI更容易在皮肤衰竭下发生,是皮肤衰竭概念的一部分。

声明9:SCALE

“SCALE声明中指出的改变可在无皮肤衰竭的情况下发生”,该项声明的同意率为81.42%,因此达成共识。生命终末期皮肤改变14,15可能发生于患者濒死但未伴发2个内脏器官衰竭时,尽管许多SCALE标准可能出现在皮肤衰竭的定义中。另外,SCALE包括皮肤颜色、饱满度或完整性的改变(涉及医疗器械、失禁、化学刺激、长期接触体液、皮肤撕裂伤、剪切、摩擦力和感染等因素)。营养不良可能导致体重减轻、消瘦、皮肤脱水改变等。组织灌注减少可能导致皮肤局部温度下降,脉管系统斑纹和皮肤坏死或坏疽。压力性损伤也是SCALE的一部分。以上大多数改变可能是不可避免的。

声明8和10:不可避免皮肤改变

声明8,“肯氏终末期溃疡(KTU)、特-布氏终末期组织损伤(TB-TTI)、生命终末期皮肤改变(SCALE)和生命终末期皮肤衰竭是不可避免的,并非护理不良造成的”,获得86.59%的同意,因此达成共识。同样,声明10“您对美国医疗保险和医疗补助服务中心的可避免/不可避免压力性损伤定义的同意程度如何?”获得90.91%的同意,达成共识。

提供用来区分可避免与不可避免PI的最新CMS定义(2017年11月28日生效)如下:6

“可避免”指,居民患上压疮/压力性损伤,而医疗照护机构未能采取以下一项或多项措施:评估居民的临床病情和危险因素;确定并实施符合居民需求、居民目标和专业实践标准的干预措施;监测和评估干预措施的影响;或酌情修改干预措施。

“不可避免”指,即使医疗照护机构评估了居民的临床病情和危险因素;确定并实施了符合居民需求、居民目标和专业实践标准的干预措施;监测和评估了干预措施的影响;并酌情修改了干预方法,但居民依然患上压疮/压力性损伤。

CMS还提供了关于生命终末期PI的某些澄清说明。即使居民有预先指示,医疗照护机构依然需要向居民提供上述指示不禁止的支持性相关护理。6另外,还提供了关于PI是否可避免的声明:

对于调查员而言,重要的一点是理解当医疗照护机构已经根据居民的愿望实施生命终末期护理的个性化护理方法时,则可将PU/PI的进展、持续或恶化认为是不可避免的。如果医疗照护机构已采取适当措施稳定居民的病情(或指出无法或不应稳定病情的原因),并提供相关护理来预防和治疗现有PU/PI(包括相关的、常规的、不太积极的护理方法,如清洁、翻身、调整体位),则可将PU/PI认为是不可避免的,并符合法规要求。

某些书面回复表达了对如何定义“护理不良”的担忧。可能CMS在“不可避免”定义中描述的过程的要点可用于定义调查受访者所谓的“护理不良”。

开放式问题

在调查结尾,调查作者邀请受访者写下他们的评论;其中一些评论按主题分类列于表3。许多受访者称他们希望得到更加权威的关于皮肤衰竭/生命终末期皮肤改变的声明(如来自工作小组或共识小组)。他们还要求定义应与证据更紧密相联。显然,需要采用改良的生命终末期皮肤衰竭概念框架进行研究,以获得更多的科学证据。需要验证有关诊断标准的具体意见,而更明确的定义强化需要进一步研究。临床医师还希望多了解如何描述这些伤口,这些伤口如何影响给付,以及这些问题如何与患者和家属关联。对于更加专注的临床医师教育的需求是未来的一个机会。

结论

本研究是采取结构化方式探索全球的皮肤与伤口护理界对终末期溃疡/损伤、皮肤衰竭和SCALE意见的第一步。很明显,受访者希望获得明确的术语,并达成全球共识。重要的一点是,对于皮肤衰竭是否包括PI没有达成共识。受访者反复表示该领域需要更多研究,包括明确的诊断标准。下一步可能包括由知识转化工作小组或全球共识大会探讨术语,并提出科学验证研究。可通过资助国家或国际专业组织开发数据库来促进该研究的完成。

实践要点

- 认为KTU和TB-TTI是在生命终末期患者中观察到的终末期溃疡。

- 调查结果显示,关于皮肤衰竭的概念是否包括压力性损伤目前尚未达成共识。

- 必须进一步确定和验证皮肤衰竭(急性、慢性和/或生命终末期)标准。

- 尽管CMS和其他监管机构制定了不可避免与可避免PI的定义,但确定PI是否可避免的全球标准尚需验证和达成一致。

利益冲突

作者声明无利益冲突。

资助

作者未因本研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

R. Gary Sibbald

MD, DSc (Hons), MEd, FRCPC (Med Derm), ABIM, FAAD, MAPWCA,

Professor, Medicine and Public Health, Director, International Interprofessional Wound Care Course and Masters of Science in Community Health (Prevention and Wound Care), Dalla Lana Faculty of Public Health, University of Toronto; Lead Project ECHO Ontario Wound & Skin Care, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Investigator, Institute for Better Health, Trillium Health Partners; Co-Editor-in-Chief, Advances in Skin and Wound Care, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Elizabeth A. Ayello*

PhD, MS, BSN, RN, CWON, ETN, MAPWCA, FAAN,

Faculty, Excelsior College School of Nursing, Albany, New York; President, Ayello Harris & Associates, Inc, Copake, New York; President, World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®; Co-Editor-in-Chief, Advances in Skin & Wound Care, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

* Corresponding author

References

- Ayello EA, Levine JM, Langemo D, Kennedy-Evans KL, Brennan MR, Sibbald RG. Reexamining the literature on terminal ulcers, SCALE, skin failure, and unavoidable pressure injuries. Adv Skin Wound Care 2019;32(3):109–21.

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312(7023):71–2.

- Kennedy KL. The prevalence of pressure ulcers in an intermediate care facility. Decubitus 1989;2(2):44–5.

- Bonanno FG. Physiopathology of shock. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2011;4(2):222–32.

- Knight SL, Taylor RP, Polliack AA, Bader DL. Establishing predictive indicators for the status of loaded soft tissues. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001;90(6):2231–7.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. State Operations Manual: Guidance to Surveyors F686. 2017. www.amtwoundcare.com/uploads/2/0/3/7/20373073/som-guidance-to-surveyors-f686-only.pdf. Last accessed January 3, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Long-term Care Facility Resident Assessment Instrument 3.0 User’s Manual. Version 1.17.1. October 2019. https://downloads.cms.gov/files/mds-3.0-rai-manual-v1.17.1_october_2019.pdf. Last accessed January 3, 2019.

- Trombley K, Brennan MR, Thomas L, Kline M. Prelude to death or practice failure? Trombley-Brennan terminal tissue injuries. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29(7):541–5.

- Langemo D, Brown G. Skin fails too: acute, chronic, and end-stage skin failure. Adv Skin Wound Care 2006;19(4):206–11.

- Levine JM. Skin failure: an emerging concept. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17(7):666–9.

- Levine J. Unavoidable pressure injuries, terminal ulceration and skin failure: in search of a unifying classification system. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017;30(5):200–2.

- Delmore B, Cox J, Rolnitzky L, Chu A, Stolfi A. Differentiating a pressure ulcer from acute skin failure in the adult critical care patient. Adv Skin Wound Care 2015;28(11):514–24.

- Delmore B, Cox J, Smith D, Chu AS, Rolnitzky L. Acute skin failure in the critical care patient [published online November 27, 2019]. Adv Skin Wound Care.

- Sibbald RG, Krasner DL, Lutz J. SCALE: Skin changes at life’s end: final consensus statement: October 1, 2009. Adv Skin Wound Care 2010;23(5):225–36.

- Sibbald RG, Krasner D. Skin Changes At Life’s End (SCALE): a preliminary consensus statement. WCET J 2008;28(4):15–22.